Effect of Olive Stone Biomass Ash Filler in Polylactic Acid Biocomposites on Accelerated Weathering Tests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

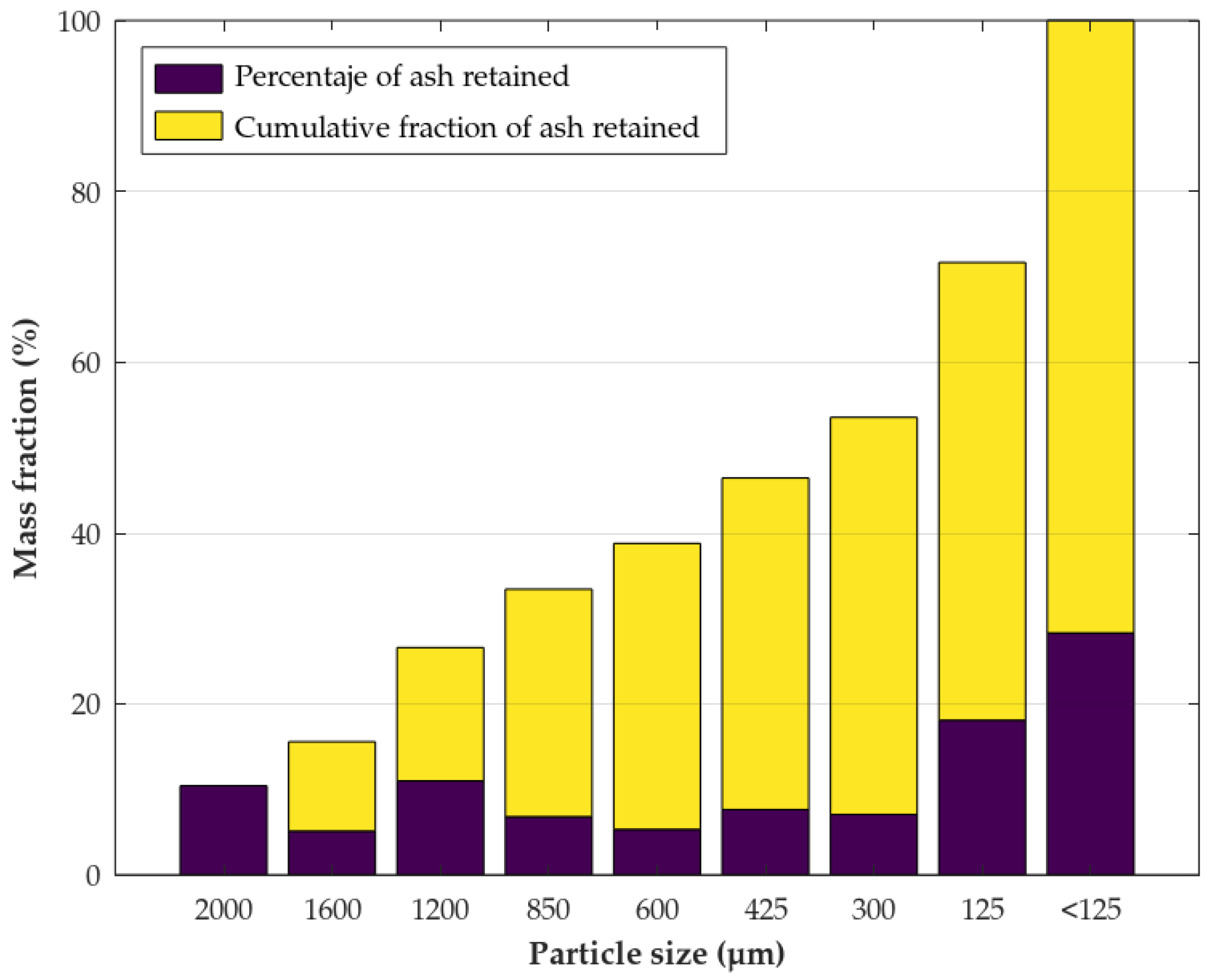

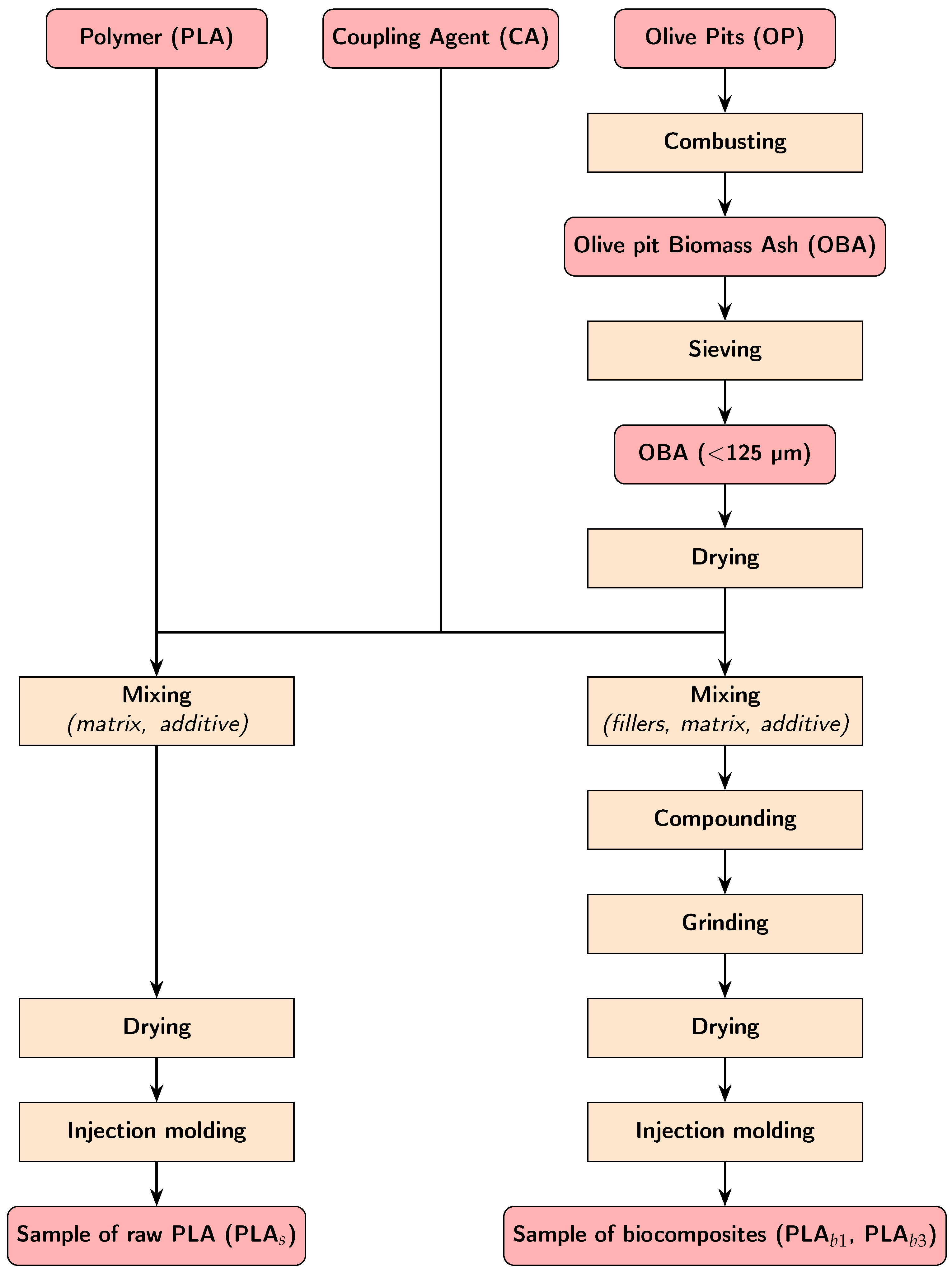

2.1. Materials

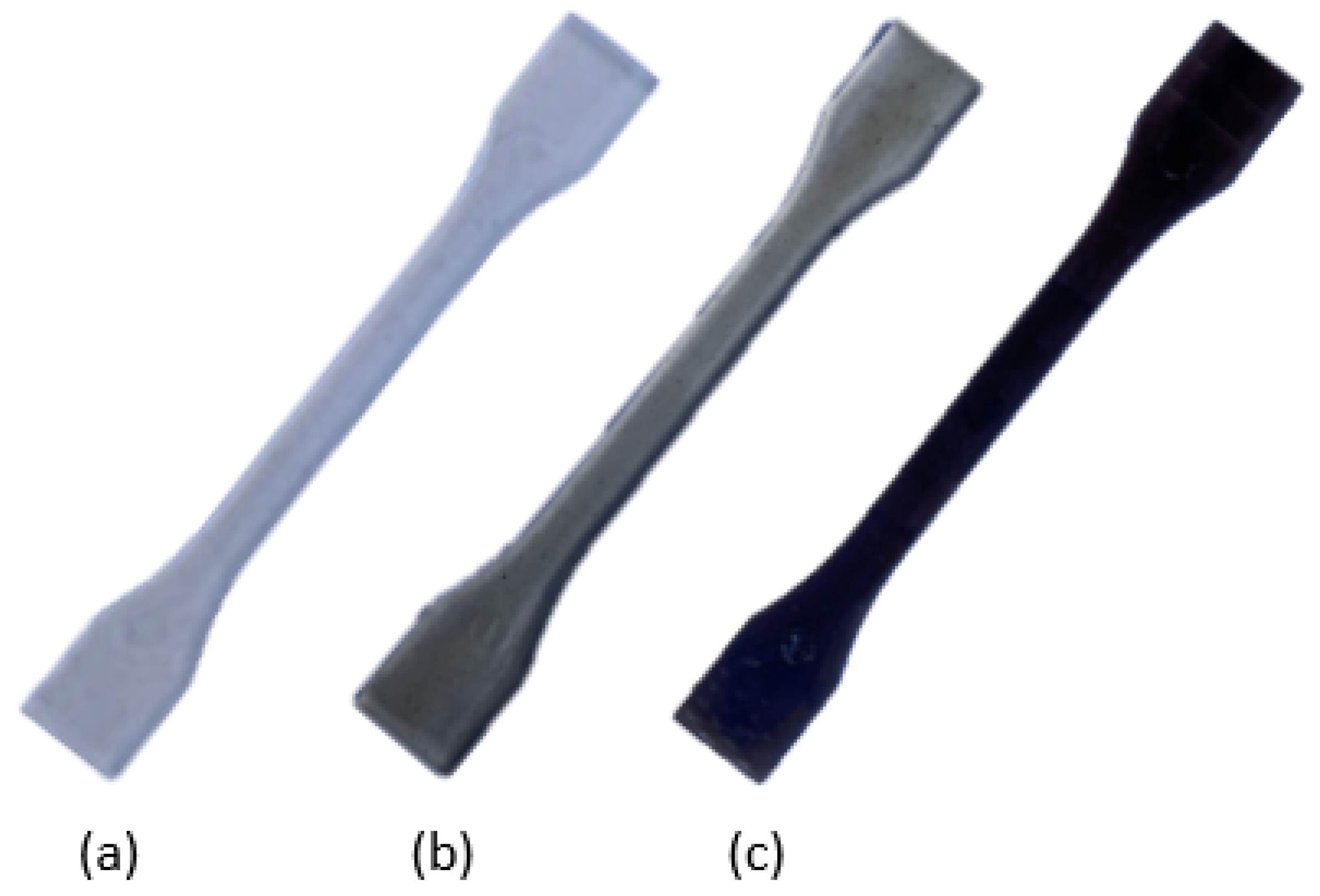

2.2. Compounding and Processing

2.3. Weathering Tests

2.4. Tensile Test

2.4.1. Effective Composite Moduli

2.4.2. Yield Strength

2.5. Color Measurements

2.6. Surface Gloss Measurements

2.7. ATR-FTIR

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.9. Thermal Analysis

2.10. Kinetics

2.11. Acceleration Factor (AF)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Weathering Tests

3.1.1. Photolysis

3.1.2. Hydrolysis and Thermal Effects

3.1.3. Cyclic Effects

3.2. Tensile Test

3.2.1. Effective Composite Moduli

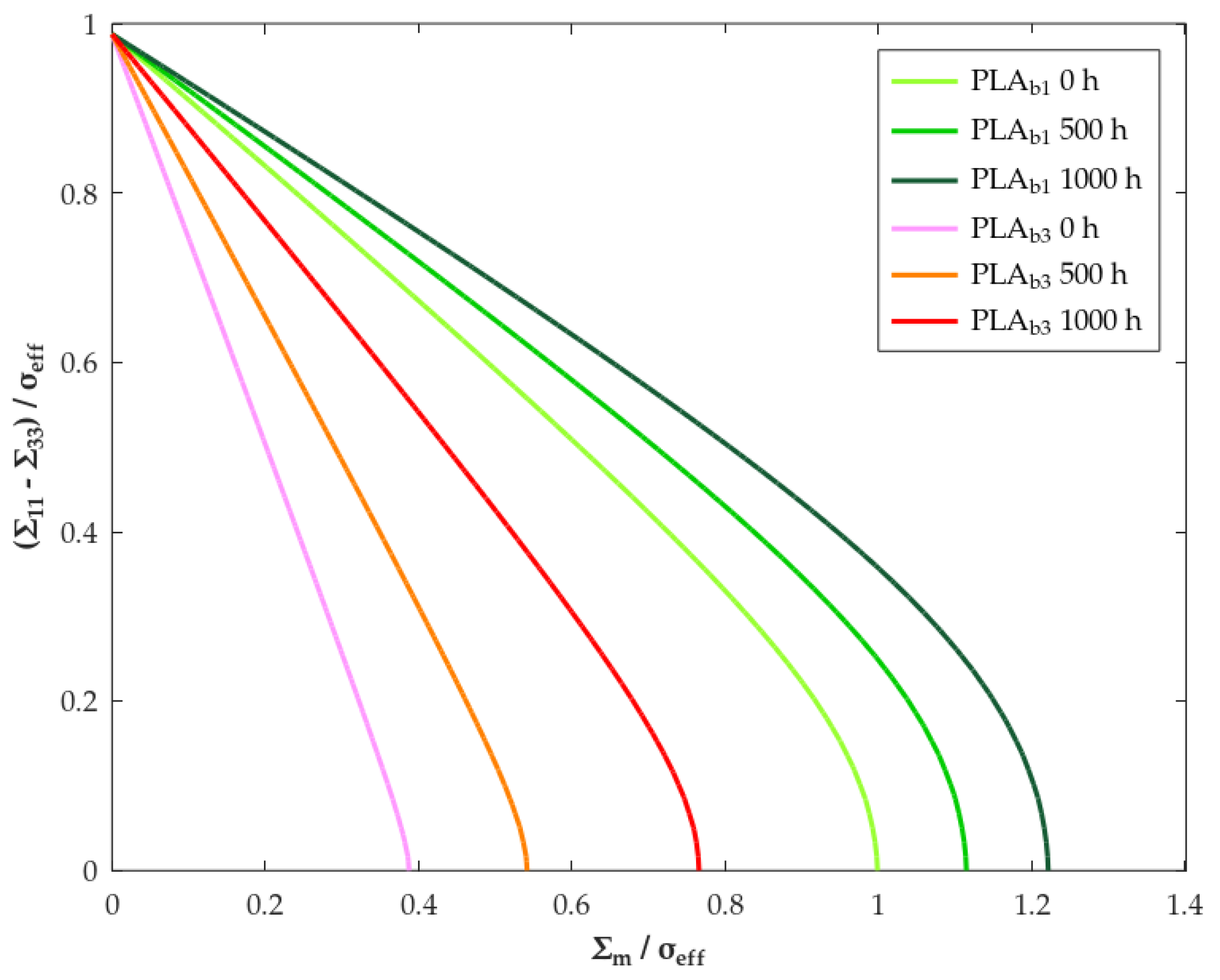

3.2.2. Yield Strength

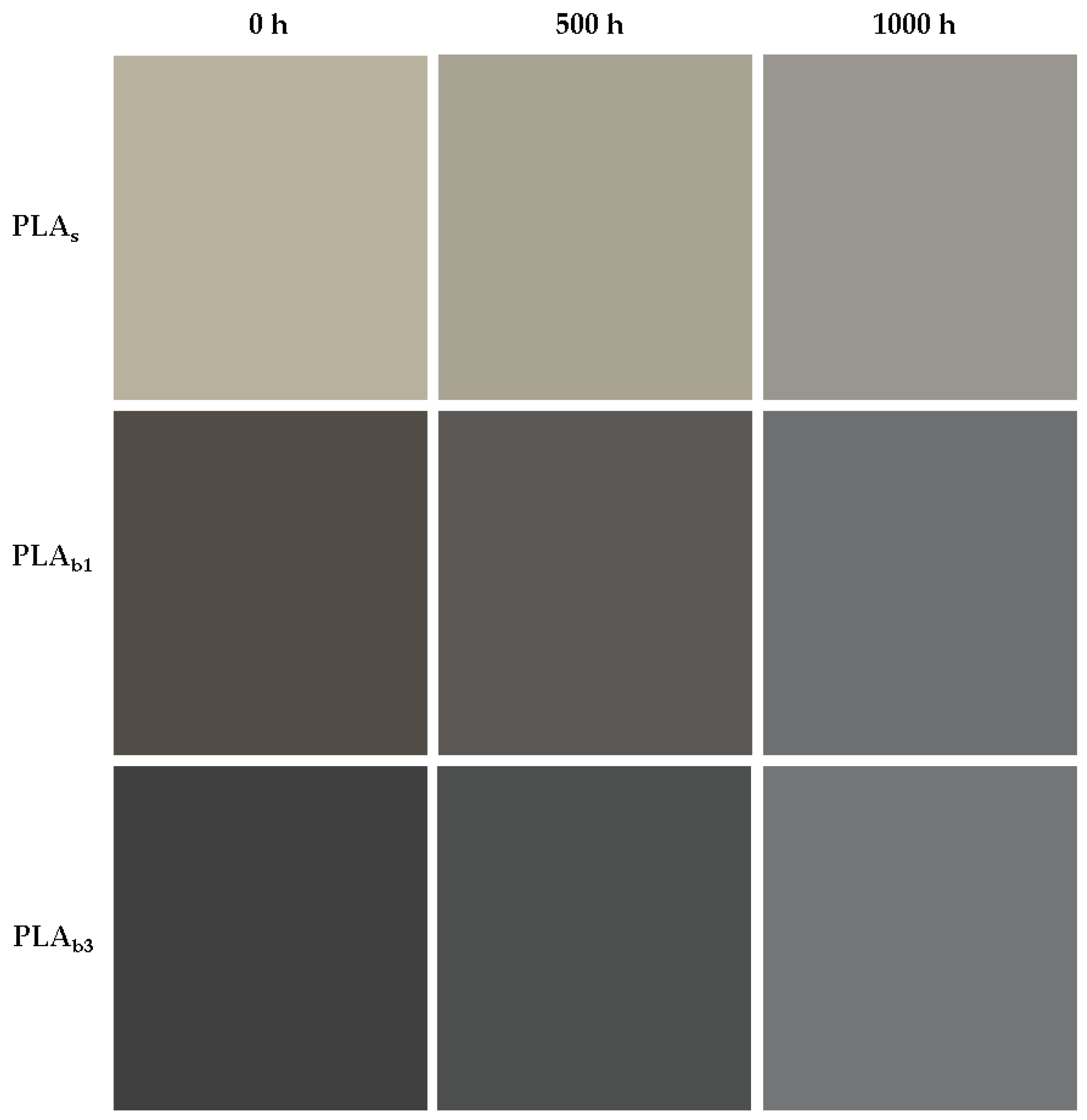

3.3. Color Change

3.4. Gloss Change

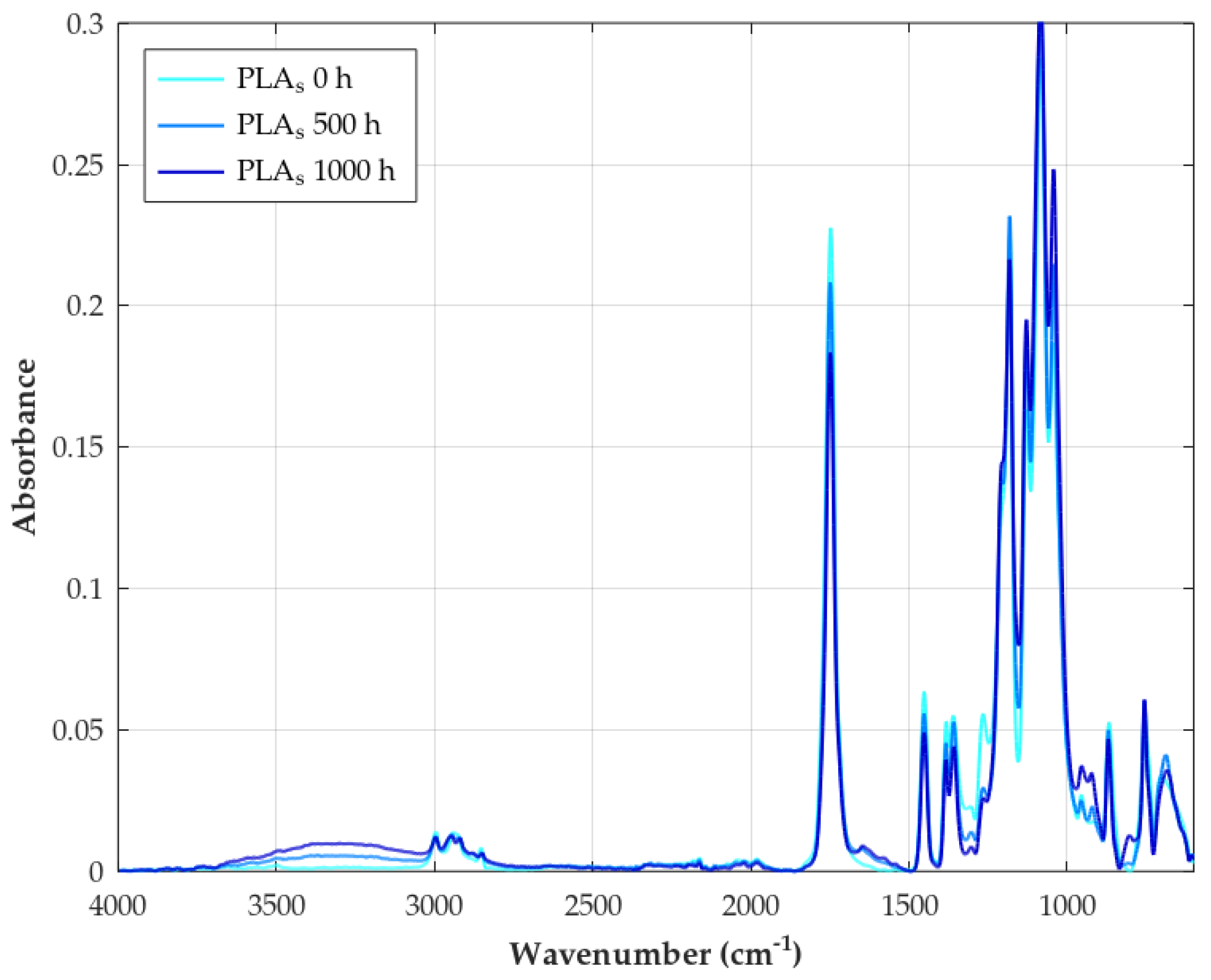

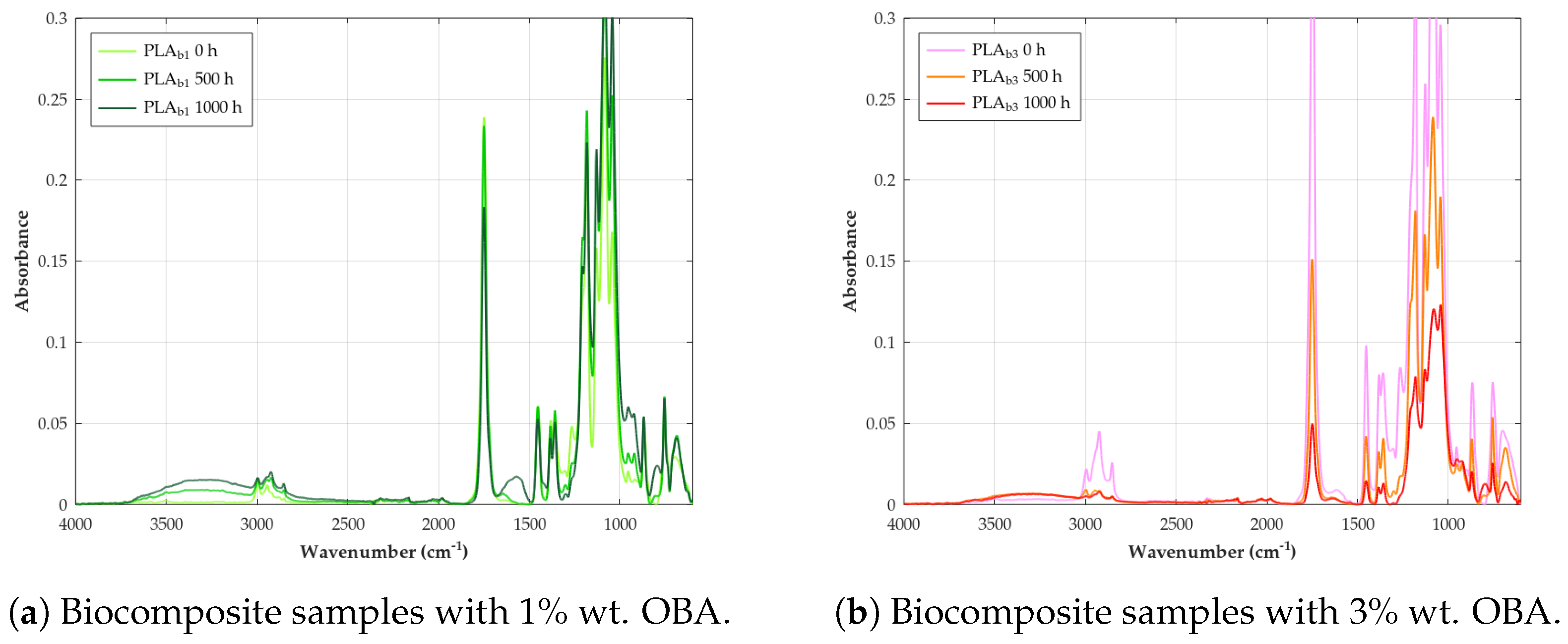

3.5. FTIR

- Decreased ester carbonyl (C=O) stretching: An absorption peak observed at corresponds to the stretching vibration of the ester carbonyl group (C=O) in the polymer backbone [82]. A significant reduction in the intensity of this band is a primary and universal indicator of PLA degradation during weathering, reflecting the cleavage of ester bonds via hydrolysis and photolytic chain scission [115].

- Appearance of hydroxyl (O–H) stretching: Weathering leads to the formation or accumulation of hydroxyl groups, resulting in the appearance of broad absorption bands in the high-frequency region, typically ∼3100– [59]. These bands are assigned to the O–H stretching vibrations of carboxylic acid end groups (–COOH) and alcohol end groups (–OH) formed by hydrolysis, as well as potentially to hydroperoxides (–OOH) formed during photo-oxidation processes [116].

