Fertilization Effects of Recycled Phosphorus with CaAl-LDH Under Controlled Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Cl-LDH and P-LDHs

2.2. Extraction of P from 10%P-LDH

2.3. Pot Trials

2.4. Analyses and Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

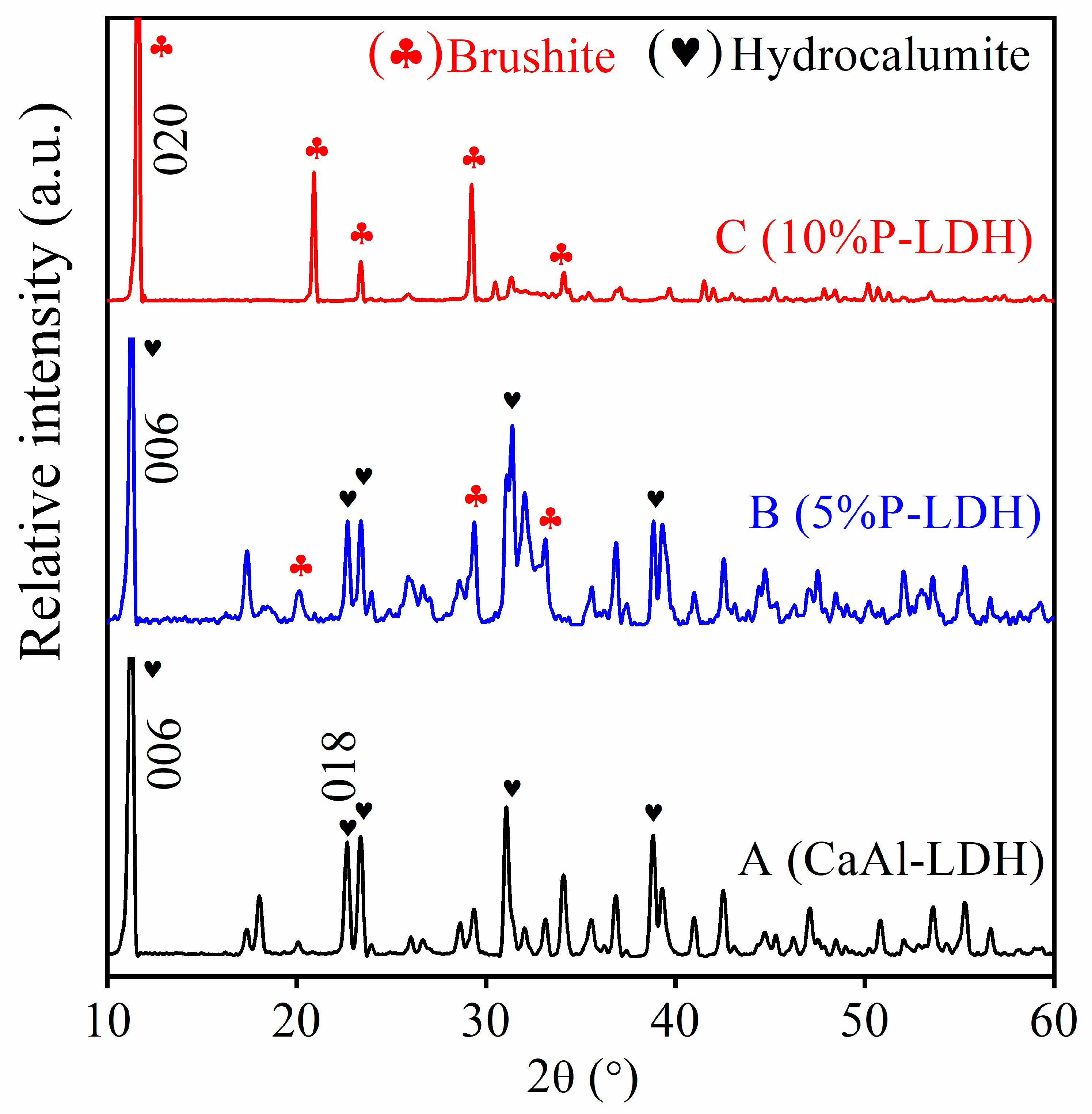

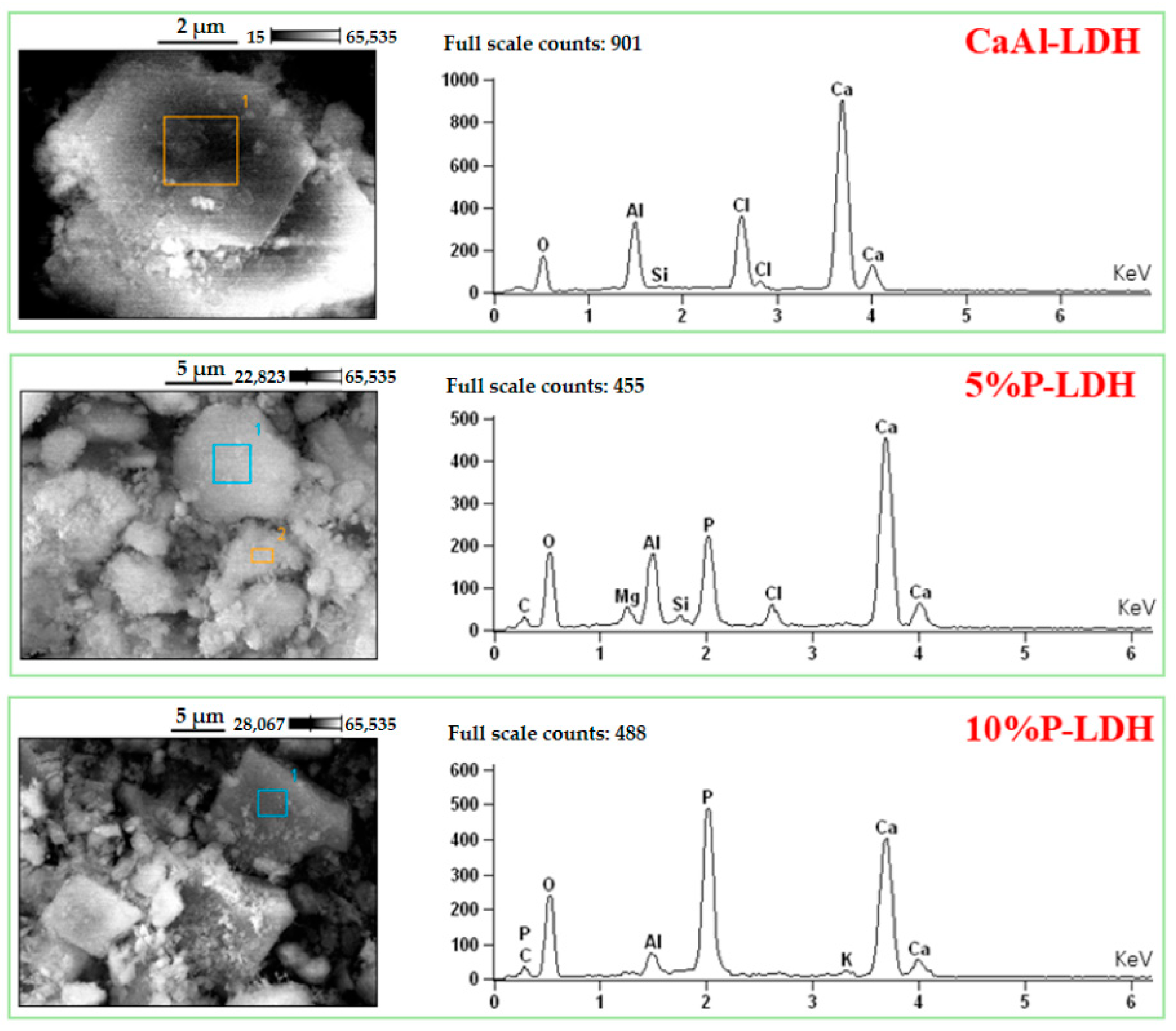

3.1. Main Components of Cl- and P-LDHs

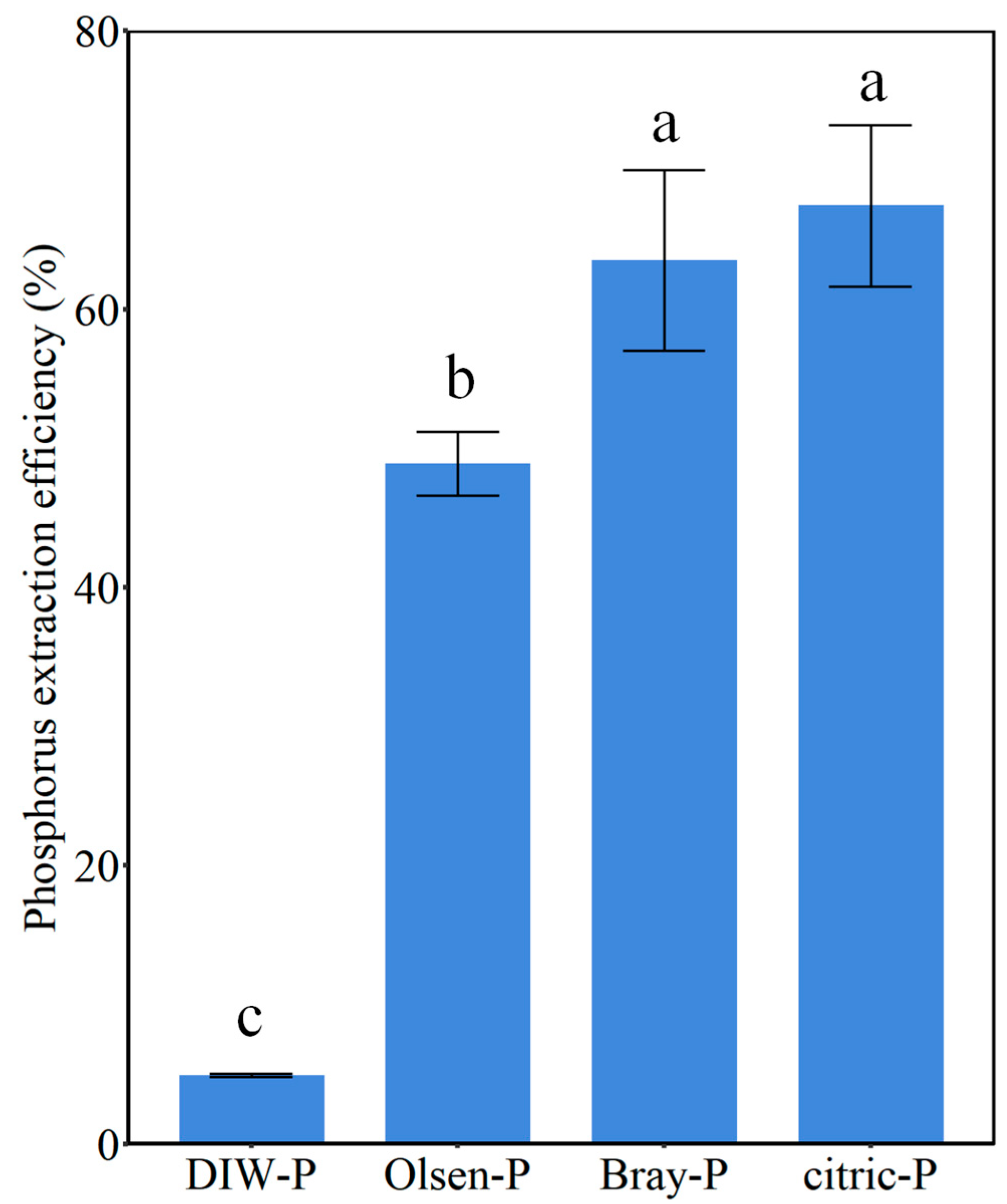

3.2. Evaluation of Available Phosphorus of 10%P-LDHs

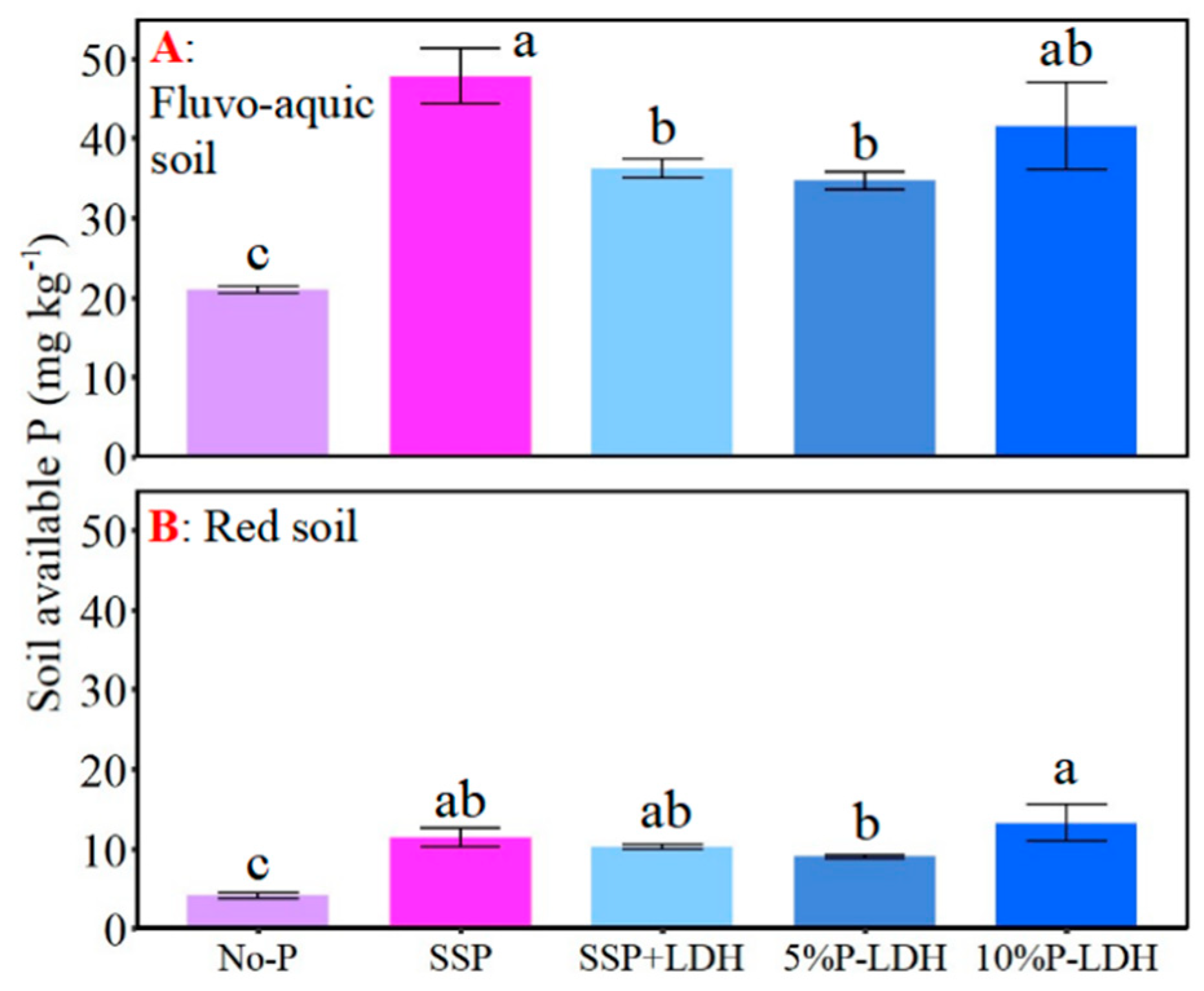

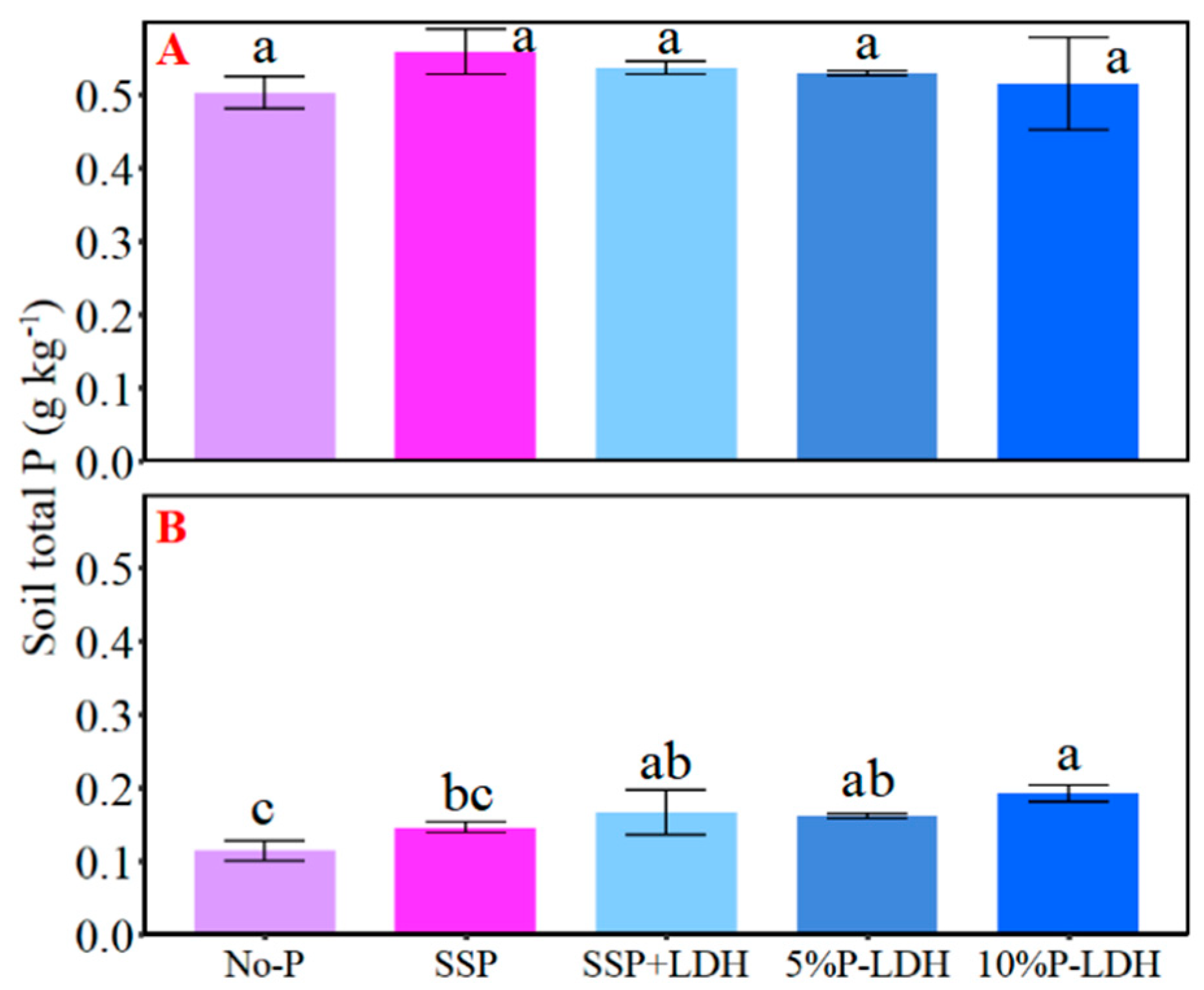

3.3. Effects of LDHs Application on Various Soil P Concentrations

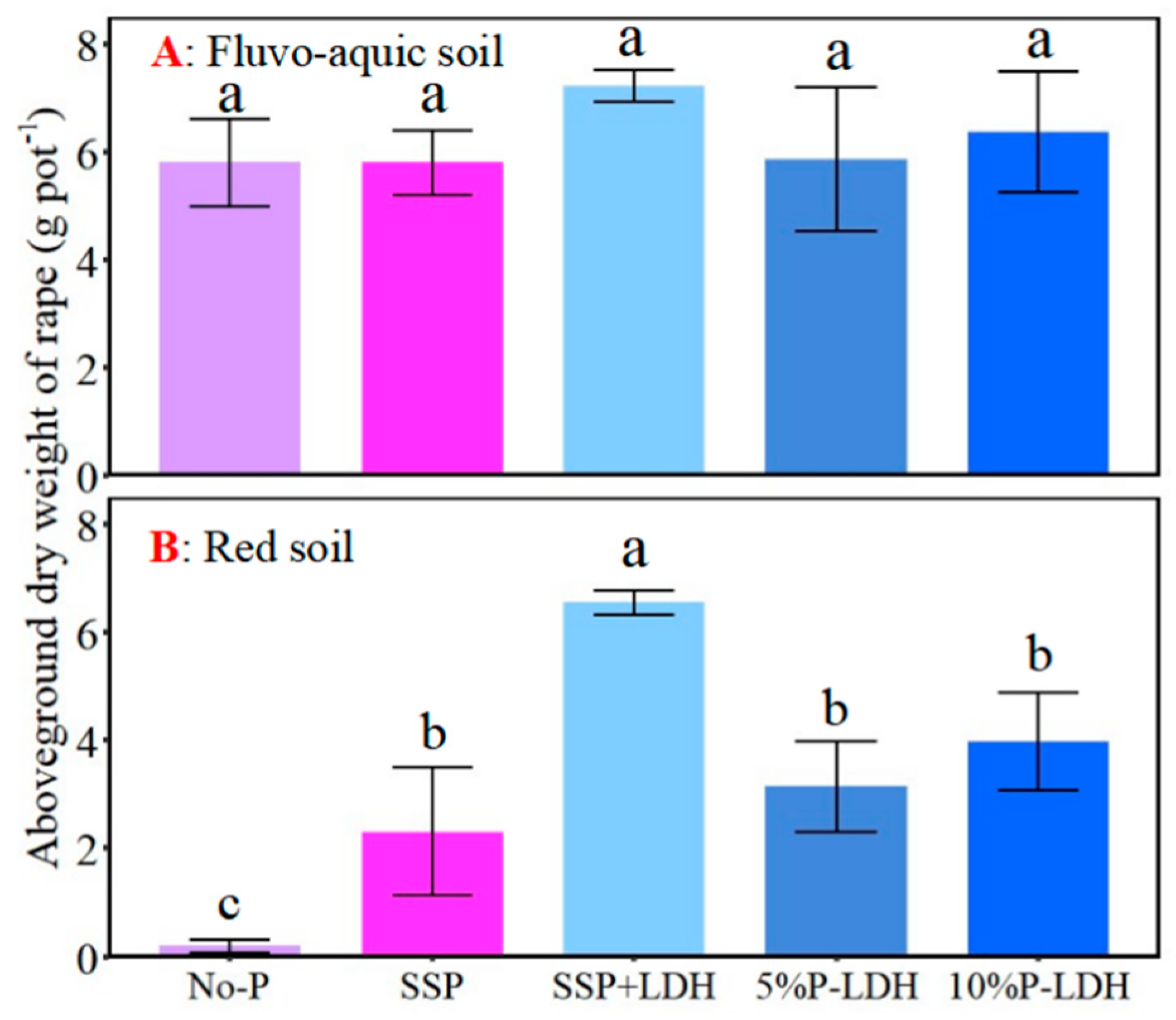

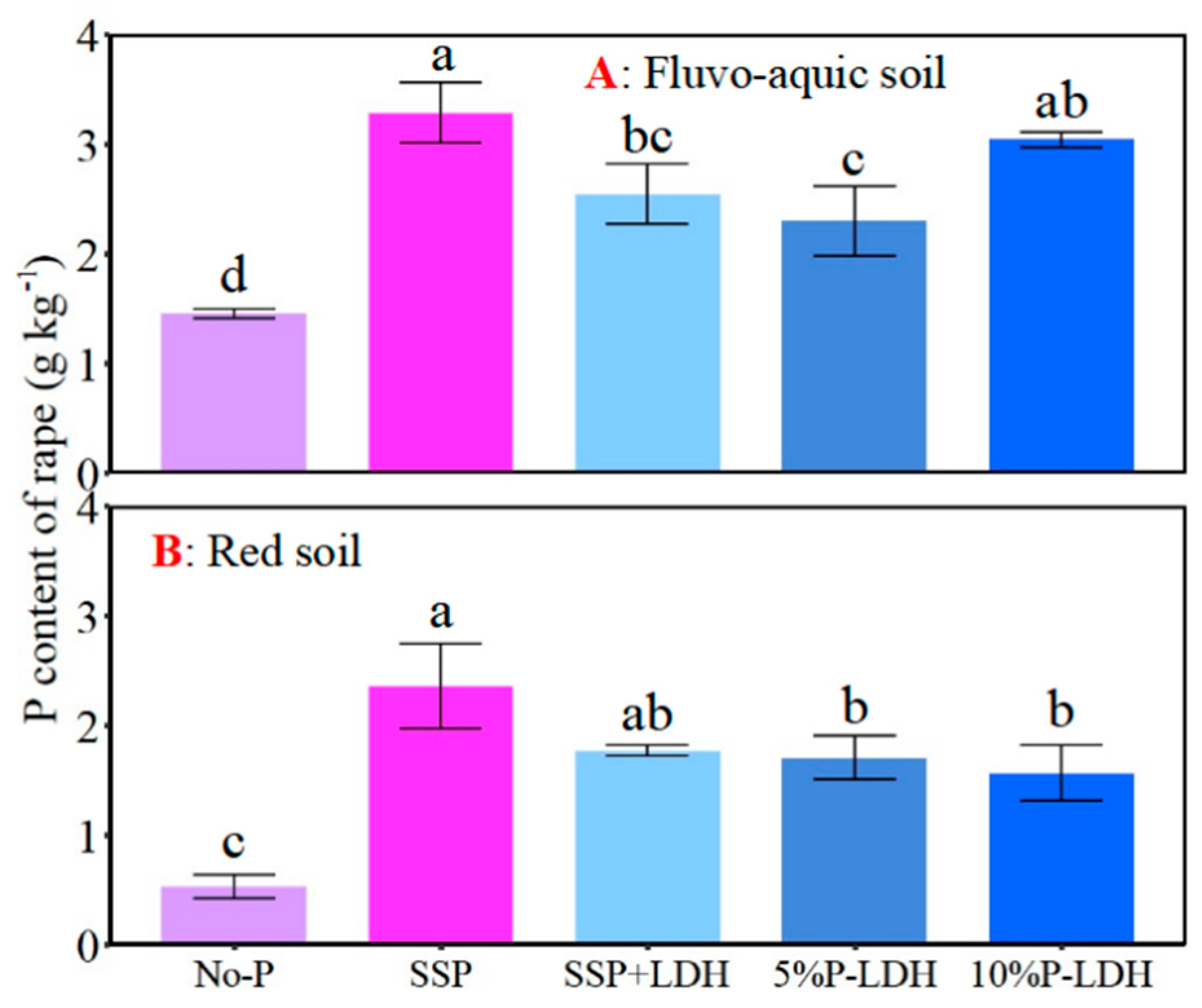

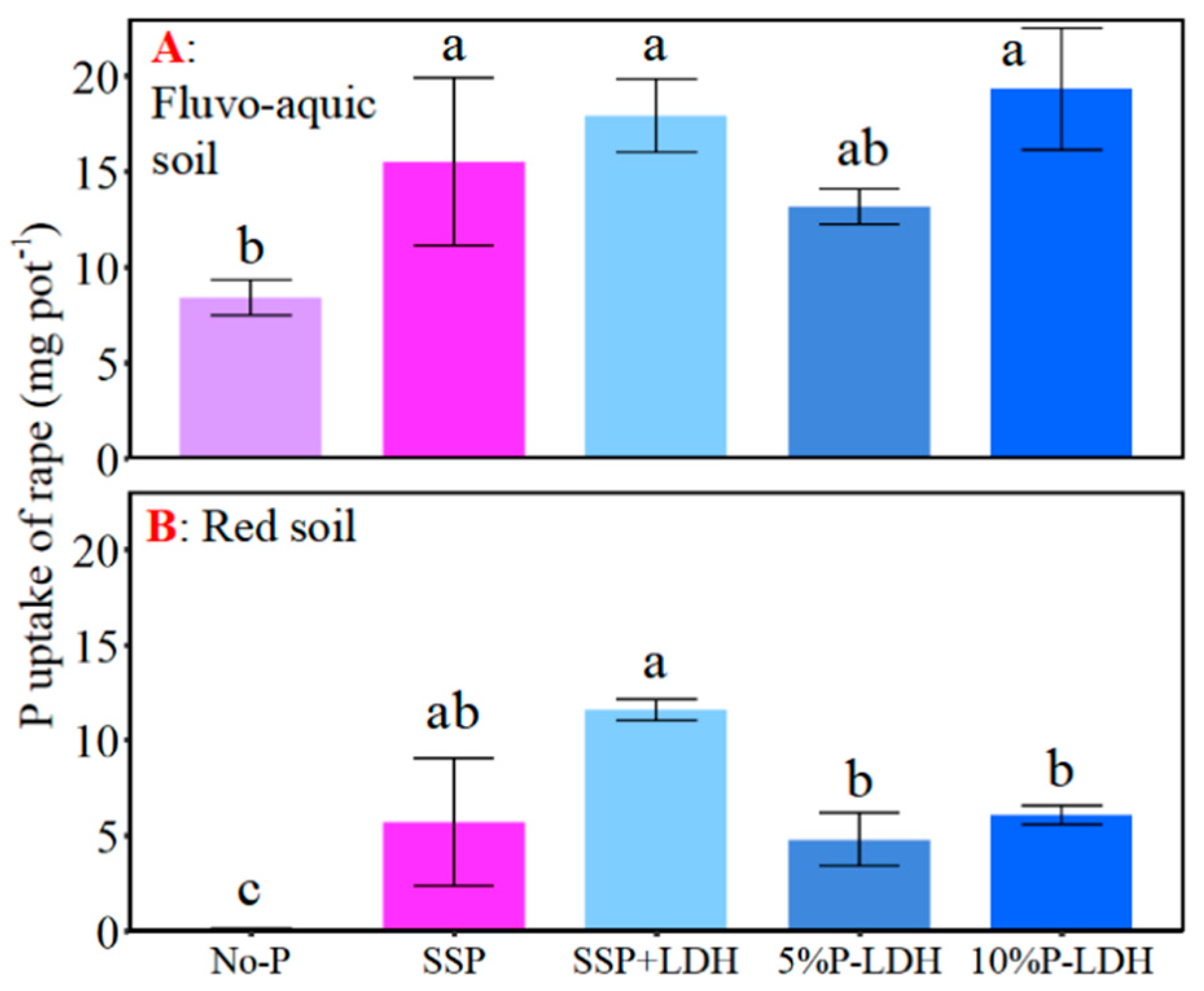

3.4. Effects of LDHs Application on Growth and P Uptake of Oilseed Rape

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, M.; Jiang, T.; Mao, Y.; Wang, F.; Yu, J.; Zhu, C. Current situation of agricultural non-point source pollution and its control. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Xia, Y.; Ti, C.; Shan, J.; Wu, Y.; Yan, X. Thirty years of experience in water pollution control in Taihu Lake: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Zhang, X.; Davidson, E.A. Global trends of cropland phosphorus use and sustainability challenges. Nature 2022, 611, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T.; Damtie, M.M.; Wang, C.Y.; Chen, Z.; Tao, Q.; Wei, W.; Cho, K.; Yuan, P.; Frost, R.L.; Ni, B.J. Comprehensive review of modified clay minerals for phosphate management and future prospects. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Huo, J.; Zhang, X.; Wen, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Kang, D.; Guo, W.; Ngo, H.H. Adsorption recovery of phosphorus in contaminated water by calcium modified biochar derived from spent coffee grounds. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Y. A review of methods, influencing factors and mechanisms for phosphorus recovery from sewage and sludge from municipal wastewater treatment plants. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, P.; Vigneswaran, S.; Kandasamy, J.; Bolan, N.S. Removal and Recovery of Phosphate from Water Using Sorption. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 44, 847–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.X.; Huang, Y.X.; Wu, Q.F.; Yao, W.; Lu, Y.Y.; Huang, B.C.; Jin, R.C. A review of the application of iron oxides for phosphorus removal and recovery from wastewater. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 54, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhang, W.; Dong, H.; Yu, Y.; Liu, W.; Luo, H.; Jing, Z.; Liang, B.; Peng, L.; Wu, B.; et al. Phosphorus removal from water by the layered double hydroxides (LDHs)-based adsorbents: A review for structure, mechanism, and current progress. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 37, 104003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattappan, D.; Kapoor, S.; Islam, S.S.; Lai, Y.T. Layered Double Hydroxides for Regulating Phosphate in Water to Achieve Long-Term Nutritional Management. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 24727–24749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, T.; Li, Q.; Lin, T.; Li, J.; Bai, S.; An, S.; Kong, X.; Song, Y.F. Recent progress on highly efficient removal of heavy metals by layered double hydroxides. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 462, 142041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Q.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, S. Recent progress on preparation and applications of layered double hydroxides. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 4428–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Yi, H.; Tang, X.; Yu, Q.; Gao, F.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Kang, D.; Zhao, S. Layered double hydroxides for air pollution control: Applications, mechanisms and trends. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 436, 140635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Liu, C.; Ke, Y. Chloride intercalated Ni-Al layered double hydroxide for effective adsorption removal of Sb(Ⅴ). Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 142, 109651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Singh, C.; Koranne, A.; Singh, S.; Azad, U.P.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, S.K. Layered Double Hydroxide: An Economical and Dynamic Choice for Water Remediation with Multiple Functionality. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202303300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquali, E.A.; Demaman Oro, C.E.; Bernardi, J.L.; Grass, G.B.; Venquiaruto, L.D.; Treichel, H.; Mossi, A.J.; Dallago, R.M. Exploring the adsorptive potential of layered double hydroxides for chromium(VI) remediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 9627–9636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Shi, H.; Lv, Q.; He, M.; Xu, Y.; Chen, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J. Enhanced adsorption effect of defect ordering Mg/Al on layered double hydroxides nanosheets with highly efficient removal of Congo red. Mater. Des. 2023, 232, 112084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Manzar, M.S.; El-Qanni, A.; Haroon, H.; Alqahtani, H.A.; Al-Ejji, M.; Mu’azu, N.D.; AlGhamdi, J.M.; Haladu, S.A.; Al-Hashim, D.; et al. Biochar-layered double hydroxide composites for the adsorption of tetracycline from water: Synthesis, process modeling, and mechanism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 109162–109180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduarahman, M.A.; Vuksanović, M.M.; Milošević, M.; Egelja, A.; Savić, A.; Veličković, Z.; Marinković, A. Mn-Fe Layered Double Hydroxide Modified Cellulose-Based Membrane for Sustainable Anionic Pollutant Removal. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 3776–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Yin, T.; Jia, X.; Chang, F.; Shi, Y.; Liu, H.; Xie, X.; Yang, Q.; Li, C.; Hu, G. Latest Progress and Perspectives in Layered Double Hydroxide-Based Adsorbents for Phosphate Pollution Removal from Wastewater. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e01025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everaert, M.; Degryse, F.; McLaughlin, M.J.; De Vos, D.; Smolders, E. Agronomic Effectiveness of Granulated and Powdered P-Exchanged Mg-Al LDH Relative to Struvite and MAP. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 6736–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, H.; Fotovat, A.; Halajnia, A. Availability and Uptake of Phosphorus and Zinc by Maize in the Presence of Phosphate-Containing Zn-Al-LDH in a Calcareous Soil. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2021, 54, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.S.; de Beer, M.; Pillai, S.K.; Ray, S.S. Application of Layered Double Hydroxides as a Slow-Release Phosphate Source: A Comparison of Hydroponic and Soil Systems. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 15017–15030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zheng, J.; Li, X.; Fan, C.; Zeng, R.; Tang, W. Phosphate adsorption by amino acids intercalated calcium aluminum hydrotalcites: Kinetic, isothermal and mechanistic studies. J. Solid State Chem. 2024, 329, 124428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Q.; Zhou, J. Kinetics, isotherms and multiple mechanisms of the removal for phosphate by Cl-hydrocalumite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 129, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, L.; Nan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sher, F.; Wang, C. Phosphorus recovery from wastewater by Ca-Al layered double hydroxide/biochar as potential agricultural phosphorus for closed-loop phosphorus recycling. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 194, 1538–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Luo, D.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C. Sustainable phosphorus recovery from wastewater by layered double hydroxide/biochar composites for potential agricultural application. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 224, 120422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhi, Y.Z.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhong, H.Y. Phosphate-adsorbed by concrete-based layered double hydroxide: A slow-release phosphate fertilizer. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 5191–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Ren, T.; Wang, K.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Lu, J. Improved crop yield and phosphorus uptake through the optimization of phosphorus fertilizer rates in an oilseed rape-rice cropping system. Field Crops Res. 2022, 286, 108614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; He, J.; Wei, M.; Evans, D.G.; Zhou, Z. Treatment of high fluoride concentration water by MgAl-CO3 layered double hydroxides: Kinetic and equilibrium studies. Water Res. 2007, 41, 1534–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, S.R.; Sommers, L.E. Phosphorus. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2 Chemical and Microbiological Properties; Page, A.L., Ed.; American Society of Agronomy, Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 403–430. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, R.H.; Kurtz, L.T. Determination of total, organic, and available forms of phosphorus in soils. Soil Sci. 1945, 59, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, M.; Jalali, M. Effect of low-molecular-weight organic acids on kinetics release and fractionation of phosphorus in some calcareous soils of western Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 5471–5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnon, D.I.; Hoagland, D.R. Crop production in artificial culture solutions and in soils with special reference of factors influencing yields and absorption of inorganic nutrients. Soil Sci. 1940, 50, 463–484. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R.K. Analysis Method of Soil Agricultural Chemistry; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, S.D. Soil Agriculture Chemical Elements Analysis; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alboukadel, K. rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests, Online. 2021. Available online: https://rdrr.io/cran/rstatix/ (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Field, A.; Miles, J.; Field, Z. Discovering Statistics Using R; SAFE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, J.; Xu, Z.P.; Qian, G.; Lu, G.Q.M. Removal efficiency of arsenate and phosphate from aqueous solution using layered double hydroxide materials: Intercalation vs. precipitation. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 4684–4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Feng, L.; Zhou, J.Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.P. Solubility product (Ksp)-controlled removal of chromate and phosphate by hydrocalumite. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 181, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundehoj, L.; Jensen, H.C.; Wybrandt, L.; Nielsen, U.G.; Christensen, M.L.; Quist-Jensen, C.A. Layered double hydroxides for phosphorus recovery from acidified and non-acidified dewatered sludge. Water Res. 2019, 153, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, W.O.; Mattiello, E.M.; Barreto, M.S.C.; Cantarutti, R.B. Acid Ammonium Citrate as P Extractor for Fertilizers of Varying Solubility. Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2019, 43, e0180072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, H.R.; Yang, R.; Robertson, I.J.; Doria, J.M.; Lewis, K.L.; Howe, J.A. Brushite: A Reclaimed Phosphorus Fertilizer for Agricultural Nutrient Fertilization. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 2085–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everaert, M.; Warrinnier, R.; Baken, S.; Gustafsson, J.-P.; De Vos, D.; Smolders, E. Phosphate-Exchanged Mg–Al Layered Double Hydroxides: A New Slow Release Phosphate Fertilizer. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 4280–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everaert, M.; Slenders, K.; Dox, K.; Smolders, S.; De Vos, D.; Smolders, E. The isotopic exchangeability of phosphate in Mg-Al layered double hydroxides. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 520, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, M.; Yan, B.; Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Guan, Y. Roles of Mg-Al layered double hydroxides and solution chemistry on P transport in soil. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 373, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourgholipour, F.; Mirseyed Hosseini, H.; Tehrani, M.M.; Motesharezadeh, B.; Moshiri, F. Comparison of phosphorus efficiency among spring oilseed rape cultivars in response to phosphorus deficiency. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2017, 46, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Santanen, A.; Jaakkola, S.; Ekholm, P.; Hartikainen, H.; Stoddard, F.L.; Mäkelä, P.S.A. Biomass yield and quality of bioenergy crops grown with synthetic and organic fertilizers. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 59, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lu, J.W.; Ren, T.; Li, X.K.; Cong, R.H. Effect of potassium application on adsorption of potassium, calcium and magnesium for direct-sowing winter rapeseed. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2015, 37, 336–343. [Google Scholar]

