The BUD31 Homologous Gene in Schizosaccharomyces pombe Is Evolutionarily Conserved and Can Be Linked to Cellular Processes Regulated by the TOR Pathway

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains

2.2. Media

2.3. Preparation of cwf14Δ::kanMX6 CEN1b GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) Labeled Strains

2.4. Study of Sporulation and Meiotic Chromosome Segregation

2.5. PCR Test to Prove Disruption of the cwf14 Gene

2.6. PCR Amplification of the BUD31 Genes

2.7. Cloning of the BUD31 Orthologous Genes

2.8. Transformation of the Yeast Cells

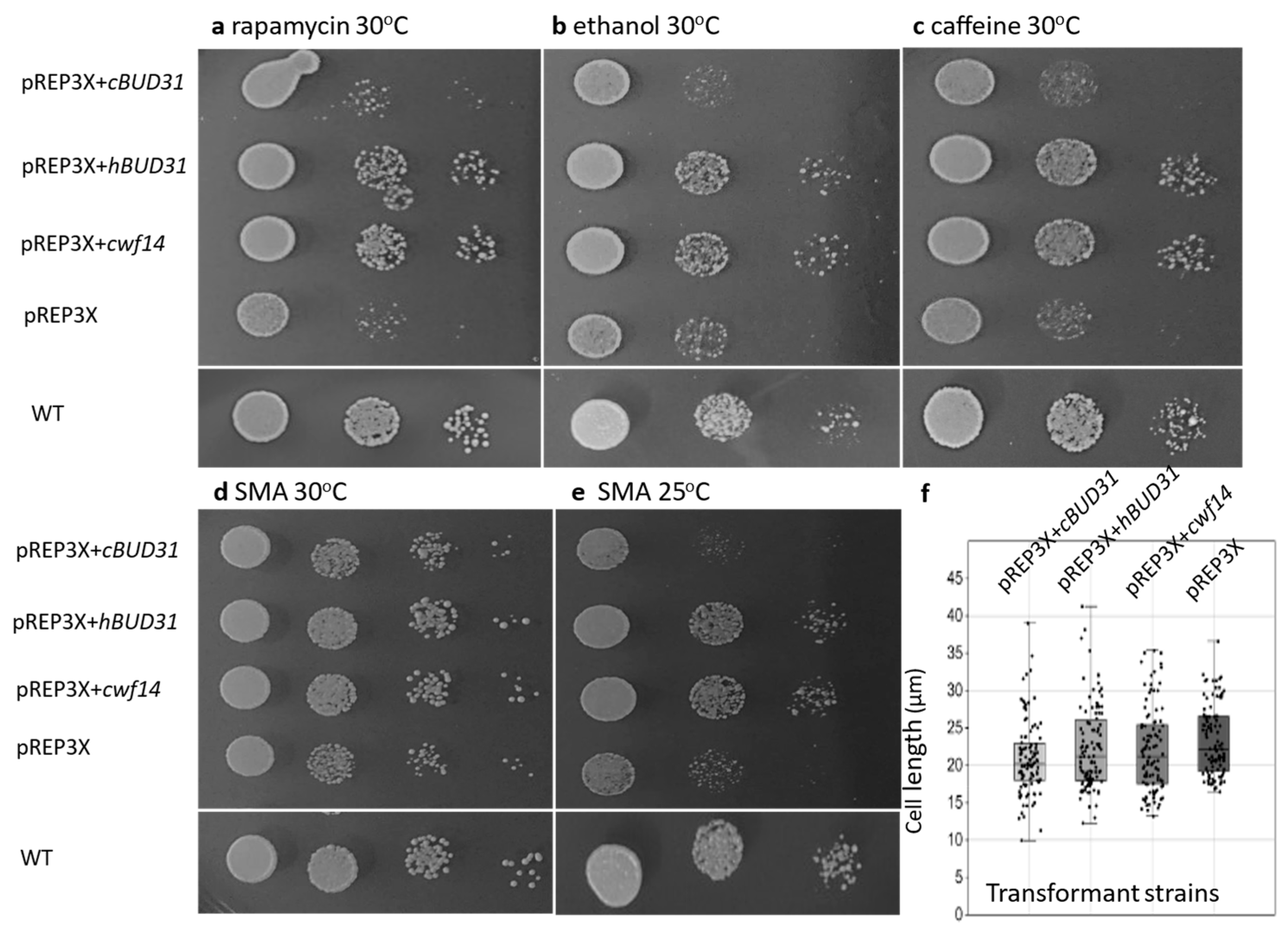

2.9. Stress Response Test

2.10. Investigation of Cell Morphology

2.11. Cell Length