- Appearance of carbon–carbon double bonds (C=C): A key indicator of the Norrish Type II photolysis mechanism is the appearance of new absorption peaks in the region 1645– These bands are assigned to the stretching vibration of C=C double bonds, specifically the vinyl end groups formed as a direct product of this photochemical chain scission pathway [80].

- Changes in C–O stretching region: The spectral region between approximately 1000 cm−1 and is complex, containing multiple overlapping bands associated with various C–O stretching vibrations within the PLA structure (e.g., asymmetric and symmetric C–O–C stretches) as well as C–C stretches. Characteristic peaks for PLA are identified at 1266, 1208, 1182, 1129, 1083, and Degradation causes noticeable changes in this region, for example, peaks at have been linked specifically to ester bond cleavage during hydrolysis/oxidation, lowering absorbance [117]. Decreases in intensity at and changes around have also been observed during thermal/hydrolytic aging. Conversely, increases at and (attributed to new C=O formation) were noted during thermo-oxidative degradation [118].

- Changes in C–H region: Bands related to C–H vibrations include asymmetric or symmetric stretching (∼2800–) and bending or deformation modes (e.g., methyl group bends at and C–H deformations at ) [119]. The band around (CH deformation or bending) is often considered relatively stable and is sometimes used as an internal reference peak for calculating degradation indices [59]. Reduced intensity in the region has also been linked to thermo-oxidative degradation [118].

- Changes in crystallinity-related bands: Specific bands in the fingerprint region can be sensitive to the polymer’s morphology (crystalline vs. amorphous phases). A peak around is often associated with ordered structures or -crystals, while a peak near is attributed to the amorphous phase [118]. Changes in the relative intensities of these bands during weathering can indicate an increase in crystallinity (chemo-crystallization).

