Incorporation of Natural Biostimulants in Biodegradable Mulch Films for Agricultural Applications: Ecotoxicological Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plastics and Additives

2.2. Biological Material

2.3. Obtaining Functionalized Film

2.4. Preparation of Samples for Ecotoxicity Assays and Evaluation of Mulching Film Residues by Py-GC/MS

2.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.6. Procedures for Biological Testing

2.6.1. Testing on Terrestrial Higher Plants

2.6.2. Earthworm Test

2.6.3. Microalgae Test

2.6.4. Sea Urchin Embryo Test

2.7. Procedure for Analyzing Mulching Film Residue

2.7.1. Py-GC/MS Method

2.7.2. Sample Preparation

2.7.3. Identification of Polymers

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

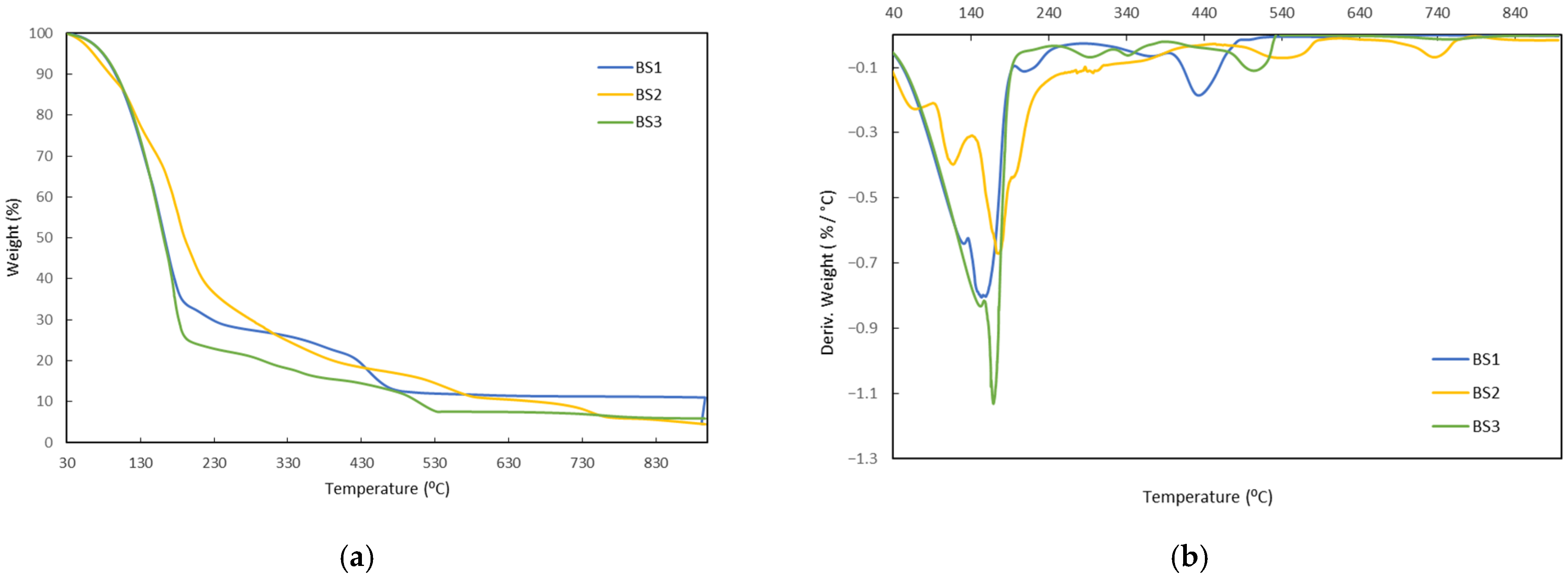

3.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

3.2. Biological Tests

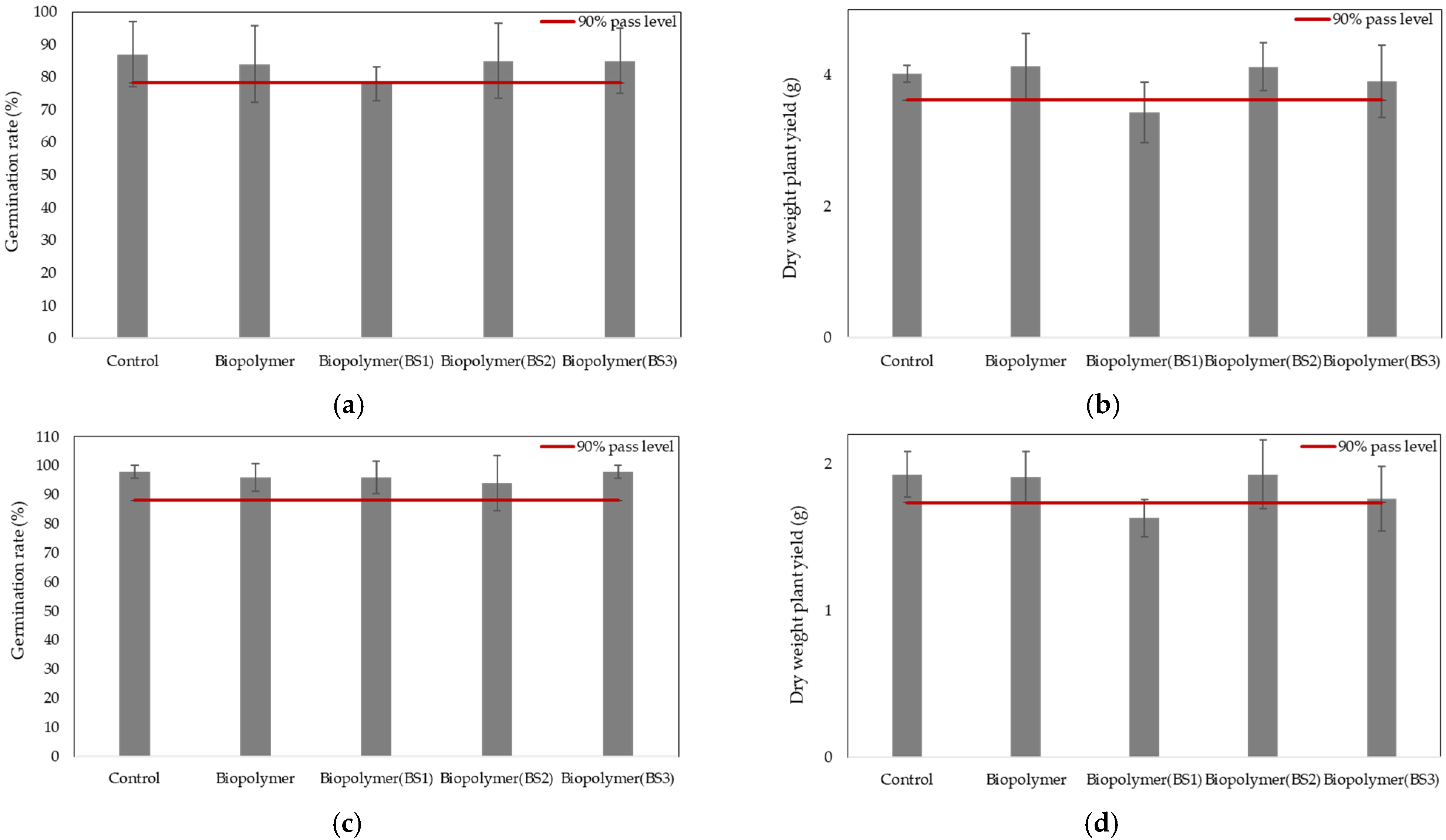

3.2.1. Germination Rate and Plant Biomass

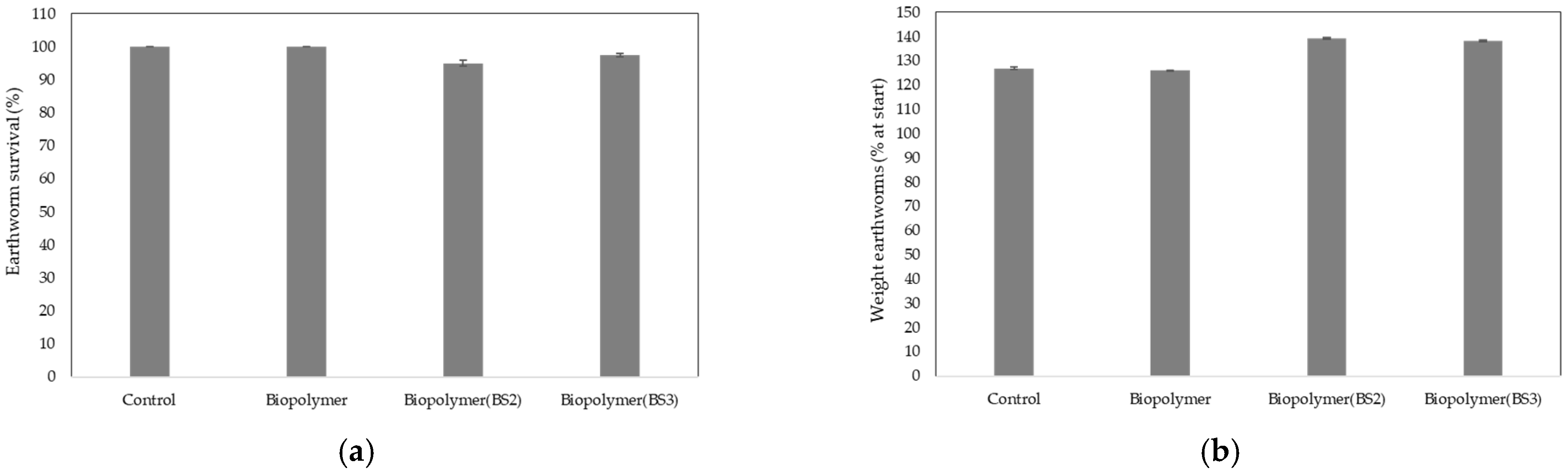

3.2.2. Mortality Rate and Body Mass of Earthworms

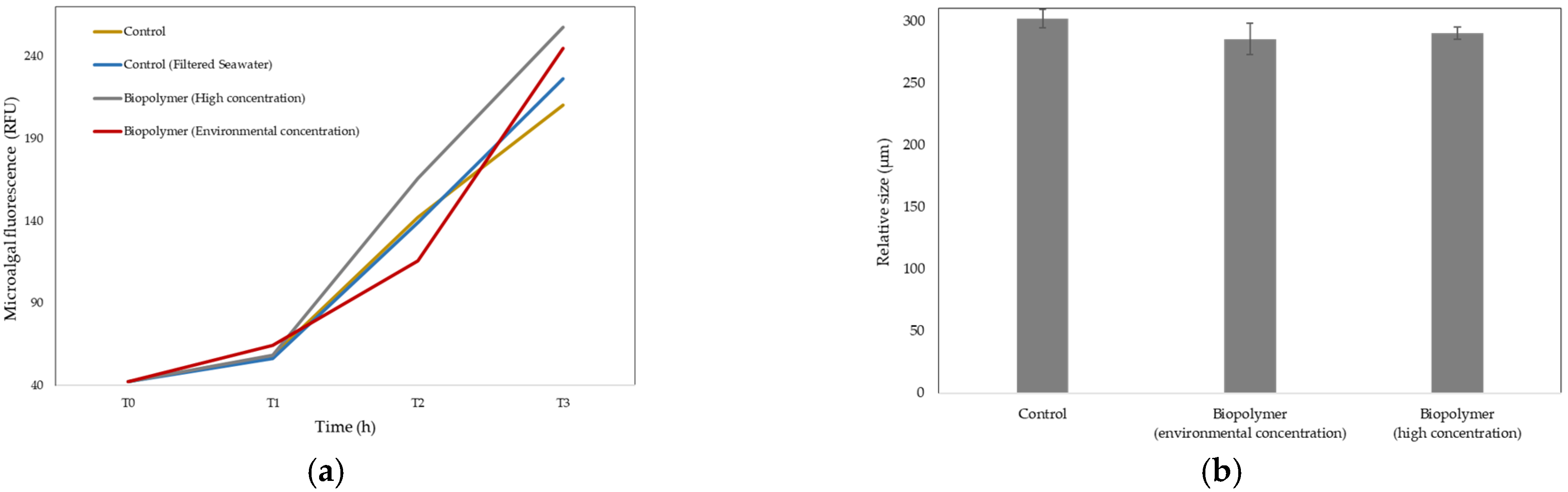

3.2.3. Growth Rate in Microalgae

3.2.4. Growth Rate in Sea Urchin Embryos

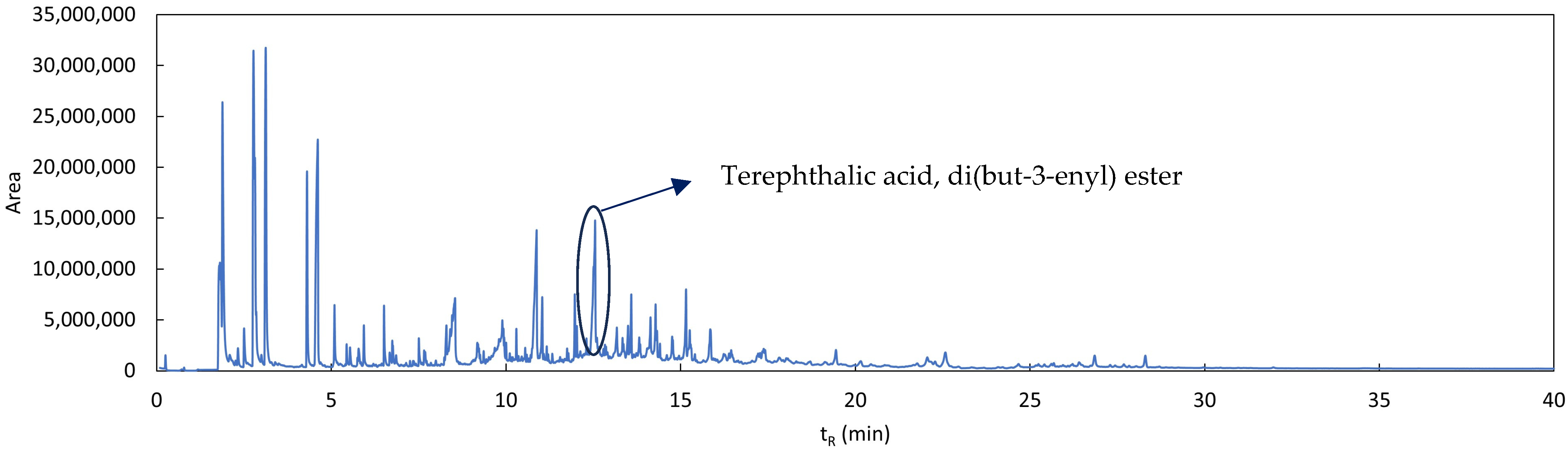

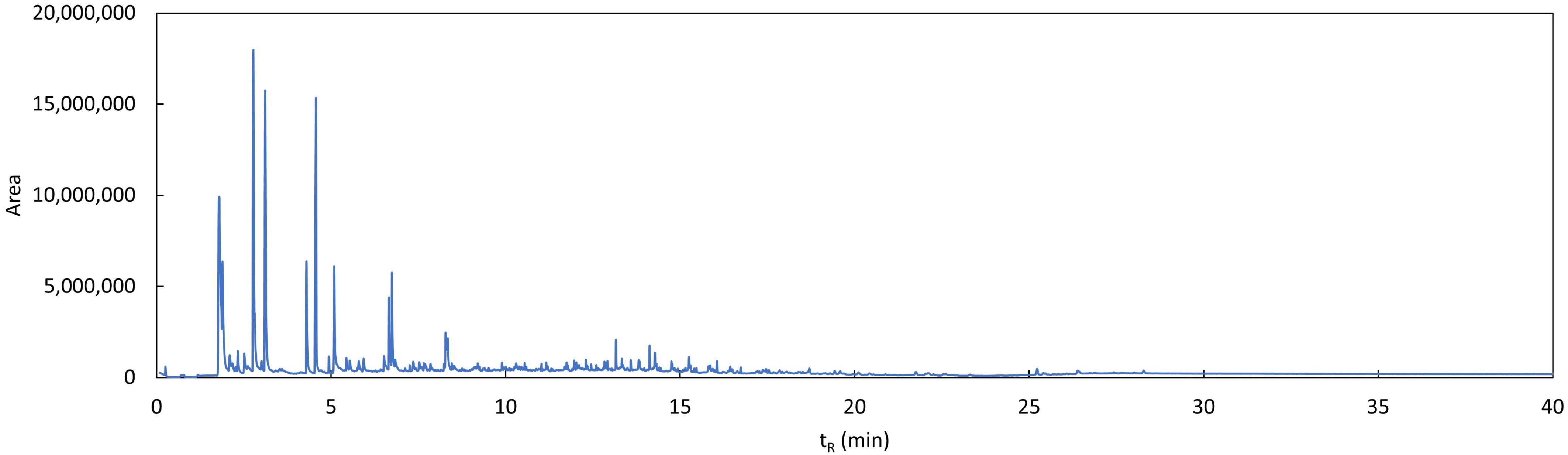

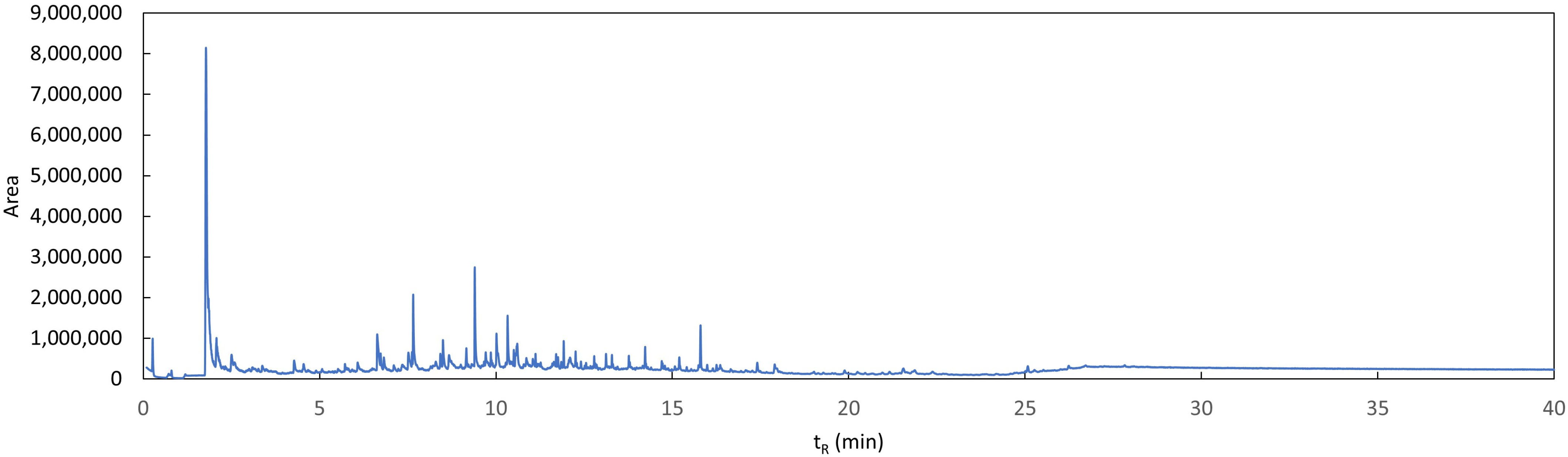

3.3. Study of Degradation Compounds in Mulch Films

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The processing results demonstrated that it was possible to incorporate the commercial biostimulants into the biopolymer matrix through stable and reproducible operations, with no issues during twin-screw extrusion and no exudation of the biostimulant in