Utility of Tumor Suppressor E2F Target Gene Promoter Elements to Drive Gene Expression Specifically in Cancer Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Plasmid

2.3. Luciferase Assay

2.4. Quantitative Reverse Transcription (qRT)-PCR Analysis

- HSV-TK:

- Fw: 5′-AGCAAGA AGCCACGGAAGTC-3′;

- Rv: 5′-GGCGGTCGAAGATGAGGGTGA-3′.

- GAPDH:

- Fw: 5′-GGAGTCCACTGGCGTCTTCA-3′;

- Rv: 5′-GAGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTT-3′.

- iRFP720:

- Fw: 5′-GGAGGCGGCACAGCTACGAGAACG-3′;

- Rv: 5′-GCGGCGAGGGCGAGCAG CAGTC-3′.

2.5. Immunoblot Analysis

2.6. Recombinant Adenovirus

2.7. FACS Analysis

2.8. Xenograft Assay

2.9. Analysis of Liver Function

2.10. Histological Analysis

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

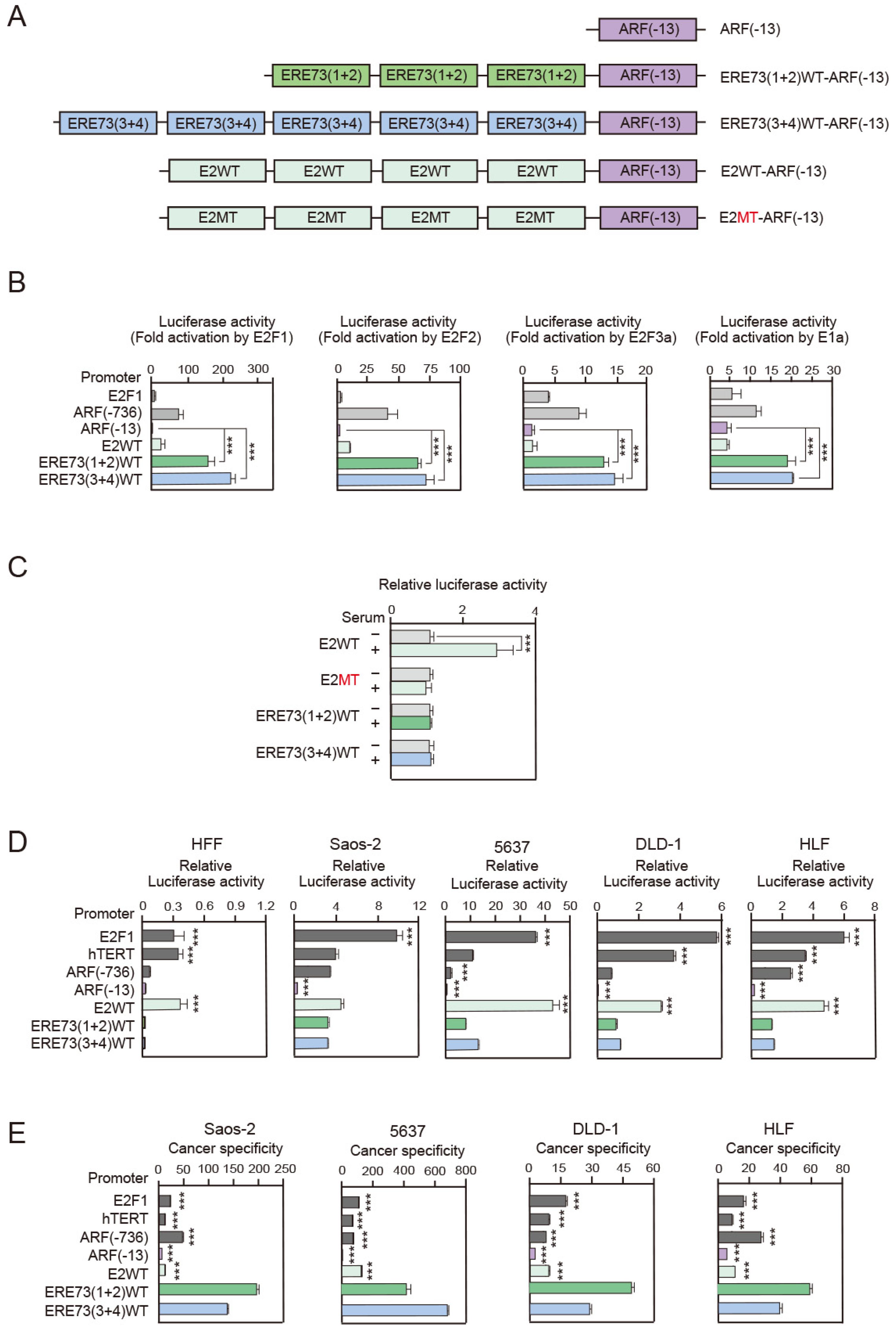

3.1. ERE73 (1 + 2)-ARF (−13) and ERE73 (3 + 4)-ARF (−13) Promoters Are More Cancer Cell-Specific than hTERT, E2F1, E2WT-ARF (−13), and ARF Promoters

