Structural Correlation Coefficient for Polymer Structural Composites—Reinforcement with Hemp and Glass Fibre

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. GFRP Floating Units and Their Disposal in Terms of Environmental Risks

- (a)

- These crops are grown in Poland: industrial hemp and flax;

- (b)

- Agricultural costs and growth in the area under cultivation of these plants in Poland: industrial hemp: cheap, year-on-year growth in the area under cultivation and flax; expensive, stable area under cultivation at a certain level;

- (c)

- Impact on degraded soil: industrial hemp—positive impact on degraded soil in the process of regenerating its structure and fertility by increasing organic matter content, improving microbial activity and regulating pH, minimal use of artificial fertilisers and no need for full-scale irrigation and flax; requires significant use of artificial fertilisers and full-scale irrigation;

- (d)

- Global raw material price in 2022 (USD/1 tonne): industrial hemp fibres, 1000–1900 (average 1450), and flax fibres: 2100–4200 (average 3150);

- (e)

- Energy required to produce 1 tonne of fibre (GJ/1 tonne): industrial hemp fibre, 4.0, and flax fibre, 4.5;

- (f)

- Distinctive physical, chemical, and mechanical properties of plant fibres: industrial hemp and flax—comparable.

3. Research Work—Assumptions

- Examination of the validity and advisability of replacing commonly used GFRP structural composites with a new HF fibre-reinforced composite material in the construction of selected composite vessels, in light of the applicable regulations concerning the need to counteract degradation and protect the environment;

- Production of a new environmentally friendly material reinforced with natural plant fibres in the form of HF, intended for the construction of hulls for yachts, motorboats, and other selected composite vessels;

- Completion of a comparative analysis of selected physical and mechanical properties of HF-reinforced polymer structural composites with varying amounts of reinforcement material, demonstrating their full recyclability using energy recovery methods;

- Determination of the structural correlation coefficient WK for a new environmentally friendly construction material in relation to GFRP, subject to the condition of comparable weight of the hull plating of a composite vessel.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Selection of Materials for the Production of Composites for Testing

- DCPD polyester resin (known as improved polyester ‘yacht’ resin) with the trade name AropolTM M 604 TBR + Metox-50WR resin copolymerisation initiator + pro-adhesive agent in the form of maleic anhydride (MAH) in a ratio of 3 g per 100 g of resin;

- GF fabric—manufacturer: KROSGLASS/Krosno/Poland—weight 450 ± 27 g/m2;

- HF fabric—manufacturer: S.C. CAVVAS LIMITED S.R.L./Cluj-Napoca/Romania—weight 478 g/m2.

4.2. Production of Research Material

4.2.1. Technology for the Production of Composite Materials Intended for Research

4.2.2. Composite Manufacturing Technique

4.2.3. Production of Control Plates and Test Samples

4.3. Conducting Research

- Physical testing (density, water absorption, reaction to fire, and environmental testing (disposal by energy recycling));

- Mechanical testing:

- Tensile strength testing of materials in accordance with EN ISO 527-2 [29] (using a universal testing machine SHIMADZU (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) type AG-X plus (MWG − 20 kNA, CAP 20 kN, at the feed of 10 mm/min and at the temperature of 22 °C));

- Static bending strength testing of materials in accordance with EN ISO 178 [30] (using the universal testing machine as above, at the temperature of 22 °C);

- Charpy impact testing of materials in accordance with EN ISO 179-2 [31] on standard specimens without notches (using a pendulum hammer VEB Werkstoffpruefmaschinen Leipzig-Betrieb des VEB Fritz Heckert (Saxony, Germany) with a maximum impact energy of up to 50 J and up to 300 J).

