Effect of Scratches on Mechanical Properties and Impermeability of PVC-P Geomembranes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Test Methods

2.2.1. Axial Tensile Test

2.2.2. Vertical Permeability Test

3. Results

3.1. Results of Axial Tensile Test

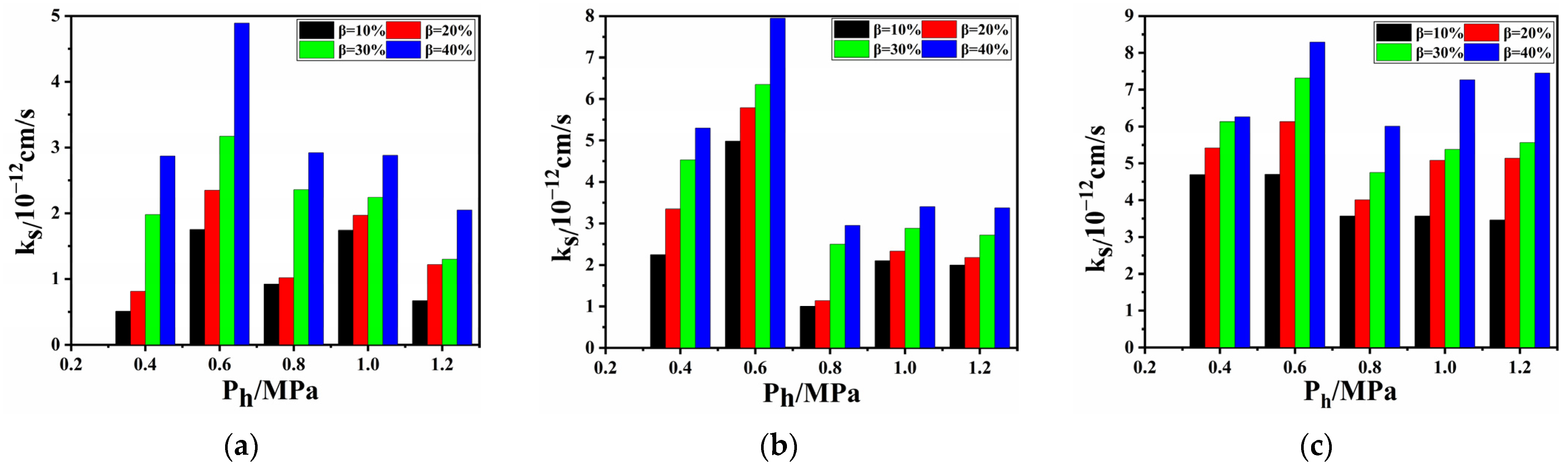

3.2. Results of Vertical Permeability Test

