3.2. Influence of Sliding Speed and Normal Load on Tribological Behavior of Seal Materials

Figure 3 depicts the change in specific wear rate and coefficient of friction (COF) for the commercial Duralast 4203 seal material (E1) over varying normal loads and sliding velocities. The trends indicate a distinct correlation between tribological performance and the operational parameters. The specific wear rate of E1 remained consistently low under all test conditions, proving the superior wear resistance of this thermoplastic polyurethane.

Figure 3a illustrates that the wear rate ranged from 2.3 × 10

−4 to 4.6 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm, exhibiting only moderate sensitivity to both speed and load. At 3 N, the wear rate remained relatively constant (2.7–2.9 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm) throughout all sliding velocities, signifying a steady micro-contact state and mild wear mostly governed by micro-abrasion [

25]. At 5 N, a substantial rise in wear rate was noted at 20 mm/s, attaining 4.6 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm, subsequently followed by a marked decline to 1.7 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 30 mm/s. This temporary increase is probably attributable to localized surface softening and micro-tearing resulting from cyclic loading and inadequate cooling at intermediate velocities. The subsequent decrease indicates that increased velocity caused smoother sliding, less adhesion, and enhanced clearance of loose debris. Under the maximum load of 10 N, the wear rate was moderate (2.3–3.1 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm), with a minor reduction at increased speeds. The stability under high load demonstrates Duralast 4203’s capacity to preserve structural integrity when subjected to compressive stress, attributed to its dense polyurethane matrix and superior elastic recovery [

19,

26]. The uniform wear resistance under all conditions highlights the material’s exceptional mechanical strength and surface durability.

Figure 3b illustrates the coefficient of friction (COF) with respect to sliding speed and load. The coefficient of friction (COF) significantly decreased at 3 N, decreasing from 0.40 at 10 mm/s to 0.10 at 30 mm/s. This decrease is ascribed to surface polishing and the gradual growth of a thin transfer film that stabilizes the contact interface and lowers adhesive interactions of seal material. At 5 N, the coefficients of friction (COF) were generally lower (0.23–0.15) and exhibited a comparable decreasing trend, indicating the synergistic effects of an increased actual contact area and diminished asperity interlocking at moderate loads. In contrast, at 10 N, the coefficient of friction (COF) exhibited a substantial rise with velocity, rising from 0.18 at 10 mm/s to 0.48 at 30 mm/s. The increase indicates that at higher load and velocity, frictional heating caused viscoelastic softening and partial surface deterioration, hence augmenting hysteresis losses and adhesion. The increased tangential distortion and micro-shearing of the polyurethane surface certainly led to this rise in friction [

26].