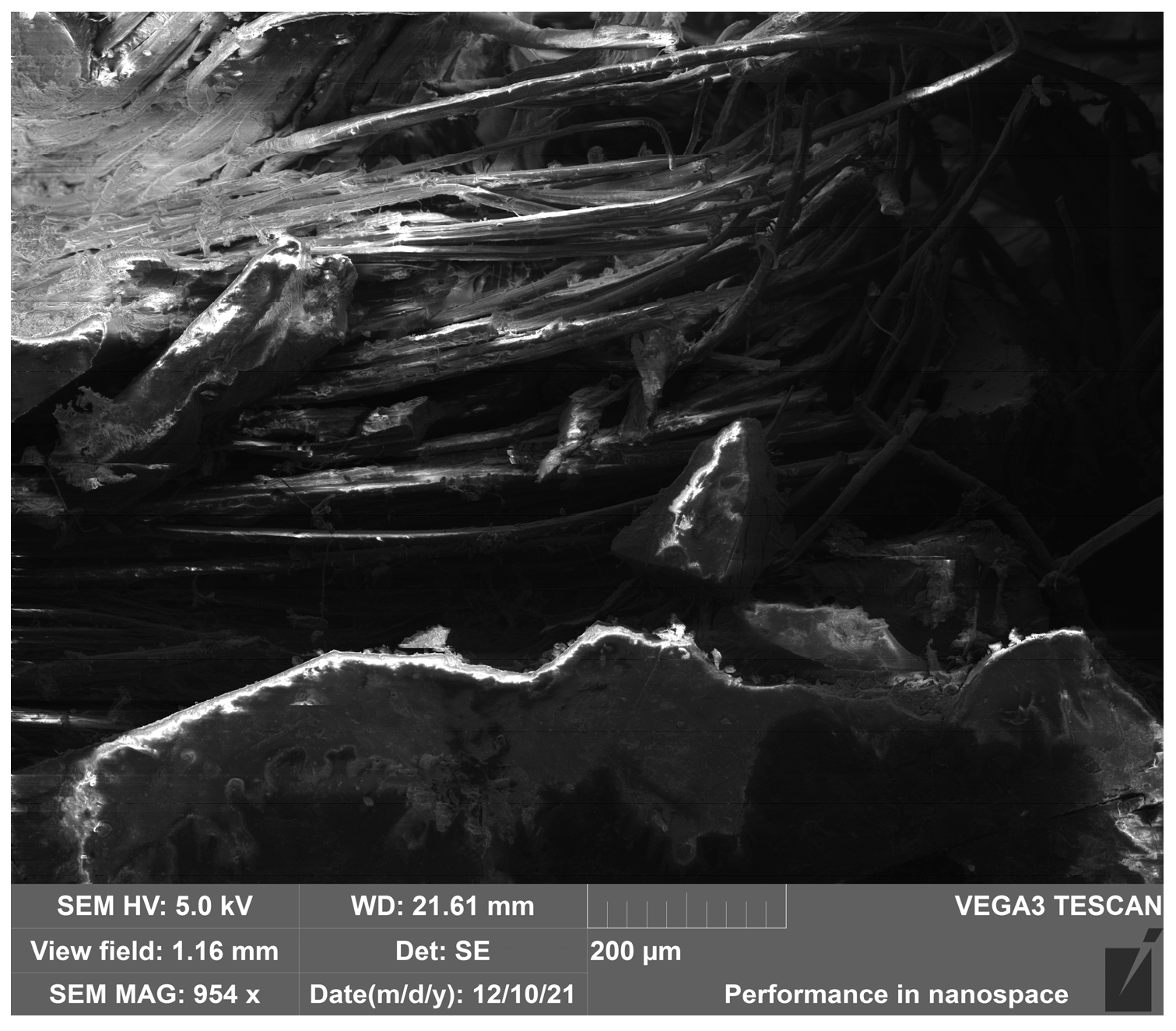

- Morphological properties of materials (using a scanning electron microscope—SEM VEGA3 TESCAN, TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic (beam voltage of 5 kV, scattered electrons detector)).

