Facile Preparation of Graphene Oxide-Enhanced Highly Crystalline Polyglycolic Acid Under Low-Temperature Crystallization Using Tin(II) 2-Ethylhexanoate and Its Application in Biomaterials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

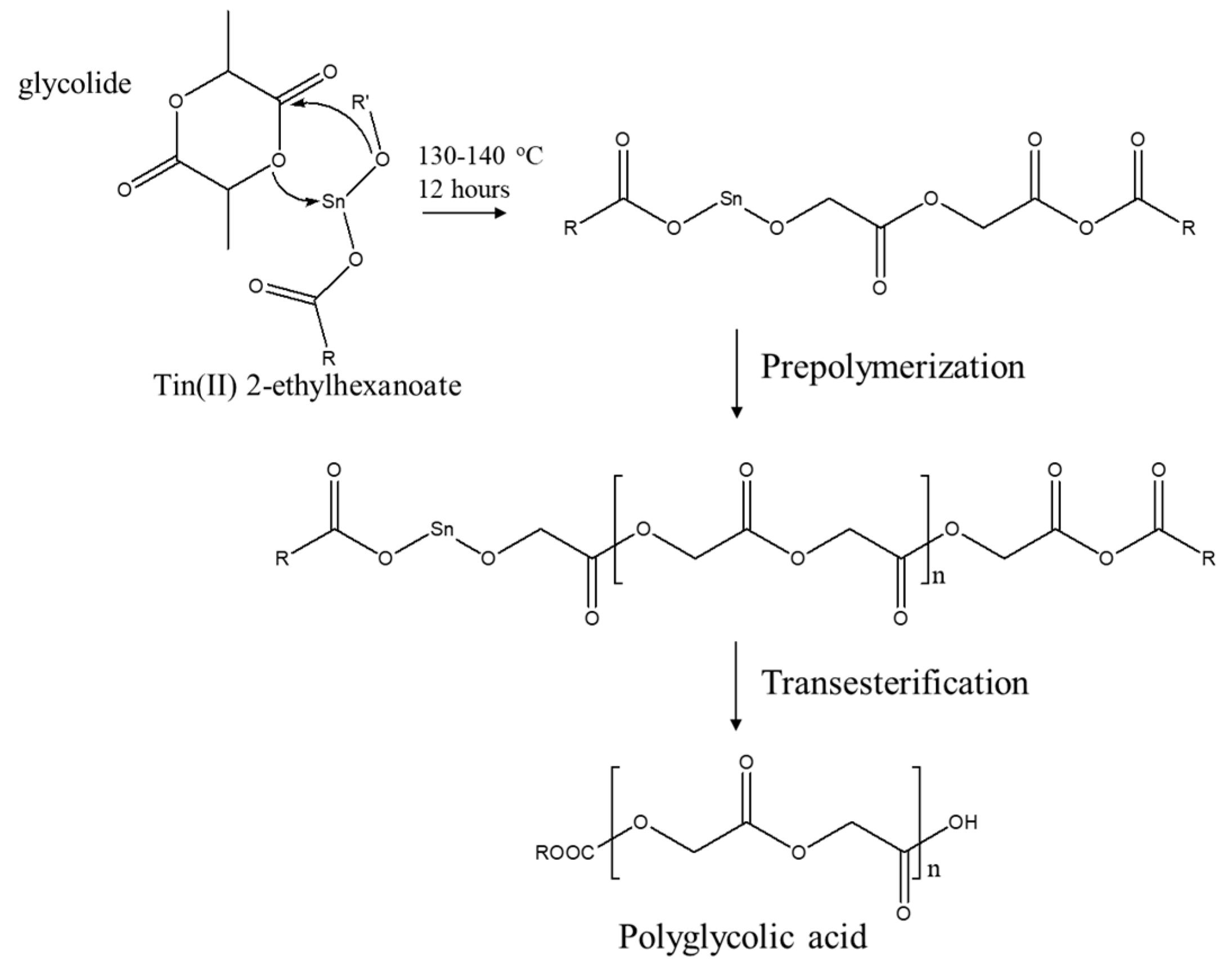

2.2. Ring-Opening Polymerization of Polyglycolic Acid

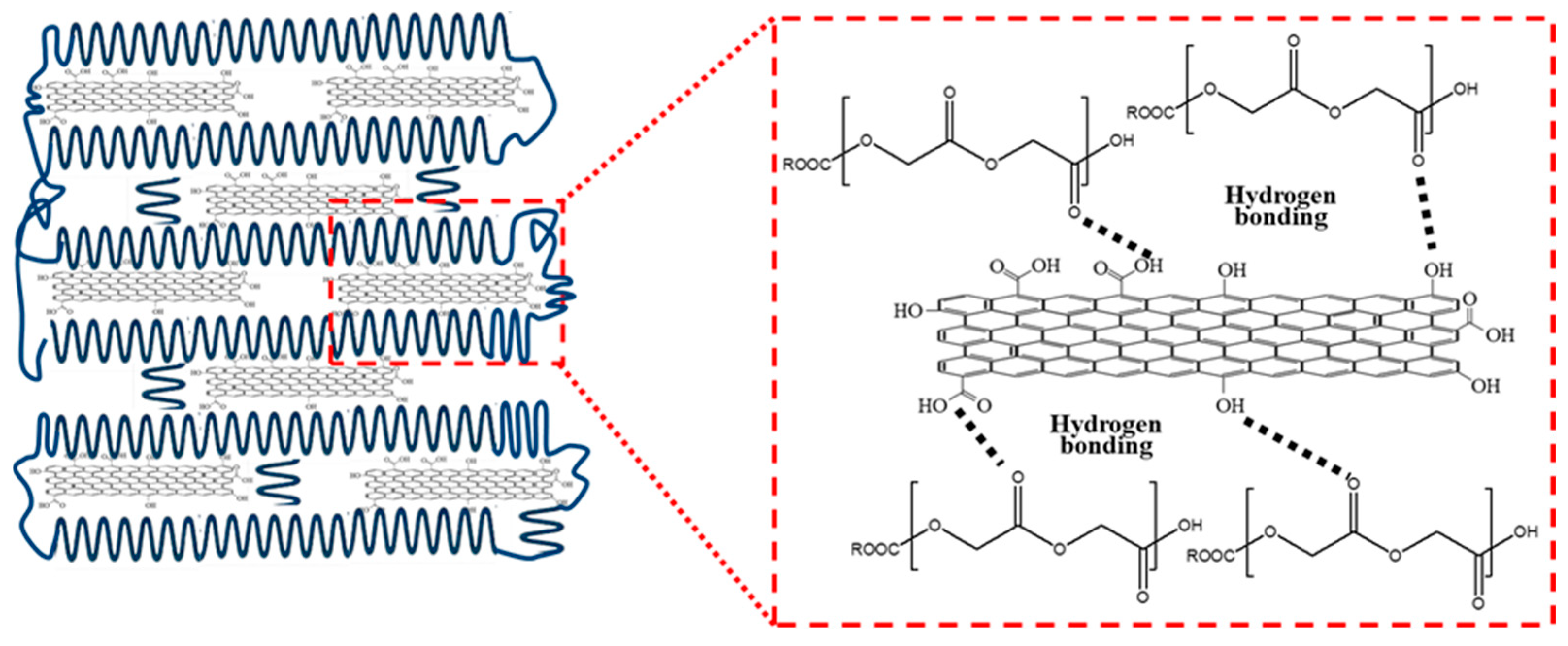

2.3. Fabrication of GO/PGA Nanocomposites

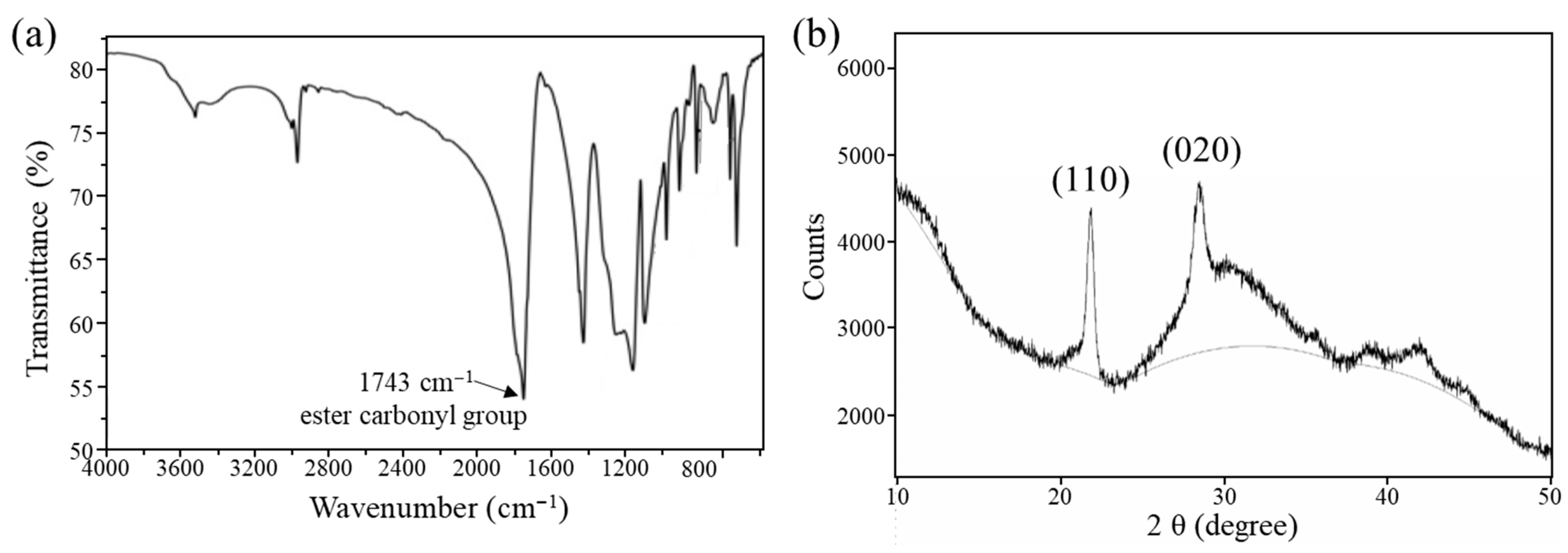

2.4. Structural Characterization by FTIR

2.5. XRD Analysis

2.6. DSC Thermal Analysis

- (A)

- Equilibration: sample stabilized at 25 °C for 1 min.

- (B)

- Heating: 25 → 235 °C at 10 °C min−1.

- (C)

- Isothermal erase: 235 °C for 5 min to remove the thermal history.

- (D)

- Cooling: 235 → 25 °C at 30 °C min−1.

- (E)

- Re-equilibration at 25 °C for 1 min.

- (F)

- Heating: 25 → 235 °C at 5 °C min−1.

- (A)–(C) followed the same melting and erase steps as above.

- (D) Rapid cooling: 235 °C → T1–T5 at 30 °C min−1.

- (E) Isothermal hold: 90 min at T1–T5.

- (F) Heating: T1–T5 → 235 °C at 5 °C min−1.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Characterization of Polyglycolic Acid Synthesized by Ring-Opening Polymerization

