Abstract

Pulmonary bacterial infections present a significant health risk to those with chronic respiratory diseases (CRDs) including cystic fibrosis (CF) and chronic-obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). With the emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), novel therapeutics are desperately needed to combat the emergence of resistant superbugs. Phage therapy is one possible alternative or adjunct to current antibiotics with activity against antimicrobial-resistant pathogens. How phages are administered will depend on the site of infection. For respiratory infections, a number of factors must be considered to deliver active phages to sites deep within the lung. The inhalation of phages via nebulization is a promising method of delivery to distal lung sites; however, it has been shown to result in a loss of phage viability. Although preliminary studies have assessed the use of nebulization for phage therapy both in vitro and in vivo, the factors that determine phage stability during nebulized delivery have yet to be characterized. This review summarizes current findings on the formulation and stability of liquid phage formulations designed for nebulization, providing insights to maximize phage stability and bactericidal activity via this delivery method.

1. Introduction

Pulmonary infections are one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1], severely impacting individuals with chronic respiratory diseases (CRDs) such as cystic fibrosis (CF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Individuals with CRDs are prone to persistent infections with opportunistic pathogens leading to extensive inflammation and lung damage [2,3,4,5,6]. One of the most important bacteria implicated in these infections is Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which is a gram-negative pathogen associated with a suite of negative health impacts for individuals with CRDs [7,8]. In individuals with CF, infection with P. aeruginosa results in increased airway inflammation and mortality as well as an increase in lung function decline [5,6,9,10]. Within those with COPD and non-CF bronchiectasis, up to one-third of individuals may be colonized by P. aeruginosa, with infection being linked to an increase in lung function decline and mortality [11,12,13].

Like other bacterial pathogens, P. aeruginosa is capable of accumulating antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to multiple classes of antibiotics, becoming multi-drug resistant (MDR). P. aeruginosa is also capable of forming biofilms, further reducing antibiotic efficacy and contributing to recalcitrant and recurring infections [14,15]. The impact of respiratory antimicrobial-resistant infections is increasing globally, with lower respiratory infections accounting for over 1.5 million deaths [16]. For those with CRDs, pulmonary infection with antibiotic-resistant bacteria has been further linked to an increase in disease severity and mortality [9,17,18]. Antimicrobial-resistant infections can be exceedingly difficult and costly to treat, especially in individuals with CRDs who are persistently infected [7]. Currently, intravenous (IV) and aerosolized antibiotics are used to treat pulmonary bacterial infections including those caused by P. aeruginosa; however, as bacteria are becoming increasingly antimicrobial-resistant, the effectiveness of these antibiotics is diminishing [19,20]. With little investment in the discovery and development of antibiotic compounds, there is an urgent need for novel antimicrobials [21]. This is where pulmonary phage therapy may serve as a promising alternative or complementary therapy to treat antimicrobial-resistant infections in the lungs. The method of delivery for therapeutic phages can vary depending on the site of infection. Skin infections can be treated with a topical ointment containing phage [22], but the delivery of phages to deeper sites of infection such as the lungs is more challenging. While intravenous phage delivery has been used previously to treat respiratory infections, the inhalation of phage allows for the direct delivery of the phage to sites of respiratory infection, and has been proposed to be a more promising method of delivery [23].

The aerosolization of phage through nebulization and dry powder inhalers has so far shown promising success; however, many factors within the delivery process remain poorly understood. The elucidation of these factors will allow for the optimization of aerosolized phage therapy, ensuring its success as a therapeutic in the future.

2. Phage Therapy to Treat Antimicrobial Resistance

Bacteriophages or phages are viruses that solely infect and replicate within bacterial cells. They are among the most abundant biological entities on the planet and are ubiquitous in the environment, with an estimated 1031 phage particles in the biosphere [24]. They were first discovered in the 1910s independently by Frederick Twort and Felix d’Herelle, with early studies in humans indicating their effectiveness for treating bacterial infections [25,26,27,28]. The discovery of penicillin by Fleming in 1928, coupled with the lack of widespread resistance to antibiotics at the time, led to phage therapy being overlooked in Western countries as antibiotic drugs were further developed [29]. However, phage therapy has seen continued use in some Eastern European countries [29,30,31].

With the emergence of AMR, phage therapy has seen a resurging interest as a possible solution [32]. Phage therapy implements shorter treatment periods than antibiotics and has shown effectiveness against pathogens that are antibiotic resistant [33,34]. A systematic review by Liu et al. on the safety of phage therapy found that serious adverse events directly associated with phage therapy were extremely rare [35]. In contrast, the higher doses of antibiotics currently required to treat MDR infections may result in significant side effects, including the development of drug allergies as well as high levels of ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity [36,37,38].

Phages can exhibit a lysogenic life cycle, where they integrate into the host genome and can alter the phenotype of bacteria [39,40]. For a phage to be considered therapeutically useful, it must have a strictly lytic life cycle, where the phage first infects and replicates within a bacterial cell, which is followed by lysis of the bacteria and the release of infectious phage particles [41,42,43]. Due to the specificity of phage for their target bacteria, phage therapy allows for there to be no adverse effect on normal flora when compared to high-dose, broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment [44]. However, this specificity may also require phages to be screened against individual bacterial species to ensure they can lyse patient bacterial isolates. Phage therapy often involves the use of multiple phages with a broad host range against isolates within a bacterial species [45]. These phages are used together in a formulation termed a ‘phage cocktail’ that can be used to overcome potential bacterial phage-resistance mechanisms [45,46]. Most contemporary instances of phage therapy have been approved on the basis of compassionate use and have shown encouraging success in humans [47,48,49].

3. Phage Delivery for Respiratory Infections

3.1. Intravenous Delivery

Intravenous delivery is the phage delivery method most commonly used for respiratory infections in humans. Early trials of phage therapy, as well as more recent case reports, have shown IV phages to be effective for respiratory infections [27,50]. However, the IV delivery of phages has been suggested to stimulate both the innate and adaptive immune systems, leading to a reduction in phage titer [51,52,53,54]. Sokoloff and colleagues suggested that as the bloodstream is not a natural environment for phages, the peptides contained on the phage surfaces are recognized by antibodies, leading to complement activation and clearance from the body [54]. Notably, the application of phages topically to the skin or to mucosal surfaces such as the oral cavity has not been shown to result in an immunological response [55,56,57].

