Short-Term Continuous Cropping of Dioscorea polystachya Alters the Rhizosphere Soil Microbiome and Degrades Soil Fertility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Collection

2.2. Soil Analysis of Chemical Properties

2.3. Determination of Soil Enzyme Activity

2.4. Analysis of Soil Microbiome Using High-Throughput Sequencing

- (1)

- Alpha diversityindices (Chao1 and Shannon) were calculated based on the normalized ASVs to assess species richness and community diversity of bacterial and fungal populations.

- (2)

- Venn diagrams were generated to visualize shared and unique ASVs across experimental treatments.

- (3)

- Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on weighted unifrac distances was used to illustrate structural differences in microbial communities among treatments.

- (4)

- Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) was used to identify biomarker taxa associated with each treatment.

- (5)

- Spearman correlation analysis and distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) were conducted to examine relationships between soil properties and microbial community composition.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Continuous Yam Cultivation on Soil Chemical Properties

3.2. Effects of Continuous Yam Cultivation on Soil Enzymatic Activity

3.3. Effects of Continuous Yam Cultivation on Rhizosphere Microbial Community

3.3.1. Abundance and Diversity of Microbial Communities

3.3.2. Microbial Community Structure

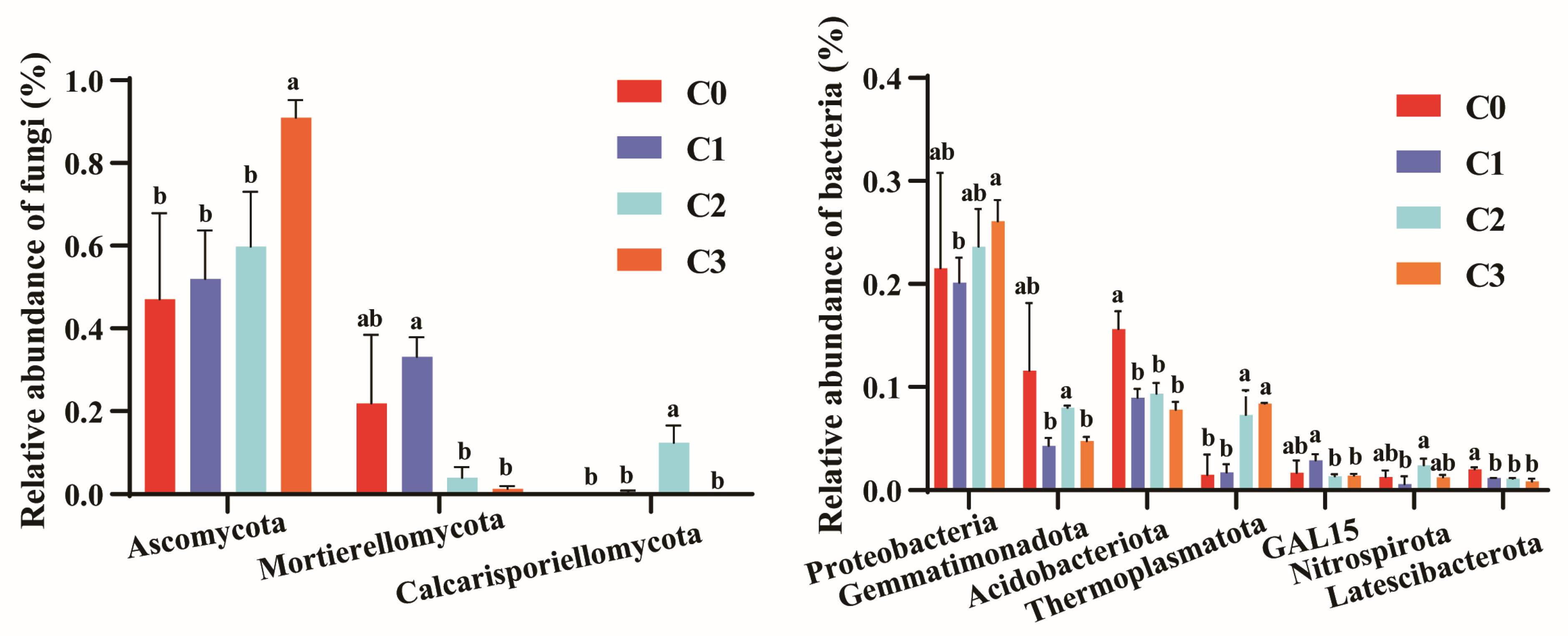

3.3.3. Relative Abundance of Fungal Communities at Phylum and Genus Level

3.3.4. Relative Abundance of Bacterial Communities at the Phylum and Genus Level

3.3.5. Distinct Microbial Taxa in Different Groups

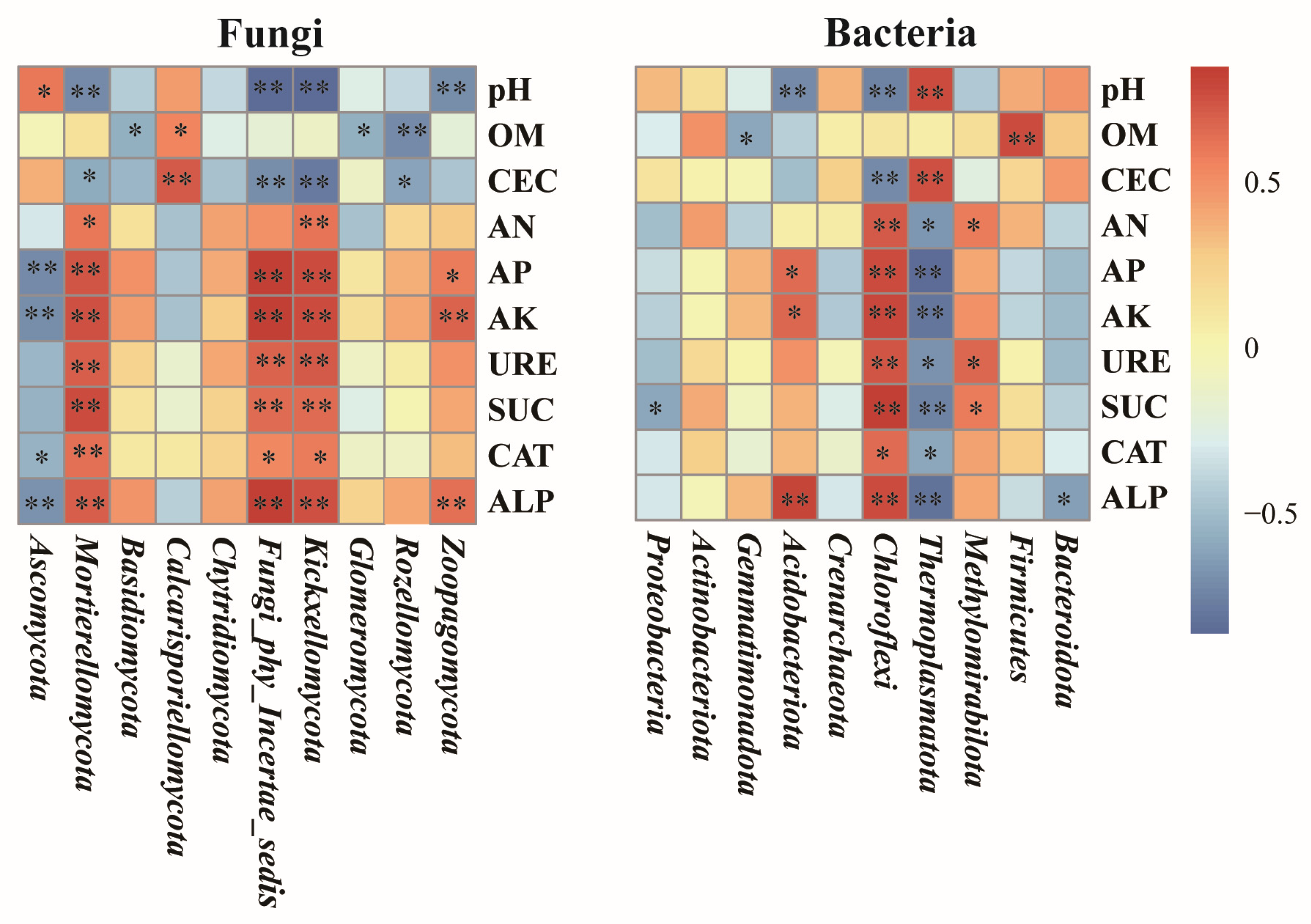

3.3.6. Correlation Between Soil Environmental Factors and Microorganism Composition

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Continuous Yam Cropping on Soil Chemical Properties

