Evaluation of Agronomic Parameters and Aboveground Biomass Production of Cannabis sativa Cultivated During Early and Late Planting Seasons in Bela-Bela, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

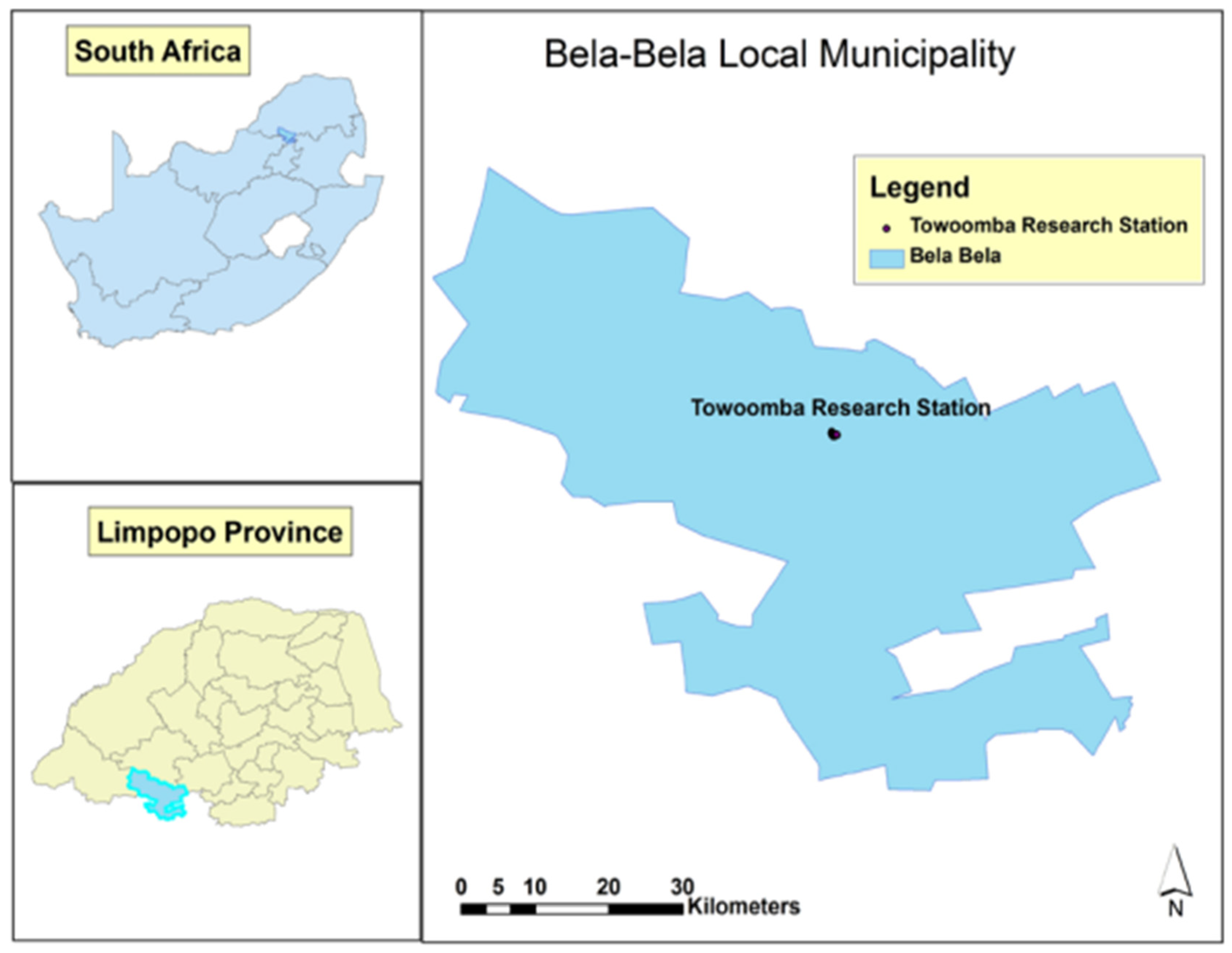

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Soil Sampling

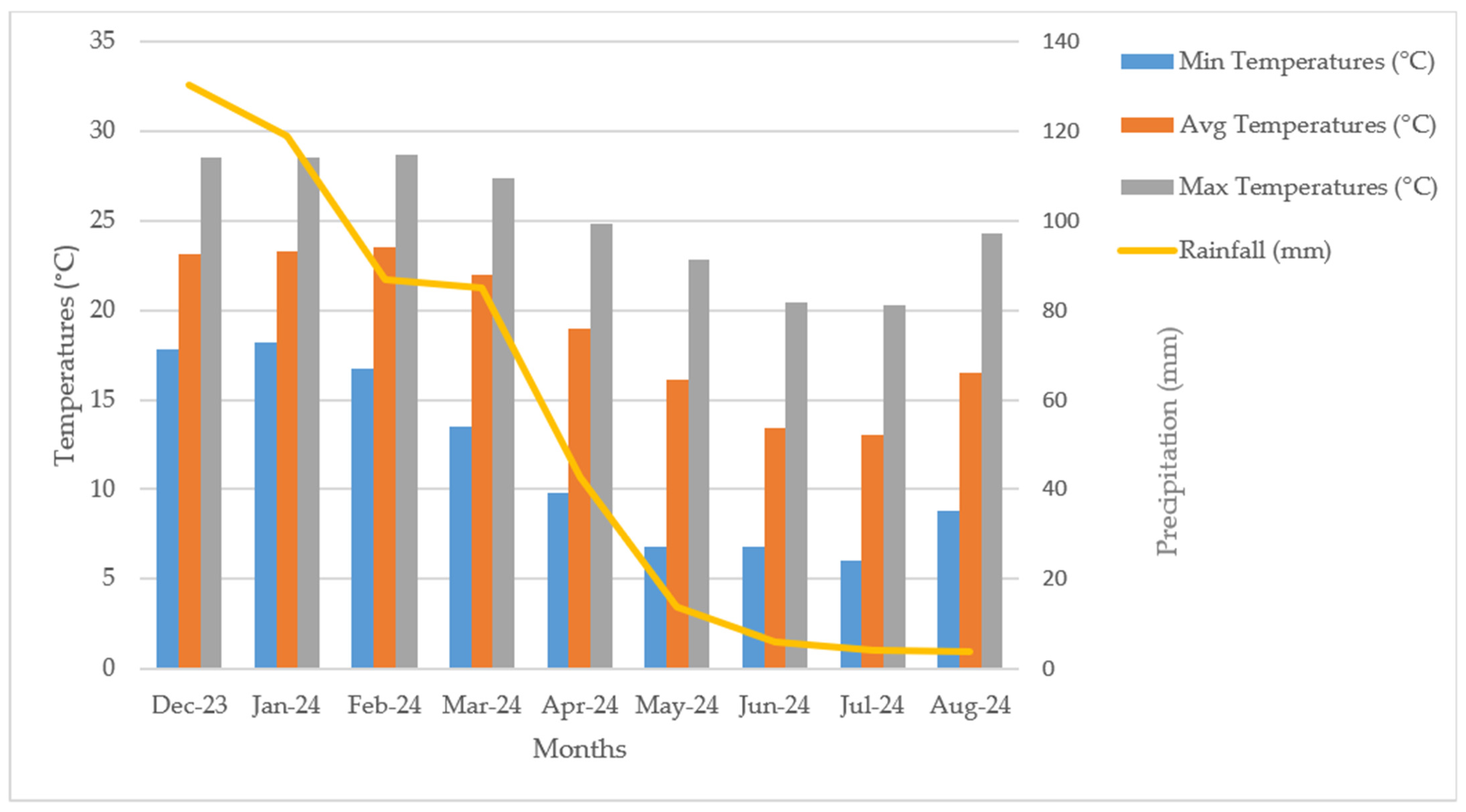

2.3. Weather Conditions During the Experimentation

2.4. Experimental Design and Layout

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Climatic Attributes at the Towoomba Research Station

