Green Manure Enables Reduced Water and Nitrogen Inputs with Sustained Yield in Maize

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

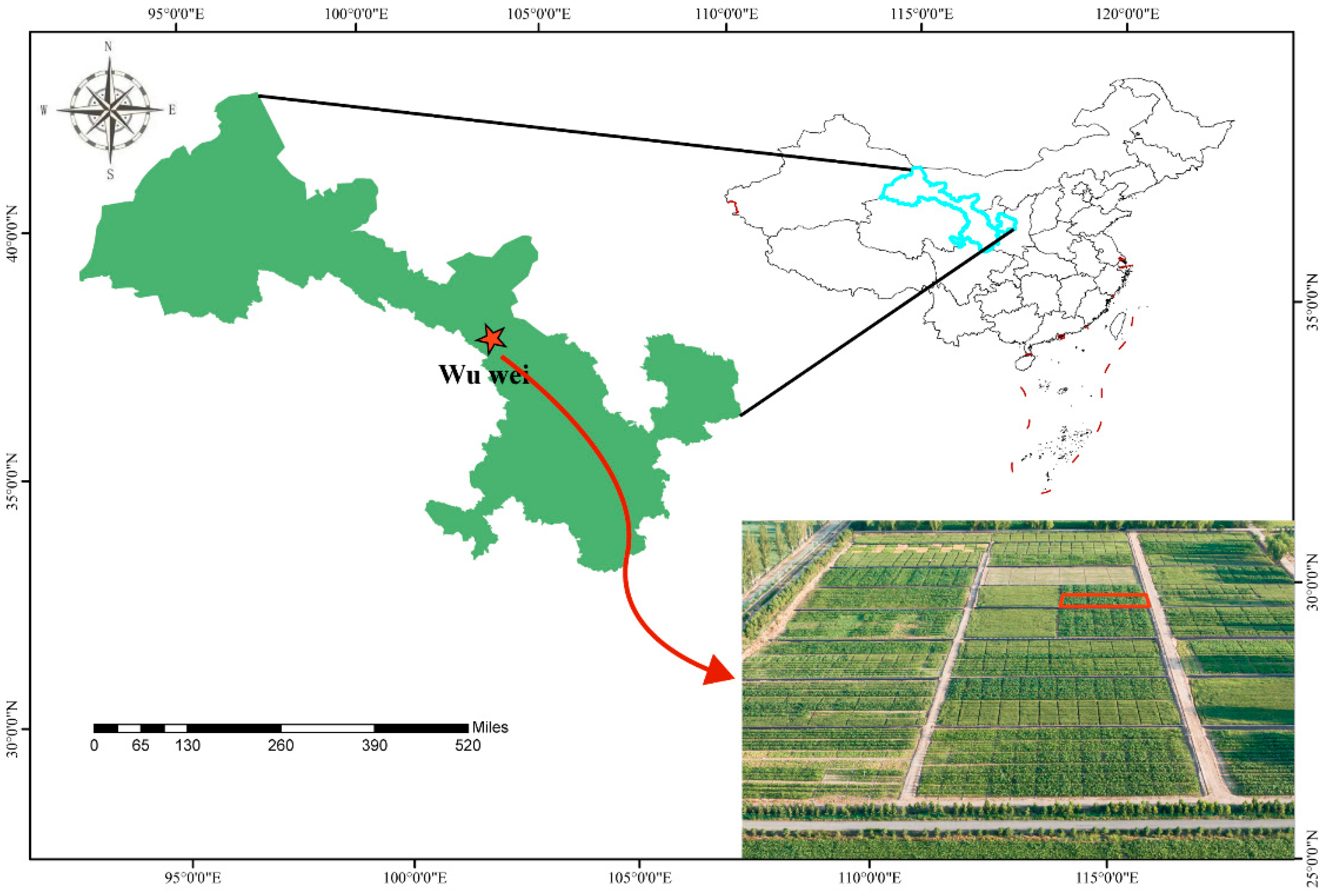

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Measurement and Calculation

2.3.1. Soil Water Content (SWC)

2.3.2. Soil Total Nitrogen (STN)

2.3.3. Leaf Area Index (LAI) and Leaf Area Duration (LAD)

2.3.4. Net Photosynthetic Rate (Pn), Transpiration Rate (Tr), and Relative Chlorophyll Content (SPAD)

2.3.5. Dry Matter (DM)

2.3.6. Grain Yield (GY)

2.3.7. Water Use Efficiency (WUE)

2.3.8. Nitrogen Utilization Efficiency for Grain Yield (NUtEg)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. WUE and NUtEg

