Proteomics of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patient iPSC-Derived Skeletal Muscle Cells Reveal Differential Expression of Cytoskeletal and Extracellular Matrix Proteins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC) Cultures

2.2. Skeletal Muscle Differentiation

2.3. Sample Preparation for Mass Spectrometry

2.4. Proteomic Analysis Using Mass Spectrometry

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Mass Spectrometry Analysis

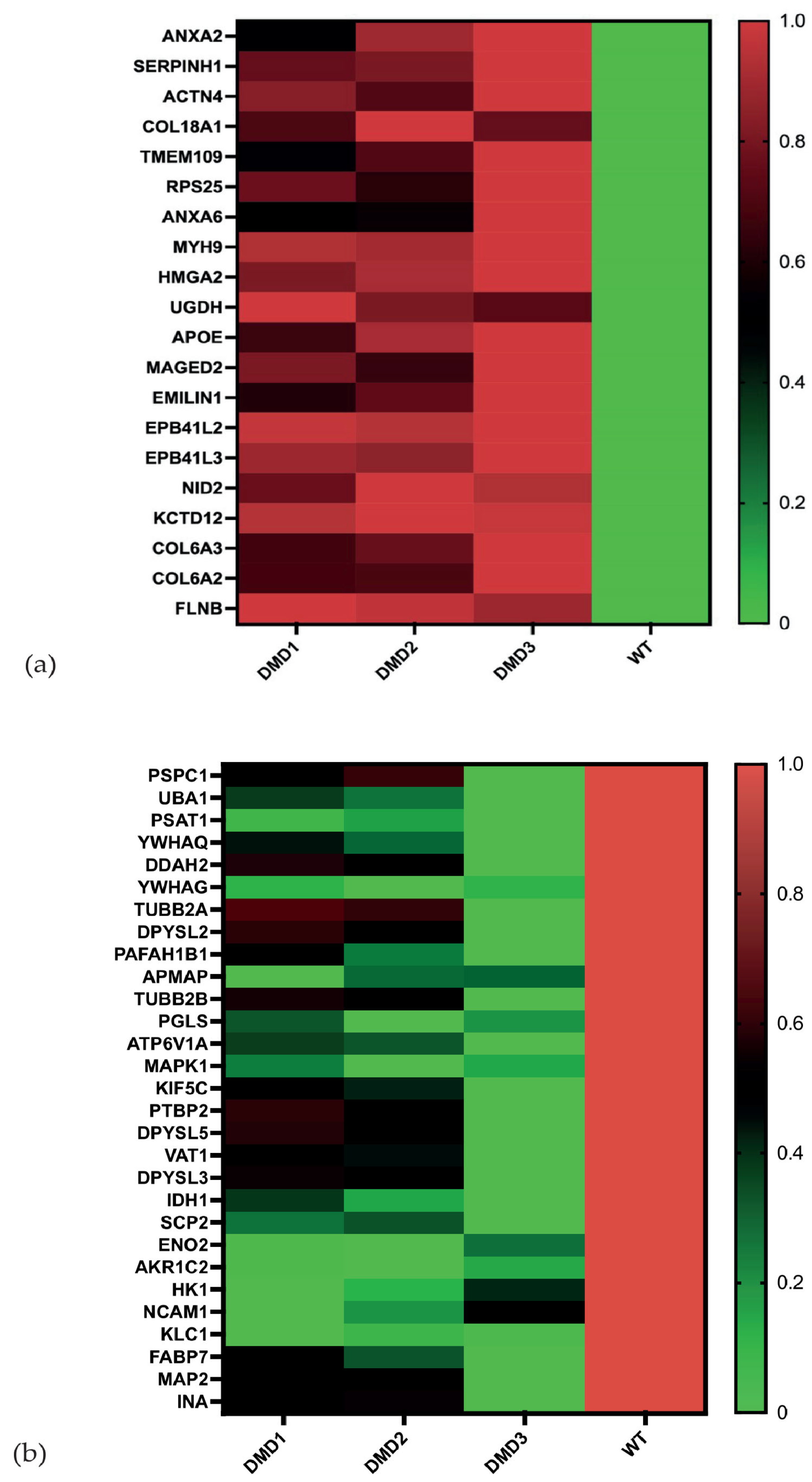

3.2. Analysis of Individual Proteins

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moat, S.J.; Bradley, D.M.; Salmon, R.; Clarke, A.; Hartley, L. Newborn Bloodspot Screening for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: 21 Years Experience in Wales (UK). Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.Q.; McNally, E.M. The Dystrophin Complex: Structure, Function, and Implications for Therapy. Compr. Physiol. 2015, 5, 1223–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanigan, K.M.; Dunn, D.M.; von Niederhausern, A.; Soltanzadeh, P.; Gappmaier, E.; Howard, M.T.; Sampson, J.B.; Mendell, J.R.; Wall, C.; King, W.M.; et al. Mutational Spectrum of DMD Mutations in Dystrophinopathy Patients: Application of Modern Diagnostic Techniques to a Large Cohort. Hum. Mutat. 2009, 30, 1657–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, R.; Kley, R. Muskelerkrankungen. In Neurologie; Hacke, W., Poeck, K., Wick, W., Eds.; Springer-Lehrbuch; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 827–859. ISBN 3662468913. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, G.Q.; McNally, E.M. Mechanisms of Muscle Degeneration, Regeneration, and Repair in the Muscular Dystrophies. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009, 71, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, N.C.; Chevalier, F.P.; Rudnicki, M.A. Satellite Cells in Muscular Dystrophy—Lost in Polarity. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecki, D.C.; Monaco, A.P.; Derry, J.M.; Walker, A.P.; Barnard, E.A.; Barnard, P.J. Expression of Four Alternative Dystrophin Transcripts in Brain Regions Regulated by Different Promoters. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1992, 1, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snow, W.M.; Anderson, J.E.; Jakobson, L.S. Neuropsychological and Neurobehavioral Functioning in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A Review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitanio, D.; Moriggi, M.; Torretta, E.; Barbacini, P.; De Palma, S.; Viganò, A.; Lochmüller, H.; Muntoni, F.; Ferlini, A.; Mora, M.; et al. Comparative Proteomic Analyses of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy and Becker Muscular Dystrophy Muscles: Changes Contributing to Preserve Muscle Function in Becker Muscular Dystrophy Patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Johnson, E.; Xu, R.; Martin, L.T.; Martin, P.T.; Montanaro, F. Comparative Proteomic Profiling of Dystroglycan-Associated Proteins in Wild Type, Mdx, and Galgt2 Transgenic Mouse Skeletal Muscle. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 4413–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayi, T.D.; Tawalbeh, S.M.; Ogundele, M.; Smith, H.R.; Samsel, A.M.; Barbieri, M.L.; Hathout, Y. Tandem Mass Tag-Based Serum Proteome Profiling for Biomarker Discovery in Young Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Boys. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 26504–26517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathout, Y.; Marathi, R.L.; Rayavarapu, S.; Zhang, A.; Brown, K.J.; Seol, H.; Gordish-Dressman, H.; Cirak, S.; Bello, L.; Nagaraju, K.; et al. Discovery of Serum Protein Biomarkers in the Mdx Mouse Model and Cross-Species Comparison to Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patients. