Facile Fabrication of Attapulgite-Modified Chitosan Composite Aerogels with Enhanced Mechanical Strength and Flame Retardancy for Thermal Insulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Acid Activation of Attapulgite

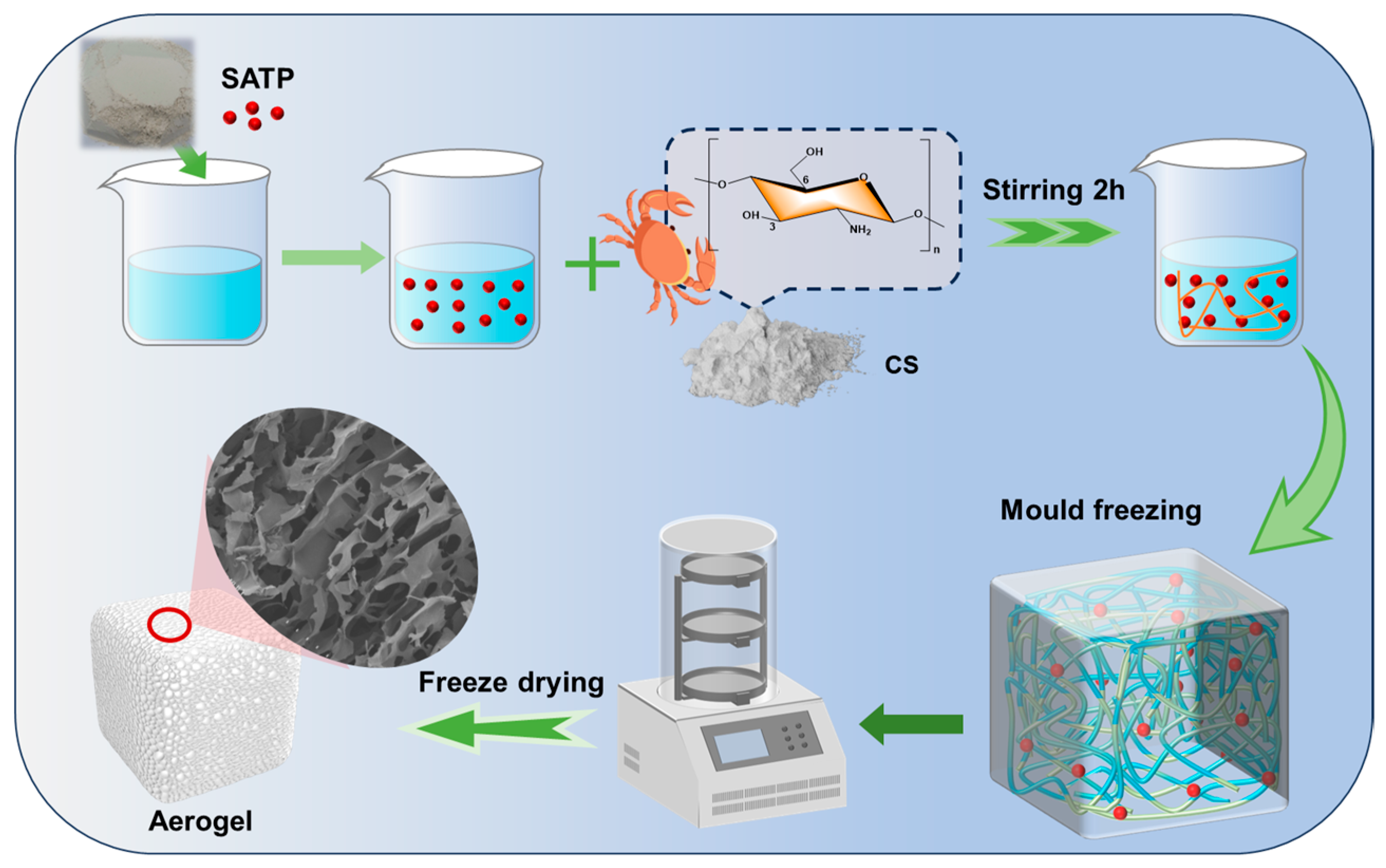

