Online Monitoring of Aerodynamic Characteristics of Fruit Tree Leaves Based on Strain-Gage Sensors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

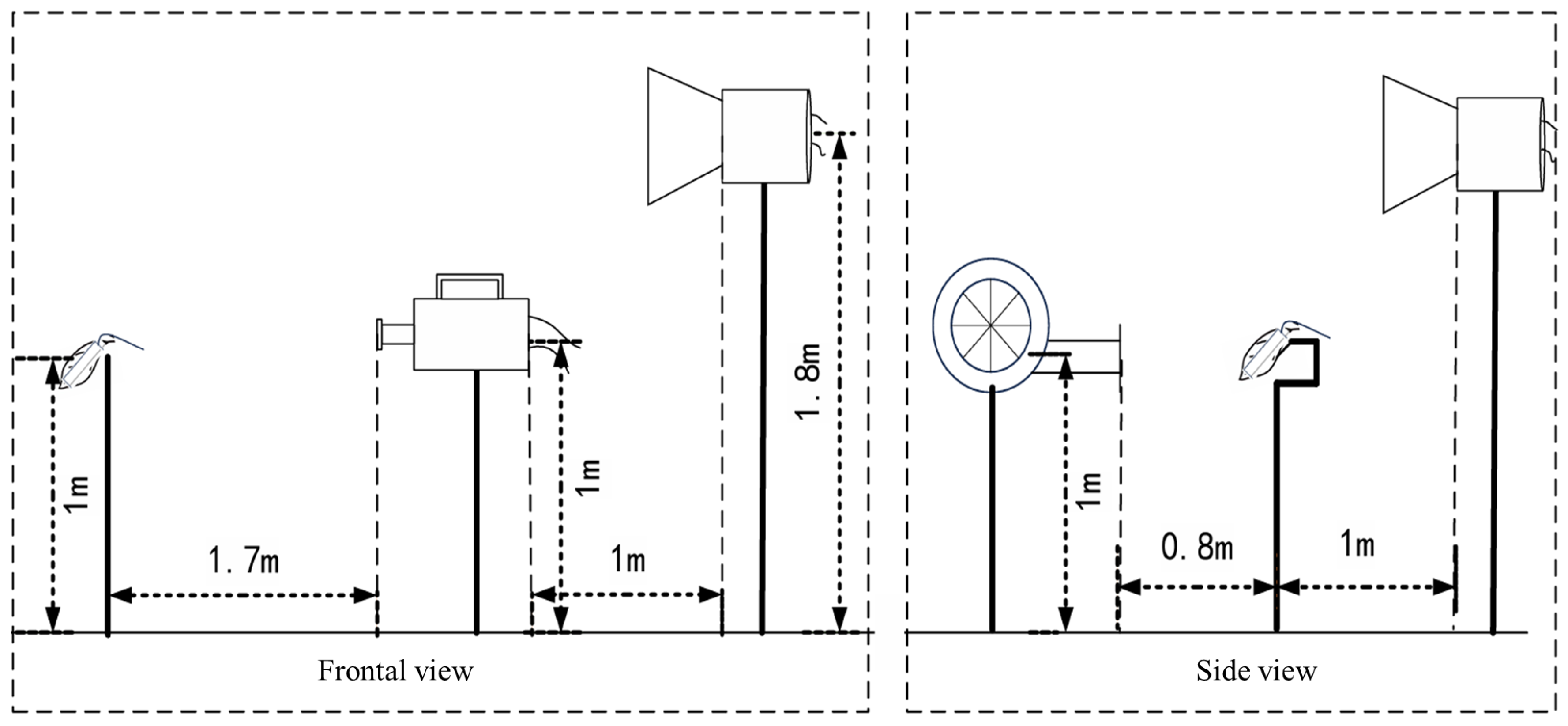

2.1. Test Bench Configuration

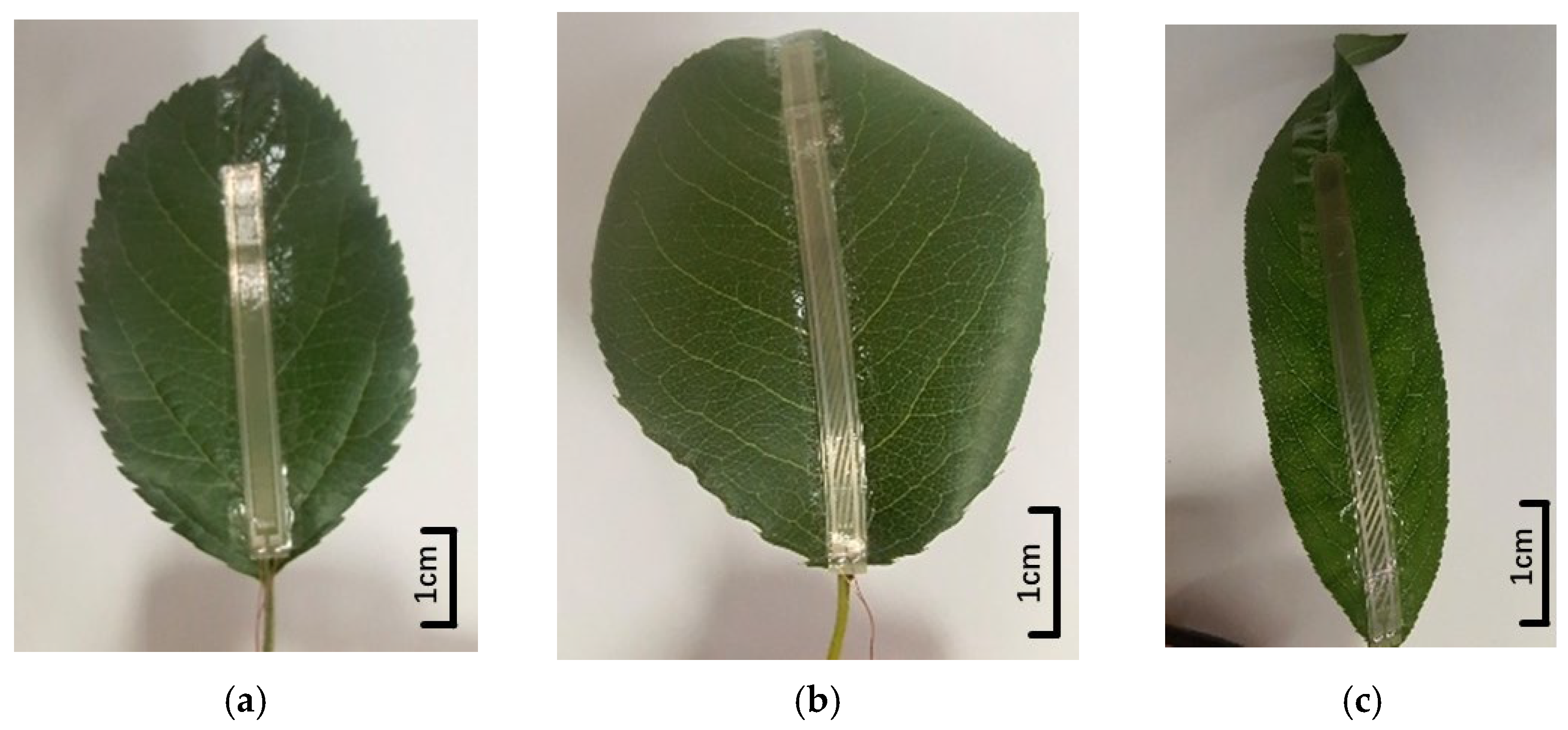

2.2. Preprocessing of Tree Leaves

2.3. Acquisition of Tree Leaf Movement Data

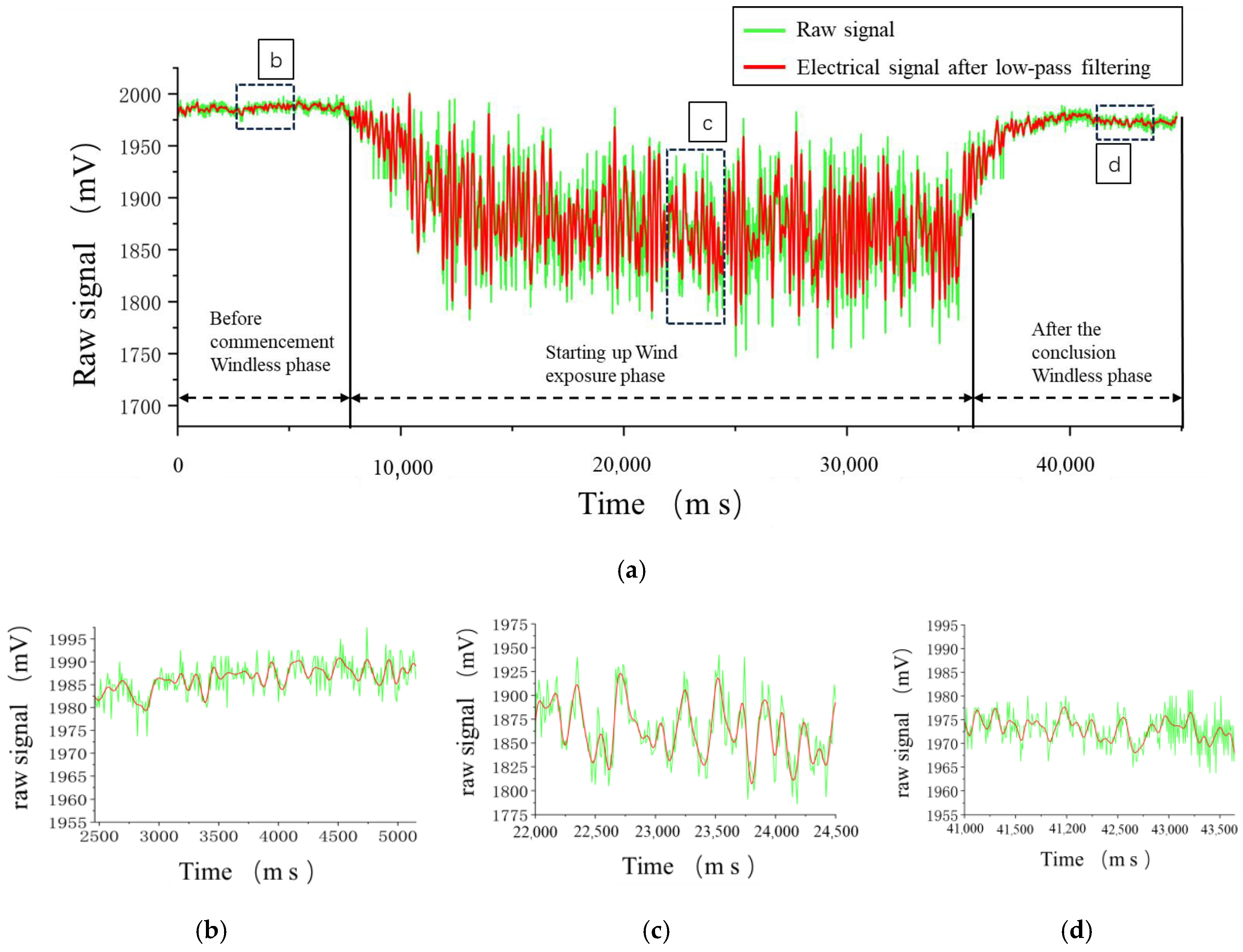

2.4. Strain Gauge Sensor Data Signal Processing and Analysis

2.5. Establishment of Multi-Species Joint Identification Model

2.6. Verification of Continuous Signal

3. Results

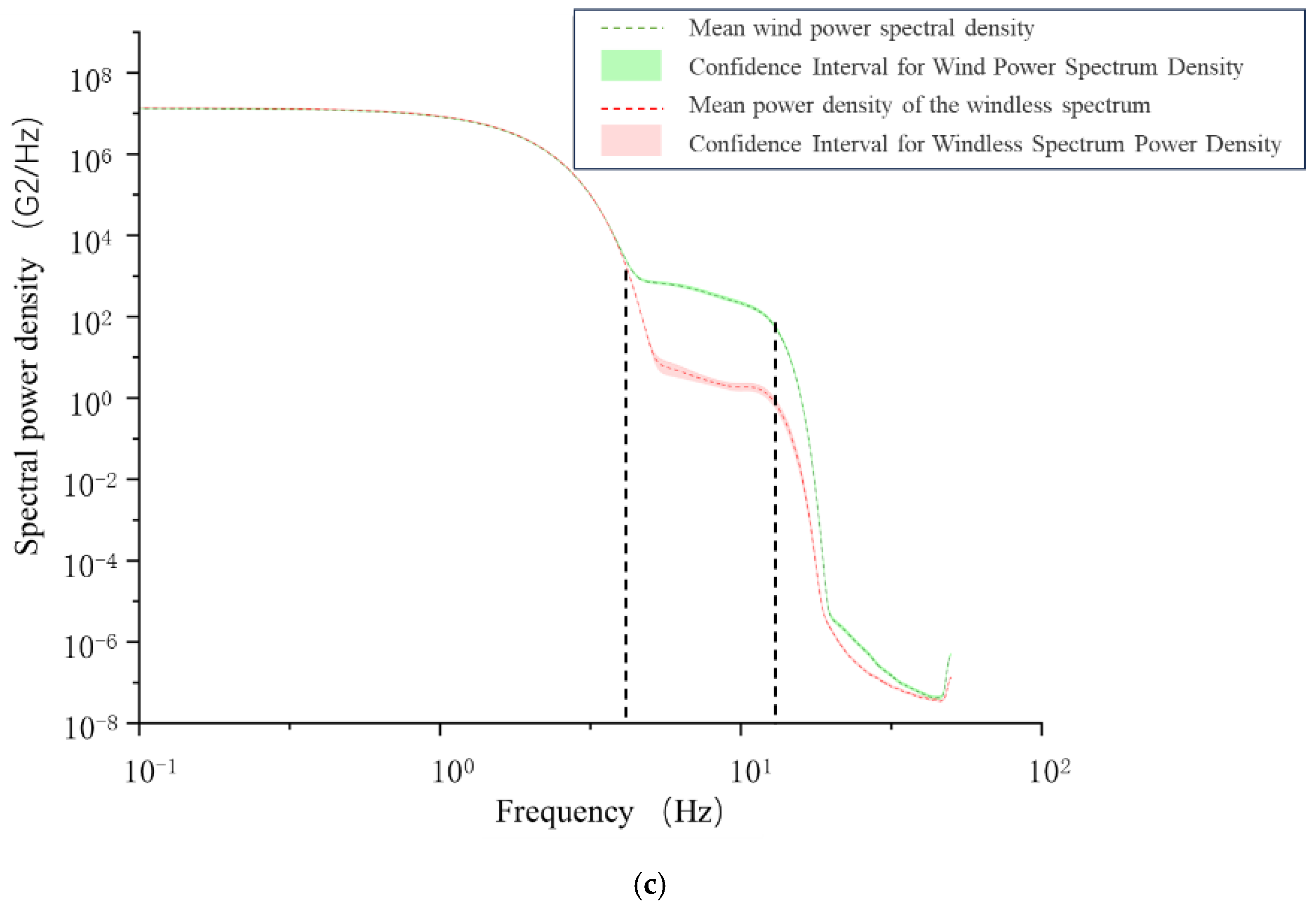

3.1. Strain Gauge Sensor Data Signal Processing Analysis

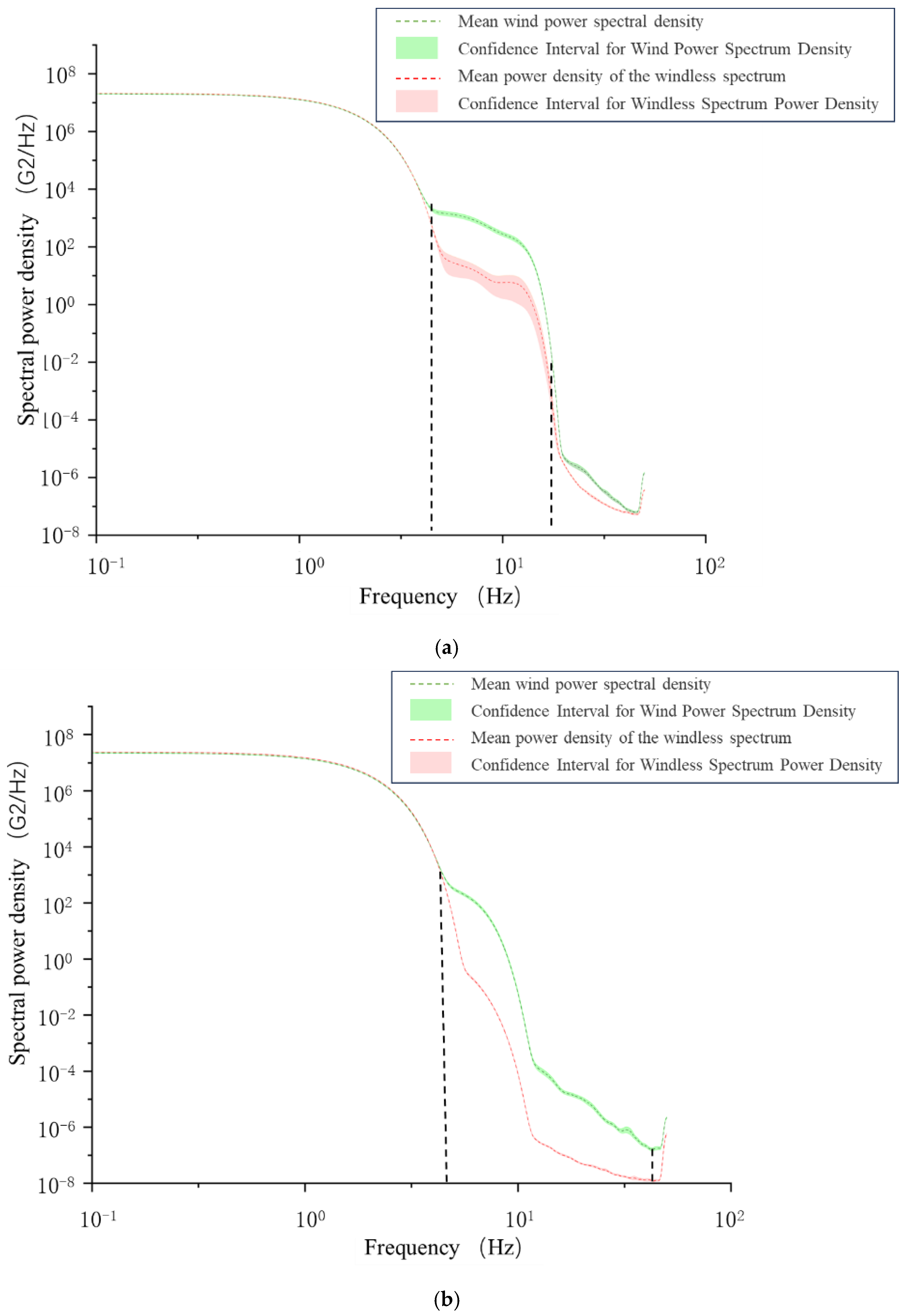

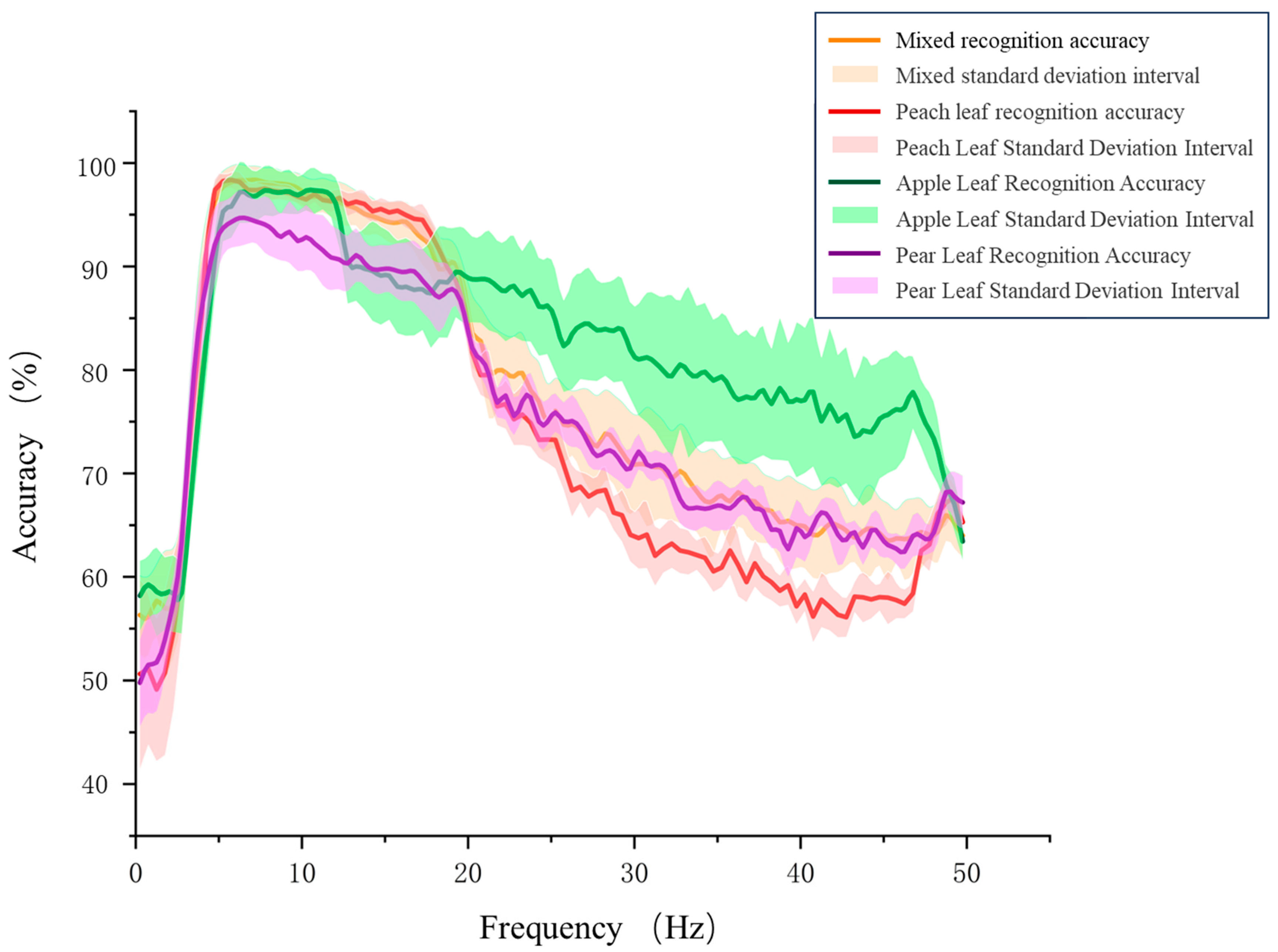

3.2. Optimal Classification Frequency Bands for Multi-Species Leaves

3.3. Construction of a Multi-Species Joint Identification Model

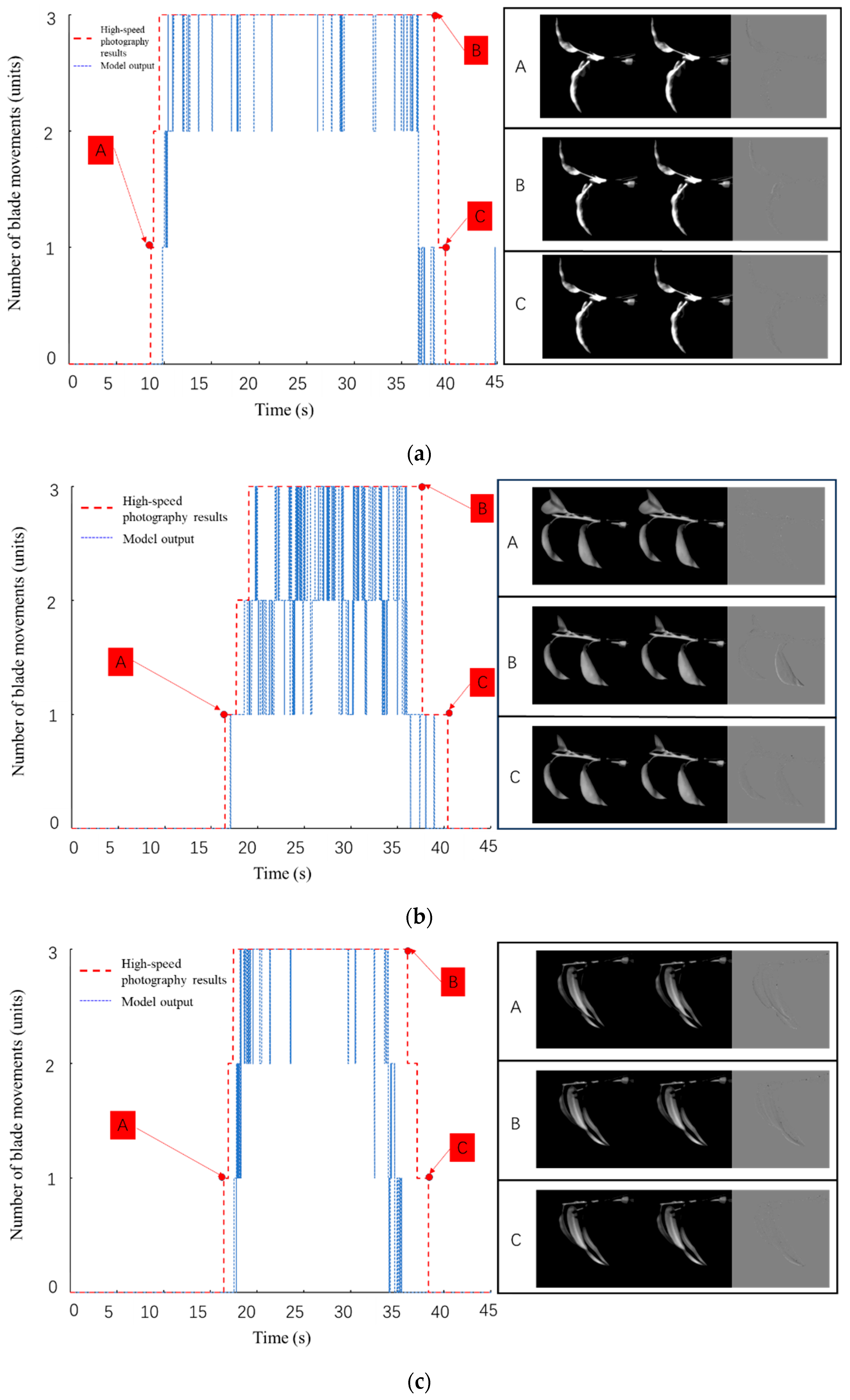

3.4. Temporal Verification of Continuous Signal Prediction Results

3.5. Time of Deviation in Multi-Species Joint Model Prediction Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tudi, M.; Ruan, H.D.; Wang, L.; Lyu, J.; Sadler, R.; Connell, D.; Chu, C.; Phung, D.T. Agriculture Development, Pesticide Application and Its Impact on the Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grella, M.; Gioelli, F.; Marucco, P.; Zwertvaegher, I.; Mozzanini, E.; Mylonas, N.; Nuyttens, D.; Balsari, P. Field Assessment of a Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) Spray System Applying Different Spray Volumes: Duty Cycle and Forward Speed Effects on Vines Spray Coverage. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 219–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Yang, S.; Zou, W.; Zhai, C. Deposition Characteristics of Air-Assisted Sprayer Based on Canopy Volume and Leaf Area of Orchard Trees. Plants 2025, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, L.; Garcia-Ruiz, F.; Fabregas, F.X.; Gil, E. Pesticide Dose Based on Canopy Characteristics in Apple Trees: Reducing Environmental Risk by Reducing the Amount of Pesticide While Maintaining Pest and Disease Control Efficacy. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Yuan, J.; Song, L.; Li, H.; Wu, M. Estimation Model of Canopy Stratification Porosity Based on Morphological Characteristics: A Case Study of Cotton. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 193, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, R.; Chen, L.; Hewitt, A.J.; He, X.; Ding, C.; Tang, Q.; Liu, B. Toward a Remote Sensing Method Based on Commercial LiDAR Sensors for the Measurement of Spray Drift and Potential Drift Reduction. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, W.; Guo, H.; Cao, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Z. An Electrical Vortex Air-Assisted Spraying System for Improving Droplet Deposition on Rice. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 4037–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Xin, D.; Zhang, H. Wind-Tunnel Study of the Aerodynamic Characteristics and Mechanical Response of the Leaves of Betula platyphylla Sukaczev. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 207, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, M.; Cui, H.; Lin, P.; Chen, Y.; Ling, G.; Huang, G.; Fu, H. Characterizing Droplet Retention in Fruit Tree Canopies for Air-Assisted Spraying. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.-M.; Hu, W.; Dong, X.-Y.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, J.; Qiu, B.-J. Motion Behavior of Droplets on Curved Leaf Surfaces Driven by Airflow. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1450831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhai, C.; Gu, C.; Zheng, K.; Li, X.; Jiang, R.; Xiao, K. Modeling of Droplet Deposition in Air-Assisted Spraying. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Luo, X.; Wang, P.; Zhou, Z.; O’Donnell, C.C.; Zang, Y.; Hewitt, A.J. Analysis of the Influence of Different Parameters on Droplet Characteristics and Droplet Size Classification Categories for Air Induction Nozzle. Agronomy 2020, 10, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Qi, P.; Wang, Z.; Xu, S.; Huang, Z.; Han, L.; He, X. Evaluation of the Effects of Airflow Distribution Patterns on Deposit Coverage and Spray Penetration in Multi-Unit Air-Assisted Sprayer. Agronomy 2022, 12, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Ren, N.; Liu, S.; Shao, M.; Jiang, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, L.; Zhang, W. An Improved Hierarchical Leaf Density Model for Spatio-Temporal Distribution Characteristic Analysis of UAV Downwash Air-Flow in a Fruit Tree Canopy. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, H.; Fang, S.; Cao, B. Investigation of Airflow Attenuation in Orchard Air-Assisted Spraying Based on Crown Characteristics. Agriculture 2025, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, H.; Xu, L.; Ru, Y.; Ju, H.; Chen, Q. Measurement of Morphological Changes of Pear Leaves in Airflow Based on High-Speed Photography. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 900427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, C.; Niu, C.; Ma, S.; Tan, H.; Xu, L. CFD Models as a Tool to Analyze the Deformation Behavior of Grape Leaves under an Air-Assisted Sprayer. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Hanif, A.S.; Yu, S.-H.; Lee, C.-G.; Kang, Y.H.; Lee, D.-H.; Han, X. Development of an Autonomous Drone Spraying Control System Based on the Coefficient of Variation of Spray Distribution. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Jiang, X.; Hu, Q.; Zheng, H.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, L. Wind Speed and Direction Measurement Method and System Based on Cylindrical Pitot Tube Array. In Proceedings of the 11th Frontier Academic Forum of Electrical Engineering (FAFEE2024), Chongqing, China, 20–22 June 2024; Yang, Q., Li, J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 863–870. [Google Scholar]

- Lundström, H. Investigation of Heat Transfer from Thin Wires in Air and a New Method for Temperature Correction of Hot-Wire Anemometers. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2021, 128, 110403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiyang, L.; Jiali, C.; Zhanfeng, H.; Zhi, C.; Chuanzhong, X.; Xiaobin, S. Investigation on Near-Surface Wireless Wind Speed Profiler Based on Thermistors. J. Agric. Mach. 2017, 48, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, G.; Gao, W.; Sun, H.; Liu, G.; Wu, Y.; Shi, Y. A Novel Ultrasonic Array Signal Processing Scheme for Wind Measurement. ISA Trans. 2018, 81, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiu, E.M.; Qi, L.; Wu, Y. Spray Deposition and Distribution on the Targets and Losses to the Ground as Affected by Application Volume Rate, Airflow Rate and Target Position. Crop Prot. 2019, 116, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y.; Cui, H.; Yang, Z.; Lu, H. Effects of Leaf Response Velocity on Spray Deposition with an Air-Assisted Orchard Sprayer. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yu, W.; Ou, M.; Gong, C.; Jia, W. Monitoring of the Pesticide Droplet Deposition with a Novel Capacitance Sensor. Sensors 2019, 19, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Qi, L.; Zhang, H.; Musiu, E.M.; Yang, Z.; Wang, P. Design of UAV Downwash Airflow Field Detection System Based on Strain Effect Principle. Sensors 2019, 19, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, F.; Tang, W.; Jianping, S.; Yang, J.; Zhu, L. A Review of Flexible Force Sensors for Human Health Monitoring. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 26, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Hao, D.; Wang, R. The Motion of Strawberry Leaves in an Air-Assisted Spray Field and Its Influence on Droplet Deposition. Trans. ASABE 2021, 64, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dong, X.; Jia, W.; Ou, M.; Yu, P.; Wu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, X.; Huang, Y.; Lu, F. Influence of Wind Speed on the Motion Characteristics of Peach Leaves (Prunus persica). Agriculture 2024, 14, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Luo, L.; Jin, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Song, J. Application of Leaf Attitude Sensor Systems in Air-Assisted Spraying Operation in Cowpea and Citrus. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 257, 104232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Sun, H.; Qiu, W.; Lv, X.; Ahmad, F.; Gu, J.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Z. Analysing Airflow Velocity in the Canopy to Improve Droplet Deposition for Air-Assisted Spraying: A Case Study on Pears. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Peach Leaves | Pear Leaves | Apple Leaves |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fan voltage value (V) | 0, 1.6, 3.4, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 | 0, 1.9, 3.4, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 | 0, 1.5, 3.4, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 |

