Shear Bond Strength of Additively and Subtractively Manufactured CAD/CAM Restorative Materials After Different Surface Treatments and Adhesive Strategies: An In Vitro Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The restorative materials have no significant effect on SBS;

- (2)

- The surface treatment protocols have no significant effect on SBS;

- (3)

- The adhesive systems have no significant effect on SBS.

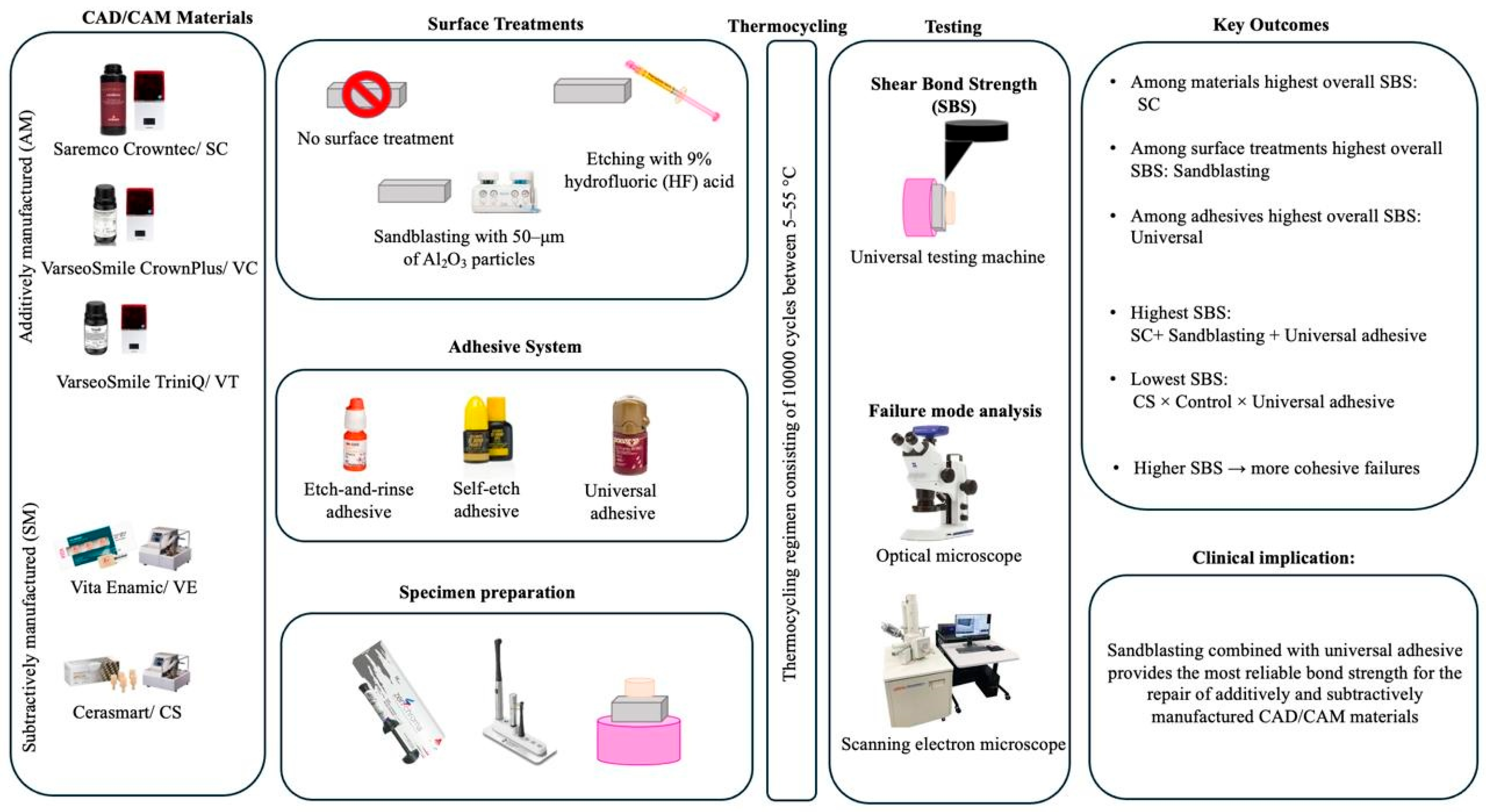

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Restorative Materials Used in the Study

