Zn–IMP 3D Coordination Polymers for Drug Delivery: Crystal Structure and Computational Studies †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Structural Characterization

2.2. Single-Crystal X-Ray Diffraction: Data Collection and Structure Solution

2.3. Computational Modeling: Docking, Interaction Fingerprints, and Multi-pH Molecular Dynamics

2.4. Data Handling and Analysis

2.5. Controls, Calibration and Additional Considerations

3. Results and Discussion

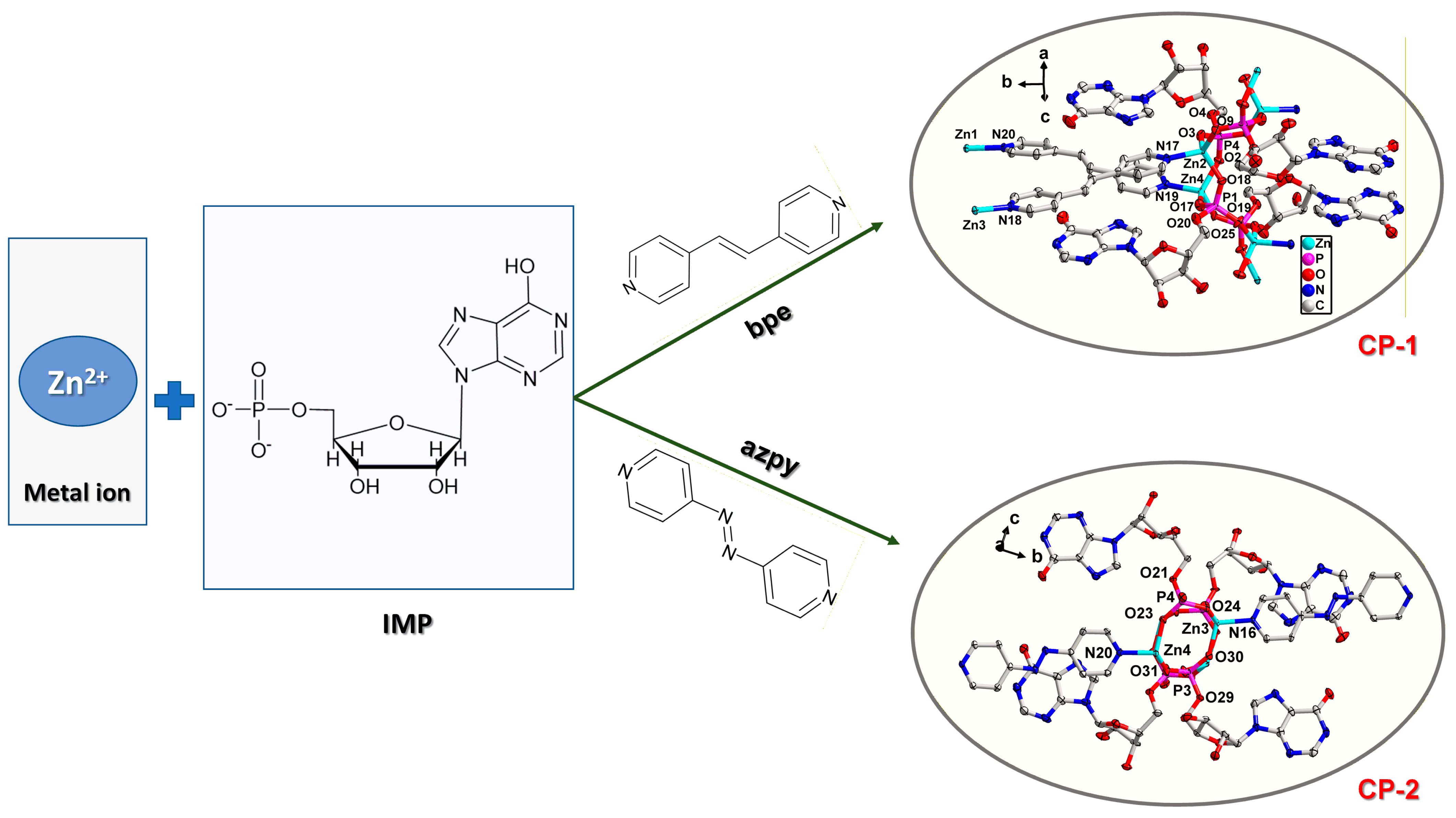

3.1. Design and Synthesis

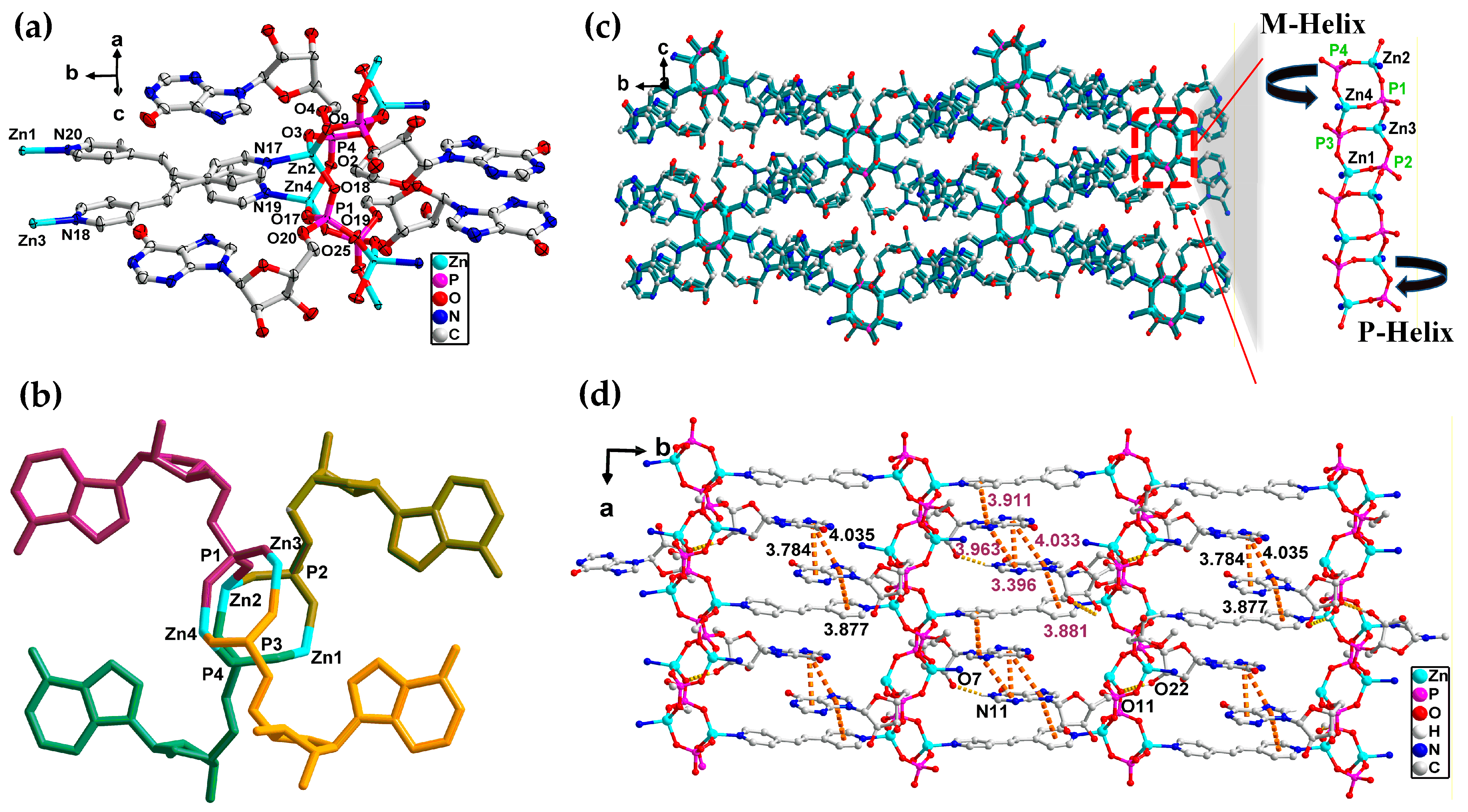

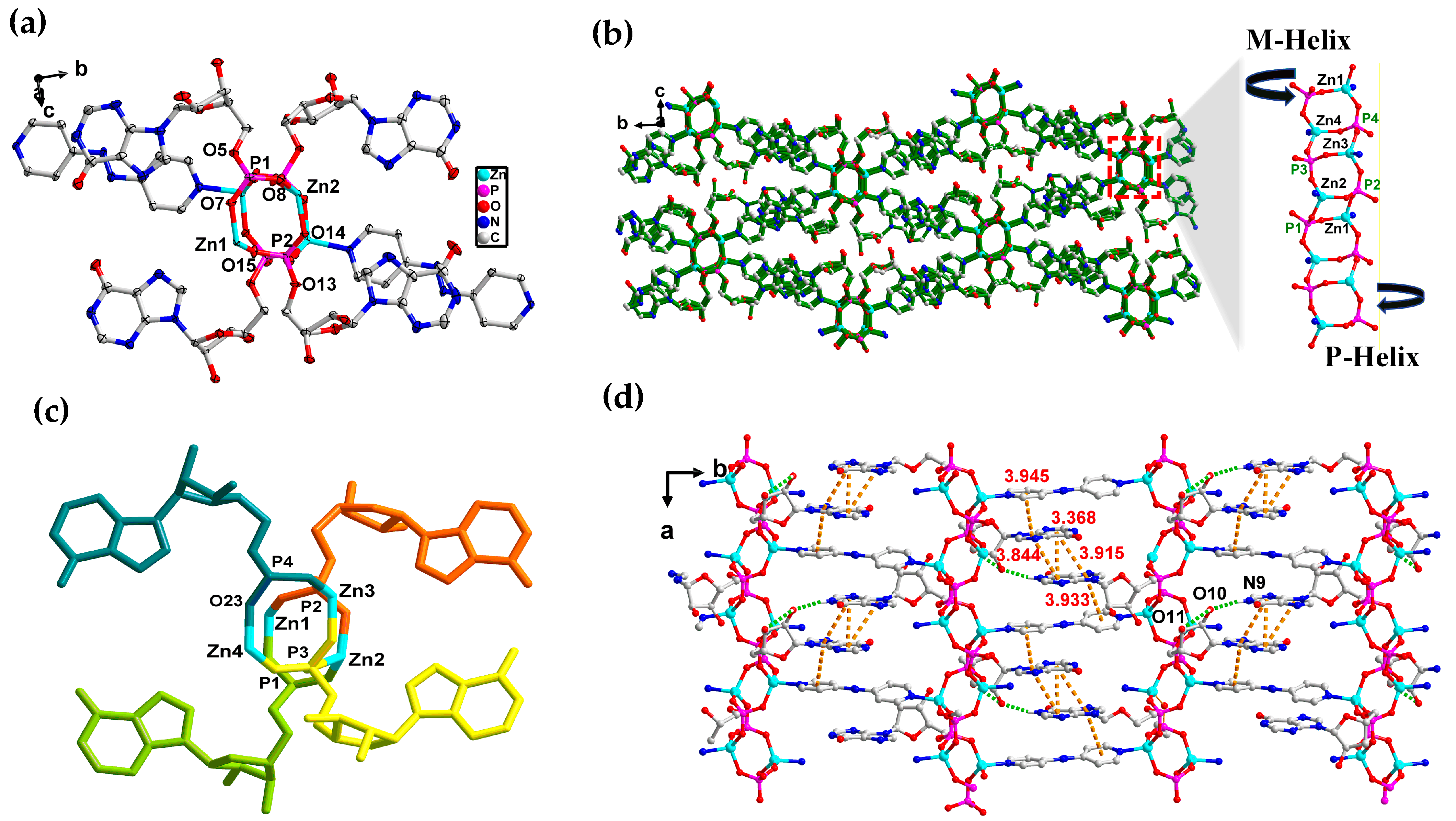

3.2. Crystal Structure

