LRRC1 Promotes Angiogenesis Through Regulating AKT/GSK3β/β-Catenin/VEGFA Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Highlights

- LRRC1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) angiogenesis by activating the AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin/VEGFA signaling pathway.

- LRRC1 enhances PDK1 expression by acting as a scaffold to recruit USP7 to deubiquitinate PDK1, thereby leading to increased AKT1 phosphorylation.

- LRRC1 is identified as a novel potential target for anti-angiogenic therapy in HCC.

- The elucidated LRRC1-VEGFA axis provides a theoretical basis for developing combination treatment strategies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Reagents

2.2. Patients and Tissue Specimens

2.3. Cell Transfection

2.4. Preparation of Tumor Conditional Medium

2.5. Invasion Assay

2.6. Scratch Assay

2.7. Tube Formation Assay

2.8. Chick Chorioallantois Membrane Assay

2.9. Animal Experiment

2.10. Immunohistochemistry Staining

2.11. Total RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Assay

2.12. Protein Extraction and Western Blot Assay

2.13. Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) Assay

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

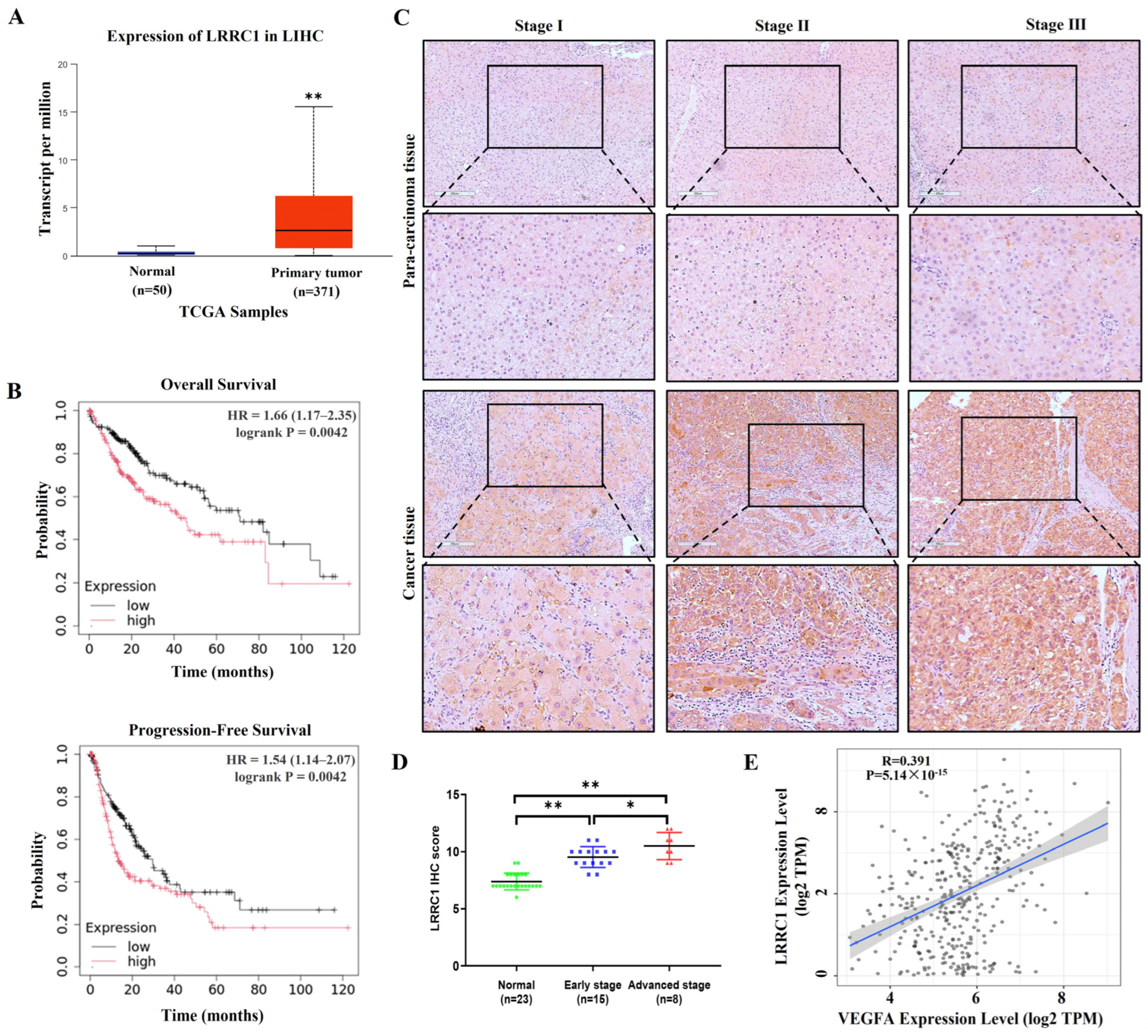

3.1. LRRC1 Expression Levels Are Elevated in HCC Tissues and Positively Correlated with the Expression Levels of VEGFA

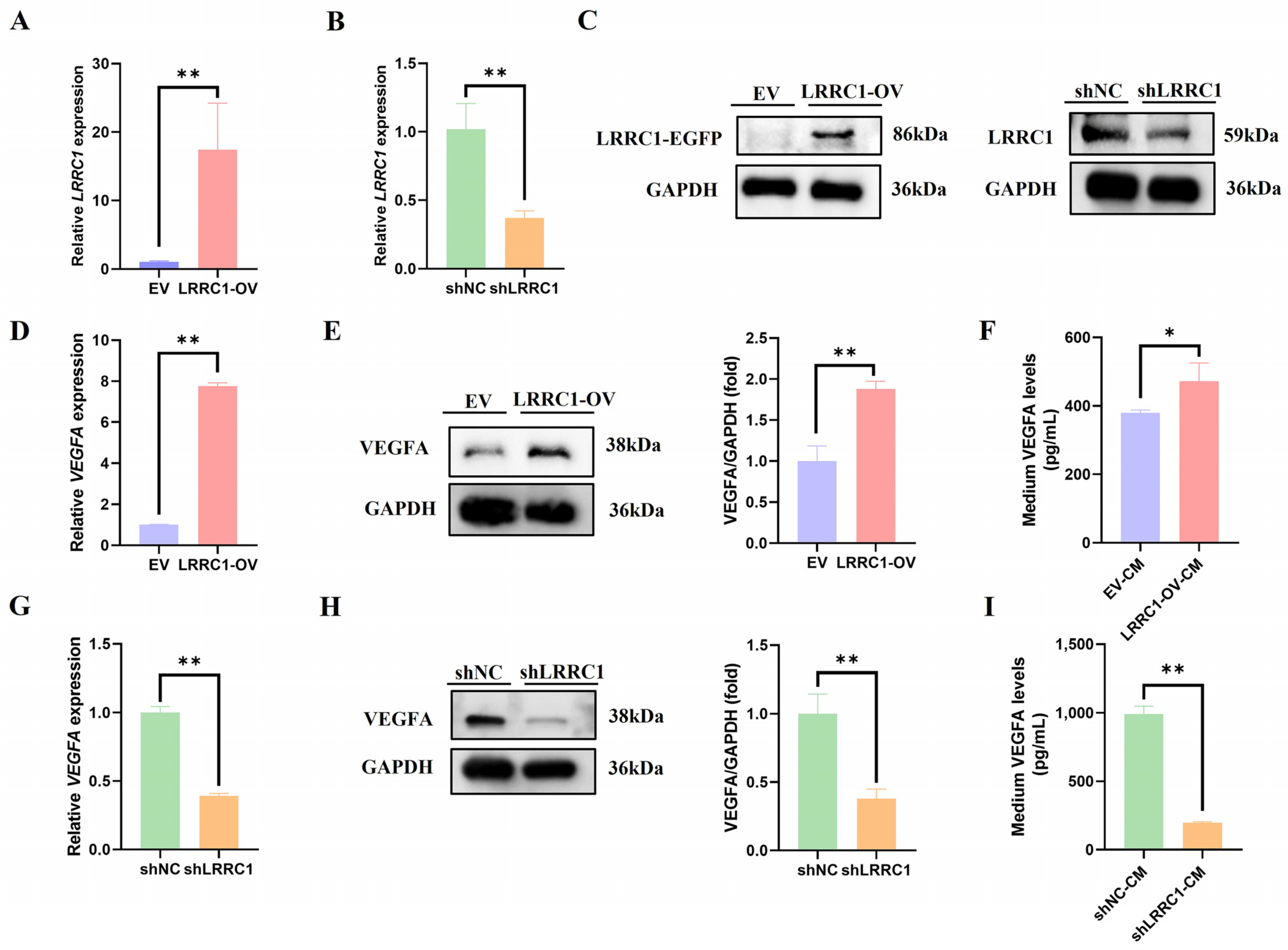

3.2. LRRC1 Positively Regulates the Expression of VEGFA

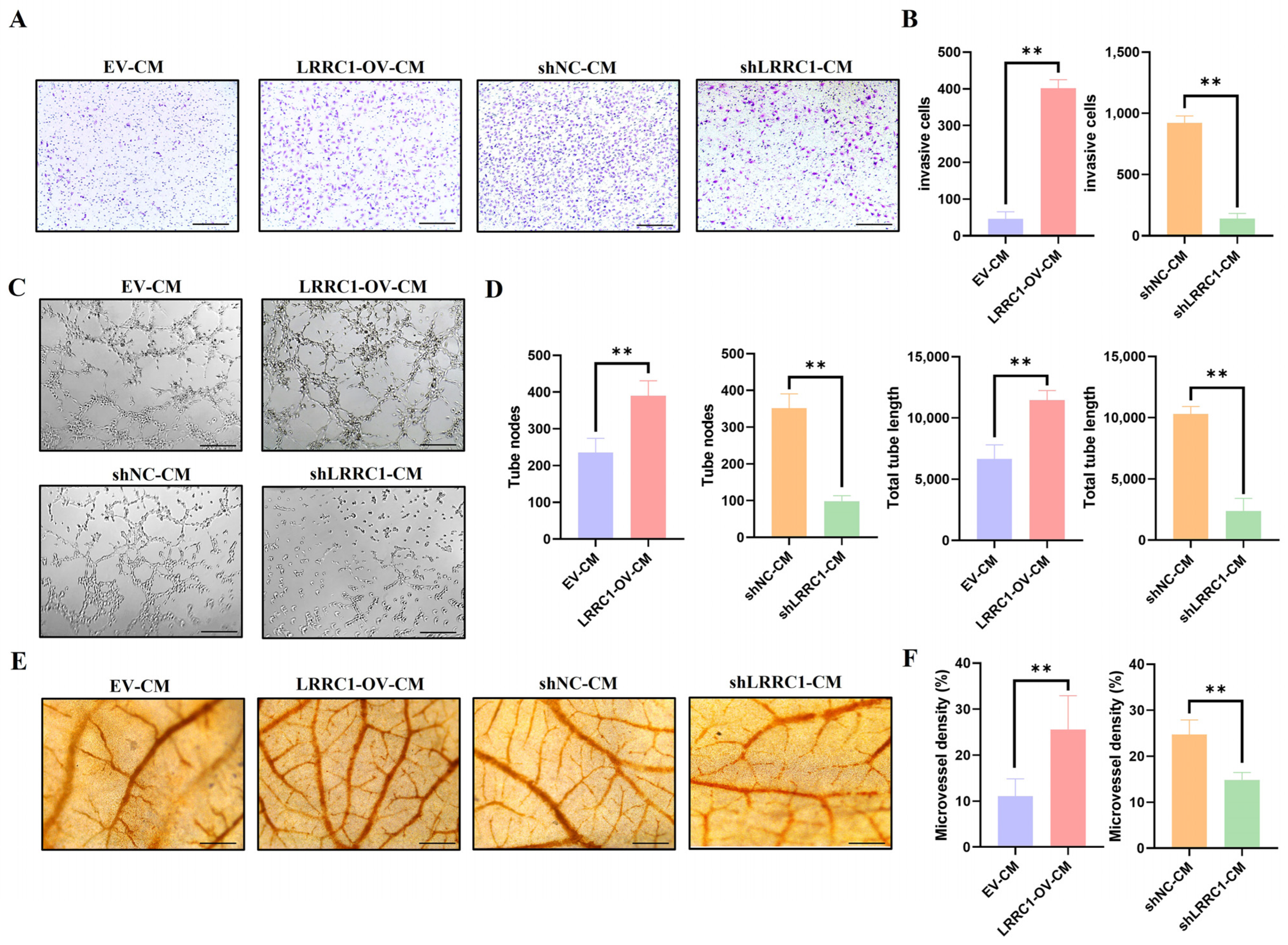

3.3. Tumor-Induced Angiogenesis Is Promoted by LRRC1 Through Regulating VEGFA Secretion