2.2. Specimen Preparation

2.3. Surface Treatment

2.4. Adhesive Procedure and Shear Bond Strength (SBS)

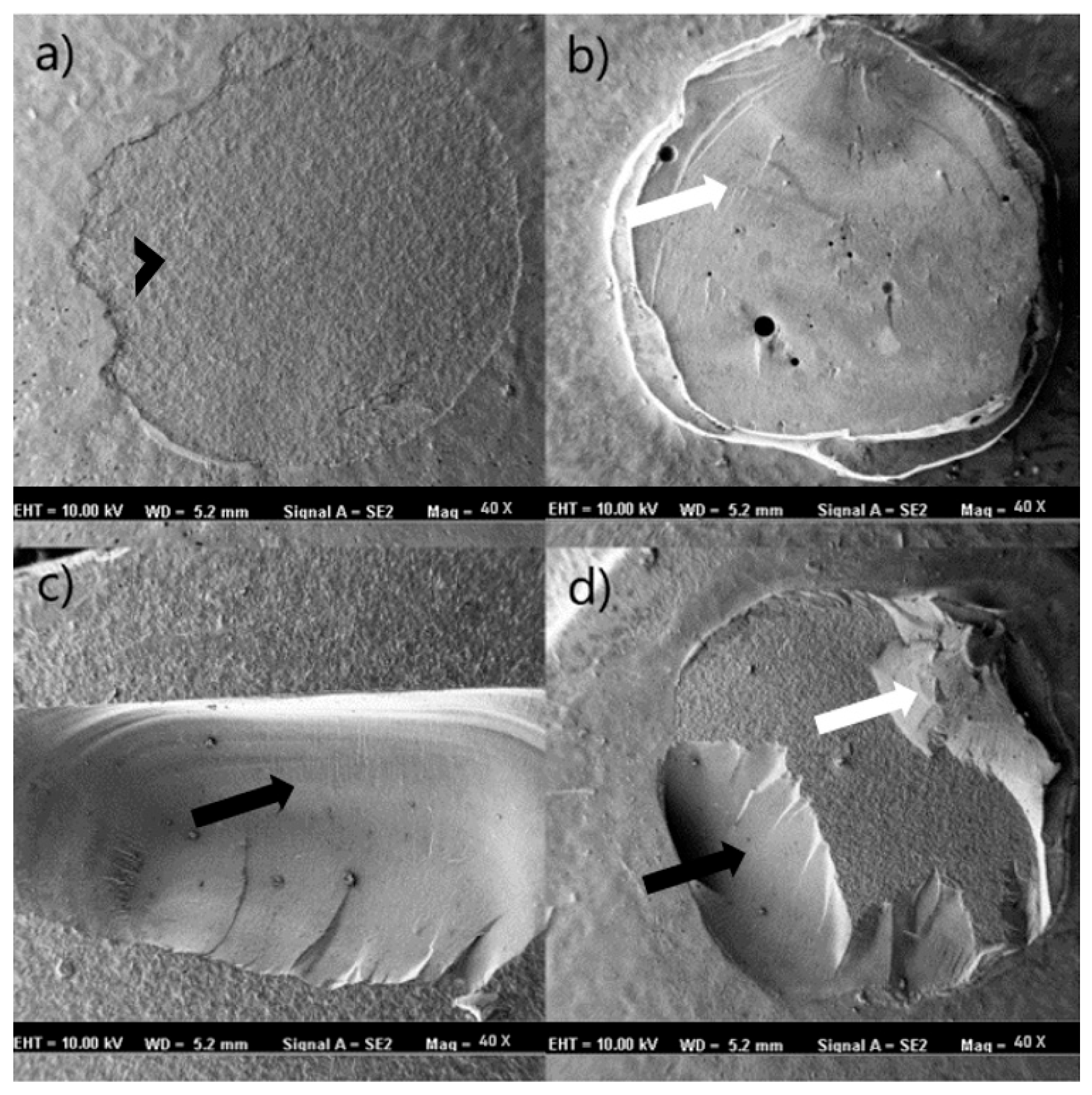

