Preparation and Performance Characterization of Thixotropic Gelling Materials with High Temperature Stability and Wellbore Sealing Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Experimental Materials and Instruments

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Evaluation of Gelling Time and Strength

2.2.2. Rheological Strength Testing

2.2.3. Determination of High-Temperature Stability

2.2.4. FTIR Characterization

2.2.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.2.6. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

2.2.7. Plugging Performance Evaluation

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Preparation of Thixotropic Polymer Gel System

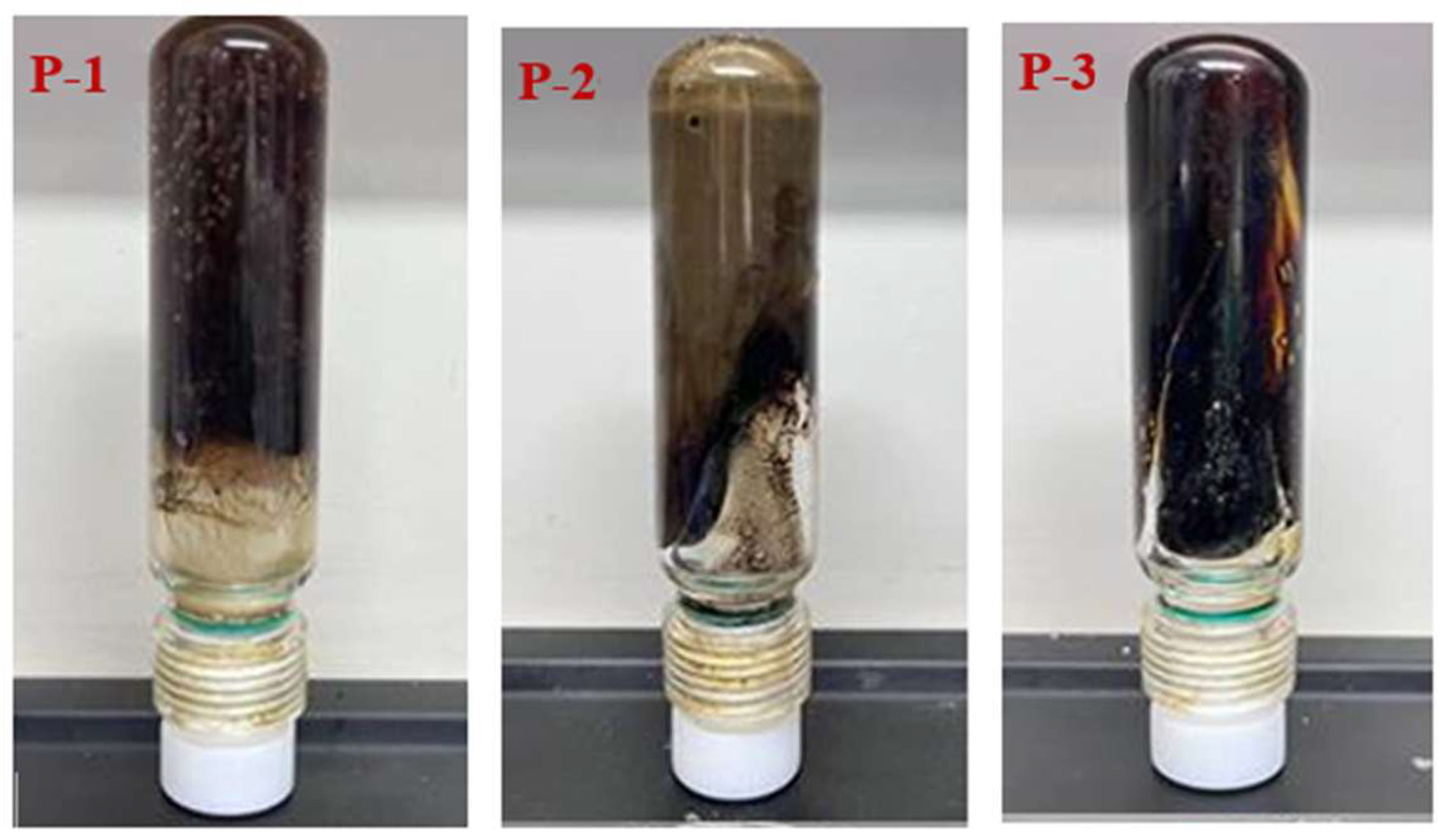

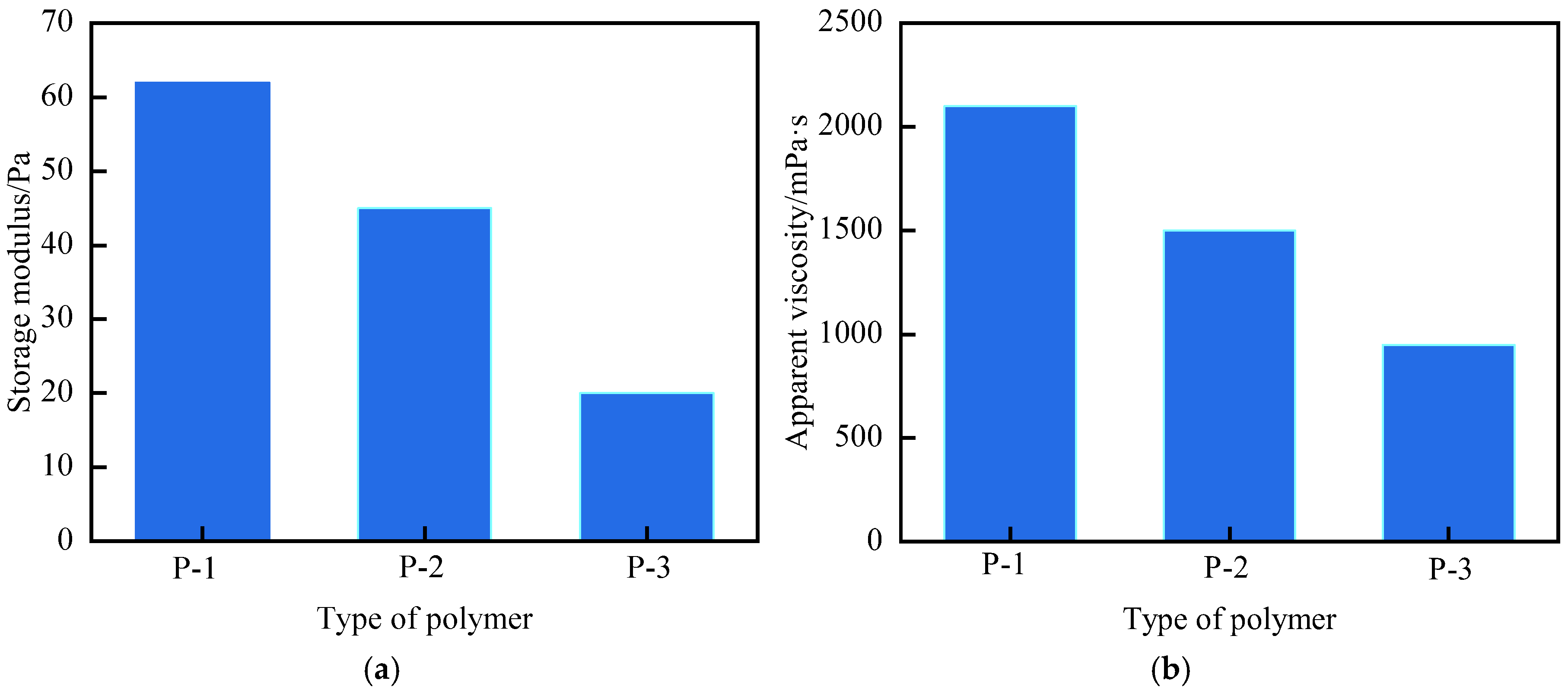

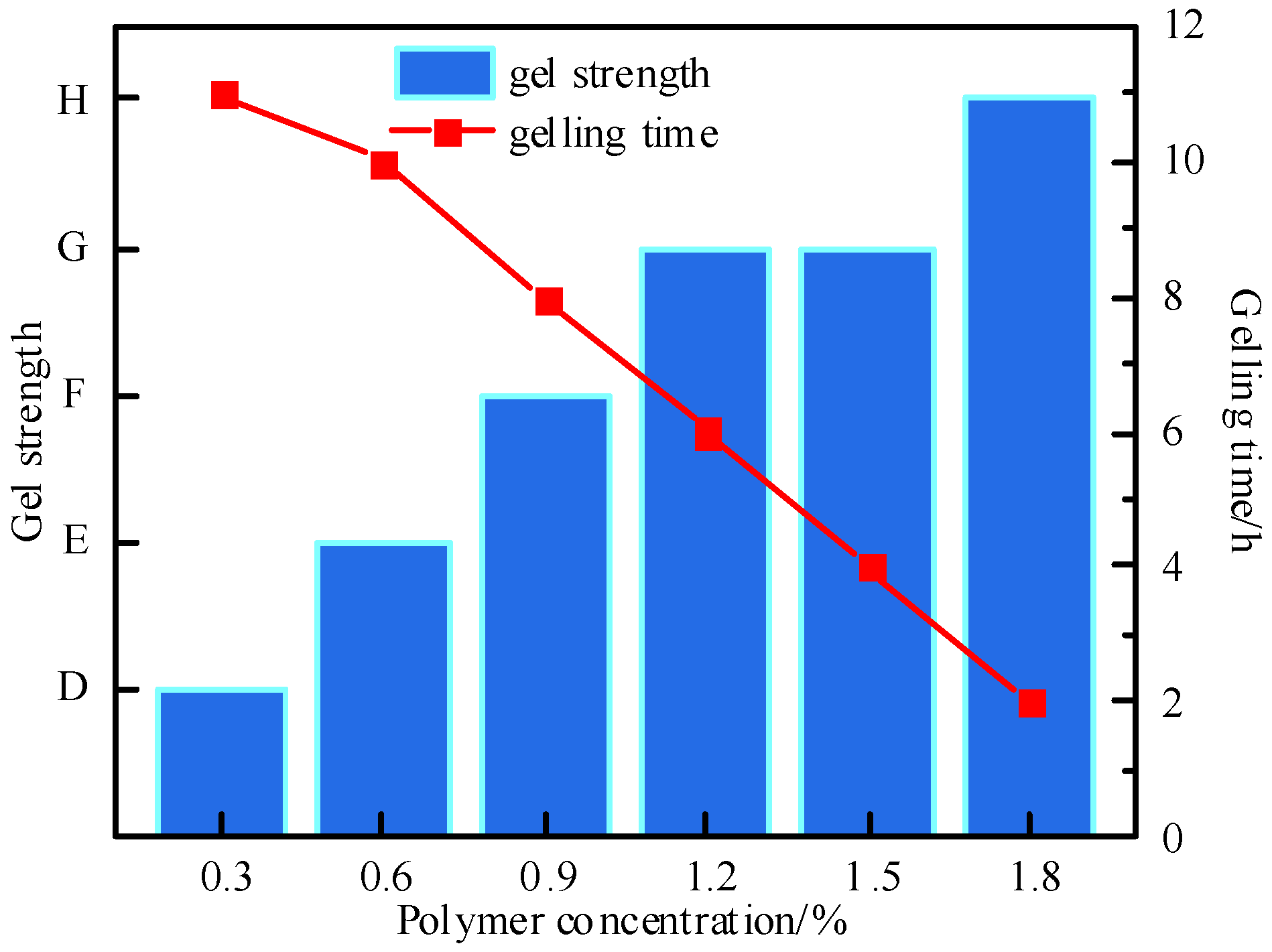

3.1.1. Optimization of Polymer Type and Concentration

3.1.2. Optimization of Crosslinker Type and Concentration

Optimization of Aldehyde Crosslinker

Optimization of Phenolic Crosslinker

3.1.3. Optimization of Flow Pattern Regulators Type and Concentration

3.1.4. Optimization of Resin Hardener Type and Concentration

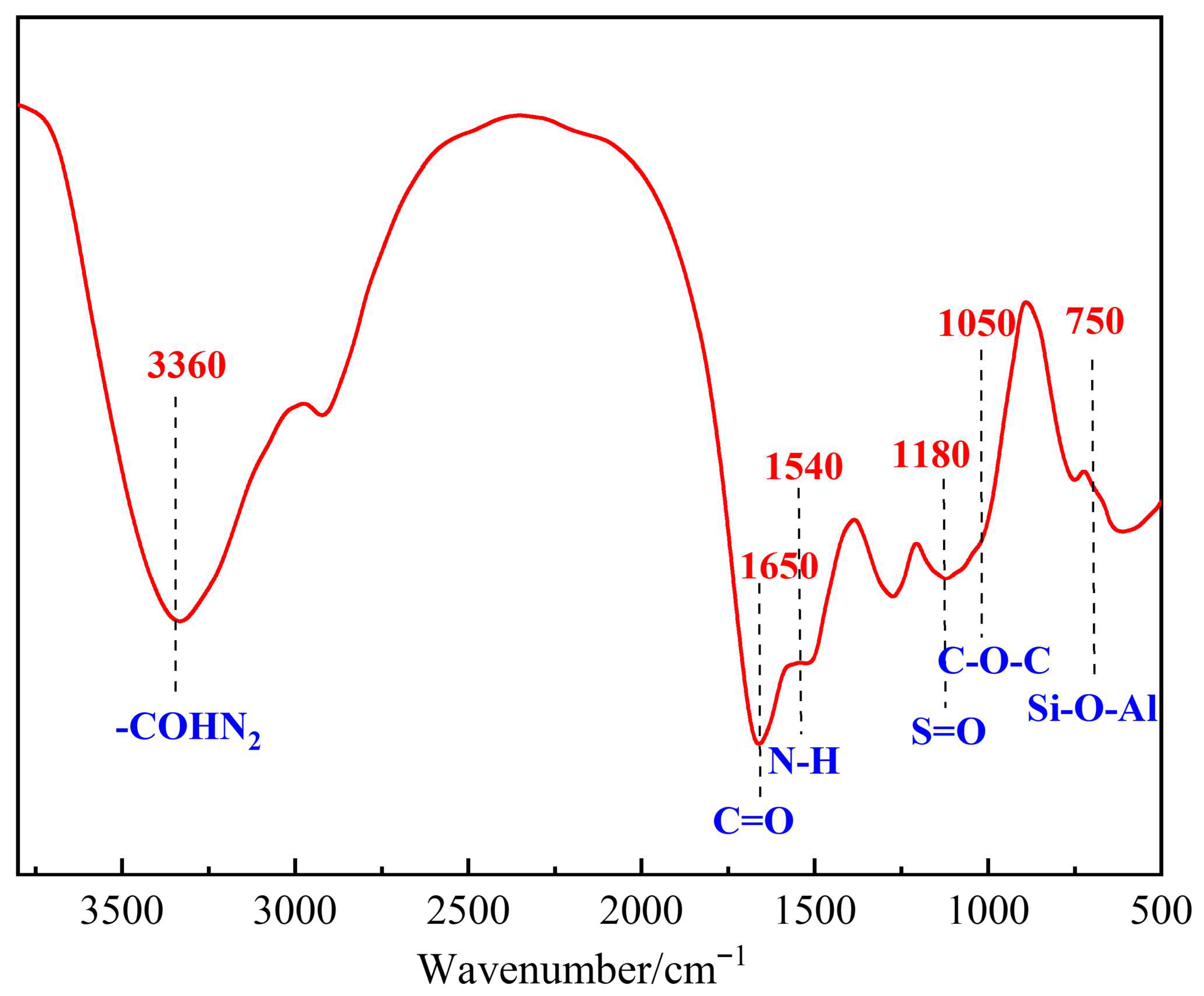

3.2. Molecular Structure Characterization of the Polymer Gel System

3.3. Evaluation of Performance of Thixotropic Polymer Gel System

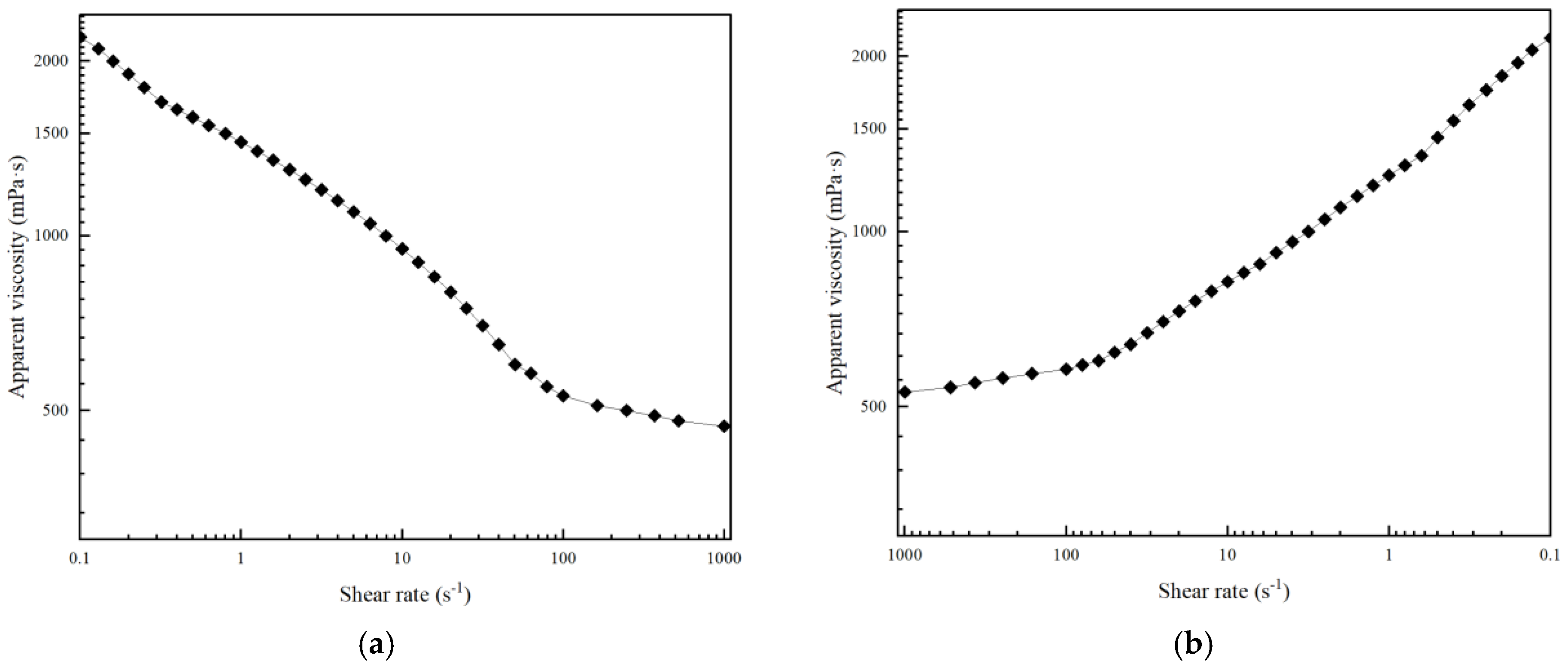

3.3.1. Shear Resistance of Polymer Gel System

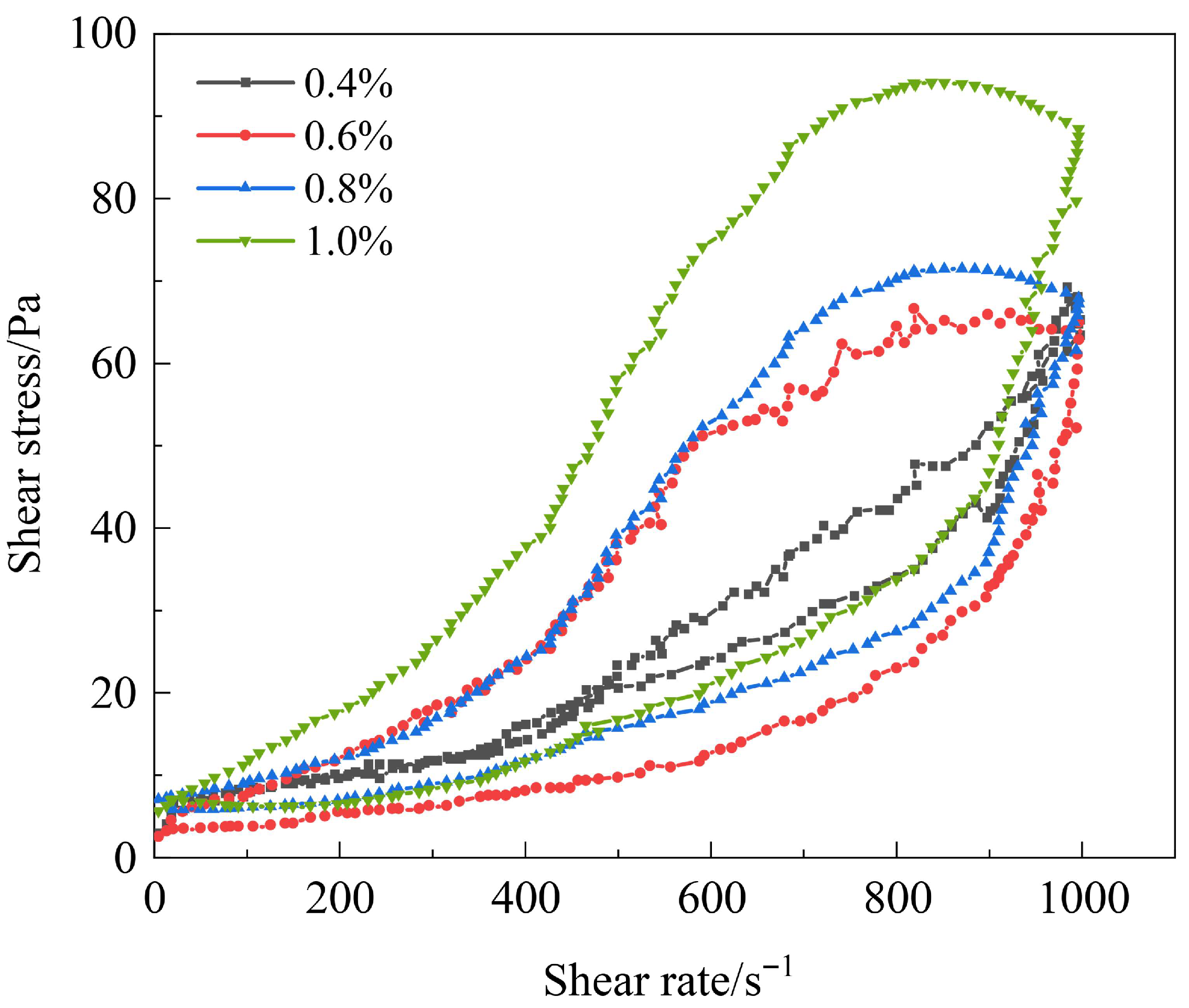

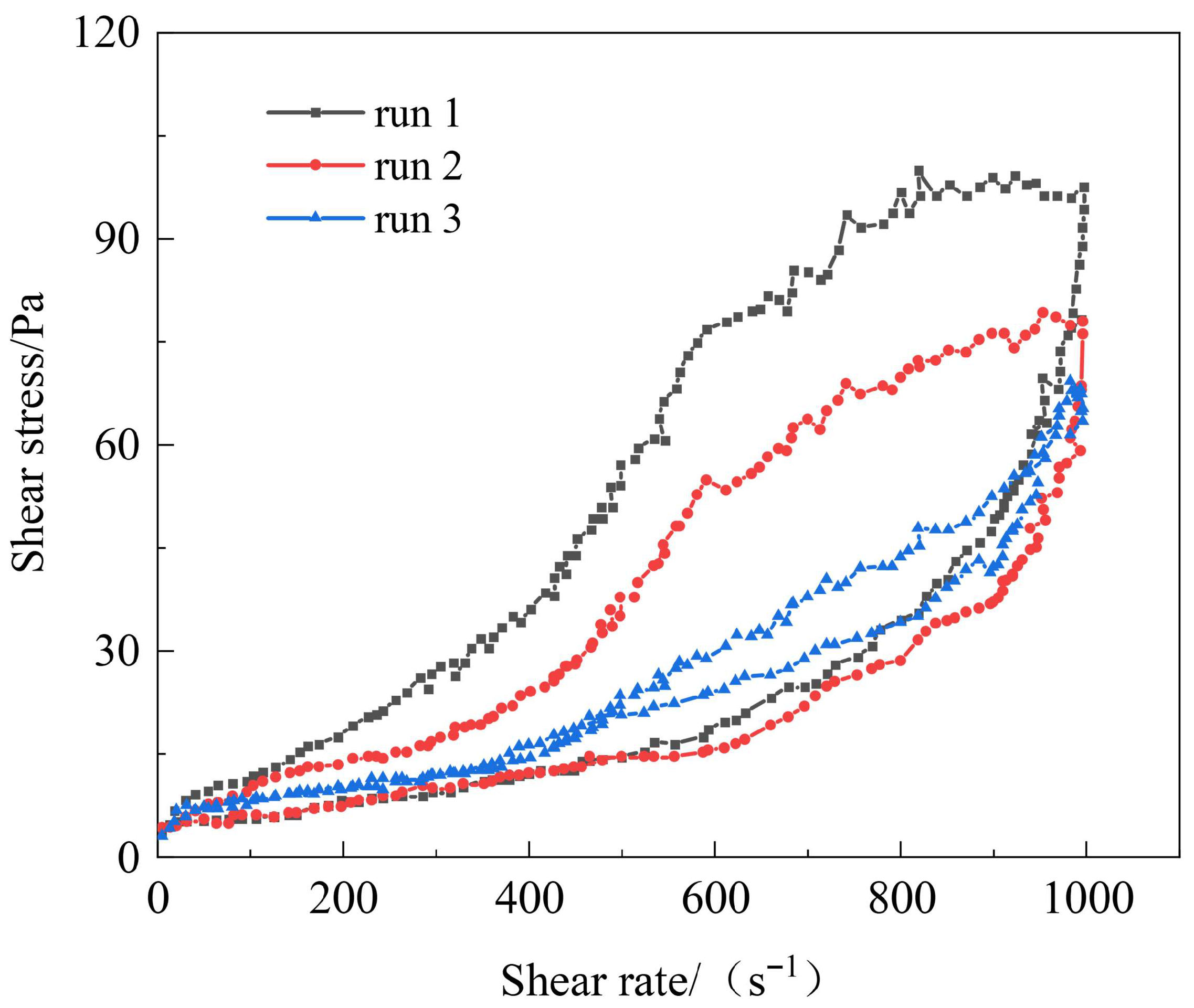

3.3.2. Thixotropic Behavior of Polymer Gel System

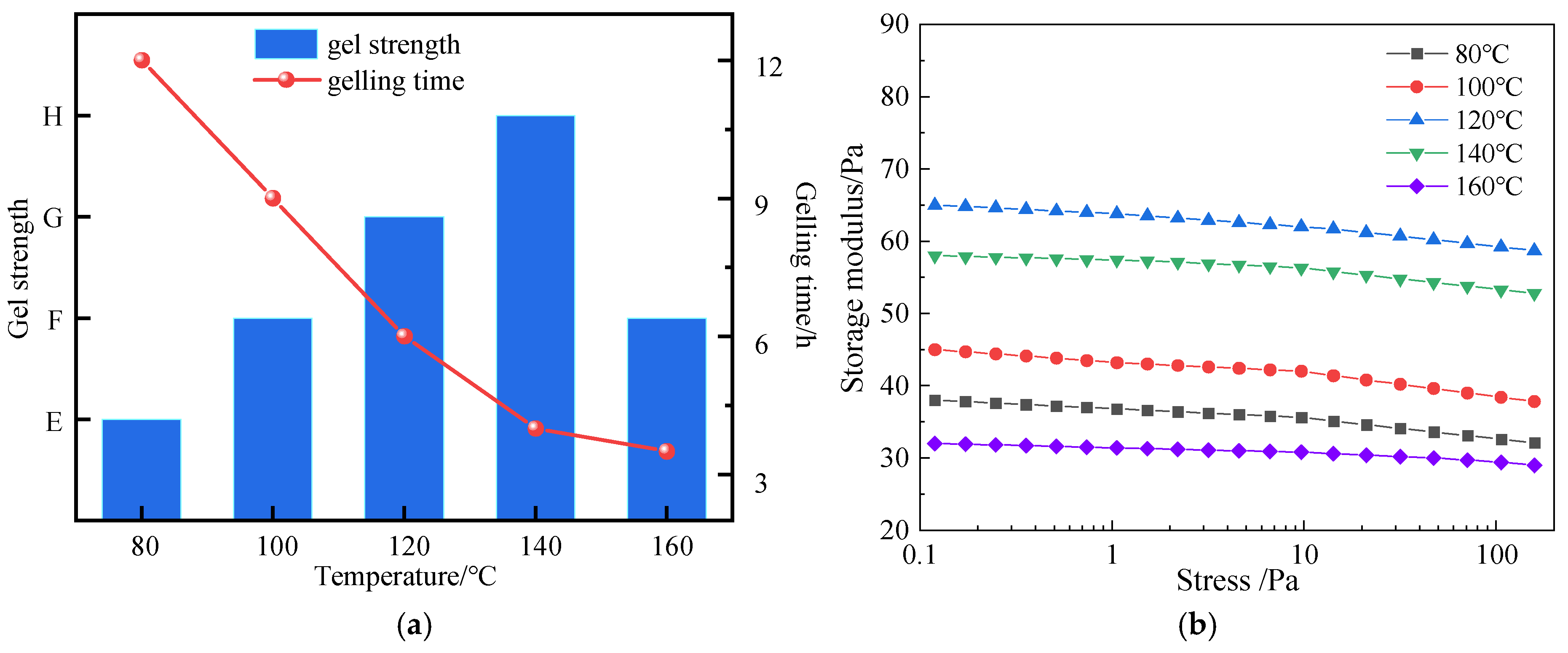

3.3.3. High-Temperature Gelation Performance

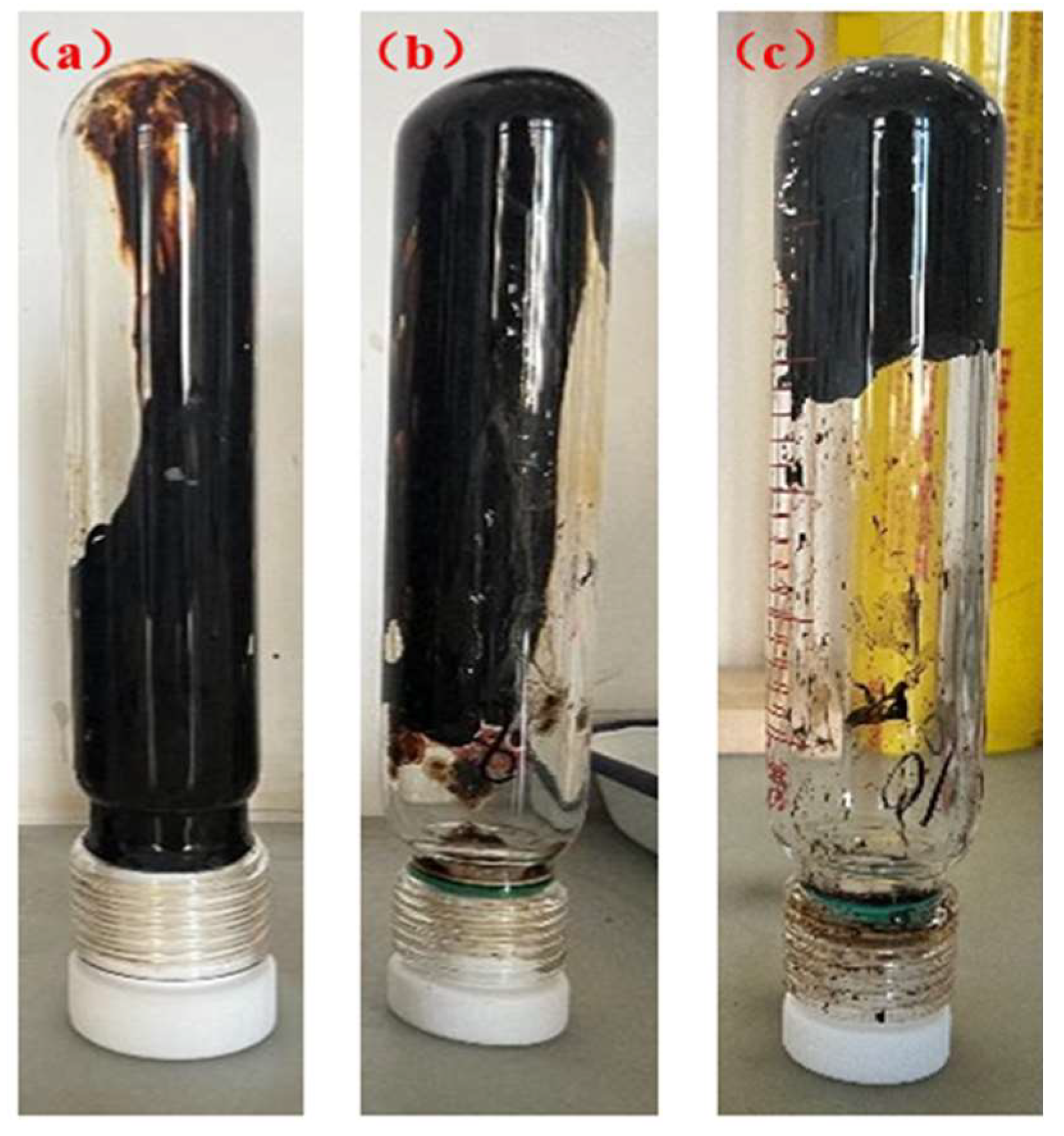

3.3.4. High-Temperature Stability of Polymer Gel System

3.3.5. Plugging Performance of Polymer Gel System

