New Insights on Fatigue Crack Growth of Reinforced Natural Rubber

Abstract

1. Introduction

Evaluation of Crack Growth Using Fracture Mechanics

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Crack Growth Measurements

2.3. Evaluation Procedure of Crack Growth Measurements

2.3.1. Calculating Tearing Energy

2.3.2. Calculating Crack Growth Rate

3. Results

3.1. Stress–Strain Curves, Peak Stress, and Mechanical Hysteresis

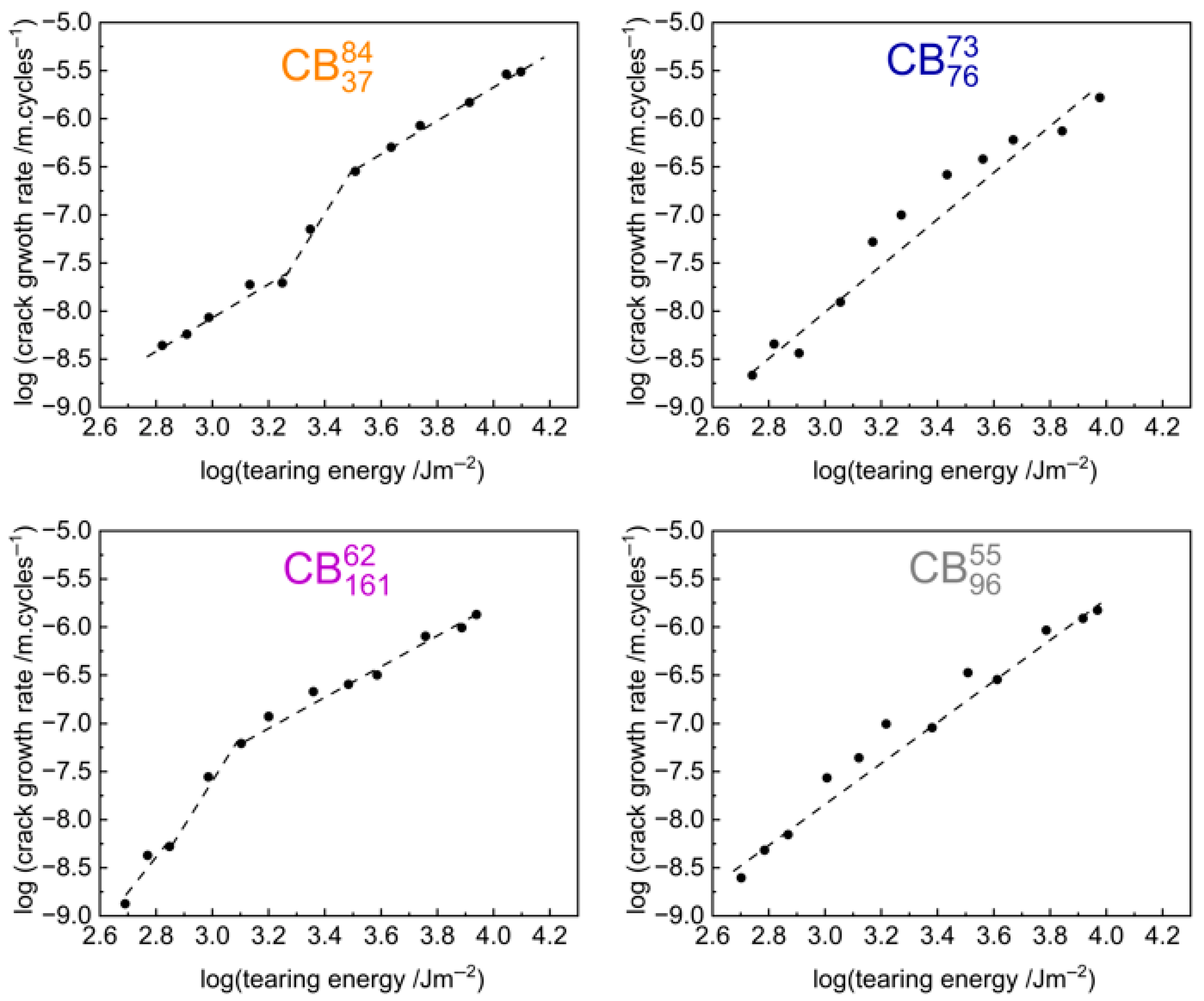

3.2. Fatigue Crack Growth Rate

4. Discussion

4.1. Possible Explanations of Step Change

