1. Introduction

Neoantigens, which arise from tumor-specific somatic mutations and are absent in normal tissues, have emerged as ideal targets for personalized cancer immunotherapy [

1]. Because they are recognized exclusively as “non-self” antigens, neoantigens can elicit highly tumor-specific T-cell responses without inducing autoimmunity. Accordingly, neoantigen-based vaccines and T cell receptor-engineered T cell (TCR-T) therapies have shown encouraging results in early clinical trials [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. These strategies provide a promising avenue for the development of safe and effective cancer immunotherapies tailored to individual patients. Indeed, the clinical success of these approaches, particularly in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors, underscores that expanding the tumor-specific T cells represents a key strategy to synergize with and augment the clinical benefit of existing immunotherapies [

8].

However, the realization of neoantigen-targeted immunotherapies still faces major challenges in both antigen and TCR discovery. On the antigen discovery side, while in silico prediction algorithms have improved, they still generate a substantial number of false-positive candidates that fail to elicit T-cell activation [

9,

10]. On the TCR discovery side, the challenge is that the tumor is infiltrated by a vast population of bystander T cells, among which the rare, truly specific TCRs must be identified [

11]. Thus, identifying which neoantigens are genuinely recognized by T cells in vivo remains elusive. To overcome this limitation, functional assays capable of simultaneously identifying both neoantigens and their cognate T cells (or their TCRs) are required.

Recent advances in single-cell sequencing have made it possible to determine the functional state of each T cell—such as activation, exhaustion, or differentiation—based on its transcriptomic profile, thereby enabling the prediction of neoantigen-specific T cells through their characteristic functional phenotypes [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Consequently, researchers are now confronted with the formidable task of validating which of the many transcriptome-prioritized TCRs can truly recognize a genuine neoantigen within an equally extensive and error-prone pool of in silico predictions [

16,

17].

In current practice, identification of bona fide neoantigens still relies on labor-intensive experimental validation. For each patient, somatic mutation lists and HLA typing data are used to predict potential MHC-binding peptides, which are then chemically synthesized. The synthesized peptides are pulsed onto antigen-presenting cells (APCs) expressing the patient’s HLA molecules and co-cultured with patient-derived peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) to assess antigen-specific T-cell responses. However, this validation process remains technically challenging and low throughput due to several factors: (1) the need to synthesize and test a large number of candidate peptides, which is both laborious and costly; (2) the requirement for HLA-matched APCs; (3) the limited availability of PBMCs and TILs from clinical specimens; and (4) potential biases introduced during in vitro expansion of TILs, which may not accurately reflect their ex vivo reactivity. These limitations hinder the efficient translation of neoantigen discoveries into clinical applications.

