Tailoring the Properties of Soy Protein-Based Bioplastics via Plasticizer Composition and Extrusion Temperature for Controlled Iron Release

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of the Bioplastic Matrices

2.3. Thermal Stability of Blends

2.4. Characterization of the Bioplastic Matrices

2.4.1. Thermal Stability of Bioplastic Matrices

2.4.2. Structural and Morphological Characterization

2.4.3. Mechanical Properties

2.4.4. Water Uptake Capacity (WUC)

2.4.5. Iron Release in Water

2.4.6. Mold Resistance

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

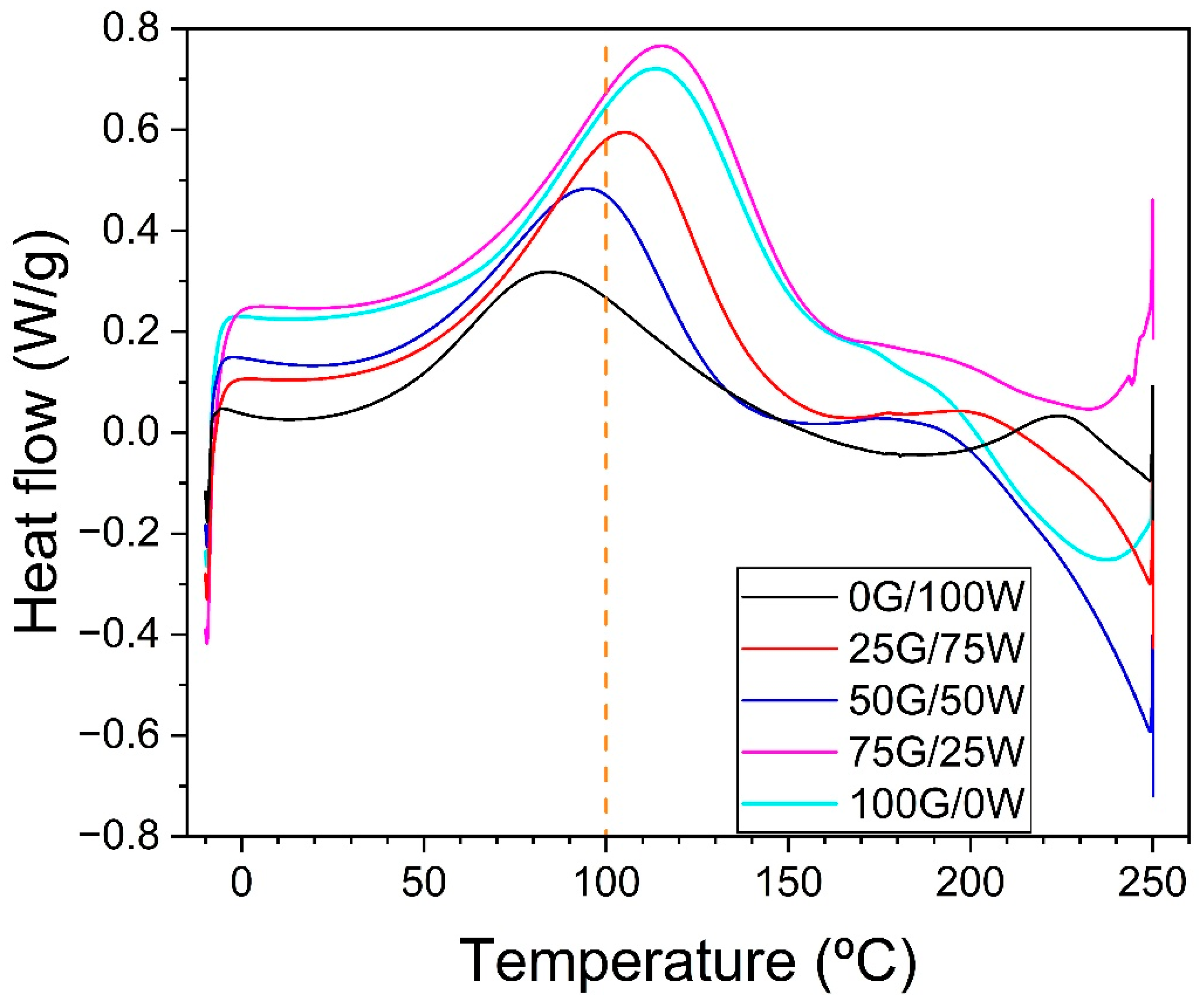

3.1. Thermal Stability of Blends

3.2. Characterization of the Bioplastic Matrices

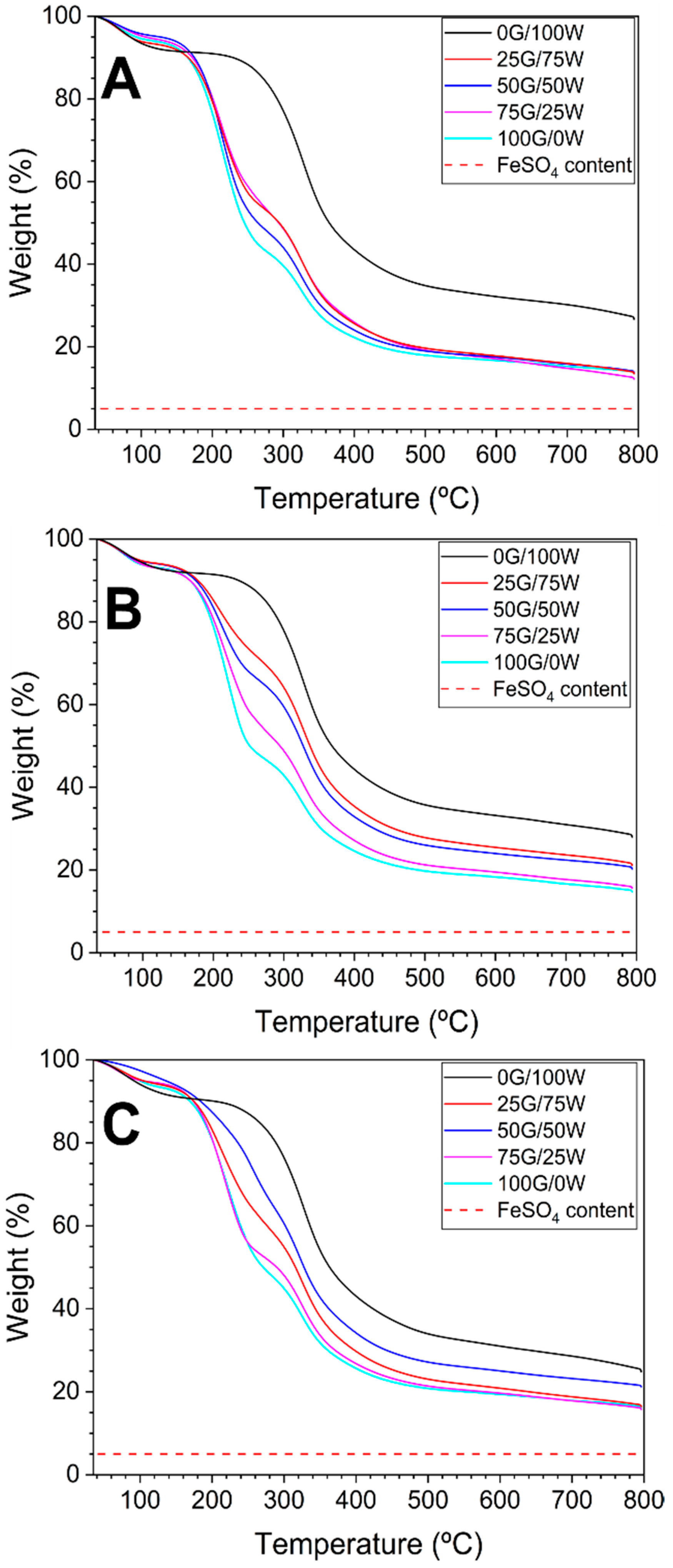

3.2.1. Thermal Stability of Bioplastic Matrices

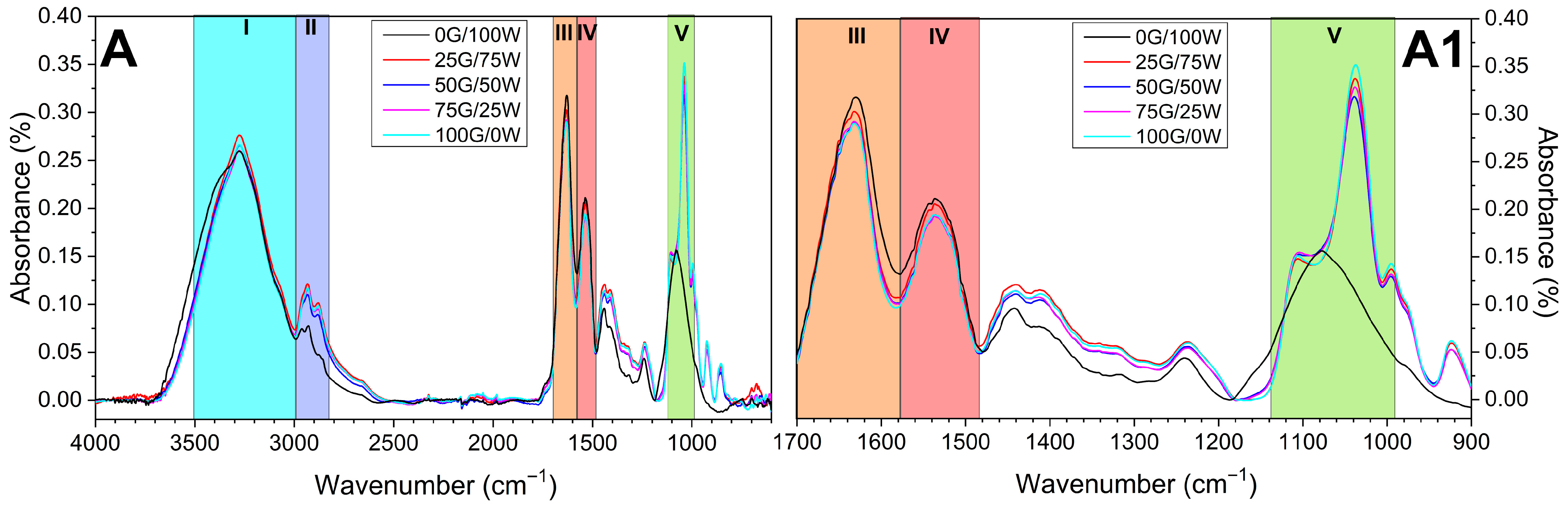

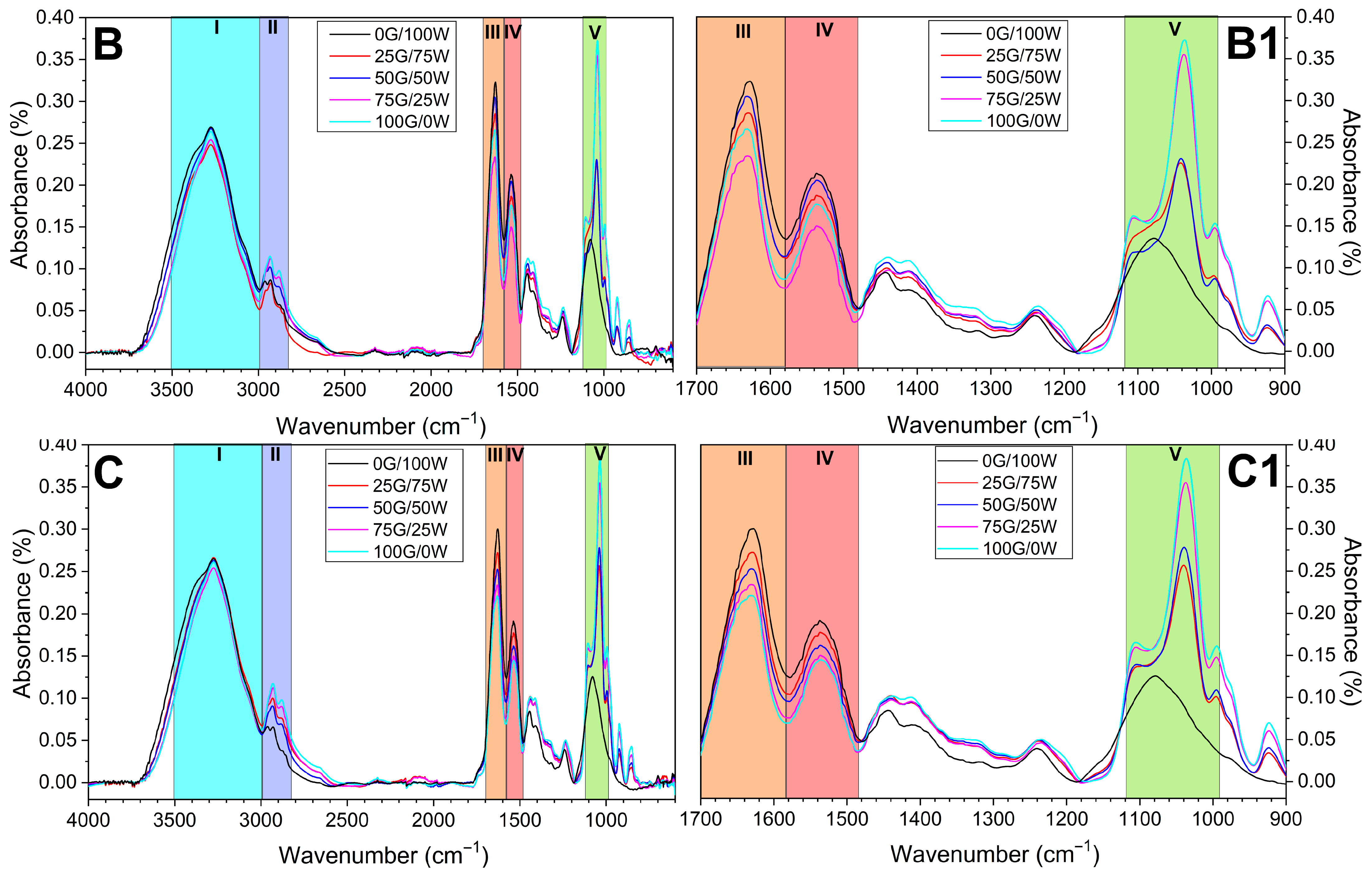

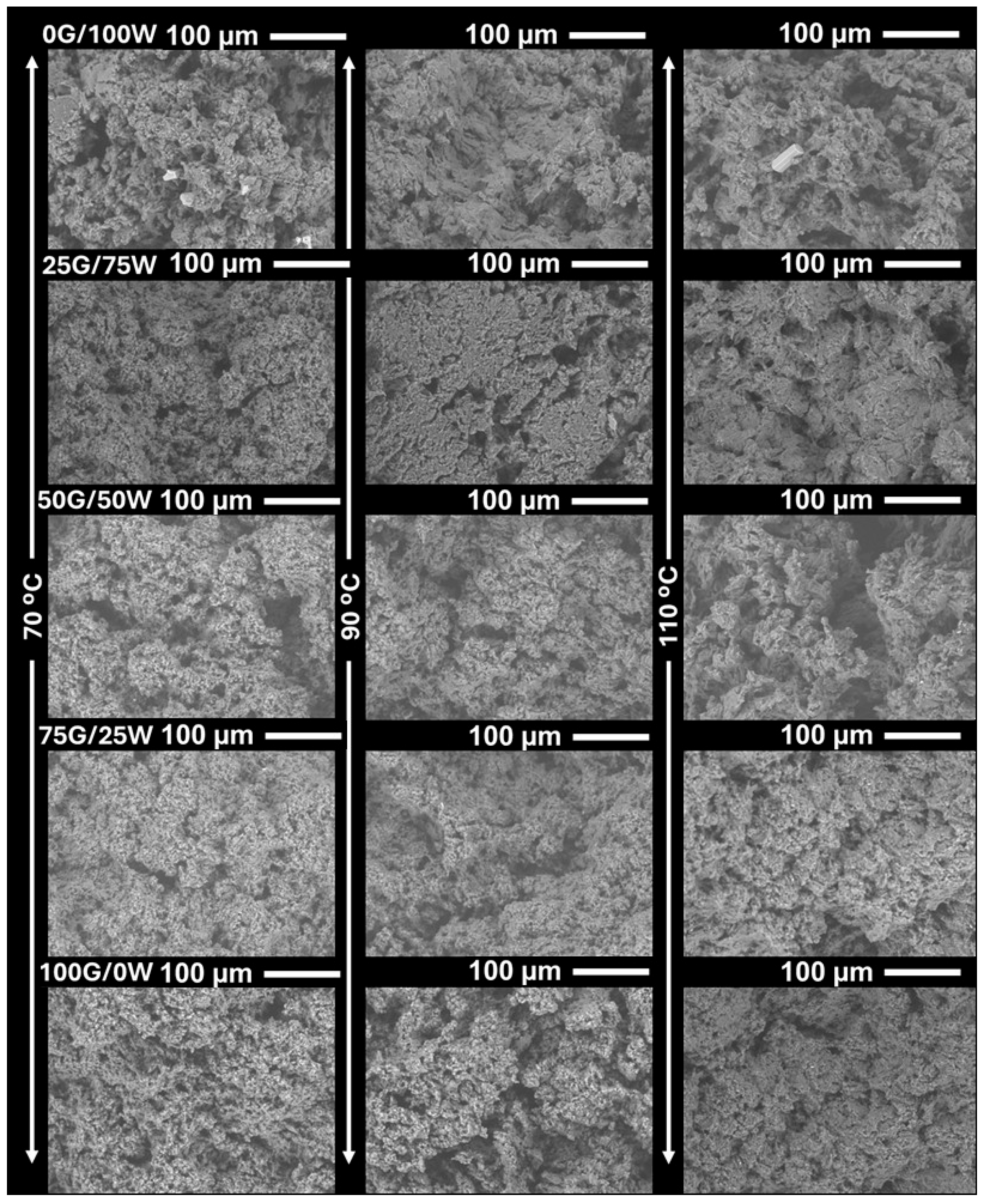

3.2.2. Structural and Morphological Characterization

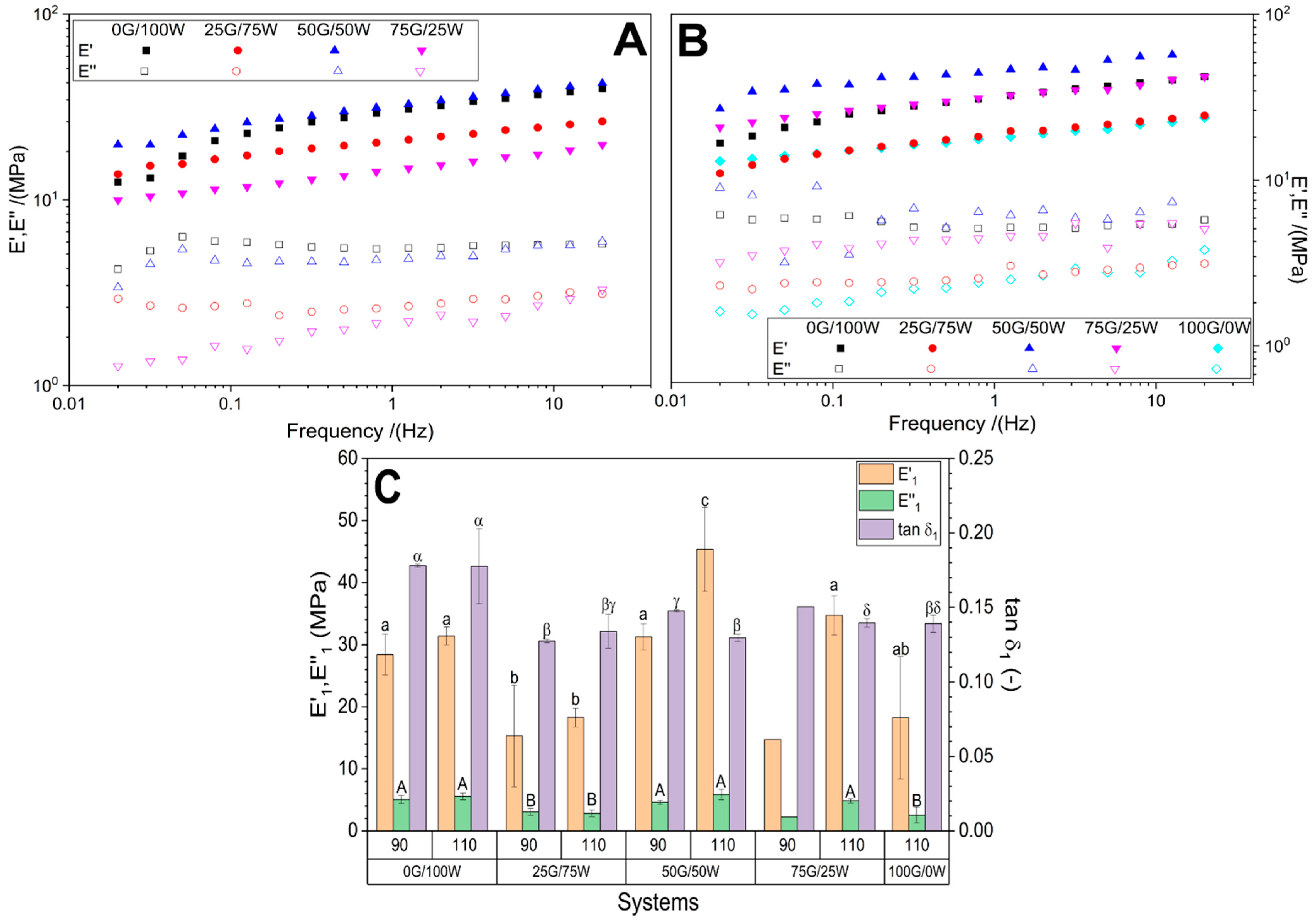

3.2.3. Mechanical Properties

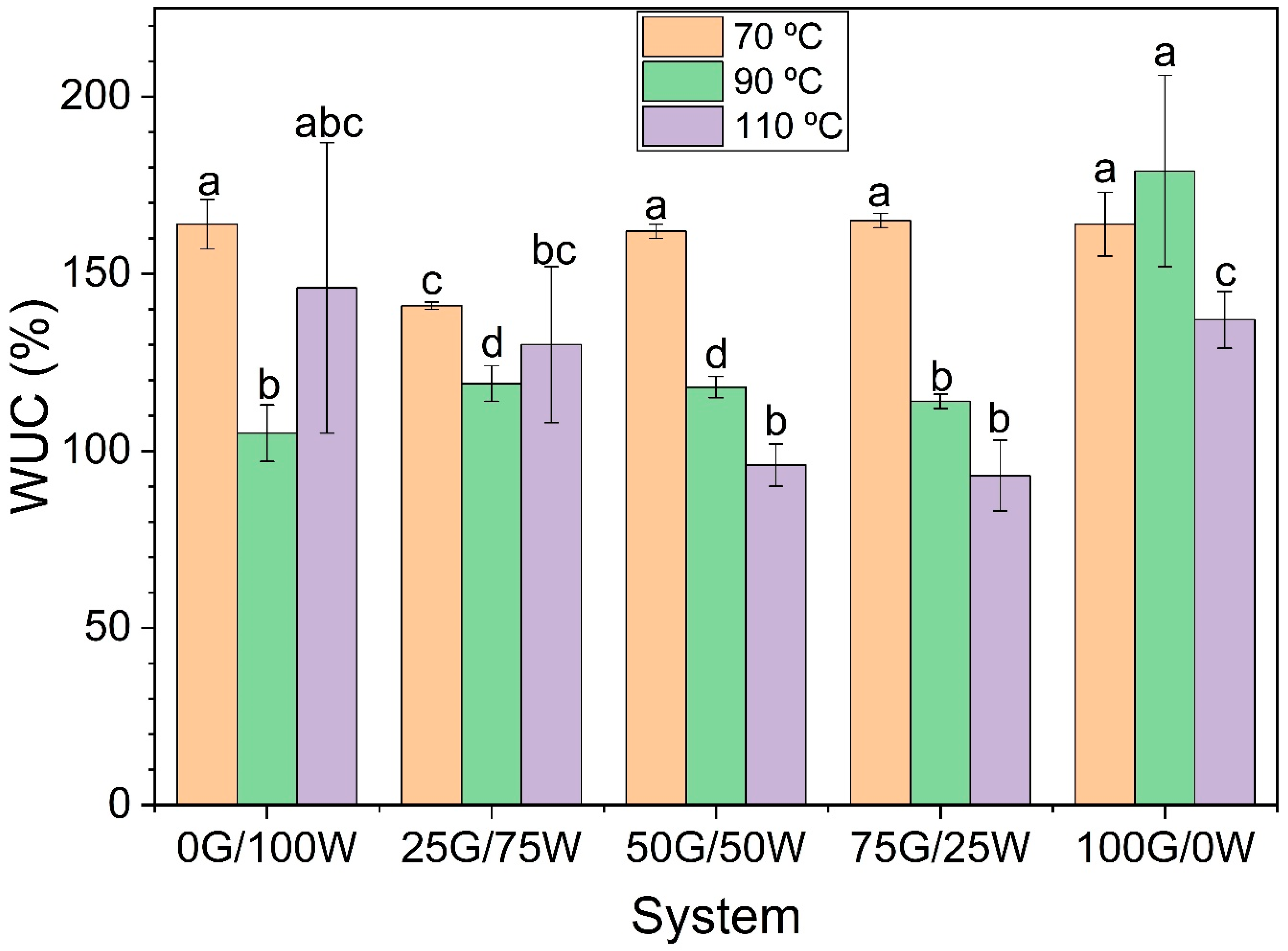

3.2.4. WUC

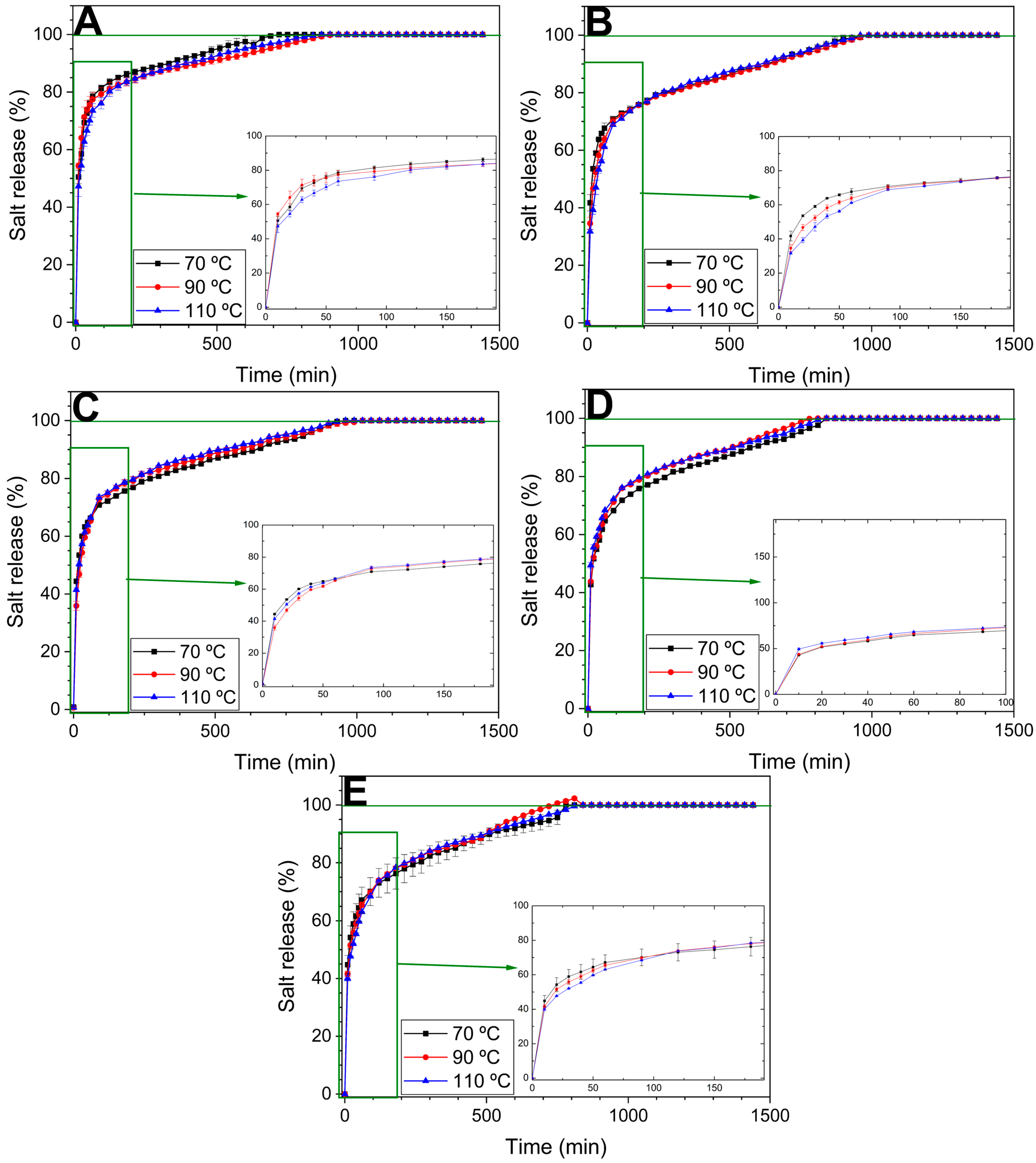

3.2.5. Iron Release in Water

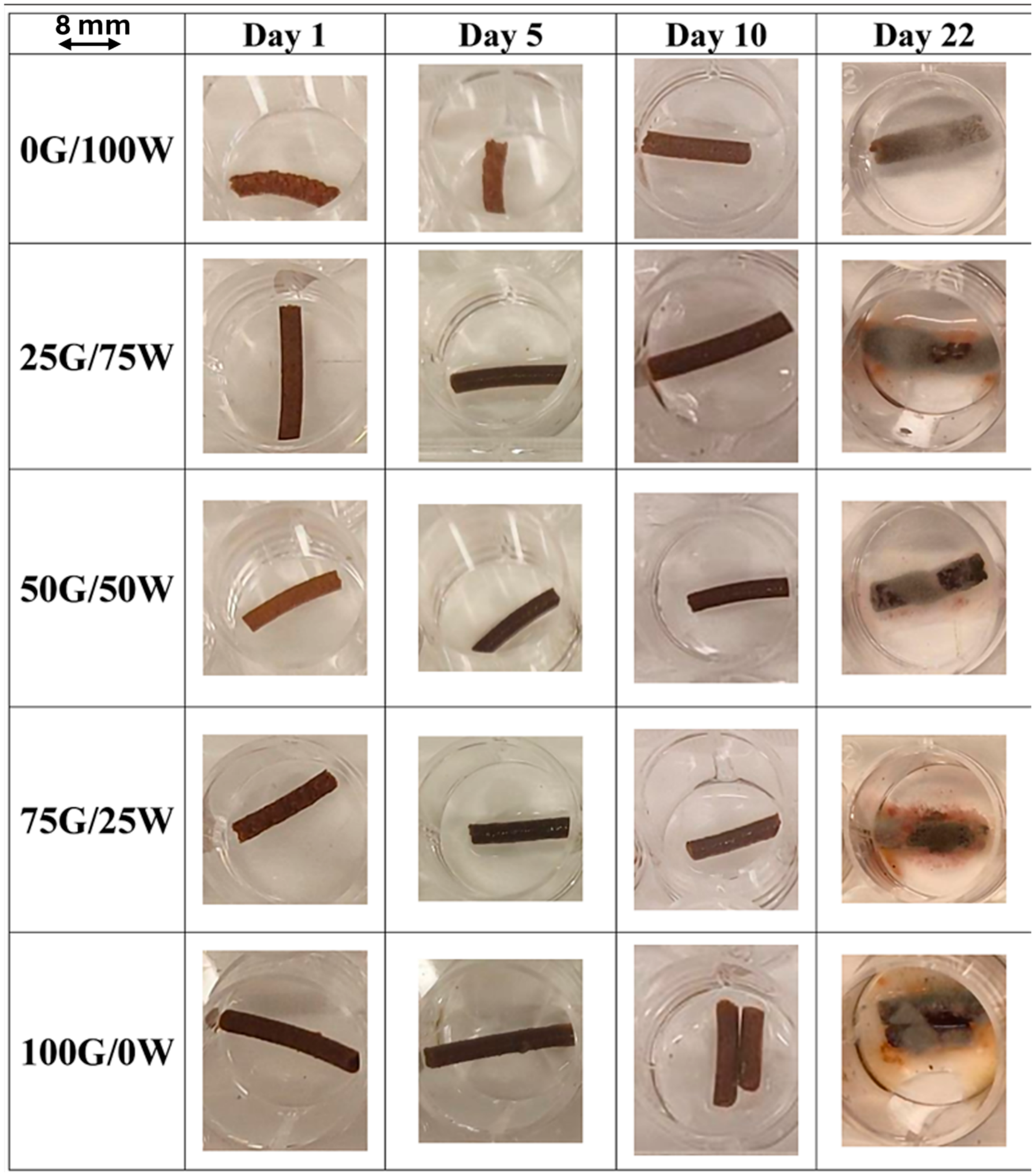

3.2.6. Mold Resistance

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Bioplastics Bioplastics Market Data 2019. Global Production Capacities of Bioplastic 2019–2024. Eur. Bioplastic 2019, 9, 1–14. Available online: https://docs.european-bioplastics.org/publications/market_data/2019/Report_Bioplastics_Market_Data_2019.