the blown film. The TGA profiles showed that the main degradation events involving significant mass loss of the biostimulants start above 180–200 °C, whereas matrix processing takes place within the 130–150 °C range. Therefore, these data support that no major thermal degradation of the biostimulants occurs during compounding and extrusion, beyond the expected release of water and low-boiling volatiles or the occurrence of minor chemical modifications that do not involve detectable mass loss. Overall, the results confirm the feasibility of producing biodegradable films functionalized with natural biostimulants without compromising their processability.

- The results of the ecotoxicological tests in terrestrial environments demonstrated that exposure of higher plants to the residues of the functionalized biodegradable mulching films did not produce any adverse effects, except for the film functionalized with BS1, which was therefore excluded from this application. Regarding the earthworm bioassays, no acute adverse effects were observed. In aquatic environments, the results obtained from the microalgae fluorescence study showed no adverse effects of the unfunctionalized film residue on this aquatic organism. Likewise, the results from the sea urchin larval bioassay suggested no evident acute ecotoxicological risk under the experimental conditions tested. This research indicates that the residues from the plastic samples derived from biodegradable mulching films intended for agricultural use did not show adverse effects on organisms that are representative of the two end-of-life scenarios for this plasticulture product. Additionally, the findings of this study highlight the need for long-term studies to assess potential chronic effects and further research to enable a comprehensive risk evaluation; for example, based on studies of the evolution of active compounds in soil, it would be interesting to conduct ecotoxicological tests in aquatic environments to assess the potential environmental impact of natural biostimulants.

- To evaluate the presence of residues at the end of incubation, soil substrate samples were prepared with simulated plastic residue at a proportion of 1% (according to UNE-EN 17033), which had previously been micronized. The soil sample containing the micronized film was subjected to an incubation period of 120 days. The results showed that, at the beginning of the experiment, the biopolymer was present at a concentration of 0.004 ± 0.002% in the sample. After 60 and 120 days, the analysis was repeated, and the biopolymer concentration was found to be below the LOD. This result indicates that the biopolymer undergoes very rapid degradation in the terrestrial environment and that, after 60 days, no film residues were detected.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| % | Percentage |

| °C | Degrees Celsius |

| µL | Microliter |

| µm | Micrometer |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| APE | Agriculture Plastic Environment |

| AVG | Average |

| BDMs | Biodegradable Plastic Mulches |

| BS1 | Biostimulant based on algae extracts |

| BS2 | Biostimulant based on essential amino acids |

| BS3 | Biostimulant based on lignosulfonates |

| cm | Centimeter |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CAP | Common Agricultural Policy |