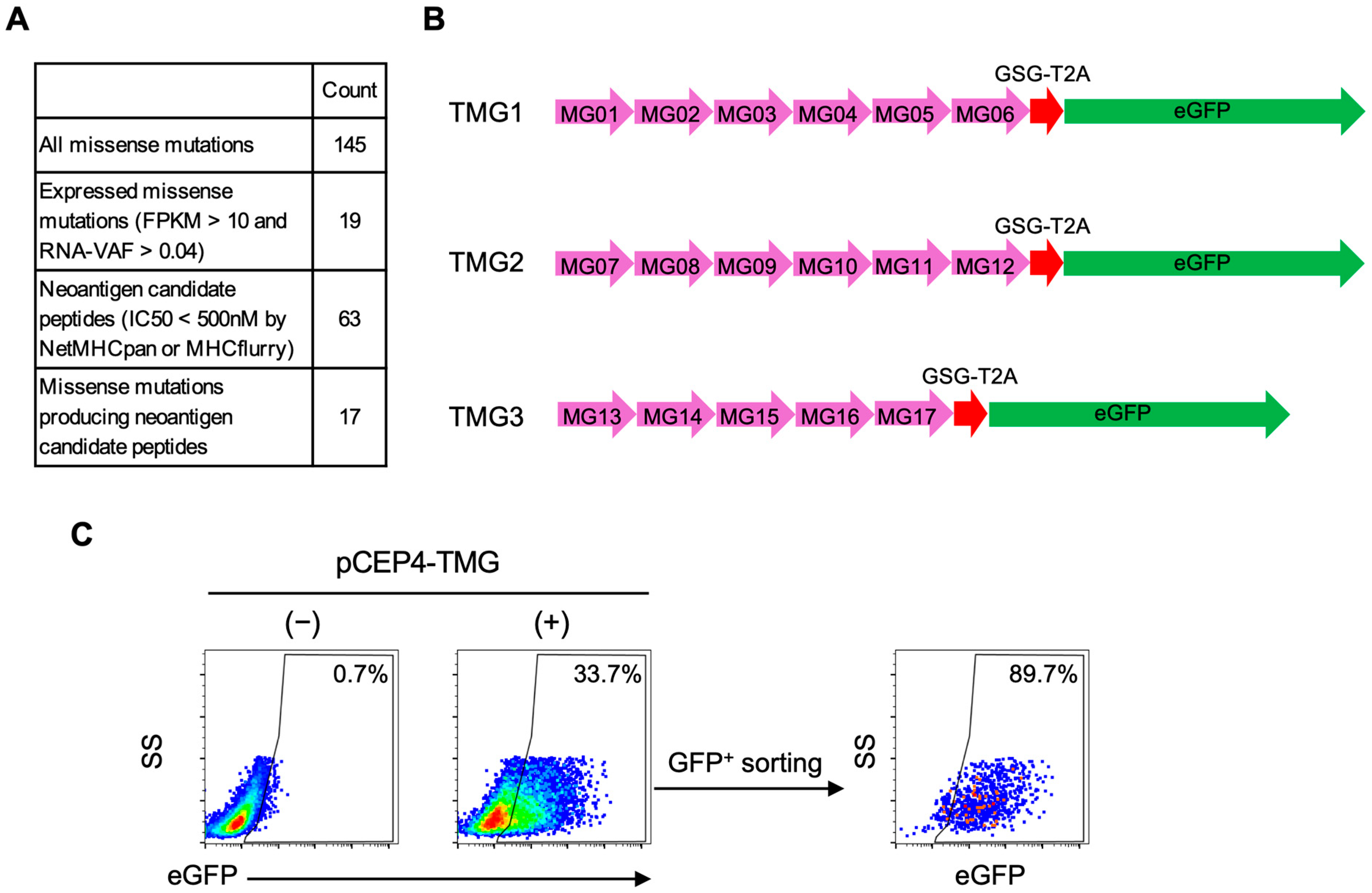

To overcome these obstacles, we developed NeoPAIR-T (Neoantigen–TCR Pairing Assay using reporter T cells), a patient-specific, multiplexed system for the parallel identification of true neoantigens and their cognate TCRs. NeoPAIR-T uniquely integrates four key features that enable multiplexed and quantitative functional screening: (i) a luciferase/eGFP dual-reporter for sensitive, quantitative assessment of TCR activation; (ii) a TCRα-knockout combined with targeted knock-in of candidate TCRαβ into the endogenous TCRβ CDR3 region, preventing TCR mispairing and ensuring physiological expression; (iii) Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-immortalized autologous B-cell APCs combined with tandem minigene (TMG) libraries, which offer a practical and widely used platform for presenting large numbers of candidate neoantigens in vitro, while still differing in aspects of antigen processing and HLA presentation compared with autologous tumor cells; and (iv) parallelized testing of multiple TCR–antigen pairs. This optimized NeoPAIR-T system enables efficient, multiplexed functional validation of predicted neoantigens and their specific TCRs in a physiologically relevant context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines, Culture Conditions, and Reagents

Jurkat E6-1 cells (TIB-152, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and all derivative lines were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (FujiFilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO

2 at 37 °C. 293FT cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were maintained in DMEM (high glucose, FujiFilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Epstein–Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (EBV-LCLs) were established by infecting PBMCs with the B95-8 supernatant and maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 20% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Jurkat E6-1 and EBV-LCL tested negative for mycoplasma by a PCR-based assay. Experiments were performed using early-passage cells (≤10 passages after thawing). A comprehensive list of reagents used in this study is provided in

Table S1.

2.2. Preparation of Guide RNA (gRNA) and Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes

The target sites for all CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) are depicted in

Figure S1A and the crRNA sequences are listed in

Table S2 [

18]. Alt-R crRNAs and Alt-R tracrRNA were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA, USA) and reconstituted in Nuclease-Free Duplex Buffer (IDT) to a final concentration of 100 µM. To form the gRNA, equimolar amounts of crRNA and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) were combined, heated to 95 °C for 5 min and then annealed by incubating at room temperature for 10 min. For RNP assembly, 3 μL (150 pmol) of the prepared gRNA was gently mixed with approximately 2 μL (60 pmol) of TrueCut Cas9 Protein v2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at room temperature for 10 min to allow for complex formation.

2.3. Lentivirus Production

A DNA construct encoding human CD8α and CD8β, linked by a T2A self-cleaving peptide sequence (human CD8α-T2A-CD8β), was synthesized by IDT. This synthesized gene was subsequently cloned into the pLenti-III-EF1alpha lentiviral vector (

Figure S1B, Applied Biological Materials Inc., Richmond, BC, Canada).

For lentivirus production, 293FT cells were co-transfected with the pLenti-III-EF1alpha-human CD8α-T2A-CD8β plasmid and the ViraPower Lentiviral Packaging Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The virus-containing supernatant was harvested at 48 h post-transfection. The supernatant was centrifuged to remove cell debris and then concentrated using the Peg-It Lentivirus Concentration Reagent (System Biosciences, LLC, Palo Alto, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting viral pellet was resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium at 1/10th of the original volume, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C until use.

