Next-Generation Electrically Conductive Polymers: Innovations in Solar and Electrochemical Energy Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Imperative for Advanced Energy Materials

1.1. Global Energy Landscape and Sustainability Challenges

1.2. Emergence of Electrically Conductive Polymers

1.3. Scope and Organization of This Review

2. Fundamental Principles of Electrical Conductivity in Conjugated Polymers

2.1. Molecular Origins of Electronic Conductivity

2.2. Doping Mechanisms and Charge Carrier Generation

2.3. Charge Transport Mechanisms

2.4. Structure-Property Relationships

3. Synthesis Strategies for Electrically Conductive Polymers

3.1. Chemical Oxidative Polymerization

3.2. Electrochemical Polymerization

3.3. Advanced Synthetic Methodologies

4. Electrically Conductive Polymers in Photovoltaic Technologies

4.1. Fundamental Principles of Polymer-Based Photovoltaics

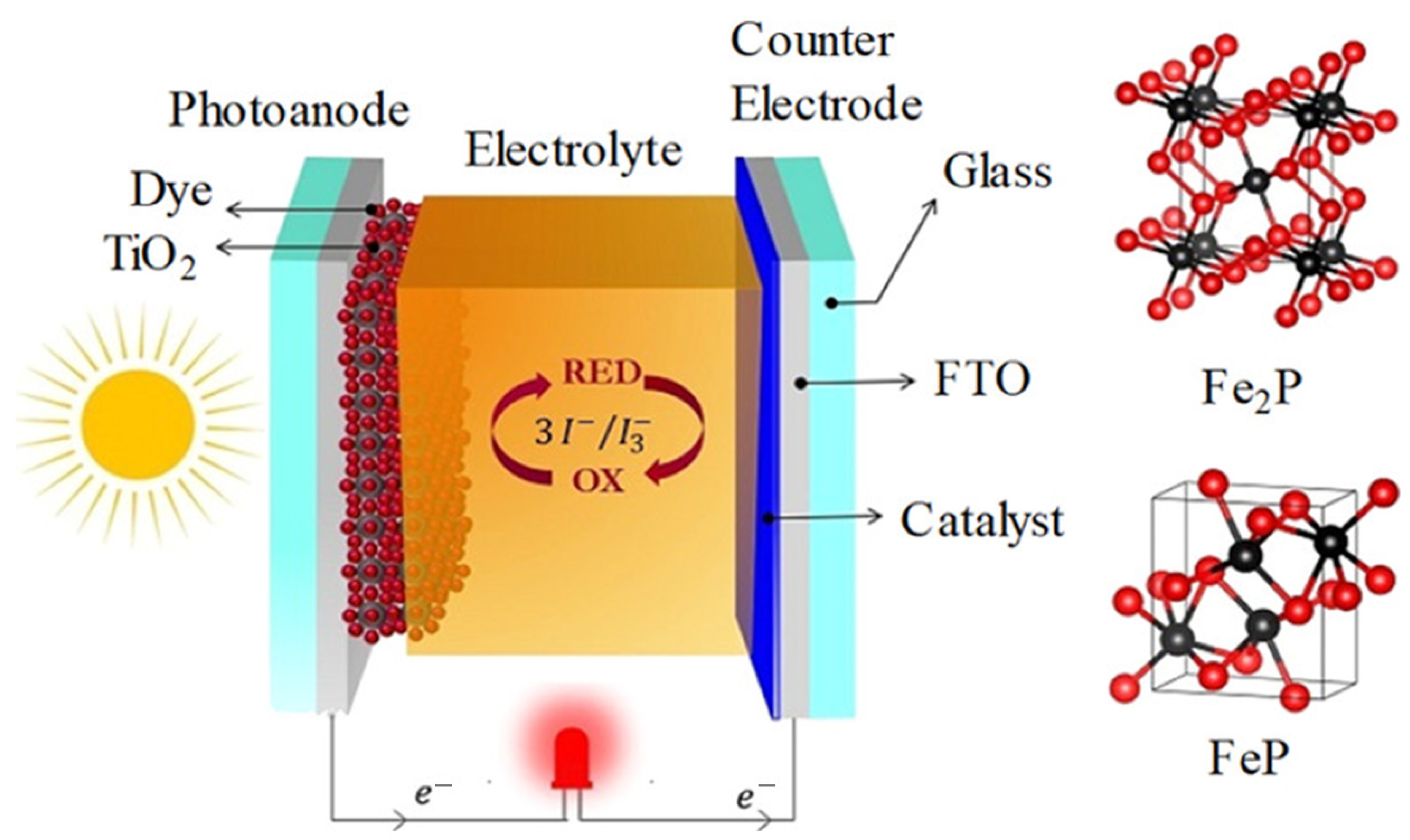

4.2. Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: Counter Electrode Applications

