Restructuring of Lamina-Associated Domains in Senescence and Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

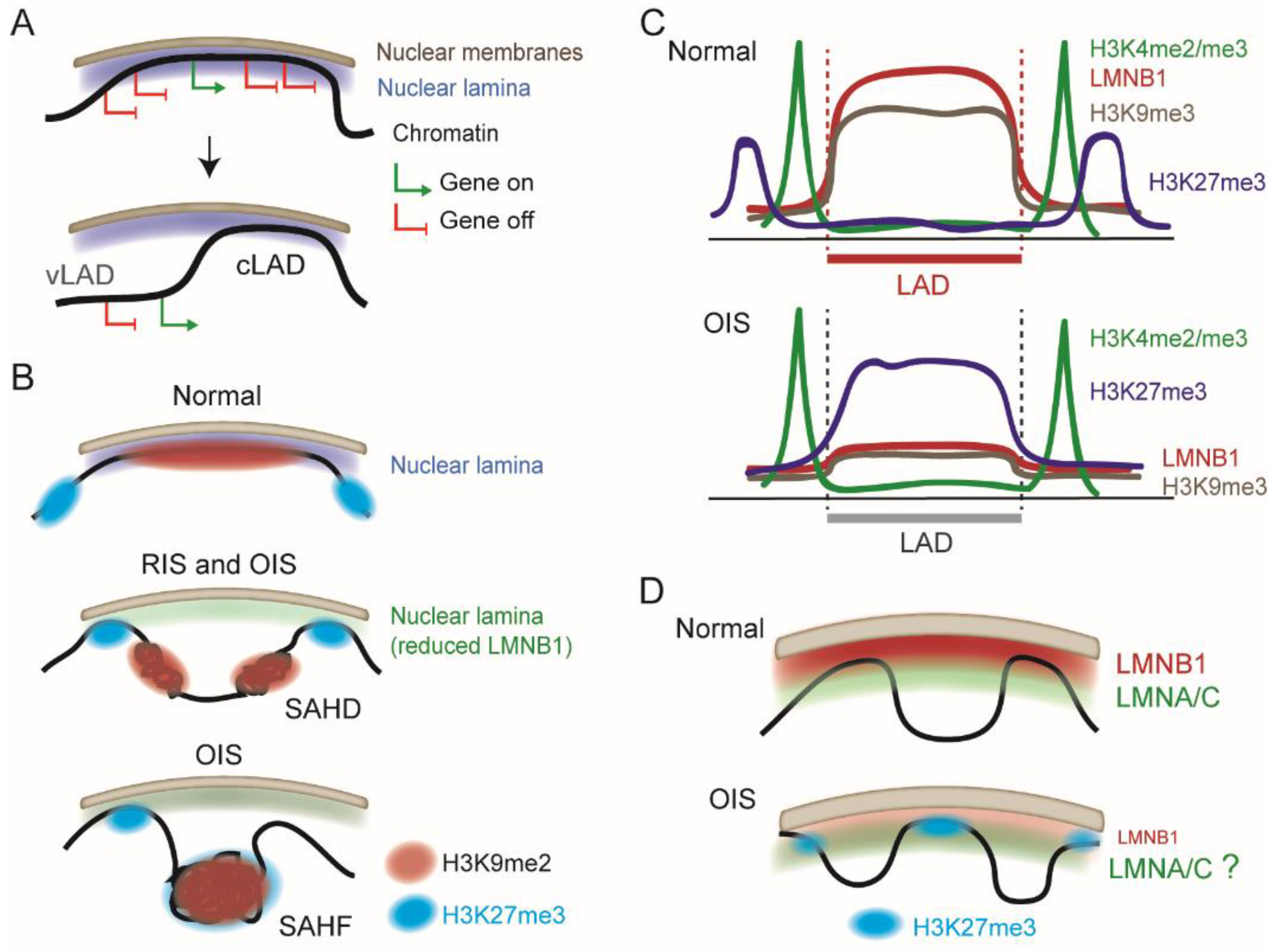

2. Chromatin Organization at the Nuclear Periphery: Consistency and Variation in LADs

3. Chromatin Remodeling Elicited by Senescence

4. Repositioning of LADs during Oncogene-Induced Senescence

5. What Do We Know about LADs in Cancer?

6. Re-KODing LOCKs in Tumor Cells?

7. Euchromatic LADs Associated with EMT

8. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lecot, P.; Alimirah, F.; Desprez, P.Y.; Campisi, J.; Wiley, C. Context-dependent effects of cellular senescence in cancer development. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 114, 1180–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, J.; Liu, M.; Hong, D.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, X. The Paradoxical Role of Cellular Senescence in Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 722205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criscione, S.W.; Teo, Y.V.; Neretti, N. The Chromatin Landscape of Cellular Senescence. Trends Genet. 2016, 32, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crouch, J.; Shvedova, M.; Thanapaul, R.; Botchkarev, V.; Roh, D. Epigenetic Regulation of Cellular Senescence. Cells 2022, 11, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, R. Chromatin basis of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Trends Cell Biol. 2022, 32, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangelinck, A.; Mann, C. DNA methylation and histone variants in aging and cancer. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 364, 1–110. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, S.; Feng, Y.; Pauklin, S. 3D chromatin architecture and transcription regulation in cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, G.; Lupien, M. Cancer-associated chromatin variants uncover the oncogenic role of transposable elements. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2022, 74, 101911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, I.Y.; Ahn, J.H.; Wang, G.G.; Phanstiel, D. Oncogenic fusion proteins and their role in three-dimensional chromatin structure, phase separation, and cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2022, 74, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, M.J.; Corces, V.G. Organizational principles of 3D genome architecture. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti-Renom, M.A.; Almouzni, G.; Bickmore, W.A.; Bystricky, K.; Cavalli, G.; Fraser, P.; Gasser, S.M.; Giorgetti, L.; Heard, E.; Nicodemi, M.; et al. Challenges and guidelines toward 4D nucleome data and model standards. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mirny, L.A.; Imakaev, M.; Abdennur, N. Two major mechanisms of chromosome organization. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2019, 58, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niskanen, H.; Tuszynska, I.; Zaborowski, R.; Heinaniemi, M.; Yla-Herttuala, S.; Wilczynski, B.; Kaikkonen, M.U. Endothelial cell differentiation is encompassed by changes in long range interactions between inactive chromatin regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 1724–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quinodoz, S.A.; Ollikainen, N.; Tabak, B.; Palla, A.; Schmidt, J.M.; Detmar, E.; Lai, M.M.; Shishkin, A.A.; Bhat, P.; Takei, Y.; et al. Higher-Order Inter-chromosomal Hubs Shape 3D Genome Organization in the Nucleus. Cell 2018, 174, 744–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paulsen, J.; Liyakat Ali, T.M.; Nekrasov, M.; Delbarre, E.; Baudement, M.O.; Kurscheid, S.; Tremethick, D.; Collas, P. Long-range interactions between topologically associating domains shape the four-dimensional genome during differentiation. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, B.; Stewart, C.L. The nuclear lamins: Flexibility in function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchwalter, A.; Kaneshiro, J.M.; Hetzer, M.W. Coaching from the sidelines: The nuclear periphery in genome regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Steensel, B.; Belmont, A.S. Lamina-Associated Domains: Links with Chromosome Architecture, Heterochromatin, and Gene Repression. Cell 2017, 169, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Briand, N.; Collas, P. Lamina-associated domains: Peripheral matters and internal affairs. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meuleman, W.; Peric-Hupkes, D.; Kind, J.; Beaudry, J.B.; Pagie, L.; Kellis, M.; Reinders, M.; Wessels, L.; van Steensel, B. Constitutive nuclear lamina-genome interactions are highly conserved and associated with A/T-rich sequence. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keough, K.C.; Shah, P.P.; Wickramasinghe, N.M.; Dundes, C.E.; Chen, A.; Salomon, R.E.A.; Whalen, S.; Loh, K.M.; Dubois, N.; Pollard, K.S.; et al. An atlas of lamina-associated chromatin across thirteen human cell types reveals cell-type-specific and multiple subtypes of peripheral heterochromatin. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peric-Hupkes, D.; Meuleman, W.; Pagie, L.; Bruggeman, S.W.; Solovei, I.; Brugman, W.; Graf, S.; Flicek, P.; Kerkhoven, R.M.; van Lohuizen, M.; et al. Molecular maps of the reorganization of genome-nuclear lamina interactions during differentiation. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rønningen, T.; Shah, A.; Oldenburg, A.R.; Vekterud, K.; Delbarre, E.; Moskaug, J.O.; Collas, P. Prepatterning of differentiation-driven nuclear lamin A/C-associated chromatin domains by GlcNAcylated histone H2B. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1825–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leemans, C.; van der Zwalm, M.C.H.; Brueckner, L.; Comoglio, F.; van Schaik, T.; Pagie, L.; van Arensbergen, J.; van Steensel, B. Promoter-Intrinsic and Local Chromatin Features Determine Gene Repression in LADs. Cell 2019, 177, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Madsen-Østerbye, J.; Abdelhalim, M.; Baudement, M.O.; Collas, P. Local euchromatin enrichment in lamina-associated domains anticipates their re-positioning in the adipogenic lineage. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Reguant, L.; Blanco, E.; Galan, S.; Le Dily, F.; Cuartero, Y.; Serra-Bardenys, G.; Di Carlo, V.; Iturbide, A.; Cebria-Costa, J.P.; Nonell, L.; et al. Lamin B1 mapping reveals the existence of dynamic and functional euchromatin lamin B1 domains. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czapiewski, R.; Batrakou, D.G.; de las Heras, J.; Carter, R.N.; Sivakumar, A.; Sliwinska, M.; Dixon, C.R.; Webb, S.; Lattanzi, G.; Morton, N.M.; et al. Genomic loci mispositioning in Tmem120a knockout mice yields latent lipodystrophy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, M.I.; de Las Heras, J.I.; Czapiewski, R.; Le Thanh, P.; Booth, D.G.; Kelly, D.A.; Webb, S.; Kerr, A.R.W.; Schirmer, E.C. Tissue-Specific Gene Repositioning by Muscle Nuclear Membrane Proteins Enhances Repression of Critical Developmental Genes during Myogenesis. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reddy, K.L.; Zullo, J.M.; Bertolino, E.; Singh, H. Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to the nuclear lamina. Nature 2008, 452, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, F.; Brunet, A.; Ali, T.M.L.; Collas, P. Interplay of lamin A and lamin B LADs on the radial positioning of chromatin. Nucleus 2019, 10, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gesson, K.; Rescheneder, P.; Skoruppa, M.P.; von Haeseler, A.; Dechat, T.; Foisner, R. A-type lamins bind both hetero- and euchromatin, the latter being regulated by lamina-associated polypeptide 2 alpha. Genome Res. 2016, 26, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oldenburg, A.; Briand, N.; Sorensen, A.L.; Cahyani, I.; Shah, A.; Moskaug, J.O.; Collas, P. A lipodystrophy-causing lamin A mutant alters conformation and epigenetic regulation of the anti-adipogenic MIR335 locus. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 2731–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ikegami, K.; Secchia, S.; Almakki, O.; Lieb, J.D.; Moskowitz, I.P. Phosphorylated Lamin A/C in the Nuclear Interior Binds Active Enhancers Associated with Abnormal Transcription in Progeria. Dev. Cell 2020, 52, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiley, C.D.; Campisi, J. The metabolic roots of senescence: Mechanisms and opportunities for intervention. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 1290–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cecco, M.; Criscione, S.W.; Peterson, A.L.; Neretti, N.; Sedivy, J.M.; Kreiling, J.A. Transposable elements become active and mobile in the genomes of aging mammalian somatic tissues. Aging 2013, 5, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Cecco, M.; Criscione, S.W.; Peckham, E.J.; Hillenmeyer, S.; Hamm, E.A.; Manivannan, J.; Peterson, A.L.; Kreiling, J.A.; Neretti, N.; Sedivy, J.M. Genomes of replicatively senescent cells undergo global epigenetic changes leading to gene silencing and activation of transposable elements. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, S.; Bonev, B.; Szabo, Q.; Jost, D.; Bensadoun, P.; Serra, F.; Loubiere, V.; Papadopoulos, G.L.; Rivera-Mulia, J.C.; Fritsch, L.; et al. 4D Genome Rewiring during Oncogene-Induced and Replicative Senescence. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, M.; Nunez, S.; Heard, E.; Narita, M.; Lin, A.W.; Hearn, S.A.; Spector, D.L.; Hannon, G.J.; Lowe, S.W. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell 2003, 113, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chandra, T.; Kirschner, K.; Thuret, J.Y.; Pope, B.D.; Ryba, T.; Newman, S.; Ahmed, K.; Samarajiwa, S.A.; Salama, R.; Carroll, T.; et al. Independence of repressive histone marks and chromatin compaction during senescent heterochromatic layer formation. Mol. Cell 2012, 47, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadaie, M.; Salama, R.; Carroll, T.; Tomimatsu, K.; Chandra, T.; Young, A.R.; Narita, M.; Perez-Mancera, P.A.; Bennett, D.C.; Chong, H.; et al. Redistribution of the Lamin B1 genomic binding profile affects rearrangement of heterochromatic domains and SAHF formation during senescence. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1800–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shimi, T.; Butin-Israeli, V.; Adam, S.A.; Hamanaka, R.B.; Goldman, A.E.; Lucas, C.A.; Shumaker, D.K.; Kosak, S.T.; Chandel, N.S.; Goldman, R.D. The role of nuclear lamin B1 in cell proliferation and senescence. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 2579–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shah, P.P.; Donahue, G.; Otte, G.L.; Capell, B.C.; Nelson, D.M.; Cao, K.; Aggarwala, V.; Cruickshanks, H.A.; Rai, T.S.; McBryan, T.; et al. Lamin B1 depletion in senescent cells triggers large-scale changes in gene expression and the chromatin landscape. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dreesen, O.; Chojnowski, A.; Ong, P.F.; Zhao, T.Y.; Common, J.E.; Lunny, D.; Lane, E.B.; Lee, S.J.; Vardy, L.A.; Stewart, C.L.; et al. Lamin B1 fluctuations have differential effects on cellular proliferation and senescence. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Freund, A.; Laberge, R.M.; Demaria, M.; Campisi, J. Lamin B1 loss is a senescence-associated biomarker. Mol. Biol. Cell 2012, 23, 2066–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, T.; Ewels, P.A.; Schoenfelder, S.; Furlan-Magaril, M.; Wingett, S.W.; Kirschner, K.; Thuret, J.Y.; Andrews, S.; Fraser, P.; Reik, W. Global reorganization of the nuclear landscape in senescent cells. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, M.; Michieletto, D.; Brackley, C.A.; Rattanavirotkul, N.; Mohammed, H.; Marenduzzo, D.; Chandra, T. Polymer Modeling Predicts Chromosome Reorganization in Senescence. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 3212–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rocha, A.; Dalgarno, A.; Neretti, N. The functional impact of nuclear reorganization in cellular senescence. Brief Funct. Genom. 2022, 21, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenain, C.; de Graaf, C.A.; Pagie, L.; Visser, N.L.; de Haas, M.; de Vries, S.S.; Peric-Hupkes, D.; van Steensel, B.; Peeper, D.S. Massive reshaping of genome-nuclear lamina interactions during oncogene-induced senescence. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 1634–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.M.; Rendtlew Danielsen, J.M.; Lucas, C.A.; Rice, E.L.; Scalzo, D.; Shimi, T.; Goldman, R.D.; Smith, E.D.; Le Beau, M.M.; Kosak, S.T. TRF2 and lamin A/C interact to facilitate the functional organization of chromosome ends. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Suarez, I.; Redwood, A.B.; Perkins, S.M.; Vermolen, B.; Lichtensztejin, D.; Grotsky, D.A.; Morgado-Palacin, L.; Gapud, E.J.; Sleckman, B.P.; Sullivan, T.; et al. Novel roles for A-type lamins in telomere biology and the DNA damage response pathway. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 2414–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasova, E.; Kovarik, A.; Kozubek, S. Consequences of Lamin B1 and Lamin B Receptor Downregulation in Senescence. Cells 2018, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Cecco, M.; Ito, T.; Petrashen, A.P.; Elias, A.E.; Skvir, N.J.; Criscione, S.W.; Caligiana, A.; Brocculi, G.; Adney, E.M.; Boeke, J.D.; et al. L1 drives IFN in senescent cells and promotes age-associated inflammation. Nature 2019, 566, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criscione, S.W.; De Cecco, M.; Siranosian, B.; Zhang, Y.; Kreiling, J.A.; Sedivy, J.M.; Neretti, N. Reorganization of chromosome architecture in replicative cellular senescence. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- KarakUlah, G.; Yandim, C. Signature changes in the expressions of protein-coding genes, lncRNAs, and repeat elements in early and late cellular senescence. Turk J. Biol. 2020, 44, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, O.; Tanizawa, H.; Kim, K.D.; Kossenkov, A.; Nacarelli, T.; Tashiro, S.; Majumdar, S.; Showe, L.C.; Zhang, R.; Noma, K.I. Involvement of condensin in cellular senescence through gene regulation and compartmental reorganization. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harr, J.C.; Luperchio, T.R.; Wong, X.; Cohen, E.; Wheelan, S.J.; Reddy, K.L. Directed targeting of chromatin to the nuclear lamina is mediated by chromatin state and A-type lamins. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 208, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Luperchio, T.R.; Wong, X.; Doan, E.B.; Byrd, A.T.; Roy Choudhury, K.; Reddy, K.L.; Krangel, M.S. A Lamina-Associated Domain Border Governs Nuclear Lamina Interactions, Transcription, and Recombination of the Tcrb Locus. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 1729–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cesarini, E.; Mozzetta, C.; Marullo, F.; Gregoretti, F.; Gargiulo, A.; Columbaro, M.; Cortesi, A.; Antonelli, L.; Di Pelino, S.; Squarzoni, S.; et al. Lamin A/C sustains PcG protein architecture, maintaining transcriptional repression at target genes. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 211, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marullo, F.; Cesarini, E.; Antonelli, L.; Gregoretti, F.; Oliva, G.; Lanzuolo, C. Nucleoplasmic Lamin A/C and Polycomb group of proteins: An evolutionarily conserved interplay. Nucleus 2016, 7, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohler, F.; Bormann, F.; Raddatz, G.; Gutekunst, J.; Corless, S.; Musch, T.; Lonsdorf, A.S.; Erhardt, S.; Lyko, F.; Rodriguez-Paredes, M. Epigenetic deregulation of lamina-associated domains in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worman, H.J.; Schirmer, E.C. Nuclear membrane diversity: Underlying tissue-specific pathologies in disease? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 34, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zullo, J.M.; Demarco, I.A.; Pique-Regi, R.; Gaffney, D.J.; Epstein, C.B.; Spooner, C.J.; Luperchio, T.R.; Bernstein, B.E.; Pritchard, J.K.; Reddy, K.L.; et al. DNA sequence-dependent compartmentalization and silencing of chromatin at the nuclear lamina. Cell 2012, 149, 1474–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Timp, W.; Feinberg, A.P. Cancer as a dysregulated epigenome allowing cellular growth advantage at the expense of the host. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Madakashira, B.P.; Sadler, K.C. DNA Methylation, Nuclear Organization, and Cancer. Front. Genet. 2017, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reddy, K.L.; Feinberg, A.P. Higher order chromatin organization in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2013, 23, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wen, B.; Wu, H.; Shinkai, Y.; Irizarry, R.A.; Feinberg, A.P. Large histone H3 lysine 9 dimethylated chromatin blocks distinguish differentiated from embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonald, O.G.; Wu, H.; Timp, W.; Doi, A.; Feinberg, A.P. Genome-scale epigenetic reprogramming during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011, 18, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, B.P.; Weisenberger, D.J.; Aman, J.F.; Hinoue, T.; Ramjan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Noushmehr, H.; Lange, C.P.; van Dijk, C.M.; Tollenaar, R.A.; et al. Regions of focal DNA hypermethylation and long-range hypomethylation in colorectal cancer coincide with nuclear lamina-associated domains. Nat. Genet. 2011, 44, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonald, O.G.; Li, X.; Saunders, T.; Tryggvadottir, R.; Mentch, S.J.; Warmoes, M.O.; Word, A.E.; Carrer, A.; Salz, T.H.; Natsume, S.; et al. Epigenomic reprogramming during pancreatic cancer progression links anabolic glucose metabolism to distant metastasis. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Nieto, P.E.; Schwartz, E.K.; King, D.A.; Paulsen, J.; Collas, P.; Herrera, R.E.; Morrison, A.J. Carcinogen susceptibility is regulated by genome architecture and predicts cancer mutagenesis. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 2829–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, L.B.; Nik-Zainal, S.; Wedge, D.C.; Aparicio, S.A.; Behjati, S.; Biankin, A.V.; Bignell, G.R.; Bolli, N.; Borg, A.; Borresen-Dale, A.L.; et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013, 500, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hodis, E.; Watson, I.R.; Kryukov, G.V.; Arold, S.T.; Imielinski, M.; Theurillat, J.P.; Nickerson, E.; Auclair, D.; Li, L.; Place, C.; et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell 2012, 150, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bersaglieri, C.; Santoro, R. Genome Organization in and around the Nucleolus. Cells 2019, 8, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Orsolic, I.; Jurada, D.; Pullen, N.; Oren, M.; Eliopoulos, A.G.; Volarevic, S. The relationship between the nucleolus and cancer: Current evidence and emerging paradigms. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2016, 37, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.L.; Poleshko, A.; Epstein, J.A. The nuclear periphery is a scaffold for tissue-specific enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 6181–6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, E.G.; Oldenburg, A.R.; Collas, P. Enriched Domain Detector: A program for detection of wide genomic enrichment domains robust against local variations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irianto, J.; Pfeifer, C.R.; Ivanovska, I.L.; Swift, J.; Discher, D.E. Nuclear lamins in cancer. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2016, 9, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, Y.; Vong, J.S.; Asafova, A.; Garvalov, B.K.; Caputo, L.; Cordero, J.; Singh, A.; Boettger, T.; Gunther, S.; Fink, L.; et al. Lamin B1 loss promotes lung cancer development and metastasis by epigenetic derepression of RET. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 1377–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, W.; Cai, J.; Ba, J.; Wang, Y.; Ke, Q.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Nuclear Nestin deficiency drives tumor senescence via lamin A/C-dependent nuclear deformation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, M.H.; Kang, S.M.; Lee, S.J.; Woo, T.G.; Oh, A.Y.; Park, S.; Ha, N.C.; Park, B.J. p53 induces senescence through Lamin A/C stabilization-mediated nuclear deformation. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Ao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Mo, Y.; Peng, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, B. Lamin A safeguards the m(6) A methylase METTL14 nuclear speckle reservoir to prevent cellular senescence. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, J.; Discher, D.E. The nuclear lamina is mechano-responsive to ECM elasticity in mature tissue. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 3005–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Swift, J.; Ivanovska, I.L.; Buxboim, A.; Harada, T.; Dingal, P.C.; Pinter, J.; Pajerowski, J.D.; Spinler, K.R.; Shin, J.W.; Tewari, M.; et al. Nuclear lamin-A scales with tissue stiffness and enhances matrix-directed differentiation. Science 2013, 341, 1240104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hutchison, C.J.; Worman, H.J. A-type lamins: Guardians of the soma? Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, N.D.; Cox, T.R.; Rahman-Casans, S.F.; Smits, K.; Przyborski, S.A.; van den Brandt, P.; van, E.M.; Weijenberg, M.; Wilson, R.G.; de, B.A.; et al. Lamin A/C is a risk biomarker in colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 2008, 20, e2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turgay, Y.; Eibauer, M.; Goldman, A.E.; Shimi, T.; Khayat, M.; Ben-Harush, K.; Dubrovsky-Gaupp, A.; Sapra, K.T.; Goldman, R.D.; Medalia, O. The molecular architecture of lamins in somatic cells. Nature 2017, 543, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naetar, N.; Ferraioli, S.; Foisner, R. Lamins in the nuclear interior-life outside the lamina. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 2087–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watabe, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Hatori, M.; Nishijima, Y.; Inoue, N.; Ikota, H.; Iwase, A.; Yokoo, H.; Saio, M. Role of Lamin A and emerin in maintaining nuclear morphology in different subtypes of ovarian epithelial cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2022, 23, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.S.; Shah, P.; Zuela-Sopilniak, N.; Kim, D.; McGregor, A.L.; Isermann, P.; Davidson, P.M.; Elacqua, J.J.; Lakins, J.N.; Vahdat, L.; et al. Low lamin A levels enhance confined cell migration and metastatic capacity in breast cancer. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittisopikul, M.; Shimi, T.; Tatli, M.; Tran, J.R.; Zheng, Y.; Medalia, O.; Jaqaman, K.; Adam, S.A.; Goldman, R.D. Computational analyses reveal spatial relationships between nuclear pore complexes and specific lamins. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202007082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohil, S.H.; Iorgulescu, J.B.; Braun, D.A.; Keskin, D.B.; Livak, K.J. Applying high-dimensional single-cell technologies to the analysis of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, D.; Ali, S.N.; Bhattacharya, A.; Mustafi, J.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Sengupta, K. A deep hybrid learning pipeline for accurate diagnosis of ovarian cancer based on nuclear morphology. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bellanger, A.; Madsen-Østerbye, J.; Galigniana, N.M.; Collas, P. Restructuring of Lamina-Associated Domains in Senescence and Cancer. Cells 2022, 11, 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11111846

Bellanger A, Madsen-Østerbye J, Galigniana NM, Collas P. Restructuring of Lamina-Associated Domains in Senescence and Cancer. Cells. 2022; 11(11):1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11111846

Chicago/Turabian StyleBellanger, Aurélie, Julia Madsen-Østerbye, Natalia M. Galigniana, and Philippe Collas. 2022. "Restructuring of Lamina-Associated Domains in Senescence and Cancer" Cells 11, no. 11: 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11111846

APA StyleBellanger, A., Madsen-Østerbye, J., Galigniana, N. M., & Collas, P. (2022). Restructuring of Lamina-Associated Domains in Senescence and Cancer. Cells, 11(11), 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11111846