2.2.2. Preparation of CS-SATP Composite Aerogels

2.3. Characterization Methods

3. Results

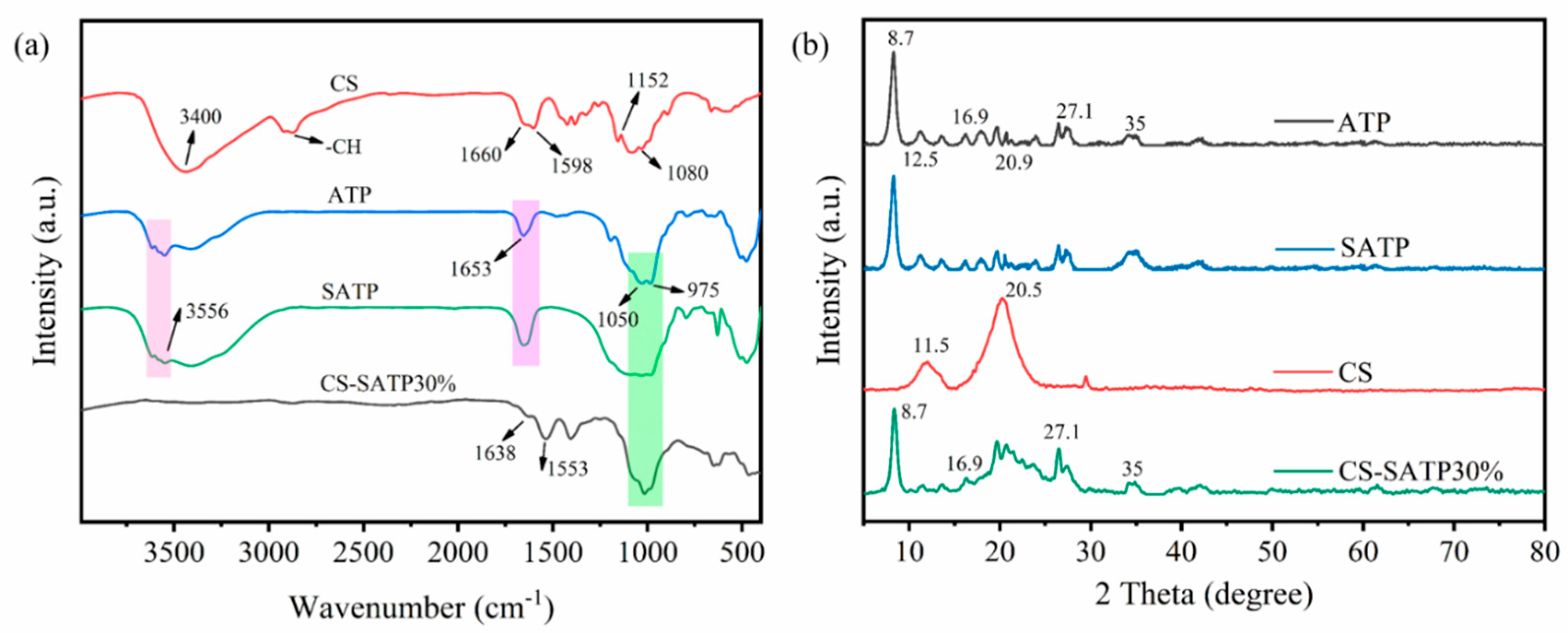

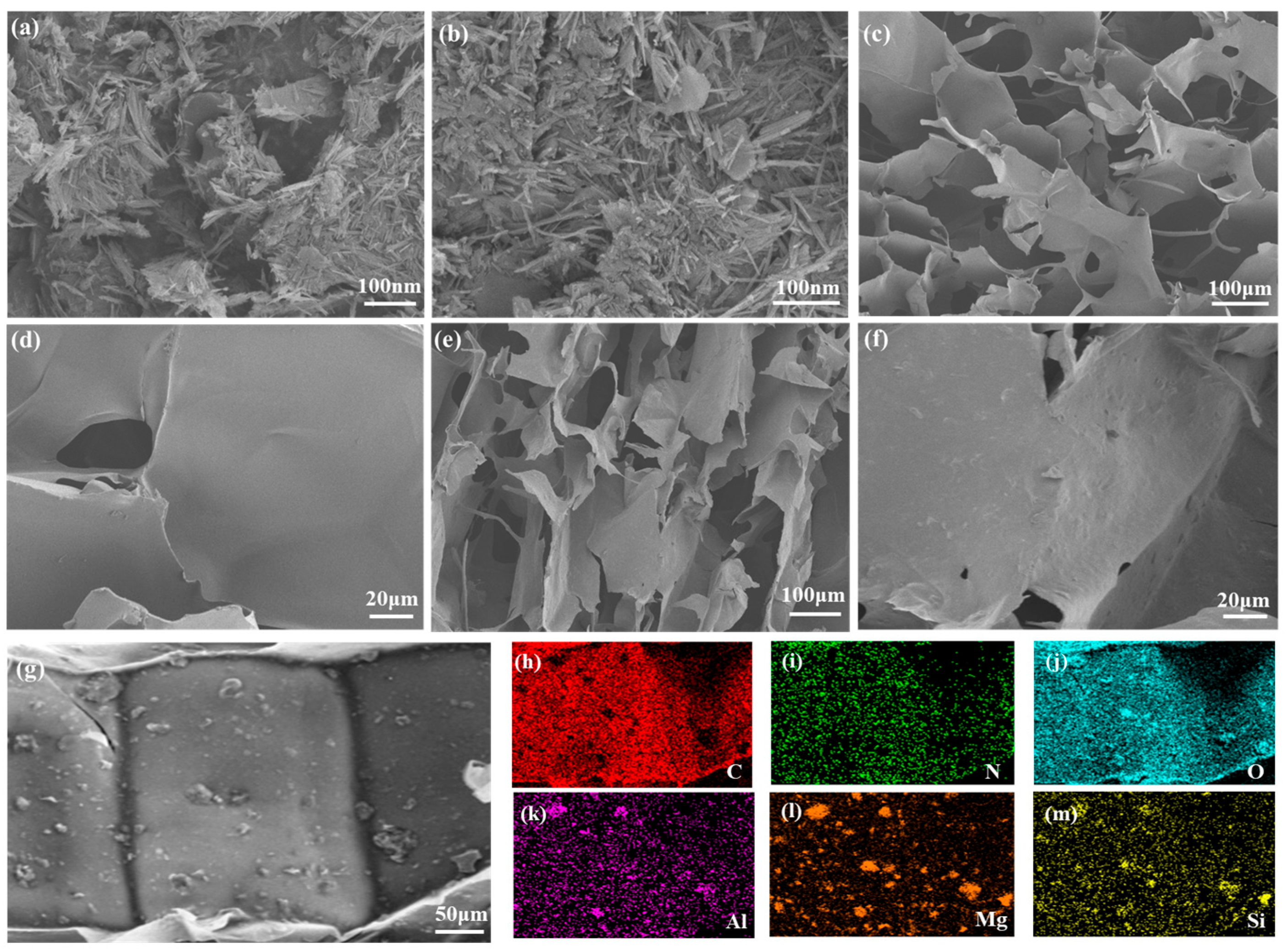

3.1. Structural and Morphological Characterization

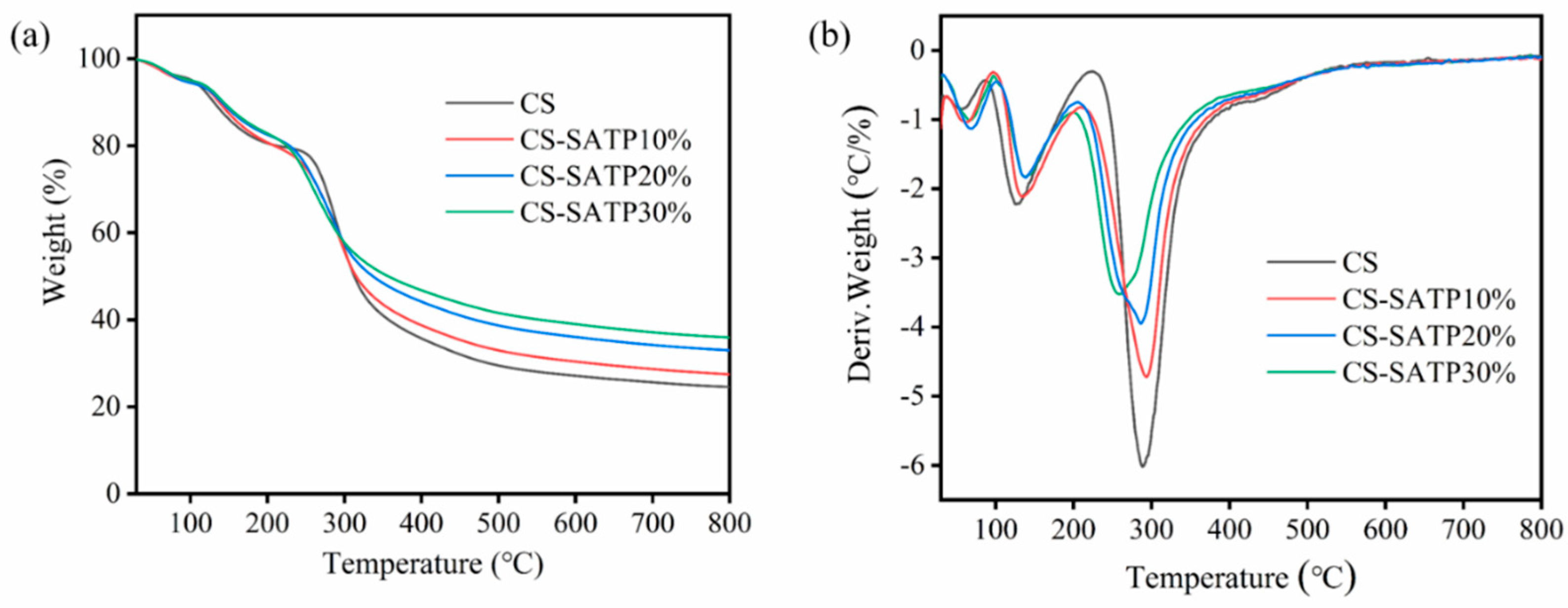

3.2. Thermal Stability Analysis

