Evaluation of the Sustainability of Vineyards in Semi-Arid Climates: The Case of Southeastern Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Characterization of the Zone

2.3. Establishment of Vineyard Production Systems

2.3.1. Rainfed Vineyards

2.3.2. Irrigated Vineyards

2.4. Economic Analysis

2.4.1. Productive Structure of Costs and Income

- Rainfed vineyards. In the rainfed vineyard scenarios (CR and OR), the investments coincide, since the farms are identical in terms of the surface area, planting scheme, and plant material. The investments are a warehouse for tools, preparation and planting of the land (uprooting of the previous vines and their collection, clearing the land of stones, refining and leveling, planting of the rootstocks, and grafting), and the auxiliary material (shovels, hoes, scissors, etc.).

- Irrigated vineyards. Scenarios CI and OI have the same general characteristics, so the investments coincide: a warehouse for tools, a header, preparation and planting of the land (uprooting with a moldboard plough of the previous vines and their collection, clearing the land of stones, refining and levelling, planting of the already grafted vines, and the trellis, including its installation cost), auxiliary material (shovels, hoes, scissors, etc.), irrigation head, irrigation network, and regulating reservoir.

- Production insurance. To establish the cost of the insurance, the report “Average cost of insurance in the Autonomous Community of Murcia”, published by Agroseguro, was used [37]. In vine cultivation, the insurance depends on the selection of cover for hail or for hail and other adversities. For this work, the most common coverage, hail (0.024 € kg−1), was chosen, with the cost of the insurance being a premium based on the average production [37].

- Pruning. This refers to the cost of the labor associated with the pruning, carried out manually. In all scenarios, annual winter pruning is carried out, and in irrigated areas green pruning is also carried out to eliminate excess biomass. The prunings are crushed between the rows of vines and incorporated into the soil, due to the agronomic and economic advantages [38].

- Machinery. It was considered that the farms contract external services. Therefore, the cost of machinery was accounted for based on the unit market cost. Each job includes tractors, implements, and labor. The machinery involved in the harvest was accounted for as a harvesting cost.

- Fertilizers. The fertilizer units used to calculate the amounts of fertilizer required were 20-12-35 (N-P2O5-K2O) for rainfed land and 42-23-73 (N-P2O5-K2O) for irrigated land (Table 1). These values were quantified based on the optimum balance for vineyards derived from fertilization programs recommended by [39], as well as a specific bibliography on Monastrell grape cultivation in southeastern Spain [4,40]. In CR, inorganic fertilizers are applied to the soil (Table 2). In OR, according to surveys, the most frequent method is to use sheep/goat manure, which is applied every 4 years, and an organic pellet fertilizer every 2 years. In CI, mineral fertilizers, iron chelate, and humic and fulvic acids are applied through fertigation. In OI, organic pellets are supplied every 2 years, as well as iron chelate and humic and fulvic acids through fertigation.

- Phytosanitary practices. A standard treatment program was established for each of the scenarios, whose products and quantities are shown in Table 2. The most common practice, for both rainfed and irrigated land, is to carry out four annual treatments, which coincide with or are close to the following phenological stages: (1) budding (10–15 cm); (2) beginning of flowering; (3) pea-size grain; (4) beginning of veraison.

- Herbicides. Herbicides are only used in the CI vineyard (Table 2), in which two annual treatments are carried out during the vegetative period. In the other types of vineyards, tillage is practiced. For the application of herbicides, a tank is used to which two sprayers are attached. Two operators use these to spray both rows of each lane. The herbicide used is glyphosate; despite its danger, it is still the most widely used due to its effectiveness and low cost.

- Harvesting. This is carried out manually, and a tractor with a trailer is used to transport the grapes from the farm to the winery. In this way, the item “harvesting” accounts for the manual and mechanical means required for the harvest.

- Maintenance. The cost of the maintenance is calculated as a percentage (1.50%) of the cost of the fixed assets: the warehouse, the head, and the irrigation installation (the latter two exclusively in CI and OI).

- Permanent staff. The most frequent tenure regime for vineyards in Murcia is ownership. The owner usually works on the farm in tasks related to management and the production process, such as acquisition of production factors, irrigation programming, where appropriate, contracting external workers, and supporting them (harvesting, pruning, etc.). The owner is a figure similar to that of a manager of a farm belonging to a company. This concept is reflected as a cost in hours per hectare and year.

- Water (irrigation). The irrigation programs were designed using data from three SIAM [33] agrometeorological stations: JU12 (Cañada del Judío), JU71 (Las Encebras), and JU81 (Román). The irrigation allocations were obtained through the calculation of the water demand for an average year, and an RDI strategy was applied [4,6,15]. The annual allocation of the irrigated vineyards is 1230 m3 ha−1 (Table 2).

- Electric power. This is the power consumed by the irrigation head in the distribution of water. It was calculated based on the flow rate, irrigation hours, average manometric height, and unit cost of energy.

2.4.2. Economic Indicators

- NM/investment (NM/K0) (%): profitability in the long term;

- NM/variable costs (NM/c) (%): short-term return on invested capital;

- NM/total cost (NM/C) (%): global profitability of the productive activity;

- Viability threshold (VT) (€ ha−1): minimum price of the grape for the activity to be viable;

- Break-even point (BP) (kg ha−1): minimum production, under the conditions of the grape’s average market price, for the activity to be viable.