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 6458–6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, S.; Zweyer, M.; Henry, M.; Meleady, P.; Mundegar, R.R.; Swandulla, D.; Ohlendieck, K. Proteomic Analysis of the Sarcolemma-Enriched Fraction from Dystrophic Mdx-4cv Skeletal Muscle. J. Proteom. 2019, 191, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chal, J.; Oginuma, M.; Al Tanoury, Z.; Gobert, B.; Sumara, O.; Hick, A.; Bousson, F.; Zidouni, Y.; Mursch, C.; Moncuquet, P.; et al. Differentiation of Pluripotent Stem Cells to Muscle Fiber to Model Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrommatis, L.; Jeong, H.-W.; Gomez-Giro, G.; Stehling, M.; Kienitz, M.-C.; Psathaki, O.E.; Bixel, M.G.; Morosan-Puopolo, G.; Gerovska, D.; Araúzo-Bravo, M.J.; et al. Human Skeletal Muscle Organoids Model Fetal Myogenesis and Sustain Uncommitted PAX7 Myogenic Progenitors. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindler, U.; Zaehres, H.; Mavrommatis, L. Generation of Skeletal Muscle Organoids from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Bio Protoc. 2024, 14, e4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrommatis, L.; Jeong, H.W.; Kindler, U.; Gomez-Giro, G.; Kienitz, M.C.; Stehling, M.; Psathaki, O.E.; Zeuschner, D.; Bixel, M.G.; Han, D.; et al. Human Skeletal Muscle Organoids Model Fetal Myogenesis and Sustain Uncommitted PAX7 Myogenic Progenitors. eLife 2023, 12, RP87081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindler, U.; Mavrommatis, L.; Käppler, F.; Hiluf, D.G.; Heilmann-Heimbach, S.; Marcus, K.; Günther Pomorski, T.; Vorgerd, M.; Brand-Saberi, B.; Zaehres, H. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patient IPSCs-Derived Skeletal Muscle Organoids Exhibit a Developmental Delay in Myogenic Progenitor Maturation. Cells 2025, 14, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.-H.; Arora, N.; Huo, H.; Maherali, N.; Ahfeldt, T.; Shimamura, A.; Lensch, M.W.; Cowan, C.; Hochedlinger, K.; Daley, G.Q. Disease-Specific Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell 2008, 134, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panopoulos, A.D.; D’Antonio, M.; Benaglio, P.; Williams, R.; Hashem, S.I.; Schuldt, B.M.; DeBoever, C.; Arias, A.D.; Garcia, M.; Nelson, B.C.; et al. IPSCORE: A Resource of 222 IPSC Lines Enabling Functional Characterization of Genetic Variation across a Variety of Cell Types. Stem Cell Rep. 2017, 8, 1086–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, I.; Klich, K.; Arauzo-Bravo, M.J.; Radstaak, M.; Santourlidis, S.; Ghanjati, F.; Radke, T.F.; Psathaki, O.E.; Hargus, G.; Kramer, J.; et al. Erythroid Differentiation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Is Independent of Donor Cell Type of Origin. Haematologica 2015, 100, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chal, J.; Al Tanoury, Z.; Hestin, M.; Gobert, B.; Aivio, S.; Hick, A.; Cherrier, T.; Nesmith, A.P.; Parker, K.K.; Pourquié, O. Generation of Human Muscle Fibers and Satellite-like Cells from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells in Vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1833–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plum, S.; Helling, S.; Theiss, C.; Leite, R.E.P.; May, C.; Jacob-Filho, W.; Eisenacher, M.; Kuhlmann, K.; Meyer, H.E.; Riederer, P.; et al. Combined Enrichment of Neuromelanin Granules and Synaptosomes from Human Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta Tissue for Proteomic Analysis. J. Proteom. 