Surface Modifications of Zinc Oxide Particles with Chitosan, Polyethylene Glycol, Polyvinyl Alcohol, and Polyvinylpyrrolidone as Antibacterial Agents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of M8

2.3. Synthesis of ZnO

2.4. Synthesis of M8/ZnO

2.5. Evaluating Antibacterial Activities of Polymer Blends

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of M8 and M8/ZnO

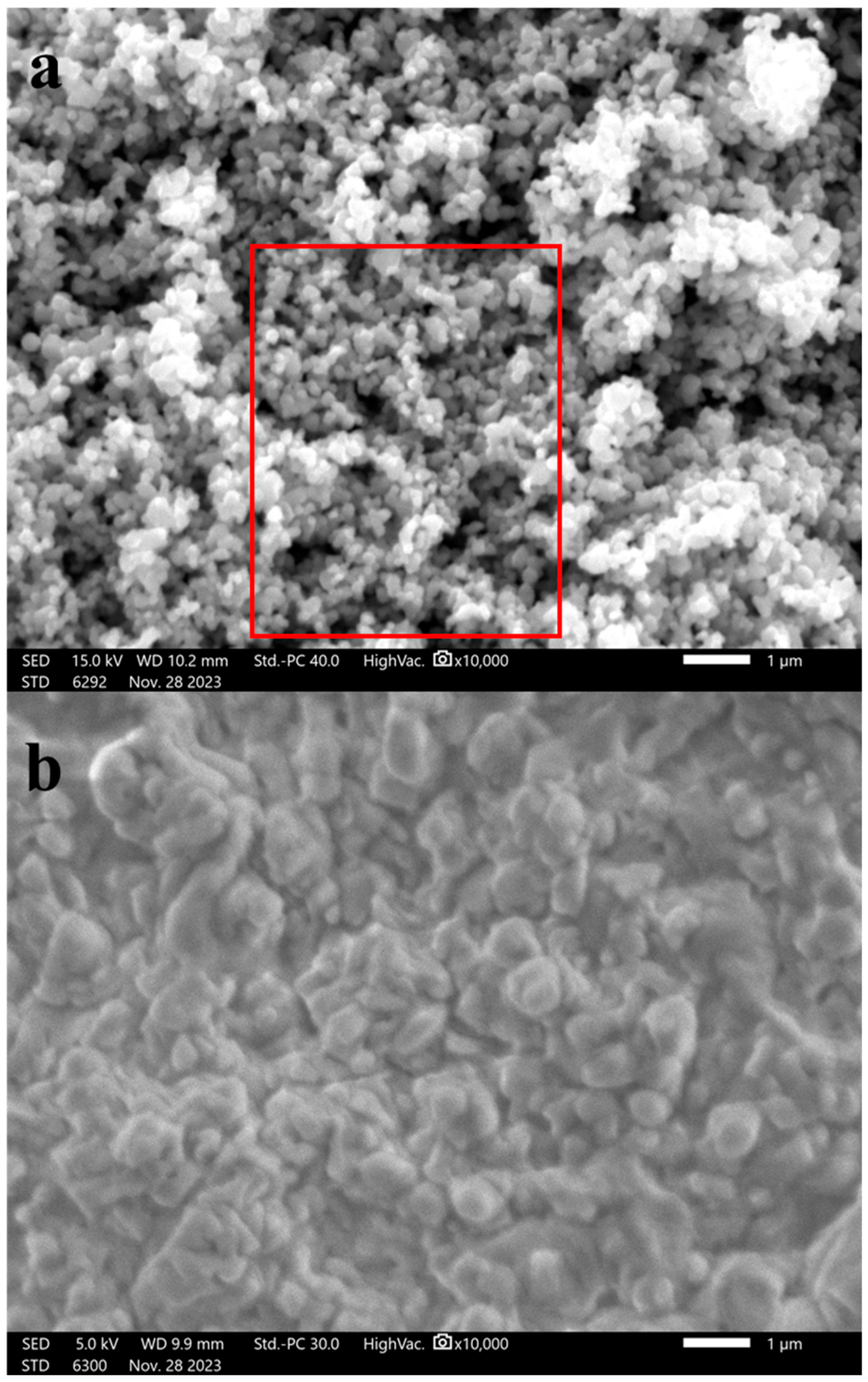

3.1.1. Scanning Electron Microscopes (SEMs)

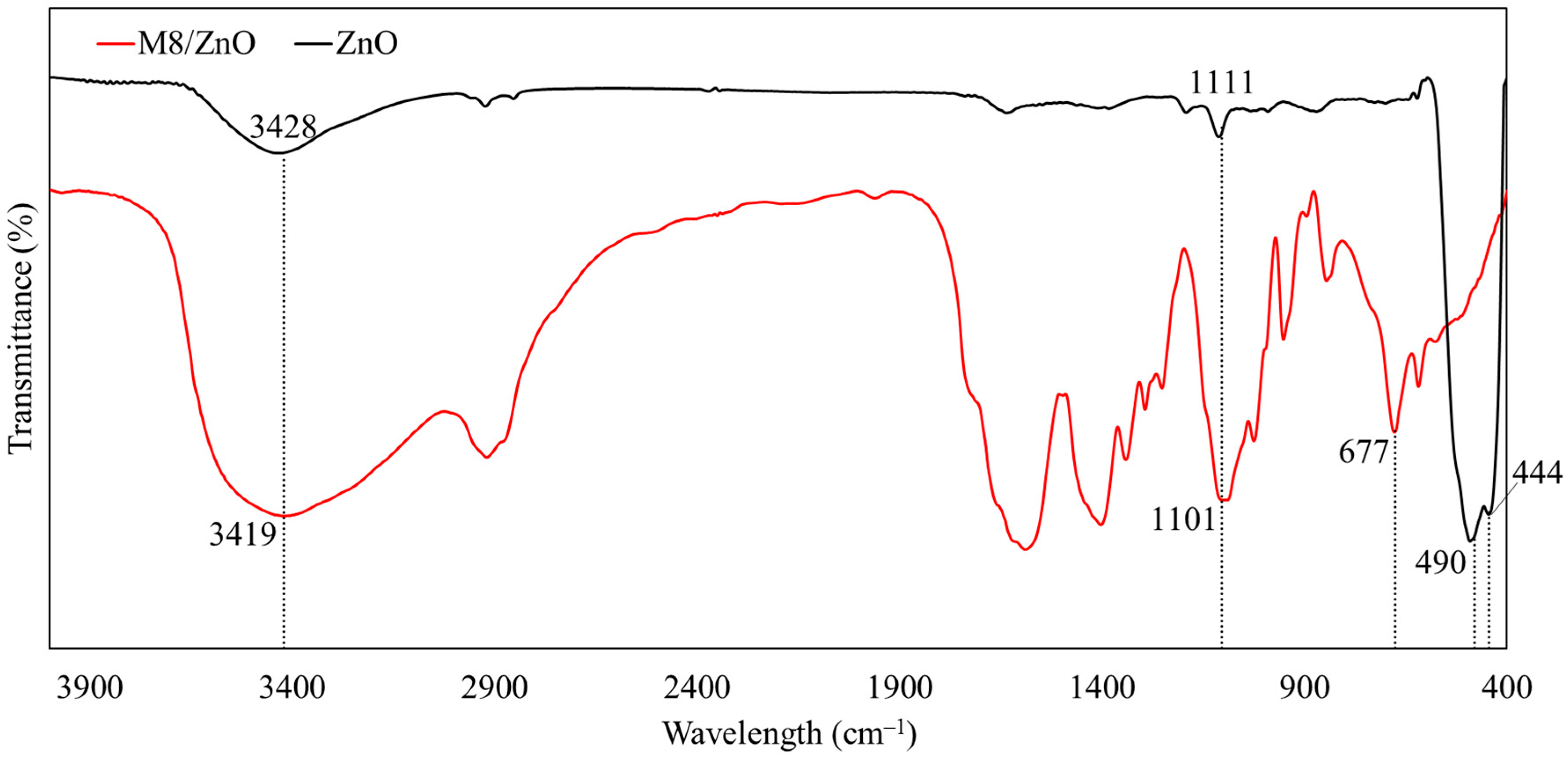

3.1.2. FTIR

3.1.3. Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS)