3.2. GY and Its Constituent Factors

3.3. DM

3.4. LAI

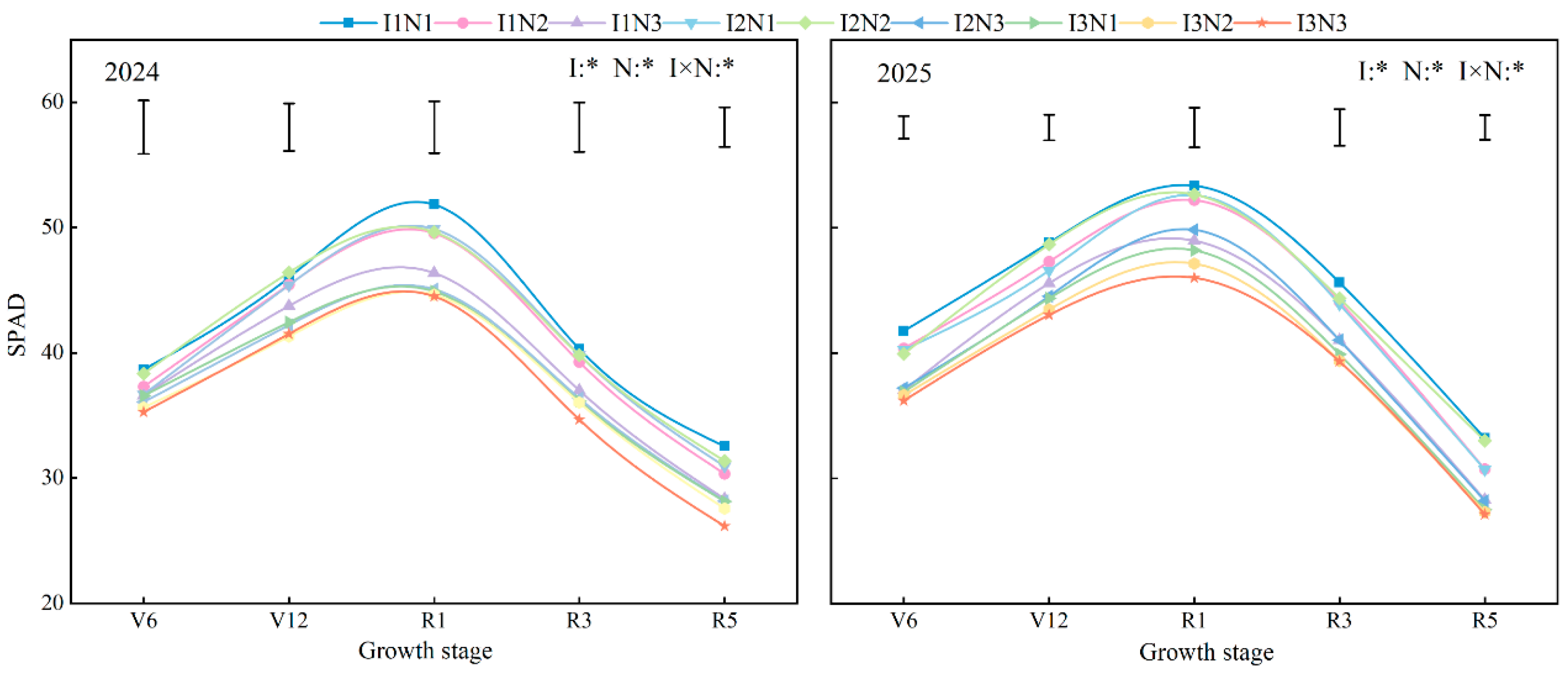

3.5. SPAD

3.6. Pn and Tr

3.7. SWC

3.8. STN

3.9. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

4. Discussion

4.1. Green Manure Incorporation Combined with Water-Nitrogen Reduction Stable GY and Improved WUE and NUtEg

4.2. Green Manure Incorporation Combined with Water and Nitrogen Reduction Optimizes Maize Canopy Characteristics and Dry Matter Accumulation

