A Guide for Industrial Needleless Electrospinning of Synthetic and Hybrid Nanofibers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Solution Preparation

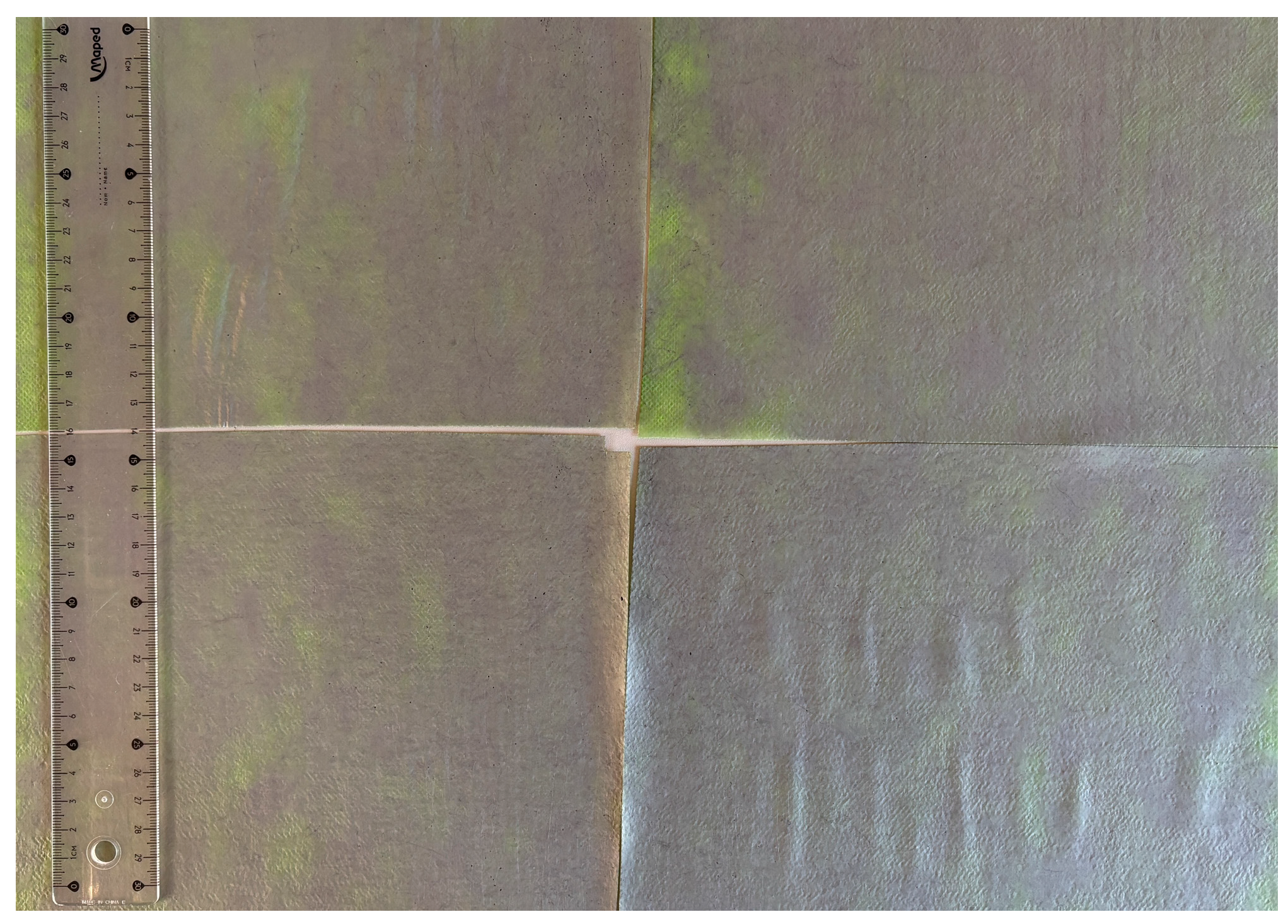

2.3. Electrospinning of Synthetic and Hybrid Nanofibers

2.4. Characterization of Nanofibers

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Electrospinning of CA Nanofibers

3.2. Electrospinning of PCL Nanofibers

3.3. Electrospinning of PA6 Nanofibers

3.4. Electrospinning of PA11 and PA12 Nanofibers

3.5. Electrospinning of PAN Nanofibers

3.6. Electrospinning of PVDF Nanofibers

3.7. Electrospinning of PU Nanofibers

3.8. Electrospinning of PVB Nanofibers

3.9. Electrospinning of PVA Nanofibers

3.10. Electrospinning of PA6 Nanofibers Containing Nanoparticles

3.11. Electrospinning of PAN Nanofibers Containing Nanoparticles

3.12. Electrospinning of PU Nanofibers Containing Nanoparticles

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Persano, L.; Camposeo, A.; Tekmen, C.; Pisignano, D. Industrial Upscaling of Electrospinning and Applications of Polymer Nanofibers: A Review. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2013, 298, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Lin, Y.; Guo, X.; Ramasubramanian, B.; Wang, R.; Radacsi, N.; Jose, R.; Qin, X.; Ramakrishna, S. Electrospinning of Nanofibres. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2024, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz-Çallıoǧlu, F.; Jirsak, O.; Dayik, M. Investigation into the Relationships between Independent and Dependent Parameters in Roller Electrospinning of Polyurethane. Text. Res. J. 2013, 83, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcinkaya, F. Preparation of Various Nanofiber Layers Using Wire Electrospinning System. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 5162–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirsak, O.; Petrik, S. Needleless Electrospinning-History, Present and Future. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference-TEXSCI 2010, Liberec, Czech Republic, 6–8 September 2010; pp. 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Formhals, A. Process and Apparatus for Preparing Artificial Threads. US Patent Specification 1975504, 2 October 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Druzhinin, E. Production and Properties of Petryanov Filtering Materials Made of Ultrathin Polymeric Fibers; IzdAT: Moscow, Russia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Oldřich, J.; Sanetrník, F.; Lukáš, D.; Kotek, V.; Martinová, L.; Chaloupek, J. Způsob Výroby Nanovláken z Polymerního Roztoku Elektrostatickým Zvlákňováním a Zařízení k Provádění Způsobu. Patentový spis č 294274, 11 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yalcinkaya, F.; Yalcinkaya, B.; Jirsak, O. Dependent and Independent Parameters of Needleless Electrospinning. In Electrospinning–Material, Techniques and Biomedical Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016; pp. 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Green, T.B.; King, S.L.; Li, L. Apparatus and Method for Reducing Solvent Loss for Electrospinning of Fine Fibers. US Patent 7815427B2, 21 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Petras, D.; Mares, L.; Stranska, D. Method and Device for Production of Nanofibres From the Polymeric Solution Through Electrostatic Spinning. US Patent 20080307766A1, 18 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Petras, D.; Mares, L.; Cmelik, J.; Fiala, K. Device for Production of Nanofibres through Electrostatic Spinning of Polymer Solutions. US Patent 20090148547A1, 11 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schneiders, T. Electrospinning of Micro-/Nanofibers. In Particle Technology and Textiles: Review of Applications; De Gruyter Brill: Berlin, Germany, 2023; p. 305. [Google Scholar]

- Kallina, V.; Oezaslan, M.; Hasché, F. Electrospun Fuel Cell Cathode Catalyst Layers Under Low Humidity Conditions; The Electrochemical Society, Inc.: Pennington, NJ, USA, 2024; p. 3023. [Google Scholar]