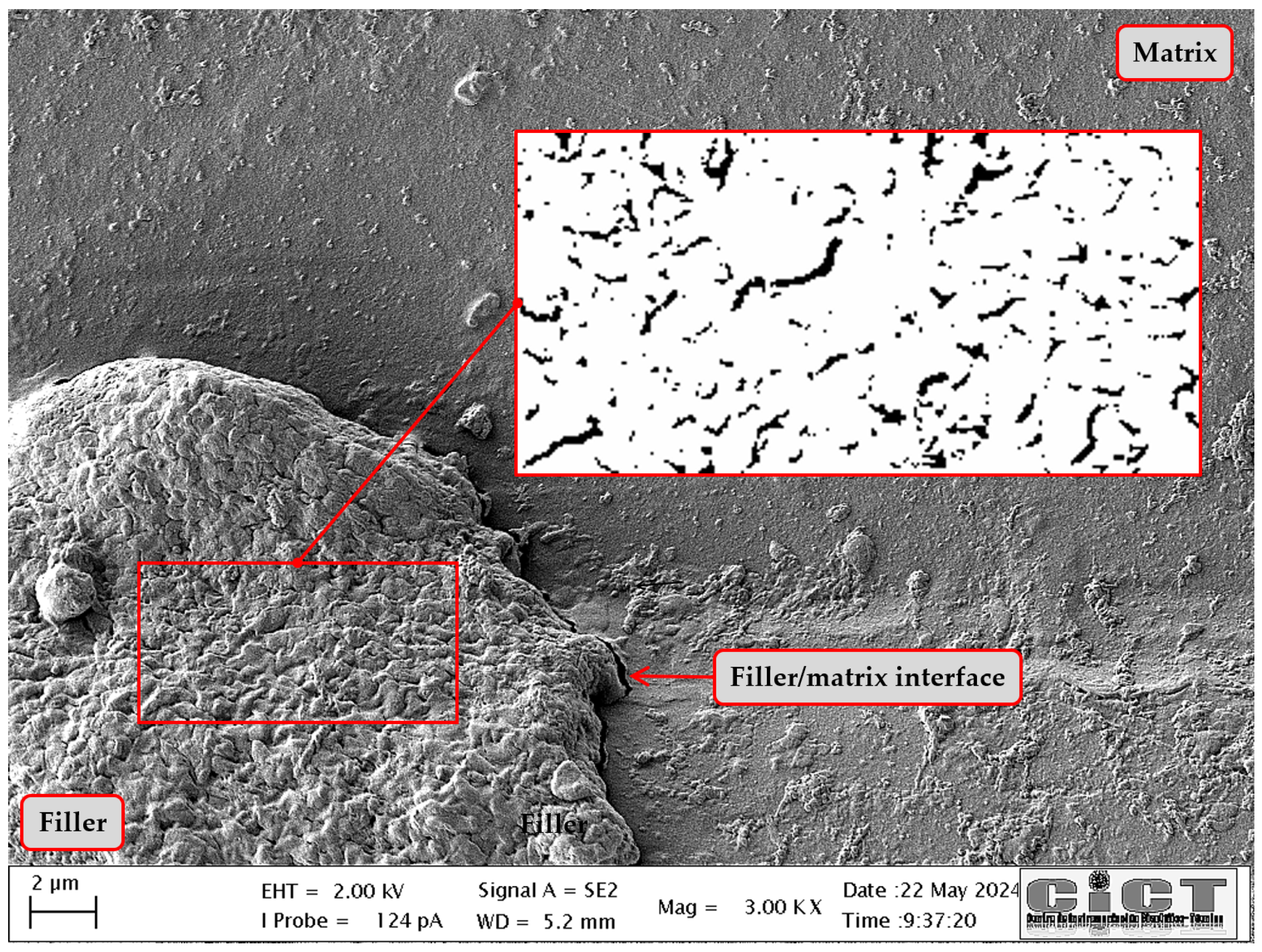

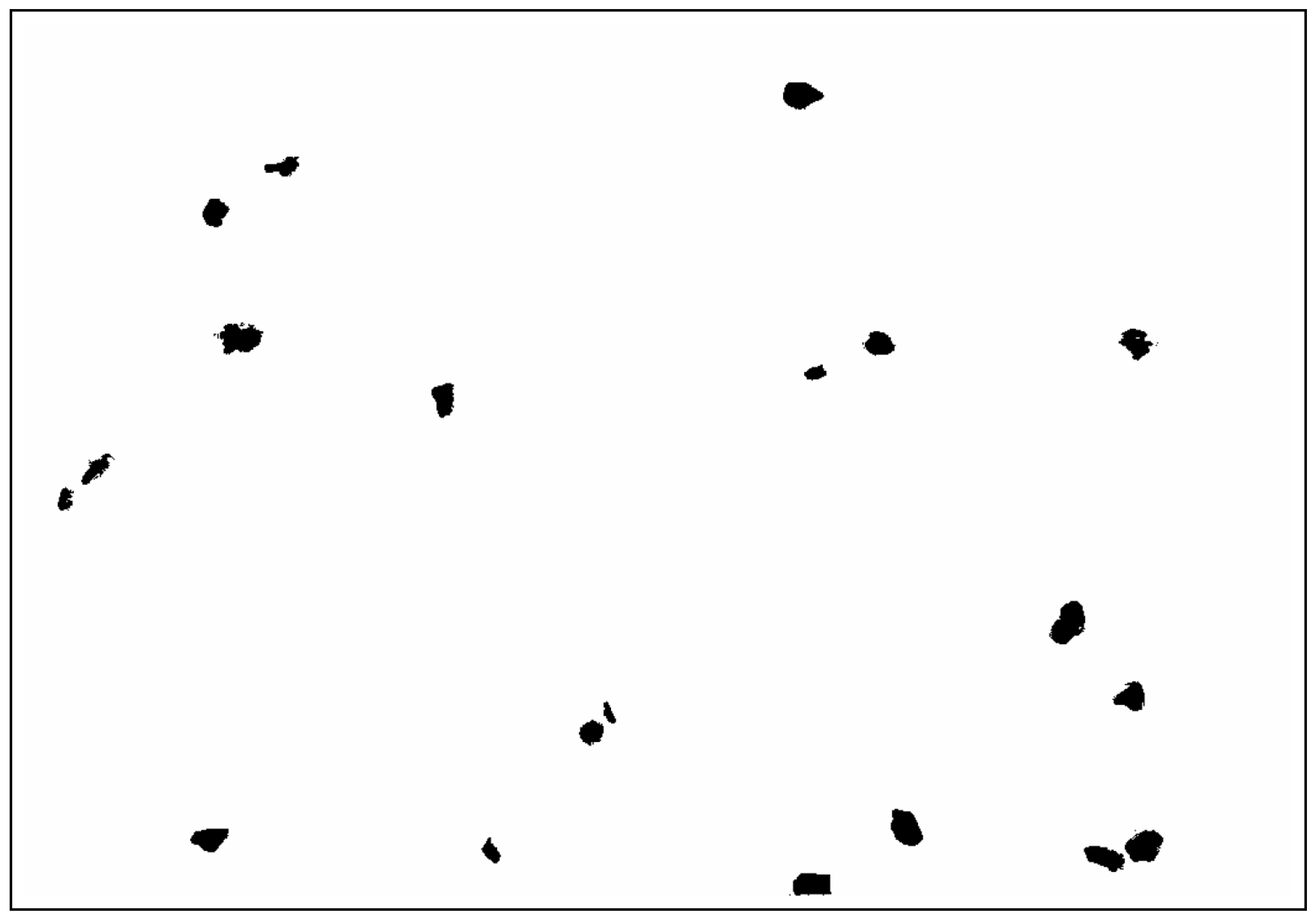

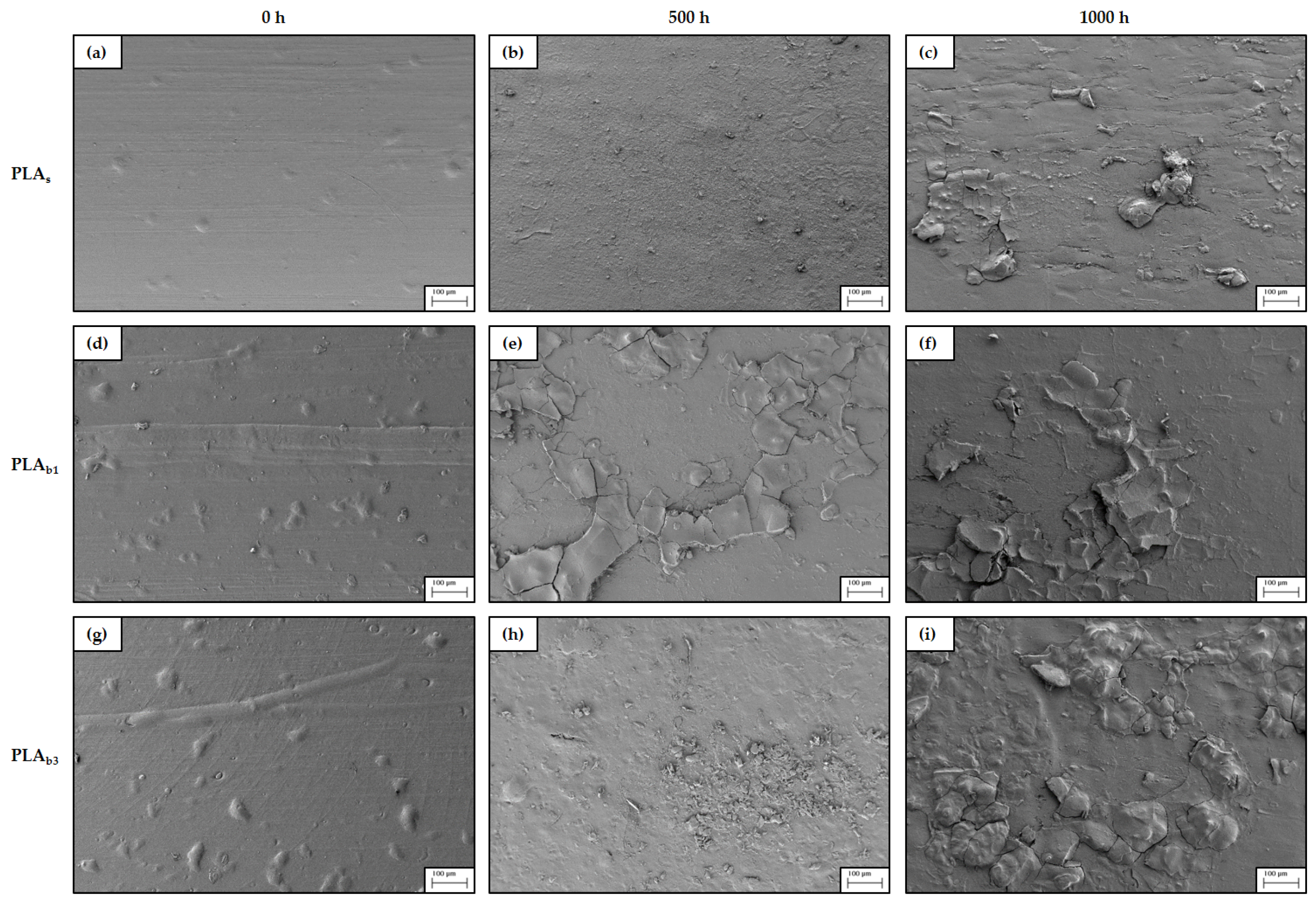

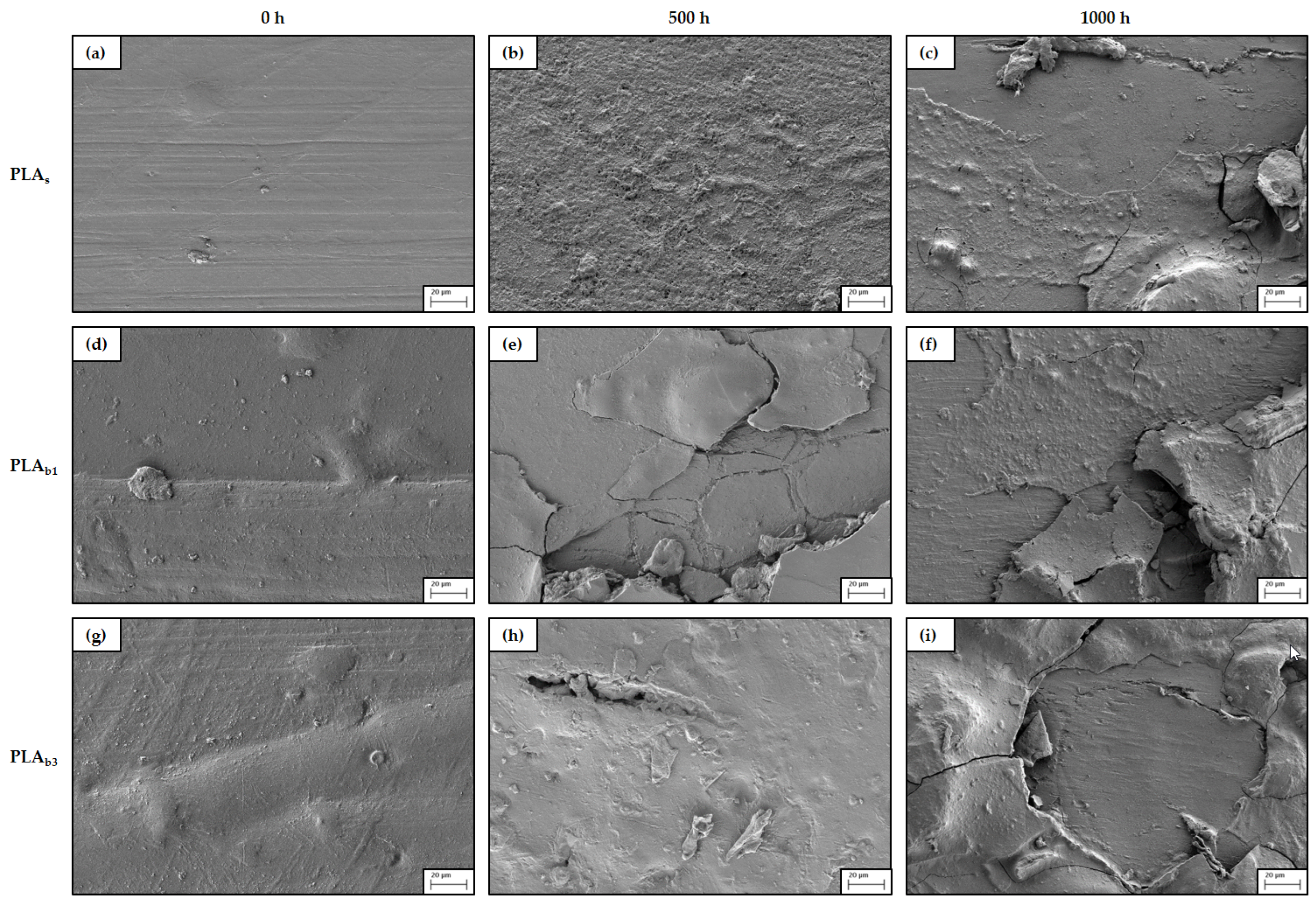

3.6. SEM

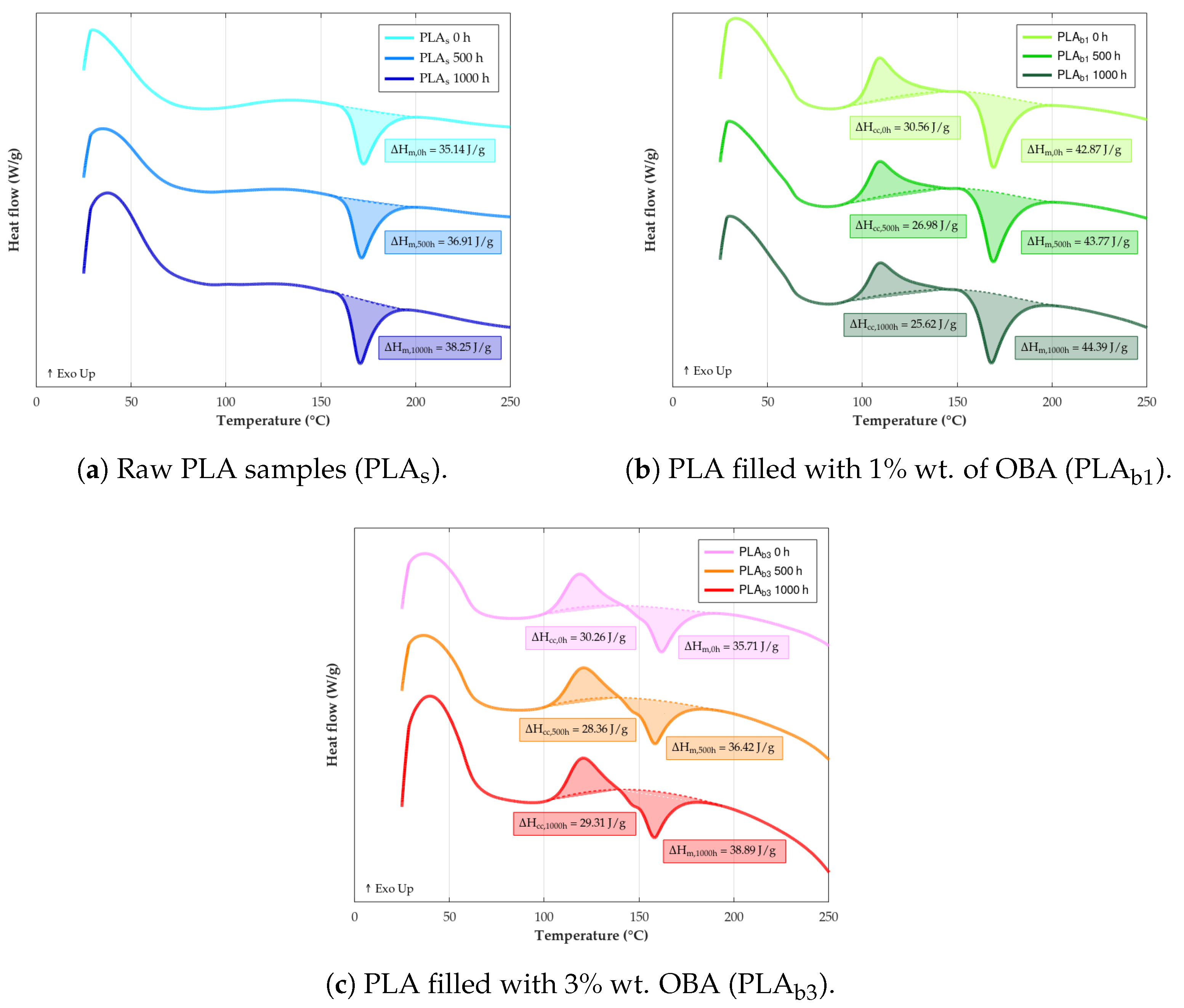

3.7. DSC

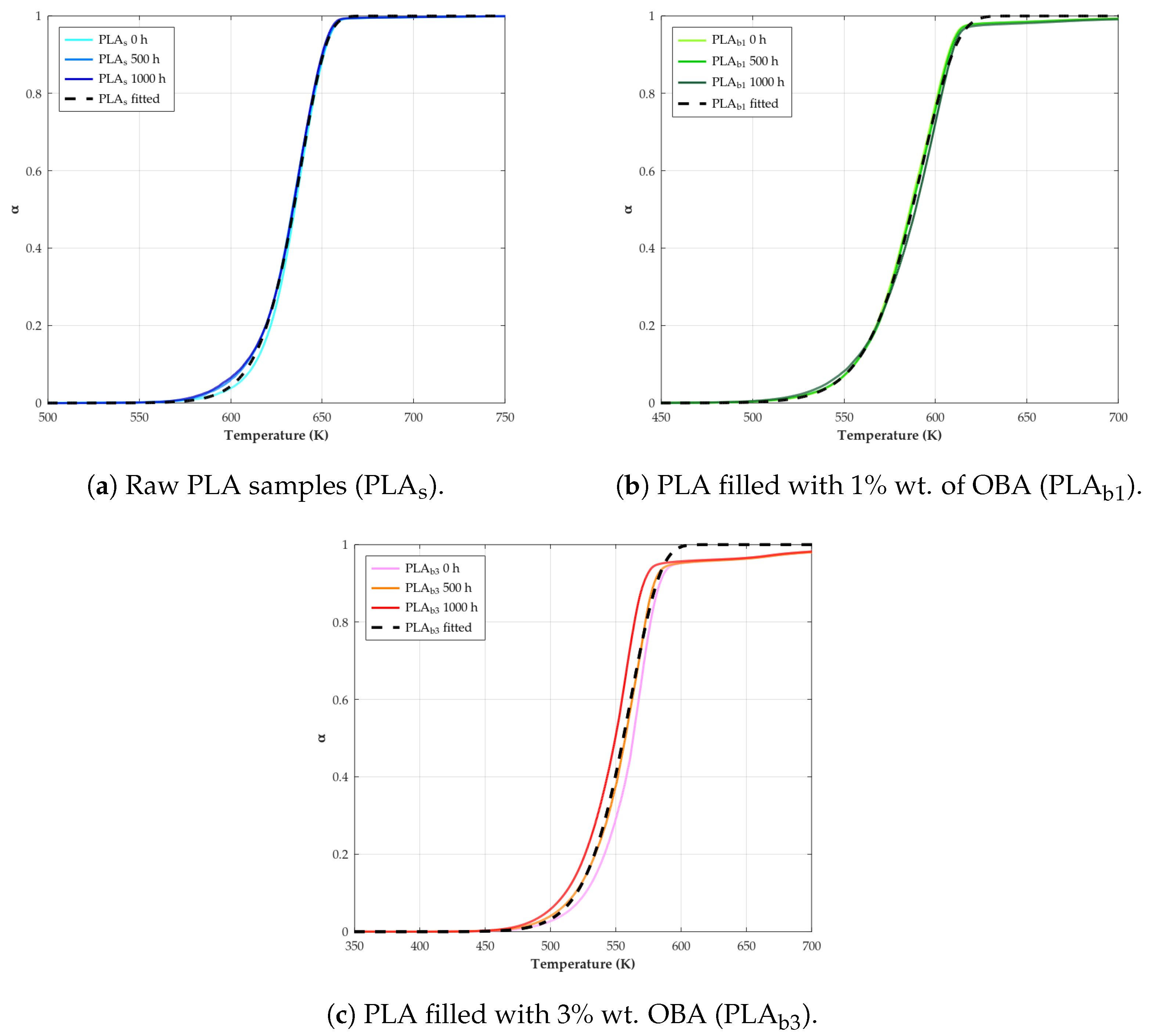

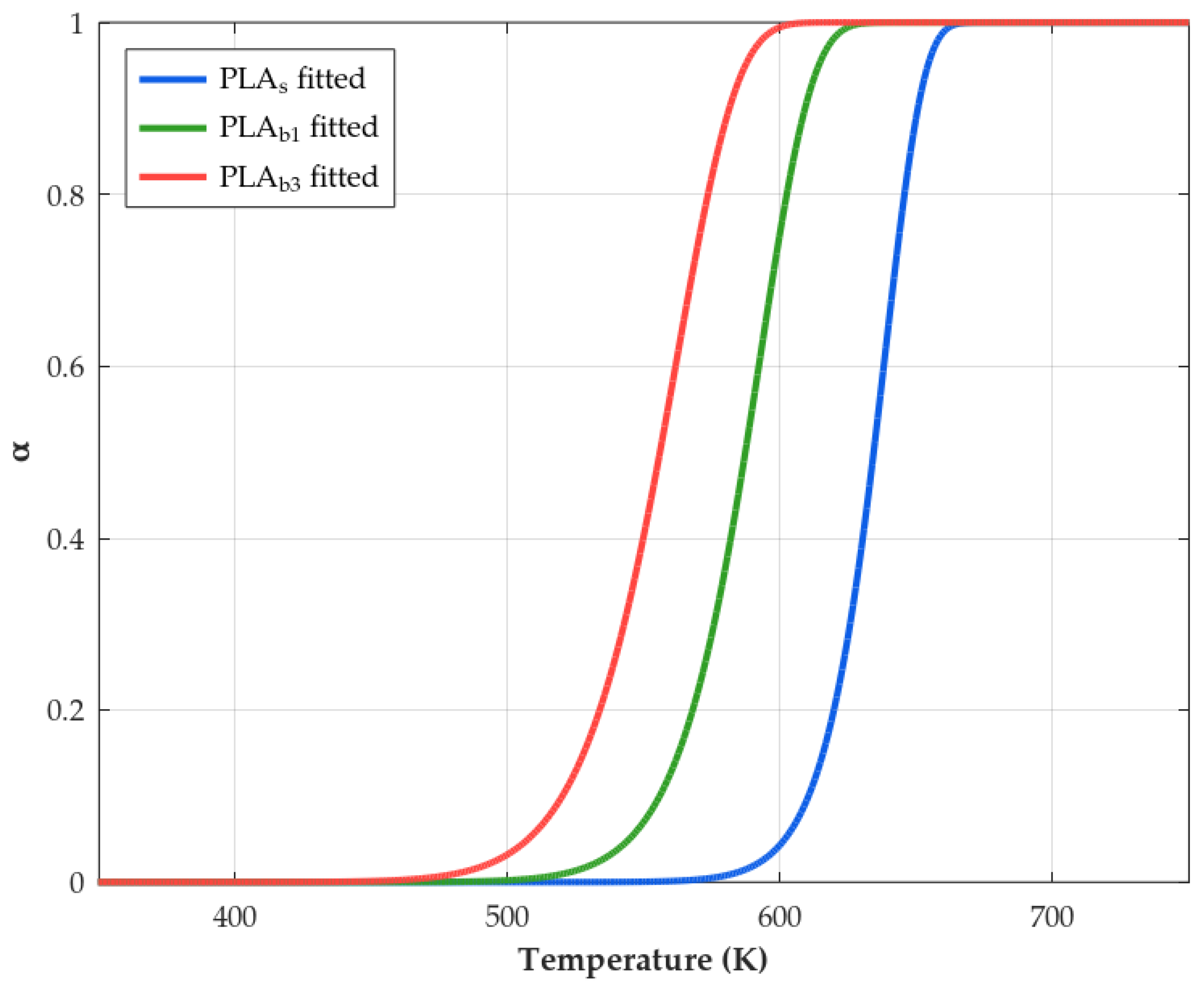

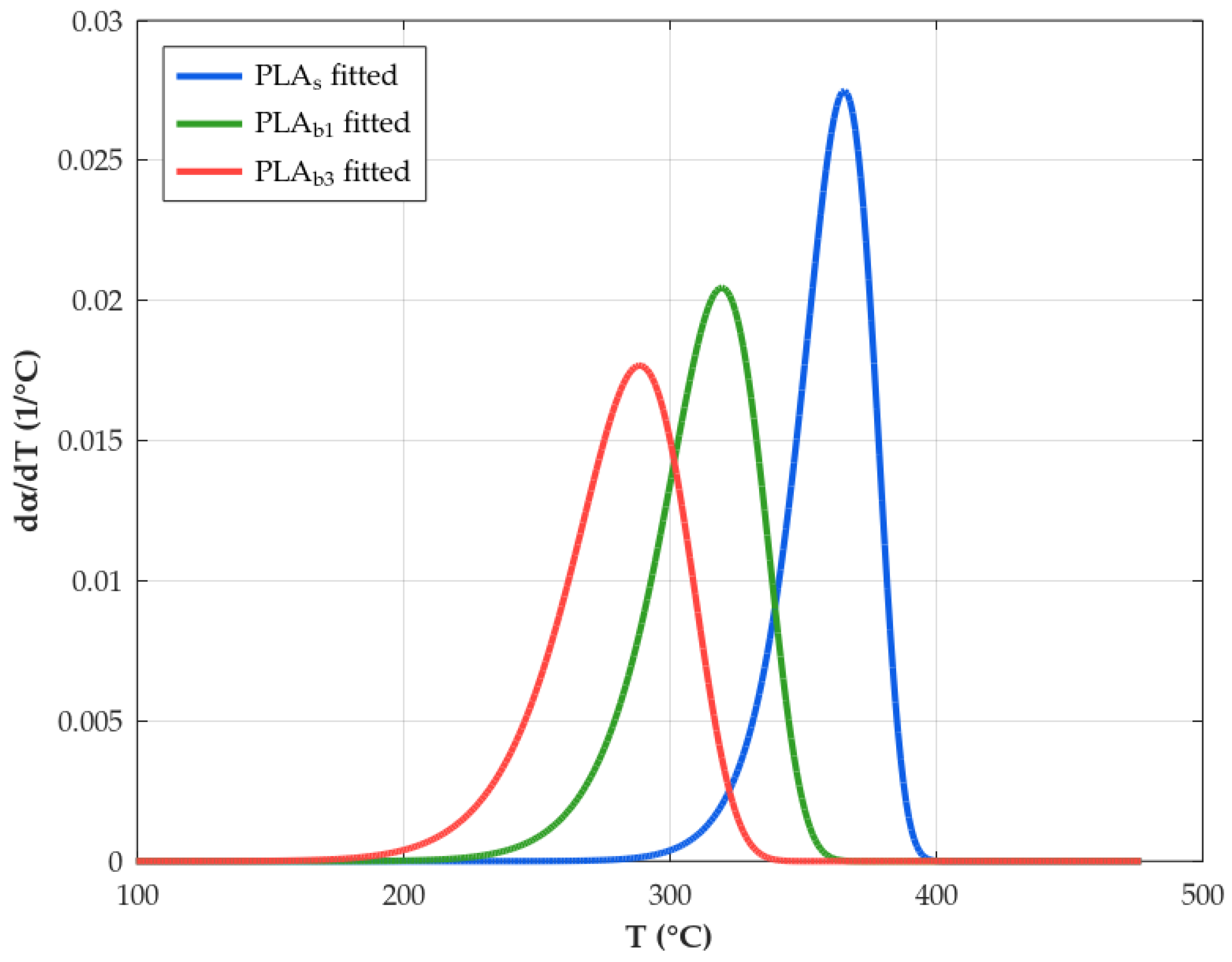

3.8. Kinetics

3.9. Acceleration Factor

4. Conclusions

- Weathering resistance: OBA reinforcement accelerated the degradation of PLA biocomposites under UV, heat, and humidity cycles. Higher OBA content led to more severe surface erosion, microcracking, and delamination due to poor filler–matrix interfacial adhesion and moisture absorption by hydrophilic OBA.

- Mechanical properties: The addition of OBA reduced the stiffness and tensile strength of PLA, with greater reductions at higher filler loadings. This is attributed to OBA agglomerates acting as a soft inclusion (stress