3.3. Flame Retardancy Analysis

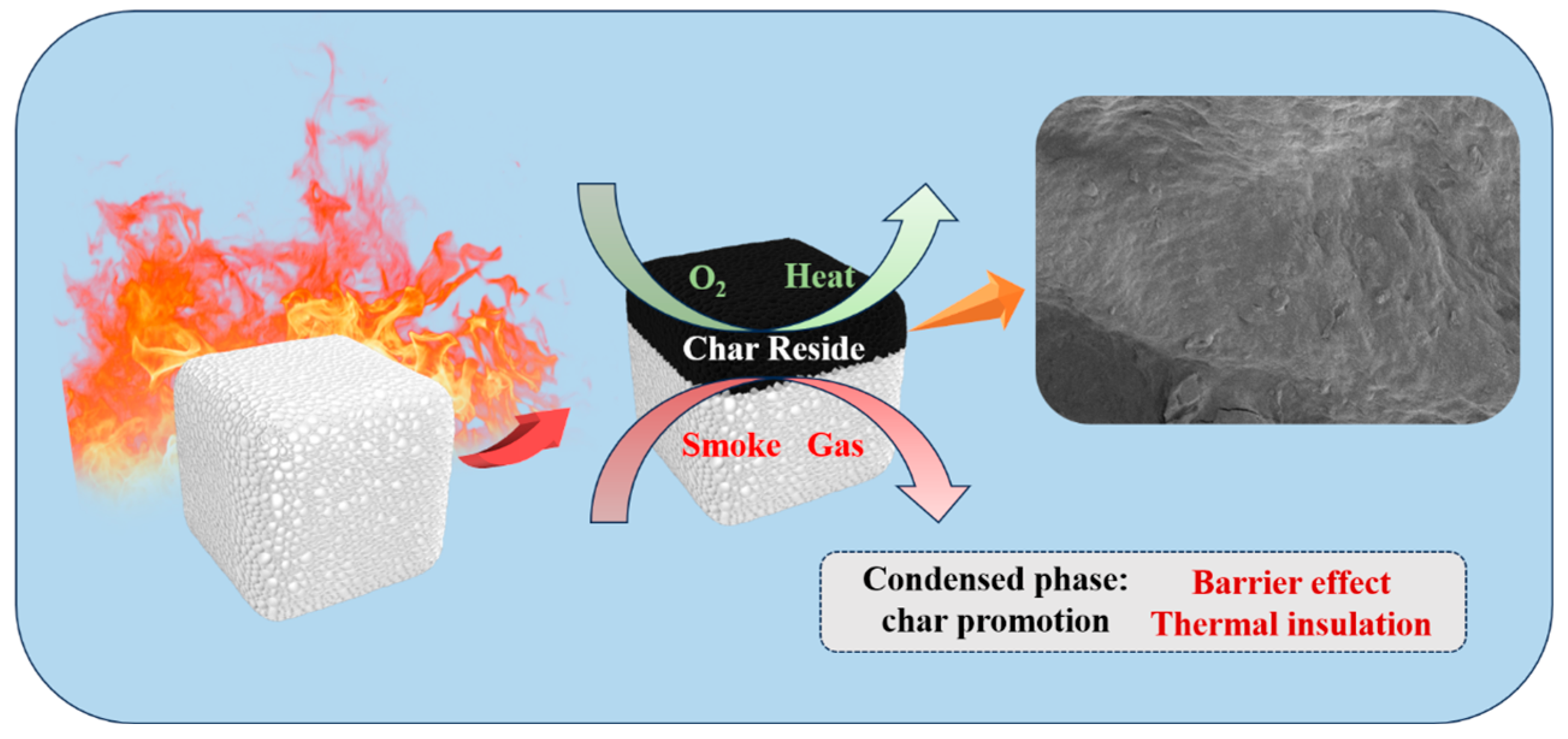

3.4. Flame Retardant Mechanism Analysis

3.5. Thermal Insulation Performance Analysis

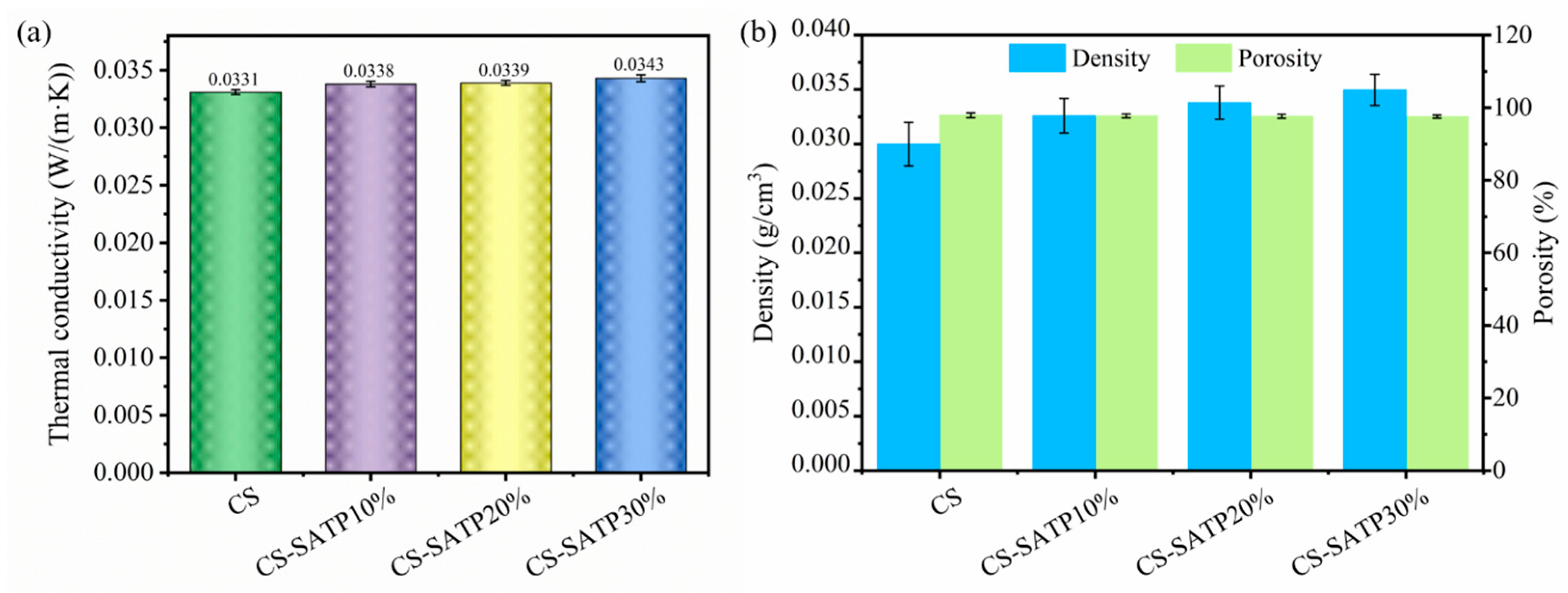

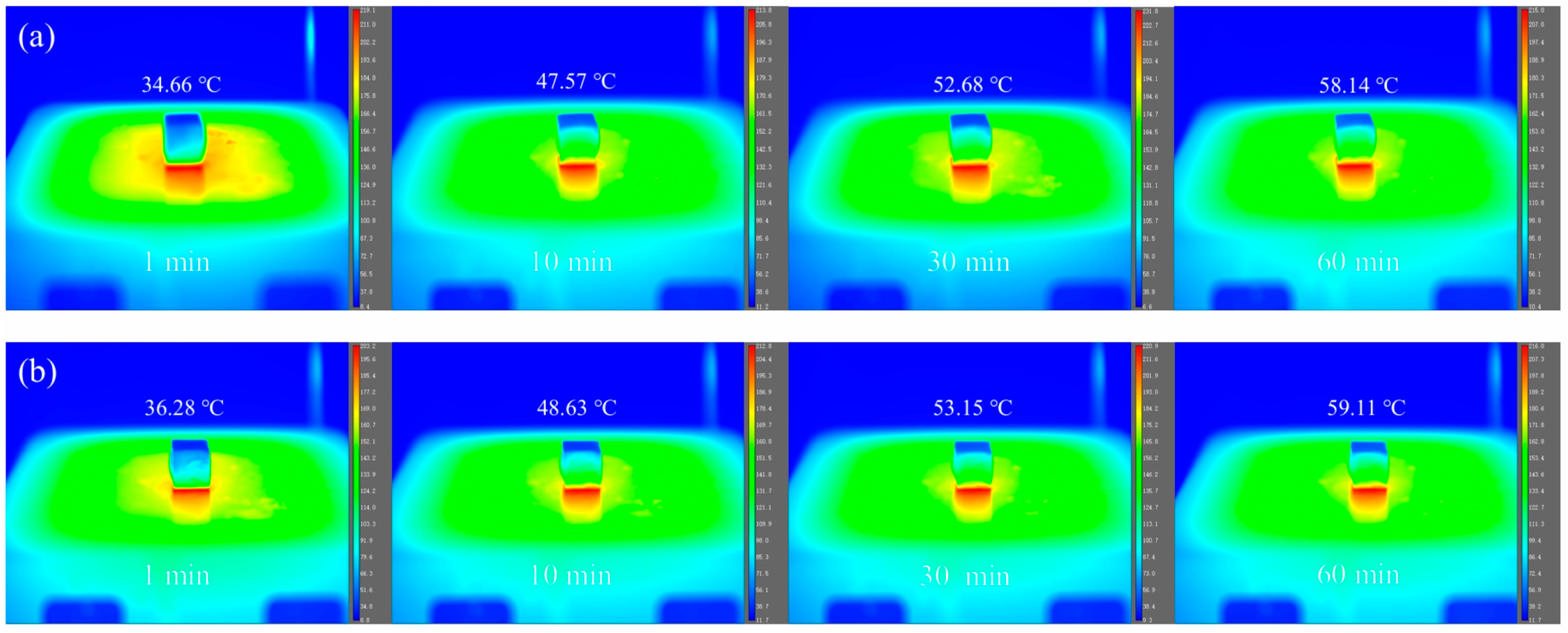

3.6. Mechanical Property Analysis

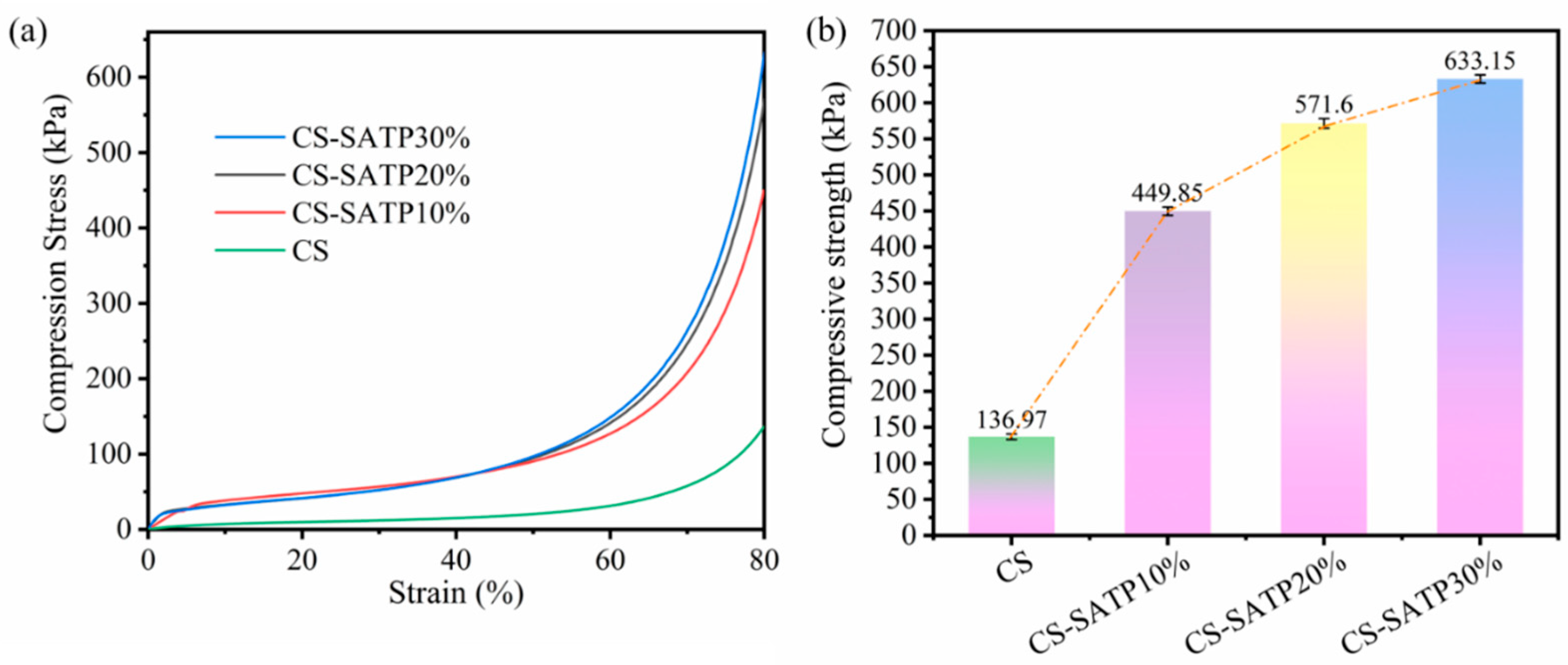

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CS | Chitosan |

| ATP | Attapulgite |

| SATP | Acidified attapulgite |

| THR | Total heat release |

| TTI | Time to ignition |

| FIGRA | Fire growth rate index |

| PHRR | Peak heat release rate |

| TpHRR | Time to peak heat release rate |

| LOI | Limiting oxygen index |

| DI | Deionized water |

| SEM | Electron microscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| EDS | Energy-dispersive spectroscopy |

| FT-IR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| UL-94 | Vertical burning test |