- Grothe, T.; Großerhode, C.; Hauser, T.; Kern, P.; Stute, K.; Ehrmann, A. Needleless Electrospinning of PEO Nanofiber Mats; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kozior, T.; Mamun, A.; Trabelsi, M.; Wortmann, M.; Lilia, S.; Ehrmann, A. Electrospinning on 3D Printed Polymers for Mechanically Stabilized Filter Composites. Polymers 2019, 11, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avossa, J.; Batt, T.; Pelet, T.; Sidjanski, S.P.; Schönenberger, K.; Rossi, R.M. Polyamide Nanofiber-Based Air Filters for Transparent Face Masks. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 12401–12406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares, L.; Petras, D.; Kuzel, P. Filter for Removing of Physical and/or Biological Impurities. US Patent 20080264258A1, 30 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, F.; Castro-Muñoz, R.; Santoro, S.; Galiano, F.; Figoli, A. A Review on Electrospun Membranes for Potential Air Filtration Application. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. High-performance PM0.3 Air Filters Using Self-polarized Electret Nanofiber/Nets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1909554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Dang, B.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, Q. Dual-Network Structured Nanofibrous Membranes with Superelevated Interception Probability for Extrafine Particles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 15036–15046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorji, M.; Jeddi, A.A.; Gharehaghaji, A. Fabrication and Characterization of Polyurethane Electrospun Nanofiber Membranes for Protective Clothing Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 125, 4135–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, G.; Samiee, S.; Gharehaghaji, A.A.; Hajiani, F. Fabrication of Polyurethane and Nylon 66 Hybrid Electrospun Nanofiber Layer for Waterproof Clothing Applications. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2016, 35, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitu, N.A.; Ma, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, S.; Hasan, M.M.; Hu, Y. Wearable Colorful Nanofiber of Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) Mechanical and Colorfastness Properties by Dope Dyeing. Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 2485–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, X.; Sun, G.; Wang, G.; Han, Q.; Meng, C.; Wei, Z.; Li, Y. Natural Human Skin-Inspired Wearable and Breathable Nanofiber-Based Sensors with Excellent Thermal Management Functionality. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2024, 6, 1955–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krifa, M.; Prichard, C. Nanotechnology in Textile and Apparel Research–an Overview of Technologies and Processes. J. Text. Inst. 2020, 111, 1778–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Bonakdar, M.; Rodrigue, D. Electrospinning: Processes, Structures, and Materials. Macromol 2024, 4, 58–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Qian, Y.; Haghayegh, M.; Xia, Y.; Yang, S.; Cao, R.; Zhu, M. Electrospun Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Nanofibers for Accelerating Wound Healing: A Review. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 3171–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavari, A.; Ito, T.; Hara, K.; Tahara, K. Comparative Analysis of Needleless and Needle-Based Electrospinning Methods for Polyamide 6: A Technical Note. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2025, 73, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danagody, B.; Bose, N.; Rajappan, K. Electrospun Polyacrylonitrile-Based Nanofibrous Membrane for Various Biomedical Applications. J. Polym. Res. 2024, 31, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaarour, B.; Liu, W. Enhanced Piezoelectric Performance of Electrospun PVDF Nanofibers by Regulating the Solvent Systems. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2022, 17, 15589250221125437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaarour, B.; Liu, W.; Omran, W.; Alhinnawi, M.F.; Dib, F.; Shikh Alshabab, M.; Ghannoum, S.; Kayed, K.; Mansour, G.; Balidi, G. A Mini-Review on Wrinkled Nanofibers: Preparation Principles via Electrospinning and Potential Applications. J. Ind. Text. 2024, 54, 15280837241255396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabur, A.R.; Abbas, L.K.; Muhi Aldain, S.M. The Effects of Operating Parameters on the Morphology of Electrospun Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanofibres. J. Kerbala Univ. 2012, 8, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, U.M.; Kumar, S.V.; Nagiah, N.; Sivagnanam, U.T. Fabrication of Polyvinyl Alcohol-Polyvinylpyrrolidone Blend Scaffolds via Electrospinning for Tissue Engineering Applications. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2014, 63, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Schueren, L.; De Schoenmaker, B.; Kalaoglu, Ö.I.; De Clerck, K. An Alternative Solvent System for the Steady State Electrospinning of Polycaprolactone. Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 1256–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casasola, R.; Thomas, N.L.; Trybala, A.; Georgiadou, S. Electrospun Poly Lactic Acid (PLA) Fibres: Effect of Different Solvent Systems on Fibre Morphology and Diameter. Polymer 2014, 55, 4728–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulkersdorfer, B.; Kao, K.; Agopian, V.; Ahn, A.; Dunn, J.; Wu, B.; Stelzner, M. Bimodal Porous Scaffolds by Sequential Electrospinning of Poly (Glycolic Acid) with Sucrose Particles. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2010, 2010, 436178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin-Orozco, J.; Zapata-Torres, M.; Rodriguez-Gattorno, G.; Pedroza-Islas, R. Properties of Poly (Ethylene Oxide)/Whey Protein Isolate Nanofibers Prepared by Electrospinning. Food Biophys. 2015, 10, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Lei, G.; Li, Z.; Wu, L.; Xiao, Q.; Wang, L. A Novel Polyethylene Terephthalate Nonwoven Separator Based on Electrospinning Technique for Lithium Ion Battery. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 428, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandhan, S.; Ponprapakaran, K.; Senthil, T.; George, G. Parametric Study of Manufacturing Ultrafine Polybenzimidazole Fibers by Electrospinning. Int. J. Plast. Technol. 2012, 16, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcinkaya, B.; Buzgo, M. Optimization of Electrospun TORLON® 4000 Polyamide-Imide (PAI) Nanofibers: Bridging the Gap to Industrial-Scale Production. Polymers 2024, 16, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, M.; Monteserín, C.; Gómez, E.; Aranzabe, E.; Vilas Vilela, J.L.; Pérez-Márquez, A.; Maudes, J.; Vaquero, C.; Murillo, N.; Zalakain, I. Polycarbonate Nanofiber Filters with Enhanced Efficiency and Antibacterial Performance. Polymers 2025, 17, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lv, H.; Shi, H.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Y.; Yu, D.-G. Processes of Electrospun Polyvinylidene Fluoride-Based Nanofibers, Their Piezoelectric Properties, and Several Fantastic Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotia, A.; Malara, A.; Paone, E.; Bonaccorsi, L.; Frontera, P.; Serrano, G.; Caneschi, A. Self Standing Mats of Blended Polyaniline Produced by Electrospinning. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, F. Synthesis and Application of Polypyrrole Nanofibers: A Review. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 3606–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstone, B.N.; Gallentine, S.C.; Powell, H.M. Collagen-Based Electrospun Materials for Tissue Engineering: A Systematic Review. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Ramakrishna, S.; Lim, C. Electrospinning and Mechanical Characterization of Gelatin Nanofibers. Polymer 2004, 45, 5361–5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, K.; Cha, D.; Kim, H.; Nishida, A.; Yamamoto, H. Electrospinning of Chitosan. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2004, 25, 1600–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, M.W. Electrospinning Cellulose and Cellulose Derivatives. Polym. Rev. 2008, 48, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska-Krepsztul, J.; Rydzkowski, T.; Michalska-Pożoga, I.; Thakur, V.K. Biopolymers for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications: Recent Advances and Overview of Alginate Electrospinning. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Nam, Y.S.; Lee, T.S.; Park, W.H. Silk Fibroin Nanofiber. Electrospinning, Properties, and Structure. Polym. J. 2003, 35, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, K.C.; Campos, M.G.N.; Mei, L.H.I. Hyaluronic Acid Electrospinning: Challenges, Applications in Wound Dressings and New Perspectives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 173, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Fang, D.; Hsiao, B.S.; Chu, B.; Chen, W. Optimization and Characterization of Dextran Membranes Prepared by Electrospinning. Biomacromolecules 2004, 5, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, K.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Huang, J.-Y.; Kuo, W.-T.; Lin, F.-H. Fabrication of Keratin/Fibroin Membranes by Electrospinning for Vascular Tissue Engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hifyber Is Designed for High Efficiency Nanofiber Filtration. Gas Turbine Air Intake Filter Media. Available online: https://www.hifyber.com/en/products/gas-turbine-air-intake-filter-media (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Hifyber Is Designed for High Efficiency Nanofiber Filtration. Textile Membrane. Available online: https://www.hifyber.com/en/products/textile-membrane (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Nanofiber Membranes|Respilon—Life’s Worth It. Available online: https://www.respilon.com/products/nanofiber-membranes/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Respilon VK|Respilon—Life’s Worth It. Available online: https://www.respilon.com/products/products/respilon-vk/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Nanofiber DrySerum in Face Mask Form|Respibeauty—Dryserum. Eu. Available online: https://dryserum.eu/en/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Pisani, S.; Dorati, R.; Conti, B.; Modena, T.; Bruni, G.; Genta, I. Design of Copolymer PLA-PCL Electrospun Matrix for Biomedical Applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2018, 124, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Herrero, M.; Gómez-Tejedor, J.-A.; Vallés-Lluch, A. PLA/PCL Electrospun Membranes of Tailored Fibres Diameter as Drug Delivery Systems. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 99, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Satapathy, B.K. Optimization and Physical Performance Evaluation of Electrospun Nanofibrous Mats of PLA, PCL and Their Blends. J. Ind. Text. 2022, 51, 6640S–6665S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semnani, D.; Naghashzargar, E.; Hadjianfar, M.; Dehghan Manshadi, F.; Mohammadi, S.; Karbasi, S.; Effaty, F. Evaluation of PCL/Chitosan Electrospun Nanofibers for Liver Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2017, 66, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimirad, S.; Abtahi, H.; Satei, P.; Ghaznavi-Rad, E.; Moslehi, M.; Ganji, A. Wound Healing Performance of PCL/Chitosan Based Electrospun Nanofiber Electrosprayed with Curcumin Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 259, 117640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.R.; Rodrigues, G.; Martins, G.G.; Roberto, M.A.; Mafra, M.; Henriques, C.; Silva, J.C. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of Electrospun Nanofibers of PCL, Chitosan and Gelatin: A Comparative Study. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 46, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Jiang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Shao, W. Electrospun PVA/Gelatin Based Nanofiber Membranes with Synergistic Antibacterial Performance. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 637, 128196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Puyana, V.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Romero, A.; Guerrero, A. Development of PVA/Gelatin Nanofibrous Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering via Electrospinning. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 035401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Zhao, P.; Wu, C.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J. Electrospun PAN/PANI Fiber Film with Abundant Active Sites for Ultrasensitive Trimethylamine Detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 338, 129822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, H.; Miao, Y.; Tian, C.; Li, W.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y. Influence of the Conductivity of Polymer Matrix on the Photocatalytic Activity of PAN–PANI–ZIF8 Electrospun Fiber Membranes. Fibers Polym. 2023, 24, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, W.; Yu, D. One-Step Electrospinning PVDF/PVP-TiO2 Hydrophilic Nanofiber Membrane with Strong Oil-Water Separation and Anti-Fouling Property. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 624, 126790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Pathak, D.; Patil, D.S.; Dhiman, N.; Bhullar, V.; Mahajan, A. Electrospun PVP/TiO2 Nanofibers for Filtration and Possible Protection from Various Viruses like COVID-19. Technologies 2021, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, N.A.; Rahman, N.A.; Lim, H.N.; Zawawi, R.M.; Sulaiman, Y. Electrochemical Properties of PVA–GO/PEDOT Nanofibers Prepared Using Electrospinning and Electropolymerization Techniques. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 17720–17727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Song, W.; Song, J.; Torrejon, V.M.; Xia, Q. Electrospun 1D and 2D Carbon and Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) Piezoelectric Nanocomposites. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 9452318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi, M.; Riva, L.; Caruso, M.; Punta, C. Cellulose for the Production of Air-Filtering Systems: A Critical Review. Materials 2022, 15, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastman Cellulose Acetate (CA-320S). Available online: https://www.eastman.com/en/products/product-detail/71001232/eastman-cellulose-acetate-ca-320s (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Eastman Cellulose Acetate Butyrate (CAB-321-0.1)|Eastman. Available online: https://www.eastman.com/en/products/product-detail/71001252/eastman-cellulose-acetate-butyrate-cab-321-01?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Eastman Cellulose Acetate Propionate (CAP-482-20)|Eastman. Available online: https://www.eastman.com/en/products/product-detail/71001224/eastman-cellulose-acetate-propionate-cap-482-20?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Eastman Cellulose Esters, Eastman—ChemPoint. Available online: https://www.chempoint.com/products/eastman/eastman-cellulose-esters (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Norris, Q. Characterization of Norbornene-Modified Cellulose Electrospun Fibers in Different Solvent Systems for Biomedical Applications. 2022. Available online: https://abstracts.biomaterials.org/data/papers/2022/abstracts/620.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Liu, H.; Tang, C. Electrospinning of Cellulose Acetate in Solvent Mixture N, N-Dimethylacetamide (DMAc)/Acetone. Polym. J. 2007, 39, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.; Torretti, M.; Madbouly, S. Biodegradable Polycaprolactone (PCL) Based Polymer and Composites. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2023, 8, 4391–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, N.; Pahwa, R.; Khosla, J.K.; Gupta, P.N.; Gupta, M. Polycaprolactone-Based Materials in Wound Healing Applications. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 7041–7063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogorielov, M.; Hapchenko, A.; Deineka, V.; Rogulska, L.; Oleshko, O.; Vodseďálková, K.; Berezkinová, L.; Vysloužilová, L.; Klápšťová, A.; Erben, J. In Vitro Degradation and in Vivo Toxicity of NanoMatrix3D® Polycaprolactone and Poly (Lactic Acid) Nanofibrous Scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2018, 106, 2200–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Campagne, C.; Salaün, F. Influence of Solvent Selection in the Electrospraying Process of Polycaprolactone. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, T.; Bhat, G.S.; Tock, R.W.; Parameswaran, S.; Ramkumar, S.S. Electrospinning of Nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 96, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enis, I.Y.; Vojtech, J.; Sadikoglu, T.G. Alternative Solvent Systems for Polycaprolactone Nanowebs via Electrospinning. J. Ind. Text. 2017, 47, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-P.; Chen, S.-C.; Wu, X.-Q.; Ke, X.-X.; Wu, R.-X.; Zheng, Y.-M. Multilevel Structured TPU/PS/PA-6 Composite Membrane for High-Efficiency Airborne Particles Capture: Preparation, Performance Evaluation and Mechanism Insights. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 633, 119392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, I.P.; Berry, G.; Cho, H.; Riveros, G. Alternative High-Performance Fibers for Nonwoven HEPA Filter Media. Aerosol Sci. Eng. 2023, 7, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulgar, S.p.A. NANOFIBRA BY FULGAR®|Ultralight Microfiber Yarn. Available online: https://www.fulgar.com/en/products/62/nanofibra-by-fulgar (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Akshat, T.; Misra, S.; Gudiyawar, M.; Salacova, J.; Petru, M. Effect of Electrospun Nanofiber Deposition on Thermo-Physiology of Functional Clothing. Fibers Polym. 2019, 20, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supaphol, P.; Mit-uppatham, C.; Nithitanakul, M. Ultrafine Electrospun Polyamide-6 Fibers: Effects of Solvent System and Emitting Electrode Polarity on Morphology and Average Fiber Diameter. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2005, 290, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmala, R.; Panth, H.R.; Yi, C.; Nam, K.T.; Park, S.-J.; Kim, H.Y.; Navamathavan, R. Effect of Solvents on High Aspect Ratio Polyamide-6 Nanofibers via Electrospinning. Macromol. Res. 2010, 18, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M.; Abenojar, J.; Martínez, M.A. Comparative Characterization of Hot-Pressed Polyamide 11 and 12: Mechanical, Thermal and Durability Properties. Polymers 2021, 13, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behler, K.; Havel, M.; Gogotsi, Y. New Solvent for Polyamides and Its Application to the Electrospinning of Polyamides 11 and 12. Polymer 2007, 48, 6617–6621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.; Khan, T.; Basit, M.; Masood, R.; Raza, Z. Polyacrylonitrile-based Electrospun Nanofibers–A Critical Review. Mater. Werkst. 2022, 53, 1575–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenistaya, T. Polyacrylonitrile-Based Materials: Properties, Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Rocha, J.E.; Moreno Tovar, K.R.; Navarro Mendoza, R.; Gutiérrez Granados, S.; Cavaliere, S.; Giaume, D.; Barboux, P.; Jaime Ferrer, J.S. Critical Electrospinning Parameters for Synthesis Control of Stabilized Polyacrylonitrile Nanofibers. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, L.; Han, R.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Y. Solvent Selection for Polyacrylonitrile Using Molecular Dynamic Simulation and the Effect of Process Parameters of Magnetic-Field-Assisted Electrospinning on Fiber Alignment. High Perform. Polym. 2015, 27, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhari, J.; Aj, S.; Nawawi, Z.; Sriyanti, I. Synthesis and Characteristics of Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) Nanofiber Membrane Using Electrospinning Method. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2021, 56, 698–703. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z.; Cheng, J.; Huang, Q.; Chen, M.; Xiao, C. Electrospinning Organic Solvent Resistant Preoxidized Poly (Acrylonitrile) Nanofiber Membrane and Its Properties. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 53, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Xu, X.; Fu, J.; Yu, D.-G.; Liu, Y. Recent Progress in Electrospun Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber-Based Wound Dressing. Polymers 2022, 14, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpourfazeli, S.; Arash, S.; Ansari, A.; Yang, S.; Mallick, K.; Bagherzadeh, R. Future Prospects and Recent Developments of Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) Piezoelectric Polymer; Fabrication Methods, Structure, and Electro-Mechanical Properties. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, L.; He, H.; Wang, Z.L.; Qu, J.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z. Giant Piezoelectric Coefficient of Polyvinylidene Fluoride with Rationally Engineered Ultrafine Domains Achieved by Rapid Freezing Processing. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2412344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szewczyk, P.K.; Ura, D.P.; Stachewicz, U. Humidity Controlled Mechanical Properties of Electrospun Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) Fibers. Fibers 2020, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaarour, B.; Zhu, L.; Huang, C.; Jin, X. Controlling the Secondary Surface Morphology of Electrospun PVDF Nanofibers by Regulating the Solvent and Relative Humidity. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadil, F.; Affandi, N.D.N.; Misnon, M.I.; Bonnia, N.N.; Harun, A.M.; Alam, M.K. Review on Electrospun Nanofiber-Applied Products. Polymers 2021, 13, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.K.S.; Prakash, C. Characterization of Electrospun Polyurethane/Polyacrylonitrile Nanofiber for Protective Textiles. Iran. Polym. J. 2021, 30, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Yi, Y.; Fu, Y.; Xiong, J.; Li, N. Durable Polyurethane/SiO2 Nanofibrous Membranes by Electrospinning for Waterproof and Breathable Textiles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 10686–10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhao, K.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z. Synthesis and Application of Polyvinyl Butyral Resins: A Review. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2025, 226, 2400478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, F.; Jirsak, O.; Gemci, R. Using a Range of PVB Spinning Solution to Acquire Diverse Morphology for Electrospun Nanofibres. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2012, 31, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, G.; Li, Z.; Tian, L.; Lu, D.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Yu, H.; He, J.; Sun, D. Environmentally Friendly Waterproof and Breathable Electrospun Nanofiber Membranes via Post-Heat Treatment. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 658, 130643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Muzwar, M.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Chetty, R.; Karaiyan, A.P. Electrospun Nylon-66 Nanofiber Coated Filter Media for Engine Air Filtration Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e54618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Qin, M.; Xu, M.; Zhao, L.; Wei, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lian, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, W.; Huang, D. Coated Electrospun Polyamide-6/Chitosan Scaffold with Hydroxyapatite for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 16, 025014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurave, P.M.; Rastgar, M.; Mizan, M.M.H.; Srivastava, R.K.; Sadrzadeh, M. Superhydrophilic Electrospun Polyamide-Imide Membranes for Efficient Oil/Water Separation under Gravity. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2023, 1, 3134–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Hassanpour Amiri, M.; Jiang, S.; Abolhasani, M.M.; Rocha, P.R.; Asadi, K. Piezoelectric Nylon-11 Fibers for Electronic Textiles, Energy Harvesting and Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2004326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, C.; Shi, S.; Si, Y.; Fei, B.; Huang, H.; Hu, J. Recent Progress of Wearable Piezoelectric Pressure Sensors Based on Nanofibers, Yarns, and Their Fabrics via Electrospinning. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2201161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; Wang, L.; Yu, K.; Wei, Q.; Hussain, T.; Xia, X.; Zhou, H. Electrospun PVB/AVE NMs as Mask Filter Layer for Win-Win Effects of Filtration and Antibacterial Activity. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 672, 121473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porporato, S.; Darjazi, H.; Gastaldi, M.; Piovano, A.; Perez, A.; Yécora, B.; Fina, A.; Meligrana, G.; Elia, G.A.; Gerbaldi, C. On the Use of Recycled PVB to Develop Sustainable Separators for Greener Li-Ion Batteries. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, 2400569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zheng, S.; Jing, M.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yu, L.; Sun, S.; Wang, S. Enhancing Sound Insulation of Glass Interlayer Films by Introducing Piezoelectric Fibers. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 2466–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hsia, T.; Merenda, A.; Al-Attabi, R.; Dumee, L.F.; Thang, S.H.; Kong, L. Constructing Novel Nanofibrous Polyacrylonitrile (PAN)-Based Anion Exchange Membrane Adsorber for Protein Separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 285, 120364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, X.; Yan, J.; Guan, C.; Wang, J. Electrospun Nanofibers for New Generation Flexible Energy Storage. Energy Environ. Mater. 2021, 4, 502–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Khanian, N.; Shojaei, T.R.; Choong, T.S.Y.; Asim, N. Fundamental and Recent Progress on the Strengthening Strategies for Fabrication of Polyacrylonitrile (PAN)-Derived Electrospun CNFs: Precursors, Spinning and Collection, and Post-Treatments. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 110, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicy, K.; Gueye, A.B.; Rouxel, D.; Kalarikkal, N.; Thomas, S. Lithium-Ion Battery Separators Based on Electrospun PVDF: A Review. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 31, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Cong, H.; Jiang, G.; Liang, X.; Liu, L.; He, H. A Review on PVDF Nanofibers in Textiles for Flexible Piezoelectric Sensors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 1522–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaarour, B. Enhanced Piezoelectricity of PVDF Nanofibers via a Plasticizer Treatment for Energy Harvesting. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8, 125001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, F.; Samadi, A.; Rashed, A.O.; Li, X.; Razal, J.M.; Kong, L.; Varley, R.J.; Zhao, S. Recent Progress in Electrospun Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF)-Based Nanofibers for Sustainable Energy and Environmental Applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 148, 101376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Das, S.; Dasgupta, S.; Sengupta, P.; Datta, P. Flexible Nanogenerator from Electrospun PVDF–Polycarbazole Nanofiber Membranes for Human Motion Energy-Harvesting Device Applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaarour, B.; Mansour, G. Fabrication of Perfect Branched PVDF/TiO2 Nanofibers for Keeping Food Fresh via One-Step Electrospinning. Nano 2025, 2550018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudabadi, M.; Fahimirad, S.; Ganji, A.; Abtahi, H. Wound Healing and Antibacterial Capability of Electrospun Polyurethane Nanofibers Incorporating Calendula Officinalis and Propolis Extracts. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2023, 34, 1491–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, N.; Del Bakhshayesh, A.R.; Sadeghzadeh, H.; Asl, A.N.; Kaamyabi, S.; Akbarzadeh, A. Nanocomposite Electrospun Scaffold Based on Polyurethane/Polycaprolactone Incorporating Gold Nanoparticles and Soybean Oil for Tissue Engineering Applications. J. Bionic Eng. 2023, 20, 1712–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fu, Y.; Liu, R.; Xiong, J.; Li, N. Waterproof, Breathable and Infrared-Invisible Polyurethane/Silica Nanofiber Membranes for Wearable Textiles. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 13949–13956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraij, K.; Ammed, S.P.; Chingakham, C.; Ramasubramanian, B.; Ramakrishna, S.; Vasudevan, S.; Sujith, A. Electrospun Polyurethane Nanofiber Membranes for Microplastic and Nanoplastic Separation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 4636–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghajarieh, A.; Habibi, S.; Talebian, A. Biomedical Applications of Nanofibers. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2021, 94, 847–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameen, D.E.; Ahmed, S.; Lu, R.; Li, R.; Dai, J.; Qin, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; Liu, Y. Electrospun Nanofibers Food Packaging: Trends and Applications in Food Systems. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 6238–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xu, Z.; Lin, H.; Gao, J.; Song, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, R.; Geng, Y.; Wu, D. Scalable, High Flux and Durable Electrospun Photocrosslinked PVA Nanofibers-Based Membrane for Efficient Water Purification. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 727, 124024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. Photocatalytic Activity and Filtration Performance of Hybrid TiO2-Cellulose Acetate Nanofibers for Air Filter Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, K.K.; Konwar, A.; Borah, A.; Saikia, A.; Barman, P.; Hazarika, S. Cellulose Nanofiber Mediated Natural Dye Based Biodegradable Bag with Freshness Indicator for Packaging of Meat and Fish. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, K.; Augustine, R.; Zaszczynska, A.; Barman, M.; Jain, A.; Hasan, A.; Kalarikkal, N.; Sajkiewicz, P.; Thomas, S. Novel Drug Delivery Systems Based on Triaxial Electrospinning Based Nanofibers. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 163, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, A.; Han, Y.; Shi, Y.; Cheng, F.; Zhou, M.; Zhu, P.; Tan, L. Transition Sandwich Janus Membrane of Cellulose Acetate and Polyurethane Nanofibers for Oil–Water Separation. Cellulose 2022, 29, 1841–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.M.; Da Silva, B.L.; Sorrechia, R.; Pietro, R.C.L.R.; Chiavacci, L.A. Sustainable Antibacterial Activity of Polyamide Fabrics Containing ZnO Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 3667–3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Wang, X.; Ding, T.; Chakir, S.; Xu, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, H. Electrospinning Preparation of Nylon-6@ UiO-66-NH2 Fiber Membrane for Selective Adsorption Enhanced Photocatalysis Reduction of Cr (VI) in Water. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jiang, A.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Fu, C.; Yang, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, D. Synthesis of Tough and Hydrophobic Polyamide 6 for Self-Cleaning, Oil/Water Separation, and Thermal Insulation. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 12018–12027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcinkaya, B.; Strejc, M.; Yalcinkaya, F.; Spirek, T.; Louda, P.; Buczkowska, K.E.; Bousa, M. An Innovative Approach for Elemental Mercury Adsorption Using X-Ray Irradiation and Electrospun Nylon/Chitosan Nanofibers. Polymers 2024, 16, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartati, S.; Zulfi, A.; Maulida, P.Y.D.; Yudhowijoyo, A.; Dioktyanto, M.; Saputro, K.E.; Noviyanto, A.; Rochman, N.T. Synthesis of Electrospun PAN/TiO2/Ag Nanofibers Membrane as Potential Air Filtration Media with Photocatalytic Activity. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 10516–10525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Chai, M.; Mai, Z.; Liao, M.; Xie, X.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, H.; Dong, X.; Fu, X. Electrospinning Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) Based Nanofiberous Membranes Synergic with Plant Antibacterial Agent and Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) for Potential Wound Dressing. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, F.; Nabavi, S.R.; Omrani, A. Fabrication of Hydrophilic Hierarchical PAN/SiO2 Nanofibers by Electrospray Assisted Electrospinning for Efficient Removal of Cationic Dyes. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 25, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koozekonan, A.G.; Esmaeilpour, M.R.M.; Kalantary, S.; Karimi, A.; Azam, K.; Moshiran, V.A.; Golbabaei, F. Fabrication and Characterization of PAN/CNT, PAN/TiO2, and PAN/CNT/TiO2 Nanofibers for UV Protection Properties. J. Text. Inst. 2021, 112, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Mao, X.; Cheng, J.; Huang, L.; Tang, J. Advances in Wound Dressing Based on Electrospinning Nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e54746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Mu, Q.; Luo, Z.; Han, W.; Yang, H. One-Step Fabrication of Multifunctional TPU/TiO2/HDTMS Nanofiber Membrane with Superhydrophobicity, UV-Resistance, and Self-Cleaning Properties for Advanced Outdoor Protection. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 705, 135501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.; Xu, R.; Xia, R.; Cheng, D.; Yao, J.; Bi, S.; Cai, G.; Wang, X. Carbon Nanotube/Polyurethane Core–Sheath Nanocomposite Fibers for Wearable Strain Sensors and Electro-Thermochromic Textiles. Smart Mater. Struct. 2021, 30, 075022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, B.; Sel, E.; Kuyumcu Savan, E.; Ateş, B.; Köytepe, S. Recent Progress and Perspectives on Polyurethane Membranes in the Development of Gas Sensors. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2021, 51, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polymer Name | Commercial Name | Type and Key Properties | Supplier Name | Origin Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | Cellulose acetate (CA-398-10) | Semi-synthetic polymer derived from cellulose; 39.8% acetyl content; Tg ≈ 190 °C; | Eastman | Kingsport, TN, USA |