concentrator) and weak interfacial bonding, as confirmed by micromechanical modeling and SEM analysis. Weathering further reduces mechanical properties by inducing chain scission and microcracks. Crack density increased with exposure time and was highest in PLAb3.

- Optical and aesthetic properties: Weathering led to noticeable changes () in color and surface gloss. While raw PLA darkened and lost gloss due to crystallization and surface erosion, biocomposites showed a whitening effect and better gloss retention, albeit starting from a lower initial gloss due to ash content.

- Chemical degradation: FTIR analysis revealed that weathering caused ester bond cleavage, the formation of hydroxyl and carbonyl groups, and increased crystallinity. The increased significantly with exposure time, especially in ash reinforced samples, indicating enhanced hydrolytic degradation. The showed no consistent trend, likely due to competing degradation mechanisms (photolysis vs. ester bond cleavage).

- Thermal behavior: OBA acted as a nucleating agent, promoting cold crystallization in PLA and increasing crystallinity () over weathering time. However, it lowered the melting temperature () and glass transition temperature (), indicating reduced thermal stability. Kinetics analysis revealed lower activation energy () and pre-exponential factor (A) values for biocomposites, confirming accelerated thermal degradation with OBA addition. This is potentially due to the catalytic effect of OBA’s potassium content and poor filler–matrix cohesion.

- Morphological changes: SEM observations indicated that weathering induced surface microcracking and roughness, which were more severe in PLAb3, suggesting that higher filler content exacerbates surface degradation. SEM confirmed advanced surface degradation in OBA composites, including pitting, flaking, and delamination after 1000 h of exposure.