3.2. Aerosolized Delivery

Sites of infection in the lungs are not easily accessed and as such, the systemic administration of phages or antibiotics may fail to deliver a sufficient quantity to the lungs to clear an infection. In these scenarios, direct inhalation appears to be a more promising method, which can be achieved via the inhalation of a nebulized liquid or a dry powder. Aerosolized medication requires the formation of small particles capable of penetrating deep into the lung, below 5 µm in diameter [58]. Antibiotics have been delivered via aerosolization since the 1940s, and this has been shown to result in a higher concentration of drug in the lungs compared to systemic administration [59,60]. The inhalation of antibiotics including tobramycin is common for those with CRDs such as CF, particularly for treating infections with P. aeruginosa [61,62]. Similarly, the inhalation of phages through various methods of aerosolization seems to be a promising method for phage delivery directly to sites of infection in the lung [23]. Unlike antibiotic compounds, phages are biological entities that may be sheared and inactivated by the mechanical stresses of aerosolized delivery methods, and they must remain intact and functional after delivery in order to exert a bactericidal effect [63]. Perhaps the most important concern for phage aerosolization is the loss of phage viability through the mechanical destruction of virions during the delivery process, which is a challenge that has been observed for all forms of aerosolization [64,65,66,67,68]. In separate studies, Carrigy et al. and Astudillo et al. assessed three types of nebulization and observed a reduction in phage titer in all cases [64,65]. Additionally, various studies have observed phage titer loss in the production of inhalable dry powders [66,67,68].

3.2.1. Nebulization

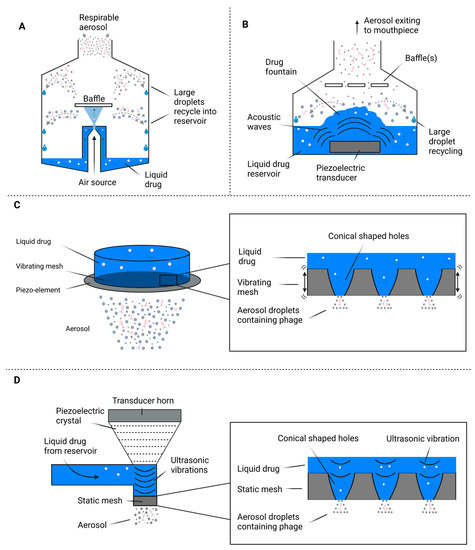

Nebulization involves the process of converting a liquid solution into a fine aerosol. It is considered the optimal method for the pulmonary delivery of drugs due to its ability to deliver large volumes easily and in particle sizes capable of depositing in lower airways [69,70]. There are various types of commercial nebulizers available that have been tested with phage preparations, including jet nebulizers, vibrating or static mesh, and ultrasonic nebulizers. The general principle of phage delivery with these nebulizer types is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Devices used for liquid aerosolization of phages. Diagrams represent the general principle of phage delivery using: (A) Compression/jet nebulization, (B) Ultrasonic nebulization, (C) Vibrating mesh nebulization, (D) Static mesh nebulization.

Jet nebulization (Figure 1A) involves a compressed gas forced through tubing to create a zone of low pressure around a nozzle. This zone of low pressure causes liquid to rise from the reservoir, creating primary and secondary droplets [71,72]. Large primary droplets may impact on the walls of the nebulizer or on the primary baffle and are recycled into the reservoir, whereas smaller droplets that avoid this recycling process form the respirable portion of generated aerosol [71,73]. Ultrasonic nebulizers (Figure 1B) generate an aerosol via the oscillation of a piezoelectric crystal at high frequencies to generate and transfer acoustic energy waves to a liquid solution, leading to aerosol production [74]. A large amount of heat is often produced during ultrasonic nebulization, which may lead to the degradation of organic proteins and phages within the nebulization buffer, and as such, ultrasonic nebulization is not recommended for highly viscous or proteinaceous solutions [74,75]. There are two subclasses of mesh nebulizers: the first is vibrating mesh nebulizers (Figure 1C), which generate an aerosol by the action of a piezoelectric element that vibrates (100–300 kHz) an aperture plate lined with conical-shaped holes [75]. As the mesh vibrates, the liquid drug solution is forced through the holes and ejects as an inhalable aerosol [75,76]. In contrast, static mesh nebulizers (Figure 1D) utilize an ultrasonic transducer in contact with a liquid drug to generate vibrations (150–250 kHz) within the drug, pushing the solution through a static mesh to generate an aerosol [77].

Mesh nebulization has been shown to generally result in a lower reduction in phage titer than other nebulizer types [64,65]; however, the mechanisms behind this are not well characterized. In their study on the anti-tuberculosis phage D29, Carrigy et al. observed a 3.7 log10 titer reduction from jet nebulization as opposed to a 0.4 log10 and 0.6 log10 reduction for vibrating mesh and soft mist inhalation, respectively [65]. Carrigy et al. note that while the flow rate of jet nebulized aerosol exiting the mouthpiece was 0.122 (±0.003) mL/min, the flow rate of aerosol exiting the atomizing nozzle within the device was 17.6 (±8.1) mL/min. This indicates that only a small fraction of the aerosol passing through the nozzle was exiting the device through the mouthpiece. The majority of droplets were too large for inhalation, causing them to impact on the primary baffle and interior surface of the nebulizer and then fall back into the reservoir for re-nebulization (Figure 1A). Using their mathematical model, Carrigy and colleagues discovered that phages were subjected to the stress of impaction on the baffle an average of 96 times before exiting the mouthpiece [65]. Their results were in agreement with values from the literature regarding the Collison jet nebulizer, for which 99.92% of aerosol exiting the nozzle is re-nebulized before exiting the mouthpiece [78]. Although this might appear to account for the higher titer reduction, Carrigy et al. also observed that the first 10.5% of phage exiting the mouthpiece still had a titer reduction of over 3 log10 despite undergoing only 1–17 nebulizer cycles [65]. The study concluded that any degree of impaction onto the primary baffle was resulting in the large reduction in titer. In contrast, other studies have found that some phages are less damaged by jet nebulization compared to vibrating mesh and that nebulizer effects on phage viability are specific to individual phages [69,70,79,80]. Sahota et al. used a cascade impactor to compare the effect of the Omron vibrating mesh nebulizer and the AeroEclipse jet nebulizer on two P. aeruginosa phages [70]. They found that jet nebulization resulted in a 1 log10 reduction in titer, while the vibrating mesh nebulizer caused a reduction of approximately 2 log10 [70]. Additionally, Golshahi et al. noted a similar titer reduction in a Burkholderia cepacia complex phage between the Pari LC star jet nebulizer and the Pari eFlow vibrating mesh nebulizer [69]. Various in vitro and in vivo studies assessing phage viability following nebulization are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies examining phage viability using jet, vibrating and static mesh nebulizers.

The contrasting findings across these studies make it difficult to predict how a phage will be affected by nebulization, and no definitive phage characteristics have been associated with loss of activity. In addition, studies examining aerosolized phage viability may not always assess the same parameters, making their comparison challenging. Leung et al. have suggested that an increase in the length of phage tails is associated with a higher loss of phage; however, another study involving a number of other phages did not reach the same conclusion [81,82]. Both these studies have assessed these characteristics using jet nebulization but not vibrating mesh nebulization. A study by Astudillo et al. used transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to provide visual proof of phage damage from jet and mesh nebulization, and found that a significant portion of phage damage was due to tail detachment, indicating this may be a weak point for phage during mechanical stress [64]. However, phage damage via nebulization has also been observed for phages without tails, and is suspected to be a consequence of nucleic acid ejection from mechanical stresses [64,85].

