1. Introduction

Agriculture is widely recognized as a major contributor to anthropogenic greenhouse gases (GHG), emitting carbon dioxide (CO

2), methane (CH

4), and nitrous oxide (N

2O) through soil degradation, livestock-related processes, and intensive crop management [

1]. Recent global assessments indicate that agricultural emissions have continued to rise, with food systems responsible for approximately one-third (34%) of total anthropogenic GHG emissions and agricultural emissions increasing by 9.3% between 2000 and 2018, driven primarily by synthetic fertilizer use and livestock expansion in developing regions [

1,

2]. The agricultural sector now accounts for 10–14% of direct anthropogenic GHG emissions globally, with significant regional disparities. Emissions in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have doubled since 1990, while developed nations show modest declines [

2]. These emissions account for a substantial share of global warming, with croplands serving both as significant sources and potential sinks of GHG through soil carbon sequestration and improved land management [

2]. The need to mitigate these emissions has grown increasingly urgent, as agriculture faces mounting pressures from climate change, food security concerns, and sustainability goals [

3,

4]. Emerging evidence from 2024 to 2025 emphasizes that agricultural systems must simultaneously achieve emission reductions, climate adaptation, and enhanced productivity, a “triple challenge” requiring integrated strategies that move beyond single-objective interventions [

3,

5].

Various agronomic interventions have been identified to reduce emissions, including cover cropping, reduced tillage, crop diversification, agroforestry, and organic amendments [

6,

7]. These practices enhance soil organic carbon stocks, reduce erosion, and improve resilience to extreme weather events [

8]. Recent meta-analyses from 2022 to 2025 have refined the understanding of practice-specific mitigation potentials with greater precision. Meta-analysis of 119 paired observations from 18 studies demonstrated that biochar application consistently reduced N

2O emissions by 16.2% (95% CI: 9.8–22.6%) in temperate agricultural systems, with moderate-to-high heterogeneity (I

2 = 72%) and no evidence of publication bias (Egger’s test,

p = 0.18) [

9]. Effectiveness was maintained over 4–6 years in long-term trials [

10], with greater reductions in acidic soils (pH < 6.5) due to the liming effect [

9]. However, effectiveness was lower in tropical systems (8–12% reduction) where validation data remain limited [

11]. This demonstrates superior consistency compared to no-till agriculture, which shows high variability (meta-analysis of 212 observations from 40 studies: mean −11%, 95% CI: −19% to −1%; I

2 = 89%) with effects ranging from 19% reductions to 70% increases depending on soil texture, climate, and moisture regime [

12].

Legume-based crop rotations reduce N

2O emissions by up to 39% through improved nitrogen efficiency while increasing soil organic carbon by 18% compared to monoculture systems. However, the net benefits of such interventions are context-dependent, often influenced by soil type, climate, and farming system design [

13]. Emerging integrated practices, such as recoupled crop–livestock systems, demonstrate potential for over 40% emission reductions when properly designed, though adoption barriers remain substantial [

14]. In addition, monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) frameworks face methodological inconsistencies that limit the reliability of estimates. Recent assessments from 2025 highlight that measurement uncertainties of ±30–50% in field-based emission factors and inconsistent life cycle assessment boundaries (creating 2–5-fold variations in reported emissions for identical crops) continue to undermine verification systems essential for carbon credit markets and climate policy implementation [

15].

Nitrous oxide emissions are of particular concern because of their high global warming potential (GWP) (265 times that of CO

2 over 100 years) and direct link to nitrogen fertilizer application [

16]. Global analyses indicate that N

2O emissions from croplands have quadrupled over the last six decades, with hotspots in Asia and intensive horticultural systems [

17]. Strategies such as the “4R” nutrient stewardship (right source, rate, time, and placement) and precision irrigation have been highlighted as effective measures to reduce N

2O by 55–64% when combined with enhanced-efficiency fertilizers (EEFs) while sustaining yields [

3,

18]. Crop-specific assessments show maize, rice, wheat, and vegetable systems to be the most significant contributors and therefore prime targets for mitigation [

19].

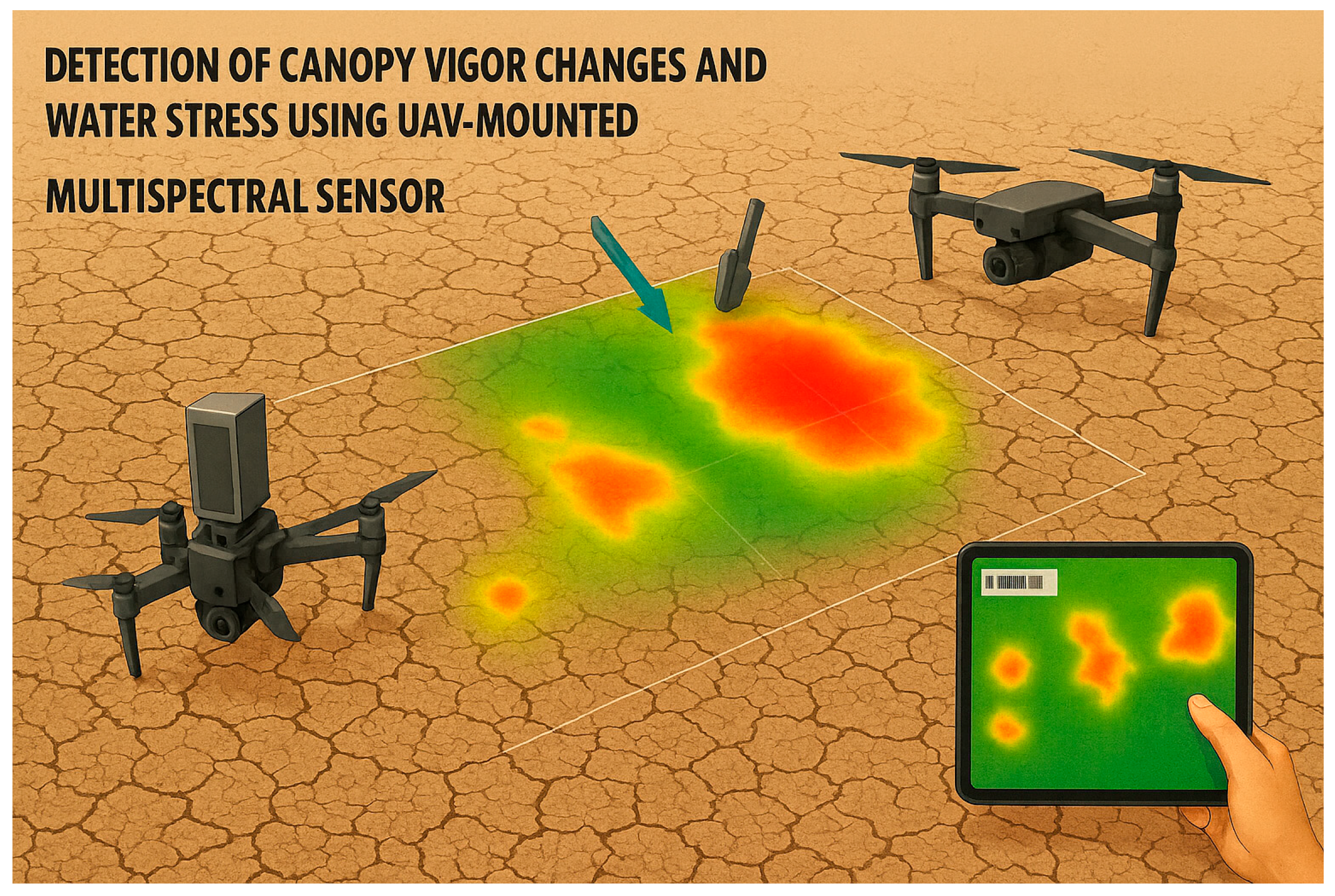

The integration of digital technologies with nutrient management has emerged as a transformative approach since 2022, marking a shift toward “agriculture 4.0” paradigms. Artificial intelligence-driven decision support systems now enable real-time optimization of fertilizer application, with demonstrated N

2O reductions of 20–30% compared to conventional practices in field trials across South Asia and East Africa [

20]. Remote sensing combined with machine learning models allows spatially explicit identification of emission hotspots at field-to-regional scales, enabling targeted interventions that account for within-field heterogeneity in soil properties and crop nitrogen demand [

21]. Internet of Things (IoT) sensors integrated with precision irrigation systems further optimize water–nitrogen interactions, reducing both CH

4 emissions in rice systems and N

2O emissions in upland crops [

22]. However, adoption of these digital technologies remains below 15% in smallholder systems due to high upfront costs (USD 15,000–50,000 per farm for equipment) and limited digital literacy [

20].