4.3. Water and Nitrogen Reduction Under Green Manure Incorporation Improves the Soil Water–Nitrogen Environment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture 2021—Systems at Breaking Point; Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, B.; Wang, X.H.; Groenigen, K.J.V.; Bruce, A.L.; Christoph, M.; Li, T.; Yang, J.C.; Jonas, J.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, F. Improved alternate wetting and drying irrigation increases global water productivity. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.M.; Ren, C.C.; Zhang, X.M.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.T.; Ma, B.; He, Y.; Hu, L.F.; Liu, X.M.; Zhang, F.Z.; et al. Soil health contributes to variations in crop production and nitrogen use efficiency. Nat. Food 2025, 6, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.M.; Li, Z.F.; Zhan, H.B.; Yang, S.F. Effect of long-term saline mulched drip irrigation on soil-groundwater environ-ment in arid Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ding, D.W.; Zhang, Y.M.; Li, P.; Li, K.Y.; Ruan, T.H.; Han, Y.; Ma, C.Y. Evaluation of carrying capacity of agricultural water and soil resources and targeted regional management in Northwest China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 395, 127841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.P.; Li, G.L.; Liang, H.; Liu, R.; Ma, Z.B.; Gao, S.J.; Chang, D.N.; Liu, J.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L.; et al. Green manure coupled with straw returning increases soil organic carbon via decreased priming effect and enhanced microbial carbon pump. Global Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, H.; Ye, Y.L.; Cui, Z.L.; Chen, X.P. Managing nitrogen for sustainable wheat production. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.H.; Liu, Y.; Guo, J.R.; Zhang, W.Q.; Xu, R.L.; Zhou, B.J.; Xiao, X.C.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.H.; et al. Novel annual nitrogen management strategy improves crop yield and reduces greenhouse gas emissions in wheat-maize rotation systems under limited irrigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukicevich, E.; Lowery, T.; Bowen, P.; Úrbez-Torres, J.R.; Hart, M. Cover crops to increase soil microbial diversity and mitigate decline in perennial agriculture. a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tian, Q.; Yu, Y.; Li, M.; Li, C. Water-Saving efficiency and inequality of virtual water trade in China. Water 2021, 13, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, M.; Hussain, T.; Jiang, H.; Ahmad, A.; Yao, J.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Min, L.; Shen, Y. Water-saving potential of subsurface drip irrigation for winter wheat. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Kim, S.U.; Han, H.R.; Hur, D.Y.; Owens, V.N.; Kumar, S.; Hong, C.O. Mitigation of global warming potential and greenhouse gas intensity in arable soil with green manure as source of nitrogen. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 288, 117724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, W.; Kataoka, R. Green manure incorporation accelerates enzyme activity, plant growth, and changes in the fungal community of soil. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naher, U.A.; Choudhury, A.T.M.A.; Biswas, J.C.; Panhwar, Q.A.; Kennedy, I.R. Prospects of using leguminous green manuring crop sesbania rostrata for supplementing fertilizer nitrogen in rice production and control of environmental pollution. J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 43, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.L. Effects of biological nitrogen fixation and plow-down of green manure crop on rice yield and soil nitrogen in paddy field. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2011, 48, 797–803. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Lee, G.J. Green manure improves humification and aggregate stability in paddy soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 206, 109796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, Y.L.; Lyu, H.Q.; Fan, Z.L.; Hu, F.L.; He, W.; Yin, W.; Zhao, C.; Chai, Q.; Yu, A.Z. No-tillage mulch with legu-minous green manure retention reduces soil evaporation and increases yield and water productivity of maize. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 290, 108573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.Q.; Yu, A.Z.; Chai, Q.; Wang, Y.L.; Wang, F.; Wang, P.F.; Shang, Y.P. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi mediate soil N dy-namics, mitigating N2O emissions and N-leaching while promoting crop N uptake in green manure systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.F.; Yu, A.Z.; Wang, Y.L.; Su, X.X.; Li, Y.; Lyu, H.Q.; Chai, J.; Yang, H.W. Effects of returning green manure to field combined with reducing nitrogen application on the dry matter accumulation, distribution and yield of maize. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2023, 56, 1283–1294. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cossani, C.M.; Sadras, V. Water-nitrogen colimitation in grain crops. Adv. Agron. 2018, 150, 231–274. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wen, X.; Liao, Y. Coupling effects of plastic film mulching and urea types on water use efficiency and grain yield of maize in the Loess plateau, China. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 157, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yin, W.; Fan, H.; Fan, Z.L.; Hu, F.L.; Yu, A.Z.; Zhao, C.; Chai, Q.; Aziiba, E.A.; Zhang, X.J. Photosynthetic physiological characteristics of water and nitrogen coupling for enhanced high-density tolerance and increased yield of maize in arid irriga-tion regions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 726568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Fei, L.; Peng, Y.; Gao, Y. Temperature-driven regulatory mechanism of dry matter accumulation and yield optimization in summer maize under mulched water-nitrogen coupling. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 24, 102442. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.Y.; Li, P.; Wei, J.G.; Fan, H.; He, W.; Fan, Z.L.; Hu, F.L.; Chai, Q.; Yin, W. Effect of reduced irrigation and combined ap-plication of organic and chemical fertilizers on photosynthetic physiology, grain yield and quality of maize in northwestern ir-rigation areas. Acta Agric. Sin. 2024, 50, 1065–1079. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Xie, R.Z.; Ming, B.; Wang, K.R.; Hou, P.; Chen, J.L.; Liu, G.Z.; Zhang, G.Q.; Xue, J.; Li, S.K. Dry matter accumulation after silking and kernel weight are the key factors for increasing maize yield and water use efficiency. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 254, 106938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.L.; Zhang, F.C.; Fan, X.K.; Fan, J.L.; Wang, Y.; Zou, H.Y.; Wang, H.D.; Li, G.D. Determining irrigation amount and fertilization rate to simultaneously optimize grain yield, grain nitrogen accumulation and economic benefit of drip-fertigated spring maize in northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piri, H.; Naserin, A. Effect of different levels of water, applied nitrogen and irrigation methods on yield, yield components and IWUE of onion. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 268, 109361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashhadi, B.S.; Nadi, M.; Naftchali, A.D.; Soqanloo, S.S. Improving sustainability of rice-canola rotation through water and nitrogen management in a humid region. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 305, 109106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, T.; Sharma, P.K.; Brar, A.S.; Vashisht, B.B.; Choudhary, A.K. Optimizing crop water productivity and delineating root architecture and water balance in cotton-wheat cropping system through sub-surface drip irrigation and foliar fertilization strategy in an alluvial soil. Field Crops Res. 2024, 309, 109337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulakh, M.S.; Singh, D.; Sadana, U.S. Direct and Direct and residual effects of green manure and fertilizer nitrogen in a rice-rapeseed production system in the semiarid subtropics. J. Sustain. Agric. 2005, 25, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Chen, J.; Shi, J.L.; Tian, X.H. Legume green manure further improves the effects of fertilization on the long-term yield and water and nitrogen utilization of winter wheat in rainfed agriculture. Plants 2025, 14, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.K.; Yin, L.N.; Ju, W.L.; Li, X.K.; Liu, X.X.; Deng, X.P.; Wang, S.W. Meta-analysis of green manure effects on soil proper-ties and crop yield in northern China. Field Crops Res. 2021, 266, 108146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Yu, A.Z.; Wang, P.F.; Wang, Y.L.; Shang, Y.P.; Zhang, D.L.; Liu, Y.L.; Pang, X.N.; Jiang, K.Q.; Huo, J.Z.; et al. Green manure incorporation with nitrogen reduction improves water productivity of spring wheat in arid areas. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 318, 109706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.F.; Yu, A.Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.L.; Lyu, H.Q.; Shang, Y.P.; Yang, X.H.; Liu, Y.L.; Yin, B.; Zhang, D.L.; et al. Nitrogen reduction by 20 % with green manure retention reduces soil evaporation, promotes maize transpiration and improves water productivity in arid areas. Field Crops Res. 2024, 315, 109488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.Q.; Yu, A.Z.; Chai, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.L.; Wang, P.; Shang, Y.P.; Yang, X.H. No-tillage with total green manure in-corporation: A better strategy to higher maize yield and nitrogen uptake in arid irrigation areas. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 3403–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, C.X.