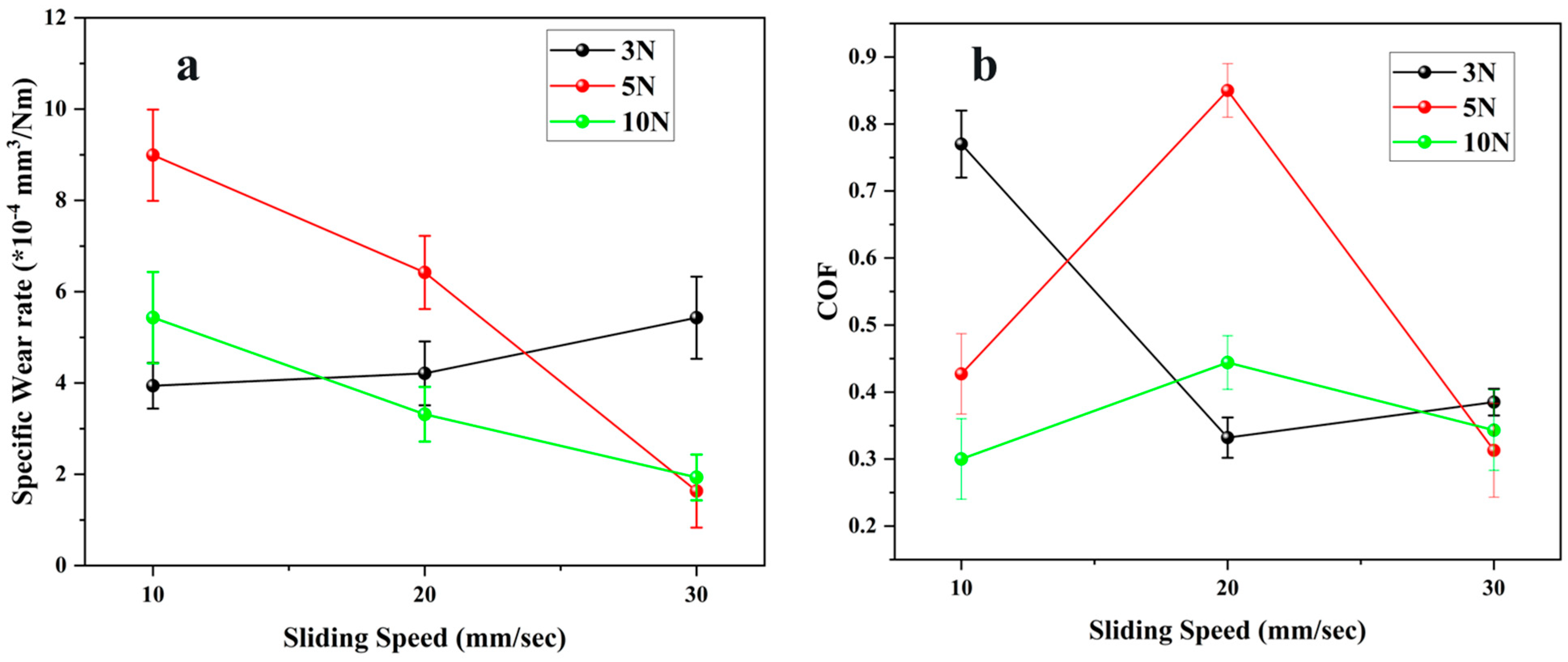

Figure 4 shows the specific wear rate and coefficient of friction (COF) of Duralast 4758 (E2) as a function of sliding speed at normal loads of 3, 5, and 10 N. The wear rate of E2 seal material exhibited significant sensitivity to load and speed, ranging from 1.6 × 10

−4 to 8.9 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm, as illustrated in

Figure 4a. At a minimal load of 3 N, the wear rate gradually increased with speed, rising from 3.94 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 10 mm/s to 5.43 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 30 mm/s, signifying a shift from moderate micro-abrasive wear to more pronounced adhesive or fatigue-assisted mechanisms at higher sliding velocities [

25]. At 5 N, the wear rate showed an unusual trend, reaching a higher wear rate of 8.99 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 10 mm/s, followed by a steep decline to 1.63 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 30 mm/s. The substantial wear at low speeds and moderate loads is attributed to extended asperity contact and insufficient recovery of the elastomer surface between strokes, leading to micro-tearing [

26]. As velocity escalated, the reduced contact duration and thermal softening facilitated smoother sliding and prevented material rupture. As velocity escalated, the wear rate consistently decreased from 5.43 × 10

−4 to 1.93 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at the maximum load of 10 N. This outcome indicates that, despite increased contact pressure, the self-lubricating properties of Duralast 4758 enabled the development of a thin transfer layer, thereby preventing significant wear. The COF behavior, illustrated in

Figure 4b, exhibited a more intricate relationship with load and velocity. At 3 N, the friction coefficient decreased significantly from 0.77 at 10 mm/s to 0.33 at 20 mm/s, thereafter, increasing somewhat to 0.39 at 30 mm/s. The initial drop relates to surface stabilization and partial polishing of the contact interface, whereas the later rise at elevated velocities is likely due to enhanced viscoelastic hysteresis and partial thermal softening of the near-surface layer. At 5 N, the coefficient of friction was 0.85 at 20 mm/s, indicating an unstable stick–slip phenomenon due to localized adhesion and interface thermal effects. At a higher speed of 30 mm/s, friction significantly reduced to 0.31, signifying a shift to a more consistent sliding condition with decreased adhesive effect. At 10 N, the coefficient of friction ranged from 0.30 to 0.44, indicating no significant instability. The moderate friction response under high load aligns with the improved self-lubricating properties of the seal material, which aids in mitigating direct asperity interlocking even at increased contact pressure [

27,

28].