Despite promising technical potentials, adoption of mitigation strategies remains constrained by persistent socio-economic realities, with realistic implementation limited to 25–35% of technical potential across diverse farming systems [

23]. Recent surveys from 2023 to 2024 reveal that capital constraints affect 65–80% of smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, preventing investment in proven practices such as biochar application (USD 200–400 ha

−1 initial cost with 5–7-year payback periods) despite documented emission reductions [

23]. Barriers include land tenure insecurity (affecting 60% of farmers in sub-Saharan Africa), lack of capital, risk perception, and compatibility with traditional practices [

24].

Gender disparities compound these barriers significantly, as women farmers control 43% of agricultural labor in developing regions but access only 10–20% of agricultural extension services and 5–15% of agricultural credit, reducing adoption rates of climate-smart practices by 20–35% in female-headed households [

25]. Inadequate extension service ratios (1 agent per 1000–2000 farmers in many developing regions) further limit knowledge diffusion and technical support for practice adoption [

24].

Policy frameworks, incentive structures, and market-based mechanisms, such as carbon credits, influence adoption rates but bring additional challenges of equity and verification [

26]. As a result, biophysical estimates often overstate mitigation potential without accounting for the socio-economic conditions of real farming systems [

27]. Emerging evidence from 2024 indicates that bundled interventions combining financial incentives (subsidies, low-interest credit), training programs, secure land rights, and gender-responsive extension services can increase adoption rates by 40–60% compared to single-factor approaches, suggesting that integrated socio-economic support is essential for scaling mitigation practices [

28].

The climate-smart agriculture (CSA) paradigm has evolved significantly since 2022, with increased emphasis on integrated, context-specific solutions that address mitigation, adaptation, and productivity simultaneously. Recent frameworks prioritize regenerative practices, including regenerative agroforestry, conservation agriculture, and integrated crop–livestock systems, that enhance soil health, biodiversity, and farmer resilience while reducing emissions [

6]. However, implementation challenges persist at scale. A 2024 global assessment found that CSA adoption varies varying substantially across regions (from 5% in some sub-Saharan African countries to over 50% in parts of Europe and North America) due to policy mismatches between national climate strategies and local agricultural realities. Notably, majority of surveyed farmers across Kenya, Tanzania, and Ethiopia were unaware of national climate-smart agricultural policies, despite their proven effectiveness, highlighting a disconnect between policy design and implementation at the farmer level [

29].

Market-based mechanisms, particularly carbon trading schemes, have gained prominence in 2023–2024 as tools to incentivize agricultural GHG mitigation. Recent analyses demonstrate that carbon credit systems can reduce agricultural emissions through innovation in low-carbon technologies, renewable energy adoption, and ecosystem restoration, with documented transaction volumes increasing by 45% annually in voluntary agricultural carbon markets [

30]. However, equity concerns persist regarding smallholder participation, as transaction costs for (MRV) average USD 50–150 ha

−1, often exceeding the carbon revenue potential (USD 20–80 ha

−1 year

−1) for small-scale farmers, effectively excluding them from market benefits [

15,

30]. The integrity of carbon accounting frameworks remains contested, with 2025 studies highlighting that methodological inconsistencies and measurement uncertainties undermine credibility and risk creating “carbon greenwashing” rather than genuine emission reductions [

15].

Emerging paradigms in 2024–2025 emphasize system-level integration and circular economy principles in agriculture. Recoupled crop–livestock systems, for instance, demonstrate potential for over 40% emission reductions in China through optimized nutrient cycling, manure valorization, and reduced reliance on synthetic inputs [

14]. Similarly, regenerative agroforestry approaches combining carbon sequestration (74–320 Mg C ha

−1 depending on system age) with biodiversity conservation and climate-resilient landscapes show promise, though adoption timelines span 10–15 years before full benefits materialize [

31]. These integrated approaches align with recent calls for “agriculture 4.0” that leverages digital technologies to optimize both productivity and environmental outcomes, representing a paradigm shift from single-practice interventions to holistic farm system redesign [

22].

To address these complexities, this review introduces the ICEMF, a novel synthesis approach that couples practice-level evidence with spatially explicit modeling of N

2O and Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) outcomes. The framework integrates empirical data, regional modeling, and socio-economic adoption pathways, offering a decision-support tool for scalable interventions [

32]. By combining technological, agronomic, and policy perspectives, ICEMF provides a roadmap for reducing agricultural GHG while maintaining productivity [

33,

34,

35].

1.1. Global Imperatives and the Need for Integrated Frameworks

1.1.1. The Urgency of Agricultural Climate Action

The need for transformative agricultural GHG mitigation has never been more urgent. Climate change is already reducing global crop yields, with temperature increases projected to decrease wheat yields by 6.0% and maize by 7.4% per degree Celsius without CO

2 fertilization, effective adaptation, and genetic improvement [

36,

37]. Simultaneously, agricultural systems must feed 9.8 billion people by 2050, requiring a 50–70% increase in food production from 2010 levels, while reducing absolute GHG emissions [

38,

39]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that limiting warming to 1.5 °C requires agricultural emission reductions of approximately 1 gigaton CO

2-equivalent per year by 2030, with agriculture potentially contributing 3.9–4.0 gigatons of annual emission reductions by 2050 through technical mitigation and dietary changes [

40,

41].

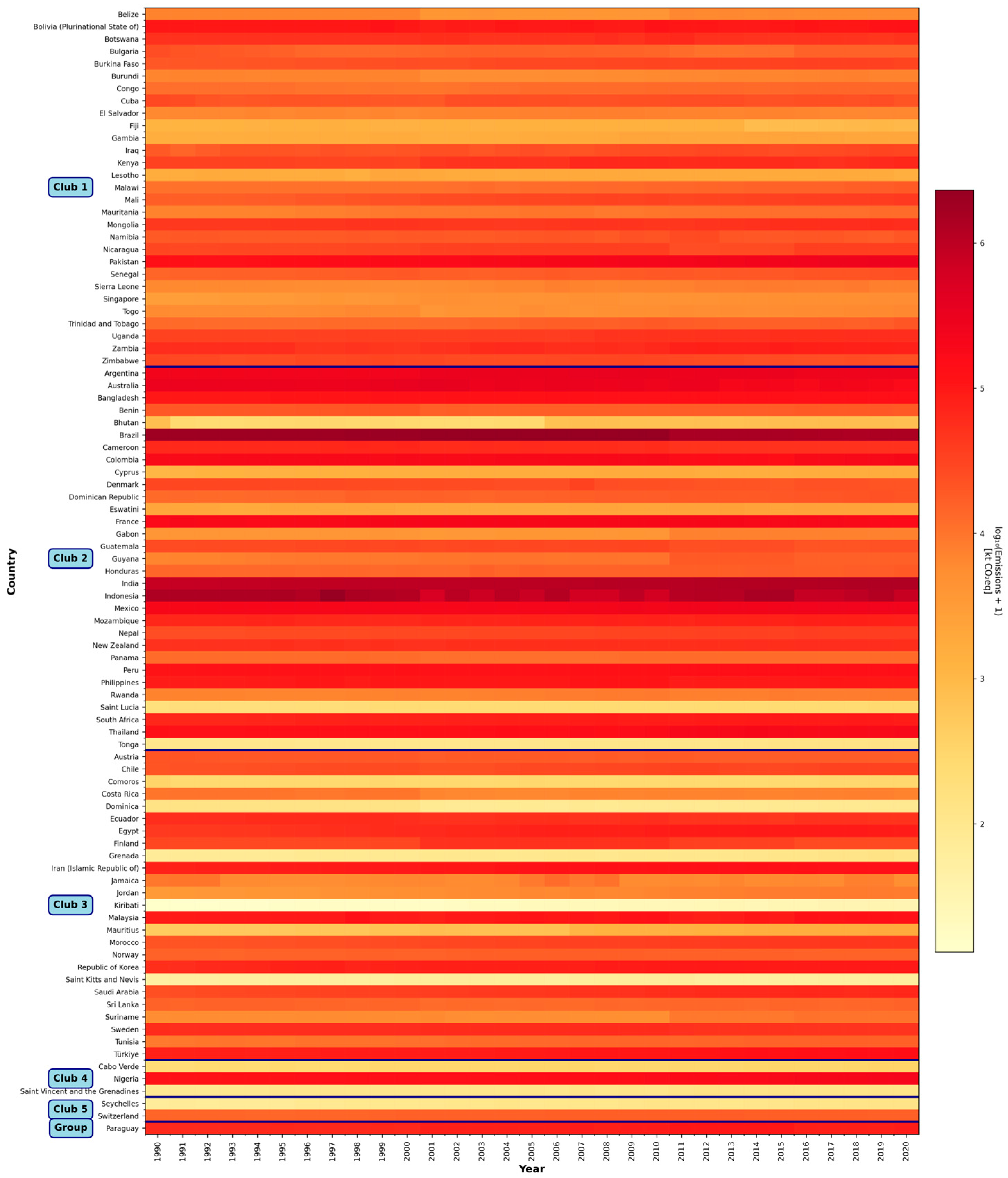

Yet, current trajectories are moving in the opposite direction. Food systems contributed 34% of global anthropogenic GHG emissions in 2015, totaling 18 gigatons of CO

