Salinity Properties Retrieval from Sentinel-2 Satellite Data and Machine Learning Algorithms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Experimental Setup

2.2. Ground-Based Field Measurements

2.2.1. Soil Electrical Conductivity

2.2.2. Leaf Electrical Conductivity

2.3. Satellite Remote Sensing Analysis

2.4. Assessment of the Appropriate Spectral Indices for Electrical Conductivity Property Estimation

2.5. Electrical Conductivity Variables’ Estimation Using Machine Learning Algorithms

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Soil and Leaf Samples Electrical Conductivity (EC) Values

3.2. Assessment of the Spectral Indices for Electrical Conductivity Property Estimation

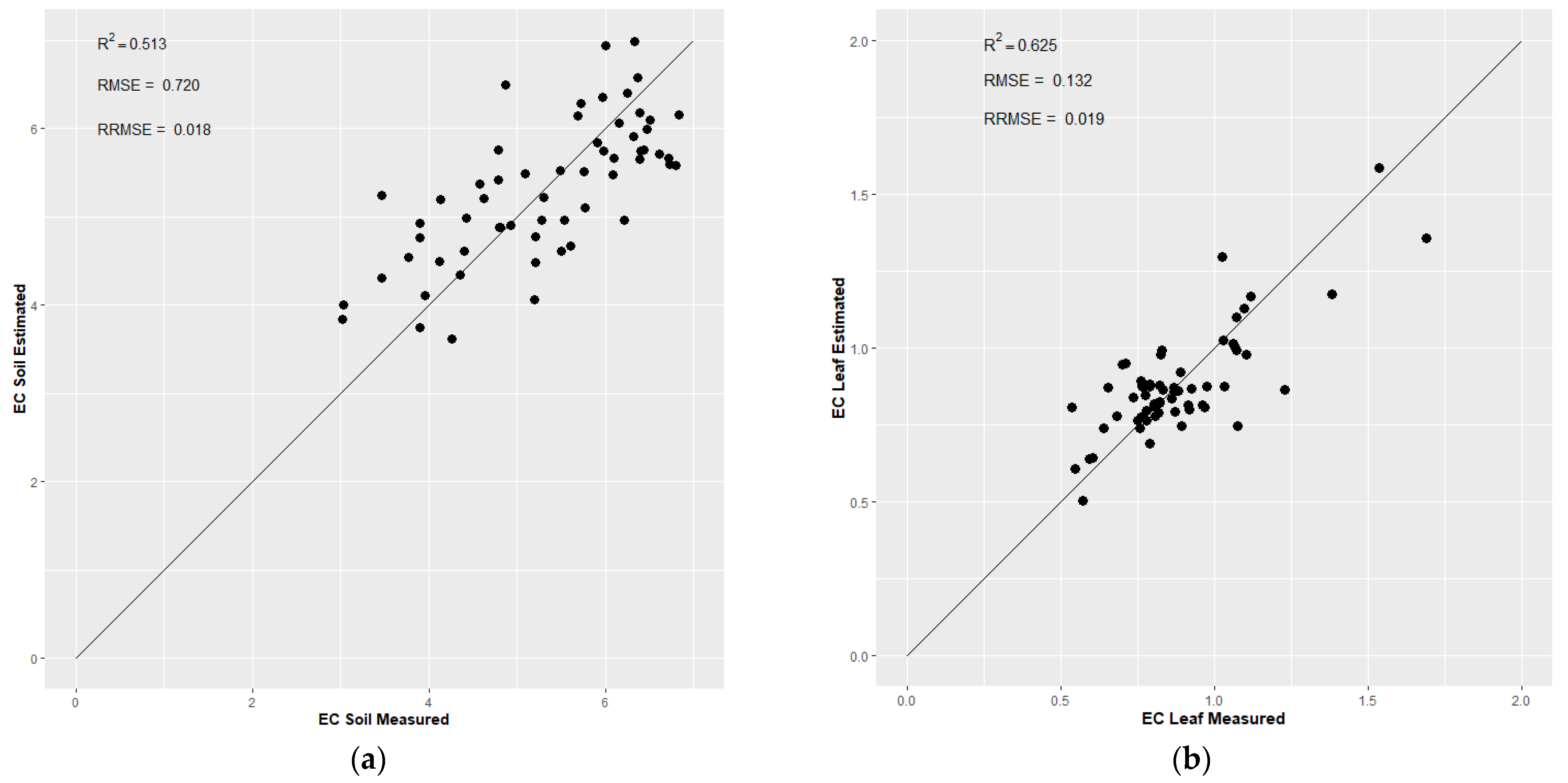

3.3. Electrical Conductivity Variables Estimation Using Machine Learning Algorithms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Litalien, A.; Zeeb, B. Curing the Earth: A Review of Anthropogenic Soil Salinization and Plant-Based Strategies for Sustainable Mitigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhao, G.; Li, T.; Zhou, X.; Li, J. Soil Salinization of Cultivated Land in Shandong Province, China—Dynamics during the Past 40 Years. Land Degrad Dev. 2019, 30, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Peng, J.; Li, H.; Yin, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, T.; Zhang, H. Soil Salinity Mapping Using Machine Learning Algorithms with the Sentinel-2 MSI in Arid Areas, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, B. Prediction of Soil Salinity with Soil-Reflected Spectra: A Comparison of Two Regression Methods. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, E.M.; Omara, A.E.D.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; El-Esawi, M.A. Minimizing Hazard Impacts of Soil Salinity and Water Stress on Wheat Plants by Soil Application of Vermicompost and Biochar. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, G.; Yao, X.; Jiang, H.; Cao, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, S.; He, C. Study on the Ecological Operation and Watershed Management of Urban Rivers in Northern China. Water 2020, 12, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yang, S.; Simayi, Z.; Gu, Q.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Ding, J. Modeling Variations in Soil Salinity in the Oasis of Junggar Basin, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, D.; van Niekerk, A. Machine Learning Performance for Predicting Soil Salinity Using Different Combinations of Geomorphometric Covariates. Geoderma 2017, 299, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Biswas, A.; Adamchuk, V.I. Implementation of a Sigmoid Depth Function to Describe Change of Soil PH with Depth. Geoderma 2017, 289, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshany, M.; Goldshleger, N.; Chudnovsky, A. Monitoring of Agricultural Soil Degradation by Remote-Sensing Methods: A Review. Int. J. Remote. Sens. 2013, 34, 6152–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Ji, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Fan, J.; Hou, X.; Yan, F.; Wang, H. Prediction of Soil Salinity Parameters Using Machine Learning Models in an Arid Region of Northwest China. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 204, 107512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Rahman, G.K.M.M.; Solaiman, A.R.M.; Alam, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Mia, M.A.B. Estimating Electrical Conductivity for Soil Salinity Monitoring Using Various Soil-Water Ratios Depending on Soil Texture. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2020, 51, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L.; Yemoto, K. Salinity: Electrical Conductivity and Total Dissolved Solids. Methods Soil Anal. 2017, 2, 1442–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L.; Lesch, S.M. Characterizing Soil Spatial Variability with Apparent Soil Electrical Conductivity: I. Survey Protocols. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2005, 46, 103–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabrillat, S.; Ben-Dor, E.; Cierniewski, J.; Gomez, C.; Schmid, T.; van Wesemael, B. Imaging Spectroscopy for Soil Mapping and Monitoring. Surv. Geophys. 2019, 40, 361–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K.J.; Chabrillat, S.; Brell, M.; Castaldi, F.; Spengler, D.; Foerster, S. Mapping Soil Organic Carbon for Airborne and Simulated Enmap Imagery Using the Lucas Soil Database and a Local Plsr. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, E.S.E. Rapid Prediction of Soil Mineralogy Using Imaging Spectroscopy. Eur. Soil Sci. 2017, 50, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Xu, C.; Huang, J.; Wu, J.; Tuller, M. Predicting Near-Surface Moisture Content of Saline Soils from Near-Infrared Reflectance Spectra with a Modified Gaussian Model. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2016, 80, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, C.; Oltra-Carrió, R.; Bacha, S.; Lagacherie, P.; Briottet, X. Evaluating the Sensitivity of Clay Content Prediction to Atmospheric Effects and Degradation of Image Spatial Resolution Using Hyperspectral VNIR/SWIR Imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 164, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Babaeian, E.; Tuller, M.; Jones, S.B. Particle Size Effects on Soil Reflectance Explained by an Analytical Radiative Transfer Model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 210, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, X.; Yan, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.; Ju, X.; Ding, N.; Dong, Y.; et al. Wavelength Selection for Estimating Soil Organic Matter Contents through the Radiative Transfer Model. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 176286–176293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidike, A.; Zhao, S.; Wen, Y. Estimating Soil Salinity in Pingluo County of China Using QuickBird Data and Soil Reflectance Spectra. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2014, 26, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawar, S.; Buddenbaum, H.; Hill, J. Estimation of Soil Salinity Using Three Quantitative Methods Based on Visible and Near-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy: A Case Study from Egypt. Arab. J. Geosci. 2015, 8, 5127–5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Yu, D. Monitoring and Evaluating Spatial Variability of Soil Salinity in Dry and Wet Seasons in the Werigan–Kuqa Oasis, China, Using Remote Sensing and Electromagnetic Induction Instruments. Geoderma 2014, 235–236, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chen, C.; Zheng, H.; Luo, G.; Yang, L.; Wang, W.; Wu, S.; Ding, J. AGA-SVR-Based Selection of Feature Subsets and Optimization of Parameter in Regional Soil Salinization Monitoring. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 4470–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, P.V.; Giang, N.V.; Binh, N.A.; Hai, L.V.H.; Pham, T.-D.; Hasanlou, M.; Bui, D.T. Soil Salinity Mapping Using SAR Sentinel-1 Data and Advanced Machine Learning Algorithms: A Case Study at Ben Tre Province of the Mekong River Delta (Vietnam). Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzid, N. Assessment of Remote-Based Vegetation Indices to Face Agriculture Challenges in The Mediterranean. 2021, 1–134. Available online: https://www.interregir2ma.eu/images/IR2MA/deliverables/242_Workshop/P6_IRM2A_Workshop_Mzid.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- DGACTA. Examen et Évaluation de La Situation Actuelle de La Salinisation Des Sols et Préparation d’un Plan d’action de Lutte Contre Ce Fléau Dans Les Périmètres Irrigués En Tunisie. In Phase 2: Ebauche Du Plan D’action; DGACTA, Ministère de L’agriculture et des Ressources Hydrauliques: Tunisie, Tunisie, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hachicha, M. Les Sols Salés et Leur Mise En Valeur En Tunisie. Sécher. Montroug. 2007, 18, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarai, B.; Walter, C.; Michot, D.; Montoroi, J.P.; Hachicha, M. Integrating Multiple Electromagnetic Data to Map Spatiotemporal Variability of Soil Salinity in Kairouan Region, Central Tunisia. J. Arid. Land 2022, 14, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimi, K.; Khader, N.; Adouni, L. Soil Salinity Assessment and Characterization in Abandoned Farmlands of Metouia Oasis, South Tunisia. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, M. An Excel-Based Tool for Real-Time Irrigation Management At Field Scale. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Water and Land Management for Sustainable Irrigated Agriculture, Dublin, Ireland, 31 January 1992; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D. Crop Evapotranspiration (Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements); FAO: Rome, Italy; Available online: https://appgeodb.nancy.inra.fr/biljou/pdf/Allen_FAO1998.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Ayers, R.S.; Westcot, D.W. Water Quality for Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1985. Available online: https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/water_issues/programs/tmdl/records/state_board/1985/ref2648.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Ismail, O.M. Use of Electrical Conductivity as a Tool for Determining Damage Index of Some Mango Cultivars. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2014, 3, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.M.; Rastoskuev, V.V.; Sato, Y.; Shiozawa, S. Assessment of Hydrosaline Land Degradation by Using a Simple Approach of Remote Sensing Indicators. Agric. Water Manag. 2005, 77, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.A.; Khan, S. Using Remote Sensing Techniques for Appraisal of Irrigated Soil Salinity. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Modelling and Simulation (MODSIM), Christchurch, New Zealand, December 2007; Modelling and Simulation Society of Australia and New Zealand: Brighton, UK, 2007; pp. 2632–2638. [Google Scholar]