2.12. Long-Term Survival Assay

2.13. Growth in Complex Media

2.14. Bioinformatics Analyses

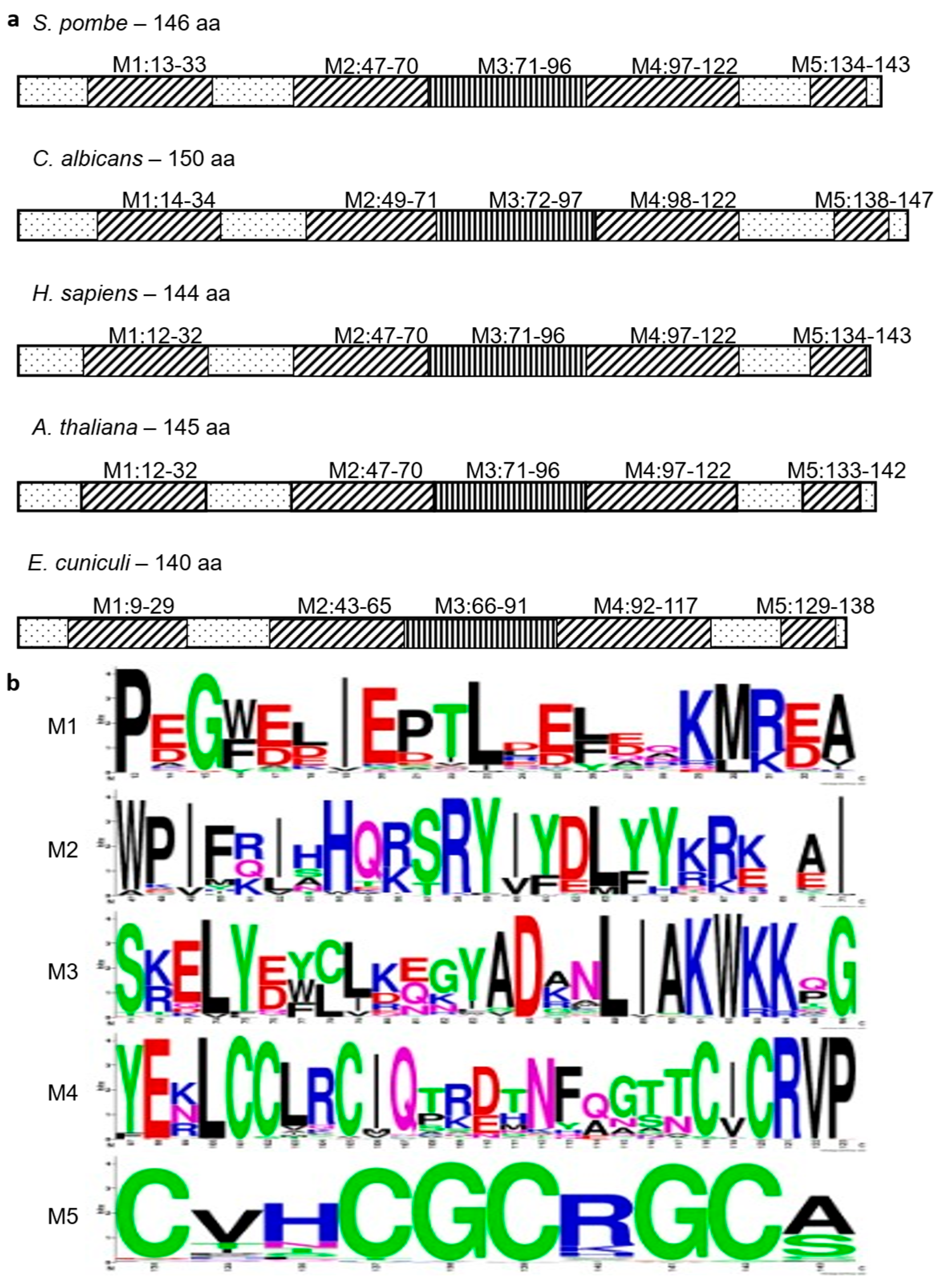

2.14.1. Sequence Retrieval and Motif Analyses

2.14.2. Orthology Inference and Comparative Sequence Analyses

2.14.3. Protein Structure Analyses

2.14.4. Phylogenetic Tree Construction

2.14.5. GO Enrichment

2.14.6. Presence of Introns in Genes Affected by cwf14 Mutation

2.14.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

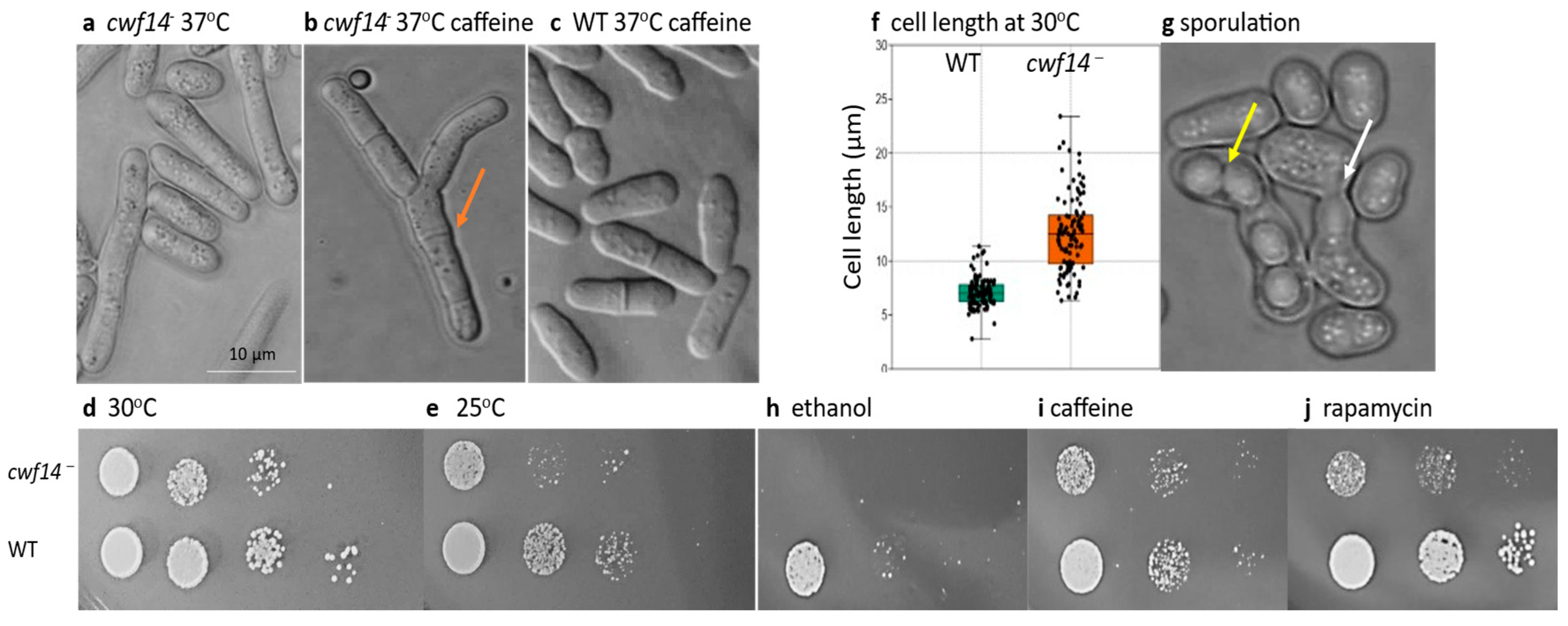

3.1. Disruption of cwf14 Gene Caused a Pleiotropic Phenotype

3.2. The Protein-Coding Genes Affected by cwf14 Mutation Are Often Involved in Transport Processes, Encode Enzymes, and Rarely Contain Introns