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bao, D.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Sang, Y.; Miao, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, B.; Liang, T.; Zhang, P. Preparation and performance of high temperature resistant and high strength self-healing lost circulation material in the drilling industry. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 3655–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Xu, C.; Kang, Y.; Shang, X.; You, L.; Jing, H. Mesoscopic structure characterization of plugging zone for lost circulation control in fractured reservoirs based on photoelastic experiment. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 79, 103339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Huang, Y. Numerical investigation on the fracture-bridging behaviors of irregular non-spherical stiff particulate lost circulation materials in a fractured leakage well section. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 223, 211577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sun, J.; Long, Y.; Wang, R.; Qu, Y.; Peng, L.; Ren, H.; Gao, S. A re-crosslinkable composite gel based on curdlan for lost circulation control. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 371, 121010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Fu, J.; Lebongo Eteme, Y. Research progress of hydroxyethyl cellulose materials in oil and gas drilling and production. Cellulose 2023, 30, 10681–10700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Kang, Y.; Xu, C.; Lin, C.; Xie, Z.; You, L.; Huang, T.; You, Z. A Quantitative Evaluation Method for Lost Circulation Materials in Bridging Plugging Technology for Deep Fractured Reservoirs. SPE J. 2025, 30, 4706–4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhong, J.; Luo, S.; Zhu, M.; Liu, L.; Bai, Y.; Kang, Y.; Tang, X.; You, Z. Mechanism and Material Development of Temperature Activated Bonding Plugging for Lost Circulation Control in Deep Fractured Formations. SPE J. 2025, 30, 6097–6111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Dahi Taleghani, A.; Salehi, S.; Li, G.; Ezeakacha, C. Smart lost circulation materials for productive zones. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2018, 9, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chausse, V.; Iglesias, C.; Bou-Petit, E.; Ginebra, M.-P.; Pegueroles, M. Chemical vs thermal accelerated hydrolytic degradation of 3D-printed PLLA/PLCL bioresorbable stents: Characterization and influence of sterilization. Polym. Test. 2023, 117, 107817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Li, M. Fractured Lost Circulation Control: Quantitative Design and Experimental Study of Multi-Sized Rigid Bridging Plugging Material. Processes 2025, 13, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Kang, Y.; Lin, C.; Xu, C.; Zhang, L.; You, L. A novel experimental study on plugging performance of lost circulation materials for pressure-sensitive fracture. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 242, 213214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Yu, J.; Xie, L. Synthesis and Evaluation of Plugging Gel Resistant to 140 °C for Lost Circulation Control: Effective Reduction in Leakage Rate in Drilling Process. Polymers 2024, 16, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, R.; Ali, Z.; Yu, J.; Yang, K.; Sun, K.; Li, X.; Lei, Y.; et al. Recent developments on epoxy-based syntactic foams for deep sea exploration. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 56, 2037–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, M.; Tang, L.; Shi, D.; Lam, E.; Bae, J. 3D shape morphing of stimuli-responsive composite hydrogels. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 5989–6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Geng, J.; Wang, Y.; Gu, H. PVA/gelatin/β-CD-based rapid self-healing supramolecular dual-network conductive hydrogel as bidirectional strain sensor. Polymer 2022, 246, 124769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Sharma, H.; Mohanty, K.K. Chemical Flooding in Low Permeability Carbonate Rocks. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Antonio, TX, USA, 9–11 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Soulat, A.; Douarche, F.; Flauraud, E. A modified well index to account for shear-thinning behaviour in foam EOR simulation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 191, 107146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, J.G.; Iza, P.; Dominguez, H.; Schott, E.; Zarate, X. Effect of Triton X-100 surfactant on the interfacial activity of ionic surfactants SDS, CTAB and SDBS at the air/water interface: A study using molecular dynamic simulations. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 603, 125284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zukowski, B.; dos Santos, E.R.F.; dos Santos Mendonça, Y.G.; de Andrade Silva, F.; Toledo Filho, R.D. The durability of SHCC with alkali treated curaua fiber exposed to natural weathering. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 94, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Lang, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, R.; Bai, Y.; Sun, J. Fracture plugging performance and mechanism of adhesive material in bridging system during well drilling. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 247, 213729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yin, D.; Ren, J.; Han, B.; Qin, S. A novel thixotropic structural dynamics model of water-based drilling fluids. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 234, 212585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Huang, W.; Zhu, J.; Li, C.; Qin, G.; Lu, H. Preparation and Physicochemical Properties of High-Temperature-Resistant Polymer Gel Resin Composite Plugging Material. Gels 2025, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Jiang, G.; Wang, K.; Wang, J. Laponite nanoparticle as a multi-functional additive in water-based drilling fluids. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 12266–12278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, M.; Jeong, J. Preparation of Hydrogel by Crosslinking and Multi-Dimensional Applications. Gels 2025, 11, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wang, M.; Chen, Y.; Wu, L.; Yu, J.; Luo, Y. Synthesis and properties of self-healing hydrogel plugging agent. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, P.; Pei, H. Investigation of Polymer Gel Reinforced by Oxygen Scavengers and Nano-SiO2 for Flue Gas Flooding Reservoir. Gels 2023, 9, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, B.; Jiang, G.; Hu, W.; Yang, J.; Luo, Y. Study on high-temperature delayed-crosslinking polyacrylamide gel plugging agent. Drill. Fluid Complet. Fluid 2019, 36, 679–682. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova, M.; Cheng, M.; Trejo, J.; Willhite, G.P. Delayed HPAM gelation via transient sequestration of chromium in polyelectrolyte complex nanoparticles. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 4398–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Hou, J.; Wei, Q.; Bai, B. Development of a high-temperature-resistant polymer-gel system for conformance control in Jidong Oil Field. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2019, 22, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T. Study on xanthan-gum-thickened in-situ crosslinking temporary plugging system. Appl. Chem. Ind. 2018, 47, 2360–2363+2368. [Google Scholar]

