Understanding the Cytomegalovirus Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Ortholog pUL97 as a Multifaceted Regulator and an Antiviral Drug Target

Abstract

1. Aspects of Human Herpesvirus Pathogenesis and Antiviral Therapy

1.1. General Features of Human Pathogenic Herpesvirus Infections

1.2. Current Antiherpesviral Therapeutic Options and the First Approved Antiviral Kinase Inhibitor

2. Herpesvirus-Encoded Protein Kinases

2.1. The Functional Complexity of Herpesviral Protein Kinases

2.2. Herpesviral Protein Kinases as a Potential Novel Group of Antiviral Drug Targets

3. The Viral Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Ortholog (vCDK)

3.1. Structural Similarity between Herpesviral and Host Kinases of the CDK Group

3.2. Functional Similarities and CDK-Like Activities of Herpesviral Protein Kinases

3.3. Identical Substrate Proteins and Host Interactors Shared by Host CDKs and vCDKs

3.4. Cyclin-Binding Properties of the Herpesviral CDK-Like Kinases

4. Evidence for the Functional Significance of HvPKs in Herpesviral Replication

4.1. Functional Aspects of the Conserved (UL) and Nonconserved Gene Group (US) of HvPKs

5. Chances, Challenges, and Current State of vCDK- and CDK-Specific Antiviral Drugs

5.1. Antiviral Validation Steps of the HCMV vCDK/pUL97

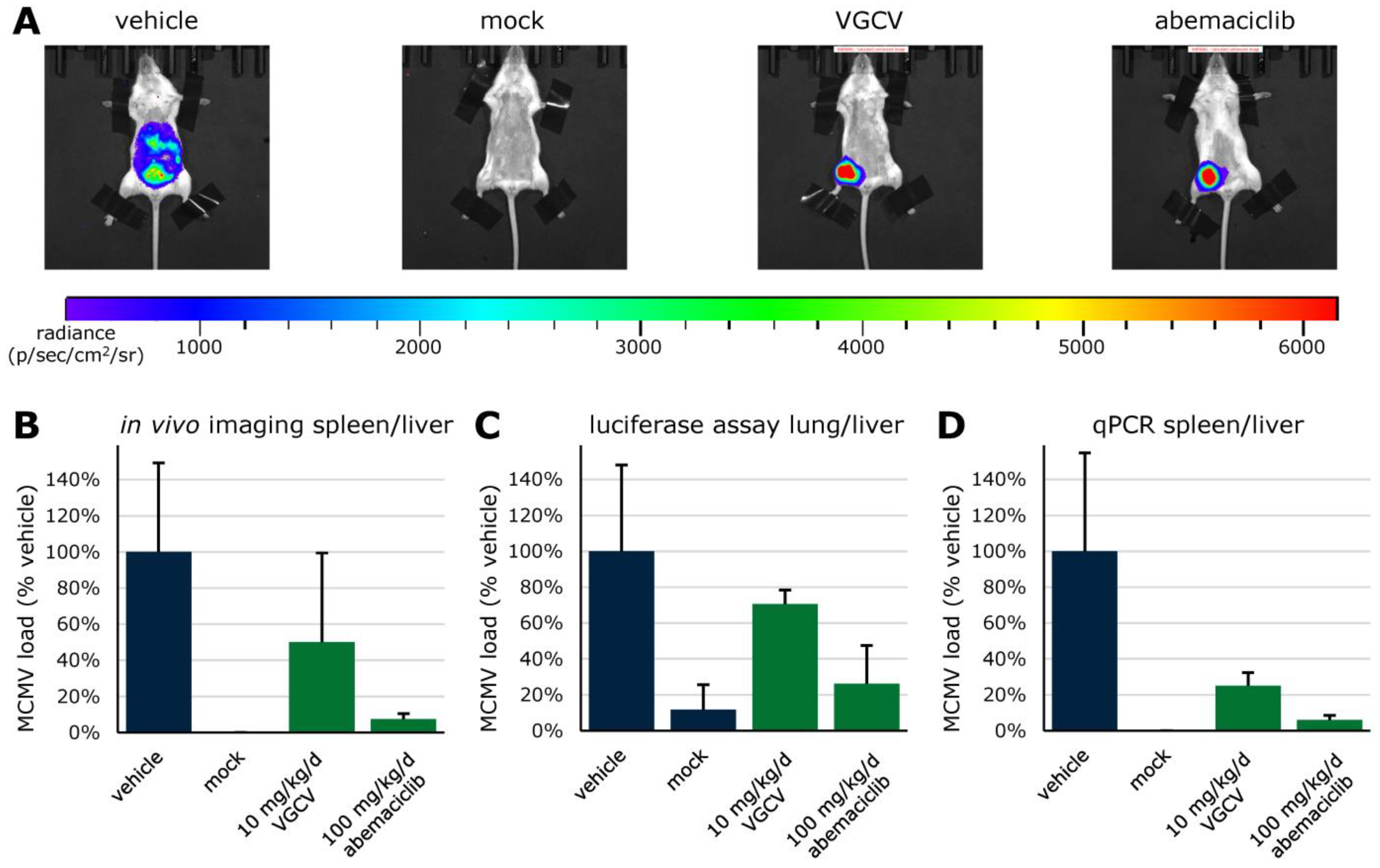

5.2. Discovery of Host CDKs as Very Potent Targets for Novel Anti-HCMV Strategies

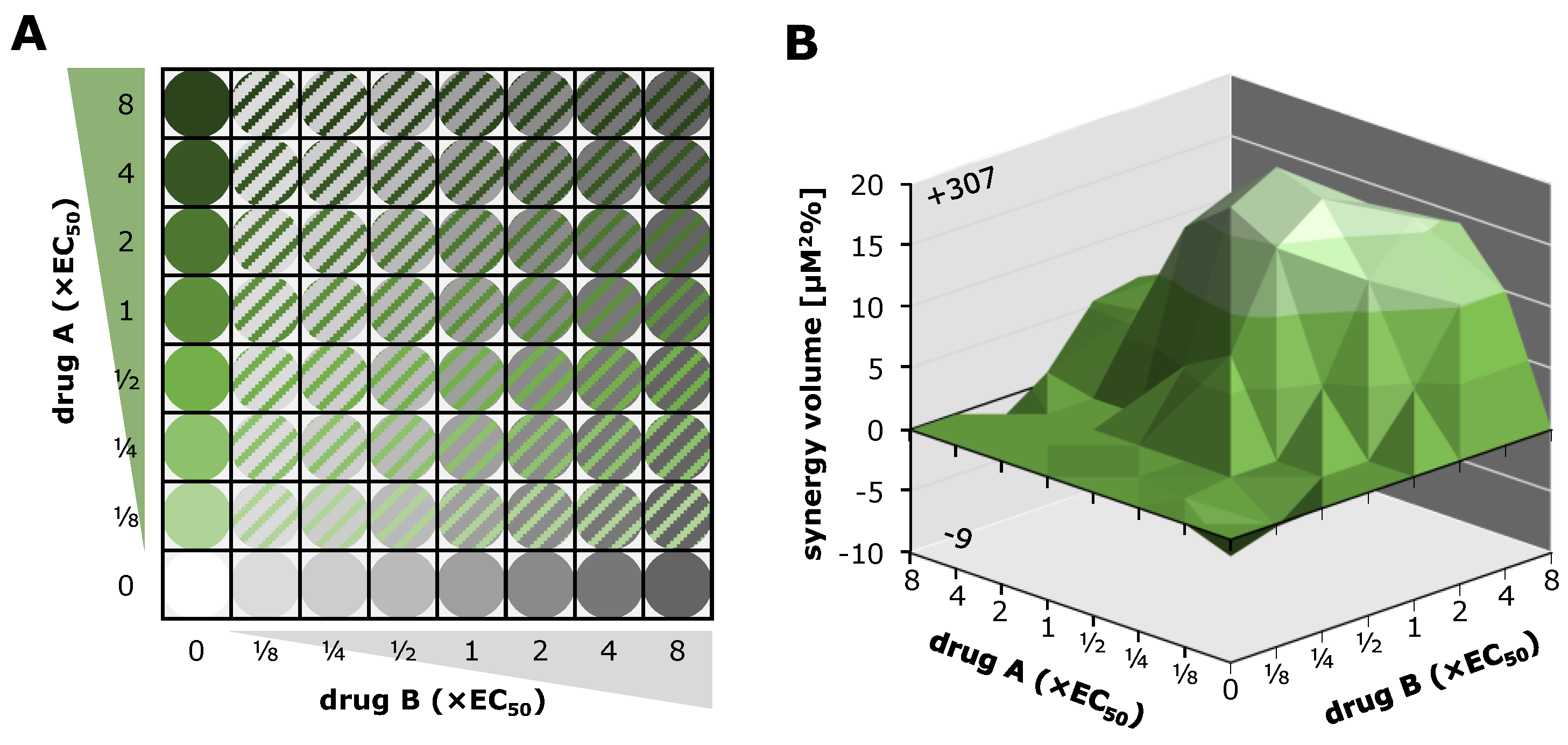

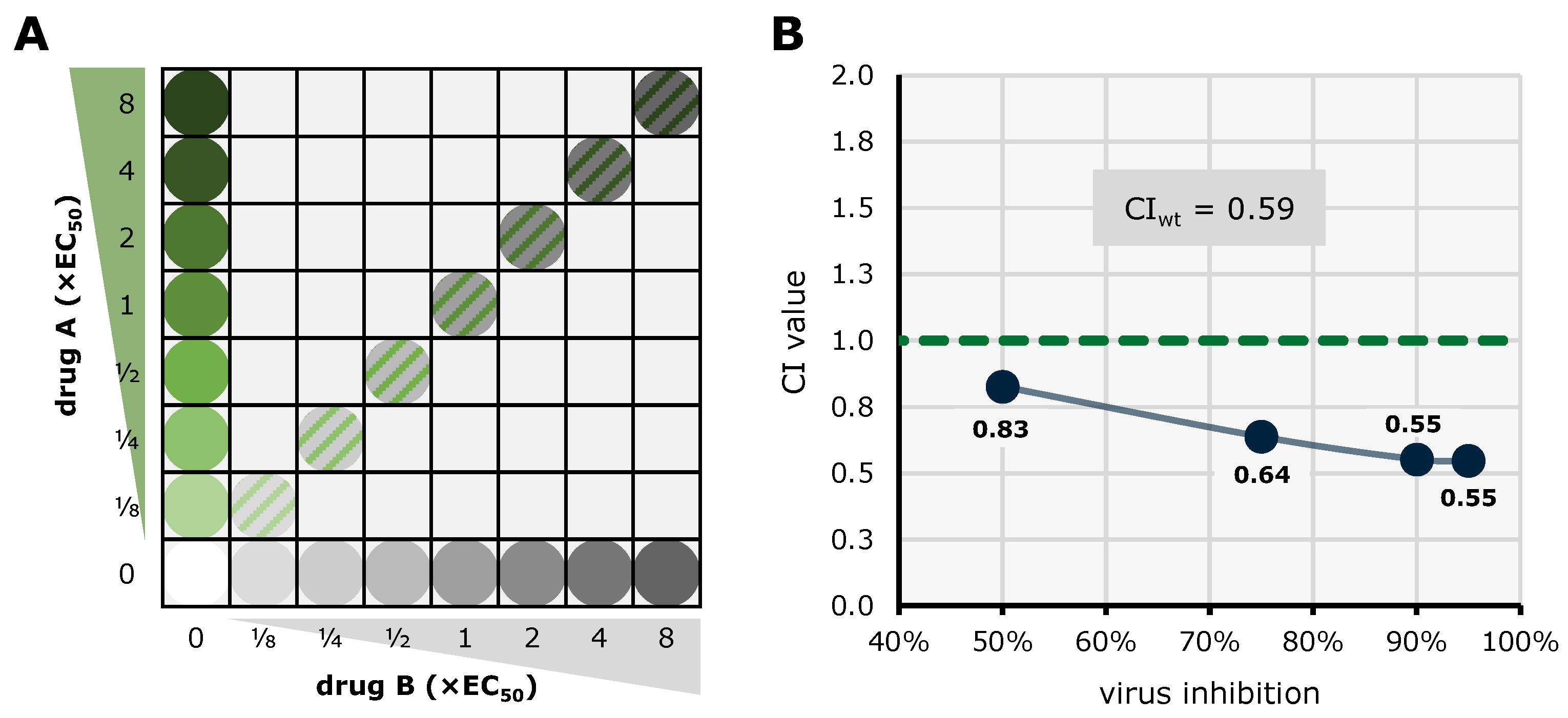

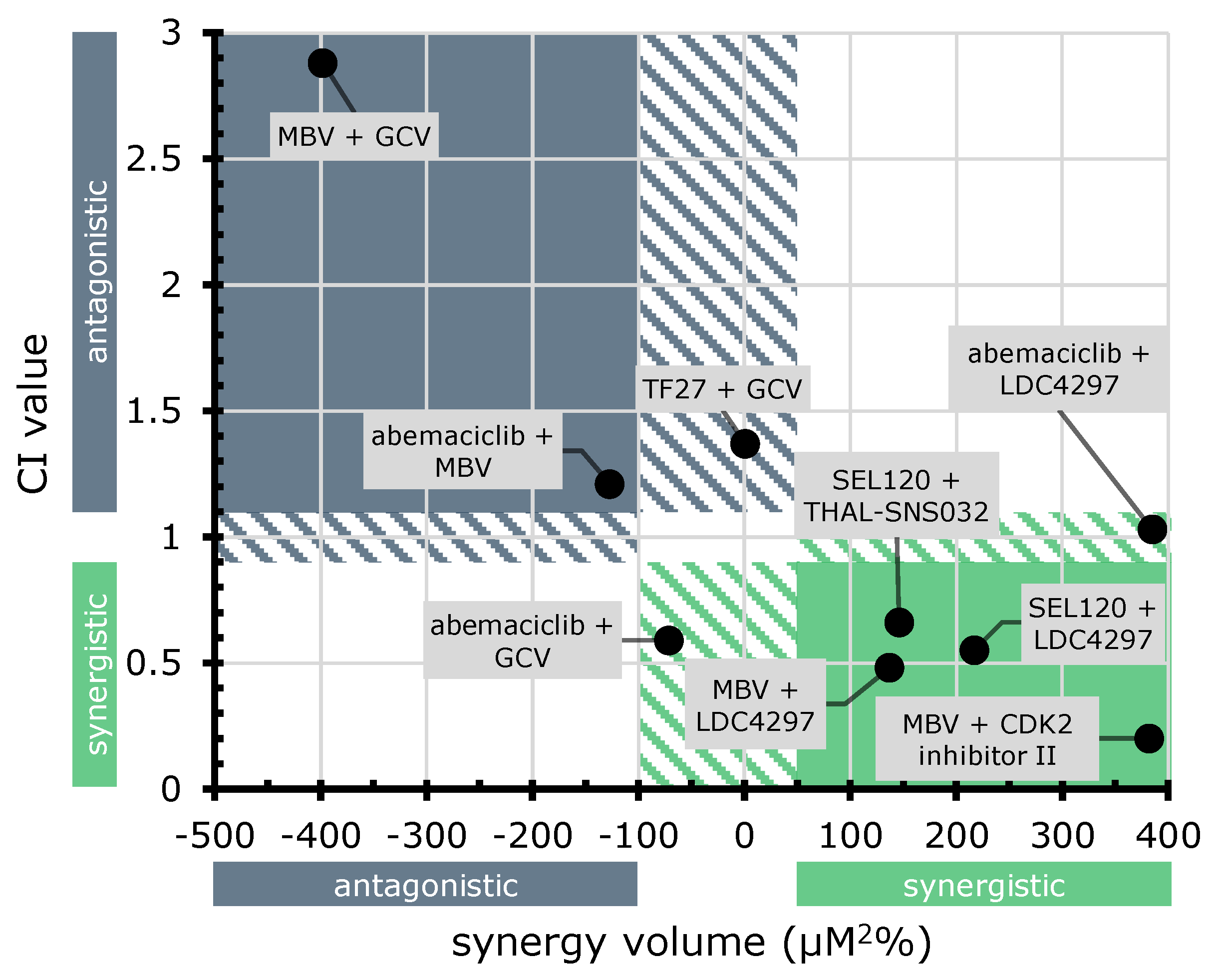

5.3. Synergistic Potential of Direct-Acting (vCDK) and Host-Directed (CDK) Kinase Inhibitors

6. Current Options of Pharmacological Enhancement of Kinase Inhibitors’ Antiviral Efficacy

6.1. ATP-Competitive, Substrate-Competitive, and Cyclin-Competitive vCDK Inhibitors

6.2. Mechanistical Enhancement of Investigational vCDK Inhibitors

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krug, L.T.; Pellett, P.E. The family Herpesviridae: A Brief Introduction. In Fields Virology: DNA Viruses, 7th ed.; Howley, P.M., Knipe, D.M., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 212–234. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, R.K.; Alain, S.; Alexander, B.D.; Blumberg, E.A.; Chemaly, R.F.; Cordonnier, C.; Duarte, R.F.; Florescu, D.F.; Kamar, N.; Kumar, D.; et al. Maribavir for Refractory Cytomegalovirus Infections with or without Resistance Post-Transplant: Results from a Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeckh, M.; Leisenring, W.; Riddell, S.R.; Bowden, R.A.; Huang, M.L.; Myerson, D.; Stevens-Ayers, T.; Flowers, M.E.; Cunningham, T.; Corey, L. Late cytomegalovirus disease and mortality in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants: Importance of viral load and T-cell immunity. Blood 2003, 101, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atabani, S.F.; Smith, C.; Atkinson, C.; Aldridge, R.W.; Rodriguez-Perálvarez, M.; Rolando, N.; Harber, M.; Jones, G.; O’Riordan, A.; Burroughs, A.K.; et al. Cytomegalovirus replication kinetics in solid organ transplant recipients managed by preemptive therapy. Am. J. Transplant. 2012, 12, 2457–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, J.; Ramil, C.; Green, M. Current management strategies for the prevention and treatment of cytomegalovirus infection in pediatric transplant recipients. Paediatr. Drugs 2002, 4, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlinson, W.D.; Boppana, S.B.; Fowler, K.B.; Kimberlin, D.W.; Lazzarotto, T.; Alain, S.; Daly, K.; Doutré, S.; Gibson, L.; Giles, M.L.; et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy and the neonate: Consensus recommendations for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e177–e188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjornevik, K.; Cortese, M.; Healy, B.C.; Kuhle, J.; Mina, M.J.; Leng, Y.; Elledge, S.J.; Niebuhr, D.W.; Scher, A.I.; Munger, K.L.; et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanz, T.V.; Brewer, R.C.; Ho, P.P.; Moon, J.S.; Jude, K.M.; Fernandez, D.; Fernandes, R.A.; Gomez, A.M.; Nadj, G.S.; Bartley, C.M.; et al. Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature 2022, 603, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vietzen, H.; Berger, S.M.; Kühner, L.M.; Furlano, P.L.; Bsteh, G.; Berger, T.; Rommer, P.; Puchhammer-Stöckl, E. Ineffective control of Epstein-Barr-virus-induced autoimmunity increases the risk for multiple sclerosis. Cell 2023, 186, 5705–5718.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Baraniak, I.; Reeves, M. The pathogenesis of human cytomegalovirus. J. Pathol. 2015, 235, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourin, C.; Alain, S.; Hantz, S. Anti-CMV therapy, what next? A systematic review. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1321116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.L.; Mathias, R.A. The human cytomegalovirus decathlon: Ten critical replication events provide opportunities for restriction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1053139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Page, A.K.; Jager, M.M.; Iwasenko, J.M.; Scott, G.M.; Alain, S.; Rawlinson, W.D. Clinical aspects of cytomegalovirus antiviral resistance in solid organ transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, V.M.; Ussetti, P.; de Pablo, A.; Iturbe, D.; Laporta, R.; Alonso, R.; Aguilar, M.; Quezada, C.A.; Cifrián, J.M. Evaluation of Two Different CMV-Immunoglobulin Regimens for Combined CMV Prophylaxis in High-Risk Patients following Lung Transplant. Microorganisms 2022, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cristanziano, V.; Affeldt, P.; Trappe, M.; Wirtz, M.; Heger, E.; Knops, E.; Kaiser, R.; Stippel, D.; Müller, R.U.; Holtick, U.; et al. Combined Therapy with Intravenous Immunoglobulins, Letermovir and (Val-)Ganciclovir in Complicated Courses of CMV-Infection in Transplant Recipients. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, P.A.; Kamar, N.; Saliba, F.; Baldanti, F.; Aguado, J.M.; Gottlieb, J.; Banas, B.; Potena, L. Cytomegalovirus Management in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: A Pre-COVID-19 Survey from the Working Group of the European Society for Organ Transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2022, 35, 10332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodson, E.M.; Jones, C.A.; Strippoli, G.F.; Webster, A.C.; Craig, J.C. Immunoglobulins, vaccines or interferon for preventing cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 18, Cd005129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaros, N.; Mayer, B.; Schachner, T.; Laufer, G.; Kocher, A. CMV-hyperimmune globulin for preventing cytomegalovirus infection and disease in solid organ transplant recipients: A meta-analysis. Clin. Transplant. 