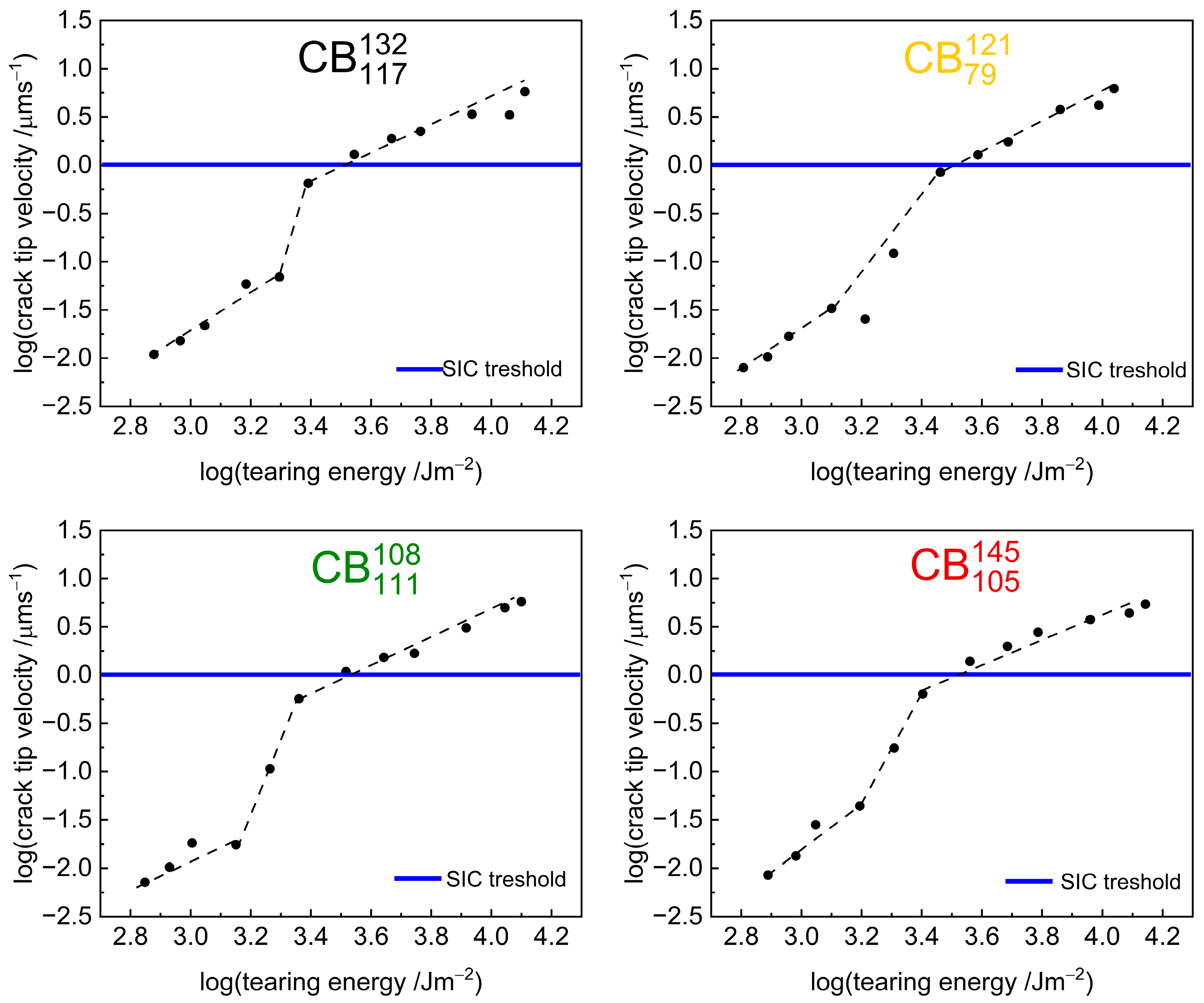

4.2. Most Likely Explanation of Step Change: Strain-Induced Crystallisation Effects

- Above the tearing energy, , the crack growth rate curves converge because the crack tip velocity exceeds the characteristic time needed for strain-induced crystallisation. Consequently, strain-induced crystallisation is suppressed and does not affect crack growth. The tested carbon black compounds, therefore, exhibit similar crack growth resistance, potentially influenced by mechanisms like hysteresis and crack tip blunting from the inclusion of carbon black.