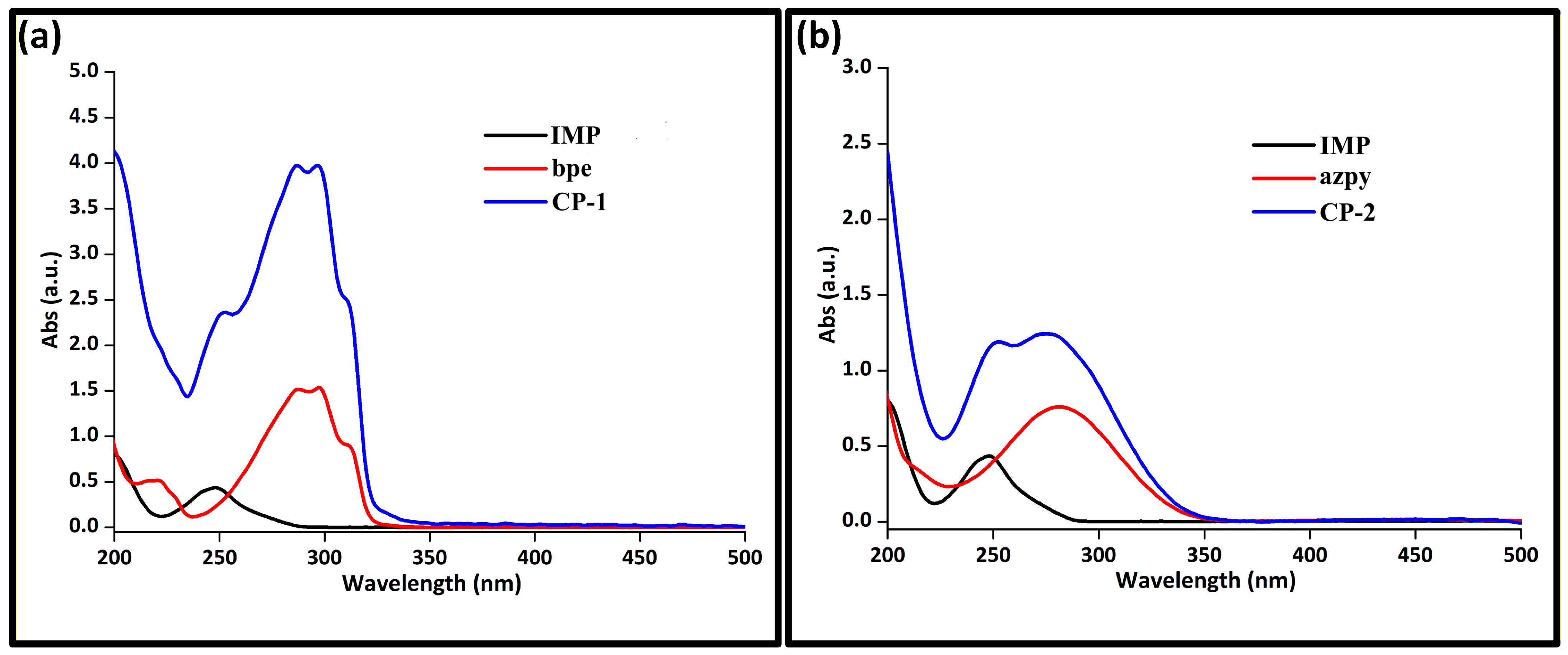

3.3. UV–Vis Spectroscopy

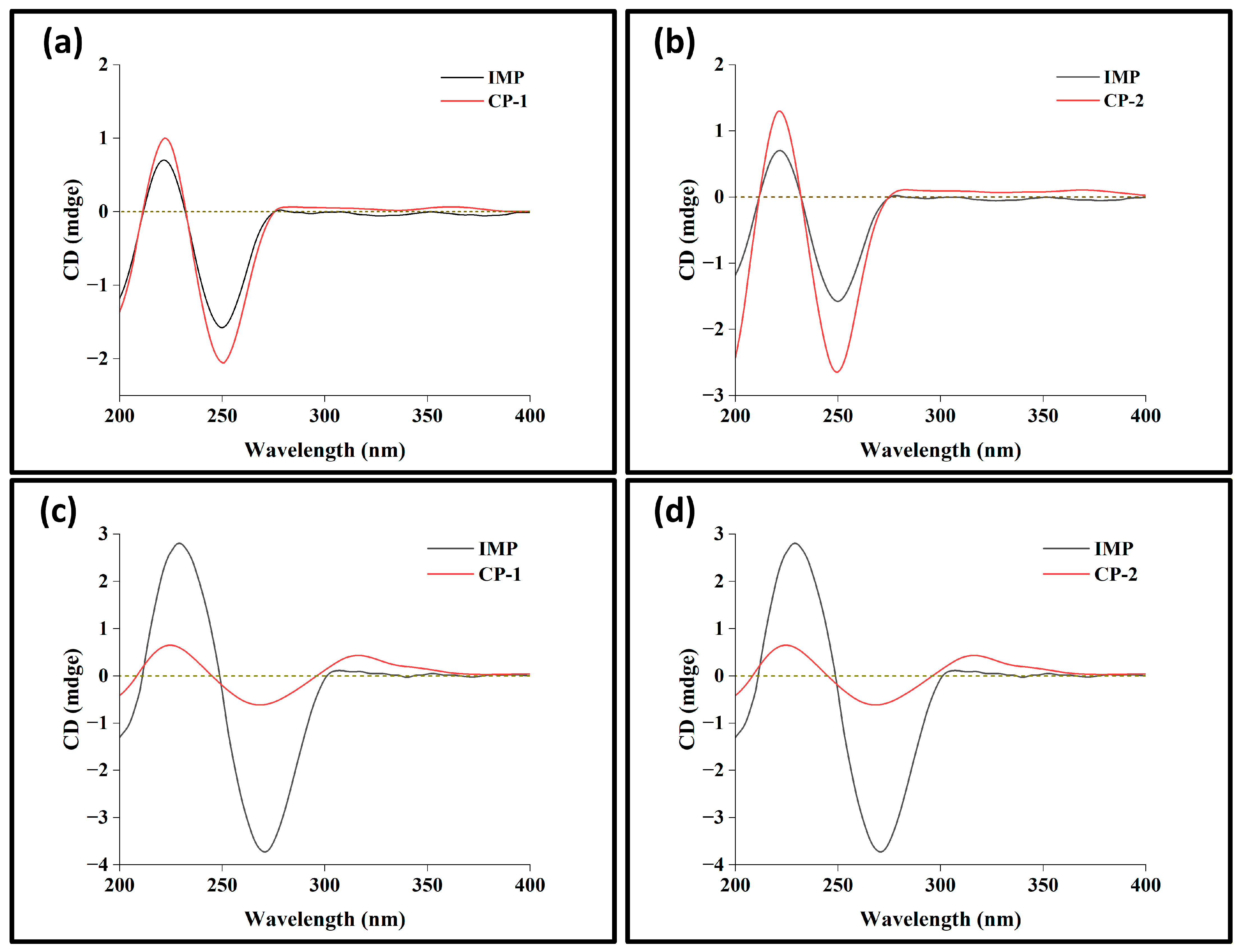

3.4. Solution-State Circular Dichroism

3.5. Solid-State Circular Dichroism

3.6. Chirality

3.7. FTIR Analysis

3.8. TGA

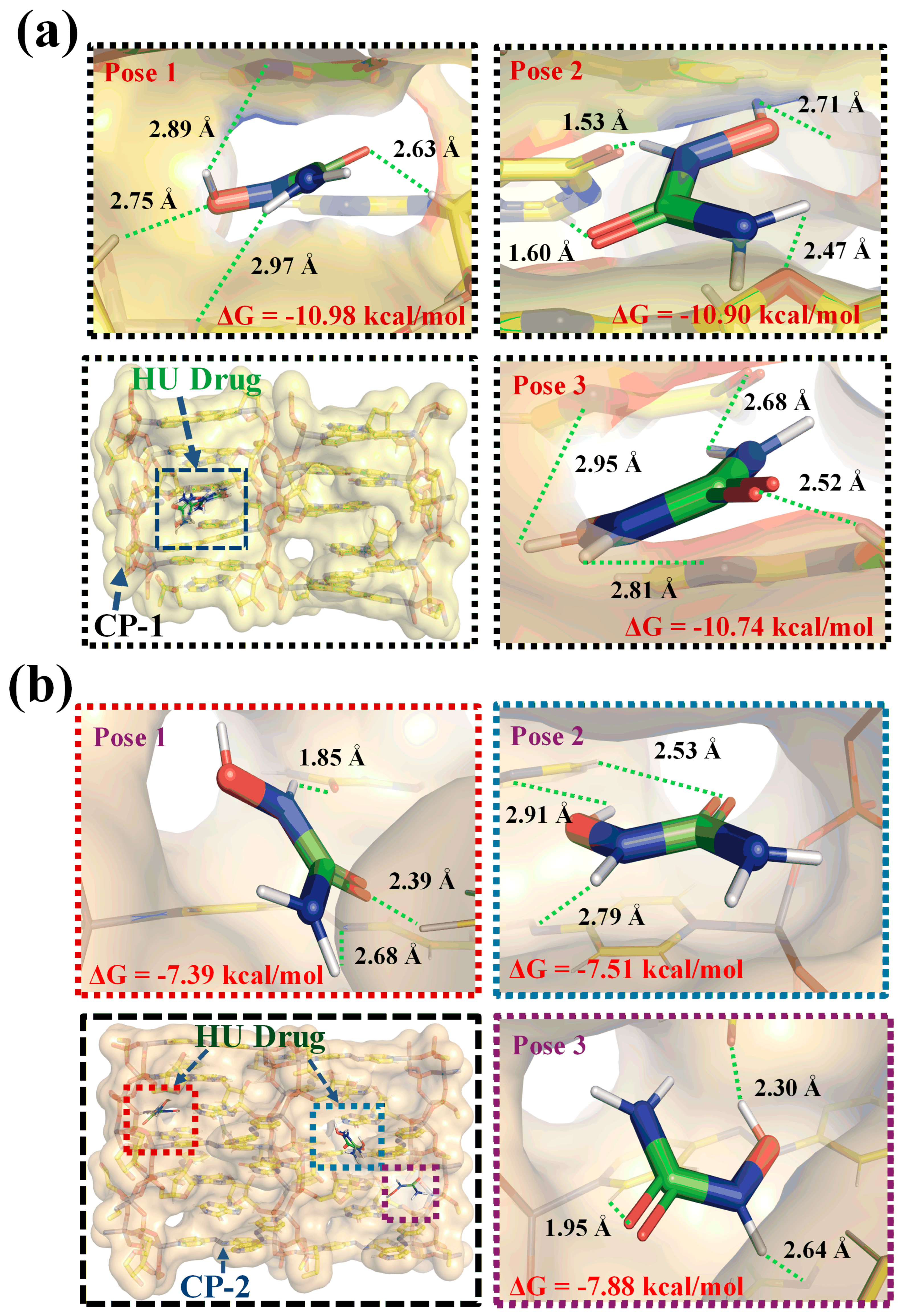

4. In Silico Studies

4.1. Hirshfielf Surface Analysis

