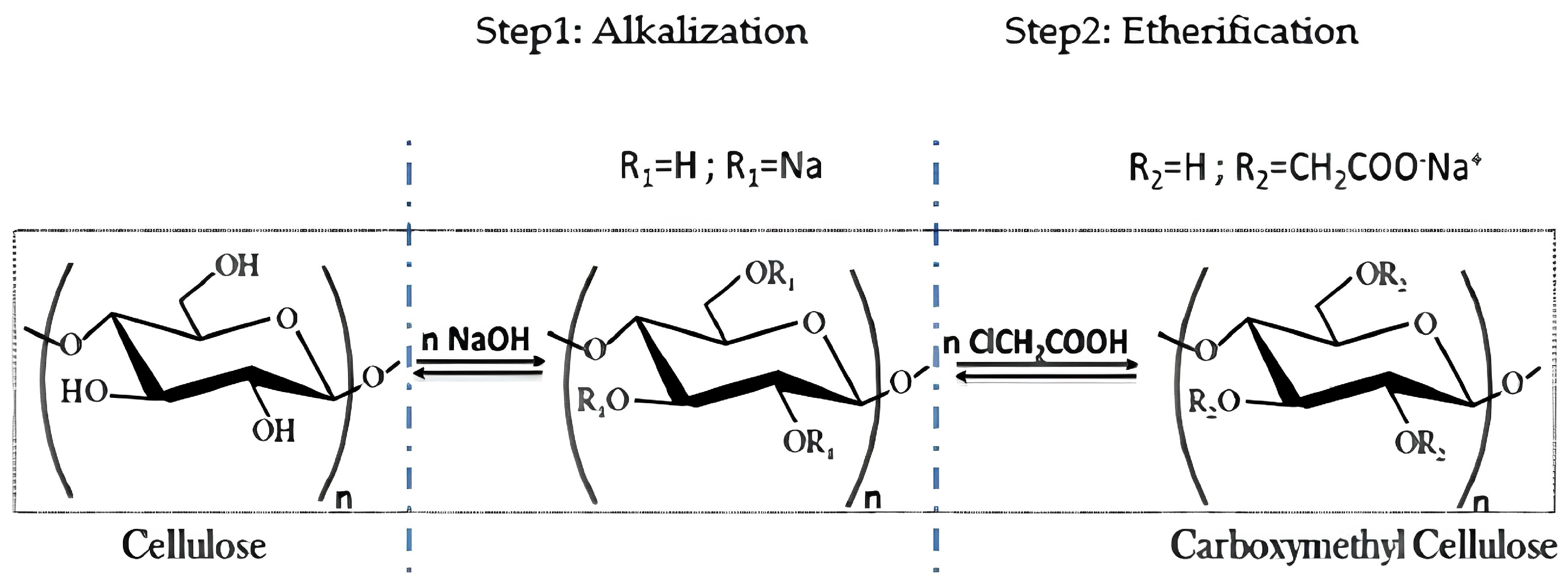

3.1. Characterization of Extracted Cellulose

The chemical composition of Saudi durum wheat straw, used as an agricultural by-product, was determined and presented in

Table 3.

The results indicate that the studied material contains a high α-cellulose content (41 g per 100 g of dry material) and a relatively low lignin content (14 g per 100 g of dry material). This characteristic is particularly important for assessing which is essential for evaluating its suitability as a feedstock for carboxymethyl cellulose (CMCws) production.

The purity of CMCws (%) was determined as the ratio of the final dried weight to the initial biomass weight, yielding a purity of approximately 99%, indicating a high degree of conversion and minimal residual impurities.

The degree of substitution (DS) of the synthesized carboxymethyl cellulose (CMCws) attained a value of 1.23 at monochloroacetic acid (MCA) concentration of 25 g per 10 g of dry cellulose, indicating a high level of carboxymethylation and hydrophilic character.

Correspondingly, the apparent viscosity (η) measured at room temperature and a shear rate of 300 s−1 increased to 903.03 cP, demonstrating the enhanced chain substitution and hydrophilicity of the resulting polymer.

The extracted cellulose exhibited a DPv of approximately 933, corresponding to a viscosimetric molar mass of 151,200 g·mol−1.

