1. Introduction

Copper and silver are essential industrial metals that play a critical role in modern technologies, including electrical engineering, microelectronics, catalysis, energy systems, antimicrobial coatings, and chemical manufacturing. Their unique physicochemical properties—high electrical and thermal conductivity, catalytic activity, and biological reactivity—determine the growing global demand for efficient extraction, recovery, and purification processes. As the consumption of these metals increases steadily, the need for sustainable management of mineral, technological, and secondary resources becomes ever more urgent [

1,

2,

3].

Kazakhstan is among the world’s leading countries in terms of copper reserves and possesses a diverse and extensive raw material base. The Zhezkazgan basin, which has large porphyry-type deposits such as Aktogay and Koksay, and the Bozshakol open-pit mine represent the major operational and prospective ore regions. Their cumulative resources demonstrate significant copper reserves accompanied by valuable by-products such as gold, silver, molybdenum, and rare metals. Silver in Kazakhstan typically does not occur as an independent ore mineral; instead, it is associated with sulfide and polymetallic ores, including chalcopyrite, galena, arsenide phases, and sulfosalts. In some sectors of the Zhezkazgan ore field, locally elevated silver contents reaching tens of grams per ton are recorded, which increases the importance of comprehensive extraction schemes [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Despite the abundance of deposits, the mining industry faces a gradual decrease in the quality of primary mineral raw materials. Average copper contents often do not exceed 0.3–0.4%, and richer zones exceeding 1% Cu in sedimentary-associated deposits are becoming increasingly rare. A similar trend characterizes the silver industry: although global silver production continues to grow by 1.5–2 thousand tons annually, existing reserves are finite. Forecasts based on current consumption rates suggest that economically viable silver resources may be depleted within the next two decades. Thus, the depletion of high-grade deposits, increasing depth of ore bodies, and the need to process complex mineralogical types raise the cost and difficulty of traditional metallurgy [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

At the same time, the processing of low-grade polymetallic ores intensifies environmental pressure. In Kazakhstan, where over half of metal-containing raw materials are extracted by open-pit mining, hydrometallurgical processes contribute to soil degradation, vegetation loss, contamination of natural waters with heavy metals and processing reagents, and the migration of toxic components in the biosphere. These factors underscore the necessity of developing environmentally safe, resource-efficient, integrated technologies aimed at the sustainable extraction and recycling of valuable metals [

17,

18,

19].

Against this background, secondary raw materials—including technological process solutions, tailings, and industrial wastewater—are becoming a strategically important source of copper, silver, and other critical metals. The recovery of Cu(II), Ag(I), and rare-earth ions from aqueous streams is in full alignment with global trends toward circular economy, reduction in primary resource dependence, and minimization of environmental impact. Industrial solutions generated by mining, metallurgical, and electronic-waste processing plants often contain significant quantities of recoverable metals, making them attractive objects for selective purification and extraction [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Among the numerous physicochemical methods proposed for the removal and recovery of metal ions from aqueous media, sorption is one of the most effective and technologically flexible approaches. Modern sorption systems include activated carbons, inorganic oxides, hybrid composites, and a broad range of functionalized polymeric materials. Polymer sorbents, in particular, have gained substantial attention due to their high structural tunability, chemical and mechanical resilience, reusability, and ability to incorporate targeted functional groups with high affinity for specific metal ions. Nitrogen-containing ligands such as primary, secondary, and tertiary amines significantly enhance chelation efficiency toward Ag(I) and Cu(II), making such polymers especially suitable for selective metal recovery [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

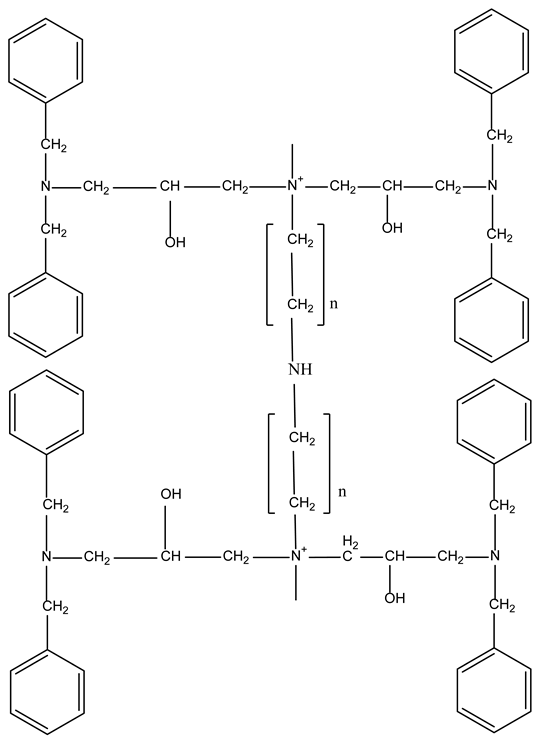

A promising strategy for designing advanced ion-exchange materials is the synergistic combination of dibenzylamine (DBA), epichlorohydrin (EChH), and polyethyleneimine (PEI). Polyethyleneimine provides a high density of amino groups responsible for metal coordination; epichlorohydrin serves as a crosslinking agent, imparting chemical stability, rigidity, and resistance to hydrolysis; while DBA introduces steric and hydrophobic elements that can positively influence metal binding kinetics and selectivity. These structural features create conditions for engineering multifunctional hybrid polymer matrices with enhanced sorption capacity, improved kinetic behavior, and increased resistance to aggressive environments. Such materials have potential applications not only in the extraction of non-ferrous and noble metals but also in catalysis, chromatographic separation, environmental remediation, and sensor technologies.

Considering these factors, the present study addresses the urgent need for efficient sorbents capable of recovering copper(II) and silver(I) ions from aqueous systems of varying concentrations. A new ion-exchange polymer based on DBA–EChH–PEI was synthesized and systematically investigated. Its sorption kinetics and extraction efficiency toward Cu2+ and Ag+ ions were examined under controlled laboratory conditions and directly compared with the performance of the commercial ionite Dowex HCR-S/S″. Particular attention was paid to the influence of contact time and initial ion concentration, enabling a comprehensive assessment of kinetic parameters and diffusion characteristics.

The scientific novelty of the work lies in the synthesis of a previously unreported DBA–EChH–PEI polymer ion-exchange material and its comparative evaluation with an industrial analog. The determination of concentration-dependent kinetic constants and extraction efficiency provides a foundation for quantitatively predicting sorption behavior and optimizing operational conditions for real technological and wastewater treatment processes. This research thus contributes to the development of effective polymer sorbents for sustainable metal recovery and supports broader efforts toward environmentally responsible resource management.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 1 shows some of the studied physico-chemical characteristics of the synthesized anionite. The synthesized DBA-EChH-PEI ionite demonstrated a 7–10% higher sorption capacity and ~12% better chemical stability to acids and alkalis compared to Dowex HCR-S/S″, which makes it more promising for multiple sorption–regeneration cycles.

