Hypothalamic Microglia as Dual Hubs Orchestrating Local and Systemic Homeostasis in the Periphery–Central–Periphery Axis

Highlights

- Microglial Role in Homeostasis: The article emphasizes that hypothalamic microglia play a crucial role in regulating both local and systemic homeostasis, acting as key mediators between the central nervous system and peripheral systems.

- Pathological Responses: It highlights that under pathological conditions, microglia can modulate inflammatory responses and initiate repair mechanisms, which are vital for maintaining homeostasis during disease.

- Neuroimmune Interaction: The findings suggest that understanding microglia’s role in neuroimmune interactions could lead to new therapeutic strategies for conditions involving dysregulation of homeostasis, such as metabolic disorders and chronic inflammation.

- Potential for Targeted Treatments: By targeting microglial pathways, there is potential for developing treatments that could restore balance in neuroendocrine and immune functions, enhancing recovery from various diseases.

Abstract

1. Background

2. Hypothalamic Microglia Activation by Afferent Stimuli via the Periphery–Brain Axis

2.1. Microglia Activation by Lipid Metabolism-Related Products

2.2. Microglia Modulation by Hormonal Signaling

2.3. Microglia Regulation by Remote Gut Microbiota and Microbial Toxins

3. Mechanistic Insights of Microglia as Central Hubs in Hypothalamic Neuro-Immune-Endocrine-Metabolic Integration

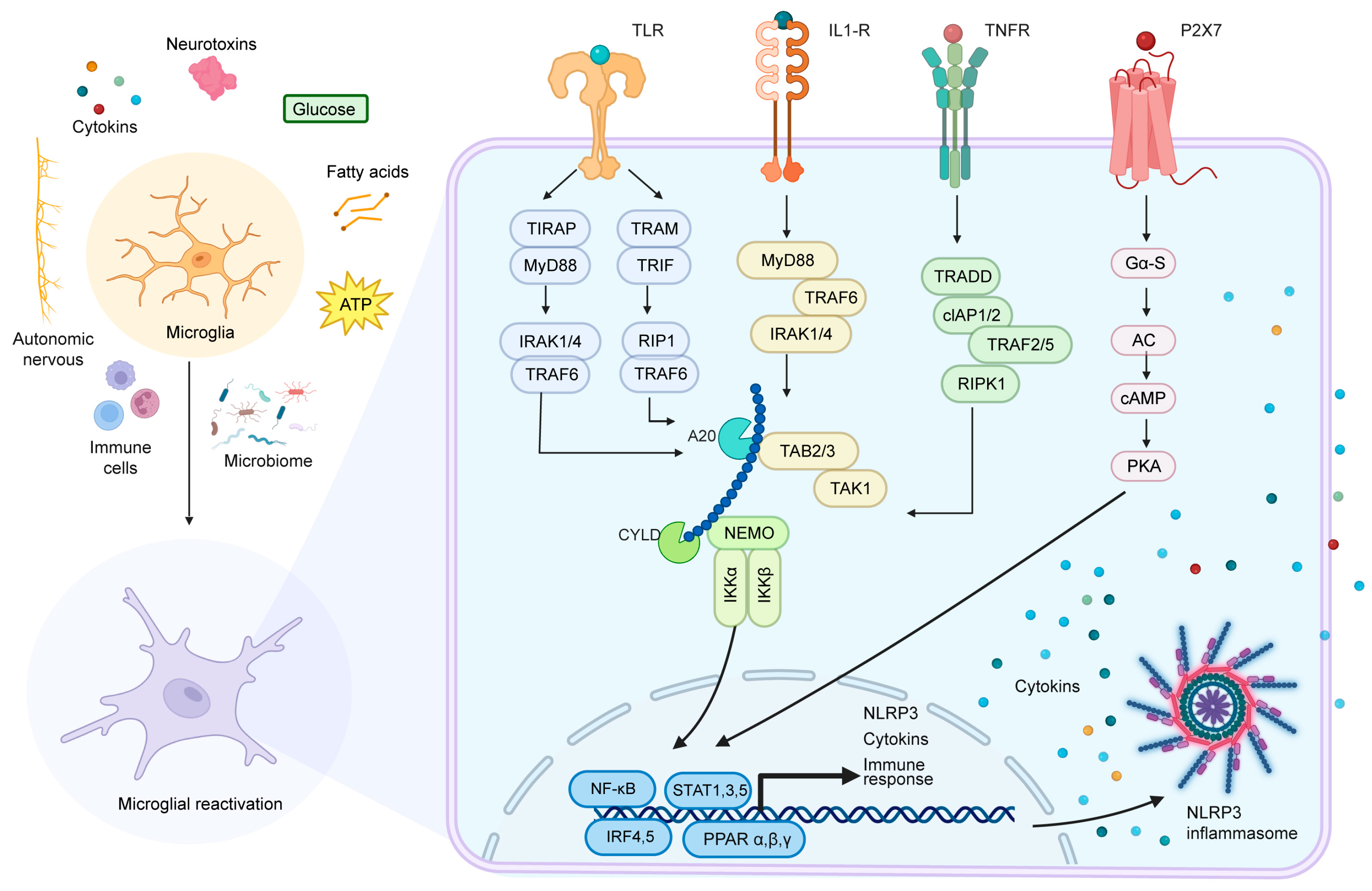

3.1. Immunomodulatory Mechanisms of Hypothalamic Microglia

3.2. Activity-Dependent Synaptic Pruning by Microglia

3.3. Extracellular Matrix Remodeling by Direct Microglial Phagocytosis

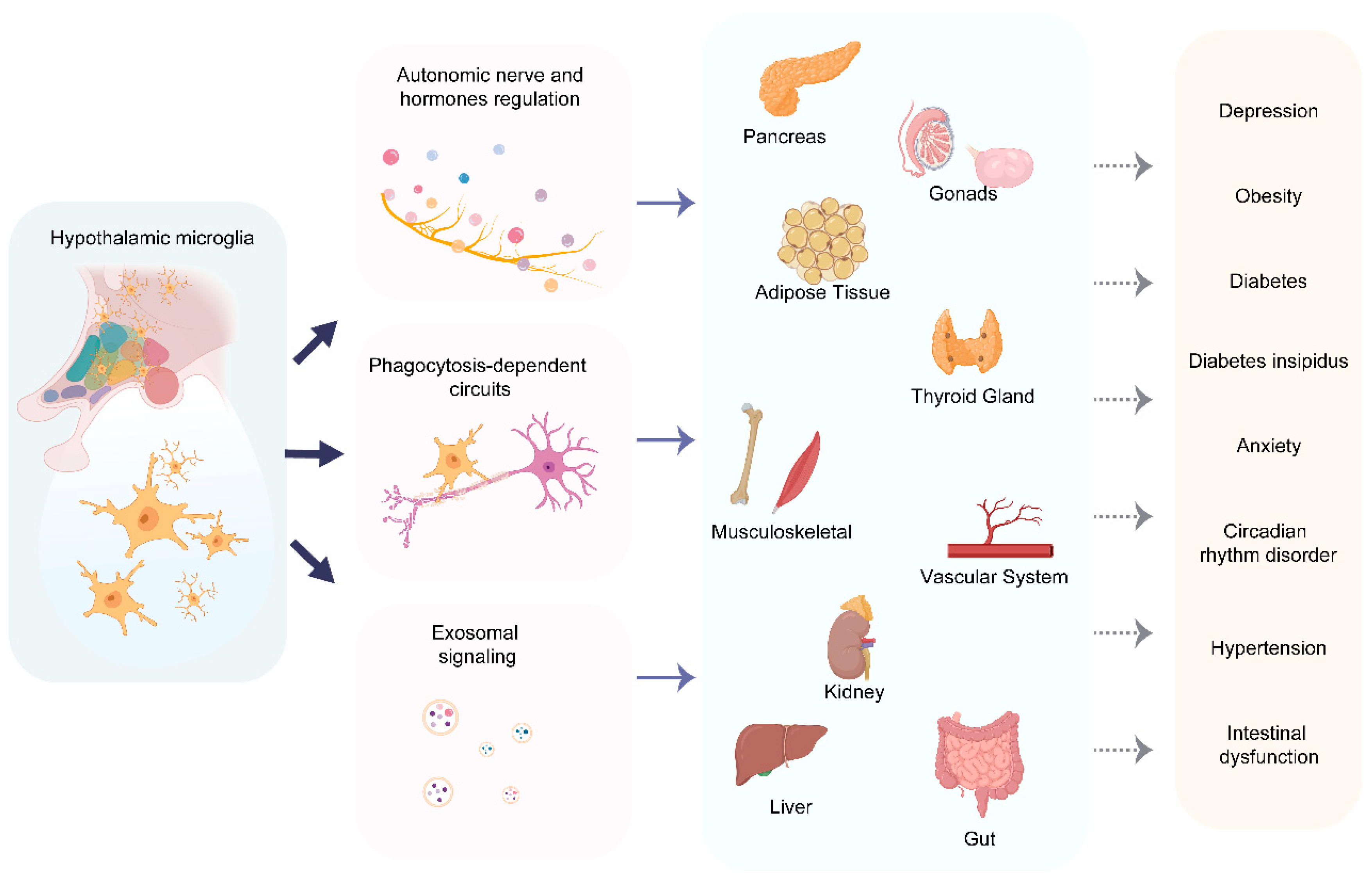