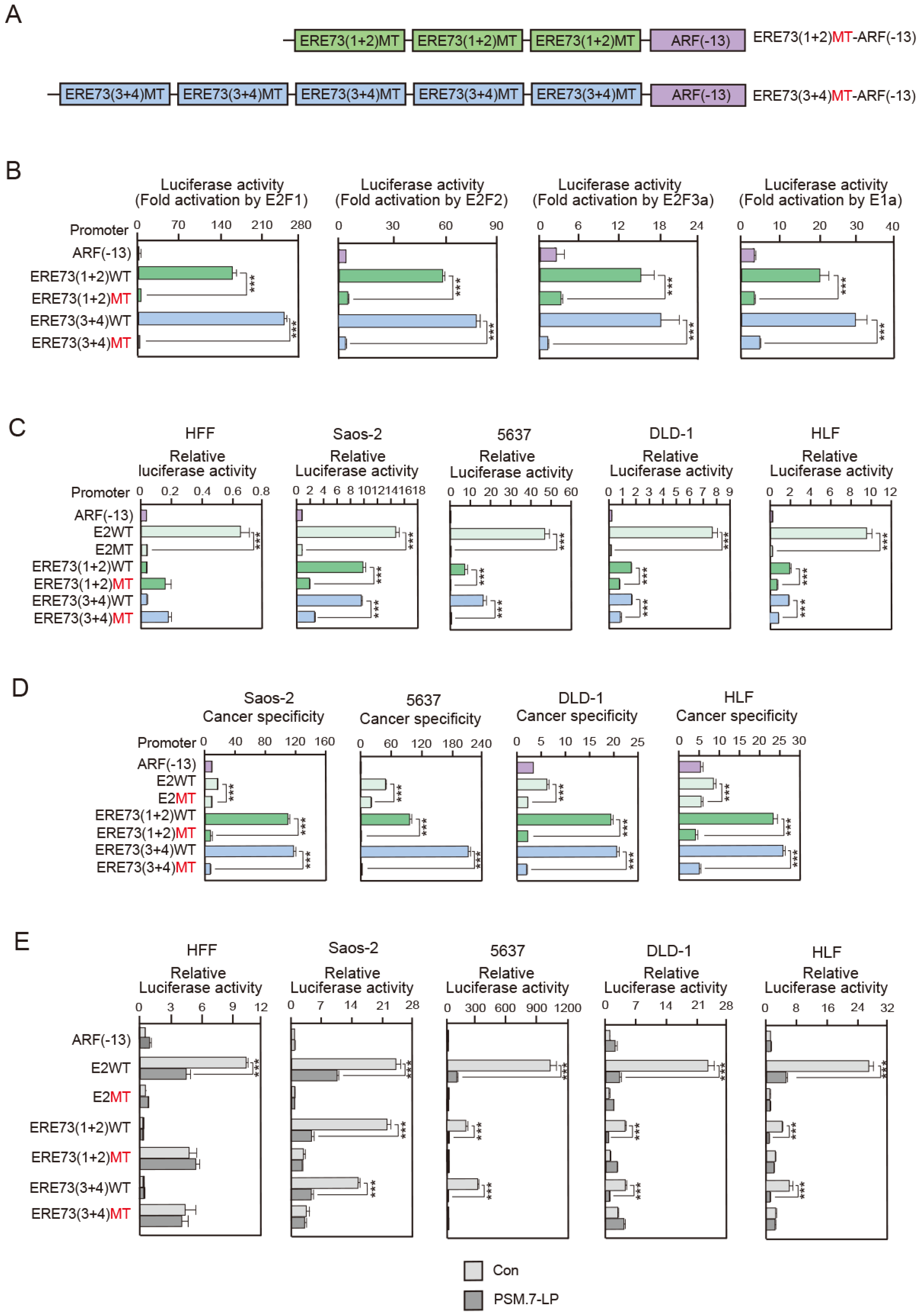

3.2. Deregulated E2F Activity Contributes to High Cancer Specificity of ERE73 (1 + 2)-ARF (−13) and ERE73 (3 + 4)-ARF (−13)