2.4. Establishment of the Reporter T Cell Line

The parental Jurkat E6-1 cells were characterized by flow cytometry as CD3+, CD4+, CD8−, TCRαβ+, and FAS+. A series of genetic modifications were performed as follows to establish the reporter T cell line.

First, the CD4 and FAS genes were sequentially disrupted (

Figure S1). To knock out each gene, 4 × 10

5 cells were washed with DPBS and resuspended in 20 µL of SE Cell Line Nucleofector Solution (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). A preassembled RNP complex (5 µL) and 0.8 µL of Alt-R Cas9 Electroporation Enhancer (IDT) were added to the cell suspension. Electroporation was performed using program CL-120 on the 4D-Nucleofector System (Lonza). Immediately after electroporation, the cells were transferred to prewarmed culture medium. The CD4 gene was knocked out first, and the CD4-negative population was isolated by cell sorting on an SH800S cell sorter (Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Subsequently, the FAS gene was knocked out in these cells using the same procedure, followed by cell sorting to isolate the CD4

−FAS

− population.

Next, the CD4−FAS− cells were transduced with the human CD8-expressing lentivirus in the presence of 6 µg/mL polybrene. Transduced cells were selected with 1 µg/mL puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the CD8-positive population was subsequently sorted.

CD8-expressing cells were transduced with lentiCas9-Blast lentivirus (

Figure S1B, Addgene #52962-LV, Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA) [

19]. To knock out the T cell receptor alpha constant (TRAC) gene, these Cas9-expressing cells were electroporated (program CL-120) with a gRNA targeting TRAC (

Table S2), without the addition of exogenous Cas9 protein. CD3-negative cells were then enriched by cell sorting.

Finally, these cells were transduced with a lentiviral NFAT-Luciferase-eGFP reporter construct (

Figure S1B, BPS Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) at MOI of 20 and selected with 2 mg/mL G418 (FujiFilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation). To enrich functionally responsive cells, the reporter T cells were stimulated overnight with 2 ng/mL PMA and 100 nM ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by sorting for the eGFP-positive population.

We did not perform quantitative per locus indel-efficiency measurements or experimental off-target profiling. A formal stability study across passages was not conducted.

2.5. Patient and Clinical Samples

A patient with non-small cell lung carcinoma was included in this study after written informed consent had been obtained. Tumor tissue and peripheral blood samples were obtained from the patient. The study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Boards of the Faculty of Medicine and Graduate School of Medicine of The University of Tokyo (G3545) and Kindai University Faculty of Medicine (R05-124).

2.6. Single-Cell RNA/TCR-Sequencing (RNA/TCR-Seq)

Fresh tumor tissue was obtained from one patient with lung squamous cell carcinoma (LK117) at the time of surgical resection. Tumor tissue was dissociated into a single-cell suspension using the Tumor Dissociation Kit, human, in combination with gentleMACS Dissociators (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After staining the cells with FITC-anti-human CD8, Pacific Blue-anti-human CD4 antibodies (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich), live (propidium iodide

−) CD4

−CD8

+ T cells were then enriched by a SH800S cell sorter (

Figure S2, Sony Corporation). Single-cell RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) combined with TCR repertoire analysis was performed using the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 5′ v2 Reagent Kit (10x Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA) and Chromium Single Cell Human TCR Amplification Kit (10x Genomics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 10,000 target cells were loaded for library construction. Libraries for both gene expression and paired TCRα/β (V(D)J) sequences were generated and pooled at a 9:1 ratio, followed by sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) to achieve a depth of approximately 50,000 read pairs per cell. Raw sequencing data were processed using Cell Ranger (10x Genomics, version 7.0.0) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reads were aligned to the GRCh38 human reference genome using the Cell Ranger pipeline, and gene expression matrices were generated after filtering and unique molecular identifier (UMI) counting. TCR V(D)J sequences were simultaneously assembled using the Cell Ranger V(D)J pipeline, yielding paired α and β chain clonotypes.

Single-cell RNA-Seq data were analyzed using Seurat (version 5.3.0) in R. Low-quality cells were removed by filtering out those with fewer than 200 or more than 5000 detected genes, or with mitochondrial transcript content exceeding 10%. The data were then log-normalized and scaled. V(D)J sequencing data were integrated using scRepertoire (version 1.12.0) [

20], and only cells with both productive TCRα and TCRβ chains were retained for downstream analysis. The top 40 most frequent TCR clonotypes are listed in

Table S4. CXCL13 expression scores were calculated from normalized and scaled expression data, and neoTCR8 signature scores were computed by single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA, GSVA package version 1.50.5) using normalized expression values based on the previously defined gene set reported by Lowery et al. [

13].