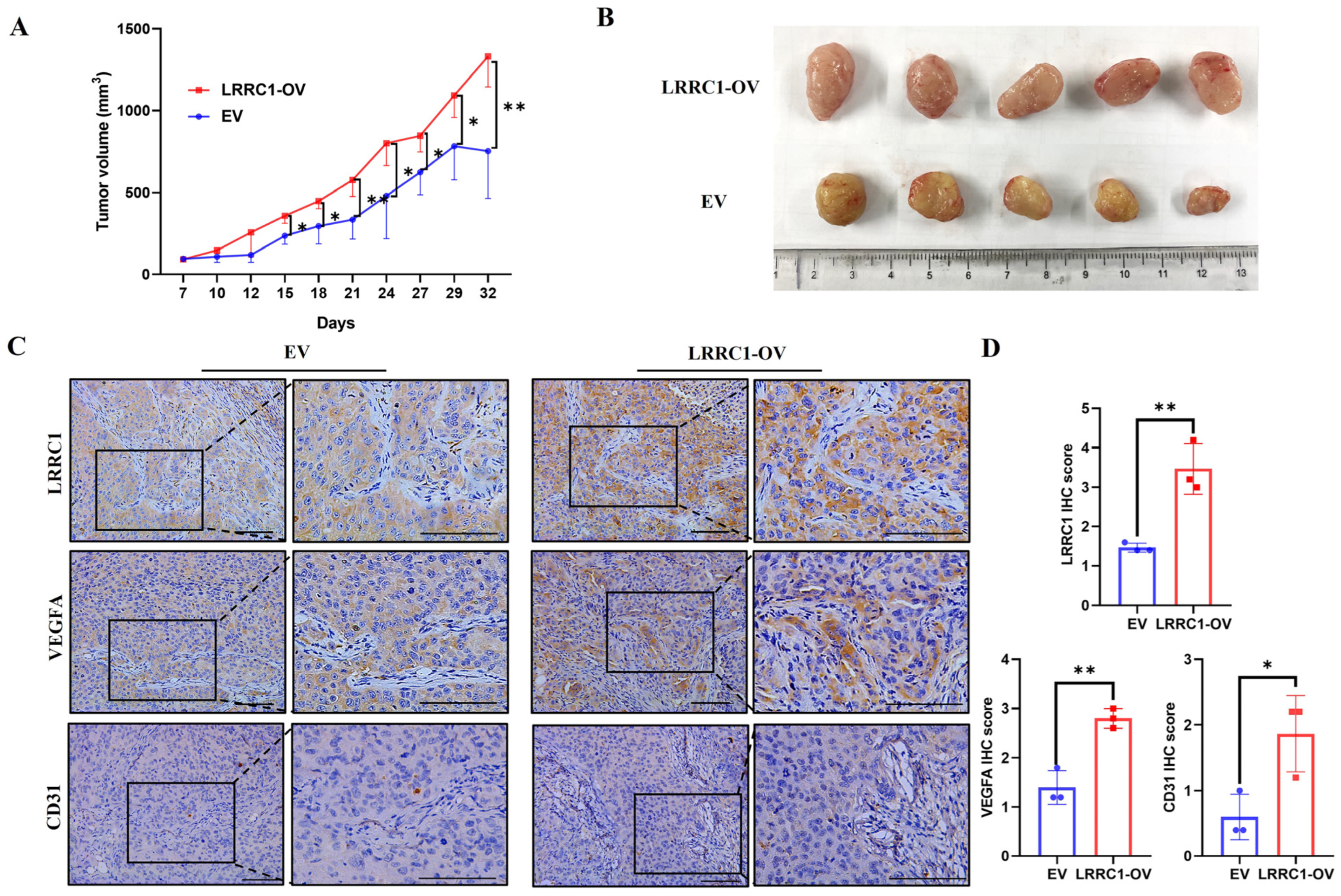

3.4. Overexpression of LRRC1 Promotes Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis in HCC-LM3 Xenograft Mice

3.5. LRRC1 Increases VEGFA Expression via AKT/GSK3β/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

3.6. LRRC1 Serves as a “Scaffold” to Recruit USP7 for Deubiquitylation of PDK1

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAM | Chick chorioallantois membrane |

| CM | Conditioned medium |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| LAP | Leucine-rich repeat and PDZ domain |