3.2. Soil Composition Analysis

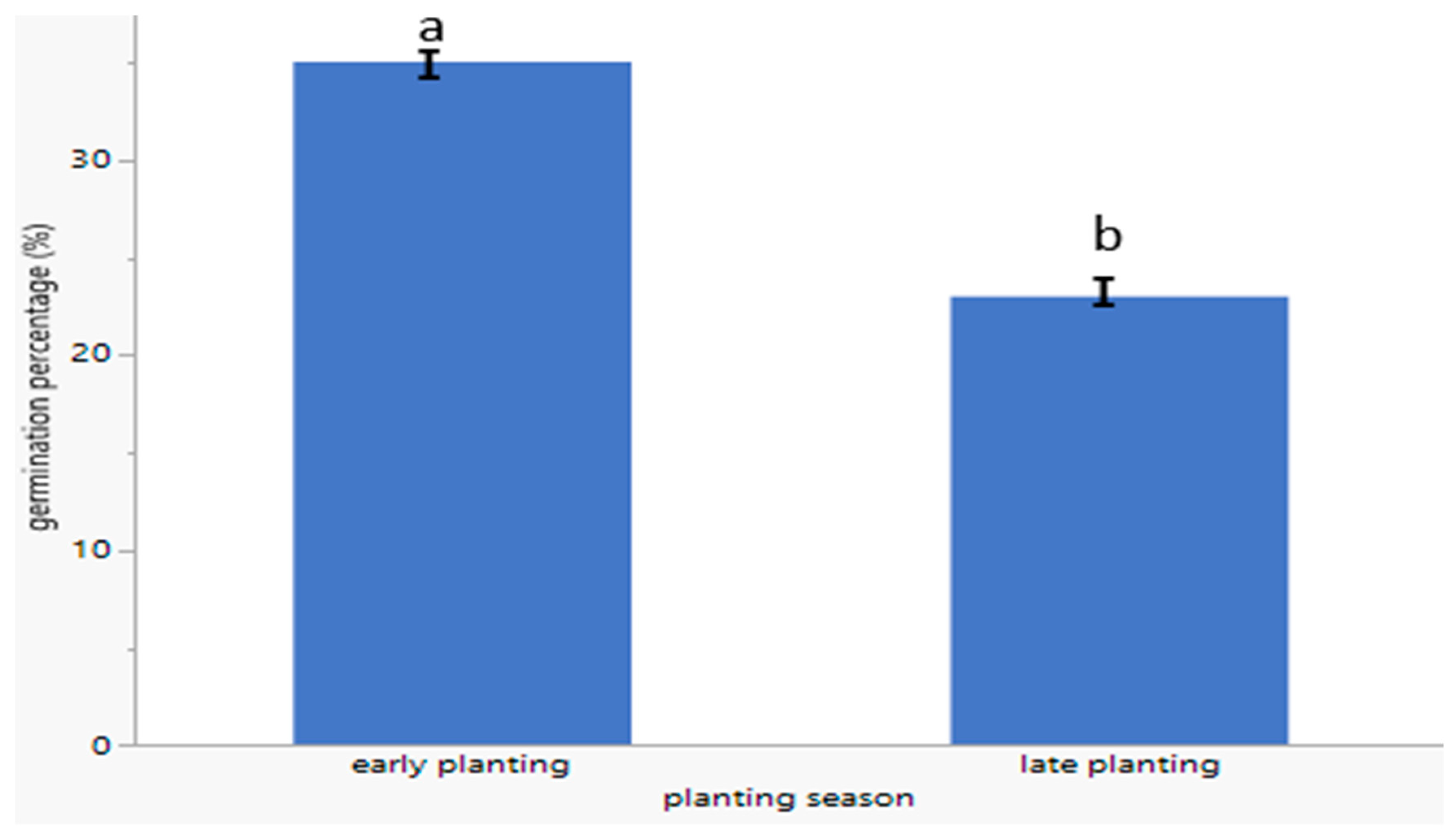

3.3. Germination Percentage of C. sativa During Early and Late Planting Seasons

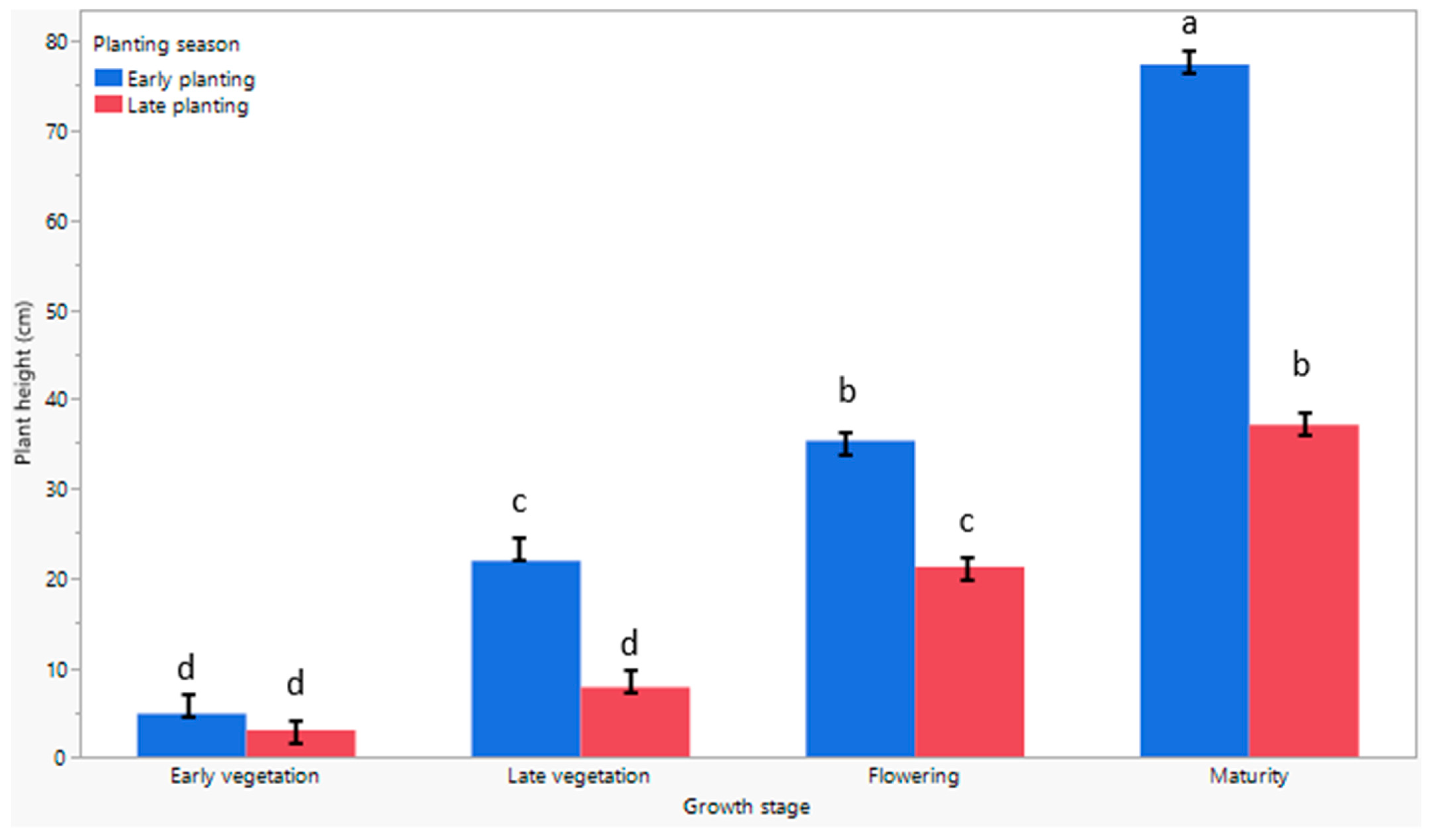

3.4. The Response of Plant Height to Early and Late Planting Seasons