4.3. Composite Counter Electrodes: Synergistic Enhancements

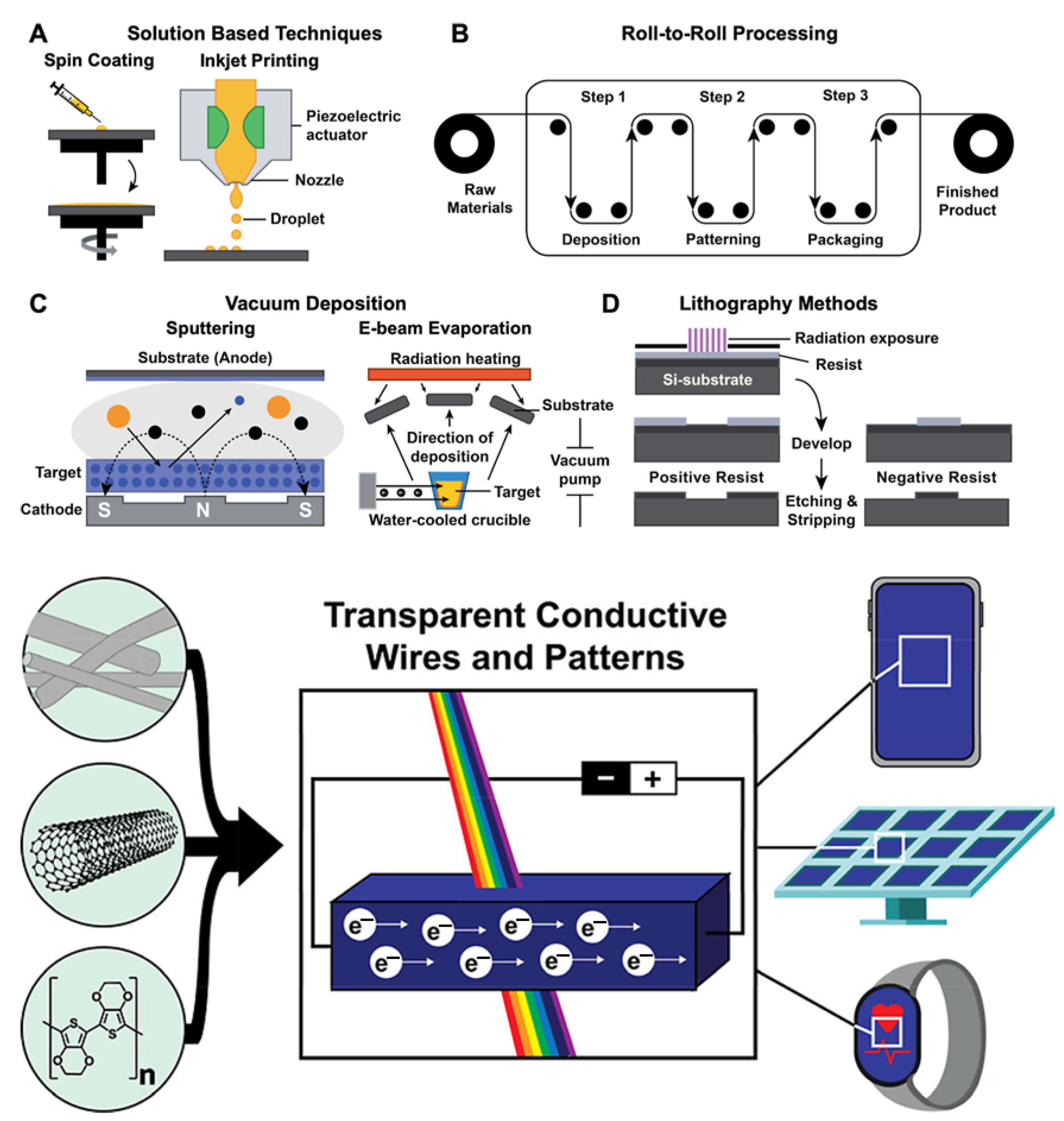

4.4. Transparent Conducting Electrodes

4.5. Hole Transport and Interface Engineering

5. Electrically Conductive Polymers in Electrochemical Energy Storage

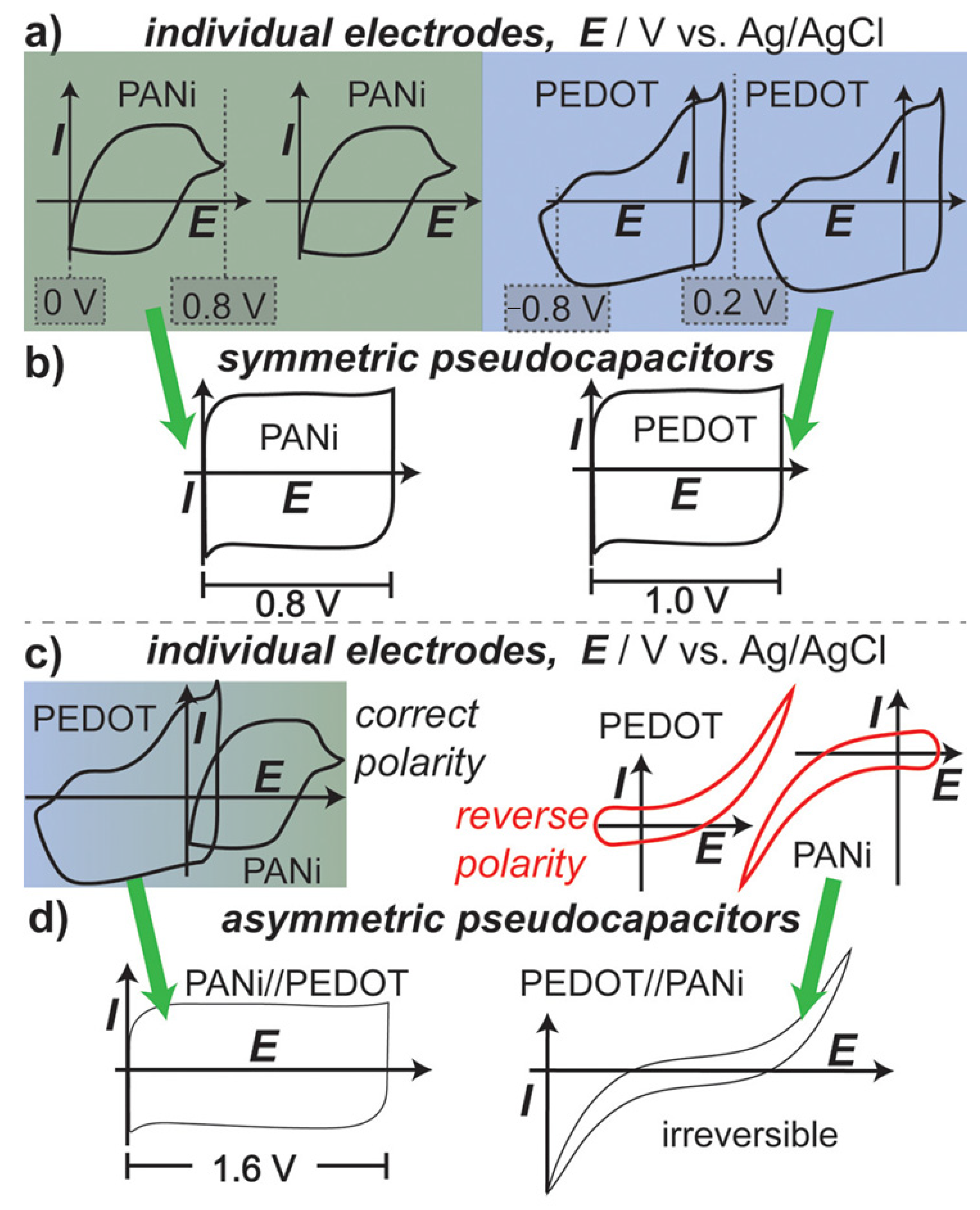

5.1. Supercapacitor Applications: Pseudocapacitive Energy Storage

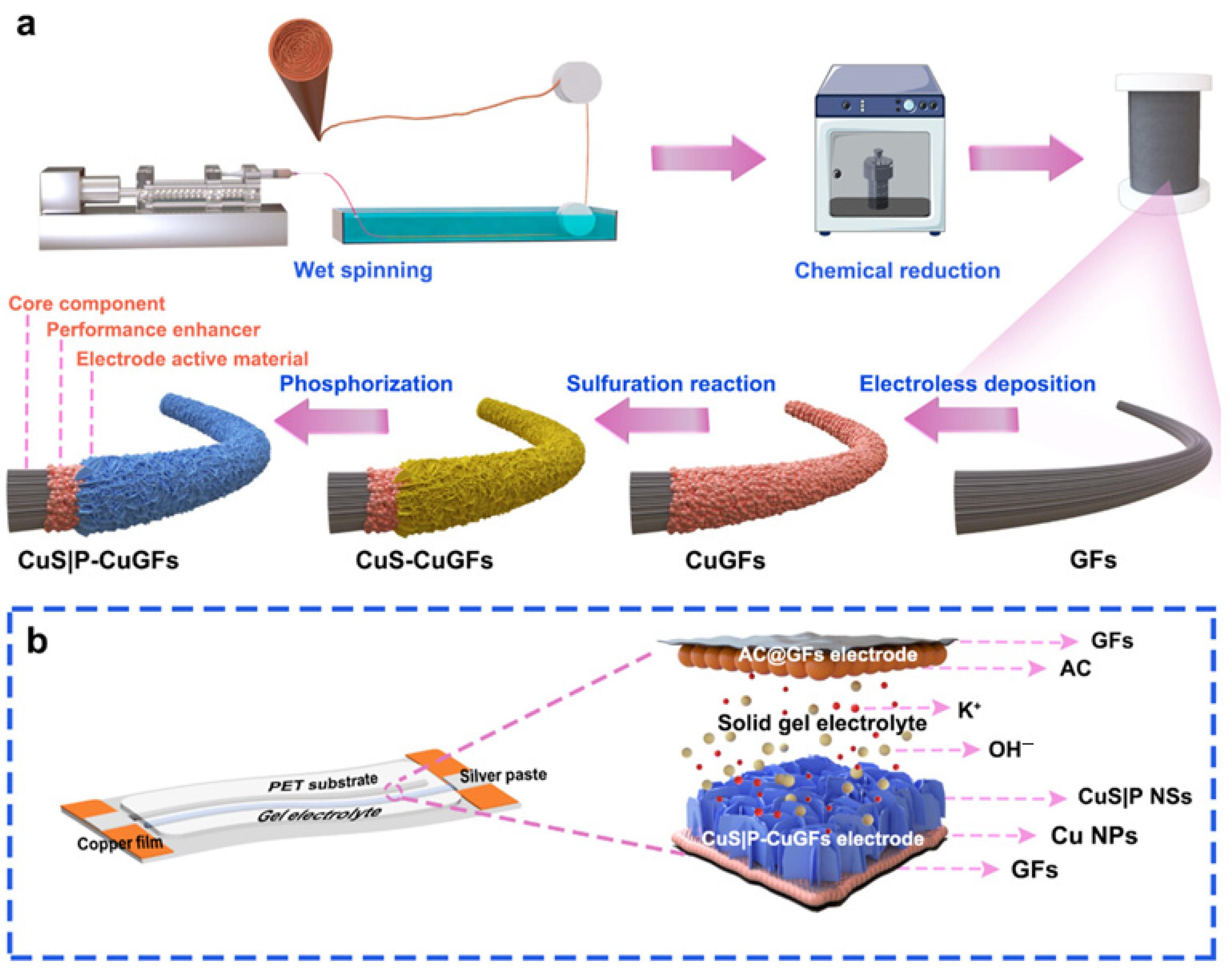

5.2. Composite Electrodes for Enhanced Performance

5.3. Lithium-Ion Battery Applications

5.4. Polymer Electrolytes and Separators

6. Advanced Composite Architectures and Multifunctional Systems

6.1. Ternary and Higher-Order Composites

6.2. Hierarchical Nanostructures

6.3. Flexible and Stretchable Energy Devices

6.4. Self-Healing and Adaptive Materials

7. Characterization Techniques and Performance Metrics

7.1. Structural and Morphological Characterization

7.2. Electrical and Electrochemical Characterization

7.3. Photovoltaic Device Characterization

8. Challenges, Opportunities and Future Perspectives

8.1. Stability and Degradation Mechanisms

8.2. Scalable Manufacturing and Processing

8.3. Environmental and Sustainability Considerations

8.4. Integration with Emerging Technologies

8.5. Fundamental Research Directions

9. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iqbal, M.Z.; Khan, S. Progress in the performance of dye sensitized solar cells by incorporating cost effective counter electrodes. Sol. Energy 2018, 160, 130–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Abraham, J.A.; Sreelekshmi, C.; Manzoor, M.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, A.K.; Fouad, D.; Kumar, Y.A.; Sharma, R. Ab-initio investigation of novel lead-free halide based Rb2CsXI6 (X = Ga, In) double perovskites: Mechanical, structural, thermoelectric, and optoelectronic potential for photovoltaics and green energy applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2024, 310, 117708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasekar, S.; Kollu, P.; Jeong, S.K.; Grace, A.N. Pt-free, low-cost and efficient counter electrode with carbon wrapped VO2(M) nanofiber for dye-sensitized solar cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, N.; Lutfullah; Perveen, T.; Pugliese, D.; Haq, S.; Fatima, N.; Salman, S.M.; Tagliaferro, A.; Shahzad, M.I. Counter electrode materials based on carbon nanotubes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benesperi, I.; Michaels, H.; Freitag, M. The researcher’s guide to solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 11903–11942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, S.; Paunović, V. Characteristics of curcumin dye used as a sensitizer in dye-sensitized solar cells. Facta Univ. Ser. Electron. Energ. 2019, 32, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, N.A.; Mehmood, U.; Zahid, H.F.; Asif, T. Nanostructured photoanode and counter electrode materials for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs). Sol. Energy 2019, 185, 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondán-Gómez, V.; Montoya De Los Santos, I.; Seuret-Jiménez, D.; Ayala-Mató, F.; Zamudio-Lara, A.; Robles-Bonilla, T.; Courel, M. Recent advances in dye-sensitized solar cells. Appl. Phys. A 2019, 125, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasajpour-Esfahani, N.; Dastan, D.; Alizadeh, A.; Shirvanisamani, P.; Rozati, M.; Ricciardi, E.; Lewis, B.; Aphale, A.; Toghraie, D. A critical review on intrinsic conducting polymers and their applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 125, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, J.M.; Armel, V.; MacFarlane, D.R. Electrodeposited PEDOT-on-plastic cathodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 5367–5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppu, S.V.; Jeyaraman, A.R.; Guruviah, P.K.; Thambusamy, S. Preparation and characterizations of PMMA–PVDF based polymer composite electrolyte materials for dye-sensitized solar cell. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2018, 18, 619–625. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.J.; Theerthagiri, J.; Nithyadharseni, P.; Arunachalam, P.; Balaji, D.; Madan Kumar, A.; Madhavan, J.; Mittal, V.; Choi, M.Y. Heteroatom-doped graphene-based materials for sustainable energy applications: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekera, S.S.B.; Perera, I.R.; Gunathilaka, S.S. Conducting polymers as cost-effective counter electrode materials in dye-sensitized solar cells. In Energy, Environment and Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 345–371. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, K.D.; Grey, C.P.; Michaelides, A. On the Physical Origins of Reduced Ionic Conductivity in Nanoconfined Electrolytes. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 13191–13201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.Y.; Omar, F.S.; Saidi, N.M.; Farhana, N.K.; Ramesh, S.; Ramesh, K. Optimization of poly(vinyl alcohol-co-ethylene)-based gel polymer electrolyte containing nickel phosphate nanoparticles for dye-sensitized solar cell application. Sol. Energy 2019, 178, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onggar, T.; Kruppke, I.; Cherif, C. Techniques and processes for the realization of electrically conducting textile materials from intrinsically conducting polymers and their application potential. Polymers 2020, 12, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luong, J.H.T.; Narayan, T.; Solanki, S.; Malhotra, B.D. Recent advances of conducting polymers and their composites for electrochemical biosensing applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2020, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Nandy, S.; Fortunato, E.; Martins, R. Polyaniline and its composites engineering: A class of multifunctional smart energy materials. J. Solid State Chem. 2023, 317, 123679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, A.; Warren, R.; Londi, G.; Kaienburg, P.; Liu, J.; Sperlich, A.; Lauritzen, A.E.; Thimm, O.; Ardavan, A.; Beljonne, D.; et al. Electron spin as fingerprint for charge generation and transport in doped organic semiconductors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 2944–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Yu, J.; Tian, Q.; Shi, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, S.; Zang, L. Application of PEDOT:PSS and its composites in electrochemical and electronic chemosensors. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namsheer, K.; Rout, C.S. Conducting polymers: A comprehensive review on recent advances in synthesis, properties and applications. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 5659–5697, Correction in RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 17467–17470. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4RA90058H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Yang, C.; Yuan, J.; Li, H.; Yuan, X.; Li, M. An overview of the preparation and application of counter electrodes for DSSCs. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 13256–13280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, M.A.K.L.; Kumari, J.M.K.W.; Senadeera, G.K.R.; Anwar, H. Low-cost, platinum-free counter electrode with reduced graphene oxide and polyaniline embedded SnO2 for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Sol. Energy 2021, 230, 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H.; Park, S.; Chung, S.; Ok, E.; Kim, B.J.; Jang, J.D.; Kang, B.; Cho, K. Multiscale Analyses of Strain-Enhanced Charge Transport in Conjugated Polymers. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 31332–31348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawo, C.; Iyer, P.K.; Chaturvedi, H. Carbon nanotubes/PANI composite as an efficient counter electrode material for dye-sensitized solar cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2023, 297, 116722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Farooq, E.; Nazar, R.; Mehmood, U.; Fareed, I. Development of multi-walled carbon nanotube/polythiophene (MWCNT/PTh) nanocomposites for platinum-free dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs). Sol. Energy 2022, 245, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, D.J.; Ra, H.; Rhee, S.W. Concentration effect of multiwalled carbon nanotube and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polymerized with poly(4-styrenesulfonate) conjugated film on the catalytic activity for counter electrode in dye-sensitized solar cells. Renew. Energy 2013, 50, 692–700. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, H.; Qin, S.; Mao, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, R.; Wan, L.; Xu, J.; Miao, S. Axle-sleeve structured MWCNTs/polyaniline composite film as cost-effective counter-electrodes for high efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 121, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Ma, T. Recent progress of counter electrode catalysts in dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 16727–16742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, J.; Frontana-Uribe, B.A.; Ludwigs, S. Electrochemistry of conducting polymers—Persistent models and new concepts. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4724–4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrijevic, N.M.; Tepavcevic, S.; Liu, Y.; Rajh, T.; Silver, S.C.; Tiede, D.M. Nanostructured TiO2/polypyrrole for visible light photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 15540–15544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, S.; Han, R.; Feng, T.; Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; He, T. The working mechanism and performance of polypyrrole as a counter electrode for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 12805–12811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.T.; Lee, C.P.; Fan, M.S.; Chen, P.Y.; Vittal, R.; Ho, K.C. Ionic liquid-doped poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) counter electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells: Cationic and anionic effects on the photovoltaic performance. Nano Energy 2014, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Xia, Z.; Dai, L. A metal-free bifunctional electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Theerthagiri, J.; Lee, Y.; Choi, M.Y. Architecting the AuPt alloys for hydrazine oxidation as an anolyte in fuel cell: Comparative analysis of hydrazine splitting and water splitting for energy-saving H2 generation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 316, 121603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tang, Q.; He, B.; Yu, L. Cost-Effective, Transparent Iron Selenide Nanoporous Alloy Counter Electrode for Bifacial Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell. J. Power Sources 2015, 282, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L. Conjugated and Fullerene-Containing Polymers for Electronic and Photonic Applications: Advanced Syntheses and Microlithographic Fabrications. J. Macromol. Sci. Polym. Rev. 1999, 39, 273–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-thabit, N.Y. Chemical Oxidative Polymerization of Polyaniline: A Practical Approach for Preparation of Smart Conductive Textiles. J. Chem. Educ. 2016, 93, 1606–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Jiao, Y.; Jaroniec, M.; Qiao, S.Z. Sulfur and nitrogen dual-doped mesoporous graphene electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction with synergistically enhanced performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11496–11500. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, S.B.; Marif, R.B.; Brza, M.A.; Hassan, A.N.; Ahmad, H.A.; Faidhalla, Y.A.; Kadir, M.F.Z. Structural, Thermal, Morphological and Optical Properties of PEO Filled with Biosynthesized Ag Nanoparticles: New Insights to Band Gap Study. Results Phys. 2019, 13, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; More, K.L.; Johnston, C.M.; Zelenay, P. High-performance electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction derived from polyaniline, iron, and cobalt. Science 2011, 332, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Tang, Q.; He, B.; Li, R.; Yu, L. Bifacial Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells with Enhanced Rear Efficiency and Power Output. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 15127–15133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, M.; Chaubey, A.; Malhotra, B.D. Application of Conducting Polymers to Biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2002, 17, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Liang, H.; Parvez, K.; Zhuang, X.; Feng, X.; Müllen, K. Nitrogen-doped carbon nanosheets with size-defined mesopores as highly efficient metal-free catalyst for oxygen reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1570–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, M.; Wang, X.; Su, Y.; Diao, G.; Wang, C. In Situ Electrochemical Polymerized Bipolar-Type Poly (1, 5-Diaminonaphthalene) Cathode for High-Performance Aqueous Zinc- Organic Batteries. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 14928–14938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.S.; Kim, C.; Ko, J.; Im, S.S. Spherical Polypyrrole Nanoparticles as a Highly Efficient Counter Electrode for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 8146–8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Tang, Q.; Lan, Z.; Li, P.; Lin, J.; Fan, L. Application of Microporous Polyaniline Counter Electrode for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Electrochem. Commun. 2008, 10, 1299–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hreid, T.; Li, X.; Guo, W.; Wang, L.; Shi, X.; Su, H.; Yuan, Z. Nanostructured Polyaniline Counter Electrode for Dye-Sensitised Solar Cells: Fabrication and Investigation of Its Electrochemical Formation Mechanism. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 3664–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, M.; Cullen, D.A.; Hwang, S.; Wang, M.; Li, B.; Liu, K.; Karakalos, S.; Lucero, M.; Zhang, H. Atomically dispersed manganese catalysts for oxygen reduction in proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Mei, X.; Sun, K.; Ouyang, J. Conducting Polymer/Carbon Nanotube Composite as Counter Electrode of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93, 143103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Chiu, W.H.; Wei, H.Y.; Hu, C.W.; Suryanarayanan, V.; Hsieh, W.F.; Ho, K.C. Effects of Mesoscopic Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene) Films as Counter Electrodes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Thin Solid Films 2010, 518, 1716–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, A.; Chouki, T.; Atli, A.; Harb, M.; Verbruggen, S.W.; Ninakanti, R.; Emin, S. Efficient Iron Phosphide Catalyst as a Counter Electrode in Dye- Sensitized Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 10618–10626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shown, I.; Ganguly, A.