2.7. Generation of Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Templates

Eight candidate TCR sequences were obtained from the Loupe V(D)J Browser (version 5.0.1, 10x Genomics) and listed in

Table S5. DNA cassettes containing TCRα-T2A-TCRβ sequences flanked by approximately 900 bp homology arms were synthesized by IDT. For multiplex screening, a fluorescent barcode–coding one of four fluorescent proteins (mCherry, mTagBFP2, Katushka, or moxCerulean3 [

21,

22])–together with P2A was inserted upstream of the TCR cassette. These cassettes were cloned into the pUC57 plasmid vector using the In-Fusion Snap Assembly Master Mix (Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan). Plasmid sequences were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The entire construct was amplified from the plasmid using KOD One polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) with M13 primers (

Table S3), and the PCR product was purified using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (Takara Bio Inc.) to be used as an HDR template.

2.8. CRISPR-Mediated Knock-In in Reporter T Cells

Cassettes encoding NY-ESO1-specific TCR (1G4) or LK117-derived TCRs with fluorescent barcodes were introduced into the reporter T cells via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in. In each well of a 24-well plate, 1 mL of culture medium was supplemented with 1.4 µL of Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (IDT) and prewarmed. Reporter T cells (4 × 105) were resuspended in 20 µL of SE Cell Line Nucleofector Solution. A gRNA targeting the endogenous TCR β CDR3 region (CDR3β), 2 µg HDR template DNA for the NY-ESO1-specific TCR, and an equimolar pool (total 2 µg; 0.5 µg each) of four templates encoding distinct TCRs with unique fluorescent barcodes for multiplex knock-in were added. After a 2 min incubation, the mixture was electroporated using the 4D-Nucleofector System (program CL-120) and transferred to the prewarmed medium.

Knock-in Efficiency was assessed 72 h post-editing by flow cytometry as the percentages of CD3

+ cells. Mean knock-in efficiency was 13.6% (range, 5–20%) for NY-ESO-1 specific TCRs and 6% (range, 5–6%) in LK117 TCR pools, and per-TCR compositions within CD3

+ gate are summarized in

Table S5. Prior to functional assays, CD3

+ reporter T cells were purified on an SH800S cell sorter. For co-culture experiments with TMG-transfected EBV-LCLs, the barcode composition of the reporter pools was re-checked (

Figure S5). We did not determine mono- versus bi-allelic editing frequencies in reporter T cells.

2.9. Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES)

DNA from tumor and matched normal tissues of the patient was subjected to WES. Sequencing reads were trimmed using trim-galore and aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh38) with BWA-MEM (v0.7.17) [

23]. Somatic variants were called using Mutect2 (GATK v4.1.9) and Strelka [

24], and germline variants were identified with HaplotypeCaller (GATK v4.1.9). The resulting variant calls were further annotated with ENSEMBL-VEP [

25] and visually confirmed in Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV, v2.19.5).

2.10. Bulk RNA-Seq

Total RNA from tumor tissue was analyzed by RNA-Seq. Reads were trimmed with trim-galore and mapped to GRCh38 using STAR (v2.7.8a) [

26]. Gene expression levels were quantified with featureCounts (v1.6.4) [

27], and fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) values were calculated in R. RNA-variant allele frequency (VAF) values were obtained by counting reference and variant-supporting reads at mutation sites using bam-readcount on RNA-Seq BAM files.

2.11. HLA Typing and Neoantigen Prediction

HLA class I alleles were inferred from WES data using OptiType [

28]. Neoantigen candidates were predicted using pVACseq [

29], integrating WES-derived somatic mutations with RNA expression data. Candidate peptides were filtered based on expression (FPKM > 10), VAF (RNA-VAF > 0.04) and predicted MHC binding affinity (IC

50 < 500 nM, 9–10-mer peptides, MHCflurry [

30] or NetMHCpan [

31]).

2.12. Preparation of TMG Constructs and Transfection into EBV-LCLs

For each candidate missense mutation, we designed a DNA fragment encoding a 31–amino acid consisting of the mutated residue flanked by 15 amino acids on each side, which we designated a minigene. Five or six minigenes were concatenated in frame to generate TMG constructs without signal sequences or linker sequences, followed by T2A-eGFP for bicistronic expression. The corresponding DNA fragments were synthesized and cloned into the pCEP4 plasmid (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using In-Fusion Snap Assembly Master Mix according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Takara Bio Inc.).

Autologous EBV-LCLs (2–4 × 10

6) were electroporated with the TMG plasmids using a 4D-Nucleofector X Unit with the SE Cell Line 4D-Nucleofector X Kit S (Lonza) and program DH-100. Immediately after electroporation, cells were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C, then transferred to prewarmed complete medium. At 24 h post-electroporation, hygromycin B (50 µg/mL) was added for selection and 2 days later, eGFP

+ population was sorted on an SH800S cell sorter. The percentage of eGFP

+ cells and eGFP mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) after sorting are shown in

Figure S3.