- Below the tearing energy, , the distinction in the crack growth rates among the different carbon black compounds could be attributed to strain-induced crystallisation effects. Below the tearing energy, , the crack tip velocity is slow enough that the high-structure carbon black compounds form crystals to a more appreciable level to enhance crack growth resistance compared to the low-structure carbon black compounds. This explains the slower crack growth rate observed for these compounds at the low tearing energy and the observed step down. Previous publications [52,53] have shown that under quasistatic conditions, high-structure carbon black compounds have an earlier onset of crystallisation and achieve higher levels of crystallinity at similar strain levels compared to low-structure carbon black compounds.

Evidence to Support the Strain-Induced Crystallisation Effect Hypothesis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gent, A.N. Engineering with Rubber: How to Design Rubber Components; Hanser: Munich, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tunnicliffe, L.B. Fatigue Crack Growth of Carbon Black-Reinforced Natural Rubber. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2021, 94, 494–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, B.; Albohr, O.; Heinrich, G.; Ueba, H. Crack propagation in rubber-like materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2005, 17, 1072–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei-Manu, W.A.; Tunnicliffe, L.B.; Herd, C.R.; Akutagawa, K.; Stoček, R.; Busfield, J.J. Effect of carbon black properties on cut and chip wear of natural rubber. Wear 2025, 564, 205673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, W.; Fatemi, A. Factors that Affect the Fatigue Life of Rubber: A Literature Survey. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2004, 77, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadwell, S.; Merrill, R.A.; Sloman, C.M.; Yost, F. Dynamic Fatigue Life of Rubber. Ind. Eng. Chem. Anal. Ed. 1940, 12, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, P. Relation between hysteresis and the dynamic crack growth resistance of natural rubber. Int. J. Fract. 1973, 9, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellul, M.D. Chapter 6: Mechanical Fatigue. In Engineering with Rubber, How to Design Rubber Components; Hanser: Munich, Germany, 1992; pp. 159–201. [Google Scholar]

- Lake, G.J.; Thomas, A.G. Chapter 5: Strength. In Engineering with Rubber, How to Design Rubber Components; Hanser: Munich, Germany, 1992; pp. 119–153. [Google Scholar]

- Lake, G.; Lindley, P. Ozone cracking, flex cracking and fatigue of rubber. Rubber J. 1964, 146, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, A.A., VI. The phenomena of rupture and flow in solids. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1921, 221, 163–198. [Google Scholar]