2008, 22, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barten, M.J.; Baldanti, F.; Staus, A.; Hüber, C.M.; Glynou, K.; Zuckermann, A. Effectiveness of Prophylactic Human Cytomegalovirus Hyperimmunoglobulin in Preventing Cytomegalovirus Infection following Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life 2022, 12, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ríos, E.; Nuévalos, M.; Mancebo, F.J.; Pérez-Romero, P. Is It Feasible to Use CMV-Specific T-Cell Adoptive Transfer as Treatment against Infection in SOT Recipients? Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 657144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasenko, J.M.; Scott, G.M.; Ziegler, J.B.; Rawlinson, W.D. Emergence and persistence of multiple antiviral-resistant CMV strains in a highly immunocompromised child. J. Clin. Virol. 2007, 40, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasenko, J.M.; Scott, G.M.; Naing, Z.; Glanville, A.R.; Rawlinson, W.D. Diversity of antiviral-resistant human cytomegalovirus in heart and lung transplant recipients. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2011, 13, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, G.M.; Naing, Z.; Pavlovic, J.; Iwasenko, J.M.; Angus, P.; Jones, R.; Rawlinson, W.D. Viral factors influencing the outcome of human cytomegalovirus infection in liver transplant recipients. J. Clin. Virol. 2011, 51, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naing, Z.; Hamilton, S.T.; van Zuylen, W.J.; Scott, G.M.; Rawlinson, W.D. Differential Expression of PDGF Receptor-α in Human Placental Trophoblasts Leads to Different Entry Pathways by Human Cytomegalovirus Strains. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinner, M.L.; Lam, S.W.; Koval, C.E.; Athans, V. Recommended foscarnet dose is not associated with improved outcomes in cytomegalovirus salvage therapy. J. Clin. Virol. 2019, 120, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Hayes, S.; Farrell, C.; Song, I.H. Population pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation of maribavir to support dose selection and regulatory approval in adolescents with posttransplant refractory cytomegalovirus. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, M.; DeVoe, C.; Spottiswoode, N.; Doernberg, S.B. Maribavir for Cytomegalovirus Treatment in the Real World-Not a Silver Bullet. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofac686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.; Song, K.; Wu, J.; Bo, T.; Crumpacker, C. Drug Resistance Mutations and Associated Phenotypes Detected in Clinical Trials of Maribavir for Treatment of Cytomegalovirus Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.; Alain, S.; Cervera, C.; Chemaly, R.F.; Kotton, C.N.; Lundgren, J.; Papanicolaou, G.A.; Pereira, M.R.; Wu, J.J.; Murray, R.A.; et al. Drug Resistance Assessed in a Phase 3 Clinical Trial of Maribavir Therapy for Refractory or Resistant Cytomegalovirus Infection in Transplant Recipients. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 229, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgenson, M.R.; Kleiboeker, H.; Garg, N.; Parajuli, S.; Mandelbrot, D.A.; Odorico, J.S.; Saddler, C.M.; Smith, J.A. Letermovir conversion after valganciclovir treatment in cytomegalovirus high-risk abdominal solid organ transplant recipients may promote development of cytomegalovirus-specific cell mediated immunity. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2022, 24, e13766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hoerschelmann, E.; Münch, J.; Gao, L.; Lücht, C.; Naik, M.G.; Schmidt, D.; Pitzinger, P.; Michel, D.; Avaniadi, P.; Schrezenmeier, E.; et al. Letermovir Rescue Therapy in Kidney Transplant Recipients with Refractory/Resistant CMV Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, F.; Lempinen, M.; Aaltonen, S.; Koivuviita, N.; Helanterä, I. Letermovir treatment for CMV infection in kidney and pancreas transplantation: A valuable option for complicated cases. Clin. Transplant. 2022, 36, e14537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perchetti, G.A.; Biernacki, M.A.; Xie, H.; Castor, J.; Joncas-Schronce, L.; Ueda Oshima, M.; Kim, Y.; Jerome, K.R.; Sandmaier, B.M.; Martin, P.J.; et al. Cytomegalovirus breakthrough and resistance during letermovir prophylaxis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2023, 58, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, K.A.; Kovacs, C.; Mullane, K.M.; Wolfe, C.; Clark, N.M.; La Hoz, R.M.; Smith, J.; Kotton, C.N.; Limaye, A.P.; Malinis, M.; et al. Letermovir treatment of cytomegalovirus infection or disease in solid organ and hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2021, 23, e13687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marschall, M.; Feichtinger, S.; Milbradt, J. Regulatory roles of protein kinases in cytomegalovirus replication. Adv. Virus Res. 2011, 80, 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webel, R.; Hakki, M.; Prichard, M.N.; Rawlinson, W.D.; Marschall, M.; Chou, S. Differential properties of cytomegalovirus pUL97 kinase isoforms affect viral replication and maribavir susceptibility. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4776–4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuny, C.V.; Chinchilla, K.; Culbertson, M.R.; Kalejta, R.F. Cyclin-dependent kinase-like function is shared by the beta- and gamma- subset of the conserved herpesvirus protein kinases. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, D.; Mertens, T. The UL97 protein kinase of human cytomegalovirus and homologues in other herpesviruses: Impact on virus and host. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1697, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zeijl, M.; Fairhurst, J.; Baum, E.Z.; Sun, L.; Jones, T.R. The human cytomegalovirus UL97 protein is phosphorylated and a component of virions. Virology 1997, 231, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steingruber, M.; Marschall, M. The Cytomegalovirus Protein Kinase pUL97:Host Interactions, Regulatory Mechanisms and Antiviral Drug Targeting. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershburg, E.; Pagano, J.S. Conserved herpesvirus protein kinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1784, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, M.N. Function of human cytomegalovirus UL97 kinase in viral infection and its inhibition by maribavir. Rev. Med. Virol. 