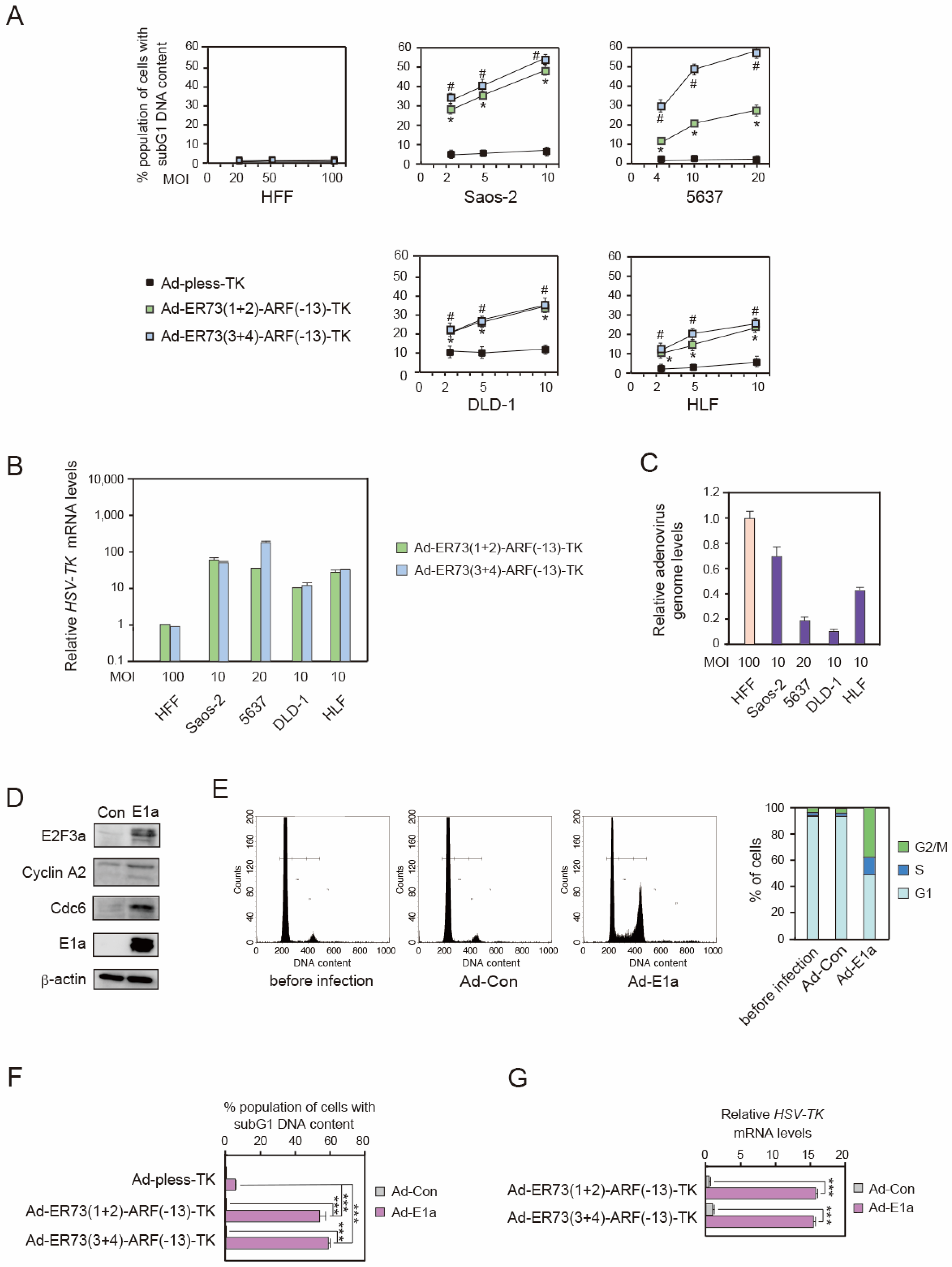

3.3. Ad-ERE73 (1 + 2)-ARF (−13)-TK and Ad-ERE73 (3 + 4)-ARF (−13)-TK Virus Vectors Induce Cell Death Specifically in Cancer Cells