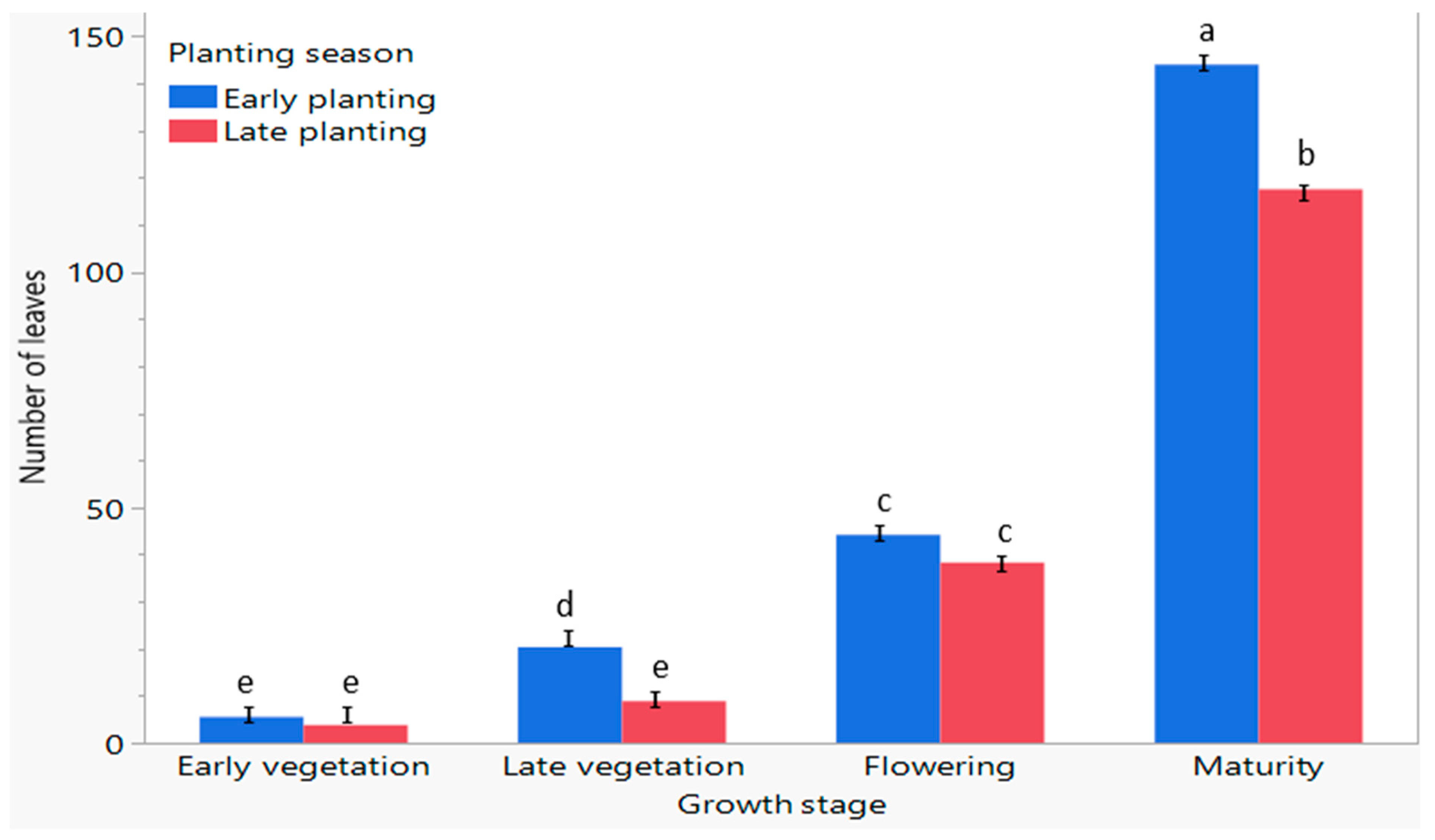

3.5. The Number of Leaves of C. sativa Responds to Early and Late Planting Seasons

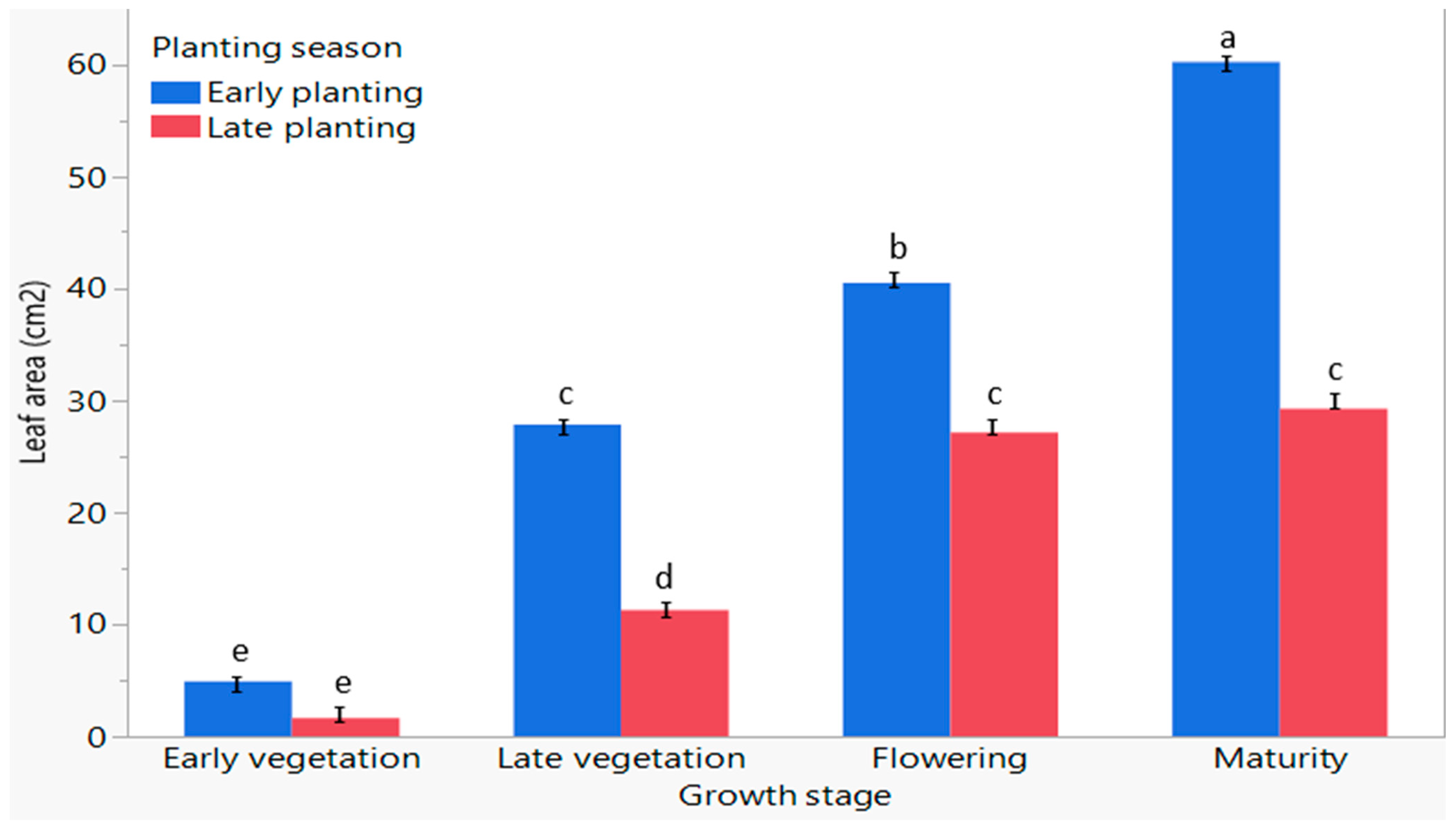

