Functionalized Cellulose from Citrus Waste as a Sustainable Oil Adsorbent Material

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Mercerization of Cellulose

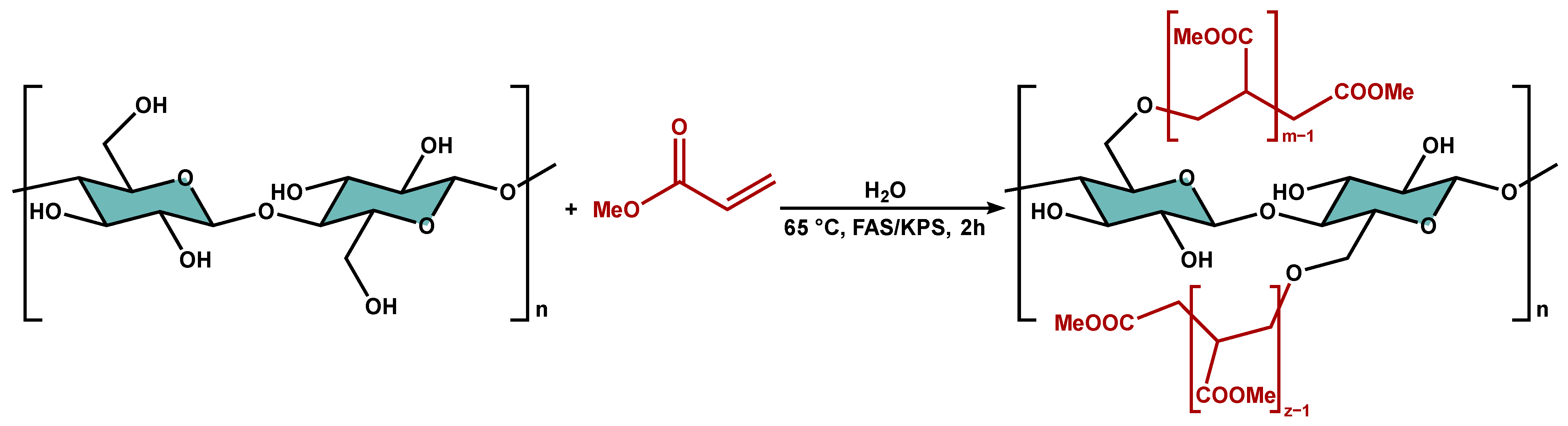

2.3. Graft Copolymerization of Cellulose

2.4. Sorption Capacity Test in Continuous Flow Using Fuel/Water System

2.5. Sorption Capacity Test in Batch Using Fuel/Water System

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Analysis

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

2.8. NMR Characterization of WC20 and PMA

2.9. Contact Angle Measurements

2.10. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Analysis (EIS)