| CONE | Cone calorimetry |

| Raman | Raman spectroscopy |

References

- Jiang, Z.; Lin, B. China’s Energy Demand and Its Characteristics in the Industrialization and Urbanization Process. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Effects of Urbanisation on Energy Consumption in China. Energy Policy 2014, 65, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.-L.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Wang, B. The Impact of Urbanization on Residential Energy Consumption in China: An Aggregated and Disaggregated Analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, L.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Rismanchi, B.; Ng, H.M.; Hasan, M.H.; Metselaar, H.S.C.; Muraza, O.; Aditiya, H.B. A Review on Insulation Materials for Energy Conservation in Buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; Cao, Y.; Guro, V.P.; Li, Y. Silica–Chitosan Composite Aerogels for Thermal Insulation and Adsorption. Crystals 2023, 13, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, H.; Masoud Salehi, A.; Mehraein, M.; Asadollahfardi, G. The Effects of Steel, Polypropylene, and High-Performance Macro Polypropylene Fibers on Mechanical Properties and Durability of High-Strength Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 386, 131589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Gu, X. A Sustainable Lignin-Based Epoxy Resin: Its Preparation and Combustion Behaviors. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 192, 116151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhao, H.; Qiang, X.; Ouyang, C.; Wang, Z.; Huang, D. Facile Construction of Agar-Based Fire-Resistant Aerogels: A Synergistic Strategy via in Situ Generations of Magnesium Hydroxide and Cross-Linked Ca-Alginate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 227, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, N.; Guo, X.; Zhao, L.; Yin, Y. Anisotropic Composite Aerogel with Thermal Insulation and Flame Retardancy from Cellulose Nanofibers, Calcium Alginate and Boric Acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Singh, S.; Dev, K.; Chhajed, M.; Maji, P.K. Harnessing the Flexibility of Lightweight Cellulose Nanofiber Composite Aerogels for Superior Thermal Insulation and Fire Protection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 18075–18089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy-Mendes, A.; Pontinha, A.D.R.; Alves, P.; Santos, P.; Durães, L. Progress in Silica Aerogel-Containing Materials for Buildings’ Thermal Insulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 286, 122815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Guo, Z. Natural Polysaccharide-Based Aerogels and Their Applications in Oil–Water Separations: A Review. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 8129–8158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; He, B.; An, Z.; Xiao, W.; Song, X.; Yan, K.; Zhang, J. Hollow Glass Microspheres Embedded in Porous Network of Chitosan Aerogel Used for Thermal Insulation and Flame Retardant Materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, S.; Lu, K.; Wang, M.; Xiao, Y.; Ding, F. Microstructural Evolution of Bio-Based Chitosan Aerogels for Thermal Insulator with Superior Moisture/Fatigue Resistance and Anti-Thermal-Shock. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Liu, B.-W.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Z.-C.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.-B.; Wang, Y.-Z. Fully Biomass-Based Aerogels with Ultrahigh Mechanical Modulus, Enhanced Flame Retardancy, and Great Thermal Insulation Applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 225, 109309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Wang, P.; Song, X.; Liao, B.; Yan, K.; Zhang, J.-J. Facile Fabrication of Anisotropic Chitosan Aerogel with Hydrophobicity and Thermal Superinsulation for Advanced Thermal Management. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 9348–9357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Dunn, E.T.; Grandmaison, E.W.; Goosen, M.F.A. Applications and Properties of Chitosan. In Applications of Chitan and Chitosan; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aranaz, I.; Alcántara, A.R.; Civera, M.C.; Arias, C.; Elorza, B.; Heras Caballero, A.; Acosta, N. Chitosan: An Overview of Its Properties and Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Wu, N.; Ma, X.; Niu, F. Superior Intrinsic Flame-Retardant Phosphorylated Chitosan Aerogel as Fully Sustainable Thermal Insulation Bio-Based Material. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2023, 207, 110213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, Q.; Yang, D.; Wang, X.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Z.; Wei, H.; Cao, X.; et al. Flame Retardant Organic Aerogels: Strategies, Mechanism, and Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 157355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chu, Y.; Deng, C.; Xiao, H.; Wu, W. High-Strength and Superamphiphobic Chitosan-Based Aerogels for Thermal Insulation and Flame Retardant Applications. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 651, 129663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jin, Z.; Shao, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, M.; Fu, B. Facile Fabrication of Bio-Based PAG-Modified Chitosan Aerogels for Enhanced Thermal Insulation and Flame-Retardant Performance. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2026, 732, 139159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatinia, Z.; Jalali, A.M. Chitosan-Based Hydrogels: Preparation, Properties and Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 194–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Diao, J.; Li, X.; Yue, D.; He, G.; Jiang, X.; Li, P. Hydrogel-Based 3D Printing Technology: From Interfacial Engineering to Precision Medicine. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 341, 103481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.-F.; Yao, J. Highly Conductive and Anti-Freezing Cellulose Hydrogel for Flexible Sensors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 230, 123425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhao, F.; Xiong, R.; Peng, T.; Ma, Y.; Hu, J.; Xie, L.; Jiang, C. Thermal Insulation and Flame Retardancy of Attapulgite Reinforced Gelatin-Based Composite Aerogel with Enhanced Strength Properties. Compos. Part Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 138, 106040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cao, H.; Huang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Ye, S.; Li, Y.; Hua, Y.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, Y. Robust Cellulose/Clay Composite Aerogels with Frame-Wall like Structure for Superior Thermal Insulation and Flame Retardancy. Compos. Part B Eng. 2026, 309, 113098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotti, A.; Baldino, L.; Iervolino, G.; Cardea, S.; Reverchon, E. Chitosan Aerogel Beads Production by Supercritical Gel Drying, and Their Application to Methylene Blue Adsorption. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2025, 226, 106731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merillas, B.; Lamy-Mendes, A.; Villafañe, F.; Durães, L.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.Á. Polyurethane Foam Scaffold for Silica Aerogels: Effect of Cell Size on the Mechanical Properties and Thermal Insulation. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 26, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Feng, Y.; Xu, F.; Chen, F.-F.; Yu, Y. Smart Fire Alarm Systems for Rapid Early Fire Warning: Advances and Challenges. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 137927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Han, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, S. Multi-Functional Bio-Film Based on Sisal Cellulose Nanofibres and Carboxymethyl Chitosan with Flame Retardancy, Water Resistance, and Self-Cleaning for Fire Alarm Sensors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Li, T.; Zhong, F.; Wen, S.; Zheng, G.; Gong, C.; Qin, C.; Liu, H. Preparation and Properties of Chitosan/Acidified Attapulgite Composite Proton Exchange Membranes for Fuel Cell Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 49079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudriche, L.; Calvet, R.; Hamdi, B.; Balard, H. Effect of Acid Treatment on Surface Properties Evolution of Attapulgite Clay: An Application of Inverse Gas Chromatography. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 392, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Wang, R.; Wang, C.; Jia, J.; Sun, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, A. Facile Preparation of Attapulgite-based Aerogels with Excellent Flame Retardancy and Better Thermal Insulation Properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, M. Synthesis of Phytic Acid-Modified Chitosan and the Research of the Corrosion Inhibition and Antibacterial Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stani, C.; Vaccari, L.; Mitri, E.; Birarda, G. FTIR Investigation of the Secondary Structure of Type I Collagen: New Insight into the Amide III Band. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 229, 118006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Liu, Q. Chemical Structure Analyses of Phosphorylated Chitosan. Carbohydr. Res. 2014, 386, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, J.; You, F.; Yao, C.; Yang, H.; Chen, R.; Yu, P. Chitosan/Clay Aerogel: Microstructural Evolution, Flame Resistance and Sound Absorption. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 228, 106624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Lyu, B.; Wang, P.; Ma, J. Nanocomposite Based on Poly(Acrylic Acid) / Attapulgite towards Flame Retardant of Cotton Fabrics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 206, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, N.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Yu, S.; Li, J. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan/Purified Attapulgite Composite for Sharp Adsorption of Humic Acid from Aqueous Solution at Low Temperature. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 78, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Guo, F.; Song, Z.; You, T.; Xue, K.; Zhao, L.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, M. Excellent Mechanical Strength and Satisfactory Thermal Stability of Polybenzoxazine Aerogels through Monomer Structure Optimization. Polymer 2024, 302, 127079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, P.; Guo, W.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X. Flame Retardant, Heat Insulating and Hydrophobic Chitosan-Derived Aerogels for the Clean-up of Hazardous Chemicals. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Jiang, C.; He, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhu, L.; Xie, L. Environment Friendly Biomass Composite Aerogel with Reinforced Mechanical Properties for Thermal Insulation and Flame Retardancy Application. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 4084–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Ding, S.; Zhu, L.; Wang, S. Preparation and Characterization of Flame-Retardant and Thermal Insulating Bio-Based Composite Aerogels. Energy Build. 2023, 278, 112656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, R.A.; Xu, Q.; Asante-Okyere, S.; Jin, C.; Bentum-Micah, G. Correlation Analysis of Cone Calorimetry and Microscale Combustion Calorimetry Experiments. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018, 136, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Chen, F.; Zhu, W.; Yan, N. Functionalized Lignin Nanoparticles for Producing Mechanically Strong and Tough Flame-Retardant Polyurethane Elastomers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 1339–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.-F.; Yao, J. Bimetallic MOF@bacterial Cellulose Derived Carbon Aerogel for Efficient Electromagnetic Wave Absorption. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 20951–20959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, G.-P.; Lin, Y. Tannic Acid as Cross-Linker and Flame Retardant for Preparation of Flame-Retardant Polyurethane Elastomers. React. Funct. Polym. 2022, 181, 105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Wang, X.; Yu, B.; Feng, X.; Mu, X.; Yuen, R.K.K.; Hu, Y. Flame-Retardant-Wrapped Polyphosphazene Nanotubes: A Novel Strategy for Enhancing the Flame Retardancy and Smoke Toxicity Suppression of Epoxy Resins. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 325, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Chen, S.; Yang, R.; Li, D.; Zhang, W. Fabrication of an Eco-Friendly Clay-Based Coating for Enhancing Flame Retardant and Mechanical Properties of Cotton Fabrics via LbL Assembly. Polymers 2022, 14, 4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Yuan, B.; Qi, C.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, S.; Wang, P.; Kong, Y.; Jin, H.; Mu, B. Multi-Stage Releasing Water: The Unique Decomposition Property Makes Attapulgite Function as an Unexpected Clay Mineral-Based Gas Source in Intumescent Flame Retardant. Compos. Part Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 178, 108014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, Z.; Xu, T. Improving the Controlled-Release Effects of Composite Flame Retardant by Loading on Porous Attapulgite and Coating. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 7871–7887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.K.; Ashish, D.K.; Rudžionis, Ž. Aerogel Based Thermal Insulating Cementitious Composites: A Review. Energy Build. 2021, 245, 111058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presel, F.; Paier, J.; Calaza, F.C.; Nilius, N.; Sterrer, M.; Freund, H.-J. Complexity of CO2 Activation and Reaction on Surfaces in Relation to Heterogeneous Catalysis: A Review and Perspective. Top. Catal. 2025, 68, 1828–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | CS (g) | ATP (g) | Deionized Water (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 1.6 | - | 100 |