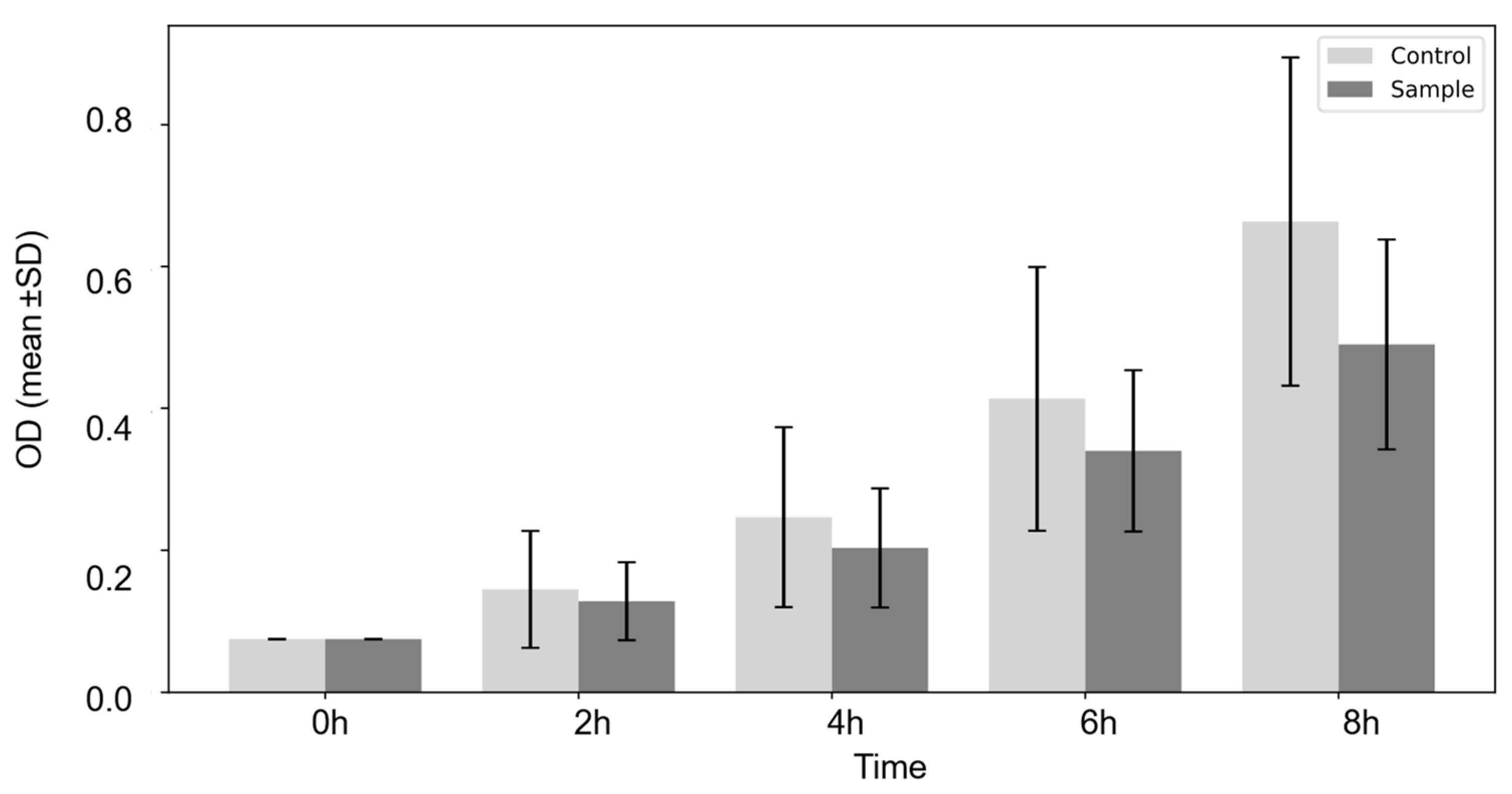

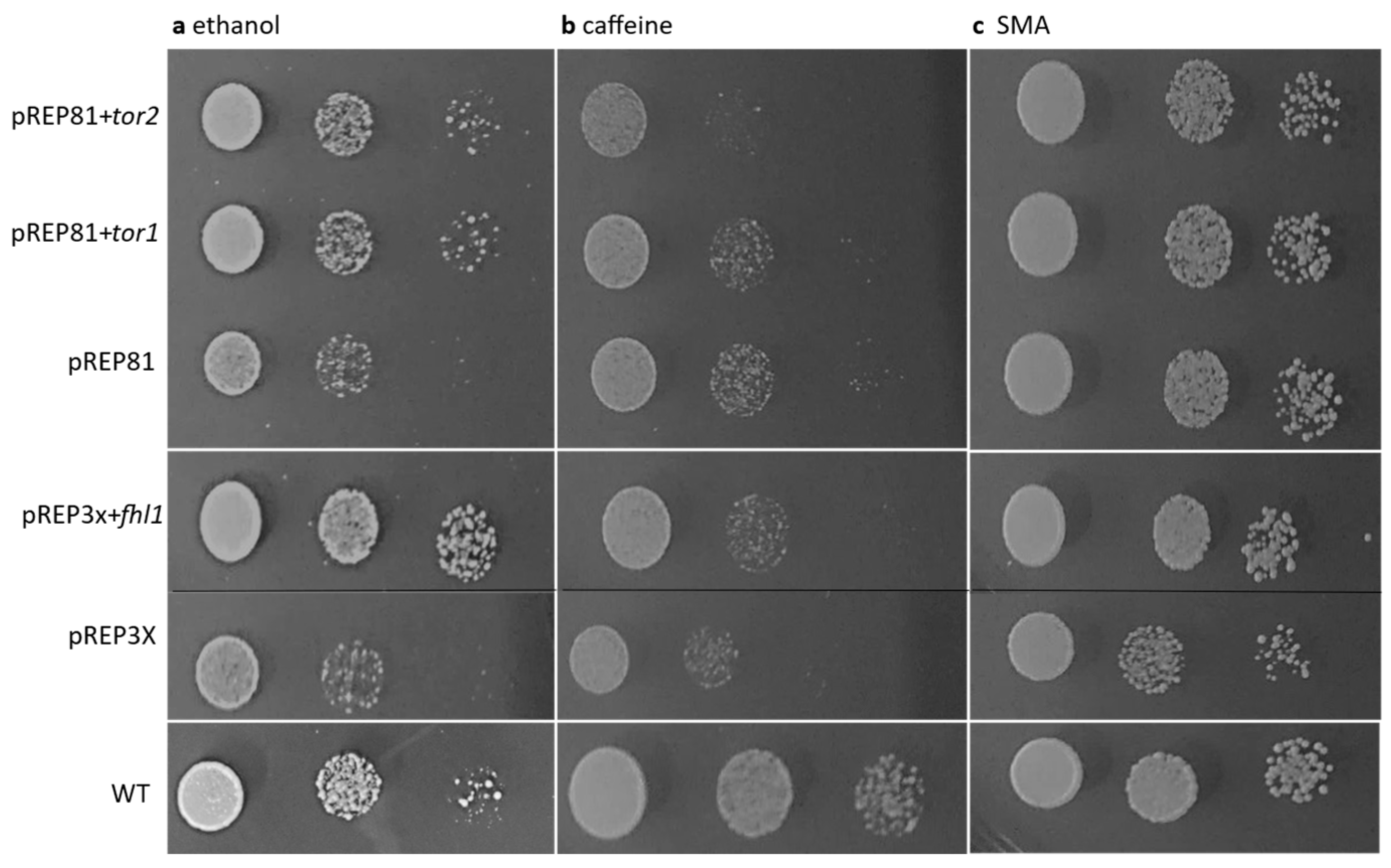

3.3. The cwf14 Gene May Be Linked to TOR Pathway-Regulated Processes

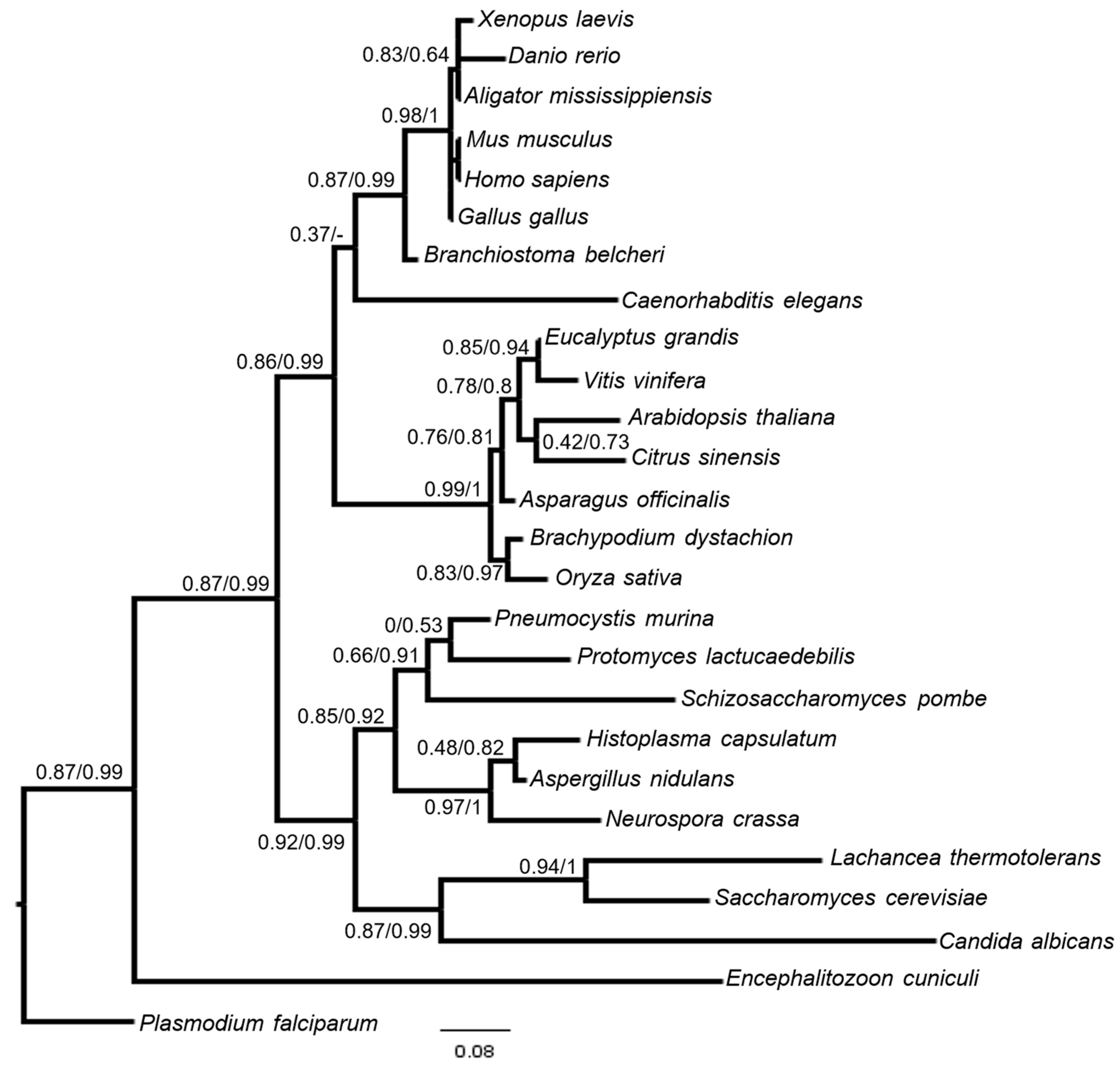

3.4. BUD31 Homologous Genes Are Found in Various Species, Are Evolutionarily Conserved, and Preserve Functional Homology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hsu, C.-L.; Liu, J.-S.; Wu, P.-L.; Guan, H.-H.; Chen, Y.-L.; Lin, A.-C.; Ting, H.-J.; Pang, S.-T.; Yeh, S.-D.; Ma, W.-L.; et al. Identification of a New Androgen Receptor (AR) Co-regulator BUD31 and Related Peptides to Suppress Wild-type and Mutated AR-mediated Prostate Cancer Growth via Peptide Screening and X-ray Structure Analysis. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 8, 1575–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, T.Y.-T.; Simon, L.M.; Neill, N.J.; Marcotte, R.; Sayad, A.; Bland, C.S.; Echeverria, G.V.; Sun, T.; Kurley, S.J.; Tyagi, S.; et al. The Spliceosome Is a Therapeutic Vulnerability in MYC-Driven Cancer. Nature 2015, 525, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, S.; Tolstova, T.; Kurbatov, L.; Farafonova, T.; Tikhonova, O.; Soloveva, N.; Rusanov, A.; Archakov, A.; Zgoda, V. Nuclear Proteomics of Induced Leukemia Cell Differentiation. Cells 2022, 11, 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Qin, J.; Zhang, X.; Lu, G.; Liu, H.; Guo, H.; Wu, L.; Shender, V.O.; Shao, C.; et al. Splicing Factor BUD31 Promotes Ovarian Cancer Progression through Sustaining the Expression of Anti-Apoptotic BCL2L12. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, M.; Gamallat, Y.; Khosh Kish, E.; Seyedi, S.; Gotto, G.; Ghosh, S.; Bismar, T.A. Downregulation of BUD31 Promotes Prostate Cancer Cell Proliferation and Migration via Activation of P-AKT and Vimentin In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Fan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, C.; Yao, X.; Liu, K.; Lin, D.; Chen, Z. The Role of BUD31 in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: Prognostic Significance, Alternative Splicing, and Tumor Immune Environment. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Huang, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Dang, Q.; Cui, D.; Wang, X.; Zhai, Y.; Zhao, L.; et al. Bud31-Mediated Alternative Splicing Is Required for Spermatogonial Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Snyder, M. A Genomic Study of the Bipolar Bud Site Selection Pattern in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. MBoC 2001, 12, 2147–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masciadri, B.; Areces, L.B.; Carpinelli, P.; Foiani, M.; Draetta, G.F.; Fiore, F. Characterization of the BUD31 Gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 320, 1342–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoose, S.A.; Rawlings, J.A.; Kelly, M.M.; Leitch, M.C.; Ababneh, Q.O.; Robles, J.P.; Taylor, D.; Hoover, E.M.; Hailu, B.; McEnery, K.A.; et al. A Systematic Analysis of Cell Cycle Regulators in Yeast Reveals That Most Factors Act Independently of Cell Size to Control Initiation of Division. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auesukaree, C.; Damnernsawad, A.; Kruatrachue, M.; Pokethitiyook, P.; Boonchird, C.; Kaneko, Y.; Harashima, S. Genome-Wide Identification of Genes Involved in Tolerance to Various Environmental Stresses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Appl. Genet. 2009, 50, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.; Muend, S.; Zhang, Y.; Rao, R. A Phenomics Approach in Yeast Links Proton and Calcium Pump Function in the Golgi. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 1480–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burston, H.E.; Maldonado-Báez, L.; Davey, M.; Montpetit, B.; Schluter, C.; Wendland, B.; Conibear, E. Regulators of Yeast Endocytosis Identified by Systematic Quantitative Analysis. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 185, 1097–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaillot, J.; Cook, M.A.; Corbeil, J.; Sellam, A. Genome-Wide Screen for Haploinsufficient Cell Size Genes in the Opportunistic Yeast Candida albicans. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2017, 7, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayles, J.; Wood, V.; Jeffery, L.; Hoe, K.