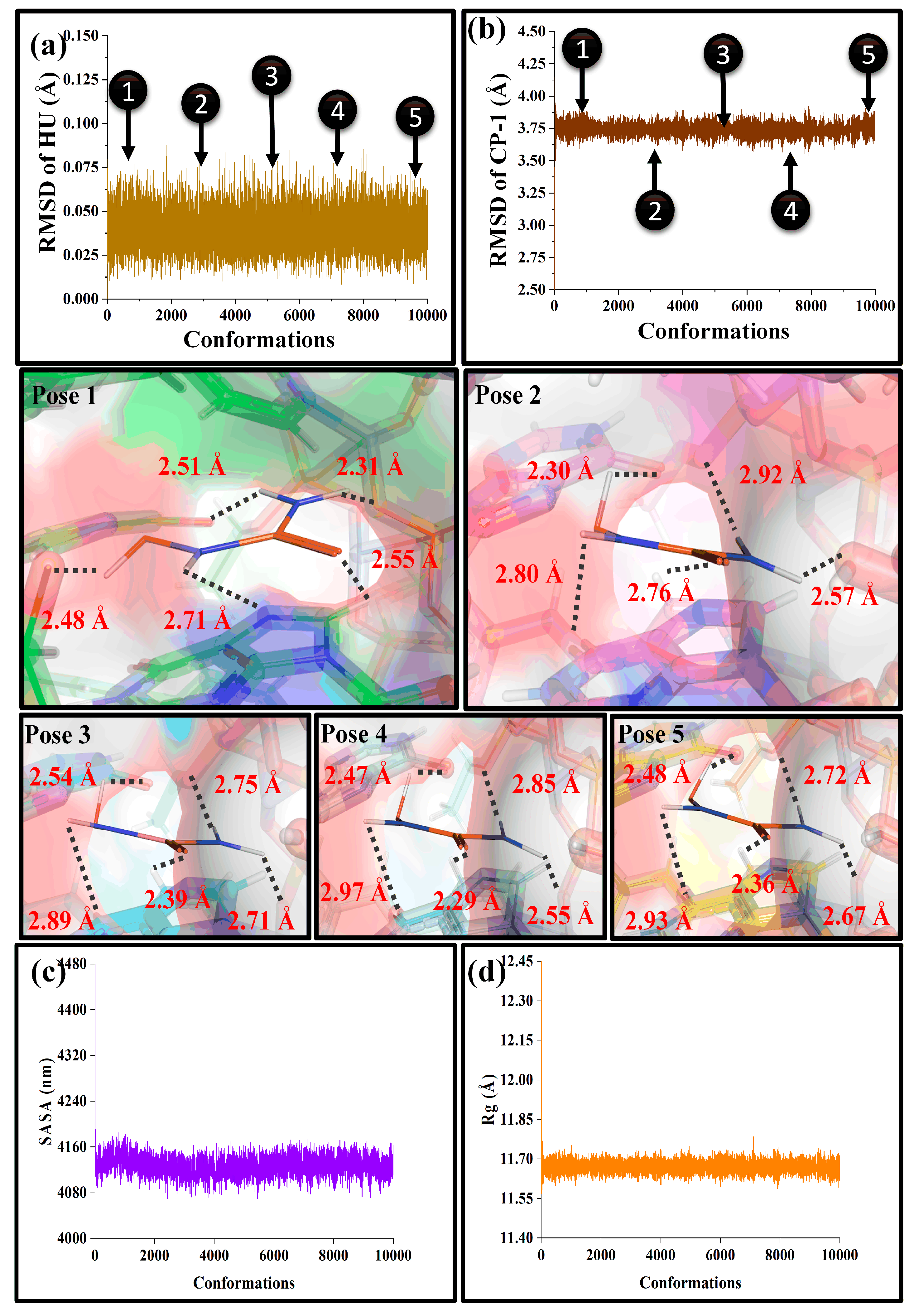

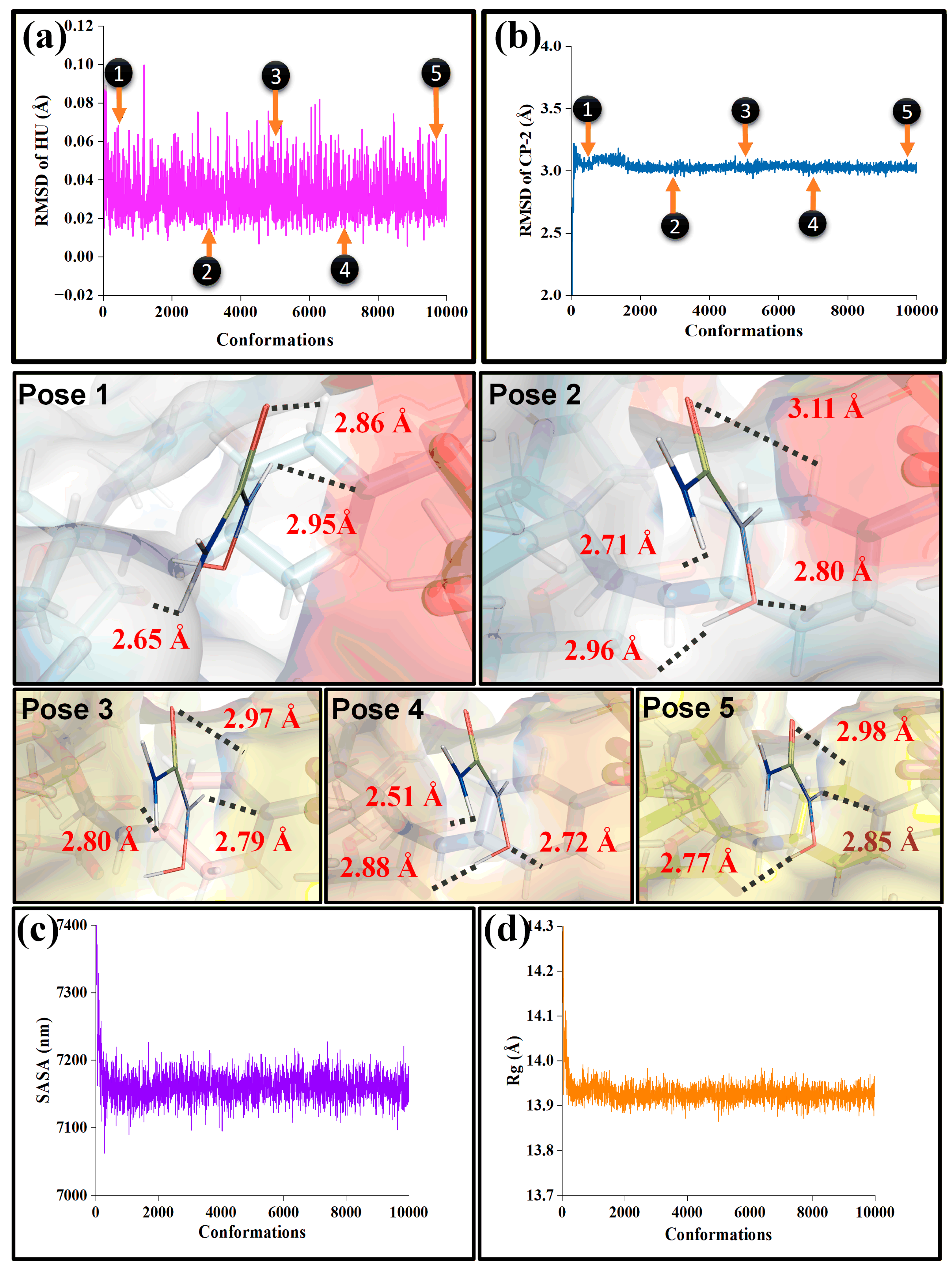

4.2. Multi-pH Molecular Dynamics: Stability, Compactness and Retention

4.3. Conformational Study Resolved MD Snapshots: Geometric Corroboration

4.4. Structure–Property Function Integration and Implications for Targeted Drug Delivery

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CP | Coordination Polymer |

| HU | Hydroxyurea (Drug) |

| MD | Molecular Dynamics |

| CD | Circular dichroism |

| IMP | Inosine monophosphate |

| bpe | 1,2-bis(4-pyridine)ethylene |

| azpy | 4,4′-azopyridine |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| PXRD | Powder X-ray diffraction |