4.2. Effects of Continuous Cropping on Fungal and Bacterial Composition

4.3. The Correlation of Soil Properties with Microbial Community Composition

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OM | Organic matter |

| CEC | Cation exchange capacity |

| AN | Alkali hydrolyzed N |

| AP | Available P |

| AK | Available K |

| SUC | Sucrase |

| URE | Urease |

| CAT | Catalase |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

References

- Luo, G.F.; Podolyan, A.; Kidanemariam, D.B.; Pilotti, C.; Houliston, G.; Sukal, A.C. A review of viruses infecting yam (Dioscorea spp.). Viruses 2022, 14, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, M.; Ma, J.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, L.; Ma, H.; Chen, Z.; Hao, C.; et al. Comprehensive widely targeted metabolomics to decipher the molecular mechanisms of Dioscorea opposita thunb. cv. Tiegun quality formation during harvest. Food Chem. X 2024, 21, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; Chang, G.; Guo, L. Prospects of yam (Dioscorea) polysaccharides: Structural features, bioactivities and applications. Food Chem. 2024, 446, 138897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Hu, J.; Hong, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ran, Y. Extraction, separation and efficacy of yam polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, F.; Wang, R.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, W.; Bell, A.E.; Liu, X. Characterisation comparison of polysaccharides from Dioscorea opposita Thunb. growing in sandy soil, loessial soil and continuous cropping. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Wu, C.; Fan, L.; Kang, M.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yao, Y. Effects of the long-term continuous cropping of Yongfeng yam on the bacterial community and function in the rhizospheric soil. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Fan, L.; Jin, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. Continuous cropping of Tussilago farfara L. has a significant impact on the yield and quality of its flower buds, and physicochemical properties and the microbial communities of rhizosphere soil. Life 2025, 15, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Huo, H.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Li, F.; Li, X. Effects of long-term continuous cultivation on the structure and function of soil bacterial and fungal communities of Fritillaria cirrhosa on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, R.; Peukert, M.; Succurro, A.; Koprivova, A.; Kopriva, S. The role of soil microorganisms in plant mineral nutrition-current knowledge and future directions. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Hou, X.; Fang, X.; Razavi, B.; Zang, H.; Zeng, Z.; Yang, Y. Short-term continuous monocropping reduces peanut yield mainly via altering soil enzyme activity and fungal community. Environ. Res. 2024, 245, 117977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Hu, Y.; Han, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, J. Effects of continuous cropping of sweet potatoes on the bacterial community structure in rhizospheric soil. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wei, H.; Qi, D.; Li, W.; Dong, Y.; Duan, F.A.; Ni, S.Q. Continuous planting American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) caused soil acidification and bacterial and fungal communities’ changes. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Yu, J.; Hou, D.; Yue, H.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Lyu, J.; Jin, L.; Jin, N. Response of soil microbial community diversity to continuous cucumber cropping in facilities along the Yellow River irrigation area. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Hu, Y.; Han, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, J. Effects of continuous cropping of sweet potato on the fungal community structure in rhizospheric soil. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Liao, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y. Effects of four cropping patterns of Lilium brownii on rhizosphere microbiome structure and replant disease. Plants 2022, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wang, C.; He, X.; Liang, H.; Wu, Q.; Sun, X.; Liu, M.; Shen, P. Multi-year crop rotation and quicklime application promote stable peanut yield and high nutrient-use efficiency by regulating soil nutrient availability and bacterial/fungal community. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1367184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, X.; Huang, K. Effect of continuous cropping on the rhizosphere soil and growth of common buckwheat. Plant Prod. Sci. 2020, 23, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Yang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, T. Long-term watermelon continuous cropping leads to drastic shifts in soil bacterial and fungal community composition across gravel mulch fields. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Jiang, C.; Riaz, M.; Yu, F.; Dong, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zu, C.; Zhou, C.; Wang, J.; Shen, J. Impacts of continuous cropping on soil fertility, microbial communities, and crop growth under different tobacco varieties in a field study. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Song, J.; Zhang, J.; Qin, X.; Kang, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhou, S.; Chen, T. Effects of microbial agent application on the bacterial community in ginger rhizosphere soil under different planting years. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1203796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ciampitti, I.A.; Cui, J.; Qiu, S.; Xu, X.; Zhao, S.; He, P. Response of potato yield, soil chemical and microbial properties to different rotation sequences of green manure-potato cropping in North China. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 217, 105273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, C.; Wei, D.; Gu, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Cai, S.; Hu, Y.; Jin, L.; Wang, W. Soybean continuous cropping affects yield by changing soil chemical properties and microbial community richness. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1083736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Jiang, W.; Mantri, N.; Bao, X.; Chen, S.; Tao, Z. Characterizing diversity based on nutritional and bioactive compositions of yam germplasm (Dioscorea spp.) commonly cultivated in China. J. Food Drug Anal. 2016, 24, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Shan, N.; Ali, A.; Sun, J.; Luo, S.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, S.; Hu, R.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Q. Comprehensive evaluation of functional components, biological activities, and minerals of yam species (Dioscorea polystachya and D. alata) from China. LWT 2022, 168, 113964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloter, M.; Dilly, O.; Munch, J. Indicators for evaluating soil quality. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 98, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Sotres, F.; Trasar-Cepeda, C.; Leirós, M.C.; Seoane, S. Different approaches to evaluating soil quality using biochemical properties. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Xia, L.; Sun, Y.; Gao, S. Soil nutrients and enzyme activities based on millet continuous cropping obstacles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.; Ul Haq, M.Z.; Sun, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Yang, D.; Yang, H.; Wu, Y. Continuous cropping of Patchouli alters soil physiochemical properties and rhizosphere microecology revealed by metagenomic sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1482904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.T.; Robeson, M.S.; Lauber, C.L.; Hamady, M.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. A comprehensive survey of soil acidobacterial diversity using pyrosequencing and clone library analyses. ISME J. 2009, 3, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Expósito, R.; Postma, J.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; de Bruijn, I. Diversity and activity of Lysobacter species from disease suppressive soils. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Tian, G.; Pan, Y.; Wang, H.; Qiu, G.; Li, F.; Pang, Z.; Ding, K.; Zhang, J.; et al. Impacts of continuous potato cropping on soil microbial assembly processes and spread of potato common scab. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 206, 105805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Pan, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, X. Composition and diversity of rhizosphere fungal community in Coptis chinensis Franch. continuous cropping fields. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, D.; Wu, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, N.; Xu, L. Soil fungal diversity and community composition in response to continuous sweet potato cropping practices. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 90, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakelin, S.; Warren, R.; Kong, L.; Harvey, P. Management factors affecting size and structure of soil Fusarium communities under irrigated maize in Australia. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2008, 39, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yin, S.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X.; Zhong, S.; Zhang, G. Dactylonectria species associated with black root rot of strawberry in China. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2021, 50, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-ddin, S.; Haleem, R. First record of Dactylonectria macrodidyma: A cause of olive root rot in Iraq. For. Pathol. 2022, 52, e12729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Akhtar, N.; Msimbira, L.A.; Antar, M.; Ashraf, S.; Khan, S.N.; Smith, D.L. Neocosmospora rubicola, a stem rot disease in potato: Characterization, distribution and management. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 953097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Fan, X.; Tian, C.; Li, F.; Chou, G. Identification and characterization of Neocosmospora silvicola causing canker disease on Pinus armandii in China. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 3026–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Hu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, P.; Yang, S.; Xia, F. Bioorganic fertilizer can improve potato yield by replacing fertilizer with isonitrogenous content to improve microbial community composition. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z. Dissecting the effect of continuous cropping of potato on soil bacterial communities as revealed by high-throughput sequencing. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Bian, C.; Duan, S.; Wang, W.; Li, G.; Jin, L. Effects of different rotation cropping systems on potato yield, rhizosphere microbial community and soil biochemical properties. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 999730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousk, J.; Bååth, E.; Brookes, P.; Lauber, C.; Lozupone, C.; Caporaso, J.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J. 2010, 4, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Yang, X.; Tang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Z. Soil properties and plant functional traits have different importance in shaping rhizosphere soil bacterial and fungal communities in a meadow steppe. mSystems 2025, 10, e00570-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| C0 | C1 | C2 | C3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 8.19 ± 0.04 d | 8.46 ± 0.03 c | 8.76 ± 0.04 b | 8.90 ± 0.04 a |