-L.; Kim, D.-U.; Park, H.-O.; Salas-Pino, S.; Heichinger, C.; Nurse, P. A Genome-Wide Resource of Cell Cycle and Cell Shape Genes of Fission Yeast. Open Biol. 2013, 3, 130053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-U.; Maeng, S.; Lee, H.; Nam, M.; Lee, S.-J.; Hoe, K.-L. The Effect of the Cwf14 Gene of Fission Yeast on Cell Wall Integrity Is Associated with Rho1. J. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallgren, S.P.; Andrews, S.; Tadeo, X.; Hou, H.; Moresco, J.J.; Tu, P.G.; Yates, J.R.; Nagy, P.L.; Jia, S. The Proper Splicing of RNAi Factors Is Critical for Pericentric Heterochromatin Assembly in Fission Yeast. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, E.H.; Bijos, D.A.; White, S.A.; Alves, F.D.L.; Rappsilber, J.; Allshire, R.C. A Systematic Genetic Screen Identifies New Factors Influencing Centromeric Heterochromatin Integrity in Fission Yeast. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, M.C.; Will, C.L.; Lührmann, R. The Spliceosome: Design Principles of a Dynamic RNP Machine. Cell 2009, 136, 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, C.L.; Luhrmann, R. Spliceosome Structure and Function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a003707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohi, M.D.; Link, A.J.; Ren, L.; Jennings, J.L.; McDonald, W.H.; Gould, K.L. Proteomics Analysis Reveals Stable Multiprotein Complexes in Both Fission and Budding Yeasts Containing Myb-Related Cdc5p/Cef1p, Novel Pre-mRNA Splicing Factors, and snRNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 2011–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; McLean, J.R.; Hazbun, T.R.; Fields, S.; Vander Kooi, C.; Ohi, M.D.; Gould, K.L. Systematic Two-Hybrid and Comparative Proteomic Analyses Reveal Novel Yeast Pre-mRNA Splicing Factors Connected to Prp19. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipakova, I.; Jurcik, M.; Rubintova, V.; Borbova, M.; Mikolaskova, B.; Jurcik, J.; Bellova, J.; Barath, P.; Gregan, J.; Cipak, L. Identification of Proteins Associated with Splicing Factors Ntr1, Ntr2, Brr2 and Gpl1 in the Fission Yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 1532–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, D.; Khandelia, P.; O’Keefe, R.T.; Vijayraghavan, U. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae NineTeen Complex (NTC)-Associated Factor Bud31/Ycr063w Assembles on Precatalytic Spliceosomes and Improves First and Second Step Pre-mRNA Splicing Efficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 5390–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antosz, W.; Pfab, A.; Ehrnsberger, H.F.; Holzinger, P.; Köllen, K.; Mortensen, S.A.; Bruckmann, A.; Schubert, T.; Längst, G.; Griesenbeck, J.; et al. The Composition of the Arabidopsis RNA Polymerase II Transcript Elongation Complex Reveals the Interplay between Elongation and mRNA Processing Factors. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 854–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs-Szabo, L.; Papp, L.A.; Miklos, I. Understanding the Molecular Mechanisms of Human Diseases: The Benefits of Fission Yeasts. Microb. Cell 2024, 11, 288–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grallert, A.; Miklos, I.; Sipiczki, M. Division-Site Selection, Cell Separation, and Formation of Anucleate Minicells in Schizosaccharomyces pombe Mutants Resistant to Cell-Wall Lytic Enzymes. Protoplasma 1997, 198, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grallert, A.; Grallert, B.; Zilahi, E.; Szilagyi, Z.; Sipiczki, M. Eleven Novel sep Genes of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Required for Efficient Cell Separation and Sexual Differentiation. Yeast 1999, 15, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklos, I.; Ludanyi, K.; Sipiczki, M. The Pleiotropic Cell Separation Mutation Spl1-1 Is a Nucleotide Substitution in the Internal Promoter of the Proline tRNACGG Gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Curr. Genet. 