3. Results and Discussion

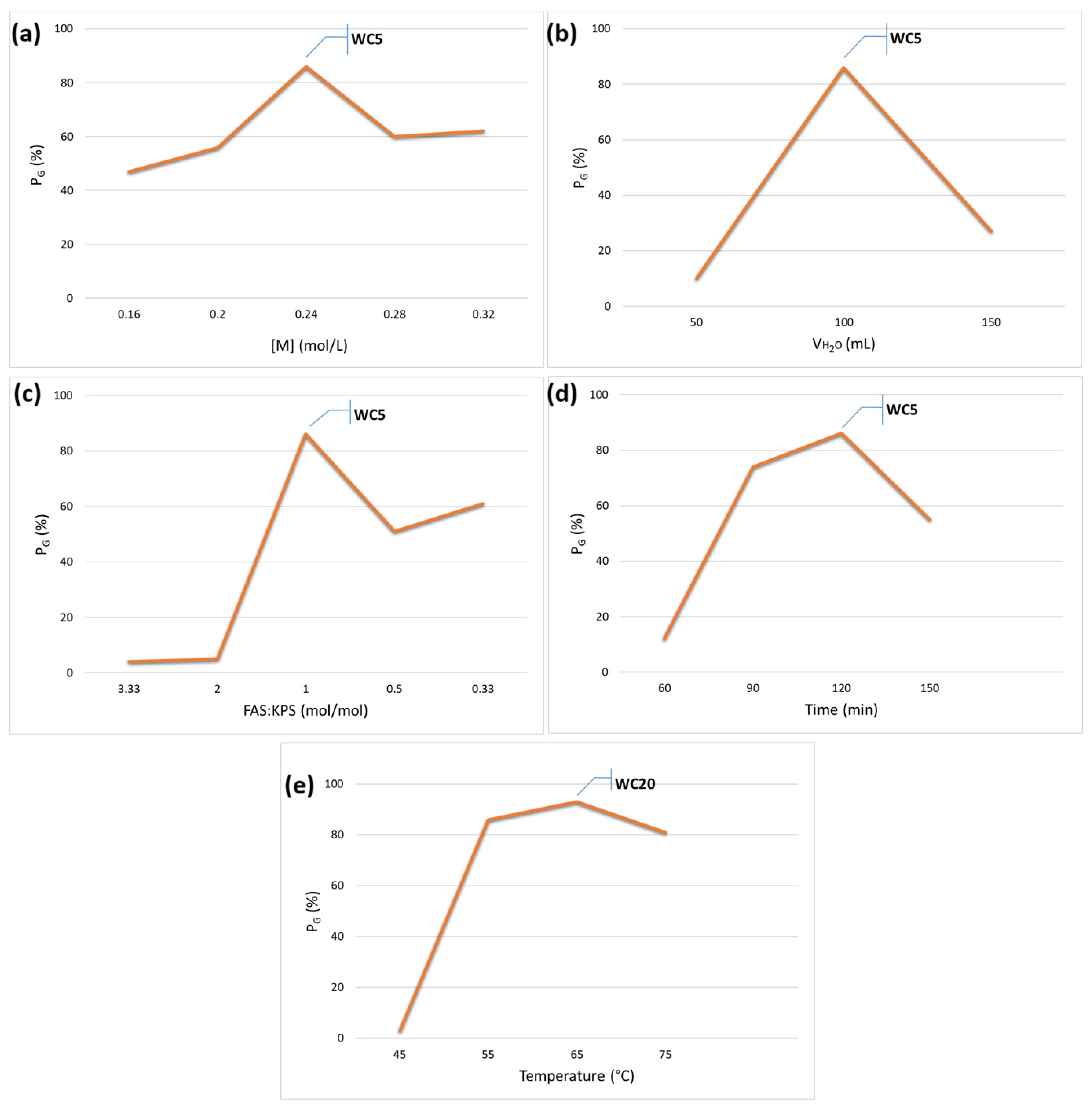

3.1. Graft Copolymerization onto Cellulose Fibers Derived from Citrus Peel Wastes

3.2. Characterization of Cellulose Copolymerized with Methyl Acrylate

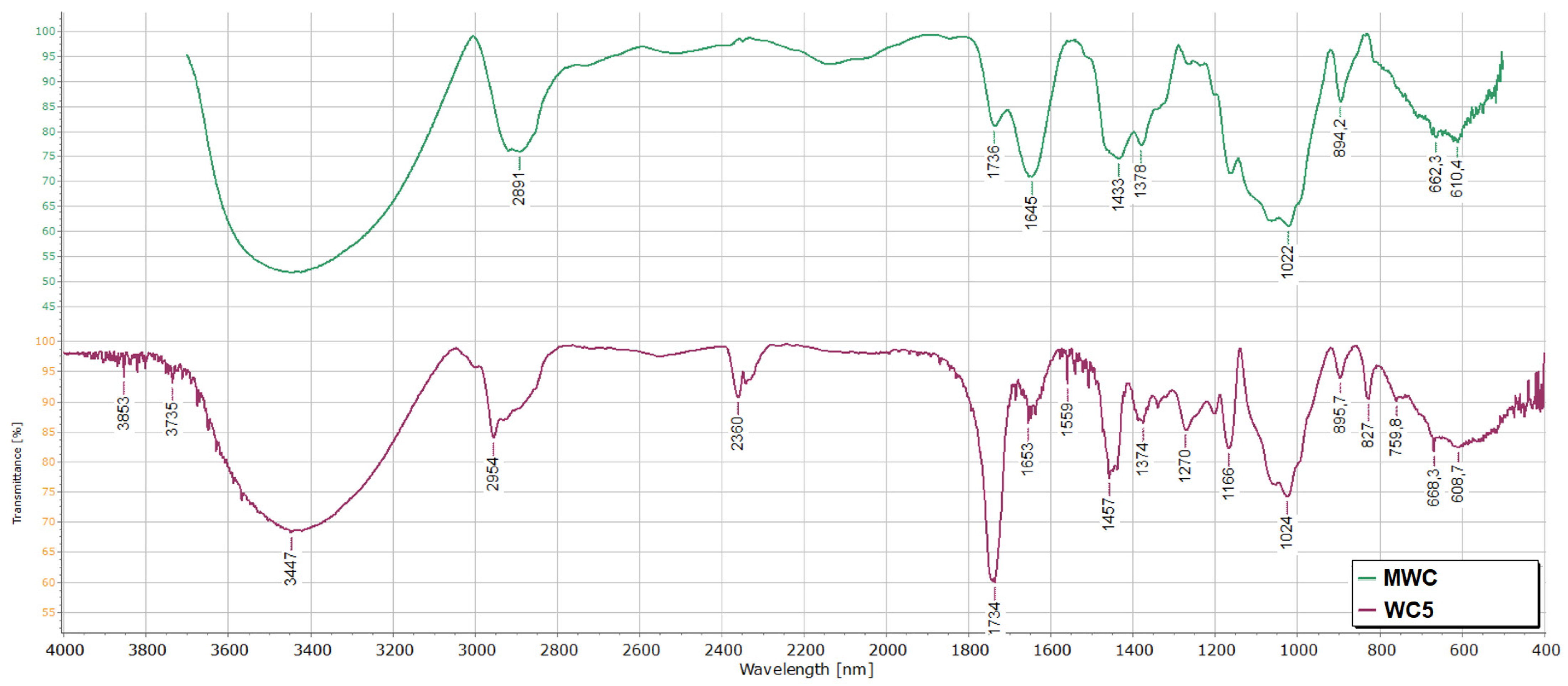

3.2.1. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR)

- (1)

- Both the MCC and the natural fiber spectra contain common signals due to the functional groups present in cellulose. The only significant peak that differentiates the two spectra is the one at 1740 cm−1, present exclusively in the spectrum of the natural fiber, and which is attributable to the C=O stretching of the hemicellulose (See Figure S1 in the Supplementary Materials).

- (2)

- The enhanced peak intensity near 894 cm−1, in the spectrum of MWC, indicates an increased amorphous content [42], resulting in greater hydroxyl group accessibility. Consequently, the mercerized fiber exhibits higher reactivity than the untreated cellulose, as grafting does not occur on the raw fiber. Furthermore, the peak at 1740 cm−1 is less intense than the native cellulose, suggesting that the pretreatment with NaOH solution helped to remove the hemicellulose components (see Figure S2 in the Supplementary Materials).

- (3)

- At higher PG (material WC5), the intensity of the peak at 1734 cm−1 increases markedly, reflecting a substantial rise in C=O ester group content (Figure 2). Additionally, grafting with PMA induces the appearance of a peak at 2954 cm−1, probably due to the stretching of CH2 and CH3 groups, and the presence of a weak band at 827 cm−1, likely associated with the CH2 group rocking vibrations of the grafted chains [43].

