A One-Month-Delayed Secondary Harvest Induced by Pre-Flowering Shoot Tipping Improves Yield and Quality of ‘Chunguang’ Grape Under Protected Cultivation in Northern China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vine Material and Experimental Details

2.2. Experimental Design and Sampling

2.3. Measurements for Physical Parameters

2.4. Measurements for Basic Chemical Parameters

2.5. Color Indexes of Berry Skin

2.6. Texture Analysis

2.7. Determination of Mineral Elements

2.8. Determination of Sugar and Acid Constituents

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

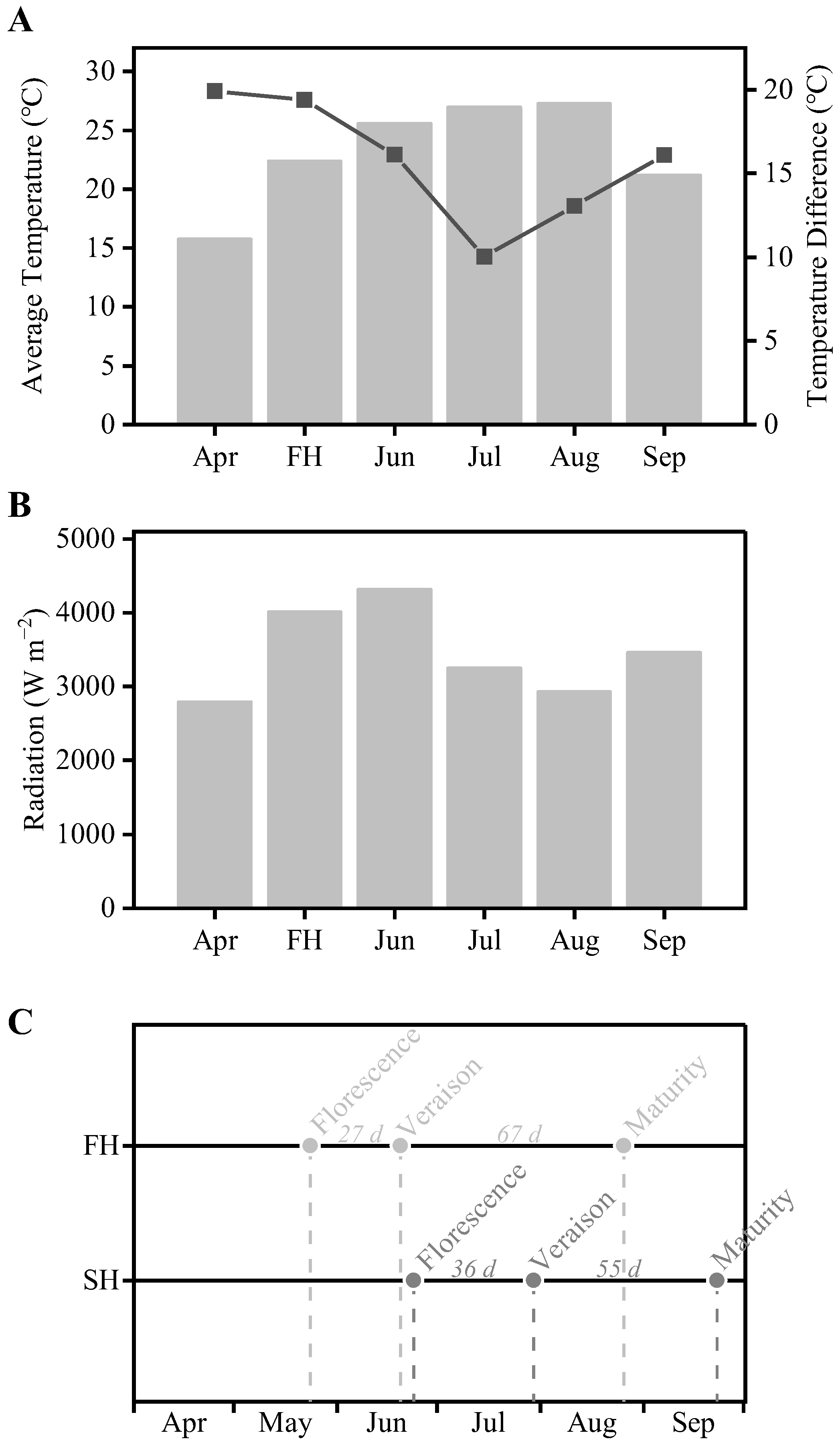

3.1. Meteorological and Phenological Data

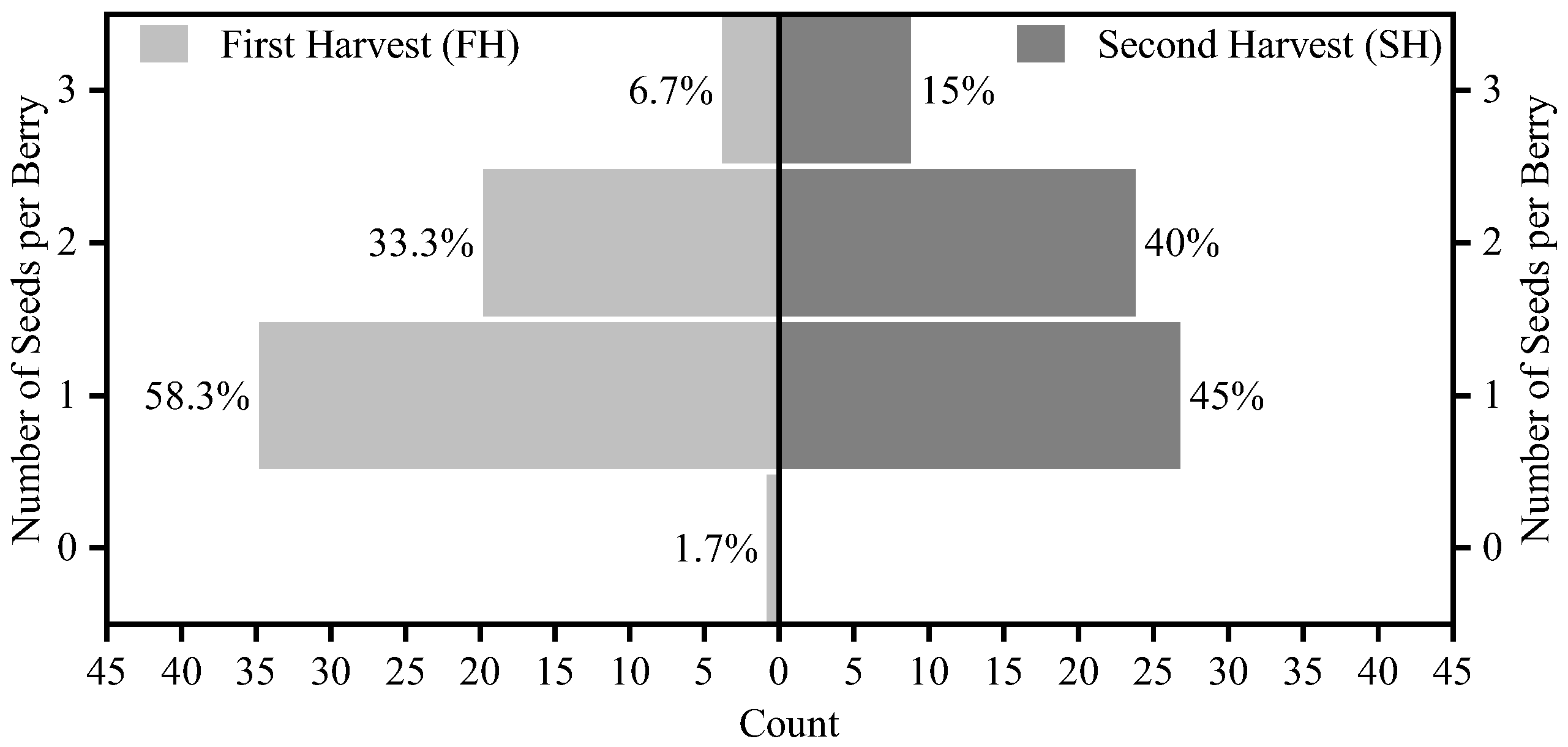

3.2. Physical and Chemical Parameters of the Grapes from Two Harvests

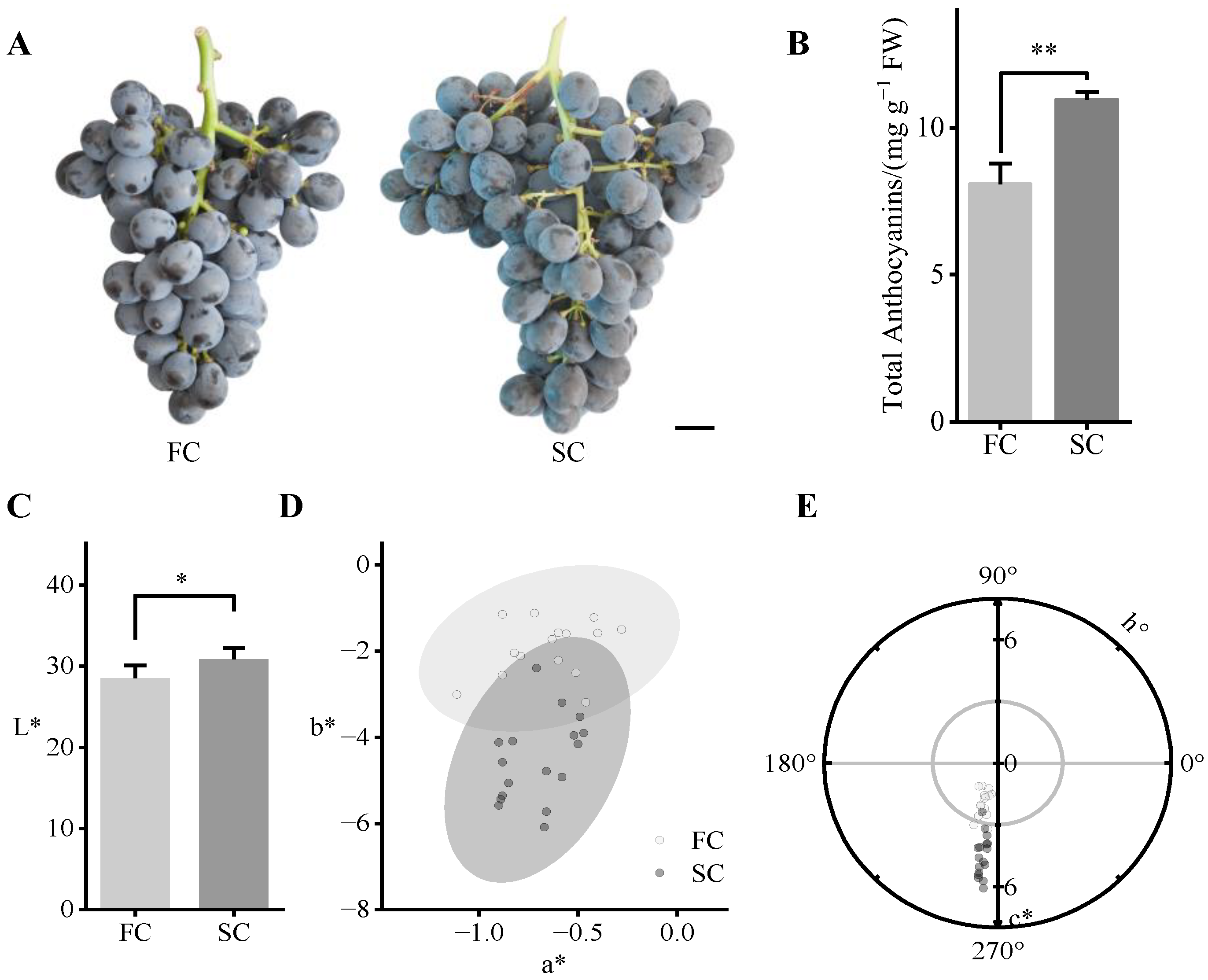

3.3. Color Indices of the Grapes from the Primary and Secondary Harvests

3.4. Berry Texture Indices of the Grapes from the Primary and Secondary Harvests

3.5. Mineral Composition of the Grapes from the Primary and Secondary Harvests

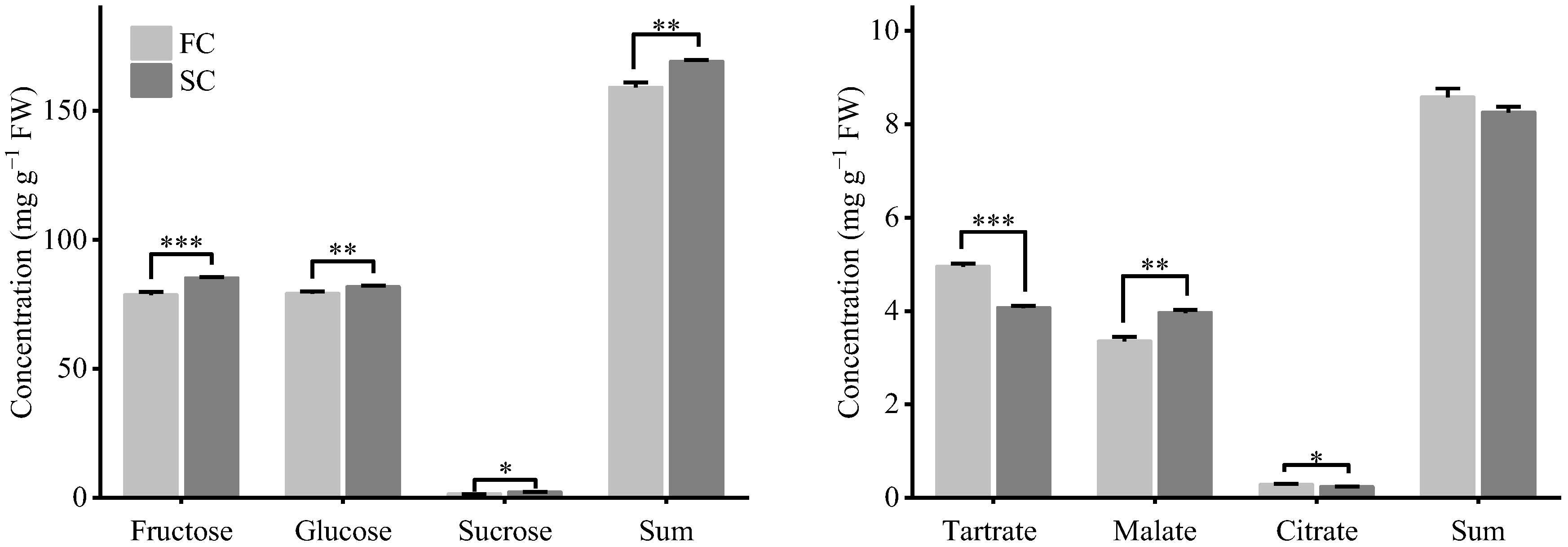

3.6. Contents of Sugar and Acids of the Grapes from the Primary and Secondary Harvests

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, F.; Kanianska, R.; Tian, D. Design and implementation of emergy-based sustainability decision assessment system for protected grape cultivation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14002–14025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiloglu, O.; Polat, A.A.; Durgac, C. Comparison of open field and protected cultivation of five early table grape cultivars under Mediterranean conditions. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2011, 35, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajiv; Kumari, M. Protected cultivation of high-value vegetable crops under changing climate. In Advances in Research on Vegetable Production Under a Changing Climate Vol. 2; Solankey, S.S., Kumari, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 229–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, B.; Sabir, A. Protected viticulture for sustainable grape production to cope with the adverse effects of climate change. J. Plant Sci. Crop Prot. 2024, 7, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, G.; Zhang, K.; Que, Y.; Li, Y. Grapevine double cropping: A magic technology. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1173985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, E.; Montague, T.; Kar, S. Secondary bud growth and fruitfulness of Vitis vinifera L. ‘Grenache’ grafted to three different rootstocks and grown within the Texas High Plains AVA. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2022, 22, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Padilha, C.V.; dos Santos Lima, M.; Toaldo, I.M.; Pereira, G.E.; Bordignon-Luiz, M.T. Effects of successive harvesting in the same year on quality and bioactive compounds of grapes and juices in semi-arid tropical viticulture. Food Chem. 2019, 301, 125170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Zhou, S.; Liu, J.; Feng, Q.; Wei, R.; Yu, H.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, X. Widely targeted metabolomics provides new insights into the flavonoid metabolism in ‘Kyoho’ grapes under a two-crop-a-year cultivation system. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Wang, B.; Lin, L.; Cheng, G.; Zhou, S.; Xie, S.; Shi, X.; Cao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, X. Evolutionary, interaction and expression analysis of floral meristem identity genes in inflorescence induction of the second crop in two-crop-a-year grape culture system. J. Genet. 2018, 97, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Qin, F.; Deng, F.; Luo, H.; Chen, X.; Cheng, G.; Bai, Y.; Huang, X.; Han, J.; Cao, X.; et al. Difference in flavonoid composition and content between summer and winter grape berries of Shine Muscat under two-crop-a-year cultivation. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2022, 55, 4473–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.; Lu, J.; Wang, Y. The growing season impacts the accumulation and composition of flavonoids in grape skins in two-crop-a-year viticulture. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 2861–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Roberto, S.R.; Shahab, M.; Colombo, R.C.; Silvestre, J.P.; Koyama, R.; de Souza, R.T. Proposal of double-cropping system for ‘BRS Isis’ seedless grape grown in subtropical area. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 251, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro Júnior, M.J.; Hernandes, J.L.; Bardin-Camparotto, L.; Blain, G.C. Plant parameters and must composition of ‘Syrah’ grapevine cultivated under sequential summer and winter growing seasons. Bragantia 2017, 76, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Zozzo, F.; Tiwari, H.; Canavera, G.; Frioni, T.; Poni, S. Exogenous cytokinins and auxins affect double cropping in Vitis vinifera L. cv. ‘Ortrugo’ grown in a temperate climate: Preliminary results. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moreno, A.; Sanz, F.; Yeves, A.; Gil-Muñoz, R.; Martínez, V.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Buesa, I. Forcing bud growth by double-pruning as a technique to improve grape composition of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Tempranillo in a semi-arid Mediterranean climate. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 256, 108614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toda, F.M. Global warming allows two grape crops a year, with about two months apart in ripening dates and with very different grape composition—The forcing vine regrowth to obtain two crops a year. Vitis 2021, 60, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Guo, R.; Liu, J.; Shi, X.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, L. Metabolome provides new insights into the volatile substances in ‘Ruidu Kemei’ grapes under the two-crop-a-year cultivation system. Fruit Res. 2024, 4, e035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Li, M.; Jia, N.; Sun, Y.; Han, B.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, S.; Guo, Z. Effects of trellis system and berry thinning intensity on vine performance and quality composition of two table grape cultivars under protected cultivation in northern China. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 299, 111045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombe, B.G. Growth stages of the grapevine: Adoption of a system for identifying grapevine growth stages. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1995, 1, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.A., Jr.; Melvin, E.H. Determination of dextran with anthrone. Anal. Chem. 1953, 25, 1656–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wu, L.; Yang, S.; Yuan, D.; Chen, L.; Pei, Z.; et al. Transcriptomic insights into higher anthocyanin accumulation in ‘Summer Black’ table grapes in winter crop under double-cropping viticulture system. Plants 2025, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Chen, G.; Qiu, D. Pruning and dormancy breaking make two sustainable grape-cropping productions in a protected environment possible without overlap in a single year. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poni, S.; Gatti, M.; Tombesi, S.; Squeri, C.; Sabbatini, P.; Lavado Rodas, N.; Frioni, T. Double cropping in Vitis vinifera L. Pinot Noir: Myth or reality? Agronomy 2020, 10, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulands, S.; Greer, D.H.; Harper, J.D.I. The interactive effects of temperature and light intensity on Vitis vinifera cv. ‘Semillon’ grapevines. II. Berry ripening and susceptibility to sunburn at harvest. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2014, 79, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Yang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, H.; Ma, J.; Li, S.; Yang, G.; Bai, M. Transcriptome analysis provides new insights into the berry size in ‘Summer Black’ grape under a two-crop-a-year cultivation system. Hortic. Plant J. 2025, 11, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.; Fucile, M.; Manzi, D.; Peruzzi, E.; Mattii, G.B. Effects of Zeowine and compost on leaf functionality and berry composition in Sangiovese grapevines. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 161, 412–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarooshi, R.A.; Bevington, K.B.; Coote, B.G. Performance and compatibility of ‘Muscat Gordo Blanco’ grape on eight rootstocks. Sci. Hortic. 