2-equivalent per year [

2]. Total food system emissions reached approximately 16 gigatons CO

2eq in 2018, representing one-third of global anthropogenic emissions, with an 8% increase since 1990 [

42]. While emissions from land-use change have declined by 29% since 2000, farm-gate agricultural emissions increased by 13% over the same period, and pre- and post-production emissions grew by 45%. Regional disparities are striking: between 2000 and 2020, agrifood system emissions increased by 35% in Africa and 20% in Asia, driven by expanding livestock production and intensified fertilizer use [

43,

44]. Without transformative interventions across production systems, demand management, and supply chains, agricultural emissions are projected to reach 15 gigatons CO

2eq by 2050, fundamentally undermining Paris Agreement goals and requiring closure of an 11-gigaton mitigation gap [

45].

1.1.2. The Food Security–Climate Mitigation Nexus

The imperative of food security compounds the challenge. Global food insecurity affects populations overwhelmingly concentrated in regions where agriculture is both the primary livelihood and most vulnerable to climate change [

46,

47]. Smallholder farmers, who produce 35% of the world’s food on farms smaller than 2 hectares, face simultaneous pressures from climate adaptation (increased droughts, floods, and pests) and mitigation expectations, while lacking access to essential resources [

48,

49]. These farmers are particularly vulnerable to climate impacts that threaten both their production capacity and livelihoods [

50].

This creates a critical equity dimension: the populations least responsible for historical emissions (smallholder farmers in developing nations) are most vulnerable to climate impacts and face the most significant barriers to adopting mitigation practices. Systemic constraints limit their capacity to respond: 65–80% lack access to formal credit necessary for investing in climate-smart technologies [

51], 60% face insecure land tenure that discourages long-term soil improvement investments [

52], and extension service ratios of 1 agent per 1000–2000 farmers in many regions severely restrict knowledge transfer and technical support [

53]. Gender disparities compound these barriers significantly, as women farmers control 43% of agricultural labor in developing regions but access only 10–20% of agricultural extension services and 5–15% of agricultural credit, reducing adoption rates of climate-smart practices by 20–35% in female-headed households [

54,

55]. Any viable framework must therefore address not only technical emission reduction potential but also the socio-economic justice dimensions of enabling equitable participation in climate solutions while ensuring food security and livelihoods.

1.1.3. Why Existing Frameworks Are Insufficient for Agricultural GHG Mitigation and Climate Adaptation

Current frameworks for agricultural GHG mitigation operate in silos, addressing either technical potential or policy implementation, but rarely integrating both with socio-economic realities:

Technical frameworks (e.g., 4R nutrient stewardship, conservation agriculture protocols) provide scientifically validated practices but lack mechanisms to scale adoption. The 4R framework, despite demonstrating 55–64% N

2O reductions in field trials, achieves limited adoption globally after 20 years of promotion, with studies documenting low adaptation despite effectiveness in key agricultural regions, revealing fundamental disconnects between technical recommendations and farmer realities [

18,

56,

57]. No-till agriculture shows similarly low uptake, approximately 12–25% of cropland globally, despite proven soil carbon benefits, because recommendations fail to account for region-specific challenges such as soil compaction in tropical systems, herbicide costs, and incompatibility with smallholder crop–livestock integration [

58,

59].

Policy frameworks (e.g., climate-smart agriculture, low-emission development strategies) set ambitious national targets but struggle with implementation. A 2025 assessment found that approximately 70% of farmers in Kenya with comprehensive CSA policies were unaware these policies existed, highlighting a fundamental disconnect between policy design and farmer-level action [

29]. Moreover, these frameworks rarely specify how national emission reduction targets translate to farm-level practices across heterogeneous landscapes, with implementation varying substantially across regions due to weak scaling mechanisms and insufficient attention to context-specific barriers [

60,

61].

Modeling frameworks (e.g., Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs), life cycle assessments) operate at scales mismatched to farmer decision-making. IAMs aggregate agricultural systems into large regions (e.g., “sub-Saharan Africa”), obscuring substantial within-region variation in soil types, rainfall patterns, farmer resources, and market access that determine whether a mitigation practice succeeds or fails [

62,

63]. These models inadequately capture the behavioral, institutional, and socio-economic factors that govern farmer technology adoption, limiting their utility for designing implementable interventions. Life cycle assessments provide detailed emission accounting but suffer from methodological inconsistencies; emission estimates for identical crops can vary two- to five-fold depending on unreported differences in system boundaries, allocation methods, and regional assumptions [

64,

65].

Carbon market mechanisms promise to incentivize adoption through payments for verified emission reductions but face critical credibility gaps. Measurement uncertainties of ±30–50% in field-based emission factors undermine the integrity of carbon accounting systems [

15], while standardized MRV protocols remain absent or inadequate for the majority of agricultural interventions [

66,

67]. High transaction costs for MRV activities often exceed potential carbon revenue for smallholder farmers, effectively excluding them from market benefits and raising concerns about equity and genuine versus “greenwashed” mitigation [

68,

69,

70].

In summary, ICEMF is essential because it provides the integrated, scalable, and equitable methodology that agriculture urgently requires to simultaneously address climate mitigation, food security, and farmer resilience in the critical decade ahead. Without such integration, agricultural systems risk continuing trajectories that exacerbate rather than solve the interconnected crises of climate change and food insecurity. The framework directly responds to recent calls from global policy processes including the UN Food Systems Summit’s emphasis on integrated transformation [

71], the IPCC AR6’s identification of agriculture as a “critical near-term opportunity” constrained by implementation gaps [

72], and the Paris Agreement Global Stocktake’s revelation that most national climate commitments lack specific, verifiable agricultural emission reduction pathways [

73,

74] (

Figure 1). The novel contributions of this study are as follows:

Proposes the ICEMF as a hybrid approach that unites field-level management practices with global-scale emission modeling.

Provides a dual synthesis of practice-based interventions and spatially explicit N2O mitigation assessments, highlighting synergies often overlooked in single-focus reviews.

Identifies critical policy–practice trade-offs and socio-economic adoption barriers, offering a roadmap for aligning climate targets with farmer-centric solutions.