| PCL | Polycaprolactone (Mn) 80,000 | Aliphatic biodegradable polyester; low Tg (−60 °C), Tm ≈ 60 °C; high flexibility. | Sigma Aldrich | Burlington, MA, USA |

| PA6 | Ultramid® B24 | Synthetic polyamide with high crystallinity, Tg ≈ 50 °C, Tm ≈ 220 °C; good spinnability and mechanical strength | BASF | Ludwigshafen, Germany |

| PA6 | Econyl 27 | Chemically regenerated nylon 6 from waste; same structure as PA6 but higher purity; sustainable alternative | Econyl | Trento, Italy |

| PA11 | Rilsan® | Long-chain aliphatic bio-polyamide from castor oil; Tm ≈ 190 °C; low moisture uptake, high flexibility | Arkema | France, Colombes |

| PA12 | VESTAMID® L | Long-chain polyamide; Tm ≈ 178 °C; very low water absorption, high chemical resistance. | Evonik | Germany, Essen |

| PVB | Mowital B 60 H | Amorphous thermoplastic with hydroxyl groups (~18–22%); Tg ≈ 70 °C. | Kuraray | Germany, Hattersheim |

| PAN | Polyacrylonitrile | Semi-crystalline polymer; Tg ≈ 95 °C; precursor for carbon fibers; highly polar nitrile groups aid jet stability | Goodfellow | Huntingdon, UK |

| PVDF | Kynar 761A | Semi-crystalline fluoropolymer; Tm ≈ 170 °C; piezoelectric and hydrophobic; excellent chemical resistance | Arkema | Colombes, France |

| PU | Larithane AL 286 | Thermoplastic elastomer; Shore A ≈ 85; soft segment polyester-based; high elasticity, durable | Novotex | Gaggiano, Italy |

| PVA | Poval™ 5-88 | Water-soluble synthetic polymer; 88 mol% hydrolyzed; Mw ≈ 89,000–98,000. | Kuraray | Hattersheim, Germany |

| CS | Chitosan—Medium molecular weight | Natural cationic polysaccharide; deacetylation ~75–85%; Mw ≈ 190–310 kDa. | Sigma Aldrich | Burlington, MA, USA |

| Additive | Particle Size | Supplier Name |

|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | 200 nm | Nanografi (Düsseldorf, Germany) |

| ZnO NP | 30–50 nm | Nanografi |

| MgO NP | 55 nm | Nanografi |

| MgO NP | 500–1500 nm | Nanografi |

| CuO NP | 38 nm | Nanografi |

| CuO NP | 78 nm | Nanografi |

| CuO NP | 20 µm | Argaman (Jerusalem, Israel) |

| Ag | 100 nm | Nanografi |

| Graphene Oxide | <2 µm | Graphene-XT (Bologna, Italy) |

| CeO2 | 8–28 nm | Nanografi |

| Er2O3 | 8–90 nm | Nanografi |

| WO3 | 55 nm | Nanografi |

| MnO2 | <200 mesh size (micron powder) | Nanografi |

| Hyperbranched Polymer | PFLDHB-G4-PEG10K-OH | Polymer Factory (Stockholm, Sweden) |

| Hyperbranched Polymer | PFLDHB-G4-PEG10K-NH3+ | Polymer Factory |

| Solvent | Acronym | Supplier Name |

|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane | DCM | VWR International s.r.o (Stříbrná Skalice, Czech) |

| Formic acid | FA | VWR International s.r.o |

| Acetic acid | AA | VWR International s.r.o |

| Chloroform | CH | VWR International s.r.o |

| Methanol | Metha | VWR International s.r.o |

| Ethanol | Eth | VWR International s.r.o |

| Acetonitrile | Ace | VWR International s.r.o |

| Dimethylacetamide | DMAC | VWR International s.r.o |

| Dimethylformamide | DMF | VWR International s.r.o |

| Ethyl acetate | EA | VWR International s.r.o |

| Demineralized water | DW | - |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −20/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 315 | mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 125 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 25/22 | Rh%/°C |

| Polymer: Cellulose Acetate 398-10 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Solvents: DMAC/Ace | ||||

| Ratio of solvents | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 | 17.5 |

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–15k×–10k× |  |  |  | High viscosity no spinning |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 340 ± 35 | 410 ± 32 | 430 ± 42 ★ | - |

| Ratio of solvents | 9/1 | 7/3 | 3/7 | 1/9 |

| Solution concentrations w/v (%) | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| SEM Image Magnifications 0–10k×–10k× | No fiber only solution spray—wet surface |  |  | High viscosity No spinning |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | - | - | 1375 ± 126 | - |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −30/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 350 | mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 100–250 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 38/25 | Rh%/°C |

| Polymer: Polycaprolactone | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Solvents: Chloroform | |||

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | - | - | - |

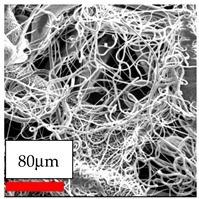

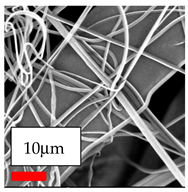

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–1k×–1k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 765 ± 152 | 1210 ± 134 | 1450 ± 164 |

| Solution concentrations w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 5/5 CH/Eth | 5/5 CH/Eth | 5/5 CH/Eth |