- Daughtry, C.S.T.; Walthall, C.L.; Kim, M.S.; de Colstoun, E.B.; McMurtrey, J.E. Estimating Corn Leaf Chlorophyll Concentration from Leaf and Canopy Reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 2000, 74, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W., Jr.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W.; Rouse, J.W., Jr.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with Erts. NASSP 1974, 351, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Huete, A.R. A Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the Radiometric and Biophysical Performance of the MODIS Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleska, S.R.; Didan, K.; Huete, A.R.; da Rocha, H.R. Amazon Forests Green-up during 2005 Drought. Science 2007, 318, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. The Generalized Difference Vegetation Index (GDVI) for Dryland Characterization. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 1211–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qu, J.J. NMDI: A Normalized Multi-Band Drought Index for Monitoring Soil and Vegetation Moisture with Satellite Remote Sensing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fensholt, R.; Sandholt, I. Derivation of a Shortwave Infrared Water Stress Index from MODIS Near- and Shortwave Infrared Data in a Semiarid Environment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 87, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, P.; Flasse, S.; Tarantola, S.; Jacquemoud, S.; Grégoire, J.-M. Detecting Vegetation Leaf Water Content Using Reflectance in the Optical Domain. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 77, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, E.R.; Rock, B.N. Detection of Changes in Leaf Water Content Using Near- and Middle-Infrared Reflectances. Remote Sens. Environ. 1989, 30, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D.; Miller, J.R.; Tremblay, N.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Dextraze, L. Integrated Narrow-Band Vegetation Indices for Prediction of Crop Chlorophyll Content for Application to Precision Agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincini, M.; Frazzi, E.; D’Alessio, P. A Broad-Band Leaf Chlorophyll Vegetation Index at the Canopy Scale. Precis. Agric. 2008, 9, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Clemente, R.; Navarro-Cerrillo, R.M.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Deriving Predictive Relationships of Carotenoid Content at the Canopy Level in a Conifer Forest Using Hyperspectral Imagery and Model Simulation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 5206–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDB—Index: TCARI/OSAVI. Available online: https://www.indexdatabase.de/db/i-single.php?id=191 (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Kooistra, L.; van den Brande, M.M.M. Using Sentinel-2 Data for Retrieving LAI and Leaf and Canopy Chlorophyll Content of a Potato Crop. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenova, I.; Dimitrov, P. Evaluation of Sentinel-2 Vegetation Indices for Prediction of LAI, FAPAR and FCover of Winter Wheat in Bulgaria. Eur. J. Remote. Sens. 2020, 54, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Hornero, A.; Beck, P.S.A.; Kattenborn, T.; Kempeneers, P.; Hernández-Clemente, R. Chlorophyll Content Estimation in an Open-Canopy Conifer Forest with Sentinel-2A and Hyperspectral Imagery in the Context of Forest Decline. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 223, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Qiu, B.; Chen, C.; Zhu, X.; Wu, W.; Jiang, F.; Lin, D.; Peng, Y. Automated Soybean Mapping Based on Canopy Water Content and Chlorophyll Content Using Sentinel-2 Images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 109, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDB—Index: Modified Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index. Available online: https://www.indexdatabase.de/db/i-single.php?id=41 (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Maleki, M.; Arriga, N.; Barrios, J.M.; Wieneke, S.; Liu, Q.; Peñuelas, J.; Janssens, I.A.; Balzarolo, M. Estimation of Gross Primary Productivity (GPP) Phenology of a Short-Rotation Plantation Using Remotely Sensed Indices Derived from Sentinel-2 Images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, W.J.; Dash, J.; Watmough, G.; Milton, E.J. Evaluating the Capabilities of Sentinel-2 for Quantitative Estimation of Biophysical Variables in Vegetation. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2013, 82, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Binh, N.; Nguyen, B. Potential of Drought Monitoring Using Sentinel-2 Data; GIS-IDEAS. 2016. Available online: https://www.humg.edu.vn (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Wang, L.; Qu, J.J.; Hao, X. Forest Fire Detection Using the Normalized Multi-Band Drought Index (NMDI) with Satellite Measurements. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2008, 148, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Yue, H. Combined Sentinel-1A with Sentinel-2A to Estimate Soil Moisture in Farmland. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 1292–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, B. Comparison of Remote Sensing-Based Indexes for Monitoring Drought Impact on Forest Ecosystems. In Annual of Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski” Faculty of Geology and Geography Book 2; 2018; Volume 11, pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Han, J.; Liu, D. Estimating Salt Content of Vegetated Soil at Different Depths with Sentinel-2 Data. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L.H.; Heurich, M.; Beudert, B.; Premier, J.; Pflugmacher, D. Comparison of Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 Data for Estimation of Leaf Area Index in Temperate Forests. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni, Y.; Paillassa, E.; Chéret, V.; Monteil, C.; Sheeren, D. Sentinel-2 Poplar Index for Operational Mapping of Poplar Plantations over Large Areas. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonobe, R.; Yamaya, Y.; Tani, H.; Wang, X.; Kobayashi, N.; Mochizuki, K.-I. Crop Classification from Sentinel-2-Derived Vegetation Indices Using Ensemble Learning. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2018, 12, 026019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, N.; Tani, H.; Wang, X.; Sonobe, R. Crop Classification Using Spectral Indices Derived from Sentinel-2A Imagery. J. Inf. Telecommun. 2019, 4, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDB—Index: Normalized Difference 860/1640. Available online: https://www.indexdatabase.de/db/i-single.php?id=219 (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Elhag, M.; Bahrawi, J.A. Soil Salinity Mapping and Hydrological Drought Indices Assessment in Arid Environments Based on Remote Sensing Techniques. Geosci. Instrum. Methods Data Syst. 2017, 6, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDB—Index: Simple Ratio 1600/820 Moisture Stress Index. Available online: https://www.indexdatabase.de/db/i-single.php?id=48 (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Verrelst, J.; Romijn, E.; Kooistra, L. Mapping Vegetation Density in a Heterogeneous River Floodplain Ecosystem Using Pointable CHRIS/PROBA Data. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 2866–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.P.; Verrelst, J.; Delegido, J.; Veroustraete, F.; Moreno, J. On the Semi-Automatic Retrieval of Biophysical Parameters Based on Spectral Index Optimization. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 4927–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pablo, J.; Caicedo, R.; Verrelst, J.; Muñoz-Marí, J.; Moreno, J.; Camps-Valls, G. Toward a Semiautomatic Machine Learning Retrieval of Biophysical Parameters. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.P.; Verrelst, J.; Leonenko, G.; Moreno, J. Multiple Cost Functions and Regularization Options for Improved Retrieval of Leaf Chlorophyll Content and LAI through Inversion of the PROSAIL Model. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 3280–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metternicht, G.I.; Zinck, J.A. Remote Sensing of Soil Salinity: Potentials and Constraints. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 85, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allbed, A.; Kumar, L.; Aldakheel, Y.Y. Assessing Soil Salinity Using Soil Salinity and Vegetation Indices Derived from IKONOS High-Spatial Resolution Imageries: Applications in a Date Palm Dominated Region. Geoderma 2014, 230–231, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celleri, C.; Zapperi, G.; Trilla, G.G.; Pratolongo, P. Assessing the Capability of Broadband Indices Derived from Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager to Monitor above Ground Biomass and Salinity in Semiarid Saline Environments of the Bahía Blanca Estuary, Argentina. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 4817–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allbed, A.; Kumar, L. Soil Salinity Mapping and Monitoring in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions Using Remote Sensing Technology: A Review. Adv. Remote. Sens. 2013, 2, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakparvar, M.; Gabriels, D.; Aarabi, K.; Edraki, M.; Raes, D.; Cornelis, W. Incorporating Legacy Soil Data to Minimize Errors in Salinity Change Detection: A Case Study of Darab Plain, Iran. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2012, 33, 6215–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrelst, J.; Malenovský, Z.; van der Tol, C.; Camps-Valls, G.; Gastellu-Etchegorry, J.-P.; Lewis, P.; North, P.; Moreno, J. Quantifying Vegetation Biophysical Variables from Imaging Spectroscopy Data: A Review on Retrieval Methods. Surv. Geophys. 2019, 40, 589–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrelst, J.; Camps-Valls, G.; Muñoz-Marí, J.; Rivera, J.P.; Veroustraete, F.; Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Moreno, J. Optical Remote Sensing and the Retrieval of Terrestrial Vegetation Bio-Geophysical Properties—A Review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2015, 108, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatti, S.; Acito, N.; Amato, U.; Casa, R.; Castaldi, F.; Coluzzi, R.; de Bonis, R.; Diani, M.; Imbrenda, V.; Laneve, G.; et al. Environmental Products Overview of the Italian Hyperspectral Prisma Mission: The SAP4PRISMA Project. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Milan, Italy, 26–31 July 2015; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 3997–4000. [Google Scholar]