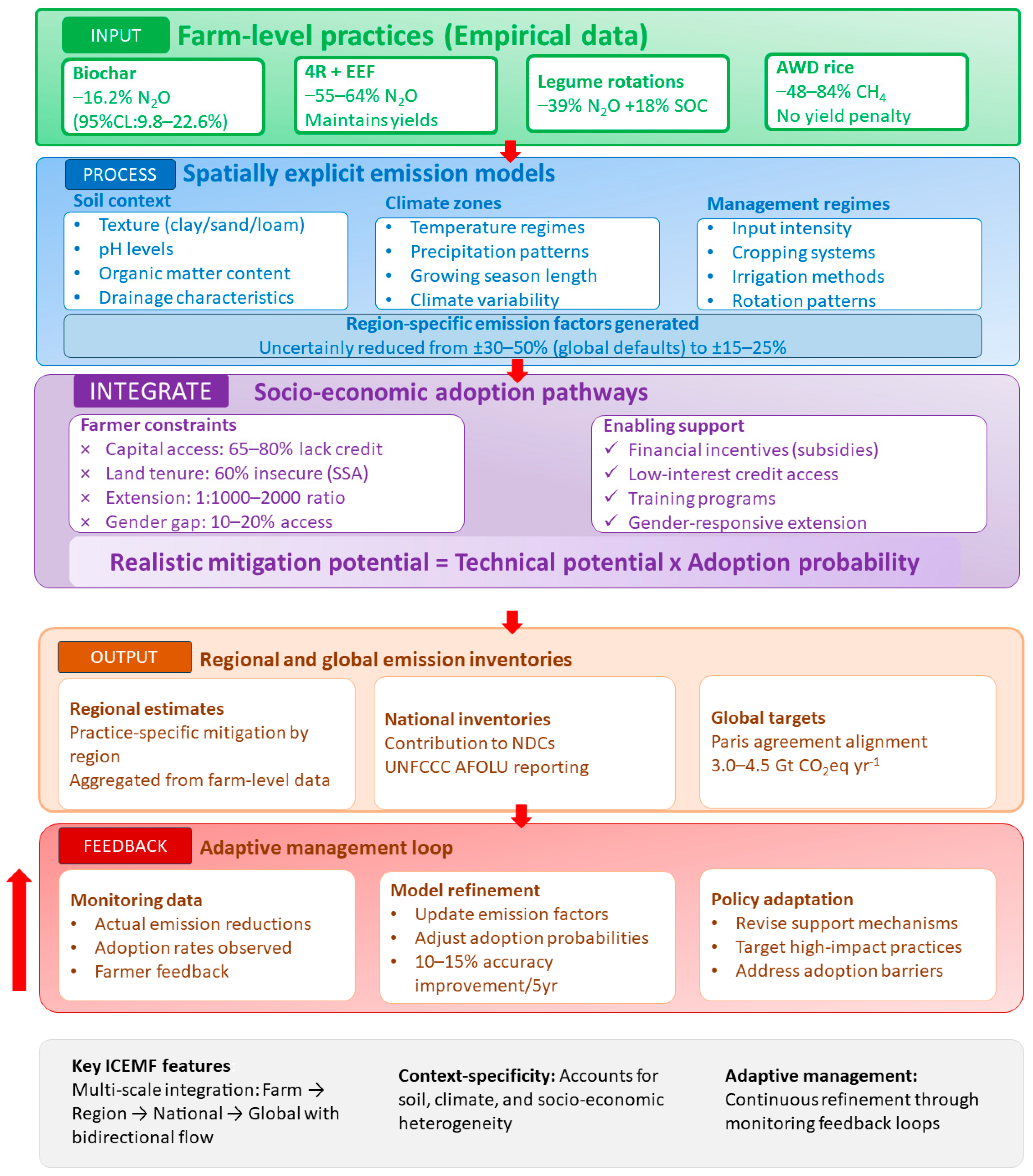

Figure 1.

ICEMF data flow and feedback mechanisms. The framework integrates five operational layers: (1) INPUT—farm-level practices provide empirical emission data with quantified reduction potentials; (2) PROCESS—spatially explicit models account for soil, climate, and management contexts, reducing uncertainty from ±30–50% to ±15–25%; (3) INTEGRATE—socio-economic adoption pathways adjust technical potential by realistic adoption probabilities (baseline 5–25%, improving to 40–60% with bundled support); (4) OUTPUT-regional estimates aggregate to national inventories (NDCs) and global targets (3.0–4.5 Gt CO2eq yr−1); (5) FEEDBACK—monitoring data enables continuous refinement of emission factors and policy mechanisms, improving accuracy by 10–15% over 5 years. Downward information flow (green → blue → purple → orange) translates carbon budgets to farm-level guidance; upward feedback loop (red) continuously improves framework performance through observed field data.

Figure 1.

ICEMF data flow and feedback mechanisms. The framework integrates five operational layers: (1) INPUT—farm-level practices provide empirical emission data with quantified reduction potentials; (2) PROCESS—spatially explicit models account for soil, climate, and management contexts, reducing uncertainty from ±30–50% to ±15–25%; (3) INTEGRATE—socio-economic adoption pathways adjust technical potential by realistic adoption probabilities (baseline 5–25%, improving to 40–60% with bundled support); (4) OUTPUT-regional estimates aggregate to national inventories (NDCs) and global targets (3.0–4.5 Gt CO2eq yr−1); (5) FEEDBACK—monitoring data enables continuous refinement of emission factors and policy mechanisms, improving accuracy by 10–15% over 5 years. Downward information flow (green → blue → purple → orange) translates carbon budgets to farm-level guidance; upward feedback loop (red) continuously improves framework performance through observed field data.

1.2. Review Context and Objectives

The literature on GHG emissions in agriculture highlights both the scale of the problem and the diverse mitigation strategies proposed to balance productivity with sustainability.

Table 1 shows summary of research gaps. Ullah, Farooque [

75] reviewed biochar production processes and demonstrated its potential to reduce soil-based GHG emissions by enhancing carbon storage, soil quality, and microbial activity. Zhu and Miller [

76] found that tomato production systems vary widely in emissions, highlighting precision agriculture and low-carbon energy as key interventions. Ref. [

77] applied a harmonized methodology to soybean production studies, finding significant variability in GHG emissions driven by fertilizer use, irrigation, and regional differences. Yuan, Lian [

78] examined GHG emissions from constructed wetlands, emphasizing the role of planting strategies and management practices in reducing secondary pollution. Kabato, Getnet [

3] assessed climate-smart agriculture strategies, underscoring the benefits of integrated practices like biochar application, agroforestry, and regenerative agriculture for soil health and emission mitigation. Ref. [

79] synthesized evidence on converting cropland to grassland in peat soils, concluding that effects on CO

2, CH

4, and N

2O emissions remain ambiguous and context-dependent. Kukah, Jin [

30] reviewed the role of carbon trading, finding that it reduces GHG emissions through innovations in low-carbon technologies, renewable energy, and ecosystem restoration. The study demonstrated that recoupled crop–livestock systems in China could reduce agricultural GHG emissions by over 40%, highlighting their potential for sustainable intensification [

14].

Agricultural crop systems are central to global food security but simultaneously represent a major source of GHG emissions, particularly CO2, CH4, and N2O. Despite extensive research on individual mitigation practices, the sector continues to face significant challenges in balancing productivity with climate goals. Measurement uncertainties, limited socio-economic adoption of climate-smart practices, and policy–practice mismatches hinder the scalability of effective solutions. Moreover, most existing approaches focus narrowly on either technical interventions or emission inventories, leaving a gap in integrated frameworks that connect farm-level practices with regional and global mitigation outcomes. This disconnect underscores the urgent need for a comprehensive synthesis that not only reviews emission sources and mitigation strategies but also provides a structured pathway for practical, verifiable, and context-specific solutions to reduce agricultural GHG emissions.

Across the reviewed studies, several recurring gaps emerge. Many mitigation strategies such as biochar application, climate-smart agriculture, and crop–livestock integration show strong potential yet lack long-term field validation and region-specific performance data. Methodological inconsistencies in life cycle assessments of crops like tomatoes and soybeans limit comparability, highlighting the need for standardized boundaries and harmonized reporting. Ecosystem-based solutions such as constructed wetlands and land-use shifts provide valuable insights, but their GHG outcomes remain context-dependent and uncertain, requiring more robust monitoring frameworks. Socio-economic and policy barriers, including adoption constraints, insufficient incentives, and integration challenges with existing farming systems, are also insufficiently addressed, limiting scalability. Addressing these gaps through interdisciplinary, multi-scalar studies will be critical to designing effective, verifiable, and farmer-centered GHG mitigation strategies in agriculture.

ICEMF is a conceptual framework proposed in this review to address critical gaps in existing agricultural GHG mitigation approaches. Unlike the 4R nutrient stewardship framework, which provides agronomic guidance without scaling mechanisms [

18,

80], Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA), which sets national targets without farm-level implementation pathways [

81,

82], or (IAMs), which aggregate agriculture at regional scales that obscure local heterogeneity [

62,

63], ICEMF operates at the critical “middle layer” between national policy and farm practice (

Figure 2), addressing what [

83] identified as the fundamental challenge of cross-scale governance: linking local actions to global outcomes while maintaining context specificity.

(1) Spatially explicit emission modeling with practice-level integration: ICEMF connects field-validated effectiveness data (e.g., biochar reduces N

2O by 16.2% in temperate systems [

9] but 8–12% in tropical systems [

11]) with spatially explicit models that account for soil texture, climate zone, moisture regime, and management intensity. This enables context-specific emission predictions rather than applying universal effect sizes. For example, no-till agriculture exhibits a variability of −19% to +70% in N

2O responses, depending on soil–climate conditions [

12]; ICEMF’s spatial modeling captures this heterogeneity to guide where practices will succeed versus fail. ICEMF’s spatially explicit modeling approach recognizes that agricultural land use outcomes are fundamentally determined by spatial context [

84], requiring models that account for local soil–climate management interactions rather than applying universal coefficients

(2) Socio-economic adoption pathway integration: ICEMF incorporates adoption probability functions based on empirical farmer typologies. Systematic review of 35 years of adoption literature [

85] demonstrates that adoption is influenced by multidimensional factors beyond economic calculations, including risk perception, information access, social networks, and institutional support. Technical potential (e.g., precision fertilization: −55–64% N

2O [

18]) is adjusted by adoption factors including capital access (affecting 65–80% of smallholders [

23]), land tenure security (60% in sub-Saharan Africa [

24]), extension service ratios (1:1000–2000 in many regions [

53]), and gender disparities (women access only 10–20% of extension services [

25]). This translates technical potential to realistic scenarios: 25–35% implementation without support, increasing to 40–60% with bundled interventions [

28]. No existing framework quantitatively links biophysical effectiveness with adoption probability at operational scales.