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, K.H. Conducting Polymer-Based Flexible Supercapacitor. Energy Sci. Eng. 2015, 3, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Byun, S.; Choi, J.; Hong, S.; Ryou, M.H.; Lee, Y.M. Elucidating the Polymeric Binder Distribution within Lithium-Ion Battery Electrodes Using SAICAS. ChemPhysChem 2018, 19, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, R.; Wei, L. Vinyltriethoxysilane Crosslinked Poly(acrylic acid sodium) as a Polymeric Binder for High-Performance Silicon Anodes in Lithium-Ion Batteries. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 29230–29236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noerochim, L.; Wang, J.Z.; Chou, S.L.; Li, H.J.; Liu, H.K. SnO2-Coated Multiwall Carbon Nanotube Composite Anode Materials for Rechargeable Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 56, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, C. A Polymer Scaffold Binder Structure for High Capacity Silicon Anode of Lithium-Ion Battery. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 1428–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Tang, R.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, F.; Tang, G.; Wang, Y.; Pang, A.; Li, W.; et al. Polydopamine Blended with Polyacrylic Acid for Silicon Anode Binder with High Electrochemical Performance. Powder Technol. 2021, 388, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Niu, S.; Zhao, F.; Tang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Su, W.; Wei, L.; Tang, G.; Wang, Y.; Pang, A.; et al. A High-Performance Polyurethane–Polydopamine Polymeric Binder for Silicon Microparticle Anodes in Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 7571–7581. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, H.Y.; Wang, C.; Su, Z.; Chen, S.; Chen, H.; Qian, S.; Li, D.S.; Yan, C.; Kiefel, M.; Lai, C.; et al. Amylopectin from Glutinous Rice as a Sustainable Binder for High-Performance Silicon Anodes. Energy Environ. Mater. 2021, 4, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, N.; Palma, J.; Marcilla, R. Macromolecular Engineering of Poly(Catechol) Cathodes towards High-Performance Aqueous Zinc–Polymer Batteries. Polymers 2021, 13, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, K.L.; Russo, A.J.; Braunschweig, A.B. Chemistry, Properties, and Patterning of Transparent and Conductive Materials. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 19207–19225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazda, T.; Capková, D.; Jaššo, K.; Straková, A.F.; Shembel, E.; Markevich, A.; Sedlaříková, M. Carrageenan as an Ecological Alternative to Polyvinylidene Fluoride Binder for Li–S Batteries. Materials 2021, 14, 5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Yun, D.H.; Hwang, I.; Seo, J.K.; Kang, J.; Noh, G.; Choi, S.; Choi, J.W. Carrageenan as a Sacrificial Binder for 5 V LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 Cathodes in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2303787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilinskaite, S.; Reeves-McLaren, N.; Boston, R. Xanthan Gum as a Water-Based Binder for P3-Na2/3Ni1/3Mn2/3O2. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 909486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A.M.; Santino, L.M.; Lu, Y.; Acharya, S.; Arcy, J.M.D. Conducting Polymers for Pseudocapacitive Energy Storage. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 5989–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J. Application of Intrinsically Conducting Polymers in Flexible Electronics. Smart Mat. 2021, 2, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, M.E.; O’Mullane, A.P.; Snook, G.A. Storing Energy in Plastics: A Review on Conducting Polymers and Their Role in Electrochemical Energy Storage. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 11611–11626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Dai, F.; Cai, M. Opportunities and Challenges of High-Energy Lithium Metal Batteries for Electric Vehicle Applications. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 3140–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, T.; Reddy, A.E.; Kumar, Y.A.; Cho, Y.R.; Kim, H.J. One-step synthesis and electrochemical performance of a PbMoO4/CdMoO4 composite as an electrode material for high-performance supercapacitor applications. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 10652–10660, Correction in Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 941. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9DT90290B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.D.; Ramachandran, T.; Kumar, Y.A.; Mohammed, A.A.A.; Kang, M.C. Hierarchically fabricated nanoflake-rod-like CoMoO–S supported Ni foam for high-performance supercapacitor electrode material. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2024, 185, 111735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.D.; Kumar, Y.A.; Ramachandran, T.; Al-Kahtani, A.A.; Kang, M.C. Cactus-like Ni–Co/CoMn2O4 composites on Ni foam: Unveiling the potential for advanced electrochemical materials for pseudocapacitors. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2023, 296, 116715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Shui, J.; Wang, Y.; Su, Z.; Qiu, L.; Du, P. Copper Phosphosulfide Nanosheets on Cu-Coated Graphene Fibers as Asymmetric Supercapacitor Electrodes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 12387–12398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, X. Recent materials development for Li-ion and Li–S battery separators. J. Energy Storage 2025, 112, 115541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theerthagiri, J.; Lee, S.J.; Murthy, A.P.; Madhavan, J.; Choi, M.Y. Fundamental aspects and recent advances in transition metal nitrides as electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction: A review. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2020, 24, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil Kumar, Y.; Singh, S.; Kulurumotlakatla, D.K.; Kim, H.J. A MoNiO4 flower-like electrode material for enhanced electrochemical properties via a facile chemical bath deposition method for supercapacitor applications. N. J. Chem. 2019, 44, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, J.W. Ceramic and polymeric solid electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 4554–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Yuen, P.Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, N.; Dauskardt, R.H.; Cui, Y. A silica-aerogel-reinforced composite polymer electrolyte with high ionic conductivity and high modulus. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1802661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostfeld, A.E.; Gaikwad, A.M.; Khan, Y.; Arias, A.C. High-Performance Flexible Energy Storage and Harvesting System for Wearable Electronics. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, P.; Ghosh, A. Influence of TiO2 nanoparticles on charge carrier transport and cell performance of PMMA–LiClO4 based nanocomposite electrolytes. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 260, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Keen, J.; Zhong, W.H. Simultaneous improvement in ionic conductivity and mechanical properties of multifunctional block-copolymer modified solid polymer electrolytes for lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 10163–10168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Juilfs, A.; Filler, R.; Mandal, B.K. Novel PEO-based dendronized polymers for lithium-ion batteries. Solid State Ionics 2010, 181, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluker, E.C.; Pathreeker, S.; Hosein, I.D. Polyvinylidene fluoride-based gel polymer electrolytes for calcium ion conduction: Influence of salt concentration and drying temperature on coordination environment and ionic conductivity. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 16579–16587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Chaudhary, M.L.; Martins, A.F.; Gupta, R.K. Mastering Material Insights: Advanced Characterization Techniques. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 8987–9023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, X.H.; Ulaganathan, M.; Babu, R.S.; Rajendran, S. Evaluation of lithium ion conduction in PAN/PMMA-based polymer blend electrolytes for Li-ion battery applications. Ionics 2012, 18, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ruan, X.; Jiang, S.; Zou, X.; Yuan, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, Z.; Wei, D.; et al. Artificial intelligence in rechargeable battery: Advancements and prospects. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 73, 103860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, M.A.C.; Huck, W.T.S.; Genzer, J.; Müller, M.; Ober, C.; Stamm, M.; Sukhorukov, G.B.; Szleifer, I.; Tsukruk, V.V.; Urban, M.; et al. Emerging applications of stimuli-responsive polymer materials. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category/Material System | Key Structural Features | Charge Transport/Conductivity | Functional Advantages | Main Limitations | Typical Applications | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small-Molecule OSCs (e.g., ZnPc:F6-TCNNQ) | Integer charge transfer; polaron formation; dopant–host interactions | CT-limited conductivity; low activation energy (~5–233 meV) | High doping efficiency; clear spin signatures | Dopant aggregation; Coulomb binding | Organic electronics, sensors | [19] |