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Kibria, M.d.G.; Masuk, N.I.; Safayet, R.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Mourshed, M. Plastic Waste: Challenges and Opportunities to Mitigate Pollution and Effective Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2023, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roijen, E.C.; Miller, S.A. A Review of Bioplastics at End-of-Life: Linking Experimental Biodegradation Studies and Life Cycle Impact Assessments. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, P.; Agate, S.; Velev, O.D.; Lucia, L.; Pal, L. A Critical Review of the Performance and Soil Biodegradability Profiles of Biobased Natural and Chemically Synthesized Polymers in Industrial Applications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 2071–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, Y.K.; Mishra, A.K.; Lakshmayya, N.S.V.; Panda, J.; Thatoi, H.; Sarma, H.; Rustagi, S.; Baek, K.-H.; Mishra, B. Agro-Waste-Derived Bioplastics: Sustainable Innovations for a Circular Economy. Waste Biomass Valorization 2025, 16, 3331–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Agricultural Production Statistics 2010–2023; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Visco, A.; Scolaro, C.; Facchin, M.; Brahimi, S.; Belhamdi, H.; Gatto, V.; Beghetto, V. Agri-Food Wastes for Bioplastics: European Prospective on Possible Applications in Their Second Life for a Circular Economy. Polymers 2022, 14, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C. Production of Sustainable and Biodegradable Polymers from Agricultural Waste. Polymers 2020, 12, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayarathna, S.; Andersson, M.; Andersson, R. Recent Advances in Starch-Based Blends and Composites for Bioplastics Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Puyana, V.; Cuartero, P.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Martínez, I.; Romero, A. Physical Crosslinking of Pea Protein-Based Bioplastics: Effect of Heat and UV Treatments. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 32, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Espada, L.; Bengoechea, C.; Sandía, J.A.; Cordobés, F.; Guerrero, A. Development of Novel Soy-Protein-Based Superabsorbent Matrixes through the Addition of Salts. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, L.; Elhady, S.; Abdelkareem, A.; Fahim, I. Fabricating Starch-Based Bioplastic Reinforced with Bagasse for Food Packaging. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 2, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Castillo, E.; Felix, M.; Bengoechea, C.; Guerrero, A. Proteins from Agri-Food Industrial Biowastes or Co-Products and Their Applications as Green Materials. Foods 2021, 10, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, S.; Patra, B.R.; Patel, R.; Bakos, J.; Dalai, A.K. Innovations in Applications and Prospects of Bioplastics and Biopolymers: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoni, C.G.; Azeredo, H.M.C.; Mattos, B.D.; Beaumont, M.; Correa, D.S.; Rojas, O.J. The Food–Materials Nexus: Next Generation Bioplastics and Advanced Materials from Agri-Food Residues. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, K.T. Plant Nutrients and Soil Fertility Management. In Soils; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 129–159. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Criado, D.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Perez-Puyana, V.M.; Romero, A. Sustainable Packaging Solutions from Agri-Food Waste: An Overview. In Transforming Agriculture Residues for Sustainable Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Di Foggia, M.; Rosignoli, S.; Guerrero, A.; Rombolà, A.D.; Romero, A. Effect of Zinc and Protein Content in Different Barley Cultivars: Use of Controlled Release Matrices. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2023, 38, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, D.; Medina, Â.F.; Messa, L.L.; Souza, C.F.; Faez, R. Chitosan Spray-Dried Microcapsule and Microsphere as Fertilizer Host for Swellable—Controlled Release Materials. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 196, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertahi, S.; Ilsouk, M.; Zeroual, Y.; Oukarroum, A.; Barakat, A. Recent Trends in Organic Coating Based on Biopolymers and Biomass for Controlled and Slow Release Fertilizers. J. Control. Release 2021, 330, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikula, K.; Izydorczyk, G.; Skrzypczak, D.; Mironiuk, M.; Moustakas, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A.; Chojnacka, K. Controlled Release Micronutrient Fertilizers for Precision Agriculture—A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 712, 136365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejan, P.; Khadiran, T.; Abdullah, R.; Ahmad, N. Controlled Release Fertilizer: A Review on Developments, Applications and Potential in Agriculture. J. Control. Release 2021, 339, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubkowski, K. Environmental Impact of Fertilizer Use and Slow Release of Mineral Nutrients as a Response to This Challenge. Pol. J. Chem. Technol. 2016, 18, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashter, S.A. Processing Biodegradable Polymers. In Introduction to Bioplastics Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 179–209. [Google Scholar]

- Ribba, L.; Lorenzo, M.C.; Tupa, M.; Melaj, M.; Eisenberg, P.; Goyanes, S. Processing and Properties of Starch-Based Thermoplastic Matrix for Green Composites. In Green Composites; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 63–133. ISBN 978-981-15-9643-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gräfenhahn, M.; Ellwanger, F.; Karbstein, H.P.; Emin, M.A. Influence of Thermomechanical Stresses on Structural and Functional Changes of Highly Concentrated Protein Systems in Extrusion Processing. In Dispersity, Structure and Phase Changes of Proteins and Bio Agglomerates in Biotechnological Processes; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 313–350. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, C.J.R.; van den Berg, L.E. Extrusion Processing and Properties of Protein-Based Thermoplastics. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2010, 295, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullsten, N.H.; Cho, S.W.; Spencer, G.; Gallstedt, M.; Johansson, E.; Hedenqvist, M.S. Properties of Extruded Vital Wheat Gluten Sheets with Sodium Hydroxide and Salicylic Acid. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redl, A.; Guilbert, S.; Morel, M.-H. Heat and Shear Mediated Polymerisation of Plasticized Wheat Gluten Protein upon Mixing. J. Cereal Sci. 2003, 38, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Izquierdo, V.M.; Krochta, J.M. Thermoplastic Processing of Proteins for Film Formation—A Review. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, R30–R39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommet, M.; Redl, A.; Morel, M.; Domenek, S.; Guilbert, S. Thermoplastic Processing of Protein-based Bioplastics: Chemical Engineering Aspects of Mixing, Extrusion and Hot Molding. Macromol. Symp. 2003, 197, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, E.; Podhaisky, H.; Ely, D.; Thommes, M. Residence Time Modeling of Hot Melt Extrusion Processes. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013, 85, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.P.; Escribà-Gelonch, M.; Hessel, V.; Coad, B.R. A Review of the Current and Future Prospects for Producing Bioplastic Films Made from Starch and Chitosan. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 1750–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abotbina, W.; Sapuan, S.M.; Sultan, M.T.H.; Alkbir, M.F.M.; Ilyas, R.A. Development and Characterization of Cornstarch-Based Bioplastics Packaging Film Using a Combination of Different Plasticizers. Polymers 2021, 13, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.G.A.; da Silva, M.A.; dos Santos, L.O.; Beppu, M.M. Natural-Based Plasticizers and Biopolymer Films: A Review. Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montilla-Buitrago, C.E.; Gómez-López, R.A.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Serna-Cock, L.; Villada-Castillo, H.S. Effect of Plasticizers on Properties, Retrogradation, and Processing of Extrusion-Obtained Thermoplastic Starch: A Review. Starch-Stärke 2021, 73, 2100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Perez-Puyana, V.; Cordobés, F.; Romero, A.; Guerrero, A. Development of Soy Protein-Based Matrices Containing Zinc as Micronutrient for Horticulture. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 121, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-González, M.; Castro-Criado, D.; Felix, M.; Romero, A. Evaluation of Rice Bran Varieties and Heat Treatment for the Development of Protein/Starch-Based Bioplastics via Injection Molding. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D570-98; Standard Test Method for Water Absorption of Plastics. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2005.