Together, these contributions enable ICEMF to answer the following question: “If we implement practice X in region Y with farmer support level Z, what emission reduction will actually occur and contribute to national/global targets?” This operational specificity distinguishes ICEMF from conceptual frameworks (CSA), agronomic guidelines (4R), or macro-scale models (IAMs). The novel objectives of this study are as follows:

To systematically review GHG emissions from agricultural crop systems and evaluate the effectiveness of diverse management practices.

To assess the global mitigation potential of N2O emissions through optimized nitrogen fertilization and complementary agronomic interventions.

To develop and propose the ICEMF framework as a novel, scalable strategy for integrating technical, environmental, and socio-economic dimensions of GHG mitigation in agriculture.

1.3. Evaluating the Limitations of Current Agricultural GHG Mitigation Frameworks and the Potential of ICEMF to Bridge the Gaps

While the ICEMF offers a novel approach to bridging field-based practices with global emission reduction targets, several existing frameworks share similar goals of mitigating GHG emissions in agriculture. However, these frameworks often face significant challenges related to adoption, scalability, and integration of socio-economic factors. Below, we discuss a few of these frameworks and explain how ICEMF is positioned to overcome their limitations.

1.3.1. The 4R Nutrient Stewardship

The 4R nutrient stewardship framework: Right source at right rate, right time, and right place has been widely adopted globally as a science-based approach to optimize nitrogen fertilizer use [

80], with documented potential to reduce N

2O emissions by 55–64% when combined with EEF and improve nitrogen recovery efficiency [

18,

86]. While effective in many commercial farming contexts, the 4R framework faces significant challenges in context-specific adoption, as implementation is highly site-specific and regional challenges vary considerably across continents and farming systems [

3,

87]. The application of precision fertilization techniques aligned with 4R principles is often limited by technology access and knowledge gaps, especially in smallholder farming systems where farmers face barriers including limited resources, training, and financial support [

88]. These constraints are particularly acute in sub-Saharan Africa, where low digital literacy, high equipment costs, and weak extension services impede implementation [

89]. Additionally, the benefits of nutrient use efficiency optimization can be inconsistent across different soil types and climatic conditions, as regional environmental factors often equal or exceed the effects of specific fertilizer management practices on N

2O emissions and nutrient losses [

86]. Soil emissions occur in spatially and temporally variable “hot spots” and “hot moments,” driven by complex interactions among soil properties, weather, and microbial processes, making outcomes difficult to predict and generalize across regions [

90,

91]. ICEMF integrates spatially explicit emission models and considers socio-economic adoption pathways, ensuring that practices like precision fertilization are scalable and adaptable to local conditions. ICEMF’s inclusion of farmer decision-making factors, including financial incentives and training programs, helps overcome adoption barriers seen in the 4R framework.

1.3.2. Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA)

CSA aims to integrate climate adaptation, mitigation, and food security in a single framework [

81,

82]. While CSA has promoted practices such as agroforestry, crop diversification, and conservation tillage [

60,

92], it often lacks a clear mechanism for scaling these practices across diverse agricultural systems [

93]. The climate-smart village approach has attempted to provide an integrative strategy for scaling adaptation options, yet implementation remains challenging across heterogeneous farming contexts [

93]. Moreover, CSA’s emphasis on climate resilience sometimes overlooks the socio-economic conditions that influence farmers’ willingness to adopt these practices [

94,

95]. Recent evidence demonstrates that adoption barriers extend beyond technical feasibility to include economic constraints, limited extension access, and institutional factors [

96,

97]. Studies across West Africa reveal that while farmers recognize benefits of CSA practices, barriers such as high initial investment costs, lack of credit access, insufficient labor, and inadequate knowledge significantly impede widespread adoption [

98]. Similarly, research from southern Ethiopia and European food supply chains confirms that socio-economic factors including household wealth, market access, cooperative membership, and policy support critically determine technology adoption and farm sustainability outcomes [

99,

100]. The gap between indigenous knowledge systems and Western scientific approaches further complicates effective adaptation strategies, suggesting that CSA frameworks must better integrate local contexts and traditional practices to achieve meaningful impact [

101]. ICEMF provides a more integrated approach by combining technical practices with spatially explicit emission modeling and socio-economic adoption data. This makes ICEMF more actionable at the farm level, particularly in addressing barriers to farmer adoption and economic feasibility in low-resource regions.

1.3.3. Low-Emission Development Strategies (LEDS)

LEDS are national frameworks integrating climate mitigation with development planning across sectors, including agriculture [

102]. While valuable for macro-level policy coordination, LEDS face substantial implementation challenges in agriculture. Critical gaps exist between policy objectives and farm-level realities, particularly regarding the technical feasibility and economic viability of mitigation strategies for smallholder systems [

28,

103]. Research in sub-Saharan Africa demonstrates that, despite progressive CSA policies, adoption remains constrained by limited access to technology, inadequate extension services, insufficient financial resources, and weak institutional capacity [

29,

104]. Agricultural mitigation policies face socio-political barriers including competing priorities around food security and affordability, organized lobby pressures, and redistributive effects [

103]. Studies across Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Rwanda reveal persistent challenges in operationalizing LEDS locally due to trade-offs between agricultural expansion and environmental goals, donor dependence, and insufficient integration of local knowledge [

104]. The effectiveness of agricultural LEDS is fundamentally constrained by disconnects between national goals and farm-level adoption realities, with conventional top-down systems inadequate for promoting equitable access to climate-smart practices [

28,

29]. ICEMF fills the gap by integrating farm-level interventions with regional and global emission models, offering a scalable and adaptive solution that bridges the gap between national policies and local agricultural practices. Its focus on farmer-centered solutions and policy incentives ensures that emission reduction strategies are both practical and achievable.

1.3.4. Integrated Assessment Models

IAMs are global frameworks that integrate economic, energy, land-use, agricultural, and climate systems to evaluate the impacts of climate policies on agricultural emissions [

63,

105]. While valuable for global policy analysis and identifying cost-effective mitigation pathways [

106], IAMs face substantial limitations for real-world agricultural implementation. Critical gaps exist in capturing local specificities essential for farm-level adoption, as these models rely on highly aggregated regional representations that obscure within-region heterogeneity of farming systems, soil conditions, and farmer capacities [

107,

108]. IAMs have been criticized for problematic assumptions that underestimate transformation urgency and inadequately incorporate behavioral, institutional, and socio-political barriers to technology adoption [

109]. Specifically, IAMs represent agricultural mitigation through technology diffusion functions assuming rational economic optimization, without adequately capturing complex socio-economic factors driving farmer decisions, including risk aversion, cultural compatibility, perceived usefulness, financial constraints, extension service access, and social network influences [

110,

111,

112]. Research demonstrates that farmer technology adoption depends on multidimensional factors beyond economic calculations, with psychological dimensions (environmental values, innovation aversion), socio-demographics (age, education, farm size), resource endowments (land, labor, capital), and institutional contexts (extension services, policy incentives) all playing critical yet under-represented roles in IAM frameworks [

113,

114]. Consequently, while IAMs provide important macro-scale strategic insights, their agricultural projections lack the granularity and behavioral realism needed for context-specific implementation, necessitating complementary bottom-up approaches explicitly incorporating farmer heterogeneity and socio-institutional adoption determinants [

108,

113]. ICEMF offers a more granular approach by integrating field-level practices with global emission models. Unlike IAMs, ICEMF accounts for regional variations in soil types, climate, and farming systems, making it more relevant for on-the-ground implementation. Furthermore, ICEMF’s inclusion of socio-economic adoption pathways ensures that mitigation strategies are not only technically feasible but also economically viable for farmers.

Unlike existing frameworks that operate primarily at either field-level (4R, CSA) or macro-scale (LEDS, IAMs), ICEMF uniquely bridges these scales through three interconnected components: (1) empirical data integration from diverse field practices, (2) spatially explicit emission modeling that captures regional heterogeneity, and (3) socio-economic adoption pathways that ensure practical scalability. This multi-scalar integration enables ICEMF to translate local agricultural interventions into quantifiable contributions toward global emission reduction targets (

Supplementary Table S1).

1.4. The Integrated Crop Emission Mitigation Framework

To address the complexities of bridging field-level practices with global emission targets while accounting for socio-economic realities, this review introduces ICEMF as a novel synthesis framework that operationalizes multi-scale agricultural GHG mitigation.