- Guanter, L.; Kaufmann, H.; Segl, K.; Foerster, S.; Rogass, C.; Chabrillat, S.; Kuester, T.; Hollstein, A.; Rossner, G.; Chlebek, C.; et al. The EnMAP Spaceborne Imaging Spectroscopy Mission for Earth Observation. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 8830–8857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrelst, J.; Muñoz, J.; Alonso, L.; Delegido, J.; Rivera, J.P.; Camps-Valls, G.; Moreno, J. Machine Learning Regression Algorithms for Biophysical Parameter Retrieval: Opportunities for Sentinel-2 and -3. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 118, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudby, A.; LeDrew, E.; Brenning, A. Predictive Mapping of Reef Fish Species Richness, Diversity and Biomass in Zanzibar Using IKONOS Imagery and Machine-Learning Techniques. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 1230–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiapaer, G.; Liang, S.; Yi, Q.; Liu, J. Vegetation Dynamics and Responses to Recent Climate Change in Xinjiang Using Leaf Area Index as an Indicator. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 58, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houborg, R.; McCabe, M.F. Daily Retrieval of NDVI and LAI at 3 m Resolution via the Fusion of CubeSat, Landsat, and MODIS Data. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, M.; Ebrahimi, A.; Naghipour, A.A.; Asadi, E.; Pérez-Suay, A.; Morata, M.; Garcia, J.L.; Caicedo, J.P.R.; Verrelst, J. Introducing ARTMO’s Machine-Learning Classification Algorithms Toolbox: Application to Plant-Type Detection in a Semi-Steppe Iranian Landscape. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, G.; Pezzola, A.; Winschel, C.; Casella, A.; Angonova, P.S.; Rivera-Caicedo, J.P.; Berger, K.; Verrelst, J.; Delegido, J. Seasonal Mapping of Irrigated Winter Wheat Traits in Argentina with a Hybrid Retrieval Workflow Using Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belda, S.; Pipia, L.; Morcillo-Pallarés, P.; Rivera-Caicedo, J.P.; Amin, E.; de Grave, C.; Verrelst, J. DATimeS: A Machine Learning Time Series GUI Toolbox for Gap-Filling and Vegetation Phenology Trends Detection. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 127, 104666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipia, L.; Muñoz-Marí, J.; Amin, E.; Belda, S.; Camps-Valls, G.; Verrelst, J. Fusing Optical and SAR Time Series for LAI Gap Filling with Multioutput Gaussian Processes. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 235, 111452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Sy, T.; To, Q.-D.; Vu, M.-N.; Nguyen, T.-D.; Nguyen, T.-T. Predicting the Electrical Conductivity of Brine-Saturated Rocks Using Machine Learning Methods. J. Appl. Geophys. 2021, 184, 104238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, L.; Shu, J. A Link Quality Prediction Method for Wireless Sensor Networks Based on Xgboost. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 155229–155241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wu, L.; Fan, J.; Zhang, F.; Zou, Y.; Wu, Y. A Novel Hybrid WOA-XGB Model for Estimating Daily Reference Evapotranspiration Using Local and External Meteorological Data: Applications in Arid and Humid Regions of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 244, 106594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, J.; Sangaiah, A.K.; Xie, Y.; Yin, X. Analysis and Prediction of Water Quality Using LSTM Deep Neural Networks in IoT Environment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, H.; Zhou, C.; Huang, Y.; Qi, X.; Shen, R.; Liu, F.; Zuo, M.; Zou, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Surface Water Quality Prediction Performance and Identification of Key Water Parameters Using Different Machine Learning Models Based on Big Data. Water Res. 2020, 171, 115454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, Z.M. An Insight into Machine Learning Models Era in Simulating Soil, Water Bodies and Adsorption Heavy Metals: Review, Challenges and Solutions. Chemosphere 2021, 277, 130126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, M.A.; Albalasmeh, A.A.; Pratt, C.; el Hanandeh, A. Estimation of Exchangeable Sodium Percentage from Sodium Adsorption Ratio of Salt-Affected Soils Using Traditional and Dilution Extracts, Saturation Percentage, Electrical Conductivity, and Generalized Regression Neural Networks. Catena 2021, 205, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el Bilali, A.; Taleb, A.; Brouziyne, Y. Groundwater Quality Forecasting Using Machine Learning Algorithms for Irrigation Purposes. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 245, 106625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, W.-Y. Classification and Regression Trees. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2011, 1, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisi, O.; Dailr, A.H.; Cimen, M.; Shiri, J. Suspended Sediment Modeling Using Genetic Programming and Soft Computing Techniques. J. Hydrol. 2012, 450–451, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubin, B.; Darabi, H.; Rahmati, O.; Sajedi-Hosseini, F.; Kløve, B. River Suspended Sediment Modelling Using the CART Model: A Comparative Study of Machine Learning Techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melesse, A.M.; Khosravi, K.; Tiefenbacher, J.P.; Heddam, S.; Kim, S.; Mosavi, A.; Pham, B.T. River Water Salinity Prediction Using Hybrid Machine Learning Models. Water 2020, 12, 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, K.A.; Emslie, M.J.; Hoey, A.S.; Osborne, K.; Jonker, M.J.; Cheal, A.J. Macroalgal Feedbacks and Substrate Properties Maintain a Coral Reef Regime Shift. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zucca, C.; Muhaimeed, A.S.; Al-Shafie, W.M.; Al-Quraishi, A.M.F.; Nangia, V.; Zhu, M.; Liu, G. Soil Salinity Prediction and Mapping by Machine Learning Regression in Central Mesopotamia, Iraq. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 4005–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.A.; Aalami, M.T.; Naghipour, L. Use of Artificial Neural Networks for Electrical Conductivity Modeling in Asi River. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khozani, Z.S.; Khosravi, K.; Pham, B.T.; Kløve, B.; Mohtar, W.H.M.W.; Yaseen, Z.M. Determination of Compound Channel Apparent Shear Stress: Application of Novel Data Mining Models. J. Hydroinfor. 2019, 21, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, B.T.; Prakash, I.; Khosravi, K.; Chapi, K.; Trinh, P.T.; Ngo, T.Q.; Hosseini, S.V.; Bui, D.T. A Comparison of Support Vector Machines and Bayesian Algorithms for Landslide Susceptibility Modelling. Geocarto Int. 2018, 34, 1385–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, K.; Mao, L.; Kisi, O.; Yaseen, Z.M.; Shahid, S. Quantifying Hourly Suspended Sediment Load Using Data Mining Models: Case Study of a Glacierized Andean Catchment in Chile. J. Hydrol. 2018, 567, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dates | 8 April 2017 | 6 May 2017 | 21 May 2017 | 2 June 2017 | 23 July 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Julian days | 98 | 126 | 141 | 153 | 174 |

