Research Progress of Thermally Conductive Rubber Composites for Tire Heat Dissipation

Abstract

1. Introduction

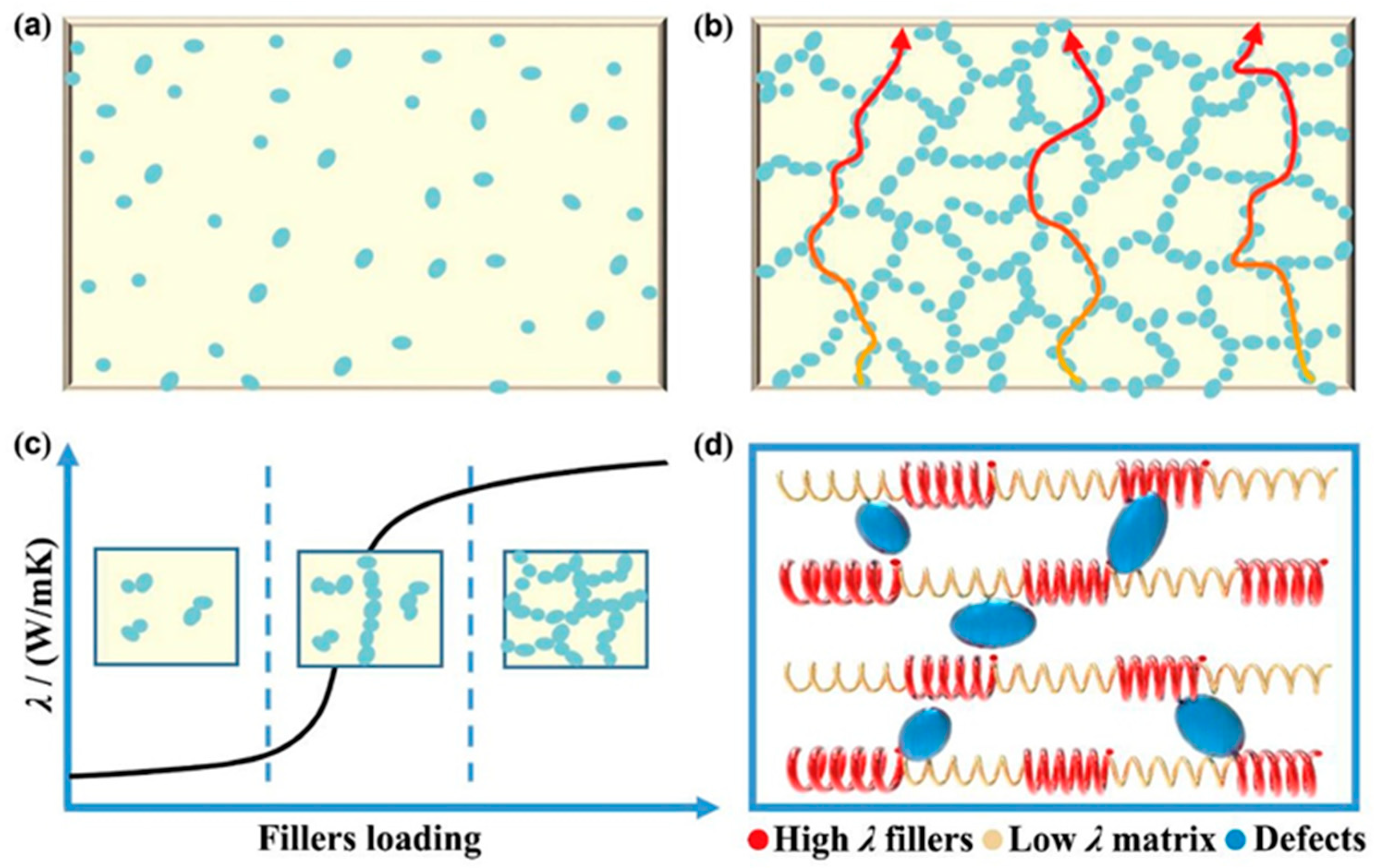

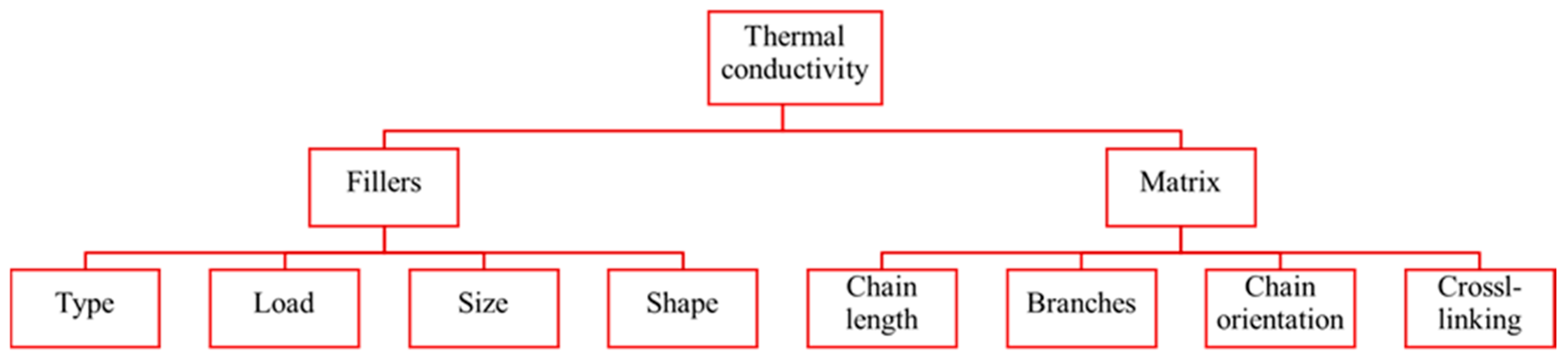

2. Thermal Conductivity Mechanism

3. Tire Rubber Heat Dissipation and Thermal Conductivity Influencing Factors

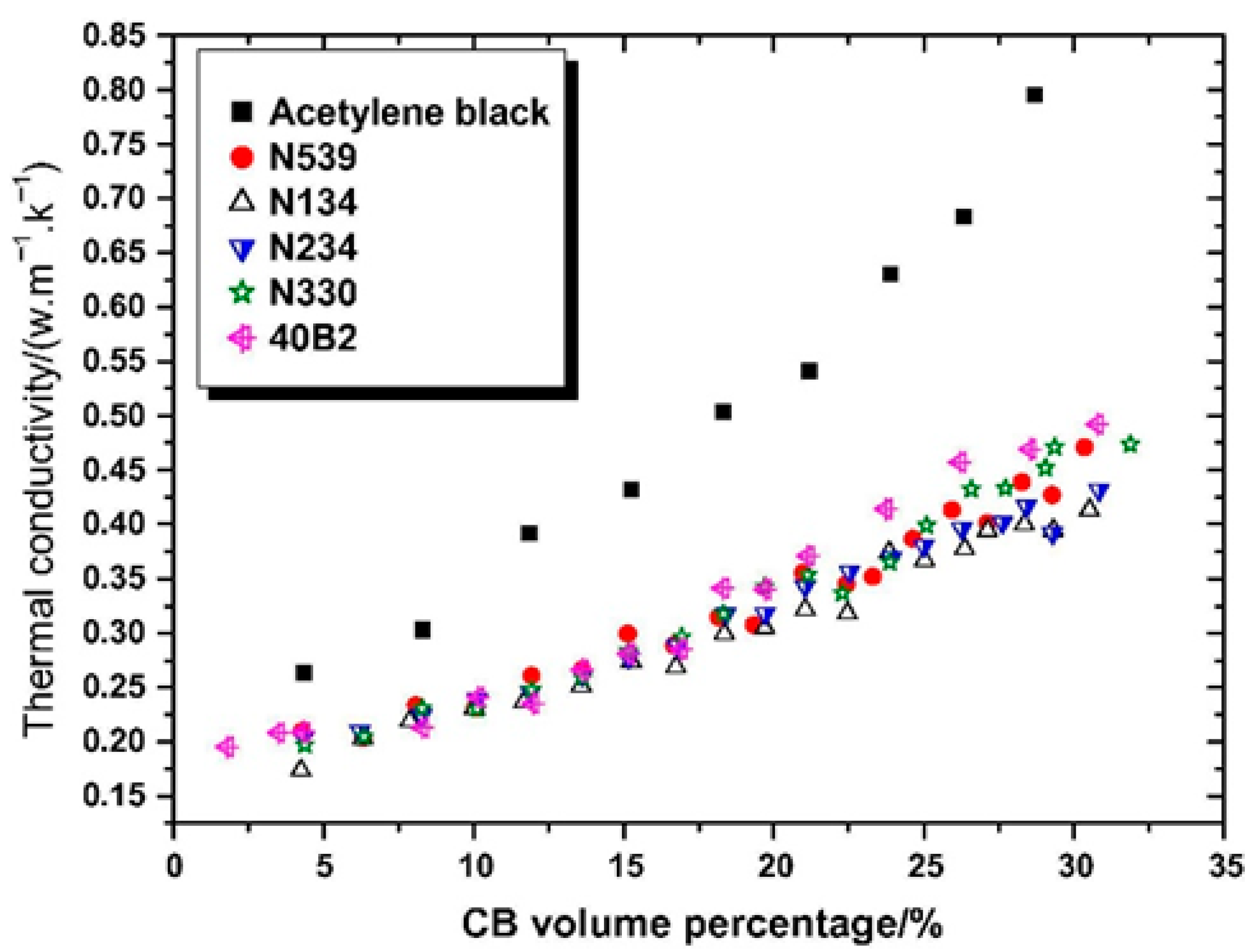

3.1. Types of Fillers

3.2. Fillers Shape

3.3. Fillers Loading

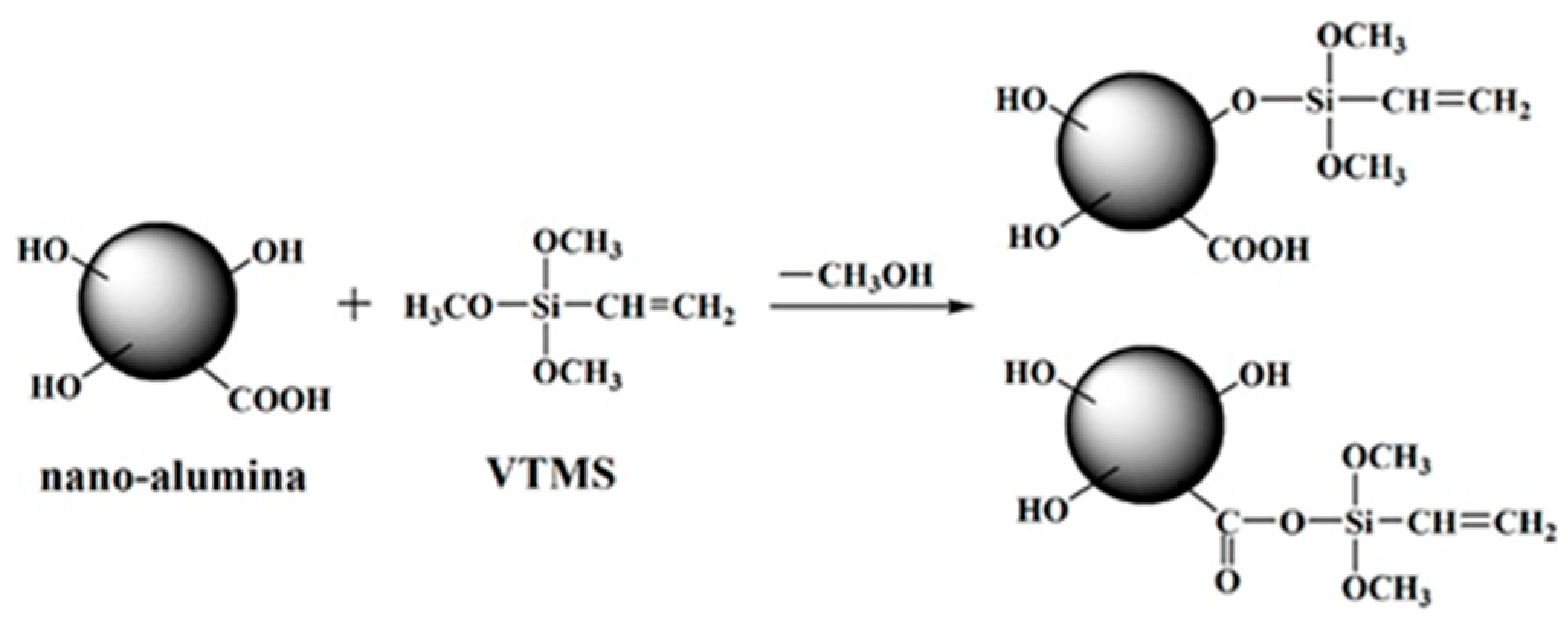

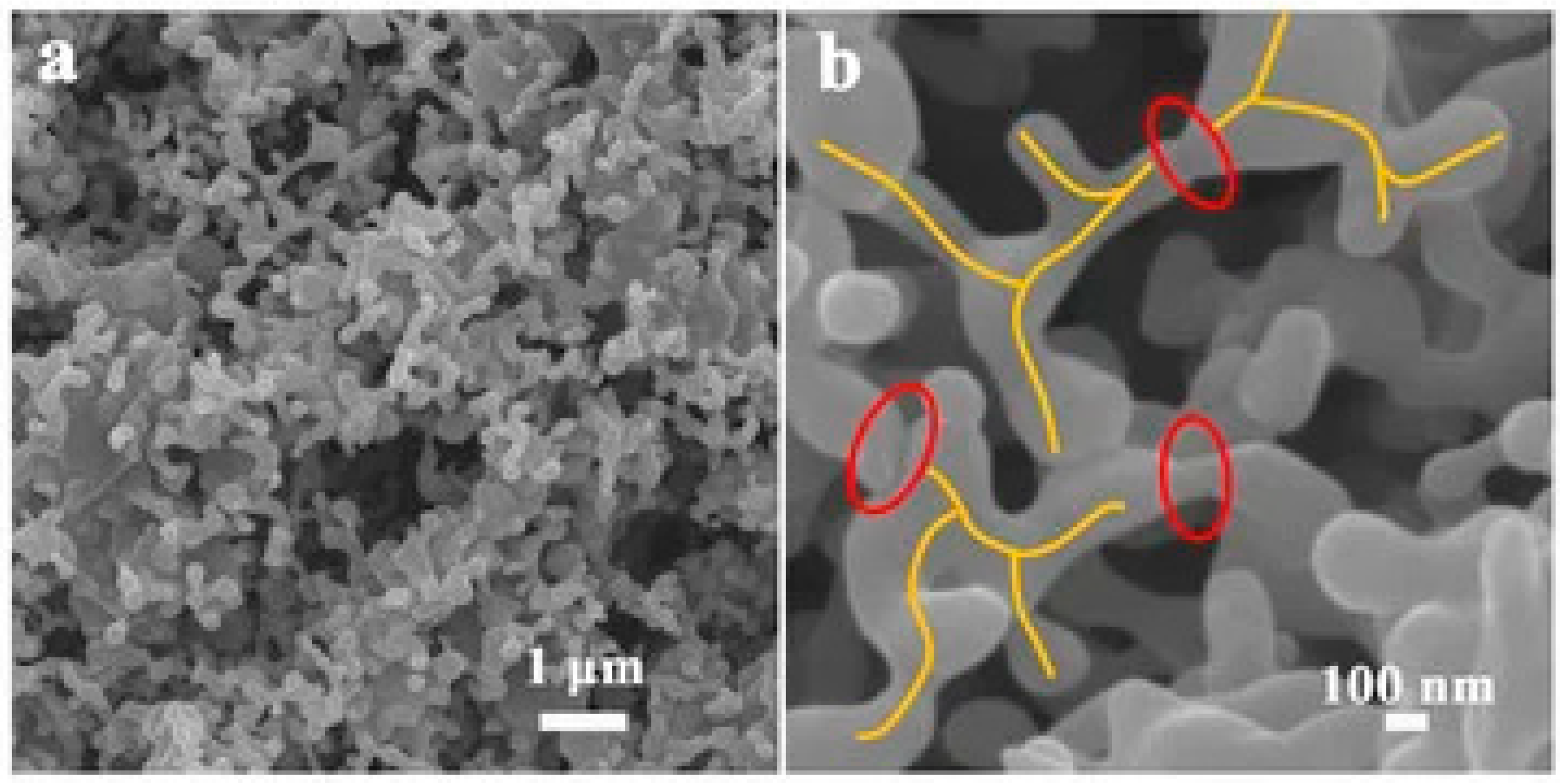

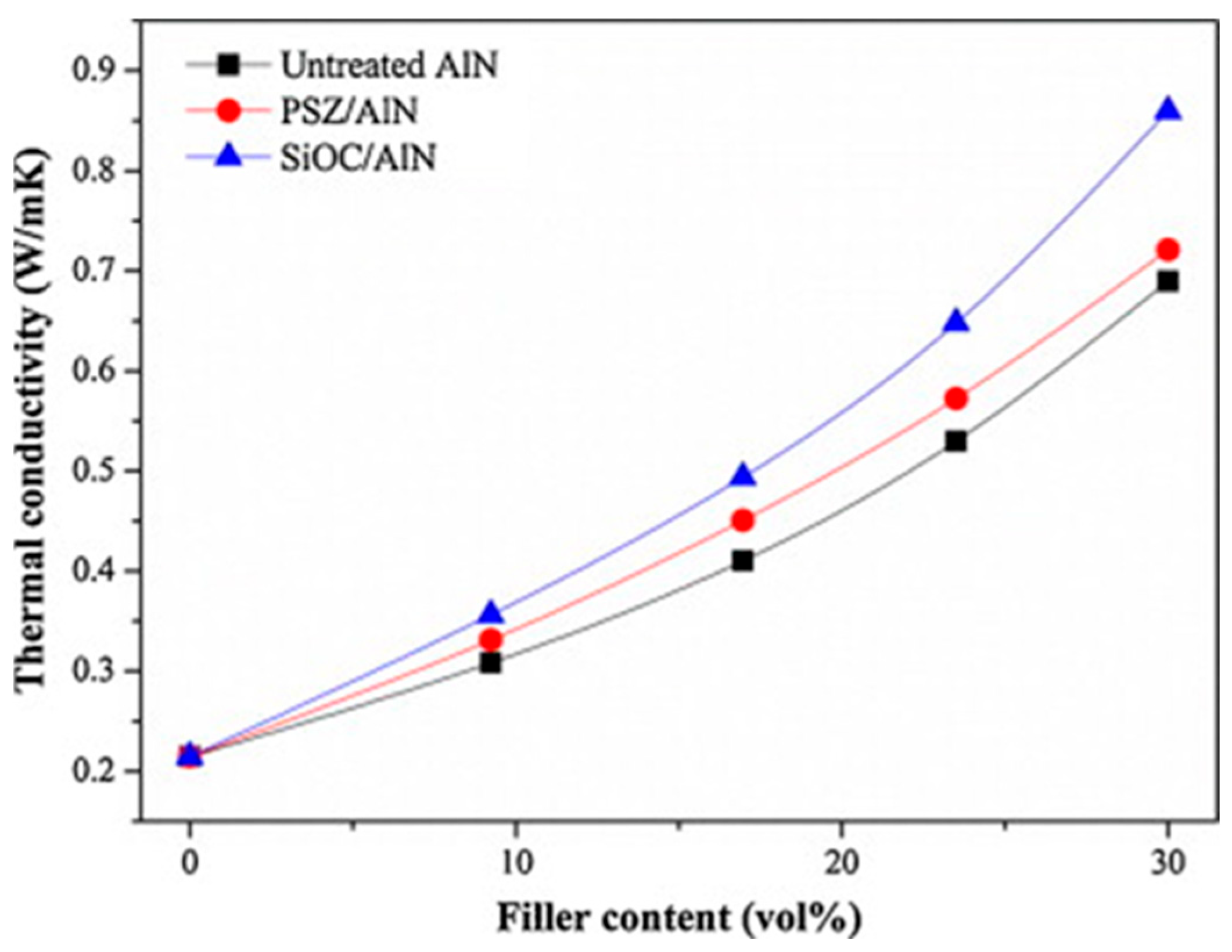

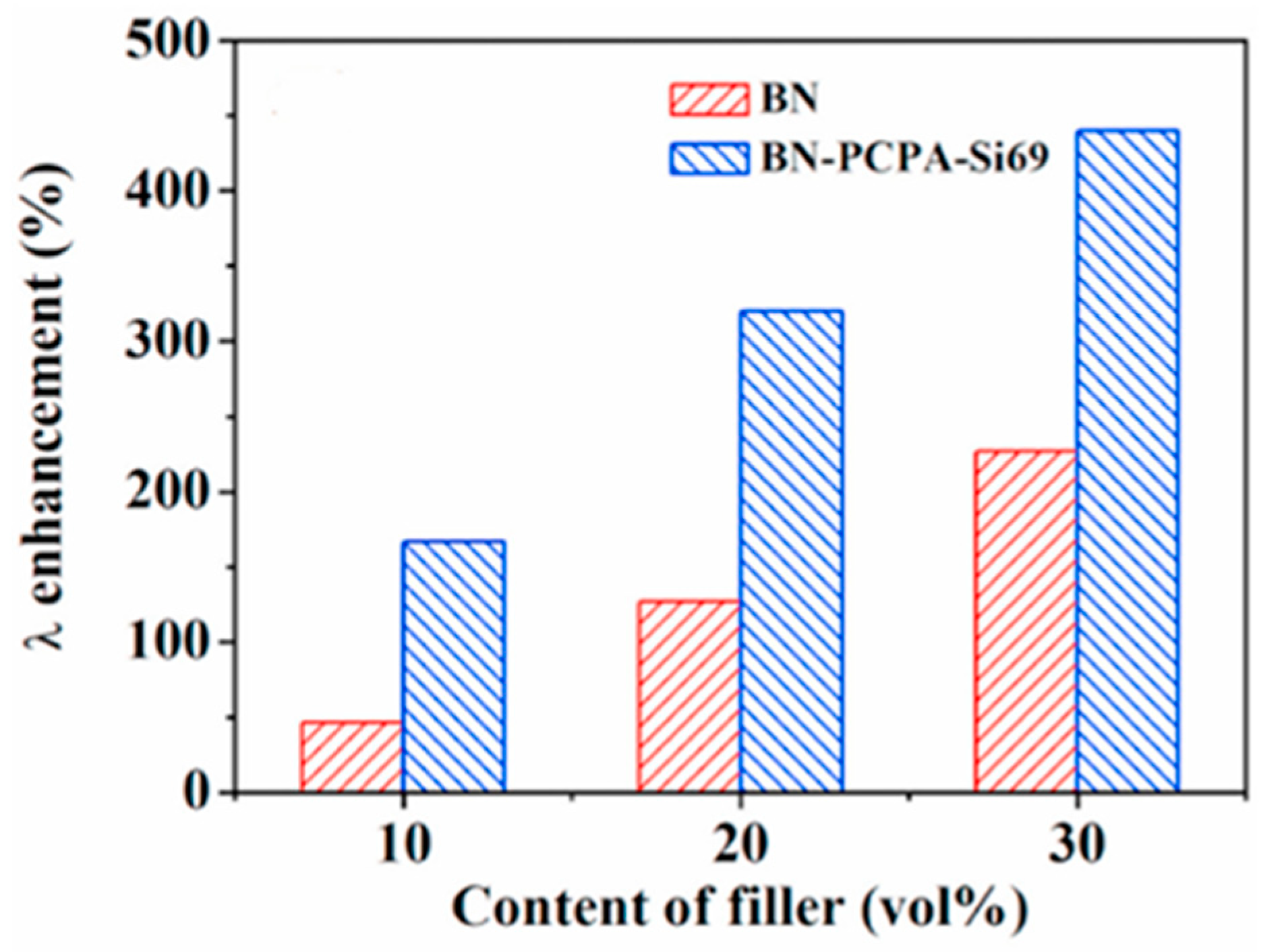

3.4. Filler Functionalization

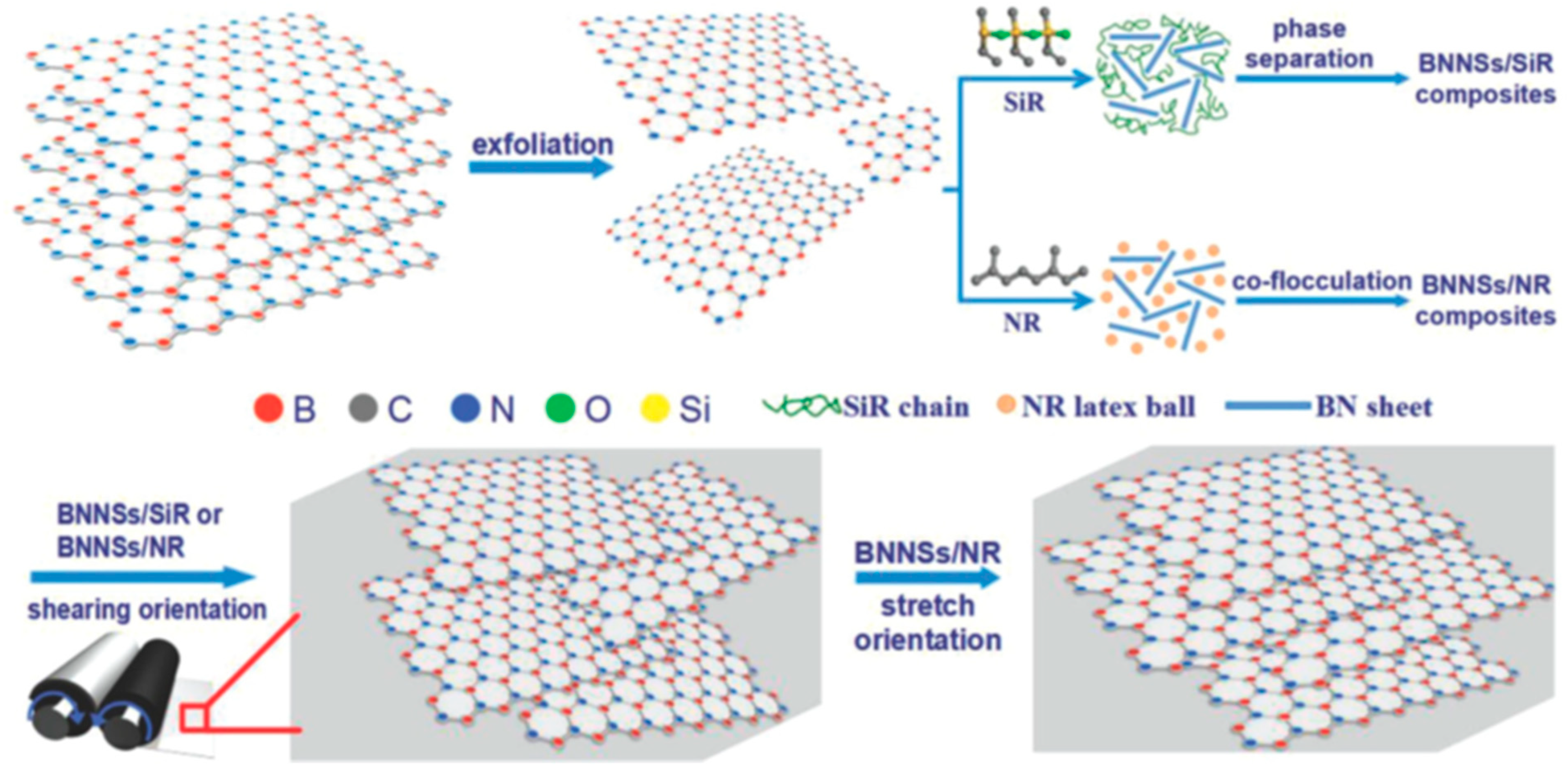

3.5. Fillers Orientation

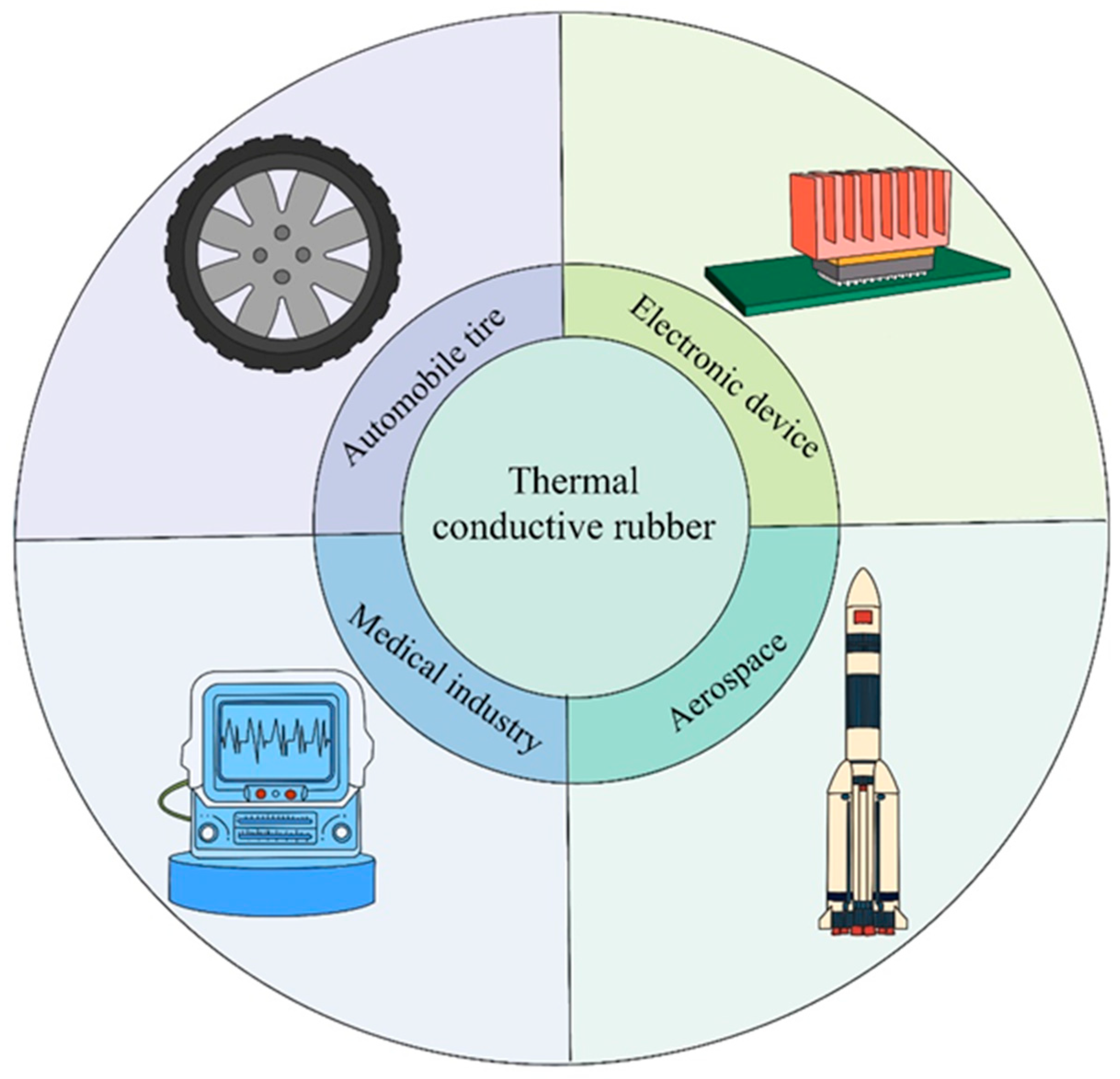

4. From Microelectronics to Tires: Applications and Challenges of Thermally Conductive Rubber Composites

4.1. Metallic Materials

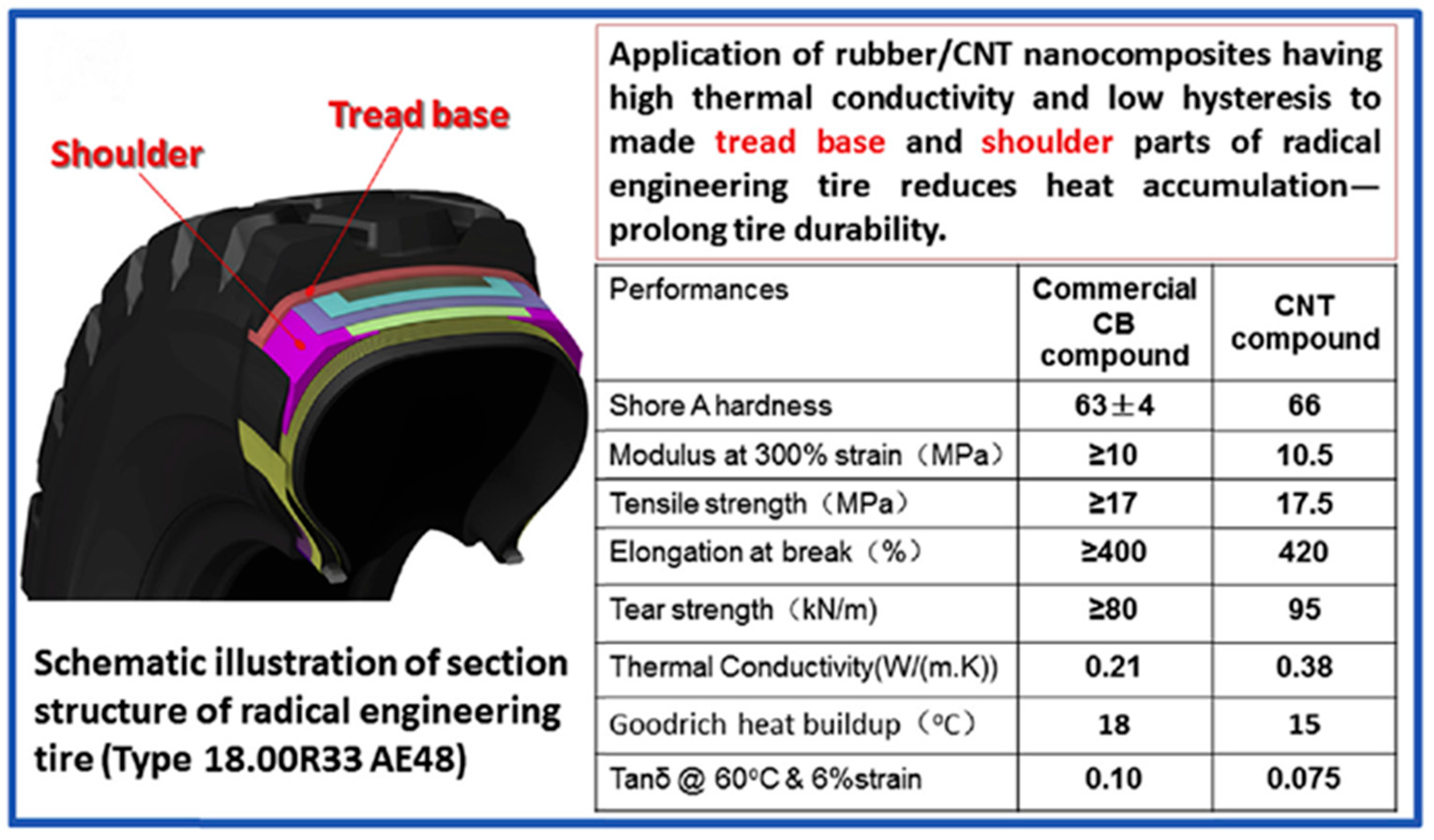

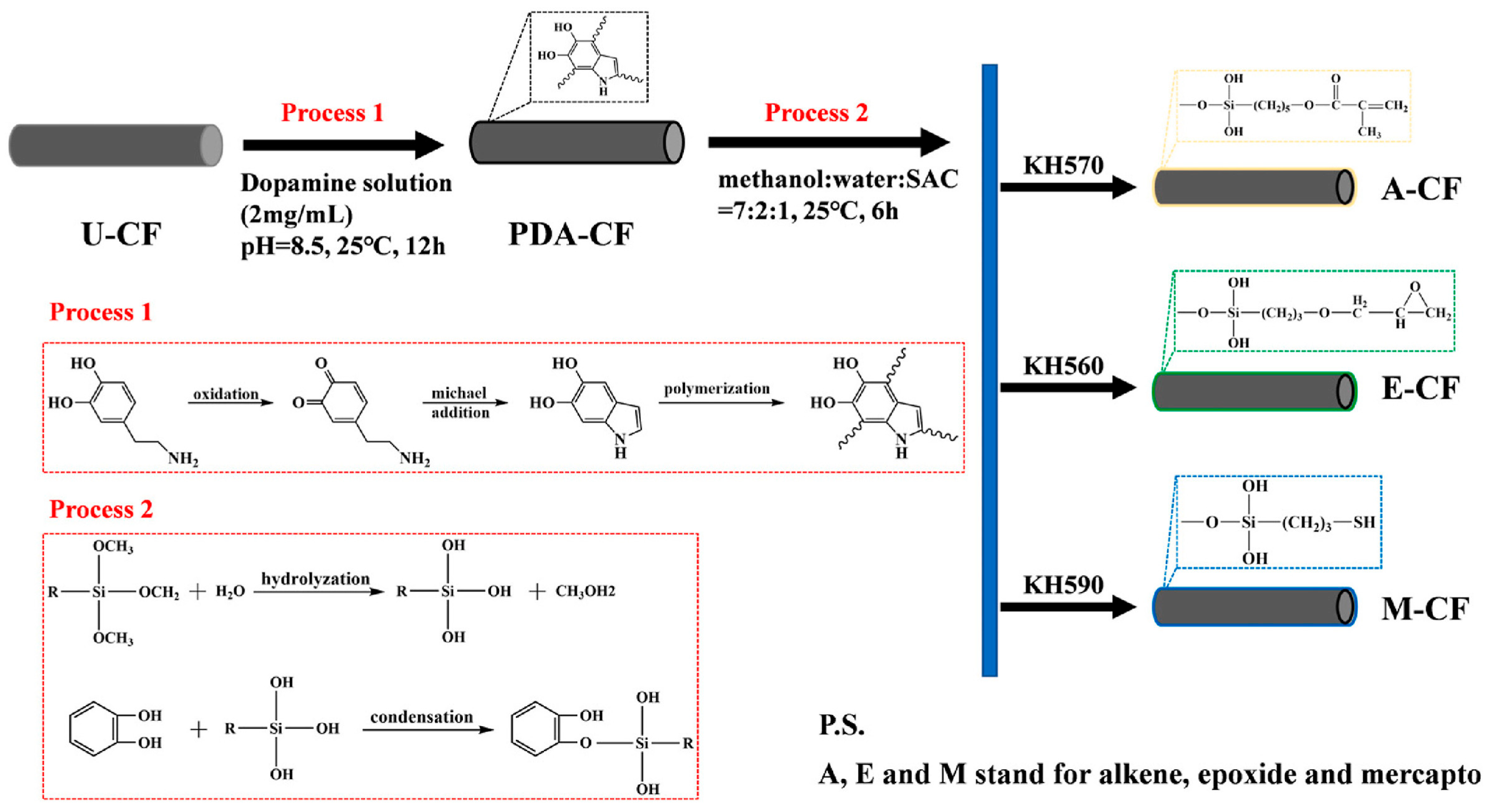

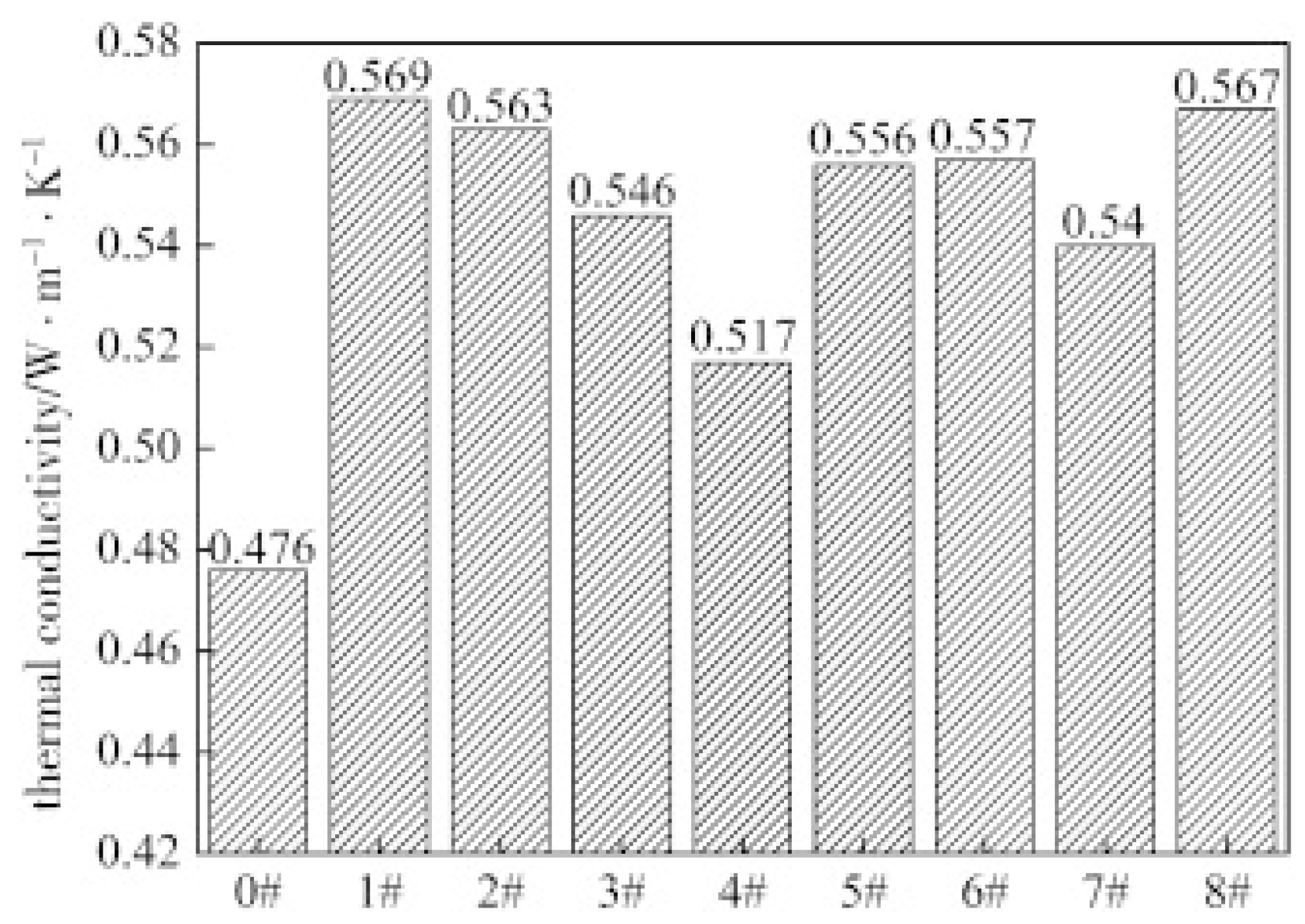

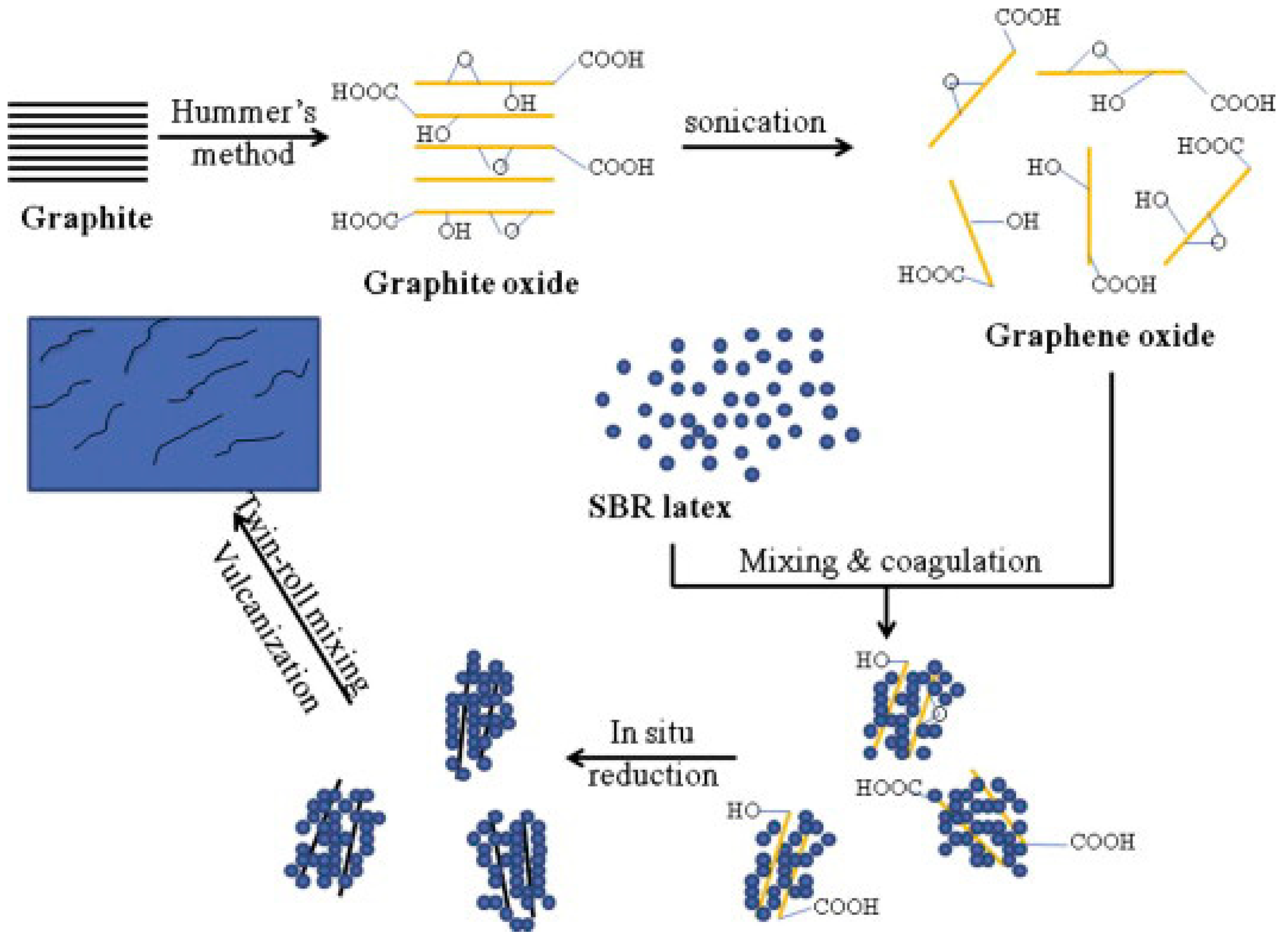

4.2. Carbon-Based Materials

4.3. Ceramic Fillers

4.3.1. Oxides

4.3.2. Nitrides

4.3.3. Carbides

4.4. Hybridized Fillers

5. Application of Microsimulation in Optimizing Thermal Conductivity of Rubber Tires

6. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Hu, F.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Ren, J.; Guo, H.; Shalash, M.; He, M.; Hou, H.; et al. An Overview of Polymer-Based Thermally Conductive Functional Materials. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 218, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Cao, Y.; Yang, K.; Dong, H.; Cheng, Q.; Chen, Y. Review of Boron Nitride Based Polymer Composites with Ultrahigh Thermal Conductivity: Critical Strategies and Applications. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2025, 200, 109289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, W.; Wei, Z.; Chen, C.; Shi, D. Discussion on the Thermal Conductive Network Threshold of Al2O3/Co-Continuous Phase Polymer Composites. Nano Mater. Sci. 2024, S2589965124001557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, K.; Guo, Y.; Gu, J. Liquid Crystalline Polyimide Films with High Intrinsic Thermal Conductivities and Robust Toughness. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 4934–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Puttegowda, M.; Jagadeesh, P.; Marwani, H.M.; Asiri, A.M.; Manikandan, A.; Parwaz Khan, A.A.; Ashraf, G.M.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Review on Nitride Compounds and Its Polymer Composites: A Multifunctional Material. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 2175–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilova-Tret′yak, S.M. On Thermophysical Properties of Rubbers and Their Components. J. Eng. Phys. Thermophys. 2016, 89, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkhi Khasraghi, S.; Momenilandi, M.; Shojaei, A. Tire Tread Performance of Silica-Filled SBR/BR Rubber Composites Incorporated with Nanodiamond and Nanodiamond/Nano-SiO2 Hybrid Nanoparticle. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 126, 109068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, M.R.H.; Mathews, L.D.; Mateti, S.; Salim, N.V.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Govindaraj, P.; Hameed, N. Boron Nitride Based Polymer Nanocomposites for Heat Dissipation and Thermal Management Applications. Appl. Mater. Today 2022, 29, 101672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, N.; Laachachi, A.; Ferriol, M.; Lutz, M.; Toniazzo, V.; Ruch, D. Review of Thermal Conductivity in Composites: Mechanisms, Parameters and Theory. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016, 61, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, K.; Feng, Y.; Liang, L.; Chi, M.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X. Recent Advances in Thermal-Conductive Insulating Polymer Composites with Various Fillers. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 178, 107998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ginzburg, V.V.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, W.; Huang, Y.; Du, L.; Chen, B. Thermal Conductivity of Polymer-Based Composites: Fundamentals and Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016, 59, 41–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Hong, C.; Jang, K.-S. Theoretical Analysis and Development of Thermally Conductive Polymer Composites. Polymer 2019, 176, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lin, Y.; Li, P.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, C.; Xu, H.; Xie, H.; Huang, X. Unidirectional Thermal Conduction in Electrically Insulating Phase Change Composites for Superior Power Output of Thermoelectric Generators. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 225, 109500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shen, X.; Yang, W.; Kim, J. Templating Strategies for 3D-Structured Thermally Conductive Composites: Recent Advances and Thermal Energy Applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 133, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.-F. Thermal Conductivity of Graphene-Polymer Composites: Mechanisms, Properties, and Applications. Polymers 2017, 9, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, K.; Saito, T.; Kawaguchi, T.; Satoh, I. Percolation Effect on Thermal Conductivity of Filler-Dispersed Polymer Composites. J. Therm. Sci. Technol. 