MERS-CoV RBD-mRNA Presents Better Immunogenicity and Protection than the Spike-mRNA

Highlights

- Compared with MERS-CoV S-mRNA, MERS-CoV RBD-mRNA induced better antibody responses with broadly neutralizing antibodies against multiple MERS-CoV strains.

- MERS-CoV RBD-mRNA provided strong and durable protective efficacy against MERS-CoV challenge in a murine model.

- The RBD of MERS-CoV has great potential to serve as a critical target for the development of effective MERS-CoV vaccines.

- This study provides useful guidance for rational design of MERS-CoV vaccines.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells

2.2. Design and Construct of mRNA Vaccines

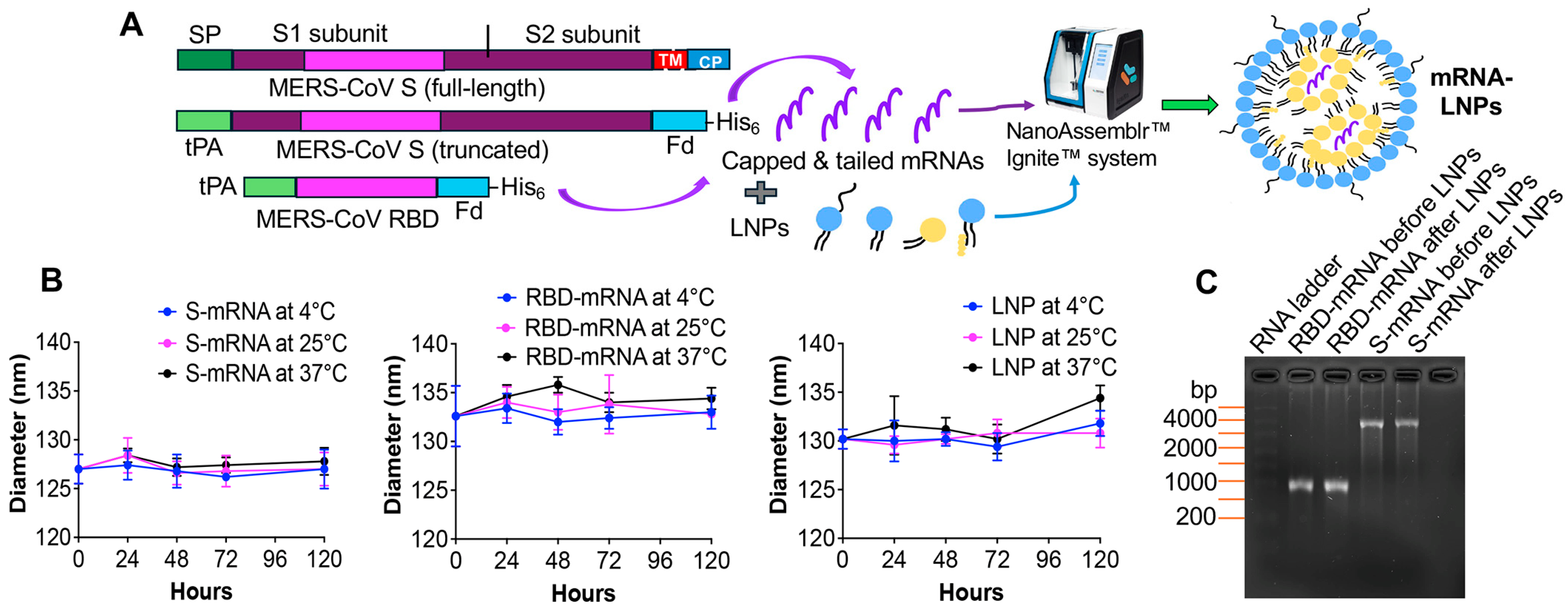

2.3. Synthesis, Formulation and Characterization of mRNA Vaccines

2.4. RNA Gel Electrophoresis

2.5. Construct, Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

2.6. Animal Vaccination and Sample Collection

2.7. ELISA

2.8. MERS Pseudovirus Preparation and Neutralization Assay

2.9. Virus Challenge and Protection Evaluation

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Design and Characterization of mRNA Vaccines