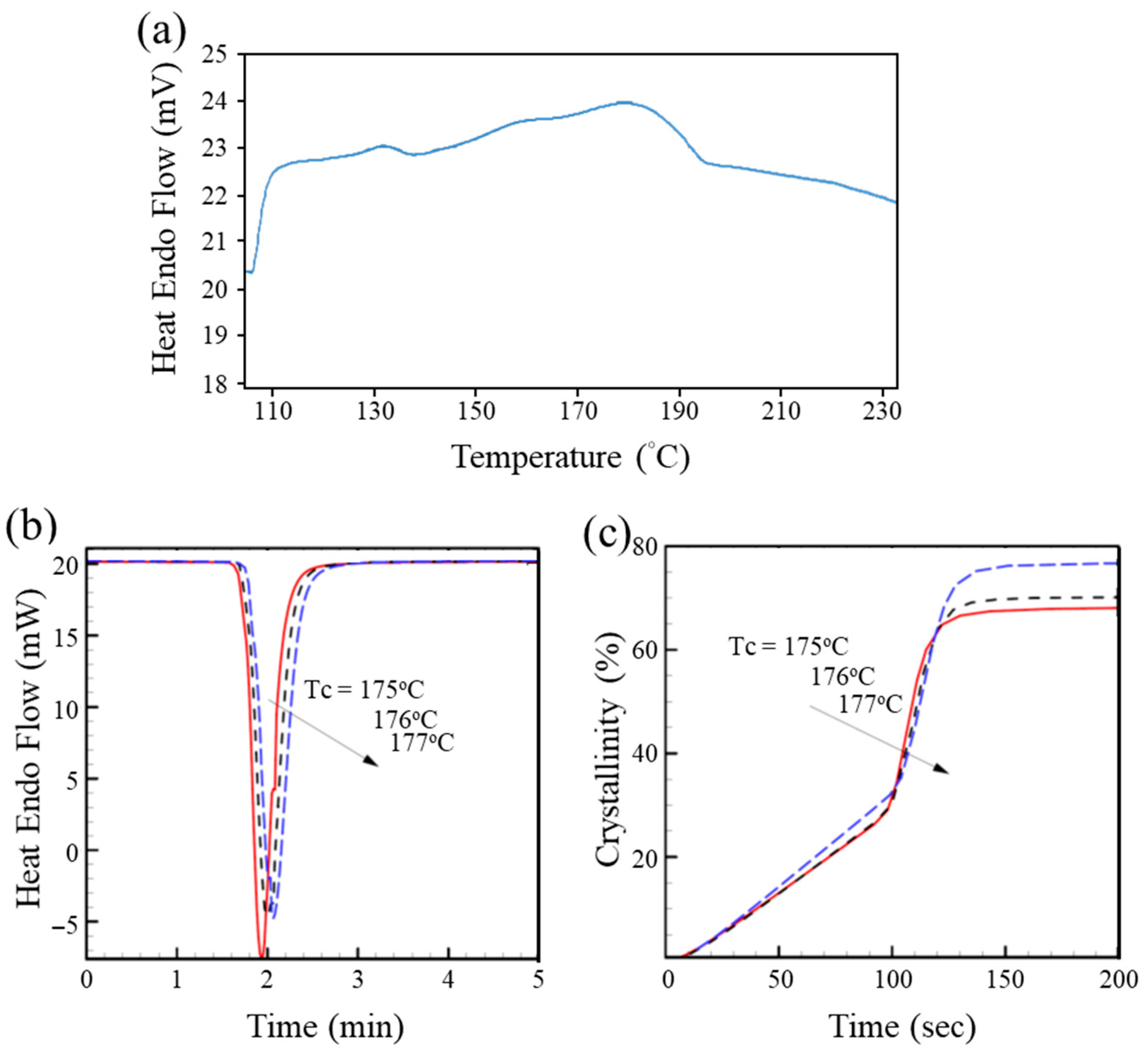

3.2. DSC Analysis—Non-Isothermal Crystallization

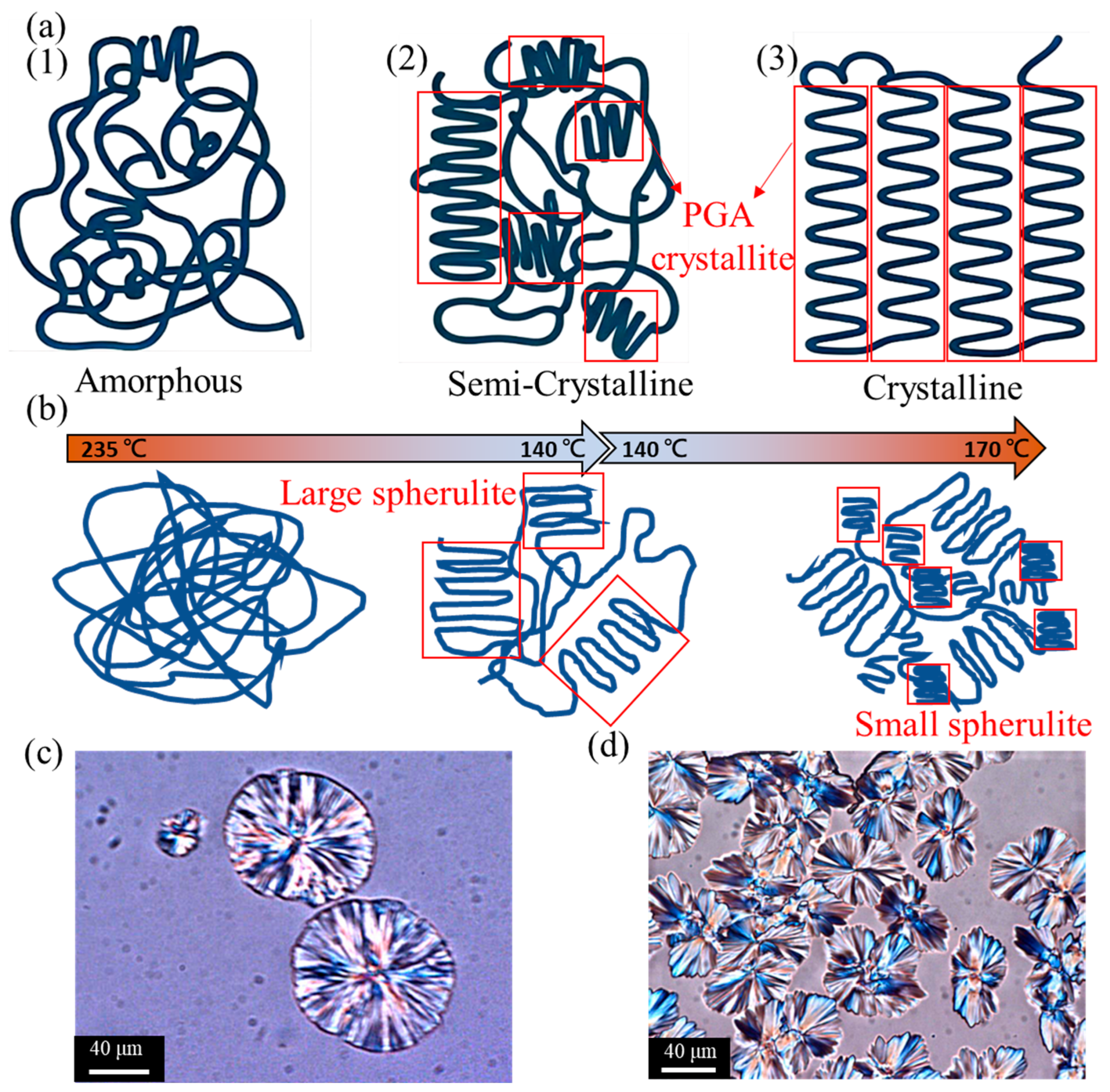

3.3. Morphology of Polyglycolic Acid in Different Crystallization States Using POM Crystal Image Analysis

3.4. Crystallization Behavior Regression Based on the Avrami Equation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.W.; Huang, B.S.; Chang, C.H.; Chiu, C.W. Advanced electrospun AgNPs/rGO/PEDOT:PSS/TPU nanofiber electrodes: Stretchable, self-healing, and perspiration-resistant wearable devices for enhanced ECG and EMG monitoring. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2023, 6, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.W.; Huang, C.Y.; Li, J.W.; Li, C.L. Flexible hybrid electronics nanofiber electrodes with excellent stretchability and highly stable electrical conductivity for smart clothing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 42441–42453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Chiu, C.W. Facile fabrication of a stretchable and flexible nanofiber carbon film-sensing electrode by electrospinning and its application in smart clothing for ECG and EMG monitoring. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Lee, J.C.M.; Chuang, K.C.; Chiu, C.W. Photocured, highly flexible, and stretchable 3D-printed graphene/polymer nanocomposites for electrocardiography and electromyography smart clothing. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 176, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Chen, H.F.; Liu, Y.Z.; Wang, J.H.; Lu, M.C.; Chiu, C.W. Photocurable 3D-printed AgNPs/graphene/polymer nanocomposites with high flexibility and stretchability for ECG and EMG smart clothing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sudhakara, P.; Singh, J.; Ilyas, R.; Asyraf, M.; Razman, M. Critical review of biodegradable and bioactive polymer composites for bone tissue engineering and drug delivery applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, R. Biomaterials in drug delivery and tissue engineering: One laboratory’s experience. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Mujawar, M.; Kaushik, A. State-of-art functional biomaterials for tissue engineering. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, J.; Mura, S.; Brambilla, D.; Mackiewicz, N.; Couvreur, P. Design, functionalization strategies and biomedical applications of targeted biodegradable/biocompatible polymer-based nanocarriers for drug delivery. Chem. Rev. 2013, 42, 1147–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Parrish, B.; Emrick, T. Soluble camptothecin derivatives prepared by click cycloaddition chemistry on functional aliphatic polyesters. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007, 18, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, N.; Mondal, A. Synthesis, properties, environmental degradation, processing, and applications of polylactic acid (PLA): An overview. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 11421–11457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, S.-R.; Zhou, S.-Y.; Yang, H.-R.; Xu, L.; Zhong, G.-J.; Xu, J.-Z.; Li, Z.-M.; Tao, X.-M.; Mai, Y.-W. Cold crystallization behavior of poly(lactic acid) induced by poly(ethylene glycol)-grafted graphene oxide: Crystallization kinetics and polymorphism. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 258, 110871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-W.; Cheng, C.-C.; Chiu, C.-W. Advances in multifunctional polymer-based nanocomposites. Polymers 2024, 16, 3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciou, Y.-S.; Hsu, C.-K.; Li, J.-W.; Chen, J.-X.; Wang, J.-H.; Chiu, C.-W. Nanocomposite fabrics of GNP/BN/TPU with high thermal conductivity, breathability, stretchability, and excellent comfort for smart cooling wearables. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-X.; Li, J.-W.; Tsai, W.-Y.; Lee, L.-X.; Chiu, C.-W. High-performance piezoelectric flexible nanogenerators based on GO and polydopamine-modified ZnO/P(VDF-TrFE) for human motion energy capture, shared bicycle nanoenergy harvesting, and self-powered devices. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 694, 137666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-X.; Li, J.-W.; Jiang, Z.-J.; Chiu, C.-W. Polymer-assisted dispersion of reduced graphene oxide in electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride nanofibers for enhanced piezoelectric monitoring of human body movement. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-W.; Huang, C.-Y.; Zhou, B.-H.; Hsu, M.-F.; Chung, S.-F.; Lee, W.-C.; Tsai, W.-Y.; Chiu, C.-W. High stretchability and conductive stability of flexible hybrid electronic materials for smart clothing. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 12, 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-W.; Wu, M.-T.; Lin, C.-L.; Li, J.-W.; Huang, C.-Y.; Soong, Y.-C.; Lee, J.C.-M.; Sanchez, W.A.L.; Lin, H.-Y. Adsorption performance for reactive blue 221 dye of β-chitosan/polyamine functionalized graphene oxide hybrid adsorbent with high acid–alkali resistance stability in different acid–alkaline environments. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-W.; Lee, Y.-C.; Ou, G.-B.; Cheng, C.-C. Controllable 3D hot-junctions of silver nanoparticles stabilized by amphiphilic tri-block copolymer/graphene oxide hybrid surfactants for use as surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrates. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 2935–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oca, H.; Wilson, J.; Penrose, A.; Langton, D.; Dagger, A.; Anderson, M.; Farrar, D.; Lovell, C.; Ries, M.; Ward, I.; et al. Liquid-crystalline aromatic-aliphatic copolyester bioresorbable polymers. Biomaterials 2010, 30, 7599–7605. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Du, M.; Yang, S.; Wei, W.; Chang, G. Recyclable crosslinked high-performance polymers via adjusting intermolecular cation-π interactions and the visual detection of tensile strength and glass transition temperature. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2018, 39, e1800031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.K.; Fischer, A.M.; Frey, H. Poly(glycolide) multi-arm star polymers: Improved solubility via limited arm length. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010, 6, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyoob, M.; Lee, D.; Kim, J.; Nam, S.; Kim, Y. Synthesis of poly(glycolic acids) via solution polycondensation and investigation of their thermal degradation behaviors. Fibers Polym. 2017, 18, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Jang, Y.; Kim, E.; Li, T.; Kim, S. Tissue-engineered vascular graft based on a bioresorbable tubular knit scaffold with flexibility, durability, and suturability for implantation. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 1108–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, T.; Fouet, A. Poly-gamma-glutamate in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 60, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmschlag, B.; Steurer, X.; Putri, S.; Fukusaki, E.; Blank, L. Tailor-made poly-γ-glutamic acid production. Metab. Eng. 2019, 55, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayyoob, M.; Yang, X.; Park, H.; Park, S.; Kim, J.; Nam, S.; Kim, Y. Synthesis of bioresorbable poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)s through direct polycondensation: An economical substitute for the synthesis of polyglactin via ROP of lactide and glycolide. Fibers Polym. 2019, 20, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanko, V.; Sahin, I.; Sezer, U.; Sezer, S. A versatile method for the synthesis of poly(glycolic acid): High solubility and tunable molecular weights. Polym. J. 2019, 51, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, E.; Fuertès, P.; Cassagnau, P.; Pascault, J.; Fleury, E. Synthesis and rheology of biodegradable poly(glycolic acid) prepared by melt ring-opening polymerization of glycolide. J. Polym. Sci. Pol. Chem. 2009, 47, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kister, G.; Cassanas, G.; Fabrègue, E.; Bardet, L. Vibrational analysis of ring-opening polymerizations of glycolide, L-lactide and D,L-lactide. Eur. Polym. J. 1992, 28, 1273–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Swisher, J.; Meyer, T.; Coates, G. Chirality-Directed Regioselectivity: An approach for the synthesis of alternating poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 4119–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.; Behl, M.; Lendlein, A.; Beuermann, S. Synthesis of high molecular weight polyglycolide in supercritical carbon dioxide. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 35099–35105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, K.; Sogut, O.; Sezer, U. A review on synthesis and biomedical applications of polyglycolic acid. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hongo, C.; Nishino, T. Crystal modulus of poly(glycolic acid) and its temperature dependence. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 5074–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oca, H.; Ward, I.; Chivers, R.; Farrar, D. Structure development during crystallization and solid-state processing of poly(glycolic acid). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 111, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, A.; Arnal, M.; Albuerne, J.; Müller, A. DSC isothermal polymer crystallization kinetics measurements and the use of the Avrami equation to fit the data: Guidelines to avoid common problems. Polym. Test. 2007, 26, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Li, X.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, Q.; Xie, H.; Zheng, Q. Can classic Avrami theory describe the isothermal crystallization kinetics for stereocomplex poly(lactic acid). Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2017, 35, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Hay, J.; Turner, R.; Jenkins, M. The effect of a secondary process on the analysis of isothermal crystallisation kinetics by differential scanning calorimetry. Polymers 2019, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni, A.G. (Ed.) Kinetics of crystal growth using the avrami model and the chemical potential approach. In Kinetic Analysis of Food Systems; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kricheldorf, H.R.; Weidner, S.M.; Meyer, A. About alcohol-initiated polymerization of glycolide and separate crystallization of cyclic and linear polyglycolides. Polymer 2024, 309, 127440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M.; Vert, M. Biodegradation of polyglycolide (PGA). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2002, 75, 413–423. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart, B. Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, S.; Hirose, Y.; Kawaguchi, D.; Tanaka, K.; Takano, A. Lamellar structure and crystallization behavior of biodegradable aliphatic polyesters. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 4822–4830. [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich, B. Thermal Analysis of Polymeric Materials; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, H.; Miyauchi, S. Crystallization behavior and morphology of poly(L-lactide). Polymer 2001, 42, 4463–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez-García, R.; Pérez-Camargo, R.A.; Nogales, A.; Ezquerra, T.A.; Rebollar, E. Thermal analysis and crystallization behavior of biodegradable polyesters. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48509. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, B. The Avrami Equation: Phase Transformations. In The Equations of Materials; Cantor, B., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 180–206. [Google Scholar]