3.6. The Influence of Planting Season on the Leaf Area of C. sativa at Different Growth Stages

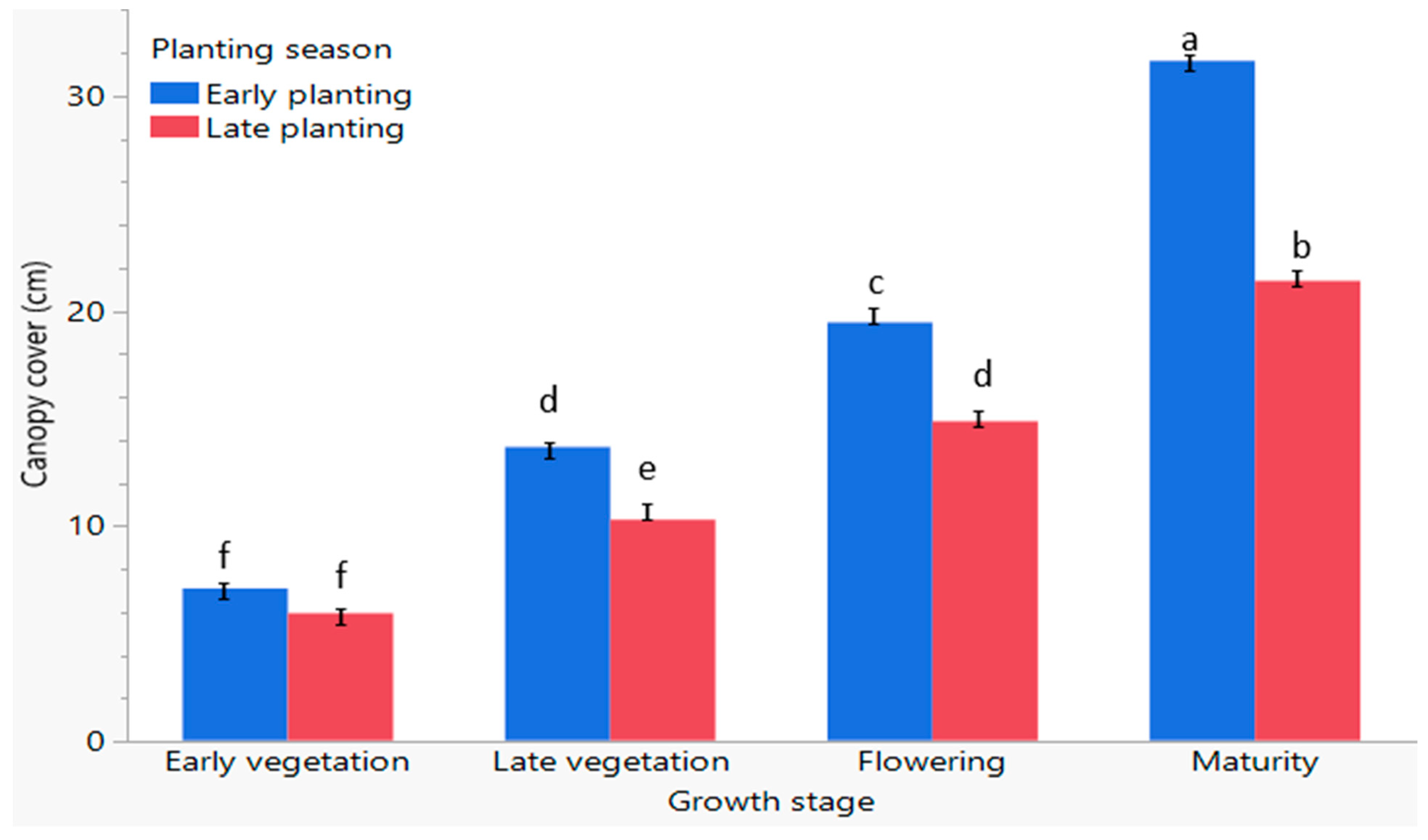

3.7. The Response of the Canopy Cover of the C. sativa Plant to Early and Late Planting Seasons at Different Growth Stages