2009, 19, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biron, K.K.; Harvey, R.J.; Chamberlain, S.C.; Good, S.S.; Smith, A.A., III; Davis, M.G.; Talarico, C.L.; Miller, W.H.; Ferris, R.; Dornsife, R.E. Potent and selective inhibition of human cytomegalovirus replication by 1263W94, a benzimidazole L-riboside with a unique mode of action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2365–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prichard, M.N.; Gao, N.; Jairath, S.; Mulamba, G.; Krosky, P.; Coen, D.M.; Parker, B.O.; Pari, G.S. A recombinant human cytomegalovirus with a large deletion in UL97 has a severe replication deficiency. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 5663–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.G.; Courcelle, C.T.; Prichard, M.N.; Mocarski, E.S. Distinct and separate roles for herpesvirus-conserved UL97 kinase in cytomegalovirus DNA synthesis and encapsidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 1895–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S. Advances in the genotypic diagnosis of cytomegalovirus antiviral drug resistance. Antiviral. Res. 2020, 176, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schregel, V.; Auerochs, S.; Jochmann, R.; Maurer, K.; Stamminger, T.; Marschall, M. Mapping of a self-interaction domain of the cytomegalovirus protein kinase pUL97. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.P.; Chen, M.R. Escape of herpesviruses from the nucleus. Rev. Med. Virol. 2010, 20, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippakis, H.; Spandidos, D.A.; Sourvinos, G. Herpesviruses: Hijacking the Ras signaling pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1803, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Qin, Z. Eph receptors: The bridge linking host and virus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2355–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Chamorro, L.; Felip, E.; Ezeonwumelu, I.J.; Margelí, M.; Ballana, E. Cyclin-dependent Kinases as Emerging Targets for Developing Novel Antiviral Therapeutics. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, J.V.; Brooks, G. The mammalian cell cycle: An overview. Methods Mol. Biol. 2005, 296, 113–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagga, S.; Bouchard, M.J. Cell cycle regulation during viral infection. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1170, 165–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertel, L.; Chou, S.; Mocarski, E.S. Viral and cell cycle–regulated kinases in cytomegalovirus-induced pseudomitosis and replication. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, J.P.; Kowalik, T.F. HCMV infection: Modulating the cell cycle and cell death. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 23, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, D.H. Human cytomegalovirus riding the cell cycle. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 204, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hume, A.J.; Finkel, J.S.; Kamil, J.P.; Coen, D.M.; Culbertson, M.R.; Kalejta, R.F. Phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein by viral protein with cyclin-dependent kinase function. Science 2008, 320, 797–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prichard, M.N.; Sztul, E.; Daily, S.L.; Perry, A.L.; Frederick, S.L.; Gill, R.B.; Hartline, C.B.; Streblow, D.N.; Varnum, S.M.; Smith, R.D.; et al. Human cytomegalovirus UL97 kinase activity is required for the hyperphosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein and inhibits the formation of nuclear aggresomes. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5054–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, A.R.; Yu, D. Control the host cell cycle: Viral regulation of the anaphase-promoting complex. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 8818–8825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eifler, M.; Uecker, R.; Weisbach, H.; Bogdanow, B.; Richter, E.; König, L.; Vetter, B.; Lenac-Rovis, T.; Jonjic, S.; Neitzel, H.; et al. PUL21a-Cyclin A2 interaction is required to protect human cytomegalovirus-infected cells from the deleterious consequences of mitotic entry. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanow, B.; Phan, Q.V.; Wiebusch, L. Emerging Mechanisms of G(1)/S Cell Cycle Control by Human and Mouse Cytomegaloviruses. mBio 2021, 12, e0293421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malumbres, M. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, E.; Ribeiro, M.P.C.; Clotet, J. Atypical cyclins: The extended family portrait. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, T.; Rosenthal, E.T.; Youngblom, J.; Distel, D.; Hunt, T. Cyclin: A protein specified by maternal mRNA in sea urchin eggs that is destroyed at each cleavage division. Cell 1983, 33, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Alonso, D.; Malumbres, M. Mammalian cell cycle cyclins. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2020, 107, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hydbring, P.; Malumbres, M.; Sicinski, P. Non-canonical functions of cell cycle cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bregman, D.B.; Pestell, R.G.; Kidd, V.J. Cell cycle regulation and RNA polymerase II. Front. Biosci. 2000, 5, D244–D257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sava, G.P.; Fan, H.; Coombes, R.C.; Buluwela, L.; Ali, S. CDK7 inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 805–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuman, E.; Ladha, M.H.; Lin, N.; Upton, T.M.; Miller, S.J.; DiRenzo, J.; Pestell, R.G.; Hinds, P.W.; Dowdy, S.F.; Brown, M.; et al. Cyclin D1 stimulation of estrogen receptor transcriptional activity independent of cdk4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997, 17, 5338–5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Tang, Y.D.; Zheng, C. When cyclin-dependent kinases meet viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 2962–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Sanyal, S.; Bruzzone, R. Breaking Bad: How Viruses Subvert the Cell Cycle. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R.; Costa, H.; Parkhouse, R.M. Virus manipulation of cell cycle. Protoplasma 2012, 249, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.E.; Spector, D.H. Studies on the Contribution of Human Cytomegalovirus UL21a and UL97 to Viral Growth and Inactivation of the Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C) E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Reveal a Unique Cellular Mechanism for Downmodulation of the APC/C Subunits APC1, APC4, and APC5. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 6928–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, R.W.; Deshaies, R.J.; Peters, J.M.; Kirschner, M.W. How proteolysis drives the cell cycle. Science 1996, 274, 1652–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malumbres, M.; Barbacid, M. Mammalian cyclin-dependent kinases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005, 30, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Kaldis, P. Cdks, cyclins and CKIs: Roles beyond cell cycle regulation. Development 2013, 140, 3079–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echalier, A.; Endicott, J.A.; Noble, M.E. Recent developments in cyclin-dependent kinase biochemical and structural studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peissert, S.; Schlosser, A.; Kendel, R.; Kuper, J.; Kisker, C. Structural basis for CDK7 activation by MAT1 and Cyclin H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26739–26748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schachter, M.M.; Merrick, K.A.; Larochelle, S.; Hirschi, A.; Zhang, C.; Shokat, K.M.; Rubin, S.M.; Fisher, R.P. A Cdk7-Cdk4 T-loop phosphorylation cascade promotes G1 progression. Mol. Cell 2013, 50, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schachter, M.M.; Fisher, R.P. The CDK-activating kinase Cdk7: Taking yes for an answer. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 3239–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larochelle, S.; Chen, J.; Knights, R.; Pandur, J.; Morcillo, P.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Suter, B.; Fisher, R.P. T-loop phosphorylation stabilizes the CDK7-cyclin H-MAT1 complex in vivo and regulates its CTD kinase activity. Embo J. 2001, 20, 3749–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolli, G.; Lowe, E.D.; Brown, N.R.; Johnson, L.N. The crystal structure of human CDK7 and its protein recognition properties. Structure 2004, 12, 2067–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimel, J.K.; Taatjes, D.J. The essential and multifunctional TFIIH complex. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 1018–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, D.; Pavić, I.; Zimmermann, A.; Haupt, E.; Wunderlich, K.; Heuschmid, M.; Mertens, T. The UL97 gene product of human cytomegalovirus is an early-late protein with a nuclear localization but is not a nucleoside kinase. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 6340–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littler, E.; Stuart, A.D.; Chee, M.S. Human cytomegalovirus UL97 open reading frame encodes a protein that phosphorylates the antiviral nucleoside analogue ganciclovir. Nature 1992, 358, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webel, R.; Milbradt, J.; Auerochs, S.; Schregel, V.; Held, C.; Nöbauer, K.; Razzazi-Fazeli, E.; Jardin, C.; Wittenberg, T.; Sticht, H.; et al. Two isoforms of the protein kinase pUL97 of human cytomegalovirus are differentially regulated in their nuclear translocation. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Märtson, A.G.; Touw, D.; Damman, K.; Bakker, M.; Oude Lansink-Hartgring, A.; van der Werf, T.; Knoester, M.; Alffenaar, J.C. Ganciclovir Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: A Case Series. Ther. Drug Monit. 2019, 41, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marty, F.M.; Boeckh, M. Maribavir and human cytomegalovirus-what happened in the clinical trials and why might the drug have failed? Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snydman, D.R. Why did maribavir fail in stem-cell transplants? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, W.; Chou, C.; Li, H.; Hai, R.; Patterson, D.; Stolc, V.; Zhu, H.; Liu, F. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 14223–14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanicolaou, G.A.; Silveira, F.P.; Langston, A.A.; Pereira, M.R.; Avery, R.K.; Uknis, M.; Wijatyk, A.; Wu, J.; Boeckh, M.; Marty, F.M.; et al. Maribavir for Refractory or Resistant Cytomegalovirus Infections in Hematopoietic-cell or Solid-organ Transplant Recipients: A Randomized, Dose-ranging, Double-blind, Phase 2 Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 68, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla-Vázquez, S.; Steingruber, M.; Marschall, M.; Engel, F.B. Human cytomegaloviral multifunctional protein kinase pUL97 impairs zebrafish embryonic development and increases mortality. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reim, N.I.; Kamil, J.P.; Wang, D.; Lin, A.; Sharma, M.; Ericsson, M.; Pesola, J.M.; Golan, D.E.; Coen, D.M. Inactivation of retinoblastoma protein does not overcome the requirement for human cytomegalovirus UL97 in lamina disruption and nuclear egress. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 5019–5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marschall, M.; Marzi, A.; aus dem Siepen, P.; Jochmann, R.; Kalmer, M.; Auerochs, S.; Lischka, P.; Leis, M.; Stamminger, T. Cellular p32 recruits cytomegalovirus kinase pUL97 to redistribute the nuclear lamina. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 33357–33367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzeh, M.; Honigman, A.; Taraboulos, A.; Rouvinski, A.; Wolf, D.G. Structural changes in human cytomegalovirus cytoplasmic assembly sites in the absence of UL97 kinase activity. Virology 2006, 354, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.; Ercolani, R.J.; Marousek, G.; Bowlin, T.L. Cytomegalovirus UL97 kinase catalytic domain mutations that confer multidrug resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3375–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drew, W.L.; Miner, R.C.; Marousek, G.I.; Chou, S. Maribavir sensitivity of cytomegalovirus isolates resistant to ganciclovir, cidofovir or foscarnet. J. Clin. Virol. 2006, 37, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.L.; Hartline, C.B.; Kushner, N.L.; Harden, E.A.; Bidanset, D.J.; Drach, J.C.; Townsend, L.B.; Underwood, M.R.; Biron, K.K.; Kern, E.R. In vitro activities of benzimidazole D- and L-ribonucleosides against herpesviruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2186–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.; Van Wechel, L.C.; Marousek, G.I. Effect of cell culture conditions on the anticytomegalovirus activity of maribavir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2557–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, L.H.; Peck, R.W.; Yin, Y.; Allanson, J.; Wiggs, R.; Wire, M.B. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic trials of 1263W94, a novel oral anti-human cytomegalovirus agent, in healthy and human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 1334–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, L.; Webel, R.; Wagner, S.; Hamilton, S.T.; Rawlinson, W.D.