- Zhao, C.; Shen, Y.; Du, C.; Zhou, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, X. Evaluation of Waterborne Coating for Controlled-Release Fertilizer Using Wurster Fluidized Bed. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 9644–9647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essawy, H.A.; Ghazy, M.B.M.; El-Hai, F.A.; Mohamed, M.F. Superabsorbent Hydrogels via Graft Polymerization of Acrylic Acid from Chitosan-Cellulose Hybrid and Their Potential in Controlled Release of Soil Nutrients. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 89, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, L.B.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Nejati, M.; Rasheed, F.; Prade, T.; Jiménez-Quero, A.; Sabino, M.A.; Capezza, A.J. Genipap Oil as a Natural Cross-Linker for Biodegradable and Low-Ecotoxicity Porous Absorbents via Reactive Extrusion. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 7642–7659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Guo, G.; Xiang, A.; Zhong, W.-H. Intermolecular Interactions and Microstructure of Glycerol-Plasticized Soy Protein Materials at Molecular and Nanometer Levels. Polym. Test. 2018, 67, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielichowski, K.; Njuguna, J.; Majka, T.M. Thermal Degradation of Polymeric Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; ISBN 9780128230237. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, B.S.; Hershenson, S. Practical Approaches to Protein Formulation Development. In Rational Design of Stable Protein Formulations: Theory and Practice; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- de Caro, P.; Bandres, M.; Urrutigoïty, M.; Cecutti, C.; Thiebaud-Roux, S. Recent Progress in Synthesis of Glycerol Carbonate and Evaluation of Its Plasticizing Properties. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almazrouei, M.; Adeyemi, I.; Janajreh, I. Thermogravimetric Assessment of the Thermal Degradation during Combustion of Crude and Pure Glycerol. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022, 12, 4403–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiak, E.; Lenart, A.; Debeaufort, F. How Glycerol and Water Contents Affect the Structural and Functional Properties of Starch-Based Edible Films. Polymers 2018, 10, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Nirmal, N.P.; Danish, M.; Chuprom, J.; Jafarzedeh, S. Characterisation of Composite Films Fabricated from Collagen/Chitosan and Collagen/Soy Protein Isolate for Food Packaging Applications. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 82191–82204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Chi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xia, N.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X. Changes in Properties of Soy Protein Isolate Edible Films Stored at Different Temperatures: Studies on Water and Glycerol Migration. Foods 2021, 10, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Türker-Kaya, S.; Huck, C. A Review of Mid-Infrared and Near-Infrared Imaging: Principles, Concepts and Applications in Plant Tissue Analysis. Molecules 2017, 22, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, L.; Wei, D.; Li, Y.; Sui, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, D. Effect of Secondary Structure Determined by FTIR Spectra on Surface Hydrophobicity of Soybean Protein Isolate. Procedia Eng. 2011, 15, 4819–4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, P. Soy Protein Isolate and Glycerol Hydrogen Bonding Using Two-Dimensional Correlation (2D-COS) Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR FT-IR) Spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 2017, 71, 2437–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Liu, H.; Yu, L.; Duan, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, F.; Shao, Z.; Shi, K.; Lin, X. How Water Acting as Both Blowing Agent and Plasticizer Affect on Starch-Based Foam. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 134, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Jiang, S.; Chen, F.; Li, Z.; Ma, L.; Song, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Yu, L. Fabrication, Evaluation Methodologies and Models of Slow-Release Fertilizers: A Review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 192, 116075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System | SPI (wt%) | FeSO4·7H2O (wt%) | W (wt%) | Gly (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100G/0W | 47.50 | 5.00 | 0 | 47.50 |

| 75G/25W | 35.63 | 11.87 | ||

| 50G/50W | 23.75 | 23.75 | ||

| 25G/75W | 11.87 | 35.63 | ||

| 0G/100W | 47.50 | 0 |

| 70 °C | 90 °C | 110 °C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0G/100W | 8.3 | 6.5 | 6.9 |

| 25G/75W | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.3 |

| 50G/50W | 6.3 | 5.9 | 6.3 |

| 75G/25W | 7.1 | 7.4 | 7.1 |

| 100G/0W | 7.7 | 7.1 | 7.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro-Criado, D.; Capezza, A.J.; Romero, A.; Jiménez-Rosado, M. Tailoring the Properties of Soy Protein-Based Bioplastics via Plasticizer Composition and Extrusion Temperature for Controlled Iron Release. Polymers 2025, 17, 3209. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233209

Castro-Criado D, Capezza AJ, Romero A, Jiménez-Rosado M. Tailoring the Properties of Soy Protein-Based Bioplastics via Plasticizer Composition and Extrusion Temperature for Controlled Iron Release. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3209. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233209

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro-Criado, Daniel, Antonio J. Capezza, Alberto Romero, and Mercedes Jiménez-Rosado. 2025. "Tailoring the Properties of Soy Protein-Based Bioplastics via Plasticizer Composition and Extrusion Temperature for Controlled Iron Release" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3209. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233209

APA StyleCastro-Criado, D., Capezza, A. J., Romero, A., & Jiménez-Rosado, M. (2025). Tailoring the Properties of Soy Protein-Based Bioplastics via Plasticizer Composition and Extrusion Temperature for Controlled Iron Release. Polymers, 17(23), 3209. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233209