3.2. Adhesive Force of CMCws-Sized Warp Yarns

3.2.1. Effect of Size Concentration

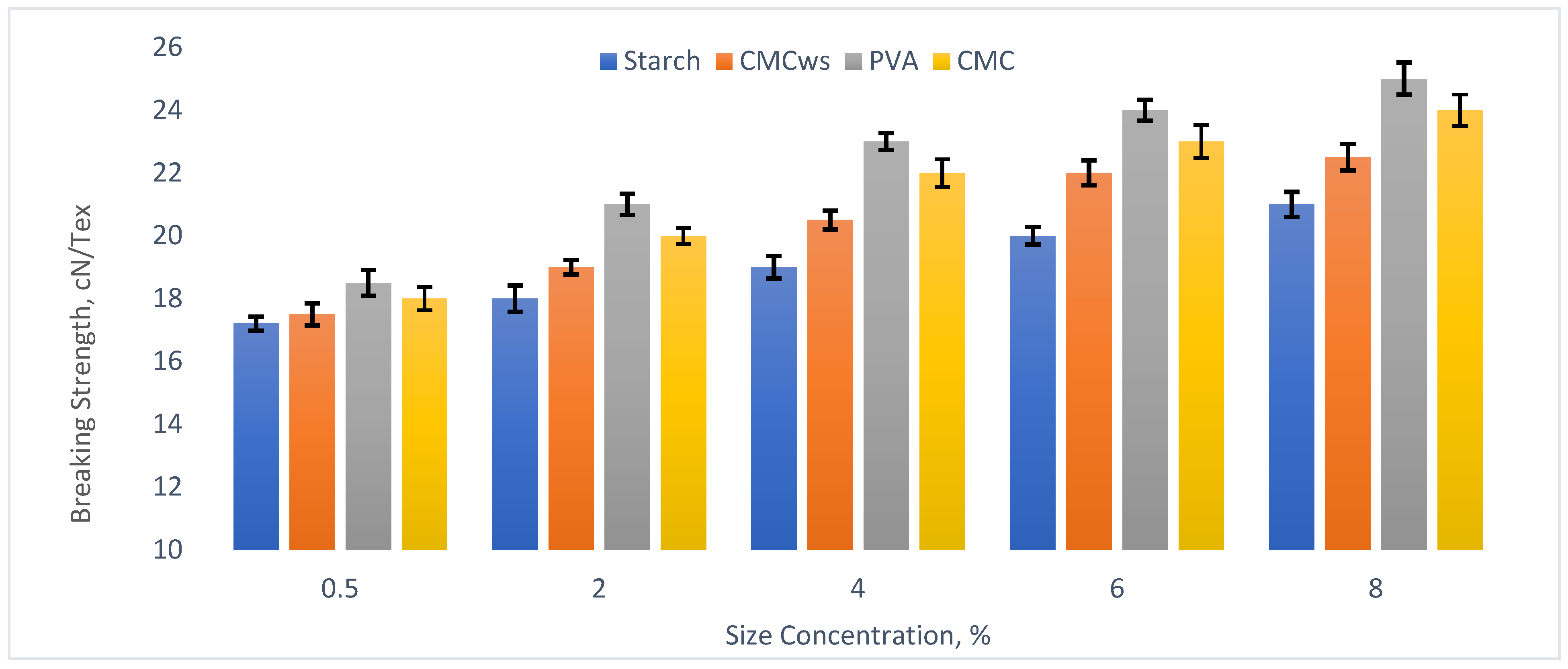

Sizing materials and cotton fiber interaction were assessed by measuring the tensile strength of the sized cotton warp. This parameter reflects the degree of adhesion between the size film and the fiber surface, which directly influences the yarn’s performance during weaving.

Four different sizing agents, maize starch, carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and wheat straw-derived carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC

ws), were applied at varying concentrations, and their effects on the mechanical properties of the cotton yarn were summarized in

Table 4.

Table 4 shows yarn breaking strength (cN/Tex) and corresponding breaking strength gain (%) across increasing size concentrations (0.5–8%) for different agents. Breaking strength rose steadily with higher concentrations, indicating improved fiber cohesion and load transfer. CV% values highlight the relative consistency of each agent’s effect.

The sizing process involves several key stages: wetting, spreading, and film formation on the fiber surface. The size material retained between the fibers helps to bind the fibers together, while the sizing film on the yarn surface provides protection. As shown in

Figure 2, the breaking strength increases with the rising sizing concentration.

As the CMCws concentration increases, a greater number of sizing molecules engage in covering the fiber surface and bonding the fibers together. The thickness of the CMCws film deposited on the yarn surface also increases, thereby enhancing the contribution of the sizing film strength to overall yarn–sizing adhesion. When the concentration reaches 0.5%, the breaking strength of warps sized with different agents shows significantly higher values.

Table 5 presents linear regression results obtained using Minitab

® 22 at a 95% confidence level. This analysis indicates that the adhesion of the CMC

ws sizing material to the fiber is influenced by the sizing concentration. Both the strength of the sizing film and the inherent strength of the fibers contribute to the adhesion force measured using the yarn method, particularly when the sizing concentration exceeds 0.5%.

Regression analysis was performed at a 5% significance level, and the results (p < 0.05) demonstrate a statistically significant effect of sizing concentration on yarn breaking strength (cN/Tex). For CMCws, the high coefficient of determination (R2 = 95.68%) indicates that the regression model explains most of the variability in the response, confirming its strong predictive accuracy.

3.2.2. Influence of Size Squeeze Pressure

The breaking strengths of yarns sized with various materials, starch, PVA, CMC, and CMC

ws, are presented in

Table 6.

It can be observed that the breaking strength of the yarn increases after sizing, compared to the unsized yarn. However, this improvement in strength is accompanied by a reduction in breaking extension. Notably, the application of high-pressure squeezing during the sizing process results in an increase in the breaking strength of yarns treated with the CMCws sizing agent. In terms of uniformity, the breaking strength coefficient of variation (CV) for CMCws was 12.46% at low pressure and 17.28% at high pressure, reflecting relatively consistent yarn properties compared to other sizing agents.