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. The cyclin-dependent kinase ortholog pUL97 of human cytomegalovirus interacts with cyclins. Viruses 2013, 5, 3213–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, M.; Steingruber, M.; Socher, E.; Müller, R.; Wagner, S.; Kögel, M.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. Functional Relevance of the Interaction between Human Cyclins and the Cytomegalovirus-Encoded CDK-Like Protein Kinase pUL97. Viruses 2021, 13, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graf, L.; Feichtinger, S.; Naing, Z.; Hutterer, C.; Milbradt, J.; Webel, R.; Wagner, S.; Scott, G.M.; Hamilton, S.T.; Rawlinson, W.D.; et al. New insight into the phosphorylation-regulated intranuclear localization of human cytomegalovirus pUL69 mediated by cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and viral CDK orthologue pUL97. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steingruber, M.; Keller, L.; Socher, E.; Ferre, S.; Hesse, A.-M.; Couté, Y.; Hahn, F.; Büscher, N.; Plachter, B.; Sticht, H.; et al. Cyclins B1, T1, and H differ in their molecular mode of interaction with cytomegalovirus protein kinase pUL97. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 6188–6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, M.; Cordsmeier, A.; Wangen, C.; Horn, A.H.C.; Wyler, E.; Ensser, A.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. The Interactive Complex between Cytomegalovirus Kinase vCDK/pUL97 and Host Factors CDK7-Cyclin H Determines Individual Patterns of Transcription in Infected Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greber, B.J.; Remis, J.; Ali, S.; Nogales, E. 2.5 Å-resolution structure of human CDK-activating kinase bound to the clinical inhibitor ICEC0942. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Babayeva, N.D.; Suwa, Y.; Baranovskiy, A.G.; Price, D.H.; Tahirov, T.H. Crystal structure of HIV-1 Tat complexed with human P-TEFb and AFF4. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 1788–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Rechter, S.; Milbradt, J.; Auerochs, S.; Müller, R.; Stamminger, T.; Marschall, M. Cytomegaloviral protein kinase pUL97 interacts with the nuclear mRNA export factor pUL69 to modulate its intranuclear localization and activity. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonntag, E.; Milbradt, J.; Svrlanska, A.; Strojan, H.; Häge, S.; Kraut, A.; Hesse, A.-M.; Amin, B.; Sonnewald, U.; Couté, Y.; et al. Protein kinases responsible for the phosphorylation of the nuclear egress core complex of human cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2569–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kicuntod, J.; Häge, S.; Hahn, F.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. The Oligomeric Assemblies of Cytomegalovirus Core Nuclear Egress Proteins Are Associated with Host Kinases and Show Sensitivity to Antiviral Kinase Inhibitors. Viruses 2022, 14, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.C.; Krosky, P.M.; Pearson, A.; Coen, D.M. Phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells and in vitro by the viral UL97 protein kinase. Virology 2004, 324, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Businger, R.; Deutschmann, J.; Gruska, I.; Milbradt, J.; Wiebusch, L.; Gramberg, T.; Schindler, M. Human cytomegalovirus overcomes SAMHD1 restriction in macrophages via pUL97. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 2260–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Kato, K.; Tanaka, M.; Kanamori, M.; Nishiyama, Y.; Yamanashi, Y. Conserved protein kinases encoded by herpesviruses and cellular protein kinase cdc2 target the same phosphorylation site in eukaryotic elongation factor 1delta. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 2359–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romaker, D.; Schregel, V.; Maurer, K.; Auerochs, S.; Marzi, A.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. Analysis of the structure-activity relationship of four herpesviral UL97 subfamily protein kinases reveals partial but not full functional conservation. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 7044–7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, H.C.; Huang, W.R.; Liao, T.L.; Chi, P.I.; Nielsen, B.L.; Liu, J.H.; Liu, H.J. Mechanistic insights into avian reovirus p17-modulated suppression of cell cycle CDK-cyclin complexes and enhancement of p53 and cyclin H interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 12542–12562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.P.; Huang, Y.H.; Lin, S.F.; Chang, Y.; Chang, Y.H.; Takada, K.; Chen, M.R. Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 kinase induces disassembly of the nuclear lamina to facilitate virion production. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11913–11926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couté, Y.; Kraut, A.; Zimmermann, C.; Büscher, N.; Hesse, A.M.; Bruley, C.; De Andrea, M.; Wangen, C.; Hahn, F.; Marschall, M.; et al. Mass Spectrometry-Based Characterization of the Virion Proteome, Phosphoproteome, and Associated Kinase Activity of Human Cytomegalovirus. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwahori, S.; Hakki, M.; Chou, S.; Kalejta, R.F. Molecular Determinants for the Inactivation of the Retinoblastoma Tumor Suppressor by the Viral Cyclin-dependent Kinase UL97. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 19666–19680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwahori, S.; Umaña, A.C.; VanDeusen, H.R.; Kalejta, R.F. Human cytomegalovirus-encoded viral cyclin-dependent kinase (v-CDK) UL97 phosphorylates and inactivates the retinoblastoma protein-related p107 and p130 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 6583–6599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwahori, S.; Kalejta, R.F. Phosphorylation of transcriptional regulators in the retinoblastoma protein pathway by UL97, the viral cyclin-dependent kinase encoded by human cytomegalovirus. Virology 2017, 512, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamirally, S.; Kamil, J.P.; Ndassa-Colday, Y.M.; Lin, A.J.; Jahng, W.J.; Baek, M.C.; Noton, S.; Silva, L.A.; Simpson-Holley, M.; Knipe, D.M.; et al. Viral mimicry of Cdc2/cyclin-dependent kinase 1 mediates disruption of nuclear lamina during human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbradt, J.; Hutterer, C.; Bahsi, H.; Wagner, S.; Sonntag, E.; Horn, A.H.; Kaufer, B.B.; Mori, Y.; Sticht, H.; Fossen, T. The prolyl isomerase Pin1 promotes the herpesvirus-induced phosphorylation-dependent disassembly of the nuclear lamina required for nucleocytoplasmic egress. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Oste, V.; Gatti, D.; Gugliesi, F.; De Andrea, M.; Bawadekar, M.; Lo Cigno, I.; Biolatti, M.; Vallino, M.; Marschall, M.; Gariglio, M.; et al. Innate nuclear sensor IFI16 translocates into the cytoplasm during the early stage of in vitro human cytomegalovirus infection and is entrapped in the egressing virions during the late stage. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 6970–6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbradt, J.; Webel, R.; Auerochs, S.; Sticht, H.; Marschall, M. Novel mode of phosphorylation-triggered reorganization of the nuclear lamina during nuclear egress of human cytomegalovirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 13979–13989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, K.P.; Zhou, X.Z. The prolyl isomerase PIN1: A pivotal new twist in phosphorylation signalling and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, M.; Thomas, M.; Wangen, C.; Wagner, S.; Rauschert, L.; Errerd, T.; Kießling, M.; Sticht, H.; Milbradt, J.; Marschall, M. The peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase Pin1 interacts with three early regulatory proteins of human cytomegalovirus. Virus Res. 2020, 285, 198023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Müller, R.; Horn, G.; Bogdanow, B.; Imami, K.; Milbradt, J.; Steingruber, M.; Marschall, M.; Schilling, E.-M.; Fossen, T. Phosphosite analysis of the cytomegaloviral mRNA export factor pUL69 reveals serines with critical importance for recruitment of cellular proteins Pin1 and UAP56/URH49. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e02151-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, Y.; Murata, T.; Ryo, A.; Kawashima, D.; Sugimoto, A.; Kanda, T.; Kimura, H.; Tsurumi, T. Pin1 interacts with the Epstein-Barr virus DNA polymerase catalytic subunit and regulates viral DNA replication. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 2120–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guito, J.; Gavina, A.; Palmeri, D.; Lukac, D.M. The cellular peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase Pin1 regulates reactivation of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus from latency. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.-J.; Ryo, A.; Yamamoto, N. The prolyl isomerase Pin1 stabilizes the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) Tax oncoprotein and promotes malignant transformation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 381, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.-S.; Tran, H.T.; Park, S.-J.; Yim, S.-A.; Hwang, S.B. Peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1 is a cellular factor required for hepatitis C virus propagation. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 8777–8788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Kim, J.; Song, C.; Sajjad, M.A.; Ha, J.; Jung, J.; Park, S.; Shin, H.-J.; Kim, K. Peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase Pin1 interacts with hepatitis B virus core particle, but not with HBc protein, to promote HBV replication. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1195063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, R.; Lee, T.K.; Poon, R.T.; Fan, S.T.; Wong, K.B.; Kwong, Y.L.; Tse, E. Pin1 interacts with a specific serine-proline motif of hepatitis B virus X-protein to enhance hepatocarcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1088–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ino, Y.; Nishi, M.; Yamaoka, Y.; Miyakawa, K.; Jeremiah, S.S.; Osada, M.; Kimura, Y.; Ryo, A. Phosphopeptide enrichment using Phos-tag technology reveals functional phosphorylation of the nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2. J. Proteom. 2022, 255, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misumi, S.; Inoue, M.; Dochi, T.; Kishimoto, N.; Hasegawa, N.; Takamune, N.; Shoji, S. Uncoating of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 requires prolyl isomerase Pin1. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 25185–25195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dochi, T.; Nakano, T.; Inoue, M.; Takamune, N.; Shoji, S.; Sano, K.; Misumi, S. Phosphorylation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid protein at serine 16, required for peptidyl-prolyl isomerase-dependent uncoating, is mediated by virion-incorporated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manganaro, L.; Lusic, M.; Gutierrez, M.I.; Cereseto, A.; Del Sal, G.; Giacca, M. Concerted action of cellular JNK and Pin1 restricts HIV-1 genome integration to activated CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, M.; Müller, R.; Socher, E.; Wangen, C.; Full, F.; Wyler, E.; Wong, D.; Scherer, M.; Stamminger, T.; Chou, S.; et al. Highly Conserved Interaction Profiles between Clinically Relevant Mutants of the Cytomegalovirus CDK-like Kinase pUL97 and Human Cyclins: Functional Significance of Cyclin H. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, M.; Karner, D.; Eickhoff, J.; Wagner, S.; Kicuntod, J.; Chang, W.; Barry, P.; Jonjić, S.; Lenac Roviš, T.; Marschall, M. Combined Treatment with Host-Directed and Anticytomegaloviral Kinase Inhibitors: Mechanisms, Synergisms and Drug Resistance Barriers. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutterer, C.; Eickhoff, J.; Milbradt, J.; Korn, K.; Zeitträger, I.; Bahsi, H.; Wagner, S.; Zischinsky, G.; Wolf, A.; Degenhart, C. A novel CDK7 inhibitor of the Pyrazolotriazine class exerts broad-spectrum antiviral activity at nanomolar concentrations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 2062–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, M.; Hahn, F.; Brückner, N.; Schütz, M.; Wangen, C.; Wagner, S.; Sommerer, M.; Strobl, S.; Marschall, M. Cyclin-Dependent Kinases (CDKs) and the Human Cytomegalovirus-Encoded CDK Ortholog pUL97 Represent Highly Attractive Targets for Synergistic Drug Combinations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahnamiri, M.M.; Roller, R.J. Distinct roles of viral US3 and UL13 protein kinases in herpes virus simplex type 1 (HSV-1) nuclear egress. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, H.E.; Saffran, H.A.; Wu, F.W.; Quach, K.; Smiley, J.R. Herpes simplex virus protein kinases US3 and UL13 modulate VP11/12 phosphorylation, virion packaging, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling activity. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 7379–7388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, L.; Thiry, M.; Bontems, S.; Joris, A.; Piette, J.; Lebrun, M.; Sadzot-Delvaux, C. ORF9p phosphorylation by ORF47p is crucial for the formation and egress of varicella-zoster virus viral particles. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 2868–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- François, S.; Sen, N.; Mitton, B.; Xiao, X.; Sakamoto, K.M.; Arvin, A. Varicella-zoster virus activates CREB, and inhibition of the pCREB-p300/CBP interaction inhibits viral replication in vitro and skin pathogenesis in vivo. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 8686–8697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marschall, M.; Stein-Gerlach, M.; Freitag, M.; Kupfer, R.; van den Bogaard, M.; Stamminger, T. Direct targeting of human cytomegalovirus protein kinase pUL97 by kinase inhibitors is a novel principle for antiviral therapy. J. Gen. Virol. 2002, 83, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lv, D.-W.; Li, R. Conserved herpesvirus protein kinases target SAMHD1 to facilitate virus replication. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 449–459.e445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-H.; Lee, C.-P.; Su, M.-T.; Wang, J.-T.; Chen, J.-Y.; Lin, S.-F.; Tsai, C.-H.; Hsieh, M.-J.; Takada, K.; Chen, M.-R. Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 kinase retards cellular S-phase progression and induces chromosomal abnormality. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, T.; Van den Broeke, C.; Favoreel, H.W. Viral serine/threonine protein kinases. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 1158–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.; Ercolani, R.J.; Derakhchan, K. Antiviral activity of maribavir in combination with other drugs active against human cytomegalovirus. Antiviral. Res. 2018, 157, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Beardsley, G.P.; Coen, D.M. Mechanism of ganciclovir-induced chain termination revealed by resistant viral polymerase mutants with reduced exonuclease activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 17462–17467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, V.R.; Smee, D.F.; Chernow, M.; Boehme, R.; Matthews, T.R. Activity of 9-(1,3-dihydroxy-2-propoxymethyl)guanine compared with that of acyclovir against human, monkey, and rodent cytomegaloviruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1985, 28, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, E.-C.; Chiou, J.-F.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Huang, E.-S. Inhibition of cellular DNA polymerase alpha and human cytomegalovirus-induced DNA polymerase by the triphosphates of 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl) guanine and 9-(1, 3-dihydroxy-2-propoxymethyl) guanine. J. Virol. 1985, 53, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, J.R.; Baltz, J.K. Foscarnet sodium. Dicp 1991, 25, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crumpacker, C.S. Mechanism of action of foscarnet against viral polymerases. Am. J. Med. 1992, 92, S3–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S. Letermovir: First global approval. Drugs 2018, 78, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Helou, G.; Razonable, R.R. Letermovir for the prevention of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients: An evidence-based review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 1481–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lischka, P.; Hewlett, G.; Wunberg, T.; Baumeister, J.; Paulsen, D.; Goldner, T.; Ruebsamen-Schaeff, H.; Zimmermann, H. In vitro and in vivo activities of the novel anticytomegalovirus compound AIC246. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, M.; Kicuntod, J.; Seyler, L.; Wangen, C.; Bertzbach, L.D.; Conradie, A.M.; Kaufer, B.B.; Wagner, S.; Michel, D.; Eickhoff, J.; et al. Combinatorial Drug Treatments Reveal Promising Anticytomegaloviral Profiles for Clinically Relevant Pharmaceutical Kinase Inhibitors (PKIs). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, E.; Hahn, F.; Bertzbach, L.D.; Seyler, L.; Wangen, C.; Müller, R.; Tannig, P.; Grau, B.; Baumann, M.; Zent, E.; et al. In vivo proof-of-concept for two experimental antiviral drugs, both directed to cellular targets, using a murine cytomegalovirus model. Antiviral. Res. 2019, 161, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenovsek, K.; Weisel, F.; Schneider, A.; Appelt, U.; Jonjic, S.; Messerle, M.; Bradel-Tretheway, B.; Winkler, T.H.; Mach, M. Protection from CMV infection in immunodeficient hosts by adoptive transfer of memory B cells. Blood 2007, 110, 3472–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, M.N.; Shipman, C., Jr. A three-dimensional model to analyze drug-drug interactions. Antiviral. Res. 1990, 14, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.C.; Talalay, P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: The combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzym. Regul. 1984, 22, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.C. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 621–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutterer, C.; Hamilton, S.; Steingruber, M.; Zeitträger, I.; Bahsi, H.; Thuma, N.; Naing, Z.; Örfi, Z.; Örfi, L.; Socher, E.; et al. The chemical class of quinazoline compounds provides a core structure for the design of anticytomegaloviral kinase inhibitors. Antiviral. Res. 2016, 134, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.; Marousek, G.I. Accelerated evolution of maribavir resistance in a cytomegalovirus exonuclease domain II mutant. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.; Wu, J.; Song, K.; Bo, T. Novel UL97 drug resistance mutations identified at baseline in a clinical trial of maribavir for resistant or refractory cytomegalovirus infection. Antiviral. Res. 2019, 172, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushing, V.I.; Koh, A.F.; Feng, J.; Jurgaityte, K.; Bondke, A.; Kroll, S.H.B.; Barbazanges, M.; Scheiper, B.; Bahl, A.K.; Barrett, A.G.M.; et al. High-resolution cryo-EM of the human CDK-activating kinase for structure-based drug design. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, M.; Caing-Carlsson, R.; Houssari, R.; Javadi, A.; Kimbung, Y.R.; Murina, V.; Orozco-Rodriguez, J.M.; Svensson, A.; Welin, M.; Logan, D.; et al. Crystal structure of the human CDK7 kinase domain in complex with LDC4297. PDB Entry 2023, 5, 4–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, M.; Wangen, C.; Sommerer, M.; Kögler, M.; Eickhoff, J.; Degenhart, C.; Klebl, B.; Naing, Z.; Egilmezer, E.; Hamilton, S.T.; et al. Cytomegalovirus cyclin-dependent kinase ortholog vCDK/pUL97 undergoes regulatory interaction with human cyclin H and CDK7 to codetermine viral replication efficiency. Virus Res. 2023, 335, 199200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Target | EC50 (µM) a | CC50 (µM) b | SI c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| abemaciclib | CDK4/6 | 6.43 ± 3.77 | 15.54 ± 5.78 | 2.42 |

