Carbon Footprint of Plastic Bags and Polystyrene Dishes vs. Starch-Based Biodegradable Packaging in Amazonian Settlements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Functional Units Evaluated

2.3. Footprint Estimation Approach

- (1)

- Raw Materials Enclosed: Energy for their obtention, carbon content in the final material of each product. Cassava and plantain leaves are produced in small agricultural plots without the use of machinery or external inputs as fertilizers or insecticides. No irrigation is needed as the region has a tropical rainforest, characterized by high humidity. Due to this low input production, the average of cassava production was estimated at 3 kg/plant, according to local field estimations performed by the authors.

- (2)

- Product Production Process Encloses: Energy and source of energy to process raw materials and manufacture the final product. Cassava starch is produced by artisanal techniques by local Indigenous people by hand or using a low 5HP gasoline motor for grating. Plantain leaves do not have any previous treatment. Dried plantain leaves are collected directly from the agricultural plots and brought to the local pilot factory.

- (3)

- Transportation encloses emissions, which are calculated using the average distance traveled from product manufacturing facilities to downtown, where the products are sought from small stores or direct users (in terms of the cheapest transport available to reach that place).

- (4)

- The waste produced was estimated based on the average recycling of plastic in the region. Calculations consider that only 4% of plastic is recycled, according to the regional plan for the integrated management of solid residues–PGIRS 2017 [25]. Calculations will consider the carbon remaining and the GHG emissions based on the degradability of each product (from degradability assays carried out by the Amazonian Institute for Scientific Research—SINCHI, in situ), and the recalcitrant carbon remaining in the environment and the cost that might be required for their final decomposition into non-toxic final compounds. Additionally, calculations of the consumption of the containers will be estimated, based on the direct interviews with bag distributors, triangulating their answers with interviews with commercial stores about the consumption of this particular bag per month.