3.3. Preliminary Analysis of Mechanical Properties

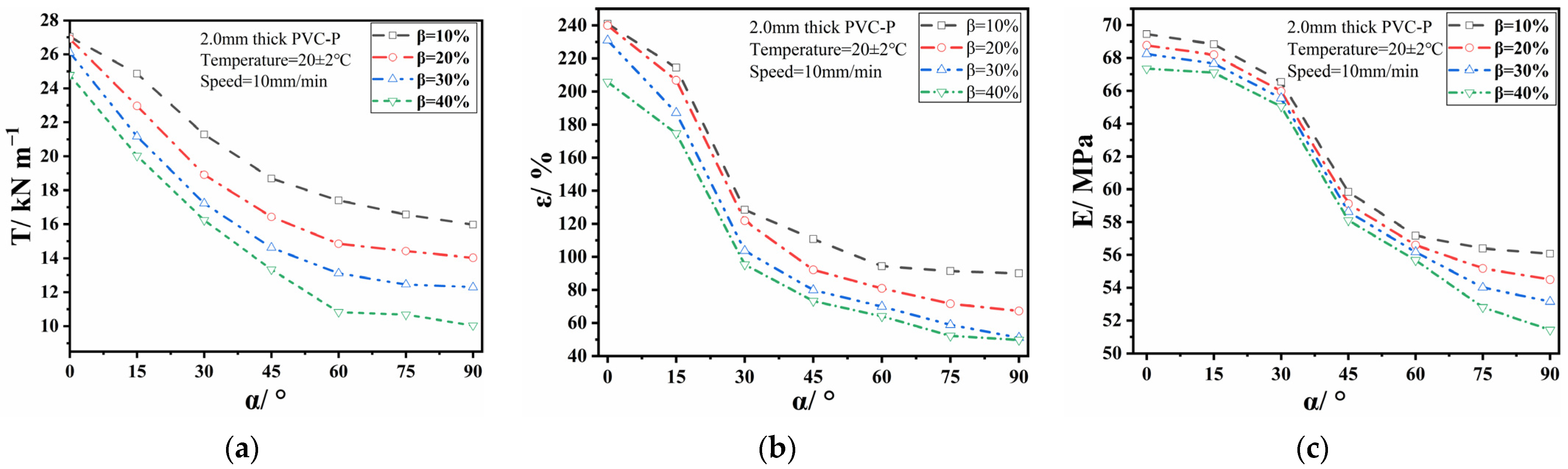

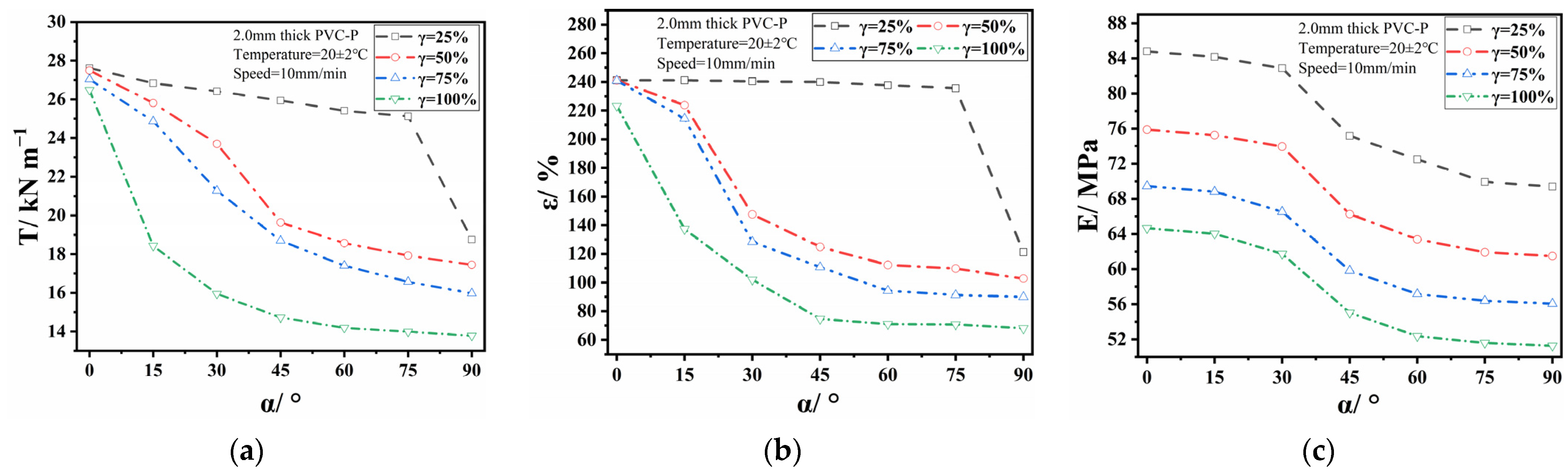

3.3.1. Influence of Single Factor

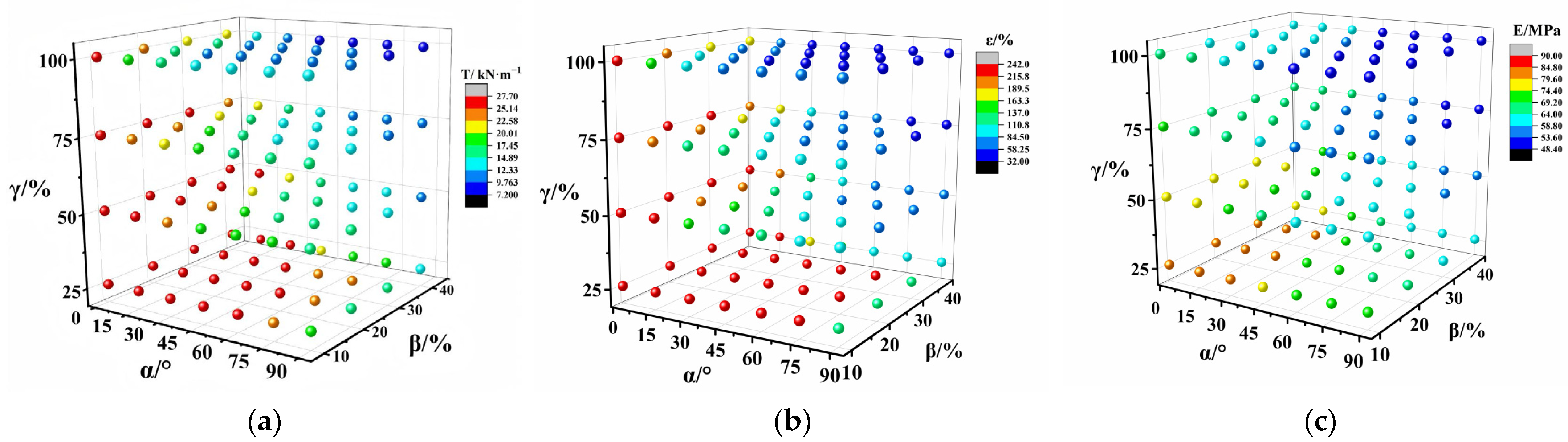

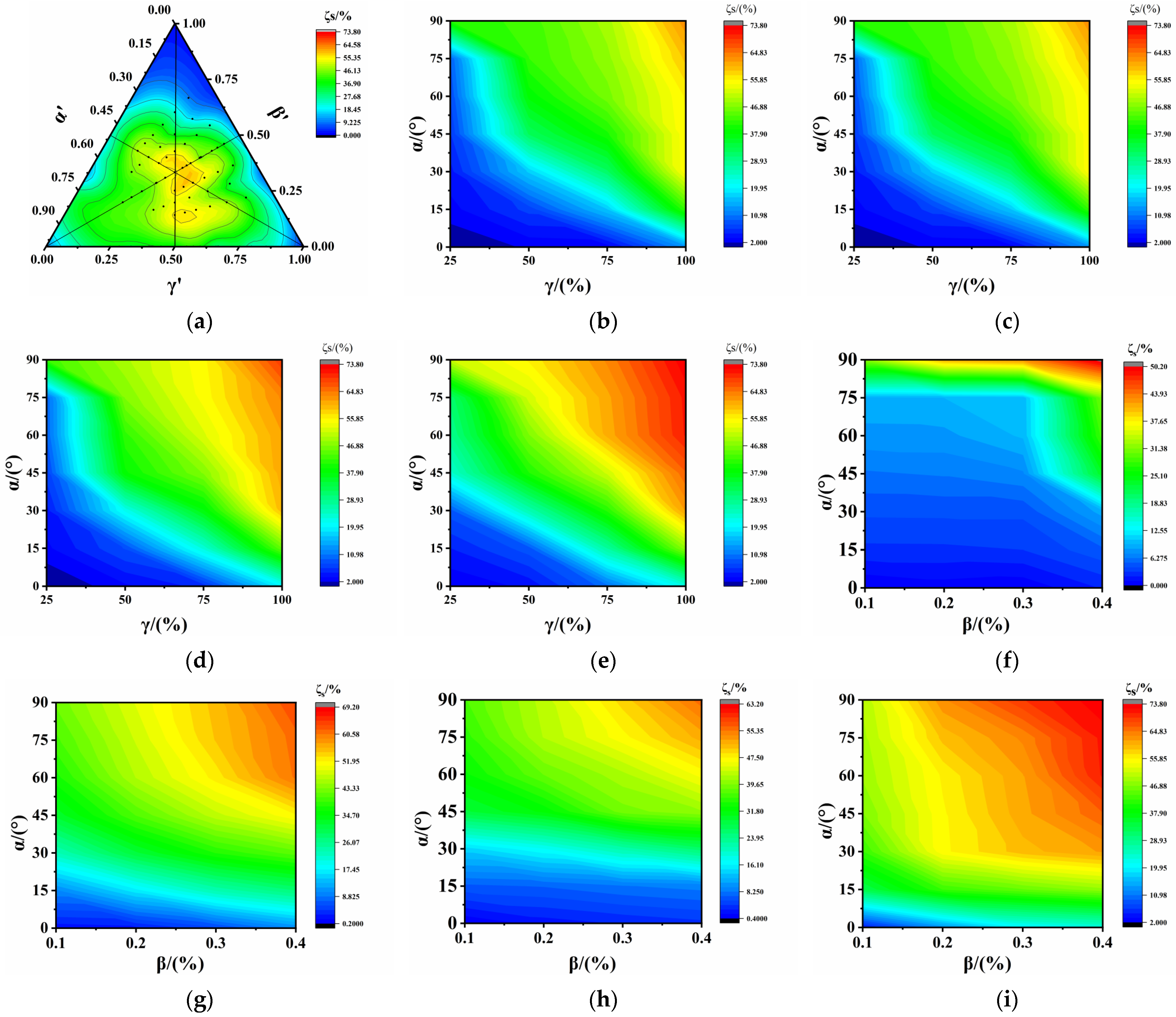

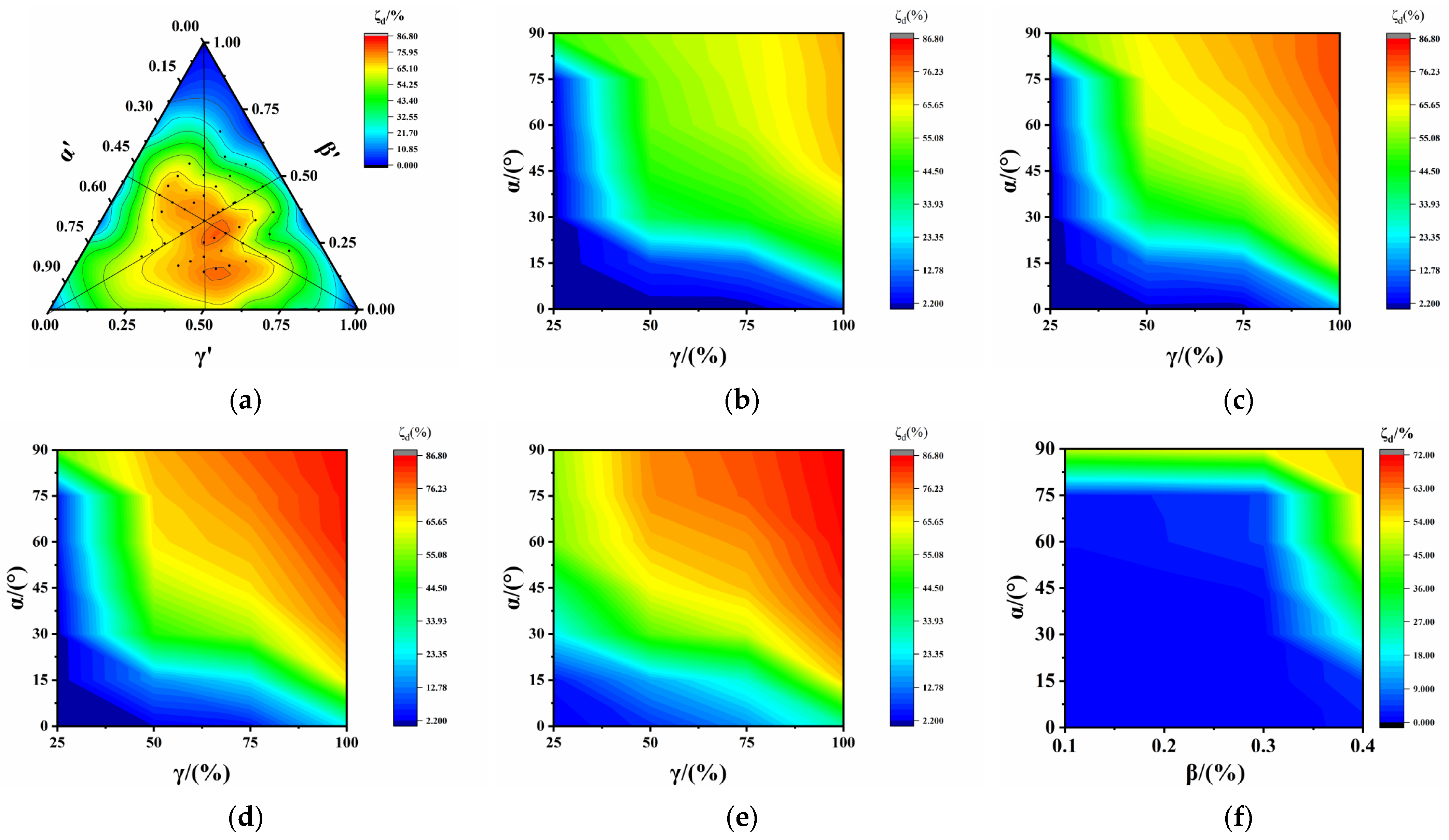

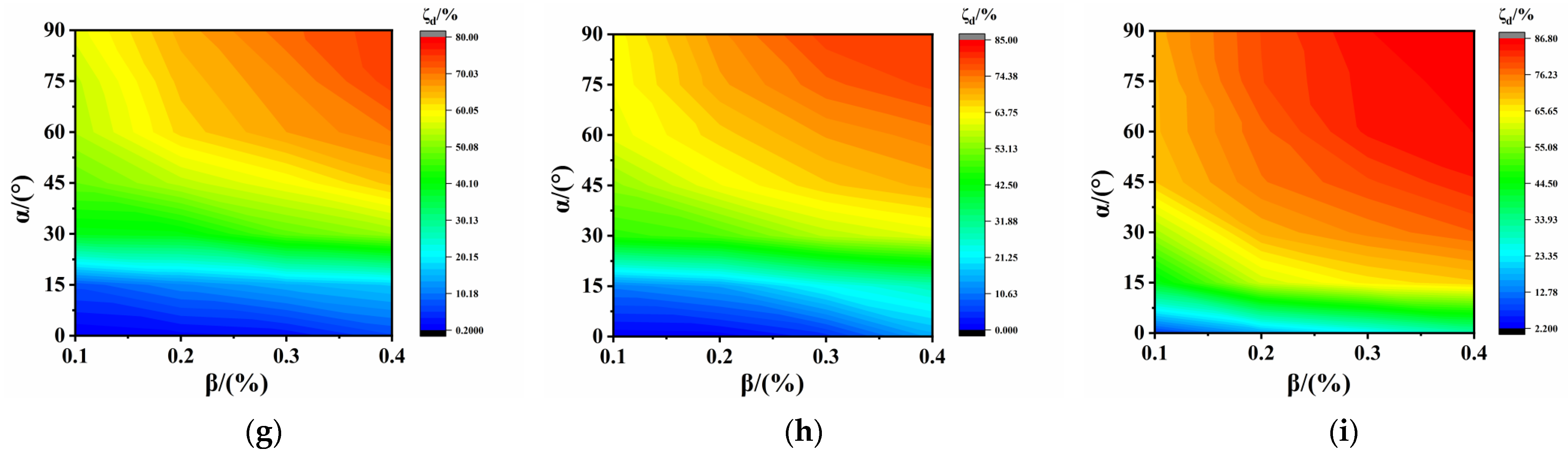