Despite the challenges of phage nebulization, it remains a promising method of delivering phages directly to sites of infection in the lower airways. In addition, when compared to intravenous administration, it does not lead to high stimulation of the host immune system [52,53,54]. A recent study by Liu and colleagues assessed the use of jet nebulization to deliver phage D29 in a murine model, demonstrating the effectiveness of aerosolized phage for pulmonary delivery [86]. They observed approximately 10% of the aerosolized dose being delivered to the lungs of infected mice compared with <0.1% lung delivery for intraperitoneal injection [86]. Similarly, Semler et al. compared the reduction in bacterial load in the lungs by phage delivered by jet nebulization and intraperitoneal injection in mice [83]. They observed up to a 4 log10 reduction in the bacterial load in the lungs from phages delivered by nebulization as opposed to a 0.5 log10 reduction for phages delivered intraperitoneally [83].

There may be a precedent for some cases of phage therapy to utilize a combination of intravenous and aerosolized delivery, particularly when a lung infection has spread systemically. In a recent study, Prazak et al. assessed the nebulized and intravenous delivery of phages to treat methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) pneumonia in rats [53]. They found that the combination of intravenous and aerosolized delivery led to a more effective eradication of bacteria than either treatment separately. They postulated this was likely due to the inability of inhaled phage to treat MRSA that escaped the lung and spread throughout the body, which was confirmed by the presence of MRSA in the spleen [53].

3.2.2. Dry Powder Inhalers

Phages may also be delivered as a solid preparation generated by a freeze or spray drying process, allowing for ease of transport as well as extended storage capabilities [80,87]. Several studies have shown freeze-drying to be an effective method for stabilizing phage for long-term storage [67,88,89]. Compared to nebulizers, dry powder inhalers (DPIs) are portable and simple to use, and they do not require extensive cleaning and disinfection. During the process of freeze-drying phages, sugars such as sucrose, lactose and trehalose may provide a high level of protection to phages from freezing and drying stresses as well as for long-term storage [67,88]. The levels of log loss associated with powdered phage storage and delivery are similar to those of liquid preparations, and phage powders are capable of retaining their activity over several years in storage with minimal titer loss (<2 log10) [67]. Powder inhalers may cause a reduction in phage viability as the powder is dispersed through both impaction and shear forces, and much like nebulization, these forces are considered phage and formulation dependent [66,68]. Despite this, many studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of inhaled phage powders, and it remains a possible method of phage delivery for respiratory infections [90,91,92].

4. Phage Formulations for Aerosolization

4.1. Stability and Storage

An important consideration for pulmonary delivery is the stability of phage in their pre-delivery formulation, as this may in turn affect phage viability and performance upon aerosolization. Phages exhibit highly variable stability across different formulations including liquid, gels and powders, especially across different phage classes and types [93,94]. Phages often exhibit poor stability in pure water, where direct oxidation can result in capsid and tail degradation, leading to a loss of genetic material [95]. This may complicate the production of therapeutic phage preparations for human use, where ultrapure water may be required in the manufacturing process. For long-term storage, phage preparations are often contained in buffer systems including Tris, salt–magnesium (SM) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [63,96,97]. Cooper et al. assessed the long-term storage stability of three separate liquid phage preparations in PBS over 6 months with no significant loss of infectious titer (≤0.5log) when stored at 4 °C or at room temperature; however, they only tested the storage stability of their cocktail components and not their nebulizer cocktail [63].

The addition of divalent ions such as Mg2+ and Ca2+ into phage buffers may also have a protective effect for the long-term storage of phage by stabilizing the phage tail; however, the effect these ions have during nebulization is not known [96,98]. Phage preparations intended for human use are commonly diluted in 0.9% medical saline before pulmonary delivery [99]. A study by Carrigy et al. assessed the suitability of this method for aerosolization and found minimal effects of saline dilution using a vibrating mesh nebulizer (≈0.5 log10 reduction), whereas a jet nebulizer resulted in a large titer reduction of ≈3.7 log10 PFU/mL [65]. However, the study concluded that the increased reduction was due to the mechanical forces of the jet nebulizer itself rather than the saline dilution step [65]. Conversely, studies by Liu et al. and Verreault et al. found that deionized water was the optimal nebulizer fluid for jet nebulization [100,101]. Both studies postulated the presence of strong ionic charge and salt concentration in both PBS and 0.9% saline were deleterious to phage stability during jet nebulization; however, this has not been extensively tested using vibrating mesh nebulization [100,101]. It is worth noting that the particle size distribution of the aerosols was not altered by the change in buffer [100,101]. If strong ionic content is indeed detrimental to phage nebulization, the addition of ions such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ to stabilize liquid phage preparations, as is commonly performed, may inadvertently result in a loss of activity. Further research is required to understand for which phages ions may be beneficial or deleterious. These findings highlight a potential challenge when creating a pharmaceutical phage preparation, as there is no guarantee a patient will have access to a specific type of nebulizer. Therefore, a pharmaceutical phage preparation may need to be trialed with multiple nebulizer types to ensure it remains therapeutically effective with different nebulizer technologies.

4.2. Organic Additives

Some studies have identified that the presence of proteins or organic fluid in the aerosolization medium results in a protective effect on aerosolized viruses, including phage [85,102]. This has also been reported for nebulized antibody therapy, where the addition of surfactants and increased protein concentrations have been shown to protect antibodies against aggregation and interfacial stresses [103,104]. Turgeon and colleagues directly assessed the addition of organic fluid using five tail-less phages; however, they were only able to test this using one jet nebulizer model (TSI 9302 atomizer) [85]. This was due to their use of amniotic fluid as an organic supplement, which led to clogging during tests of the vibrating mesh nebulizer (Aeroneb Lab) and the second jet nebulizer (Collison 6) [85]. Out of the five tail-less phages tested, the presence of organic fluid resulted in a protective effect for two phages, PR772 and Φ6 [85]. Their results are analogous to those from a previous study by Phillpotts et al. which suggested organic molecules in an aerosolization buffer may enhance the stability of Φ6 [105]. In their study, Phillpotts and colleagues tested the stability of Φ6 in an aerosol following jet nebulization with the Collison nebulizer [105]. The aerosol generated was kept within a rotating steel drum with samples being collected over time. The authors tested spray fluids of LB broth with either 2% skimmed cow’s milk or 2% bovine serum albumin as well as a mammalian cell culture medium Leibovitz L15 supplemented with FCS, HEPES and glutamine [105]. They observed a significantly higher survival for phages using Leibovitz L15 as the spray fluid [105]. This finding has yet to be established for tailed phages, which make up the majority of phages in nature [106]. The use of these bovine components in phage formulations may also not be translatable for clinical studies in humans.

