Polymer-Based Artificial Solid Electrolyte Interphase Layers for Li- and Zn-Metal Anodes: From Molecular Engineering to Operando Visualization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamentals of SEI Layers on Metal Anodes

3. Molecular Engineering of Polymer-Based Artificial SEI Layers

3.1. Chemistry Classes and Architectures

3.2. Target Properties & Quantitative Metrics

Measurement Notes (How to Measure Each Metric)

- σ (ionic conductivity): Through-plane EIS using blocking electrodes; normalize by thickness/area; report the temperature (e.g., 25 °C) and humidity for hydrophilic films [36].

- Rct/RSEI: Extract these parameters from the EIS results using an explicitly defined equivalent circuit; identify the high-frequency semicircle attributed to the interphase; control the contact resistance and temperature [42].

- E, H, and Gc: Nanoindentation or AFM force–distance mapping are used to determine the elastic modulus (E) and hardness (H), while peel or double-cantilever beam (DCB) tests quantify the adhesion strength and critical fracture energy (Gc) [36].

- ηnuc (nucleation overpotential): The potential dip at the onset of galvanostatic deposition is recorded; report the current density, electrolyte, and rest history [42].

- Symmetric-cell lifetime: Specify J (mA cm−2), the areal capacity per cycle (mAh cm−2), stack pressure, and electrolyte/negative-to-positive (N/P) ratio [36].

- Aqueous-Zn metrics: Determine the HER current via chronoamperometry versus reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE), the corrosion rate by Tafel extrapolation or mass-loss measurements, and self-discharge by open circuit voltage (OCV) decay [36].

3.3. Design Parameters and Operando Metrics

- Zwitterionic or ionomeric side chains have emerged as effective motifs for promoting cation-selective transport while suppressing solvent co-transport. Such interphases facilitate uniform lithium plating, accompanied by reduced drift in Rct, as confirmed by LC-TEM and operando EIS measurements [39,41]. These findings highlight the role of molecular dipoles in achieving controlled ion flux across the SEI.

- Fluorinated or salt-philic side chains drive the formation of inorganic-rich, electronically insulating SEI layers, often enriched in LiF. This results in denser mosaic-type morphologies with suppressed porosity growth, as observed in operando LC-STEM and X-ray studies [34,37]. Such design principles leverage the strong interfacial stability of fluorinated chemistries to inhibit uncontrolled dendritic propagation.

- Incorporating ceramic fillers such as Al2O3 or LLZO into polymer matrices provides enhanced mechanical modulus and enables more homogeneous current distribution. Operando LC-TEM studies have shown that these hybrid systems reduce tip-growth probability and maintain smoother electrodeposition fronts, underscoring the importance of mechanical reinforcement in suppressing localized instabilities [35,38,40].

- Finally, dynamic cross-links or supramolecular bonding motifs impart self-healing capabilities to the artificial SEI. These reversible interactions enable crack recovery and sustain interfacial coverage during extended cycling. Recent advances have further demonstrated that supramolecular interaction frameworks within polymer electrolytes can regulate Li+ solvation dynamics and enhance interfacial homogeneity, thereby achieving stable lithium deposition [43]. Correspondingly, operando studies report stable plating morphologies and slower impedance rise when such adaptive networks are employed [36].