- Acceleration Factor (AF): The xenon arc accelerated weathering protocol (ISO 4892-2) provided an AF of ≥15× relative to natural weathering in Miami or Phoenix, where humidity (hydrolysis) was a critical degradation driver, especially for biocomposites. However, it is emphasized that this is an estimate and not an absolute value.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Compressibility P and Shear Q for Prolate Spheroidal Pores

Appendix B. Parameters of the Macroscopic Yield Criterion for Spheroidal Voids

References

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R. Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications—A comprehensive review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenboom, J.-G.; Langer, R.; Traverso, G. Bioplastics for a circular economy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vert, M. Lactic acid-based degradable polymers. In Handbook of Biodegradable Polymers; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2020; Chapter 9; pp. 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, T.; Nunes, J.; Lopes, M.A.; Marinho, E.; Proença, M.F.; Lopes, P.E.; Paiva, M.C. Poly(lactic acid) composites with few layer graphene produced by noncovalent chemistry. Polym. Compos. 2022, 43, 8409–8425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, M.; Erraach, Y.; López-i Gelats, F.; Martin, J.M.; Yatribi, T.; Radić, I.; El Hadad-Gauthier, F. Circular bioeconomy for olive oil waste and by-product valorisation: Actors’ strategies and conditions in the Mediterranean area. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valvez, S.; Maceiras, A.; Santos, P.; Reis, P.N.B. Olive Stones as Filler for Polymer-Based Composites: A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutsomitopoulou, A.F.; Bénézet, J.C.; Bergeret, A.; Papanicolaou, G.C. Preparation and characterization of olive pit powder as a filler to PLA-matrix bio-composites. Powder Technol. 2014, 255, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Contreras, S.; Navas-Martos, F.J.; Rodríguez-Liébana, J.A.; La Rubia, M.D. Effect of Olive Pit Reinforcement in Polylactic Acid Biocomposites on Environmental Degradation. Materials 2023, 16, 5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliche-Quesada, D.; Felipe-Sesé, M.A.; Infantes-Molina, A. Olive Stone Ash as Secondary Raw Material for Fired Clay Bricks. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2016, 8219437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnahhal, M.; Alengaram, U.; Jumaat, M.; Alqedra, M.; Mo, K.; Sumesh, M. Evaluation of Industrial By-Products as Sustainable Pozzolanic Materials in Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Sustainability 2017, 9, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, M.A.; Kim, K.-H.; Park, J.-W.; Deep, A. Hydrolytic degradation of polylactic acid (PLA) and its composites. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.P.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Studies on durability of sustainable biobased composites: A review. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 17955–17999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-López, M.E.; Martín del Campo, A.S.; Robledo-Ortíz, J.R.; Arellano, M.; Pérez-Fonseca, A.A. Accelerated weathering of poly(lactic acid) and its biocomposites: A review. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 179, 109290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomakin, S.; Mikheev, Y.; Usachev, S.; Rogovina, S.; Zhorina, L.; Perepelitsina, E.; Levina, I.; Kuznetsova, O.; Shilkina, N.; Iordanskii, A.; et al. Evaluation and Modeling of Polylactide Photodegradation under Ultraviolet Irradiation: Bio-Based Polyester Photolysis Mechanism. Polymers 2024, 16, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hua, X.; Wu, H. Degradation Behavior of Poly (Lactic Acid) during Accelerated Photo-Oxidation: Insights into Structural Evolution and Mechanical Properties. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 3810–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnik, E.; Briassoulis, D. Degradation behaviour of poly(lactic acid) films and fibres in soil under Mediterranean field conditions and laboratory simulations testing. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 33, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiridon, I.; Darie, R.N.; Kangas, H. Influence of fiber modifications on PLA/fiber composites. Behavior to accelerated weathering. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 92, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaskova-Kuzmina, T.; Starkova, O.; Gaidukovs, S.; Platnieks, O.; Gaidukova, G. Durability of Biodegradable Polymer Nanocomposites. Polymers 2021, 13, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yebra-Rodríguez, A.; Fernández-Barranco, C.; La Rubia, M.D.; Yebra, A.; Rodríguez-Navarro, A.B.; Jiménez-Millán, J. Thermooxidative degradation of injection-moulded sepiolite/polyamide 66 nanocomposites. Mineral. Mag. 2014, 78, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 4892-2; Plastics—Methods of Exposure to Laboratory Light Sources. Technol Report; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Pickett, J.E. Weathering of Plastics. In Handbook of Environmental Degradation of Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Chapter 8; pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.W.; Saunders, S.C.; Floyd, F.L.; Wineburg, J.P. Methodologies for predicting the Service Lives of Coating Systems; Technol Report; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, L.A.; Meeker, W.Q. A Review of Accelerated Test Models. Stat. Sci. 2006, 21, 552–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Barranco, C.; Yebra-Rodríguez, A.; Jiménez-Millán, J.; Navas-Martos, F.J.; Yebra, A.; Koziol, A.E.; La Rubia, M.D. Photo-oxidative degradation of injection molded sepiolite/polyamide66 nanocomposites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 189, 105545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachino-Fagalde, E.; Rubia, M.D.L.; Jurado-Contreras, S. Fabricación y Caracterización de Composites de Ácido Poliláctico y Cenizas de Hueso de Aceituna; Universidad de Jaén: Jaén, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc, J.L. Filled Polymers: Science and Industrial Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 527-2:2012; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 2: Test Conditions for Moulding and Extrusion Plastics. Technol Report; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Q-Lab Corporation. A Choice of Filters for Q-SUN Xenon Test Chambers; Q-Lab Corporation: Westlake, OH, USA, 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 527-1:2019; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 1: General Principles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Bigg, D.M. Mechanical properties of particulate filled polymers. Polym. Compos. 1987, 8, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Jones, F.R. A review of particulate reinforcement theories for polymer composites. J. Mater. Sci. 1990, 25, 4933–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen. Ann. Phys. 1905, 322, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, H.M. Limiting Law of the Reinforcement of Rubber. J. Appl. Phys. 1944, 15, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, E. Theory of Filler Reinforcement. J. Appl. Phys. 1945, 16, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, M. The viscosity of a concentrated suspension of spherical particles. J. Colloid Sci. 1951, 6, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, N.; Acrivos, A. On the viscosity of a concentrated suspension of solid spheres. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1967, 22, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerner, E.H. The elastic and Thermo-elastic properties of composite media. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. B 1956, 69, 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.W. Strength theories of filamentary structures. In Fundamental Aspects of Fiber Reinforced Plastic Composites; Schwartz, R.T., Schwartz, H.S., Eds.; Interscience Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Halpin, J.C. Effects of Environmental Factors on Composite Materials. In Technical Report AFML-TR-67–423; Defense Technical Information Center: Dayton, OH, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Halpin, J. Stiffness and Expansion Estimates for Oriented Short Fiber Composites. J. Compos. Mater. 1969, 3, 732–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.E. Generalized Equation for the Elastic Moduli of Composite Materials. J. Appl. Phys. 1970, 41, 4626–4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landel, R.F.; Nielsen, L.E. Mechanical Properties of Polymers and Composites; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurson, A.L. Continuum Theory of Ductile Rupture by Void Nucleation and Growth: Part I—Yield Criteria and Flow Rules for Porous Ductile Media. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1977, 99, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvergaard, V.; Needleman, A. Analysis of the cup-cone fracture in a round tensile bar. Acta Metall. 1984, 32, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gologanu, M.; Leblond, J.-B.; Devaux, J. Approximate models for ductile metals containing non-spherical voids—Case of axisymmetric prolate ellipsoidal cavities. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1993, 41, 1723–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshelby, J.D. The determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion, and related problems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1957, 241, 376–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monchiet, V.; Charkaluk, E.; Kondo, D. Macroscopic yield criteria for ductile materials containing spheroidal voids: An Eshelby-like velocity fields approach. Mech. Mater. 2014, 72, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monchiet, V.; Cazacu, O.; Charkaluk, E.; Kondo, D. Macroscopic yield criteria for plastic anisotropic materials containing spheroidal voids. Int. J. Plast. 2008, 24, 1158–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keralavarma, S.; Benzerga, A. A constitutive model for plastically anisotropic solids with non-spherical voids. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2010, 58, 874–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeri, A.; Bucknall, C.B. Dilatational bands in rubber-toughened polymers. J. Mater. Sci. 1993, 28, 6799–6808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.-Y.; Pan, J. A macroscopic constitutive law for porous solids with pressure-sensitive matrices and its implications to plastic flow localization. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1995, 32, 3669–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Faleskog, J.; Shih, C. Continuum modeling of a porous solid with pressure-sensitive dilatant matrix. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2008, 56, 2188–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthélémy, J.-F.; Dormieux, L. Détermination du critère de rupture macroscopique d’un milieu poreux par homogénéisation non linéaire. Comptes Rendus Mec. 2003, 331, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Zhang, J.; Shao, J.; Kondo, D. Approximate macroscopic yield criteria for Drucker-Prager type solids with spheroidal voids. Int. J. Plast. 2017, 99, 221–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Shao, J.; Liu, Z.; Oueslati, A.; De Saxcé, G. Evaluation and improvement of macroscopic yield criteria of porous media having a Drucker-Prager matrix. Int. J. Plast. 2020, 126, 102609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/CIE 11664-4:2019; Colorimetry—Part 4: CIE 1976 L*a*b* Colour Space. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO Standard 2813:2014; Paints and Varnishes—Determination of Gloss Value at 20°, 60° and 85°. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Almond, J.; Sugumaar, P.; Wenzel, M.N.; Hill, G.; Wallis, C. Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. e-Polymers 2020, 20, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.H.; Badzinski, T.D.; Pardoe, E.; Ehlebracht, M.; Maurer-Jones, M.A. UV Light Degradation of Polylactic Acid Kickstarts Enzymatic Hydrolysis. ACS Mater. Au 2024, 4, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.W.; Sterzel, H.J.; Wegner, G. Investigation of the structure of solution grown crystals of lactide copolymers by means of chemical reactions. Kolloid-Z. Z. Polym. 1973, 251, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, C.D. Kinetic analysis of thermogravimetric data. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1961, 5, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.K.; Sivasubramanian, M.S. Integral approximations for nonisothermal kinetics. AIChE J. 1987, 33, 1212–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi-Kahrizsangi, R.; Abbasi, M. Evaluation of reliability of Coats-Redfern method for kinetic analysis of non-isothermal TGA. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2008, 18, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Lai, K.-M.; Lin, Y.-C. Methods for Determining the Kinetic Parameters from Nonisothermal Thermogravimetry: A Comparison of Reliability. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 2004, 37, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Burnham, A.K.; Criado, J.M.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Popescu, C.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for performing kinetic computations on thermal analysis data. Thermochim. Acta 2011, 520, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. Highly Accelerated UV Weathering: When and How to Use it. In Service Life Prediction of Polymers and Plastics Exposed to Outdoor Weathering; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2018; Chapter 6; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, J.E.; White, K.M.; White, C.C. Service Life Prediction: Why Is This so Hard? In Service Life Prediction of Polymers and Plastics Exposed to Outdoor Weathering; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, J.; Gardner, M. Reproducibility of Florida weathering data. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2005, 90, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laycock, B.; Nikolić, M.; Colwell, J.M.; Gauthier, E.; Halley, P.; Bottle, S.; George, G. Lifetime prediction of biodegradable polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 71, 144–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranakoti, L.; Gangil, B.; Mishra, S.K.; Singh, T.; Sharma, S.; Ilyas, R.; El-Khatib, S. Critical Review on Polylactic Acid: Properties, Structure, Processing, Biocomposites, and Nanocomposites. Materials 2022, 15, 4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín del Campo, A.S.; Robledo-Ortíz, J.R.; Arellano, M.; Rabelero, M.; Pérez-Fonseca, A.A. Accelerated Weathering of Polylactic Acid/Agave Fiber Biocomposites and the Effect of Fiber–Matrix Adhesion. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, M.E.C.; Stares, S.L.; Barra, G.M.d.O.; Hotza, D. Effects of accelerated weathering on properties of 3D-printed PLA scaffolds. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, M.; Dashatan, S.; Zhang, Z.; Dhakal, H.N.; Khalfallah, M.; Gamer, N.; Ling, J. Inorganic Fillers and Their Effects on the Properties of Flax/PLA Composites after UV Degradation. Polymers 2023, 15, 3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nezafatkhah, S.; Margoto, O.H.; Sassani, F.; Milani, A.S. Understanding natural and accelerated weathering degradation mechanisms of glass and natural fiber composites: A review. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasselet, D.; Ruellan, A.; Guinault, A.; Miquelard-Garnier, G.; Sollogoub, C.; Fayolle, B. Oxidative degradation of polylactide (PLA) and its effects on physical and mechanical properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 50, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaga, A.; Yamasaki, R.S. Surface microcracking induced by weathering of polycarbonate sheet. J. Mater. Sci. 1976, 11, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.-Y.; Feng, X.-Q.; Lauke, B.; Mai, Y.-W. Effects of particle size, particle/matrix interface adhesion and particle loading on mechanical properties of particulate–polymer composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2008, 39, 933–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siakeng, R.; Jawaid, M.; Asim, M.; Siengchin, S. Accelerated Weathering and Soil Burial Effect on Biodegradability, Colour and Textureof Coir/Pineapple Leaf Fibres/PLA Biocomposites. Polymers 2020, 12, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, S.; Eblagon, K.M.; Miranda, F.