| DOA | Dibutyl phthalate Oil Absorption |

| DTG | Derivative Thermogravimetry |

| EU | European Union |

| g | Gram |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| h | Hour |

| i.d. | Interior Diameter |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| L | Liter |

| L/D | Length–Diameter |

| LOD | Detection Limit |

| LOQ | Quantification Limit |

| Ltd. | Limited |

| m | Meter |

| mg | Milligram |

| min | Minutes |

| mL | Milliliter |

| mm | Millimeter |

| MPs | Microplastics |

| NaI | Sodium Iodide |

| NH3 | Ammonia |

| NW | Northwest |

| nm | Nanometer |

| Ø | Diameter |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PBAT | Poly(butylene) terephthalate |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| Py-GC/MS | Pyrolysis–Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| RFU | Relative Fluorescence Unit |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SET | Sea Urchin Embryo Test |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| TGA-MS | Thermogravimetric Analysis coupled with Mass Spectrometry |

| TG-FTIR/DSC | Thermogravimetry coupled with Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| w/w | Weight-to-weight |

Appendix A

| Test Series | Germination Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| AVG | SD | |

| Control | 87.00 | 10.00 |

| Biopolymer | 84.00 | 11.78 |

| Biopolymer with BS1 | 78.00 | 5.20 |

| Biopolymer with BS2 | 85.00 | 11.50 |

| Biopolymer with BS3 | 85.00 | 10.00 |

| Test Series | Dry Weight Yield (g) | |

|---|---|---|

| AVG | SD | |

| Control | 4.01 | 0.12 |

| Biopolymer | 4.13 | 0.49 |

| Biopolymer with BS1 | 3.43 | 0.46 |

| Biopolymer with BS2 | 4.12 | 0.37 |

| Biopolymer with BS3 | 3.90 | 0.55 |

| Test Series | Germination Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| AVG | SD | |

| Control | 98.00 | 2.31 |

| Biopolymer | 96.00 | 4.62 |

| Biopolymer with BS1 | 96.00 | 5.70 |

| Biopolymer with BS2 | 94.00 | 9.50 |

| Biopolymer with BS3 | 98.00 | 2.30 |

| Test Series | Dry Weight Yield (g) | |

|---|---|---|

| AVG | SD | |

| Control | 1.93 | 0.15 |

| Biopolymer | 1.91 | 0.17 |

| Biopolymer with BS1 | 1.63 | 0.12 |

| Biopolymer with BS2 | 1.93 | 0.23 |

| Biopolymer with BS3 | 1.76 | 0.22 |

| Test Series | Survival (%) | Mortality (%) | Live Weight Yield | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g per Worm) | (% of Start) | ||||||

| AVG | SD | AVG | AVG | SD | AVG | SD | |

| Control | 100.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 126.92 | 0.59 |

| Biopolymer | 100.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.38 | 0.03 | 125.99 | 0.22 |

| Biopolymer with BS2 | 95.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 139.17 | 0.42 |

| Biopolymer with BS3 | 97.50 | 0.50 | 2.50 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 138.15 | 0.22 |

| Test Series | Microalgal Fluorescence (RFU) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| Control | 42.30 | 57.80 | 142.20 | 210.20 |