3.2. MERS-CoV RBD-mRNA Elicited Better Antibody Responses than MERS-CoV S-mRNA

3.3. MERS-CoV RBD-mRNA Induced Stronger and Broader Neutralizing Antibodies than MERS-CoV S-mRNA

3.4. RBD-mRNA Provided Durable Protective Efficacy Against MERS-CoV in Middle-Aged Mice and the Protection Was Positively Associated with Serum Neutralizing Antibodies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CoV | Coronavirus |

| DPP4 | Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| i.d. | Intradermal |

| i.n. | Intranasal |

| LNPs | Lipid nanoparticles |

| MERS-CoV | Middle East respiratory syndrome CoV |

| RBD | Receptor-binding domain |

| S | Spike |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome CoV-2 |

References

- Zaki, A.M.; van Boheemen, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Fouchier, R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Du, L. MERS coronavirus: An emerging zoonotic virus. Viruses 2019, 11, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogoti, B.M.; Riitho, V.; Wildemann, J.; Mutono, N.; Tesch, J.; Rodon, J.; Harichandran, K.; Emanuel, J.; Möncke-Buchner, E.; Kiambi, S.; et al. Biphasic MERS-CoV incidence in nomadic dromedaries with putative transmission to humans, Kenya, 2022–2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dighe, A.; Jombart, T.; Ferguson, N. Modelling transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in camel populations and the potential impact of animal vaccination. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, E.I.; El-Kafrawy, S.A.; Farraj, S.A.; Hassan, A.M.; Al-Saeed, M.S.; Hashem, A.M.; Madani, T.A. Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 2499–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carabelli, A.M.; Peacock, T.P.; Thorne, L.G.; Harvey, W.T.; Hughes, J.; Peacock, S.J.; Barclay, W.S.; de Silva, T.I.; Towers, G.J.; Robertson, D.L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: Immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oboho, I.K.; Tomczyk, S.M.; Al-Asmari, A.M.; Banjar, A.A.; Al-Mugti, H.; Aloraini, M.S.; Alkhaldi, K.Z.; Almohammadi, E.L.; Alraddadi, B.M.; Gerber, S.I.; et al. 2014 MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah—A link to health care facilities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkholy, A.A.; Grant, R.; Assiri, A.; Elhakim, M.; Malik, M.R.; Van Kerkhove, M.D. MERS-CoV infection among healthcare workers and risk factors for death: Retrospective analysis of all laboratory-confirmed cases reported to WHO from 2012 to 2 June 2018. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosten, C.; Meyer, B.; Müller, M.A.; Corman, V.M.; Al-Masri, M.; Hossain, R.; Madani, H.; Sieberg, A.; Bosch, B.J.; Lattwein, E.; et al. Transmission of MERS-coronavirus in household contacts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus—Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON569 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control. MERS-CoV Worldwide Overview. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/middle-east-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus-mers-cov-situation-update (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Singh, S.K. Middle East respiratory syndrome virus pathogenesis. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 37, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skariyachan, S.; Challapilli, S.B.; Packirisamy, S.; Kumargowda, S.T.; Sridhar, V.S. Recent aspects on the pathogenesis mechanism, animal models and novel therapeutic interventions for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Cao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Qi, J.; Wang, Q.; Lu, G.; Wu, Y.; Yan, J.; Shi, Y.; et al. Cryo-EM structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Qi, J.; Gao, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Bao, J.; et al. Molecular basis of binding between novel human coronavirus MERS-CoV and its receptor CD26. Nature 2013, 500, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Rajashankar, K.R.; Yang, Y.; Agnihothram, S.S.; Liu, C.; Lin, Y.L.; Baric, R.S.; Li, F. Crystal structure of the receptor-binding domain from newly emerged Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 10777–10783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Shi, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, D.; Tong, P.; Guo, D.; Fu, L.; Cui, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, J.K.; Whittaker, G.R. Host cell entry of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus after two-step, furin-mediated activation of the spike protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15214–15219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Matsuyama, S.; Li, X.; Takeda, M.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Inoue, J.I.; Matsuda, Z. Identification of Nafamostat as a potent inhibitor of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus S protein-mediated membrane fusion using the split-protein-based cell-cell fusion assay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6532–6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wong, G.; Lu, G.; Yan, J.; Gao, G.F. MERS-CoV spike protein: Targets for vaccines and therapeutics. Antiviral Res. 2016, 133, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, P.