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Figueiredo, J.L. Towards Controlled Degradation of Poly(lactic) Acid in Technical Applications. C 2021, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Savino, I.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy to Assess the Degree of Alteration of Artificially Aged and Environmentally Weathered Microplastics. Polymers 2023, 15, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vašíček, A.; Lenfeld, P.; Běhálek, L. Degradation of Polylactic Acid Polymer and Biocomposites Exposed to Controlled Climatic Ageing: Mechanical and Thermal Properties and Structure. Polymers 2023, 15, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsavas, S.D.; Kaynak, C. Weathering degradation performance of PLA and its glass fiber reinforced composite. Mater. Today Commun. 2018, 15, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.; Popelka, A.; Aljarod, O.; Hassan, M.K.; Luyt, A.S. Effects of Rutile–TiO2 Nanoparticles on Accelerated Weathering Degradation of Poly(Lactic Acid). Polymers 2020, 12, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeArmit, C.; Hancock, M. Filled Thermoplastics. In Particulate-Filled Polymer Composites, 2nd ed.; Rothon, R.N., Ed.; RAPRA: Shropshire, UK, 2003; Chapter 8; pp. 357–424. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, L.E. The thermal and electrical conductivity of two-phase systems. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 1974, 13, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.E. Morphology and the elastic modulus of block polymers and polyblends. Rheol. Acta 1974, 13, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R. On the Lewis–Nielsen model for thermal/electrical conductivity of composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2008, 39, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arganda-Carreras, I.; Kaynig, V.; Rueden, C.; Eliceiri, K.W.; Schindelin, J.; Cardona, A.; Seung, H.S. Trainable Weka Segmentation: A machine learning tool for microscopy pixel classification. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2424–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GNU Octave (Version 6.4.0). Available online: https://www.gnu.org/software/octave/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Shin, F.G.; Tsui, W.L.; Yeung, Y.Y.; Au, W.M. Elastic properties of a solid with a dispersion of soft inclusions or voids. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 1993, 12, 1632–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancarella, F.; Style, R.W.; Wettlaufer, J.S. Surface tension and the Mori–Tanaka theory of non-dilute soft composite solids. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 472, 20150853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggeman, D.A.G. Berechnung verschiedener physikalischer Konstanten von heterogenen Substanzen. I. Dielektrizitätskonstanten und Leitfähigkeiten der Mischkörper aus isotropen Substanzen. Ann. Phys. 1935, 416, 636–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, J.K. The Elastic Constants of a Solid containing Spherical Holes. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. B 1950, 63, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshelby, J.D. The elastic field outside an ellipsoidal inclusion. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1959, 252, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, R. A study of the differential scheme for composite materials. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 1977, 15, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, A.; Callegari, A.; Sheng, P. A generalized differential effective medium theory. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1985, 33, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshelby, J. Elastic inclusions and inhomogeneities. In Collected Works of JD Eshelby; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 297–350. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, T.; Tanaka, K. Average stress in matrix and average elastic energy of materials with misfitting inclusions. Acta Metall. 1973, 21, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benveniste, Y. A new approach to the application of Mori-Tanaka’s theory in composite materials. Mech. Mater. 1987, 6, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavko, G.; Mukerji, T.; Dvorkin, J. The Rock Physics Handbook, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E.; Zimmerman, R. Compressibility and shear compliance of spheroidal pores: Exact derivation via the Eshelby tensor, and asymptotic expressions in limiting cases. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2011, 48, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevostianov, I.; Kachanov, M. Non-interaction Approximation in the Problem of Effective Properties. In Effective Properties of Heterogeneous Materials; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 1–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasanthan, N.; Ly, O. Effect of microstructure on hydrolytic degradation studies of poly (l-lactic acid) by FTIR spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2009, 94, 1364–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiansky, B.; O’connell, R.J. Elastic moduli of a cracked solid. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1976, 12, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, J. Phenomenological Aspects of Damage. In A Course on Damage Mechanics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, G.-H.; Jang, J. Surface modification of poly(lactic acid) by UV/Ozone irradiation. Fibers Polym. 2008, 9, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, C.; Sarı, B. Accelerated weathering performance of polylactide and its montmorillonite nanocomposite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 121–122, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M.; Abenojar, J.; Martínez, M.Á. Recent Progress in Hybrid Biocomposites: Mechanical Properties, Water Absorption, and Flame Retardancy. Materials 2020, 13, 5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lactic Acid|C3H6O3|CID 612—PubChem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Lactic-Acid (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Chieng, B.; Ibrahim, N.; Yunus, W.; Hussein, M. Poly(lactic acid)/Poly(ethylene glycol) Polymer Nanocomposites: Effects of Graphene Nanoplatelets. Polymers 2013, 6, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, C.; Dogu, B. Effects of Accelerated Weathering in Polylactide Biocomposites Reinforced with Microcrystalline Cellulose. Int. Polym. Process. 2016, 31, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Pande, K.; Puranam, P.; Deshmukh, A.D.; Bhone, A.; Kale, R.; Galande, A.; Mehtre, B.; Tagad, J.; Tidake, S. Explication of mechanism governing atmospheric degradation of 3D-printed poly(lactic acid) (PLA) with different in-fill pattern and varying in-fill density. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 7135–7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Jia, W.; Huang, K.; Ma, Y. Comparing the Aging Processes of PLA and PE: The Impact of UV Irradiation and Water. Processes 2024, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaaba, N.F.; Jaafar, M. A review on degradation mechanisms of polylactic acid: Hydrolytic, photodegradative, microbial, and enzymatic degradation. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2020, 60, 2061–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awale, R.; Ali, F.; Azmi, A.; Puad, N.; Anuar, H.; Hassan, A. Enhanced Flexibility of Biodegradable Polylactic Acid/Starch Blends Using Epoxidized Palm Oil as Plasticizer. Polymers 2018, 10, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetjes, V.; Zarges, J.-C.; Heim, H.-P. Differentiation between Hydrolytic and Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of Poly(lactic acid) and Poly(lactic acid)/Starch Composites in Warm and Humid Environments. Materials 2024, 17, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-León, J.R.; Rodríguez-Félix, D.E.; Quiroz-Castillo, J.M.; Burrola-Núñez, H.; Castillo-Ortega, M.M.; Encinas-Encinas, J.C.; Alvarado-Ibarra, J.; Santacruz-Ortega, H.; Valenzuela-García, J.L.; Herrera-Franco, P.J. Effect of Degradation on the Physicochemical and Mechanical Properties of Extruded Films of Poly(lactic acid) and Chitosan. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 9526–9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conterosito, E.; Roncoli, M.; Ivaldi, C.; Ferretti, M.; De Felice, B.; Parolini, M.; Gazzotti, S.; Ortenzi, M.A.; Gianotti, V. μ-FTIR Reflectance Spectroscopy Coupled with Multivariate Analysis: A Rapid and Robust Method for Identifying the Extent of Photodegradation on Microplastics. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 3263–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgun, E.; Ali, A.; Islam, M.S. Biocomposites of Poly(Lactic Acid) and Microcrystalline Cellulose: Influence of the Coupling Agent on Thermomechanical and Absorption Characteristics. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 11523–11533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, K.; Cuiffi, J.D.; Mathers, R.T. Ranking environmental degradation trends of plastic marine debris based on physical properties and molecular structure. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awaja, F.; Zhang, S.; Tripathi, M.; Nikiforov, A.; Pugno, N. Cracks, microcracks and fracture in polymer structures: Formation, detection, autonomic repair. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2016, 83, 536–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysiukiewicz, O.; Barczewski, M.; Skórczewska, K.; Szulc, J.; Kloziński, A. Accelerated Weathering of Polylactide-Based Composites Filled with Linseed Cake: The Influence of Time and Oil Content within the Filler. Polymers 2019, 11, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Investigation of Polymers with Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Technol Report. Available online: https://polymerscience.physik.hu-berlin.de/docs/manuals/DSC.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Litauszki, K.; Kovács, Z.; Mészáros, L.; Kmetty, Á. Accelerated photodegradation of poly(lactic acid) with weathering test chamber and laser exposure – A comparative study. Polym. Test. 2019, 76, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, T. Effect of poly(lactic acid) crystallization on its mechanical and heat resistance performances. Polymer 2021, 212, 123280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadea, S.; Kittikorn, T.; Chollakup, R.; Hedthong, R.; Chumprasert, S.; Khanoonkon, N.; Witayakran, S.; Chatakanonda, P. Influences of epoxidized natural rubber and fiber modification on injection molded-pulp/poly(lactic acid) biocomposites: Analysis of mechanical-thermal and weathering stability. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 201, 116909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczewski, M.; Andrzejewski, J.; Matykiewicz, D.; Krygier, A.; Klozinski, A. Influence of accelerated weathering on mechanical and thermomechanical properties of poly(lactic acid) composites with natural waste filler. Polimery 2019, 64, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.; Nikaeen, P.; Chirdon, W.; Khattab, A.; Depan, D. Improved Weathering Performance of Poly(Lactic Acid) through Carbon Nanotubes Addition: Thermal, Microstructural, and Nanomechanical Analyses. Biomimetics 2020, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, V.; Zhang, K.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Overcoming the Fundamental Challenges in Improving the Impact Strength and Crystallinity of PLA Biocomposites: Influence of Nucleating Agent and Mold Temperature. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 11203–11214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grza̧bka-Zasadzińska, A.; Pia̧tek, A.; Klapiszewski, Ł.; Borysiak, S. Structure and Properties of Polylactide Composites with TiO2–Lignin Hybrid Fillers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiridon, I.; Leluk, K.; Resmerita, A.M.; Darie, R.N. Evaluation of PLA–lignin bioplastics properties before and after accelerated weathering. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 69, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergaliyeva, S.; Sales, D.L.; Delgado, F.J.; Bolegenova, S.; Molina, S.I. Manufacture and Characterization of Polylactic Acid Filaments Recycled from Real Waste for 3D Printing. Polymers 2023, 15, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatigala, N.S.; Bajwa, D.S.; Bajwa, S.G. Compatibilization Improves Performance of Biodegradable Biopolymer Composites Without Affecting UV Weathering Characteristics. J. Polym. Environ. 2018, 26, 4188–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Liu, G.; Sun, H.; Yang, B.; Weng, Y. Effect of Biomass as Nucleating Agents on Crystallization Behavior of Polylactic Acid. Polymers 2022, 14, 4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Masato, D. The Effects of Nucleating Agents and Processing on the Crystallization and Mechanical Properties of Polylactic Acid: A Review. Micromachines 2024, 15, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouchiar, S.; Stoclet, G.; Cabaret, C.; Gloaguen, V. Influence of the Filler Nature on the Crystalline Structure of Polylactide-Based Nanocomposites: New Insights into the Nucleating Effect. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 2782–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.M.; Saidi, N.M.; Omar, F.S.; Ramesh, K.; Ramesh, S.; Bashir, S. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Polymers. In Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muravyev, N.V.; Pivkina, A.N.; Koga, N. Critical Appraisal of Kinetic Calculation Methods Applied to Overlapping Multistep Reactions. Molecules 2019, 24, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondarchuk, I.; Bondarchuk, S.; Vorozhtsov, A.; Zhukov, A. Advanced Fitting Method for the Kinetic Analysis of Thermogravimetric Data. Molecules 2023, 28, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhulaybi, Z.; Dubdub, I.; Al-Yaari, M.; Almithn, A.; Al-Naim, A.F.; Aljanubi, H. Pyrolysis Kinetic Study of Polylactic Acid. Polymers 2022, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, B. The Avrami Equation: Phase Transformations. In The Equations of Materials; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; Chapter 9; pp. 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reit, M.; Zarges, J.; Heim, H. Correlation between the activation energy of PLA respectively PLA/starch composites and mechanical properties with regard to differ accelerated aging conditions. Biopolymers 2024, 115, e23571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, K.; Klonos, P.A.; Kyritsis, A.; Tarani, E.; Chrissafis, K.; Mašek, O.; Tsachouridis, K.; Anastasiou, A.D.; Bikiaris, D.N. Synthesis and Characterization of PLA/Biochar Bio-Composites Containing Different Biochar Types and Content. Polymers 2025, 17, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzad, K.; Viney, C. A critical review on applications of the Avrami equation beyond materials science. J. R. Soc. Interface 2023, 20, 20230242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Charpak, Y.D.; Trabold, T.A.; Lewis, C.L.; Diaz, C.A. Biochar-filled plastics: Effect of feedstock on thermal and mechanical properties. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 12, 4349–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenko, M.; Stetsyshyn, Y.; Harhay, K.; Melnyk, Y.; Donchak, V.; Khomyak, S.; Ivanukh, O.; Kracalik, M. Impact of the functionalized clay on the poly(lactic acid)/polybutylene adipate terephthalate (PLA/PBAT) based biodegradable nanocomposites: Thermal and rheological properties. Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 278, 108020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D.R. Interpreting weathering acceleration factors for automotive coatings using exposure models. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2000, 69, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.W.; Chin, J.W.; Nguyen, T. Reciprocity law experiments in polymeric photodegradation: A critical review. Prog. Org. Coatings 2003, 47, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, J.E.; Coyle, D.J. Hydrolysis kinetics of condensation polymers under humidity aging conditions. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2013, 98, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 877-1:2009; Plastics—Methods of Exposure to Solar Radiation—Part 1: General Guidance. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