4.4. Analysis of Research Results

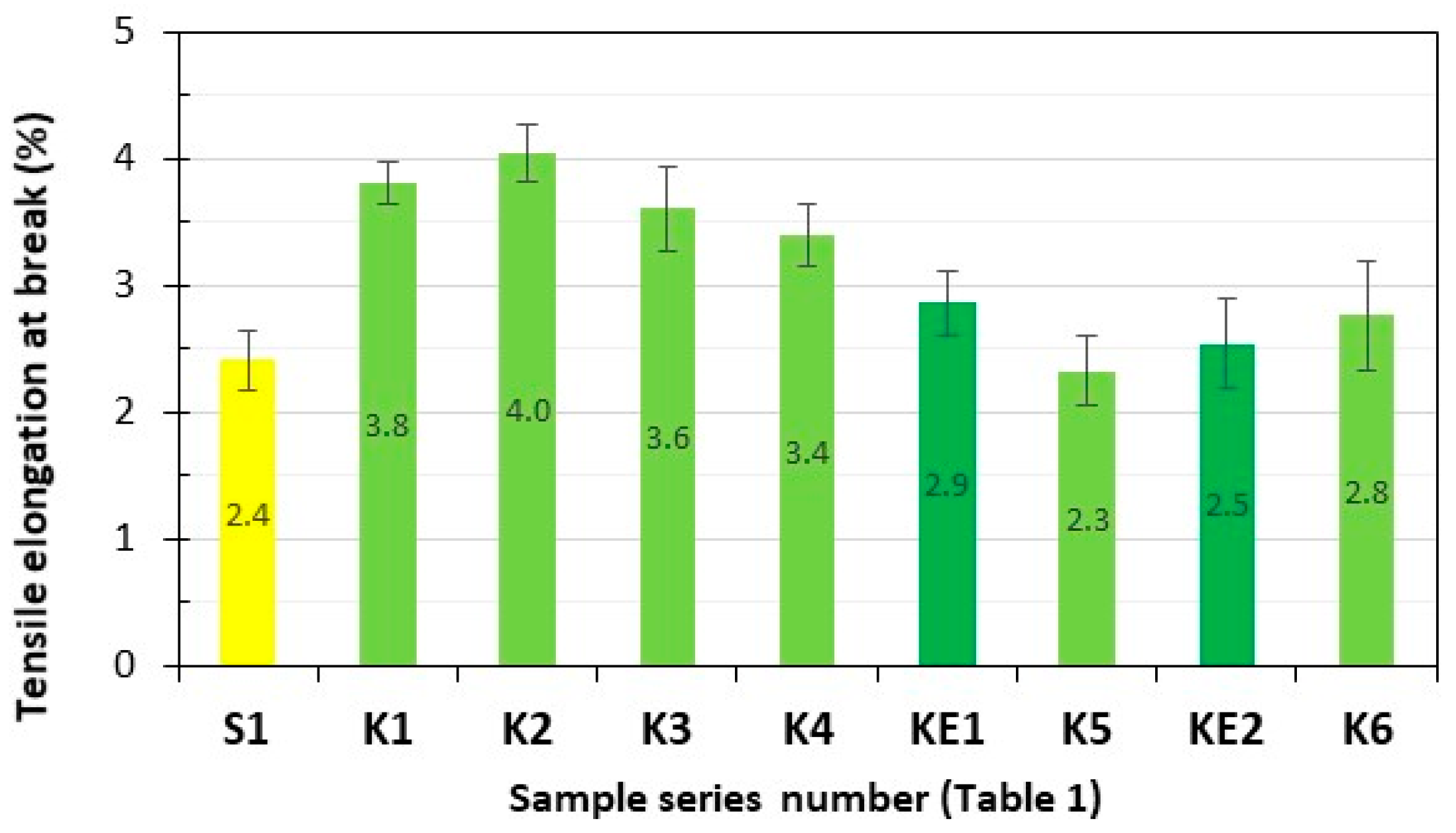

4.4.1. Analysis of Tensile Strength Test Results for Composite Samples

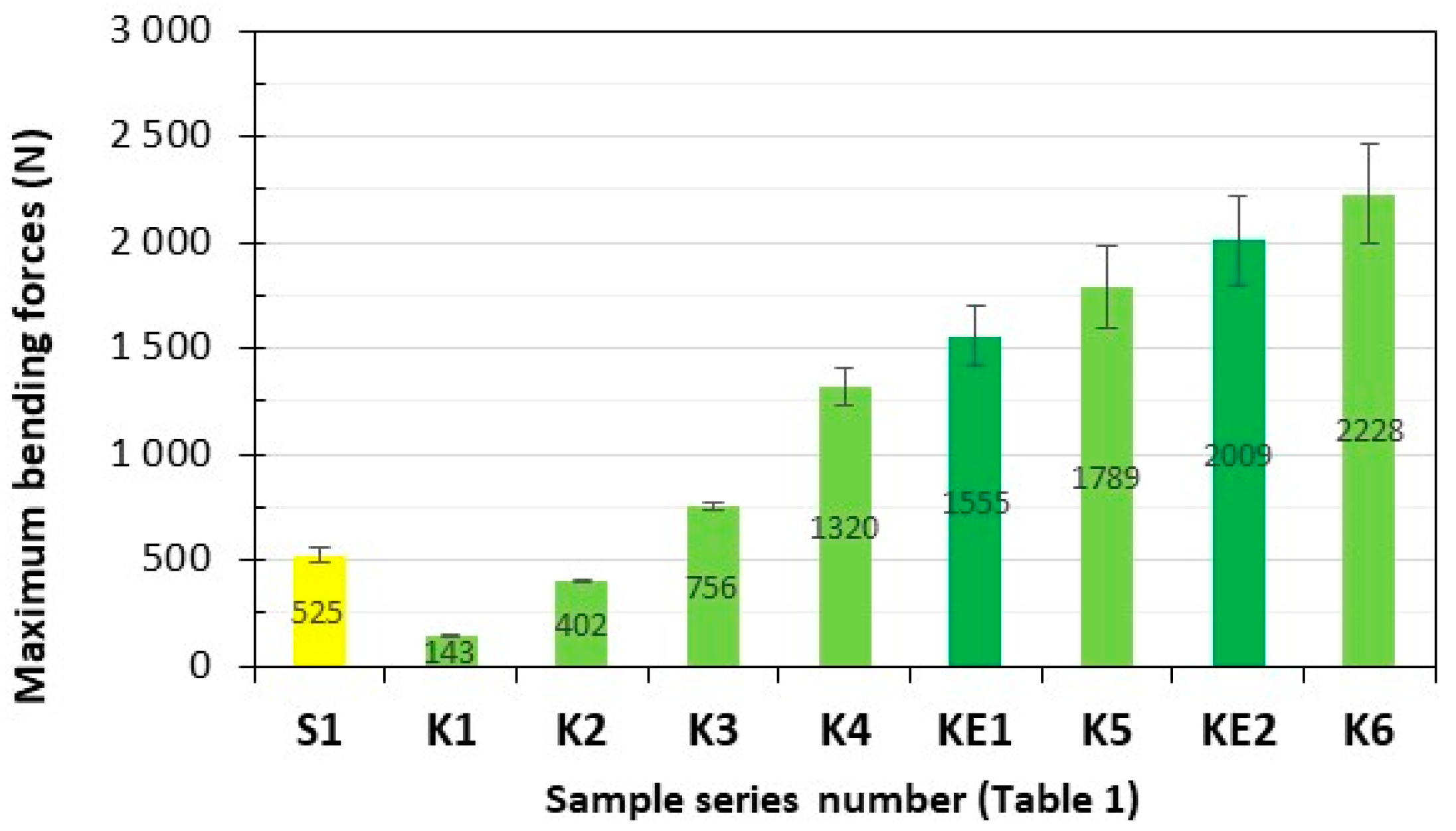

4.4.2. Analysis of the Results of Static Bending Strength Tests on Composite Samples

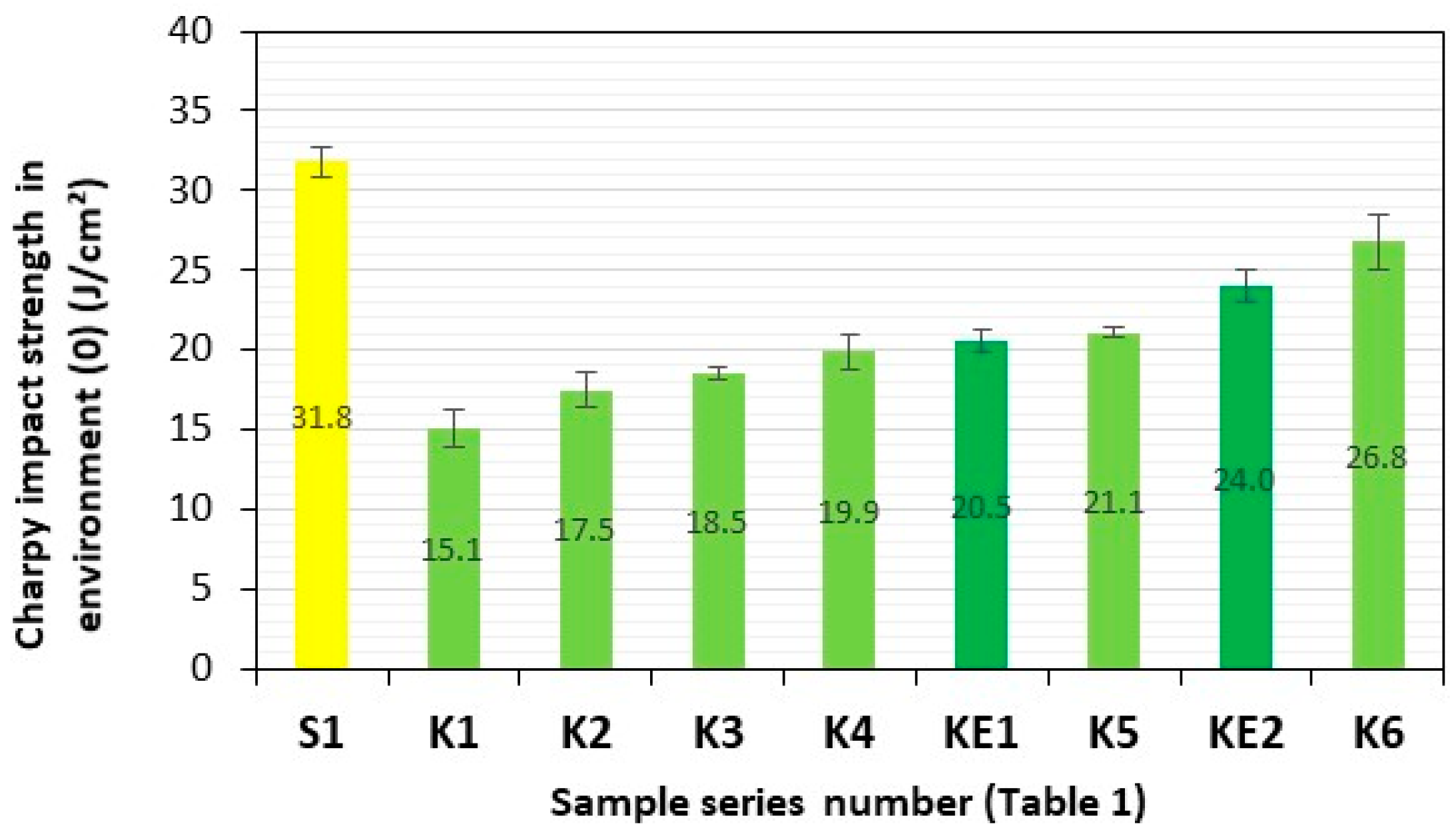

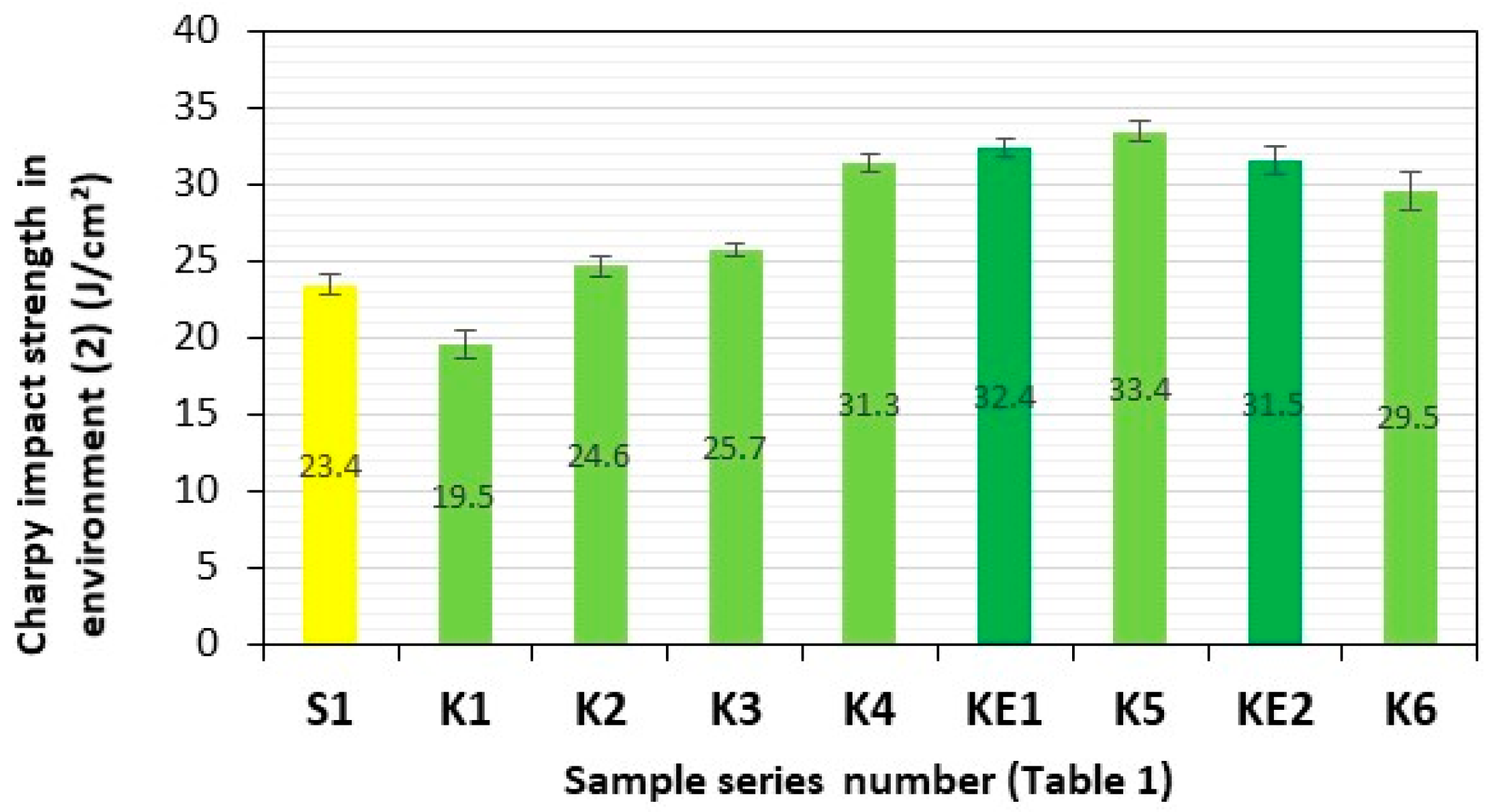

4.4.3. Analysis of Impact Test Results (Charpy Method) for Composite Samples

4.4.4. Analysis of the Suitability for Energy Recycling of a Selected Polymer Structural Composite

- The manufactured HFRP composite material subjected to energy recycling was almost completely utilised, i.e., at a level of 98%;

- The waste produced after incineration of HFRP material consisted of ash, amounting to 2% of its mass;

- The heat released during combustion of HFRP material was 183.0 MJ/m2, while that of GFRP material was 48.8 MJ/m2 (test method—ISO 5660-1), which means that in the case of HFRP composite it is 3.75 times greater than the heat released during the combustion of the GFRP composite;

- HFRP material can be used as energy fuel and the ash residue as an important component of effective natural fertiliser in line with EU preference for the CEco (Circular Economy).

4.5. Morphological Properties of HFRP Composites After Strength Tests

- −

- Presentation of the general characteristics of the material structure with regard to the analysis of the matrix/reinforcement interface on a micron scale;

- −

- Non-destructive visualisation of the internal features of the materials’ structure: porosity, fibre alignment, and matrix/reinforcement phase distributions;

- −

- Detailed insight into the internal structure of the materials in areas of damage/destruction caused in the samples as a result of the mechanical test.