2017, 12, JTST0013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, K.; Liu, Y.; Yu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, F.; Fu, Q. Preparation of Highly Thermally Conductive but Electrically Insulating Composites by Constructing a Segregated Double Network in Polymer Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 175, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, B. Thermal Conductivity of Polymers and Their Nanocomposites. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Qiu, H.; Ruan, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, J. Flexible and Insulating Silicone Rubber Composites with Sandwich Structure for Thermal Management and Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 219, 109253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, D.; Moon, C.M.; Kim, D.; Baik, S. Ultrahigh Thermal Conductivity of Interface Materials by Silver-Functionalized Carbon Nanotube Phonon Conduits. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 7220–7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Xie, C.; Li, H.; Dang, J.; Geng, W.; Zhang, Q. Thermal Percolation Behavior of Graphene Nanoplatelets/Polyphenylene Sulfide Thermal Conductivity Composites. Polym. Compos. 2014, 35, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwalowo, A.; Nguyen, N.; Zhang, S.; Park, J.G.; Liang, R. Electrical and Thermal Conductivity Improvement of Carbon Nanotube and Silver Composites. Carbon 2019, 146, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradhana, R.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Novel Electrically Conductive Epoxy/Reduced Graphite Oxide/Silica Hollow Microspheres Adhesives with Enhanced Lap Shear Strength and Thermal Conductivity. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 169, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, J.J.; Weng, G.J. Theory of Thermal Conductivity of Graphene-Polymer Nanocomposites with Interfacial Kapitza Resistance and Graphene-Graphene Contact Resistance. Carbon 2018, 137, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ruan, K.; Wang, G.; Gu, J. Advances and Mechanisms in Polymer Composites toward Thermal Conduction and Electromagnetic Wave Absorption. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 1195–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Ruan, K.; Shi, X.; Yang, X.; Gu, J. Factors Affecting Thermal Conductivities of the Polymers and Polymer Composites: A Review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 193, 108134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Lu, H.; Lin, W.; Qiao, C.; Hu, C.; Jia, Y. Numerical Analysis of the Dependence of Rubber Hysteresis Loss and Heat Generation on Temperature and Frequency. Mech. Time-Depend. Mater. 2019, 23, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Jiang, D. Review on Heat Generation of Rubber Composites. Polymers 2022, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-J.; Hwang, S.-J. Temperature Prediction of Rolling Tires by Computer Simulation. Math. Comput. Simul. 2004, 67, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafrnec, M.; Juma, M.; Toman, J.; Jurĉiová, J.; Kuĉma, A. Thermal Diffusivity of Rubber Compounds. Plast. Rubber Compos. 1999, 28, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhang, Y. Robust, Thermally Conductive and Damping Rubbers with Recyclable and Self-Healable Capability. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 175, 107783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeygunawardane, G.A.; Weragoda, S.; Senevirathne, N.; Liyanage, E. Characterization of Curing Status of Commercial Tire Compounds with Vein Graphite Powder and Its Particle Sizes—Experimental and Computational Study. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; An, S.; Teng, F.; Su, B.L.; Wang, Y.S. Thermo-Mechanical Behavior of Solid Rubber Tire under High-Speed Free Rolling Conditions. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 3743–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattani, P.; Cattani, L.; Magrini, A. Tyre–Road Heat Transfer Coefficient Equation Proposal. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaska, K.; Rybak, A.; Kapusta, C.; Sekula, R.; Siwek, A. Enhanced Thermal Conductivity of Epoxy–Matrix Composites with Hybrid Fillers. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2015, 26, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Feng, Y.; Yin, J. Recent Progress in Polymer/Two-Dimensional Nanosheets Composites with Novel Performances. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 126, 101505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Luo, T. Chain Length Effect on Thermal Transport in Amorphous Polymers and a Structure–Thermal Conductivity Relation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 15523–15530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudenne, A.; Mamunya, Y.; Levchenko, V.; Garnier, B.; Lebedev, E. Improvement of Thermal and Electrical Properties of Silicone–Ni Composites Using Magnetic Field. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 63, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Du, Y.; Bu, Q.; Cao, L.; Zong, C. Mussel Inspired Modification of Nanodiamonds for Thermally Conductive, and Electrically Insulating Rubber Composites. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 130, 109457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva, M.; Kamkar Dallakeh, M.; Ahmadi, M.; Lakhi, M. Effects of Silicon Carbide as a Heat Conductive Filler in Butyl Rubber for Bladder Tire Curing Applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 29, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Fina, A. Thermal Conductivity of Carbon Nanotubes and Their Polymer Nanocomposites: A Review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 914–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akishin, G.P.; Turnaev, S.K.; Vaispapir, V.Y.; Gorbunova, M.A.; Makurin, Y.N.; Kiiko, V.S.; Ivanovskii, A.L. Thermal Conductivity of Beryllium Oxide Ceramic. Refract. Ind. Ceram. 2009, 50, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Peng, C.; Li, T.; Liu, B. Synthesis and Sintering of Beryllium Oxide Nanoparticles. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2010, 20, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirao, K.; Watari, K.; Hayashi, H.; Kitayama, M. High Thermal Conductivity Silicon Nitride Ceramic. MRS Bull. 2001, 26, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Scullion, D.; Gan, W.; Falin, A.; Zhang, S.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Chen, Y.; Santos, E.J.G.; Li, L.H. High Thermal Conductivity of High-Quality Monolayer Boron Nitride and Its Thermal Expansion. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav0129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, H.; Guo, S.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, F. Tetris-Style Stacking Process to Tailor the Orientation of Carbon Fiber Scaffolds for Efficient Heat Dissipation. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, A.; Das, S.; Majumdar, K.; Ramachandra Rao, M.S.; Jaiswal, M. Thermal Transport across Wrinkles in Few-Layer Graphene Stacks. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 1708–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, N.; Mu, L.; Ji, T.; Yang, X.; Kong, J.; Gu, J.; Zhu, J. Thermal Transport in Polymeric Materials and across Composite Interfaces. Appl. Mater. Today 2018, 12, 92–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Tang, Z.; Fang, S.; Wu, S.; Guo, B. Polyrhodanine Mediated Interface in Natural Rubber/Carbon Black Composites toward Ultralow Energy Loss. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2021, 149, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.Z.; Xu, J.Z.; Peng, J.J.; Kang, F.Y.; Du, H.D.; Li, J.; Chiang, S.W.; Xu, C.J.; Hu, N.; Ning, X.S. Experimental and Theoretical Studies of Effective Thermal Conductivity of Composites Made of Silicone Rubber and Al2O3 Particles. Thermochim. Acta 2015, 614, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-T.; Liu, W.-J.; Shen, F.-X.; Zhang, G.-D.; Gong, L.-X.; Zhao, L.; Song, P.; Gao, J.-F.; Tang, L.-C. Processing, Thermal Conductivity and Flame Retardant Properties of Silicone Rubber Filled with Different Geometries of Thermally Conductive Fillers: A Comparative Study. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 238, 109907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Qi, S.; Tu, C.; Zhao, H.; Wang, C.; Kou, J. Effect of the Particle Size of Al2O3 on the Properties of Filled Heat-conductive Silicone Rubber. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 104, 1312–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Qi, S.; Zhao, H.; Liu, N. Thermally Conductive Silicone Rubber Reinforced with Boron Nitride Particle. Polym. Compos. 2007, 28, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, Z.C.; Ma, L.X. Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Properties of Silicone Rubber Filled with Different Particle Sized SiC. Adv. Mater. Res. 2009, 87–88, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntako, R. Effect of Synthesized ZnO Nanoparticles on Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Properties of Natural Rubber. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 284, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemaloglu, S.; Ozkoc, G.; Aytac, A. Properties of Thermally Conductive Micro and Nano Size Boron Nitride Reinforced Silicon Rubber Composites. Thermochim. Acta 2010, 499, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, H.; Ohara, T. Effect of the In-Plane Aspect Ratio of a Graphene Filler on Anisotropic Heat Conduction in Paraffin/Graphene Composites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 12082–12092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evgin, T.; Koca, H.D.; Horny, N.; Turgut, A.; Tavman, I.H.; Chirtoc, M.; Omastová, M.; Novak, I. Effect of Aspect Ratio on Thermal Conductivity of High Density Polyethylene/Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Nanocomposites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 82, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.M.; Mariatti, M.; Busfield, J.J.C. Effects of Types of Fillers and Filler Loading on the Properties of Silicone Rubber Composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2011, 30, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Hackel, N.; Grunert, F.; Ilisch, S.; Beiner, M.; Blume, A. Investigation of Rheological, Mechanical, and Viscoelastic Properties of Silica-Filled SSBR and BR Model Compounds. Polymers 2024, 16, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liang, C.; Yan, Y.; Tao, Y.; An, G.; Li, T. Effect of Noncovalent Bonding Modified Graphene on Thermal Conductivity of Graphene/Natural Rubber Composites Based on Molecular Dynamics Approach. Langmuir 2025, 41, 6565–6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, C.; Zhang, P.; Seraji, S.M.; Xie, R.; Chen, L.; Liu, D.