The difference in acid and alkali resistance is critically important for practical applications. This means that DBA–EChH–PEI will lose its capacity more slowly with multiple sorption-regeneration cycles, especially when using aggressive reagents. The higher capacity and thermal stability further strengthen its position. Due to its characteristics, DBA–EChH–PEI is particularly suitable for processes requiring multiple regeneration, operation under extreme pH conditions or at elevated temperatures. Its use can lead to lower operating costs and longer service life of the ion exchange column. Thus, DBA–EChH–PEI not only has slightly better performance, but also offers a qualitatively higher level of stability, which is a key factor for industrial applications.

For the practical application of ionites, it is necessary to study the sorption of metal ions depending on the process conditions. In order to determine the optimal sorption parameters, the effect of the concentration (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) and the duration of their contact (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12) with ionites (Ionite 1—Dowex HCR-S/S″, Ionite 2—DBA-EChH-PEI) on the extraction of silver (I) and copper (II) ions was studied.

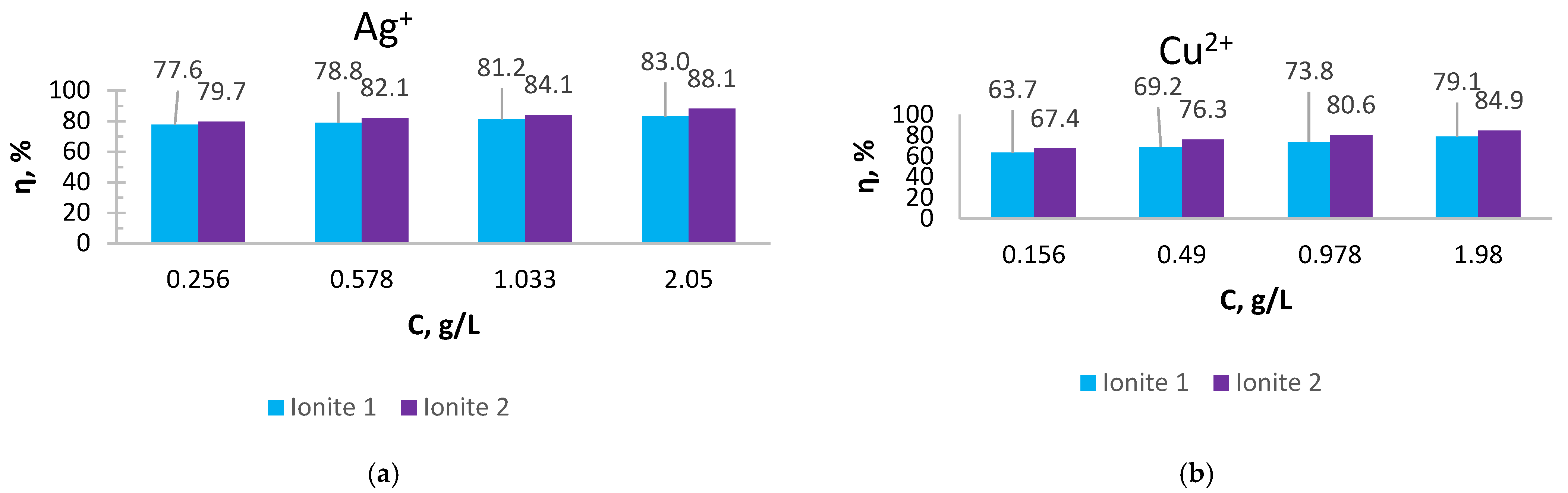

As can be seen from

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, the SC of ionites increases with an increase in the content of silver and copper ions in solutions.

Ionite 2 has a higher sorption capacity in the extraction of Ag+ and Cu2+ ions compared to Ionite 1, the SC for silver ions is 679.7 and 721.0 mg/g and for copper ions 626.3 and 672.4 mg/g. The degree of extraction of silver ions reaches 83 and 88.1%, for copper ions—79.1 and 84.9%, respectively.

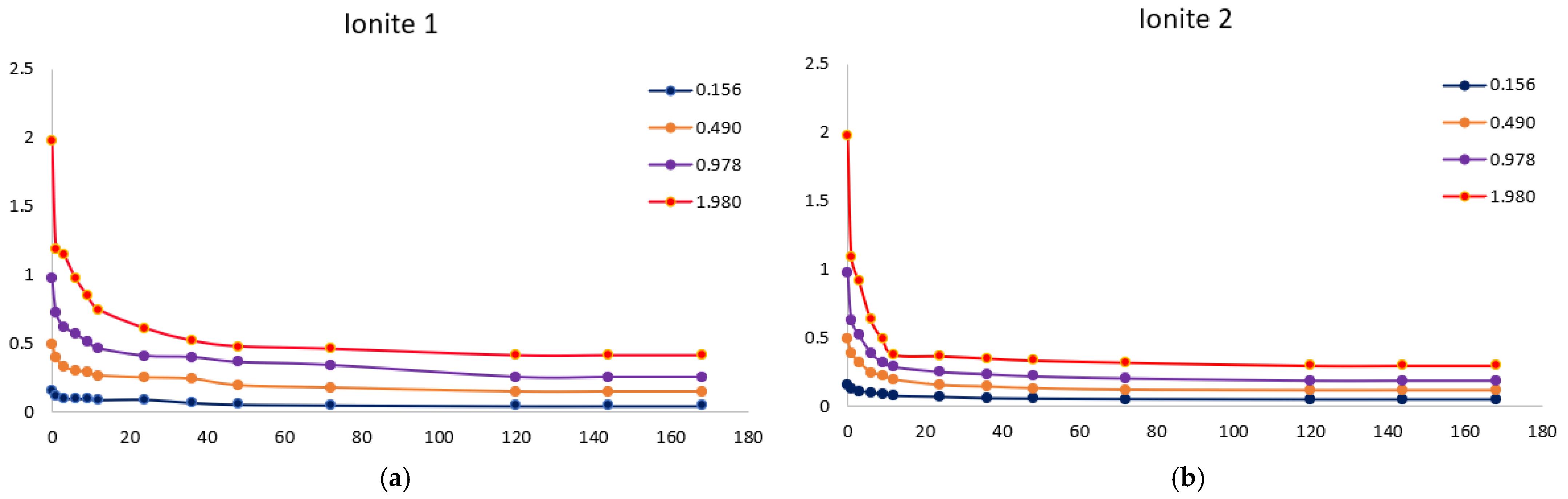

Figure 3 shows the isotherms of sorption of silver ions by Ionites 1 and 2. The equilibrium state between the ionites and the solution occurs after 120 h (5 days). The sorption process is characterized by the redistribution of metal ions from the bulk phase of the solution into the polymer matrix, which is reflected in the direct relationship between the concentration in the sorbent (capacity) and the inverse relationship with the equilibrium concentration in the solution.