It is evident that yarns sized under high pressure consistently demonstrate improved weaving performance compared to those sized under low pressure. This observation was further supported through structural analysis of the yarn. The increased binding force achieved through sizing enhances the cohesion between fibers, promoting a more uniform roller load distribution during deformation. As a result, the yarn exhibits higher breaking strength and reduced extensibility.

Yarn packing density, defined as the ratio of the cross-sectional area of the fibers to that of the yarn, was measured using an optical microscope. Packing density values range from 0 to 1, where 0 represents completely loose fibers with no compaction, and 1 represents maximum compaction with fibers fully occupying the yarn cross-section.

As shown in

Table 7, yarn packing density increases after sizing, with the highest values observed under high squeeze pressure, indicating that increased pressure compresses the yarn structure and enhances its compactness. While low squeeze pressure leads to a slight increase in yarn diameter compared to unsized yarn, high-pressure squeezing at the same size add-on yields diameters comparable to or smaller than those of unsized yarn. These results confirm that squeeze pressure during sizing compacts the yarn, with compactness rising proportionally to pressure. Reduced yarn diameter is advantageous for weaving, facilitating smoother passage through the reed dents.

Higher packing density enhances fiber cohesion and minimizes interfiber slippage, thereby improving weaving performance [

2]. Our structural analysis indicates that the superior weaving performance of CMC

ws-sized yarns under high-pressure squeezing results from uniform size coating, deeper size penetration, and increased packing density.

Size penetration serves a dual function: it strengthens interfiber binding and provides a stable base for the surface size coating. While the coating protects the yarn and encapsulates protruding fibers, excessive penetration and coating can be detrimental, causing greater size shedding during weaving. In yarns sized under high pressure, although the film thickness is lower, size penetration is greater than in low-pressure-sized yarns with the same size add-on. This enhanced penetration improves interfiber binding and secures the size film to the yarn surface, thereby increasing abrasion resistance [

5].