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, H.; Fu, Y.; Xu, H.; et al. Effects of BN/GO on the Recyclable, Healable and Thermal Conductivity Properties of ENR/PLA Thermoplastic Vulcanizates. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 152, 106686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaberi Mofrad, F.; Ostad Movahed, S.; Ahmadpour, A. Surface Modification of Commercial Carbon Black by Silane Coupling Agents for Improving Dispersibility in Rubber Compounds. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yi, J.; Yin, Y.; Song, Y.; Xiong, C. Thermal Conductivity and Electrical Insulation Properties of H-BN@PDA/Silicone Rubber Composites. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2021, 117, 108485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Qin, M.; Feng, Y. Toward Highly Thermally Conductive All-Carbon Composites: Structure Control. Carbon 2016, 109, 575–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; He, Y.; Gong, X. Effect of Electric Field Induced Alignment and Dispersion of Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes on Properties of Natural Rubber. Results Phys. 2018, 9, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Huang, R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qin, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y. Thermally Conductive Silicone Rubber Composites with Vertically Oriented Carbon Fibers: A New Perspective on the Heat Conduction Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 441, 136104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Chiang, S.-W.; Liu, M.; Liang, X.; Li, J.; Gan, L.; He, Y.; Li, B.; Kang, F.; Du, H. Enhanced Thermal Conductivity of Alumina and Carbon Fibre Filled Composites by 3-D Printing. Thermochim. Acta 2020, 690, 178649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Duan, X.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, B.; Lian, Q.; Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wong, C.-P. Enhanced Thermal Conductivity of Natural Rubber Based Thermal Interfacial Materials by Constructing Covalent Bonds and Three-Dimensional Networks. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 135, 105928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fan, L.; Li, R.; Xu, Y.; Fu, Q. Preparation of Polymer Composites with High Thermal Conductivity by Constructing a “Double Thermal Conductive Network” via Electrostatic Spinning. Compos. Commun. 2022, 36, 101371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cai, L.; He, A.; Ma, H.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L. Facile Strategies for Green Tire Tread with Enhanced Filler-Matrix Interfacial Interactions and Dynamic Mechanical Properties. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 203, 108601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.-C.; Jin, Y.-F.; Ren, J.-W.; Zhao, L.-H.; Yan, D.-X.; Li, Z.-M. Highly Thermally Conductive Liquid Metal-Based Composites with Superior Thermostability for Thermal Management. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 2904–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.; Guo, H.; Niu, H.; Li, R.; Yin, G.; Kang, L.; Ren, L.; Lv, R.; Tian, H.; Liu, S.; et al. Core–Shell Engineered Fillers Overcome the Electrical-Thermal Conductance Trade-Off. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 30593–30604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Yu, M.; Kathaperumal, M.; Wong, C.-P. A Review of the Thermal Conductivity of Silver-Epoxy Nanocomposites as Encapsulation Material for Packaging Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kong, Z.; An, Q.; Wu, T.; Zou, L. A Flexible Thermal Interface Composite of Copper-Coated Carbon Felts with 3d Architecture in Silicon Rubber. Polymer 2024, 313, 127747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Li, Y. Thermal Conductivity of Aluminum Alloys—A Review. Materials 2023, 16, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.J.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Guo, W.; Xue, Y.; Yao, Z.X. Mechanical, Morphological and Thermally Behaviors of Natural Rubber/Aluminum Powder Composites. Key Eng. Mater. 2012, 501, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Choi, E.J.; Cheon, H.J.; Choi, W.I.; Shin, W.S.; Lim, J.-M. Fabrication of Al2O3/ZnO and Al2O3/Cu Reinforced Silicone Rubber Composite Pads for Thermal Interface Materials. Polymers 2021, 13, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutika, R.; Zhou, S.H.; Napolitano, R.E.; Bartlett, M.D. Mechanical and Functional Tradeoffs in Multiphase Liquid Metal, Solid Particle Soft Composites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1804336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.R.J.; Alahyari, A.A.; Eastman, S.A.; Thibaud-Erkey, C.; Johnston, S.; Sobkowicz, M.J. Review of Polymers for Heat Exchanger Applications: Factors Concerning Thermal Conductivity. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 113, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N.; Kumar, V.; Jeong, S.-U.; Park, S.-S. The Effect of Rubber–Metal Interactions on the Mechanical, Magneto–Mechanical, and Electrical Properties of Iron, Aluminum, and Hybrid Filler-Based Styrene–Butadiene Rubber Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X.; Li, N.; Zeng, M.; Wang, Q. Organic Phase Change Materials Confined in Carbon-Based Materials for Thermal Properties Enhancement: Recent Advancement and Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 108, 398–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, P.; Tang, Z.; Xu, X.; Gao, H.; Wang, G. Carbon-Based Composite Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage, Transfer, and Conversion. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2001274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Sun, S.; Zhao, A.; Zhang, H.; Zuo, M.; Song, Y.; Zheng, Q. Influence of Carbon Black on the Payne Effect of Filled Natural Rubber Compounds. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 203, 108586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Tian, K.; Ma, L.; Li, W.; Yao, S. The Effect of Carbon Black Morphology to the Thermal Conductivity of Natural Rubber Composites. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 137, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijina, V.; Jandas, P.J.; Joseph, S.; Gopu, J.; Abhitha, K.; John, H. Recent Trends in Industrial and Academic Developments of Green Tyre Technology. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 8215–8244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, J.; Hou, G.; Ma, J.; Wang, W.; Wei, F.; Zhang, L. From Nano to Giant? Designing Carbon Nanotubes for Rubber Reinforcement and Their Applications for High Performance Tires. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2016, 137, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Qu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Song, L.; Li, Z. Wear Property Improvement by Short Carbon Fiber as Enhancer for Rubber Compound. Polym. Test. 2019, 77, 105879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tu, Q.; Shen, X.; Fang, Z.; Bi, S.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, X. Enhancing the Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Carbon Fiber/Natural Rubber Composites by Co-Modification of Dopamine and Silane Coupling Agents. Polym. Test. 2023, 126, 108164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Ma, L.; He, Y.; Yan, H.; Wu, Z.; Li, W. Modified Graphite Filled Natural Rubber Composites with Good Thermal Conductivity. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 23, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Yuan, Q.; Qiu, M.; Yu, J.; Jiang, N.; Lin, C.-T.; Dai, W. Rational Design of Graphene/Polymer Composites with Excellent Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Effectiveness and High Thermal Conductivity: A Mini Review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 117, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethulekshmi, A.S.; Saritha, A.; Joseph, K. A Comprehensive Review on the Recent Advancements in Natural Rubber Nanocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 194, 819–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, W.; Tang, M.; Wu, J.; Huang, G.; Li, H.; Lei, Z.; Fu, X.; Li, H. Multifunctional Properties of Graphene/Rubber Nanocomposites Fabricated by a Modified Latex Compounding Method. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2014, 99, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Bai, L.; Tian, H.; Li, X.; Yuan, F. Recent Progress of Thermal Conductive Ploymer Composites: Al2O3 Fillers, Properties and Applications. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 152, 106685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, Y. Enhancement of Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Properties of Silicone Rubber Composites by Using Acrylate Grafted Siloxane Copolymers. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 391, 123476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ye, K.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Yan, C.; Wang, Z.; Lin, C.-T.; Jiang, N.; Yu, J. Cotton Candy-Templated Fabrication of Three-Dimensional Ceramic Pathway Within Polymer Composite for Enhanced Thermal Conductivity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 44700–44707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Hu, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Bian, X.; Lin, J.; Du, X. Performance Improvement in Nano-Alumina Filled Silicone Rubber Composites by Using Vinyl Tri-Methoxysilane. Polym. Test. 2018, 67, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Li, X.; Tian, H.; Bai, L.; Yuan, F. A Novel Branched Al2O3/Silicon Rubber Composite with Improved Thermal Conductivity and Excellent Electrical Insulation Performance. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porrawatkul, P.; Nuengmatcha, P.; Kuyyogsuy, A.; Pimsen, R.; Rattanaburi, P. Effect of Na and Al Doping on ZnO Nanoparticles for Potential Application in Sunscreens. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2023, 240, 112668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, C.