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Gao, S.J.; Cao, W.D. Effects of green manure on yield and nitrogen utilization of double rice under reduced 20% chemical fertilizer input in Jiangxi Province. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2022, 28, 845–856. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Dutta, G.; Goswami, T.; Kar, G. Enhancing root nodulation and boosting soil nitrogen mineralisation through strategic incorporation of sunnhemp as a green manure. Soil Res. 2025, 63, SR25015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.Y.; Xu, Q.; Chen, Y.P.; Liu, N.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.Q.; Cao, W.D.; Zhai, B.N.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, D.B.; et al. Le-guminous green manure enhances the soil organic nitrogen pool of cropland via disproportionate increase of nitrogen in par-ticulate organic matter fractions. Catena 2021, 207, 105574. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, T.T.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, H.N.; Dong, X.; Shen, Y.Y. Effects of green manure return on soil organic carbon component and carbon invertase enzyme activities. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2024, 57, 2791–2802. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.M.; Li, Y.S.; Nie, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, K.H.; Zhang, Y.K.; Zhang, Y.L.; She, H.Z.; Liu, X.B.; Ruan, R.W. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer and planting density on the leaf photosynthetic characteristics, agronomic traits and grain yield in common buck-wheat (Fagopyrum esculentum M.). Field Crops Res. 2018, 219, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Gou, Z.W.; Fan, Z.L.; Hu, F.L.; Yin, W. Compensation of green manure on photosynthetic source and yield loss of wheat caused by reduced irrigation in Hexi oasis irrigation area. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2022, 28, 1003–1014. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fei, L.W.; Pan, Y.H.; Ma, H.L.; Guo, R.J.; Wang, M.; Ling, N.; Shen, Q.R.; Guo, S.W. Optimal organic-inorganic fertilization increases rice yield through source-sink balance during grain filling. Field Crops Res. 2024, 308, 109285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, C.; Hu, X.T.; Wang, W.N.; Yan, H. Impact of nitrogen on photosynthesis, remobilization, yield, and efficiency in winter wheat under heat and drought stress. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 302, 109013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.M.; Hou, P.; Liu, G.Z.; Yang, Y.S.; Guo, X.X.; Ming, B.; Xie, R.Z.; Wang, K.R.; Liu, Y.E.; Li, S.K. Contribution of total dry matter and harvest index to maize grain yield-a multisource data analysis. Food Energy Secur. 2020, 9, e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Gao, S.; Li, L.L.; Xu, H.G.; Ming, B.; Wang, K.R.; Hou, P.; Xie, R.Z.; Li, S.K. Synergistic development of maize stalk as a strategy to reduce lodging risk. Agron. J. 2020, 112, 4962–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Yu, A.Z.; Wang, Y.L.; Su, X.X.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.F.; Lu, H.Q. Effect of combined green manure return and chemical ni-trogen fertilizer on dry matter accumulation and wheat yield in oasis irrigated area. Acta Agric. Boreali-Occident. Sin. 2024, 33, 787–797. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.H.; Gao, P.; Lei, W.S.; Gao, J.S.; Luo, Y.; Peng, F.X.; Mou, T.S.; Zhao, Z.W.; Zhang, K.; Guggenberger, G.; et al. Covering green manure increases rice yields via improving nitrogen cycling between soil and crops in paddy fields. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 383, 109517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.C.; Li, H.T.; Hu, F.L.; Yin, W.; Fan, Z.L.; Fan, H.; Sun, Y.L.; He, W.; Chai, Q. Application of green manure combined with synthetic nitrogen fertilizer enhances soil aggregate stability in an arid wheat cropping system. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 206, 105849. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, F.D.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zhao, P.Y.; Zhao, N.; Song, J.S.; Yu, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.Q.; Han, D.X.; Liu, X.D.; et al. Green manure roots return drives saline-alkali soil organic carbon accumulation via microbial necromass formation. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 251, 106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.D.; Zhou, G.P.; Gao, S.J. Effects and mechanisms of green manure on endogenous improving soil health. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2024, 30, 1274–1283. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Volume Weight (g·cm−3) | pH | Organic Carbon (g·kg−1) | Total Nitrogen (g·kg−1) | Rapid Available Phosphorus (g·kg−1) | Rapid Available Potassium (g·kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.40 | 8.4 | 10.9 | 0.89 | 28.7 | 155 |