Experiments show that the maximum sorption capacity of Ionite 1 shows a significant increase—from 79.3 mg/g to 679.7 mg/g—with an increase in the concentration of silver nitrate solution from 0.256 g/L to 2.050 g/L.

A clear positive correlation is observed for Ionite 2, where its maximum SC increases substantially with the AgNO3 concentration, reaching 721.0 mg/g at 2.050 g/L compared to 81.3 mg/g at the lowest concentration tested 0.256 g/L.

Figure 4 shows the isotherms of sorption of copper ions by Ionites 1 and 2. The equilibrium state between the ionites and the solution occurs after 120 h (5 days).

It was experimentally established that the maximum sorption capacity of Ionite 1 with respect to copper ions increased from 60.4 mg/g to 626.3 mg/g with an increase in the concentration of copper nitrate solution from 0.156 to 1.980 g/L.

A significant increase in the maximum sorption capacity of Ionite 2 was observed, from 63.9 mg/g to 672.4 mg/g, over the investigated range of copper nitrate concentrations (0.156–1.980 g/L).

As can be seen from

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, the sorption capacity of industrial ionite for silver ions is lower by 6% compared to synthesized, and for copper ions by 7%, which indicates a higher efficiency of synthesized ionite in the sorption of these ions and confirms the expediency of its use in purification systems where increased selectivity and capacity are required relative to silver and copper ions. The residual concentration curves demonstrate typical kinetic behavior for ion-exchange systems: a rapid initial sorption stage followed by a slower diffusion-limited phase, ultimately reaching equilibrium. The progressive decrease in concentration with time confirms the effective uptake of metal ions and the suitability of the sorbent for removing Cu

2+ and Ag

+ ions across a wide range of initial concentrations.

The extraction efficiency was determined for four initial metal-ion concentrations, covering dilute, medium, and elevated concentration ranges in order to simulate both wastewater-relevant and technologically relevant conditions. The synthesized DBA–EChH–PEI ionite and the commercial ion-exchange resin were examined under identical experimental settings to ensure comparability. The values presented in the table summarize the extraction degree (%) of each ionite at selected time points (1, 3, 6, 12, 15, 24, 48, 72, and 120 h). These data make it possible to visualize the differences in kinetic behavior between the two materials and to quantify the sorbent efficiency at each stage of the process. The full extraction data for both sorbents are presented in

Table 2.

The time-resolved extraction profiles show that the synthesized DBA–EChH–PEI ionite exhibits superior kinetic behavior from the very beginning of the sorption process. Within the first 1–3 h, it extracts 4–8% more Ag+ and 6–10% more Cu2+ compared with the industrial ionite. After 6–12 h, the difference becomes more pronounced, and after 15 h the synthesized ionite reaches up to 60–72% extraction depending on concentration, whereas the industrial material remains 10–15% lower. At longer intervals (24–72 h), Ionite 2 maintains its advantage, demonstrating slower saturation of active sites and more stable extraction rates. At 120 h the synthesized ionite achieves 79–88% extraction for Ag+ and 67–85% for Cu2+ across the studied concentration range, consistently outperforming the commercial ionite. These results confirm the enhanced kinetics and higher overall efficiency of the DBA–EChH–PEI ionite.

The analytical uncertainty of the concentration determination method (3–5%) contributes to the dispersion observed in the isotherm data. For the pair of ionites where the difference in sorption capacity is approximately 7–8%, this methodological error renders the distinction marginal. Within the accuracy of the applied experimental procedure, the sorption properties of the two ionites can therefore be considered statistically indistinguishable.

Sorption of heavy metal ions by synthesized anionites can be explained by the formation of coordination bonds by the donor-acceptor mechanism between the electron-donor groups of the ionite (-NH2, =NH, ≡N) and the vacant orbital of the transition metal ion [

33]:

The process of industrial ionite extraction proceeds according to the following scheme, where metal ions are exchanged on the cationite in the H

+ form:

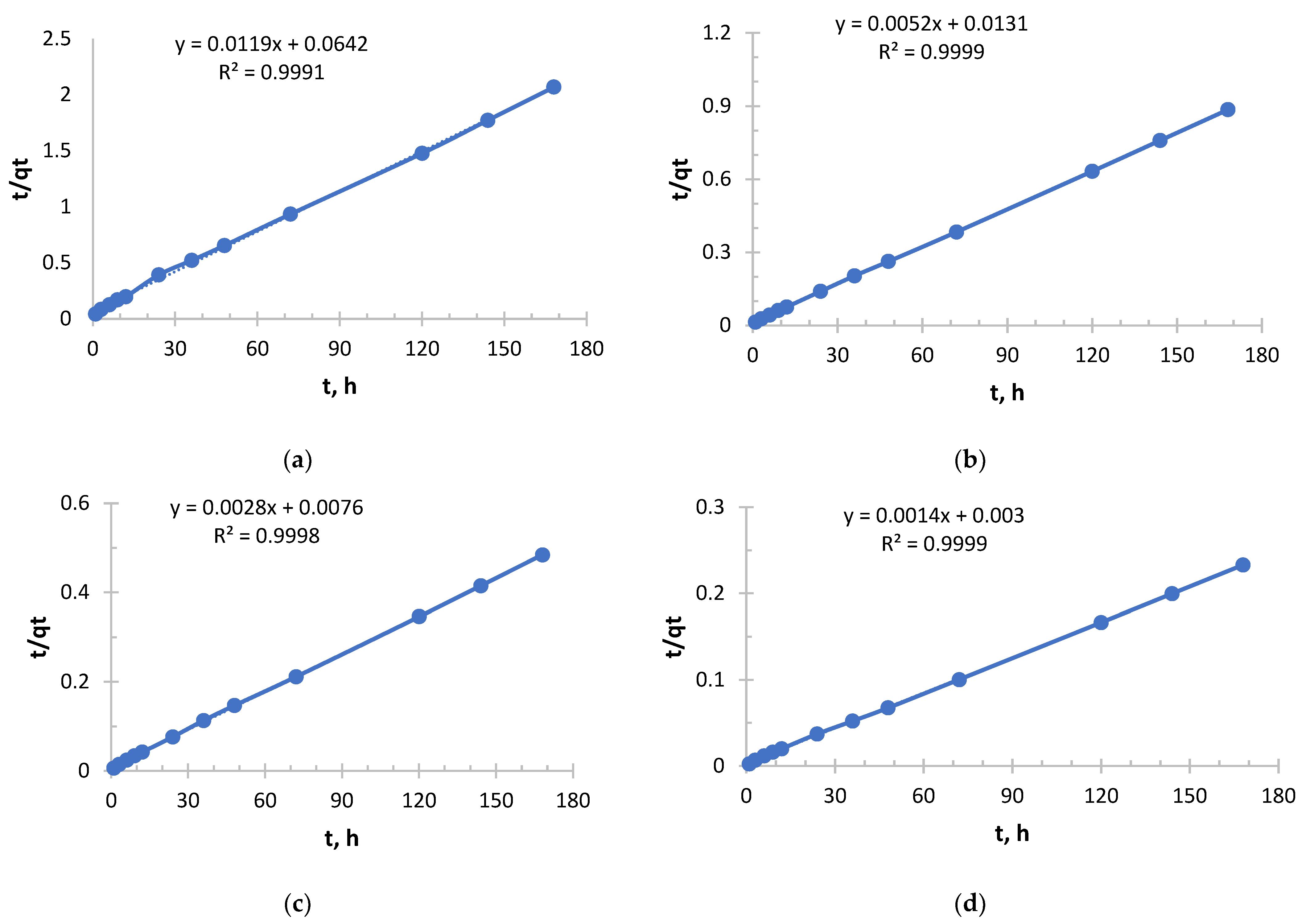

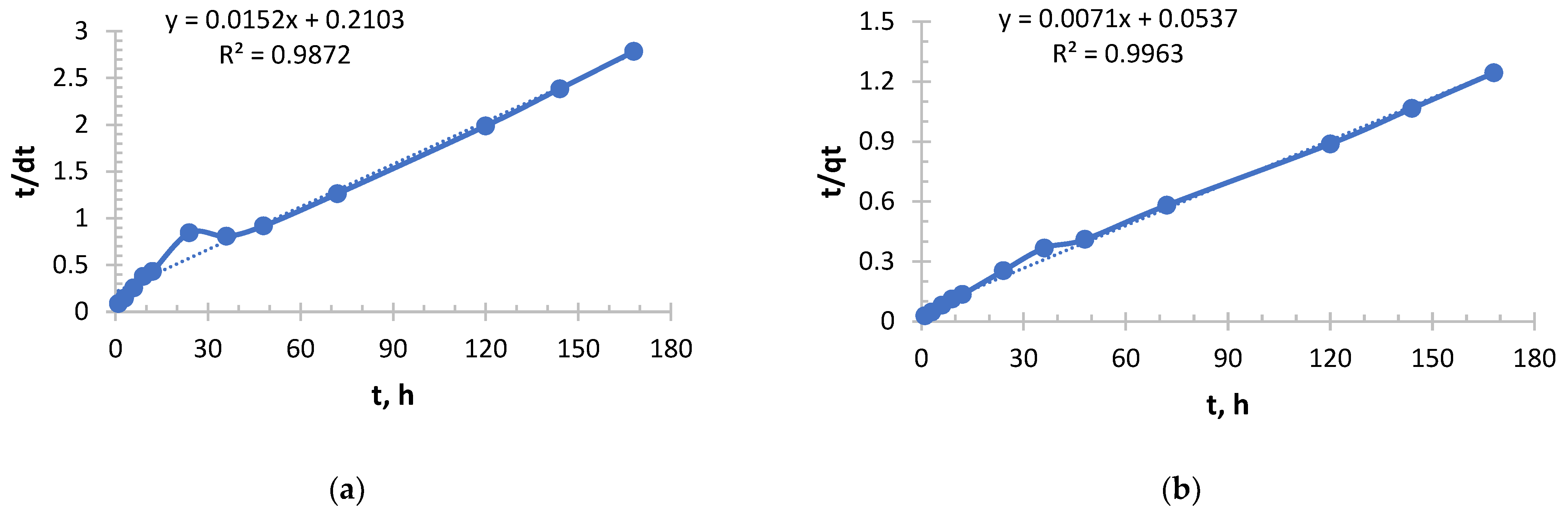

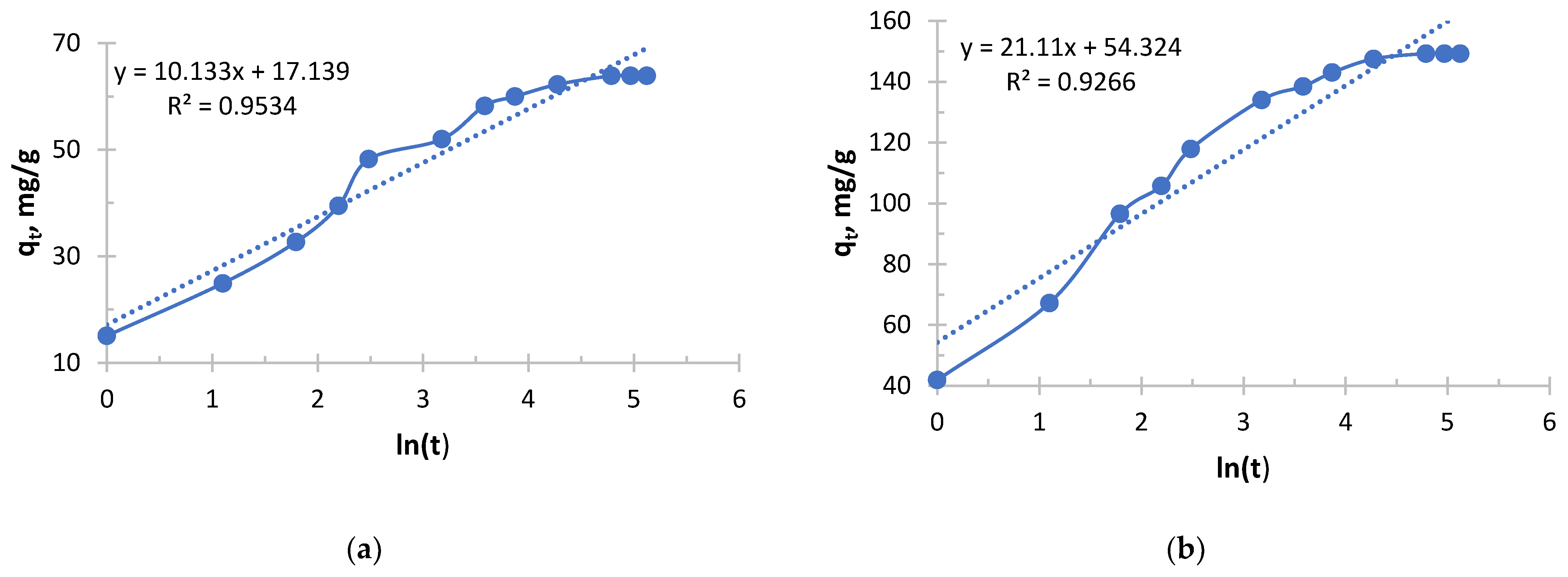

In order to evaluate the sorbents (Ionite 1 and Ionite 2) Pseudo-Second order (PSO) kinetic model and Elovich kinetic model were used.