2009, 55, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.A.; Rutherford, K.M.; Hayles, J.; Lock, A.; Bähler, J.; Oliver, S.G.; Mata, J.; Wood, V. Fission Stories: Using PomBase to Understand Schizosaccharomyces pombe Biology. Genetics 2022, 220, iyab222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, K.M.; Lera-Ramírez, M.; Wood, V. PomBase: A Global Core Biodata Resource—Growth, Collaboration, and Sustainability. Genetics 2024, 227, iyae007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuno, T.; Tada, K.; Watanabe, Y. Kinetochore Geometry Defined by Cohesion within the Centromere. Nature 2009, 458, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregan, J.; Van Laer, L.; Lieto, L.D.; Van Camp, G.; Kearsey, S.E. A Yeast Model for the Study of Human DFNA5, a Gene Mutated in Nonsyndromic Hearing Impairment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2003, 1638, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Forsburg, S.L.; Rhind, N. Basic Methods for Fission Yeast. Yeast 2006, 23, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, S.; Klar, A.; Nurse, P. Molecular Genetic Analysis of Fission Yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; Volume 194, pp. 795–823. ISBN 978-0-12-182095-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sipiczki, M.; Ferenczy, L. Enzymic Methods for Enrichment of Fungal Mutants I. Enrichment of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Mutants. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1978, 50, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabitsch, K.P.; Gregan, J.; Schleiffer, A.; Javerzat, J.-P.; Eisenhaber, F.; Nasmyth, K. Two Fission Yeast Homologs of Drosophila Mei-S332 Are Required for Chromosome Segregation during Meiosis I and II. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs-Szabo, L.; Papp, L.A.; Takacs, S.; Miklos, I. Disruption of the Schizosaccharomyces japonicus Lig4 Disturbs Several Cellular Processes and Leads to a Pleiotropic Phenotype. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, S. Experiments with Fission Yeast: A Laboratory Course Manual. By Caroline Alfa, Peter Fantes, Jeremy Hyams, Maureen McLeod, and Emma Warwick. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 1993. ISBN 0 87969 424 6. Genet. Res. 1994, 63, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyne, R.; Burns, G.; Mata, J.; Penkett, C.J.; Rustici, G.; Chen, D.; Langford, C.; Vetrie, D.; Bähler, J. Whole-Genome Microarrays of Fission Yeast: Characteristics, Accuracy, Reproducibility, and Processing of Array Data. BMC Genom. 2003, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maundrell, K. Thiamine-Repressible Expression Vectors pREP and pRIP for Fission Yeast. Gene 1993, 123, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, H.L. High Efficiency Transformation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe by Electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992, 20, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatinos, S.A.; Forsburg, S.L. Molecular Genetics of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 470, pp. 759–795. ISBN 978-0-12-375172-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sevcovicova, A.; Plava, J.; Gazdarica, M.; Szabova, E.; Huraiova, B.; Gaplovska-Kysela, K.; Cipakova, I.; Cipak, L.; Gregan, J. Mapping and Analysis of Swi5 and Sfr1 Phosphorylation Sites. Genes 2021, 12, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipak, L.; Selicky, T.; Jurcik, J.; Cipakova, I.; Osadska, M.; Lukacova, V.; Barath, P.; Gregan, J. Tandem Affinity Purification Protocol for Isolation of Protein Complexes from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. STAR Protoc. 2022, 3, 101137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dereeper, A.; Audic, S.; Claverie, J.-M.; Blanc, G. BLAST-EXPLORER Helps You Building Datasets for Phylogenetic Analysis. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple Sequence Alignment with High Accuracy and High Throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.-M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: A Sequence Logo Generator: Figure 1. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, L.A.; Mezulis, S.; Yates, C.M.; Wass, M.N.; Sternberg, M.J.E. The Phyre2 Web Portal for Protein Modeling, Prediction and Analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dereeper, A.; Guignon, V.; Blanc, G.; Audic, S.; Buffet, S.; Chevenet, F.; Dufayard, J.-F.; Guindon, S.; Lefort, V.; Lescot, M.; et al. Phylogeny.Fr: Robust Phylogenetic Analysis for the Non-Specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, W465–W469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.