| LRRC1 | Leucine-rich repeat-containing 1 |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of cancer: New dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, A.C.; Griffioen, A.W. Pathological angiogenesis: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Angiogenesis 2023, 26, 313–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; He, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Qin, J.; Zhuang, L.; Wang, W.; et al. A pharmacogenomic landscape in human liver cancers. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Tey, S.K.; Mao, X.; Fung, H.L.; Xiao, Z.J.; Wong, D.; Mak, L.Y.; Yuen, M.F.; Ng, I.O.; Yun, J.P.; et al. Small extracellular vesicle-derived vwf induces a positive feedback loop between tumor and endothelial cells to promote angiogenesis and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2302677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicklin, D.J.; Ellis, L.M. Role of the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in tumor growth and angiogenesis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 1011–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, M.; Huang, L.; Huang, Y.; Lv, S.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Z.; Ke, Y.; Li, S.; et al. Gli1-mediated tumor cell-derived bFGF promotes tumor angiogenesis and pericyte coverage in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Liu, H.; Laugsand, J.B. Endothelial cells-directed angiogenesis in colorectal cancer: Interleukin as the mediator and pharmacological target. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 114, 109525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.; Horvat, N.; Fonseca, G.M.; Araujo-Filho, J.; Fernandes, M.C.; Charbel, C.; Chakraborty, J.; Coelho, F.F.; Nomura, C.H.; Herman, P. Current status and future perspectives of radiomics in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer. J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dam, P.; van der Stok, E.P.; Teuwen, L.; Van den Eynden, G.G.; Illemann, M.; Frentzas, S.; Majeed, A.W.; Eefsen, R.L.; Coebergh Van Den Braak, R.R.J.; Lazaris, A.; et al. International consensus guidelines for scoring the histopathological growth patterns of liver metastasis. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 1427–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, H.; Shibuya, M. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/VEGF receptor system and its role under physiological and pathological conditions. Clin. Sci. 2005, 109, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, R.S.; Chen, D.S.; Ferrara, N. VEGF in signaling and disease: Beyond discovery and development. Cell 2019, 176, 1248–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santorsola, M.; Capuozzo, M.; Nasti, G.; Sabbatino, F.; Di Mauro, A.; Di Mauro, G.; Vanni, G.; Maiolino, P.; Correra, M.; Granata, V.; et al. Exploring the spectrum of VEGF inhibitors’ toxicities from systemic to intravitreal usage in medical practice. Cancers 2024, 16, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Deng, B. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Molecular mechanism, targeted therapy, and biomarkers. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023, 42, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ileiwat, Z.E.; Tabish, T.A.; Zinovkin, D.A.; Yuzugulen, J.; Arghiani, N.; Pranjol, M. The mechanistic immunosuppressive role of the tumour vasculature and potential nanoparticle-mediated therapeutic strategies. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 976677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladejo, M.; Nguyen, H.M.; Silwal, A.; Reese, B.; Paulishak, W.; Markiewski, M.M.; Wood, L.M. Listeria-based immunotherapy directed against CD105 exerts anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor efficacy in renal cell carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1038807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Troyanovsky, R.B.; Indra, I.; Mitchell, B.J.; Troyanovsky, S.M. Scribble, Erbin, and Lano redundantly regulate epithelial polarity and apical adhesion complex. J. Cell. Biol. 2019, 218, 2277–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Ma, B.; Wu, P.; Xu, X.; Xiong, J. The