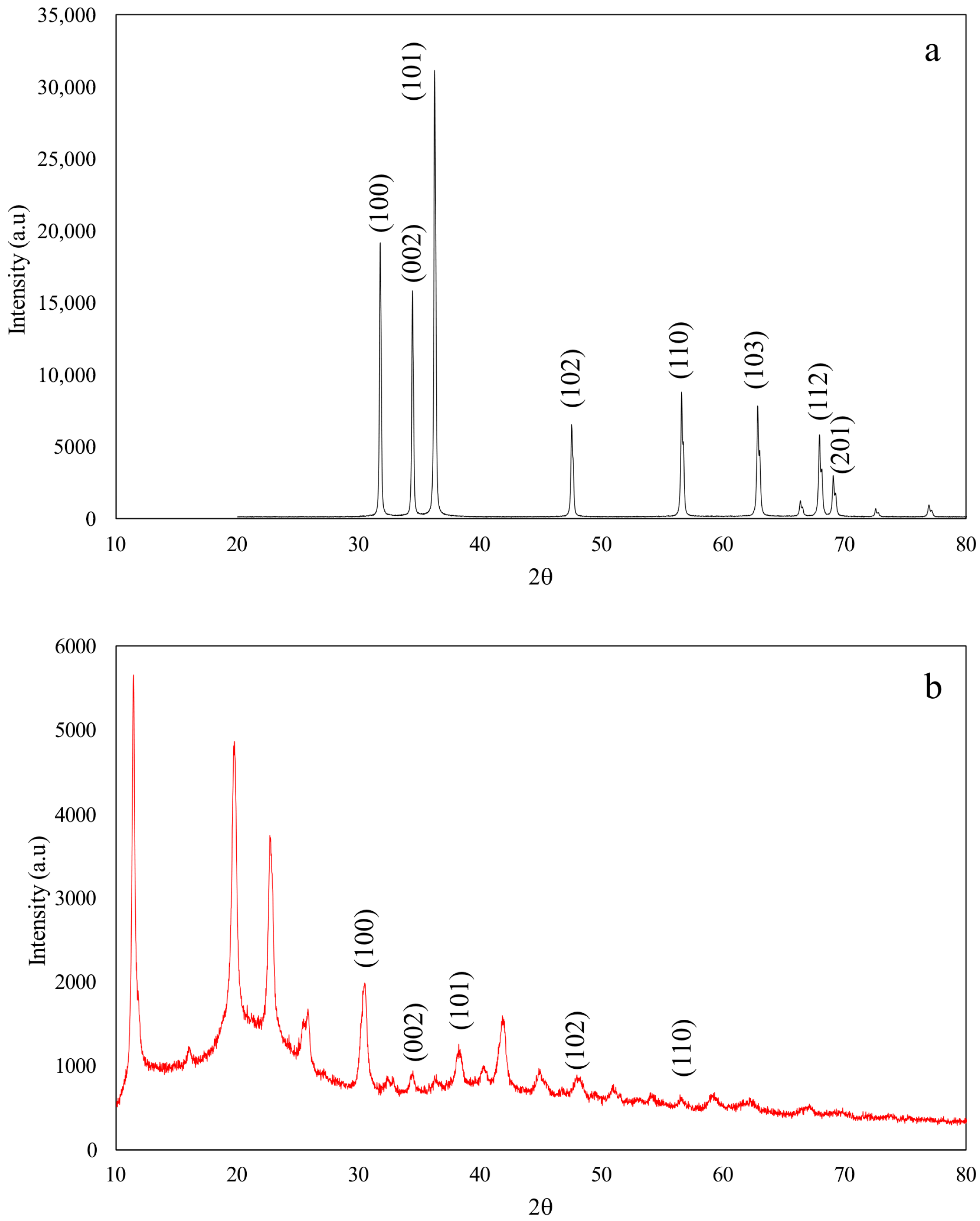

3.1.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

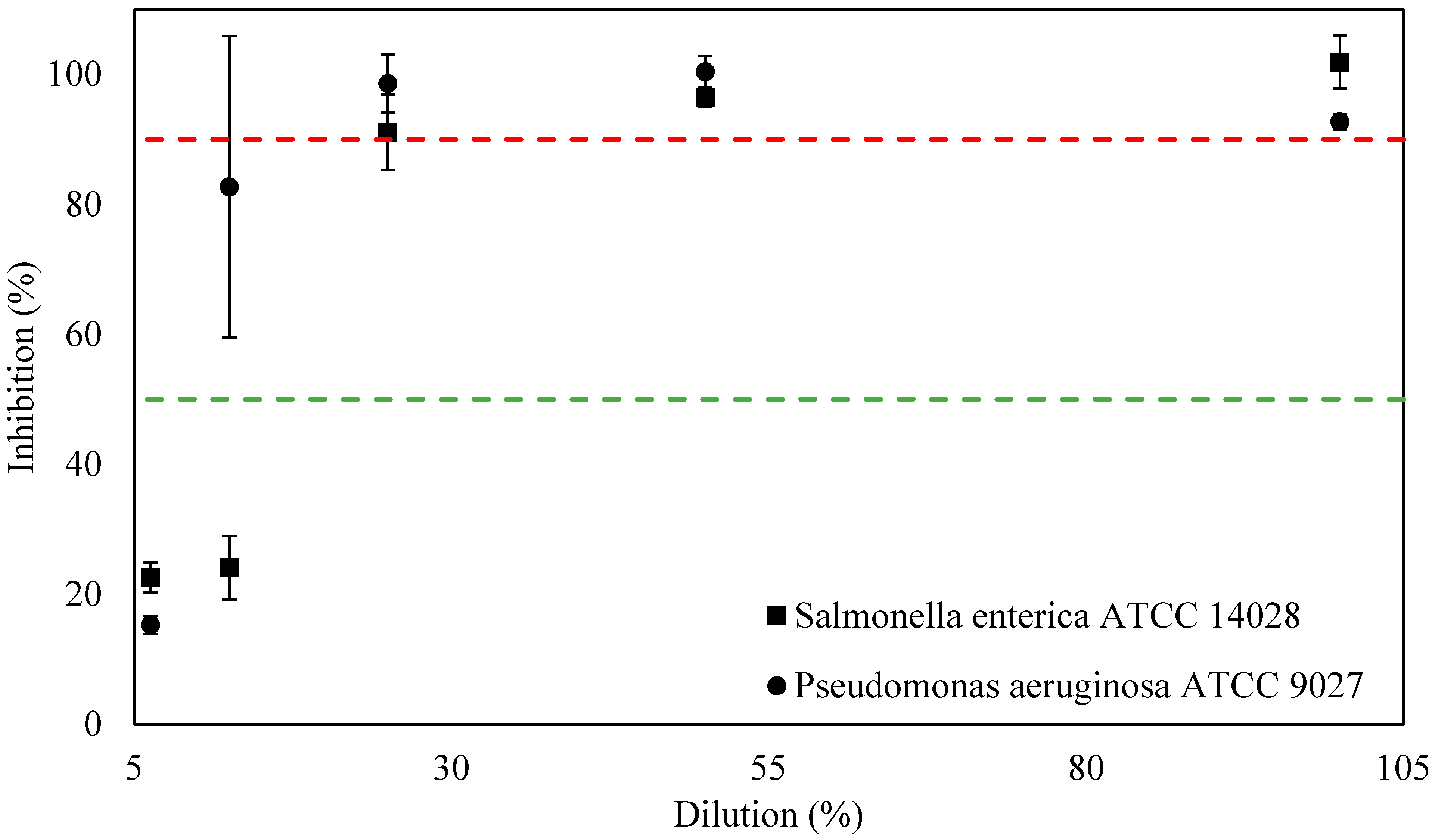

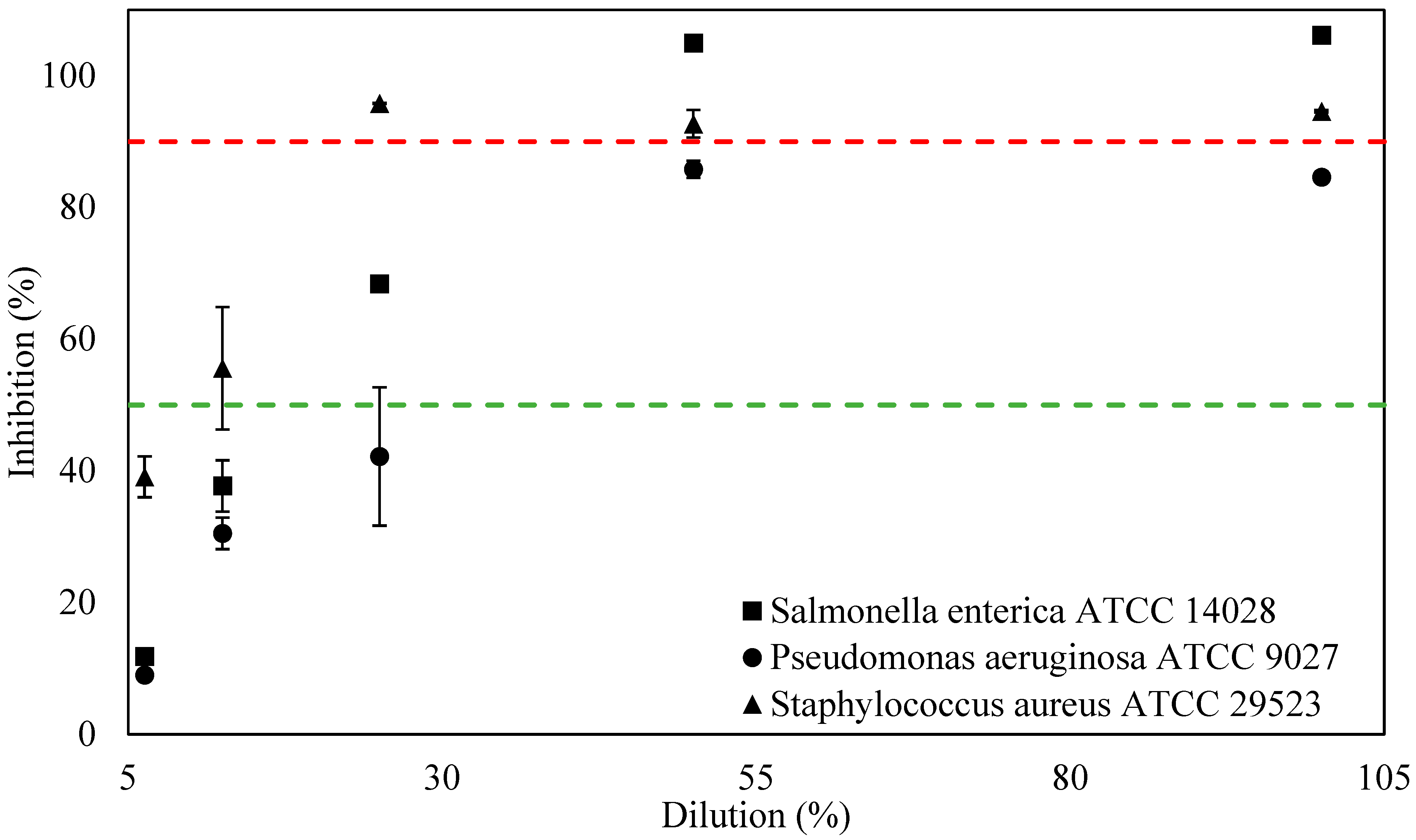

3.2. Antimicrobial Activities

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jain, A.; Duvvuri, L.S.; Farah, S.; Beyth, N.; Domb, A.J.; Khan, W. Antimicrobial Polymers. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 1969–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soe, P.E.; Han, W.W.; Sagili, K.D.; Satyanarayana, S.; Shrestha, P.; Htoon, T.T.; Tin, H.H. High Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus among Healthcare Facilities and Its Related Factors in Myanmar (2018–2019). Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.A.; Sharma-Kuinkel, B.K.; Maskarinec, S.A.; Eichenberger, E.M.; Shah, P.P.; Carugati, M.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler, V.G., Jr. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An Overview of Basic and Clinical Research. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capoluongo, E.; Lavieri, M.M.; Lesnoni-La Parola, I.; Ferraro, C.; Cristaudo, A.; Belardi, M.; Leonetti, F.; Mastroianni, A.; Cambieri, A.; Amerio, P. Genotypic and Phenotypic Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus Strains Isolated in Subjects with Atopic Dermatitis. Higher Prevalence of Exfoliative B Toxin Production in Lesional Strains and Correlation between the Markers of Disease Intensity and Colonization Density. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2001, 26, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Katsuoka, K.; Kawano, K.; Nishiyama, S. Comparative Study of Staphylococcal Flora on the Skin Surface of Atopic Dermatitis Patients and Healthy Subjects. J. Dermatol. 1994, 21, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuyama, M.; Wachi, Y.; Kitamura, K.; Suga, C.; Onuma, S.; Ikezawa, Z. Correlation between the Population of Staphylococcus aureus on the Skin and Severity of Score of Dry Type Atopic Dermatitis Condition. Nippon Hifuka Gakkai Zasshi 1997, 107, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Masako, K.; Hideyuki, I.; Shigeyuki, O.; Zenro, I. A Novel Method to Control the Balance of Skin Microflora: Part 1. Attack on Biofilm of Staphylococcus aureus without Antibiotics. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2005, 38, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Global Multifaceted Phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health 2015, 109, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, O.; Bhagat, M.; Gopalakrishnan, C.; Arunachalam, K.D. Ultrafine Dispersed CuO Nanoparticles and Their Antibacterial Activity. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2008, 3, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Webster, T.J. Bactericidal Effect of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles on Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, R.E.W. Resistance Mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Other Nonfermentative Gram-Negative Bacteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998, 27, S93–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komolafe, O. Antibiotic Resistance in Bacteria—An Emerging Public Health Problem. Malawi Med. J. 2004, 15, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowy, F.D. Staphylococcus aureus Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkey, P.M. The Growing Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 62, i1–i9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, B.; Grätzel, M. A Low-Cost, High-Efficiency Solar Cell Based on Dye-Sensitized Colloidal TiO2 Films. Nature 1991, 353, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, P.