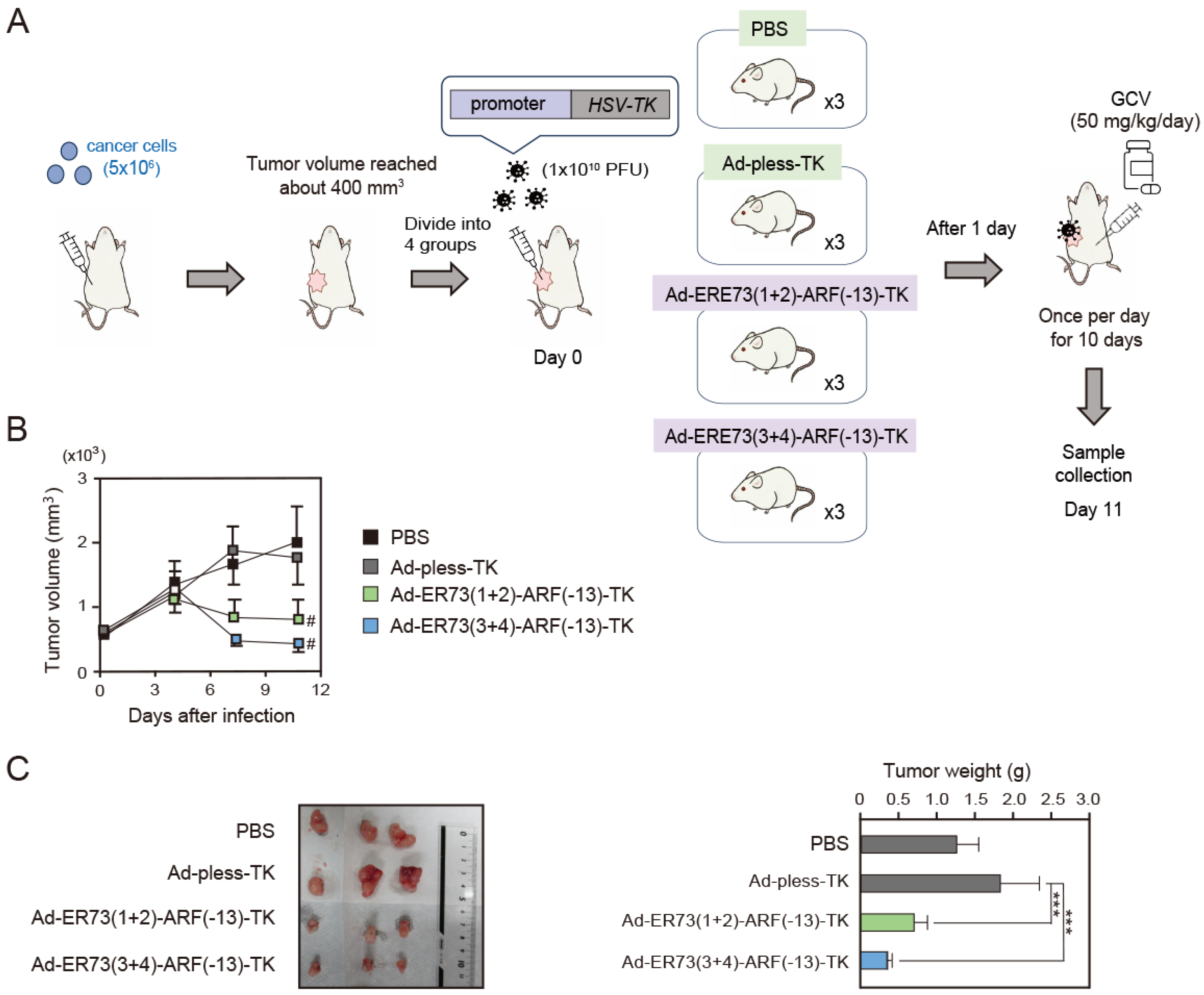

3.4. Ad-ERE73 (1 + 2)-ARF (−13)-TK and ERE73 (3 + 4)-ARF (−13)-TK Show Anti-Tumor Effects In Vivo

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ad | adenovirus |

| ALT | alanine transaminase |

| APC | adenomatous coli |

| ARF | alternative reading frame |

| AST | aspartate aminotransferase |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| CDC | cell division cycle |

| CDK | cyclin-dependent kinase |

| CMV | cytomegalovirus |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium |

| ERE | E2F-responsive element |

| EREA | E2F-responsive element of ARF promoter |

| ERE73 | E2F-responsive element of TAp73 promoter |

| FACS | fluorescence activated cell sorting |

| FCS | fetal calf serum |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| HDM2 | human double minute 2 |

| HE | Hematoxylin Eosin |

| HFF | human foreskin fibroblast |

| HRP | horse radish peroxidase |

| HSV | herpes simplex virus |

| hTERT | human telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| MOI | multiplicity of infection |

| MT | mutant type |

| PEI | Polyethylenimine |

| PFU | plaque-forming unit |

| pless | promoter less |

| RB | retinoblastoma |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| RL | Renilla luciferase |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| RT | reverse transcription |