2.13. Co-Culture of EBV-LCLs with Reporter T Cells

HLA-A*02:01–positive EBV-LCLs (1 × 105) were resuspended in RPMI-1640 with 20% FBS and pulsed with NY-ESO-1 peptide (SLLMWITQV; 10−5–10−12 M, 10-fold serial dilutions) for 2 h at 37 °C, washed three times, and co-cultured overnight (12–16 h) with 1 × 105 1G4 TCR-expressing reporter T cells. For TMG-based screening and epitope mapping, reporter T cells carrying candidate TCR pools were co-cultured under identical conditions with LK117 EBV-LCLs expressing TMG constructs or with EBV-LCLs pulsed with the indicated synthetic peptides. After co-culture, supernatants were collected and IL-2 was quantified with IL-2 Human Uncoated ELISA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were resuspended in medium containing 150 µg/mL luciferin (AAT Bioquest, Pleasanton, CA, USA) and bioluminescence was measured on a plate reader (TriStar LB941, Berthold Technologies GmbH & Co. KG, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Then the cells were stained with Pacific Blue anti-CD19 and PE anti-CD69 antibodies (BioLegend) and acquired on the CytoFLEX S flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) for eGFP expression and CD69 upregulation on the CD19− reporter T cells. Dose–response curves were fitted using a four-parameter logistic model in GraphPad Prism (v10.2.2, Sigmoidal, 4PL, X is concentration) to derive EC50 values.

For luciferase readouts, a positivity threshold was defined on each plate using on-plate negative controls: six wells containing reporter T cells co-cultured with untransfected, peptide-free EBV-LCLs. A response was called positive if its luminescence exceeded the plate-specific mean plus two standard deviations (mean + 2 SD) of these background wells. Each condition was assayed in one well per experiment (no technical replicates). The experiment was independently repeated twice. Given the small sample size, confidence intervals were not calculated.

2.14. Co-Culture of K562-Based Mono-Allelic HLA APCs with Reporter T Cells

HLA-B*54:01 and HLA-C*14:02 cDNAs were obtained from the RIKEN BioResource Research Center (Tsukuba, Japan). Each allele was subcloned into the pLenti-III-EF1α vector, and lentiviral particles were produced and concentrated as described above. K562 cells (JCRB Cell Bank, Osaka, Japan) were transduced and stained with APC anti-human HLA-A,B,C antibody; HLA-positive cells were isolated by cell sorting to generate mono-allelic K562 APC lines.

For co-culture assays, 1 × 105 HLA-expressing K562 cells were pulsed with the indicated peptide at 1 μM for 2 h at 37 °C, then co-cultured overnight (12–16 h) with 1 × 105 reporter T cells. Luciferase activity was quantified as described above.

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed and validated NeoPAIR-T, a novel, integrated platform designed to overcome a major bottleneck in neoantigen-based immunotherapy—the functional identification of authentic tumor-specific neoantigens recognized by cognate TCRs. NeoPAIR-T, the overall workflow of which is illustrated in