To date, no studies have assessed the use of organic fluid in the nebulization buffer to protect phages with an ultrasonic or mesh nebulizers. Due to the heat produced during ultrasonic nebulization, they are not recommended for viscous solutions and would likely degrade organic proteins and potentially phages in the nebulization buffer [72]. Although mesh nebulization is considered less damaging to phages, their use with organic proteins is questionable [64,107]. With vibrating mesh nebulizers, a small increase in viscosity may lead to an increase in the fine particle fraction (FPF); however, as the viscosity increases beyond a certain limit, aerosol generation may cease entirely for both vibrating mesh and ultrasonic nebulization [107,108]. Therefore, the use of organic fluid to protect phages may only be suitable for jet nebulization, which may be beneficial to counteract the higher loss of phage titer commonly reported with this method. Furthermore, some air-jet nebulizers have shown the capacity to generate aerosols from highly viscous solutions [72,108].

4.3. Dosage

Following preparation, storage, and delivery processes, phages must be delivered in a high enough titer to the site of infection to result in sufficient bacterial clearance. In mice, it is generally accepted that the minimum effective therapeutic dose for phage therapy is 1 × 107 PFU [69]. Although the required dose for effective therapy in humans is not known, many researchers report a phage quantity of approximately 108 PFU is required to maximize bacterial clearance [30,109,110,111]. However, there are currently no consistent delivery and dosing regiments for nebulized phage therapy, and the optimization of the required dosage may depend on multiple factors, including the phage/bacteria ratio and dosing frequency for treatment as well as the type and model of nebulizer used for delivery. In addition, any underlying conditions in a patient may influence the efficacy of phage delivery [112]. As many characteristics of aerosolized phage therapy are yet to be elucidated, the optimal method of delivery of phage for a patient will depend on their individual case. This is further complicated by the highly specific and variable nature of phages to different aerosolized delivery methods [79,80].

5. Aerosolized Phage Therapy in Humans

The use of aerosolized phage therapy has been shown to be a promising method for the treatment of MDR infections in humans [99,113,114]. Human case reports have thus far been primarily limited to compassionate use cases, often involving a combination of inhalation and IV delivery. In the case of a 52-year-old individual with an MDR Acinetobacter baumannii infection, Rao and colleagues assessed IV delivery alone as well as a combination of IV and nebulization [115]. Interestingly, they observed greater clinical improvement with combination therapy when compared with IV delivery alone and noted that nebulization may be a more efficacious method for delivering phages to infection sites in the airways [115]. Lebeaux et al. reported aerosolized phage therapy in a 12-year-old lung-transplanted CF individual with a pandrug-resistant Achromobacter xylosoxidans lung infection [113]. In this case, complete clearance of the pathogen was only observed almost two years after phage therapy ceased. It is uncertain whether the patient’s condition would have improved without phage therapy; however, the authors noted that multiple rounds of antibiotic treatment and oxygen therapy did not result in any lung function improvement [113]. After two rounds of phage therapy, the patient’s respiratory condition slowly improved across the two-year period until bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cultures were negative for A. xylosoxidans [113].

It can be difficult to determine the exact clinical efficacy of aerosolized phages with respect to bacterial clearance, as the primary outcome for compassionate use cases is generally a swift clinical improvement and the reduction in pathogen load is not always quantitatively measured. However, in a recent case report of nebulized phage therapy by Köhler et al., sputum samples collected 8 h post-nebulization showed a maximum of 5 log10 PFU despite delivery of over 9 log10 phage [116]. Although the authors do not mention the type of nebulizer used, this indicates the reduction in phage titer commonly observed following aerosolized delivery. Despite this, the authors suggested that the increase in phage number alongside a reduction in bacterial load indicated that inpatient phage replication following inhalation had occurred [116]. Table 2 presents various case studies of phage therapy in humans using nebulization. The major outcomes of these case reports indicate that aerosolized phage delivery generally results in a significant clinical improvement for patients with the potential to result in a complete eradication of MDR respiratory pathogens.

Table 2.

Overview of various case studies utilizing aerosolized phage delivery.

6. Considerations for Future Development of Aerosolized Phage Therapy

The primary aim of aerosolized phage therapy is to ensure the delivery of an efficacious dose of viable phages to a site of respiratory infection. The various mechanisms in which the titer or number of viable phages may be reduced during the formation and delivery of aerosolized phages are presented in Figure 2. Damage to phages during manufacture and storage may result in an unacceptable level of titer reduction before delivery (Figure 2A). The optimization of phage stability in storage through the addition of stabilizing additives and adjuvants will ensure there is no significant loss of titer before aerosolization. The titer reduction caused by mechanical stresses during nebulization presents an additional challenge (Figure 2B), with the factors mediating phage susceptibility to degradation still poorly understood. Aerosolized phage therapy also suffers from similar limitations affecting the inhalation of other medications, one of the most prominent being the loss of medication through deposition in the upper airways (Figure 2C). Subsequently, only a fraction of an inhaled dose of medication will end up depositing at a site of infection in the lower respiratory tract [118,119]. Following inhalation and deposition, phages may also be removed from the body by the host immune system or through mucociliary clearance (Figure 2D) [120]. Unfortunately, the precise numbers of phage that are lost through these mechanisms during delivery in humans are not known; however, the high levels of variability across all aspects of aerosolized delivery may make this information difficult to establish. The various ways in which the number of viable phages may be reduced highlight the need to minimize titer loss in the early stages of delivery (formulation and aerosolization) to ensure high bactericidal activity for phages depositing at sites in the lower airways.

Figure 2.

Timeline of aerosolized phage delivery to sites in the lower respiratory tract. Various points (A–D) along the timeline of aerosolized phage delivery highlight where phage volume and/or titer may be reduced; (A): Titer reduction due to instability during storage. (B): Mechanical stress destroys phage particles during nebulization. (C): Secondary deposition in the upper respiratory tract and in extra-thoracic regions. (D): In vivo phage clearance by the host, e.g., anti-phage immune response and mucociliary clearance. Y-axis is a demonstrative hypothetical representation of titer loss during aerosolization.

One of the barriers for the optimization of aerosolized phage delivery is a lack of standardized reporting of study details. Some studies do not report genomic and morphological characteristics of their aerosolized phages. The omission of this data makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions across different studies, and with no known phage characteristic(s) currently linked to stability in aerosols, details on the phage types used in these experiments may be crucial to understanding which phages are best suited for aerosolization [79,80]. To aid in this, aerosolized phage studies should report the phage family as well as any genomic and morphological characteristics of phages used for experiments or treatment. This will facilitate dedicated studies of phages and their morphology to further elucidate potential links between phage types and aerosolization stability.