- Elsharafi, M.O.; Bai, B. Experimental work to determine the effect of load pressure on the gel pack permeability of strong and weak preformed particle gels. Fuel 2017, 188, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Su, X.; Li, Y. A temperature- and salt-resistant preformed gel particle and its application. Oilfield Chem. 2007, 24, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, C.; Wang, K.; Zhao, M.; Gao, M.; Yang, Z.; Bai, B. Investigation on preparation and profile-control mechanisms of dispersed particle gels (DPG) formed from phenol-formaldehyde cross-linked polymer gel. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 6284–6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X. Study on preformed particle gel (PPG) enhanced polymer flooding. Chem. Eng. Oil Gas 2011, 40, 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhu, L. Tough, sticky and remoldable hydrophobic association hydrogel regulated by polysaccharide and sodium dodecyl sulfate as emulsifiers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 201, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ren, X.; Gao, G. Salt-inactive hydrophobic association hydrogels with fatigue-resistant and self-healing properties. Polymer 2018, 150, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; King, J.; Sokolova, A.; Tabor, R. Small-angle scattering of complex fluids in flow. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 328, 103161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Bañuelos, E.; Marín-Santibáñez, B.; Pérez-González, J. Rheo-PIV study of slip effects on oscillatory shear measurements of a yield-stress fluid. J. Rheol. 