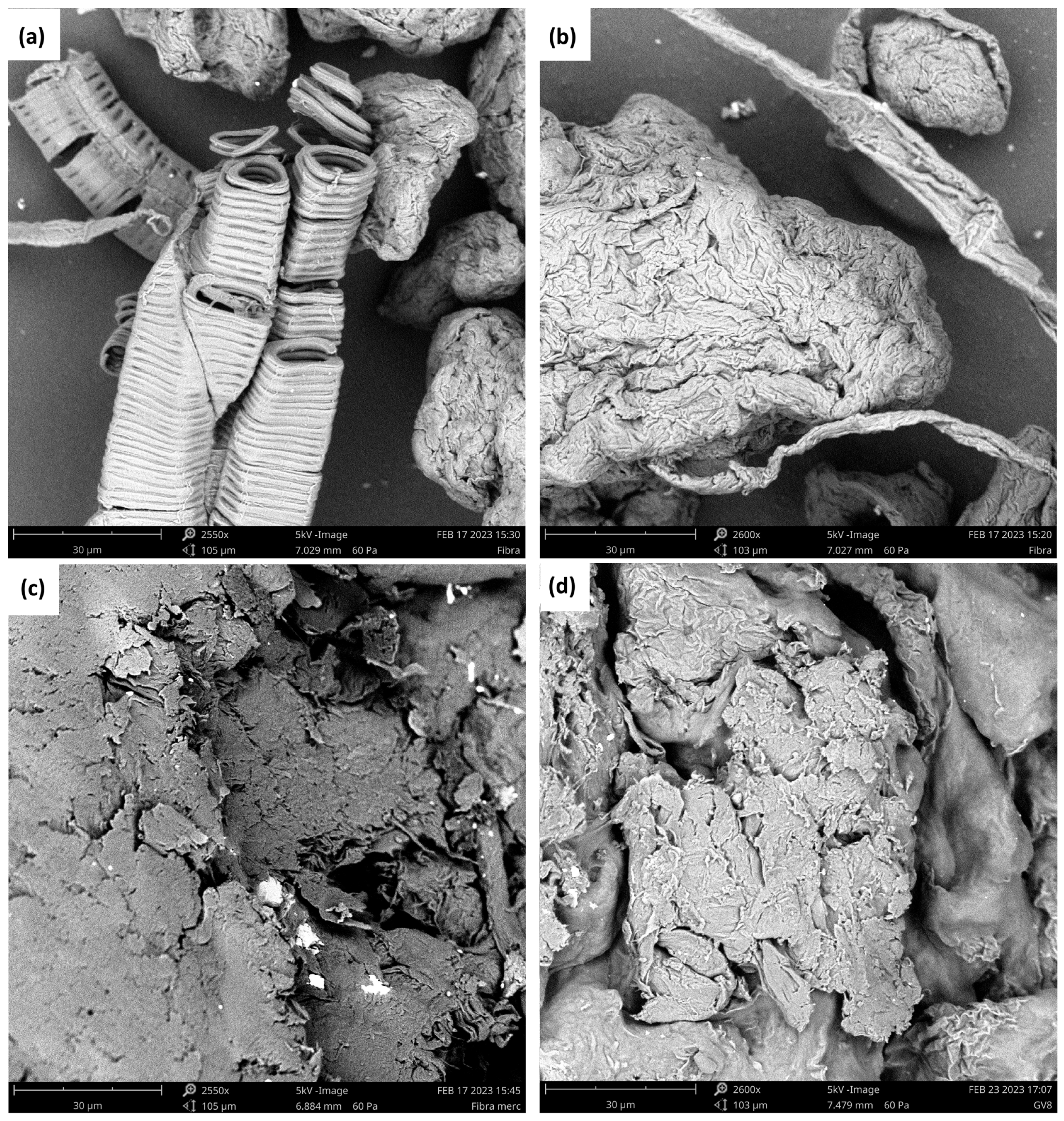

3.2.2. Morphological Analysis by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

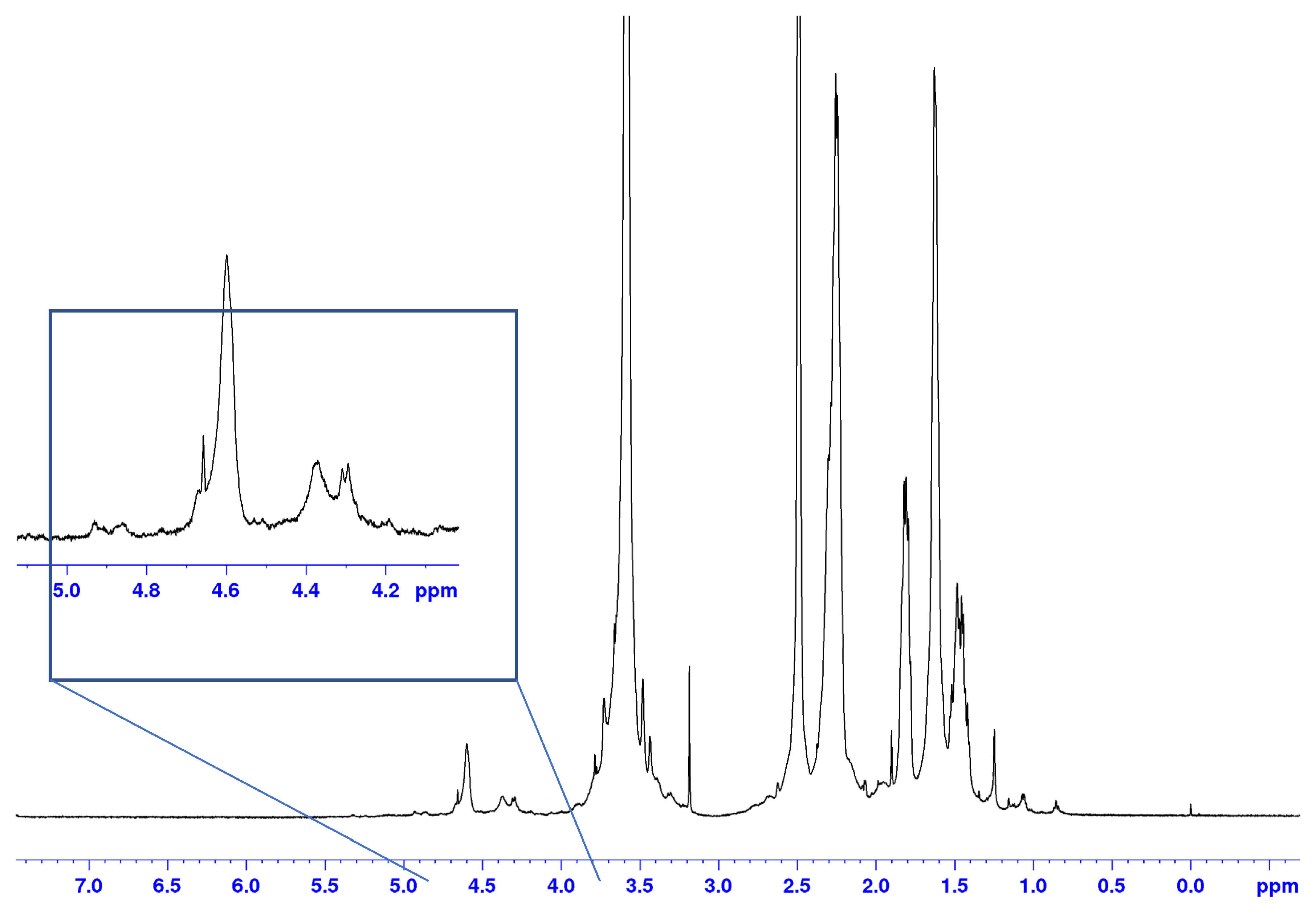

3.2.3. NMR Characterization of WC20 and PMA

3.2.4. Contact Angle Measurements

3.3. Adsorption Capacity Using Different Oil Phases

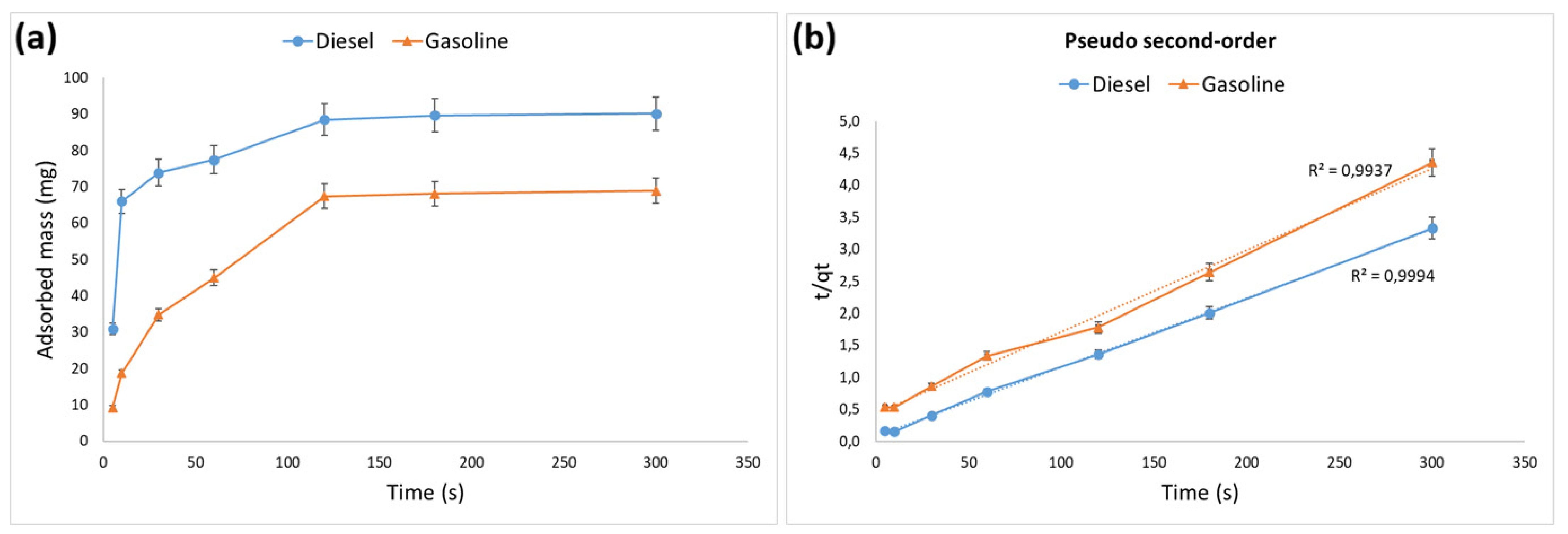

3.3.1. Sorption Kinetics of WC20 in Diesel/Water and Gasoline/Water Systems

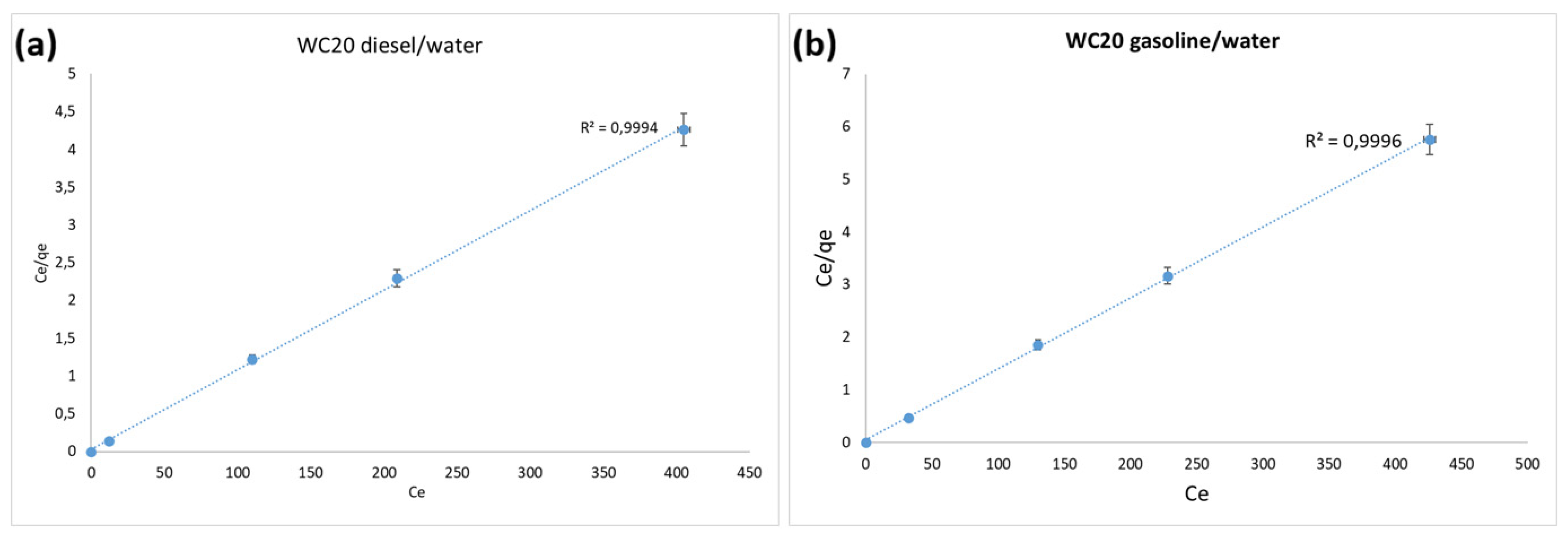

3.3.2. Adsorption Isotherms of WC20 in Diesel/Water and Gasoline/Water Systems

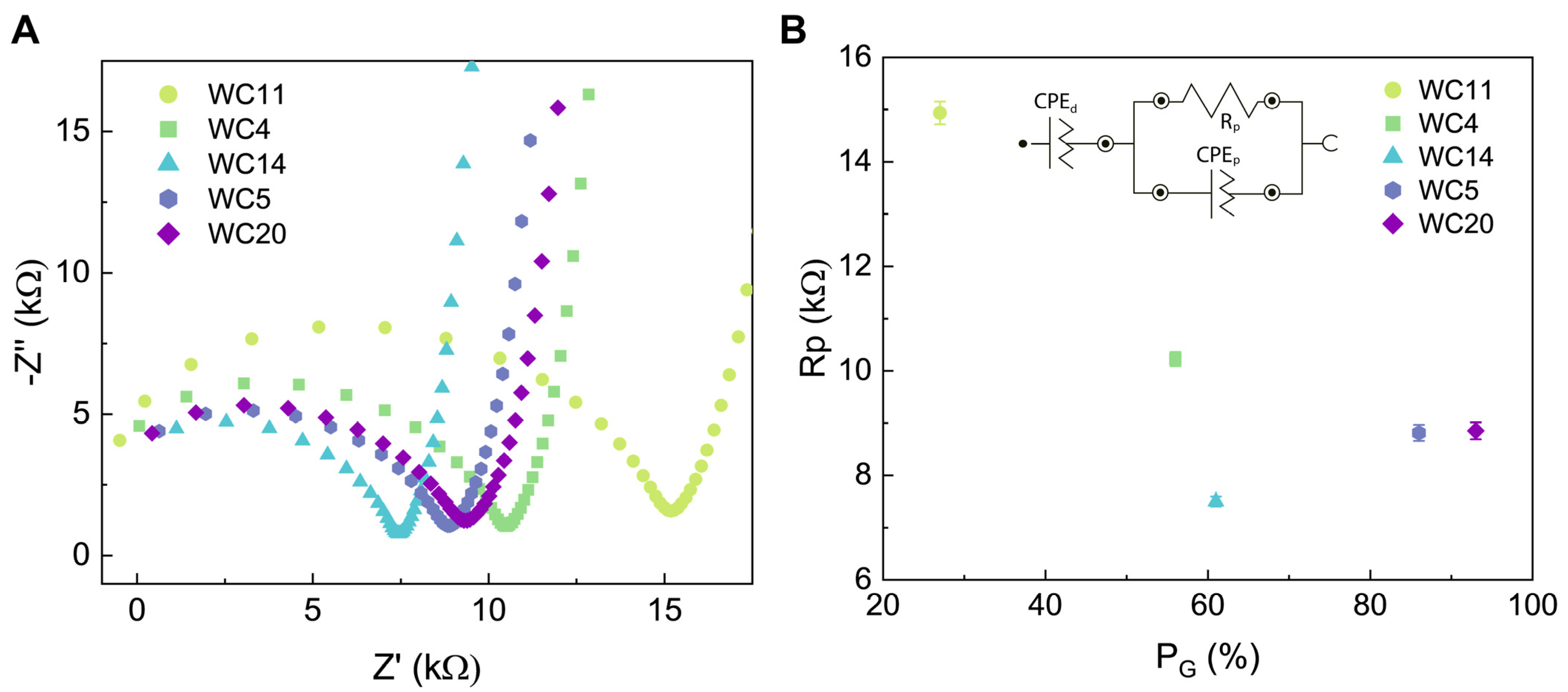

3.4. Results of the Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Awais, H.; Nawab, Y.; Amjad, A.; Anjang, A.; Akil, H.M.; Zainol Abidin, M. Environmental benign natural fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites: A review. Compos. Part C Open Access 2021, 4, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwuncha, S.C.; Anusionwu, C.G.; Owonubi, S.J.; Sadiku, E.R.; Busuguma, U.A.; Ibrahim, I.D. Extraction of Cellulose Nanofibers and Their Eco/Friendly Polymer Composites. In Sustainable Polymer Composites and Nanocomposites; Inamuddin, Thomas, S., Mishra, R.K., Asiri, A.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A. Pharmaceutical and biomedical applications of cellulose nanofibers: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2043–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhu, T.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, K.; Meng, Z.; Huang, J.; Cai, W.; Lai, Y. Recent Advances in Functional Cel-lulose-Based Materials: Classification, Properties, and Applications. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2024, 6, 1343–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Weng, Z.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, S.; Duan, G. Cellulose-Based Intelligent Responsive Materials: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, Z. Removal of organic pollutants from aqueous solution using agricultural wastes: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2015, 212, 739–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.; Khan, S.A. Agricultural Wastes as Renewable Biomass to Remediate Water Pollution. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Ahmad, N.; Akhtar, J.; Ahmad, N.M.; Ali, A.; Zia, M. Management of citrus waste by switching in the production of nanocellulose. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 10, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohni, S.; Begum, S.; Hashim, R.; Khan, S.B.; Mazhar, F.; Syed, F.; Khan, S.A. Physicochemical characterization of microcrystalline cellulose derived from underutilized orange peel waste as a sustainable resource under biorefinery concept. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 25, 101731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revathi, V.; Bora, S.; Afzia, N.; Ghosh, T. Orange peel composition, biopolymer extraction, and applications in paper and packaging sector: A review. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 43, 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Petri, G.L.; Angellotti, G.; Fontananova, E.; Luque, R.; Pagliaro, M. Nanocellulose and microcrystalline cellulose from citrus processing waste: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 135865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolo, M.R.V.; Pereira, T.S.; Dos Santos, F.V.; Facure, M.H.M.; Dos Santos, F.; Teodoro, K.B.R.; Mercante, L.A.; Correa, D.S. Citrus wastes as sustainable materials for active and intelligent food packaging: Current advances. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigi, F.; Maurizzi, E.; Haghighi, H.; Siesler, H.W.; Licciardello, F.; Pulvirenti, A. Waste Orange Peels as a Source of Cellulose Nanocrystals and Their Use for the Development of Nanocomposite Films. Foods 2023, 12, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahani, A.; Jazayeri, M.H. Tailoring cellulose: From extraction and chemical modification to advanced industrial applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 309, 142950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fabià, S.; Torstensen, J.; Johansson, L.; Syverud, K. Hydrophobization of lignocellulosic materials part III: Modification with polymers. Cellulose 2022, 29, 5943–5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Qu, P. Synthesis and characteristics of graft copolymers of poly(butyl acrylate) and cellulose fiber with ultrasonic processing as a material for oil absorption. BioResources 2012, 7, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teli, M.D.; Valia, S.P. Grafting of Butyl Acrylate on to Banana Fibers for Improved Oil Absorption. J. Nat. Fibers 2016, 13, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Tan, Y.; Du, J.; Wang, J. Synthesis and characterization of a porous and hydrophobiccellulose-based composite for efficient and fast oil–water separation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 140, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Y.; Yang, R.; Yang, X.; Qin, Z.; Yin, X. Preparation and characterization of quaternary bacterial cellulose composites for antimicrobial oil-absorbing materials. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmenbayeva, A.; Rajasekharan, R.; Massalimova, B.; Bektenov, N.; Taubayeva, R.; Bazarbaeva, K.; Kurmanaliev, M.; Mukazhanova, Z.; Nurlybayeva, A.; Bulekbayeva, K.; et al. Cellulose-Based Sorbents: A Comprehensive Review of Current Advances in Water Remediation and Future Prospects. Molecules 2024, 29, 5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivshina, I.B.; Kuyukina, M.S.; Krivoruchko, A.V.; Elkin, A.A.; Makarov, S.O.; Cunningham, C.J.; Peshkur, T.A.; Atlas, R.M.; Philp, J.C. Oil spill problems and sustainable response strategies through new technologies. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2015, 17, 1201–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, M.; Boumaza, M.M.; Kumar, N.S.; Al-Ghurabi, E.H.; Shahabuddin, M. Adsorptive Removal of Emulsified Automobile Fuel from Aqueous Solution. Separations 2023, 10, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyam, S.; Patra, S. Innovations and challenges in adsorption-based wastewater remediation: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, B.; Sepahvand, S.; Ismaeilimoghadam, S.; Kargarzadeh, H.; Ashori, A.; Jonoobi, M.; Danti, S. Application of Cellulose-Based Materials as Water Purification Filters; A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nino, A.; Tallarida, M.A.; Algieri, V.; Olivito, F.; Costanzo, P.; De Filpo, G.; Maiuolo, L. Sulfonated Cellulose-Based Magnetic Composite as Useful Media for Water Remediation from Amine Pollutants. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algieri, V.; Tursi, A.; Costanzo, P.; Maiuolo, L.; De Nino, A.; Nucera, A.; Castriota, M.; De Luca, O.; Papagno, M.; Caruso, T.; et al. Thiol-functionalized cellulose for mercury polluted water remediation: Synthesis and study of the adsorption properties. Chemosphere 2024, 355, 141891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nino, A.; Olivito, F.; Algieri, V.; Costanzo, P.; Jiritano, A.; Tallarida, M.A.; Maiuolo, L. Efficient and Fast Removal of Oils from Water Surfaces via Highly Oleophilic Polyurethane Composites. Toxics 2021, 9, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivito, F.; Algieri, V.; Jiritano, A.; Tallarida, M.A.; Costanzo, P.; Maiuolo, L.; De Nino, A. Bio-Based Polyurethane Foams for the Removal of Petroleum-Derived Pollutants: Sorption in Batch and in Continuous-Flow. Polymers 2023, 15, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nino, A.; Jiritano, A.; Meringolo, F.; Costanzo, P.; Algieri, V.; Fontananova, E.; Maiuolo, L. Catalytic Transesterification of Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCs) with Waste Oils: A Sustainable and Efficient Route to Form Reinforced Biofilms. Polymers 2025, 17, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahata, C.; Suzuki, J.; Mochizuki, A. Biocompatibility and adhesive strength properties of poly(methyl acrylate-co-acrylic acid) as a function of acrylic acid content. J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 2019, 34, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1141-98; Standard Practice for Preparation of Substitute Ocean Water. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- ASTM F726-99; Standard Test Method for Sorbent Performance of Adsorbent. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhong, W.; Du, J.; Hu, J.; Fu, C.; Lu, J.; Lv, Y.; Wang, H.; Tao, Y. Natural cellulose-based multifunctional architecture for electrochemical removal and detection of nanoplastic. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 76, 108259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, C.; Singh, V.; AlFantazi, A. Cellulose, cellulose derivatives and cellulose composites in sustainable corrosion protection: Challenges and opportunities. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 11217–11242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferro, M.; Mannu, A.; Panzeri, W.; Theeuwen, H.J.; Mele, A. An Integrated Approach to Optimizing Cellulose Mercerization. Polymers 2020, 12, 1559–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fittolani, G.; Seeberger, P.H.; Delbianco, M. Helical polysaccharides. Pept. Sci. 2020, 112, e24124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.K.; Singha, A.S.; Thakur, M.K. Graft Copolymerization of Methyl Acrylate onto Cellulosic Biofibers: Synthesis, Characterization and Applications. J. Polym. Environ. 2012, 20, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.M.; Thakur, M.K.; Gupta, R.K. Rapid synthesis of graft copolymers from natural cellulose fibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 98, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panesar, S.S.; Jacobb, S.; Misraa, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Functionalization of lignin: Fundamental studies on aqueous graft copolymerization with vinyl acetate. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 46, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, A.; Molina-Gutiérrez, S.; Li, W.S.J.; Caillol, S.; Ladmiral, V.; Lacroix-Desmazes, P.; Dalle Vacche, S. Biobased Composites by Photoinduced Polymerization of Cardanol Methacrylate with Microfibrillated Cellulose. Materials 2022, 15, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.K.; Singha, A.S.; Misra, B.N. Graft Copolymerization of Methyl Methacrylate onto Cellulosic Biofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 122, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongpipi, S.; Ye, D.; Gomez, E.D.; Gomez, E.W. Progress and Opportunities in the Characterization of Cellulose—An Important Regulator of Cell Wall Growth and Mechanics. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, M.R.H.M.; Kathiresan, S.; Mohan, S. FT-IR and FT-Raman Spectra and Normal Coordinate Analysis of Poly methyl methacrylate. Der Pharma Chem. 2010, 2, 316–323. [Google Scholar]