4. Artificial SEI Layers for Li-Metal Anodes: Recent Advances

5. Artificial SEI Layers for Zn-Metal Anodes: Unique Challenges and Solutions

6. Comparative Insights into Li- and Zn-Metal Polymer SEI Designs

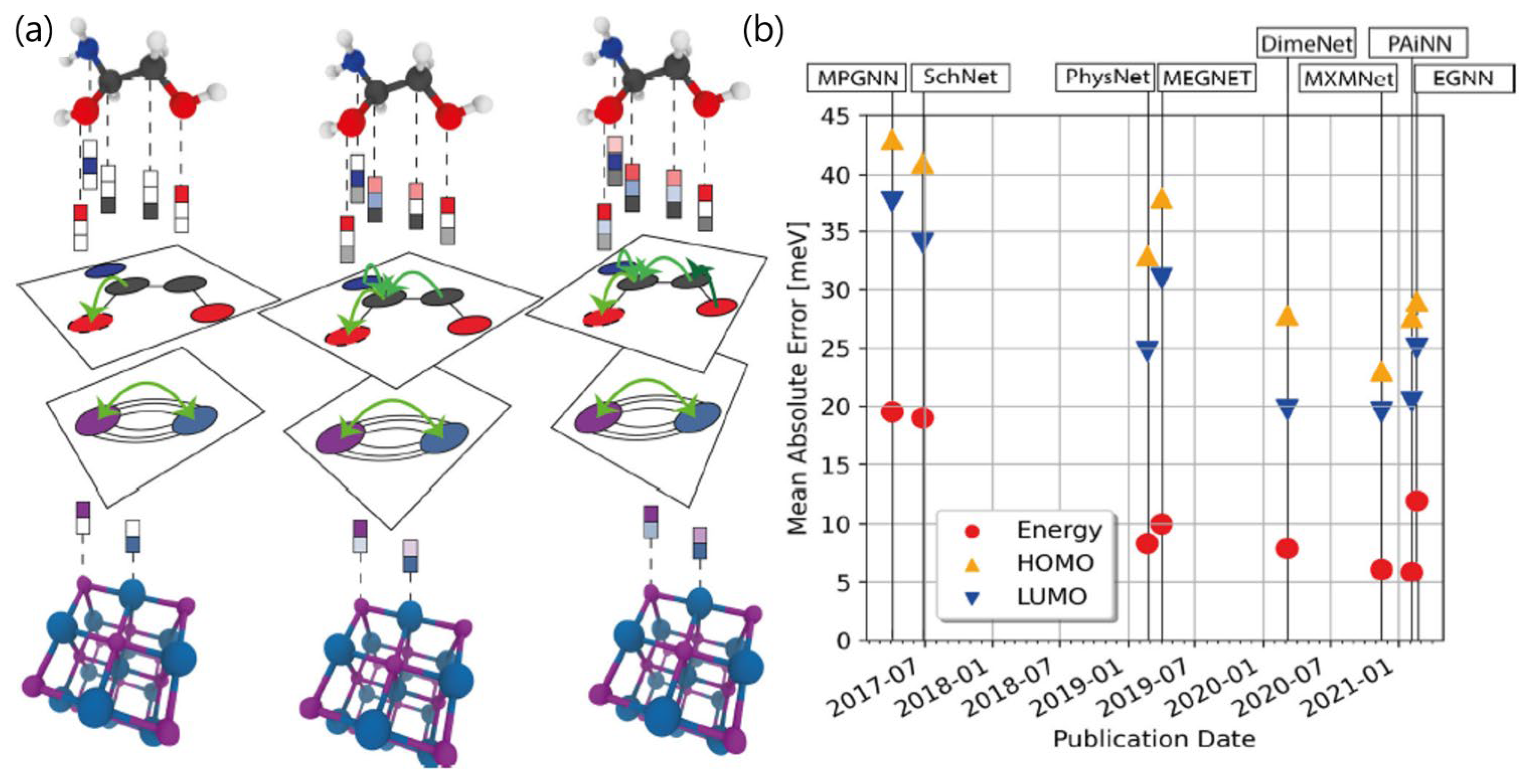

7. Operando Visualization Techniques: From Ex Situ Analysis to Real-Time Investigation

8. Outlook and Future Perspectives: Toward Rational Design and Application

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goodenough, J.B.; Park, K.S. The Li-Ion Rechargeable Battery: A Perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, P.G.; Freunberger, S.A.; Hardwick, L.J.; Tarascon, J.M. Li-O and Li-S batteries with high energy storage. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Zhang, X.Q.; Ding, F.; Huang, J.Q.; Xu, R.; Chen, X.; Yan, C.; Su, F.Y.; Chen, C.M.; Liu, X.J.; et al. Advanced Electrode Materials in Lithium Batteries: Retrospect and Prospect. Energy Mater. Adv. 2021, 2021, 1205324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, D.L.; Zhou, W.H.; Xie, F.X.; Ye, C.; Li, H.; Jaroniec, M.; Qiao, S.Z. Roadmap for advanced aqueous batteries: From design of materials to applications. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.C.; Ang, E.H.X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.F.; Ye, M.H.; Li, C.C. Challenges in the material and structural design of zinc anode towards high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 3330–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, E.; Menkin, S. Review-SEI: Past, Present and Future. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A1703–A1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.G.; Xu, W.; Xiao, J.; Cao, X.; Liu, J. Lithium Metal Anodes with Nonaqueous Electrolytes. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 13312–13348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, S.K.; Kim, J.; Lucht, B.L. Generation and Evolution of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Joule 2019, 3, 2322–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktekin, B.; Riegger, L.M.; Otto, S.K.; Fuchs, T.; Henss, A.; Janek, J. SEI growth on Lithium metal anodes in solid-state batteries quantified with coulometric titration time analysis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, R.; Schaefer, J.L.; Archer, L.A.; Coates, G.W. Suppression of Lithium Dendrite Growth Using Cross-Linked Polyethylene/Poly(ethylene oxide) Electrolytes: A New Approach for Practical Lithium-Metal Polymer Batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7395–7402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.L.; Sun, F.Y.; Liu, N.; Yang, H.B.; Cao, P.F. Ionic conductive polymers as artificial solid electrolyte interphase films in Li metal batteries—A review. Mater. Today 2020, 40, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Cai, Y.F.; Wu, H.M.; Yu, Z.; Yan, X.Z.; Zhang, Q.H.; Gao, T.D.Z.; Liu, K.; Jia, X.D.; Bao, Z.N. Polymers in Lithium-Ion and Lithium Metal Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.J.; Choudhury, S.; Paul, N.; Thienenkamp, J.H.; Lennartz, P.; Gong, H.X.; Muller-Buschbaum, P.; Brunklaus, G.; Gilles, R.; Bao, Z.N. Effects of Polymer Coating Mechanics at Solid-Electrolyte Interphase for Stabilizing Lithium Metal Anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamwattana, O.; Park, H.; Kim, J.; Hwang, I.; Yoon, G.; Hwang, T.H.; Kang, Y.S.; Park, J.; Meethong, N.; Kang, K. High-Dielectric Polymer Coating for Uniform Lithium Deposition in Anode-Free Lithium Batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 4416–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, F.; Mao, J.; Guo, Z. Developing artificial solid-state interphase for Li metal electrodes: Recent advances and perspective. Energy Mater. Devices 2023, 1, 9370005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Liu, Q.; Xu, L.; Zuo, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X.; Mai, L. Zwitterionic Bifunctional Layer for Reversible Zn Anode. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 1719–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Liu, Y.; Ren, X.Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.Z.; Miao, Y.J.; Ren, F.Z.; Wei, S.Z.; Ma, J.M. Different surface modification methods and coating materials of zinc metal anode. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 66, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.X.; Nai, J.; Luan, D.Y.; Tao, X.Y.; Lou, X.W. Surface engineering toward stable lithium metal anodes. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadf1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Zhong, C.L.; Liu, J.H.; Wang, Z.H.; Chao, D.L. Advanced technology for Li/Na metal anodes: An in-depth mechanistic understanding. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 3872–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodico, J.J.; Mecklenburg, M.; Chan, H.L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Ling, X.Y.; Regan, B.C. Operando spectral imaging of the lithium ion battery’s solid-electrolyte interphase. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.W.; Cui, Y.; Vila, R.; Li, Y.B.; Zhang, W.B.; Zhou, W.J.; Chiu, W. Cryogenic Electron Microscopy for Energy Materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 3505–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Li, X.Y.; Bai, S.; Zou, Y.C.; Lu, B.Y.; Zhang, M.H.; Ma, X.M.; Chang, Z.; Meng, Y.S.; Gu, M. Conformal three-dimensional interphase of Li metal anode revealed by low-dose cryoelectron microscopy. Matter 2021, 4, 3741–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Han, B.; Yang, X.M.; Deng, Z.P.; Zou, Y.C.; Shi, X.B.; Wang, L.P.; Zhao, Y.S.; Wu, S.D.; Gu, M. Three-dimensional visualization of lithium metal anode via low-dose cryogenic electron microscopy tomography. Iscience 2021, 24, 103418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Xia, Y.F.; Zeng, R.; Luo, Z.; Wu, X.X.; Hu, X.Z.; Lu, J.; Gazit, E.; Pan, H.G.; Hong, Z.J.; et al. Ordered planar plating/stripping enables deep cycling zinc metal batteries. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K. Electrolytes and interphases in Li-ion batteries and beyond. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11503–11618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.N.; Li, X.L.; Zhang, S.L.; Yang, F.H.; Zeng, X.H.; Zhang, S.; Bo, G.Y.; Wang, C.S.; Guo, Z.P. Designing Dendrite-Free Zinc Anodes for Advanced Aqueous Zinc Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2001263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Wang, Z.Q.; Tawiah, B.; Wang, Y.D.; Chan, C.Y.; Fei, B.; Pan, F. Recent advances in zinc anodes for high-performance aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2020, 70, 104523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrayer, J.D.; Apblett, C.A.; Harrison, K.L.; Fenton, K.R.; Minteer, S.D. Mechanical studies of the solid electrolyte interphase on anodes in lithium and lithium ion batteries. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 060543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, C.; Newman, J. The impact of elastic deformation on deposition kinetics at lithium/polymer interfaces. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, A396–A404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, G.; Yan, J.-M.; Ma, J.-L.; Liu, T.; Shi, M.-M.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, M.-M.; Tang, J.-L.; Zhang, X.-B. Hybrid solid electrolyte enabled dendrite-free Li anodes for high-performance quasi-solid-state lithium-oxygen batteries. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, nwaa150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youk, G.; Kim, J.; Chae, O.B. Improving Performance and Safety of Lithium Metal Batteries Through Surface Pretreatment Strategies. Energies 2025, 18, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Yin, J.; Gao, X.; Sharma, A.; Chen, P.; Hong, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zheng, J.; Deng, Y.; Joo, Y.L.; et al. Production of fast-charge Zn-based aqueous batteries via interfacial adsorption of ion-oligomer complexes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenck, L.; Sethi, G.K.; Maslyn, J.A.; Balsara, N.P. Factors That Control the Formation of Dendrites and Other Morphologies on Lithium Metal Anodes. Front. Energy Res. 2019, 7, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachraoui, W.; Pauer, R.; Battaglia, C.; Erni, R. Operando Electrochemical Liquid Cell Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy Investigation of the Growth and Evolution of the Mosaic Solid Electrolyte Interphase for Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 20434–20444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushima, A.; So, K.P.; Su, C.; Bai, P.; Kuriyama, N.; Maebashi, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Bazant, M.Z.; Li, J. Liquid cell transmission electron microscopy observation of lithium metal growth and dissolution: Root growth, dead lithium and lithium flotsams. Nano Energy 2017, 32, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Ren, X.; Hu, L.; Teng, W.; Wang, X.; Wu, G.; Liu, J.; Nan, D.; Yu, X. Functional Polymer Materials for Advanced Lithium Metal Batteries: A Review and Perspective. Polymers 2022, 14, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.J.; Lai, J.C.; Liao, S.L.