| Rigid Conjugated Polymers (e.g., DPP-DTT) | High backbone rigidity; strong π–π stacking | High baseline mobility, limited stretch response | Strong crystallinity; efficient transport | Poor stretchability | OFETs, thin-film electronics | [24] |

| Polyaniline/Conducting Polymers | π-conjugated backbone; acid doping | High conductivity when protonated | Low-cost; textile integration | Exothermic polymerization; variable uniformity | Wearables, pseudocapacitors | [38] |

| Electropolymerized Polymers (e.g., PDAN-1) | Controlled growth; extended conjugation | High specific capacity (243 mAh g−1) | Superior stability and conductivity | Requires electrochemical setup | Aqueous batteries, hybrid capacitors | [45] |

| Metal Phosphides (Fe2P, FeP) | High catalytic active-site density | Good I3− reduction kinetics | Pt-free, low-cost catalysts | Performance varies with stoichiometry | DSSC counter electrodes | [52] |

| Hydrogels—Nanocomposite | Polymer + CNT/graphene/clay | High conductivity (with fillers) | Multifunctional, tunable | Dispersion challenges | Flexible electronics, biosensors | [62] |

| Hydrogels—Conductive Polymer | PEDOT/PPy/PANi integrated | Very high conductivity | Great for bioelectrodes | Brittle without soft matrix | Neural interfaces, E-skins | [62,66] |

| Transparent Conductors (ITO, FTO, AZO) | Metal oxide networks | Rs as low as <10 Ω/sq | High transparency | Vacuum deposition needed | PVs, displays, smart windows | [73] |

| Metal Nanowire Networks (Ag NWs) | Percolating metal networks | High conductivity | Printable, transparent | Junction resistance, corrosion | Wearables, touch sensors | [73] |

| Carbon Nanomaterials (CNT, graphene) | 1D/2D sp2 networks | Moderate conductivity | Ultra-thin, stretchable | Higher sheet resistance | Soft electronics | [62] |

| Flexible Li-ion Batteries | Graphite/LCO thin layers | High areal capacity | Thin, flexible | Limited by encapsulation | Wearable medical devices | [79] |