| SD | standard deviation |

| TAp73 | transactivating p73 |

| TK | thymidine kinase |

| WT | wild type |

References

- Duarte, S.; Carle, G.; Faneca, H.; de Lima, M.C.; Pierrefite-Carle, V. Suicide gene therapy in cancer: Where do we stand now? Cancer Lett. 2012, 324, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.M. Suicide gene therapy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2000, 465, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Kagawa, S.; Takakura, M.; Kyo, S.; Inoue, M.; Roth, J.A.; Fang, B. Tumor-specific transgene expression from the human telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter enables targeting of the therapeutic effects of the Bax gene to cancers. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 5359–5364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Komata, T.; Kondo, Y.; Kanzawa, T.; Ito, H.; Hirohata, S.; Koga, S.; Sumiyoshi, H.; Takakura, M.; Inoue, M.; Barna, B.P.; et al. Caspase-8 gene therapy using the human telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter for malignant glioma cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2002, 13, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukuda, K.; Wiewrodt, R.; Molnar-Kimber, K.; Jovanovic, V.P.; Amin, K.M. An E2F-responsive replication-selective adenovirus targeted to the defective cell cycle in cancer cells: Potent antitumoral efficacy but no toxicity to normal cell. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 3438–3447. [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima, T.; Kagawa, S.; Kobayashi, N.; Shirakiya, Y.; Umeoka, T.; Teraishi, F.; Taki, M.; Kyo, S.; Tanaka, N.; Fujiwara, T. Telomerase-specific replication-selective virotherapy for human cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.J.; Peng, K.W.; Bell, J.C. Oncolytic virotherapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemany, R. Oncolytic Adenoviruses in Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines 2014, 2, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Guo, J.; He, P.; Zhou, D. Recent advances of oncolytic virus in cancer therapy. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020, 16, 2389–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Shen, Y.; Liang, T. Oncolytic virotherapy: Basic principles, recent advances and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, F.; Fusciello, M.; Cerullo, V. Personalizing Oncolytic Virotherapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2023, 34, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Sun, H.; Lemoine, N.R.; Xuan, Y.; Wang, P. Oncolytic vaccinia virus and cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1324744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volovat, S.R.; Scripcariu, D.V.; Vasilache, I.A.; Stolniceanu, C.R.; Volovat, C.; Augustin, I.G.; Volovat, C.C.; Ostafe, M.R.; Andreea-Voichita, S.G.; Bejusca-Vieriu, T.; et al. Oncolytic Virotherapy: A New Paradigm in Cancer Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M.M.; Cascallo, M.; Gomez-Manzano, C.; Jiang, H.; Bekele, B.N.; Perez-Gimenez, A.; Lang, F.F.; Piao, Y.; Alemany, R.; Fueyo, J. ICOVIR-5 shows E2F1 addiction and potent antiglioma effect in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 8255–8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, J.J.; Cascallo, M.; Guedan, S.; Gros, A.; Martinez-Quintanilla, J.; Hemminki, A.; Alemany, R. A modified E2F-1 promoter improves the efficacy to toxicity ratio of oncolytic adenoviruses. Gene Ther. 2009, 16, 1441–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wei, F.; Li, H.; Ji, X.; Li, S.; Chen, X. Combination of oncolytic adenovirus and endostatin inhibits human retinoblastoma in an in vivo mouse model. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 31, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Sun, P.; Liu, H.; Fan, Q.; Liang, K.; Liang, W.; Sun, H.; et al. Combination of E2F-1 promoter-regulated oncolytic adenovirus and cytokine-induced killer cells enhances the antitumor effects in an orthotopic rectal cancer model. Tumour. Biol. 2014, 35, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, S.; Jia, T.; Du, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Liang, K.; Liang, W.; Sun, H.; et al. Combined therapy with CTL cells and oncolytic adenovirus expressing IL-15-induced enhanced antitumor activity. Tumour. Biol. 2015, 36, 4535–4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemminki, O.; Parviainen, S.; Juhila, J.; Turkki, R.; Linder, N.; Lundin, J.; Kankainen, M.; Ristimaki, A.; Koski, A.; Liikanen, I.; et al. Immunological data from cancer patients treated with Ad5/3-E2F-Δ24-GMCSF suggests utility for tumor immunotherapy. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 4467–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducrest, A.L.; Szutorisz, H.; Lingner, J.; Nabholz, M. Regulation of the human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene. Oncogene 2002, 21, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumura-Arioka, Y.; Ohtani, K.; Hara, T.; Iwanaga, R.; Nakamura, M. Identification of two distinct elements mediating activation of telomerase (hTERT) gene expression in association with cell growth in human T cells. Int. Immunol. 2005, 17, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevins, J.R. The Rb/E2F pathway and cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaquinta, P.J.; Lees, J.A. Life and death decisions by the E2F transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2007, 19, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Heuvel, S.; Dyson, N.J. Conserved functions of the pRB and E2F families. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, L.N.; Leone, G. The broken cycle: E2F dysfunction in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Nakajima, R.; Shirasawa, M.; Fikriyanti, M.; Zhao, L.; Iwanaga, R.; Bradford, A.P.; Kurayoshi, K.; Araki, K.; Ohtani, K. Expanding Roles of the E2F-RB-p53 Pathway in Tumor Suppression. Biology 2023, 12, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, N.J. RB1: A prototype tumor suppressor and an enigma. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 1492–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Galvez, C.C.; Ordaz-Favila, J.C.; Villar-Calvo, V.M.; Cancino-Marentes, M.E.; Bosch-Canto, V. Retinoblastoma: Review and new insights. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 963780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherr, C.J. Cancer cell cycles. Science 1996, 274, 1672–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherr, C.J.; McCormick, F. The RB and p53 pathways in cancer. Cancer Cell 2002, 2, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.G.; Ohtani, K.; Nevins, J.R. Autoregulatory control of E2F1 expression in response to positive and negative regulators of cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 1994, 8, 1514–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubczak, J.L.; Ryan, P.; Gorziglia, M.; Clarke, L.; Hawkins, L.K.; Hay, C.; Huang, Y.; Kaloss, M.; Marinov, A.; Phipps, S.; et al. An oncolytic adenovirus selective for retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein pathway-defective tumors: Dependence on E1A, the E2F-1 promoter, and viral replication for selectivity and efficacy. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, N.; Ge, Y.; Ennist, D.L.; Zhu, M.; Mina, M.; Ganesh, S.; Reddy, P.S.; Yu, D.C. CG0070, a conditionally replicating granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor–armed oncolytic adenovirus for the treatment of bladder cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, S.J.; Miyashita-Lin, E.; Tseng, W.J.; Wang, A.; Li, J.; Yagami, M.; Vives, F.; Aimi, J.; Lin, A. Use of a bioamplification assay to detect nonselective recombinants and assess the genetic stability of oncolytic adenoviruses. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010, 21, 1707–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.M.; Lamm, D.L.; Meng, M.V.; Nemunaitis, J.J.; Stephenson, J.J.; Arseneau, J.C.; Aimi, J.; Lerner, S.; Yeung, A.W.; Kazarian, T.; et al. A first in human phase 1 study of CG0070, a GM-CSF expressing oncolytic adenovirus, for the treatment of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. J. Urol. 2012, 188, 2391–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packiam, V.T.; Lamm, D.L.; Barocas, D.A.; Trainer, A.; Fand, B.; Davis, R.L., 3rd; Clark, W.; Kroeger, M.; Dumbadze, I.; Chamie, K.; et al. An open label, single-arm, phase II multicenter study of the safety and efficacy of CG0070 oncolytic vector regimen in patients with BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Interim results. Urol. Oncol. 2018, 36, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandi, P.; Darilek, A.; Moscu, A.; Pradhan, A.; Li, R. Intravesical Infusion of Oncolytic Virus CG0070 in the Treatment of Bladder Cancer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2023, 2684, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komori, H.; Enomoto, M.; Nakamura, M.; Iwanaga, R.; Ohtani, K. Distinct E2F-mediated transcriptional program regulates p14ARF gene expression. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 3724–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozono, E.; Komori, H.; Iwanaga, R.; Tanaka, T.; Sakae, T.; Kitamura, H.; Yamaoka, S.; Ohtani, K. Tumor suppressor TAp73 gene specifically responds to deregulated E2F activity in human normal fibroblasts. Genes Cells 2012, 17, 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komori, H.; Goto, Y.; Kurayoshi, K.; Ozono, E.; Iwanaga, R.; Bradford, A.P.; Araki, K.; Ohtani, K. Differential requirement for dimerization partner DP between E2F-dependent activation of tumor suppressor and growth-related genes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.; Phillips, A.C.; Clark, P.A.; Stott, F.; Peters, G.; Ludwig, R.L.; Vousden, K.H. p14ARF links the tumour suppressors RB and p53. Nature 1998, 395, 124–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, A.M.; Bretz, A.C.; Mack, E.; Stiewe, T. Targeting p73 in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013, 332, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.; Marin, M.C.; Phillips, A.C.; Seelan, R.S.; Smith, D.I.; Liu, W.; Flores, E.R.; Tsai, K.Y.; Jacks, T.; Vousden, K.H.; et al. Role for the p53 homologue p73 in E2F-1-induced apoptosis. Nature 2000, 407, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissy, N.A.; Davis, P.K.; Irwin, M.; Kaelin, W.G.; Dowdy, S.F. A common E2F-1 and p73 pathway mediates cell death induced by TCR activation. Nature 2000, 407, 642–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiewe, T.; Putzer, B.M. Role of the p53-homologue p73 in E2F1-induced apoptosis. Nat. Genet. 2000, 26, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, R.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Shirasawa, M.; Uchida, A.; Murakawa, H.; Fikriyanti, M.; Iwanaga, R.; Bradford, A.P.; Araki, K.; et al. Deregulated E2F Activity as a Cancer-Cell Specific Therapeutic Tool. Genes 2023, 14, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurayoshi, K.; Ozono, E.; Iwanaga, R.; Bradford, A.P.; Komori, H.; Ohtani, K. Cancer cell specific cytotoxic gene expression mediated by ARF tumor suppressor promoter constructs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherr, C.J. The INK4a/ARF network in tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, S.W.; Sherr, C.J. Tumor suppression by Ink4a-Arf: Progress and puzzles. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2003, 13, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, K.; Iwanaga, R.; Arai, M.; Huang, Y.; Matsumura, Y.; Nakamura, M. Cell type-specific E2F activation and cell cycle progression induced by the oncogene product Tax of human T-cell leukemia virus type I. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 11154–11163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanaga, R.; Ohtani, K.; Hayashi, T.; Nakamura, M. Molecular mechanism of cell cycle progression induced by the oncogene product Tax of human T-cell leukemia virus type I. Oncogene 2001, 20, 2055–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, R.; Deguchi, R.; Komori, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Shirasawa, M.; Angelina, A.; Goto, Y.; Tohjo, F.; Nakahashi, K.; et al. The TFDP1 gene coding for DP1, the heterodimeric partner of the transcription factor E2F, is a target of deregulated E2F. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 663, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, J.K.; Bassing, C.H.; Kovesdi, I.; Datto, M.B.; Blazing, M.; George, S.; Wang, X.F.; Nevins, J.R. Expression of the E2F1 transcription factor overcomes type β transforming growth factor-mediated growth suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shew, J.Y.; Lin, B.T.; Chen, P.L.; Tseng, B.Y.; Yang-Feng, T.L.; Lee, W.H. C-terminal truncation of the retinoblastoma gene product leads to functional inactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, M.L.; Witte, N.; Im, K.M.; Turan, S.; Owens, C.; Misner, K.; Tsang, S.X.; Cai, Z.; Wu, S.; Dean, M.; et al. Molecular analysis of urothelial cancer cell lines for modeling tumor biology and drug response. Oncogene 2017, 36, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Fan, J.; Hochhauser, D.; Banerjee, D.; Zielinski, Z.; Almasan, A.; Yin, Y.; Kelly, R.; Wahl, G.M.; Bertino, J.R. Lack of functional retinoblastoma protein mediates increased resistance to antimetabolites in human sarcoma cell lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 10436–10440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helin, K.; Wu, C.L.; Fattaey, A.R.; Lees, J.A.; Dynlacht, B.D.; Ngwu, C.; Harlow, E. Heterodimerization of the transcription factors E2F-1 and DP-1 leads to cooperative trans-activation. Genes Dev. 1993, 7, 1850–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehara, K.; Yamakoshi, K.; Ohtani, N.; Kubo, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Arase, S.; Jones, N.; Hara, E. Reduction of total E2F/DP activity induces senescence-like cell cycle arrest in cancer cells lacking functional pRB and p53. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 168, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, H.; Ozono, E.; Iwanaga, R.; Bradford, A.P.; Okuno, J.; Shimizu, E.; Kurayoshi, K.; Kugawa, K.; Toh, H.; Ohtani, K. Identification of novel target genes specifically activated by deregulated E2F in human normal fibroblasts. Genes Cells 2015, 20, 739–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zindy, F.; Williams, R.T.; Baudino, T.A.; Rehg, J.E.; Skapek, S.X.; Cleveland, J.L.; Roussel, M.F.; Sherr, C.J. Arf tumor suppressor promoter monitors latent oncogenic signals in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 15930–15935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurayoshi, K.; Tanaka, M.; Nakajima, R.; Zhou, Y.; Shirasawa, M.; Fikriyanti, M.; Fujisawa, J.-i.; Iwanaga, R.; Bradford, A.P.; Araki, K.; et al. Utility of Tumor Suppressor E2F Target Gene Promoter Elements to Drive Gene Expression Specifically in Cancer Cells. Cells 2025, 14, 1953. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241953

Kurayoshi K, Tanaka M, Nakajima R, Zhou Y, Shirasawa M, Fikriyanti M, Fujisawa J-i, Iwanaga R, Bradford AP, Araki K, et al. Utility of Tumor Suppressor E2F Target Gene Promoter Elements to Drive Gene Expression Specifically in Cancer Cells. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1953. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241953

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurayoshi, Kenta, Masakazu Tanaka, Rinka Nakajima, Yaxuan Zhou, Mashiro Shirasawa, Mariana Fikriyanti, Jun-ichi Fujisawa, Ritsuko Iwanaga, Andrew P. Bradford, Keigo Araki, and et al. 2025. "Utility of Tumor Suppressor E2F Target Gene Promoter Elements to Drive Gene Expression Specifically in Cancer Cells" Cells 14, no. 24: 1953. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241953

APA StyleKurayoshi, K., Tanaka, M., Nakajima, R., Zhou, Y., Shirasawa, M., Fikriyanti, M., Fujisawa, J.-i., Iwanaga, R., Bradford, A. P., Araki, K., & Ohtani, K. (2025). Utility of Tumor Suppressor E2F Target Gene Promoter Elements to Drive Gene Expression Specifically in Cancer Cells. Cells, 14(24), 1953. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241953