| U | Potential energy |

| K | Kinetic energy |

| SASA | Solvent-accessible surface area |

| Rg | Radius of gyration |

| H | Enthalpy |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| UV–vis | UV–visible |

| FEP | Free Energy Perturbation |

| MM | Molecular Mechanics |

| PBSA | Poisson–Boltzmann Surface Area |

References

- Khan, Y.; Ismail, I.; Ma, H.; Li, Z.; Li, H. Sugar–nucleobase hydrogen bonding in cytidine 5′-monophosphate nucleotide-cadmium coordination complexes. CrystEngComm 2024, 26, 2775–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhong, X.; Wu, X.; Lu, Y.; Khan, M.A.; Li, H. Coordination Patterns of the Diphosphate in IDP Coordination Complexes: Crystal Structure and Chirality. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 19425–19439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.; Dutta, J.; Tulsiyan, K.D.; Sahu, A.K.; Choudhury, S.S.; Biswal, H.S. Noncovalent interactions in proteins and nucleic acids: Beyond hydrogen bonding and π-stacking. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 4261–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Tarrío, F.; Quiñoá, E.; Fernández, G.; Freire, F. Multi-chiral materials comprising metallosupramolecular and covalent helical polymers containing five axial motifs within a helix. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.Y.; Zhang, A.Q.; Zhang, X.Z. Recent advances in targeted tumor chemotherapy based on smart nanomedicines. Small 2018, 14, 1802417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, L.; Harish, P.; Malik, P.S.; Khurana, S. Chemotherapy and targeted therapy in the management of cervical cancer. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2018, 42, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.T.; Tan, Y.J.; Oon, C.E. Molecular targeted therapy: Treating cancer with specificity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 834, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shi, P.; Zhao, G.; Xu, J.; Peng, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X.; Dong, Z.; Chen, F. Targeting cancer stem cell pathways for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, G.; Xu, Z.P.; Li, L. Manipulating extracellular tumour pH: An effective target for cancer therapy. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 22182–22192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Jin, Y.; Fan, Z. The mechanism of Warburg effect-induced chemoresistance in cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 698023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; He, X.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhao, S.; Wei, P.; Li, D. Warburg effect in colorectal cancer: The emerging roles in tumor microenvironment and therapeutic implications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.; Bogdanov, A.; Chubenko, V.; Volkov, N.; Moiseenko, F.; Moiseyenko, V. Tumor acidity: From hallmark of cancer to target of treatment. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 979154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.H.; Luo, G.F.; Zhang, X.Z. Recent advances in subcellular targeted cancer therapy based on functional materials. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1802725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, Y.; Wan, J.; Zhou, L.; Ma, W.; Yang, Y.; Luo, W.; Yu, Z.; Wang, H. Stimuli-responsive nanotherapeutics for precision drug delivery and cancer therapy. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 11, e1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Wang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Qi, W.; Su, R.; He, Z. Constructing redox-responsive metal–organic framework nanocarriers for anticancer drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 16698–16706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Quan, G.; Niu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, C.; Pan, X.; Wu, C. Versatile nanoscale metal–organic frameworks (nMOFs): An emerging 3D nanoplatform for drug delivery and therapeutic applications. Small 2021, 17, 2005064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Vázquez-González, M.; Willner, I. Stimuli-responsive metal–organic framework nanoparticles for controlled drug delivery and medical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 4541–4563. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, T.; Zhou, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Mao, C.; Yang, M. Biomimetic nucleation of Metal–Organic frameworks on silk fibroin nanoparticles for designing Core–Shell-Structured pH-Responsive anticancer drug carriers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 47371–47381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Dong, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z. Metal–organic frameworks (MOF)-assisted sonodynamic therapy in anticancer applications. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 4102–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantwalawalkar, J.; Mhettar, P.; Nangare, S.; Mali, R.; Ghule, A.; Patil, P.; Mohite, S.; More, H.; Jadhav, N. Stimuli-responsive design of metal–organic frameworks for cancer theranostics: Current challenges and future perspective. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 4497–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, F. pH-Responsive Transdermal Release from Poly(vinyl alcohol)-Coated Liposomes and Transethosomes: Investigating the Role of Coating in Delayed Drug Delivery. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 4093–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khafaga, D.S.; El-Morsy, M.T.; Faried, H.; Diab, A.H.; Shehab, S.; Saleh, A.M.; Ali, G.A. Metal–organic frameworks in drug delivery: Engineering versatile platforms for therapeutic applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 30201–30229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishfaq, M.; Lateef, D.; Ashraf, Z.; Sajjad, M.; Owais, M.; Shoukat, W.; Mohsin, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Verpoort, F.; Chughtai, A.H. Zirconium-based MOFs as pH-responsive drug delivery systems: Encapsulation and release profiles of ciprofloxacin. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 26647–26659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-N.; Khan, S.; Song, Y.; Dong, M.; Shen, Y.; Tran, D.K.; Pang, C.; Zhang, F.; Wooley, K.L. A tale of drug-carrier optimization: Controlling stimuli sensitivity via nanoparticle hydrophobicity through drug loading. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 6563–6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, A.; Begdelo, J.M.; Yaghoubi, H.; Motallebinia, S. Multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles for controlled release of anticancer drug, breast cancer cell targeting, MRI/fluorescence imaging, and anticancer drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 49, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, F.; Davaran, S.; Hekmati, M.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Baradaran, B.; Moghaddam, S.V. An improved method in fabrication of smart dual-responsive nanogels for controlled release of doxorubicin and curcumin in HT-29 colon cancer cells. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, H.; Nishio, T.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Sadakane, K.; Kenmotsu, T.; Koga, T.; Yoshikawa, K. Characteristic effect of hydroxyurea on the higher-order structure of DNA and gene expression. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halcrow, P.W.; Geiger, J.D.; Chen, X. Overcoming chemoresistance: Altering pH of cellular compartments by chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 627639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Zhao, K.; Aqil, H.Z.; Nabat, K.Y.; Ma, H.; Li, H. Design of Cu (II) Nucleotide Coordination Complex by Engineered π-π Stacking Interaction: Crystal Structure and Enantiomer Recognition of Amino Acids. Cryst. Growth Des. 2025, 25, 8035–8046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Deng, Z.-L.; Geng, G.; Zeng, X.; Zeng, Y.; Hu, G.; Overvig, A.; Li, J.; Qiu, C.-W.; Alù, A. Planar chiral metasurfaces with maximal and tunable chiroptical response driven by bound states in the continuum. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, R.; Lu, X.; Hao, X.; Qin, W. An Organic Chiroptical Detector Favoring Circularly Polarized Light Detection from Near-Infrared to Ultraviolet and Magnetic-Field-Amplifying Dissymmetry in Detectivity. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2211935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqlain, M.; Muhammad Zohaib, H.; Ahmad Khan, M.; Qamar, S.; Masood, S.; Lauqman, M.; Ilyas, M.; Irfan, M.; Li, H. Evaluating the Drug Delivery Capacity of 3D Coordination Polymer for Anticancer Drugs. Chem.–Asian J. 2025, 20, e202401475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itzhakov, R.; Tworowski, D.; Sadot, N.; Sayas, T.; Fallik, E.; Kleiman, M.; Poverenov, E. Nucleoside-based cross-linkers for hydrogels with Tunable Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 7359–7370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warwicker, J. The physical basis for pH sensitivity in biomolecular structure and function, with application to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 834011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, H.J. Optoelectronic and Electrochemical Devices for Computing and Memory. Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Pegoraro, A.F.; Han, Y.; Tang, W.; Abeyaratne, R.; Bi, D.; Guo, M. Configurational fingerprints of multicellular living systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2109168118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Du, Y.; Yan, L.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, M.; Ma, H.; Li, H. Structural diversity of nucleotide coordination polymers of cytidine mono-, di-, and tri-phosphates and their selective recognition of tryptophan and tyrosine. Dalton Trans. 2025, 54, 9145–9159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Song, W.; Khan, M.A.; Li, H. Conformation locking of the pentose ring in nucleotide monophosphate coordination polymers via π-π stacking and metal-ion coordination. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 61, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charytanowicz, T.; Dziedzic-Kocurek, K.; Kumar, K.; Ohkoshi, S.-i.; Chorazy, S.; Sieklucka, B. Chirality and Spin Crossover in Iron (II)–Octacyanidorhenate (V) Coordination Polymers Induced by the Pyridine-Based Ligand’s Positional Isomer. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23, 4052–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.Y.; Xiong, L.Y.; Dong, X.Y.; Han, Z.; Liu, H.L.; Zang, S.Q. Reversible Local Protonation-Deprotonation: Tuning Stimuli-Responsive Circularly Polarized Luminescence in Chiral Hybrid Zinc Halides for Anti-Counterfeiting and Encryption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202410416. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, F.; Li, S.; Zhang, J. Dual-ligand chiral MOFs exhibiting circularly polarized room temperature phosphorescence for anti-counterfeiting. Sci. China Chem. 2025, 68, 3064–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Li, Z.; Gao, C.-Y.; Cho, C.H. Mechanisms of drug resistance in colon cancer and its therapeutic strategies. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, C.-Y.; Li, J.-Y.; Hao, G.-F.; Yang, G.-F. A drug-likeness toolbox facilitates ADMET study in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.; Tian, L.; Li, Q.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of the physicochemical properties of acaricides based on Lipinski’s rule of five. J. Comput. Biol. 2020, 27, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.L.; Andricopulo, A.D. ADMET modeling approaches in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spackman, P.R.; Turner, M.J.; McKinnon, J.J.; Wolff, S.K.; Grimwood, D.J.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M.A. CrystalExplorer: A program for Hirshfeld surface analysis, visualization and quantitative analysis of molecular crystals. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2021, 54 Pt 3, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Fernández, L.; Santoro, F.; Improta, R. Nucleic acids as a playground for the computational study of the photophysics and photochemistry of multichromophore assemblies. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 2077–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelgawwad, A.M.; Monari, A.; Tunon, I.; Francés-Monerris, A. Spatial and temporal resolution of the oxygen-independent photoinduced DNA interstrand cross-linking by a nitroimidazole derivative. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 3239–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, F.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Pan, H.; Sun, Z.; Sun, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, J. New insights about the photostability of DNA/RNA bases: Triplet nπ* state leads to effective intersystem crossing in pyrimidinones. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 2042–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Fernandez, L.; Arslancan, S.; Ivashchenko, D.; Crespo-Hernandez, C.E.; Corral, I. Tracking the origin of photostability in purine nucleobases: The photophysics of 2-oxopurine. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 13467–13473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, N.-N.; Dong, X.-Y.; Zang, S.-Q.; Mak, T.C. Chemical flexibility of atomically precise metal clusters. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 7262–7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniya, O.S.; Khasanov, A.F.; Varaksin, M.V.; Starnovskaya, E.S.; Krinochkin, A.P.; Savchuk, M.I.; Kopchuk, D.S.; Kovalev, I.S.; Kim, G.A.; Nosova, E.V. Azapyrene-based fluorophores: Synthesis and photophysical properties. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 20955–20971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, D. Structural analysis of biomacromolecules using circular dichroism spectroscopy. In Advanced Spectroscopic Methods to Study Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 77–103. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, D.L.; Bergman, A.E.; Nagy, G. Investigating the structure of α/β carbohydrate linkage isomers as a function of group I metal adduction and degree of polymerization as revealed by cyclic ion mobility separations. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 32, 2573–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-P.; Yin, S.-Y.; Pan, M.; Wu, K.; Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.-X.; Hou, Y.-J. Circular dichroism enhancement by the coordination of different metal ions with a pair of chiral tripodal ligands. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2015, 54, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.J.; Li, Z.; Khan, M.A.; Zhu, Y.; Hussain, W.; Su, H.; Qiu, Q.-M.; Shoukat, R.; Li, H. Studies on the structure and chirality of A-motif in adenosine monophosphate nucleotide metal coordination complexes. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 4175–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.-j.; Su, H.; Zhou, P.; Zhu, Y.-h.; Khan, M.A.; Song, J.-b.; Li, H. Controllable synthesis of two adenosine 5′-monophosphate nucleotide coordination polymers via pH regulation: Crystal structure and chirality. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 4713–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xiao, Y. Chirality in polythiophenes: A review. Chirality 2021, 33, 424–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Arora, A.; Maikhuri, V.K.; Chaudhary, A.; Kumar, R.; Parmar, V.S.; Singh, B.K.; Mathur, D. Advances in chromone-based copper (ii) Schiff base complexes: Synthesis, characterization, and versatile applications in pharmacology and biomimetic catalysis. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 17102–17139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoubi, A.; Massit, A.; Moutaoikel, S.; Rezzouk, A.; Idrissi, B. Rietveld refinement of the crystal structure of hydroxyapatite using X-ray powder diffraction. Am. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergedahl, M.; Narea, P.; Llanos, J.; Pulido, R.; Naveas, N.; Amo-Ochoa, P.; Zamora, F.; Delgado, G.E.; Galleguillos Madrid, F.M.; León, Y. Synthesis, Crystal Structures, Hirshfeld Surface Analysis, Computational Investigations, Thermal Properties, and Electrochemical Analysis of Two New Cu (II) and Co (II) Coordination Polymers with the Ligand 5-Methyl-1-(pyridine-4-yl-methyl)-1H-1, 2, 3-triazole-4-carboxylate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1671. [Google Scholar]