As the components of a liquid formulation will affect its capacity to be aerosolized, phage formulation ingredients must also be well reported [85,121,122]. Additionally, components of the aerosolization medium may influence phage stability during both storage and delivery [65,85,96]. Therefore, it is vital that studies examining aerosolized phage note the components of any buffers and aerosolization media used during manufacturing, storage, and delivery processes. Future studies systematically testing different stabilizing additives or compounds are warranted for the identification of components that protect phages from damage during nebulization.

Owing to the fact that different types of nebulization have been shown to have varying effects on phages, the reporting of the parameters during nebulization must be thorough [64,65]. Some studies omit the model of nebulizer used or even the type of nebulization used for delivery. Additionally, studies do not always report the nebulization parameters, such as operating frequencies, airflow rates and subsequent particle sizes and aerosol output. These factors may vary between different models and brands within each nebulizer type and affect phage viability differently. As there are currently no phage characteristics associated with titer loss following nebulization, the reporting of these nebulizer specifications may be crucial to understanding how phages are affected by different devices and operating parameters.

7. Conclusions

The aerosolization of phage in either solid or liquid formulations appears to be a promising method for delivery to sites of infection in the lower airways. All methods of aerosolization have been shown to result in a loss of infectious phage titer in addition to reduction as a part of manufacturing and storage processes. Studies have suggested that titer loss is phage specific, and little to no phage or formulation-specific characteristics have been associated with loss of titer following aerosolization. This remains a major hindrance to full clinical translation of inhaled phage therapy. Further investigation on the parameters and conditions for the manufacture, storage and delivery of aerosolized phage products will bridge this knowledge gap and inform the design of therapeutically effective aerosolized phage formulations. Future studies must identify suitable phages or phage characteristics, buffer conditions, and aerosolization conditions resulting in minimal titer loss, ensuring that aerosolized phage formulations have maximal therapeutic activity upon delivery.

Author Contributions

The topic of the review was conceptualized by R.F., D.R.L., A.K. and R.F. performed a literature review and drafted a manuscript. D.R.L., H.-K.C., B.J.C., S.M.S. and A.K. contributed to the content and structure, and they also provided a critical review of the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by an Australian Medical Research Future Fund grant (2023559). R.F is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, University of Western Australia University Postgraduate Award and the CFWA Post Graduate Top up Scholarship. A.K. is a Rothwell Family Fellow. S.M.S. is a NHMRC Practitioner-Fellow.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. The Top 10 Causes of Death; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, P.; Nyboe, J.; Appleyard, M.; Jensen, G.; Schnohr, P. Relation of ventilatory impairment and of chronic mucus hypersecretion to mortality from obstructive lung disease and from all causes. Thorax 1990, 45, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, B.M.; Bartlett, C.L.R.; Wadsworth, J.; Miller, D.L. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia diagnosed upon hospital admission. Respir. Med. 2000, 94, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.J.; LiPuma, J.J. The microbiome in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Chest Med. 2016, 37, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillarisetti, N.; Williamson, E.; Linnane, B.; Skoric, B.; Robertson, C.F.; Robinson, P.; Massie, J.; Hall, G.L.; Sly, P.; Stick, S.; et al. Infection, inflammation, and lung function decline in infants with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 184, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, L.W.; Breuer, O.; Schofield, C.J.; McLean, S.A.; Laucirica, D.R.; Tirouvanziam, R.; Clements, B.S.; Kicic, A.; Ranganathan, S.; Stick, S.M.; et al. Changes in airway inflammation with Pseudomonas eradication in early cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2021, 20, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Clemente, M.; de la Rosa, D.; Máiz, L.; Girón, R.; Blanco, M.; Olveira, C.; Canton, R.; Martinez-García, M.A. Impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection on Patients with Chronic Inflammatory Airway Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingpej, P.; Smith, L.; Rose, B.; Zhu, H.; Conibear, T.; Al Nassafi, K.; Manos, J.; Elkins, M.; Bye, P.; Willcox, M. Phenotypic characterization of clonal and nonclonal Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from lungs of adults with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durda-Masny, M.; Goździk-Spychalska, J.; John, A.; Czaiński, W.; Stróżewska, W.; Pawłowska, N.; Wlizło, J.; Batura-Gabryel, H.; Szwed, A. The determinants of survival among adults with cystic fibrosis-a cohort study. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2021, 40, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Goździk-Spychalska, J.; Durda-Masny, M.; Czaiński, W.; Pawłowska, N.; Wlizło, J.; Batura-Gabryel, H.; Szwed, A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the type of mutation, lung function, and nutritional status in adults with cystic fibrosis. Nutrition 2021, 89, 111221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-García, M.A.; Oscullo, G.; Posadas, T.; Zaldivar, E.; Villa, C.; Dobarganes, Y.; Girón, R.; Olveira, C.; Maíz, L.; García-Clemente, M.; et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and lung function decline in patients with bronchiectasis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklöf, J.; Sørensen, R.; Ingebrigtsen, T.S.; Sivapalan, P.; Achir, I.; Boel, J.B.; Bangsborg, J.; Ostergaard, C.; Dessau, R.B.; Jensen, U.S.; et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and risk of death and exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: An observational cohort study of 22,053 patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, M.J.; Jary, H.R.; Perry, A.; MacFarlane, J.G.; Hester, K.L.; Small, T.; Molyneux, C.; Perry, J.D.; Walton, K.E.; De Soyza, A. Non cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: A longitudinal retrospective observational cohort study of Pseudomonas persistence and resistance. Respir. Med. 2015, 109, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradali, M.F.; Ghods, S.; Rehm, B.H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lifestyle: A paradigm for adaptation, survival, and persistence. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, G.; Hoiby, N.; Group, C.S. Early intervention and prevention of lung disease in cystic fibrosis: A European consensus. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2004, 3, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainardi, V.; Neglia, C.; Muscarà, M.; Spaggiari, C.; Tornesello, M.; Grandinetti, R.; Argentiero, A.; Calderaro, A.; Esposito, S.; Pisi, G. Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria in Children and Adolescents with Cystic Fibrosis. Children 2022, 9, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, M.; Domínguez, M.; Orozco-Levi, M.; Salvadó, M.; Knobel, H. Mortality of COPD patients infected with multi-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A case and control study. Infection 2009, 37, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quon, B.S.; Goss, C.H.; Ramsey, B.W. Inhaled antibiotics for lower airway infections. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2014, 11, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taccetti, G.; Francalanci, M.; Pizzamiglio, G.; Messore, B.; Carnovale, V.; Cimino, G.; Cipolli, M. Cystic Fibrosis: Recent Insights into Inhaled Antibiotic Treatment and Future Perspectives. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventola, C.L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: Part 1: Causes and threats. Pharm. Therap 2015, 40, 277. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A.; Hawkins, C.; Änggård, E.; Harper, D. A controlled clinical trial of a therapeutic bacteriophage preparation in chronic otitis due to antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa; a preliminary report of efficacy. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2009, 34, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoe, S.; Semler, D.D.; Goudie, A.D.; Lynch, K.H.; Matinkhoo, S.; Finlay, W.H.; Dennis, J.J.; Vehring, R. Respirable bacteriophages for the treatment of bacterial lung infections. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2013, 26, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeau, A.M.; Hatfull, G.F.; Krisch, H.M.; Lindell, D.; Mann, N.H.; Prangishvili, D. Exploring the prokaryotic virosphere. Res. Microbiol. 2008, 159, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herelle, F. An invisible microbe that is antagonistic to the dysentery bacillus Cozzes rendus. CR Acad. Sci. 1917, 165, 373–375. [Google Scholar]