1982, 16, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poni, S.; Del Zozzo, F.; Santelli, S.; Gatti, M.; Magnanini, E.; Sabbatini, P.; Frioni, T. Double cropping in Vitis vinifera L. cv. Pinot Noir: Agronomical and physiological validation. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2021, 27, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, A. Genetic and environmental impacts on the biosynthesis of anthocyanins in grapes. Hortic. J. 2018, 87, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Sugaya, S.; Gemma, H. Decreased anthocyanin biosynthesis in grape berries grown under elevated night temperature condition. Sci. Hortic. 2005, 105, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.J.; Broadley, M.R. Calcium in Plants. Ann. Bot. 2003, 92, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garneau, N.L.; Nuessle, T.M.; Mendelsberg, B.J.; Shepard, S.; Tucker, R.M. Sweet liker status in children and adults: Consequences for beverage intake in adults. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 65, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Tian, S.; Qin, Y.; Han, J. A new sensory sweetness definition and sweetness conversion method of five natural sugars, based on the Weber-Fechner Law. Food Chem. 2019, 281, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccichet, I.; Chiozzotto, R.; Bassi, D.; Gardana, C.; Cirilli, M.; Spinardi, A. Characterization of fruit quality traits for organic acids content and profile in a large peach germplasm collection. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 278, 109865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.; Puccioni, S.; Eichmeier, A.; Storchi, P. Prevention of drought damage through zeolite treatments on Vitis vinifera: A promising sustainable solution for soil management. Soil Use Manag. 2024, 40, e13036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Harvest (FH) | Second Harvest (SH) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster Weight (g) | 577.88 ± 104.96 | 397.85 ± 150.96 | <0.001 |