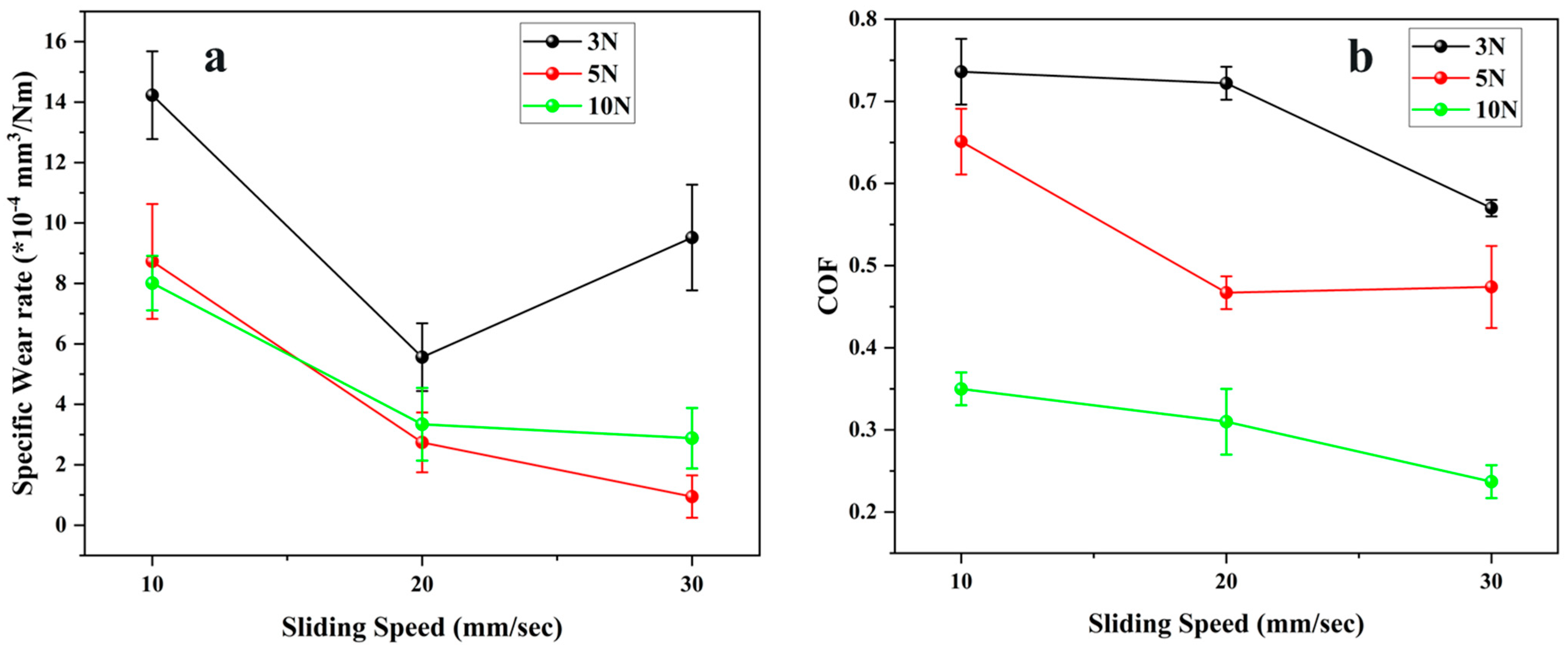

Figure 5 depicts the relationship between specific wear rate and coefficient of friction (COF) for the E3 seal material as a function of sliding speed across various applied loads. The wear rate of the E3 seal material varied from 1.45 × 10

−4 to 13.38 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm, demonstrating a distinct inverse correlation with sliding speed and applied stress, as illustrated in

Figure 5a. At 3 N, the specific wear rate decreased considerably from 13.38 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 10 mm/s to 5.38 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 30 mm/s, signifying a shift from severe to mild wear rate with increasing speed. This reduction can be due to reduced contact time and the potential development of a thin tribofilm on the counter pin that stabilized the interface at elevated sliding velocities [

12]. At 5 N, a comparable decreasing trend was noted, with wear diminishing from 10.66 × 10

−4 to 5.74 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm as sliding velocity increased. The increased contact pressure under moderate load possibly increased micro-abrasive plowing at low speed, whereas greater speed facilitated less friction and the removal of loose worn debris, hence reducing additional material loss [

29]. At the maximum load of 10 N, wear rate was relatively decreased throughout all velocities, declining from 3.26 × 10

−4 at 10 mm/s to 1.45 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 30 mm/s. The reduced wear under elevated loads indicates the onset of a mild wear regime, whereby the actual contact area has stabilized, and elastic deformation has absorbed most of the applied energy. The wear rate declines with increasing load and sliding speed, signifying that frictional heating may have helped localized softening, resulting in micro-contact and reduced material removal. The carbon black in E3 material likely improved stability by increasing crosslink density and the load-bearing capacity of the EPDM matrix. The COF data depicted in