2.5. Stereomicroscope and Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

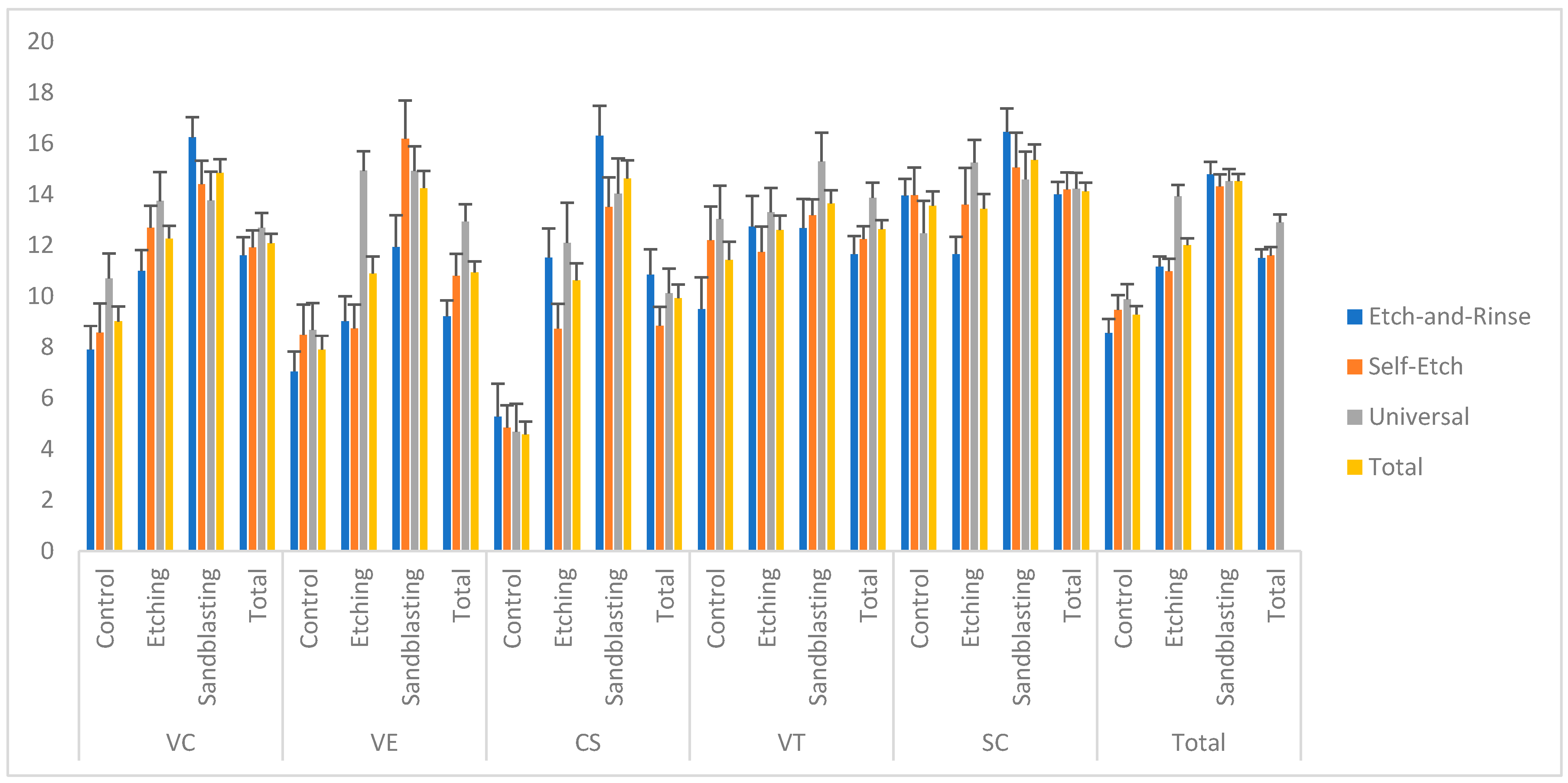

3.1. Shear Bond Strength (SBS)

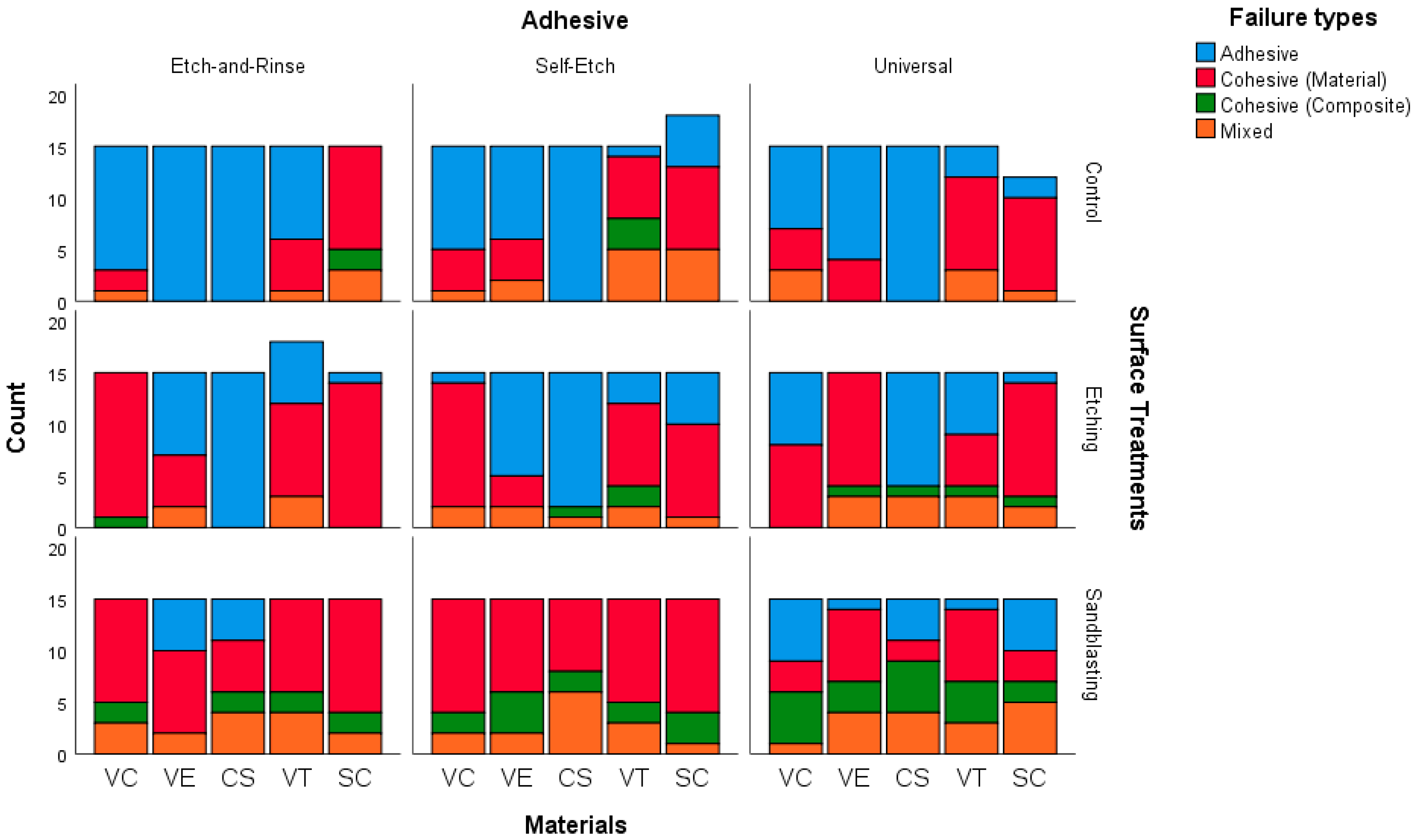