| Control (Filtered Seawater) | 42.30 | 56.20 | 139.00 | 226.20 |

| Biopolymer (High concentration) | 42.30 | 58.25 | 165.75 | 257.50 |

| Biopolymer (Environmental concentration) | 42.30 | 64.25 | 115.75 | 244.75 |

| Test Series | Relative Size (µm) | |

|---|---|---|

| AVG (T0) | SD | |

| Control | 301.60 | 7.34 |

| Biopolymer (High concentration) | 285.34 | 12.55 |

| Biopolymer (Environmental concentration) | 290.19 | 4.91 |

References

- Hann, S.; Fletcher, E.; Sherrington, C.; Molteno, S.; Elliott, L. Conventional and Biodegradable Plastics in Agriculture. Report for DG Environment of the European Commission; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Domínguez-Solera, E.; Gadaleta, G.; Ferrero-Aguar, P.; Navarro-Calderón, Á.; Escrig-Rondán, C. The Biodeg-radability of Plastic Products for Agricultural Application: European Regulations and Technical Criteria. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, D.D. Agricultural Plastics as Solid Waste: What Are the Options for Disposal? Horttechnology 1993, 3, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasirajan, S.; Ngouajio, M. Polyethylene and Biodegradable Mulches for Agricultural Applications: A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, K.A.; Adesina, F.A.; DeVetter, L.W.; Zhang, K.; DeWhitt, K.; Englund, K.R.; Miles, C. Recycling Agricultural Plastic Mulch: Limitations and Opportunities in the United States. Circ. Agric. Syst. 2024, 4, e005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Yang, X.; Pelaez, A.M.; Huerta Lwanga, E.; Beriot, N.; Gertsen, H.; Garbeva, P.; Geissen, V. Macro- and Micro- Plastics in Soil-Plant System: Effects of Plastic Mulch Film Residues on Wheat (Triticum aestivum) Growth. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, Z.; Wollmann, C.; Schaefer, M.; Buchmann, C.; David, J.; Tröger, J.; Muñoz, K.; Frör, O.; Schaumann, G.E. Plastic Mulching in Agriculture. Trading Short-Term Agronomic Benefits for Long-Term Soil Degradation? Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, N.; Shi, R.; Meng, J.; Guo, X.; Shi, M.; Zhang, X.; Yao, S.; Nkoh, J.N.; Wang, F.; Song, Y.; et al. Comparative Analysis of the Sorption Behaviors and Mechanisms of Amide Herbicides on Biodegradable and Nondegradable Microplastics Derived from Agricultural Plastic Products. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 318, 120865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Riksen, M.J.P.M.; Sirjani, E.; Sameni, A.; Geissen, V. Wind Erosion as a Driver for Transport of Light Density Microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 669, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, R.; Zeyer, T.; Schmidt, A.; Fiener, P. Soil Erosion as Transport Pathway of Microplastic from Agriculture Soils to Aquatic Ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberger, J.R.; Devetter, L.W.; Dentzman, K.E. Polyethylene and Biodegradable Plastic Mulches for Straw-berry Production in the United States: Experiences and Opinions of Growers in Three Regions. Horttechnology 2019, 29, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samphire, M.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L. Biodegradable Plastic Mulch Films Increase Yield and Promote Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Organic Horticulture. Front. Agron. 2023, 5, 1141608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVetter, L.W.; Zhang, H.; Ghimire, S.; Watkinson, S.; Miles, C.A. Plastic Biodegradable Mulches Reduce Weeds and Promote Crop Growth in Day-Neutral Strawberry in Western Washington. HortScience 2017, 52, 1700–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofanelli, M.B.D.; Wortman, S.E. Benchmarking the Agronomic Performance of Biodegradable Mulches against Polyethylene Mulch Film: A Meta-Analysis. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Galafassi, S.; Di Pippo, F.; Pojar, I.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F. A Critical Review of Biodegradable Plastic Mulch Films in Agriculture: Definitions, Scientific Background and Potential Impacts. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 170, 117391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Yang, L.; Wei, F.; Chen, Y.; Li, J. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Polyethylene Agricultural Mulching Film and Alternative Options Including Different End-of-Life Routes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 178, 113239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.; Wenzel, M.; Fischer, B.; Bertling, R.; Jelen, E.; Hennecke, D.; Weinfurtner, K.; Roß-Nickoll, M.; Hollert, H.; Weltmeyer, A.; et al. IMulch: An Investigation of the Influence of Polymers on a Terrestrial Ecosystem Using the Example of Mulch Films Used in Agriculture. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, B.; Wortman, S.; Hayes, D.G.; DeBruyn, J.M.; Miles, C.; Flury, M.; Marsh, T.L.; Galinato, S.P.; Englund, K.; Agehara, S.; et al. End-of-Life Management Options for Agricultural Mulch Films in the United States—A Review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 921496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Delegated Regulation (EU) 2024/2787 of the Commission of July 23, 2024, Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council with Respect to the Inclusion of Mulch Plastics in Category 9 of Component Materials; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2024/2787/oj/eng (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Ni, B.; Xiao, L.; Lin, D.; Zhang, T.L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, D.; Qian, H.; Rillig, M.C.; et al. Increasing Pesticide Diversity Impairs Soil Microbial Functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2419917122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, L.M.; Elle, E.; Morandin, L.A.; Cobb, N.S.; Chesshire, P.R.; McCabe, L.M.; Hughes, A.; Orr, M.; M’Gonigle, L.K. Impact of Pesticide Use on Wild Bee Distributions across the United States. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 1324–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ural-Janssen, A.; Kroeze, C.; Meers, E.; Strokal, M. Large Reductions in Nutrient Losses Needed to Avoid Future Coastal Eutrophication across Europe. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 197, 106446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizzetti, B.; Vigiak, O.; Udias, A.; Aloe, A.; Zanni, M.; Bouraoui, F.; Pistocchi, A.; Dorati, C.; Friedland, R.; De Roo, A.; et al. How EU Policies Could Reduce Nutrient Pollution in European Inland and Coastal Waters. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 69, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menegat, S.; Ledo, A.; Tirado, R. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Global Production and Use of Nitrogen Synthetic Fertilisers in Agriculture. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Sustainable Use of Nutrients. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/cap-my-country/sustainability/environmental-sustainability/low-input-farming/nutrients_en (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- European Commission. Pesticides and Plant Protection. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/cap-my-country/sustainability/environmental-sustainability/low-input-farming/pesticides_en (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- European Commission. Pesticide Reduction Targets—Progress. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/sustainable-use-pesticides/pesticide-reduction-targets-progress_en (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Ahmed, M.; Ullah, H.; Piromsri, K.; Tisarum, R.; Cha-Um, S.; Datta, A. Effects of an Ascophyllum Nodosum Seaweed Extract Application Dose and Method on Growth, Fruit Yield, Quality, and Water Productivity of Tomato under Water-Deficit Stress. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 151, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Cao, J.; Ji, H.; Hu, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, F.; Lu, Y.; Chen, N.; et al. Effects of Seaweed Fertilizer Application on Crops’ Yield and Quality in Field Conditions in China-A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Van Gerrewey, T.; Geelen, D. A Meta-Analysis of Biostimulant Yield Effectiveness in Field Trials. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 836702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, A.D.-X.; Wan Abdullah, W.M.A.N.; Tang, C.-N.; Low, L.-Y.; Yuswan, M.H.; Ong-Abdullah, J.; Tan, N.-P.; Lai, K.-S. Sodium Lignosulfonate Improves Shoot Growth of Oryza sativa via Enhancement of Photosynthetic Activity and Reduced Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Ortiz, R.; Naranjo, M.Á.; Atares, S.; Vicente, O.; Morillon, R. Micronutrient Fertiliser Reinforcement by Fulvate–Lignosulfonate Coating Improves Physiological Responses in Tomato. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Du, M.; Liu, G.; Ma, F.; Bao, Z. Lignin Sulfonate-Chelated Calcium Improves Tomato Plant Development and Fruit Quality by Promoting Ca2+ Uptake and Transport. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Kawai, T.; Inukai, Y.; Aoki, D.; Feng, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Fukushima, K.; Lin, X.; Shi, W.; Busch, W.; et al. A Lignin-Derived Material Improves Plant Nutrient Bioavailability and Growth through Its Metal Chelating Capacity. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.H.; Kuang, Y.; Wang, N. Amino Acids Biostimulants and Protein Hydrolysates in Agricultural Sciences. Plants 2024, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasković, I.; Popović, L.; Pongrac, P.; Polić Pasković, M.; Kos, T.; Jovanov, P.; Franić, M. Protein Hydroly-sates—Production, Effects on Plant Metabolism, and Use in Agriculture. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittarello, M.; Rodinò, M.T.; Sidari, R.; Panuccio, M.R.; Cozzi, F.; Branca, V.; Petrovičová, B.; Gelsomino, A. Employment of Biodegradable, Short-Life Mulching Film on High-Density Cropping Lettuce in a Mediterranean Environment: Potentials and Prospects. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.K.; Ching, Y.C.; Gan, S.N.; Rozali, S. Biodegradable Mulches Based on Poly(Vinyl Alcohol), Kenaf Fiber, and Urea. Bioresources 2015, 10, 5532–5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaramitaro, V.; Piacenza, E.; Paliaga, S.; Cavallaro, G.; Badalucco, L.; Laudicina, V.A.; Chillura Martino, D.F. Exploring the Feasibility of Polysaccharide-Based Mulch Films with Controlled Ammonium and Phosphate Ions Release for Sustainable Agriculture. Polymers 2024, 16, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Pan, H.; Barinelli, V.; Eriksen, B.; Ruiz, S.; Sobkowicz, M.J. Biodegradable Polyester Coated Mulch Paper for Controlled Release of Fertilizer. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 17033; Plastics—Biodegradable Mulch Films for Use in Agriculture and Horticulture—Requirements and Test Methods. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- ISO 19246:2016; Rubber Compounding Ingredients—Silica—Oil Absorption of Precipitated Silica. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Guillard, R.R.L.; Ryther, J.H. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (cleve) Gran. Can. J. Microbiol. 1962, 8, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10210:2018; Plastics—Methods for the Preparation of Samples for Biodegradation Testing of Plastic Materials. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO 20200:2024; Plastics—Determination of the Degree of Disintegration of Plastic Materials Under Composting Conditions in a Laboratory-Scale Test. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- OECD. Test No. 208: Terrestrial Plant Test: Seedling Emergence and Seedling Growth Test; OECD: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Test No. 207: Earthworm, Acute Toxicity Tests; OECD: Paris, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 11268-1:2012; Soil Quality—Effects of Pollutants on Earthworms. Part 1: Determination of Acute Toxicity to Eisenia Fetida/Eisenia Andrei. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Beiras, R.; Schönemann, A.M. Currently Monitored Microplastics Pose Negligible Ecological Risk to the Global Ocean. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.; Herat, S. Ecotoxicity of Microplastic Pollutants to Marine Organisms: A Systematic Review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertucci, J.I.; Juez, A.; Bellas, J. Impact of Microplastics and Ocean Acidification on Critical Stages of Sea Urchin (Paracentrotus lividus) Early Development. Chemosphere 2022, 301, 134783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saco-Álvarez, L.; Durán, I.; Ignacio Lorenzo, J.; Beiras, R. Methodological Basis for the Optimization of a Marine Sea-Urchin Embryo Test (SET) for the Ecological Assessment of Coastal Water Quality. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2010, 73, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, D.I.; Lazzara, G.; Milioto, S. Thermogravimetric Analysis: A Tool to Evaluate the Ability of Mixtures in Consolidating Waterlogged Archaeological Woods. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2010, 101, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Dinesha, P. Thermal Dissociation Kinetics of Solid Ammonium Carbonate for Use in NH3-SCR Systems. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 6551–6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, I.M.; Muth, C.; Drumm, R.; Kirchner, H.O.K. Thermal Decomposition of the Amino Acids Glycine, Cysteine, Aspartic Acid, Asparagine, Glutamic Acid, Glutamine, Arginine and Histidine. BMC Biophys. 2018, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, H.S.S.; Selby, C.; Carmichael, E.; McRoberts, C.; Rao, J.R.; Ambrosino, P.; Chiurazzi, M.; Pucci, M.; Martin, T. Physicochemical Analyses of Plant Biostimulant Formulations and Characterisation of Commercial Products by Instrumental Techniques. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2016, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni Júnior, L.; Rodrigues, P.R.; da Silva, R.G.; Vieira, R.P.; Alves, R.M.V. Sustainable Packaging Films Composed of Sodium Alginate and Hydrolyzed Collagen: Preparation and Characterization. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2021, 14, 2336–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, S.A.; Wagner, S.; Nagl, R.; Pellis, A.; Gigli, M.; Crestini, C.; Horvat, M.; Zeiner, T.; Guebitz, G.M.; Weiss, R.; et al. Physicochemical Insights into Enzymatic Polymerization of Lignosulfonates. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 17739–17751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yin, H.; Zhang, H.; Mei, N.; Mu, L. Pyrolysis Characteristics, Gas Products, Volatiles, and Thermo–Kinetics of Industrial Lignin via TG/DTG–FTIR/MS and in–Situ Py–PI–TOF/MS. Energy 2022, 259, 125062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosin, K.G.; Finimundi, N.; Poletto, M. A Systematic Study of the Structural Properties of Technical Lignins. Polymers 2025, 17, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudicianni, P.; Gargiulo, V.; Grottola, C.M.; Alfè, M.; Ferreiro, A.I.; Mendes, M.A.A.; Fagnano, M.; Ragucci, R. Inherent Metal Elements in Biomass Pyrolysis: A Review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 5407–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presbítero-Espinosa, G.; Peña-Parás, L.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.A.; Pizaña, E.I.R.; Galván, K.P.V.; Vopálenský, M.; Kumpová, I.; Elizalde-Herrera, L.E. Characterization of Sodium Alginate Hydrogels Reinforced with Nano-particles of Hydroxyapatite for Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, F.; Adigüzel, D.; Atmaca, U.; Çelik, M.; Naktiyok, J. Characterization and Kinetics Analysis of the Thermal Decomposition of the Humic Substance from Hazelnut Husk. Turk. J. Chem. 2020, 44, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, Y.; Li, H.; Dong, H.; Li, B.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Yin, T.; Liu, X.; et al. Responses of Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) Growth and Soil Properties to Conventional Non-Biodegradable and New Biodegradable Microplastics. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 341, 122897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Xiu, X.; Hao, W. Microplastics in Soils: Production, Behavior Process, Impact on Soil Organisms, and Related Toxicity Mechanisms. Chemosphere 2024, 350, 141060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderiardakani, F.; Collas, E.; Damiano, D.K.; Tagg, K.; Graham, N.S.; Coates, J.C. Effects of Green Seaweed Extract on Arabidopsis Early Development Suggest Roles for Hormone Signalling in Plant Responses to Algal Fertilisers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Herrera, R.M.; González-González, M.F.; Velasco-Ramírez, A.P.; Velasco-Ramírez, S.F.; San-tacruz-Ruvalcaba, F.; Zamora-Natera, J.F. Seaweed Extract Components Are Correlated with the Seeds Germination and Growth of Tomato Seedlings. Seeds 2023, 2, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liwarska-Bizukojc, E.; Bernat, P.; Jasińska, A. Effect of Bio-Based Microplastics on Earthworms Eisenia Andrei. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 898, 165423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaldoon, S.; Lalung, J.; Kamaruddin, M.A.; Yhaya, M.F.; Alam, M.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Rafatullah, M. Short-Term Effect of Poly Lactic Acid Microplastics Uptake by Eudrilus Eugenia. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 102111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Seijo, A.; Lourenço, J.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P.; da Costa, J.; Duarte, A.C.; Vala, H.; Pereira, R. Histopathological and Molecular Effects of Microplastics in Eisenia Andrei Bouché. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Geng, B.; Zhu, C.; Li, L.; Francis, F. An Improved Vermicomposting System Provides More Efficient Wastewater Use of Dairy Farms Using Eisenia fetida. Agronomy 2021, 11, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, S.; Peng, B.Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Distinct Exposure Impact of Non-Degradable and Biodegradable Microplastics on Freshwater Microalgae (Chlorella pyrenoidosa): Implications for Polylactic Acid as a Sustainable Plastic Alternative. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Hou, Y.; Lin, S.; Gao, L.; Wang, Z.; Bao, R.; Peng, L. Biodegradable and conventional microplastics posed similar toxicity to marine algae Chlorella Vulgaris. Aquat. Toxicol. 2022, 244, 106097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viel, T.; Cocca, M.; Manfra, L.; Caramiello, D.; Libralato, G.; Zupo, V.; Costantini, M. Effects of biodegradable-based microplastics in Paracentrotus lividus Lmk embryos: Morphological and gene expression analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 334, 122129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viel, T.; Cocca, M.; Esposito, R.; Amato, A.; Russo, T.; Di Cosmo, A.; Polese, G.; Manfra, L.; Libralato, G.; Zupo, V.; et al. Effect of Biodegradable Polymers upon Grazing Activity of the Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lmk) Revealed by Morphological, Histological and Molecular Analyses. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Falco, F.; Nacci, T.; Durndell, L.; Thompson, R.C.; Degano, I.; Modugno, F. A Thermoanalytical Insight into the Composition of Biodegradable Polymers and Commercial Products by EGA-MS and Py-GC-MS. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 171, 105937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biostimulant | Major Component | Minor Component |

