Buckling Analysis of Extruded Polystyrene Columns with Various Slenderness Ratios

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Buckling Stress Determination

2.2. Buckling Stress Predicted from the Compression Test Using Short Column

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

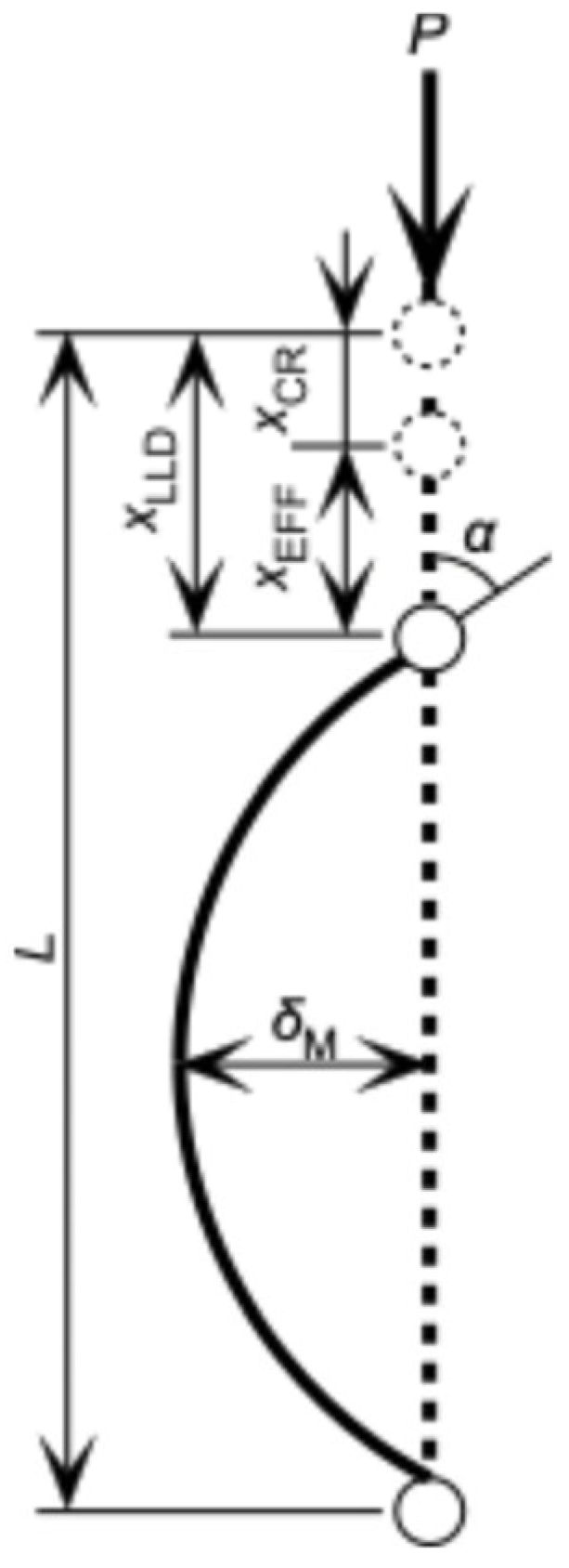

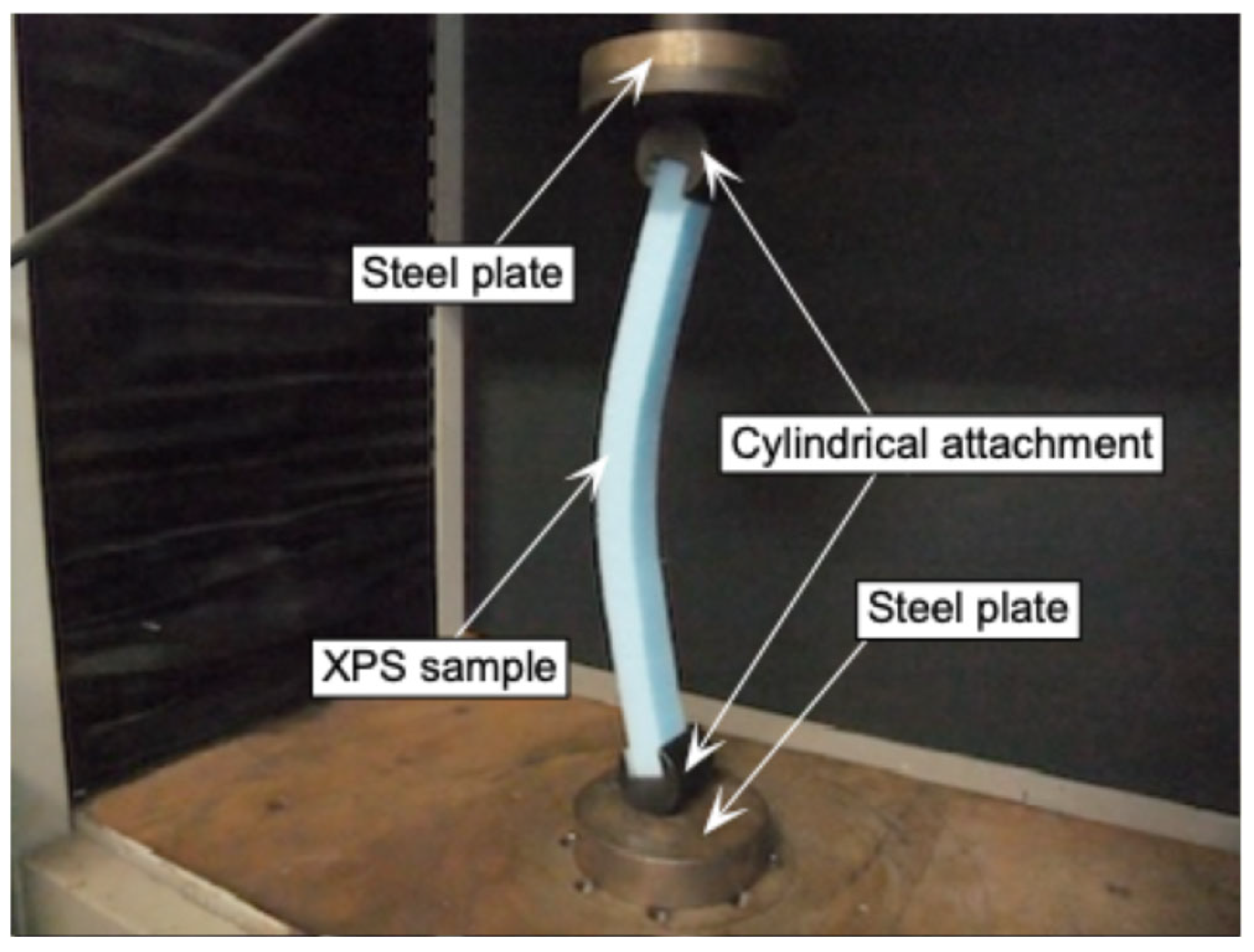

3.2. Buckling Tests

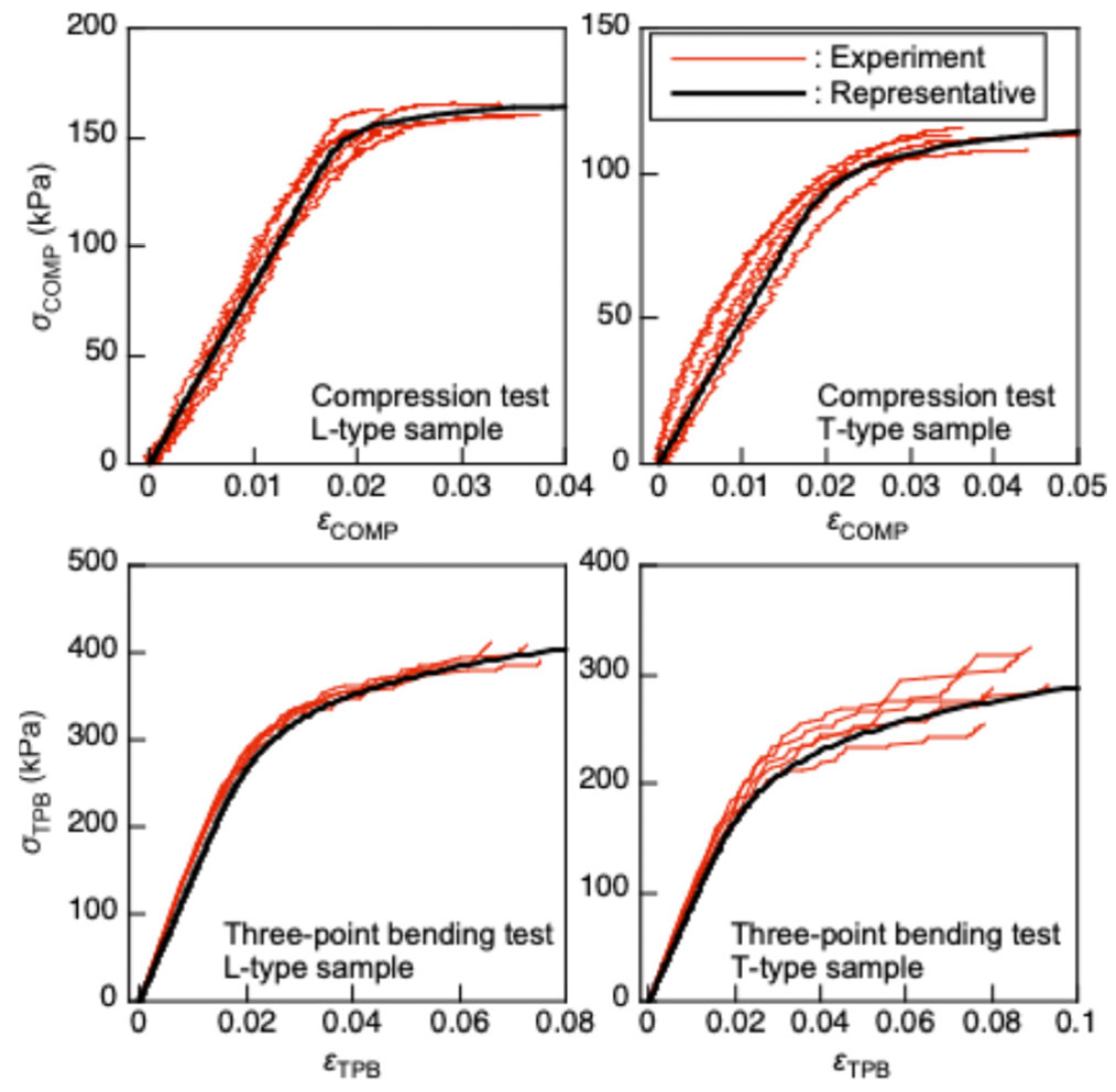

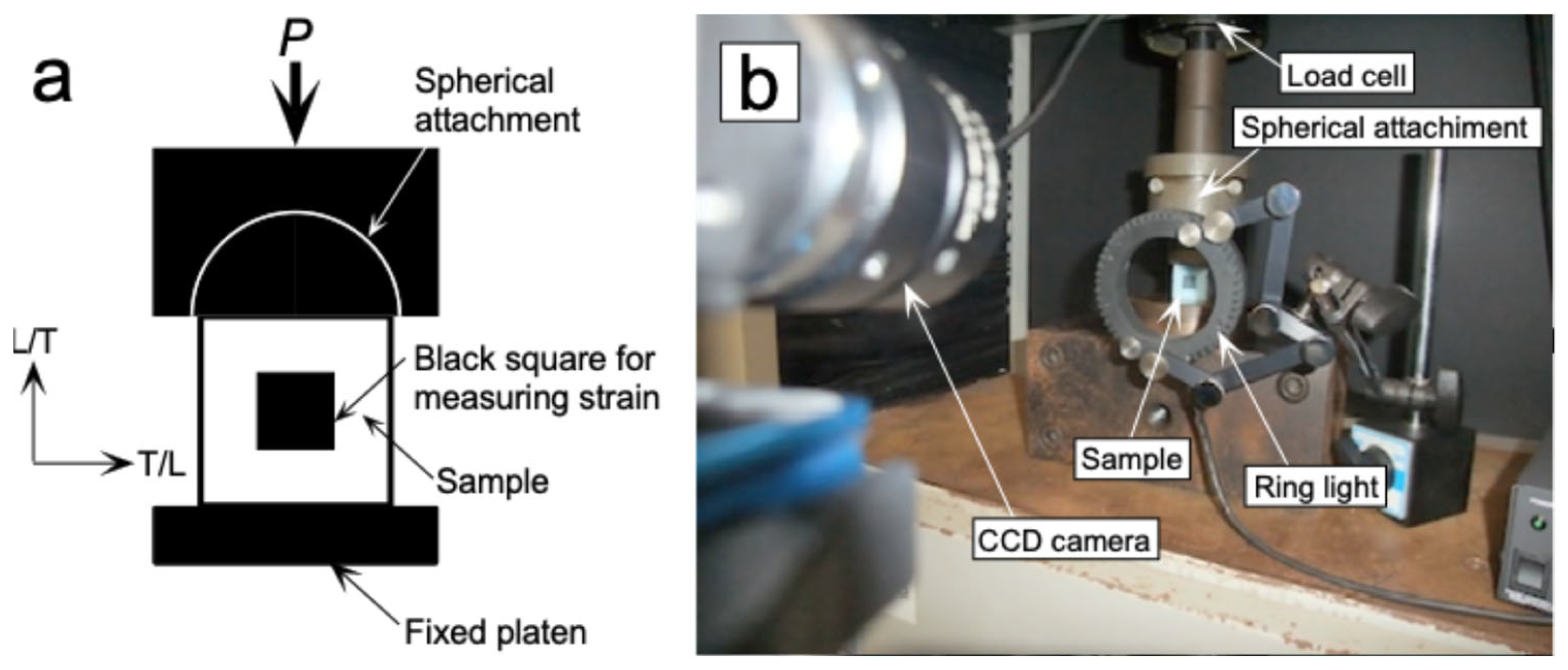