2.5. Socio-Territorial Analysis

- Agricultural Work Unit (AWU ha−1): this indicates the generation of employment for each hectare. To establish the employment generated, the work involved in the agricultural tasks was calculated. In the Region of Murcia, an agricultural work unit (AWU) corresponds to 1800 h.

- Contribution to the regional economy (CRE): equal to the unit income (€ ha−1). This indicator is of a social nature, since it measures the gross economic productivity of agricultural activity, which has repercussions for the environment and the rural population.

- Area threshold (AT): this shows the minimum area (ha) for the farm to be viable. It is calculated at the break-even point (Total Income = Total Cost).

2.6. Life Cycle Assessment

2.6.1. Objective and Scope

- Infrastructure. This corresponds to the investment and fixed assets of the LCC. This includes fuel consumed by machinery during land preparation and planting operations and its emissions to the atmosphere. In the case of the irrigated vineyards (CI and OI), the elements related to fertigation are also contemplated: the reservoir, irrigation head, and irrigation network.

- Machinery. The fuel consumed by the agricultural machinery in the various tasks, as well as its emissions.

- Fertigation. The electrical energy consumed by the water booster pumps in the localized irrigation.

- Fertilizers. The production of inorganic and organic fertilizers, their transport and packaging, and emissions into the air due to the application of nitrogenous compounds to the soil.

- Phytosanitary products. The production of the phytosanitary products and herbicides as well as their transport and packaging.

- Waste treatment. The treatment of infrastructure (metals and plastics) and plastic containers for fertilizers and phytosanitary products. Currently, both plastic and metal items are recycled at a rate of at least 90%.

2.6.2. Life Cycle Inventory

2.6.3. Life Cycle Impact: Assessment and Interpretation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Economic Analysis

3.1.1. Productive Structure of Costs and Income

3.1.2. Economic Indicators

3.1.3. Sensitivity Analysis

3.2. Socio-Territorial Analysis

3.3. Life Cycle Analysis

3.3.1. Contribution Analysis

3.3.2. Conventional vs. Organic Vineyard

3.3.3. Rainfed vs. Irrigated Vineyards

3.3.4. Global Warming

3.4. Environmental Costs and Production Costs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AFI. Importancia Económica y Social del Sector Vitivinícola en España; Interprofesional del Vino de España: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- García García, J. Actualización de la contabilidad de costes del cultivo de viña en la Región de Murcia. Enoviticultura 2016, 39, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- García García, J.; García García, B. Aspectos socioeconómicos y ambientales del cultivo de la uva Monastrell. In El Libro de la Monastrell; Riquelme, F., Martínez-Cutillas, A., Eds.; Consejería de Agua, Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca de la Región de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2018; pp. 71–88. ISBN 978-84-09-06249-2. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Azorín, P.; García García, J. The Productive, Economic, and Social Efficiency of Vineyards Using Combined Drought-Tolerant Rootstocks and Efficient Low Water Volume Deficit Irrigation Techniques under Mediterranean Semiarid Conditions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CARM. Estadística Agraria de Murcia 2019/20; Comunidad Autónoma de la Región de Murcia; Consejería de Agua, Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca, Medio Ambiente y Emergencias: Murcia, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- García García, J.; Martínez-Cutillas, A.; Romero, P. Financial Analysis of Wine Grape Production Using Regulated Deficit Irrigation and Partial-Root Zone Drying Strategies. Irrig. Sci. 2012, 30, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Castellanos, B.; García-García, B.; García-García, J. Evaluación de la sostenibilidad de tres sistemas de cultivo de viña característicos de la Región de Murcia. ITEA 2021, 118, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAPA. Anuario de Estadística. Avance 2021; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, P.; García García, J.; Fernández-Fernández, J.I.; Gil Muñoz, R.; del Amor Saavedra, F.; Martínez-Cutillas, A. Improving Berry and Wine Quality Attributes and Vineyard Economic Efficiency by Long-Term Deficit Irrigation Practices under Semiarid Conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 203, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; García de Cortazar, I.; Malheiro, A.C.; Santos, J.A. Modelling Climate Change Impacts on Viticultural Yield, Phenology and Stress Conditions in Europe. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 3774–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resco, P.; Iglesias, A.; Bardají, I.; Sotés, V. Exploring Adaptation Choices for Grapevine Regions in Spain. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2016, 16, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcón, F.; Pedrero, F.; Martín Ortega, J.; Arcas, N.; Alarcon, J.J.; De Miguel, M.D. The Non-Market Value of Reclaimed Wastewater for Use in Agriculture: A Contingent Valuation Approach. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 8, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto García, M.; Martínez Álvarez, V.; Martín Górriz, B. El Regadío en la Región de Murcia. Caracterización y Análisis Mediante Indicadores de Gestión; Sindicato Central de Regantes del Acueducto Tajo-Segura: Murcia, Spain, 2014; ISBN 978-84-697-0372-4. [Google Scholar]