3.2. Failure Type

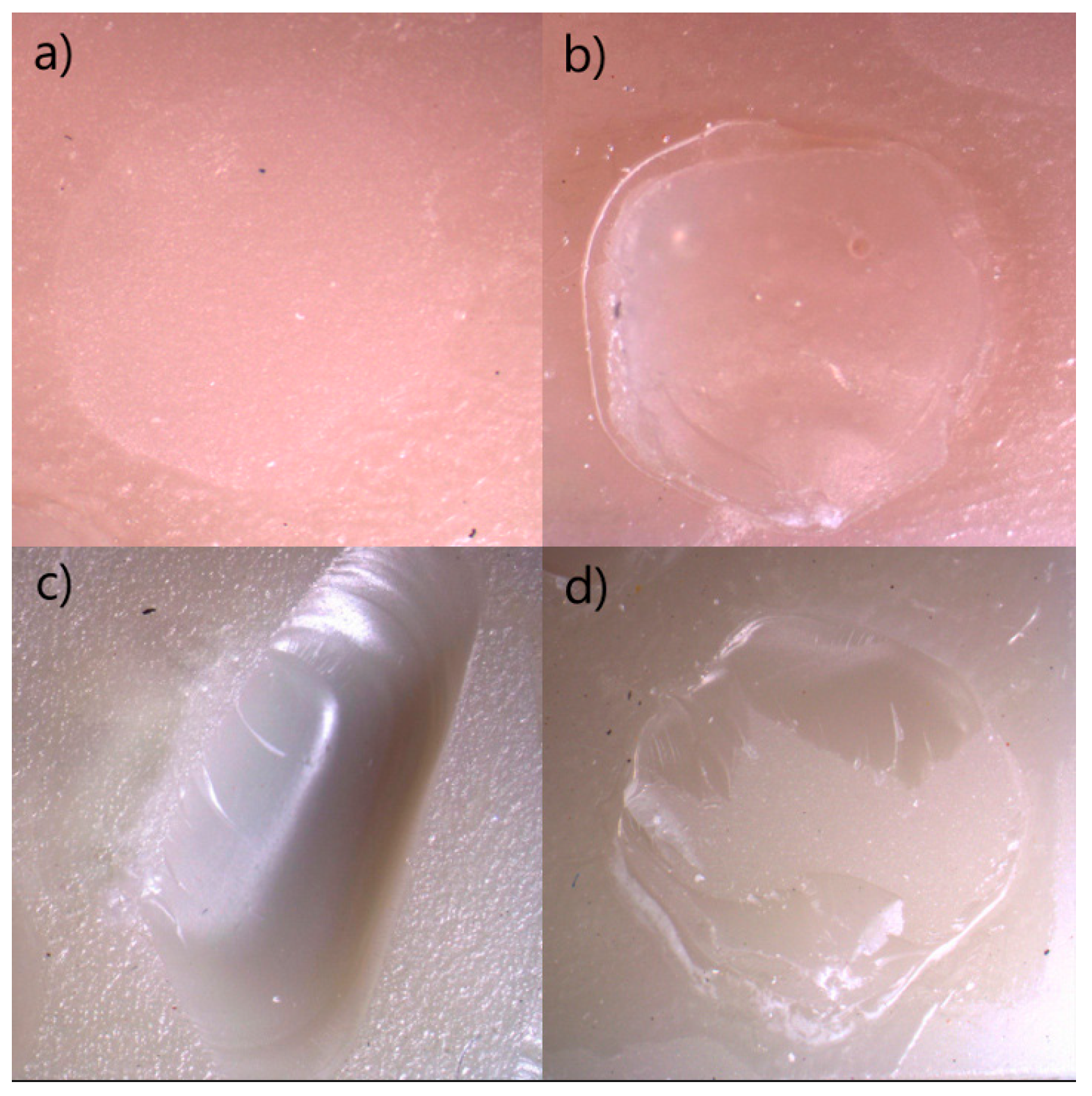

3.3. Assessment of Stereomicroscope and Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SBS | Shear bond strength |

| AM | Additively manufactured |

| SM | Subtractively manufactured |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

