Functional Starch-Based Biopolymer Coatings for Sustainable Packaging Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Coating Preparation for Assessing the UV Protection Factor

2.1.2. Coating Preparation for Assessing Its Influence on the Mechanical Properties of Fibre-Based Substrate

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Accelerated Ageing Tests

2.2.2. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

2.2.3. Tensile Strength and Elongation at Break

2.2.4. Bursting Strength

2.2.5. Folding Endurance

2.2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

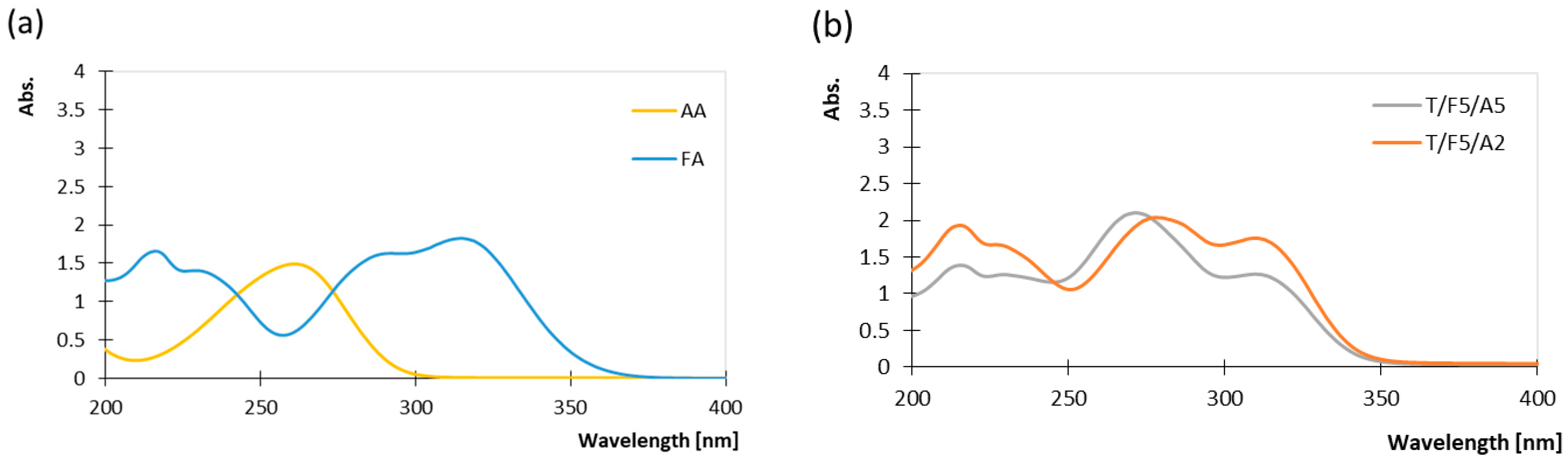

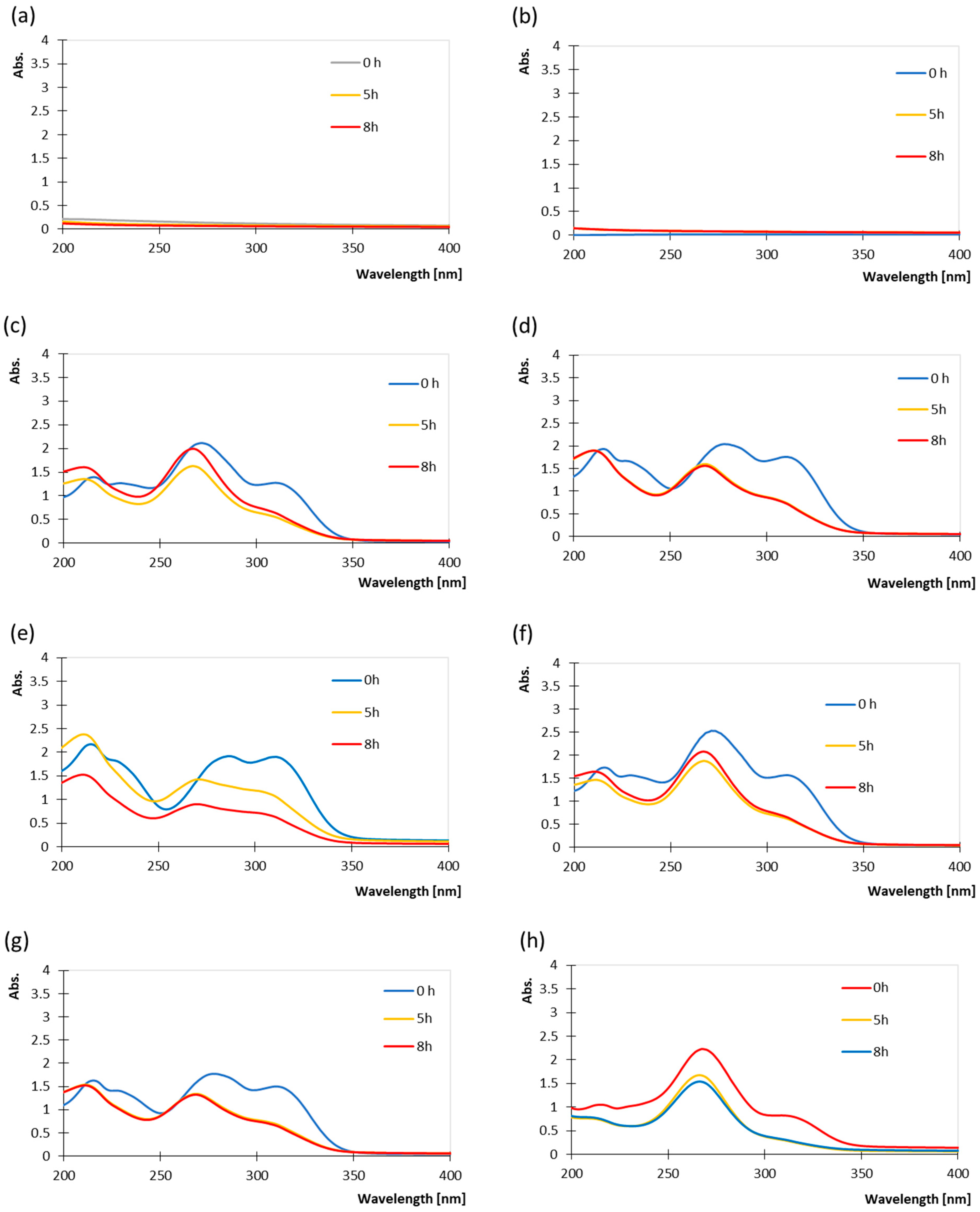

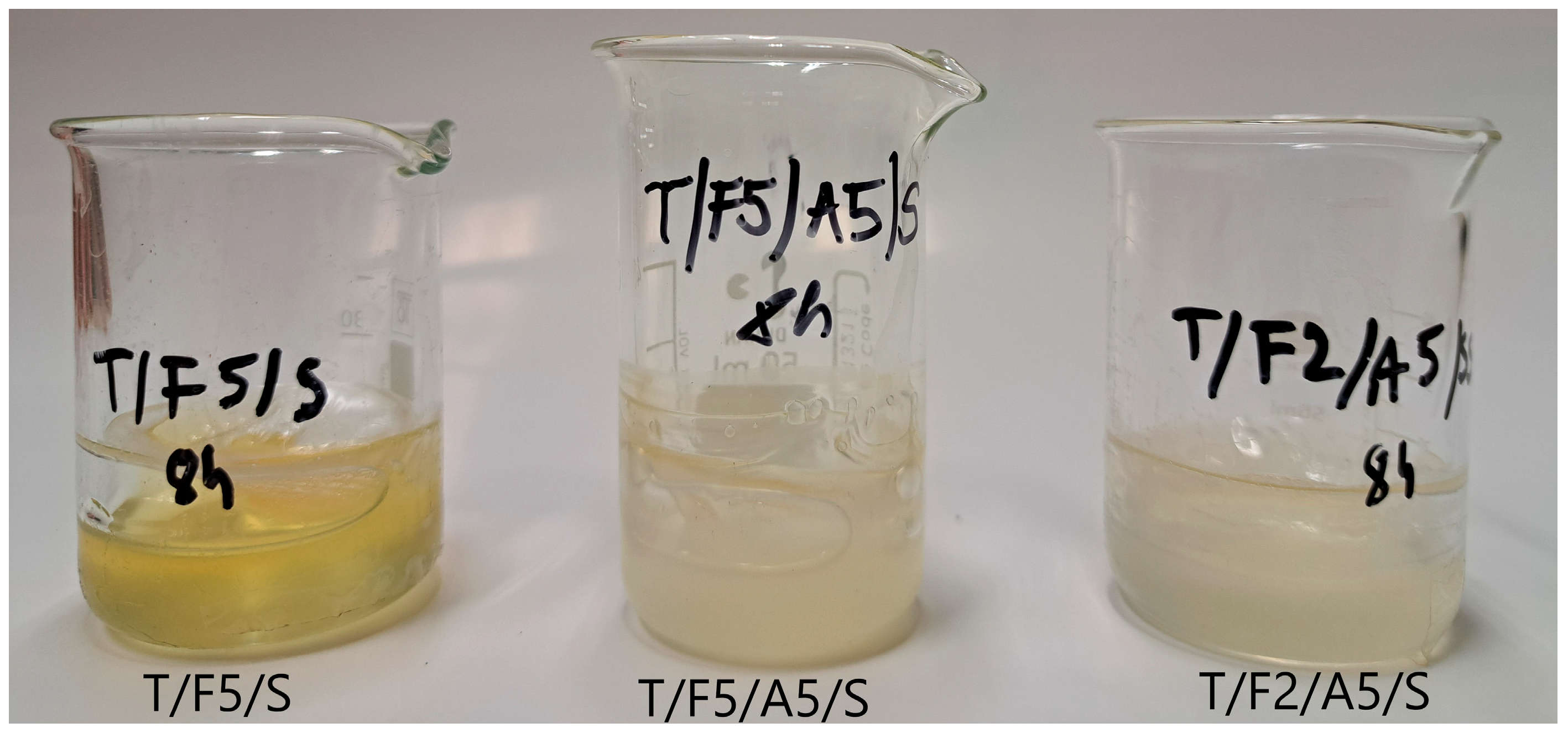

3.1. Spectroscopic Assessment of UV Exposure Effects and Protective Behaviour of Coatings

3.2. Mechanical Properties