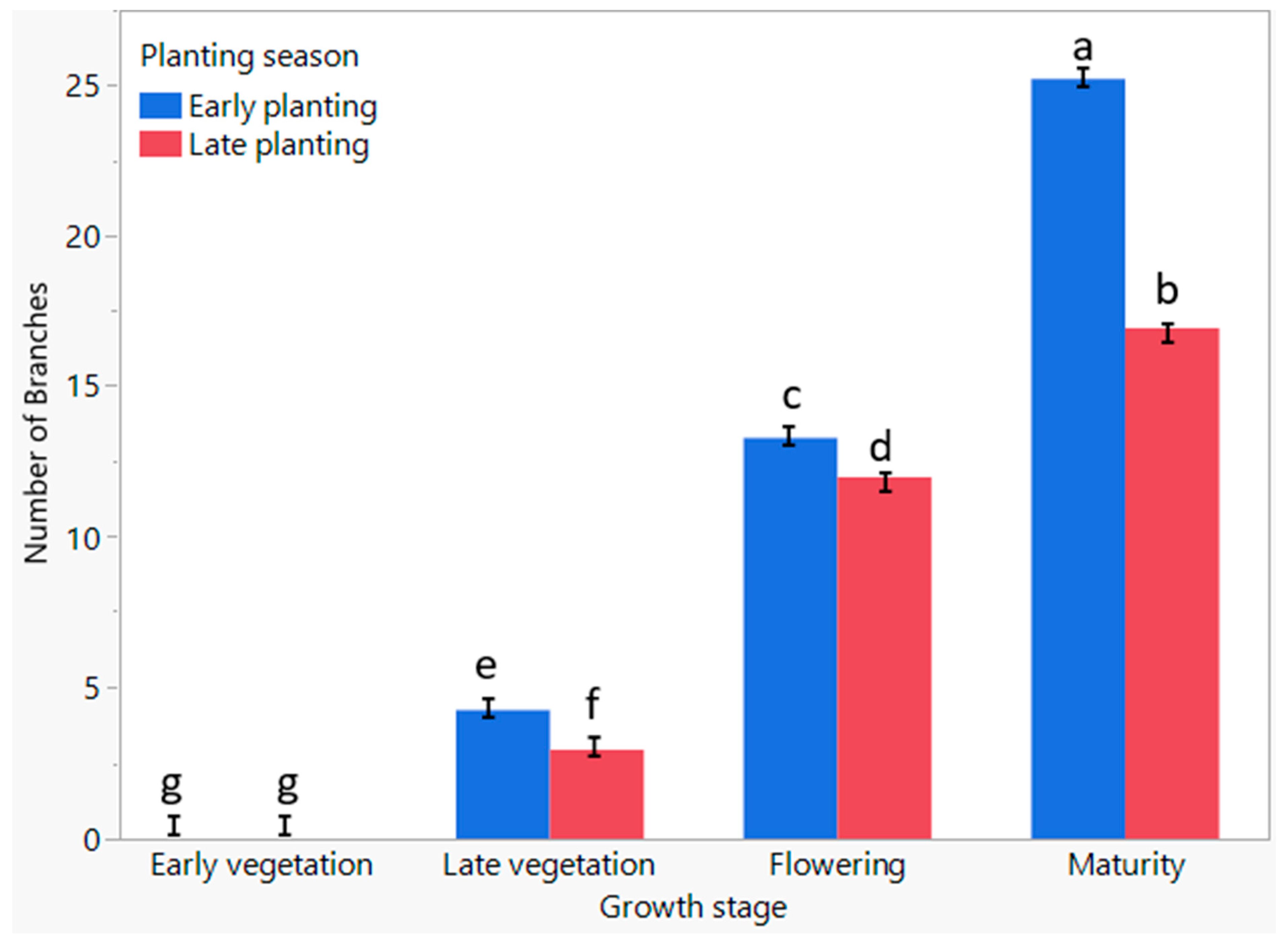

3.8. The Influence of Planting Season on the Number of Branches of C. sativa at Different Growth Stages

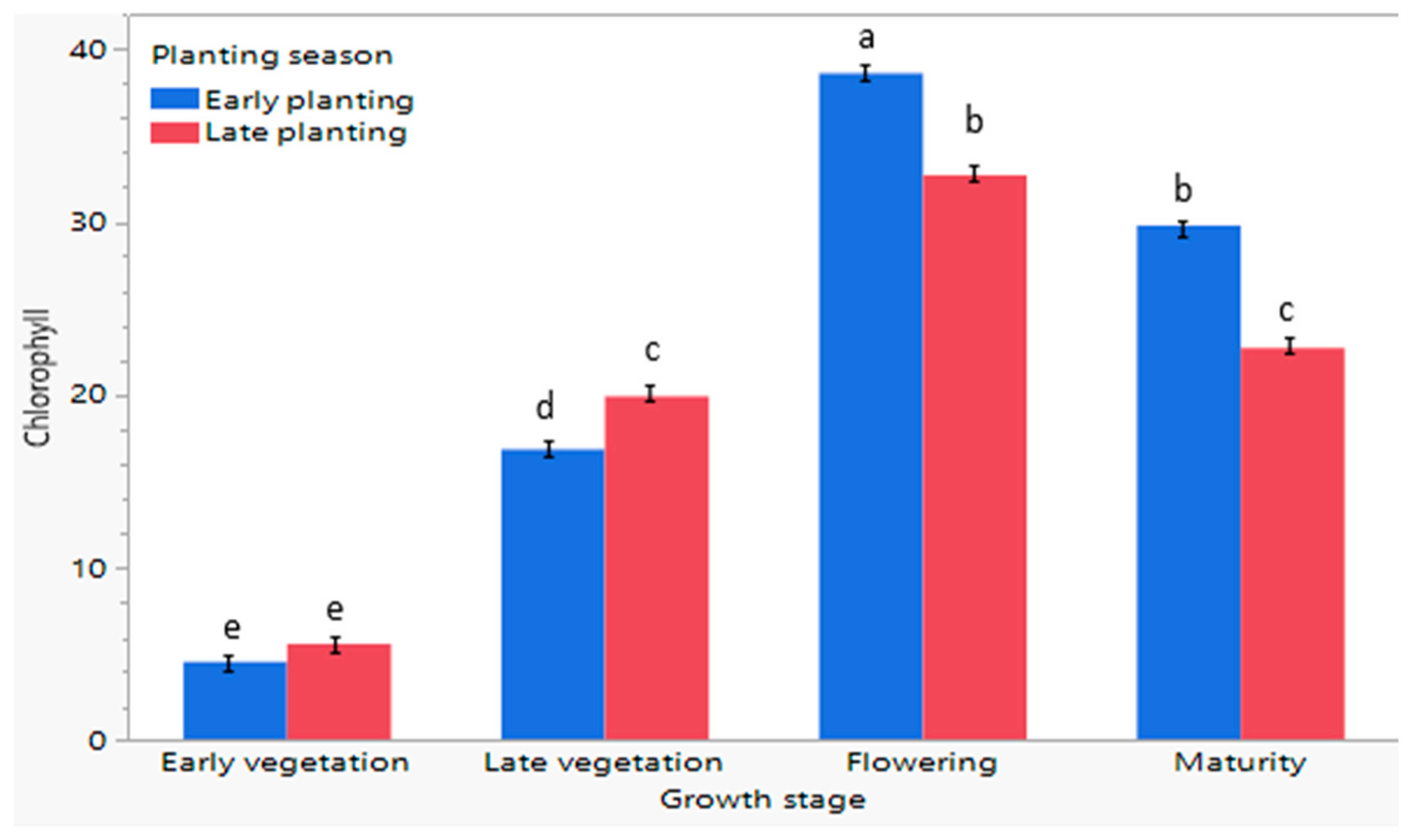

3.9. Assessment of the Influence of Planting Season on Chlorophyll Content of C. sativa at Different Growth Stages

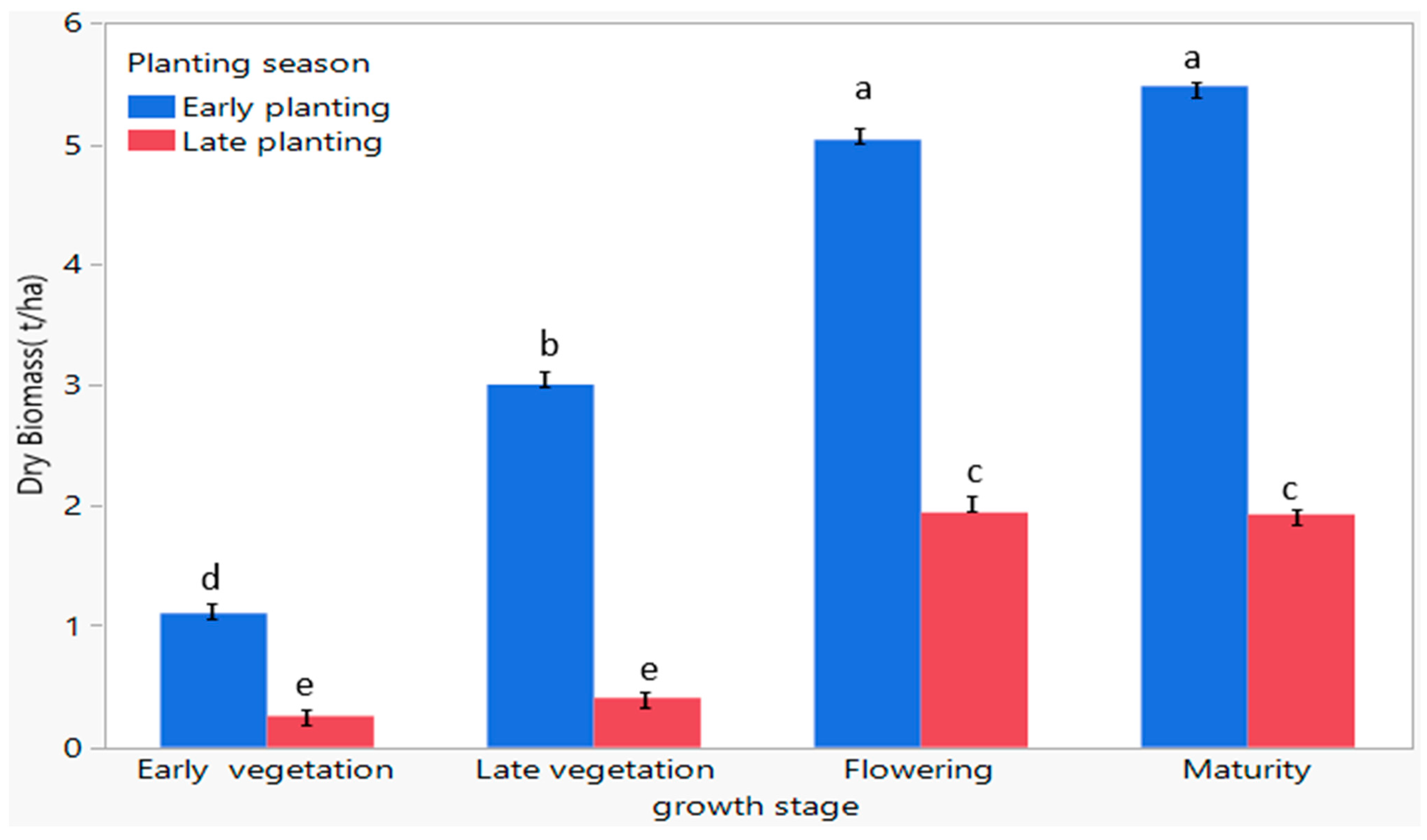

3.10. Evaluation of the Influence of Planting Season on Aboveground Biomass Production of C. sativa at Flowering and Maturity Growth Stages at Different Planting Dates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Visković, J.; Zheljazkov, V.D.; Sikora, V.; Noller, J.; Latković, D.; Ocamb, C.M.; Koren, A. Industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) agronomy and utilization: A review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćaćić, M.; Perčin, A.; Zgorelec, Ž.; Kisić, I. Evaluation of heavy metals accumulation potential of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2019, 20, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaducci, S.; Scordia, D.; Liu, F.H.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, H.; Testa, G.; Cosentino, S.L. Key cultivation techniques for hemp in Europe and China. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 68, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G.; Lichtfouse, E.; Chanet, G.; Morin-Crini, N. Traditional and new applications of hemp. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 42: Hemp Production and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 37–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgeman, M.B.; Abazia, D.T. Medicinal Cannabis: History, pharmacology, and implications for the acute care setting. Phar. Ther. 2017, 42, 180. [Google Scholar]

