The Molecular Interplay between Human Coronaviruses and Autophagy

Abstract

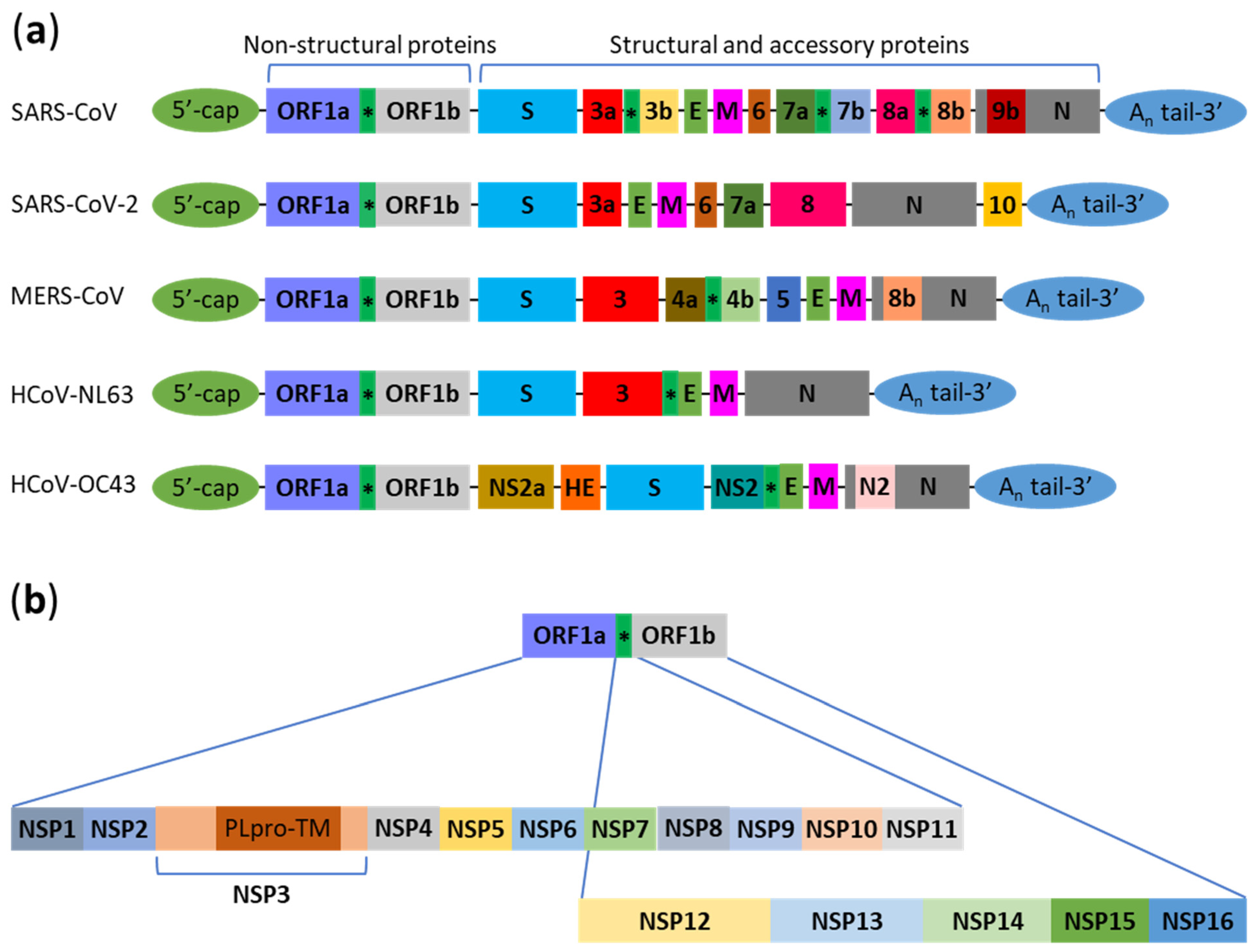

:1. Introduction

2. Interactions between Human Coronaviruses and Autophagy

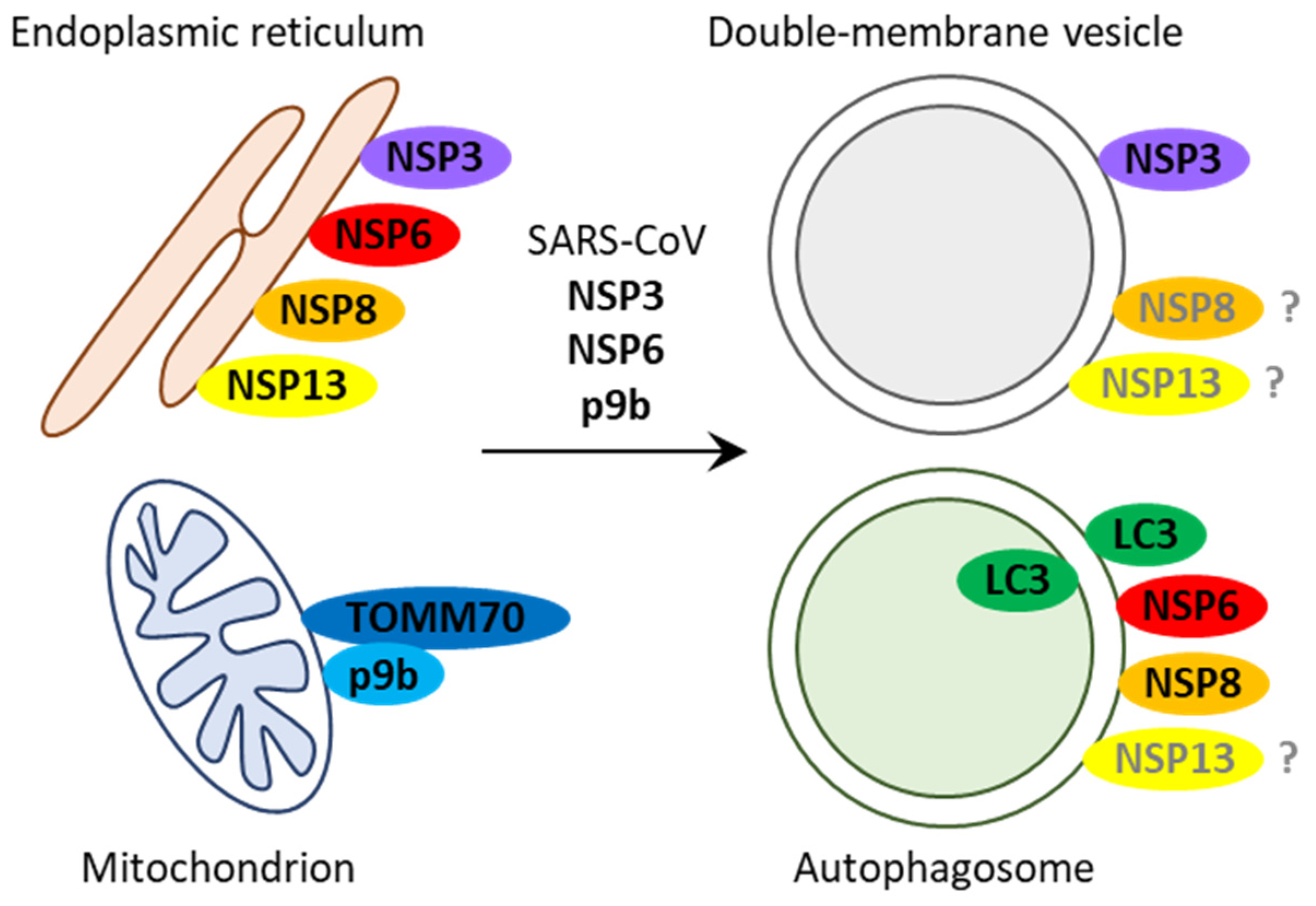

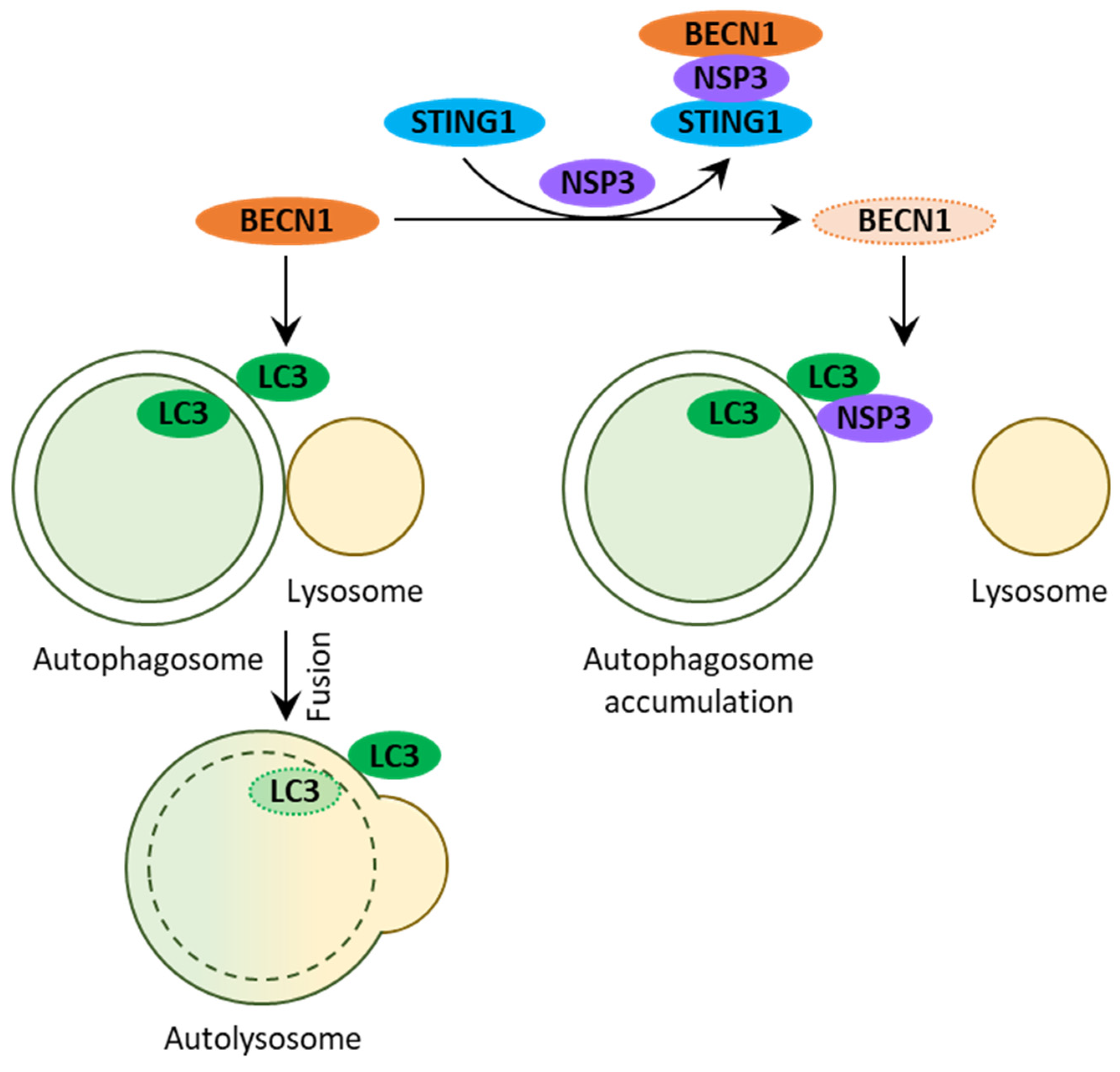

2.1. SARS-CoV

2.2. SARS-CoV-2

2.2.1. Early Interactions with Autophagy

2.2.2. Protein M Promotes Mitophagy

2.2.3. Protein 8 Causes Selective Autophagy of MHC-I Molecules

2.2.4. NSP15 Inhibits Autophagosome Formation

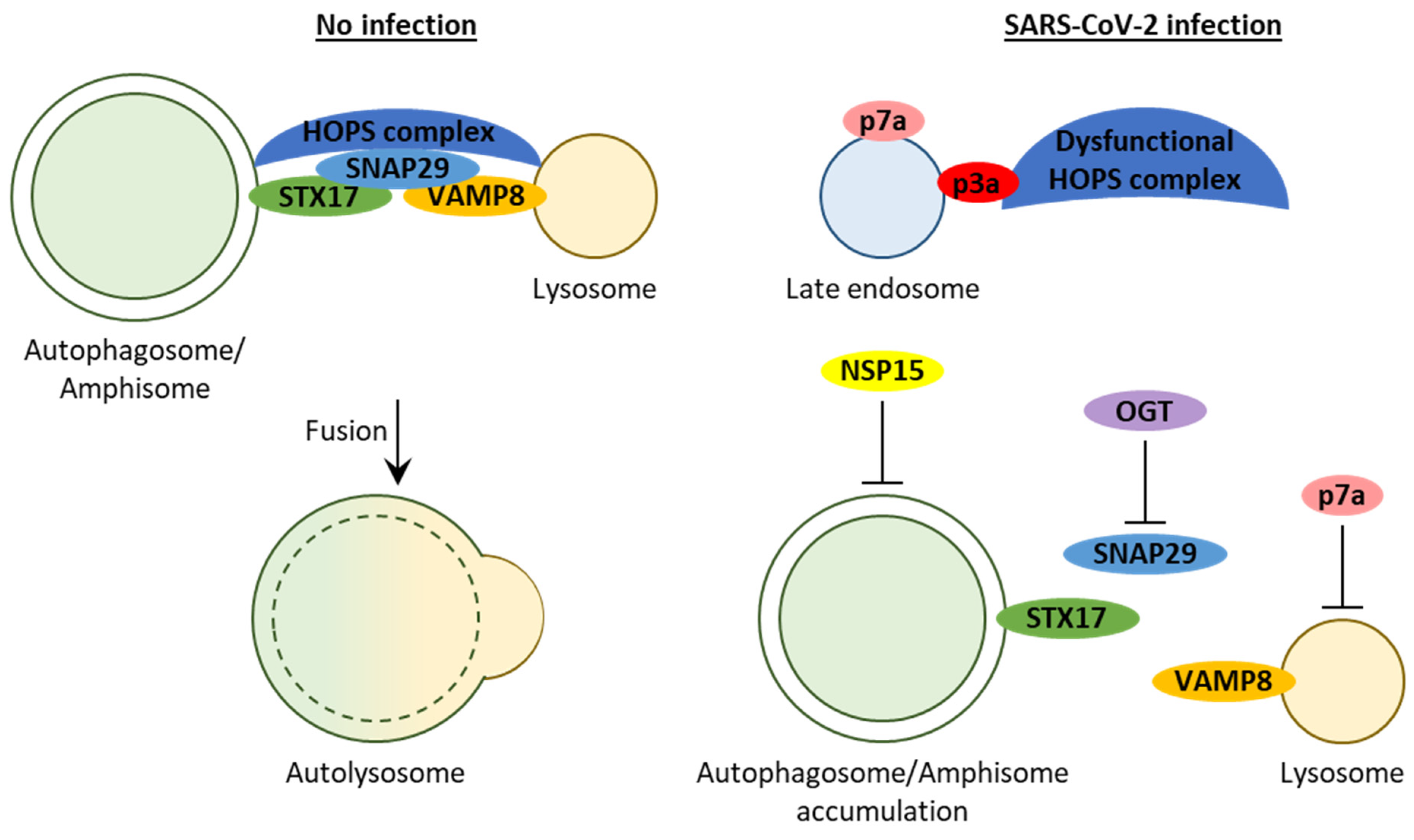

2.2.5. Proteins 3a, 7a, and E Block Autophagosome Turnover

2.2.6. Protein 3a Affects Autophagosome/Amphisome–Lysosome Fusion

2.2.7. Protein 7a Affects Lysosome Acidification

2.2.8. Polymorphism in Viral and Autophagic Genes

2.2.9. Clinical Relevance of Autophagic Markers

2.3. MERS-CoV

2.4. HCoV-NL63

2.5. HCoV-OC43

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klionsky, D.J.; Emr, S.D. Autophagy as a regulated pathway of cellular degradation. Science 2000, 290, 1717–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelsky, N.B.; Todd, P.K.; Taylor, J.P. Autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system: Collaborators in neuroprotection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1782, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anding, A.L.; Baehrecke, E.H. Cleaning House: Selective Autophagy of Organelles. Dev. Cell 2017, 41, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Levine, B.; Deretic, V. Unveiling the roles of autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravikumar, B.; Sarkar, S.; Davies, J.E.; Futter, M.; Garcia-Arencibia, M.; Green-Thompson, Z.W.; Jimenez-Sanchez, M.; Korolchuk, V.I.; Lichtenberg, M.; Luo, S.; et al. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 1383–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.G.; Zhang, H. Autophagosome maturation: An epic journey from the ER to lysosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, Y.M.; Flamholz, A.; Phillips, R.; Milo, R. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) by the numbers. eLife 2020, 9, e57309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.G.; Rambaut, A.; Lipkin, W.I.; Holmes, E.C.; Garry, R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrosillo, N.; Viceconte, G.; Ergonul, O.; Ippolito, G.; Petersen, E. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: Are they closely related? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Ye, G.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11727–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glebov, O.O. Understanding SARS-CoV-2 endocytosis for COVID-19 drug repurposing. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 3664–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.S.; Liu, D.X. Human Coronavirus: Host-Pathogen Interaction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 73, 529–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, Y.X.; Ng, Y.L.; Tam, J.P.; Liu, D.X. Human Coronaviruses: A Review of Virus-Host Interactions. Diseases 2016, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, J.S.; Lai, S.T.; Poon, L.L.; Guan, Y.; Yam, L.Y.; Lim, W.; Nicholls, J.; Yee, W.K.; Yan, W.W.; Cheung, M.T.; et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003, 361, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.Q.; Huang, T.; Wang, Y.Q.; Wang, Z.P.; Liang, Y.; Huang, T.B.; Zhang, H.Y.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y. COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Abe, A.; Abedin, M.J.; Abeliovich, H.; Acevedo Arozena, A.; Adachi, H.; Adams, C.M.; Adams, P.D.; Adeli, K.; et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy 2016, 12, 1–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, C.; Zheng, W.; Huang, X.; Bell, E.W.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Protein Structure and Sequence Reanalysis of 2019-nCoV Genome Refutes Snakes as Its Intermediate Host and the Unique Similarity between Its Spike Protein Insertions and HIV-1. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harcourt, B.H.; Jukneliene, D.; Kanjanahaluethai, A.; Bechill, J.; Severson, K.M.; Smith, C.M.; Rota, P.A.; Baker, S.C. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replicase products and characterization of papain-like protease activity. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 13600–13612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Wang, K.; Xing, Y.; Tu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Li, K.; Chen, Z. Coronavirus membrane-associated papain-like proteases induce autophagy through interacting with Beclin1 to negatively regulate antiviral innate immunity. Protein Cell 2014, 5, 912–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Devaraj, S.G.; Wang, N.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; Tseng, M.; Barretto, N.; Lin, R.; Peters, C.J.; Tseng, C.T.; Baker, S.C.; et al. Regulation of IRF-3-dependent innate immunity by the papain-like protease domain of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 32208–32221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cottam, E.M.; Maier, H.J.; Manifava, M.; Vaux, L.C.; Chandra-Schoenfelder, P.; Gerner, W.; Britton, P.; Ktistakis, N.T.; Wileman, T. Coronavirus nsp6 proteins generate autophagosomes from the endoplasmic reticulum via an omegasome intermediate. Autophagy 2011, 7, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cottam, E.M.; Whelband, M.C.; Wileman, T. Coronavirus NSP6 restricts autophagosome expansion. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1426–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prentice, E.; McAuliffe, J.; Lu, X.; Subbarao, K.; Denison, M.R. Identification and characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replicase proteins. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 9977–9986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Snijder, E.J.; van der Meer, Y.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.; Onderwater, J.J.; van der Meulen, J.; Koerten, H.K.; Mommaas, A.M. Ultrastructure and origin of membrane vesicles associated with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication complex. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5927–5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, C.S.; Qi, H.Y.; Boularan, C.; Huang, N.N.; Abu-Asab, M.; Shelhamer, J.H.; Kehrl, J.H. SARS-coronavirus open reading frame-9b suppresses innate immunity by targeting mitochondria and the MAVS/TRAF3/TRAF6 signalosome. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 3080–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stukalov, A.; Girault, V.; Grass, V.; Karayel, O.; Bergant, V.; Urban, C.; Haas, D.A.; Huang, Y.; Oubraham, L.; Wang, A.; et al. Multilevel proteomics reveals host perturbations by SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Nature 2021, 594, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Ackermann, K.; Stuart, M.; Wex, C.; Protzer, U.; Schatzl, H.M.; Gilch, S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication is severely impaired by MG132 due to proteasome-independent inhibition of M-calpain. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 10112–10122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kliche, J.; Kuss, H.; Ali, M.; Ivarsson, Y. Cytoplasmic short linear motifs in ACE2 and integrin beta3 link SARS-CoV-2 host cell receptors to mediators of endocytosis and autophagy. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, eabf1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.R.; To, R.K.; Hanna, J.; Spector, S.A. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-1, and HIV-1 derived ssRNA sequences activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages through a non-classical pathway. iScience 2021, 24, 102295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, X.; Zhang, L.; Cao, L.; Huang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Lin, X.; Chen, M.; Jin, M. SARS-CoV-2 promote autophagy to suppress type I interferon response. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, C.K.; Wong, W.M.; Mak, L.F.; Wang, X.; Chu, H.; Yuen, K.Y.; Kok, K.H. Suppression of SARS-CoV-2 infection in ex-vivo human lung tissues by targeting class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 2076–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, F.; Luo, B.; Yuan, Y.; Xia, B.; Ma, X.; Yang, T.; Yu, F.; et al. The ORF8 protein of SARS-CoV-2 mediates immune evasion through down-regulating MHC-I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2024202118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, J.L.G.; Wells, A.; Brufsky, A.M. Dysregulation of the mevalonate pathway during SARS-CoV-2 infection: An in-silico study. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 2396–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, S.; Dokic, J.; Stevanovic, D.; Ilic, N.; Gruden-Movsesijan, A.; Dinic, M.; Radojevic, D.; Bekic, M.; Mitrovic, N.; Tomasevic, R.; et al. Reduced Expression of Autophagy Markers and Expansion of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Correlate With Poor T Cell Response in Severe COVID-19 Patients. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 614599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayn, M.; Hirschenberger, M.; Koepke, L.; Nchioua, R.; Straub, J.H.; Klute, S.; Hunszinger, V.; Zech, F.; Prelli Bozzo, C.; Aftab, W.; et al. Systematic functional analysis of SARS-CoV-2 proteins uncovers viral innate immune antagonists and remaining vulnerabilities. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorshkov, K.; Chen, C.Z.; Bostwick, R.; Rasmussen, L.; Tran, B.N.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Xu, M.; Pradhan, M.; Henderson, M.; Zhu, W.; et al. The SARS-CoV-2 Cytopathic Effect Is Blocked by Lysosome Alkalizing Small Molecules. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 1389–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Luo, R.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Song, T.; Tao, T.; Li, Z.; Jin, L.; Zheng, H.; Chen, W.; et al. A cross-talk between epithelium and endothelium mediates human alveolar-capillary injury during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, G.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Ji, M.