4.6. Analysis of the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Tested Polymer Structural Composites

5. Structural Correlation Coefficient (WK) for Structural Polymer Composites HFRP vs. GFRP

| • | Density of polymer structural composite | K4 and K5 |

| • | Water absorption polymer structural composite | K4 and K5 |

| • | Reaction to fire and suitability for disposal by means of energy recovery | K5 |

| • | Tensile strength in the area of maximum tensile forces of composites | K5 and K6 |

| • | Tensile strength in the area of composite | K5 and K6 |

| • | Static bending strength in the area of maximum bending forces of composites | K5 and K4 |

| • | Static bending strength in the area of composite elongation | K5 and K4 |

| • | Impact strength (Charpy method) of composite in environment (0) (air) | K6 and K5 |

| • | Impact strength (Charpy method) of the composite in environment (1) (demineralised water) | K4 and K5 |

| • | Impact strength (Charpy method) of the composite in environment (2) (fresh water (Lake Miedwie)) | K5 and K4 |

| • | Impact strength (Charpy method) of the composite in environment (3) (brackish water (salinity 7.8‰—Baltic Sea)) | K5 and K4 |

| • | Impact strength (Charpy method) of the composite in environment (4) (salt water (salinity 38‰—Adriatic Sea)) | K5 and K4 |

6. Conclusions

- In the context of research work carried out on the development of a new HFRP composite material recommended for the shipbuilding industry, meeting the relevant strength, operational, and economic requirements, and, in particular, environmental requirements, its use in the shipbuilding industry is envisaged in the sector of manufacturing selected recreational vessels (yachts and motorboats) and other floating products (buoys/floats, pontoons). Dedicated to each selected composite structure, the reinforcement of this material, in accordance with its individually applied technology, should be made of fabrics and/or emulsion mats of industrial hemp with variable weight and multidirectional arrangements (0, 90, ±45°) of the fibres of this plant.

- Based on the flammability test of the HFRP composite reinforced with HFs, the possibility of quasi-complete utilisation of this material by means of energy recycling was verified and a fully positive result was obtained. When 100% of the composite mass was incinerated, 98% of thermal energy and 2% of ash were obtained, which is used as an important component of effective natural fertilisers (EU preferences regarding the circular economy (CEco)). It should be emphasised that in using the test method according to ISO 5660-1 [34], the combustion heat of HFRP (183 MJ/m2) is 3.75 times higher than that of GFRP (48.8 MJ/m2). For comparison, the combustion heat of HFRP (31 MJ/kg) in relation to GFRP (21 MJ/kg), lignite (5.9–23 MJ/kg), and wood (18 MJ/kg) is approx. 1.5 times higher, and compared to hard coal (16.7–29.3 MJ/kg) and charcoal (30 MJ/kg), it is comparable in favour of HFRP.

- A detailed analysis of the results of tests on the physical, mechanical, and morphological properties of new composite materials made it possible to determine the SCC WK for HFRP in relation to GFRP as WK = 1.66 (6), provided that the weight of the skin/shell of the selected floating object/structure is comparable.