| Code | Treatment | Application Amount During the Growth Period (Unit: Irrigation in mm; Fertilization in kg·ha−1) | Total Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | No irrigation reduction | Jointing stage: 90; Big trumpet stage: 75; Tasseling stage: 90; Silking period: 75; Filling period: 75 | 405 mm |

| I2 | Reduce irrigation by 20% | Jointing stage: 72; Big trumpet stage: 60; Tasseling stage: 72; Silking period: 60; Filling period: 60 | 324 mm |

| I3 | Reduce irrigation by 40% | Jointing stage: 54; Big trumpet stage: 45; Tasseling stage: 54; Silking period: 45; Filling period: 45 | 243 mm |

| N1 | No nitrogen reduction | Base fertilizer: 108; Flare opening staged: 180; Filling stage: 72 | 360 kg·ha−1 |

| N2 | Reduce Nitrogen by 20% | Base fertilizer: 87; Flare opening stage: 144; Filling stage: 58 | 288 kg·ha−1 |

| N3 | Reduce Nitrogen by 40% | Base fertilizer: 65; Flare opening stage: 108; Filling stage: 43 | 216 kg·ha−1 |

| Year | 2024 | 2025 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | WUE (kg·m−3) | NUtEg (kg·m−3) | WUE (kg·m−3) | NUtEg (kg·m−3) |

| I1N1 | 22.76 b | 33.32 bc | 23.76 b | 33.40 bc |

| I1N2 | 22.94 b | 35.75 ab | 23.60 b | 36.09 ab |

| I1N3 | 18.70 cd | 29.67 cd | 18.70 cd | 29.90 cd |

| I2N1 | 24.64 a | 33.99 ab | 24.98 a | 34.26 ab |

| I2N2 | 24.50 a | 37.87 a | 25.50 a | 37.21 a |

| I2N3 | 18.56 cd | 29.42 cd | 19.89 c | 29.91 cd |

| I3N1 | 20.53 bc | 27.06 d | 19.20 c | 27.51 d |

| I3N2 | 18.73 cd | 26.83 d | 18.40 d | 26.85 d |

| I3N3 | 16.58 d | 26.41 d | 16.92 d | 24.54 d |

| Significance | ||||

| Irrigation level (I) | ** | * | ** | ** |

| Nitrogen level (N) | * | ns | ** | ** |

| I × N | * | ns | * | * |

| Year | Treatment | Spike Number (×104 ha−1) | Kernel Number per Spike | Thousand-Kernel Weight (g) | GY (kg ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | I1N1 | 77 a | 727 a | 554 a | 15,889 a |

| I1N2 | 79 a | 717 a | 560 a | 15,988 a | |

| I1N3 | 69 b | 638 b | 478 b | 12,964 bc | |

| I2N1 | 76 a | 722 a | 556 a | 15,153 ab | |

| I2N2 | 76 a | 707 a | 563 a | 15,080 ab | |

| I2N3 | 66 b | 609 c | 466 bc | 11,380 cd | |

| I3N1 | 62 c | 584 cd | 450 cd | 10,865 cd | |

| I3N2 | 58 d | 569 d | 437 de | 9877 de | |

| I3N3 | 54 e | 538 e | 415 e | 8773 e | |

| 2025 | I1N1 | 79 a | 729 a | 556 a | 15,929 a |

| I1N2 | 80 a | 725 a | 561 a | 16,088 a | |

| I1N3 | 70 b | 641 b | 480 b | 13,131 b | |

| I2N1 | 78 a | 726 a | 558 a | 15,320 a | |

| I2N2 | 79 a | 727 a | 565 a | 15,279 a | |

| I2N3 | 67 b | 611c | 468 c | 11,413 bc | |

| I3N1 | 62 c | 586 cd | 452 cd | 10,932 c | |

| I3N2 | 60 cd | 571 d | 439 d | 9977 d | |

| I3N3 | 55 d | 540 e | 419 e | 9673 e | |

| Significance | |||||

| Irrigation level (I) | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| Nitrogen level (N) | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| I × N | * | ns | * | * | |