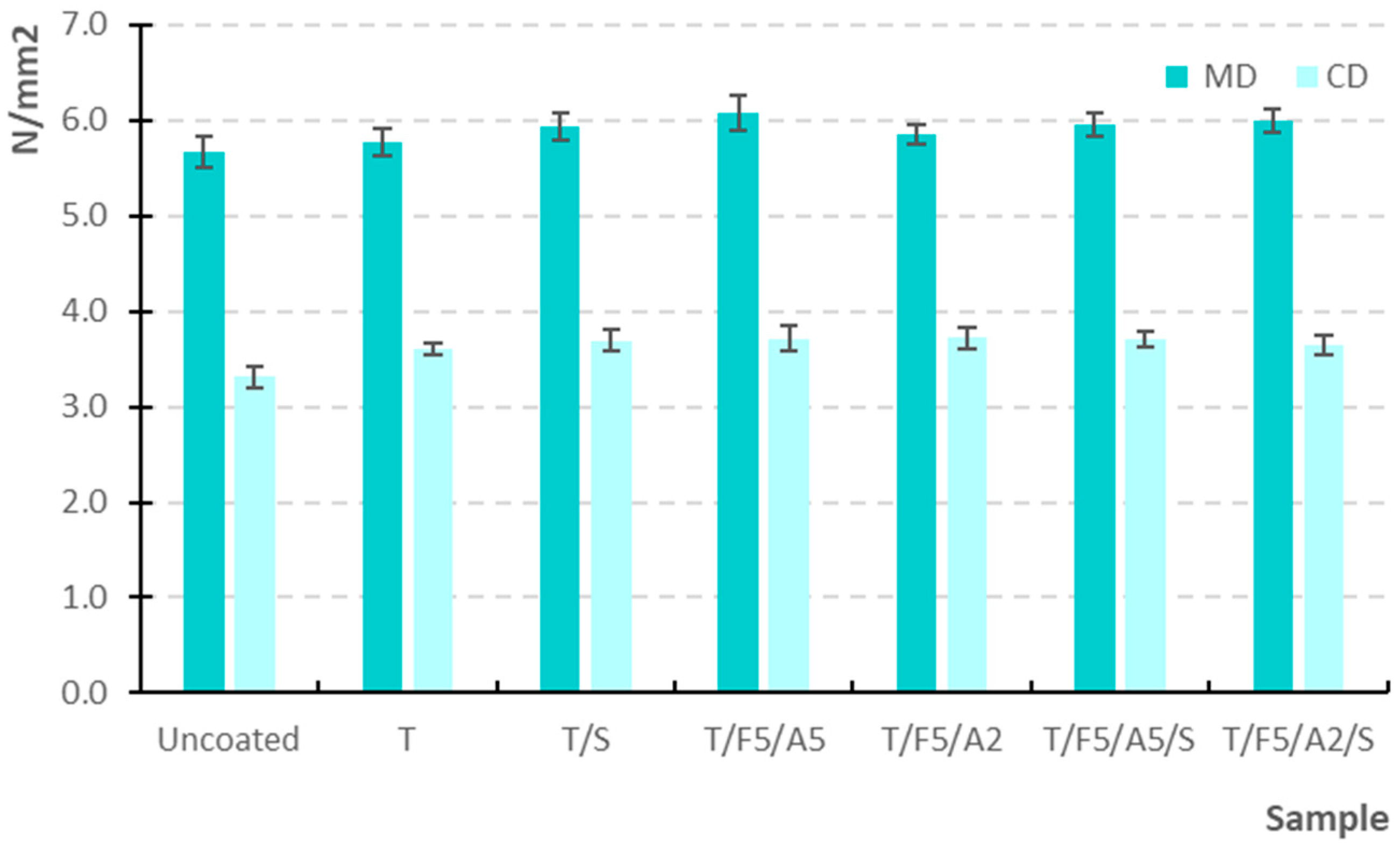

3.2.1. Tensile Strength (MD and CD)

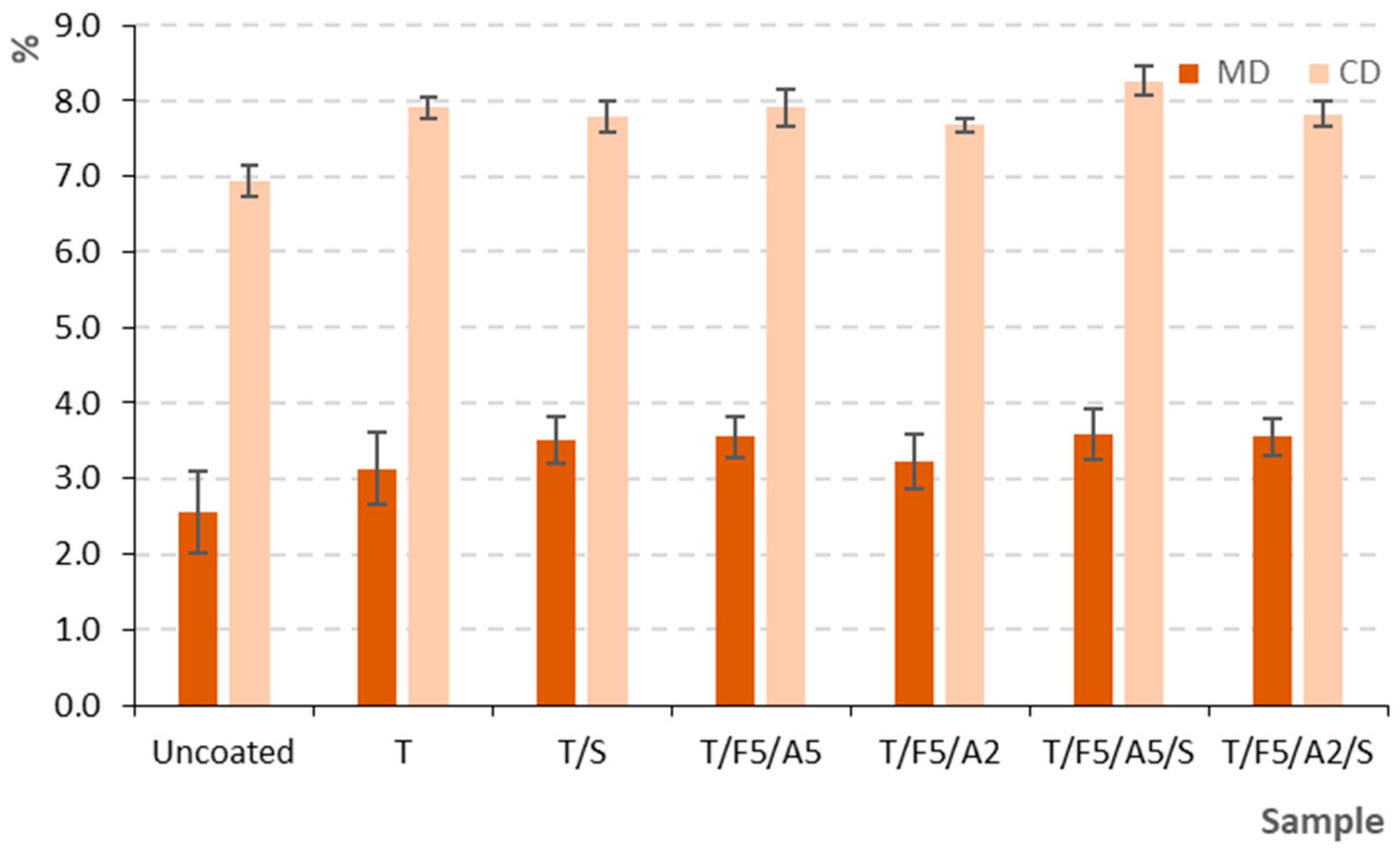

3.2.2. Elongation at Break (MD and CD)

3.2.3. Bursting Strength

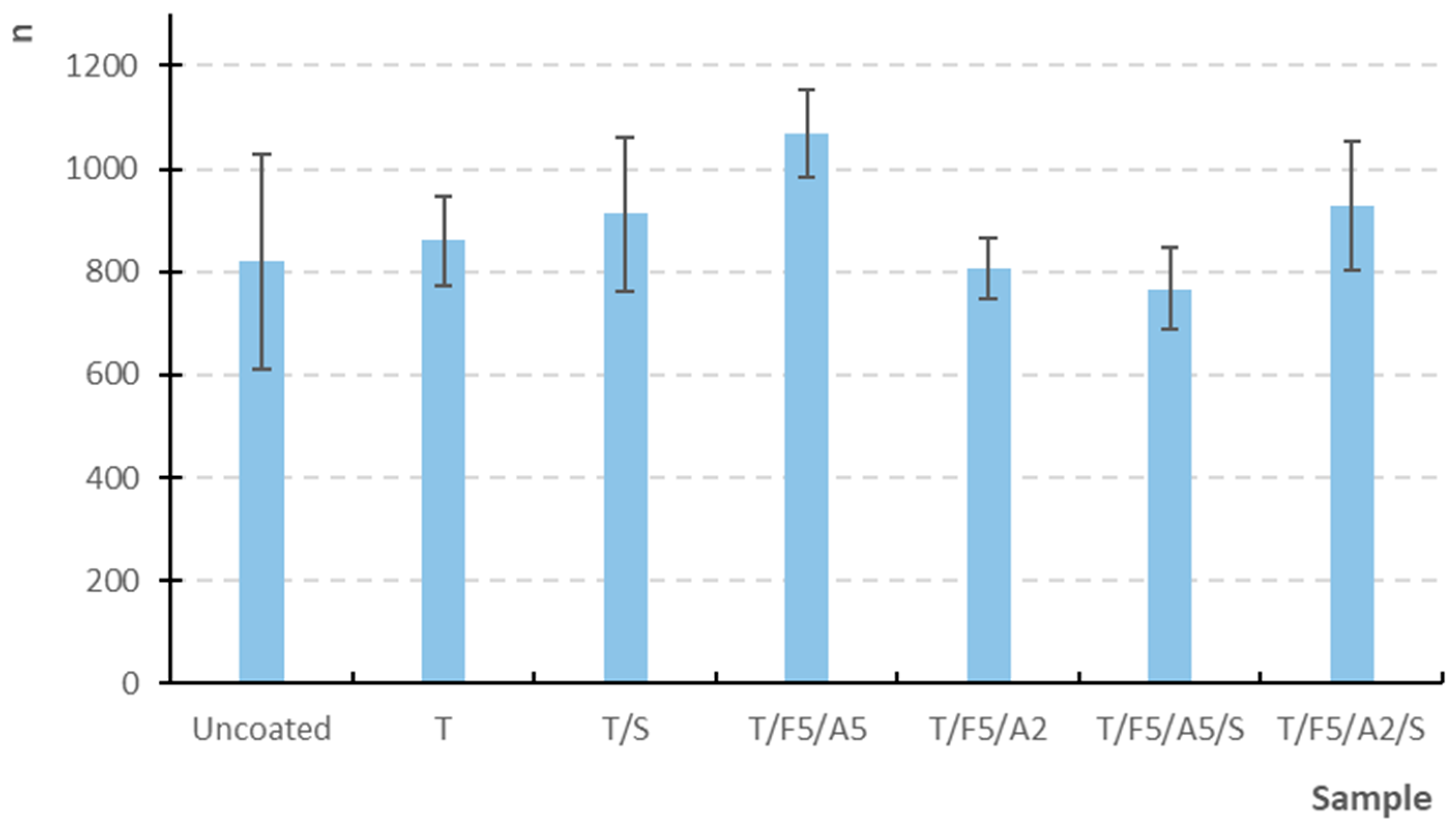

3.2.4. Folding Endurance

3.2.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| A | L-ascorbic acid |

| CD | Cross direction |

| F | Trans-ferulic acid |

| MD | Machine direction |

| Na2HPO4 | Sodium phosphate dibasic |

| NaH2PO4 | Sodium phosphate monobasic |

| PCL | Polycaprolactone |

| PLA | Polylactic acid |

| PSL | Pressure-sensitive label |

| S | D-sorbitol |

| T | Tapioca starch |

| TA | Activation temperature |

| TC | Thermochromic |

Appendix A

| Coating Abbreviation | Bursting Strength | |||||

| 0 R: 5.00 | T R: 35.50 | T/S R: 47.11 | T/F5/A5 R: 38.28 | T/F5/A2 R: 34.72 | T/F5/A5/S R: 36.89 | |