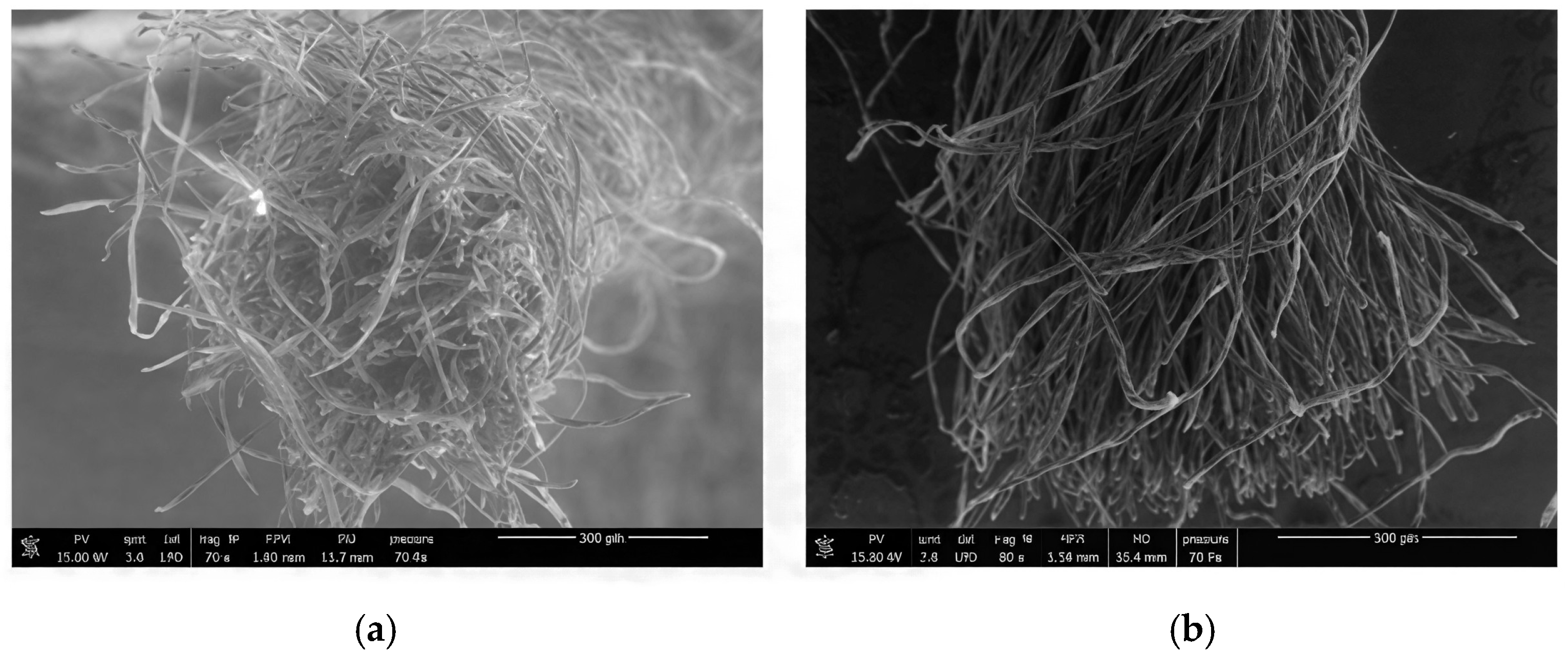

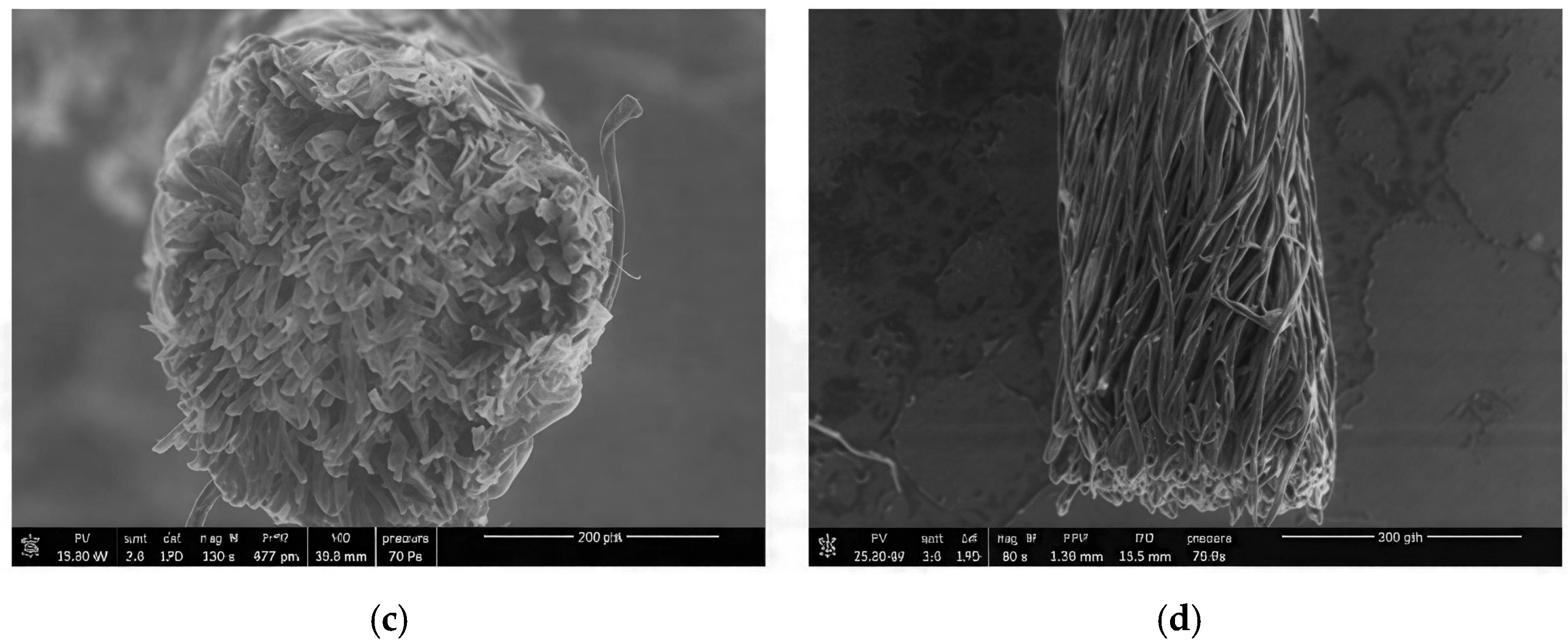

3.4. Effect of CMCws Size Agent on Yarn Surface Structure

Considering the structural composition of yarn, it can be divided into three primary zones:

An external layer composed of loosely oriented fibers with varying spacing relative to the yarn axis. This outermost region is inherently disordered and serves as the primary penetration zone for sizing agents in sized yarns.

A subjacent layer of fibers, more directionally aligned, located at the interface between the disturbance zone and the cohesive core. This intermediate region contributes to both cohesion and disturbance functions.

A core region, or undisturbed body of the yarn, characterized by tightly packed and well-aligned fibers that maintain the structural integrity of the yarn.

The SEM micrographs in

Figure 3 clearly demonstrate the effect of CMC

ws sizing on the surface morphology and hairiness of cotton warp yarns. The unsized yarn exhibits a high degree of hairiness, characterized by numerous protruding and loosely bound fibers extending from the yarn surface, which can increase friction, abrasion, and the likelihood of yarn breakage during weaving. In contrast, the CMC

ws-sized yarn presents a markedly smoother and more compact surface, with most surface fibers firmly bound to the yarn body and aligned along the yarn axis. The pronounced reduction in protruding fibers indicates a significant decrease in yarn hairiness, attributed to the formation of a continuous and cohesive CMC

ws sizing film.

Due to the imperfect organization of fibrous elements, yarns inherently exhibit surface and structural defects, such as fiber ends, hooks, loops, gimlets, and neps. When subjected to mechanical stress, such as abrasion, these defects become more pronounced. Deformation leads to disruption of the sizing layer, fiber incoherence, and increased surface disturbance. The more intense the mechanical stress, the greater the disorganization of the fiber arrangement, ultimately resulting in the breakdown of the cohesion function and a corresponding increase in disturbance. This surface disturbance is quantitatively measured using a pilosimeter, which assesses yarn hairiness.