- Twort, F.W. An investigation on the nature of ultra-microscopic viruses. Lancet 1915, 186, 1241–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K. Bacteriophage therapy for bacterial infections. Rekindling a memory from the pre-antibiotics era. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2001, 44, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herelle, F.H.d. The Bacteriophage and Its Behavior; The Williams & Wilkins Company: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Chanishvili, N. Phage therapy—History from Twort and d’Herelle through Soviet experience to current approaches. Adv. Virus Res. 2012, 83, 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T.; Kuhl, S.J.; Blasdel, B.G.; Kutter, E.M. Phage treatment of human infections. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clokie, M.R.; Millard, A.D.; Letarov, A.V.; Heaphy, S. Phages in nature. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principi, N.; Silvestri, E.; Esposito, S. Advantages and Limitations of Bacteriophages for the Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Johnson, C.T.; Imhoff, B.R.; Donlan, R.M.; McCarty, N.A.; García, A.J. Inhaled bacteriophage-loaded polymeric microparticles ameliorate acute lung infections. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, D.; Casey, P.G.; McAuliffe, O.; Guinane, C.M.; Martin, J.G.; Shanahan, F.; Coffey, A.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C. Bacteriophages φMR299-2 and φNH-4 can eliminate Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the murine lung and on cystic fibrosis lung airway cells. mBio 2012, 3, e00029-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Van Belleghem, J.D.; de Vries, C.R.; Burgener, E.; Chen, Q.; Manasherob, R.; Aronson, J.R.; Amanatullah, D.F.; Tamma, P.D.; Suh, G.A. The Safety and Toxicity of Phage Therapy: A Review of Animal and Clinical Studies. Viruses 2021, 13, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levison, M.E.; Levison, J.H. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antibacterial agents. Infect. Dis. Clin. 2009, 23, 791–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingeot-Leclercq, M.-P.; Tulkens, P.M. Aminoglycosides: Nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brummett, R.E.; Fox, K.E. Aminoglycoside-induced hearing loss in humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1989, 33, 797–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Bacteriophage Ecology: Population Growth, Evolution, and Impact of Bacterial Viruses; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Little, J.; Waldor, M.; Friedman, D.; Adhya, S. Phages: Their Role in Bacterial Pathogenesis and Biotechnology; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sulakvelidze, A.; Alavidze, Z.; Morris, J.G., Jr. Bacteriophage therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Prasad, Y. Efficacy of polyvalent bacteriophage P-27/HP to control multidrug resistant Staphylococcus aureus associated with human infections. Curr. Microbiol. 2011, 62, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutter, E.; Sulakvelidze, A.; Summers, W.; Guttman, B.; Raya, R.; Brüssow, H.; Ecology, P.; Carlson, K. Bacteriophages: Biology and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thiel, K. Old dogma, new tricks—21st Century phage therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.; McAuliffe, O.; Ross, R.P.; O’Mahony, J.; Coffey, A. Development of a broad-host-range phage cocktail for biocontrol. Bioeng. Bugs 2011, 2, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, H.D.M.; Falcão-Silva, V.S.; Gonçalves, F.G. Pulmonary bacterial pathogens in cystic fibrosis patients and antibiotic therapy: A tool for the health workers. Int. Arch. Med. 2008, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schooley, R.; Biswas, B.; Gill, J.J.; Hernandez-Morales, A.; Lancaster, J.; Lessor, L.; Barr, J.J.; Reed, S.L.; Rohwer, F.; Benler, S. Development and use of personalized bacteriophage-based therapeutic cocktails to treat a patient with a disseminated resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00954-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovic Fabijan, A.; Lin, R.C.; Ho, J.; Maddocks, S.; Ben Zakour, N.L.; Iredell, J.R. Safety of bacteriophage therapy in severe Staphylococcus aureus infection. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, B.K.; Turner, P.E.; Kim, S.; Mojibian, H.R.; Elefteriades, J.A.; Narayan, D. Phage treatment of an aortic graft infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Evol. Med. Public. Health 2018, 2018, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddocks, S.; Fabijan, A.P.; Ho, J.; Lin, R.C.Y.; Zakour, N.L.B.; Dugan, C.; Kliman, I.; Branston, S.; Morales, S.; Iredell, J.R. Bacteriophage Therapy of Ventilator-associated Pneumonia and Empyema Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 1179–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S. Chapter 1—Phage Therapy Pharmacology: Calculating Phage Dosing. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Laskin, A.I., Sariaslani, S., Gadd, G.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 77, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, A.S. Phage therapy—Constraints and possibilities. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 119, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prazak, J.; Valente, L.G.; Iten, M.; Federer, L.; Grandgirard, D.; Soto, S.; Resch, G.; Leib, S.L.; Jakob, S.M.; Haenggi, M.; et al. Benefits of Aerosolized Phages for the Treatment of Pneumonia Due to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An Experimental Study in Rats. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 225, 1452–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoloff, A.V.; Zhang, G.; Sebestyén, M.G.; Wolff, J.A.; Bock, I. The interactions of peptides with the innate immune system studied with use of T7 phage peptide display. Mol. Ther. 2000, 2, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.A.; McCallin, S.; Barretto, C.; Berger, B.; Pittet, A.C.; Sultana, S.; Krause, L.; Huq, S.; Bibiloni, R.; Bruttin, A.; et al. Oral T4-like phage cocktail application to healthy adult volunteers from Bangladesh. Virology 2012, 434, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallin, S.; Alam Sarker, S.; Barretto, C.; Sultana, S.; Berger, B.; Huq, S.; Krause, L.; Bibiloni, R.; Schmitt, B.; Reuteler, G.; et al. Safety analysis of a Russian phage cocktail: From MetaGenomic analysis to oral application in healthy human subjects. Virology 2013, 443, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merabishvili, M.; Pirnay, J.-P.; Verbeken, G.; Chanishvili, N.; Tediashvili, M.; Lashkhi, N.; Glonti, T.; Krylov, V.; Mast, J.; Van Parys, L. Quality-controlled small-scale production of a well-defined bacteriophage cocktail for use in human clinical trials. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, H.D.C.; Hickey, A.J. Controlled Pulmonary Drug Delivery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, I.; Wallet, F.; Nicolas-Robin, A.; Ferrari, F.; Marquette, C.-H.; Rouby, J.-J. Lung Deposition and Efficiency of Nebulized Amikacin during Escherichia coli Pneumonia in Ventilated Piglets. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, R.J. Formulation of aerosolized therapeutics. Chest 2001, 120, 94s–98s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, B.W.; Pepe, M.S.; Quan, J.M.; Otto, K.L.; Montgomery, A.B.; Williams-Warren, J.; Vasiljev, K.M.; Borowitz, D.; Bowman, C.M.; Marshall, B.C.; et al. Intermittent administration of inhaled tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis. Cystic Fibrosis Inhaled Tobramycin Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, B.W.; Dorkin, H.L.; Eisenberg, J.D.; Gibson, R.L.; Harwood, I.R.; Kravitz, R.M.; Schidlow, D.V.; Wilmott, R.W.; Astley, S.J.; McBurnie, M.A.; et al. Efficacy of aerosolized tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 328, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.J.; Denyer, S.P.; Maillard, J.Y. Stability and purity of a bacteriophage cocktail preparation for nebulizer delivery. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 58, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astudillo, A.; Leung, S.S.Y.; Kutter, E.; Morales, S.; Chan, H.-K. Nebulization effects on structural stability of bacteriophage PEV 44. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 125, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrigy, N.B.; Chang, R.Y.; Leung, S.S.; Harrison, M.; Petrova, Z.; Pope, W.H.; Hatfull, G.F.; Britton, W.J.; Chan, H.-K.; Sauvageau, D. Anti-tuberculosis bacteriophage D29 delivery with a vibrating mesh nebulizer, jet nebulizer, and soft mist inhaler. Pharm. Res. 2017, 34, 2084–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.S.Y.; Parumasivam, T.; Gao, F.G.; Carrigy, N.B.; Vehring, R.; Finlay, W.H.; Morales, S.; Britton, W.J.; Kutter, E.; Chan, H.-K. Production of Inhalation Phage Powders Using Spray Freeze Drying and Spray Drying Techniques for Treatment of Respiratory Infections. Pharm. Res. 2016, 33, 1486–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merabishvili, M.; Vervaet, C.; Pirnay, J.-P.; De Vos, D.; Verbeken, G.; Mast, J.; Chanishvili, N.; Vaneechoutte, M. Stability of Staphylococcus aureus phage ISP after freeze-drying (lyophilization). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenheuvel, D.; Singh, A.; Vandersteegen, K.; Klumpp, J.; Lavigne, R.; Van den Mooter, G. Feasibility of spray drying bacteriophages into respirable powders to combat pulmonary bacterial infections. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013, 84, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golshahi, L.; Seed, K.D.; Dennis, J.J.; Finlay, W.H. Toward modern inhalational bacteriophage therapy: Nebulization of bacteriophages of Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. 