downstream PPARgamma target LRRC1 participates in early stage adipocytic differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2023, 478, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.L.; Sebbagh, M.; Bertucci, F.; Finetti, P.; Wicinski, J.; Marchetto, S.; Castellano, R.; Josselin, E.; Charafe-Jauffret, E.; Ginestier, C.; et al. The SCRIB paralog LANO/LRRC1 regulates breast cancer stem cell fate through WNT/beta-Catenin signaling. Stem Cell Rep. 2018, 11, 1040–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tong, H.; Wang, J.; Hu, L.; Huang, Z. LRRC1 knockdown downregulates MACF1 to inhibit the malignant progression of acute myeloid leukemia by inactivating beta-catenin/c-Myc signaling. J. Mol. Histol. 2024, 55, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, B.; Dai, J.; Liu, R.; Han, Z.G. Aberrant upregulation of LRRC1 contributes to human hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 4543–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Ren, Y.; Ge, H.; Liang, C.; Xu, Y.; Li, G.; Wu, J. Comprehensive analysis of potential prognostic genes for the construction of a competing endogenous RNA regulatory network in hepatocellular carcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ao, L.; Guo, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gu, Z.; Xin, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, L. Recombinant canstatin inhibits the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma by repressing the HIF-1alpha/VEGF signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 179, 117423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, W.; Lin, X.; Chen, K.; Lin, X. m6A modification of VEGFA mRNA by RBM15/YTHDF2/IGF2BP3 contributes to angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Carcinog. 2024, 63, 2174–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Luo, Y.; Lu, J.; Fu, Q.; Wang, C.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. FBXO22 promotes HCC angiogenesis and metastasis via RPS5/AKT/HIF-1alpha/VEGF-A signaling axis. Cancer Gene Ther. 2025, 32, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Wang, J.; Chai, Z.; Xiong, W. Morphine promotes angiogenesis by activating PI3K/Akt/HIF-1alpha pathway and upregulating VEGF in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2021, 12, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Qi, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y. F13B regulates angiogenesis and tumor progression in hepatocellular carcinoma via the HIF-1alpha/VEGF pathway. Biomol. Biomed. 2024, 25, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Su, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Yang, F.; Li, G.; Shi, Q. Ginsenoside Rb1 promotes the growth of mink hair follicle via PI3K/AKT/GSK-3beta signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2019, 229, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, M. Multi-layered prevention and treatment of chronic inflammation, organ fibrosis and cancer associated with canonical WNT/beta-catenin signaling activation (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, N.; Zhang, X.; Dai, X.; Zhang, L.; Hu, C.; Wu, X.; Jiang, Q.; Wu, D.; et al. Copper promotes tumorigenesis by activating the PDK1-AKT oncogenic pathway in a copper transporter 1 dependent manner. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2004303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daulat, A.M.; Wagner, M.S.; Walton, A.; Baudelet, E.; Audebert, S.; Camoin, L.; Borg, J. The Tumor suppressor SCRIB is a negative modulator of the Wnt/beta-Catenin signaling pathway. Proteomics 2019, 19, e1800487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shi, X.; Ke, T.; Yan, Z.; Xiong, L.; Tang, F. USP7 promotes endothelial activation to aggravate sepsis-induced acute lung injury through PDK1/AKT/NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, P.; Sikorska, A.; Molenda, S.; Guzniczak, N.; Dams-Kozlowska, H.; Florczak, A. Physiological and tumor-associated angiogenesis: Key factors and therapy targeting VEGF/VEGFR pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 180, 117585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, N. Communication and health education research: Potential sources for education for prevention of drug use. NIDA Res. Monogr. 