Figure 5b demonstrates a more intricate pattern under differing test settings. At 3 N, the coefficient of friction reduced from 1.16 at 10 mm/s to 0.91 at 30 mm/s, signifying a decrease in adhesive interaction and an improvement of the contact interface. At 5 N, a comparable pattern was noted, with the coefficient of friction decreasing from 1.16 to 0.85 as velocity increased. The elevated friction at lower speeds results from significant adhesive and viscoelastic hysteresis impacts on the elastomer surface [

29]. The impacts reduce as the sliding velocity increases, and the contact becomes increasingly dynamic. At 10 N, the coefficient of friction (COF) initially increased from 0.31 at 10 mm/s to 0.67 at 20 mm/s, thereafter decreasing to 0.48 at 30 mm/s. The intermediate rise was due to the frictional heating and surface softness, which augment the actual contact area and adhesion. Conversely, at elevated speeds, a degree of self-polishing of the surface results in more stability during sliding. The irregularity observed across the 3, 5, 10 N is characteristic of elastomer tribology under dry reciprocating motion, where transfer-film formation, micro-scale thermal gradients, and dynamic filler–matrix interactions lead to abrupt changes in frictional response.

Figure 6 displays the specific wear rate and coefficient of friction (COF) of the E4 seal material under varying sliding velocities and normal loads. At a load of 3 N, the wear rate decreased from 36 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 10 mm/s to 14 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 30 mm/s, exhibiting a reduction of almost 60%. The diminished wear rate with increased speed is due to decreased contact duration per stroke and lower asperity interlocking, which collectively enable a smoother contact interface and a uniform tribofilm, resulting in a moderate wear regime [

17]. At 5 N, the wear rate initially dropped from 13 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm to 4.6 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm with increasing velocity, subsequently rising slightly to 7.3 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 30 mm/s. At 10 N, the wear rate exhibited a distinct trend, initially rising from 3.4 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 10 mm/s to 19 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 20 mm/s, followed by a decrease to 2.4 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 30 mm/s. This intermediate point signifies local fatigue or temporary micro-tearing resulting from cyclic stress concentration, which subsequently stabilizes as a tribofilm that develops at elevated speeds [

30]. The wear response demonstrates that E4 shifts from a severe wear regime at low speed and low load to a stable mild-wear regime under high speed and high load. The silica filler increases wear resistance by increasing the modulus and thermal stability of the EPDM matrix, while also facilitating a more uniform distribution of applied stress across the contact region. The COF values for E4 were consistently low, ranging from 0.03 to 0.20, as illustrated in

Figure 6b. At 3 N, friction exhibited a modest rise with speed, rising from 0.13 at 10 mm/s to 0.20 at 20 mm/s, and thereafter stabilizing at 0.20 at 30 mm/s. The marginal improvement is attributable to improved viscoelastic hysteresis and localized heating, which augment interfacial shear strength. At 5 N, the coefficient of friction diminished with increasing velocity, from 0.11 to 0.03, suggesting that elevated sliding speeds enhanced contact and mitigated adhesive friction. At 10 N, the coefficient of friction remained approximately constant at 0.04 ± 0.01, indicating that the surface attained a stable state with negligible additional deformation. The comprehensive tribological analysis indicates that the simultaneous increase in load and speed diminishes both wear and friction, resulting in a low-friction, low-wear regime at elevated loads and velocities. This trend results from the synergistic interaction between silica reinforcement and the elasticity of EPDM. The filler network bears the load, while the elastic matrix accommodates oscillating strain without significant surface failure [

31]. The inclusion of finely scattered silica facilitates heat dissipation and limits extensive adhesive connections, thus ensuring consistent frictional performance.

Figure 7 illustrates the variations in specific wear rate and coefficient of friction (COF) of the tested polymeric seal material under different combinations of sliding speed and normal load. At the lowest load of 3 N, the specific wear rate (

Figure 7a) decreases sharply from 1.42 × 10

−3 mm

3/Nm at 10 mm/s to 5.56 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 20 mm/s, before rising again to 9.52 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm at 30 mm/s. This behavior can be attributed to an initial reduction in the real contact area and adhesive of the polymer as speed increases, followed by mild thermal softening and unstable film formation at higher sliding velocities. At moderate and higher loads (5 N and 10 N), wear rate decreases consistently with increasing speed, attaining minimum values of 0.95 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm and 2.88 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm, respectively, at 30 mm/s. The reduction in wear at higher load and speed combinations is indicative of a transition toward a more stable tribo-film regime, wherein the elevated interfacial temperature enhances polymer softening and adhesion to the counter face, producing a self-protective layer that limits material removal and changes the contact from polymer-metal to polymer-polymer, reducing the wear rate [

16,

32].