4. Targets and Regulatory Functions of Hypothalamic Microglia as Orchestrator of the Center-Periphery Axis

4.1. Autonomic Nervous System Regulation

4.1.1. Parasympathetic Modulation of Visceral Function

4.1.2. Sympathetic Activation in Regulating Peripheral Organ Functions

4.2. Neuroendocrine Signaling Networks

4.2.1. HPA Axis Dynamics in Regulating Metabolic Homeostasis

4.2.2. Hypothalamic Microglia-Neural Control of Pancreatic β Cells

4.3. Immune–Metabolic Crosstalk via Exosomal Signaling

4.4. A Paradigm of Microglial Dysregulation: The Case of Long COVID

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CRH | corticotropin-releasing hormone |

| TRH | thyrotropin-releasing hormone |

| GnRH | gonadotropin-releasing hormone |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| PVN | paraventricular nucleus |

| MCP-1 | monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| PRRs | pattern recognition receptors |

| HFD | high-fat diet |

| CVOs | circumventricular organs |

| ME | median eminence |

| PA | palmitate |

| POMC | pro-opiomelanocortin |

| AgRP | agouti-related peptide |

| HVZ | ventricular zone |

| LepRb | long-form leptin receptor |

| ARC | arcuate nucleus |

| HPA | hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| GR | glucocorticoid receptor |

| DAMP | damage-associated molecular pattern |

| AMPA | α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid |

| SCFAs | short-chain fatty acids |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| HDAC | histone deacetylase |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharides |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartic acid |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| PNNs | perineuronal nets |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| SDN | sexually dimorphic nucleus |