Pseudo-second order and Elovich models were used to analyze the sorption kinetics [

17]. The pseudo-second-order model was used to estimate the maximum sorption capacity and the rate constant of the process, as well as to test the hypothesis of a limiting stage associated with chemical interaction. The Elovich model was used to analyze the kinetics throughout sorption in order to confirm the significant contribution of chemosorption and to evaluate the parameters characterizing the initial rate of the process and the activation energy.

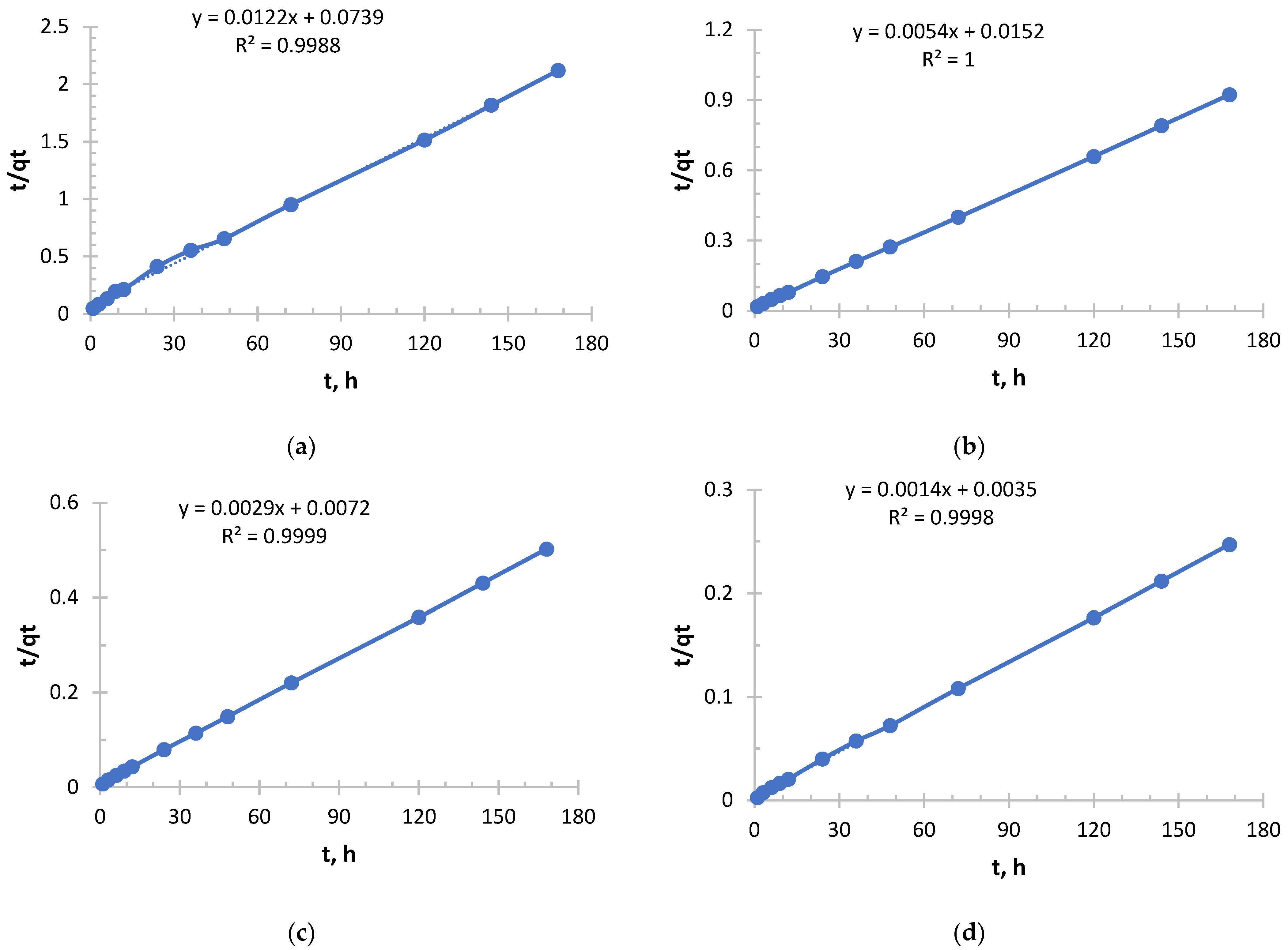

From

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 and

Table 3 and

Table 4, it follows that with increasing concentration, a rapid increase in the initial sorption rate is observed. With an increase in concentration from 0.256 to 2.050 g/L, the rate increased by 20 times, which is a direct consequence of an increase in the driving force of the process—the concentration gradient. The higher the concentration, the more Ag

+ ions “attack” the active centers of the sorbent per unit time.

The value of the rate constant steadily decreases with increasing initial concentration due to the fact that at low concentrations, ions primarily occupy the most accessible and energetically advantageous active centers. In concentrated solutions, these “best” centers fill up very quickly, and further sorption occurs at less accessible centers (requiring, for example, diffusion deep into the pores), which is a slower process and reduces the average rate constant.

Depending on the concentration, sorption took place in different ways, demonstrating a strong dependence on concentration. In a solution with a lower concentration (0.256 g/L), the process was slowest, but with maximum “specific” efficiency. This is a regime that is close to ideal for the active centers of the sorbent. In a solution with a higher concentration (2.050 g/L), sorption started extremely intensively, but its overall efficiency was the lowest. This is the “saturation” mode, when the kinetics begins to be limited not only by chemical interaction, but also by the availability of active centers.

For both sorbents, the choice of optimal conditions depends on the purpose:

- -

To quickly extract large amounts of silver, it is more profitable to use more concentrated solutions, since the initial velocity is at its maximum here.

- -

In order to achieve maximum sorbent efficiency and, possibly, more complete extraction from dilute solutions, conditions with a lower concentration, where the rate constant k2 is higher, may be preferable.

The sorption of silver ions by both ion exchange resins was carried out in full accordance with theoretical expectations. An increase in concentration accelerates the process at the start, but reduces the overall efficiency of the sorption mechanism, described by the constant k2.