2008, 21, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahota, J.S.; Smith, C.M.; Radhakrishnan, P.; Winstanley, C.; Goderdzishvili, M.; Chanishvili, N.; Kadioglu, A.; O’Callaghan, C.; Clokie, M.R.J. Bacteriophage delivery by nebulization and efficacy against phenotypically diverse Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis patients. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. 2015, 28, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallion, O.N.M.; Taylor, K.M.G.; Bridges, P.A.; Thomas, M.; Taylor, A.J. Jet nebulisers for pulmonary drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 1996, 130, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, W.H.; Lange, C.F.; King, M.; Speert, D.P. Lung Delivery of Aerosolized Dextran. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 161, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, W.H. The Mechanics of Inhaled Pharmaceutical Aerosols: An Introduction; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Flament, M.; Leterme, P.; Gayot, A. Study of the technological parameters of ultrasonic nebulization. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2001, 27, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecellio, L. The mesh nebuliser: A recent technical innovation for aerosol delivery. Breathe 2006, 2, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, A.; Beck-Broichsitter, M. Generation of tailored aerosols for inhalative drug delivery employing recent vibrating-mesh nebulizer systems. Ther. Deliv. 2015, 6, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoch, M.; Finlay, W. Nebulizer Technologies. In Modified-Release Drug Delivery Technology, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- May, K.R. The collison nebulizer: Description, performance and application. J. Aerosol Sci. 1973, 4, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.Y.; Wong, J.; Mathai, A.; Morales, S.; Kutter, E.; Britton, W.; Li, J.; Chan, H.-K. Production of highly stable spray dried phage formulations for treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 121, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.Y.K.; Wallin, M.; Kutter, E.; Morales, S.; Britton, W.; Li, J.; Chan, H.-K. Storage stability of inhalable phage powders containing lactose at ambient conditions. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 560, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Porat, S.; Gelman, D.; Yerushalmy, O.; Alkalay-Oren, S.; Coppenhagen-Glazer, S.; Cohen-Cymberknoh, M.; Kerem, E.; Amirav, I.; Nir-Paz, R.; Hazan, R. Expanding clinical phage microbiology: Simulating phage inhalation for respiratory tract infections. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, S.S.Y.; Carrigy, N.B.; Vehring, R.; Finlay, W.H.; Morales, S.; Carter, E.A.; Britton, W.J.; Kutter, E.; Chan, H.K. Jet nebulization of bacteriophages with different tail morphologies—Structural effects. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 554, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semler, D.D.; Goudie, A.D.; Finlay, W.H.; Dennis, J.J. Aerosol phage therapy efficacy in Burkholderia cepacia complex respiratory infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4005–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillon, A.; Pardessus, J.; L’Hostis, G.; Fevre, C.; Barc, C.; Dalloneau, E.; Jouan, Y.; Bodier-Montagutelli, E.; Perez, Y.; Thorey, C.; et al. Inhaled bacteriophage therapy in a porcine model of pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa during mechanical ventilation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 3829–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgeon, N.; Toulouse, M.J.; Martel, B.; Moineau, S.; Duchaine, C. Comparison of five bacteriophages as models for viral aerosol studies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 4242–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.Y.; Yang, W.H.; Dong, X.K.; Cong, L.M.; Li, N.; Li, Y.; Wen, Z.B.; Yin, Z.; Lan, Z.J.; Li, W.P.; et al. Inhalation Study of Mycobacteriophage D29 Aerosol for Mice by Endotracheal Route and Nose-Only Exposure. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 2016, 29, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigy, N.B.; Liang, L.; Wang, H.; Kariuki, S.; Nagel, T.E.; Connerton, I.F.; Vehring, R. Spray-dried anti-Campylobacter bacteriophage CP30A powder suitable for global distribution without cold chain infrastructure. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 569, 118601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, C.; De Urraza, P.J. Effect of buffer systems and disaccharides concentration on Podoviridae coliphage stability during freeze drying and storage. Cryobiology 2013, 66, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puapermpoonsiri, U.; Ford, S.; Van der Walle, C. Stabilization of bacteriophage during freeze drying. Int. J. Pharm. 2010, 389, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chang, R.Y.K.; Britton, W.J.; Morales, S.; Kutter, E.; Li, J.; Chan, H.K. Inhalable combination powder formulations of phage and ciprofloxacin for P. aeruginosa respiratory infections. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 142, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Quan, D.; Chang, R.Y.K.; Chow, M.Y.T.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Morales, S.; Britton, W.J.; Kutter, E.; Li, J.; et al. Synergistic activity of phage PEV20-ciprofloxacin combination powder formulation—A proof-of-principle study in a P. aeruginosa lung infection model. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021, 158, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.Y.K.; Chen, K.; Wang, J.; Wallin, M.; Britton, W.; Morales, S.; Kutter, E.; Li, J.; Chan, H.-K. Proof-of-Principle Study in a Murine Lung Infection Model of Antipseudomonal Activity of Phage PEV20 in a Dry-Powder Formulation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01714-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Menendez, E.; Fernandez, L.; Gutierrez, D.; Rodriguez, A.; Martinez, B.; Garcia, P. Comparative analysis of different preservation techniques for the storage of Staphylococcus phages aimed for the industrial development of phage-based antimicrobial products. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merabishvili, M.; Pirnay, J.P.; De Vos, D. Guidelines to Compose an Ideal Bacteriophage Cocktail. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1693, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Governal, R.; Gerba, C. Persistence of MS-2 and PRD-1 bacteriophages in an ultrapure water system. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1997, 18, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovkach, F.; Zhuminska, H.I.; Kushkina, A. Long-term preservation of unstable bacteriophages of enterobacteria. Mikrobiologičnij Žurnal 2012, 74, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Morello, E.; Saussereau, E.; Maura, D.; Huerre, M.; Touqui, L.; Debarbieux, L. Pulmonary bacteriophage therapy on Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis strains: First steps towards treatment and prevention. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdin, G.; Schmitt, B.; Marvin Guy, L.; Germond, J.-E.; Zuber, S.; Michot, L.; Reuteler, G.; Brüssow, H. Amplification and purification of T4-like Escherichia coli phages for phage therapy: From laboratory to pilot scale. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, N.; Zhvaniya, P.; Balarjishvili, N.; Bolkvadze, D.; Nadareishvili, L.; Nizharadze, D.; Wittmann, J.; Rohde, C.; Kutateladze, M. Phage therapy against Achromobacter xylosoxidans lung infection in a patient with cystic fibrosis: A case report. Res. Microbiol. 2018, 169, 540–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verreault, D.; Marcoux-Voiselle, M.; Turgeon, N.; Moineau, S.; Duchaine, C. Resistance of aerosolized bacterial viruses to relative humidity and temperature. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 7305–7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Wen, Z.; Li, N.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Hu, L.; Dong, X.; Lu, J.; Li, J. Impact of relative humidity and collection media on mycobacteriophage D29 aerosol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 1466–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Y.; Vogel, G.; Wunderli, W.; Suter, P.; Witschi, M.; Koch, D.; Tapparel, C.; Kaiser, L. Survival of influenza virus on banknotes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 3002–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Respaud, R.; Marchand, D.; Parent, C.; Pelat, T.; Thullier, P.; Tournamille, J.F.; Viaud-Massuard, M.C.; Diot, P.; Si-Tahar, M.; Vecellio, L.; et al. Effect of formulation on the stability and aerosol performance of a nebulized antibody. MAbs 2014, 6, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahler, H.C.; Friess, W.; Grauschopf, U.; Kiese, S. Protein aggregation: Pathways, induction factors and analysis. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 2909–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillpotts, R.J.; Thomas, R.J.; Beedham, R.J.; Platt, S.D.; Vale, C.A. The Cystovirus phi6 as a simulant for Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. Aerobiologia 2010, 26, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, H.W. 5500 Phages examined in the electron microscope. Arch. Virol. 2007, 152, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfari, T.; Elhissi, A.M.A.; Ding, Z.; Taylor, K.M.G. The influence of fluid physicochemical properties on vibrating-mesh nebulization. Int. J. Pharm. 2007, 339, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallion, O.; Patel, M. Viscosity effects on nebulization of aqueous solutions. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1995, 47, 1117. [Google Scholar]