| POA | preoptic area |

| TBI | traumatic brain injury |

| NETs | neutrophil extracellular traps |

| HSL | hormone-sensitive lipase |

| NPY | neuropeptide Y |

References

- Fong, H.; Zheng, J.; Kurrasch, D. The structural and functional complexity of the integrative hypothalamus. Science 2023, 382, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Choi, S.-Y. Arcuate Nucleus of the Hypothalamus: Anatomy, Physiology, and Diseases. Exp. Neurobiol. 2023, 32, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, M.H.; Reddy, V.; Bollu, P.C. Neuroanatomy, Hypothalamus. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, P.M. Anatomy of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. J. Clin. Pathol. Suppl. (Assoc. Clin. Pathol.) 1976, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaab, D.F.; Hofman, M.A.; Lucassen, P.J.; Purba, J.S.; Raadsheer, F.C.; Van de Nes, J.A. Functional neuroanatomy and neuropathology of the human hypothalamus. Anat. Embryol. 1993, 187, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudás, B. Anatomy and cytoarchitectonics of the human hypothalamus. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2021, 179, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppari, R.; Ichinose, M.; Lee, C.E.; Pullen, A.E.; Kenny, C.D.; McGovern, R.A.; Tang, V.; Liu, S.M.; Ludwig, T.; Chua, S.C., Jr.; et al. The hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: A key site for mediating leptin’s effects on glucose homeostasis and locomotor activity. Cell Metab. 2005, 1, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Duque, V.; Phillips, N.; Mecawi, A.S.; Cunningham, J.T. Spatial transcriptomics reveal basal sex differences in supraoptic nucleus gene expression of adult rats related to cell signaling and ribosomal pathways. Biol. Sex Differ. 2023, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daviu, N.; Füzesi, T.; Rosenegger, D.G.; Rasiah, N.P.; Sterley, T.-L.; Peringod, G.; Bains, J.S. Paraventricular nucleus CRH neurons encode stress controllability and regulate defensive behavior selection. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClellan, K.M.; Parker, K.L.; Tobet, S. Development of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. Front. Neuroendocr. 2006, 27, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Lee, E.J.; Lim, S.B. Single-cell and spatial omics: Exploring hypothalamic heterogeneity. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 20, 1525–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnavion, P.; Mickelsen, L.E.; Fujita, A.; de Lecea, L.; Jackson, A.C. Hubs and spokes of the lateral hypothalamus: Cell types, circuits and behaviour. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 6443–6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saper, C.B.; Scammell, T.E.; Lu, J. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Nature 2005, 437, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, M.A.; Smith, R.G.; Diano, S.; Tschöp, M.; Pronchuk, N.; Grove, K.L.; Strasburger, C.J.; Bidlingmaier, M.; Esterman, M.; Heiman, M.L.; et al. The distribution and mechanism of action of ghrelin in the CNS demonst rates a novel hypothalamic circuit regulating energy homeostasis. Neuron 2003, 37, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugrumov, M.V. Developing brain as an endocrine organ: A paradoxical reality. Neurochem. Res. 2010, 35, 837–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, G.; Redgate, E.S.; Royce, P.C. Hypothalamus, adenohypophysis and adrenal cortex. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1958, 20, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbridge, S.; Stewart, I.; Placzek, M. Development of the Neuroendocrine Hypothalamus. Compr. Physiol. 2016, 6, 623–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, N.; Del Corpo, A.; Diorio, J.; McAllister, K.; Sharma, S.; Meaney, M.J. Maternal programming of sexual behavior and hypothalamic-pituitary-gon adal function in the female rat. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, A.; Laviano, A.; Meguid, M.M. Hypothalamic integration of immune function and metabolism. Prog. Brain. Res. 2006, 153, 367–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, X. Physiology of the autonomic nervous system. Rev. Neurol. 2002, 35, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buijs, R.M.; Chun, S.J.; Niijima, A.; Romijn, H.J.; Nagai, K. Parasympathetic and sympathetic control of the pan-creas: A role for th e suprachiasmatic nucleus and other hypothalamic centers that are invo lved in the regulation of food intake. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001, 431, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klieverik, L.P.; Janssen, S.F.; van Riel, A.; Foppen, E.; Bisschop, P.H.; Serlie, M.J.; Boelen, A.; Ackermans, M.T.; Sauerwein, H.P.; Fliers, E.; et al. Thyroid hormone modulates glucose production via a sympathetic pathway from the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus to the liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5966–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyama, N.; Geerts, A.; Reynaert, H. Neural connections between the hypothalamus and the liver. Anat. Rec. 2004, 280, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, M.A. The brain-heart connection. Circulation 2007, 116, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohawk, J.A.; Green, C.B.; Takahashi, J.S. Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-D.; Luo, Y.-J.; Chen, Z.-K.; Quintanilla, L.; Cherasse, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lazarus, M.; Huang, Z.-L.; Song, J. Hypothalamic modulation of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice confers activity-dependent regulation of memory and anxiety-like behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 630–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; He, L.; Huang, A.J.Y.; Boehringer, R.; Robert, V.; Wintzer, M.E.; Polygalov, D.; Weitemier, A.Z.; Tao, Y.; Gu, M.; et al. A hypothalamic novelty signal modulates hippocampal memory. Nature 2020, 586, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirtamara Rajamani, K.; Barbier, M.; Lefevre, A.; Niblo, K.; Cordero, N.; Netser, S.; Grinevich, V.; Wagner, S.; Harony-Nicolas, H. Oxytocin activity in the paraventricular and supramammillary nuclei of the hypothalamus is essential for social recognition memory in rats. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 29, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daviu, N.; Bruchas, M.R.; Moghaddam, B.; Sandi, C.; Beyeler, A. Neurobiological links between stress and anxiety. Neurobiol. Stress 2019, 11, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Hu, H.; Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Wang, K.; Li, P.; Yin, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. New insights into the central sympathetic hyperactivity post-myocardial infarction: Roles of METTL3-mediated m6A methylation. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 1264–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, M.; Mittal, A.; Jain, V.R.; Bharadwaj, A.; Modi, S.; Ahuja, G.; Jain, A.; Kumar, K. Integrative Functions of the Hypothalamus: Linking Cognition, Emotion and Physiology for Well-being and Adaptability. Ann. Neurosci. 2024, 32, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiche, E.M.V.; Nunes, S.O.V.; Morimoto, H.K. Stress, depression, the immune system, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2004, 5, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunin, S.M.; Novoselova, E.G.; Glushkova, O.V.; Parfenyuk, S.B.; Novoselova, T.V.; Khrenov, M.O. Cell Senescence and Central Regulators of Immune Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segner, H.; Verburg-van Kemenade, B.M.L.; Chadzinska, M. The immunomodulatory role of the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis: Proximate mechanism for reproduction-immune trade offs? Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 66, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, S.; Wu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wan, C.; Yuan, N.; Chen, J.; Hao, W.; Mo, X.; Guo, X.; et al. Roles of microglia in adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression and their therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1193053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajdarovic, K.H.; Yu, D.; Hassell, L.-A.; Evans, S.; Packer, S.; Neretti, N.; Webb, A.E. Single-cell analysis of the aging female mouse hypothalamus. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 662–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán-Ruíz, M.A.; Guerrero Vargas, N.N.; Ramírez-Carreto, R.J.; González-Orozco, J.C.; Torres-Hernández, B.A.; Valle-Rodríguez, M.; Guevara-Guzmán, R.; Chavarría, A. Microglia in physiological conditions and the importance of understanding their homeostatic functions in the arcuate nucleus. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1392077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginhoux, F.; Greter, M.; Leboeuf, M.; Nandi, S.; See, P.; Gokhan, S.; Mehler, M.F.; Conway, S.J.; Ng, L.G.; Stanley, E.R.; et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science 2010, 330, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajami, B.; Bennett, J.L.; Krieger, C.; Tetzlaff, W.; Rossi, F.M.V. Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat. Neurosci. 2007, 10, 1538–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xiong, S.; Sun, F.; Qin, G.; Hu, G.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Liang, Y.-X.; Wu, T.; et al. Repopulated microglia are solely derived from the proliferation of residual microglia after acute depletion. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Han, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ren, Q.; Ma, J.; Liu, S. Understanding immune microenvironment alterations in the brain to improve the diagnosis and treatment of diverse brain diseases. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzio, L.; Perego, J. CNS Resident Innate Immune Cells: Guardians of CNS Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Qin, C.; Hu, Z.-W.; Zhou, L.-Q.; Yu, H.-H.; Chen, M.; Bosco, D.B.; Wang, W.; Wu, L.-J.; Tian, D.-S. Microglia reprogram metabolic profiles for phenotype and function changes in central nervous system. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 152, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Itriago, A.; Radford, R.A.W.; Aramideh, J.A.; Maurel, C.; Scherer, N.M.; Don, E.K.; Lee, A.; Chung, R.S.; Graeber, M.B.; Morsch, M. Microglia morphophysiological diversity and its implications for the CNS. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 997786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, H.; Yin, J.; Shi, Y.; Tan, J.; Zheng, L.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Xue, M.; Liu, J.; et al. TLR4 participates in sympathetic hyperactivity Post-MI in the PVN by regulating NF-κB pathway and ROS production. Redox Biol. 2019, 24, 101186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, M.; Jung, S.; Priller, J. Microglia Biology: One Century of Evolving Concepts. Cell 2019, 179, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonna, M.; Butovsky, O. Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borst, K.; Dumas, A.A.; Prinz, M. Microglia: Immune and non-immune functions. Immunity 2021, 54, 2194–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrier, M.; Šimončičová, E.; St-Pierre, M.-K.; McKee, C.; Tremblay, M.-È. Psychological Stress as a Risk Factor for Accelerated Cellular Aging and Cognitive Decline: The Involvement of Microglia-Neuron Crosstalk. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 749737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto-Oliveira, M.; Arrifano, G.P.; Lopes-Araújo, A.; Santos-Sacramento, L.; Takeda, P.Y.; Anthony, D.C.; Malva, J.O.; Crespo-Lopez, M.E. What Do Microglia Really Do in Healthy Adult Brain? Cells 2019, 8, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, J.M.; Sinha, S.; Biernaskie, J.; Kurrasch, D.M. A subpopulation of embryonic microglia respond to maternal stress and influence nearby neural progenitors. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 1326–1345.e1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagi, M.; Nakae, Y.; Okano, J.; Fujino, K.; Tanaka, T.; Miyazawa, I.; Ohashi, N.; Nakagawa, T.; Kojima, H. Aberrant bone marrow-derived microglia in the hypothalamus may dysregulate appetite in diabetes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 682, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, N.; Zanesco, A.; Aguiar, C.; Rodrigues-Luiz, G.F.; Silva, D.; Campos, J.; Camara, N.O.S.; Moraes-Vieira, P.; Araujo, E.; Velloso, L.A. CXCR3-expressing myeloid cells recruited to the hypothalamus protect against diet-induced body mass gain and metabolic dysfunction. eLife 2024, 13, RP95044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, E.; Brito, J.; El Alam, S.; Siques, P. Oxidative Stress, Kinase Activity and Inflammatory Implications in Right Ventricular Hypertrophy and Heart Failure under Hypobaric Hypoxia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataka, K.; Asakawa, A.; Nagaishi, K.; Kaimoto, K.; Sawada, A.; Hayakawa, Y.; Tatezawa, R.; Inui, A.; Fujimiya, M. Bone marrow-derived microglia infiltrate into the paraventricular nucl eus of chronic psychological stress-loaded mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, G.S.; Nair, A.R.; Dange, R.B.; Silva-Soares, P.P.; Michelini, L.C.; Francis, J. Toll-like receptor 4 promotes autonomic dysfunction, inflammation and microglia activation in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.D.; Yoon, N.A.; Jin, S.; Diano, S. Microglial UCP2 Mediates Inflammation and Obesity Induced by High-Fat Feeding. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 952–962.e955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaler, J.P.; Yi, C.-X.; Schur, E.A.; Guyenet, S.J.; Hwang, B.H.; Dietrich, M.O.; Zhao, X.; Sarruf, D.A.; Izgur, V.; Maravilla, K.R.; et al. Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cansell, C.; Stobbe, K.; Sanchez, C.; Le Thuc, O.; Mosser, C.-A.; Ben-Fradj, S.; Leredde, J.; Lebeaupin, C.; Debayle, D.; Fleuriot, L.; et al. Dietary fat exacerbates postprandial hypothalamic inflammation involving glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive cells and microglia in male mice. Glia 2020, 69, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Hochstetter, D.; Yao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, P. Green Tea Polyphenol (-)-Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) Attenuates Neuroinflammation in Palmitic Acid-Stimulated BV-2 Microglia and High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Hu, H.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tang, K.; Pan, Z.; Huang, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q.; Gao, Y. Microglia Sirt6 modulates the transcriptional activity of NRF2 to ameliorate high-fat diet-induced obesity. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-J.; Liu, X.-J.; Guo, J.; Su, Y.-K.; Zhang, N.; Qi, J.; Li, Y.; Fu, L.-Y.; Liu, K.-L.; Li, Y.; et al. Blockade of Microglial Activation in Hypothalamic Paraventricular Nucleus Improves High Salt-Induced Hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2022, 35, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kandari, W.; Jambunathan, S.; Navalgund, V.; Koneni, R.; Freer, M.; Parimi, N.; Mudhasani, R.; Fontes, J.D. ZXDC, a novel zinc finger protein that binds CIITA and activates MHC gene transcription. Mol. Immunol. 2007, 44, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiurazzi, M.; Di Maro, M.; Cozzolino, M.; Colantuoni, A. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Microglia as New Targets in Metabolism Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanety, H.; Feinstein, R.; Papa, M.Z.; Hemi, R.; Karasik, A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced phosphorylation of insulin recepto r substrate-1 (IRS-1). Possible mechanism for suppression of insulin-s timulated tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 23780–23784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Yin, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, J.; Jiang, X.; Yuan, L.; Wang, C.-Y.; Li, Z. Blockade of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor type 1-mediated TNF-a lpha signaling protected Wistar rats from diet-induced obesity and ins ulin resistance. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 2943–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbo, V.C.; Engel, D.F.; Jara, C.P.; Mendes, N.F.; Haddad-Tovolli, R.; Prado, T.P.; Sidarta-Oliveira, D.; Morari, J.; Velloso, L.A.; Araujo, E.P. Interleukin-6 actions in the hypothalamus protects against obesity and is involved in the regulation of neurogenesis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 18, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, K.-S.; Jung, H.-Y.; Kim, Y.-K. The role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the neuroinflammation and neurogenesis of schizophrenia. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.-C.; Shi, Z.; Sha, N.-N.; Chen, N.; Peng, S.-Y.; Liao, D.-F.; Wong, M.-S.; Dong, X.-L.; Wang, Y.-J.; Yuan, T.-F.; et al. Paricalcitol alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior by suppressing hypothalamic microglia activation and neuroinflammation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 163, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-H.; Lu, D.-Y.; Yang, R.-S.; Tsai, H.-Y.; Kao, M.-C.; Fu, W.-M.; Chen, Y.-F. Leptin-induced IL-6 production is mediated by leptin receptor, insulin receptor substrate-1, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Akt, NF-kappaB, and p300 pathway in microglia. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 1292–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; Karin, M.; Bai, H.; Cai, D. Hypothalamic IKKbeta/NF-kappaB and ER stress link overnutrition to ene rgy imbalance and obesity. Cell 2008, 135, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolicelli, R.C.; Bolasco, G.; Pagani, F.; Maggi, L.; Scianni, M.; Panzanelli, P.; Giustetto, M.; Ferreira, T.A.; Guiducci, E.; Dumas, L.; et al. Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science 2011, 333, 1456–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, D.P.; Lehrman, E.K.; Kautzman, A.G.; Koyama, R.; Mardinly, A.R.; Yamasaki, R.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Greenberg, M.E.; Barres, B.A.; Stevens, B. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron 2012, 74, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowley, M.A.; Smart, J.L.; Rubinstein, M.; Cerdán, M.G.; Diano, S.; Horvath, T.L.; Cone, R.D.; Low, M.J. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature 2001, 411, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouret, S.G.; Draper, S.J.; Simerly, R.B. Trophic action of leptin on hypothalamic neurons that regulate feeding. Science 2004, 304, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawfik, M.K.; Badran, D.I.; Keshawy, M.M.; Makary, S.; Abdo, M. Alternate-day fat diet and exenatide modulate the brain leptin JAK2/STAT3/SOCS3 pathway in a fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance mouse model. Arch. Med. Sci. 2023, 19, 1508–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, H.; Li, Q.; Yan, C.; Li, Y.; He, S.; Wang, N.; Wang, Q. Impaired lipophagy induced-microglial lipid droplets accumulation contributes to the buildup of TREM1 in diabetes-associated cognitive impairment. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2639–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Li, M.; Rui, L. SH2-B promotes insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1)- and IRS2-mediated activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway in response to leptin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 43684–43691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, E.; Nenic, K.; Milanovic, V.; Knezevic, N.N. The Role of Cortisol in Chronic Stress, Neurodegenerative Diseases, and Psychological Disorders. Cells 2023, 12, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.-C.; Xia, S.-H.; Pan, H.; Zhou, T.-T.; Wang, X.-L.; Li, J.-M.; Li, X.-M.; Zhang, Y. Chaihu-Shugan-San Ameliorated Osteoporosis of Mice with Depressive Behavior Caused by Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress via Repressing Neuroinflammation and HPA Activity. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 5997–6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soch, A.; Bradburn, S.; Sominsky, L.; De Luca, S.N.; Murgatroyd, C.; Spencer, S.J. Effects of exercise on adolescent and adult hypothalamic and hippocampal neuroinflammation. Hippocampus 2016, 26, 1435–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, L.M.; Weiner, H.L. Microbiota Signaling Pathways that Influence Neurologic Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efentakis, P.; Molitor, M.; Kossmann, S.; Bochenek, M.L.; Wild, J.; Lagrange, J.; Finger, S.; Jung, R.; Karbach, S.; Schäfer, K.; et al. Tubulin-folding cofactor E deficiency promotes vascular dysfunction by increased endoplasmic reticulum stress. Eur. Hear. J. 2021, 43, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sanderson, D.; Mian, M.F.; McVey Neufeld, K.-A.; Forsythe, P. Loss of vagal integrity disrupts immune components of the microbiota-gut-brain axis and inhibits the effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus on behavior and the corticosterone stress response. Neuropharmacology 2021, 195, 108682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, W.-D.; Wang, Y.-D. The Relationship Between Gut Microbiota and Inflammatory Diseases: The Role of Macrophages. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, N.; Fernández-Rilo, A.C.; Palomba, L.; Di Marzo, V.; Cristino, L. Obesity Affects the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis and the Regulation Thereof by Endocannabinoids and Related Mediators. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarale, P.; Chaudhary, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Sarkar, D.K. Ethanol-activated microglial exosomes induce MCP1 signaling mediated death of stress-regulatory proopiomelanocortin neurons in the developing hypothalamus. J. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 21, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orio, L.; Llopis, N.; Torres, E.; Izco, M.; O’Shea, E.; Colado, M.I. A study on the mechanisms by which minocycline protects against MDMA (‘ecstasy’)-induced neurotoxicity of 5-HT cortical neurons. Neurotox. Res. 2009, 18, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Huang, S.; Li, M.Y.; Luo, Q.H.; Chen, F.M.; Hong, C.L.; Yan, H.H.; Qiu, J.; Zhao, K.L.; Du, Y.; et al. Dihydromyricetin regulates the miR-155-5p/SIRT1/VDAC1 pathway to promote liver regeneration and improve alcohol-induced liver injury. Phytomedicine 2025, 139, 156522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Cheng, G.; Bi, Q.; Lu, C.; Sun, Q.; Li, L.; Chen, N.; Hu, M.; Lu, H.; Xu, X.; et al. Microglia in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus sense hemodynamic disturbance and promote sympathetic excitation in hypertension. Immunity 2024, 57, 2030–2042.e2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R.K.; Tanti, A.; Ainouche, S.; Roger, S.; Belzung, C.; Camus, V. A P2X7 receptor antagonist reverses behavioural alterations, microglial activation and neuroendocrine dysregulation in an unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS) model of depression in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 97, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, A.