References

- Skorulska, A.; Piszko, P.; Rybak, Z.; Szymonowicz, M.; Dobrzyński, M. Review on polymer, ceramic and composite materials for CAD/CAM indirect restorations in dentistry—Application, mechanical characteristics and comparison. Materials 2021, 14, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, J.R.C.D.S.; Rodriguez, R.M.M.; Campos, T.M.B.; Ramos, N.D.C.; Bottino, M.A.; Tribst, J.P.M. Characterization of microstructure, Optical Properties, and mechanical behavior of a Temporary 3D Printing Resin: Impact of Post-curing Time. Materials 2024, 17, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stansbury, J.W.; Idacavage, M.J. 3D printing with polymers: Challenges among expanding options and opportunities. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, N.; Osman, R.; Wismeijer, D. Effects of build direction on the mechanical properties of 3D-printed complete coverage interim dental restorations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striemann, P.; Hülsbusch, D.; Niedermeier, M.; Walther, F. Optimization and quality evaluation of the interlayer bonding performance of additively manufactured polymer structures. Polymers 2020, 12, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-León, M.; Özcan, M. Additive manufacturing technologies used for processing polymers: Current status and potential application in prosthetic dentistry. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, S.; Altuntaş, E.; Şenol, A.A.; Kahramanoğlu, E.; Yılmaz Atalı, P.; Tarçın, B.; Türkmen, C. Evaluation of Shear Bond Strength in the Repair of Additively and Subtractively Manufactured CAD/CAM Materials Using Bulk-Fill Composites. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.T.; Pedrotti, D.; Casagrande, L.; Lenzi, T.L. Risk of failure of repaired versus replaced defective direct restorations in permanent teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 4917–4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaka, S.E. Repair bond strength of resin composite to a novel CAD/CAM hybrid ceramic using different repair systems. Dent. Mater. J. 2015, 34, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; El Bahra, S.; Aryal AC, S.; Padmanabhan, V.; Al Tawil, A.; Saleh, I.; Rahman, M.M.; Guha, U. The effect of chemical surface modification on the repair bond strength of resin composite: An in vitro study. Polymers 2025, 17, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgi, R.; Etienne, O.; Holiel, A.A.; Cuevas-Suárez, C.E.; Hardan, L.; Roman, T.; Flores-Ledesma, A.; Qaddomi, M.; Haikkel, Y.; Kharouf, N. Effectiveness of Surface Treatments on the Bond Strength to 3D-Printed Resins: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Bona, A.; Northeast, S.E. Shear bond strength of resin bonded ceramic after different try-in procedures. J. Dent. 1994, 22, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reymus, M.; Roos, M.; Eichberger, M.; Edelhoff, D.; Hickel, R.; Stawarczyk, B. Bonding to new CAD/CAM resin composites: Influence of air abrasion and conditioning agents as pretreatment strategy. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasahara, Y.; Takamizawa, T.; Hirokane, E.; Tsujimoto, A.; Ishii, R.; Barkmeier, W.W.; Latta, M.A.; Miyazaki, M. Comparison of different etch-and-rinse adhesive systems based on shear fatigue dentin bond strength and morphological features the interface. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, e109–e117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Takagaki, T.; Hatayama, T.; Nikaido, T.; Tagami, J. Update on enamel bonding strategies. Front. Dent. Med. 2021, 2, 666379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meerbeek, B.; Yoshihara, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Mine, A.; De Munck, J.; Van Landuyt, K.L. State of the art of self-etch adhesives. Dent. Mater. 2011, 27, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashley, D.H.; Tay, F.R.; Breschi, L.; Tjäderhane, L.; Carvalho, R.M.; Carrilho, M.; Tezvergil-Mutluay, A. State of the art etch-and-rinse adhesives. Dent. Mater. 2011, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzimas, K.; Rahiotis, C.; Pappa, E. Biofilm Formation on Hybrid, Resin-Based CAD/CAM Materials for Indirect Restorations: A Comprehensive Review. Materials 2024, 17, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Schmidt, F.; Beuer, F.; Yassine, J.; Hey, J.; Prause, E. Effect of surface treatment strategies on bond strength of additively and subtractively manufactured hybrid materials for permanent crowns. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, H.; Sayed, M.E.; Jundus, A.; Gharawi, M.; Baeshen, S.; Alali, M.; Almarzouki, M.; Jokhadar, H.; AlResayes, S.S.; Al Wadei, M.H.D.; et al. Shear strength of repaired 3D-printed and milled provisional materials using different resin materials with and without chemical and mechanical surface treatment. Polymers 2023, 15, 4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutuven, E.O.; Yildirim, N.C. Bond strength of self-adhesive resin cement to definitive resin crown materials manufactured by additive and subtractive methods. Dent. Mater. J. 2025, 44, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım-Işık, H.; Büyükgöze-Dindar, M. Influence of Different Adhesives and Surface Treatments on Shear and Tensile Bond Strength and Microleakage with Micro-CT of Repaired Bulk-Fill Composites. Polymers 2025, 17, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revilla-León, M.; Morillo, J.A.; Att, W.; Özcan, M. Chemical composition, knoop hardness, surface roughness, and adhesion aspects of additively manufactured dental interim materials. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 30, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, N.; Celik Oge, S.; Guney, O.; Okbaz, O.; Sertdemir, Y.A. Comparison of the Shear Bond Strength between a Luting Composite Resin and Both Machinable and Printable Ceramic–Glass Polymer Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarczyk, B.; Liebermann, A.; Eichberger, M.; Güth, J.F. Evaluation of mechanical and optical behavior of current esthetic dental restorative CAD/CAM composites. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 55, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigmeanu, C.V.; Ardelean, L.C.; Rusu, L.C.; Negrutiu, M.L. Additive manufactured polymers in dentistry, current state-of-the-art and future perspectives-a review. Polymers 2022, 14, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awada, A.; Nathanson, D. Mechanical properties of resin-ceramic CAD/CAM restorative materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, F.A.; Boldt, J.; Gierthmuehlen, P. CAD/CAM ceramic restorative materials for natural teeth. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 1082–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, F.A.; Horvath, S.D.; Guess, P.C.; Blatz, M.B. Resin bond to indirect composite and new ceramic/polymer materials: A review of the literature. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2014, 26, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, T.; Preis, V.; Behr, M.; Rosentritt, M. Roughness, surface energy, and superficial damages of CAD/CAM materials after surface treatment. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 2787–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikici, B.; Türkeş Başaran, E.; Şirinsükan, N.; Can, E. Repair Bond Strength and Surface Roughness Evaluation of CAD/CAM Materials After Various Surface Pretreatments. Coatings 2025, 15, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo-Neto, V.G.; de Almeida Nobre, C.F.; Freitas, M.I.M.; Lima, R.B.W.; Sinhoreti, M.A.C.; Cury, A.A.D.B.; Giannini, M. Effect of hydrofluoric acid concentration on bond strength to glass-ceramics: A systematic review and meta-analysis of in-vitro studies. J. Adhes. Dent. 2023, 25, b4646943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, L.T.; Galațanu, S.V.; Opriș, C.; Pop, C.; Jivănescu, A. Effect of different etching times with hydrofluoric acid on the bond strength of CAD/CAM ceramic material. Materials 2022, 15, 7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, A.H.; Moura, D.M.D.; Tribst, J.P.M.; Araújo, A.M.M.D.; Leite, F.P.P. Effect of hydrofluoric acid concentration and etching time on resin-bond strength to different glass ceramics. Braz. Oral Res. 2019, 33, e041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktu, A.; Ulusoy, N. Effect of polishing systems on the surface roughness and color stability of aged and stained bulk-fill resin composites. Materials 2024, 17, 3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, P.V.; Dinesh, U.; Bhat, C.R.; Shetty, P.C. Comparison of shear bond strength of metal brackets bonded to porcelain surface using different surface conditioning methods: An in vitro study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2012, 13, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çulhaoğlu, A.K.; Özkır, S.E.; Şahin, V.; Yılmaz, B.; Kılıçarslan, M.A. Effect of various treatment modalities on surface characteristics and shear bond strengths of polyetheretherketone-based core materials. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakir, N.N.; Demirbuga, S.; Balkaya, H.; Karadaş, M. Bonding performance of universal adhesives on composite repairs, with or without silane application. J. Conserv. Dent. Endod. 2018, 21, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaoka, N.; Yoshihara, K.; Feitosa, V.P.; Tamada, Y.; Irie, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Van Meerbeck, B.; Hayakawa, S. Chemical interaction mechanism of 10-MDP with zirconia. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcon Aguilar, M.; Ferretti, M.A.; Lins, R.B.E.; Silva, J.D.S.; Lima, D.A.N.L.; Marchi, G.M.; Baggio Aguiar, F.H. Effect of Phytic Acid Etching and Airborne-Particle Abrasion Treatment on the Resin Bond Strength. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2024, 16, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrefai, M.; Değirmenci, A.; Pehlivan, I.E. Shear bond strength of resin nanoceramic repairing with various single-shade resin composites. Essent. Dent. 2023, 2, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlOtaibi, A.A.; Taher, N.M. Repair Bond Strength of Two Shadeless Resin Composites Bonded to Various CAD-CAM Substrates with Different Surface Treatments. Coatings 2023, 13, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçay, H.Ç. Evaluation of In-Vitro Aging Procedures in Dentistry: A Traditional Review. Dent. Med. J.-Rev. 2025, 7, 88–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, M.; Darvell, B. Thermal cycling procedures for laboratory testing of dental restorations. J. Dent. 1999, 27, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, S.; Geraldeli, S.; Maia, R.; Raposo, L.H.A.; Soares, C.J.; Yamagawa, J. Adhesion to tooth structure: A critical review of “micro” bond strength test methods. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, e50–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghazzawi, T.F.; Janowski, G.M.; Ning, H.; Eberhardt, A.W. Qualitative SEM analysis of fracture surfaces for dental ceramics and polymers broken by flexural strength testing and crown compression. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 32, e100–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zohairy, A.A.; Saber, M.H.; Abdalla, A.I.; Feilzer, A.J. Efficacy of microtensile versus microshear bond testing for evaluation of bond strength of dental adhesive systems to enamel. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Restorative Materials | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Manufacturer | Composition | LOT | ||