2.4. Carbon Footprint Assessment for Raw Material Composition

2.5. Energy Consumption and Carbon Footprint Assessment in Composite TPS-Cassava Bag Production

2.6. Carbon Footprint Analysis of Transportation Processes

2.7. Estimation of the Carbon Footprint of Final Life of Each Product

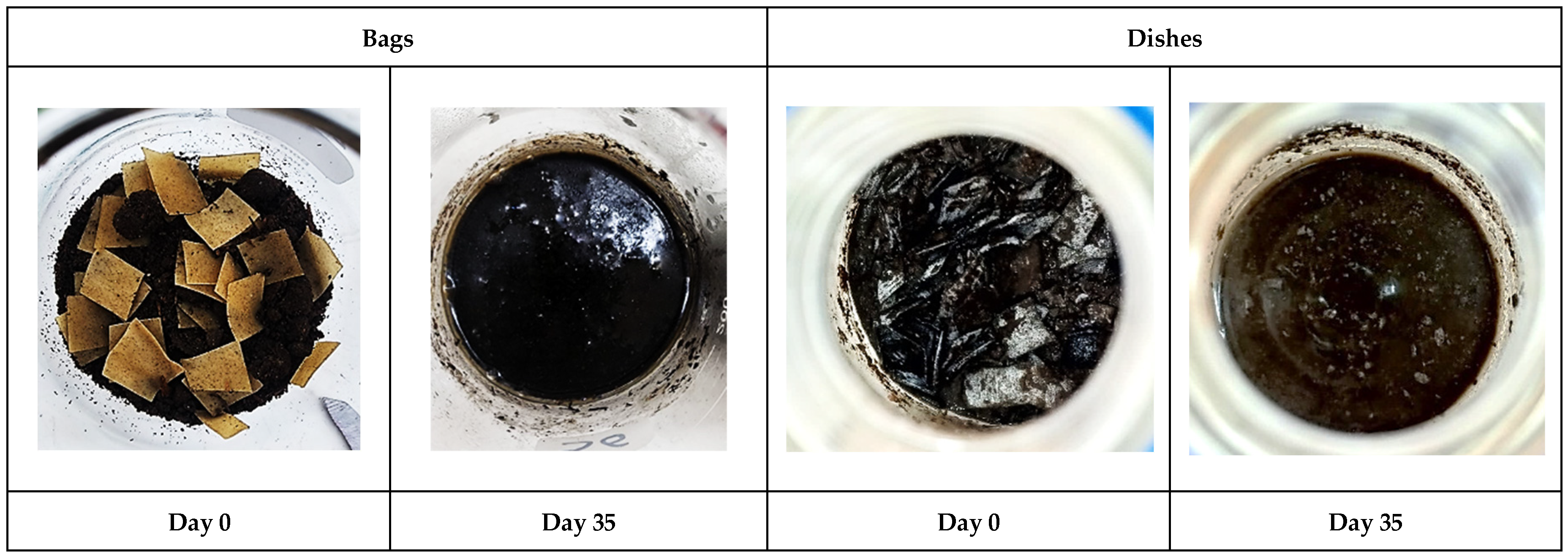

2.7.1. Biodegradability Test of Composite TPS-Cassava Bags and Dishes at Laboratory Conditions

2.7.2. Accumulation of Non-Biodegradable Residues

- Rnon-biodegradable: Non-biodegradable residues released annually (kg).

- Cbag: Annual consumption of bags (units).

- Wbag: Weight of each bag (kg).

- % Non-Biodegradable: Proportion of non-biodegradable components in the material.

- Degradation Rate: Annual degradation rate of non-biodegradable content (%).