- Maestre Valero, J.F.; Martín Górriz, B.; Alarcón, J.J.; Nicolás, E.; Martínez Álvarez, V. Economic Feasibility of Implementing Regulated Deficit Irrigation with Reclaimed Water in a Grapefruit Orchard. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 178, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Gil Muñoz, R.; Fernández-Fernández, J.I.; del Amor, F.M.; Martínez-Cutillas, A.; García-García, J. Improvement of Yield and Grape and Wine Composition in Field-Grown Monastrell Grapevines by Partial Root Zone Irrigation, in Comparison with Regulated Deficit Irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 149, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, G. The Environmental Impact of a Sardinian Wine by Partial Life Cycle Assessment. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Agricultura-Introducción; European Environment Information and Observation (Eionet): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McEldowney, J. EU Agricultural Policy and Climate Change; EPRS, European Parliament: Luxenbourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, N.; Taylor, C.; Strick, S. Wine Consumers’ Environmental Knowledge and Attitudes: Influence on Willingness to Purchase. IJWR 2009, 1, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barry, M.T. Life Cycle Assessment and the New Zealand Wine Industry: A Tool to Support Continuous Environmental Improvement; Massa University: Wellington, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fusi, A.; Guidetti, R.; Benedetto, G. Delving into the Environmental Aspect of a Sardinian White Wine: From Partial to Total Life Cycle Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 472, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- European Commission Analysis of Links between CAP Reform and Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- ISO. ISO 14040 Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment: Principles and Framework; International Organization for Standards (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Notarnicola, B.; Sala, S.; Anton, A.; J McLaren, S.; Saouter, E.; Sonesson, U. The Role of Life Cycle Assessment in Supporting Sustainable Agri-Food Systems: A Review of the Challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Pineda, I.; Lee, Y.D.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, S.M.; Park, K.S. Review of Inventory Data in Life Cycle Assessment Applied in Production of Fresh Tomato in Greenhouse. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 124395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, C.; De Feo, G. Life Cycle Assessment Application to the Wine Sector: A Critical Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strano, A.; De Luca, A.I.; Falcone, G.; Iofrida, N.; Stillitano, T.; Gulisano, G. Economic and Environmental Sustainability Assessment of Wine Grape Production Scenarios in Southern Italy. Agric. Sci. 2013, 04, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tamburini, E.; Pedrini, P.; Marchetti, M.; Fano, E.; Castaldelli, G. Life Cycle Based Evaluation of Environmental and Economic Impacts of Agricultural Productions in the Mediterranean Area. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2915–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Falcone, G.; De Luca, A.I.; Stillitano, T.; Strano, A.; Romeo, G.; Gulisano, G. Assessment of Environmental and Economic Impacts of Vine-Growing Combining Life Cycle Assessment, Life Cycle Costing and Multicriterial Analysis. Sustainability 2016, 8, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, C.; Rosentrater, K.A. Estimating Economic and Environmental Impacts of Red-Wine-Making Processes in the USA. Fermentation 2019, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García García, J.; García García, B. Sustainability Assessment of Greenhouse Pepper Production Scenarios in Southeastern Spain. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera-Muñoz, F.A.; García García, B.; Ponce-Palafox, J.T.; Wicab-Gutierrez, O.; Castillo-Vargasmachuca, S.G.; García García, J. Sustainability Assessment of White Shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) Production in Super-Intensive System in the Municipality of San Blas, Nayarit, Mexico. Water 2021, 13, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistema de Información Agrario de Murcia. Available online: http://siam.imida.es/apex/f?p=101:1:8751385424600662 (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Romero, P.; Botía, P.; Navarro, J.M. Selecting Rootstocks to Improve Vine Performance and Vineyard Sustainability in Deficit Irrigated Monastrell Grapevines under Semiarid Conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 209, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García García, J.; Contreras López, F.; Usai, D.; Visani, C. Economic Assessment and Socio-Economic Evaluation of Water Use Efficiency in Artichoke Cultivation. Open J. Account. 2013, 02, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Contreras, F.; Garrido, I.; Hellín, P.; Flores, P.; García, J.; Navarro Pay, N.; Navarro, S.; Fenoll, J. Financial Assessment of an In-Farm Remediation System for the Reuse of Agro-Wastewater with Pesticides. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 256, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García García, J. Estructura de Costes de las Orientaciones Productivas Agrícolas de la Región de Murcia: Frutos Secos, Frutales de Pepita, Vid y Olivo; Técnica; Consejería de Agua, Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca de la Región de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- MAPA. Secuestro de Carbono y Mejora de los Suelos en Cultivos Agrícolas Mediterráneos; Guía de Buenas Prácticas Agrarias CARBOCERT; Unión Europea, Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MAGRAMA. Guía Práctica de la Fertilización Racional de los Cultivos en España; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino: Madrid, Spain, 2010; ISBN 978-84-491-0997-3. [Google Scholar]

- Giner, J.F.; Arciniega, L. La nutrición de la viña. Agrícola Vergel 2004, 267, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- MAPA Resultados Técnico-Económicos de Frutales 2017; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, 2019.