- Punyodom, W.; Limwanich, W.; Meepowpan, P.; Thapsukhon, B. Ring-opening polymerization of ε-caprolactone initiated by Tin(II) octoate/n-hexanol: DSC isoconversional kinetics analysis and polymer synthesis. Des. Monomers Polym. 2021, 24, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultekin, F.; Doğuç, D. Allergic and immunologic reactions to food additives. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2013, 45, 6–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaoming, Z.; Zhaoyang, W.; Jun, W.; Hangzhen, M. Direct synthesis of poly(D,L-lactic acid) by melt polycondensation and its application in drug delivery. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2004, 91, 2143–2150. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, K.; Taniguchi, I.; Miyamoto, M.; Kimura, Y. Melt/solid polycondensation of glycolic acid to obtain high-molecular-weight poly(glycolic acid). Polymer 2000, 41, 8725–8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Tc (°C) | Final Crystallinity a (%) | n b | Kc c (min−n) | t1/2 d (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 175 | 68 | 1.47 | 6.3 × 10−4 | 111 |

| B | 176 | 70 | 1.50 | 5.6 × 10−4 | 115 |

| C | 176.5 | 74 | 1.51 | 5.6 × 10−4 | 112 |

| D | 177 | 77 | 1.48 | 6.1 × 10−4 | 116 |

| E | 177.5 | 68 | 1.41 | 9.0 × 10−4 | 111 |

| Number | Tc (°C) | GO (wt%) | Tm (°C) | ΔHf (J g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 175 | 0 | Tm1 = 206.2 ± 2.8 | 32.00 ± 4.2 |