3. Results

3.1. Carbon Footprint Estimation of Each Package

3.2. Estimation of the Carbon Footprint of End of Life of Each Product

3.3. Accumulation of Non-Biodegradable Residues of TPS-Cassava/Plantain Leaves/Glycerol-Based and Plastic Packages

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegmann, P.; Daioglou, V.; Londo, M.; Van Vuuren, D.P.; Junginger, M. Plastic Futures and Their CO2 Emissions. Nature 2022, 612, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayavel, S.; Govindaraju, B.; Michael, J.R.; Viswanathan, B. Impacts of Micro and Nanoplastics on Human Health. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2024, 48, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chatterjee, S. Microplastic pollution, a threat to marine ecosystem and human health: A short review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 21530–21547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bressanin, J.M.; Sampaio, I.L.D.M.; Geraldo, V.C.; Klein, B.C.; Chagas, M.F.; Bonomi, A.; Filho, R.M.; Cavalett, O. Techno-Economic and Environmental Assessment of Polylactic Acid Production Integrated with the Sugarcane Value Chain. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Lee, S.H.; Khalina, A. Development and Processing of PLA, PHA, and Other Biopolymers. In Advanced Processing, Properties, and Applications of Starch and Other Bio-Based Polymers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 51–55. ISBN 978-0-12-819661-8. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.; Singhal, S.; Godiya, C.B.; Kumar, S. Prospects and Applications of Starch-Based Biopolymers. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2023, 103, 6907–6926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.O.; Olivato, J.B.; Bilck, A.P.; Zanela, J.; Grossmann, M.V.E.; Yamashita, F. Biodegradable Trays of Thermoplastic Starch/Poly (Lactic Acid) Coated with Beeswax. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.C.M.; Molina, G.; Pelissari, F.M. Biodegradable Trays Based on Cassava Starch Blended with Agroindustrial Residues. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 183, 107682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Leeke, G.A.; Moretti, C.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Mu, L.; et al. Replacing Traditional Plastics with Biodegradable Plastics: Impact on Carbon Emissions. Engineering 2024, 32, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Awasthi, A.K.; Wei, F.; Tan, Q.; Li, J. Single-Use Plastics: Production, Usage, Disposal, and Adverse Impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 141772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Suh, S. Strategies to Reduce the Global Carbon Footprint of Plastics. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Brandão, M.; Cullen, J.M. Replacing Plastics with Alternatives Is Worse for Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Most Cases. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 2716–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essel, R.E.; Engel, L.; Carus, M. Sources of Microplastics Relevant to Marine Protection in Germany; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Chan, F.K.S.; Johnson, M.F.; He, J.; Stanton, T. A Review of Microplastic Pollution Characteristics in Global Urban Freshwater Catchments. In Advances in Human Services and Public Health; Joo, S.H., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 28–48. ISBN 978-1-7998-9723-1. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, J.; Friot, D. Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: A Global Evaluation of Sources; IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-2-8317-1827-9. [Google Scholar]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebreton, L.C.M.; Van Der Zwet, J.; Damsteeg, J.-W.; Slat, B.; Andrady, A.; Reisser, J. River Plastic Emissions to the World’s Oceans. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, J.; Dubois, C.; Kounina, A.; Puydarrieux, P. Review of Plastic Footprint Methodologies: Laying the Foundation for the Development of a Standardised Plastic Footprint Measurement Tool; IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-2-8317-1990-0. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, A.; Saffron, C.M.; Manjure, S.; Narayan, R. Biobased Compostable Plastics End-of-Life: Environmental Assessment Including Carbon Footprint and Microplastic Impacts. Polymers 2024, 16, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olanrewaju, O.I.; Enegbuma, W.I.; Donn, M. Challenges in Life Cycle Assessment Implementation for Construction Environmental Product Declaration Development: A Mixed Approach and Global Perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 49, 502–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.; Rothman, R. Life Cycle Assessment of Bio-Based and Fossil-Based Plastic: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-M.; Inaba, A. Life Cycle Assessment: Best Practices of International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 14040 Series; Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC): Suwon, Republic of Korea, 2004; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- Garavito, J.; Castellanos-González, S.; Peña-Venegas, C.P.; Castellanos, D. Development and Characterization of Reinforced Flexible Packaging Based on Amazonian Cassava Starch Through Flat Sheet Extrusion. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao Cardona, L.F.; Castillo Aguilar, M.C.; Moreno Méndez, J.O.; Marín López, C.; Maldonado, A.; Castrodelrío Ceballos, J.A. Guía Para La Formulación, Implementación, Evaluación, Seguimiento, Control y Actualización de Los Planes de Gestión Integral de Residuos Sólidos (PGIRS); Ministerio de Vivienda, Ciudad y Territorio: Bogotá, Colombia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- CarbonCloud CarbonData. Climate Footprint Data on Food Products. Available online: https://www.carboncloud.io/carbondata/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Chen, F.; Lei, J.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, X. A Comparative Study on the Average CO2 Emission Factors of Electricity of China. Energies 2025, 18, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECTA; CEFIC; ECIC. Guidelines for Measuring and Managing CO2 Emission from Freight Transport Operations; ECTA: Brussels, Belgium; CEFIC: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D5338-15R21; Standard Test Method for Determining Aerobic Biodegradation of Plastic Materials Under Controlled Composting Conditions, Incorporating Thermophilic Temperatures. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Withana, P.A.; Yuan, X.; Im, D.; Choi, Y.; Bank, M.S.; Lin, C.S.K.; Hwang, S.Y.; Ok, Y.S. Biodegradable Plastics in Soils: Sources, Degradation, and Effects. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2025, 27, 3321–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Flury, M. Unlocking the Potentials of Biodegradable Plastics with Proper Management and Evaluation at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations. npj Mater. Sustain. 2024, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fan, X.; Zhang, R.; Pan, X.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Liu, Y. Biodegradation characterization and mechanism of low-density polyethylene by the enriched mixed-culture from plastic-contaminated soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 494, 138530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Channab, B.-E.; El Idrissi, A.; Zahouily, M.; Essamlali, Y.; White, J.C. Starch-Based Controlled Release Fertilizers: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 238, 124075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quispe, C.A.G.; Coronado, C.J.R.; Carvalho, J.A., Jr. Glycerol: Production, Consumption, Prices, Characterization and New Trends in Combustion. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglaya, I. Life Cycle Analysis of Nonpetroleum Based Wax. Master’s Thesis, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.; Wu, F.; Wang, D.; You, J. Estimated Material Metabolism and Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emission of Major Plastics in China: A Commercial Sector-Scale Perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 180, 106161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veliz, K.; Chico-Santamarta, L.; Ramirez, A.D. The Environmental Profile of Ecuadorian Export Banana: A Life Cycle Assessment. Foods 2022, 11, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asunis, F.; De Gioannis, G.; Francini, G.; Lombardi, L.; Muntoni, A.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R.; Rossi, A.; Spiga, D. Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Polyhydroxyalkanoates Production from Cheese Whey. Waste Manag. 2021, 132, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.K. Comparing CO2 Emissions from Different Energy Sources. Available online: https://www.cowi.com/news-and-press/news/2023/comparing-co2-emissions-from-different-energy-sources/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Core Writing Team IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jumaidin, R.; Diah, N.A.; Ilyas, R.A.; Alamjuri, R.H.; Yusof, F.A.M. Processing and Characterisation of Banana Leaf Fibre Reinforced Thermoplastic Cassava Starch Composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yu, J.; Kennedy, J.F. Studies on the Properties of Natural Fibers-Reinforced Thermoplastic Starch Composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2005, 62, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, F.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Guo, A.; Zhang, C.; Liu, P. Research on Thermoplastic Starch and Different Fiber Reinforced Biomass Composites. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 49824–49830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Barbir, J.E.; Carpio-Vallejo, A.D.; Voronova, V. Decarbonising the plastic industry: A review of carbon emissions in the lifecycle of plastics production. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 999, 180337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehedi, T.H.; Gemechu, E.; Kumar, A. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions and energy footprints of utility-scale solar energy systems. Appl. Energy 2022, 314, 118918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczak, H. Energy Inputs on the Production of Plastic Products. J. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 23, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbelyiova, L.; Malefors, C.; Lalander, C.; Wikström, F.; Eriksson, M. Paper vs Leaf: Carbon Footprint of Single-Use Plates Made from Renewable Materials. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Li, M.; Qian, T.; Chen, J.; Pan, T. Influence of Surfactants on Interfacial Microbial Degradation of Hydrophobic Organic Compounds. Catalysts 2025, 15, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoezer, N.; Gurung, D.B.; Wangchuk, K. Environmental Toxicity, Human Hazards and Bacterial Degradation of Polyethylene. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2023, 22, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacharodi, A.; Hassan, S.; Meenatchi, R.; Bhat, M.A.; Hussain, N.; Arockiaraj, J.; Ngo, H.H.; Sharma, A.; Nguyen, H.T.; Pugazhendhi, A. Mitigating microplastic pollution: A critical review on the effects, remediation, and utilization strategies of microplastics. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Mass Fraction | Factor of Emission (kg CO2-eq/kg) | Source | Partial Emission (kg CO2-eq/kg) | Emission (kg CO2-eq/FU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite TPS-cassava bags | |||||