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Y.; Bi, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H. ORF3a of the COVID-19 virus SARS-CoV-2 blocks HOPS complex-mediated assembly of the SNARE complex required for autolysosome formation. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Pei, R.; Mao, B.; Zhao, Z.; Li, H.; Lin, Y.; Lu, K. The SARS-CoV-2 protein ORF3a inhibits fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Nabar, N.R.; Shi, C.-S.; Kamenyeva, O.; Xiao, X.; Hwang, I.-Y.; Wang, M.; Kehrl, J.H. SARS-Coronavirus Open Reading Frame-3a drives multimodal necrotic cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuto, D.; Angeletti, S.; Giovanetti, M.; Bianchi, M.; Pascarella, S.; Cauda, R.; Ciccozzi, M.; Cassone, A. Evolutionary analysis of SARS-CoV-2: How mutation of Non-Structural Protein 6 (NSP6) could affect viral autophagy. J. Infect. 2020, 81, e24–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayner, J.O.; Roberts, R.A.; Kim, J.; Poklepovic, A.; Roberts, J.L.; Booth, L.; Dent, P. AR12 (OSU-03012) suppresses GRP78 expression and inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 182, 114227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Xu, W.; Wu, W.; Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, R.; et al. Lysosome activation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and prognostic significance of circulating LC3B in COVID-19. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, 1466–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyan, H.M.; Dogan, S.; Bal, T.; Çabalak, M. Beclin-1, an autophagy-related protein, is associated with the disease severity of COVID-19. Life Sci. 2021, 278, 119596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassen, N.C.; Niemeyer, D.; Muth, D.; Corman, V.M.; Martinelli, S.; Gassen, A.; Hafner, K.; Papies, J.; Mosbauer, K.; Zellner, A.; et al. SKP2 attenuates autophagy through Beclin1-ubiquitination and its inhibition reduces MERS-Coronavirus infection. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.S.; Kim, D.E.; Jin, Y.H.; Kwon, S. Kurarinone Inhibits HCoV-OC43 Infection by Impairing the Virus-Induced Autophagic Flux in MRC-5 Human Lung Cells. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehote, G.; Vij, N. Autophagy Augmentation to Alleviate Immune Response Dysfunction, and Resolve Respiratory and COVID-19 Exacerbations. Cells 2020, 9, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Perez, B.E.; Gonzalez-Rojas, J.A.; Salazar, M.I.; Torres-Torres, C.; Castrejon-Jimenez, N.S. Taming the Autophagy as a Strategy for Treating COVID-19. Cells 2020, 9, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limanaqi, F.; Busceti, C.L.; Biagioni, F.; Lazzeri, G.; Forte, M.; Schiavon, S.; Sciarretta, S.; Frati, G.; Fornai, F. Cell Clearing Systems as Targets of Polyphenols in Viral Infections: Potential Implications for COVID-19 Pathogenesis. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonam, S.R.; Muller, S.; Bayry, J.; Klionsky, D.J. Autophagy as an emerging target for COVID-19: Lessons from an old friend, chloroquine. Autophagy 2020, 16, 2260–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brest, P.; Benzaquen, J.; Klionsky, D.J.; Hofman, P.; Mograbi, B. Open questions for harnessing autophagy-modulating drugs in the SARS-CoV-2 war: Hope or hype? Autophagy 2020, 16, 2267–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shroff, A.; Nazarko, T.Y. The Molecular Interplay between Human Coronaviruses and Autophagy. Cells 2021, 10, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10082022

Shroff A, Nazarko TY. The Molecular Interplay between Human Coronaviruses and Autophagy. Cells. 2021; 10(8):2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10082022

Chicago/Turabian StyleShroff, Ankit, and Taras Y. Nazarko. 2021. "The Molecular Interplay between Human Coronaviruses and Autophagy" Cells 10, no. 8: 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10082022

APA StyleShroff, A., & Nazarko, T. Y. (2021). The Molecular Interplay between Human Coronaviruses and Autophagy. Cells, 10(8), 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10082022