A similar trend is reflected in the COF, which is displayed in

Figure 7b. At 3 N, the COF maintains a relatively high value throughout the tested speed range, indicating a predominant contribution from adhesive and plowing of the polymer surface. Increasing the load to 5 N lowers the COF from 0.65 to 0.47 as the sliding speed rises to 20 mm/s, beyond which it stabilizes, likely due to the formation of a uniform transfer film that mitigates direct contact with the countersurface. The lowest COF values were recorded at 10 N, highlighting the beneficial effect of higher normal pressure in promoting real contact homogenization and transfer-film continuity, which together reduce interfacial shear stress, reducing the friction between the polymer surface and the metal counter surface [

24]. It is important to note that elastomers do not exhibit linear scaling of friction or wear with load; instead, they transition between adhesive, abrasive, and hysteresis-dominated regimes as the interfacial temperature and real contact area fluctuate.

Although the results of this study demonstrate clear trends in friction, wear rate, and deformation under dry reciprocating contact, lubrication, hydraulic-fluid chemistry, temperature gradients, and hydrostatic pressure further complicate the tribological behavior of hydraulic seals in WEC systems. Pressurized hydraulic oil or water-based fluids reduce adhesive friction and suppress micro-abrasion by forming boundary or mixed lubrication films. Marine salinity and water ingress may accelerate hydrolysis in some polyurethane grades or modify filler-matrix interactions in EPDM-based compounds. Temperature changes affect viscoelastic response, while pressure affects real contact area and sealing stress. Therefore, whereas the dry-sliding ranking described here, E3 > E2 > E1 > E4 > E5, is indicative of low-lubrication and/or start-up conditions, its applicability under fully lubricated hydraulic operation may be quite different. The findings thus provide a baseline framework on which subsequent studies in fluid-immersed and marine environments can be built.

3.4. Wear Track Width Analysis of the Tested Seal Materials

Figure 9 displays optical images of the worn surfaces for all seal materials (E1–E5) tested at a load of 10 N and a sliding speed of 30 mm/s. The measured wear track width values are inscribed on each image, indicating the degree of surface deformation and removal of material during steady-state reciprocating motion. The commercial polyurethane seals (E1 and E2) exhibited the smallest wear tracks among all investigated seal materials, measuring around 518 µm and 1046 µm, respectively. The shallow and narrow track shows enhanced elastic recovery and resistance to applied loads [

30,

33]. This behavior is characteristic of high-modulus polyurethane systems, wherein extensive crosslinking and elevated Shore A hardness reduce plowing and limit viscoelastic creep under cyclic loading. Among the two commercial grades, E2 exhibited a marginally broader track while preserving a smooth and uniform surface morphology, in accordance with its balanced formulation that integrates durability with constrained self-lubrication. Alternatively, the EPDM-based seals (E3–E5) display increasingly broader wear tracks, which relate to reduced hardness. The E3 sample (EPDM + carbon black) exhibited a width of about 1391 µm, indicating more lateral deformation and micro-abrasive plowing due to the hard filler agglomerates. The E4 specimen (EPDM + silica) exhibited the largest track (~2849 µm), signifying considerable surface softening and partial rupture of the elastomeric matrix. This phenomenon results from localized stress concentration around inadequately bound silica aggregates, facilitating fracture initiation and debris formation [

34]. Surprisingly, the E5 formulation (EPDM + silica + DOS plasticizer) exhibited a reduced wear track (~2518 µm) compared to E4, despite its more pliable makeup. The use of dioctyl sebacate (DOS) enhanced molecular flexibility and stress relaxation, allowing the surface to deform uniformly instead of fracturing under cyclic load. The damping action governed by the plasticizer diminished the intensity of asperity cutting and restricted the spread of surface cracks [

35], correlating with its reduced wear rate and friction coefficient.