| Tm2 = 218.6 ± 2.4 | 44.94 ± 3.8 | |||

| B | 176 | 0 | Tm1 = 208.8 ± 3.2 | 35.08 ± 2.3 |

| Tm2= 219.2 ± 3.0 | 45.16 ± 2.4 | |||

| C | 176.5 | 0 | Tm1 = 207.1 ± 1.2 | 37.25 ± 5.6 |

| Tm2 = 219.0 ± 1.6 | 49.26 ± 4.9 | |||

| D | 177 | 0 | Tm1 = 206.3 ± 2.1 | 38.18 ± 3.2 |

| Tm2 = 218.1 ± 2.3 | 49.78 ± 3.8 | |||

| E | 177.5 | 0 | Tm1 = 205.3 ± 1.5 | 36.31 ± 4.1 |

| Tm2 = 217.3 ± 1.6 | 51.75 ± 3.5 | |||

| F | 177 | 1 | Tm1 = 207.2 ± 1.2 | 37.23 ± 2.3 |

| Tm2 = 219.1 ± 1.4 | 51.36 ± 2.8 | |||

| G | 177 | 2 | Tm1 = 209.4 ± 1.3 | 38.46 ± 1.5 |

| Tm2 = 220.0 ± 1.6 | 52.18 ± 2.6 | |||

| H | 177 | 3 | Tm1 = 208.1 ± 2.1 | 36.12 ± 3.2 |

| Tm2 = 218.7 ± 2.3 | 51.35 ± 2.3 |

| Number | Synthesis Methodology | Reaction Conditions | Reaction Time | Catalyst | Tm (°C) | Crystallinity (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Melt/solid polycondensation | 190 °C, 150 ⟶ 30 (mmHg) 190 °C (N2 system) | 5 h (liq. Oligomer) 20 h (powder) | SnCl2 d | - | 40 | [50] |

| 2 | Melt/solid polycondensation | 190 °C, 150 ⟶ 30 (mmHg) Melting at 230 °C, cooling to 190 °C | 5 h (liq. Oligomer) 20 h | SnCl2 d | - | 39 | [50] |

| 3 | Melt ROP b (1-dodecanol initiator) | Melting monomers at 95 °C 210/235 °C | - | Sn(Oct)2 | 222 | - | [48] |

| 4 | Melt ROP b (1,4-butandiol initiator) | Melting monomers at 95 °C 210/235 °C | - | Sn(Oct)2 | 222 | - | [48] |

| 5 | Melt/solid polycondensation | 220 °C, 150 ⟶ 100 ⟶ 30 (Torr) | 7 h | Zinc acetate dihydrate | 229 | 51 | [51] |

| 6 | Solution polymerization (diphenylsulfone solvent) | 170–200 °C, 100 (Torr) | 20 h | MSA a | 229 | - | [23] |

| 7 | ROP b | 130–140 °C, 100 (Torr) | 12 h | Sn(Oct)2 e | 218 | 68–77 | This study |

| 8 | ROP with GO (2 wt%) b,c | 130–140 °C, 100 torr, GO dispersed in HFIP and added to PGA prior to drying c | 12 h | Sn(Oct)2 e | 220 | 79 | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.-F.; Li, J.-W.; Ou, K.-J.; Yu, S.-Y.; Wang, J.-H.; Cheng, C.-C.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Nien, Y.-H.; Kuo, C.-F.J.; Chiu, C.-W. Facile Preparation of Graphene Oxide-Enhanced Highly Crystalline Polyglycolic Acid Under Low-Temperature Crystallization Using Tin(II) 2-Ethylhexanoate and Its Application in Biomaterials. Polymers 2025, 17, 3181. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233181

Chen H-F, Li J-W, Ou K-J, Yu S-Y, Wang J-H, Cheng C-C, Tseng Y-H, Nien Y-H, Kuo C-FJ, Chiu C-W. Facile Preparation of Graphene Oxide-Enhanced Highly Crystalline Polyglycolic Acid Under Low-Temperature Crystallization Using Tin(II) 2-Ethylhexanoate and Its Application in Biomaterials. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3181. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233181

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Ho-Fu, Jia-Wun Li, Kuo-Jen Ou, Shu-Yuan Yu, Jui-Hsin Wang, Chih-Chia Cheng, Yao-Hsuan Tseng, Yu-Hsun Nien, Chung-Feng Jeffrey Kuo, and Chih-Wei Chiu. 2025. "Facile Preparation of Graphene Oxide-Enhanced Highly Crystalline Polyglycolic Acid Under Low-Temperature Crystallization Using Tin(II) 2-Ethylhexanoate and Its Application in Biomaterials" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3181. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233181

APA StyleChen, H.-F., Li, J.-W., Ou, K.-J., Yu, S.-Y., Wang, J.-H., Cheng, C.-C., Tseng, Y.-H., Nien, Y.-H., Kuo, C.-F. J., & Chiu, C.-W. (2025). Facile Preparation of Graphene Oxide-Enhanced Highly Crystalline Polyglycolic Acid Under Low-Temperature Crystallization Using Tin(II) 2-Ethylhexanoate and Its Application in Biomaterials. Polymers, 17(23), 3181. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233181