| Organic matter (g/kg) | 12.64 ± 0.16 d | 19.28 ± 0.15 a | 14.74 ± 0.11 b | 13.48 ± 0.03 c |

| CEC (cmol/kg) | 6.38 ± 0.15 c | 8.23 ± 0.08 b | 33.62 ± 0.28 a | 33.35 ± 0.18 a |

| C0 | C1 | C2 | C3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | ||||

| Mortierella | 0.199 ± 0.18 ab | 0.221 ± 0.099 a | 0.014 ± 0.004 b | 0.023 ± 0.007 b |

| Fungi_gen_Incertae_sedis | 0.021 ± 0.004 a | 0.005 ± 0.003 b | 0 b | 0 b |

| Fusarium | 0.019 ± 0.005 a | 0.025 ± 0.012 ab | 0.002 ± 0.001 b | 0 b |

| Chaetomium | 0.029 ± 0.042 b | 0.145 ± 0.046 a | 0.012 ± 0.012 b | 0 b |

| Alternaria | 0.008 ± 0.01 b | 0.073 ± 0.028 a | 0.002 ± 0.001 b | 0.002 ± 0 b |

| Dactylonectria | 0.013 ± 0.003 b | 0.002 ± 0.001 c | 0.175 ± 0.055 a | 0.035 ± 0.014 bc |

| Arthrobotrys | 0.01 ± 0.015 b | 0.005 ± 0.008 b | 0.139 ± 0.006 a | 0.152 ± 0.042 a |

| Calcarisporiella | 0 b | 0.005 ± 0.004 b | 0.124 ± 0.041 a | 0.001 ± 0 b |

| Neocosmospora | 0.018 ± 0.014 b | 0.034 ± 0.047 ab | 0.113 ± 0.023 a | 0.006 ± 0.003 b |

| Subulicystidium | 0 b | 0 b | 0.014 ± 0.003 a | 0.022 ± 0.01 ab |

| Campylospora | 0 b | 0 b | 0.013 ± 0 a | 0 b |

| Brunneochlamydosporium | 0.002 ± 0.001 b | 0.001 ± 0.002 b | 0.019 ± 0.02 b | 0.446 ± 0.043 a |

| Fusidium | 0 b | 0.009 ± 0.008 b | 0.03 ± 0.035 ab | 0.054 ± 0.012 a |

| Ilyonectria | 0.005 ± 0.001 c | 0.011 ± 0.009 abc | 0.017 ± 0.001 b | 0.026 ± 0.003 a |

| Bacteria | ||||

| Gaiella | 0.01 ± 0.004 b | 0.042 ± 0.008 a | 0.012 ± 0.001 b | 0.009 ± 0.003 b |

| wb1-A12 | 0.007 ± 0.006 b | 0.021 ± 0.005 a | 0.002 ± 0.001 b | 0.006 ± 0.001 b |

| Lysobacter | 0.004 ± 0.003 b | 0.013 ± 0.003 a | 0.017 ± 0.005 a | 0.018 ± 0.014 a |

| Nitrospira | 0.013 ± 0 b | 0.006 ± 0.007 b | 0.024 ± 0.006 a | 0.012 ± 0.002 ab |

| Candidatus_Nitrosotenuis | 0.002 ± 0.002 b | 0.001 ± 0 b | 0.013 ± 0.004 a | 0.021 ± 0.006 a |

| Polycyclovorans | 0.001 ± 0.001 d | 0.008 ± 0.001 c | 0.015 ± 0.001 b | 0.029 ± 0.002 a |

| Streptomyces | 0.001 ± 0.001 c | 0.012 ± 0.012 abc | 0.007 ± 0.002 b | 0.03 ± 0.003 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, G.; Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Yao, C.; Pei, Q.; Ma, Z.; Xu, G.; Bu, X.; Zhang, Q. Short-Term Continuous Cropping of Dioscorea polystachya Alters the Rhizosphere Soil Microbiome and Degrades Soil Fertility. Agronomy 2026, 16, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010059

Liu G, Liu W, Chen X, Yao C, Pei Q, Ma Z, Xu G, Bu X, Zhang Q. Short-Term Continuous Cropping of Dioscorea polystachya Alters the Rhizosphere Soil Microbiome and Degrades Soil Fertility. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Guoxia, Wei Liu, Xueyan Chen, Chuan Yao, Qinghua Pei, Zhikun Ma, Guoxin Xu, Xun Bu, and Quanfang Zhang. 2026. "Short-Term Continuous Cropping of Dioscorea polystachya Alters the Rhizosphere Soil Microbiome and Degrades Soil Fertility" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010059

APA StyleLiu, G., Liu, W., Chen, X., Yao, C., Pei, Q., Ma, Z., Xu, G., Bu, X., & Zhang, Q. (2026). Short-Term Continuous Cropping of Dioscorea polystachya Alters the Rhizosphere Soil Microbiome and Degrades Soil Fertility. Agronomy, 16(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010059