2024, 68, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; An, R.; Han, L.; Sun, J.; Zhao, C.; Bai, B. Tough hydrophobic association hydrogels with self-healing and reforming capabilities achieved by polymeric core-shell nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 99, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, I.; Cui, J.; Illeperuma, W.R.; Aizenberg, J.; Vlassak, J.J. Extremely stretchable and fast self-healing hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 4678–4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.L.; Kurokawa, T.; Kuroda, S.; Ihsan, A.B.; Akasaki, T.; Sato, K.; Haque, M.A.; Nakajima, T.; Gong, J.P. Physical hydrogels composed of polyampholytes demonstrate high toughness and viscoelasticity. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Jiang, H.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, H.; Ma, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, X.; Kang, W. Development and evaluation of organic/metal ion double crosslinking polymer gel for anti-CO2 gas channeling in high temperature and low permeability reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yang, H.; Ning, C.; Peng, L.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Shi, H.; Wang, R.; Sarsenbekuly, B.; Kang, W. Amphiphilic polymer with ultra-high salt resistance and emulsification for enhanced oil recovery in heavy oil cold recovery production. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 252, 213920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Jiang, H.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Peng, L.; Wang, R.; Li, H.; Kang, W.; Sarsenbekuly, B. Viscoelastic displacement mechanism of fluorescent polymer microspheres based on macroscopic and microscopic displacement experiments. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 042022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polymer Type | Polymer Concentration (%) | Gel Strength | Gelling Time (h) | Dehydration Rate After 7-Day Aging (%) | Storage Modulus (G′, Pa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0.3 | D | 11.0 | 14.2 | 12.3 |