| Stage | Cluster formation | Full bloom | Fruit set | Fruit growth (stage 1) | Fruit growth (stage 2) |

| Symbol | C | F1 | H | I | I1 |

| Dates | 11 April 2018 | 25 April 2018 | 24 May 2018 | 25 June 2018 | 31 July 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Julian days | 101 | 115 | 136 | 144 | 176 | 212 |

| Stage | Cluster formation | Full bloom | Fruit set | Fruit growth (stage 1) | Fruit growth (stage 2) | |

| Symbol | C | F1 | H | I | I1 | |

| Sentinel-2 Selected Dates | |

|---|---|

| Growing Season 2016–2017 | Growing Season 2017–2018 |

| 01 April 2017 | 11 April 2018 |

| 11 April 2017 | 06 May 2018 |

| 31 May 2017 | 26 May 2018 |

| 10 June 2017 | 30 June 2018 |

| 25 July 2017 | 30 July 2018 |

| Index | Formula | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salinity spectral indices | ||||

| NDSI | Normalized Differential Salinity Index | [36] | ||

| S1 | Salinity Index 1 | [37] | ||

| SI | Salinity Index | [38] | ||

| Vegetation spectral indices | ||||

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | [39] | ||

| SAVI | Soil- Adjusted Vegetation Index | [40] | ||

| EVI | Enhanced Vegetation Index | [41,42] | ||

| GDVI | Generalized Difference Vegetation Index | = n: Power, an integer of the values of 1, 2, 3, 4…n. GDVI ranges from −1 to 1. SR: simple ratio = | [43] | |

| Water spectral indices | ||||

| NMDI | Normalized Multiband Drought Index | [44] | ||

| SIWSI | Shortwave Infrared Water Stress Index | [45] | ||

| MSI | Moisture Stress Index | [46,47] | ||

| Chlorophyll spectral indices | ||||

| TCARI/OSAVI | Transformed Chlorophyll Absorption Reflectance Index/ Optimized Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index | [48] | ||

| CVI | Chlorophyll vegetation index | [49] | ||

| MCARI | Modified Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index | [38] | ||

| Variable | Min | Max | Mean | Median | SD | CV (%) | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECSoil | 2.729 | 6.830 | 4.939 | 4.800 | 1.077 | 21.805 | 0.012 |

| ECLeaf | 0.536 | 1.690 | 0.898 | 0.859 | 0.210 | 23.395 | 1.159 |

| Spectral Indices | ECSoil | ECLeaf | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE | p | R2 | RMSE | p | ||

| Salinity indices | NDSI | 0.157 | 5.30 | *** | 0.154 | 1.17 | *** |

| S1 | 0.702 | 4.07 | *** | 0.052 | 0.28 | * | |

| SI | 0.573 | 4.84 | *** | 0.263 | 0.72 | *** | |

| Chlorophyll indices | TCARI/OSAVI | 0.314 | 4.17 | *** | 0.147 | 0.21 | *** |

| MCARI | 0.357 | 4.11 | *** | 0.187 | 0.28 | *** | |

| CVI | 0.415 | 4.34 | *** | 0.030 | 0.29 | n.s. | |

| Vegetation indices | NDVI | 0.001 | 4.76 | n.s. | 0.308 | 0.70 | *** |

| SAVI | 0.003 | 4.65 | n.s. | 0.341 | 0.59 | *** | |

| EVI | 0.004 | 4.20 | n.s. | 0.309 | 0.44 | *** | |

| GDVI | 0.310 | 5.19 | *** | 0.460 | 0.70 | *** | |

| Water indices | NMDI | 0.002 | 4.45 | n.s. | 0.355 | 0.41 | *** |

| SIWSI | 0.076 | 4.66 | * | 0.014 | 0.48 | n.s. | |

| MSI | 0.180 | 4.27 | *** | 0.450 | 0.32 | *** | |

| MLRA | MAE | RMSE | R | R2 | NSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sparse Spectrum Gaussian Process Regression | 0.601 | 0.720 | 0.716 | 0.513 | 0.510 |

| Warped Gaussian Process Regression | 0.620 | 0.762 | 0.716 | 0.4524 | 0.452 |

| Canonical Correlation Forests | 0.634 | 0.764 | 0.673 | 0.4834 | 0.449 |

| Random forest (Tree Bagger) | 0.614 | 0.766 | 0.695 | 0.4496 | 0.447 |

| Bagging trees | 0.622 | 0.769 | 0.671 | 0.4523 | 0.442 |

| Gaussian Process Regression | 0.651 | 0.794 | 0.673 | 0.4096 | 0.406 |

| Boosting trees | 0.616 | 0.796 | 0.640 | 0.4673 | 0.402 |

| VH Gaussian Process Regression | 0.664 | 0.796 | 0.684 | 0.4059 | 0.401 |

| Regression tree | 0.616 | 0.803 | 0.634 | 0.4578 | 0.392 |

| Gradient Boosting/Boosted Trees | 0.673 | 0.810 | 0.677 | 0.3981 | 0.381 |

| Regression tree (LS boosting) | 0.637 | 0.855 | 0.631 | 0.4228 | 0.310 |

| Kernel signal-to-noise ratio | 0.707 | 0.866 | 0.650 | 0.2995 | 0.293 |

| Relevance vector machine | 0.700 | 0.878 | 0.547 | 0.2766 | 0.273 |

| Weighted k-nearest neighbor regression | 0.712 | 0.879 | 0.526 | 0.2741 | 0.271 |