- In light of the stringent regulations enforced concerning the need to combat degradation and protect the environment (restrictive EU legal regulations in force since 2018), and the significant reduction in the amount of non-biodegradable plastic waste (in particular, GF in the shipbuilding industry in the sector of manufacturing selected recreational vessels (yachts and motorboats)), as well as other floating products (buoys/floats, pontoons), it is considered appropriate and reasonable to replace the commonly used non-ecological GFRP composite reinforced with glass fibres with a new-generation HFRP composite material reinforced with industrial hemp fibres (Cannabis sativa L.).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scheibe, M.; Urbaniak, M.; Gorący, K.; Błędzki, K. Problems connected with utilization of polymer composite products and waste materials Part II. “Scrapping” of composite recreational vessels in the world in the perspective of 2030. Polimery 2019, 64, 788–794. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledzki, A.K.; Fink, H.-P.; Specht, K. Unidirectional Hemp and flax EP- and PP-compisites: Influence of defined fiber treatments. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 93, 2150–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouison, D.; Sain, M.; Couturier, M. Resin transfer molding of hemp fiber composites: Optimization of the process and mechanical properties of the materials. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2006, 66, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, A. Properties of Hemp Fibre Polymer Composites—An Optimisation of Fibre Properties Using Novel Defibration Methods and Fibre Characterisation. Ph.D. Thesis, The Royal Agricultural and Veterinary University of Denmark, Roskilde, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Faruk, O.; Bledzki, A.; Fink, H.-P.; Sain, M. Biocomposites reinforced with natural fibers: 2000–2010. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 1552–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuanjian, T.; Isaac, D.H. Impact and fatigue behaviour of hemp fibre composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 3300–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A. Hemp fiber and its composites: A review. J. Compos. Mater. 2012, 46, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyeenuddin, A.S.; Pickering, K.L.; Fernyhough, A. Flexural properties of hemp fibre reinforced polylactide and unsaturated polyester composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2012, 43, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawpan, M.A.; Pickering, K.L.; Fernyhough, A. Analysis of mechanical properties of hemp fibre reinforced unsaturated polyester composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2012, 47, 1513–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkar, V.C.; Kumar, V. A review study on the mechanical behaviour of natural fibre-reinforced epoxy composite. Polym. Bull. 2025, 82, 9647–9682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, K.L.; Aruan Rfendy, M.G.; Le, T.M. A review of recent developments in natural fibre composites and their mechanical performance. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 83, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejos, M.E.; Espinach, F.X.; Julián, F.; Torres, L.; Vilaseca, F.; Mutjé, P. Micromechanics of hemp strands in polypropylene composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2012, 72, 1209–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A. A study in physical and mechanical properties of hemp fibres. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 2013, 325085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrot, L.; Lefeuvre, A.; Pontoire, B.; Bourmaud, A.; Baley, C. Analysis of the hemp fiber mechanical properties and their scattering (Fedora 17). Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 51, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spychalski, G.; Mańkowski, J.; Kubacki, A.; Kołodziej, J.; Pniewska, I.; Baraniecki, P.; Grabowska, L. Industrial Hemp Cultivation and Processing Technology; Institute of Natural Fibres & Medicinal Plants IWNiRZ: Poznan, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Puech, L.; Ramakrishnan, K.R.; Moigne, N.L.; Corn, S.; Slangen, P.R.; Duc, A.L.; Bouldhani, H.; Bergeret, A. Investigating the impact behaviour of short hemp fibres reinforced polypropylene biocomposites through high speed imaging and finite element modelling. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 109, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, P.F.; Kallakas, H.; Poltimäe, T.; Kers, J. Effect of hemp fibre length on the properties of polypropylene composites. Agron. Res. 2019, 17, 1517–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.P.; de Mendonça Neuba, L.; da Silveira, P.H.; da Luz, F.S.; da Silva Figueiredo, A.B.; Monteiro, S.N.; Moreira, M.O. Mechanical, thermal and ballistic performance of epoxy composites reinforced with Cannabis sativa hemp fabric. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 12, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, P.F.; Marrot, L.; Kallakas, H.; Just, A.; Poltimäe, T.; Kers, J. Effect of hemp fiber surface treatment on the moisture/water resistance and reaction to fire of reinforced PLA composites. Materials 2021, 14, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Advancing and Representing a Sustainable Boating and Nautical Tourism Industry. Available online: https://www.europeanboatingindustry.eu (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- NASBLA. Available online: https://www.nasbla.org (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Market Research Report “Recreational Boat Market by Boat Type (Motorboats, Sailboats, Yachts, Inflatable Boats), by Power Source, by Activity/Application, by Material, by Power Range, by Ownership, by Sales Channel-Global Industry Outlook, Key Companies (Brunswick Corporation, Groupe Beneteau, Yamaha Motor Co. Ltd., and others), Trends and Forecast 2025–2034”, Report RC-1774, Published on August 2025. Available online: https://www.dimensionmarketresearch.com/report/recreational-boat-market/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Scheibe, M. Analysis of the Applicability of Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites for the Construction of Selected Types of Vessels. Ph.D. Thesis, Maritime University of Szczecin, Szczecin, Poland, 2022. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe, M.; Urbaniak, M.; Bledzki, A. Application of Natural (Plant) Fibers Particularly Hemp Fiber as Reinforcement in Hybrid Polymer Composites—Part I. Origin of Hemp and Its Coming into Prominence, Cultivation Statistics, and Legal Regulations. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 20, 2251682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibe, M.; Bryll, K.; Brożek, P.; Czarnecka-Komorowska, D.; Sosnowski, M.; Grabian, J.; Garbacz, T. Comparative Evaluation of the Selected Mechanical Properties of Polymer Composites Reinforced with Glass and Hemp Fabrics. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2023, 17, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheibe, M.; Urbaniak, M.; Bledzki, A. Application of Natural (Plant) Fibers Particularly Hemp Fiber as Reinforcement in Hybrid Polymer Composites—Part II. Volume of Hemp Cultivation, Its Application and Sales Marked. J. Nat. Fibers 2023, 20, 2276715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibe, M.; Urbaniak, M.; Kukulka, W.; Bledzki, A. Application of Natural (Plant) Fibers Particularly Hemp Fiber as Reinforcement in Hybrid Polymer Composites—Part III. Investigations of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Composites Reinforced with Hemp Fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2024, 21, 2414194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polish Register of Shipping. Rules for the Classification and Construction of Sea-Going Yachts. Part II—Hull; Polish Register of Shipping: Gdansk, Poland, 1998. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- EN ISO 527-2: 2012; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties. Part 2: Test Conditions for Moulding and Extrusion Plastics. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- EN ISO 178: 2019; Plastics—Determination of Flexural Properties. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- EN ISO 179-2: 2020; Plastics—Determination of Charpy Impact Properties. Part 2: Instrumented Impact Test. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- ISO 15314:2018; Plastics—Methods for Marine Exposure. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Scheibe, M.; Dobrzynska, R.; Urbaniak, M.; Bledzki, A. Polymer Structural Composites Reinforced with Hemp Fibres—Impact Tests of Composites After Long-Term Storage in Representative Aqueous Environments and Fire Tests in the Context of Their Disposal by Energy Recycling Methods. Polymers 2025, 17, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 5660-1:2015; Reaction-to-Fire Tests—Heat Release, Smoke Production and Mass Loss Rate. Part 1: Heat Release Rate (Cone Calorimeter Method) and Smoke Production Rate (Dynamic Measurement). International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

| Number of Tested Reinforcement Layers K1–K6 and Additionally Determined Empirically KE1, KE2 Included in the Analysis Concerning the Determination of the Structural Correlation Coefficient WK | Designation of a Series of Samples |