2013, 94, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, E.W.; Bandeira, N.; Perez-Riverol, Y.; Sharma, V.; Carver, J.J.; Mendoza, L.; Kundu, D.J.; Wang, S.; Bandla, C.; Kamatchinathan, S.; et al. The ProteomeXchange Consortium at 10 Years: 2023 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D1539–D1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Mann, M. MaxQuant Enables High Peptide Identification Rates, Individualized p.p.b.-Range Mass Accuracies and Proteome-Wide Protein Quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Neuhauser, N.; Michalski, A.; Scheltema, R.A.; Olsen, J.V.; Mann, M. Andromeda: A Peptide Search Engine Integrated into the MaxQuant Environment. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 1794–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A.; Martin, M.J.; Orchard, S.; Magrane, M.; Agivetova, R.; Ahmad, S.; Alpi, E.; Bowler-Barnett, E.H.; Britto, R.; Bursteinas, B.; et al. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D480–D489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GitHub—Mpc-Bioinformatics/ProtStatsWF: Statistics Workflows for Proteomics Data. Available online: https://github.com/mpc-bioinformatics/ProtStatsWF (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Välikangas, T.; Suomi, T.; Elo, L.L. A Systematic Evaluation of Normalization Methods in Quantitative Label-Free Proteomics. Brief. Bioinform. 2018, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and Integrative Analysis of Large Gene Lists Using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, B.T.; Hao, M.; Qiu, J.; Jiao, X.; Baseler, M.W.; Lane, H.C.; Imamichi, T.; Chang, W. DAVID: A Web Server for Functional Enrichment Analysis and Functional Annotation of Gene Lists (2021 Update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W216–W221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveros, J.C. (2007–2015) Venny. An Interactive Tool for Comparing Lists with Venn’s Diagrams.—References—Scientific Research Publishing. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2904043 (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- McCourt, J.L.; Stearns-Reider, K.M.; Mamsa, H.; Kannan, P.; Afsharinia, M.H.; Shu, C.; Gibbs, E.M.; Shin, K.M.; Kurmangaliyev, Y.Z.; Schmitt, L.R.; et al. Multi-Omics Analysis of Sarcospan Overexpression in Mdx Skeletal Muscle Reveals Compensatory Remodeling of Cytoskeleton-Matrix Interactions That Promote Mechanotransduction Pathways. Skelet. Muscle 2023, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carberry, S.; Brinkmeier, H.; Zhang, Y.; Winkler, C.K.; Ohlendieck, K. Comparative Proteomic Profiling of Soleus, Extensor Digitorum Longus, Flexor Digitorum Brevis and Interosseus Muscles from the Mdx Mouse Model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 32, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mournetas, V.; Massouridès, E.; Dupont, J.-B.; Kornobis, E.; Polvèche, H.; Jarrige, M.; Dorval, A.R.L.; Gosselin, M.R.F.; Manousopoulou, A.; Garbis, S.D.; et al. Myogenesis Modelled by Human Pluripotent Stem Cells: A Multi-Omic Study of Duchenne Myopathy Early Onset. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reggio, A.; Fuoco, C.; De Paolis, F.; Deodati, R.; Testa, S.; Celikkin, N.; Volpi, M.; Bernardini, S.; Fornetti, E.; Baldi, J.; et al. 3D Rotary Wet-Spinning (RoWS) Biofabrication Directly Affects Proteomic Signature and Myogenic Maturation in Muscle Pericyte–Derived Human Myo-Substitute. Aggregate 2025, 6, e727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.; Zweyer, M.; Mundegar, R.R.; Swandulla, D.; Ohlendieck, K. Comparative Gel-Based Proteomic Analysis of Chemically Crosslinked Complexes in Dystrophic Skeletal Muscle. Electrophoresis 2018, 39, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, P.; Gargan, S.; Zweyer, M.; Swandulla, D.; Ohlendieck, K. Extracellular Matrix Proteomics: The Mdx-4cv Mouse Diaphragm as a Surrogate for Studying Myofibrosis in Dystrophinopathy. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capkovic, K.L.; Stevenson, S.; Johnson, M.C.; Thelen, J.J.; Cornelison, D.D.W. Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (NCAM) Marks Adult Myogenic Cells Committed to Differentiation. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 1553–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscolo Sesillo, F.; Wong, M.; Cortez, A.; Alperin, M. Isolation of Muscle Stem Cells from Rat Skeletal Muscles. Stem Cell Res. 2020, 43, 101684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, M.; Puglisi, K.; Nist, A.; Raffeiner, P.; Bister, K. The Brain Acid-Soluble Protein 1 (BASP1) Interferes with the Oncogenic Capacity of MYC and Its Binding to Calmodulin. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, N.P.; Yeung, E.W.; Allen, D.G. Muscle Damage in Mdx (Dystrophic) Mice: Role of Calcium and Reactive Oxygen Species. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2006, 33, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Cheung, C.Y.; Seo, S.U.; Liu, H.; Pardeshi, L.; Wong, K.H.; Chow, L.M.C.; Chau, M.P.; Wang, Y.; Lee, A.R.; et al. RUVBL1/2 Complex Regulates Pro-Inflammatory Responses in Macrophages via Regulating Histone H3K4 Trimethylation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 679184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Warren, C.R. From 2D Myotube Cultures to 3D Engineered Skeletal Muscle Constructs: A Comprehensive Review of In Vitro Skeletal Muscle Models and Disease Modeling Applications. Cells 2025, 14, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, S.; Zhang, M. Fabrication of 3D Aligned Nanofibrous Tubes by Direct Electrospinning. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 2575–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozan, N.G.; Joshi, M.; Sicherer, S.T.; Grasman, J.M. Porous Biomaterial Scaffolds for Skeletal Muscle Tissue Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1245897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholobova, D.; Decroix, L.; Van Muylder, V.; Desender, L.; Gerard, M.; Carpentier, G.; Vandenburgh, H.; Thorrez, L. Endothelial Network Formation Within Human Tissue-Engineered Skeletal Muscle. Tissue Eng. Part A 2015, 21, 2548–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahin-Shamsabadi, A.; Selvaganapathy, P.R. A 3D Self-Assembled In Vitro Model to Simulate Direct and Indirect Interactions between Adipocytes and Skeletal Muscle Cells. Adv. Biosyst. 2020, 4, 2000034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Langerman, J.; Sabri, S.; Chien, P.; Young, C.S.; Younesi, S.; Hicks, M.; Gonzalez, K.; Fujiwara, W.; Marzi, J.; et al. A Human Skeletal Muscle Atlas Identifies the Trajectories of Stem and Progenitor Cells across Development and from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 27, 158–176.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauper, M.; Hentschel, A.; Tiburcy, M.; Beltran, S.; Ruck, T.; Schara-Schmidt, U.; Roos, A. Proteomic Profiling Towards a Better Understanding of Genetic Based Muscular Diseases: The Current Picture and a Look to the Future. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein | Tukey-Test p-Value DMD1 | Tukey-Test p-Value DMD2 | Tukey-Test p-Value DMD3 | ANOVA FDR p-Value | FC (DMD1/WT) | FC (DMD2/WT) | FC (DMD3/WT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYH9 | 0.0001 ** | 0.00009 *** | 0.0002 ** | 0.00004 *** | 2.67 | 2.59 | 2.88 |