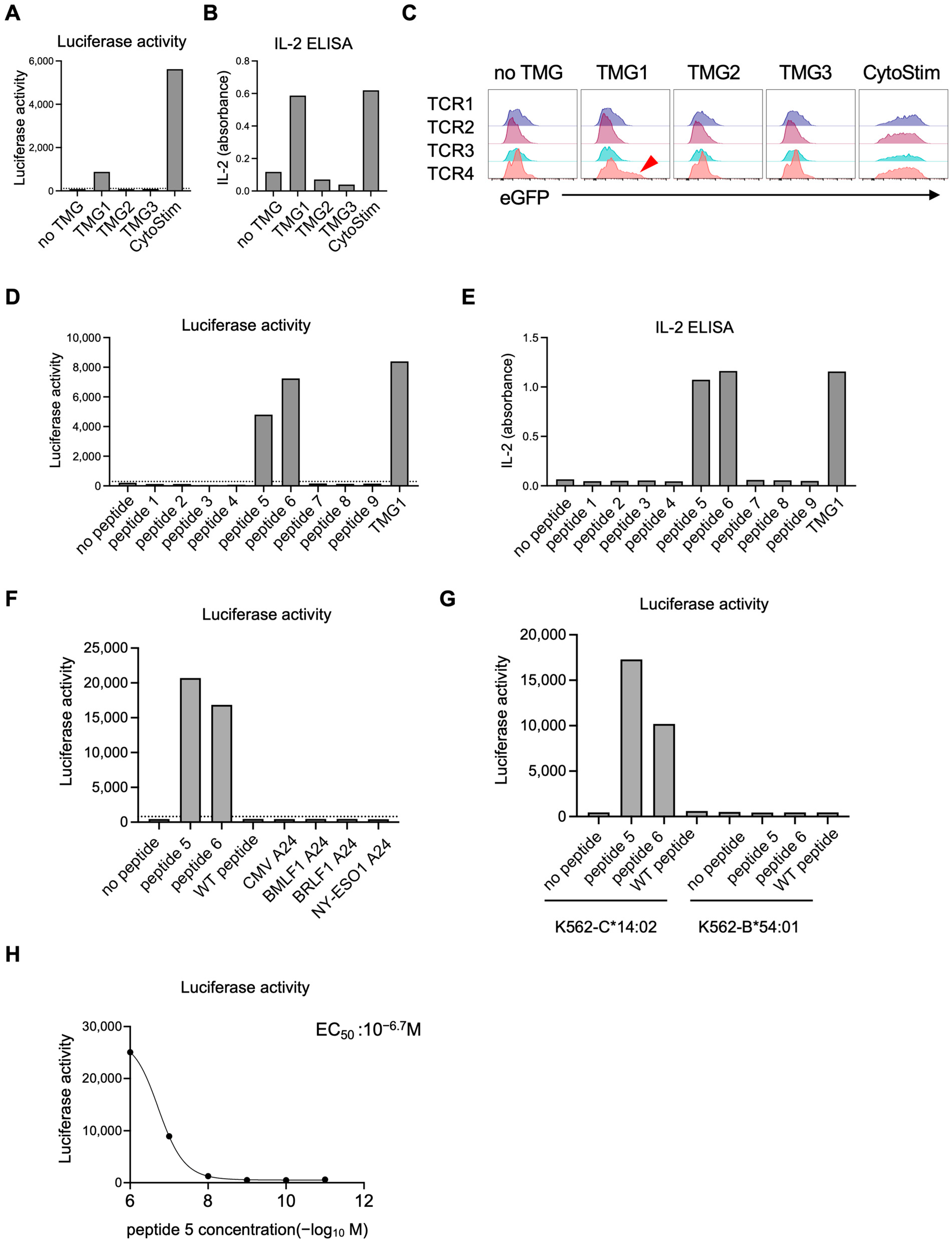

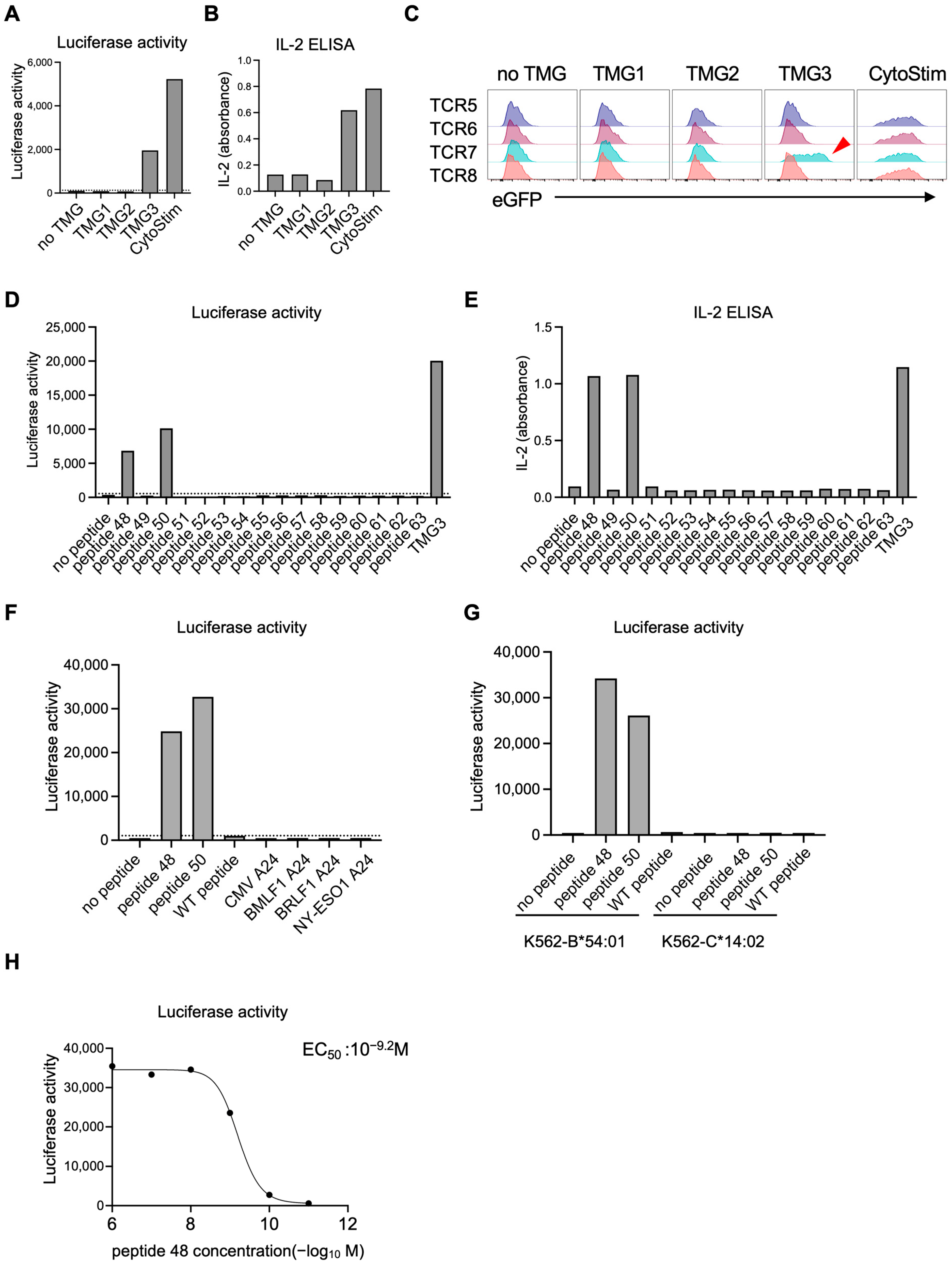

Figure 3, enables multiplexed identification of bona fide neoantigen–TCR pairs by systematically integrating transcriptome-guided prediction of tumor-specific TCRs with MHC-binding–based prediction of candidate neoantigens, their efficient expression in autologous APCs, and functional screening using reporter T cells. This approach allows the discrimination of true neoantigen-specific T cells from bystander T-cell noise and the experimental confirmation of authentic neoantigen–TCR interactions among numerous in silico predicted candidates.

A primary challenge in functional validation of neoantigen–TCR interactions arises from the low accuracy of in silico prediction of neoantigen peptides, which generates a vast number of false-positive candidates. Indeed, a meta-analysis of 13 studies reported that fewer than 2.7% of neopeptides prioritized by bioinformatics pipelines were actually recognized by patient-derived T cells [

9,

38]. Similarly, a large-scale benchmarking study by the Tumor Neoantigen Selection Alliance (TESLA) consortium demonstrated a success rate of only about 6% [

39]. Consistent with these reports, in our screen 4 of 63 predicted peptides (6.3%) elicited measurable TCR-dependent activation, reinforcing that current prediction algorithms remain insufficiently precise. This consistently low predictive accuracy necessitates the synthesis and testing of hundreds to thousands of candidate peptides, thereby making a robust and efficient experimental validation process indispensable for distinguishing the few truly immunogenic neoantigens from the many non-functional predictions [

16,

40]. To address this limitation, we began with 145 mutated genes in LK117, from which in silico prediction identified 63 candidate peptides derived from 17 missense mutations. Minigenes from the 17 missense mutations were concatenated into three TMG constructs for primary screening. Whereas a peptide-synthesis-dependent approach would require synthesizing all 63 candidate peptides, epitope mapping in our workflow required synthesis of only 25 peptides (9 from TMG1 and 16 from TMG3,

Figure S4), thereby improving overall efficiency. To further improve accuracy, future work will incorporate presentation-aware prioritization (e.g., proteasomal cleavage, TAP transport and peptide–HLA complex stability), and where available, cross-checks with immunopeptidomics to mitigate EBV-LCL presentation bias. At the same time, these intrinsically low hit-rates highlight the necessity of functional screening platforms capable of testing large candidate sets efficiently. The NeoPAIR-T system described here directly addresses this methodological gap by providing an efficient and versatile workflow for pairing neoantigens with cognate TCRs, thereby overcoming one of the central bottlenecks in neoantigen discovery.