As can be seen from

Figure 7 and

Table 5, it follows that an exponential increase in the initial sorption rate is observed with increasing concentration. With an increase in concentration from 0.156 to 1.980 g/L, the rate increased by more than 40 times. This is a consequence of an increase in the driving force of the process, the concentration gradient: the higher the concentration of copper ions (Cu

2+), the more they diffuse to the surface of the sorbent and interact with active centers per unit time.

The value of the velocity constant decreases with increasing initial concentration, which is consistent with the general theory. However, it is important to note here that the most significant drop in k2 occurs between solutions with concentrations of 0.490 and 0.978 g/L, while the rate constant decreases slightly between solutions with concentrations of 0.978 and 1.980. This may indicate that at concentrations above 1.0 g/L, the mechanism or the limiting stage of the process stabilizes.

The sorption of copper, like silver with Ionite 1, follows general patterns: with increasing concentration, the initial velocity increases; the rate constant k2 decreases monotonously.

For all the corresponding concentrations, the initial sorption rate of silver ions is significantly higher than that of copper ions. For example, for a concentration of about 2.0 g/L: V0(Ag) = 333.33 mg/g·h, and v0(Cu) = 204.08 mg/g·h. This suggests that the sorbent used has a higher affinity for silver ions or that the kinetics of their interaction is faster.

The k2 values for copper are about 2–3 times lower than for silver at the same concentrations. This confirms the conclusion that the silver sorption process on this sorbent proceeds more efficiently.

The successful description of the kinetics by the pseudo-second-order model indicates that the limiting stage is chemisorption, probably involving ion exchange or the formation of coordination bonds between copper ions and sorbent functional groups.

Copper sorption was predictable, demonstrating a strong dependence on concentration. Compared with silver, copper sorption on this sorbent is characterized by a lower rate and overall efficiency. This is an important practical conclusion that must be taken into account when designing cleaning processes for solutions containing metal mixtures.

From

Figure 8 and

Table 6, it can be seen that an extremely sharp increase in the initial sorption rate is observed with increasing concentration. With an increase in concentration from 0.156 to 1.980 g/L, the rate increased 40-fold. This indicates a very strong dependence of the rate of the process on the concentration, that is, a high “order” of reaction for the substance in solution. The driving force of the process (concentration difference) is a key factor.

The value of the rate constant decreases with increasing initial concentration, which is expected. However, it is important to note the slowing decline of k2. The greatest jump in efficiency reduction occurs when switching from the lowest concentration (0.156 g/L) to a higher one (0.490 g/L). With a further increase in concentration, the drop in k2 becomes less pronounced. This may mean that at concentrations above 0.5 g/L, the system enters a stable mode where the sorption mechanism does not change so dramatically.

In this experiment, copper sorption is characterized by very high rates, especially in concentrated solutions. The initial velocity in a solution with a concentration of 0.1980 mg/L (526.32 mg/g·h) is more than 2.5 times higher than in a similar solution from a previous experiment using Ionite 1 (204.08 mg/g·h). This suggests that the kinetics of copper sorption has improved significantly under these conditions.

The values of the velocity constant in this experiment using Ionite 2 are also significantly higher (2–3 times) than in the case of Ionite 1. This indicates that in this case, the sorption process was generally more efficient at all concentrations.

In a solution with a concentration of 0.156 g/L, the process proceeded with maximum “specific” efficiency (highest k2), but at a moderate speed.

In a solution with a concentration of 1.980 g/L, sorption started extremely intensively (a record V0), demonstrating the sorbent’s ability to absorb large amounts of copper from concentrated solutions very quickly, although the overall efficiency (k2) was lower.

The data from this experiment is much more favorable for practical applications. They show that this particular sorbent is very well adapted under these conditions for the rapid extraction of copper from medium and highly concentrated solutions.

The copper sorption in this experiment was much more efficient and faster than in the previous data. A classic but very pronounced pattern is observed: a sharp increase in velocity and a gradual decrease in the velocity constant with increasing concentration. The sorbent demonstrated high kinetic activity with respect to copper ions. The largest amount of copper in absolute terms was extracted from the most concentrated solution with a concentration of 1.980 g/L. At the same time, the extraction efficiency remained consistently high for both dilute and concentrated solutions, which makes this sorbent promising for use in a wide range of initial copper concentrations, from wastewater treatment to extraction of valuable metal from technological solutions.

For both metals, especially in concentrated solutions, the initial sorption rate (v0) for DBA-EHG-PEI ionite is significantly higher than the rate of an industrial sorbent: for copper–2.6 times, for silver–1.2 times, that is, the synthesized ionite “captures” metal ions from the solution faster at the initial stage, which is It is a good indicator for technological processes where it is important to quickly reduce the concentration of metal.

In experiments with copper and silver, the k2 value for DBA-EChH-PEI is higher than that for Dowex, which indicates that the process of chemical interaction (chemisorption) with the active centers of DBA-EChH-PEI proceeds more efficiently during the entire contact time. This means not only a fast start, but also more optimal kinetics at all stages until equilibrium is reached.