- Rivlin, R.; Thomas, A. Rupture of rubber. I. Characteristic energy for tearing. J. Polym. Sci. 1953, 10, 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. Rupture of rubber. V. Cut growth in natural rubber vulcanizates. J. Polym. Sci. 1958, 31, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.G.; Stoček, R.; Mars, W.V. The Fatigue Threshold of Rubber and Its Characterization Using the Cutting. In Fatigue Crack Growth in Rubber Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 57–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lake, G.J.; Yeoh, O.H. Measurement of rubber cutting resistance in the absence of friction. Int. J. Fract. 1978, 14, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, A.K. Threshold Fracture of Elastomers. J. Macromol. Sci. Part C 1988, 28, 339–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, A.; Thomas, A. Tear behaviour of rubbers over a wide range of rates. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1981, 54, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busfield, J.; Tsunoda, K.; Davies, C.; Thomas, A. Contributions of Time Dependent and Cyclic Crack Growth to the Crack Growth Behavior of Non Strain-Crystallizing Elastomer. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2002, 75, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, A.; Sakumichi, N.; Morishita, Y.; Okumura, K.; Tsunoda, K.; Urayama, K.; Umeno, Y. Dynamic glass transition dramatically accelerates crack propagation in rubberlike solids. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2021, 5, 073608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3493; Standard Test Method for Carbon Black—Oil Absoprtion Number of Compressed Sample (COAN). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D6556; Standard Test Method for Carbon Black—Total and External Surface Area by Nitrogen Adsorption. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D2663; Standard Test Methods for Carbon Black—Dispersion in Rubber. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Stoček, R.; Stěnička, M.; Maloch, J. Determining Parametrical Functions Defining the Deformation of a Plane Strain Tensile Rubber Sample. In Fatigue Crack Growth in Rubber Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 286, pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom, J. Mechanics of Solid Polymers: Theory and Computational Modeling; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, I.; Thomas, A.; Busfield, J. Rate transitions in the fatigue crack growth of elastomers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 109, 1900–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busfield, J.; Ratsimba, C.; Thomas, A. Crack growth and strain induced anisotropy in carbon black filled natural rubber. J. Nat. Rubber 1997, 12, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Stoček, R.; Heinrich, G.; Gehde, M.; Kipscholl, R. Analysis of Dynamic Crack Propagation in Elastomers by Simultaneous Tensile—And Pure-Shear-Mode Testing. In Fracture Mechanics and Statistical Mechanics of Reinforced Elastomeric Blends; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 269–301. [Google Scholar]