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–5k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 2430 ± 230 | 2870 ± 275 | 3055 ± 351 ★ |

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 5/5 CH/Metha | 5/5 CH/Metha | 5/5 CH/Metha |

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–5k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 3240 ± 420 | 4330 ± 441 | 4680 ± 530 |

| Solution concentrations w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 5/5 CH/(AA:FA 1:1)) | 5/5 CH/(AA:FA 1:1) | 5/5 CH/(AA:FA 1:1) |

| SEM Image Magnifications 500×–500×–1k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 5430 ± 539 | 5670 ± 610 | 6055 ± 647 |

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 5/5 CH/Ace | 5/5 CH/Ace | 5/5 CH/Ace |

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–500×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 1890 ± 280 | 1975 ± 315 | 2055 ± 421 |

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 7/3 (AA:FA 1:1)/CH | 7/3 (AA:FA 1:1)/CH | 7/3 (AA:FA 1:1)/CH |

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–5k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 525 ± 95 ★ | 640 ± 110 | 670 ± 153 |

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 15% (2/1) PCL/CA 398-3 | 15% (2/1) PCL/CAB CA 381-2 | 15% (2/1) PCL/CAP CA 482-0.5 |

| Ratio of solvents | 5/5 (AA:FA 1:1)/CH | 5/5 (AA:FA1:1)/CH | 5/5 (AA:FA 1:1)/CH |

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–5k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 825 ± 168 | 840 ± 175 | 725 ± 158 ★ |

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 15% (9/1) PCL/CS | 15% (6/4) PCL/PEO | |

| Ratio of solvents | 5/5 (AA:FA 1:1)/(CH:FA 1:1) | 5/5 (AA:FA 1:1)/CH | |

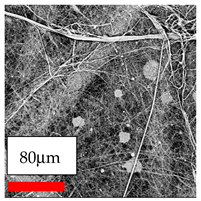

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–5k×–0 |  |  | |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 775 ± 163 ★ | 670 ± 145 ★ | |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −27/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 320 | mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 80–100 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 35/22 | Rh%/°C |

| Polymer: Polyamide 6 (Econyl 27) | |||

| Main Solvents: AA/FA | |||

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 2/1 | 2/1 | 2/1 |

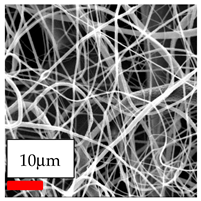

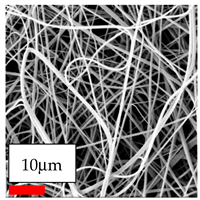

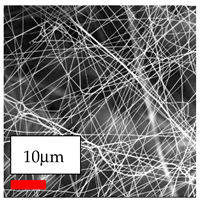

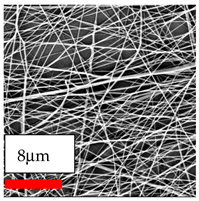

| SEM Image Magnifications 30k×–20k×–20k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 65 ± 29 ★ | 150 ± 53 | 200 ± 68 |

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 3/2 | 3/2 | 3/2 |

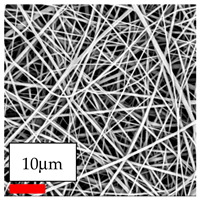

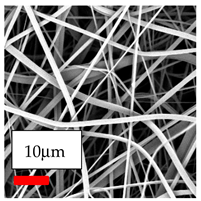

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–20k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 90 ± 35 | 135 ± 59 | 290 ± 83 |

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

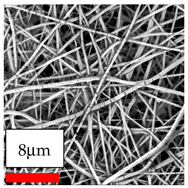

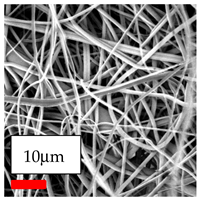

| Ratio of solvents | 1/1/1 AA/FA/DCM | 1/1/1 AA/FA/DCM | 1/1/1 AA/FA/DCM |

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 185 ± 63 | 440 ± 84 ★ | 620 ± 126 |

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

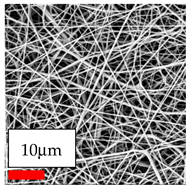

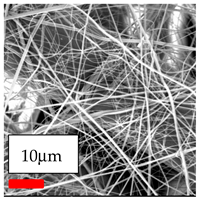

| Ratio of solvents | 1/1/1 AA/FA/CH | 1/1/1 AA/FA/CH | 1/1/1 AA/FA/CH |

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–10k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 130 ± 75 | 230 ± 80 ★ | 520 ± 113 ★ |

| Polymer: Polyamide 6 (BASF 24) | |||

| Main solvents: AA/FA | |||

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 1/1/1 AA/FA/DCM | 1/1/1 AA/FA/DCM | 1/1/1 AA/FA/DCM |

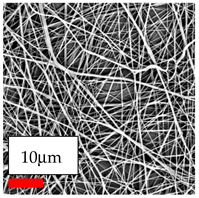

| SEM Image Magnifications 20k×–20k×–20k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 220 ± 135 | 310 ± 142 ★ | 400 ± 168 |

| Solution concentration w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 1/1/1 AA/FA/CH | 1/1/1 AA/FA/CH | 1/1/1 AA/FA/CH |

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–20k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 250 ± 95 | 400 ± 148 ★ | 650 ± 163 ★ |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −30/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 315 | mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 80–100 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 30/28 | Rh%/°C |

| Polymer: Polyamide 11, 12, and Polyvinyl Butyral | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Solvents: FA/DCM | |||

| Polymer: Polyamide 11 | |||

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 1/1 FA/DCM | 1/1 FA/DCM | 1/1 FA/DCM |

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–20k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 4590 ± 463 | 6455 ± 519 | 6745 ± 736 |

| Polymer: Polyamide 12 | |||

| Main solvents: FA/DCM | |||

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 10 |

| Ratio of solvents | 1/1 FA/DCM | 1/1 FA/DCM | FA |

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–1k×–1k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 620 ± 475 | 1465 ± 498 | 790 ± 517 ★ |

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 12.5 | 15 (2/1) PA11/ PVB | 15 (2/1) PA12/ PVB |

| Ratio of solvents | FA | 1/1 FA/DCM | 1/1 FA/DCM |

| SEM Image Magnifications 1k×–2.5k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 1510 ± 264 | 2395 ± 454 | 870 ± 224 ★ |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −30/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 350 | mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 100–150 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 21/23 | Rh%/°C |

| Polymer: Polyacrylonitrile | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Solvents: DMAC and DMF | |||

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 9 | 10 | 12.5 |

| Ratio of solvents | DMAC | DMAC | DMAC |

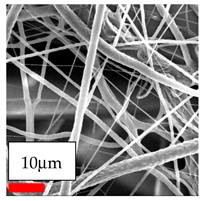

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

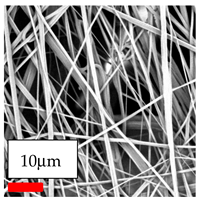

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 335 ± 132 | 350 ± 146 | 410 ± 155 |

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | DMF | DMF | DMF |

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 165 ± 94 | 210 ± 106 ★ | 545 ± 210 ★ |

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 17.5 | 20 | |

| Ratio of solvents | DMF | DMF | |

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–5k× |  |  | |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 720 ± 258 | 2670 ± 410 | |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −30/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 320 | mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 50–150 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 24/20 | Rh%/°C |

| Polymer: Polyvinylidene Fluoride | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Solvents: DMAC + 3%TEAB in DMF | |||

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 50/1 DMAC/TEAB in DMF | 50/1 DMAC/TEAB in DMF | 50/1 DMAC/TEAB in DMF |

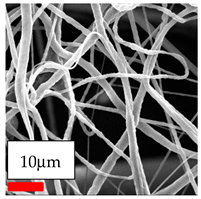

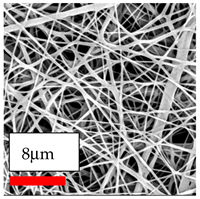

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 225 ± 124 | 325 ± 167 | 440 ± 189 |

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 17.5 | 20 | |

| Ratio of solvents | 50/1 DMAC/TEAB in DMF | 50/1 DMAC/TEAB in DMF | |

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–10k× |  |  | |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 495 ± 185 ★ | 590 ± 210 | |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −30/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 320 | mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 100–200 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 28/22 | Rh%/°C |

| Polymer: Polyurethane | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Solvents: DMF + 3%TEAB in DMF | |||

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 15 | 20 |

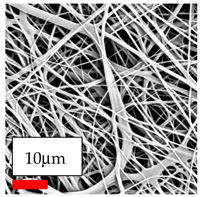

| Ratio of solvents | DMF | DMF | DMF |

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–5k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 445 ± 138 | 680 ± 165 | 1410 ± 215 |

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | DMF/TEAB in DMF 50/1 | DMF/TEAB in DMF 50/1 | DMF/TEAB in DMF 50/1 |

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 470 ± 174 | 560 ± 186 | 665 ± 242 ★ |

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 17.5 | 15 PU/PVB 10/1 | |

| Ratio of solvents | DMF/TEAB in DMF 50/1 | DMF | |

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–5k× |  |  | |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 720 ± 255 ★ | 450 ± 195 | |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −25/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 290 | Mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 80–120 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 30/25 | Rh%/°C |

| Polymer: Polyvinyl Butyral | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Solvents: Ethanol | |||

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 1/1 EtOH/CH | 1/1 EtOH/CH | 1/1 EtOH/CH |

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–5k×– |  |  | Too viscous polymer solution—no fibers |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 1455 ± 358 | 1580 ± 377 | |

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 1/1 EtOH/(AA:FA) | 1/1 EtOH/(AA:FA) | 1/1 EtOH/(AA:FA) |

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–10k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 720 ± 203 ★ | 890 ± 274 | 2640 ± 298 |

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12.5 | 15 |

| Ratio of solvents | 1/1 EtOH/EtAC | 1/1 EtOH/EtAC | 1/1 EtOH/EtAC |

| SEM Image Magnifications 10k×–5k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 510 ± 165 | 1630 ± 248 | 2150 ± 313 |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −25/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 350 | mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 100–250 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 20/30 | Rh%/°C |

| Polymer: Polyvinyl Alcohol | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Solvents: DW, EtOH, AA/FA (1/1), DMF | |||