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Li, M.; Qi, Y.; Yin, Q.; Luo, W.; Shi, J.; Cong, Q. Molecular mechanisms underlying microglial sensing and phagocytosis in synaptic pruning. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 19, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfau, S.J.; Langen, U.H.; Fisher, T.M.; Prakash, I.; Nagpurwala, F.; Lozoya, R.A.; Lee, W.-C.A.; Wu, Z.; Gu, C. Characteristics of blood–brain barrier heterogeneity between brain regions revealed by profiling vascular and perivascular cells. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 1892–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofer, H. Zur Morphologie der circumventrikulären Organe des Zwischenhirns der Säugetiere. Verh. Dtsch. Zool. Ges. 1958, 22, 202–261. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Ruiz, R.; Cárdenas-Tueme, M.; Montalvo-Martínez, L.; Vidaltamayo, R.; Garza-Ocañas, L.; Reséndez-Perez, D.; Camacho, A. Priming of Hypothalamic Ghrelin Signaling and Microglia Activation Exacerbate Feeding in Rats’ Offspring Following Maternal Overnutrition. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglass, J.D.; Ness, K.M.; Valdearcos, M.; Wyse-Jackson, A.; Dorfman, M.D.; Frey, J.M.; Fasnacht, R.D.; Santiago, O.D.; Niraula, A.; Banerjee, J.; et al. Obesity-associated microglial inflammatory activation paradoxically improves glucose tolerance. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 1613–1629.e1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; McIlwraith, E.K.; Chalmers, J.A.; Belsham, D.D. Palmitate Induces an Anti-Inflammatory Response in Immortalized Microglial BV-2 and IMG Cell Lines that Decreases TNFα Levels in mHypoE-46 Hypothalamic Neurons in Co-Culture. Neuroendocrinology 2018, 107, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbo, V.C.D.; Jara, C.P.; Mendes, N.F.; Morari, J.; Velloso, L.A.; Araújo, E.P. Interleukin-6 Expression by Hypothalamic Microglia in Multiple Inflammatory Contexts: A Systematic Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1365210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrold, J.A.; Cai, X.; Williams, G. Leptin, the hypothalamus and the regulation of adiposity. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 1998, 9, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grao-Cruces, E.; Millan-Linares, M.C.; Martin-Rubio, M.E.; Toscano, R.; Barrientos-Trigo, S.; Bermudez, B.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S. Obesity-Associated Metabolic Disturbances Reverse the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of High-Density Lipoproteins in Microglial Cells. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarians-Armavil, A.; Menchella, J.A.; Belsham, D.D. Cellular insulin resistance disrupts leptin-mediated control of neuron al signaling and transcription. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 27, 990–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.-T.; Estrada, C.; Maatouk, L.; Vyas, S. Inflammation in Parkinson’s disease: Role of glucocorticoids. Front. Neuroanat. 2015, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Bai, M.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Gao, M.; Liu, B.; Shi, G. Balancing Anti-Inflammation and Neurorepair: The Role of Mineralocorticoid Receptor in Regulating Microglial Phenotype Switching After Traumatic Brain Injury. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2025, 31, e70404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, X.; Yang, L.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, L. Comprehensive Analysis of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Intracranial Aneurysm. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 865005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, G.; Sampson, T.R.; Geschwind, D.H.; Mazmanian, S.K. The Central Nervous System and the Gut Microbiome. Cell 2016, 167, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdearcos, M.; McGrath, E.R.; Brown Mayfield, S.M.; Jacuinde, M.G.; Folick, A.; Cheang, R.T.; Li, R.; Bachor, T.P.; Lippert, R.N.; Xu, A.W.; et al. Microglia mediate the early-life programming of adult glucose control. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdearcos, M.; Robblee, M.M.; Benjamin, D.I.; Nomura, D.K.; Xu, A.W.; Koliwad, S.K. Microglia dictate the impact of saturated fat consumption on hypothala mic inflammation and neuronal function. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 2124–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, E.J.; Biltz, R.G.; Packer, J.M.; DiSabato, D.J.; Swanson, S.P.; Oliver, B.; Quan, N.; Sheridan, J.F.; Godbout, J.P. Enhanced fear memory after social defeat in mice is dependent on interleukin-1 receptor signaling in glutamatergic neurons. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 2321–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.-Y.; Gao, G.-Y.; Feng, J.-F.; Mao, Q.; Chen, L.-G.; Yang, X.-F.; Liu, J.-F.; Wang, Y.-H.; Qiu, B.-H.; Huang, X.-J. Traumatic brain injury in China. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, S.J.; Trimigliozzi, K.; Dror, E.; Meier, D.T.; Molina-Tijeras, J.A.; Rachid, L.; Le Foll, C.; Magnan, C.; Schulze, F.; Stawiski, M.; et al. The cephalic phase of insulin release is modulated by IL-1β. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 991–1003.e1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horii-Hayashi, N.; Sasagawa, T.; Nishi, M. Insights from extracellular matrix studies in the hypothalamus: Structural variations of perineuronal nets and discovering a new perifornical area of the anterior hypothalamus. Anat. Sci. Int. 2016, 92, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzadeh, Z.; Alonge, K.M.; Cabrales, E.; Herranz-Pérez, V.; Scarlett, J.M.; Brown, J.M.; Hassouna, R.; Matsen, M.E.; Nguyen, H.T.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; et al. Perineuronal Net Formation during the Critical Period for Neuronal Maturation in the Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niraula, A.; Fasnacht, R.D.; Ness, K.M.; Frey, J.M.; Cuschieri, S.A.; Dorfman, M.D.; Thaler, J.P. Prostaglandin PGE2 Receptor EP4 Regulates Microglial Phagocytosis and Increases Susceptibility to Diet-Induced Obesity. Diabetes 2023, 72, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, K.M.; Nugent, B.M.; Haliyur, R.; McCarthy, M.M. Microglia are essential to masculinization of brain and behavior. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 2761–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Peng, B. Microglia bridge brain activity and blood pressure. Immunity 2024, 57, 2000–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, B.; Luo, M.; Xie, L.; Lu, M.; Lu, X.; Zhang, S.; Wei, L.; Zhou, X.; Yao, B.; et al. Microbiota-indole 3-propionic acid-brain axis mediates abnormal synaptic pruning of hippocampal microglia and susceptibility to ASD in IUGR offspring. Microbiome 2023, 11, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, D.Q.; Tse, E.K.; Kim, M.H.; Belsham, D.D. Diet-induced cellular neuroinflammation in the hypothalamus: Mechanistic insights from investigation of neurons and microglia. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2016, 438, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folick, A.; Cheang, R.T.; Valdearcos, M.; Koliwad, S.K. Metabolic factors in the regulation of hypothalamic innate immune responses in obesity. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellner, A.-K.; Sitter, A.; Rackiewicz, M.; Sylvester, M.; Philipsen, A.; Zimmer, A.; Stein, V. Stress vulnerability shapes disruption of motor cortical neuroplasticity. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, J.; Salinas, S.; Huang, H.-Y.; Zhou, M. Microglia regulation of synaptic plasticity and learning and memory. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Arboledas, A.; Acharya, M.M.; Tenner, A.J. The Role of Complement in Synaptic Pruning and Neurodegeneration. Immunotargets Ther. 2021, 10, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B.; Sinniger, V.; Pellissier, S. Vagus nerve stimulation: A new promising therapeutic tool in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 282, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakan, T.; Ozkul, C.; Küpeli Akkol, E.; Bilici, S.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Capasso, R. Gut-Brain-Microbiota Axis: Antibiotics and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Nutrients 2021, 13, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwish, R.; Alcibahy, Y.; Bucheeri, S.; Albishtawi, A.; Tama, M.; Shetty, J.; Butler, A.E. The Role of Hypothalamic Microglia in the Onset of Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes: A Neuro-Immune Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papazoglou, I.; Lee, J.-H.; Cui, Z.; Li, C.; Fulgenzi, G.; Bahn, Y.J.; Staniszewska-Goraczniak, H.M.; Piñol, R.A.; Hogue, I.B.; Enquist, L.W.; et al. A distinct hypothalamus-to-β cell circuit modulates insulin secretion. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 285–298.e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, J.; Fujita, Y.; Shinno-Hashimoto, H.; Shan, J.; Wan, X.; Qu, Y.; Chang, L.; Wang, X.; Hashimoto, K. Effects of spleen nerve denervation on depression–like phenotype, systemic inflammation, and abnormal composition of gut microbiota in mice after administration of lipopolysaccharide: A role of brain–spleen axis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 317, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Q.; Wang, C.; Cheng, G.; Chen, N.; Wei, B.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Lu, C.; He, J.; Weng, Y.; et al. Microglia-derived PDGFB promotes neuronal potassium currents to suppress basal sympathetic tonicity and limit hypertension. Immunity 2022, 55, 1466–1482.e1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Qian, X.; Ren, X.; Zhang, S.; Hu, L.; Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Huang, R.; Ooi, K.; Lin, H.; et al. Inhibition of cGAS in Paraventricular Nucleus Attenuates Hypertensive Heart Injury Via Regulating Microglial Autophagy. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 7006–7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y. The Regulatory Effect of the Paraventricular Nucleus on Hypertension. Neuroendocrinology 2023, 114, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Wang, Y.; Ge, W.; Jing, Y.; Hu, H.; Yin, J.; Xue, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, X.; et al. m6A methyltransferase METTL3 contributes to sympathetic hyperactivity post-MI via promoting TRAF6-dependent mitochondrial ROS production. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 209, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, Z.; Kuti, D.; Polyák, Á.; Juhász, B.; Gulyás, K.; Lénárt, N.; Dénes, Á.; Ferenczi, S.; Kovács, K.J. Hypoglycemia-activated Hypothalamic Microglia Impairs Glucose Counterregulatory Responses. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, C.F. Regulation of metabolic homeostasis by the TGF-β superfamily receptor ALK7. FEBS J. 2021, 289, 5776–5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Dong, L.; Jing, X.; Gen-Yang, C.; Zhan-Zheng, Z. Abnormal lncRNA CCAT1/microRNA-155/SIRT1 axis promoted inflammatory response and apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells in LPS caused acute kidney injury. Mitochondrion 2020, 53, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, M.G.; Palladini, M.; De Lorenzo, R.; Magnaghi, C.; Poletti, S.; Furlan, R.; Ciceri, F.; The COVID-19 BioB Outpatient Clinic Study Group; Rovere-Querini, P.; Benedetti, F. Persistent psychopathology and neurocognitive impairment in COVID-19 survivors: Effect of inflammatory biomarkers at three-month follow-up. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2021, 94, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasserie, T.; Hittle, M.; Goodman, S.N. Assessment of the Frequency and Variety of Persistent Symptoms Among Patients With COVID-19: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2111417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.; Nagele, F.L.; Mayer, C.; Schell, M.; Petersen, E.; Kuhn, S.; Gallinat, J.; Fiehler, J.; Pasternak, O.; Matschke, J.; et al. Brain imaging and neuropsychological assessment of individuals recovered from a mild to moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2217232120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes, P.; Yin, H.Y.; Tang, Y. Focal neuropathologies in the brain of COVID-19-infected humans: Inflammation, primary gliovascular failure and microglial dysfunction. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworsky-Fried, Z.; Kerr, B.J.; Taylor, A.M.W. Microbes, microglia, and pain. Neurobiol. Pain 2020, 7, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.-R.; Nackley, A.; Huh, Y.; Terrando, N.; Maixner, W. Neuroinflammation and Central Sensitization in Chronic and Widespread Pain. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Pan, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wan, J.; Jiang, H. Microglia-Mediated Neuroinflammation: A Potential Target for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 3083–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, X.; Hou, X.; Zhu, K.; Chen, W.; Chen, K.; Sang, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps facilitate sympathetic hyperactivity by polarizing microglia toward M1 phenotype after traumatic brain injury. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e23112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae, C.D.; Baur, J.A.; Borges, K.; Dienel, G.; Díaz-García, C.M.; Douglass, S.R.; Drew, K.; Duarte, J.M.N.; Duran, J.; Kann, O.; et al. Brain energy metabolism: A roadmap for future research. J. Neurochem. 2024, 168, 910–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurcovicova, J. Glucose transport in brain—Effect of inflammation. Endocr. Regul. 2014, 48, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, N.; Chin, S.A.; Riddell, M.C.; Beaudry, J.L. Genomic and Non-Genomic Actions of Glucocorticoids on Adipose Tissue Lipid Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.; Chen, T.-C.; Lee, R.A.; Nguyen, N.H.T.; Broughton, A.E.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.-C. Pik3r1 Is Required for Glucocorticoid-Induced Perilipin 1 Phosphorylation in Lipid Droplet for Adipocyte Lipolysis. Diabetes 2017, 66, 1601–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, B.E.; Lutz, T.A. Amylin and Leptin: Co-Regulators of Energy Homeostasis and Neuronal Development. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 28, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brites, D.; Fernandes, A. Neuroinflammation and Depression: Microglia Activation, Extracellular Microvesicles and microRNA Dysregulation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Pearse, D.D. The Yin and Yang of Microglia-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in CNS Injury and Diseases. Cells 2024, 13, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brites, D. Regulatory function of microRNAs in microglia. Glia 2020, 68, 1631–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Liu, J.; Xue, Y.; Fu, T.; Li, Z. Sympathetic Nerves Coordinate Corneal Epithelial Wound Healing by Controlling the Mobilization of Ly6Chi Monocytes From the Spleen to the Injured Cornea. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Beja-Glasser, V.F.; Nfonoyim, B.M.; Frouin, A.; Li, S.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Merry, K.M.; Shi, Q.; Rosenthal, A.; Barres, B.A.; et al. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science 2016, 352, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Key Mechanisms | Signaling Pathways | Disease Associations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diet-induced Neuroinflammation | TLR4, NF-κB, NLRP3 | Metabolic dysregulation, obesity, diabetes | [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64] |