| Parameter | Method/Standard | Value | Uncertainty | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total humidity | UNE-EN ISO 18134-1:2023 | 10.8 | ±0.3 | % m/m (1) |

| Ashes | ISO 18122:2022 | 0.6 | ±0.2 | % m/m (2) |

| Bulk density | UNE-EN ISO 17828:2016 | 780 | ±40 | kg/m3 (1) |

| Oil and fat content * | Internal procedure based on UNE EN ISO 659 | 0.31 | – | % m/m (1) |

| Elemental Analysis | ||||

| Carbon | UNE-EN ISO 16948:2015 Instrumental method | 50.3 | ±3.5 | % m/m (2) |

| Hydrogen | 6.5 | ±0.9 | % m/m (2) | |

| Nitrogen | 0.28 | ±0.04 | % m/m (2) | |

| Sulfur | UNE-EN ISO 16994:2017 | 0.024 | ±0.008 | % m/m (2) |

| Chlorine | Combustion method and ion chromatography | 0.019 | ±0.007 | % m/m (2) |

| Oxygen * | Calculated | 42.4 | – | % m/m (2) |

| Energy Analysis | ||||

| Gross Calorific Value corrected to constant volume (GCVV) | UNE-EN ISO 18125:2018 | 20.9 | ±0.4 | MJ/kg (2) |

| Net Calorific Value to constant pressure (NCVP) | 19.5 | ±0.4 | MJ/kg (2) | |

| 17.2 | ±0.9 | MJ/kg (1) | ||

| 4.8 | ±0.3 | kWh/kg (1) | ||

| Exposure Site | Miami | Phoenix | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tilt angle 1 | ||||

| TUV (MJ/m2) | 340 ± 16 | 325 ± 17 | 376 ± 32 | 366 ± 30 |

| T (°C) | 24.4 ± 1.2 | 24.3 ± 1.7 | ||

| RH (%) | 79.5 ± 2.9 | 33.8 ± 5.3 | ||

| Material | Exposure Time (h) | Conditioned Mass (g) | Dry Mass 1 (g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | Initial | Final | ||

| PLAs | 0 | 1.2899 ± 0.0030 | - | 1.2884 ± 0.0030 | - |

| 500 | 1.2902 ± 0.0021 | 1.2893 ± 0.0021 | 1.2886 ± 0.0021 | 1.2823 ± 0.0021 | |

| 1000 | 1.2897 ± 0.0039 | 1.2904 ± 0.0037 | 1.2881 ± 0.0039 | 1.2821 ± 0.0037 | |

| PLAb1 | 0 | 1.2951 ± 0.0041 | - | 1.2853 ± 0.0040 | - |

| 500 | 1.2916 ± 0.0023 | 1.2930 ± 0.0018 | 1.2819 ± 0.0023 | 1.2792 ± 0.0017 | |

| 1000 | 1.2983 ± 0.0041 | 1.2939 ± 0.0034 | 1.2885 ± 0.0041 | 1.2777 ± 0.0034 | |

| PLAb3 | 0 | 1.3175 ± 0.0038 | - | 1.2565 ± 0.0036 | - |

| 500 | 1.3173 ± 0.0041 | 1.3162 ± 0.0036 | 1.2563 ± 0.0039 | 1.2257 ± 0.0034 | |

| 1000 | 1.3169 ± 0.0039 | 1.3078 ± 0.0081 | 1.2558 ± 0.0038 | 1.1990 ± 0.0075 | |

| Material | Exposure Time (h) | Bulk Mechanical Properties | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E (GPa) | (MPa) | (%) | ||

| PLAs | 0 | 3.48 ± 0.11 | 62.4 ± 0.6 | 1.79 ± 0.05 |

| 500 | 3.41 ± 0.08 | 51.6 ± 2.9 | 1.51 ± 0.18 | |

| 1000 | 3.35 ± 0.14 | 40.5 ± 2.5 | 1.21 ± 0.17 | |

| PLAb1 | 0 | 3.39 ± 0.12 | 49.0 ± 2.0 | 1.44 ± 0.29 |

| 500 | 3.29 ± 0.13 | 36.9 ± 1.1 | 1.12 ± 0.04 | |

| 1000 | 3.22 ± 0.08 | 25.6 ± 2.3 | 0.80 ± 0.16 | |

| PLAb3 | 0 | 3.13 ± 0.16 | 32.3 ± 1.9 | 1.03 ± 0.06 |

| 500 | 3.01 ± 0.19 | 24.9 ± 2.5 | 0.83 ± 0.07 | |

| 1000 | 2.93 ± 0.17 | 16.1 ± 2.3 | 0.55 ± 0.09 | |

| Material | Exposure Time (h) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PLAs | 0 | – | – |

| 500 | 1.14 | ||

| 1000 | 2.21 | ||

| PLAb1 | 0 | 1.24 | – |

| 500 | 1.78 | ||

| 1000 | 3.18 | ||

| PLAb3 | 0 | 5.54 | – |

| 500 | 2.21 | ||

| 1000 | 3.93 |

| Material | Exposure Time (h) | Yield Criterion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLAs | 0 | Von Mises | – | – |

| 500 | ||||

| 1000 | ||||

| PLAb1 | 0 | Drucker-Prager | 0.256 | 37.5 |

| 500 | 0.218 | 33.2 | ||

| 1000 | 0.189 | 29.6 | ||

| PLAb3 | 0 | Drucker-Prager | 0.799 | 67.4 |

| 500 | 0.551 | 58.8 | ||

| 1000 | 0.364 | 47.5 |

| Material | Exposure Time (h) | Color Coordinates | Total Coordinate Gradient | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLAs | 0 | 72.88 | −0.02 | 10.65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 500 | 67.59 | −0.06 | 8.42 | −5.29 | −0.04 | −2.23 | 5.74 | |

| 1000 | 62.30 | −0.13 | 4.33 | −10.58 | −0.11 | −6.32 | 12.32 | |

| PLAb1 | 0 | 31.15 | 2.03 | 4.44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 500 | 36.51 | 0.96 | 1.90 | 5.36 | −1.07 | −2.54 | 6.03 | |

| 1000 | 46.52 | −0.25 | −1.06 | 15.37 | −2.28 | −5.50 | 16.48 | |

| PLAb2 | 0 | 25.16 | 0.25 | −0.12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 500 | 31.58 | −0.05 | −0.55 | 6.42 | −0.30 | −0.43 | 6.44 | |

| 1000 | 48.89 | −0.24 | −0.86 | 23.73 | −0.49 | −0.74 | 23.75 | |

| Material | Exposure Time (h) | Surface Gloss (GU) |

|---|---|---|

| PLAs | 0 | 52.5 ± 0.5 |

| 500 | 38.7 ± 1.4 | |

| 1000 | 25.0 ± 2.2 | |

| PLAb1 | 0 | 47.1 ± 1.8 |

| 500 | 41.0 ± 1.1 | |

| 1000 | 35.5 ± 0.6 | |

| PLAb3 | 0 | 27.0 ± 1.7 |

| 500 | 22.9 ± 2.1 | |

| 1000 | 18.8 ± 1.7 |

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Assignment | Degradation Process |

|---|---|---|

| 3100–3700 | O–H stretching | Hydrolysis (COOH, OH end groups) |

| 2800–3000 | C–H stretching (CH, CH2, CH3) | Backbone structure |

| 1748 | C=O stretching (Ester in PLA backbone) | Ester bond

cleavage (hydrolysis, photolysis) |

| 1647 | C=C stretching (vinyl end groups) | Photolysis (Norrish Type II) |

| 1452 | C–H bending/deformation (CH2) | Backbone structure |

| 1383 | C–H bending/deformation (CH3) | Side group structure; thermo-oxidative changes |

| 1358 | ||

| 1000–1300 | C–O stretching (ester C–O–C), C–C stretching | Ester bond cleavage, formation of new end groups, structural changes |

| 955 | Skeletal vibrations | Amorphous phase |

| 921 | Skeletal vibrations CH3 rocking | Crystalline phase contribution (-crystals) |

| 868 | C–C Stretching | Backbone structure |

| Material | Exposure Time (h) | CI | HI |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLAs | 0 | 5.98 | 0.38 |

| 500 | 6.04 | 1.43 | |

| 1000 | 6.12 | 2.80 | |

| PLAb1 | 0 | 5.99 | 0.45 |

| 500 | 5.72 | 2.11 | |

| 1000 | 4.17 | 3.19 | |

| PLAb3 | 0 | 5.84 | 0.49 |

| 500 | 5.64 | 2.28 | |

| 1000 | 5.77 | 5.85 |

| Material | Exposure Time (h) | (°C) | (°C) | (°C) | (J/g) | (J/g) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLAs | 0 | 49.6 | – | 172.5 | – | 35.1 | 37.5 |

| 500 | 52.5 | – | 171.6 | – | 36.9 | 39.4 | |

| 1000 | 54.6 | – | 170.8 | – | 38.3 | 40.8 | |

| PLAb1 | 0 | 63.2 | 109.2 | 169.2 | 30.6 | 42.9 | 13.3 |

| 500 | 62.1 | 109.4 | 169.0 | 27.0 | 43.8 | 18.1 | |

| 1000 | 60.7 | 109.5 | 168.1 | 25.6 | 44.4 | 20.2 | |

| PLAb3 | 0 | 58.4 | 118.9 | 161.9 | 30.3 | 35.7 | 6.0 |

| 500 | 58.0 | 120.8 | 158.5 | 28.4 | 36.4 | 8.9 | |

| 1000 | 57.8 | 120.9 | 158.1 | 29.3 | 38.9 | 10.5 |

| Material | (kJ/mol) | () | n | RSS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLAs | 149.8 | 13.8 | 1.59 | 0.33 | 2.72 |

| PLAb1 | 136.5 | 8.4 | 1.12 | 0.66 | 5.13 |

| PLAb3 | 122.0 | 1.7 | 0.95 | 0.77 | 18.83 |

| Material | (°C) 1 | (°C) 2 |

|---|---|---|

| PLAs | 328.5 | 365.6 |

| PLAb1 | 271.4 | 319.5 |

| PLAb3 | 234.3 | 288.4 |

| Material | H (MJ/m2) | T (°C) | RH (%) | AF | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. | M. | P. | L. | M. | P. | L. | M. | P. | M. | P. | |

| PLAs | 1892 | 340 | 376 | 40 | 30 | 50 | 80 | 34 | 15 | 73 | |

| PLAb1 | 50 | 36 | 22 | 109 | |||||||

| PLAb3 | 60 | 42 | 27 | 135 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moya-Muriana, J.Á.; Navas-Martos, F.J.; Jurado-Contreras, S.; Bachino-Fagalde, E.; La Rubia, M.D. Effect of Olive Stone Biomass Ash Filler in Polylactic Acid Biocomposites on Accelerated Weathering Tests. Polymers 2026, 18, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010030

Moya-Muriana JÁ, Navas-Martos FJ, Jurado-Contreras S, Bachino-Fagalde E, La Rubia MD. Effect of Olive Stone Biomass Ash Filler in Polylactic Acid Biocomposites on Accelerated Weathering Tests. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoya-Muriana, José Ángel, Francisco J. Navas-Martos, Sofía Jurado-Contreras, Emilia Bachino-Fagalde, and M. Dolores La Rubia. 2026. "Effect of Olive Stone Biomass Ash Filler in Polylactic Acid Biocomposites on Accelerated Weathering Tests" Polymers 18, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010030

APA StyleMoya-Muriana, J. Á., Navas-Martos, F. J., Jurado-Contreras, S., Bachino-Fagalde, E., & La Rubia, M. D. (2026). Effect of Olive Stone Biomass Ash Filler in Polylactic Acid Biocomposites on Accelerated Weathering Tests. Polymers, 18(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010030