-O.; Andersson, A.; Wallenberg, L.R.; Svensson, B. Combustion of CO and Toluene; Characterisation of Copper Oxide Supported on Titania and Activity Comparisons with Supported Cobalt, Iron, and Manganese Oxide. J. Catal. 1996, 163, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuyu, T.; Yamazaki, O.; Ohji, K.; Wasa, K. Piezoelectric Thin Films of Zinc Oxide for Saw Devices. Ferroelectrics 1982, 42, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, W.-P.; Huang, T.-J. Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia Supported Copper Oxide Catalyst. J. Catal. 1996, 160, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Ray, B.; Ranjit, K.T.; Manna, A.C. Antibacterial Activity of ZnO Nanoparticle Suspensions on a Broad Spectrum of Microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 279, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, A.; Ahmed, A.S.; Oves, M.; Khan, M.S.; Habib, S.S.; Memic, A. Antimicrobial Activity of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 6003–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruparelia, J.P.; Chatterjee, A.K.; Duttagupta, S.P.; Mukherji, S. Strain Specificity in Antimicrobial Activity of Silver and Copper Nanoparticles. Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanimozhi, K.; Khaleel Basha, S.; Sugantha Kumari, V.; Kaviyarasu, K.; Maaza, M. In Vitro Cytocompatibility of Chitosan/PVA/Methylcellulose—Nanocellulose Nanocomposites Scaffolds Using L929 Fibroblast Cells. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 449, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobeen Amanulla, A.; Jasmine Shahina, S.K.; Sundaram, R.; Maria Magdalane, C.; Kaviyarasu, K.; Letsholathebe, D.; Mohamed, S.B.; Kennedy, J.; Maaza, M. Antibacterial, Magnetic, Optical and Humidity Sensor Studies of β-CoMoO4-Co3O4 Nanocomposites and Its Synthesis and Characterization. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 183, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviyarasu, K.; Maria Magdalane, C.; Kanimozhi, K.; Kennedy, J.; Siddhardha, B.; Subba Reddy, E.; Rotte, N.K.; Sharma, C.S.; Thema, F.T.; Letsholathebe, D.; et al. Elucidation of Photocatalysis, Photoluminescence and Antibacterial Studies of ZnO Thin Films by Spin Coating Method. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017, 173, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanakkumar, D.; Oualid, H.A.; Brahmi, Y.; Ayeshamariam, A.; Karunanaithy, M.; Saleem, A.M.; Kaviyarasu, K.; Sivaranjani, S.; Jayachandran, M. Synthesis and Characterization of CuO/ZnO/CNTs Thin Films on Copper Substrate and Its Photocatalytic Applications. OpenNano 2019, 4, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanakkumar, D.; Sivaranjani, S.; Kaviyarasu, K.; Ayeshamariam, A.; Ravikumar, B.; Pandiarajan, S.; Veeralakshmi, C.; Jayachandran, M.; Maaza, M. Synthesis and Characterization of ZnO–CuO Nanocomposites Powder by Modified Perfume Spray Pyrolysis Method and Its Antimicrobial Investigation. J. Semicond. 