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.L.; Yu, W.L.; Gong, H.X.; Gao, X.; Yang, Y.F.; Qin, J.; et al. A salt-philic, solvent-phobic interfacial coating design for lithium metal electrodes. Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overhoff, G.M.; Ali, M.Y.; Brinkmann, J.P.; Lennartz, P.; Orthner, H.; Hammad, M.; Wiggers, H.; Winter, M.; Brunklaus, G. Ceramic-in-Polymer Hybrid Electrolytes with Enhanced Electrochemical Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 53636–53647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Liu, M.; Su, K.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, N.W.; Yu, L. Polymer Zwitterion-Based Artificial Interphase Layers for Stable Lithium Metal Anodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 57489–57496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; He, X. PEO based polymer-ceramic hybrid solid electrolytes: A review. Nano Converg. 2021, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Chen, F.; Martinez-Ibanez, M.; Feng, W.; Forsyth, M.; Zhou, Z.; Armand, M.; Zhang, H. A reflection on polymer electrolytes for solid-state lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Cui, Y.; Bao, Z. Design Principles of Artificial Solid Electrolyte Interphases for Lithium-Metal Anodes. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2020, 1, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ma, T.; Hu, L.; Ren, X.; Sun, X.; Yu, X. Supramolecular interaction chemistry in polymer electrolytes towards stable lithium metal batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 107, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Li, J.; Brushett, F.R.; Bazant, M.Z. Transition of Lithium Growth Mechanisms in Liquid Electrolytes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 3221–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.N.; Kazyak, E.; Chadwick, A.F.; Chen, K.H.; Zhang, J.G.; Thornton, K.; Dasgupta, N.P. Dendrites and Pits: Untangling the Complex Behavior of Lithium Metal Anodes through Operando Video Microscopy. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, P. Designing polymer coatings for lithium metal protection. Nanotechnology 2022, 33, 112501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Yang, A.; Omar, A.; Ma, Q.; Tietz, F.; Guillon, O.; Mikhailova, D. Recent Advances in Stabilization of Sodium Metal Anode in Contact with Organic Liquid and Solid-State Electrolytes. Energy Technol. 2022, 10, 2200149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, F.; Lee, J.Z.; Lee, M.H.; Alvarado, J.; Schroeder, M.A.; Yang, Y.; et al. Quantifying inactive lithium in lithium metal batteries. Nature 2019, 572, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Lee, H.; Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Du, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, J.-G.; Whittingham, M.S.; Xiao, J.; Liu, J. High-energy lithium metal pouch cells with limited anode swelling and long stable cycles. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, Z.; Kong, X.; Kim, S.C.; Boyle, D.T.; Qin, J.; Bao, Z.; Cui, Y. Liquid Electrolyte: The Nexus of Practical Lithium Metal Batteries. Joule 2022, 6, 588–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, X.; Cheng, X.B.; Guo, C.; Yu, F.; Bao, W.