| CS-SATP10% | 1.6 | 0.16 | 100 |

| CS-SATP20% | 1.6 | 0.32 | 100 |

| CS-SATP30% | 1.6 | 0.48 | 100 |

| Sample | Td10% (°C) | Td max (°C) | Cy800 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 130.40 | 288.34 | 24.41 |

| CS-SATP10% | 136.53 | 290.95 | 27.17 |

| CS-SATP20% | 140.23 | 286.15 | 32.77 |

| CS-SATP30% | 142.98 | 256.21 | 35.67 |

| Sample | LOI (%) | Dripping | t1/t2 (s) | UL-94 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 26.8 ± 0.3 | No | 13/48 | NR |

| CS-SATP10% | 29.4 ± 0.3 | No | 8/5 | V-0 |

| CS-SATP20% | 32.5 ± 0.2 | No | 6/3 | V-0 |

| CS-SATP30% | 34.0 ± 0.2 | No | 1/1 | V-0 |

| Sample | TTI (s) | THR (MJ/m2) | PHRR (kW/m2) | TpHRR (s) | SPR (m2/s) | TSP (m2) | FIGRA (kW/(m2·s)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 7 | 4.22 | 98.78 | 28 | 0.0868 | 0.103 | 3.53 |

| CS-SATP30% | 3 | 3.83 | 37.00 | 13 | 0.0297 | 0.047 | 2.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cheng, S.; Shao, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, C.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X.; Fu, B. Facile Fabrication of Attapulgite-Modified Chitosan Composite Aerogels with Enhanced Mechanical Strength and Flame Retardancy for Thermal Insulation. Polymers 2026, 18, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010098

Cheng S, Shao Y, Chen M, Wang C, Zhu X, Zhang X, Fu B. Facile Fabrication of Attapulgite-Modified Chitosan Composite Aerogels with Enhanced Mechanical Strength and Flame Retardancy for Thermal Insulation. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Siyuan, Yuwen Shao, Meisi Chen, Chenfei Wang, Xinbao Zhu, Xiongfei Zhang, and Bo Fu. 2026. "Facile Fabrication of Attapulgite-Modified Chitosan Composite Aerogels with Enhanced Mechanical Strength and Flame Retardancy for Thermal Insulation" Polymers 18, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010098

APA StyleCheng, S., Shao, Y., Chen, M., Wang, C., Zhu, X., Zhang, X., & Fu, B. (2026). Facile Fabrication of Attapulgite-Modified Chitosan Composite Aerogels with Enhanced Mechanical Strength and Flame Retardancy for Thermal Insulation. Polymers, 18(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010098