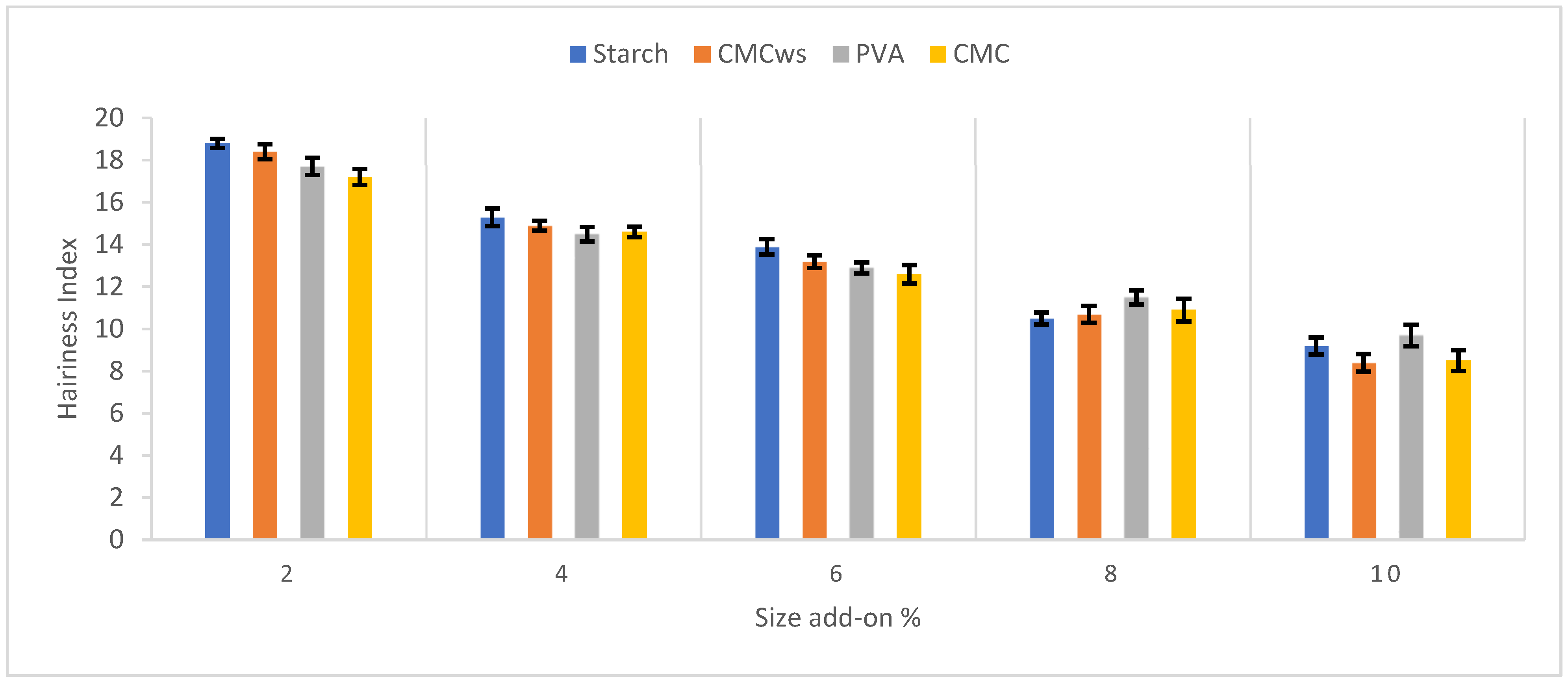

As illustrated in

Figure 4, yarn hairiness significantly decreases following sizing, regardless of the sizing material used (starch, PVA, CMC, or wheat-straw-derived CMC

ws). This reduction in hairiness enhances the physical performance of the yarn, particularly under weaving conditions. However, with prolonged mechanical stress, the disturbance function increases due to gradual degradation of the sizing film. Nonetheless, maintaining the smoothness of the yarn surface and preserving the cohesive interface of the external fiber layer is essential for sustaining yarn performance during the weaving process.

For CMC

ws-sized warp yarn, hairiness was reduced from 18.4 to 8.4, representing an approximate 54.35% reduction compared to the initial value at 2% size add-on. When comparing all types of samples, the greatest effect of “Size Add-on” on yarn hairiness was observed in the post-sizing values: 51.06% reduction for Starch, 54.34% for CMC

ws, 45.19% for PVA, and 50.58% for CMC. The overall percentage reductions in yarn hairiness between 2% and 10% size add-on levels are summarized in

Table 9, where the rankings of the agents are also identified. Different size add-ons were achieved by varying pickup percentage through adjustments in squeezing pressure. Among the tested agents, the low-cost CMC

ws showed a consistently higher reduction rate in yarn hairiness when compared to the commonly used sizing agents. Overall, CMC

ws proved to be an effective and economical sizing agent with strong performance (

Figure 4).