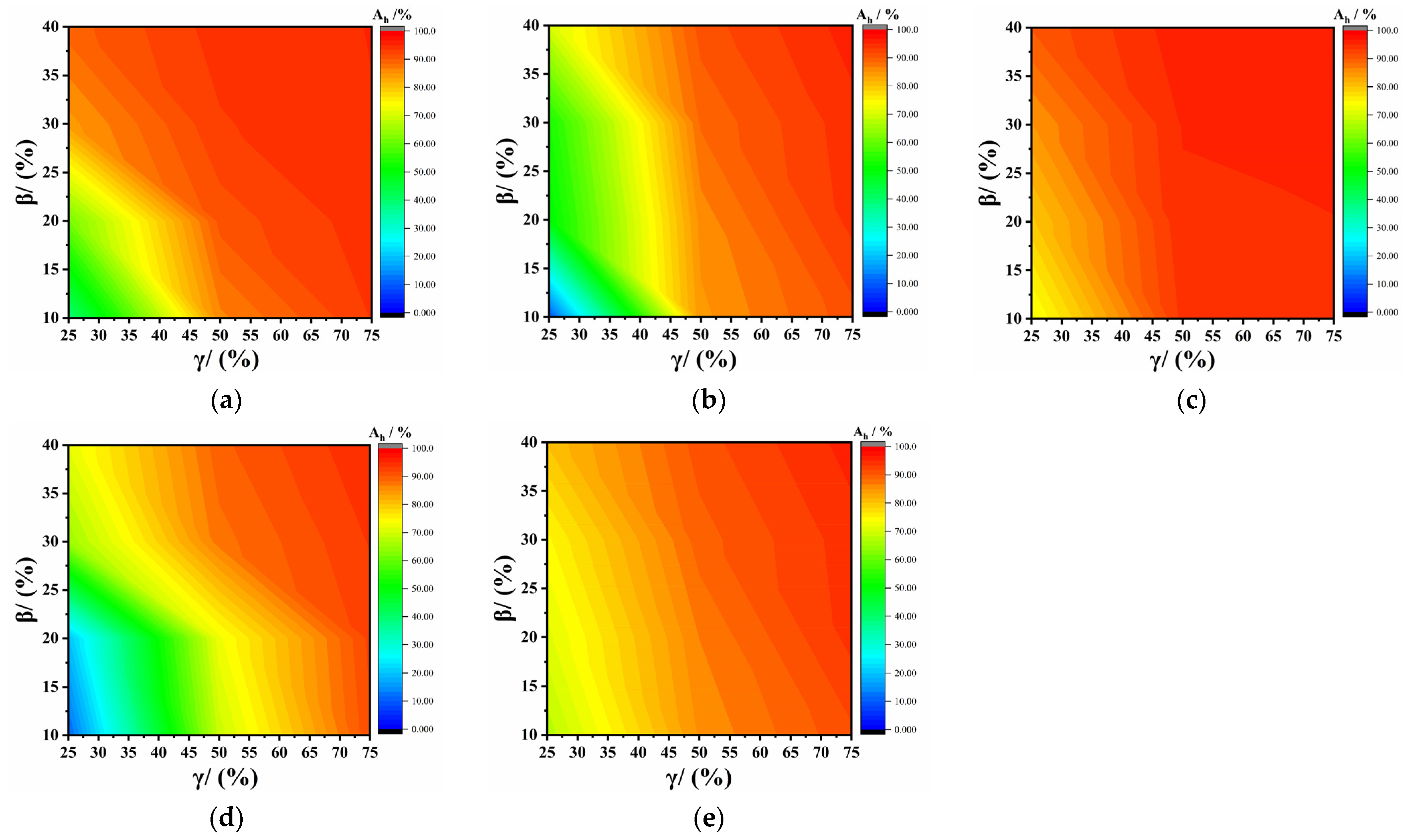

3.3.2. Comprehensive Influence

3.4. Preliminary Analysis of Permeability

4. Discussion

4.1. Attenuation Rate

4.2. Analysis of ARBS

4.3. Analysis of ARBE

4.4. Analysis of ARYM

4.5. Attenuation Rate of Impermeability

4.6. Threshold Value

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The break strength, break elongation, and Young’s modulus of PVC-P GMBs with scratches all exhibited varying degrees of attenuation. The findings indicated that the significance of these influences primarily relied on the SDR and SA. Therefore, it is essential to monitor the SDR and SA during transportation, loading and unloading, and construction. Furthermore, it is recommended to increase the thickness of PVC-P GMBs to reduce the SDR in harsh environments.

- (2)

- The interaction between the SDR and SA was found to be statistically significant, with a greater impact on the break strength and elongation compared with Young’s modulus. Consequently, engineering quality inspections should examine whether the break elongation and strength of PVC-P GMBs with scratches fulfill the requirements in the specifications.

- (3)

- For PVC-P GMBs with no penetrating scratches in the thickness direction and no tensile deformation in the scratched area, the SLR and SDR had a negligible influence on their impermeability.

- (4)