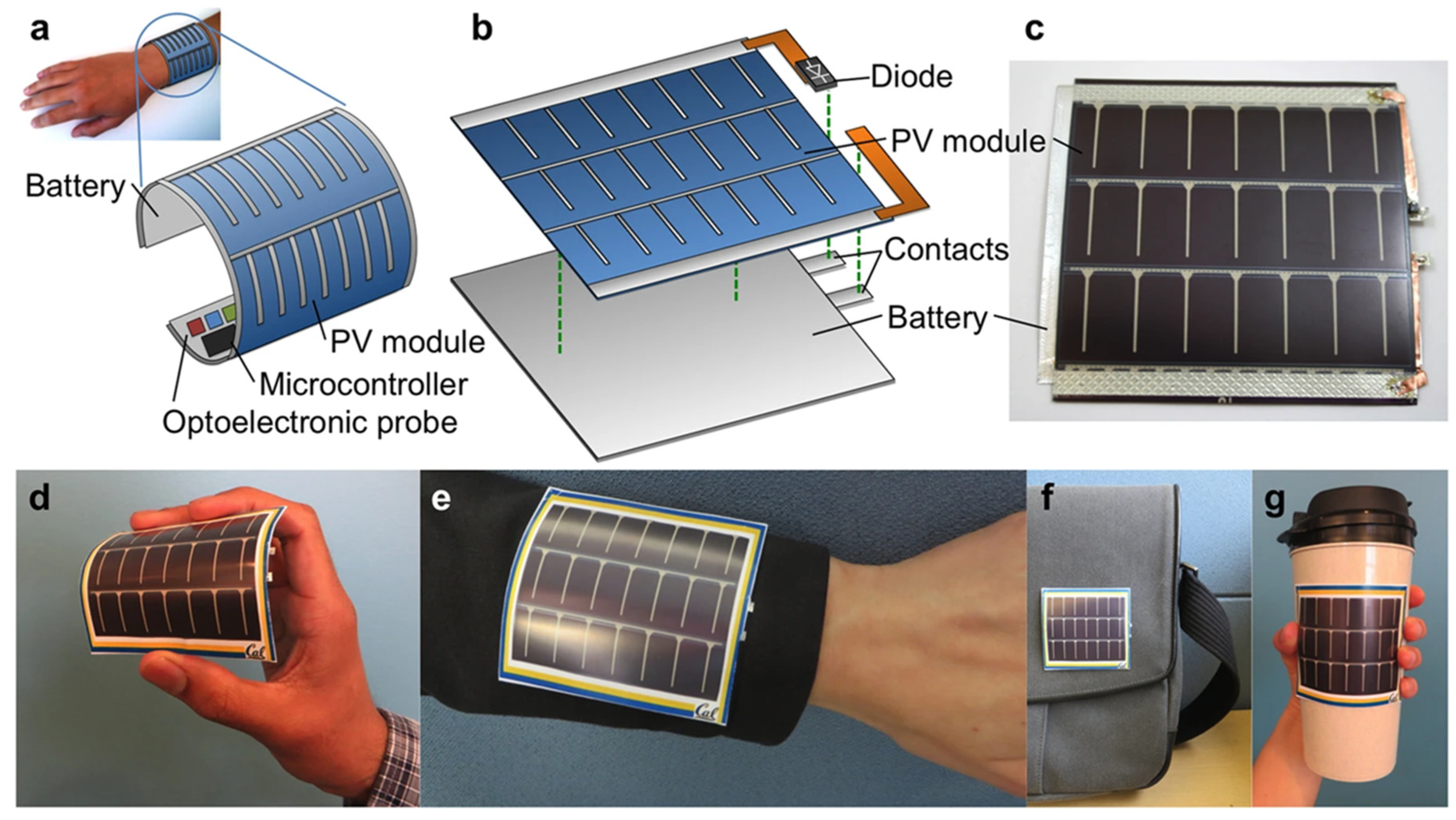

| Integrated PV–Battery Systems | Laminated flexible stack | Stable SOC with matched duty cycle | Continuous self-charging | Requires load optimization | Pulse oximeters, e-textiles | [79] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Periyasamy, T.; Asrafali, S.P.; Lee, J. Next-Generation Electrically Conductive Polymers: Innovations in Solar and Electrochemical Energy Devices. Polymers 2025, 17, 3331. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243331

Periyasamy T, Asrafali SP, Lee J. Next-Generation Electrically Conductive Polymers: Innovations in Solar and Electrochemical Energy Devices. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3331. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243331

Chicago/Turabian StylePeriyasamy, Thirukumaran, Shakila Parveen Asrafali, and Jaewoong Lee. 2025. "Next-Generation Electrically Conductive Polymers: Innovations in Solar and Electrochemical Energy Devices" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3331. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243331

APA StylePeriyasamy, T., Asrafali, S. P., & Lee, J. (2025). Next-Generation Electrically Conductive Polymers: Innovations in Solar and Electrochemical Energy Devices. Polymers, 17(24), 3331. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243331