- ISO. ISO 14044 Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment: Requirements and Guidelines; International Organization for Standards (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- PRé. Introduction to LCA with SimaPro; PRé: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EEA. EMEP/EEA Air Pollution Emission Inventory Guidebook 2019. Technical Guidance to Prepare National Emission Inventories; EEA Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxenbourg, 2019; ISBN 978-92-9213-806-6. [Google Scholar]

- Del Hierro, Ó.; Gallejones, P.; Besga, G.; Artetxe, A.; Garbisu, C. A Comparison of IPCC Guidelines and Allocation Methods to Estimate the Environmental Impact of Barley Production in the Basque Country through Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Agriculture 2021, 11, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Calvo Buendia, E., Tanabe, K., Kranjc, A., Baasansuren, J., Fukuda, M., Ngarize, S., Osako, A., Pyrozhenco, Y., Shermanau, P., Federici, S., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-4-88788-232-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pergola, M.; D’Amico, M.; Celano, G.; Palese, A.M.; Scuderi, A.; Di Vita, G.; Pappalardo, G.; Inglese, P. Sustainability Evaluation of Sicily’s Lemon and Orange Production: An Energy, Economic and Environmental Analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 128, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beccali, M.; Cellura, M.; Iudicello, M.; Mistretta, M. Resource Consumption and Environmental Impacts of the Agrofood Sector: Life Cycle Assessment of Italian Citrus-Based Products. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazulla, C.; Raugei, M.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P. Taking a Life Cycle Look at Crianza Wine Production in Spain: Where Are the Bottlenecks? Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, S.; Di Bene, C.; Galli, M.; Remorini, D.; Massai, R.; Bonari, E. Greenhouse Gas Emissions in the Agricultural Phase of Wine Production in the Maremma Rural District in Tuscany, Italy. Ital. J. Agron. 2011, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villanueva-Rey, P.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment in the Wine Sector: Biodynamic vs Conventional Viticulture Activities in NW Spain. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García García, B.; Rosique Jiménez, C.; Aguado-Giménez, F.; García García, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Gilthead Seabream (Sparus Aurata) Production in Offshore Fish Farms. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García García, B.; Rosique Jiménez, C.; Aguado-Giménez, F.; García García, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Seabass (Dicentrarchus Labrax) Produced in Offshore Fish Farms: Variability and Multiple Regression Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruiz Sanchez, M.C.; Domingo, R.; Castel, J.R. Review Deficit Irrigation in Fruit Trees and Vines in Spain. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 8, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández Alcázar, J.I. Costes de cultivo en viñedo. Cuad. Campo 2011, 46, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, A.; Puig, R.; Kılıç, E.; Penavayre, S.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P. Eco-Innovation and Benchmarking of Carbon Footprint Data for Vineyards and Wineries in Spain and France. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1661–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjón, S. Especial Informe de Vendimias 2018. La Sem. Vitiviníc. 2018, 3529, 1734–1739. [Google Scholar]

- Bajusová, Z.; Svoradová, L.; Dovác, D.; Bajus, P. Evaluation of the Impact of Labour Costs Development on Grapevine Production in the Slovak Republic through Algorithms. In International Scientific Days 2016. The Agri-Food Value Chain: Challenges for Natural Resources Management and Society; Horská, E., Kapsdorferová, Z., Hallová, M., Eds.; Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra: Nitra, Slovakia, 2016; ISBN 978-80-552-1503-7. [Google Scholar]

- Torrellas, M.; Antón, A.; López, J.C.; Baeza, E.J.; Pérez Parra, J.; Muñoz, P.; Montero, J.I. LCA of a Tomato Crop in a Multi-Tunnel Greenhouse in Almeria. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2012, 17, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balafoutis, A.T.; Koundouras, S.; Anastasiou, E.; Fountas, S.; Arvanitis, K. Life Cycle Assessment of Two Vineyards after the Application of Precision Viticulture Techniques: A Case Study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boulard, T.; Raeppel, C.; Brun, R.; Lecompte, F.; Hayer, F.; Carmassi, G.; Gaillard, G. Environmental Impact of Greenhouse Tomato Production in France. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 31, 757–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keyes, S.; Tyedmers, P.; Beazley, K. Evaluating the Environmental Impacts of Conventional and Organic Apple Production in Nova Scotia, Canada, through Life Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 104, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rinaldi, S.; Bonamente, E.; Scrucca, F.; Merico, M.C.; Asdrubali, F.; Cotana, F. Water and Carbon Footprint of Wine: Methodology Review and Application to a Case Study. Sustainability 2016, 8, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meier, M.S.; Stoessel, F.; Jungbluth, N.; Juraske, R.; Schader, C.; Stolze, M. Environmental Impacts of Organic and Conventional Agricultural Products—Are the Differences Captured by Life Cycle Assessment? J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 149, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisterling, K.; Samaras, C.; Schweizer, V. Decisions to Reduce Greenhouse Gases from Agriculture and Product Transport: LCA Case Study of Organic and Conventional Wheat. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribal, J.; Ramírez-Sanz, C.; Estruch, V.; Clemente, G.; Sanjuán, N. Organic versus Conventional Citrus. Impact Assessment and Variability Analysis in the Comunitat Valenciana (Spain). Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzisymeon, E.; Foteinis, S.; Borthwick, A.G.L. Life Cycle Assessment of the Environmental Performance of Conventional and Organic Methods of Open Field Pepper Cultivation System. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García García, J.; García García, B.; García Castellanos, B. Manual de Buenas Prácticas Para el Cultivo de la Viña en la Región de Murcia; Grupo Operativo QVALITAS: Murcia, Spain, 2021; ISBN 978-84-09-32135-3. [Google Scholar]

| CR | OR | CI | OI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Useful life of the vineyard (years) | 30 | 30 | 25 | 25 |

| Average area (ha) | 30 | 30 | 10 | 10 |

| Planting scheme (m × m) | 2.5 × 2.5 | 2.5 × 2.5 | 3 × 1.2 | 3 × 1.2 |

| Yield in productive years (kg ha−1) | 3500 | 3250 | 8000 | 7250 |

| Non-productive years | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Partially productive years (%) * | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | ||