- The threshold for the effectiveness of PVC-P GMBs with scratches was established, and the scratches not resulting in failure of the PVC-P GMBs were summarized, which provided theoretical references for assessing whether the scratches posed a safety risk to the projects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Girard, H.; Fischer, S.; Alonso, E. Problems of friction posed by the use of geomembranes on dam slopes—Examples and measurements. Geotext. Geomembr. 1990, 9, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciani, A.; Todaro, C.; Martinelli, D.; Peila, D. Long-term durability assessment of PVC-P waterproofing geomembranes through laboratory tests. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 103, 103499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, E.J.; Stark, T.D. Ten-year PVC geomembrane durability. Geosynth. Int. 2009, 16, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.K.; Ewais, A.M.R. Ageing of exposed geomembranes at locations with different climatological conditions. Can. Geotech. J. 2014, 52, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOLD. Geomembrane Sealing Systems for Dams-Design Principles and Review of Experience; Bulletin 135; International Commission on Large Dams: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, M.; Touze-Foltz, N.; Pérez Sánchez, M.; Redón-Santafé, M.; Sánchez Romero, F.J.; Torregrosa Soler, J.B.; Zapata Raboso, F.A. Durability of reinforced PVC-P geomembranes installed in reservoirs in eastern Spain. Geosynth. Int. 2018, 25, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzuffi, D.; Gioffrè, D. Lifetime assessment of exposed PVC-P geomembranes installed on Italian dams. Geotext. Geomembr. 2020, 48, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.J.; Ross, J.D.; Sura, J.M.; Thiel, R.S. Geomembrane damage due to static and cyclic shearing over compacted gravelly sand. Geosynth. Int. 2011, 18, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, E.M.; Tonks, D.M.; Shevelan, J.; Belton, A.R.; Blackmore, R.E. Investigations of geomembrane integrity within a 25-year old landfill capping. Geotext. Geomembr. 2016, 44, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudina, S.; Brachman, R.W.I. Geomembrane strains from wrinkle deformations. Geotext. Geomembr. 2011, 29, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroud, J.P.; Badu-Tweneboah, K.; Soderman, K.L. Theoretical analysis of geomembrane puncture. Geosynth. Int. 2015, 2, 1019–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narejo, D.; Koerner, R.M.; Wilson-Fahmy, R.F. Puncture protection of geomembranes part ii: Experimental. Geosynth. Int. 1996, 3, 629–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.M.; Zhang, W.M.; Peng, G.X. Effect of damage on mechanical behavior of HDPE geomembrane. J. Hohai Univ. 2004, 32, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, T.D.; Boerman, T.R.; Connor, C.J. Puncture resistance of PVC geomembranes using the truncated cone test. Geosynth. Int. 2008, 15, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosko, V.; Touze-Foltz, N. Geomembrane liner failure: Modelling of its influence on contaminant transfer. In Proceedings of the Second European Geosynthetics Conference, Bologna, Italy, 15–18 October 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, R.K.; Fan, J.Y. Effect of geomembrane hole geometry on leakage overlain by saturated tailings. Geotext. Geomembr. 2021, 49, 1506–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroud, J.P.; Morel, N. Analysis of geomembrane wrinkles. Geotext. Geomembr. 1992, 11, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Take, W.A.; Chappel, M.J.; Brachman, R.W.I.; Rowe, R.K. Quantifying geomembrane wrinkles using aerial photography and digital image processing. Geosynth. Int. 2007, 14, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhu, B.; Chen, Y.M. Mechanism and analytic model of wrinkled geomembranes around circular structures subjected to differential settlement. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2008, 30, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Gudina, S.; Brachman, R.W.I. Physical response of geomembrane wrinkles overlying compacted clay. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2006, 132, 1346–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Liu, Y.F.; Gu, K.; Mao, W.L. Experimental study on geomembrane bending (folding) in anti-seepage structure of membrane-faced rockfill dam. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2019, 41, 1555–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, Y.M.; Pan, J. Mullen strength experiment on damaged geomembrane. Adv. Sci. Technol. Water Resour. 2005, 25, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Li, W.L.; Liu, Z.L.; Zhang, B.F.; Zhang, B.Y. Study of factors that influence geomembrane air expansion deformation under ring-restrained conditions. Geotext. Geomembr. 2017, 45, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, W.J.; Wang, H.; Li, D.J.; Wen, L.S. Large-strain tensile behavior of geomembranes with defects using 3d digital image correlation. Geosynth. Int. 2018, 25, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, W.J.; Zheng, C.H.; Wang, H.; Geng, L.Y.; Wang, M.M. Puncture behavior of HDPE geomembranes with defects: Laboratory investigation. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2022, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Ma, Z.Y.; Wu, Y.Y. Mechanical properties of different geomembranes in membrane faced rockfill dam. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 45, 940–952. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D5199-12; Standard Test Method for Measuring the Nominal Thickness of Geosynthetics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- ASTM D5261-10; Standard Test Method for Measuring Mass per Unit Area of Geotextiles. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM D6693/D6693M-04; Standard Test Method for Determining Tensile Properties of Nonreinforced Polyethylene and Nonreinforced Flexible Polypropylene Geomembranes. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM D4885-01; Standards Test Method for Determining Performance Strength of Geomembranes by the Wide Strip Tensile Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2011.