- Maillard, A.; Diquelou, S.; Billard, V.; Laine, P.; Garnica, M.; Prudent, M.; Garcia-Mina, J.M.; Yvin, J.C.; Ourry, A. Leaf mineral nutrient remobilization during leaf senescence and modulation by nutrient deficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Types | pH | Sand (%) | Slit (%) | Clay (%) | SOM (%) | CEC (cmol kg−1) | AN (mg kg−1) | AP (mg kg−1) | TP (g kg−1) | AK (mg kg−1) | TK (g kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluvo-aquic soil | 8.6 | 9.2 | 76.6 | 14.2 | 1.52 | 10.2 | 194 | 27.9 | 400 | 873 | 18.32 |

| Red soil | 4.8 | 43.9 | 48.2 | 7.9 | 1.68 | 11.2 | 79 | 3.9 | 85.3 | 1174 | 8.30 |

| Soil Type | Treatments | AFPU (mg pot−1) | CIs of AFPU | AFPUE (%) | CIs of AFPUE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluvo-aquic soil | SSP | 7.12 | (−3.21, 17.4) | 7.25 | (−3.27, 17.8) |

| SSP + LDH | 9.49 | (5.50, 13.5) | 9.67 | (5.60, 13.7) | |

| 5%P-LDH | 4.77 | (2.65, 6.88) | 4.85 | (2.70, 7.01) | |

| 10%P-LDH | 10.91 | (3.78, 18.0) | 11.11 | (3.85, 18.4) | |

| Red soil | SSP | 5.62 | (−2.67, 13.9) | 5.72 | (−2.72, 14.2) |

| SSP + LDH | 11.48 | (10.1, 12.8) | 11.69 | (10.3, 13.1) | |

| 5%P-LDH | 4.70 | (1.28, 8.12) | 4.78 | (1.30, 8.27) | |

| 10%P-LDH | 5.99 | (4.77, 7.22) | 6.11 | (4.86, 7.35) |

| Coefficients (r) | Soil pH | Soil Al | Soil Ca | Soil Fe | Soil K | Soil P | Plant Al | Plant Ca | Plant Fe | Plant K | Plant P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry weight | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.57 * | −0.52 | −0.80 *** | −0.51 | 0.09 | 0.47 |

| p value | 0.188 | 0.510 | 0.159 | 0.759 | 0.520 | 0.034 | 0.054 | 0.0006 | 0.064 | 0.750 | 0.090 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jia, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M.; Liu, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, H. Fertilization Effects of Recycled Phosphorus with CaAl-LDH Under Controlled Conditions. Agronomy 2026, 16, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030385

Jia Y, Wang L, Huang S, Chen Y, Liu M, Liu F, Zhang J, Zhang J, Yang L, Wang H. Fertilization Effects of Recycled Phosphorus with CaAl-LDH Under Controlled Conditions. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030385

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Yunsheng, Liangkai Wang, Sijie Huang, Yun Chen, Mingqing Liu, Fei Liu, Jianyu Zhang, Jibing Zhang, Lifei Yang, and Huoyan Wang. 2026. "Fertilization Effects of Recycled Phosphorus with CaAl-LDH Under Controlled Conditions" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030385

APA StyleJia, Y., Wang, L., Huang, S., Chen, Y., Liu, M., Liu, F., Zhang, J., Zhang, J., Yang, L., & Wang, H. (2026). Fertilization Effects of Recycled Phosphorus with CaAl-LDH Under Controlled Conditions. Agronomy, 16(3), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030385