2018, 39, 033001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, M.; Niranjan, R.; Thangam, R.; Madhan, B.; Pandiyarasan, V.; Ramachandran, C.; Oh, D.-H.; Venkatasubbu, G.D. Investigations on the Antimicrobial Activity and Wound Healing Potential of ZnO Nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 479, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallo Da Silva, B.; Abuçafy, M.P.; Berbel Manaia, E.; Oshiro Junior, J.A.; Chiari-Andréo, B.G.; Pietro, R.C.R.; Chiavacci, L.A. Relationship Between Structure and Antimicrobial Activity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: An Overview. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 9395–9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejczak-Radzimska, A.; Jesionowski, T. Zinc Oxide—From Synthesis to Application: A Review. Materials 2014, 7, 2833–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navale, G.R.; Shinde, S.S. Antimicrobial Activity of ZnO Nanoparticles against Pathogenic Bacteria and Fungi. JSM Nanotechnol. Nanomed. 2015, 3, 1033. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, M.M.; Bouchami, O.; Tavares, A.; Córdoba, L.; Santos, C.F.; Miragaia, M.; De Fátima Montemor, M. New Insights into Antibiofilm Effect of a Nanosized ZnO Coating against the Pathogenic Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 28157–28167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, V.; Mishra, N.; Gadani, K.; Solanki, P.S.; Shah, N.A.; Tiwari, M. Mechanism of Anti-Bacterial Activity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle Against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandapalli, P.K.; Labala, S.; Chawla, S.; Janupally, R.; Sriram, D.; Venuganti, V.V.K. Polymer-Gold Nanoparticle Composite Films for Topical Application: Evaluation of Physical Properties and Antibacterial Activity. Polym. Compos. 2017, 38, 2829–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Chen, X.-G.; Park, H.-J.; Liu, C.-G.; Liu, C.-S.; Meng, X.-H.; Yu, L.-J. Effect of MW and Concentration of Chitosan on Antibacterial Activity of Escherichia coli. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 64, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Chen, X.G.; Xing, K.; Park, H.J. Antimicrobial Properties of Chitosan and Mode of Action: A State of the Art Review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 144, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.F.; Guan, Y.L.; Yang, D.Z.; Li, Z.; De Yao, K. Antibacterial Action of Chitosan and Carboxymethylated Chitosan. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 79, 1324–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.-Y.; Zhu, J.-F. Study on Antimicrobial Activity of Chitosan with Different Molecular Weights. Carbohydr. Polym. 2003, 54, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, L.; Tran, K. Relationship between the Polymer Blend Using Chitosan, Polyethylene Glycol, Polyvinyl Alcohol, Polyvinylpyrrolidone, and Antimicrobial Activities against Staphylococcus aureus. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, I.; Flores, P.; Rodríguez-Llamazares, S. Antibacterial Nanocomposite of Poly(Lactic Acid) and ZnO Nanoparticles Stabilized with Poly(Vinyl Alcohol): Thermal and Morphological Characterization. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2019, 58, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutul, T.; Rusu, E.; Condur, N.; Ursaki, V.; Goncearenco, E.; Vlazan, P. Preparation of Poly(N-Vinylpyrrolidone)-Stabilized ZnO Colloid Nanoparticles. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2014, 5, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, K.; Sivasangari, D.; Kim, H.-S.; Murugadoss, G.; Kathalingam, A. Electrospun Nanofibrous ZnO/PVA/PVP Composite Films for Efficient Antimicrobial Face Masks. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 29197–29204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, M.A.; Montazer, M.; Harifi, T.; Karimi, P. Flower Buds like PVA/ZnO Composite Nanofibers Assembly: Antibacterial, in Vivo Wound Healing, Cytotoxicity and Histological Studies. Polym. Test. 2021, 93, 106914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, F.B. Characterization of Low-Temperature-Grown ZnO Nanoparticles: The Effect of Temperature on Growth. J. Phys. Commun. 2022, 6, 075011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalakshmi, S.; Hema, N.; Vijaya, P.P. In Vitro Biocompatibility and Antimicrobial Activities of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) Prepared by Chemical and Green Synthetic Route—A Comparative Study. BioNanoScience 2020, 10, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Yan, D.; Yin, G.; Liao, X.; Kang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Huang, D.; Hao, B. Toxicological Effect of ZnO Nanoparticles Based on Bacteria. Langmuir 2008, 24, 4140–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handore, K.; Bhavsar, S.; Horne, A.; Chhattise, P.; Mohite, K.; Ambekar, J.; Pande, N.; Chabukswar, V. Novel Green Route of Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles by Using Natural Biodegradable Polymer and Its Application as a Catalyst for Oxidation of Aldehydes. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A 2014, 51, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, L.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Tran, K.; Huynh, K.G. Surface Modifications of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles with Chitosan, Polyethylene Glycol, Polyvinyl Alcohol, and Polyvinylpyrrolidone as Methylene Blue Adsorbent Beads. Polymers 2024, 16, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, L.; Le, Q.N.; Tran, K.; Huynh, A.H. Surface Modifications of Silver Nanoparticles with Chitosan, Polyethylene Glycol, Polyvinyl Alcohol, and Polyvinylpyrrolidone as Antibacterial Agents against Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella enterica. Polymers 2024, 16, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedurkar, S.; Maurya, C.; Mahanwar, P. Biosynthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Ixora Coccinea Leaf Extract—A Green Approach. OJSTA 2016, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpana, V.N.; Kataru, B.A.S.; Sravani, N.; Vigneshwari, T.; Panneerselvam, A.; Devi Rajeswari, V. Biosynthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Culture Filtrates of Aspergillus Niger: Antimicrobial Textiles and Dye Degradation Studies. OpenNano 2018, 3, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, A.; Goswami, N. Structural and Optical Investigations of Oxygen Defects in Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. In Solid State Physics, Proceedings of the 59th DAE Solid State Physics Symposium 2014, Tamilnadu, India, 16–20 December 2014; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2015; p. 050023. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, C.Y.; Molina, R.M.; Louzada, A.; Murdaugh, K.M.; Donaghey, T.C.; Brain, J.D. Effects of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Kupffer Cell Phagosomal Motility, Bacterial Clearance, and Liver Function. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 4173–4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espitia, P.J.P.; de Fátima Ferreira Soares, N.; dos Reis Coimbra, J.S.; de Andrade, N.J.; Cruz, R.S.; Medeiros, E.A.A. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Antimicrobial Activity and Food Packaging Applications. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 1447–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunath, A.; Perumal, E. Metal Oxide Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agents: A Promise for the Future. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 49, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Mishra, A. Antibacterial Polymers—A Mini Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 17156–17161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momtaz, F.; Momtaz, E.; Mehrgardi, M.A.; Momtaz, M.; Narimani, T.; Poursina, F. Enhanced Antibacterial Properties of Polyvinyl Alcohol/Starch/Chitosan Films with NiO–CuO Nanoparticles for Food Packaging. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmavathy, N.; Vijayaraghavan, R. Enhanced Bioactivity of ZnO Nanoparticles—An Antimicrobial Study. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2008, 9, 035004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brayner, R.; Ferrari-Iliou, R.; Brivois, N.; Djediat, S.; Benedetti, M.F.; Fiévet, F. Toxicological Impact Studies Based on Escherichia coli Bacteria in Ultrafine ZnO Nanoparticles Colloidal Medium. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 866–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawai, J. Quantitative Evaluation of Antibacterial Activities of Metallic Oxide Powders (ZnO, MgO and CaO) by Conductimetric Assay. J. Microbiol. Methods 2003, 54, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, K.R.; Koodali, R.T.; Manna, A.C. Size-Dependent Bacterial Growth Inhibition and Mechanism of Antibacterial Activity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2011, 27, 4020–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawale, J.S.; Dey, K.K.; Pasricha, R.; Sood, K.N.; Srivastava, A.K. Synthesis and Characterization of ZnO Tetrapods for Optical and Antibacterial Applications. Thin Solid Film. 2010, 519, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.-E.; Li, Z.-H.; Zheng, W.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Jin, Y.-F.; Tang, Z.-X. Synthesis, Antibacterial Activity, Antibacterial Mechanism and Food Applications of ZnO Nanoparticles: A Review. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2014, 31, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chemicals | Wavelength (cm−1) | Functional Group | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| M8/ZnO | 3419 | –OH stretching vibration of PVA, PVP, PEG secondary –NH groups of CS + AA | [38] |