| CP−1 {[Zn4(IMP)(bpe)2]·14H2O}n | CP−2 {[Zn4(IMP)(azpy)2]·14H2O}n | |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C64P4O46Zn4N20H92 | C120H164N48O89P8Zn8 |

| Formula weight | 2262.93 | 4473.70 |

| Temperature/K | 293(2) | 296(2) |

| Crystal system | monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P21 | P21 |

| a/Å | 10.1405(5) | 10.1689(7) |

| b/Å | 30.6112(9) | 29.778(2) |

| c/Å | 15.1155(6) | 15.1974(10) |

| α/° | 90 | 90 |

| β/° | 108.523(5) | 109.444(2) |

| γ/° | 90 | 90 |

| Volume/Å3 | 4449.0(3) | 4339.4(5) |

| Z | 2 | 1 |

| ρcalcg/cm3 | 1.689 | 1.712 |

| μ/mm−1 | 1.248 | 1.278 |

| F(000) | 2328.0 | 2292.0 |

| Crystal size/mm3 | 0.23 × 0.18 × 0.12 | 0.34 × 0.18 × 0.17 |

| Radiation | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) |

| 2Θ range for data collection/° | 6.804 to 59.618 | 2.736 to 50.7 |

| Index ranges | −13 ≤ h ≤ 14, −42 ≤ k ≤ 42, −20 ≤ l ≤ 20 | −12 ≤ h ≤ 12, −35 ≤ k ≤ 35, −18 ≤ l ≤ 18 |

| Reflections collected | 51,930 | 43,468 |

| Independent reflections | 20603 [Rint = 0.0808, Rsigma = 0.0889] | 15878 [Rint = 0.0272, Rsigma = 0.0439] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 20603/28/1243 | 15878/9/1237 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 0.952 | 1.014 |

| Final R indexes [I ≥ 2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0552, wR2 = 0.1439 | R1 = 0.0286, wR2 = 0.0729 |

| Final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.0672, wR2 = 0.1510 | R1 = 0.0318, wR2 = 0.0740 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole / e Å−3 | 1.32/−1.40 | 0.93/−0.55 |

| Flack parameter | 0.024(9) | 0.014(8) |

| CCDC no. | 2504381 | 2504362 |

| MD Simulations | RMSD Polymer | RMSD Drug | Rg | U (kcalmol−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP−1 Å | CP−2 | CP−1 | CP−2 | CP−1 | CP−2 | CP−1 | CP−2 | ||

| pH | 5.0 | 3.46 ± 0.26 | 3.56 ± 0.15 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 11.73 ± 0.80 | 13.95 ± 0.06 | −5992.17 ± 10.14 | −4375.33 ± 215.19 |

| 7.4 | 3.02 ± 0.11 | 3.74 ± 0.06 | 0.028 ± 0.01 | 0.038 ± 0.01 | 11.67 ± 0.03 Å | 13.93 ± 0.03 | −6062.18 ± 53.2 | −4385.66 ± 95.50 | |

| 9.0 | 3.10 ± 0.29 | 3.38 ± 0.27 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 11.89 ± 0.14 Å | 13.87 ± 0.07 | −6029.17 ± 38.30 | −4499.30 ± 214.10 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aqil, H.Z.; Zhu, Y.; Khan, M.H.; Khan, Y.; Sandhu, B.; Irfan, M.; Li, H. Zn–IMP 3D Coordination Polymers for Drug Delivery: Crystal Structure and Computational Studies. Polymers 2026, 18, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010119

Aqil HZ, Zhu Y, Khan MH, Khan Y, Sandhu B, Irfan M, Li H. Zn–IMP 3D Coordination Polymers for Drug Delivery: Crystal Structure and Computational Studies. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010119

Chicago/Turabian StyleAqil, Hafiz Zeshan, Yanhong Zhu, Masooma Hyder Khan, Yaqoot Khan, Beenish Sandhu, Muhammad Irfan, and Hui Li. 2026. "Zn–IMP 3D Coordination Polymers for Drug Delivery: Crystal Structure and Computational Studies" Polymers 18, no. 1: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010119

APA StyleAqil, H. Z., Zhu, Y., Khan, M. H., Khan, Y., Sandhu, B., Irfan, M., & Li, H. (2026). Zn–IMP 3D Coordination Polymers for Drug Delivery: Crystal Structure and Computational Studies. Polymers, 18(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010119