-F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New Algorithms and Methods to Estimate Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies: Assessing the Performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castresana, J. Selection of Conserved Blocks from Multiple Alignments for Their Use in Phylogenetic Analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Van Der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice Across a Large Model Space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefort, V.; Longueville, J.-E.; Gascuel, O. SMS: Smart Model Selection in PhyML. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 2422–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelan, S.; Goldman, N. A General Empirical Model of Protein Evolution Derived from Multiple Protein Families Using a Maximum-Likelihood Approach. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001, 18, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anisimova, M.; Gascuel, O. Approximate Likelihood-Ratio Test for Branches: A Fast, Accurate, and Powerful Alternative. Syst. Biol. 2006, 55, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.X.; Jung, D.; Yao, R. ShinyGO: A Graphical Gene-Set Enrichment Tool for Animals and Plants. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2628–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Doi, A.; Fujimoto, A.; Sato, S.; Uno, T.; Kanda, Y.; Asami, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Kita, A.; Satoh, R.; Sugiura, R. Chemical Genomics Approach to Identify Genes Associated with Sensitivity to Rapamycin in the Fission Yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Cells 2015, 20, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, M.; Bordin, N.; Lees, J.; Scholes, H.; Hassan, S.; Saintain, Q.; Kamrad, S.; Orengo, C.; Bähler, J. Broad Functional Profiling of Fission Yeast Proteins Using Phenomics and Machine Learning. eLife 2023, 12, RP88229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnahan, R.H.; Feoktistova, A.; Ren, L.; Niessen, S.; Yates, J.R.; Gould, K.L. Dim1p Is Required for Efficient Splicing and Export of mRNA Encoding Lid1p, a Component of the Fission Yeast Anaphase-Promoting Complex. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullschleger, S.; Loewith, R.; Hall, M.N. TOR Signaling in Growth and Metabolism. Cell 2006, 124, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisman, R. Target of Rapamycin (TOR) Regulates Growth in Response to Nutritional Signals. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, T.; Otsubo, Y.; Urano, J.; Tamanoi, F.; Yamamoto, M. Loss of the TOR Kinase Tor2 Mimics Nitrogen Starvation and Activates the Sexual Development Pathway in Fission Yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 3154–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uritani, M.; Hidaka, H.; Hotta, Y.; Ueno, M.; Ushimaru, T.; Toda, T. Fission Yeast Tor2 Links Nitrogen Signals to Cell Proliferation and Acts Downstream of the Rheb GTPase. Genes Cells 2006, 11, 1367–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egel, R. Physiological Aspects of Conjugation in Fission Yeast. Planta 1971, 98, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristell, C.; Orzechowski Westholm, J.; Olsson, I.; Ronne, H.; Komorowski, J.; Bjerling, P. Nitrogen Depletion in the Fission Yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe Causes Nucleosome Loss in Both Promoters and Coding Regions of Activated Genes. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérard, M.; Merlini, L.; Martin, S.G. Proteomic and Phosphoproteomic Analyses Reveal That TORC1 Is Reactivated by Pheromone Signaling during Sexual Reproduction in Fission Yeast. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, E.; Weisman, R.; Sipiczki, M.; Miklos, I. Fhl1 Gene of the Fission Yeast Regulates Transcription of Meiotic Genes and Nitrogen Starvation Response, Downstream of the TORC1 Pathway. Curr. Genet. 2017, 63, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikai, N.; Nakazawa, N.; Hayashi, T.; Yanagida, M. The Reverse, but Coordinated, Roles of Tor2 (TORC1) and Tor1 (TORC2) Kinases for Growth, Cell Cycle and Separase-Mediated Mitosis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Open Biol. 2011, 1, 110007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, J.