Table 10 presents linear regression results obtained using Minitab

® 22 at a 95% confidence level. The analysis indicates that CMC

ws exhibits the strongest and most reliable performance among the evaluated sizing agents. The CMC

ws model shows a very high coefficient of determination (R

2 = 98.95%) with a closely corresponding adjusted R

2 (98.59%), demonstrating excellent explanatory power and model stability. In addition, the high F-value (281.56) and highly significant

p-value (

p < 0.001) confirm the strong influence of the studied factor on the response variable.

Compared with CMC, starch, and PVA, CMCws achieved the highest R2 and F-value, indicating a more consistent and predictable effect on yarn performance. These results suggest that CMCws forms an effective and uniform sizing film, resulting in reliable enhancement of yarn properties. Consequently, CMCws can be regarded as a highly effective sizing agent with excellent reproducibility.

3.5. Abrasion Properties of CMCws-Sized Warp Yarns

The surface properties of woven fabrics directly reflect the performance of the yarns from which they are made. In this study, fabrics were produced from sized warp yarns, and their abrasion resistance behavior was evaluated. Therefore, fabric-level measurements serve as quantitative indicators of warp yarn durability and protection, providing a realistic assessment of yarn behavior under actual weaving conditions [

29].

The difference in the number of abrasion cycles to failure between fabrics containing unsized yarns and those containing sized yarns is substantial, indicating that fabrics made from unsized yarns contain regions that are insufficiently protected and therefore mechanically weaker. These vulnerable regions are particularly susceptible to damage as the yarn passes through weaving elements such as drop wires, heald frames, and the reed. The relatively low number of abrasion cycles required to break unsized yarns clearly demonstrates that sizing treatment significantly enhances abrasion resistance.

Sized yarns require a greater number of abrasion strokes before the development of hairiness compared with unsized yarns. In unsized yarns, fibers are loosely arranged, whereas in sized yarns the fibers are bound together by the sizing agent. Fiber loosening begins only after the sizing film is disrupted by the repeated flexing action of the abrasion pins. As illustrated in

Table 11, at low size add-on levels, the sizing skeleton breaks down rapidly after a limited number of abrasion strokes, resulting in lower abrasion resistance. In contrast, higher size add-on levels delay the breakdown of the sizing film, leading to improved abrasion resistance.

The apparent viscosity of CMC

ws solutions (903.03 cP) critically influences the properties of sizing films on cotton yarns. Higher viscosity, associated with increased polymer concentration, molecular weight, and DS (1.23), promotes greater size pick-up, forming thicker and more cohesive films that enhance mechanical protection, reduce fiber hairiness, and minimize breakage. Excessively high viscosity or DS, however, can produce stiffer films with reduced flexibility, potentially increasing brittleness [

30].

Abrasion resistance increased progressively with increasing size add-on for all sizing agents, reflecting enhanced surface protection and improved fiber cohesion due to greater size deposition. Among the evaluated agents, PVA exhibited the highest abrasion resistance gain (37.50%), followed closely by CMCws (37.14%), indicating their superior film-forming properties and strong adhesion to the yarn surface. CMC showed a moderate improvement (31.20%), while starch produced the lowest gain (28.33%), suggesting comparatively weaker resistance to surface wear.

The CV% values (12.24–13.35%) indicate moderate variability and confirm acceptable experimental consistency. Notably, CMCws achieved abrasion resistance gains comparable to PVA while maintaining reasonable variability, highlighting its potential as an effective alternative sizing agent.

The regression results in

Table 12, confirm that CMC

ws is an effective sizing agent, as evidenced by the high coefficient of determination (R

2 = 96.61%) and statistically significant model (

p < 0.001). The strong F-value indicates a pronounced effect of the studied factor on the response variable, while the close agreement between R

2 and adjusted R

2 reflects good model stability and reliable experimental behavior. Moreover, the consistently high performance of CMC

ws in improving mechanical properties, combined with acceptable variability, demonstrates its ability to form a uniform and durable sizing film. These findings support the suitability of CMC

ws as a reliable and efficient sizing agent, offering performance comparable to conventional agents.