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12 | 14 |

| Ratio of solvents | Demi-water | Demi-water | Demi-water |

| SEM Image Magnifications 1k×–10k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 360 ± 103 | 435 ± 152 ★ | 690 ± 194 |

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12 | 14 |

| Ratio of solvents | EtOH | EtOH | EtOH |

| SEM Image Magnifications 5k×–5k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 1160 ± 234 | 1280 ± 253 | 2430 ± 279 |

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12 | 14 |

| Ratio of solvents | AA/FA (1/1) | AA/FA (1/1) | AA/FA (1/1) |

| SEM Image Magnifications –20k×–5k× | Low viscosity, wet surface |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) ★ Best conditions | 245 ± 87 ★ | 1965 ± 268 | |

| Solution concen. w/v (%) | 10 | 12 | 14 |

| Ratio of solvents | DMF | DMF | DMF |

| SEM Image Magnifications –10k×–5k× | Low viscosity, wet surface |  |  |

| Fiber diameters (nm) | 570 ± 164 | 1090 ± 236 | |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −27/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 320 | mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 80–100 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 35/22 | Rh%/°C |

| Polymer: 15 w/v % PA6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Solvents and Ratio: AA/FA/CH 1/1/1 | |||

| Type of Nanoparticle | TiO2 200 nm | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 5 | 15 | 30 |

| SEM Images Magnifications 20k×–20k×–20k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | ZnO 30–50 nm | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 5 | 15 | 30 |

| SEM Images Magnifications 20k×–10k×–20k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | MgO 55 nm | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 5 | 15 | 30 |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | MgO 500–1500 nm | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 5 | 15 | 30 |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–5k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | CuO 38 nm | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 5 | 15 | 30 |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–5k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | CuO 78 nm | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 5 | 15 | 30 |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–5k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | CuO 20 micron | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 5 | 15 | 30 |

| SEM Images Magnifications 5k×–5k×–5k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | Ag | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 5 | 15 | 30 |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–5k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | Graphene Oxide | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 5 | 15 | 30 |

| SEM Images Magnifications 5k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | CeO2 | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 30 | |

| SEM Images Magnifications –5k×–5k× |  |  | |

| Type of Nanoparticle | CeO2/TiO2 | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | (15/15) | (30/15) | (15/30) |

| SEM Images Magnifications 15k×–10k×–25k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | CeO2/ZnO | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | (15/15) | (30/15) | (15/30) |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | Er2O3 | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 30 | |

| SEM Images Magnifications –10k×–10k× |  |  | |

| Type of Nanoparticle | Er2O3/TiO2 | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | (15/15) | (30/15) | (15/30) |

| SEM Images Magnifications 20k×–20k×–20k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | Er2O3/ZnO | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | (15/15) | (30/15) | (15/30) |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | WO3 | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 30 | |

| SEM Images Magnifications –10k×–10k× |  |  | |

| Type of Nanoparticle | WO3/TiO2 | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | (15/15) | (30/15) | (15/30) |

| SEM Images Magnifications 20k×–20k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | WO3/ZnO | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | (15/15) | (30/15) | (15/30) |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | MnO2 | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 30 | |

| SEM Images Magnifications –10k×–10k× |  |  | |

| Type of Nanoparticle | MnO2/GO | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | (15/15) | (30/15) | (15/30) |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | TiO2/GO | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | (15/15) | (30/15) | (15/30) |

| SEM Images Magnifications 20k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | CeO2/GO | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | (15/15) | (30/15) | (15/30) |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | WO3/GO | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | (15/15) | (30/15) | (15/30) |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | Er2O3/GO | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | (15/15) | (30/15) | (15/30) |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–10k×–10k× |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | Hyperbranched polymer | ||

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 1% HBPG4-OH | 1% HBPG4-NH | |

| SEM Images Magnifications 10k×–10k×– |  |  | |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −30/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 350 | mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 100–150 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 21/23 | Rh%/°C |

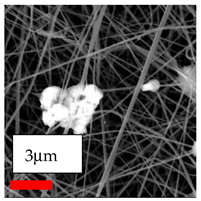

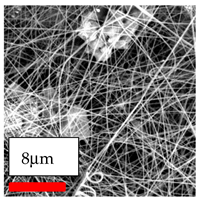

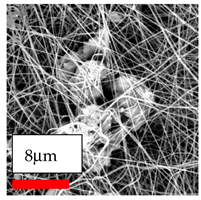

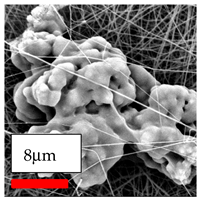

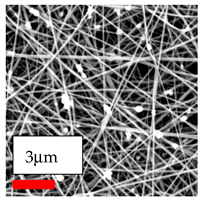

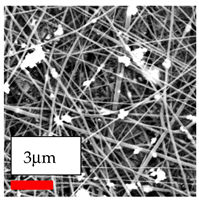

| Polymer: 15 w/v % PAN | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Solvents and Ratio: DMF | |||

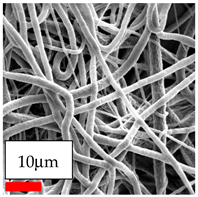

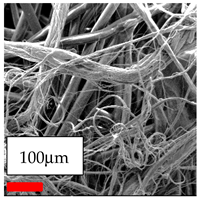

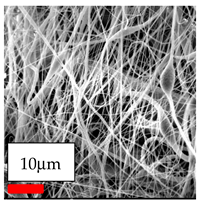

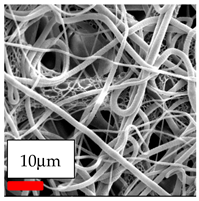

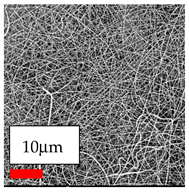

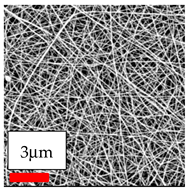

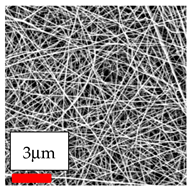

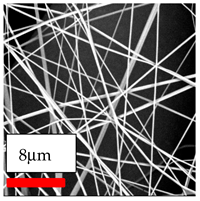

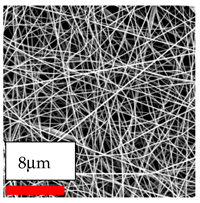

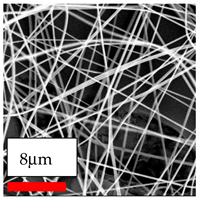

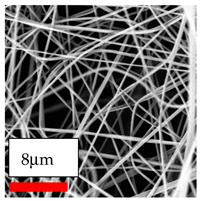

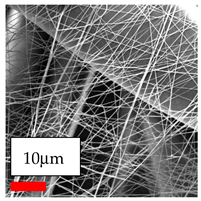

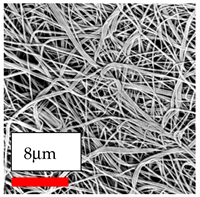

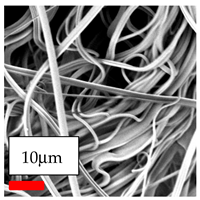

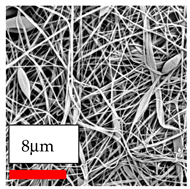

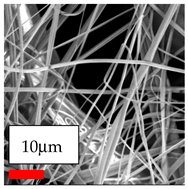

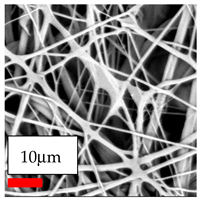

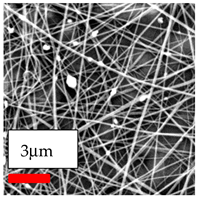

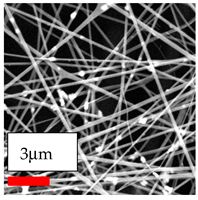

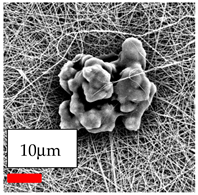

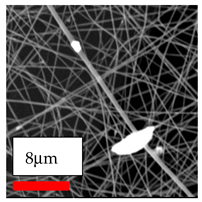

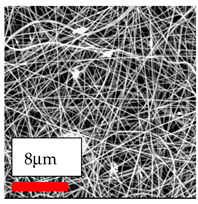

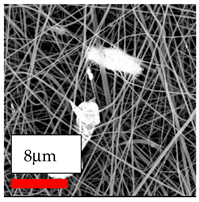

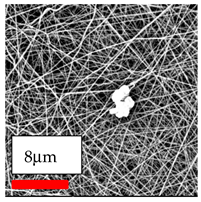

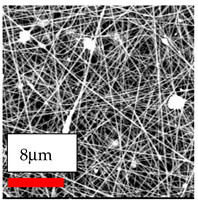

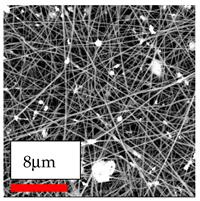

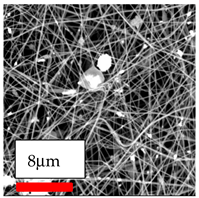

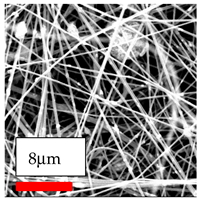

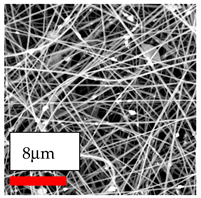

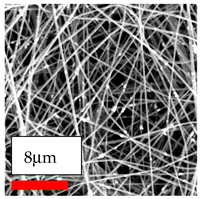

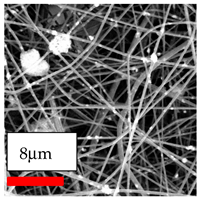

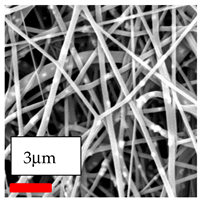

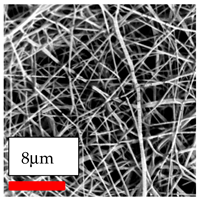

| Type of Nanoparticle | TiO2 NP—200 nm | ZnO—30–50 nm | MgO NP—55 nm |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 15 | 15 |