| Saremco Cronwtec (SC) | Saremco, Dental AG, Rebstein, Switzerland | Esterification products of 4,4′-isopropylidiphenol, ethoxylated and 2-methylprop-2enoic acid, silanized dental glass, pyrogenic silica, initiators. Total content of inorganic fillers (particle size 0.7 μm) is 30–50 wt%. | E622 | ||

| VarseoSmile CrownPlus (VC) | BEGO, Bremen, Germany | Esterification products of 4,4′-isopropylidiphenol, ethoxylated and 2-methylprop-2enoic acid, silanized dental glass, methyl benzoylformate, diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide, 30–50 wt%—inorganic fillers (particle size 0.7 μm) | 600985 | ||

| VarseoSmile TriniQ (VT) | BEGO, Bremen, Germany | Bis-GMA, TEGDMA, EBPDMA, Bis-EMA, Silicon dioxide, barium glass, Zirconium oxide, 83.5 wt%, particle size: N/A | 601836 | ||

| Vita Enamic (VE) | Vita Zahnfabrik, Bad Sackingen, Germany | 14 wt% methacrylate polymer (UDMA, TEGDMA) and 86 wt% fine-structure feldspathic ceramic network | 210450 | ||

| Cerasmart (CS) | Gc Corp., Tokyo, Japan | 71% Barium (300 nm) and silicate glass ceramics (20 nm), Bis-MEPP, UDMA, DMA | 2402141 | ||

| ZenChroma | President Dental GmbH, Allershausen, Germany | UDMA, Bis-GMA, TEMDMA, Glass powder, silicon dioxide, inorganic filler (0.005–3.0 μm) | 2024006257 | ||

| Adhesive Systems | |||||

| Product | Manufacturer | Composition | LOT | Application Procedure | |

| Adper Single Bond 2 (Etch-and-rinse system) | 3M ESPE; St. Paul, MN, USA | Bis-GMA; HEMA; Dimethacrylatas; Polyalkanoic acid copolymer; initiators; water; and ethanol | 9950798 | The composite surface was etched with 37% phosphoric acid (FineEtch 37 Gel; Spident Inc., Incheon, Republic of Korea) for 30 s, rinsed thoroughly, and air-dried. Adper Single Bond was then applied with active rubbing for 20 s, gently air-dried for 5 s, and polymerized for 10 s. | |

| Clearfil SE Bond (self-etch system) | Kuraray Inc., Kurashiki, Japan | Primer: 10-MDP; HEMA;Hydrophilic Dimethacrylate; Camphorquinone; water. Adhesive: 10-MDP; HEMA; Bis-GMA; Hydrophobic Dimethacrylate; N, N diethanol p-toluidine; Camphorquinone bond; Silanated colloidal silica | Primer: 2G0426 Bond: 2F0861 | The primer was applied first, followed by 20 s of gentle air-drying. Then, the bonding agent was applied, air-thinned, and cured for 10 s. | |

| G-Premio Bond (universal system) | Gc Corp., Tokyo, Japan | 10-MDP, MDTP, 4-MET, BHT, acetone, water, dimethacrylate monomer, photoinitiator, silica filler; pH: 1.5 | 2503037 | G-Premio Bond was applied for 20 s, air-thinned for 5 s, and light-cured for 20 s. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yavuz, S.A.; Erturk-Avunduk, A.T.; Sagsoz, O.; Delikan, E.; Karatas, O. Shear Bond Strength of Additively and Subtractively Manufactured CAD/CAM Restorative Materials After Different Surface Treatments and Adhesive Strategies: An In Vitro Study. Polymers 2026, 18, 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020296

Yavuz SA, Erturk-Avunduk AT, Sagsoz O, Delikan E, Karatas O. Shear Bond Strength of Additively and Subtractively Manufactured CAD/CAM Restorative Materials After Different Surface Treatments and Adhesive Strategies: An In Vitro Study. Polymers. 2026; 18(2):296. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020296

Chicago/Turabian StyleYavuz, Sevim Atilan, Ayse Tugba Erturk-Avunduk, Omer Sagsoz, Ebru Delikan, and Ozcan Karatas. 2026. "Shear Bond Strength of Additively and Subtractively Manufactured CAD/CAM Restorative Materials After Different Surface Treatments and Adhesive Strategies: An In Vitro Study" Polymers 18, no. 2: 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020296

APA StyleYavuz, S. A., Erturk-Avunduk, A. T., Sagsoz, O., Delikan, E., & Karatas, O. (2026). Shear Bond Strength of Additively and Subtractively Manufactured CAD/CAM Restorative Materials After Different Surface Treatments and Adhesive Strategies: An In Vitro Study. Polymers, 18(2), 296. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18020296