- Konvalina, P.; Neumann, J.; Hoang, T.N.; Bernas, J.; Trojan, V.; Kuchař, M.; Lošák, T.; Varga, L. Effect of Light Intensity and Two Different Nutrient Solutions on the Yield of Flowers and Cannabinoids in Cannabis sativa L. Grown in Controlled Environment. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, E.R.; Young, S.; Li, X.; Henriquez Inoa, S.; Suchoff, D.H. The effect of transplant date and plant spacing on biomass production for floral hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Agronomy 2023, 12, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, S.S.; Chiluwal, A.; Brym, Z.T.; Irey, M.; McCray, J.M.; Odero, D.C.; Daroub, S.H.; Sandhu, H.S. Evaluating growth, biomass, and cannabinoid profiles of floral hemp varieties under different planting dates in organic soils of Florida. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakabouki, I.; Kousta, A.; Folina, A.; Karydogianni, S.; Zisi, C.; Kouneli, V.; Papastylianou, P. Effect of fertilization with urea and inhibitors on growth, yield, and CBD concentration of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Sustainability 2021, 13, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Deng, G.; Yu, J.; Hu, W.; Guo, L.; Du, G.; Liu, F. Fiber hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) yield and its response to fertilization and planting density in China. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 177, 114542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F.; Kallinger, D.; Starzinger, A.; Lackner, M. Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Cultivation: Chemical Fertilizers or Organic Technologies, a Comprehensive Review. Nitrogen 2024, 5, 624–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandinières, H.; Amaducci, S. Agronomy and ecophysiology of hemp cultivation. In Cannabis/Hemp for Sustainable Agriculture and Materials; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- Monyela, S.; Kayoka, P.N.; Ngezimana, W.; Nemadodzi, L.E. Evaluating the metabolomic profile and anti-pathogenic properties of Cannabis species. Metabolites 2024, 14, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntsoane, T.; Nemukondeni, N.; Nemadodzi, L.E. A Systematic Review: Assessment of