| T | 0.008737 | |||||

| T/S | 0.000023 | 1.000000 | ||||

| T/F5/A5 | 0.002469 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | |||

| T/F5/A2 | 0.012231 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | ||

| T/F5/A5/S | 0.004702 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | |

| T/F5/A2/S | 0.269667 | 1.000000 | 0.358396 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| Tensile Strength MD | ||||||

| 0 R: 13.00 | T R: 21.45 | T/S R: 41.40 | T/F5/A5 R: 53.05 | T/F5/A2 R: 28.90 | T/F5/A5/S R: 41.95 | |

| T | 1.000000 | |||||

| T/S | 0.037922 | 0.595971 | ||||

| T/F5/A5 | 0.000227 | 0.010847 | 1.000000 | |||

| T/F5/A2 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.167303 | ||

| T/F5/A5/S | 0.030835 | 0.510197 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | |

| T/F5/A2/S | 0.001799 | 0.056774 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.612834 | 1.000000 |

| Tensile Strength CD | ||||||

| 0 R: 5.65 | T R: 28.85 | T/S R: 42.25 | T/F5/A5 R: 44.20 | T/F5/A2 R: 46.60 | T/F5/A5/S R: 46.00 | |

| T | 0.226808 | |||||

| T/S | 0.001215 | 1.000000 | ||||

| T/F5/A5 | 0.000479 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | |||

| T/F5/A2 | 0.000143 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | ||

| T/F5/A5/S | 0.000195 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | |

| T/F5/A2/S | 0.026983 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 |

| Elongation at Break MD | ||||||

| 0 R: 5.70 | T R: 20.25 | T/S R: 46.00 | T/F5/A5 R: 49.00 | T/F5/A2 R: 26.25 | T/F5/A5/S R: 51.65 | |

| T | 1.000000 | |||||

| T/S | 0.000200 | 0.097974 | ||||

| T/F5/A5 | 0.000041 | 0.033257 | 1.000000 | |||

| T/F5/A2 | 0.502959 | 1.000000 | 0.630106 | 0.261065 | ||

| T/F5/A5/S | 0.000009 | 0.011770 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.110408 | |

| T/F5/A2/S | 0.000029 | 0.025967 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.212910 | 1.000000 |

| Elongation at Break MD | ||||||

| 0 R: 9.35 | T R: 42.20 | T/S R: 34.85 | T/F5/A5 R: 41.00 | T/F5/A2 R: 28.70 | T/F5/A5/S R: 57.15 | |

| T | 0.006445 | |||||

| T/S | 0.106718 | 1.000000 | ||||

| T/F5/A5 | 0.010627 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | |||

| T/F5/A2 | 0.703439 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | ||

| T/F5/A5/S | 0.000003 | 1.000000 | 0.299828 | 1.000000 | 0.037221 | |

| T/F5/A2/S | 0.093044 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.338458 |