| COL18A | 0.002 ** | 0.003 ** | 0.01 * | 0.013 * | 2.02 | 2.80 | 2.20 |

| TPM1 | / | / | 0.014 * | 0.016 * | 0.77 | 1.24 | 12.21 |

| BASP1 | / | / | 0.02 * | 0.017 * | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.36 |

| RUVBL1 | / | / | 0.018 * | 0.022 * | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.64 |

| NCAM1 | 0.009 * | 0.004 ** | 0.048 * | 0.0046 ** | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.50 |

| Protein | Tukey-Test p-Value DMD1 | Tukey-Test p-Value DMD2 | Tukey-Test p-Value DMD3 | ANOVA FDR p-Value | FC (DMD1/WT) | FC (DMD2/WT) | FC (DMD3/WT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYH9 | / | / | 0.008 * | 0.007 * | 1.01 | 1.11 | 4.31 |

| COL18A | / | / | 0.01 * | 0.011 * | 5.83 | 0.60 | 10.17 |

| TPM1 | / | / | 0.002 ** | 0.0005 ** | 1.15 | 1.51 | 5.35 |

| BASP1 | / | / | 0.005 * | 0.006 * | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.34 |

| RUVBL1 | / | / | 0.008 * | 0.0006 ** | 1.03 | 0.76 | 0.41 |

| NCAM1 | / | / | / | / | 0.38 | 0.80 | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gallert, S.-M.; Fölsch, M.; Mavrommatis, L.; Kindler, U.; Schork, K.; Eisenacher, M.; Vorgerd, M.; Brand-Saberi, B.; Eggers, B.; Marcus, K.; et al. Proteomics of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patient iPSC-Derived Skeletal Muscle Cells Reveal Differential Expression of Cytoskeletal and Extracellular Matrix Proteins. Cells 2025, 14, 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211688

Gallert S-M, Fölsch M, Mavrommatis L, Kindler U, Schork K, Eisenacher M, Vorgerd M, Brand-Saberi B, Eggers B, Marcus K, et al. Proteomics of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patient iPSC-Derived Skeletal Muscle Cells Reveal Differential Expression of Cytoskeletal and Extracellular Matrix Proteins. Cells. 2025; 14(21):1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211688

Chicago/Turabian StyleGallert, Sarah-Marie, Mitja Fölsch, Lampros Mavrommatis, Urs Kindler, Karin Schork, Martin Eisenacher, Matthias Vorgerd, Beate Brand-Saberi, Britta Eggers, Katrin Marcus, and et al. 2025. "Proteomics of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patient iPSC-Derived Skeletal Muscle Cells Reveal Differential Expression of Cytoskeletal and Extracellular Matrix Proteins" Cells 14, no. 21: 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211688

APA StyleGallert, S.-M., Fölsch, M., Mavrommatis, L., Kindler, U., Schork, K., Eisenacher, M., Vorgerd, M., Brand-Saberi, B., Eggers, B., Marcus, K., & Zaehres, H. (2025). Proteomics of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Patient iPSC-Derived Skeletal Muscle Cells Reveal Differential Expression of Cytoskeletal and Extracellular Matrix Proteins. Cells, 14(21), 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14211688