| Air Outlet Velocity (m/s) | 0, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16 | 0, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16 | 0, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16 |

| Strain Gauge Specifications (AA) | 80AA | 80AA | 50AA |

| Number of readings per strain gauge set (times) | 21 (0, 1.5, 3.4, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) | 21 (0, 1.5, 3.4, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) | 21 (0, 1.5, 3.4, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) |

| Strain gauge + high-speed photography Number of acquisitions per set (times) | 12 times (1.6, 3.4, 4, 5, 7, 9) | 19 times (1.9, 3.4, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) | 19 times (1.5, 3.4, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) |

| Total number of collections (times) | 204 | 225 | 225 |

| Total number of single-leaf samplings (times) | 612 | 675 | 675 |

| Category | Peach Leaves | Apple Leaves | Pear Leaves | MIX |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 0.98 ± 0.002 | 0.97 ± 0.002 | 0.94 ± 0.002 | 0.99 ± 0.002 |

| Recall | 0.99 ± 0.002 | 0.97 ± 0.002 | 0.94 ± 0.002 | 0.99 ± 0.002 |

| Precision | 0.97 ± 0.002 | 0.97 ± 0.002 | 0.95 ± 0.002 | 0.98 ± 0.002 |

| kappa | 0.97 ± 0.002 | 0.95 ± 0.002 | 0.88 ± 0.002 | 0.98 ± 0.002 |

| Category | Group | Apple Leaves | Pear Leaves | Peach Leaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First single-leave movement time deviation. (Point A) | 0–3 m/s | - | 3.546 | 23.905 |

| 3–6 m/s | - | 1.078 | 1.700 | |

| 6–9 m/s | 0.735 | 1.191 | 1.040 | |

| 9–12 m/s | 1.295 | 0.930 | 1.600 | |

| 12–15 m/s | 0.795 | 0.860 | 1.285 | |

| 15–16 m/s | 0.885 | 0.985 | 1.795 | |

| Last time all three leaves moved simultaneously time deviation. (Point B) | 0–3 m/s | - | - | - |

| 3–6 m/s | - | - | - | |

| 6–9 m/s | 1.924 | 1.990 | 2.142 | |

| 9–12 m/s | 2.125 | 2.366 | 2.895 | |

| 12–15 m/s | 3.588 | 3.065 | 2.732 | |

| 15–16 m/s | 1.955 | 3.430 | 3.915 | |

| Last single- leave movement time deviation. (Point C) | 0–3 m/s | - | - | - |

| 3–6 m/s | - | - | - | |

| 6–9 m/s | 1.218 | 1.210 | 2.310 | |

| 9–12 m/s | 0.712 | 1.022 | 2.192 | |

| 12–15 m/s | 0.944 | 1.532 | 3.272 | |

| 15–16 m/s | 1.099 | 1.775 | 3.010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, X.; Gu, C.; Feng, F.; Zhong, Y.; Song, J.; Zhai, C. Online Monitoring of Aerodynamic Characteristics of Fruit Tree Leaves Based on Strain-Gage Sensors. Agronomy 2026, 16, 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030279

Liu Y, Wang Z, Dong X, Gu C, Feng F, Zhong Y, Song J, Zhai C. Online Monitoring of Aerodynamic Characteristics of Fruit Tree Leaves Based on Strain-Gage Sensors. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):279. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030279

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yanlei, Zhichong Wang, Xu Dong, Chenchen Gu, Fan Feng, Yue Zhong, Jian Song, and Changyuan Zhai. 2026. "Online Monitoring of Aerodynamic Characteristics of Fruit Tree Leaves Based on Strain-Gage Sensors" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030279

APA StyleLiu, Y., Wang, Z., Dong, X., Gu, C., Feng, F., Zhong, Y., Song, J., & Zhai, C. (2026). Online Monitoring of Aerodynamic Characteristics of Fruit Tree Leaves Based on Strain-Gage Sensors. Agronomy, 16(3), 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030279