1990, 93, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuczynski, E.A.; Yin, M.; Bar-Zion, A.; Lee, C.R.; Butz, H.; Man, S.; Daley, F.; Vermeulen, P.B.; Yousef, G.M.; Foster, F.S.; et al. Co-option of liver vessels and not sprouting angiogenesis drives acquired sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. 2016, 108, djw030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Liu, T.; Yau, T.; Hsu, C. Novel systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Int. 2020, 14, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Mu, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Hu, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Mu, Y.; Yuan, F.; Liu, W.; et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomal microRNA-193a reduces cisplatin resistance of non-small cell lung cancer cells via targeting LRRC1. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potente, M.; Carmeliet, P. The link between angiogenesis and endothelial metabolism. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017, 79, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, U.R.; Chavakis, E.; Kruse, C.; Jungblut, B.; Kaluza, D.; Wandzioch, K.; Manavski, Y.; Heide, H.; Santoni, M.J.; Potente, M.; et al. The polarity protein Scrib is essential for directed endothelial cell migration. Circ. Res. 2013, 112, 924–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Li, B.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Song, L.; Cui, L.; Xie, D.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.; et al. Erbin plays a critical role in human umbilical vein endothelial cell migration and tubular structure formation via the Smad1/5 pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 4654–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llovet, J.M. Focal gains of VEGFA: Candidate predictors of sorafenib response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 560–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Su, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Wu, X.; Huang, S.; He, X.; Liang, L. LTR retrotransposon-derived LncRNA LINC01446 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression and angiogenesis by regulating the SRPK2/SRSF1/VEGF axis. Cancer Lett. 2024, 598, 217088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Wu, S.; Kong, J.; Sun, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhu, R.; Li, Z.; Sun, W.; Zheng, L. Angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma: Mechanisms and anti-angiogenic therapies. Cancer Biol. Med. 2023, 20, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elagawany, M.; Abdel, G.L.; Ibrahim, T.S.; Alharbi, A.S.; Abdel-Aziz, M.S.; El-Labbad, E.M.; Ryad, N. Development of certain benzylidene coumarin derivatives as anti-prostate cancer agents targeting EGFR and PI3Kbeta kinases. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2024, 39, 2311157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, D.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Fan, L.; Yang, L.; Ren, Q.; Duangmano, S.; Du, F.; et al. Circular RNA ACVR2A promotes the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma through mir-511-5p targeting PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Jiang, X.; Lian, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, F.; Xie, J.; Deng, J.; Hou, X.; Du, Z.; Hao, E. Evaluation of the effect of GSK-3beta on liver cancer based on the PI3K/AKT pathway. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1431423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Cheng, H.; Wang, Y.; He, S.; Zuo, Q.; Wang, N.; Li, Q.; Wang, M. Cinobufacini enhances the therapeutic response of 5-Fluorouracil against gastric cancer by targeting cancer stem cells via AKT/GSK-3beta/beta-catenin signaling axis. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 47, 102054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Shang, N.; Zhang, D.; Sun, J.; et al. Isoandrographolide from Andrographis paniculata ameliorates tubulointerstitial fibrosis in ureteral obstruction-induced mice, associated with negatively regulating AKT/GSK-3beta/beta-cat signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 112, 109201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, H.; Zhang, F.; Hu, X.; Bi, F.; Li, K.