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J. Preparation and Mechanism of High-Performance Ammonia Sensor Based on Tungsten Oxide and Zinc Oxide Composite at Room Temperature. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2023, 45, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhini, J.; Karthikeyan, E.; Rajeshkumar, S. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Eco-Friendly Advancements for Biomedical Marvels. Resour. Chem. Mater. 2024, 3, 294–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Zeid, S.; Leprince-Wang, Y. Advancements in ZnO-Based Photocatalysts for Water Treatment: A Comprehensive Review. Crystals 2024, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostoni, S.; Milana, P.; Di Credico, B.; D’Arienzo, M.; Scotti, R. Zinc-Based Curing Activators: New Trends for Reducing Zinc Content in Rubber Vulcanization Process. Catalysts 2019, 9, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.W.; Jeon, S.W.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y. Effective Heat Dissipation and Geometric Optimization in an LED Module with Aluminum Nitride (AlN) Insulation Plate. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 76, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaad, A.M.; Al-Bataineh, Q.M.; Qattan, I.A.; Ahmad, A.A.; Ababneh, A.; Albataineh, Z.; Aljarrah, I.A.; Telfah, A. Measurement and Ab Initio Investigation of Structural, Electronic, Optical, and Mechanical Properties of Sputtered Aluminum Nitride Thin Films. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.T.; Sukachonmakul, T.; Kuo, M.T.; Wang, Y.H.; Wattanakul, K. Surface Modification of Aluminum Nitride by Polysilazane and Its Polymer-Derived Amorphous Silicon Oxycarbide Ceramic for the Enhancement of Thermal Conductivity in Silicone Rubber Composite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 292, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Han, Q.; Yang, D.; Ni, Y.; Yu, L.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, L. Thermally Conductive Elastomer Composites with Poly(Catechol-Polyamine)-Modified Boron Nitride. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 14006–14012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkarat, M.; Lanagan, M.; Ghosh, D.; Lottes, A.; Budd, K.; Rajagopalan, R. Improved Thermal Conductivity and AC Dielectric Breakdown Strength of Silicone Rubber/BN Composites. Compos. Part C Open Access 2020, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Bai, S.-L.; Wong, C.P. “White Graphene”—Hexagonal Boron Nitride Based Polymeric Composites and Their Application in Thermal Management. Compos. Commun. 2016, 2, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Chen, H.; He, R.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Sun, Z.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wong, C.; Feng, W. MOF Decorated Boron Nitride/Natural Rubber Composites with Heterostructure for Thermal Management Application through Dual Passive Cooling Modes Base on the Improved Thermal Conductivity and Water Sorption-Desorption Process. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 248, 110469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zong, J.; Lei, J.; Li, Z. Enhancing Thermal Conductivity of Silicone Rubber via Constructing Hybrid Spherical Boron Nitride Thermal Network. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Kong, X.; Ni, Y.; Gao, D.; Yang, B.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L. Novel Nitrile-Butadiene Rubber Composites with Enhanced Thermal Conductivity and High Dielectric Constant. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 124, 105447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wang, J.; He, W.; Wei, Z.; Wang, X.; He, Q. Enhancing Mechanical Property and Thermal Conductivity of Fluororubber by the Synergistic Effect of CNT and BN. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 134, 109790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Ni, Y.; Kong, X.; Gao, D.; Wang, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, L. Mussel-Inspired Modification of Boron Nitride for Natural Rubber Composites with High Thermal Conductivity and Low Dielectric Constant. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 177, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shi, Y.; Sa, R.; Ning, N.; Wang, W.; Tian, M.; Zhang, L. Surface Modification of Aramid Fibers by Catechol/Polyamine Codeposition Followed by Silane Grafting for Enhanced Interfacial Adhesion to Rubber Matrix. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 12547–12556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wei, Q.; Yu, L.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, L. Natural Rubber Composites with Enhanced Thermal Conductivity Fabricated via Modification of Boron Nitride by Covalent and Non-Covalent Interactions. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 202, 108590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, L.; Hu, S.; Wen, S.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, L. Fabrication of Highly Oriented Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheet/Elastomer Nanocomposites with High Thermal Conductivity. Small 2015, 11, 1655–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