| CV of Cluster Weight | 0.18 | 0.38 | |

| Cluster Length (cm) | 19.27 ± 2.43 | 19.07 ± 1.76 | 0.7638 |

| Cluster Width (cm) | 15.86 ± 1.78 | 12.93 ± 1.28 | <0.001 |

| Number of Clusters per Vine | 15.33 ± 1.51 | 5.33 ± 0.82 | <0.001 |

| Yield per Vine (kg) | 8.86 ± 0.79 | 2.12 ± 0.3 | |

| Single Berry Weight (g) | 9.57 ± 0.47 | 6.69 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| CV of Berry Weight | 0.049 | 0.045 | |

| Berry Vertical Diameter (mm) | 28.47 ± 1.8 | 24.43 ± 1.8 | <0.001 |

| Berry Horizontal Diameter (mm) | 23.90 ± 1.22 | 20.03 ± 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Berry Shape Index | 1.18 ± 0.1 | 1.23 ± 0.07 | 0.0363 |

| Total Water Content (%) | 80.35 ± 0.15 | 78.76 ± 0.54 | 0.0077 |

| Thirty-seed Weight (g) | 2.68 ± 0.08 | 2.69 ± 0.09 | 0.8178 |

| Pulling Resistance (N) | 4.16 ± 0.98 | 4.21 ± 1.29 | 0.8576 |

| Peduncle Length (mm) | 8.99 ± 1.3 | 8.86 ± 0.9 | 0.66 |

| Peduncle Diameter (mm) | 2.07 ± 0.37 | 1.86 ± 0.36 | 0.0303 |

| TSSs (°Brix) | 20.9 ± 0.35 | 21.23 ± 0.06 | 0.1755 |

| TA (g L−1) | 4.2 ± 0.08 | 4.55 ± 0.23 | 0.0739 |

| TSSs/TA | 4.97 ± 0.18 | 4.67 ± 0.26 | 0.181 |

| pH | 4.25 ± 0.06 | 4.06 ± 0.03 | 0.0079 |

| Total Soluble Sugar (mg g−1 FW) | 208.5 ± 4.45 | 198.3 ± 20.83 | 0.4534 |

| First Harvest (FH) | Second Harvest (SH) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardness (N) | 11.11 ± 2.52 | 10.3 ± 1.14 | 0.1946 |

| Resilience | 0.27 ± 0.05 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 0.4388 |

| Cohesiveness | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.577 |

| Springiness (mm) | 4.53 ± 0.2 | 4.21 ± 0.15 | <0.001 |

| Gumminess (N) | 5.01 ± 0.71 | 4.82 ± 0.51 | 0.35 |

| Chewiness (mJ) | 22.71 ± 3.57 | 20.29 ± 2.24 | 0.018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yin, Y.; Jia, N.; Han, B.; Liu, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Han, S.; Li, M. A One-Month-Delayed Secondary Harvest Induced by Pre-Flowering Shoot Tipping Improves Yield and Quality of ‘Chunguang’ Grape Under Protected Cultivation in Northern China. Agronomy 2026, 16, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010065

Yin Y, Jia N, Han B, Liu C, Sun Y, Wang X, Han S, Li M. A One-Month-Delayed Secondary Harvest Induced by Pre-Flowering Shoot Tipping Improves Yield and Quality of ‘Chunguang’ Grape Under Protected Cultivation in Northern China. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Yonggang, Nan Jia, Bin Han, Changjiang Liu, Yan Sun, Xinyu Wang, Shuli Han, and Minmin Li. 2026. "A One-Month-Delayed Secondary Harvest Induced by Pre-Flowering Shoot Tipping Improves Yield and Quality of ‘Chunguang’ Grape Under Protected Cultivation in Northern China" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010065

APA StyleYin, Y., Jia, N., Han, B., Liu, C., Sun, Y., Wang, X., Han, S., & Li, M. (2026). A One-Month-Delayed Secondary Harvest Induced by Pre-Flowering Shoot Tipping Improves Yield and Quality of ‘Chunguang’ Grape Under Protected Cultivation in Northern China. Agronomy, 16(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010065