| Kernel ridge Regression | 0.754 | 0.894 | 0.524 | 0.3027 | 0.245 |

| Elastic Net regression | 0.770 | 0.944 | 0.550 | 0.1606 | 0.158 |

| K-nearest neighbor regression | 0.777 | 0.974 | 0.401 | 0.1381 | 0.105 |

| Regularized least-squares regression | 0.825 | 0.985 | 0.372 | 0.0966 | 0.084 |

| Extreme Learning Machine | 0.792 | 1.148 | 0.311 | 0.1768 | - |

| Least-squares linear regression | - | - | - | - | - |

| Partial least-squares regression | - | - | - | - | - |

| Principal component regression | - | - | - | - | - |

| Adaptive Regression Splines | - | - | - | - | - |

| Support vector regression | - | - | - | - | - |

| Twin Gaussian process | - | - | - | - | - |

| MLRA | MAE | RMSE | R | R2 | NSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Regression | 0.097 | 0.132 | 0.790 | 0.625 | 0.624 |

| Kernel ridge Regression | 0.098 | 0.134 | 0.797 | 0.636 | 0.613 |

| Canonical Correlation Forests | 0.101 | 0.134 | 0.813 | 0.661 | 0.597 |

| Relevance vector machine | 0.106 | 0.140 | 0.761 | 0.579 | 0.577 |

| VH Gaussian Process Regression | 0.098 | 0.140 | 0.761 | 0.579 | 0.576 |

| Kernel signal-to-noise ratio | 0.104 | 0.146 | 0.740 | 0.547 | 0.541 |

| Sparse Spectrum Gaussian Process Regression | 0.107 | 0.151 | 0.725 | 0.526 | 0.508 |

| Weighted k-nearest neighbor regression | 0.116 | 0.164 | 0.662 | 0.439 | 0.415 |

| Extreme Learning Machine | 0.128 | 0.172 | 0.627 | 0.393 | 0.362 |

| Adaptive Regression Splines | 0.127 | 0.172 | 0.678 | 0.460 | 0.360 |

| Bagging trees | 0.121 | 0.176 | 0.649 | 0.421 | 0.331 |

| Boosting trees | 0.132 | 0.177 | 0.601 | 0.361 | 0.322 |

| Random forest (Tree Bagger) | 0.119 | 0.177 | 0.574 | 0.330 | 0.319 |

| Gradient Boosting/Boosted Trees | 0.127 | 0.183 | 0.572 | 0.327 | 0.278 |

| K-nearest neighbor regression | 0.130 | 0.184 | 0.568 | 0.323 | 0.264 |

| Elastic Net regression | 0.139 | 0.185 | 0.530 | 0.281 | 0.258 |

| Regularized least-squares regression | 0.141 | 0.186 | 0.522 | 0.272 | 0.253 |

| Regression tree | 0.165 | 0.267 | 0.090 | 0.008 | - |

| Warped Gaussian Process Regression | 0.151 | 0.275 | 0.035 | 0.001 | - |

| Regression tree (LS boosting) | 0.182 | 0.281 | 0.108 | 0.012 | - |

| Principal component regression | - | - | - | - | - |

| Least-squares linear regression | - | - | - | - | - |

| Partial least-squares regression | - | - | - | - | - |

| Support Vector Regression | - | - | - | - | - |

| Twin Gaussian process | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mzid, N.; Boussadia, O.; Albrizio, R.; Stellacci, A.M.; Braham, M.; Todorovic, M. Salinity Properties Retrieval from Sentinel-2 Satellite Data and Machine Learning Algorithms. Agronomy 2023, 13, 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030716

Mzid N, Boussadia O, Albrizio R, Stellacci AM, Braham M, Todorovic M. Salinity Properties Retrieval from Sentinel-2 Satellite Data and Machine Learning Algorithms. Agronomy. 2023; 13(3):716. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030716

Chicago/Turabian StyleMzid, Nada, Olfa Boussadia, Rossella Albrizio, Anna Maria Stellacci, Mohamed Braham, and Mladen Todorovic. 2023. "Salinity Properties Retrieval from Sentinel-2 Satellite Data and Machine Learning Algorithms" Agronomy 13, no. 3: 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030716

APA StyleMzid, N., Boussadia, O., Albrizio, R., Stellacci, A. M., Braham, M., & Todorovic, M. (2023). Salinity Properties Retrieval from Sentinel-2 Satellite Data and Machine Learning Algorithms. Agronomy, 13(3), 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030716