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Jia, W.; Wang, H.; Fan, A.; Wang, D.; Shi, X.; et al. Structural definition of a unique neutralization epitope on the receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV spike glycoprotein. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yang, Y.L.; Jeong, Y.; Jang, Y.S. Conjugation of human β-Defensin 2 to spike protein receptor-binding domain induces antigen-specific protective immunity against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 transgenic mice. Vaccines 2020, 8, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.A.; Goo, J.; Yang, E.; Jung, D.I.; Lee, S.; Rho, S.; Jeong, Y.; Park, Y.S.; Park, H.; Moon, Y.H.; et al. Cross-protection against MERS-CoV by prime-boost vaccination using viral spike DNA and protein. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01176-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shi, W.; Joyce, M.G.; Modjarrad, K.; Zhang, Y.; Leung, K.; Lees, C.R.; Zhou, T.; Yassine, H.M.; Kanekiyo, M.; et al. Evaluation of candidate vaccine approaches for MERS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallesen, J.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Wrapp, D.; Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Turner, H.L.; Cottrell, C.A.; Becker, M.M.; Wang, L.; Shi, W.; et al. Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E7348–E7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.E. The predictors of 3- and 30-day mortality in 660 MERS-CoV patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Sarkar, A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection: Analyses of risk factors and literature review of knowledge, attitude and practices. Zoonoses Public Health 2022, 69, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, W.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Wang, G.; Guan, X.; Zhu, J.; Perlman, S.; Du, L. MERS-CoV RBD-mRNA vaccine induces potent and broadly neutralizing antibodies with protection against MERS-CoV infection. Virus Res. 2023, 334, 199156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Verma, A.K.; Wang, G.; Roy, A.; Perlman, S.; Du, L. A unique mRNA vaccine elicits protective efficacy against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant and SARS-CoV. Vaccines 2024, 12, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golde, W.T.; Gollobin, P.; Rodriguez, L.L. A rapid, simple, and humane method for submandibular bleeding of mice using a lancet. Lab Anim. 2005, 34, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Verma, A.K.; Guan, X.; Bu, F.; Odle, A.E.; Li, F.; Liu, B.; Perlman, S.; Du, L. Pan-beta-coronavirus subunit vaccine prevents SARS-CoV-2 Omicron, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV challenge. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0037624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, K.; Wohlford-Lenane, C.; Agnihothram, S.S.; Fett, C.; Zhao, J.; Gale, M.J., Jr.; Baric, R.S.; Enjuanes, L.; Gallagher, T.; et al. Rapid generation of a mouse model for Middle East respiratory syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4970–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, Y.N. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: First approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, S.E.; Gargano, J.W.; Marin, M.; Wallace, M.; Curran, K.G.; Chamberland, M.; McClung, N.; Campos-Outcalt, D.; Morgan, R.L.; Mbaeyi, S.; et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Interim Recommendation for Use of Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 69, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.; Woodworth, K.R.; Gargano, J.W.; Scobie, H.M.; Blain, A.E.; Moulia, D.; Chamberland, M.; Reisman, N.; Hadler, S.C.; MacNeil, J.R.; et al. The Advisory Committee on immunization practices’ interim recommendation for use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in adolescents aged 12–15 years—United States, May 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodworth, K.R.; Moulia, D.; Collins, J.P.; Hadler, S.C.; Jones, J.M.; Reddy, S.C.; Chamberland, M.; Campos-Outcalt, D.; Morgan, R.L.; Brooks, O.; et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Interim Recommendation for use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in children aged 5-11 Years—United States, November 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1579–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Maruggi, G.; Shan, H.; Li, J. Advances in mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Porter, F.W.; Weissman, D. mRNA vaccines—A new era in vaccinology. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2018, 17, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalzik, F.; Schreiner, D.; Jensen, C.; Teschner, D.; Gehring, S.; Zepp, F. mRNA-based vaccines. Vaccines 2021, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokras, A.G.; Bobak, T.R.; Baghel, S.S.; Sebastiani, F.; Foged, C. Advances in the design and delivery of RNA vaccines for infectious diseases. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2024, 213, 115419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Sun, W.; Qi, H. Recent advancements in mRNA vaccines: From target selection to delivery systems. Vaccines 2024, 12, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Q.; Burgute, B.D.; Tzeng, S.C.; Jing, C.; Jungers, C.; Zhang, J.; Yan, L.L.; Vierstra, R.D.; Djuranovic, S.; Evans, B.S.; et al. N1-methylpseudouridine found within COVID-19 mRNA vaccines produces faithful protein products. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, P.S.; Mazur, M.; Orzeł, W.; Gewartowska, O.; Jeleń, S.; Antczak, W.; Kasztelan, K.; Brouze, A.; Matylla-Kulińska, K.; Gumińska, N.; et al. Re-adenylation by TENT5A enhances efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines. Nature 2025, 641, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Fang, Z.; Renauer, P.A.; McNamara, A.; Park, J.J.; Lin, Q.; Zhou, X.; Dong, M.B.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, H.; et al. Multiplexed LNP-mRNA vaccination against pathogenic coronavirus species. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Mao, Q.; Li, X.; Liang, Z.; He, Q. A cocktail of lipid nanoparticle-mRNA vaccines broaden immune responses against β-coronaviruses in a murine model. Viruses 2024, 16, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansour, I.; Jermy, B.R. Nucleic acid vaccine candidates encapsulated with mesoporous silica nanoparticles against MERS-CoV. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2024, 20, 2346390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weskamm, L.M.; Fathi, A.; Raadsen, M.P.; Mykytyn, A.Z.; Koch, T.; Spohn, M.; Friedrich, M.; MVA-MERS-S Study Group; Haagmans, B.L.; Becker, S.; et al. Persistence of MERS-CoV-spike-specific B cells and antibodies after late third immunization with the MVA-MERS-S vaccine. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.E.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; Jun, S.H.; Shin, H.J. A chimeric MERS-CoV virus-like particle vaccine protects mice against MERS-CoV challenge. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemzadeh, A.; Avan, A.; Ferns, G.A.; Khazaei, M. Vaccines based on virus-like nano-particles for use against Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus. Vaccine 2020, 38, 5742–5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.; Dahlke, C.; Krähling, V.; Kupke, A.; Okba, N.M.A.; Raadsen, M.P.; Heidepriem, J.; Müller, M.A.; Paris, G.; Lassen, S.; et al. Increased neutralization and IgG epitope identification after MVA-MERS-S booster vaccination against Middle East respiratory syndrome. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amri, S.S.; Abbas, A.T.; Siddiq, L.A.; Alghamdi, A.; Sanki, M.A.; Al-Muhanna, M.K.; Alhabbab, R.Y.; Azhar, E.I.; Li, X.; Hashem, A.M. Immunogenicity of candidate MERS-CoV DNA vaccines based on the spike protein. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Kim, H.J.; Chang, J. Superior immune responses induced by intranasal immunization with recombinant adenovirus-based vaccine expressing full-length spike protein of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.A.; Kim, J.O. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine development: Updating clinical studies using platform technologies. J. Microbiol. 2022, 60, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raadsen, M.P.; Dahlke, C.; Fathi, A.; Hardtke, S.; Klüver, M.; Krähling, V.; Gerresheim, G.K.; Mayer, L.; Mykytyn, A.Z.; Weskamm, L.M.; et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and optimal dosing of a modified vaccinia Ankara-based vaccine against MERS-CoV in healthy adults: A phase 1b, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folegatti, P.M.; Bittaye, M.; Flaxman, A.; Lopez, F.R.; Bellamy, D.; Kupke, A.; Mair, C.; Makinson, R.; Sheridan, J.; Rohde, C.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a candidate Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus viral-vectored vaccine: A dose-escalation, open-label, non-randomised, uncontrolled, phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeel, M.; Morsy, M.A.; Abd El-Lateef, H.M.; Marzok, M.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; Al Khodair, K.M.; Albokhadaim, I.; Venugopala, K.N. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1, MVA-MERS-S, and GLS-5300 DNA MERS-CoV vaccines. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 118, 109998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.; Khan, A.; Ansari, J.K.; Najmi, M.H.; Wei, D.Q.; Muhammad, K.; Waheed, Y. Potential immunogenic activity of computationally designed mRNA- and peptide-based prophylactic vaccines against MERS, SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2: A reverse vaccinology approach. Molecules 2022, 27, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.C.; Huang, C.Y.; Yao, B.Y.; Lin, J.C.; Agrawal, A.; Algaissi, A.; Peng, B.H.; Liu, Y.H.; Huang, P.H.; Juang, R.H.; et al. Viromimetic STING agonist-loaded hollow polymeric nanoparticles for safe and effective vaccination against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1807616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Yan, F.; Huang, P.; Chi, H.; Xu, S.; Li, G.; Liu, C.; Feng, N.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Characterization of the immune response of MERS-CoV vaccine candidates derived from two different vectors in mice. Viruses 2020, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okba, N.M.A.; Widjaja, I.; van Dieren, B.; Aebischer, A.; van Amerongen, G.; de Waal, L.; Stittelaar, K.J.; Schipper, D.; Martina, B.; van den Brand, J.M.A.; et al. Particulate multivalent presentation of the receptor binding domain induces protective immune responses against MERS-CoV. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.D.; Chi, W.Y.; Su, J.H.; Ferrall, L.; Hung, C.F.; Wu, T.C. Coronavirus vaccine development: From SARS and MERS to COVID-19. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassett, K.J.; Higgins, J.; Woods, A.; Levy, B.; Xia, Y.; Hsiao, C.J.; Acosta, E.; Almarsson, Ö.; Moore, M.J.; Brito, L.A. Impact of lipid nanoparticle size on mRNA vaccine immunogenicity. J. Control. Release. 2021, 335, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Reuschel, E.L.; Xu, Z.; Zaidi, F.I.; Kim, K.Y.; Scott, D.P.; Mendoza, J.; Ramos, S.; Stoltz, R.; Feldmann, F.; et al. Intradermal delivery of a synthetic DNA vaccine protects macaques from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. JCI. Insight 2021, 6, e146082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, R.B.; Dantas, W.M.; do Nascimento, J.C.F.; da Silva, M.V.; de Oliveira, R.N.; Pena, L.J. In vitro and in vivo models for studying SARS-CoV-2, the etiological agent responsible for COVID-19 pandemic. Viruses 2021, 13, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsen, M.O.; Rothen, D.; Balke, I.; Martina, B.; Zeltina, V.; Inchakalody, V.; Gharailoo, Z.; Nasrallah, G.; Dermime, S.; Tars, K.; et al. Neutralization of MERS coronavirus through a scalable nanoparticle vaccine. npj Vaccines 2021, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller-Kräuter, H.; Mezzacapo, J.; Klüver, M.; Baumgart, S.; Becker, D.; Fathi, A.; Pfeiffer, S.; Krähling, V. Quantitative assay to analyze neutralization and inhibition of authentic Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2024, 213, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Rosen, O.; Wang, L.; Turner, H.L.; Stevens, L.J.; Corbett, K.S.; Bowman, C.A.; Pallesen, J.; Shi, W.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Structural definition of a neutralization-sensitive epitope on the MERS-CoV S1-NTD. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 3395–3405.e3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Lan, Q.; Feng, S.; Qi, F.; Bao, L.; Du, L.; Liu, S.; et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, A.D.; Zheng, J.; Kim, Y.; Perera, K.D.; Mackin, S.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Kashipathy, M.M.; Battaile, K.P.; Lovell, S.; Perlman, S.; et al. 3C-like protease inhibitors block coronavirus replication in vitro and improve survival in MERS-CoV-infected mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eabc5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, S.; Yi, D.; Li, Q.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Guo, F.; Lin, R.; et al. A cell-based assay to discover inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Antiviral. Res. 2021, 190, 105078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiok, K.L.; Jenik, K.; Fenton, M.; Falzarano, D.; Dhar, N.; Banerjee, A. MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 infection in diverse human lung organoid-derived cultures. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0109825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satta, S.; Rockwood, S.J.; Wang, K.; Wang, S.; Mozneb, M.; Arzt, M.; Hsiai, T.K.; Sharma, A. Microfluidic organ-chips and stem cell models in the fight against COVID-19. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1405–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.R.; Mba Medie, F.; Luu, R.J.; Gaibler, R.B.; Mulhern, T.J.; Miller, C.R.; Zhang, C.J.; Rubio, L.D.; Marr, E.E.; Vijayakumar, V.; et al. A high throughput, high-containment human primary epithelial airway organ-on-chip platform for SARS-CoV-2 therapeutic screening. Cells 2023, 12, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, W.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Du, L. Advances in mRNA and other vaccines against MERS-CoV. Transl. Res. 2021, 242, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, P.J.; Tai, W.; Du, L.; Lustigman, S. The potency of an anti-MERS coronavirus subunit vaccine depends on a unique combinatorial adjuvant formulation. Vaccines 2020, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.C.; Agnihothram, S.S.; Jiao, Y.; Stanhope, J.; Graham, R.L.; Peterson, E.C.; Avnir, Y.; Tallarico, A.S.; Sheehan, J.; Zhu, Q.; et al. Identification of human neutralizing antibodies against MERS-CoV and their role in virus adaptive evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E2018–E2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Q.; Verma, A.K.; Guan, X.; Qian, S.; Perlman, S.; Du, L. MERS-CoV RBD-mRNA Presents Better Immunogenicity and Protection than the Spike-mRNA. Cells 2025, 14, 1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231928

Liu Q, Verma AK, Guan X, Qian S, Perlman S, Du L. MERS-CoV RBD-mRNA Presents Better Immunogenicity and Protection than the Spike-mRNA. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231928

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Qian, Abhishek K. Verma, Xiaoqing Guan, Shengnan Qian, Stanley Perlman, and Lanying Du. 2025. "MERS-CoV RBD-mRNA Presents Better Immunogenicity and Protection than the Spike-mRNA" Cells 14, no. 23: 1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231928

APA StyleLiu, Q., Verma, A. K., Guan, X., Qian, S., Perlman, S., & Du, L. (2025). MERS-CoV RBD-mRNA Presents Better Immunogenicity and Protection than the Spike-mRNA. Cells, 14(23), 1928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231928