| Cassava starch | 0.71 | 1.03 | [26] | 0.726 | 3.63 |

| Glycerol | 0.23 | 2.00 | [34] | 0.460 | 2.3 |

| Beeswax | 0.02 | 0.41 | [35] | 0.008 | 0.04 |

| Citric acid (EEUU) | 0.01 | 19.32 | [26] | 0.193 | 0.965 |

| Span 80 | 0.01 | 4.00 | [26] | 0.020 | 0.1 |

| LDPE | 0.02 | 3.43 | [36] | 0.069 | 0.345 |

| Powered plantain leaves | 0.01 | 0.002 | [37] | 0.00002 | 0.0001 |

| Total carbon footprint/kg bag material | 1.476 | 7.38 | |||

| Composite TPS-cassava dishes | |||||

| Cassava starch | 0.322 | 1.03 | [26] | 0.94 | 195.52 |

| Glycerol | 0.086 | 2.00 | [34] | 0.488 | 101.50 |

| Beeswax | 0.032 | 0.41 | [35] | 0.037 | 3.76 |

| Citric acid (EEUU) | 0.010 | 2.1 | [26] | 0.063 | 13.10 |

| Span 80 | 0.032 | 4.00 | [26] | 0.364 | 75.71 |

| carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) | 0.021 | 3.40 | [26] | 0.207 | 43.06 |

| Powered plantain leaves | 0.129 | 0.002 | [37] | 0.00074 | 0.15 |

| Total carbon footprint/kg dish material | 2.099 | 436.60 | |||

| Resin | Factor of Emission (kg CO2-eq/kg) | Emission (kg CO2-eq/FU) |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethene (PE) | 3.43 | 17.15 |

| Polypropylene (PP) | 4.72 | 23.60 |

| Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) | 5.42 | 27.10 |

| Polylactic acid (PLA) | 1.8–3.3 | 12.75 |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) | 2.5–4.5 | 17.50 |

| Stage | Activity to Perform | Equipment | Energy Consumption (kW/h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite TPS-cassava bags | |||

| Raw Material Reception | Weight validation of raw materials | Industrial floor scale | 0.500 |

| Material Conditioning | Starch drying | 12-tray dehydrator | 2.240 |

| Starch pulverization | Pulverizer mill | 3.000 | |

| Starch sieving ≤400 µm | Vibratory sieve | 3.500 | |

| Starch moisture validation | Thermogravimetric balance | 1.000 | |

| Mixing | Material mixing | Mixer | 2.240 |

| Pelletizing | Pellet production | Pelletizing extruder | 5.000 |

| Sheet Extrusion | Extrusion | Sheet extruder | 5.000 |

| Bag Precut | Precutting rolls | Bag precutter | 1.500 |

| Estimated total energy consumption for biocomposite bag production | 23.980 | ||