| AZD4573 d | CDK9 | - | 0.35 ± 0.09 | - |

| CDK2 Inh II | CDK2 | 5.17 ± 1.25 | >100 | 19.34 |

| CVT-313 d | CDK2 | - | 5.57 ± 0.05 | - |

| CYC065 d | CDK2/9 | - | <0.1 | - |

| Dinaciclib d | CDK1/2/5/9 | - | <0.1 | - |

| LDC4297 | CDK7 | 0.0082 ± 0.0015 | >1 | 121.95 |

| Riviciclib d | CDK1/4/9 | - | 1.64 ± 0.06 | - |

| Samuraciclib d | CDK7 | - | 0.50 ± 0.21 | - |

| SEL120 | CDK8 | 0.067 ± 0.027 | 5.90 ± 3.85 | 88.06 |

| SY1365 d | CDK7 | - | <0.1 | - |

| THAL-SNS032 | CDK9 | 0.024 ± 0.0026 | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 5.83 |

| Compound Combination | 95% Confidence Interval Synergy Volume (µM2%) b | Interaction Type c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Sum | ||

| MBV + GCV | 0.0 | −397.9 | −397.9 | antagonistic |

| abemaciclib + GCV | 4.6 | −76.5 | −71.9 | antagonistic |

| abemaciclib + LDC4297 | 389.8 | −4.5 | 385.3 | strongly synergistic |

| abemaciclib + MBV | 0.1 | −67.7 | −67.6 | antagonistic |

| TF27 + GCV | 20.4 | −19.7 | 0.7 | additive |

| TF27 + LDC4297 | 10.0 | −6.7 | 3.3 | additive |

| TF27 + LMV | 61.1 | −22.3 | 38.8 | additive |

| MBV + LDC4297 | 138.6 | −1.6 | 137.0 | strongly synergistic |

| CDK2 Inh II + MBV | 394.3 | −12.3 | 382 | strongly synergistic |

| SEL120 + LDC4297 | 217.0 | −0.0 | 217 | strongly synergistic |

| THAL-SNS032 + SEL120 | 148.4 | −2.0 | 146.4 | strongly synergistic |

| CDK2 Inh II + LDC4297 | 0.0 | −251.3 | −251.3 | antagonistic |

| Compound Combination | Ratio | Replicates a | CIwt b | Interaction Type c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBV + GCV | 1:1 | 3 | 2.88 ± 0.83 | antagonistic |

| abemaciclib + LDC4297 | 100:1 | 2 | 1.03 ± 0.11 | additive |

| abemaciclib + MBV | 100:1 | 1 | 1.21 | moderately antagonistic |

| abemaciclib + GCV | 1:1 | 3 | 0.59 ± 0.08 | synergistic |

| GCV + LDC4297 | 100:1 | 3 | 0.66 ± 0.19 | synergistic |

| MBV + CDK2 Inh II | 1:1 | 2 | 0.20 ± 0.13 | strongly synergistic |

| MBV + LDC4297 | 50:1 | 2 | 0.48 ± 0.35 | synergistic |

| MBV + LDC4297 | 100:1 | 2 | 0.48 ± 0.15 | synergistic |

| SEL120 + CDV | 1:1 | 1 | 0.31 | synergistic |

| SEL120 + GCV | 1:10 | 2 | 0.34 ± 0.07 | synergistic |

| SEL120 + LDC4297 | 10:1 | 3 | 0.55 ± 0.06 | synergistic |

| SEL120 + LMV | 1:100 | 2 | 0.75 ± 0.05 | moderately synergistic |

| SEL120 + THAL-SNS032 | 50:1 | 3 | 0.66 ± 0.10 | synergistic |

| TF27 + GCV | 1:100 | 2 | 1.37 ± 0.28 | moderately antagonistic |

| THAL-SNS032 + LDC4297 | 1:1 | 3 | 0.62 ± 0.14 | synergistic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marschall, M.; Schütz, M.; Wild, M.; Socher, E.; Wangen, C.; Dhotre, K.; Rawlinson, W.D.; Sticht, H. Understanding the Cytomegalovirus Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Ortholog pUL97 as a Multifaceted Regulator and an Antiviral Drug Target. Cells 2024, 13, 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13161338

Marschall M, Schütz M, Wild M, Socher E, Wangen C, Dhotre K, Rawlinson WD, Sticht H. Understanding the Cytomegalovirus Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Ortholog pUL97 as a Multifaceted Regulator and an Antiviral Drug Target. Cells. 2024; 13(16):1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13161338

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarschall, Manfred, Martin Schütz, Markus Wild, Eileen Socher, Christina Wangen, Kishore Dhotre, William D. Rawlinson, and Heinrich Sticht. 2024. "Understanding the Cytomegalovirus Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Ortholog pUL97 as a Multifaceted Regulator and an Antiviral Drug Target" Cells 13, no. 16: 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13161338

APA StyleMarschall, M., Schütz, M., Wild, M., Socher, E., Wangen, C., Dhotre, K., Rawlinson, W. D., & Sticht, H. (2024). Understanding the Cytomegalovirus Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Ortholog pUL97 as a Multifaceted Regulator and an Antiviral Drug Target. Cells, 13(16), 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13161338