|---|---|---|

| BS1 | Seaweed extract | Plant amino acids Complexed iron |

| BS2 | Plant amino acids | Organic acids of plant origin |

| BS3 | Lignosulfonates | Micronutrients Organic nitrogen |

| In Porous Substrate (% w/w) * | In Masterbatch (% w/w) | In Final Film (% w/w) |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 5 | 0.5 |

| Experiment Time (Day) | Biopolymer Concentration ± s (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.004 ± 0.002 |

| 60 | <LOD |

| 120 | <LOD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Escrig Rondán, C.; Sevilla Gil, C.; Sanz Fernández, P.; Ferrer Crespo, J.F.; Furió Sanz, C. Incorporation of Natural Biostimulants in Biodegradable Mulch Films for Agricultural Applications: Ecotoxicological Evaluation. Polymers 2025, 17, 3027. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223027

Escrig Rondán C, Sevilla Gil C, Sanz Fernández P, Ferrer Crespo JF, Furió Sanz C. Incorporation of Natural Biostimulants in Biodegradable Mulch Films for Agricultural Applications: Ecotoxicological Evaluation. Polymers. 2025; 17(22):3027. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223027

Chicago/Turabian StyleEscrig Rondán, Chelo, Celia Sevilla Gil, Pablo Sanz Fernández, Juan Francisco Ferrer Crespo, and Cristina Furió Sanz. 2025. "Incorporation of Natural Biostimulants in Biodegradable Mulch Films for Agricultural Applications: Ecotoxicological Evaluation" Polymers 17, no. 22: 3027. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223027

APA StyleEscrig Rondán, C., Sevilla Gil, C., Sanz Fernández, P., Ferrer Crespo, J. F., & Furió Sanz, C. (2025). Incorporation of Natural Biostimulants in Biodegradable Mulch Films for Agricultural Applications: Ecotoxicological Evaluation. Polymers, 17(22), 3027. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223027