Framework architecture: ICEMF operates through four hierarchical layers (

Figure 2): (1) global level—Integrated Assessment Models allocate carbon budgets across regions and sectors; (2) national level—low-emission development strategies translate global targets into sectoral commitments; (3) regional/state level—ICEMF occupies this critical operational layer, bridging national targets with farm implementation through practice selection, adoption modeling, and costed programs; (4) farm level—specific practices (4R nutrient stewardship, CSA practices) enable on-ground implementation.

Data flow and feedback mechanisms: The framework integrates three data streams (

Figure 1): (1) empirical data from field trials provide practice-specific emission factors (e.g., biochar: 16.2% N

2O reduction [

9]; 4R + EEF: 55–64% reduction [

18]); (2) spatially explicit emission models account for soil types, climate zones, and management regimes to generate region-specific mitigation potentials; and (3) socio-economic adoption pathways incorporate farmer constraints (capital access, and tenure, extension service availability) to adjust technical potential by realistic adoption probabilities. Information flows downward from carbon budgets to farm-level guidance, while monitoring data feeds upward (purple dashed arrow,

Figure 2), enabling adaptive management that continuously refines emission factors, practice recommendations, and policy mechanisms based on observed field performance.

Operational distinctiveness: Unlike existing frameworks that operate primarily at field-level (4R, CSA) or macro-scale (LEDS, IAMs), ICEMF uniquely bridges these scales through three interconnected components: (1) empirical data integration from diverse field practices; (2) spatially explicit emission modeling capturing regional heterogeneity in soil, climate, and farming systems; and (3) socio-economic adoption pathways ensuring practical scalability by adjusting technical potential (e.g., biochar’s 16.2% N

2O reduction) by realistic adoption rates (5–10% baseline, increasing to 40–60% with bundled support [

28]. This multi-scalar integration enables ICEMF to translate local agricultural interventions into quantifiable contributions toward global emission reduction targets while maintaining farmer-centered feasibility.

Implementation pathway: ICEMF is currently in a conceptual stage, with application potential illustrated through schematic representations (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) and validated through five regional case studies demonstrating how the framework adapts to diverse agricultural systems, from Indonesian agroforestry (74–320 Mg C ha

−1 sequestration) to German biochar application (consistent 16.2% N

2O reduction) to Indian precision fertilization (12–20% emission reductions).

2. Materials and Methods

The literature search was conducted using major academic databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Springer, MDPI, Taylor & Francis, Cambridge Journals, and Google Scholar to ensure comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed studies on GHG emissions from agricultural crops and mitigation strategies. These databases were specifically selected for their extensive archives of peer-reviewed academic journals in agricultural sciences, environmental sciences, climate change mitigation, and precision agriculture. This approach ensured that sourced articles were of high academic and scientific rigor and directly relevant to our research themes.

This review covers research papers published from 1997 to 2025. The selected articles were organized and discussed within the relevant thematic sections of the manuscript. Search terms employed in the database queries included various combinations of keywords such as “greenhouse gas emissions,” “agricultural crops,” “mitigation,” “management practices,” “climate-smart agriculture, “digital agriculture technologies,” “monitoring and verification,” and “socio-economic adoption.” This specific selection of keywords aimed to encompass a broad spectrum of research topics within the scope of agricultural practices and their environmental impacts. Additional references were traced through citation tracking of key articles to capture significant contributions not directly retrieved in the initial search. Studies were included if they focused on GHG emissions from agricultural crop systems and examined mitigation or management strategies with relevance to CO2, CH4, or N2O. Only peer-reviewed articles published in English were selected to ensure recent and reliable findings. Exclusion criteria comprised studies that addressed emissions unrelated to crops (e.g., purely livestock systems), articles without empirical or methodological relevance, non-English publications, and gray literature such as reports or opinion pieces.

From the eligible studies, key information such as author details, year of publication, study location, crop type, greenhouse gases assessed, and mitigation practices investigated was extracted. Over 350 studies were initially identified and screened for their relevance. After screening for relevance, 244 studies met the inclusion criteria and were thoroughly analyzed and included in the final review. Studies were categorized according to thematic domains relevant to the ICEMF: (1) GHG emission sources and quantification: papers reporting emission measurements, emission factors, or spatial–temporal variability of CO2, CH4, and N2O from crop systems. (2) Practice-level mitigation strategies: research on specific interventions including biochar application, precision nutrient management, conservation tillage, crop rotation, agroforestry, cover cropping, crop diversification, and crop–livestock integration. (3) Digital agriculture technologies: studies addressing IoT sensors, remote sensing, precision agriculture platforms, wireless sensor networks (WSN), satellite monitoring, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and AI/machine learning applications. (4) MRV systems: papers on emission measurement protocols, carbon accounting methodologies, life cycle assessments, and verification frameworks. (5) Socio-economic adoption and implementation: research on farmer adoption barriers, cost-effectiveness analyses, policy frameworks, and extension service delivery. A narrative synthesis approach was adopted to integrate findings across diverse study designs, with emphasis on identifying common trends, contradictions, and knowledge gaps. Where possible, comparisons were drawn between regional and global perspectives to highlight context-specific variations in emission sources and mitigation outcomes. While this framework supports a comprehensive synthesis, several limitations remain. Variability in study designs, life cycle assessment boundaries, and measurement techniques restrict direct comparability of results. In addition, regional disparities in data availability create potential biases toward well-studied systems, while socio-economic dimensions are often underreported. These limitations underscore the need for standardized methodologies and long-term, context-specific studies to strengthen the evidence base.

This review synthesizes evidence on agricultural GHG mitigation practices and proposes ICEMF as a conceptual framework to integrate dispersed knowledge into an operational decision-support approach. The review is structured to (1) evaluate practice-level effectiveness across diverse interventions, (2) identify critical gaps in existing frameworks, and (3) propose ICEMF’s novel integration of spatial modeling with adoption pathways as a solution to bridge field-to-policy scales (

Figure 2). Unlike previous reviews focusing on single practices or policy frameworks, this review’s novelty lies in synthesizing cross-scale evidence to demonstrate how ICEMF’s two core innovations (spatially explicit modeling + adoption integration) address the operational gap between technical potential and achievable impact (

Figure 2).

2.1. Meta-Analysis Interpretation and Quality Assessment

We report effect sizes from published meta-analyses, including 95% confidence intervals (CIs), sample sizes (both the number of observations and the number of studies), heterogeneity measures (I2 statistic), and assessments of publication bias. Heterogeneity interpretation follows standard guidelines: I2 values of 0–25% indicate low heterogeneity, 25–50% moderate, 50–75% substantial, and >75% considerable heterogeneity requiring careful interpretation of context-specific factors.

Quality assessment of meta-analytic evidence considered:

- (1)

Sample size (>50 observations considered high quality)

- (2)

Heterogeneity assessment and subgroup analyses

- (3)

Publication bias testing (funnel plots, Egger’s test)

- (4)

Climate and soil stratification

- (5)

Duration of included studies (>2 years preferred for agricultural practices). Practices were assigned quality scores of HIGH (meeting 4–5 criteria), MODERATE (2–3 criteria), or LOW (0–1 criteria) to guide the interpretation of evidence strength (

Supplementary Table S2).

2.2. Limitations of Meta-Analytic Evidence

Several limitations constrain the interpretation of the meta-analytic findings presented in this review: (1) High heterogeneity (I2 > 75% for several practices) indicates substantial context-dependency, requiring careful extrapolation beyond the specific soil–climate management conditions of original studies. (2) Publication bias, where detected, may lead to overestimation of effect sizes as studies with null or negative results are less likely to be published. (3) Long-term field validation (>10 years) remains limited for many practices, with most studies spanning 1–6 years, creating uncertainty about persistence of mitigation effects. (4) Tropical and semi-arid systems are underrepresented relative to temperate zones in meta-analytic datasets, limiting confidence in global extrapolation. (5) Interaction effects between practices (e.g., biochar combined with precision fertilization) are rarely quantified in existing syntheses, preventing assessment of synergistic or antagonistic outcomes. These limitations underscore ICEMF’s emphasis on spatially explicit modeling that accounts for local context rather than applying universal effect sizes.