-P.; Legon, L.; Dabrowska, A.; Tricolici, A.-M.; Kumar, J.; Rallis, C. Interplays of AMPK and TOR in Autophagy Regulation in Yeast. Cells 2023, 12, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Habib, A.; Laor, D.; Yadav, S.; Kupiec, M.; Weisman, R. TOR Complex 2 in Fission Yeast Is Required for Chromatin-Mediated Gene Silencing and Assembly of Heterochromatic Domains at Subtelomeres. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 8138–8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhind, N.; Chen, Z.; Yassour, M.; Thompson, D.A.; Haas, B.J.; Habib, N.; Wapinski, I.; Roy, S.; Lin, M.F.; Heiman, D.I.; et al. Comparative Functional Genomics of the Fission Yeasts. Science 2011, 332, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acs-Szabo, L.; Papp, L.A.; Sipiczki, M.; Miklos, I. Genome Comparisons of the Fission Yeasts Reveal Ancient Collinear Loci Maintained by Natural Selection. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, B.A.; Brondello, J.-M.; Baber-Furnari, B.; Russell, P. Mechanism of Caffeine-Induced Checkpoint Override in Fission Yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 4288–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yanagida, M.; Ikai, N.; Shimanuki, M.; Sajiki, K. Nutrient Limitations Alter Cell Division Control and Chromosome Segregation through Growth-Related Kinases and Phosphatases. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2011, 366, 3508–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.J.; Ewald, J.C.; Skotheim, J.M. Cell Size Control in Yeast. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, R350–R359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuraba, Y. Molecular Basis of Nitrogen Starvation-Induced Leaf Senescence. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1013304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, R.W.; Kaeberlein, M.; Caldwell, S.D.; Kennedy, B.K.; Fields, S. Extension of Chronological Life Span in Yeast by Decreased TOR Pathway Signaling. Genes. Dev. 2006, 20, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, B.; Moreno, S. Fission Yeast Tor2 Promotes Cell Growth and Represses Cell Differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 4475–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.C.; Raposo, L.R.; Mira, N.P.; Lourenço, A.B.; Sá-Correia, I. Genome-Wide Identification of S Accharomyces cerevisiae Genes Required for Maximal Tolerance to Ethanol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 5761–5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.B.; Guimarães, P.M.; Gomes, D.G.; Mira, N.P.; Teixeira, M.C.; Sá-Correia, I.; Domingues, L. Identification of Candidate Genes for Yeast Engineering to Improve Bioethanol Production in Very High Gravity and Lignocellulosic Biomass Industrial Fermentations. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2011, 4, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romila, C.A.; Townsend, S.; Malecki, M.; Kamrad, S.; Rodríguez-López, M.; Hillson, O.; Cotobal, C.; Ralser, M.; Bähler, J. Barcode Sequencing and a High-Throughput Assay for Chronological Lifespan Uncover Ageing-Associated Genes in Fission Yeast. Microb. Cell 2021, 8, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisman, R.; Roitburg, I.; Schonbrun, M.; Harari, R.; Kupiec, M. Opposite Effects of Tor1 and Tor2 on Nitrogen Starvation Responses in Fission Yeast. Genetics 2007, 175, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Hang, J.; Wan, R.; Huang, M.; Wong, C.C.L.; Shi, Y. Structure of a Yeast Spliceosome at 3.6-Angstrom Resolution. Science 2015, 349, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Banerjee, S.; Bashir, S.; Vijayraghavan, U. Context Dependent Splicing Functions of Bud31/Ycr063w Define Its Role in Budding and Cell Cycle Progression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 424, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buker, S.M.; Iida, T.; Bühler, M.; Villén, J.; Gygi, S.P.; Nakayama, J.-I.; Moazed, D. Two Different Argonaute Complexes Are Required for siRNA Generation and Heterochromatin Assembly in Fission Yeast. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007, 14, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number of Genes | GO Categories |