| Activation of Microglia and Cytokine Release | IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 | Leptin resistance, increased appetite | [56,65,66,67,68,69] |

| Synaptic Remodeling and Pruning | IKKβ/NF-κB, JAK2/STAT3 | Energy balance disruption, neuropsychiatric disorders | [64,70,71,72,73] |

| Leptin Regulation of Microglia | LepRb/JAK2/STAT3, PI3K/Akt | Leptin-related neuroinflammation, metabolic syndrome | [70,74,75,76,77,78] |

| Glucocorticoid Regulation of Microglia | GR/NF-κB, NLRP3 | Chronic stress, anxiety disorders | [68,69,79,80,81] |

| Gut Microbiota Influence on Microglia | GPR43/41, CD14/TLR4 | Metabolic diseases, neurodegenerative diseases | [82,83,84,85,86] |

| Anti-inflammatory Effects of Short-chain Fatty Acids | NF-κB, HDAC | Obesity, gut dysbiosis | [83,84] |

| Alcohol and Neurotoxin Activation of Microglia | TLR4/2, NADPH oxidase-ROS-NF-κB | Alcohol-related diseases, neurotoxic damage | [87,88,89] |

| Role of ATP in Microglial Activation | P2X7/P2Y12, NLRP3 | Neuroinflammation, synaptic plasticity impairment | [90,91,92] |

| Key Mechanisms | Signaling Pathways | Disease Associations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactivity Shift in Microglia | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, ROS | Neuroinflammation, metabolic dysregulation | [56,107,108] |

| Effects of TNF-α on Hypothalamic Neurons | Caspase-3, NF-κB, AMPA receptors | HPA axis dysfunction, appetite regulation disruption | [36,65,68] |

| Effects of IL-1β on Neurons | NMDA receptors, Ca2+ channels | Thermoregulation disorders, learning and memory impairments | [108,109,110] |

| Inhibitory Effects of IL-6 on Hypothalamic Neurons | POMC neurons, AgRP neurons | Metabolic syndrome, appetite disorders | [67,98] |

| Activity-dependent Synaptic Pruning | TNF-α, IL-1β, ATP/P2Y12 | Neural circuit remodeling, metabolic balance disruption | [72,73,92] |

| Extracellular Matrix Remodeling and Microglial Phagocytosis | PNNs, phagocytic mechanisms | Neural plasticity, metabolic regulation disorders | [111,112,113] |

| Dietary Lipid Overload Effects on Microglia | PGE2, EP4 receptors | HFD-induced metabolic dysfunction | [113] |

| Sexual Dimorphism in Microglial Functions | Microglial phagocytosis | Sexual differences, neurodevelopmental disorders | [114] |

| Key Mechanisms | Signaling Pathways | Disease Associations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vagal Nerve-mediated Parasympathetic Regulation | IL-1β, neural transmission pathways | Gastrointestinal dysfunction, metabolic syndrome | [110,122,123] |

| Microglial Regulation of Insulin Secretion | IL-1β, vagal nerve activation | Diabetes, obesity | [110,124,125] |

| Chronic Microglial Activation and Gastrointestinal Motility | Pro-inflammatory cytokines | Functional dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome | [123,126] |

| Sympathetic Activation and Microglial Function | P2Y12 receptors, C/EBPβ | Hypertension, cardiovascular diseases | [90,127,128] |

| Microglial Role in Hypertension | ATP leakage, C/EBPβ-dependent pro-inflammatory factors | Cardiovascular dysfunction | [90,127,128,129] |

| Microglial Mediated Mechanisms Post-Myocardial Infarction | METTL3, TRAF6/ECSIT signaling pathways | Arrhythmias | [30,130] |

| HPA Axis in Metabolic Homeostasis Regulation | CRH, TNF-α, IL-1β | Stress response, metabolic dysregulation | [36,80,131] |

| Microglial Neural Control of Pancreatic β Cells | AgRP neurons, TGF-β | Type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance | [124,125,132] |

| Exosomal Signaling and Immune–Metabolic Crosstalk | miR-155, MCP1/CCR2 | Multi-organ injury, alcohol-related diseases | [87,89,133] |

| Long COVID and Microglial Dysfunction | Downregulation of P2Y12 receptors, neuro-vascular-neuron damage | Brain fog, fatigue, autonomic dysfunction | [134,135,136,137,138] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Kang, H.; Yu, C.; Xia, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H. Hypothalamic Microglia as Dual Hubs Orchestrating Local and Systemic Homeostasis in the Periphery–Central–Periphery Axis. Cells 2025, 14, 1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221780

Liu Y, Jiang Q, Huang Y, Zhang X, Kang H, Yu C, Xia Y, Liu Y, Zhang H. Hypothalamic Microglia as Dual Hubs Orchestrating Local and Systemic Homeostasis in the Periphery–Central–Periphery Axis. Cells. 2025; 14(22):1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221780

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yuan, Qian Jiang, Yimin Huang, Xincheng Zhang, Huayu Kang, Chenxuan Yu, Yuze Xia, Yanchao Liu, and Huaqiu Zhang. 2025. "Hypothalamic Microglia as Dual Hubs Orchestrating Local and Systemic Homeostasis in the Periphery–Central–Periphery Axis" Cells 14, no. 22: 1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221780

APA StyleLiu, Y., Jiang, Q., Huang, Y., Zhang, X., Kang, H., Yu, C., Xia, Y., Liu, Y., & Zhang, H. (2025). Hypothalamic Microglia as Dual Hubs Orchestrating Local and Systemic Homeostasis in the Periphery–Central–Periphery Axis. Cells, 14(22), 1780. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221780