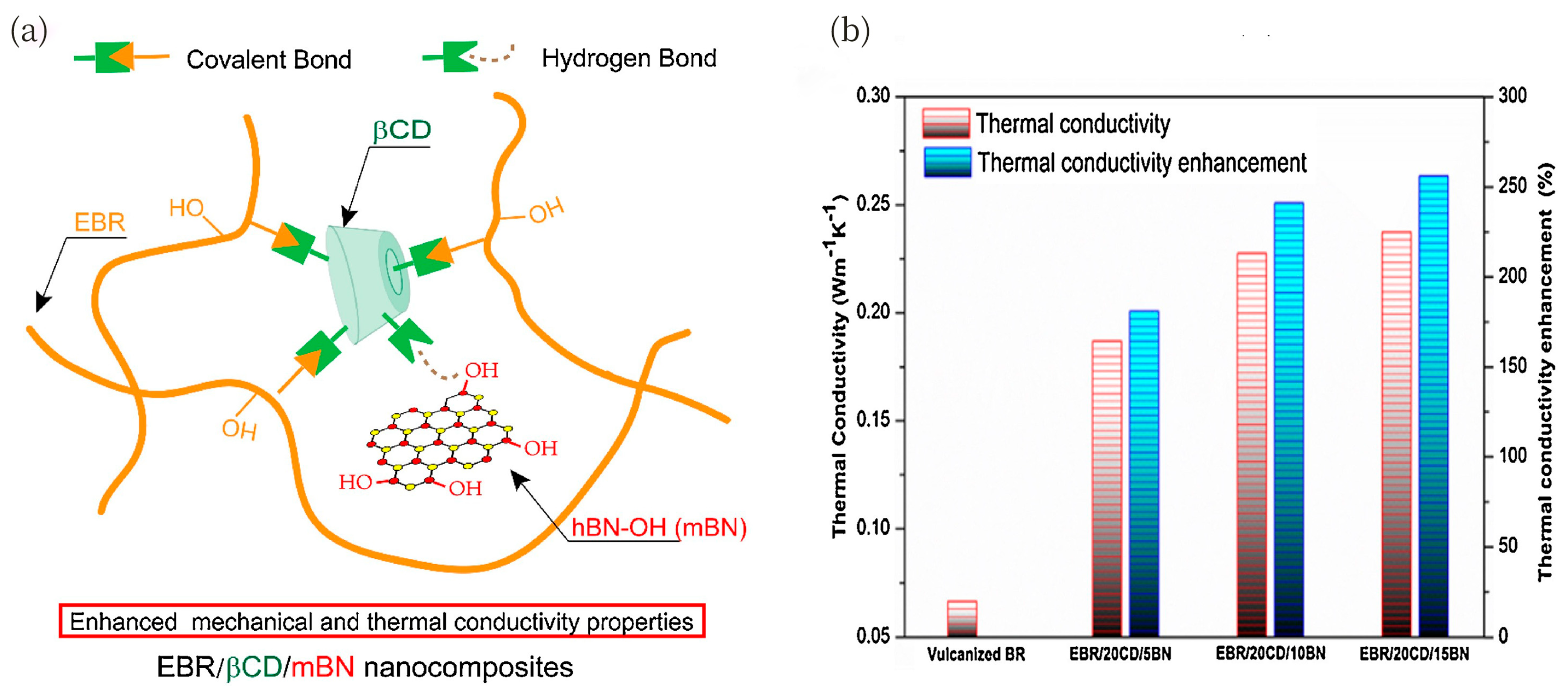

- Yang, Y.; Huang, L.; Dai, Q.; Cui, L.; Liu, S.; Qi, Y.; Dong, W.; He, J.; Bai, C. Fabrication of β-Cyclodextrin-Crosslinked Epoxy Polybutadiene/Hydroxylated Boron Nitride Nanocomposites with Improved Mechanical and Thermal-Conducting Properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 5853–5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harikrishnan, R.; Anirudh Mohan, T.P.; Rahulan, N.; Gopalan, S. Effect of Silicon Nitride on Physical Properties of SBR. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 3833–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimann, R.B. Silicon Nitride, a Close to Ideal Ceramic Material for Medical Application. Ceramics 2021, 4, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derradji, M.; Ramdani, N.; Zhang, T.; Wang, J.; Lin, Z.; Yang, M.; Xu, X.; Liu, W. High Thermal and Thermomechanical Properties Obtained by Reinforcing a Bisphenol-A Based Phthalonitrile Resin with Silicon Nitride Nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 2015, 149, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, N.; Derradji, M.; Feng, T.; Tong, Z.; Wang, J.; Mokhnache, E.-O.; Liu, W. Preparation and Characterization of Thermally-Conductive Silane-Treated Silicon Nitride Filled Polybenzoxazine Nanocomposites. Mater. Lett. 2015, 155, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, S.; Zabihi, A.; Fasihi, M.; Kharat, G.B.P. A Comprehensive Study on the Effect of Highly Thermally Conductive Fillers on Improving the Properties of SBR/BR-Filled Nano-Silicon Nitride. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 32701–32711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. Synthesis, Properties, and Multifarious Applications of SiC Nanoparticles: A Review. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 8882–8913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zeng, X.; Sun, R.; Xu, J.-B.; Wong, C.-P. Vertically Aligned and Interconnected SiC Nanowire Networks Leading to Significantly Enhanced Thermal Conductivity of Polymer Composites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 9669–9678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorg Panah Kharat, G.; Zabihi, A.; Rasouli, S.; Fasihi, M.; Taki, K. Accelerating the Kinetics of Curing Reaction of SBR/BR Blend by Silicon Carbide via Modification of Thermal Diffusivity. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, G.; Huang, G.; Qu, L.; Zhang, P.; Nie, Y.; Wu, J. Natural Rubber with Low Heat Generation Achieved by the Inclusion of Boron Carbide. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 118, 2050–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, M.; Chandrashekar, A.; Gopi, J.A.; Prabhu, T.N. A Nanobridge Strategy to Fabricate Multifunctional Silicone Rubber Nanocomposites with Synergy Interplay in Enhancing Thermal Conductivity via BNNS-GO-PDA@MWCNT Ternary Fillers. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, S1226086X25005775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Zhang, Y. Carbon Nanotube/Reduced Graphene Oxide Hybrid for Simultaneously Enhancing the Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Properties of Styrene-Butadiene Rubber. Carbon 2017, 123, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yang, D.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, L. Constructing of Strawberry-like Core-Shell Structured Al2O3 Nanoparticles for Improving Thermal Conductivity of Nitrile Butadiene Rubber Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 209, 108786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Yang, D. Construction of Thermal Conduction Networks and Decrease of Interfacial Thermal Resistance for Improving Thermal Conductivity of Epoxy Natural Rubber Composites. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 17650–17659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, C.; Tao, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Enhanced Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Properties of Natural Rubber-Based Composites Co-Incorporated with Surface Treated Alumina and Reduced Graphene Oxide. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2021, 116, 108438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, Y. Vertically Aligned Silicon Carbide Nanowires/Reduced Graphene Oxide Networks for Enhancing the Thermal Conductivity of Silicone Rubber Composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 133, 105873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Ni, Y.; Liang, Y.; Li, B.; Ma, H.; Zhang, L. Improved Thermal Conductivity and Electromechanical Properties of Natural Rubber by Constructing Al2O3-PDA-Ag Hybrid Nanoparticles. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 180, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, W.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Gan, L.; Chu, X.; Yao, Y.; He, Y.; Li, B.; Kang, F.; et al. Enhanced Thermal Conductivity by Combined Fillers in Polymer Composites. Thermochim. Acta 2019, 676, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhou, W.; He, Y.; Lv, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Synergetic Improvement of Dielectric Properties and Thermal Conductivity in Zn@ZnO/Carbon Fiber Reinforced Silicone Rubber Dielectric Elastomers. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 181, 108129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xian, Y.; Lin, Y.; Ji, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, L. Construction of Interconnected Al2O3 Doped rGO Network in Natural Rubber Nanocomposites to Achieve Significant Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Strength Enhancement. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 186, 107930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, C.; Fang, H.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Wong, C.-P. A Polymer-Based Thermal Management Material with Enhanced Thermal Conductivity by Introducing Three-Dimensional Networks and Covalent Bond Connections. Carbon 2019, 155, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Yang, D.; Yu, L.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, L. Fabrication of Carboxyl Nitrile Butadiene Rubber Composites with High Dielectric Constant and Thermal Conductivity Using Al2O3@PCPA@GO Hybrids. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 199, 108344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Ma, L.; He, Y.; Chen, H.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, J. Preparation and Performance Evaluation of Natural Rubber Composites with Aluminum Nitride and Aligned Carbon Nanotubes. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2019, 61, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Qiu, J.; Sakai, E.; Zhang, G.; Wu, H.; Guo, S.; Zhang, L.; Yamaguchi, H.; Chonan, Y. Preparation of Continuous Carbon Fiber-filled Silicone Rubber with High Thermal Conductivity through Wrapping. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 1437–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Ye, N.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Z.; Li, J.; Lu, Y. Mimicking Swallow Nest Structure to Construct 3D rGO/BN Skeleton for Enhancing the Thermal Conductivity of the Silicone Rubber Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 248, 110473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