| 1589–1402 | Absorption of PVA on ZnONPs | [39] | |

| 1341 | PVP–ZnO covalent bonds | [40] | |

| 1293 | C–H bond in pyranose ring of CS + AA | [38] | |

| 1101 | C–O stretching vibration | [41] | |

| 1024 | C–OH stretching vibration | [41] | |

| 677–678 | High-purity ZnONPs Stretching vibration of Zn–O in PVA | [42,43] | |

| ZnO | 3428 | Stretching vibration of O–H groups | [44] |

| 1111 | C–O stretching band | [44] | |

| 444–490 | Stretching vibration of Zn–O bond | [45,46] |

| Element | ZnO | M8/ZnO |

|---|---|---|

| C | - | 44.90 ± 0.27 |

| N | - | 2.83 ± 0.26 |

| O | 18.93 ± 0.22 | 49.16 ± 0.57 |

| Al | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.03 |

| Si | 0.09 ± 0.03 | - |

| S | 0.22 ± 0.03 | - |

| Zn | 80.59 ± 1.41 | 2.93 ± 0.37 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

| Chemical Formula | ZnO | M8/ZnO |

|---|---|---|

| C | - | 79.86 ± 0.48 |

| N | - | 12.06 ± 1.12 |

| O | - | |

| Al2O3 | 0.27 ± 0.06 | 0.63 ± 0.10 |

| SiO2 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | - |

| SO3 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | - |

| ZnO | 99.03 ± 1.71 | 7.45 ± 0.93 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Doan, L.; Tran, K.; Huynh, K.G.; Nguyen, T.M.D.; Tang, L.V.H. Surface Modifications of Zinc Oxide Particles with Chitosan, Polyethylene Glycol, Polyvinyl Alcohol, and Polyvinylpyrrolidone as Antibacterial Agents. Polymers 2025, 17, 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243283

Doan L, Tran K, Huynh KG, Nguyen TMD, Tang LVH. Surface Modifications of Zinc Oxide Particles with Chitosan, Polyethylene Glycol, Polyvinyl Alcohol, and Polyvinylpyrrolidone as Antibacterial Agents. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243283

Chicago/Turabian StyleDoan, Linh, Khoa Tran, Khanh G. Huynh, Tu M. D. Nguyen, and Lam V. H. Tang. 2025. "Surface Modifications of Zinc Oxide Particles with Chitosan, Polyethylene Glycol, Polyvinyl Alcohol, and Polyvinylpyrrolidone as Antibacterial Agents" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243283

APA StyleDoan, L., Tran, K., Huynh, K. G., Nguyen, T. M. D., & Tang, L. V. H. (2025). Surface Modifications of Zinc Oxide Particles with Chitosan, Polyethylene Glycol, Polyvinyl Alcohol, and Polyvinylpyrrolidone as Antibacterial Agents. Polymers, 17(24), 3283. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243283