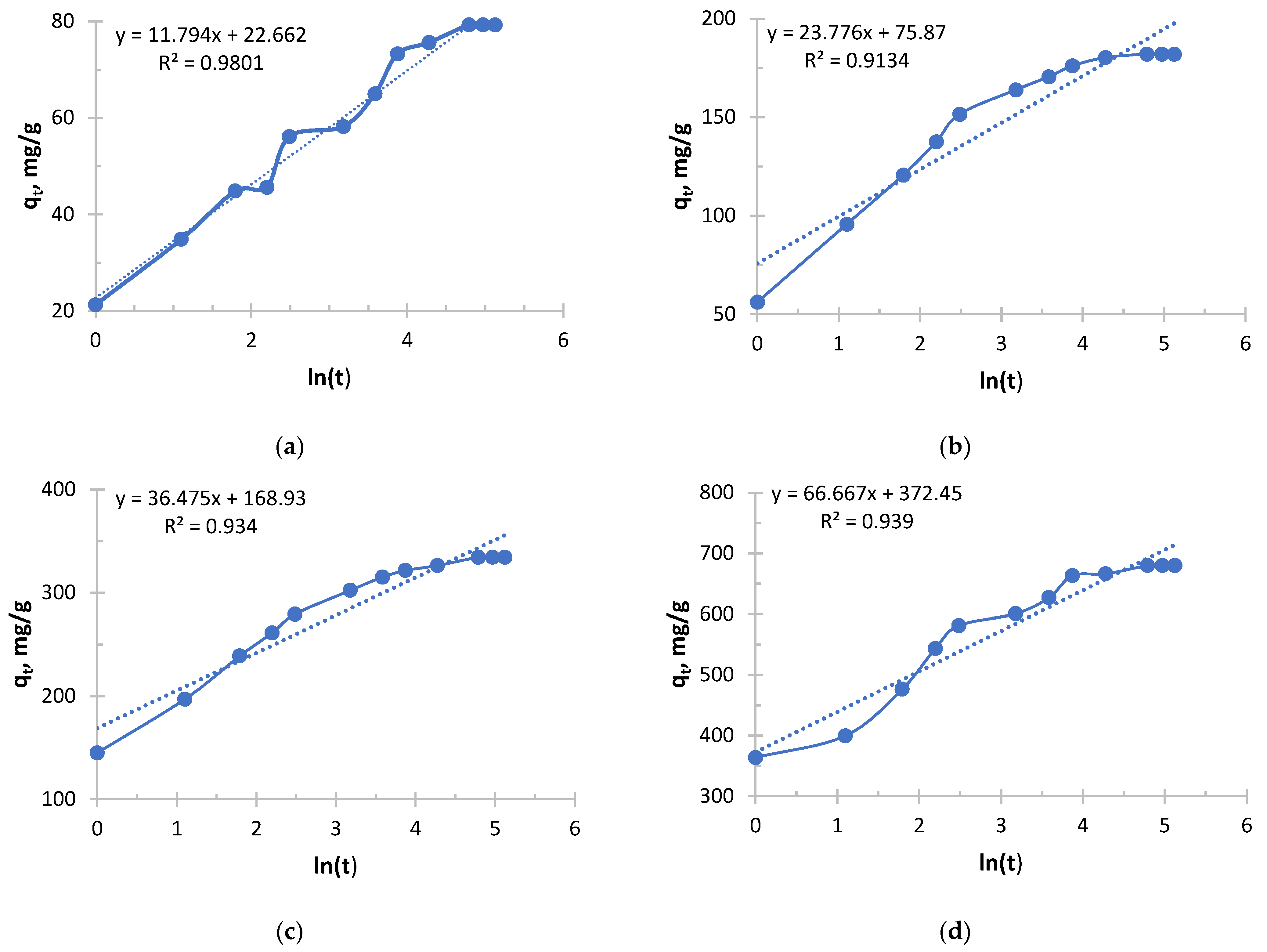

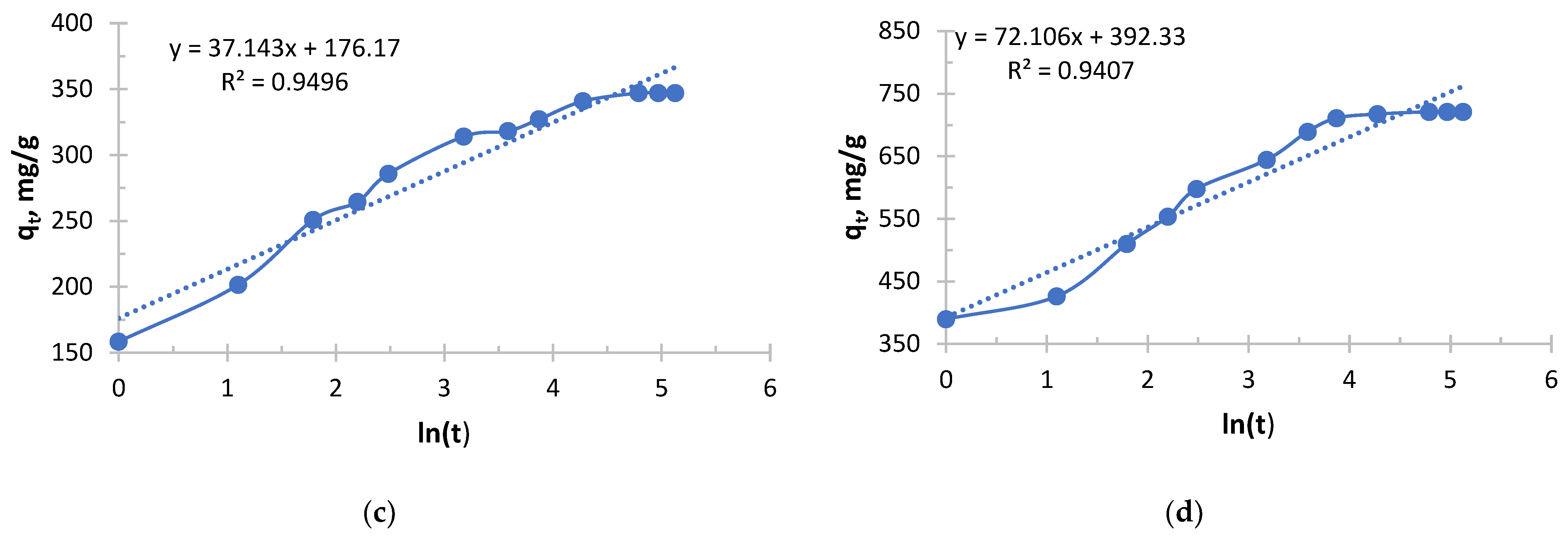

Silver sorption took place in radically different ways depending on the concentration, and the Elovich equation clearly demonstrates this from

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 and

Table 7 and

Table 8.

The process in more concentrated solutions started at a rate an order of magnitude higher than in less concentrated ones. High values of the α parameter show that the driving force of the process (concentration) is the decisive factor at the start. Even an increase in the concentration from 0.256 to 0.578 g/L leads to a tremendous increase in α.

Sorption in concentrated solutions was not only faster at the start, but also significantly more stable. A 6.2-fold decrease in the β parameter means that the sorption rate decreased much more slowly as the active centers were filled. This indicates that the high concentration of silver ions effectively compensates for the increasing difficulty of accessing the remaining active centers.

In the solution with the lowest concentration of 0.256 g/L, the process started at a relatively low speed and quickly exhausted easily accessible centers, slowing down sharply.

In the solution with the highest concentration of 2.050 g/L, sorption began with maximum intensity and maintained a high rate for a much longer time, allowing the sorbent to realize its full kinetic potential and, probably, a large capacity.

The analysis of the Elovich equation clearly shows that the use of this sorbent for the extraction of silver from concentrated solutions is highly effective. Concentrated solutions provide both maximum initial velocity and longer and more stable sorption, making the process more intensive and probably more productive.