| Infrastructure (Useful life, years) | ATW (30 yrs.) | ATW (30 yrs.) | ATW (25 yrs.) WR (25 yrs.) IE (15 yrs.) IN (10 yrs.) | ATW (25 yrs.) WR (25 yrs.) IE (15 yrs.) IN (10 yrs.) |

| Fertilizer balance (N-P2O5-K2O) | 20-12-35 | 20-12-35 | 42-23-73 | 42-23-73 |

| Inorganic fertilizers | Nitrates Phosphates | Nitrates Phosphoric acid | ||

| Organic fertilizers | Manure, Organic | Organic | ||

| Phytosanitary | Sulfur Penconazole Bacillus thuringiensis | Sulfur | Sulfur Penconazole Bacillus thuringiensis Glyphosate | Sulfur Carbonate (**) |

| CR | IR | CI | OI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irrigation | ||||

| Water (m3) | 1230.00 | 1230.00 | ||

| Electricity (kW∙h) | 162.80 | 162.80 | ||

| Agricultural machinery | ||||

| Diesel (dm3) | 116.45 | 113.42 | 113.8 | 107.76 |

| Fertilizers | ||||

| Ammonium nitrate (kg) | 24.00 | 26.70 | ||

| Potassium nitrate (kg) | 75.00 | 158.60 | ||

| Magnesium nitrate (kg) | 112.80 | |||

| Phosphoric acid (dm3) | 27.60 | |||

| Ammonium phosphate (kg) | 20.00 | |||

| Iron chelate (kg) | 1.60 | 1.60 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Humic and fulvic acids (kg) | 3.20 | 10.00 | 10.00 | |

| Manure (kg) | 1000.00 | |||

| Organic fertilizer (kg) | 110.00 | 740.00 | ||

| Phytosanitary products | ||||

| Sulfur (kg) | 30.60 | 76.60 | 37.20 | 64.00 |

| Bacillus thuringiensis (kg) | 0.45 | 0.60 | ||

| Penconazole (dm3) | 0.16 | 0.20 | ||

| Potassium hydrogen carbonate (kg) | 3.00 | |||

| Glyphosate (dm3) | 8.00 |

| Components | Units | CR | OR | CI | OI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planting | |||||

| Diesel | g | 2.6490 | 2.8528 | 1.4589 | 1.6098 |

| Irrigation reservoir | |||||

| Diesel | g | 1.7491 | 1.9300 | ||

| HDPE sheet | g | 0.7551 | 0.8332 | ||

| Irrigation equipment | |||||

| Iron | mg | 45.2899 | 49.9750 | ||

| Steel | mg | 4.5290 | 4.9975 | ||

| Copper | mg | 13.5870 | 14.9925 | ||

| Brass | mg | 0.9058 | 0.9995 | ||

| PVC pipe | mg | 36.2319 | 39.9800 | ||

| LDPE pipe | mg | 1.8116 | 1.9990 | ||

| Polyamide | mg | 2.7174 | 2.9985 | ||

| HDPE tanks | mg | 40.7609 | 44.9775 | ||

| Irrigation network | |||||

| LDPE pipe | g | 4.4127 | 4.8692 | ||

| Trellising system | |||||

| Steel pipe | g | 9.2609 | 10.2189 | ||

| Steel wire | g | 2.7641 | 3.0501 | ||

| Agricultural machinery | |||||

| Diesel | 29.0502 | 30.5110 | 12.3615 | 12.9466 | |

| Irrigation | |||||

| Electricity | kW∙h | 0.0215 | 0.0237 | ||

| Fertilizers | |||||

| Magnesium nitrate | gN | 2.8957 | |||

| Potassium nitrate | gN | 3.2393 | 2.9681 | ||

| Ammonium nitrate | gN | 2.6186 | 1.2699 | ||

| Phosphoric acid | g | 3.4500 | |||

| Manure | gN | 2.1315 | |||

| Organic fertilizer | gN | 2.1120 | 6.3460 | ||

| Phytosanitary products | |||||

| Sulfur | g | 7.7563 | 21.5690 | 4.2813 | 8.3353 |

| Penconazole | g | 0.0085 | 0.0049 | ||

| P H carbonate (*) | g | 0.3412 | |||

| Glyphosate | g | 0.9700 | |||

| Waste treatment | |||||

| Plastics to landfill | g | 0.0053 | 0.0051 | 0.5307 | 0.5815 |

| Plastic recycling | g | 0.0526 | 0.0509 | 4.7767 | 5.2331 |

| Metal to landfill | g | 1.2089 | 1.3340 | ||

| Metal recycling | g | 10.8804 | 12.0059 |

| Concept | CR | OR | CI | OI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC (€ ha−1) | RC (%) | AC (€ ha−1) | RC (%) | Cost (€ ha−1) | %/TC (%) | Cost (€ ha−1) | %/TC (%) | |

| Fixed costs | ||||||||

| Shed for equipment | 7.61 | 0.52 | 7.61 | 0.56 | 25.58 | 0.71 | 25.58 | 0.77 |

| Land preparation and planting | 124.02 | 8.52 | 124.02 | 9.05 | 360.25 | 10.00 | 360.25 | 10.90 |