the Metabolomic Profile and Anti-Nutritional Factors of Cannabis sativa as a Feed Additive for Ruminants. Metabolites 2024, 14, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntalo, M.; Ravhuhali, K.E.; Moyo, B.; Mmbi, N.E.; Mokoboki, K.H. Physical and chemical properties of the soils in selected communal property associations of South Africa. PeerJ 2022, 10, 13960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soil Classification Working Group. Memoirs of the Natural Agricultural Resources of South Africa 15; Department of Agricultural Development: Pretoria, South Africa, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mpati, T.M. Satellite-Based Long-Term Evaluation of Bush Encroachment on Sourish-Mixed Veld at the Towoomba Research Station in Bela-Bela, Limpopo Province. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Limpopo, Limpopo, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mthimunye, L.M.; Managa, G.M.; Nemadodzi, L.E. The influence of Lablab Purpureus growth on nitrogen availability and mineral composition concentration in nutrient-poor savanna soils. Agronomy 2023, 13, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reeuwijk, L.P. Procedures for Soil Analysis, 6th ed.; Technical Paper 9; ISRIC: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2002; p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Prikner, P.; Lachnit, F.; Dvorak, F. A new soil core sampler for the determination of bulk density in soil profile. Plant Soil Environ. 2004, 50, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayment, G.E.; Higginson, F.R. Australian Laboratory Handbook of Soil and Water Chemical Methods; Inkata Press Pty Ltd.: Victoria, Australia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Microbial biomass. In Tropical Soil Biology and Fertility: A Handbook of Methods, 2nd ed.; Anderson, J.M., Ingram, J.S.I., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1993; pp. 68–70. ISBN 0-85198-821-0. [Google Scholar]