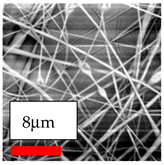

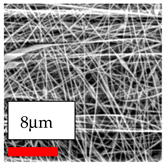

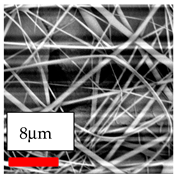

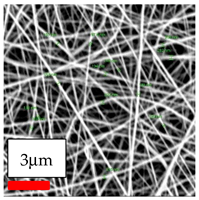

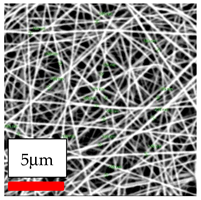

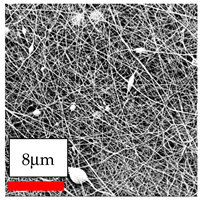

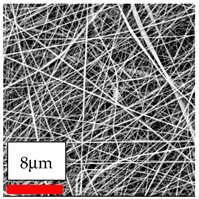

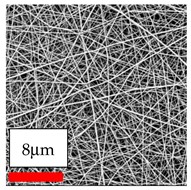

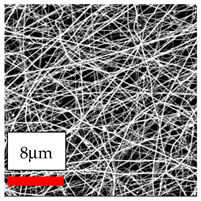

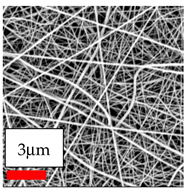

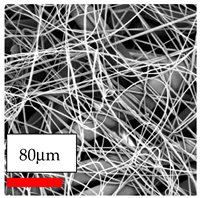

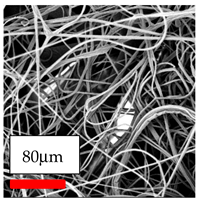

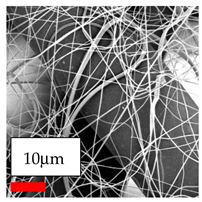

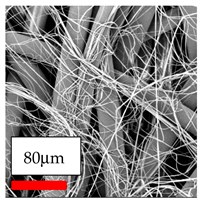

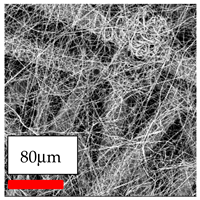

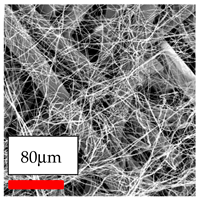

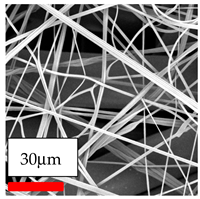

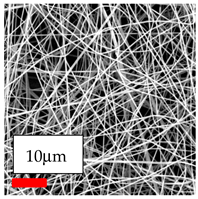

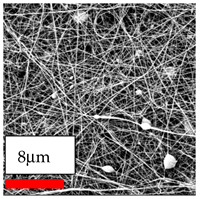

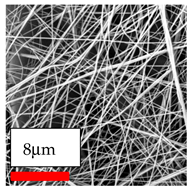

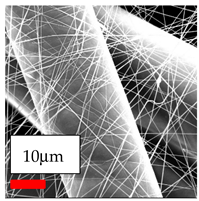

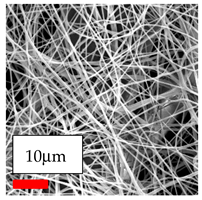

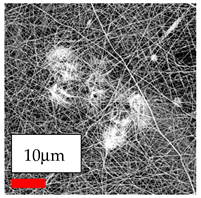

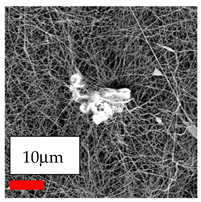

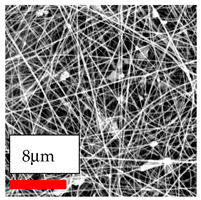

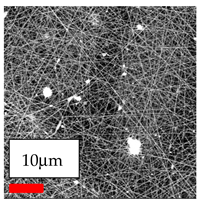

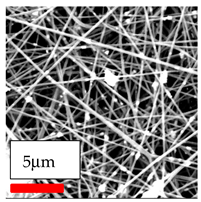

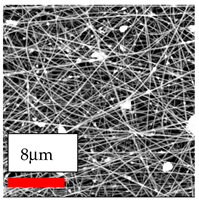

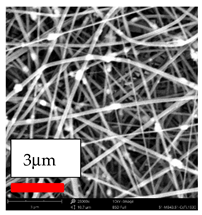

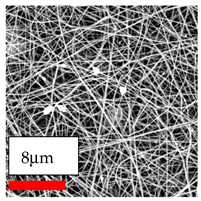

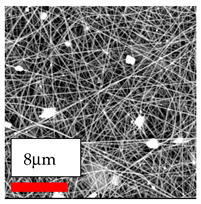

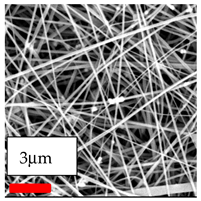

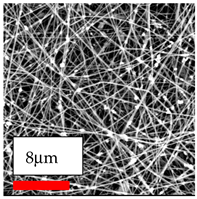

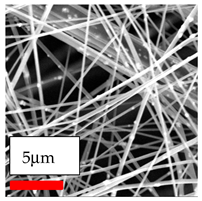

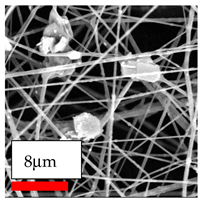

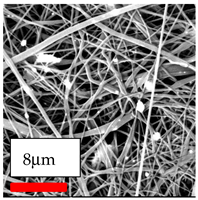

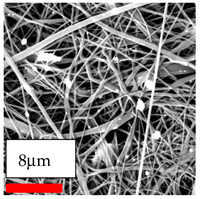

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

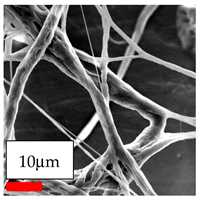

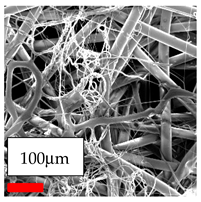

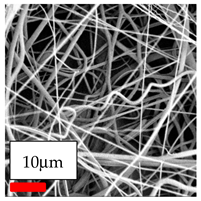

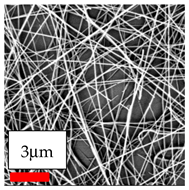

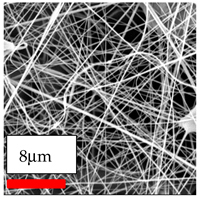

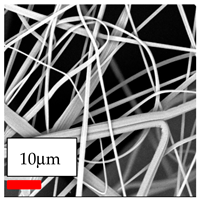

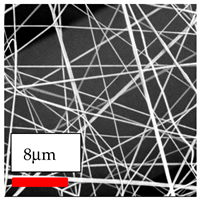

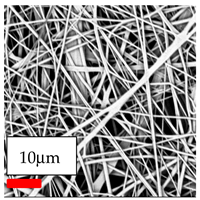

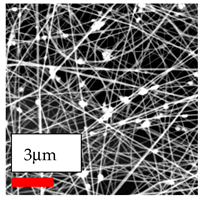

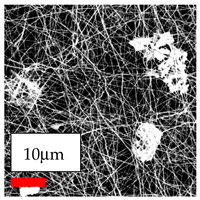

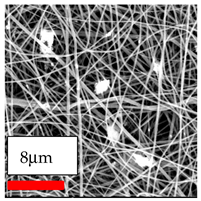

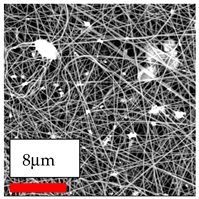

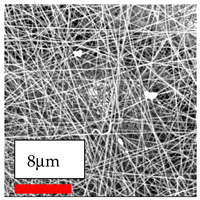

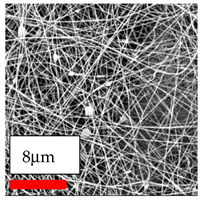

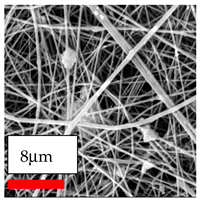

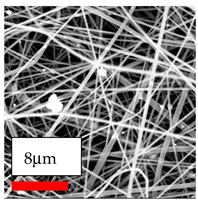

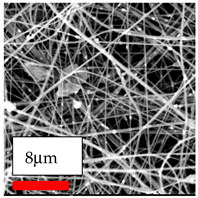

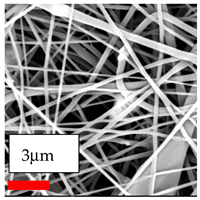

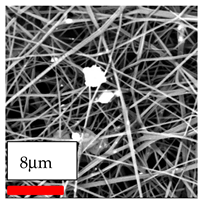

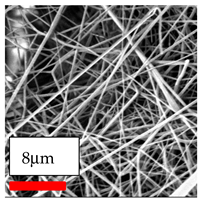

| Type of Nanoparticle | MgO/TiO2 NP | MgO/ZnO | |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15/15 | 15/15 | |

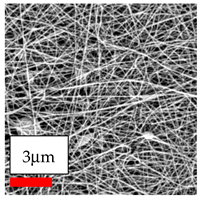

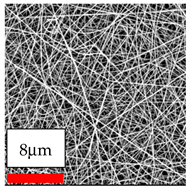

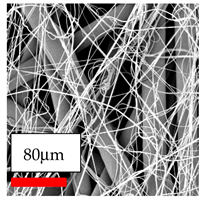

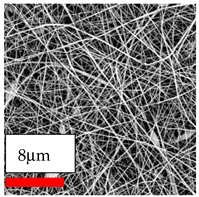

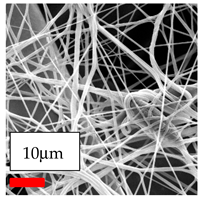

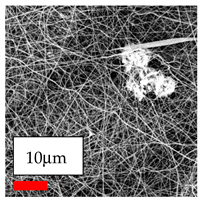

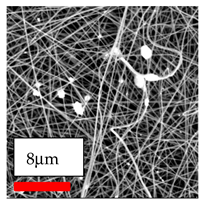

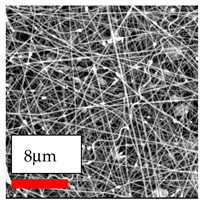

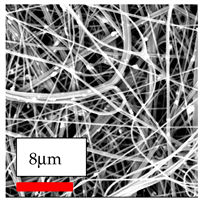

| SEM Images |  |  | |

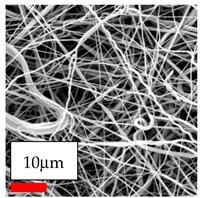

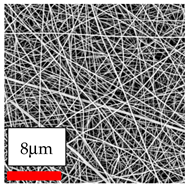

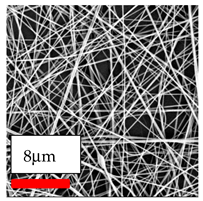

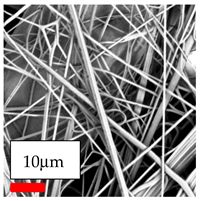

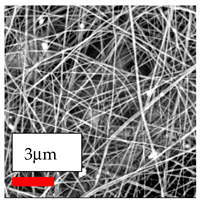

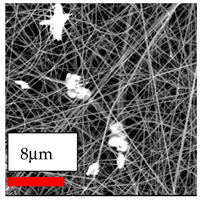

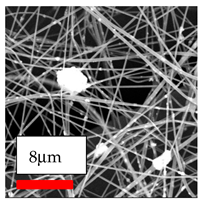

| Type of Nanoparticle | CeO2 | CeO2/TiO2 | CeO2/ZnO |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 15/15 | 15/15 |