| Auxiliary material | 3.38 | 0.23 | 3.38 | 0.25 | 10.15 | 0.28 | 10.15 | 0.31 |

| Irrigation equipment | 66.15 | 1.84 | 66.15 | 2.00 | ||||

| Irrigation network | 251.15 | 6.97 | 251.15 | 7.60 | ||||

| Irrigation reservoir | 18.71 | 0.52 | 18.71 | 0.57 | ||||

| Total fixed costs (€ ha−1) | 135.02 | 9.27 | 135.02 | 9.85 | 731.99 | 20.32 | 731.99 | 22.05 |

| Variable costs | ||||||||

| Production insurance | 85.26 | 5.85 | 79.17 | 5.78 | 194.88 | 5.41 | 176.61 | 5.32 |

| Pruning | 221.68 | 15.22 | 221.68 | 16.17 | 475.02 | 13.18 | 475.02 | 14.31 |

| Machinery | 413.11 | 28.37 | 399.02 | 29.11 | 514.00 | 14.27 | 422.49 | 12.72 |

| Fertilizers | 117.81 | 8.09 | 76.53 | 5.58 | 318.62 | 8.84 | 225.84 | 6.80 |

| Phytosanitary | 49.33 | 3.39 | 42.83 | 3.12 | 62.32 | 1.73 | 94.60 | 2.85 |

| Herbicides | 64.96 | 1.80 | ||||||

| Harvest | 283.85 | 19.49 | 266.28 | 19.43 | 544.24 | 15.11 | 496.74 | 14.96 |

| Maintenance | 4.57 | 0.31 | 4.57 | 0.33 | 66.26 | 1.84 | 66.26 | 2.00 |

| Permanent staff | 145.67 | 10.00 | 145.67 | 10.63 | 291.35 | 8.09 | 291.35 | 8.77 |

| Irrigation water | 299.63 | 8.32 | 299.63 | 9.02 | ||||

| Electricity (irrigation) | 39.67 | 1.10 | 39.67 | 1.19 | ||||

| Total variable costs (€ ha−1) | 1321.27 | 90.73 | 1235.75 | 90.15 | 2870.94 | 79.68 | 2588.20 | 77.95 |

| CR | OR | CI | OI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production (kg ha−1) | 3500 | 3250 | 8000 | 7250 |

| Baumé degrees (°Baumé) | 14.50 | 14.50 | 14.00 | 14.00 |

| Price (€kg °Baumé −1) | 0.0343 | 0.0343 | 0.0343 | 0.0343 |

| Total income (€ ha−1) | 1739 | 1615 | 3838 | 3478 |

| CR | OR | CI | OI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM/Investment (%) | 7.10 | 6.13 | 1.69 | 1.13 |

| NM/Variable costs (%) | 21.40 | 19.75 | 8.18 | 6.10 |

| NM/Total costs (%) | 19.42 | 17.80 | 6.52 | 4.76 |

| Viability threshold (€ kg−1) | 0.416 | 0.422 | 0.450 | 0.458 |

| Break-even point (kg ha−1) | 2931 | 2759 | 7510 | 6921 |

| CR | OR | CI | OI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWU ha−1 | 0.050 | 0.048 | 0.099 | 0.093 |

| Contribution to the regional economy (€ ha−1) | 1739 | 1615 | 3838 | 3478 |

| Area threshold (ha) | 25.12 | 25.47 | 9.39 | 9.55 |

| Impact Category | Values | Infrastructure (%) | Machinery (%) | Fertilizers (%) | Phytosanitary (%) | Waste Treatment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Rainfed | ||||||

| AD (kg Sb-eq) | 1.31 × 10−6 | 0.15 | 1.59 | 98.27 | 0.30 | −0.31 |

| ADFF (MJ) | 2.48 × 100 | 5.67 | 62.23 | 29.74 | 2.49 | −0.13 |

| GW (CO2-eq) | 2.49 × 10−1 | 4.00 | 43.91 | 51.61 | 0.51 | −0.03 |

| OLD (kg CFC-11-eq) | 2.63 × 10−8 | 7.04 | 77.26 | 15.43 | 0.65 | −0.38 |

| HT (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 8.03 × 10−2 | 0.85 | 9.28 | 89.19 | 0.73 | −0.05 |

| FWAE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 4.35 × 10−2 | 0.60 | 6.54 | 92.29 | 0.62 | −0.04 |

| MAE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 8.35 × 10+1 | 0.84 | 9.17 | 89.15 | 0.89 | −0.04 |

| TE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 1.86 × 10−4 | 1.49 | 16.35 | 81.47 | 0.71 | −0.03 |

| PO (kg C2H4-eq) | 3.79 × 10−5 | 2.78 | 30.50 | 57.36 | 9.42 | −0.07 |

| A (kg SO2-eq) | 1.27 × 10−3 | 2.19 | 23.98 | 66.96 | 6.90 | −0.02 |

| E (kg PO4-eq) | 3.28 × 10−4 | 1.55 | 17.04 | 81.14 | 0.26 | 0.00 |

| Overall Contribution (%) | 2.47 | 27.08 | 68.42 | 2.13 | −0.10 | |

| Organic Rainfed | ||||||

| AD (kg Sb-eq) | 2.23 × 10−7 | 0.92 | 9.83 | 87.20 | 3.83 | −1.78 |

| ADFF (MJ) | 2.15 × 100 | 7.06 | 75.52 | 9.71 | 7.86 | −0.15 |

| GW (CO2-eq) | 1.62 × 10−1 | 6.63 | 70.86 | 20.50 | 2.06 | −0.05 |

| OLD (kg CFC-11-eq) | 2.59 × 10−8 | 7.72 | 82.53 | 8.48 | 1.65 | −0.37 |

| HT (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 1.89 × 10−2 | 3.88 | 41.52 | 46.86 | 7.95 | −0.21 |