2.3. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

We evaluated evidence quality using a structured rubric assessing experimental design (randomization, replication), study duration, GHG measurement methods, statistical power, and context reporting. Meta-analyses were additionally evaluated for sample size (≥100 observations preferred), heterogeneity assessment (I

2), publication bias testing, and climate/soil stratification. Studies were classified as high (8–10 points), moderate (5–7 points), or low quality (0–4 points). Five primary bias sources were identified: publication bias (positive results are preferentially published), measurement bias (high coefficient of variation in GHG fluxes: 30–300%), duration bias (most studies < 3 years), geographic bias (temperate regions overrepresented), and interaction bias (single-practice focus). Key meta-analyses cited for quantitative effect sizes varied in quality. High-quality meta-analyses (biochar [

9], cover crops [

115]) scored ≥ 8/10 with >100 observations, formal bias testing, and climate stratification. Additional meta-analyses (no-till [

115]) provided moderate-quality evidence with context-specific findings. Complete quality assessment rubrics, scoring criteria, individual study evaluations, coefficient of variation analysis, and detailed bias mitigation strategies are provided in

Supplementary Table S2.

2.4. Synthesis of Context-Specific Effectiveness

To enable systematic comparison of mitigation practice effectiveness across diverse agroecological contexts, we organized extracted data into a comprehensive impact matrix structured by three dimensions: (1) climatic zone (temperate, tropical, subtropical, humid, semi-arid), (2) soil texture and characteristics (acidic soils, clay, sandy, paddy soils, various textures), and (3) cropping system (rice, wheat, corn/maize, vegetables, mixed systems, general cropland).

For each practice-context combination, we compiled quantitative impacts on N2O, CH4, and CO2 emissions, soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration, yield effects, and practice durability. We extracted heterogeneity measures (I2 statistics) from meta-analyses to assess consistency of effects across studies, with I2 values of 0–25% indicating low heterogeneity, 25–50% moderate, 50–75% substantial, and >75% considerable heterogeneity. Where available, we reported 95% CI to quantify estimation uncertainty.

Evidence quality for each practice-context combination was rated using a structured rubric assessing: (i) sample size (≥100 observations preferred for high quality), (ii) formal heterogeneity assessment and subgroup analyses, (iii) publication bias testing (funnel plots, Egger’s test), (iv) climate and soil stratification, and (v) study duration (≥2 years for agricultural practices). Practices were assigned quality scores of HIGH (8–10 points, meeting 4–5 criteria), MODERATE (5–7 points, meeting 2–3 criteria), or LOW (0–4 points, meeting 0–1 criteria) to guide interpretation of evidence strength and generalizability.

This matrix structure enables identification of (1) context-specific effectiveness patterns informing spatially explicit implementation strategies, (2) practices with consistent versus variable responses across contexts, (3) knowledge gaps requiring additional research investment, and (4) mechanistic insights into soil–climate management interactions determining mitigation outcomes. The synthesis directly supports ICEMF’s first core innovation, spatially explicit emission modeling that accounts for local context rather than applying universal effect sizes across heterogeneous landscapes.

2.5. Baseline Specification and Sequential Accounting for Nitrogen Management

All nitrogen optimization mitigation estimates in ICEMF use standardized baselines to ensure comparability and prevent double counting. For intensive temperate cereal systems, the reference baseline is 165–190 kg N ha

−1 synthetic fertilizer application (representative of US Corn Belt maize and European wheat), corresponding to 1.8–4.6 kg N

2O-N ha

−1 yr

−1 depending on soil texture, water-filled pore space, and climate [

18,

86,

91]. Regional baselines vary substantially: 200–250 kg N ha

−1 in intensive Asian rice-wheat systems [

116], 120–160 kg N ha

−1 in moderate-input temperate systems [

117], and 40–80 kg N ha

−1 in smallholder African systems [

118].

ICEMF incorporates region-specific N

2O emission factors (percentage of applied nitrogen emitted as N

2O-N) ranging from 0.5–1.5% in temperate dry climates to 1.5–3.0% in temperate humid climates, accounting for soil–climate interactions affecting denitrification and nitrification processes [

18,

86,

119]. These emission factors scale field-level nitrogen management interventions to regional mitigation estimates while capturing non-linear emission responses at high nitrogen application rates (exponential increase, β = 1.6–2.0) [

119].

To prevent double-counting when multiple nitrogen management practices are combined, ICEMF employs sequential accounting where the first practice modifies the baseline for subsequent interventions. For example, legume-based crop rotation reduces synthetic nitrogen requirements from 180 to 63 kg N ha

−1 and decreases N

2O emissions by 39% [

120,

121]; applying precision fertilization (4R stewardship) to this reduced nitrogen baseline achieves an additional 55–64% reduction in remaining emissions [

18], yielding a total sequential reduction of 70–75% rather than an impossible additive 94–103%. Similarly, biochar application (16.2% N

2O reduction) [

9] combined with precision fertilization targets overlapping nitrogen transformation pathways; field validation studies document combined reductions of 38.8% [

122] rather than the theoretical additive 71%, confirming the necessity of sequential accounting. This approach ensures ICEMF provides conservative, verifiable mitigation estimates for bundled practice scenarios.

4. Addressing Gaps in ICEMF

While the ICEMF presents a novel approach to connecting farm-level agricultural practices with GHG reduction targets, several key gaps must be addressed to enhance its applicability, scalability, and long-term effectiveness. These gaps are outlined in the following areas: long-term validation, improved socio-economic adoption data, region-specific case studies, and methodological inconsistencies.

4.1. Long-Term Validation

ICEMF’s current theoretical stage requires long-term field validation to assess the sustained impact of the proposed mitigation strategies. Although empirical data support the potential for emission reductions through practices such as agroforestry, reduced tillage, and biochar application, significant uncertainty remains about the long-term effectiveness of these strategies. For example, how do soil health improvements and GHG reductions evolve over multiple growing seasons or decades? Long-term studies will be essential to capture seasonal variability, the impacts of climate change, and the effects of soil regeneration, ensuring that mitigation practices are both reliable and adaptive over time. Moreover, there is a need for field trials that compare ICEMF-driven practices with conventional farming systems to confirm the real-world benefits across diverse agricultural systems.

4.2. Improved Socio-Economic Adoption Data

One of the significant challenges facing the ICEMF framework is the adoption of mitigation strategies by farmers, particularly in low-resource and smallholder contexts. The integration of socio-economic data into ICEMF is crucial for understanding the barriers to adoption and how socio-economic conditions influence farmers’ decision-making. These conditions include access to capital, knowledge, technology, and secure land tenure. For instance, the upfront costs of implementing ICEMF-based practices such as biochar application or precision fertilization may deter farmers from adopting them. Studies show that farmers in developing regions face substantial barriers, including limited access to credit, perceived risks, and a lack of market incentives [

23]. To address these barriers, more data is needed on farmer behavior, the effectiveness of financial incentives (e.g., carbon credits), and how government policies can support adoption. Integrating socio-economic modeling into ICEMF will provide better insights into how policies, subsidies, and training programs can be structured to encourage widespread adoption of GHG mitigation practices.

4.3. Region-Specific Case Studies

While ICEMF offers a global framework for agricultural GHG mitigation, its effectiveness will vary significantly across regions due to differences in climatic conditions, soil types, and farming systems. There is a lack of region-specific case studies that demonstrate how ICEMF can be tailored to local conditions. For example, while agroforestry may be a highly effective practice in tropical regions, its applicability in temperate regions may be more limited due to differences in crop types and climate conditions. Likewise, practices like no-till farming may have varying degrees of effectiveness depending on soil texture, precipitation patterns, and crop rotation systems. Region-specific case studies are critical for testing the framework’s adaptability and for refining ICEMF to meet the unique needs of different agricultural systems. In particular, there is a need for cross-regional comparisons that evaluate how the same practice may result in different outcomes in terms of GHG reductions, productivity, and economic viability. These studies will help policymakers and farmers understand how to adapt mitigation strategies to suit local contexts and increase the scalability of ICEMF.

4.4. Methodological Inconsistencies and Standardization

Another critical gap is the lack of standardized methodologies for measuring the impact of ICEMF on GHG emissions. Currently, there is a wide variation in how emission reductions are quantified across studies, with differing methods, emission factors, and LCA boundaries. This inconsistency makes it challenging to compare results across regions and systems. To strengthen ICEMF, there is a need for harmonized metrics for emission measurement that can be applied consistently across diverse agricultural practices and environmental contexts. Furthermore, the integration of advanced technologies, such as remote sensing, AI, and machine learning, can enhance the accuracy and scalability of emission modeling, ensuring that ICEMF can be applied to a variety of farming systems globally. Standardizing MRV systems will also be crucial for tracking the progress of mitigation strategies and ensuring that they meet global GHG reduction targets.

4.5. Bridging Gaps Through ICEMF: From Theory to Practice

ICEMF operationalizes gap resolution through integrated mechanisms linking policy to implementation across four dimensions.