|---|---|

| 13 | oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491) |

| 13 | hydrolase activity (GO:0016787), hydrolase activity, acting on glycosyl bonds (GO:0016798), hydrolase activity, acting on carbon-nitrogen (but not peptide) bonds (GO:0016810), hydrolase activity, acting on ester bonds (GO:0016788), ATP hydrolysis activity (GO:0016887) |

| 12 | nucleotidyltransferase activity (GO:0016779), glycosyltransferase activity (GO:0016757), acyltransferase activity (GO:0016746), transferase activity, transferring one-carbon groups (GO:0016741), transferase activity, transferring alkyl or aryl (other than methyl) groups (GO:0016765), transferase activity, transferring one-carbon groups (GO:0016741) |

| 9 | transmembrane transporter activity (GO:0022857) |

| 1 | vesicle-mediated transport (GO:0016192) |

| 3 | endomembrane system (GO:0012505), plasma membrane (GO:0005886) |

| 2 | lyase activity (GO:0016829) |

| 2 | isomerase activity (GO:0016853) |

| Gene Identifier | Gene Name | Description | GO Category | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAC869.04 | formamidase-like protein, implicated in cellular detoxification | hydrolase activity, acting on carbon-nitrogen (but not peptide) bonds (GO:0016810) | [68] | |

| SPBC1683.06c | urh1 | uridine ribohydrolase Urh1 | hydrolase activity, acting on glycosyl bonds (GO:0016798) | [68] |

| SPBC1683.02 | adenine deaminase | hydrolase activity, acting on glycosyl bonds (GO:0016798) | [68] | |

| SPAC11D3.14c | oxp2 | 5-oxoprolinase (ATP-hydrolizing) | hydrolase activity, acting on carbon-nitrogen (but not peptide) bonds (GO:0016810) | [68] |

| SPAC186.06 | phenazine biosynthesis PhzF protein family | isomerase activity (GO:0016853) | [68] | |

| SPBPB2B2.06c | efn1 | extracellular 5′-nucleotidase, human NT5E family | hydrolase activity, acting on ester bonds (GO:0016788) | [69] |

| SPAC3A11.10c | dpe1 | dipeptidyl peptidase, unknown specificity, implicated in glutathione metabolism | peptidase activity (GO:0008233) | [69] |

| SPBC725.03 | pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate oxidase | oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491) | [69] | |

| SPAC23C11.06c | vacuolar membrane hydrolase, implicated in protein catabolism or lipid metabolism | hydrolase activity (GO:0016787) | [69] | |

| SPAC139.05 | ssd2 | succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491) | [69] |

| SPBC16A3.02c | mitochondrial CH-OH group oxidoreductase, human RTN4IP1 ortholog, implicated in mitochondrial organization or tethering | oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491) | [69] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vig, I.; Acs-Szabo, L.; Benkő, Z.; Bagelova Polakova, S.; Papp, L.A.; Gregan, J.; Miklós, I. The BUD31 Homologous Gene in Schizosaccharomyces pombe Is Evolutionarily Conserved and Can Be Linked to Cellular Processes Regulated by the TOR Pathway. Cells 2025, 14, 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211736

Vig I, Acs-Szabo L, Benkő Z, Bagelova Polakova S, Papp LA, Gregan J, Miklós I. The BUD31 Homologous Gene in Schizosaccharomyces pombe Is Evolutionarily Conserved and Can Be Linked to Cellular Processes Regulated by the TOR Pathway. Cells. 2025; 14(21):1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211736

Chicago/Turabian StyleVig, Ildikó, Lajos Acs-Szabo, Zsigmond Benkő, Silvia Bagelova Polakova, László Attila Papp, Juraj Gregan, and Ida Miklós. 2025. "The BUD31 Homologous Gene in Schizosaccharomyces pombe Is Evolutionarily Conserved and Can Be Linked to Cellular Processes Regulated by the TOR Pathway" Cells 14, no. 21: 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211736

APA StyleVig, I., Acs-Szabo, L., Benkő, Z., Bagelova Polakova, S., Papp, L. A., Gregan, J., & Miklós, I. (2025). The BUD31 Homologous Gene in Schizosaccharomyces pombe Is Evolutionarily Conserved and Can Be Linked to Cellular Processes Regulated by the TOR Pathway. Cells, 14(21), 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211736