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Teng, X.; Li, J.; et al. m6A methylated EphA2 and VEGFA through IGF2BP2/3 regulation promotes vasculogenic mimicry in colorectal cancer via PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdawi, L.M.; Ghatak, S.; Chakraborty, P.; Sjolander, A.; Andersson, T. LGR5 expression predicting poor prognosis is negatively correlated with wnt5a in colon cancer. Cells 2023, 12, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Feng, J.; Sun, W.; Wu, C.; Li, J.; Jing, T.; Liang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, H. CIRP promotes the progression of non-small cell lung cancer through activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling via CTNNB1. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, A.; Maiello, M.R.; D’Alessio, A.; Pergameno, M.; Normanno, N. The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and the PI3K/AKT signalling pathways: Role in cancer pathogenesis and implications for therapeutic approaches. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2012, 16 (Suppl. S2), S17–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Chi, Z.; Chen, B. Ligand-activated peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta facilitates cell proliferation in human cholesteatoma keratinocytes. PPAR Res. 2020, 2020, 8864813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, S.K.; Wong, S.W.K.; Chan, J.Y.T.; Mao, X.; Ng, T.H.; Yeung, C.L.S.; Leung, Z.; Fung, H.L.; Tang, A.H.N.; Wong, D.K.H.; et al. Patient pIgR-enriched extracellular vesicles drive cancer stemness, tumorigenesis and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Lin, S.; Bian, S.; Zheng, W.; Qu, L.; Fan, Y.; Lu, C.; Xiao, M.; Zhou, P. USP7 mediates pathological hepatic de novo lipogenesis through promoting stabilization and transcription of ZNF638. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Qi, Z.; Deng, M.; Huang, H.; Xu, Z.; Guo, G.; Jing, J.; Huang, X.; Xu, M.; Kloeber, J.A.; et al. The deubiquitinase USP7 regulates oxidative stress through stabilization of HO-1. Oncogene 2022, 41, 4018–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Guan, X.; Song, Z.; Liu, H.; Guan, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, L.; et al. The upregulation of leucine-rich repeat containing 1 expression activates hepatic stellate cells and promotes liver fibrosis by stabilizing phosphorylated Smad2/3. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoni, M.; Kashyap, R.; Camoin, L.; Borg, J. The Scribble family in cancer: Twentieth anniversary. Oncogene 2020, 39, 7019–7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Xie, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, L.; Shang, N.; Chen, M.; Feng, H.; Guan, X.; et al. LRRC1 Promotes Angiogenesis Through Regulating AKT/GSK3β/β-Catenin/VEGFA Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cells 2025, 14, 1919. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231919

Liu H, Liu Z, Xie P, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Cao L, Shang N, Chen M, Feng H, Guan X, et al. LRRC1 Promotes Angiogenesis Through Regulating AKT/GSK3β/β-Catenin/VEGFA Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1919. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231919

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Huanfei, Zhentao Liu, Peitong Xie, Zihan Liu, Yaqing Zhang, Lanxiao Cao, Ning Shang, Mei Chen, Huixing Feng, Xiaowen Guan, and et al. 2025. "LRRC1 Promotes Angiogenesis Through Regulating AKT/GSK3β/β-Catenin/VEGFA Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma" Cells 14, no. 23: 1919. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231919

APA StyleLiu, H., Liu, Z., Xie, P., Liu, Z., Zhang, Y., Cao, L., Shang, N., Chen, M., Feng, H., Guan, X., & Dai, G. (2025). LRRC1 Promotes Angiogenesis Through Regulating AKT/GSK3β/β-Catenin/VEGFA Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cells, 14(23), 1919. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231919