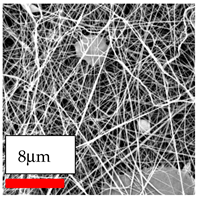

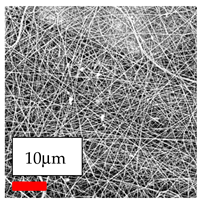

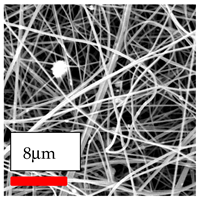

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

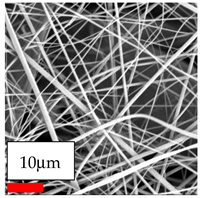

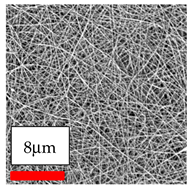

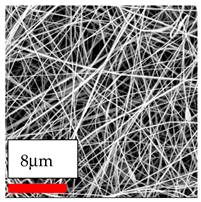

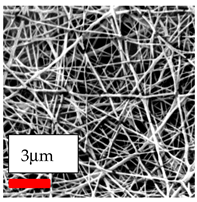

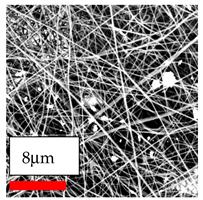

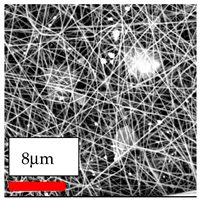

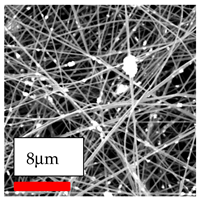

| Type of Nanoparticle | Er2O3 | Er2O3/TiO2 | Er2O3/ZnO |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 15/15 | 15/15 |

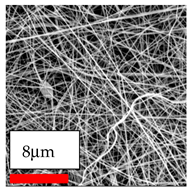

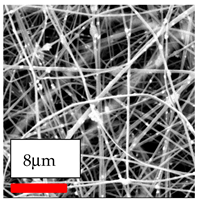

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | WO3 | WO3/TiO2 | WO3/ZnO |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 15/15 | 15/15 |

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | MnO2 | MnO2/TiO2 | MnO2/ZnO |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 15/15 | 15/15 |

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | GO | GO/TiO2 | GO/ZnO |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 15/15 | 15/15 |

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

| Parameters | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Applied voltage | −30/+70 | kV |

| Distance between electrodes | 350 | mm |

| Solution feeding rates | 100–150 | mbar/h |

| Solution feeding rates | 100 | mL/h |

| Nonwoven winding speed | 1 | mm/s |

| Humidity/Temperature | 21/23 | Rh%/°C |

| Polymer: 14.5 w/v % PU | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Solvents and Ratio: DMF | |||

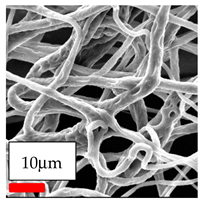

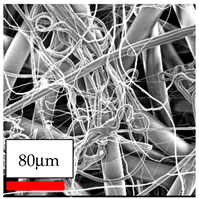

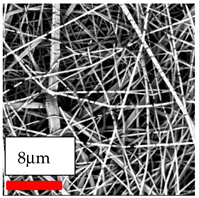

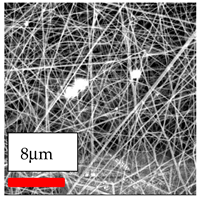

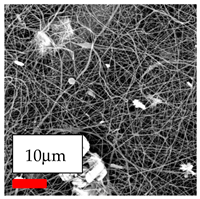

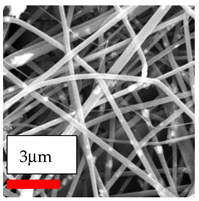

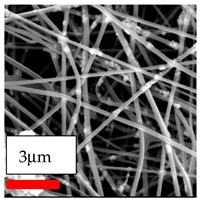

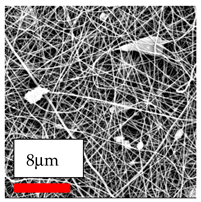

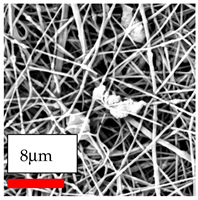

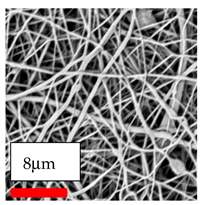

| Type of Nanoparticle | TiO2 NP—200 nm | ZnO—30–50 nm | MgO NP—55 nm |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

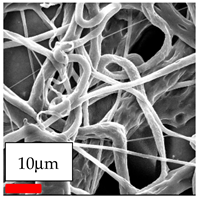

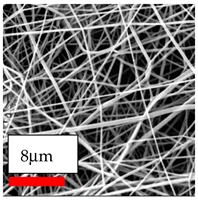

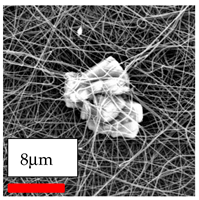

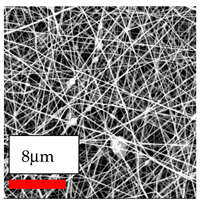

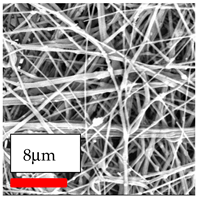

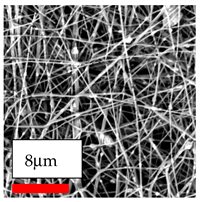

| Type of Nanoparticle | MgO/TiO2 NP | MgO/ZnO | |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15/15 | 15/15 | |

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | CeO2 | CeO2/TiO2 | CeO2/ZnO |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 15/15 | 15/15 |

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | WO3 | WO3/TiO2 | WO3/ZnO |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 15/15 | 15/15 |

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | MnO2 | MnO2/TiO2 | MnO2/ZnO |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 15/15 | 15/15 |

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

| Type of Nanoparticle | GrO | GrO/TiO2 | GrO/ZnO |

| Nanoparticle concen. w (%) | 15 | 15/15 | 15/15 |

| SEM Images |  |  |  |

| Polymer | Applications of Nanofibers | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| PA6 | Filtration membranes [112], sportwear and protective textiles [17], biomedical scaffolds [113], air and water purification [114] | Widely used in filtration thanks to the small fiber diameter. |

| PA11 | Biomedical devices, sensors [115], membrane separation, eco-friendly engineering applications [116] | Bio-based polymer for sustainable applications. |

| PA12 | Oil-water separation membranes, biomedical materials | Industrial filters due to low water absorption. |

| PVB | Air filtration [117], battery separators [118], sound-insulating materials [119] | Versatile and flexible nanofibers. |

| PCL | Tissue engineering scaffolds [60], drug delivery systems [61], wound healing applications [82] | Medical applications, thanks to biodegradability. |

| PAN | Filtration membranes [120], energy storage [121](supercapacitors), carbon nanofiber precursors [122], protective textiles [107] | Excellent thermal stability and chemical resistance for challenging applications. |

| PVDF | Battery separators [123], piezoelectric sensors [124,125], water treatment membranes [126], energy harvesting devices [127], food packaging [128] | Excellent weathering and chemical resistance. |

| PU | Wound dressings [129], biomedical scaffolds [130], breathable protective clothing [131], filtration membranes [132] | Flexible, elastic, suitable for apparel and wound healing. |

| PVA | Biomedical applications [133] (drug delivery, wound healing), food packaging [134], water filtration membranes [135] | hydrophilic, biodegradable, and non-toxic, widely used in biomedical fields. |

| CA | Air and water filtration [136], biodegradable packaging [137], drug delivery systems [138], membrane separation [139] | Exhibit excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability. |

| PA6/NP | Antibacterial textiles [140], photocatalytic membranes [141], self-cleaning surfaces [142], heavy metal removal from wastewater [143] | Enhances antibacterial, photocatalytic, and self-cleaning properties |

| PAN/NP | Filtration membranes [144], antibacterial materials [145], enhanced adsorption capacity [146], UV protection [147] | Provides enhanced photocatalytic activity, antibacterial behavior, and pollutant adsorption |

| PU/NP | Antimicrobial wound dressings [148], UV-resistant coatings [149], smart textiles [150], gas sensors [151] | Provides antimicrobial activity, UV resistance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yalcinkaya, B.; Buzgo, M. A Guide for Industrial Needleless Electrospinning of Synthetic and Hybrid Nanofibers. Polymers 2025, 17, 3019. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223019

Yalcinkaya B, Buzgo M. A Guide for Industrial Needleless Electrospinning of Synthetic and Hybrid Nanofibers. Polymers. 2025; 17(22):3019. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223019

Chicago/Turabian StyleYalcinkaya, Baturalp, and Matej Buzgo. 2025. "A Guide for Industrial Needleless Electrospinning of Synthetic and Hybrid Nanofibers" Polymers 17, no. 22: 3019. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223019

APA StyleYalcinkaya, B., & Buzgo, M. (2025). A Guide for Industrial Needleless Electrospinning of Synthetic and Hybrid Nanofibers. Polymers, 17(22), 3019. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17223019