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q. Working Principles of Lithium Metal Anode in Pouch Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2202518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Xu, B.; Wang, C. Dendrite-Free Zn Anode Modified by Organic Coating for Stable Aqueous Zinc Ion Batteries. Batteries 2024, 10, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Wang, W.; Liang, Z.; Wang, D.; Deng, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Yu, J.; Yang, G. Designing Highly Reversible and Stable Zn Anodes for Next-Generation Aqueous Batteries. Batteries 2025, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; He, G. Opportunities and challenges of zinc anodes in rechargeable aqueous batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 11987–12001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Wang, K.; Pei, P.; Wei, M.; Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, P. Zinc dendrite growth and inhibition strategies. Mater. Today Energy 2021, 20, 100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, M.; Kim, B.; Jung, H.; Yim, K.; Ryu, M.; Doo, G.S.; Choi, J.H.; Heo, J.; Im, S.G.; et al. Tailored Polymer-Based SEI via iCVD for Stable Zinc Metal Anodes in Aqueous Batteries through Modulation of Hydrophilicity and Elasticity to Inhibit Hydrogen Evolution Reactions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e07730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Wang, L.Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Huang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, K.X.; Chen, J.S. Toward Hydrogen-Free and Dendrite-Free Aqueous Zinc Batteries: Formation of Zincophilic Protective Layer on Zn Anodes. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.P.; Sorrentino, A.; Fauth, F.; Yousef, I.; Simonelli, L.; Frontera, C.; Ponrouch, A.; Tonti, D.; Palacin, M.R. Synchrotron radiation based operando characterization of battery materials. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 1641–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M.; Sasaki, T.; Villevieille, C.; Novak, P. Combined operando X-ray diffraction-electrochemical impedance spectroscopy detecting solid solution reactions of LiFePO4 in batteries. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Sun, N.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Wang, J. Tracking Battery Dynamics by Operando Synchrotron X-ray Imaging: Operation from Liquid Electrolytes to Solid-State Electrolytes. Acc. Mater. Res. 2021, 2, 1177–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, P.M.; Grover, A.; Jin, N.; Severson, K.A.; Markov, T.M.; Liao, Y.H.; Chen, M.H.; Cheong, B.; Perkins, N.; Yang, Z.; et al. Closed-loop optimization of fast-charging protocols for batteries with machine learning. Nature 2020, 578, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, K.T.; Davies, D.W.; Cartwright, H.; Isayev, O.; Walsh, A. Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 2018, 559, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.J.; Peng, B.; Wu, Y. Pressure-Driven and Creep-Enabled Interface Evolution in Sodium Metal Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 26533–26541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y.; Hasegawa, G.; Shima, K.; Inada, M.; Enomoto, N.; Akamatsu, H.; Hayashi, K. Insights into Sodium Ion Transfer at the Na/NASICON Interface Improved by Uniaxial Compression. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2, 2913–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarak, M.H.; Mimona, M.A.; Islam, M.A.; Hossain, N.; Zohura, F.T.; Imtiaz, I.; Rimon, M.I.H. Scope of machine learning in materials research—A review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2023, 18, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. Machine learning in materials research: Developments over the last decade and challenges for the future. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2024, 33, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, P.; Neubert, M.; Eberhard, A.; Torresi, L.; Zhou, C.; Shao, C.; Metni, H.; van Hoesel, C.; Schopmans, H.; Sommer, T. Graph neural networks for materials science and chemistry. Commun. Mater. 2022, 3, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-Q.; Wu, G.; Arce-Ramos, J.M.; Lau, Y.H.; Ng, M.-F. Enabling accurate modelling of materials for a solid electrolyte interphase in lithium-ion batteries using effective machine learning interatomic potentials. Mater. Horiz. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Gu, Q.; Zheng, S. Machine Learning-Assisted Simulations and Predictions for Battery Interfaces. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 7, 2400626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Design Parameters | Target Interfacial Function | Operando/Diagnostic Observable | Representative Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic/ionomer side-chains | Cation-selective transport; suppressed solvent co-transport | Planar plating in LC-TEM; lower Rct drift (operando EIS) | [39,41] |