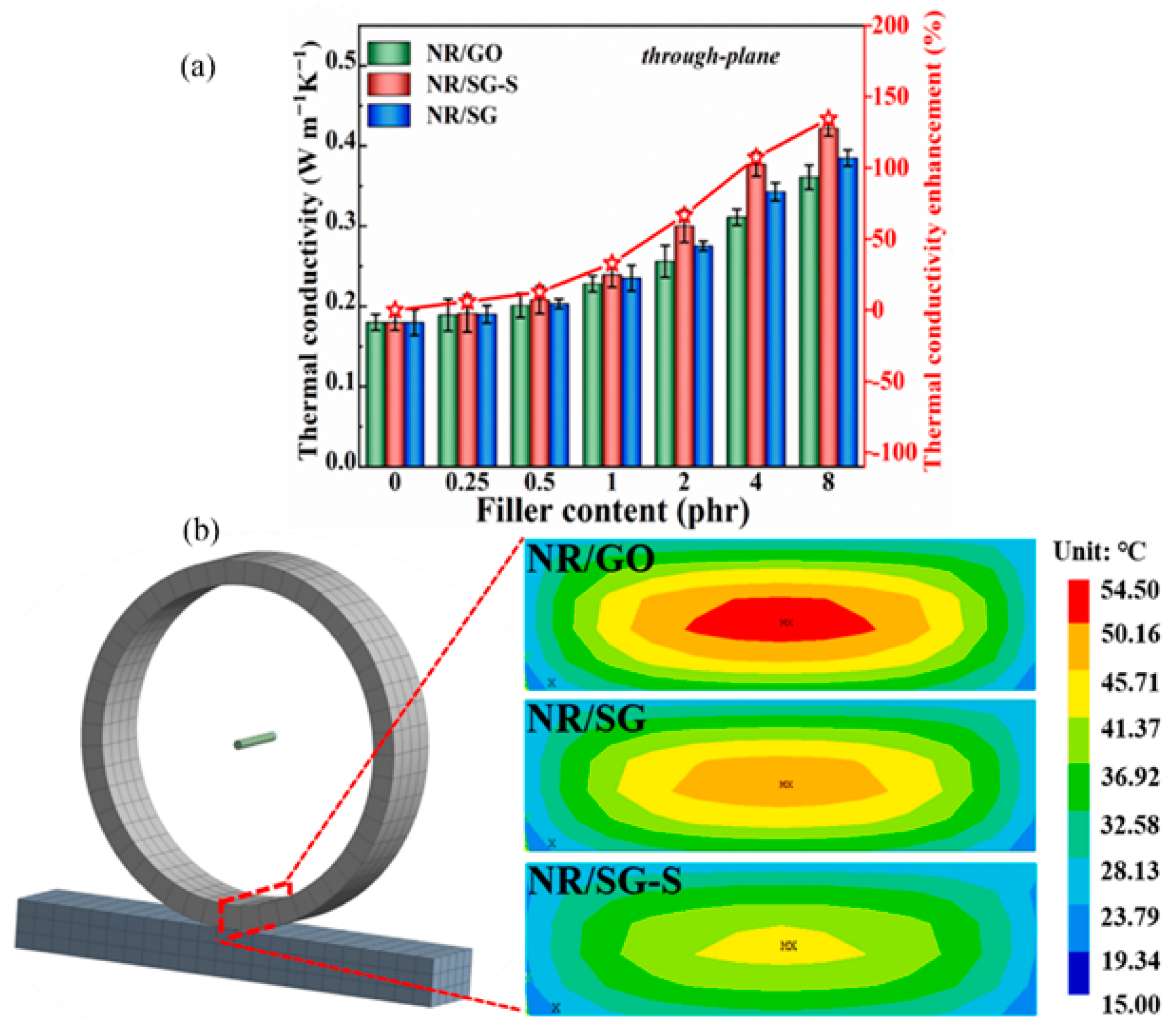

- Duan, X.; Tao, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, G.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, S. Improved Mechanical, Thermal Conductivity and Low Heat Build-up Properties of Natural Rubber Composites with Nano-Sulfur Modified Graphene Oxide/Silicon Carbide. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 22053–22063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Fu, X.; Luo, M.; Xie, Z.; Huang, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, G.; Wu, J. Synergistic Effect of CB and GO/CNT Hybrid Fillers on the Mechanical Properties and Fatigue Behavior of NR Composites. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 10573–10581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodal, M.; Yazıcı Çakır, N.; Yıldırım, R.; Karakaya, N.; Özkoç, G. Improved Heat Dissipation of NR/SBR-Based Tire Tread Compounds via Hybrid Fillers of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube and Carbon Black. Polymers 2023, 15, 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Teng, J.; Xu, J.; Ying, H.; Xiong, W.; Zhu, C. Preparation of a Precursor Complex Containing Lignin/Silica Hybrids and Styrene-Butadiene Rubber via a One-Pot Method to Fabricate High-Performance Rubber Materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 313, 144195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, S.; Yang, L.; Liu, B.; Xie, S.; Qi, R.; Zhan, Y.; Xia, H. Graphene-Based Hybrid Fillers for Rubber Composites. Molecules 2024, 29, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

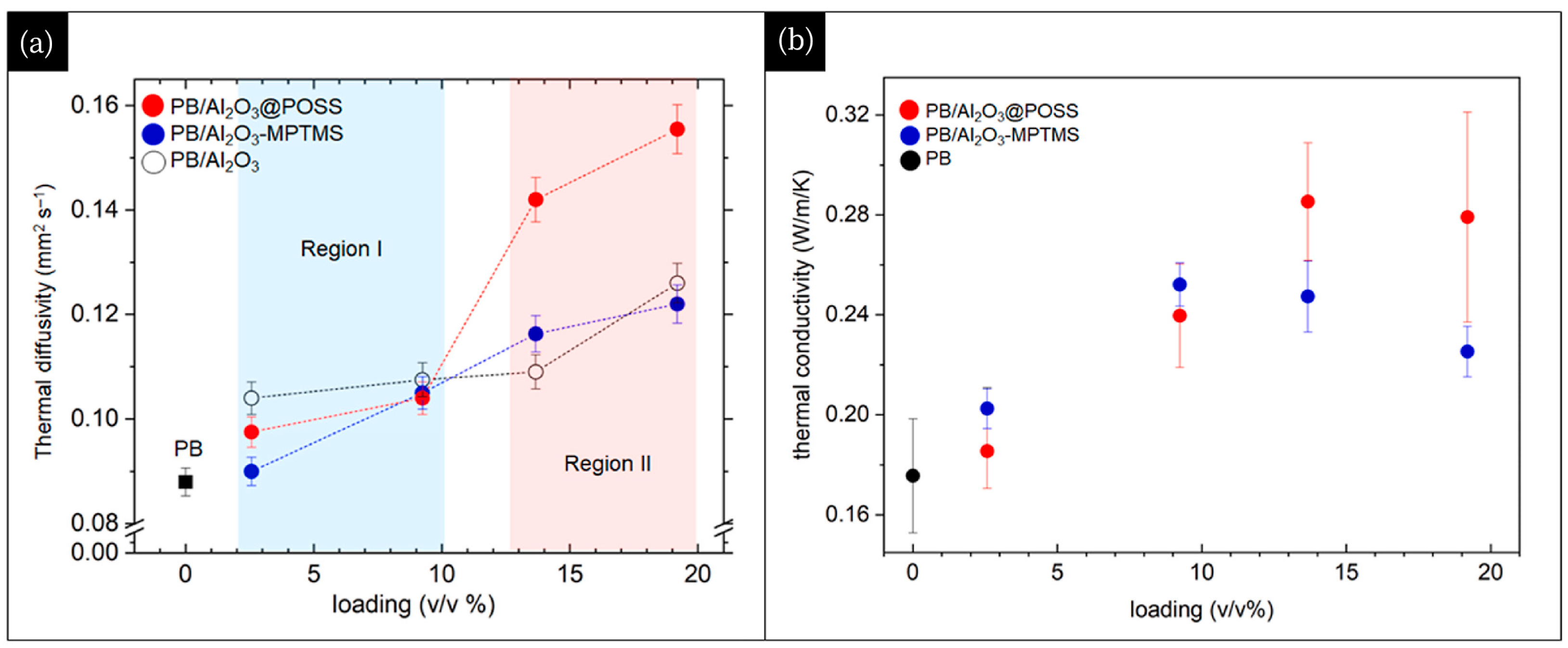

- Mirizzi, L.; D’Arienzo, M.; Nisticò, R.; Fredi, G.; Diré, S.; Callone, E.; Dorigato, A.; Giannini, L.; Guerra, S.; Mostoni, S.; et al. Al2O3 Decorated with Polyhedral Silsesquioxane Units: An Unconventional Filler System for Upgrading Thermal Conductivity and Mechanical Properties of Rubber Composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 236, 109977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, M.; Messori, M. A Comprehensive Overview of Conventional and Bio-Based Fillers for Rubber Formulations Sustainability. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 27, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Debnath, S.C.; Potiyaraj, P. A Review on Recent Trends and Future Prospects of Lignin Based Green Rubber Composites. J. Polym. Environ. 2020, 28, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Kian, L.K.; Jawaid, M.; Khan, A.A.P.; Marwani, H.M.; Alotaibi, M.M.; Asiri, A.M. Preparation and Characterization of Lignin/Nano Graphene Oxide/Styrene Butadiene Rubber Composite for Automobile Tyre Application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirizzi, L.; Carnevale, M.; D’Arienzo, M.; Milanese, C.; Di Credico, B.; Mostoni, S.; Scotti, R. Tailoring the Thermal Conductivity of Rubber Nanocomposites by Inorganic Systems: Opportunities and Challenges for Their Application in Tires Formulation. Molecules 2021, 26, 3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Johnson, D.; Smith, R.E.; Felicelli, S.D. Numerical Evaluation of the Temperature Field of Steady-State Rolling Tires. Appl. Math. Model. 2014, 38, 1622–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, R.; Kaliske, M. Thermo-Mechanically Coupled Investigation of Steady State Rolling Tires by Numerical Simulation and Experiment. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2015, 68, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.H.; Yu, A.B.; Lu, G.Q. Multiscale Modeling and Simulation of Polymer Nanocomposites. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008, 33, 191–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Fu, B.; Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, L. Increasing the Thermal Conductivity of Styrene Butadiene Rubber: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulation. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 23394–23402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Cai, F.; Luo, Y.; Ye, X.; Zhang, C.; Wu, S. The Interphase and Thermal Conductivity of Graphene Oxide/Butadiene-Styrene-Vinyl Pyridine Rubber Composites: A Combined Molecular Simulation and Experimental Study. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 188, 107971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Lin, X.; Zheng, L.; Li, Z.; Lu, S. Preparation and Molecular Simulation of Hyper-Dispersant Modified BN Filled Natural Rubber Thermally Conductive Composite. Polymer 2025, 317, 127935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhen, C.; Tao, W.; Luo, Y.; Wang, X. Synergistic Effect of Dual-Modification Strategy on Thermal Conductivity and Thermal Stability of h-BN/Silicone Rubber Composites: Experiments and Simulations. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 163, 108716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Yang, Z.; Jia, H.; Wen, Y.; Luo, Y.; Ding, L. Integration of Experimental Methods and Molecular Dynamics Simulations for a Comprehensive Understanding of Enhancement Mechanisms in Graphene Oxide (GO)/Rubber Composites. J. Polym. Res. 2023, 30, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Du, J.; Zhu, X.; Ng, K.M. Computer-Aided Polymer Design: Integrating Group Contribution and Molecular Dynamics. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 15542–15552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fillers | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Silver | 450 | [41] |

| Copper | 483 | [41] |

| Aluminum | 204 | [41] |

| Nickel | 158 | [41] |

| Gold | 345 | [41] |

| Zinc | 121 | [26] |

| Iron | 80 | [26] |

| Zinc oxide | 30 | [26] |

| Beryllium oxide | 270 | [42,43] |

| Aluminum oxide | 20–29 | [41] |

| Aluminum nitride | 320 | [26] |

| Silicon nitride | >150 | [44] |

| Silicon carbide | 80 | [26] |

| Boron nitride | 250–300 | [41] |

| BN nanosheets | 751 (λ||) * | [45] |

| Carbon black | 6–174 | [41] |

| Carbon Nanotubes | 2000–6000 | [41] |

| Carbon fiber | 1200 | [46] |

| Diamond | 2000 | [41] |

| Graphite | 100–400 (λ||) | [41] |

| Graphene | 600–2800 (λ||) | [47] |

| Molybdenum sulfide | 34.5 | [48] |

| Hybrid Fillers | Rubber Matrix | Filler Loading | Filler Type | λ1 | λ2 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCNT@RGO | SBR | 3 wt% | 1D+2D | 0.23 | 0.45 | [129] |

| Al2O3@TA-Fe3+@Ag | NBR | 50 vol% | 0.15 | 0.90 | [130] | |

| Al2O3-PRd@BN-PRd | ENR | 30 vol% | 0D+2D | 0.1390 | 0.5147 | [131] |

| rGO-PDA@ Al2O3 | NR | 25 vol% | 0D+2D | 0.1726 | 0.863 | [132] |

| SiCNWs@rGO | SR | 1.84 vol% | 1D+2D | 1.66 | 2.74 | [133] |

| Al2O3-PDA@Ag | NR | 10 vol% | 0.10 | 0.20 | [134] | |

| CF@ Al2O3 | SR | 25 vol% | 0D+1D | - | 9.6 | [135] |

| Zn@ZnO@CF | SR | 60 phr | 0.48 | 1.53 | [136] | |

| rGO@ Al2O3 | NR | 18 vol% | 0D+2D | 0.168 | 0.514 | [137] |

| BN@rGO | NR | 4.9 vol% | 0.18 | 1.28 (λ||) | [138] | |

| Al2O3@PCPA@GO | XNBR | 30 vol% | 0D+2D | 0.16 | 0.48 | [139] |

| AlN@CNT(1:1) | NR | 12 vol% | 1D+2D | - | 0.502 | [140] |

| CF@BN | SR | CF30 vol%BN10 vol% | 1D+2D | - | 2.789 | [141] |

| T-rGO@BN | PDMS | 14.3 vol% | - | 1.41 | [142] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Dong, T.; Li, S.; Yin, H. Research Progress of Thermally Conductive Rubber Composites for Tire Heat Dissipation. Polymers 2025, 17, 3197. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233197

Chang S, Wang Z, Wang X, Dong T, Li S, Yin H. Research Progress of Thermally Conductive Rubber Composites for Tire Heat Dissipation. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3197. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233197

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Suling, Zhihao Wang, Xiaoyao Wang, Tingxi Dong, Si Li, and Haishan Yin. 2025. "Research Progress of Thermally Conductive Rubber Composites for Tire Heat Dissipation" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3197. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233197

APA StyleChang, S., Wang, Z., Wang, X., Dong, T., Li, S., & Yin, H. (2025). Research Progress of Thermally Conductive Rubber Composites for Tire Heat Dissipation. Polymers, 17(23), 3197. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233197