- Motshekga, L.M. Productivity and Physiological Responses of Winter Annual Forage Legumes to Planting Date and Short-Term Rotation with Forage Sorghum for Sheep Production Under a No-Till System in Limpopo Province. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Limpopo, Limpopo, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, C.E. Evaluating Hemp (Cannabis sativa) as a Forage Based on Yield, Nutritive Analysis, and Morphological Composition. Master’s Thesis, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA, 2018; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.J.; Ryu, B.R.; Azad, M.O.K.; Rahman, M.H.; Rana, M.S.; Kang, C.W.; Lim, J.D.; Lim, Y.S. Comparative growth, photosynthetic pigments, and osmolytes analysis of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seedlings under an aeroponics system with different LED light sources. Horticulture 2021, 7, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeff, K.; Williams, D.W. Hemp agronomy-grain and fiber production. In Industrial Hemp as a Modern Commodity Crop; American Society of Anesthesiologists: Schaumburg, IL, USA, 2019; pp. 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Khanal, S.; Khanal, S.; Koirala, S.; Katel, S.; Mandal, H.R. The effectiveness of seed priming in improving Okra germination and seedling growth. Asian J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2022, 18, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, A.; Florentine, S.K.; Chauhan, B.S.; Long, B.; Jayasundera, M. Influence of soil moisture regimes on growth, photosynthetic capacity, leaf biochemistry, and reproductive capabilities of the invasive agronomic weed, Lactuca serriola. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpanza, T.D.E. Biomass Yield and Nutritive Value of Stylosanthes scabra Accessions as a Forage Source for Goats; University of Pretoria: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, F.N.S.; de Assis, R.M.A.; Leite, J.J.F.; Miranda, T.F.; Alves, E.; Bertolucci, S.K.V.; Pinto, J.E.B.P. The cultivation of Lippia dulcis under ChromatiNet induces changes in vegetative growth, anatomy, and essential oil chemical composition. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 174, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Managa, G.M.; Nemadodzi, L.E. Comparison of Agronomic Parameters and Nutritional Composition on Red and Green Amaranth Species Grown in Open Field Versus Greenhouse Environment. Agriculture 2023, 13, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzo, C.O.G.; Kamali, B.; Hütt, C.; Bareth, G.; Gaiser, T. A Review of Estimation Methods for Aboveground Biomass in Grasslands Using UAV. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marabesi, A.O. Influence of Cadmium Exposure on Industrial Hemp Grown for Cannabinoid Production (Cannabis sativa L.). Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimirey, V.; Chaurasia, J.; Marahatta, S. Plant Nutrition Disorders: Insights from Clinic Analyses and Their Impact on Plant Health. Agric. Ext. Dev. Ctries. 2024, 2, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, I.M. Essential plant nutrients and their functions. Cent. Int. Agric. Trop. 2009, 209, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastav, P.; Prasad, M.; Singh, T.B.; Yadav, A.; Goyal, D.; Al, A.; Dantu, P.K. Role of nutrients in plant growth and development. In Contaminants in Agriculture: Sources, Impacts and Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, A.; Sharma, B.; Singh, B.N.; Hidangmayum, A.; Jatav, H.S.; Chandra, K.; Singhal, R.K.; Sathyanarayana, E.; Patra, A.; Mohapatra, K.K. Physiological mechanisms and adaptation strategies of plants under nutrient deficiency and toxicity conditions. In Plant Perspectives on Global Climate Change; Academic Press: London, UK, 2022; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Mokgolo, M.J.; Mzezewa, J. Baseline study of soil nutrient status in smallholder farms in Limpopo province of South Africa. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 2022, 50, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Biljon, J.J.; Fouche, D.S.; Botha, A.D.P. Threshold values and sufficiency levels for potassium in maize producing sandy soils of South Africa. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 2008, 25, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneve, R.L.; Janes, E.W.; Kester, S.T.; Hildebrand, D.F.; Davis, D. Temperature limits for seed germination in industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Crops 2022, 2, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basto, S.; Thompson, K.; Rees, M. The effect of soil pH on the persistence of seeds of grassland species in soil. Plant Ecol. 2015, 216, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhudev, S.H.; Ravindra, K.N.; Supreetha, B.H.; Nithyanandha, K.R.; Dharmappa, K.K.; Giresha, A.S. Effect of soil pH on plant growth, phytochemical contents, and their antioxidant activity. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. Res. 2023, 5, 718. [Google Scholar]

- Naim-Feil, E.; Pembleton, L.W.; Spooner, L.E.; Malthouse, A.L.; Miner, A.; Quinn, M.; Polotnianka, R.M.; Baillie, R.C.; Spangenberg, G.C.; Cogan, N.O. The characterization of key physiological traits of medicinal cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.) as a tool for precision breeding. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastylianou, P.; Kakabouki, I.; Travlos, I. Effect of nitrogen fertilization on growth and yield of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2018, 46, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenani, K.T.S. Aspects of the Water Use of Cannabis sativa L. Under Dryland Cultivation in the Eastern Cape. Ph.D. Dissertation, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi, M.; Sefidkon, F.; Peirovi, A.; Calagari, M.; Mousavi, A. Assessment of the cannabinoid content from different varieties of Cannabis sativa L. during the growth stages in three regions. Chem. Biodivers. 2021, 18, 2100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, N.; Runions, A.; Tsiantis, M. Leaf shape diversity: From genetic modules to computational models. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021, 72, 325–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balant, M.; Garnatje, T.; Vitales, D.; Hidalgo, O.; Chitwood, D.H. Intra-leaf modeling of Cannabis leaflet shape produces leaf models that predict genetic and developmental identities. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manggala, B.; Chaichana, C.; Kornievsky, M.; Fitriyah, N.S.; Wanison, R.; Syahputra, W.N.H. Chlorophyll content detection using a low-cost hyperspectral imaging in Cannabis sativa L. In Proceedings of the AIP Conference Proceedings, Rome, Italy, 28 December 2024; p. 3086. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsan, S.M.; Injamum-Ul-Hoque, M.; Shaffique, S.; Ayoobi, A.; Rahman, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Choi, H.W. Illuminating Cannabis sativa L.: The power of light in enhancing C. sativa growth and secondary metabolite production. Plants 2024, 13, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saastamoinen, M.; Eurola, M.; Hietaniemi, V. Oil, protein, chlorophyll, cadmium, and lead contents of seeds in oil and fiber flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) cultivars and in oil hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) cultivar Finola cultivated in the south-western part of Finland. J. Food Chem. Nanotechnol. 2016, 2, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziej, J.; Pudełko, K.; Mańkowski, J. Energy and biomass yield of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) as influenced by seeding rate and harvest time in Polish agro-climatic conditions. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 20, 2159609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Characteristics | Hutton Soils |

|---|---|

| Sample density g/mL | 1.25 |

| Nitrogen % | ˂0.05 |

| Phosphorous mg/L | 3 |

| Potassium mg/L | 221 |

| Calcium mg/L | 447 |

| Magnesium mg/L | 173 |

| Zinc mg/L | 1.2 |

| Manganese mg/L | 25 |

| Copper mg/L | 6 |

| Exchange Acidity cmol/L | 0.26 |

| Total Cations cmol/L | 4.48 |

| Acid saturation | 6 |

| pH (KCL) | 4.03 |

| Organic Carbon % | ˂0.05 |

| Clay % | 29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ntsoane, T.; Nemukondeni, N.; Nemadodzi, L.E. Evaluation of Agronomic Parameters and Aboveground Biomass Production of Cannabis sativa Cultivated During Early and Late Planting Seasons in Bela-Bela, South Africa. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122844

Ntsoane T, Nemukondeni N, Nemadodzi LE. Evaluation of Agronomic Parameters and Aboveground Biomass Production of Cannabis sativa Cultivated During Early and Late Planting Seasons in Bela-Bela, South Africa. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122844

Chicago/Turabian StyleNtsoane, Tumisho, Ndivho Nemukondeni, and Lufuno Ethel Nemadodzi. 2025. "Evaluation of Agronomic Parameters and Aboveground Biomass Production of Cannabis sativa Cultivated During Early and Late Planting Seasons in Bela-Bela, South Africa" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122844

APA StyleNtsoane, T., Nemukondeni, N., & Nemadodzi, L. E. (2025). Evaluation of Agronomic Parameters and Aboveground Biomass Production of Cannabis sativa Cultivated During Early and Late Planting Seasons in Bela-Bela, South Africa. Agronomy, 15(12), 2844. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122844