- Onwukamike, K.N.; Grelier, S.; Grau, É.; Cramail, H.; Meier, M.A. Sustainable Transesterification of Cellulose with High Oleic Sunflower Oil in a DBU-CO2 Switchable Solvent. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 6, 8826–8835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, T.T.; Yuan, T.; Xiao, S.; He, J. Synthesis of cellulose-graft-poly(methyl methacrylate) via homogeneous ATRP. BioResources 2011, 6, 2941–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Yuan, T.; Cao, H.; Lin, D.; Shen, Y.; He, J.; Wang, B. Synthesis and characterization of cellulose-graft-poly(L-lactide) via ring-opening polymerization. BioResources 2012, 7, 1748–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.J.; Lesic, R.A.; Proschogo, N.; Masters, A.F.; Maschmeyer, T. Strained surface siloxanes as source of synthetically important radicals. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 100618–100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, T.; Chen, Y.; Hu, X.; Xu, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Shen, H. A sustainable nanocellulose-based superabsorbent from kapok fiber with advanced oil absorption and recyclability. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 278, 118948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuka, J.C.; Agbaji, E.B.; Ajibola, V.O.; Okibe, F.G. Treatment of crude oil-contaminated water with chemically modified natural fiber. Appl. Water Sci. 2018, 8, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, F.Z.; Li, J.Y.; Na, P.; Wang, N. Preparation and Characterization of Cellulose Fibers from Corn Straw as Natural Oil Sorbents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.; Liu, X.; Zou, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Yin, T. Pomelo peel modified with acetic anhydride and styrene as new sorbents for removal of oil pollution. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 132, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.X.T.; Ho, K.H.; Nguyen, C.T.X.; Do, N.H.N.; Pham, A.P.N.; Do, T.C.; Le, K.A.; Le, P.K. Recent Developments in Water Treatment by Cellulose Aerogels from Agricultural Waste. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 947, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.T.; Nguyen, S.T.; Do, N.D.; Thai, N.N.T.; Thai, Q.B.; Huynh, H.K.P.; Nguyen, V.T.T.; Phan, A.N. Green aerogels from rice straw for thermal, acoustic insulation and oil spill cleaning applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 253, 123363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhai, S.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z. Anisotropic Cellulose Nanofibers/Polyvinyl Alcohol/Graphene Aerogels Fabricated by Directional Freeze-drying as Effective Oil Adsorbents. Polymers 2019, 11, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.W.; Chakravorti, R.K. Pore and solid diffusion models for fixed-bed adsorbers. AIChE J. 1974, 20, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etale, A.; Onyianta, A.J.; Turner, S.R.; Eichhorn, S.J. Cellulose: A Review of Water Interactions, Applications in Composites, and Water Treatment. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 2016–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samet, M.; Kallel, A.; Serghei, A. Maxwell-Wagner-Sillars interfacial polarization in dielectric spectra of composite materials: Scaling laws and applications. J. Compos. Mater. 2022, 56, 3197–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazanas, A.C.; Prodromidis, M.I. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy—A Tutorial. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2023, 3, 162–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascari, D.; Cataldo, S.; Muratore, N.; Prestopino, G.; Pignataro, B.; Lazzara, G.; Arrabito, G.; Pettignano, A. Label-free impedimetric analysis of microplastics dispersed in aqueous media polluted by Pb2+ ions. Anal. Methods 2024, 16, 7654–7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Verkhoturov, S.V.; Carrillo, L.; Lin, H.; Wangensteen, T.L.; Schweikert, E.A.; Banerjee, S. Nanocomposite Dielectric Films with Interphasic Response from Olefin Metathesis of Functionalized HfO2 Nanocrystals. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. J. 2023, 1, 2817–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeba, F.; Shrivastava, K.; Bafna, M.; Jain, A. Tuning of Dielectric Properties of Polymers by Composite Formation: The Effect of Inorganic Fillers Addition. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguedo, J.; Lorencova, L.; Barath, M.; Farkas, P.; Tkac, J. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy on 2D Nanomaterial MXene Modified Interfaces: Application as a Characterization and Transducing Tool. Chemosensors 2020, 8, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Seo, Y.J.; Jeong, H.T. Capacitive behaviour of functionalized activated carbon-based all-solid-state supercapacitor. Carbon Lett. 2021, 31, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmgren-Hansen, B.; Sørensen, T.S.; Jensen, J.B.; Hennenberg, M. Electric impedance of cellulose acetate membranes and a composite membrane at different salt concentrations. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1989, 30, 359–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruano, G.; Iribarren, J.I.; Pérez-Madrigal, M.M.; Torras, J.; Alemán, C. Electrical and Capacitive Response of Hydrogel Solid-Like Electrolytes for Supercapacitors. Polymers 2021, 13, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry 1 | Product | Starting Material | Mercerization | PG (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MCC1 | MCC | No | - |