| Folding Endurance | ||||||

| 0 R: 24.25 | T R: 35.50 | T/S R: 40.60 | T/F5/A5 R: 60.80 | T/F5/A2 R: 25.25 | T/F5/A5/S R: 18.50 | |

| T | 1.000000 | |||||

| T/S | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | ||||

| T/F5/A5 | 0.001244 | 0.114214 | 0.555554 | |||

| T/F5/A2 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.001970 | ||

| T/F5/A5/S | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.318628 | 0.000070 | 1.000000 | |

| T/F5/A2/S | 0.703439 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.919362 | 0.122183 |

References

- Okan, M.; Aydin, H.M.; Barsbay, M. Current approaches to waste polymer utilization and minimization: A review. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 94, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the Future of Plastics & Catalysing Action; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maio, F.; Rem, P.C. A Robust Indicator for Promoting Circular Economy through Recycling. J. Environ. Prot. 2015, 6, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschi, E.; Bonoli, A. The commitment of packaging industry in the framework of the european strategy for plastics in a circular economy. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnaval, L.d.S.C.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Agro-Food Waste Valorization for Sustainable Bio-Based Packaging. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Das, R.; Sangwan, S.; Rohatgi, B.; Khanam, R.; Peera, S.K.P.G.; Das, S.; Lyngdoh, Y.A.; Langyan, S.; Shukla, A.; et al. Utilisation of agro-industrial waste for sustainable green production: A review. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 4, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Singh, S.; Das, D. Environmental Impact Assessment of Active Biocomposite Packaging and Comparison with Conventional Packaging for Food Application. In Proceedings of the NordDesign 2024, Reykjavik, Iceland, 12–14 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, I.D.; Hamam, Y.; Sadiku, E.R.; Ndambuki, J.M.; Kupolati, W.K.; Jamiru, T.; Eze, A.A.; Snyman, J. Need for Sustainable Packaging: An Overview. Polymers 2022, 14, 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boopathi, S. Sustainable Biopolymers: Applications and Case Studies in Pharmaceutical, Medical, and Food Industries. In Healthcare Recommender Systems: Techniques and Recent Developments; Singh, S.P., Jain, D.K., Debayle, J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Bai, Y.; Yang, W.; Bu, K.; Tanveer, S.K.; Hai, J. Global Trends in Natural Biopolymers in the 21st Century: A Scientometric Review. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 915648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, M.F.; Campbell, J.D.; Fu, Z.; Bohling, J.; Leroux, J.G.; Mabee, W.; Robert, T. Future green chemistry and sustainability needs in polymeric coatings. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 4919–4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. Major factors affecting the characteristics of starch based biopolymer films. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 160, 110788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash Maran, J.; Sivakumar, V.; Sridhar, R.; Prince Immanuel, V. Development of model for mechanical properties of tapioca starch based edible films. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 42, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, N.A.; Farag, A.A.; Abo-dief, H.M.; Tayeb, A.M. Production of biodegradable plastic from agricultural wastes. Arab. J. Chem. 2018, 11, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Gao, R.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, Q. Applications of biodegradable materials in food packaging: A review. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 91, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famá, L.; Rojas, A.M.; Goyanes, S.; Gerschenson, L. Mechanical properties of tapioca-starch edible films containing sorbates. LWT 2005, 38, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, A.; Thuvander, F. Influence of thickness on the mechanical properties for starch films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2004, 56, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Ramakanth, D.; Akhila, K.; Gaikwad, K.K. Edible films and coatings for food packaging applications: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 20, 875–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Mártinez, L.; Pérez-Cervera, C.; Andrade-Pizarro, R. Effect of glycerol and sorbitol concentrations on mechanical, optical, and barrier properties of sweet potato starch film. NFS J. 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirbu, E.-E.; Dinita, A.; Tănase, M.; Portoacă, A.-I.; Bondarev, A.; Enascuta, C.-E.; Calin, C. Influence of Plasticizers Concentration on Thermal, Mechanical, and Physicochemical Properties on Starch Films. Processes 2024, 12, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P. Effect of plasticizer and antimicrobial agents on functional properties of bionanocomposite films based on corn starch-chitosan for food packaging applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 160, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzer, S.J.; Kulčar, R.; Vukoje, M.; Marošević, A.; Dolovski, M. Assessment of Thermochromic Packaging Prints’ Resistance to UV Radiation and Various Chemical Agents. Polymers 2023, 15, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukoje, M.; Bota, J. Effect of PCL Nanocomposite Coatings on the Recyclability of Paperboard Packaging. Recycling 2025, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, Z.; Palanisami, T. Emerging contaminants in organic recycling: Role of paper and pulp packaging. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 215, 108070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastarrachea, L.J.; Wong, D.E.; Roman, M.J.; Lin, Z.; Goddard, J.M. Active packaging coatings. Coatings 2015, 5, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Palanisamy, C.P.; Srinivasan, G.P.; Panagal, M.; Kumar, S.S.D.; Mironescu, M. A comprehensive review on starch-based sustainable edible films loaded with bioactive components for food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274, 133332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, L.d.S.; Coelho, D.B.; Veggi, P.C.; Campelo, P.H.; Albuquerque, P.M.; de Moraes, M.A. Starch as a Matrix for Incorporation and Release of Bioactive Compounds: Fundamentals and Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, F.; Ren, F.; Zhu, X.; Han, Z.; Jia, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, B.; Liu, H. The interaction between starch and phenolic acids: Effects on starch physicochemical properties, digestibility and phenolic acids stability. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 4202–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Duffy, B.; Jaiswal, S. Ferulic acid incorporated active films based on poly(lactide)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) blend for food packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 24, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Rajan, D.; Meena, D.; Srivastav, P.P. Ferulic Acid as a Sustainable and Green Crosslinker for Biopolymer-Based Food Packaging Film. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2025, 226, 2400441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longé, L.F.; Michely, L.; Gallos, A.; De Anda, A.R.; Vahabi, H.; Renard, E.; Latroche, M.; Allais, F.; Langlois, V. Improved Processability and Antioxidant Behavior of Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) in Presence of Ferulic Acid-Based Additives. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, X. Starch-Based Blends. Available online: www.rsc.org (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Do Yoon, S. Cross-linked potato starch-based blend films using ascorbic acid as a plasticizer. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 62, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 536:2019; Paper and Board—Determination of Grammage. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland.