|---|---|

| GF—E-glass—6 layers | S1 |

| HF—industrial hemp—3 layers | K1 |

| HF—industrial hemp—5 layers | K2 |

| HF—industrial hemp—7 layers | K3 |

| HF—industrial hemp—9 layers | K4 |

| HF—industrial hemp—10 layers | KE1 |

| HF—industrial hemp—11 layers | K5 |

| HF—industrial hemp—12 layers | KE2 |

| HF—industrial hemp—13 layers | K6 |

| Designation of a Series of Samples/Aqueous Environments | Charpy Impact Strength, J/cm2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air (0) | Demineralised Water (1) | Fresh Water (Lake Miedwie) (2) | Brackish Water—Salinity 7.8‰ (Baltic Sea) (3) | Salty Water—Salinity 38‰ (Adriatic Sea) (4) | |

| S1 | 31.8 ± 0.9 | 22.7 ± 0.8 | 23.4 ± 0.6 | 23.8 ± 0.6 | 24.3 ± 0.6 |

| K1 | 15.1 ± 1.2 | 16.1 ± 0.2 | 19.5 ± 1.0 | 15.2 ± 0.8 | 14.7 ± 0.6 |

| K2 | 17.5 ± 1.1 | 22.0 ± 0.8 | 24.6 ± 0.7 | 18.6 ± 0.3 | 15.7 ± 0.9 |

| K3 | 18.5 ± 0.4 | 23.7 ± 0.6 | 25.7 ± 0.4 | 22.6 ± 0.3 | 17.5 ± 0.4 |

| K4 | 19.9 ± 1.1 | 30.9 ± 0.7 | 31.3 ± 0.6 | 31.6 ± 0.7 | 28.1 ± 0.2 |

| KE1 | 20.5 ± 0.7 | 30.1 ± 0.7 | 32.4 ± 0.6 | 33.5 ± 0.6 | 29.3 ± 0.3 |

| K5 | 21.1 ± 0.3 | 29.2 ± 0.6 | 33.4 ± 0.6 | 35.4 ± 0.5 | 30.5 ± 0.4 |

| KE2 | 24.0 ± 1.0 | 29.1 ± 0.8 | 31.5 ± 0.9 | 35.1 ± 0.5 | 29.4 ± 0.5 |

| K6 | 26.8 ± 1.7 | 29.0 ± 0.9 | 29.5 ± 1.2 | 34.7 ± 0.5 | 28.2 ± 0.5 |

| Test Type | Polymer Structural Composite | GFRP | HFRP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Density, g/cm3 | 1.6 | 1.2–1.3 |

| Water absorption, % | 0.1 | 3.0–4.3 | |

| Environmental | Residue after burning, % | 57.2 (GF—solid waste) | 2.0 (HF—Ash) |

| Mechanical | Tensile elongation, % | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.2–4.4 ± 0.2 |

| Elongation under static bending, % | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.3–7.4 ± 0.2 | |

| Maximum tensile forces, N | 9541 ± 224 | 9209 ± 528 | |

| Maximum static bending forces, N | 525 ± 37 | 2228 ± 233 | |

| Impact tests were performed after storing the test samples for one month in dry trays with overall air access (0) and also after storing them for a further three months in representative aquatic environments (1)–(4) | Charpy impact strength in environment (0) (air), J/cm2 | 31.8 ± 0.9 | 15.1 ± 1.1–26.8 ± 1.7 |

| Charpy impact strength in environment (1) (demineralised water), J/cm2 | 22.7 ± 0.8 | 16.1 ± 0.2–30.9 ± 0.7 | |

| Charpy impact strength in environment (2) (fresh water—Lake Miedwie), J/cm2 | 23.4 ± 0.6 | 19.5 ± 1.0–33.4 ± 0.6 | |

| Charpy impact strength in environment (3) (brackish water—salinity 7.8‰—Baltic Sea), J/cm2 | 23.8 ± 0.6 | 15.2 ± 0.8–35.4 ± 0.5 | |

| Charpy impact strength in environment (4) (saline water—salinity 38‰—Adriatic Sea), J/cm2 | 24.3 ± 0.6 | 14.7 ± 0.6–30.5 ± 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scheibe, M.; Urbaniak, M.; Bledzki, A. Structural Correlation Coefficient for Polymer Structural Composites—Reinforcement with Hemp and Glass Fibre. Polymers 2025, 17, 3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243295

Scheibe M, Urbaniak M, Bledzki A. Structural Correlation Coefficient for Polymer Structural Composites—Reinforcement with Hemp and Glass Fibre. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243295

Chicago/Turabian StyleScheibe, Mieczyslaw, Magdalena Urbaniak, and Andrzej Bledzki. 2025. "Structural Correlation Coefficient for Polymer Structural Composites—Reinforcement with Hemp and Glass Fibre" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243295

APA StyleScheibe, M., Urbaniak, M., & Bledzki, A. (2025). Structural Correlation Coefficient for Polymer Structural Composites—Reinforcement with Hemp and Glass Fibre. Polymers, 17(24), 3295. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243295