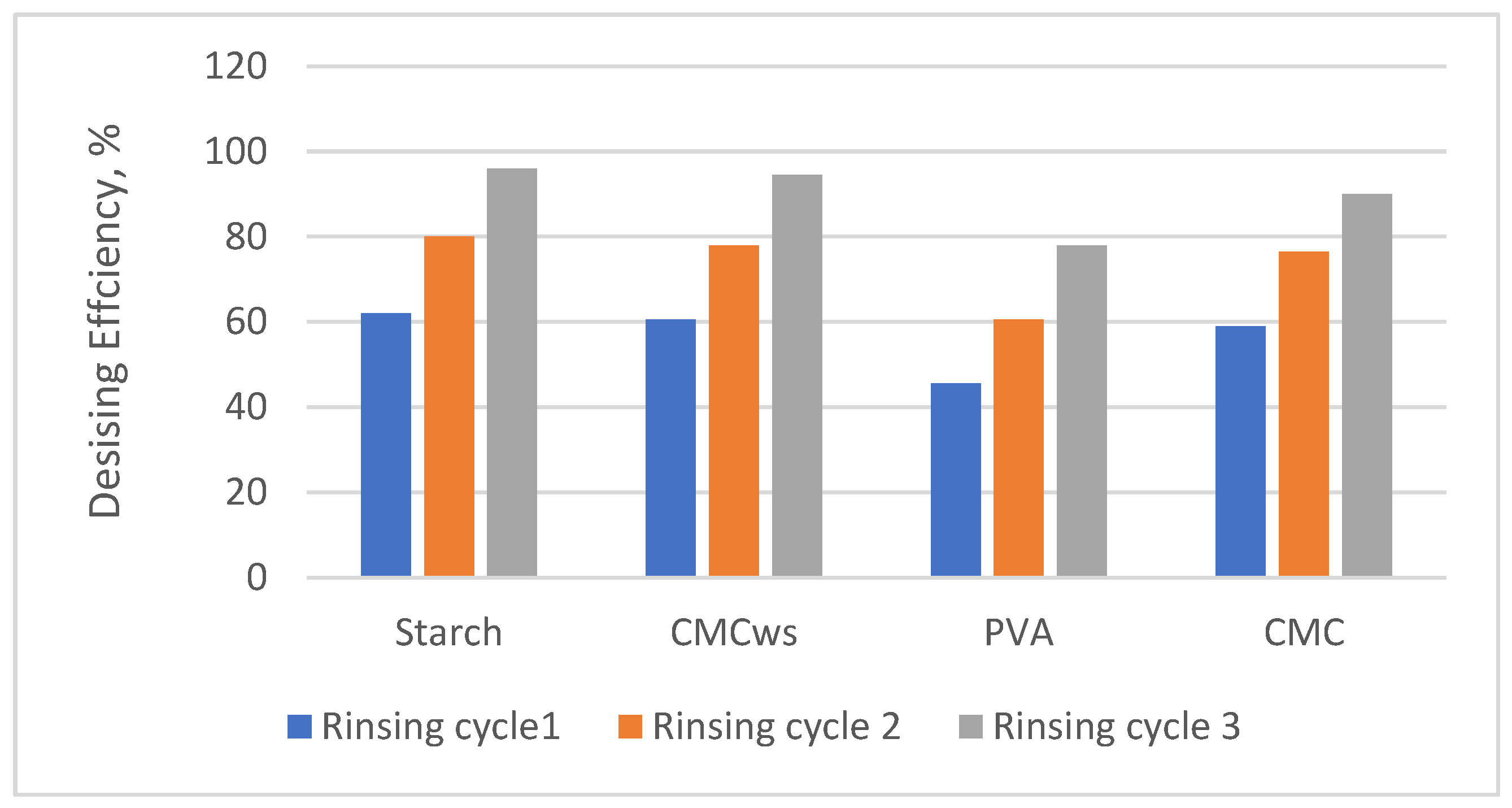

3.6. Desizing Efficiency of CMCws-Sized Warp Yarns

After weaving, the removal of sizing agents from fabrics is essential to ensure optimal dyeing and finishing quality. Therefore, good desizability is a critical property for textile sizing materials. The desizing efficiencies of sized cotton fabrics with different size recipes were shown in

Figure 5. It could be seen clearly that the desizing efficiency was important, no matter what the used size recipe was employed. It is well established that the desizing efficiency of sizing agents is influenced by the viscosity of the size solution, the moisture regain of the size film, and the water solubility of the film. Increasing DS generally improves desizing efficiency due to enhanced solubility, but excessive DS can slightly compromise film mechanical integrity, requiring careful optimization for practical textile processing [

17,

27]. Undoubtedly, the hydrophilic character of the CMC

ws sizing agent accelerates the diffusion of chemicals into size material, which promotes the degradation and the removal of the size from the sized fabric. These data prove that the desizing efficiency of CMC

ws-sized warp yarn exceeds 94%, indicating that CMCws-based sizes exhibit excellent ease of desizing.

Several studies have reported the use of various waxes for the development of super-hydrophobic surfaces and coatings [

20]. In the context of CMC

ws-based sizing, incorporating hydrophobic additives can create diffusion barriers, potentially affecting solution penetration, while the inherent hydrophilic nature of cotton fibers and CMC

ws films is largely maintained. This aligns with our desizing results, which show that hot-water desizing efficiently removes the CMC

ws sizing layer and preserves sufficient wettability, ensuring that the fabrics remain ready for subsequent treatments such as dyeing or finishing.

As shown in

Table 13, the BOD

5/COD ratio of the CMC

ws sizing agent reached approximately 0.50, indicating excellent biodegradability and effective microbial degradation. The efficient desizing behavior combined with the favorable degradation characteristics of the green CMC

ws developed in this study highlights its strong potential as a sustainable and environmentally friendly textile sizing agent. Nevertheless, while the reported BOD

5/COD ratio confirms that CMC

ws is readily biodegradable under controlled laboratory conditions, its behavior in real wastewater systems may be influenced by variations in organic load, microbial community structure and activity, as well as environmental parameters such as pH and temperature [

31,

32].

In contrast, the PVA sizing agent exhibited a much lower BOD

5/COD ratio of approximately 0.20, confirming its limited biodegradability and persistence in aqueous environments. Although conventional polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is characterized by a relatively low biodegradation rate, leading to poor biodegradability indicators, recent studies have demonstrated that modified, blended, or partially hydrolyzed PVA formulations can significantly improve biodegradability, while simultaneously enhancing water solubility and microbial degradation [

33].