The quantitative profilometry parameters listed in

Table 4 support the surface features shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 and help correlate the measured topography with the dominant wear mechanisms. TPU samples (E1 and E2) showed the shallowest grooves (50–380 µm) and lowest roughness values (Ra = 3.2–6.8 µm), reflecting mild micro-abrasion and partial elastic recovery typical for high-modulus polyurethanes. In contrast, significantly deeper tracks were produced by EPDM-based materials (410–466 µm), along with higher roughness, reflecting stronger contributions from micro-plowing, filler–matrix debonding, and viscoelastic deformation. For E3, the deepest valleys amount to 466 µm, while the highest Sa values correspond to 15.3 µm. This sharp, V-shaped grooving is typical of carbon-black-induced plowing. Carbon black forms stiff agglomerates that act as micro-cutting asperities, which promote abrasive penetration and filler pull-out. Indeed, Zhou et al. [

7] have reported similar plowing behavior for carbon-black-filled EPDM under reciprocating motion. E4 showed steep-sided grooves and brittle ridge formation, consistent with silica-matrix debonding and crack initiation. Silica’s rigid, hydrophilic surface imparts higher stress concentration, leading to micro-crack propagation and fragmented debris. Literature on silica-filled EPDM similarly reports crack-dominated wear due to weak filler–rubber interfacial bonding [

33]. The smoother groove base and lower roughness (Ra = 8.9 µm) of E5 are attributed to DOS plasticizer improving chain mobility and reducing local rigidity. Plasticizer-induced softening allows the matrix to redistribute stresses during reciprocating loading, limiting crack formation and producing broader but shallower deformation zones. This is in line with previous findings that plasticized EPDM displays improved damping and reduced brittle wear [

30,

31].

It is important to remember that the wear mechanisms found in this study are for dry, room-temperature sliding and will change when the WEC is fully lubricated. Hydraulic fluids typically reduce adhesive friction and suppress micro-abrasion by forming boundary or mixed lubrication films, while fluid chemistry and marine salinity may influence polymer–filler interactions and accelerate hydrolytic or oxidative pathways in some formulations. Temperature gradients and operating pressure also alter viscoelastic response and real contact area during reciprocating motion. Therefore, the material ranking reported here (E3 > E2 > E1 > E4 > E5) is most representative of start-up phases, boundary-lubrication regimes, transient low-oil conditions, or periods of wave-induced load fluctuation, where dry or near-dry contact is more likely. Under fully flooded hydraulic operation, the absolute wear rates may change, but the dry-sliding results provide a necessary baseline for understanding intrinsic material behavior.

3.5. Statistical Analysis 2-Way ANOVA

A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized to statistically investigate the effects of normal load and sliding speed on the tribological characteristics of seal materials, at a 0.05 level of significance. The calculated F-ratios for both parameters were compared with the appropriate critical values (F

0.

05), and the relevance of each factor was determined by assessing whether the computed value exceeded the tabulated value. The analysis was conducted independently for each material, utilizing the average data from three experimental replicates of the coefficient of friction (COF) and specific wear rate (in

Supplementary Materials).

For E1 (Duralast 4203), the computed COF were Fₗ (2,18) = 180.84 > 3.55 and Fₛ (2,18) = 93.35 > 3.55, demonstrating that both load and speed substantially influenced friction. The specific wear rate showed Fₗ (2,18) = 88.54 > 3.55 and Fₛ (2,18) = 148.30 > 3.55, indicating a large variation in wear rate with respect to operating parameters. Consequently, both load and sliding velocity significantly influenced the tribological behavior of E1.

For E2 (Duralast 4758), the F-values for the COF were Fₗ (2,18) = 240.10 > 3.55 and Fₛ (2,18) = 196.60 > 3.55, indicating a significant influence of friction on both load and speed. The wear rate exhibited a notable difference, with Fₗ (2,18) = 957.06 > 5.14 and Fₛ (2,18) = 1135.60 > 5.14, demonstrating that both parameters significantly affected the wear rate of the seal material.

The ANOVA results for E3 (carbon-black-filled EPDM) indicated Fₗ (2,18) = 355.20 > 3.55 and Fₛ (2,18) = 54.70 > 3.55 for COF, suggesting substantial variation in both parameters. The specific wear rate indicates that Fₗ (2,18) = 1280.00 > 5.14 and Fₛ (2,18) = 1180.00 > 5.14, demonstrating that load and speed significantly influenced wear intensity, largely attributable to the reinforcing effect of carbon black and its enhancement of load-bearing capacity.