In the LK117 case, a standard peptide-synthesis-dependent assay would require 8 TCRs × 63 peptides = 504 wells. By contrast, NeoPAIR-T condensed the screen to 2 pools × 3 TMGs co-cultures (6 wells), followed by peptide-level deconvolution for the two hit TCRs (9 and 16 wells), totaling 31 wells—an approximately 94% reduction—while delivering two quantitative readouts (luciferase and eGFP) from the same wells.

Our platform also addresses another critical set of challenges in functional validation: the reliability and throughput of TCR assessment. Traditional TCR transduction methods using retroviral or lentiviral vectors suffer from two inherent problems. The first is mispairing with endogenous TCR chains, which poses a risk of unpredictable off-target reactivities [

41,

42]. The second is random genomic integration, which, being a process governed by Poisson statistics, inevitably generates a heterogeneous cell population with variable transgene copy numbers [

43]. This inherent heterogeneity leads to unpredictable functional variability and precludes clean, multiplexed screening from a pooled library. To mitigate these issues, we combine TCRα-knockout with a targeted knock-in into the endogenous TCRβ CDR3 region. Using this approach, we established NY-ESO-1-specific 1G4 TCR knock-in reporter T cells, which showed luciferase and eGFP induction, CD69 upregulation and IL-2 secretion upon stimulation with the HLA-A*02:01-restricted NY-ESO1 peptide, with EC

50 values similar to those reported previously [

18]. This approach not only ensures physiological, mispairing-free expression but also guarantees monoallelic, single-copy integration. This “one-cell, one-TCR” homogeneity is fundamental to our multiplexing strategy, making it possible to barcode each TCR with a distinct fluorescent protein and screen multiple candidates in parallel, thereby drastically accelerating the validation workflow. In practice, this configuration enables functional screening of four distinct TCR–T cell clones against a single antigen-presenting cell expressing approximately ten candidate neoantigens, allowing efficient identification of matched neoantigen–TCR pairs with minimal experimental complexity.