| 2 | MCC2 | MCC | Yes | 7.5 |

| 3 | WC1 | WC | No | 1 |

| 4 | WC2 | WC | Yes | 16 |

| Entry a | Product | Monomer (mol/L) | Solvent (mL) | FAS/KPS (mol:mol) | Time (min) | T (°C) | PG (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WC3 | 0.16 | 100 | 1:1 | 120 | 55 | 47 |

| 2 | WC4 | 0.20 | 100 | 1:1 | 120 | 55 | 56 |

| 3 | WC5 | 0.24 | 100 | 1:1 | 120 | 55 | 86 |

| 4 | WC6 | 0.28 | 100 | 1:1 | 120 | 55 | 60 |

| 5 | WC7 | 0.32 | 100 | 1:1 | 120 | 55 | 62 |

| 6 b | WC8 | 0.24 | 100 | 1:1 | 120 | 55 | 80 |

| 7 c | WC9 | 0.24 | 100 | 1:1 | 120 | 55 | 2 |

| 8 | WC10 | 0.24 | 50 | 1:1 | 120 | 55 | 10 |

| 9 | WC11 | 0.24 | 125 | 1:1 | 120 | 55 | 27 |

| 10 | WC12 | 0.24 | 100 | 1:0.5 | 120 | 55 | 5 |

| 11 | WC13 | 0.24 | 100 | 1:0.3 | 120 | 55 | 4 |

| 12 | WC14 | 0.24 | 100 | 0.3:1 | 120 | 55 | 61 |

| 13 | WC15 | 0.24 | 100 | 0.5:1 | 120 | 55 | 51 |

| 14 | WC16 | 0.24 | 100 | 1:1 | 60 | 55 | 12 |

| 15 | WC17 | 0.24 | 100 | 1:1 | 90 | 55 | 74 |

| 16 | WC18 | 0.24 | 100 | 1:1 | 150 | 55 | 55 |

| 17 | WC19 | 0.24 | 100 | 1:1 | 120 | 45 | 3 |

| 18 | WC20 | 0.24 | 100 | 1:1 | 120 | 65 | 93 |

| 19 | WC21 | 0.24 | 100 | 1:1 | 120 | 75 | 81 |

| Entry | Sorption Capacity | MCC | MWC | WC11 | WC4 | WC20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S0 * | 0.0204 g | 0.0202 g | 0.0199 g | 0.0201 g | 0.0203 g |

| 2 | S (diesel) | 0.56 ± 0.04 g/g | nd | nd | 2.38 ± 0.09 g/g | 3.87 ± 0.05 g/g |

| 3 | S (gasoline) | 0.49 ± 0.03 g/g | nd | nd | 1.84 ± 0.08 g/g | 2.79 ± 0.04 g/g |

| 4 | S (diesel/art. seawater) | nd | nd | nd | 2.45 ± 0.1 g/g | 3.95 ± 0.06 g/g |

| 5 | S (gasoline/art. seawater) | nd | nd | nd | 1.92 ± 0.06 g/g | 2.91 ± 0.05 g/g |

| 6 | S (diesel/seawater) | nd | nd | nd | 2.61 ± 0.08 g/g | 4.01 ± 0.05 g/g |

| 7 | S (gasoline/seawater) | nd | nd | nd | 1.96 ± 0.09 g/g | 2.95 ± 0.04 g/g |

| WC20 | Diesel | Gasoline | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qe(mg/mg) experimental | 89.4 | 68.1 | ||

| Pseudo-first-order | R2 | 0.9371 | R2 | 0.9227 |

| qe (mg/mg) | 49.83 | qe (mg/mg) | 92.73 | |

| k1 | 0.032 | k1 | 0.037 | |

| Pseudo-second-order | R2 | 0.9994 | R2 | 0.9937 |

| qe (mg/mg) | 92.71 | qe (mg/mg) | 78.74 | |

| k2 | 0.909 | k2 | 0.022 | |

| WC20 | Diesel | Gasoline | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | R2 | 0.9994 | R2 | 0.9996 |

| qm (mg/mg) | 5.24 | qm (mg/mg) | 74.07 | |

| KL | 1.0135 | KL | 0.15 | |

| Freundlich | R2 | 0.7826 | R2 | 0.9525 |

| n | 53.76 | n | 31.06 | |

| KF | 6.83 | KF | 5.94 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maiuolo, L.; Jiritano, A.; Costanzo, P.; Meringolo, F.; Algieri, V.; Arrabito, G.; Puleo, G.; De Nino, A. Functionalized Cellulose from Citrus Waste as a Sustainable Oil Adsorbent Material. Polymers 2026, 18, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010082

Maiuolo L, Jiritano A, Costanzo P, Meringolo F, Algieri V, Arrabito G, Puleo G, De Nino A. Functionalized Cellulose from Citrus Waste as a Sustainable Oil Adsorbent Material. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010082

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaiuolo, Loredana, Antonio Jiritano, Paola Costanzo, Federica Meringolo, Vincenzo Algieri, Giuseppe Arrabito, Giorgia Puleo, and Antonio De Nino. 2026. "Functionalized Cellulose from Citrus Waste as a Sustainable Oil Adsorbent Material" Polymers 18, no. 1: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010082

APA StyleMaiuolo, L., Jiritano, A., Costanzo, P., Meringolo, F., Algieri, V., Arrabito, G., Puleo, G., & De Nino, A. (2026). Functionalized Cellulose from Citrus Waste as a Sustainable Oil Adsorbent Material. Polymers, 18(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010082