Long-term validation: Three-tiered monitoring infrastructure addresses validation needs while reducing costs. Research sites (

n = 50 globally) establish regional emission factors feeding national inventories [

208,

209]; demonstration farms (

n = 2000 per region) prove effectiveness and inform subsidy design [

198,

199]; participant farms use remote sensing verification at <USD 25 ha

−1 transaction costs enabling smallholder inclusion [

21,

66,

67]. Implementation: Years 1–4 establish tiers sequentially, requiring national coordination units linking research, extension, and statistics agencies.

Socio-economic adoption: Farmer typology frameworks differentiate pathways by resource level. Commercial farms (20%) receive technology-intensive portfolios with carbon credits; moderate smallholders (50%) access knowledge-intensive practices with bundled credit and extension; constrained smallholders (30%) prioritize low-cost improvements with safety nets [

51,

53,

54,

55]. Annual surveys (10,000 farmers/region) track barriers enabling targeted support. Example: Kenya tenure assessment shifted priority from agroforestry to legume rotations, increasing adoption from 15% to 42% [

24,

52].

Regional specificity: Nested spatial modeling maintains comparability while accommodating context through: (1) global framework establishing uniform protocols [

66,

208]; (2) regional parameterization providing climate-specific factors (biochar: 16.2% temperate vs. 8–12% tropical N

2O reduction) [

9,

10,

11]; (3) farm-adaptive management allowing local adjustments [

201,

202]. Timeline: Years 1–4 develop and calibrate protocols, requiring regional modeling hubs with 50–100 staff.

Methodological standardization: Open-source digital infrastructure integrates mobile apps, satellite imagery, cloud-based models, and decision-support interfaces [

18,

68,

69]. Transaction costs were reduced from USD 150 to USD 18 ha

−1, enabling the participation of Ethiopia’s 340,000 smallholders via a USSD-based system [

66,

67].

Implementation: Years 1–3 develop platforms and train 5000 extension agents.

Integration: Solutions interlock through bidirectional flows, national targets inform regional plans and farmer recommendations, and farmer outcomes refine parameters and policy targeting, operationalized via nested institutions from international coordination to farmer cooperatives.

5. Bridging the Gaps with Case Studies

To demonstrate the practicality and applicability of the ICEMF, several real-world case studies offer valuable insights into the framework’s potential to reduce agricultural GHG emissions while maintaining productivity. The following case studies showcase how agricultural practices integrated into the ICEMF framework contribute to global emission reduction targets and regional sustainability goals.

(1) Agroforestry in Indonesia, particularly in West Java, has been utilized to mitigate carbon emissions and promote biodiversity. Carbon stocks in agroforestry systems range from 74 to 320 Mg ha

−1, depending on system age and tree diversity, with mixed-tree systems exhibiting the highest sequestration potential [

170]. While agroforestry contributes to GHG mitigation, its effects on CH

4 and N

2O emissions vary by system. Soils under agroforestry release an average of 1.6 kg CH

4 ha

−1 yr

−1 and 7.7 kg N

2O ha

−1 yr

−1 [

11]. High rainfall and fluctuations in moisture pose challenges to nitrogen cycling and N

2O emissions, affecting long-term sustainability. ICEMF’s spatial emission modeling can predict the effectiveness of agroforestry in such regions, considering local soil types and moisture levels to optimize GHG reductions. Additionally, socio-economic adoption pathways would help tailor policies and incentives to farmers’ needs, supporting widespread adoption.

(2) No-till farming in the United States has shown greater soil carbon accumulation and lower global warming impact compared to conventional tilling, primarily due to increased carbon storage rather than direct CO

2 emission reductions [

242]. However, the effectiveness of no-till may be limited in tropical regions, such as Southeast Asia, due to soil compaction and high rainfall. ICEMF’s approach would evaluate the effectiveness of no-till practices in temperate areas, using models that consider local soil moisture and crop types, while also recommending adaptive techniques and socio-economic support for farmers to implement this practice.

(3) In Germany and other temperate European regions, biochar has been shown to reduce soil N

2O emissions by 16.2% across various agricultural systems [

9]. Long-term studies confirm its effectiveness in reducing N

2O even after 4–6 years, contributing to sustained climate mitigation and improved soil quality [

10]. Biochar’s impact is most pronounced in temperate zones, where seasonal fluctuations have less effect on microbial activity. In tropical climates, its effectiveness may be reduced due to high moisture and rapid decomposition of organic matter. ICEMF would model biochar’s long-term effectiveness in different climates, providing region-specific recommendations based on local soil and moisture conditions to optimize GHG mitigation.

(4) Precision fertilization in India. In the Indo-Gangetic Plains of India, the Nutrient Expert (NE) tool for site-specific nutrient management has reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 2.5% in rice and 12–20% in wheat compared to conventional fertilization practices [

173]. Precision nitrogen management tools, such as leaf color charts, have reduced N fertilizer application by up to 51 kg N/ha in rice and 29 kg N/ha in wheat [

174] However, chronic over-fertilization remains a challenge, leading to soil health deterioration [

175]. ICEMF can integrate precision fertilization into spatial emission models, optimizing fertilizer use based on regional soil, climate, and crop conditions. The framework would also support adoption by offering financial incentives and knowledge-sharing programs to farmers in low-resource regions.

(5) Crop rotation and legume integration in Europe [

121]. Crop rotation, especially legume integration, is a valuable strategy in ICEMF’s toolkit for enhancing soil health and mitigating GHG. ICEMF can integrate legume-based crop rotations into its regional emission models, using spatially explicit data to assess how soil types, climate conditions, and crop management systems influence GHG reductions and carbon sequestration. The framework can assess the carbon sequestration potential of different crop rotations across various regions, helping tailor mitigation strategies based on local soil and climate conditions.

While ICEMF demonstrates substantial technical potential with documented practice-level reductions including biochar (16.2% N

2O reduction), precision fertilization (55–64% N

2O reduction), legume rotations (39% N

2O reduction + 18% soil organic carbon increase), agroforestry (74–320 Mg C ha

−1 sequestration), and rice management (84% CH

4 reduction) [

9,

10,

18,

160,

161], translating these field-validated practices to global scale faces fundamental challenges: (1) financial barriers: upfront costs of USD 200–50,000 per farm for proven practices (biochar, precision technologies) exceed the capacity of 65–80% of smallholder farmers lacking credit access [

20,

23]; (2) institutional capacity gaps: extension service ratios of 1:1000–2000 farmers is insufficient for knowledge-intensive practices, with approximately 70% of farmers in Kenya unaware national CSA policies exist [

24,

29]; (3) political economy barriers: subsidy reform is politically sensitive, as demonstrated by Punjab’s persistent over-fertilization despite available precision tools [

191]; (4) temporal mismatches: agroforestry’s 10–15-year payback is incompatible with farmers’ planning horizons without bridging mechanisms, such as payments for ecosystem services [

31,

198]. Realistic implementation achieves 25–35% of technical potential without bundled interventions, increasing to 40–60% with comprehensive financial, training, and institutional support [

23,

28]. Success requires parallel tracks: concentrating resources where enabling conditions exist (such as commercial farms and strong institutions) while building capacity in smallholder systems through progressive, complex approaches.

7. Conclusions

This review highlights the central role of agricultural crop systems in global GHG emissions and the diverse strategies available for mitigation. Practices such as conservation tillage, biochar application, precision nutrient management, crop diversification, and integrated crop–livestock systems show strong potential to reduce emissions while enhancing soil health and productivity. However, significant gaps remain in the literature. One major issue is the lack of long-term validation of these strategies across diverse regions and environmental conditions. Additionally, while much focus has been placed on the technical potential of these interventions, socio-economic barriers, such as land tenure issues and financial limitations, have not been sufficiently addressed.

Thematic analysis reveals that soil-based, crop-based, nutrient-oriented, and policy-driven measures are interconnected, yielding cumulative benefits when implemented in conjunction. However, their effectiveness remains context-dependent, shaped by regional conditions, socio-economic constraints, and policy frameworks. The importance of addressing these gaps is evident: without consideration of socio-economic factors, the scalability of these practices is limited, particularly in developing regions. Moreover, without proper long-term validation, the actual impact of mitigation strategies on GHG emissions remains uncertain.

The proposed ICEMF provides a novel pathway for linking practice-level interventions with global mitigation goals, offering both scientific and practical insights. To achieve meaningful emission reductions, strategies must be adapted to local realities, supported by enabling policies, and scaled through inclusive, farmer-centered approaches that align agricultural development with climate objectives. To move forward, future research should prioritize region-specific field trials and the development of integrated decision-support tools that combine technical, environmental, and socio-economic data. These tools will ensure that mitigation strategies are not only practical but also equitable and scalable, enabling policymakers to design inclusive and sustainable solutions to combat climate change.