- Donnet, J.-B.; Bansal, R.C.; Wang, M.-J. Carbon Black: Science and Technology; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A. Rupture of rubber. II. The strain concentration at an incision. J. Polym. Sci. 1955, 18, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greensmith, H. Rupture of rubber. IV. Tear properties of vulcanizates containing carbon black. J. Polym. Sci. 1956, 21, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei-Manu, W.; Herd, C.; Chowdhury, M.; Busfield, J.; Tunnicliffe, L. The influence of colloidal properties of carbon black on static and dynamic mechanical properties of natural rubber. Polymers 2022, 14, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cam, J.-B.; Huneau, B.; Verron, E.; Gornet, L. Mechanism of Fatigue Crack Growth in Carbon Black Filled Natural Rubber. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 5011–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanowski, T.; Marco, Y.; Le Saux, V.; Huneau, B.; Champy, C.; Charrier, P. Fatigue crack initiation around inclusions for a carbon black filled natural rubber: An analysis based on micro-tomography. In Constitutive Models for Rubber XI: Proceedings of the 11th European Conference on Constitutive Models for Rubber (ECCMR 2019), 25–27 June 2019, Nantes, France; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; McAuliffe, C.; Waisman, H.; Deodatis, G. Stochastic analysis of polymer composites rupture at large deformations modeled by a phase field method. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2016, 312, 596–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieppati, J.; Schrittesser, B.; Wondracek, A.; Robin, S.; Holzner, A.; Pinter, G. Impact of temperature on the fatigue and crack growth behavior of rubbers. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2018, 13, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, G.; Lindley, P. Cut growth and fatigue of rubbers. II. Experiments on a noncrystallizing rubber. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1964, 8, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamabe, J.; Yamamoto, R.; Amino, N.; Kakubo, T.; Maeda, N.; Fujikawa, M.; Koishi, M. Fatigue Crack Growth Behavir and Mechanistic Insights of Carbon Black-and Silica-Filled SBRs. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, J.; Mishra, N.; Dolui, T.; Ghosh, P.; Mukhopadhyay, R. Fatigue crack growth behavior and morphological analysis of natural rubber compounds with varying particle size and structure of carbon black. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2022, 62, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, W.; Fatemi, A. Fatigue crack nucleation and growth in filled natural rubber. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2003, 26, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüning, K.; Schneider, K.; Roth, S.V.; Heinrich, G. Kinetics of Strain-Induced Crystallization in Natural Rubber Studied by WAXD: Dynamic and Impact Tensile Experiments. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 7914–7919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gent, A.N.; Hindi, M. Effect of Oxygen on the Tear Strength of Elastomers. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1990, 63, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, C.M. Network Recovery from Uniaxial Extension: I. Elastic Equilibrium. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1989, 62, 863–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, C.M. Reinforcement of Elastomers. In Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rublon, P.; Huneau, B.; Verron, E.; Saintier, N.; Beurrot, S.; Leygue, A.; Mocuta, C.; Thiaudière, D.; Berghezan, D. Multiaxial deformation and strain-induced crystallization around a fatigue crack in natural rubber. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2014, 123, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saintier, N.; Cailletaud, G.; Piques, R. Cyclic loadings and crystallization of natural rubber: An explanation of fatigue crack propagation reinforcement under a positive loading ratio. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 583, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbour, R.; Fatemi, A.; Mars, W. Fatigue crack growth of filled rubber under constant and variable amplitude loading conditions. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2007, 30, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakulkaew, K.; Thomas, A.; Busfield, J. The effect of the rate of strain on tearing in rubber. Polym. Test. 2011, 30, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candau, N.; Chazeau, L.; Chenal, J.-M.; Gauthier, C.; Ferreira, J.; Munch, E.; Rochas, C. Characteristic-time of strain induced crystallization of crosslinked natural rubber. Polymer 2012, 53, 2540–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüning, K.; Schneider, K.; Roth, S.V.; Heinrich, G. Kinetics of strain-induced crystallization in natural rubber: A diffusion-controlled rate law. Polymer 2015, 72, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosaka, M.; Senoo, K.; Sato, K.; Noda, M.; Ohta, N. Detection of fast and slow crystallization processes in instantaneously-strained samples of cis-1,4-polyisoprene. Polymer 2012, 53, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acken, M.F.; Singer, W.E.; Davey, W. X-Ray Study of Rubber Structure. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1932, 24, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei-Manu, W.A.; Tunnicliffe, L.B.; Plagge, J.; Herd, C.R.; Akutagawa, K.; Pugno, N.M.; Busfield, J.J. Thermomechanical characterization of carbon black reinforced rubbers during rapid adiabatic straining. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 743146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei-Manu, W.A. Carbon Black Reinforcement of Tyre Tread Compounds. Ph.D. Thesis, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK, 2023. Available online: https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/94503 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Brüning, K.; Schneider, K.; Roth, S.V.; Heinrich, G. Strain-induced crystallization around a crack tip in natural rubber under dynamic load. Polymer 2013, 54, 6200–6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cam, J.-B.; Trubert, J.; Charlès, S.; Fernandes, R.; Lemos, V. Thermomechanical and calorimetric characterization of crack tip zones under large heterogeneous deformations, Part II: Full strain, calorimetric and strain-induced crystallinity fields at the crack tip of an unfilled natural rubber. Polymer 2025, 341, 129183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.; Danik, J. Effects of Temperature on Fatigue and Fracture. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1994, 67, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei-Manu, W.; Tunnicliffe, L.; Herd, C.; Akutagawa, K.; Kratina, O.; Stoček, R.; Busfield, J. Effect of Carbon Black on Heat Build-up and Energy Dissipation in Rubber Materials. In Advances in Polymer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.-J.; Wolff, S.; Tan, E.-H. Filler-elastomer interactions. Part VIII. The role of the distance between filler aggregates in the dynamic properties of filled vulcanizates. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1993, 66, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medalia, A.I. Effect of carbon black on dynamic properties of rubber vulcanizates. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1978, 51, 437–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huneau, B.; Masquelier, I.; Marco, Y.; Le Saux, V.; Noizet, S.; Schiel, C.; Charrier, P. Fatigue Crack Initiation in a Carbon Black-Filled Natural Rubber. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2016, 89, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euchler, E.; Bernhardt, R.; Schneider, K.; Heinrich, G.; Wießner, S.; Tada, T. In situ dilatometry and X-ray microtomography study on the formation and growth of cavities in unfilled styrene-butadiene-rubber vulcanizates subjected to constrained tensile deformation. Polymer 2020, 187, 122086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cam, J.-B. Fast Evaluation and Comparison of the Energy Performances of Elastomers from Relative Energy Stored Identification under Mechanical Loadings. Polymers 2022, 14, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, J.R.; Mars, W.V. Finitely Scoped, High Reliability Fatigue Crack Growth Measurements. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2018, 91, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cam, J.-B.; Kyei-Manu, W.A.; Tayeb, A.; Albouy, P.-A.; Busfield, J.J. Strain-induced crystallisation of reinforced elastomers using surface calorimetry. Polym. Test. 2024, 131, 108341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ASTM Grade Name | Carbon Black/Adopted Compound Name | Compound Dispersion Index | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NA | 132 | 117 | 99.3 | |