| Composite TPS-cassava dishes | |||

| Raw Material Reception | Weight validation of raw materials | Industrial floor scale | 0.500 |

| Material Conditioning | Starch/plantain leaves drying | 12-tray dehydrator | 4.480 |

| Starch/plantain leaves pulverization | Pulverizer mill | 6.000 | |

| Starch/plantain leaves sieving ≤100 µm | Vibratory sieve | 7.000 | |

| Mixing | Material melting/mixing | Mixer | 6.250 |

| Pressing | Material pressing | Hydraulic press | 5.000 |

| Estimated total energy consumption for biocomposite dish production | 29.230 | ||

| Energy Source | CO2 Emission Factor (kg CO2/kWh) * | Total CO2 Emissions per Hour (Bags) (kg CO2/h) | Emissions per FU (Bags) (kg CO2/FU) | Total CO2 Emissions per Hour (Dishes) (kg CO2/h) | Emissions per FU (Dishes) (kg CO2/FU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydropower | 0.004 | 0.096 | 0.024 | 0.117 | 1.218 |

| Wind | 0.011 | 0.264 | 0.066 | 0.321 | 3.344 |

| Solar | 0.041 | 0.983 | 0.246 | 1.200 | 12.50 |

| Natural Gas | 0.93 | 22.301 | 5.575 | 27.184 | 283.16 |

| Petroleum | 1.17 | 28.057 | 7.014 | 34.200 | 356.25 |

| Coal | 1.689 | 40.502 | 10.126 | 49.400 | 514.58 |

| Transport Mode | Fuel Type | Emission Factor (kg CO2/ton-km) * | Distance (km) | Mass Transported—Raw Materials (Tons) | Emissions—Raw Materials Transported (kg CO2) | Emissions per FU (kg CO2/FU) | Mass Transported—LDPE Bags (Tons) | Emissions-LDPE Bags (kg CO2) | Emissions per FU—LDPE Bags (kg CO2/FU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Transport (Bogotá → Leticia) | Jet Fuel | 0.602 | 1095 | 2.8 | 1845.732 (bags) | 0.923 (bags) | 10 | 6591.9 | 3.30 |

| 1.81 | 1193.134 (dishes) | 24.82 (dishes) | |||||||

| River Transport (Leticia → Puerto Nariño) | Gasoline | 0.031 | 80 | 2.8 | 6.944 (bags) | 0.0035 (bags) | 10 | 24.8 | 0.01 |

| 1.81 | 4.488 (dishes) | 0.093 (dishes) | |||||||

| Composite TPS-cassava packages | Total Emissions (kg CO2) | 1852.676 (bags) | 0.926 (bags) | Total emissions (kg CO2) | 6616.7 | 3.31 | |||

| 1197.623 (dishes) | 24.91 (8dishes) | ||||||||

| Material Type | Annual Bag Consumption (Units) | Weight per Bag (kg) | Non-Biodegradable Content (%) | Non-Biodegradable Residues (kg) | Degradation Rate of Non-Biodegradable Residues (kg/Year) [32] | Non-Biodegradable Residues Remaining After a Year (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite TPS-cassava Bags | 1,000,000 | 0.015 | 2% | 300 | 0.005 | 298.5 |

| Conventional LDPE Bags | 1,000,000 | 0.010 | 100% | 10,000 | 0.005 | 9950 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garavito, J.; Posada, N.C.; Peña-Venegas, C.P.; Castellanos, D.A. Carbon Footprint of Plastic Bags and Polystyrene Dishes vs. Starch-Based Biodegradable Packaging in Amazonian Settlements. Polymers 2025, 17, 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243242

Garavito J, Posada NC, Peña-Venegas CP, Castellanos DA. Carbon Footprint of Plastic Bags and Polystyrene Dishes vs. Starch-Based Biodegradable Packaging in Amazonian Settlements. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243242

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaravito, Johanna, Néstor C. Posada, Clara P. Peña-Venegas, and Diego A. Castellanos. 2025. "Carbon Footprint of Plastic Bags and Polystyrene Dishes vs. Starch-Based Biodegradable Packaging in Amazonian Settlements" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243242

APA StyleGaravito, J., Posada, N. C., Peña-Venegas, C. P., & Castellanos, D. A. (2025). Carbon Footprint of Plastic Bags and Polystyrene Dishes vs. Starch-Based Biodegradable Packaging in Amazonian Settlements. Polymers, 17(24), 3242. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243242