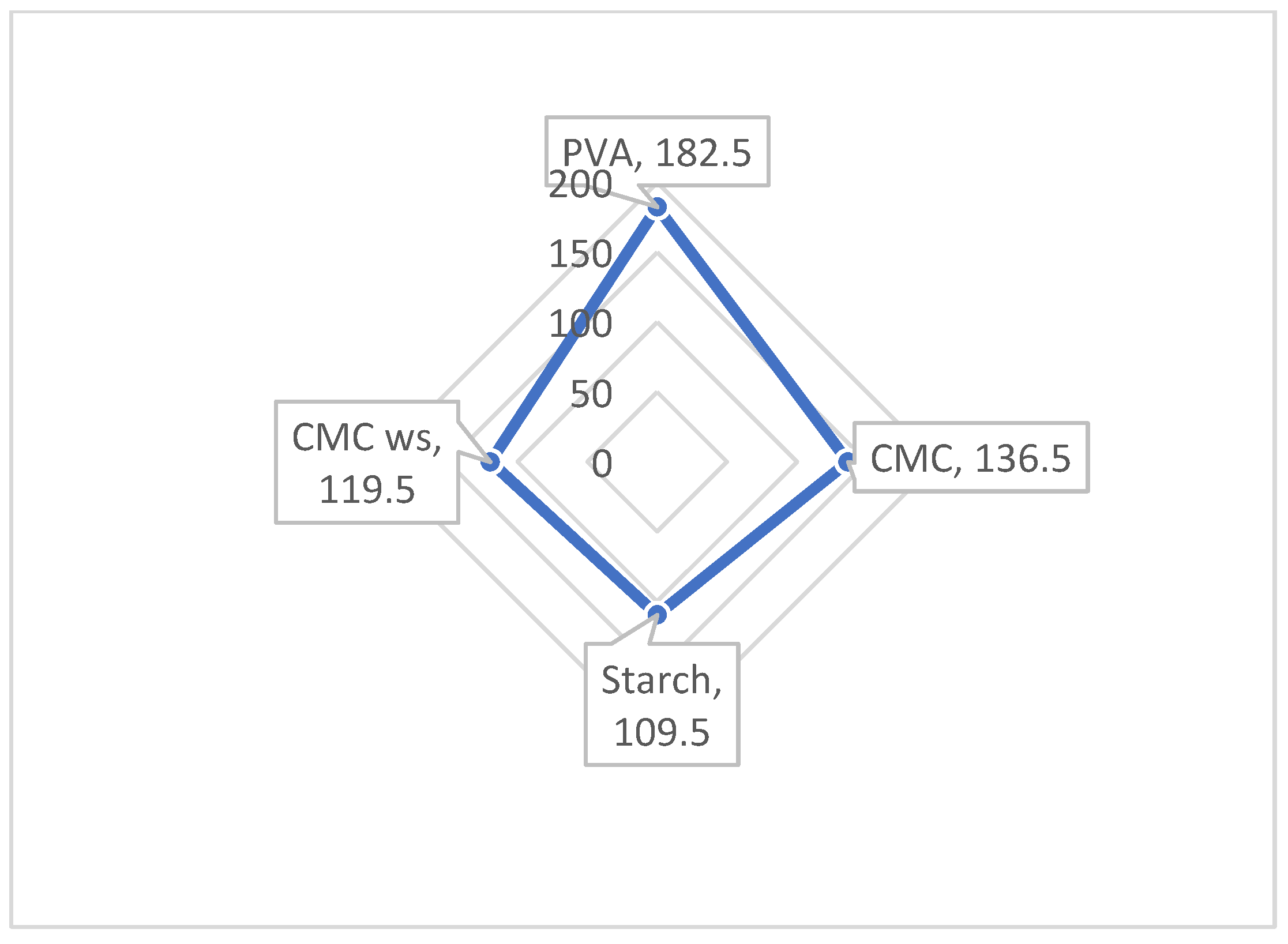

3.7. Evaluation of Cost-Effectiveness

A comparative cost analysis of various sizing agents for 500 L solution volumes is presented in

Figure 6. This evaluation is crucial for assessing the industrial viability of carboxymethyl cellulose derived from wheat straw (CMC

ws) as a sustainable alternative.

As shown in

Table 14, the cost price of each size formulation was determined by summing the individual costs of all components used in the recipe, including the primary sizing agents and auxiliary additives. The calculation considered the quantity of each compound in the formulation, expressed in grams per liter (g/L), and its corresponding market price per kilogram. For each ingredient, the total cost was obtained by multiplying its mass (converted to kilograms for the total batch volume) by its unit cost.

The results clearly demonstrate the economic advantage of CMCws-based sizing formulations. Specifically, the cost of a conventional polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based sizing agent for 500 L is approximately US$182.5, whereas the CMCws-based formulation incurs a lower cost of US$119.5. This indicates that the use of CMCws can lead to a substantial reduction in material costs. Therefore, CMCws emerges as a cost-effective and competitive alternative to traditional sizing agents widely used in the industry.