In this study, we prioritized TCR candidates based on two key features associated with tumor reactivity: high clonal expansion and transcriptomic signatures such as CXCL13 expression and the NeoTCR8 signature score. Functional validation of two neoantigen-reactive TCRs (TCR4 and TCR7) selected through this data-driven approach using the NeoPAIR-T platform provides proof of concept for the feasibility and robustness of our integrated workflow. However, this validation was performed in a single case, and the optimal criteria for prioritizing TCRs remains an area of active investigation. While our results support the utility of transcriptomic markers, other studies, particularly in lung cancer, have highlighted the importance of high clonal frequency in addition to CD39 protein and CXCL13 mRNA expressions in tumor-reactive T cells [

32]. Therefore, further studies across multiple patients and cancer types are necessary to delineate the relative importance and predictive value of transcriptomic signatures versus clonal expansion for prioritizing TCR candidates.

Of the eight candidate TCRs evaluated, only two were confirmed to recognize cognate neoantigens. While a fair evaluation requires comparison to an appropriate baseline (e.g., random TCR sampling), the limited success rate is consistent with previous reports that the majority of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are bystander T cells lacking tumor specificity [

11]. However, this outcome is also intrinsically linked to the design of our study, in which our neoantigen search was restricted to missense mutations. Indeed, other classes of somatic alterations and aberrant expression events—such as frameshift mutations, gene fusions, alternative splicing events, intron retention, translation from non-canonical open reading frames, and the expression of endogenous retroelements—are known to be important sources of neoantigens [

40].

This particular limitation highlights a key future strength of our platform: its flexibility. The EBV-LCL-based TMG system readily accommodates these diverse mutation types into TMG constructs for evaluation within the same experimental framework. For example, we will encode the mutated open reading frame from the variant codon through to the first in-frame stop codon for frame-shift mutation. For gene fusions, if donor and acceptor genes are in-frame, a junction-spanning minigene centered on the breakpoint can be used; if the fusion introduces a frameshift, we will encode from the breakpoint to the first in-frame stop codon, analogous to the frameshift strategy. By expanding our search to include these variants in future studies, we anticipate the identification of broader and previously overlooked neoantigens and their cognate TCRs.

From a NeoPAIR-T-validated epitope–TCR pair, off-target risk should be reduced using complementary approaches, such as alanine scanning and cross-reactivity assessment against normal-cell panels. In parallel, manufacturability should be considered—either engineering TCR-T in autologous primary T cells or selecting and preparing appropriate vaccine modalities—as depicted by the intended translational path.

This study has several limitations. First, experimental validation was conducted in a single patient, which constrains generalizability; multi-patient and multi-cancer-type cohorts will be required to fully establish robustness, reproducibility, and clinical applicability. At the same time, the integrated platform developed here provides a foundation for such future work. By combining four spectrally distinct TCR reporter cell lines with autologous B-cell APCs that present peptides on the patient’s complete HLA repertoire and are engineered to express EBV-vector-based minigenes for antigen delivery, we created a flexible system for neoantigen interrogation. This architecture enables parallel, high-resolution functional assessment of diverse neoantigens and is expected to serve as a broadly useful discovery engine as we expand NeoPAIR-T to additional patients and cancer types. Second, although EBV-LCLs provide a practical and widely used APC platform for in vitro antigen presentation and enabled efficient screening in this study, EBV transformation may modify certain cellular characteristics, and differences from autologous tumor cells cannot be fully excluded. Therefore, validation using patient-derived tumor cells or tumor organoids will ultimately be required to confirm antigen presentation and functional recognition in a physiologically relevant setting. Such experiments were not feasible here due to limited availability of tumor material. Third, although the use of Jurkat-derived reporter cells enabled efficient identification of neoantigen-reactive TCRs, the present study did not include downstream validation using primary human T cells engineered with the identified TCRs. Such follow-up experiments, including assessment of cytotoxicity or cytokine responses against autologous tumor cell lines or patient-derived organoids, will be essential steps for advancing toward cancer vaccine development or TCR–T cell therapy. The current study addresses the step immediately before that stage: resolving one of the major bottlenecks in neoantigen immunology by establishing an efficient and versatile workflow for pairing neoantigens with their cognate TCRs. Our goal was to build a robust discovery engine, and future studies using primary T cells and patient-derived tumor materials will further extend the translational applicability of NeoPAIR-T. Fourth, we did not perform a formal passage-stability study of the Jurkat reporter line (e.g., longitudinal assessment of reporter responsiveness, phenotype, or knock-in retention across passages). Locus-specific copy/allelic assessment, per-locus indel quantification, experimental off-target profiling, and RT-qPCR of TMG transcripts were also not performed. On-target integration was inferred functionally from CD3 reconstitution, and TMG expression was monitored phenotypically by eGFP expression. Finally, because each TMG encodes multiple minigenes, intra-TMG competition for MHC class I loading may underrepresent low-affinity yet biologically relevant epitopes, resulting in potential false negatives. Although we diversified predicted HLA restrictions within each construct, competition-related false negatives cannot be excluded.