| FWAE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 1.07 × 10−2 | 2.62 | 28.02 | 63.42 | 6.11 | −0.17 |

| MAE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 2.12 × 101 | 3.54 | 37.87 | 50.01 | 8.74 | −0.17 |

| TE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 3.49 × 10−4 | 0.85 | 9.13 | 89.10 | 0.93 | −0.01 |

| PO (kg C2H4-eq) | 3.21 × 10−5 | 3.54 | 37.85 | 27.91 | 30.78 | −0.07 |

| A (kg SO2-eq) | 1.94 × 10−3 | 1.54 | 16.50 | 69.45 | 12.52 | −0.01 |

| E (kg PO4-eq) | 4.07 × 10−4 | 1.35 | 14.44 | 83.71 | 0.50 | 0.00 |

| Overall Contribution (%) | 3.60 | 38.55 | 50.58 | 7.54 | −0.27 | |

| Impact Category | Values | Infrastructure (%) | Machinery (%) | Irrigation (%) | Fertilizers (%) | Phytosanitary (%) | Waste Treatment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Irrigation | |||||||

| AD (kg Sb-eq) | 3.70 × 10−6 | 65.86 | 0.24 | 2.06 | 30.28 | 3.73 | −2.18 |

| ADFF (MJ) | 2.57 × 100 | 50.07 | 25.60 | 3.17 | 31.72 | 7.01 | −17.58 |

| GW (CO2-eq) | 2.20 × 10−1 | 43.66 | 21.14 | 3.14 | 38.24 | 5.20 | −11.38 |

| OLD (kg CFC-11-eq) | 2.33 × 10−8 | 27.96 | 37.19 | 1.67 | 27.27 | 10.07 | −4.16 |

| HT (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 1.19 × 10° | 94.70 | 0.27 | 0.44 | 4.73 | 0.75 | −0.89 |

| FWAE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 2.83 × 10−1 | 84.49 | 0.43 | 2.59 | 11.21 | 2.44 | −1.16 |

| MAE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 4.74 × 102 | 85.19 | 0.69 | 2.81 | 11.04 | 3.37 | −3.09 |

| TE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 1.35 × 10−3 | 83.99 | 0.96 | 5.50 | 7.88 | 2.62 | −0.95 |

| PO (kg C2H4-eq) | 4.46 × 10−5 | 57.46 | 11.04 | 4.42 | 38.85 | 15.64 | −27.41 |

| A (kg SO2-eq) | 1.39 × 10−3 | 36.56 | 9.34 | 3.81 | 48.82 | 6.91 | −5.44 |

| E (kg PO4-eq) | 4.30 × 10−4 | 39.82 | 5.53 | 2.85 | 44.57 | 12.31 | −5.08 |

| Overall Contribution (%) | 60.89 | 10.22 | 2.95 | 26.78 | 6.37 | −7.21 | |

| Organic Irrigation | |||||||

| AD (kg Sb-eq) | 3.65 × 10−6 | 73.56 | 0.25 | 2.30 | 9.18 | 17.06 | −2.35 |

| ADFF (MJ) | 1.97 × 100 | 72.02 | 35.00 | 4.57 | 7.75 | 5.86 | −25.21 |

| GW (CO2-eq) | 1.77 × 10−1 | 59.63 | 27.44 | 4.29 | 21.56 | 2.61 | −15.53 |

| OLD (kg CFC-11-eq) | 2.31 × 10−8 | 30.91 | 39.18 | 1.85 | 5.21 | 27.15 | −4.31 |

| HT (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 1.25 × 10° | 98.87 | 0.27 | 0.46 | 0.71 | 0.62 | −0.92 |

| FWAE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 2.80 × 10−1 | 94.34 | 0.45 | 2.89 | 2.83 | 0.78 | −1.29 |

| MAE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 4.66 × 102 | 95.72 | 0.73 | 3.16 | 2.77 | 1.10 | −3.47 |

| TE (kg 1,4-DB-eq) | 1.79 × 10−3 | 69.83 | 0.76 | 4.57 | 25.18 | 0.45 | −0.79 |

| PO (kg C2H4-eq) | 4.01 × 10−5 | 70.48 | 12.86 | 5.42 | 30.58 | 14.26 | −33.60 |