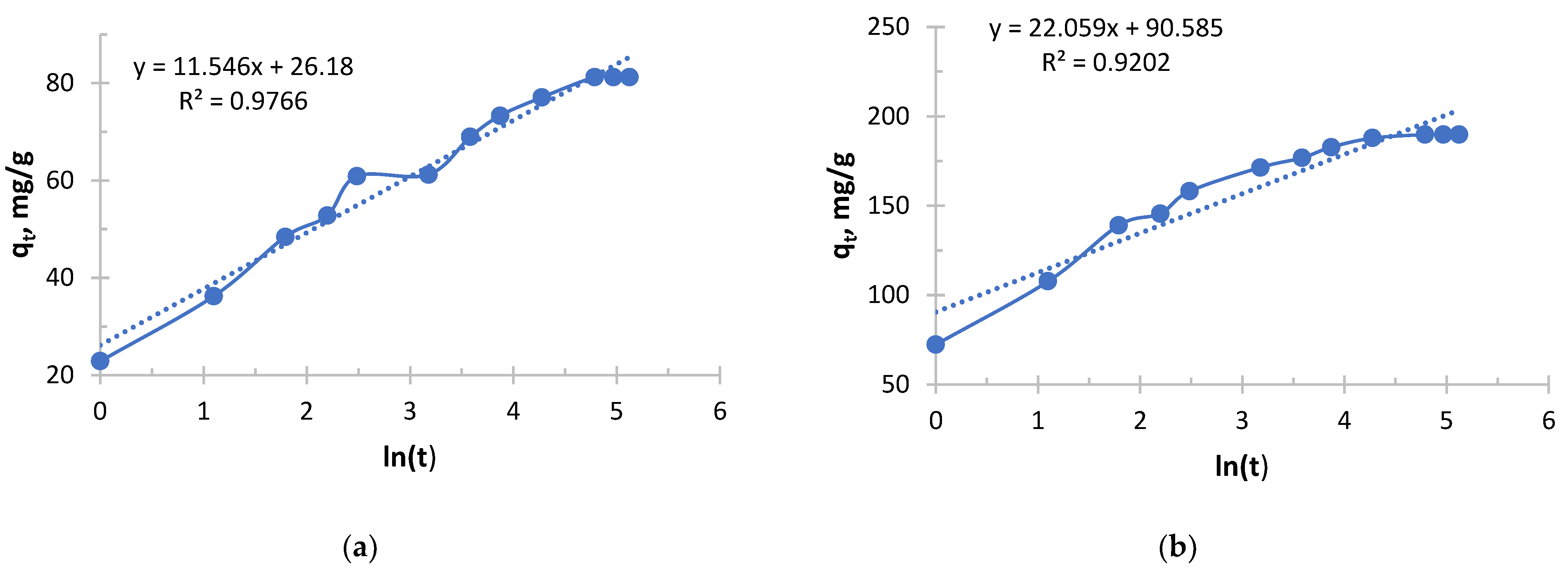

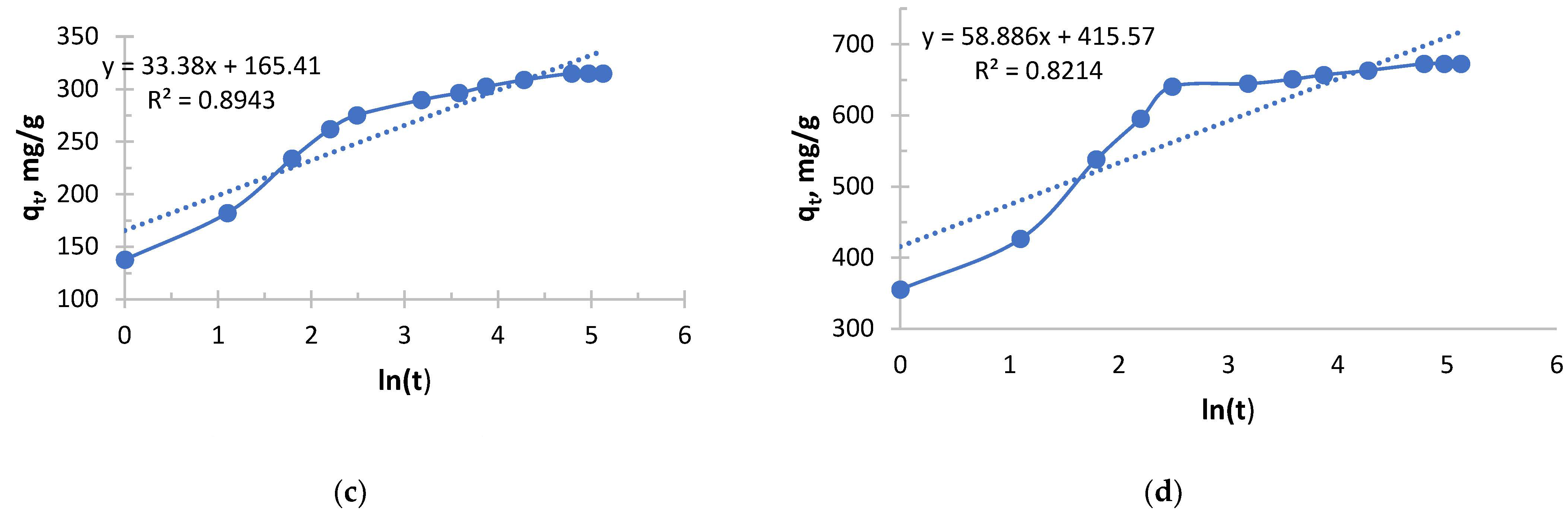

It follows from

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 and

Table 9 and

Table 10 that copper sorption with Ionite 2 was characterized by a strong dependence of kinetic parameters on the initial concentration. The key parameter, α, increased exponentially with its increase, reflecting the difference in the initial rate of the process by more than 170 orders of magnitude between the limiting concentrations. In parallel, a steady decrease in the β parameter was observed, which indicates a slower depletion of sorption capacity in concentrated solutions. In this case, the high concentration of copper ions compensates for the increasing difficulty of accessing the remaining active centers of the polymer. As a result, in a solution with a maximum concentration (1.980 g/L), the process was characterized by a high initial speed and stability, whereas in a dilute solution (0.156 g/L), sorption slowed down rapidly after the exhaustion of easily accessible centers. Therefore, high initial concentrations of copper are necessary for the effective manifestation of the kinetic properties of this sorbent.

Analysis of the Elovich model shows that the high concentration of ions in the solution better “compensates” for the increasing difficulty of accessing the remaining active centers. The sorbent retains its high activity for longer, which makes it possible to use its full capacity more efficiently.

Although DBA-EChH-PEI starts faster, it takes the same amount of time for it to fully saturate as its industrial counterpart. This may be due to the stage of slow intradiffusion kinetics in the late stages of the process, which limits both materials.