- Abedon, S.T. Phage therapy dosing: The problem(s) with multiplicity of infection (MOI). Bacteriophage 2016, 6, e1220348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.; Dąbrowska, K.; Abedon, S.T. Phage Therapy: The Pharmacology of Antibacterial Viruses. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 40, 81–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, R.J.H.; Jansen, V.A.A. Phage therapy: The peculiar kinetics of self-replicating pharmaceuticals. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 68, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbrowska, K. Phage therapy: What factors shape phage pharmacokinetics and bioavailability? Systematic and critical review. Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 39, 2000–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebeaux, D.; Merabishvili, M.; Caudron, E.; Lannoy, D.; Van Simaey, L.; Duyvejonck, H.; Guillemain, R.; Thumerelle, C.; Podglajen, I.; Compain, F.; et al. A Case of Phage Therapy against Pandrug-Resistant Achromobacter xylosoxidans in a 12-Year-Old Lung-Transplanted Cystic Fibrosis Patient. Viruses 2021, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, W.; Ma, Y. Clinical Experience of Personalized Phage Therapy Against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Lung Infection in a Patient With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 631585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Betancourt-Garcia, M.; Kare-Opaneye, Y.O.; Swierczewski, B.E.; Bennett, J.W.; Horne, B.A.; Fackler, J.; Hernandez, L.P.S.; Brownstein, M.J. Critically Ill Patient with Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Respiratory Infection Successfully Treated with Intravenous and Nebulized Bacteriophage Therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e00824-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, T.; Luscher, A.; Falconnet, L.; Resch, G.; McBride, R.; Mai, Q.-A.; Simonin, J.L.; Chanson, M.; Maco, B.; Galiotto, R.; et al. Personalized aerosolised bacteriophage treatment of a chronic lung infection due to multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Dai, J.; Guo, M.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, F.; Gao, Y.; Qu, H.; Lu, H.; Jin, J.; et al. Pre-optimized phage therapy on secondary Acinetobacter baumannii infection in four critical COVID-19 patients. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolovich, M.B.; Dhand, R. Aerosol drug delivery: Developments in device design and clinical use. Lancet 2011, 377, 1032–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.P. Aerosol Deposition Considerations in Inhalation Therapy. Chest 1985, 88, 152S–160S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, A.C.; Passé, K.M.; Mouton, J.W.; Janssens, H.M.; Tiddens, H.A.W.M. The fate of inhaled antibiotics after deposition in cystic fibrosis: How to get drug to the bug? J. Cyst. Fibros. 2017, 16, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ari, A. Aerosol Therapy in Pulmonary Critical Care. Resp. Care 2015, 60, 858–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, J.S.; Byron, P.R. Inhaling medicines: Delivering drugs to the body through the lungs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).