- Avery Dennison. BD733 rCRUSH GRAPE FSC S2047N-BG45WH IMP FSC_EN; Avery Dennison: Mentor, OH, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 187:2022; Paper, Board and Pulps—Standard Atmosphere for Conditioning and Testing and Procedure for Monitoring the Atmosphere and Conditioning of Samples. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- CIE Central Bureau. Colorimetry; International Commission on Illumination: Vienna, Austria, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 1924-2:2008; Paper and Board—Determination of Tensile Properties Part 2: Constant Rate of Elongation Method (20 mm/min). International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- ISO 2758:2014; Paper—Determination of Bursting Strength. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 5626:1993; Paper—Determination of Folding Endurance. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1993.

- Aguilar, K.; Garvín, A.; Lara-Sagahón, A.V.; Ibarz, A. Ascorbic acid degradation in aqueous solution during UV-Vis irradiation. Food Chem. 2019, 297, 124864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.O.; Compton, D.L.; Appell, M. Spectroscopic and theoretical evaluation of feruloyl derivatives: Insights into their electronic properties. Results Chem. 2025, 15, 102225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danyaeva, J.; Kutsenko, S.; Kudrya, N. The change in the absorption spectra of ascorbic acid solutions, depending on their acidity. In Saratov Fall Meeting 2019: Optical and Nano-Technologies for Biology and Medicine; Tuchin, V.V., Genina, E.A., Eds.; SPIE: Saratov, Russia, 2020; p. 114571H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahiruddin, S.M.M.; Othman, S.H.; Tawakkal, I.S.M.A.; Talib, R.A. Mechanical and thermal properties of tapioca starch films plasticized with glycerol and sorbitol. Food Res. 2019, 3, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.-H.; Lin, J.-Y.; Gupta, R.D.; Tournas, J.A.; Burch, J.A.; Selim, M.A.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Grichnik, J.M.; Zielinski, J.; Pinnell, S.R. Ferulic Acid Stabilizes a Solution of Vitamins C and E and Doubles its Photoprotection of Skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 125, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Ming, J.; Yu, N. Color image quality assessment based on CIEDE2000. Adv. Multimed. 2012, 2012, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, M.; Han, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J. Starch-based Surface-sizing Agents in Paper Industry: An Overview. Pap. Biomater. 2021, 6, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.P.; Bangar, S.P.; Yang, T.; Trif, M.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, D. Effect on the Properties of Edible Starch-Based Films by the Incorporation of Additives: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Abraham, T.E. Characterisation of ferulic acid incorporated starch-chitosan blend films. Food Hydrocoll. 2008, 22, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Faro, E.; Bonofiglio, A.; Barbi, S.; Montorsi, M.; Fava, P. Polycaprolactone/Starch/Agar Coatings for Food-Packaging Paper: Statistical Correlation of the Formulations’ Effect on Diffusion, Grease Resistance, and Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2023, 15, 3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söz, Ç. Mechanical and wetting properties of coated paper sheets with varying polydimethylsiloxane molecular masses in the coating formulation. Turk. J. Chem. 2022, 46, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniar, P.S.; Hermanto, D.; Darmayanti, M.G.; Ismillayli, N. Effect of ascorbic acid concentration on the properties of biodegradable plastic based on yellow kepok banana (Musa saba) weevil starch. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2360, 050015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, Z.; Elkoun, S.; Robert, M.; Adjallé, K. A Review of the Effect of Plasticizers on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Alginate-Based Films. Molecules 2023, 28, 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laohakunjit, N.; Noomhorm, A. Effect of Plasticizers on Mechanical and Barrier Properties of Rice Starch Film. Starch-Stärke 2004, 56, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotz, H.; Klauser, M.; Rauschnabel, J.; Hauptmann, M. Influence of Moisture and Tool Temperature on the Maximum Stretch and Process Stability in High-Speed 3D Paper Forming. Materials 2025, 18, 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gücüş, M.O. Physical and Surface Properties of Food Packaging Paper Coated by Thyme Oil. BioResources 2023, 18, 7333–7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biricik, Y.; Sönmez, S.; Özden, Ö. Effects of Surface Sizing with Starch on Physical Strength Properties of Paper. Asian J. Chem. 2011, 23, 3151–3154. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265467350 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Tozluoglu, A.; Fidan, H. Effect of Size Press Coating of Cationic Starch/Nanofibrillated Cellulose on Physical and Mechanical Properties of Recycled Papersheets. BioResources 2023, 18, 5993–6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishino, M.; Hisano, K.; Kishimoto, Y.; Taguchi, R.; Shishido, A. Bending Fatigue Analysis of Various Polymer Films by Real-Time Monitoring of the Radius of Curvature and Heat Generation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 14510–14517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, S.; He, C.; Wang, Q. Cyclic Deformation and Fatigue Failure Mechanisms of Thermoplastic Polyurethane in High Cycle Fatigue. Polymers 2023, 15, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coating Abbreviation | Tapioca Starch/g | Ferulic Acid/% | Ascorbic Acid/% | D-Sorbitol/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T/F5/S | 6 | 5 | - | 15 |