| NA | 121 | 79 | 98.8 | |

| N234 | 108 | 111 | 99.4 | |

| NA | 105 | 145 | 98.8 | |

| N550 | 84 | 37 | 98.7 | |

| N326 | 73 | 76 | 98.0 | |

| NA | 62 | 161 | 81.5 | |

| NA | 55 | 96 | 90.2 | |

| NA | Unfilled NR | NA | NA | NA |

| Target Crosshead Displacement/mm | Estimated Percentage Strain Level | Total Number of Cycles/1000 Cycles | Test Frequency/Hz |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.00 | 15 | 200 (400) | 4 |

| 2.25 | 17 | 200 (400) | 4 |

| 2.50 | 19 | 150 (300) | 4 |

| 3.00 | 23 | 75 (150) | 4 |

| 3.50 | 27 | 50 | 2.5 |

| 4.00 | 31 | 30 | 2.5 |

| 5.00 | 38 | 15 | 2.5 |

| 6.00 | 46 | 10 | 2.5 |

| 7.00 | 54 | 7.5 | 2.5 |

| 9.00 | 69 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| 11.00 | 85 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| 12.00 | 92 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Tested Compound | Average β-Parameter | Average log A Parameter | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specimen 1 | Specimen 2 | |||

| 2.50 ± 0.01 | −15.64 ± 0.06 | 0.92 | 0.91 | |

| 2.66 ± 0.11 | −16.02 ± 0.55 | 0.96 | 0.93 | |

| 2.76 ± 0.16 | −16.61 ± 0.61 | 0.92 | 0.92 | |

| 2.52 ± 0.00 | −15.75 ± 0.07 | 0.91 | 0.91 | |

| 2.38 ± 0.04 | −15.70 ± 0.68 | 0.98 | 0.97 | |

| 2.40 ± 0.02 | −15.30 ± 0.21 | 0.96 | 0.97 | |

| 2.20 ± 0.02 | −14.35 ± 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.92 | |

| 2.12 ± 0.01 | −14.18 ± 0.04 | 0.97 | 0.97 | |

| Unfilled NR | 2.62 ± 0.00 | −15.31 + 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Average | 2.46 | −15.43 | NA | NA |

| Phenomena | Explanation of Phenomena in Relation to FCG | Possible Explanation for Observed Step Change | Rebuttal for Why the Phenomena Does Not Explain the Observed Step Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cavitation |

|

|

|

| Mechanical Hysteresis and Crack Tip Heating |

|

|

| Description | Proposed Crack Growth Enhancement Level |

|---|---|

| Low (Strain level ≤ ~30%) ( ≤ 2500 ) | CB reinforcement effects (such as hysteresis, crack tip blunting, etc.) and SIC due to the strain amplification effect of CB |

| High (Strain level ≥ ~30%) ( 2500 ) | CB reinforcement effects (independent of CB grade) with no SIC effects |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kyei-Manu, W.A.; Tunnicliffe, L.B.; Herd, C.R.; Akutagawa, K.; Busfield, J.J.C. New Insights on Fatigue Crack Growth of Reinforced Natural Rubber. Polymers 2025, 17, 3200. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233200

Kyei-Manu WA, Tunnicliffe LB, Herd CR, Akutagawa K, Busfield JJC. New Insights on Fatigue Crack Growth of Reinforced Natural Rubber. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3200. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233200

Chicago/Turabian StyleKyei-Manu, William Amoako, Lewis B. Tunnicliffe, Charles R. Herd, Keizo Akutagawa, and James J. C. Busfield. 2025. "New Insights on Fatigue Crack Growth of Reinforced Natural Rubber" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3200. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233200

APA StyleKyei-Manu, W. A., Tunnicliffe, L. B., Herd, C. R., Akutagawa, K., & Busfield, J. J. C. (2025). New Insights on Fatigue Crack Growth of Reinforced Natural Rubber. Polymers, 17(23), 3200. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233200