| 0.6 | E | 10.2 | 12.5 | 25.6 | |

| 0.9 | F | 8.1 | 9.8 | 42.1 | |

| 1.2 | H | 6.0 | 8.5 | 62.0 | |

| 1.5 | H | 4.3 | 8.2 | 68.5 | |

| 1.8 | H | 2.1 | 10.3 | 65.2 | |

| P2 | 0.3 | - | - | - | - |

| 0.6 | C | 15.2 | 22.3 | 8.5 | |

| 0.9 | D | 12.5 | 19.8 | 18.7 | |

| 1.2 | F | 9.8 | 16.5 | 35.0 | |

| 1.5 | F | 7.2 | 15.1 | 38.2 | |

| 1.8 | G | 5.1 | 14.8 | 42.3 | |

| P3 | 0.3 | - | - | - | - |

| 0.6 | - | - | - | 5.2 | |

| 0.9 | D | 18.5 | 28.6 | 12.8 | |

| 1.2 | D | 15.3 | 25.4 | 20.0 | |

| 1.5 | E | 12.1 | 23.7 | 25.6 |

| Aldehyde Crosslinker and Concentration (%) | Hydroquinone Concentration (%) | Gelling Time (h) | Gelling Effect and Thermal Stability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde | 0.3 | 0.5 | 2.5 | Gel strength grade E, degraded at high temperature after 7 d |

| 0.6 | 2.0 | Gel strength grade F, degraded at high temperature after 7 d | ||

| 0.9 | 1.5 | Gel strength grade F, dehydration rate 20% after 7 d | ||

| S-Trioxane | 0.3 | 0.5 | 8.0 | Gel strength grade F, dehydration rate 12% after 7 d |

| 0.6 | 6.0 | Gel strength grade F, dehydration rate 12% after 7 d | ||

| 0.9 | 4.5 | Gel strength grade H, dehydration rate 10% after 7 d | ||

| HMTA | 0.3 | 0.5 | 9.0 | Gel strength grade G, dehydration rate 15% after 7 d |

| 0.6 | 8.0 | Gel strength grade H, dehydration rate 12% after 7 d | ||

| 0.9 | 6.5 | Gel strength grade H, dehydration rate 14% after 7 d | ||

| Crosslinker and Concentration (%) | Polymer Concentration (%) | Gelling Time (h) | Gelation Quality and Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% Phenol + 0.6% S-Trioxane | 0.3 | - | Strength too weak |

| 0.6 | - | ||

| 0.9 | - | ||

| 1.2 | - | ||

| 1.5 | - | ||

| 0.5% Hydroquinone + 0.6% S-Trioxane | 0.3 | 11 | Gel strength grade D, dehydration < 15% after 7 d |

| 0.6 | 10 | Gel strength grade E, dehydration < 15% after 7 d | |

| 0.9 | 8 | Gel strength grade F, dehydration < 15% after 7 d | |

| 1.2 | 6 | Gel strength grade G, dehydration < 10% after 7 d | |

| 1.5 | 4 | Gel strength grade G, dehydration < 10% after 7 d | |

| 0.5% Catechol + 0.6% S-Trioxane | 0.3 | 18 | Gel strength grade D, dehydration rate 35% after 7 d |

| 0.6 | 16 | Gel strength grade D, dehydration rate 30% after 7 d | |

| 0.9 | 13 | Gel strength grade D, dehydration rate 30% after 7 d | |

| 1.2 | 10 | Gel strength grade E, dehydration rate 25% after 7 d | |

| 1.5 | 8 | Gel strength grade F, dehydration rate 15% after 7 d |

| Sample | Length (cm) | Temp (°C) | Aging (d) | Pressure Gradient (MPa/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Water flood) | 50 | 120 | 1.0 | 0.24 |

| 2 (Water flood) | 50 | 120 | 3.0 | 0.22 |

| 3 (Water flood) | 50 | 140 | 1.0 | 0.21 |

| 4 (Water flood) | 50 | 140 | 3.0 | 0.19 |

| 5 (Gas flood) | 50 | 120 | 1.0 | 0.17 |

| 6 (Gas flood) | 50 | 120 | 3.0 | 0.15 |

| 7 (Gas flood) | 50 | 140 | 1.0 | 0.14 |

| 8 (Gas flood) | 50 | 140 | 3.0 | 0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Yao, X.; Xi, C.; Liu, K.; Ren, T. Preparation and Performance Characterization of Thixotropic Gelling Materials with High Temperature Stability and Wellbore Sealing Properties. Polymers 2025, 17, 3343. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243343

Liu Y, Yao X, Xi C, Liu K, Ren T. Preparation and Performance Characterization of Thixotropic Gelling Materials with High Temperature Stability and Wellbore Sealing Properties. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3343. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243343

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yingbiao, Xuyang Yao, Chuanming Xi, Kecheng Liu, and Tao Ren. 2025. "Preparation and Performance Characterization of Thixotropic Gelling Materials with High Temperature Stability and Wellbore Sealing Properties" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3343. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243343

APA StyleLiu, Y., Yao, X., Xi, C., Liu, K., & Ren, T. (2025). Preparation and Performance Characterization of Thixotropic Gelling Materials with High Temperature Stability and Wellbore Sealing Properties. Polymers, 17(24), 3343. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243343