| T/F5/A5/S | 6 | 5 | 5 | 15 |

| T/F2/A5/S | 6 | 2 | 5 | 15 |

| T/F5/A2/S | 6 | 5 | 2 | 15 |

| Coating Abbreviation | Tapioca Starch/g | Ferulic Acid/% | Ascorbic Acid/% | D-Sorbitol/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | 6 | - | - | - |

| T/S | 6 | - | - | 15 |

| T/F5/A5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | - |

| T/F5/A2 | 6 | 5 | 2 | - |

| T/F5/A5/S | 6 | 5 | 5 | 15 |

| T/F5/A2/S | 6 | 5 | 2 | 15 |

| Coating Abbreviation | Bursting Strength | Tensile Strength MD | Tensile Strength CD | Elongation at Break MD | Elongation at Break CD | Folding Endurance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Med | Med | Med | Med | Med | Med | |||||||

| Uncoated | 262.44 | 262.00 | 8.66 | 8.65 | 5.07 | 5.05 | 2.55 | 2.50 | 6.94 | 7.10 | 819.90 | 759.00 |

| T | 292.78 | 293.00 | 8.82 | 8.80 | 5.52 | 5.50 | 3.13 | 3.10 | 7.91 | 8.00 | 860.40 | 872.00 |

| T/S | 300.56 | 302.00 | 9.08 | 9.10 | 5.65 | 5.65 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 7.79 | 8.00 | 912.80 | 931.00 |

| T/F5/A5 | 294.56 | 296.00 | 9.29 | 9.35 | 5.68 | 5.60 | 3.55 | 3.55 | 7.91 | 8.00 | 1068.60 | 1053.50 |

| T/F5/A2 | 292.67 | 293.00 | 8.95 | 8.90 | 5.69 | 5.70 | 3.22 | 3.20 | 7.68 | 7.80 | 805.50 | 793.50 |

| T/F5/A5/S | 294.00 | 294.00 | 9.10 | 9.10 | 5.68 | 5.70 | 3.58 | 3.60 | 8.27 | 8.30 | 766.30 | 747.50 |

| T/F5/A2/S | 288.44 | 285.00 | 9.17 | 9.20 | 5.58 | 5.55 | 3.55 | 3.60 | 7.83 | 7.90 | 928.50 | 894.50 |

| Mechanical Properties | N | H | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bursting strength | 63 | 28.75 | 6 | 0.0001 |

| Tensile strength MD | 70 | 31.98 | 6 | 0.0000 |

| Tensile strength CD | 70 | 31.80 | 6 | 0.0000 |

| Elongation at break MD | 70 | 47.90 | 6 | 0.0000 |

| Elongation at break CD | 70 | 31.44 | 6 | 0.0000 |

| Folding endurance | 70 | 30.24 | 6 | 0.0000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lukavski, T.; Bota, J.; Budimir, I.; Itrić Ivanda, K.; Kulčar, R.; Vukoje Bezjak, M. Functional Starch-Based Biopolymer Coatings for Sustainable Packaging Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 3303. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243303

Lukavski T, Bota J, Budimir I, Itrić Ivanda K, Kulčar R, Vukoje Bezjak M. Functional Starch-Based Biopolymer Coatings for Sustainable Packaging Applications. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3303. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243303

Chicago/Turabian StyleLukavski, Teodora, Josip Bota, Ivan Budimir, Katarina Itrić Ivanda, Rahela Kulčar, and Marina Vukoje Bezjak. 2025. "Functional Starch-Based Biopolymer Coatings for Sustainable Packaging Applications" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3303. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243303

APA StyleLukavski, T., Bota, J., Budimir, I., Itrić Ivanda, K., Kulčar, R., & Vukoje Bezjak, M. (2025). Functional Starch-Based Biopolymer Coatings for Sustainable Packaging Applications. Polymers, 17(24), 3303. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243303