| Year | Treatment | Regression Equation | R2 | Maximum Increase Rate (kg·ha−1·d−1) | The Days of MIR (d) | Average Increase Rate (kg·ha−1·d−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | I1N1 | Y = 40284.8/(1 + 6.004e−0.066t) | 0.997 | 664.70 c | 90.97 abc | 261.52 a |

| I1N2 | Y = 40006.6/(1 + 6.228e−0.070t) | 0.997 | 700.12 ab | 88.97 cde | 262.42 a | |

| I1N3 | Y = 33083.0/(1 + 6.616e−0.074t) | 0.997 | 612.04 d | 89.41 cde | 219.20 b | |

| I2N1 | Y = 39667.5/(1 + 6.326e−0.070t) | 0.998 | 694.18 b | 90.37 bcd | 261.74 a | |

| I2N2 | Y = 39801.6/(1 + 6.448e−0.073t) | 0.996 | 726.38 a | 88.33 de | 262.13 a | |

| I2N3 | Y = 31824.8/(1 + 6.440e−0.071t) | 0.992 | 564.89 e | 90.70 a | 206.25 c | |

| I3N1 | Y = 30127.8/(1 + 6.688e−0.076t) | 0.997 | 572.43 e | 88.00 e | 201.19 d | |

| I3N2 | Y = 26664.4/(1 + 6.739e−0.075t) | 0.998 | 499.96 f | 89.85 de | 178.44 e | |

| I3N3 | Y = 40284.8/(1 + 7.117e−0.078t) | 0.996 | 470.16 g | 91.24 ab | 161.29 f | |

| 2025 | I1N1 | Y = 41711.9/(1 + 6.237e−0.069t) | 0.993 | 717.3 a | 90.7 ab | 270.4 a |

| I1N2 | Y = 40052.6/(1 + 6.229e−0.071t) | 0.997 | 697.5 a | 89.4 b | 262.8 b | |

| I1N3 | Y = 33109.6/(1 + 6.619e−0.074t) | 0.997 | 609.7 b | 89.8 b | 219.5 c | |

| I2N1 | Y = 39707.5/(1 + 6.329e−0.070t) | 0.998 | 698.1 a | 90.1 ab | 262.2 b | |

| I2N2 | Y = 43516.3/(1 + 6.037e−0.066t) | 0.996 | 706.4 a | 92.2 a | 278.4 a | |

| I2N3 | Y = 31910.8/(1 + 6.419e−0.070t) | 0.992 | 561.0 bc | 91.3 a | 206.5 c | |

| I3N1 | Y = 30181.1/(1 + 6.668e−0.076t) | 0.997 | 570.9 b | 88.1 c | 201.5 c | |

| I3N2 | Y = 26733.4/(1 + 6.720e−0.075t) | 0.998 | 503.4 cd | 89.2 b | 178.8 d | |

| I3N3 | Y = 24208.1/(1 + 7.097e−0.078t) | 0.996 | 473.9 d | 90.6 ab | 161.9 d | |

| Significance | ||||||

| Irrigation level (I) | / | / | ** | ** | ** | |

| Nitrogen level (N) | / | / | ** | ** | ** | |

| I × N | / | / | ** | * | ** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Yu, Y.; Pang, X.; Sun, Y.; Fan, Z.; Yin, W.; Hu, F.; He, W.; Nan, Y.; Yu, A. Green Manure Enables Reduced Water and Nitrogen Inputs with Sustained Yield in Maize. Agronomy 2026, 16, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010120

Wang F, Yu Y, Pang X, Sun Y, Fan Z, Yin W, Hu F, He W, Nan Y, Yu A. Green Manure Enables Reduced Water and Nitrogen Inputs with Sustained Yield in Maize. Agronomy. 2026; 16(1):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010120

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Feng, Yanzi Yu, Xiaoneng Pang, Yali Sun, Zhilong Fan, Wen Yin, Falong Hu, Wei He, Yunyou Nan, and Aizhong Yu. 2026. "Green Manure Enables Reduced Water and Nitrogen Inputs with Sustained Yield in Maize" Agronomy 16, no. 1: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010120

APA StyleWang, F., Yu, Y., Pang, X., Sun, Y., Fan, Z., Yin, W., Hu, F., He, W., Nan, Y., & Yu, A. (2026). Green Manure Enables Reduced Water and Nitrogen Inputs with Sustained Yield in Maize. Agronomy, 16(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16010120