| A (kg SO2-eq) | 2.01 × 10−3 | 27.80 | 6.74 | 2.90 | 60.46 | 6.23 | −4.13 |

| E (kg PO4-eq) | 5.51 × 10−4 | 34.31 | 4.52 | 2.45 | 61.34 | 1.76 | −4.37 |

| Overall Contribution (%) | 66.13 | 11.66 | 3.17 | 20.69 | 7.08 | −8.73 | |

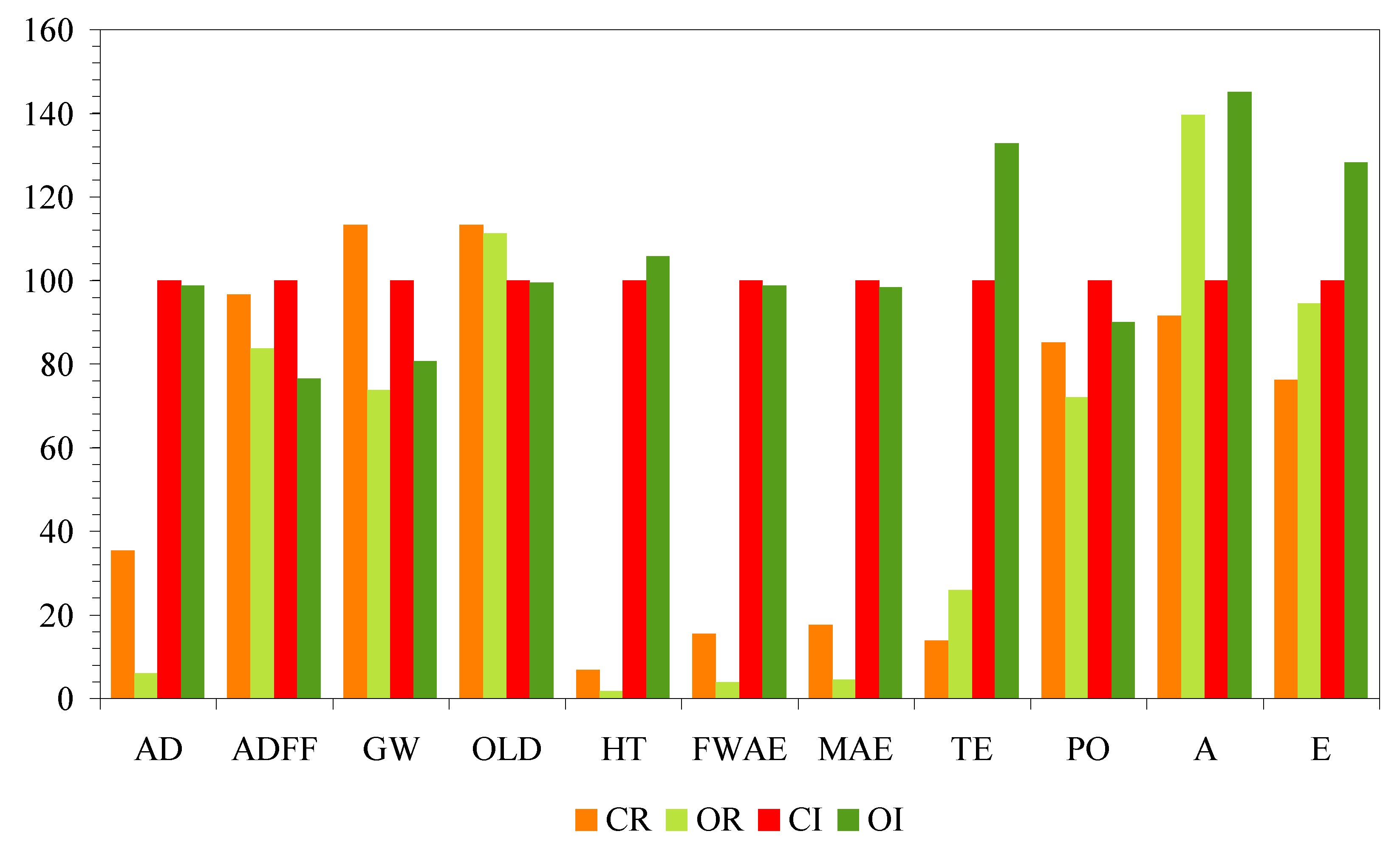

| CR vs. OR | CI vs. OI | CR vs. CI | OR vs. OI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | 82.97 | 1.17 | −182.86 | −1541.20 |

| ADFF | 13.46 | 23.40 | −3.44 | 8.45 |

| GW | 34.92 | 19.32 | 11.62 | −9.57 |

| OLD | 1.68 | 0.58 | 11.61 | 10.62 |

| HT | 76.52 | −5.68 | −1377.01 | −6547.13 |

| FWAE | 75.49 | 1.18 | −550.49 | −2522.26 |

| MAE | 74.56 | 1.80 | −467.96 | −2092.38 |

| TE | −88.09 | −32.70 | −624.43 | −411.11 |

| PO | 15.37 | 10.11 | −17.55 | −24.85 |

| A | −52.65 | −45.07 | −9.30 | −3.87 |

| E | −23.96 | −28.07 | −31.23 | −35.58 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García Castellanos, B.; García García, B.; García García, J. Evaluation of the Sustainability of Vineyards in Semi-Arid Climates: The Case of Southeastern Spain. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3213. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12123213

García Castellanos B, García García B, García García J. Evaluation of the Sustainability of Vineyards in Semi-Arid Climates: The Case of Southeastern Spain. Agronomy. 2022; 12(12):3213. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12123213

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía Castellanos, Begoña, Benjamín García García, and José García García. 2022. "Evaluation of the Sustainability of Vineyards in Semi-Arid Climates: The Case of Southeastern Spain" Agronomy 12, no. 12: 3213. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12123213

APA StyleGarcía Castellanos, B., García García, B., & García García, J. (2022). Evaluation of the Sustainability of Vineyards in Semi-Arid Climates: The Case of Southeastern Spain. Agronomy, 12(12), 3213. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12123213