Surprisingly, E4 (silica- and plasticizer-modified EPDM) exhibited no significant variation in the COF, with Fₗ (2,18) = 0.39 < 3.55 and Fₛ (2,18) = 0.39 < 3.55, indicating consistent frictional performance under all testing conditions. The specific wear rate exhibited significant variability, with Fₗ (2,18) = 612.40 > 5.14 and Fₛ (2,18) = 548.70 > 5.14, indicating that wear remained responsive to loading and speed despite consistent COF. This indicates that the silica-plasticizer mixture enhanced surface damping but failed to avert subsurface fatigue wear.

For E5 (unfilled EPDM reference), both the coefficient of friction and wear exhibited statistically significant influence on load and velocity. The computed COF were Fₗ (2,18) = 412.60 > 3.55 and Fₛ (2,18) = 266.20 > 3.55, while the wear values were Fₗ (2,18) = 889.10 > 5.14 and Fₛ (2,18) = 942.50 > 5.14, demonstrating that the unreinforced material exhibited the highest sensitivity to external mechanical forces. The computed F-values for nearly all materials, except for the COF of E4, are above their critical thresholds at a 95% confidence level, indicating a significant difference among the applied load and sliding speed levels. The findings indicate that both friction and wear are influenced by interrelated mechanical and dynamic factors rather than by a single parameter [

36]. In materials comprising carbon black and polyurethane matrices, the interplay between load and speed generated significant synergistic effects attributable to thermal activation and interfacial densification. Conversely, the silica-modified EPDM exhibited a consistent COF yet demonstrated wear that was contingent upon applied stress. This indicates that internal viscoelastic losses constrained friction variation without diminishing surface fatigue. The ANOVA results quantitatively demonstrate that the tribological behavior of sealing materials is highly influenced by both load and sliding speed [

37], providing quantitative evidence of their interconnected effects on frictional energy dissipation and wear mechanisms.

3.6. Lifetime Estimation of Seal Materials

Based on the experimentally determined wear rate, the estimated service lifetimes were calculated for each seal material (E1–E5) using the equations given in

Section 2.6. The results are summarized in

Table 5.

The predicted lifetime varied from about 3.1 years (E5) to 6.2 years (E3) under the specified operating conditions. Although showing comparable coefficients of friction, E3 had the lowest wear rate (1.45 × 10

−4 mm

3/Nm) and hence the longest operational lifespan. In contrast, E5 demonstrated a comparatively higher wear rate, signifying accelerated material loss and lower durability. The findings indicate that wear rate has a more significant impact on service life than the frictional coefficient within the examined parameter range. Even slight decreases in the specific wear rate considerably prolonged the anticipated operational lifespan, aligning with previous tribological models in which the wear rate dictates volumetric material loss for longer periods [

22,

38]. The tribological stability of E3 results from superior load-bearing film development and enhanced interfacial cohesion during repeated sliding, while E4 and E5 suffered early material degradation, probably due to localized micro-fatigue and matrix fragmentation [

30]. These findings offer a practical quantitative approach for forecasting seal longevity or component replacement timelines based on empirical wear data.

Although the applied loads (3–10 N) and speeds (10–30 mm/s) represent laboratory-scale testing, the corresponding contact pressures (~0.3–1 MPa) replicate the near-surface stresses experienced at the rod–seal interface in operating hydraulic systems. Thus, the mechanisms observed, like adhesive transfer, micro-abrasion, viscoelastic deformation, and filler-matrix debonding, reflect the same degradation processes that occur under elevated industrial pressures. The specific wear rate, measured in mm3/Nm, is a normalized, scale-independent number that can be used to directly compare to real-world conditions using the Archard wear relation. To relate these estimates to realistic WEC operating conditions, the applied load (10 N) and sliding velocity (30 mm/s) represent a simplified upper-bound duty cycle for a point-absorber piston seal. Typical WEC systems operate at 0.2–1 Hz, corresponding to approximately 17,000–86,000 strokes per day. For a 20 mm stroke length, this value yields an approximate yearly sliding distance of 365 km. Thus, the Archard-based predictions correspond to the cumulative distance a WEC piston seal would experience over several years of operation, providing a reasonable first-order equivalence between laboratory measurements and field exposure. Industries can apply these experimentally derived coefficients in combination with actual load and stroke data to estimate seal life, define safe operational envelopes, and develop accelerated durability tests.