| Fluorinated/salt-philic side-chains | Inorganic-rich, electronically insulating SEI (e.g., LiF-rich) | Denser mosaic SEI; suppressed porosity growth (operando LC-STEM/X-ray) | [34,37] |

| Ceramic fillers (Al2O3, LLZO) in polymer | Raised modulus; homogeneous current distribution | Reduced tip-growth probability; smoother front in LC-TEM | [35,38,40] |

| Dynamic cross-links/supramolecular bonding | Self-healing of microcracks; coverage retention | Stable plating morphology under cycling; slower impedance rise | [36] |

| Aspect | Li-Metal Anodes | Zn-Metal Anodes |

|---|---|---|

| Operating environment and failure modes | Operates in non-aqueous carbonate or ether electrolytes under a highly reducing potential (−3.04 V vs. SHE). Unstable inorganic SEI formation leads to electron-driven dendritic growth and accumulation of inactive lithium. | Functions in aqueous or mildly alkaline electrolytes (−0.76 V vs. SHE). Corrosion, hydrogen evolution, and ion-depletion-driven mossy growth are the primary degradation pathways. |

| Mechanical and interfacial stress | Large volume fluctuation (>10%) during cycling requires a stiff yet elastic SEI to prevent cracking and delamination. | Moderate volume change but strong hydration-induced swelling demands cohesive and hydrophobic polymer coatings. |

| Design priorities | High modulus (>1 GPa) and fracture toughness to suppress dendrite penetration while maintaining electronic insulation and interfacial adhesion. | Hydration resistance, zincophilicity for homogeneous Zn2+ flux, and inhibition of hydrogen evolution and corrosion. |

| Representative polymer design | PVDF-HFP, PAN, and PEO-based copolymers, often combined with LiF or Li3N fillers to enhance mechanical robustness and ion selectivity. | Polyamide, polyacrylate, PVA, chitosan, and zwitterionic copolymers containing Zn-coordinating amide or hydroxyl groups. |

| Targeted interfacial function | Uniform Li+ transport, suppression of filament nucleation, and self-healing adhesion at the Li–polymer interface. | Zincophilic coordination networks ensuring uniform Zn2+ transport, reduced hydration, and hydrophobic shielding against HER. |

| Operando readouts and key metrics | Ionic conductivity (σ), Li+ transference number (t+), charge-transfer resistance (Rct or RSEI), nucleation overpotential (ηnuc), and modulus (E/H/Gc). LC-TEM and EIS reveal crack arrest and filament deflection in reinforced polymers. | Coulombic efficiency (CE), Rct, corrosion current density, and hydrogen-evolution rate (HER). Optical and neutron reflectometry demonstrate planar Zn plating and bubble suppression. |

| Representative examples | Wang et al. reported a LAGP–PVDF-HFP hybrid SEI exhibiting a modulus of 25 GPa and uniform Li deposition [30]. | Youk et al. demonstrated LiPAA and PDMS coatings achieving dendrite-free Zn cycling for over 8000 h [31]. |

| Design implication | The Li system demands a delicate balance between rigidity and elasticity to accommodate extreme reduction and mechanical stress. | The Zn system relies on hydrophobicity and Zn-affinity to stabilize aqueous interfaces and mitigate HER-driven degradation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, J.-H.; Bae, J. Polymer-Based Artificial Solid Electrolyte Interphase Layers for Li- and Zn-Metal Anodes: From Molecular Engineering to Operando Visualization. Polymers 2025, 17, 2999. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222999

Han J-H, Bae J. Polymer-Based Artificial Solid Electrolyte Interphase Layers for Li- and Zn-Metal Anodes: From Molecular Engineering to Operando Visualization. Polymers. 2025; 17(22):2999. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222999

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Jae-Hee, and Joonho Bae. 2025. "Polymer-Based Artificial Solid Electrolyte Interphase Layers for Li- and Zn-Metal Anodes: From Molecular Engineering to Operando Visualization" Polymers 17, no. 22: 2999. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222999

APA StyleHan, J.-H., & Bae, J. (2025). Polymer-Based Artificial Solid Electrolyte Interphase Layers for Li- and Zn-Metal Anodes: From Molecular Engineering to Operando Visualization. Polymers, 17(22), 2999. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222999