- ASTM D5084-16a; Standard Test Method for Measurement of Hydraulic Conductivity of Saturated Porous Materials Using a Flexible Wall Permeameter. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Ewais, A.M.R.; Rowe, R.K.; Rimal, S.; Sangam, H.P. 17-year elevated temperature study of HDPE geomembrane longevity in air, water and leachate. Geosynth. Int. 2018, 25, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsuan, Y.G.; Koerner, R.M. Antioxidant depletion lifetime in high density polyethylene geomembranes. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1998, 124, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.K.; Rimal, S.; Sangam, H. Ageing of HDPE geomembranes exposed to air, water and leachate at different temperatures. Geotext. Geomembr. 2009, 27, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerner, R.M.; Hsuan, Y.G.; Koerner, G.R. Lifetime predictions of exposed geotextiles and geomembranes. Geosynth. Int. 2017, 24, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, M.; Castillo, F.; Touze-Foltz, N.; Amat, B.; Aguiar, E. Behaviour of an EPDM geomembrane 18 years after its installation in a water reservoir. Int. J. Geomate 2015, 9, 1348–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Method | Value(T/L) | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness | ASTM D5199-12 [27] | 2.0 ± 0.2 | mm |

| Mass per unit area | ASTM D5261-10 [28] | 17.7 | kg/m2 |

| Break strength Break elongation Yield strength Yield elongation | ASTM D6693/D6693M-04 [29] | 9.65/10.10 | MPa |

| 310.10/280.00 | % | ||

| 2.57/3.39 | MPa | ||

| 49.85/49.10 | % |

| Ph (MPa) | γ = 25% | γ = 50% | γ = 75% | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β = 10% | β = 20% | β = 30% | β = 40% | β = 10% | β = 20% | β = 30% | β = 40% | β = 10% | β = 20% | β = 30% | β = 40% | |

| 0.4 | 0.51 | 0.81 | 1.98 | 2.87 | 2.25 | 3.35 | 4.53 | 5.30 | 4.69 | 5.42 | 6.13 | 6.26 |

| 0.6 | 1.75 | 2.35 | 3.17 | 4.89 | 4.98 | 5.79 | 6.35 | 7.95 | 4.70 | 6.13 | 7.31 | 8.29 |

| 0.8 | 0.92 | 1.02 | 2.36 | 2.92 | 1.00 | 1.14 | 2.50 | 2.95 | 3.54 | 4.01 | 4.75 | 6.01 |

| 1.0 | 1.74 | 1.97 | 2.24 | 2.88 | 2.10 | 2.33 | 2.88 | 3.40 | 3.57 | 5.08 | 5.38 | 7.27 |

| 1.2 | 0.67 | 1.22 | 1.30 | 2.05 | 2.00 | 2.18 | 2.72 | 3.37 | 3.46 | 5.14 | 5.56 | 7.45 |

| Source | Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | 6 | 2.35 | 0.39 | 14.07 | 1.07 × 10−11 |

| β | 3 | 0.36 | 0.12 | 2.68 | 0.051 |

| γ | 3 | 2.07 | 0.69 | 23.38 | 9.79 × 10−12 |

| Source | Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | 6 | 4.53 | 0.75 | 13.86 | 1.49 × 10−11 |

| β | 3 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 1.83 | 1.45 × 10−01 |

| γ | 3 | 3.94 | 1.31 | 22.52 | 2.12 × 10−11 |

| Source | Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | 6 | 0.54 | 0.09 | 14.71 | 3.91 × 10−12 |

| β | 3 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 1.25 | 2.95 × 10−01 |

| γ | 3 | 0.57 | 0.19 | 34.14 | 1.34 × 10−15 |

| α (°) | β (%) | γ (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 15 | (20, 40) | (25, 75) |

| 30 | (10, 20) | (25, 75) |

| 30 | (30, 40) | (25, 50) |

| 45 | (10, 40) | (25, 50) |

| 60 | (10, 30) | 25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Jiao, K.; Ma, S.; Wu, Y. Effect of Scratches on Mechanical Properties and Impermeability of PVC-P Geomembranes. Polymers 2025, 17, 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17030277

Zhang X, Jiao K, Ma S, Wu Y. Effect of Scratches on Mechanical Properties and Impermeability of PVC-P Geomembranes. Polymers. 2025; 17(3):277. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17030277

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xianlei, Kefan Jiao, Shaoshuai Ma, and Yunyun Wu. 2025. "Effect of Scratches on Mechanical Properties and Impermeability of PVC-P Geomembranes" Polymers 17, no. 3: 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17030277

APA StyleZhang, X., Jiao, K., Ma, S., & Wu, Y. (2025). Effect of Scratches on Mechanical Properties and Impermeability of PVC-P Geomembranes. Polymers, 17(3), 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17030277