3.3. Compression Tests Using Cubic Samples

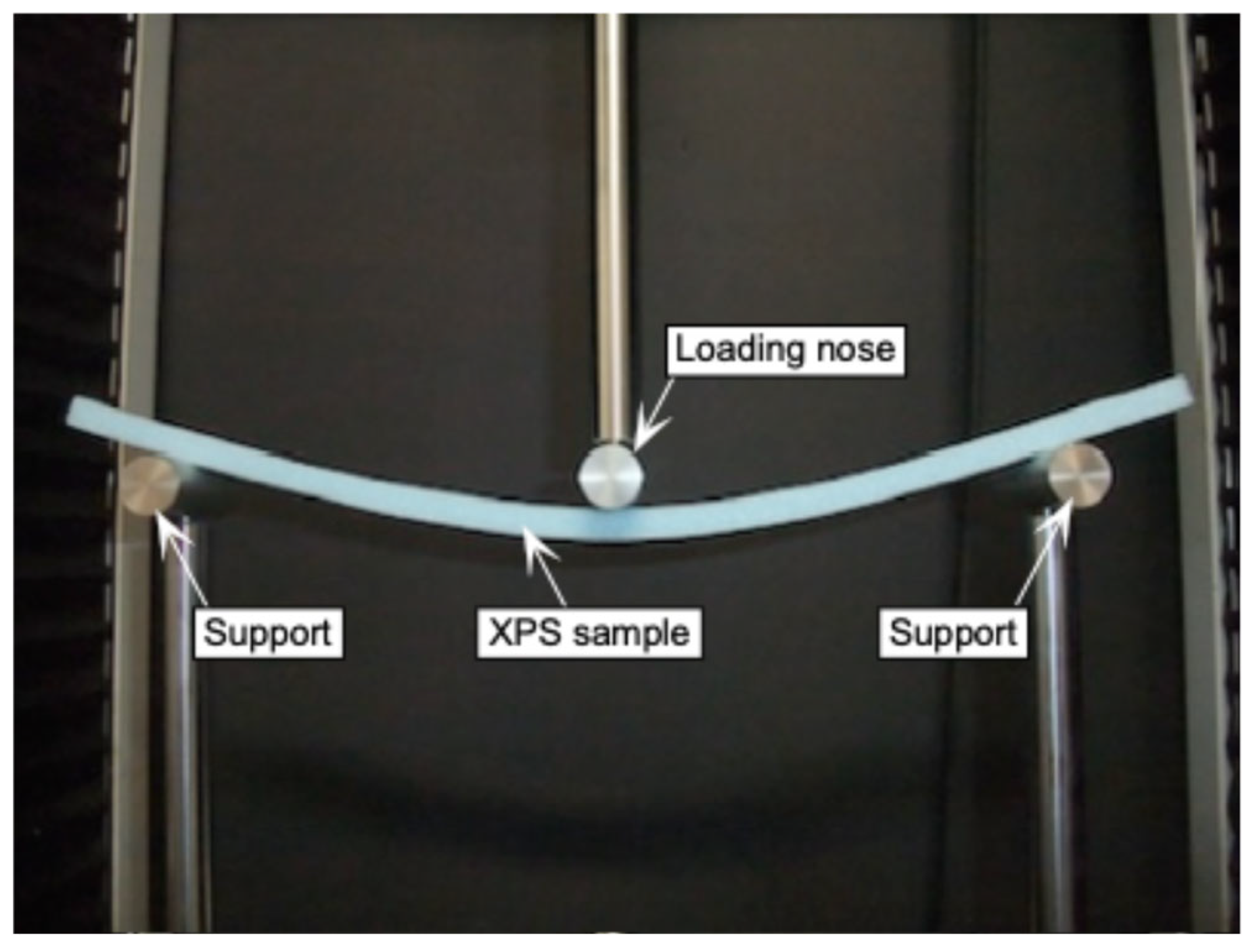

3.4. Three-Point Bending Tests

4. Results and Discussion

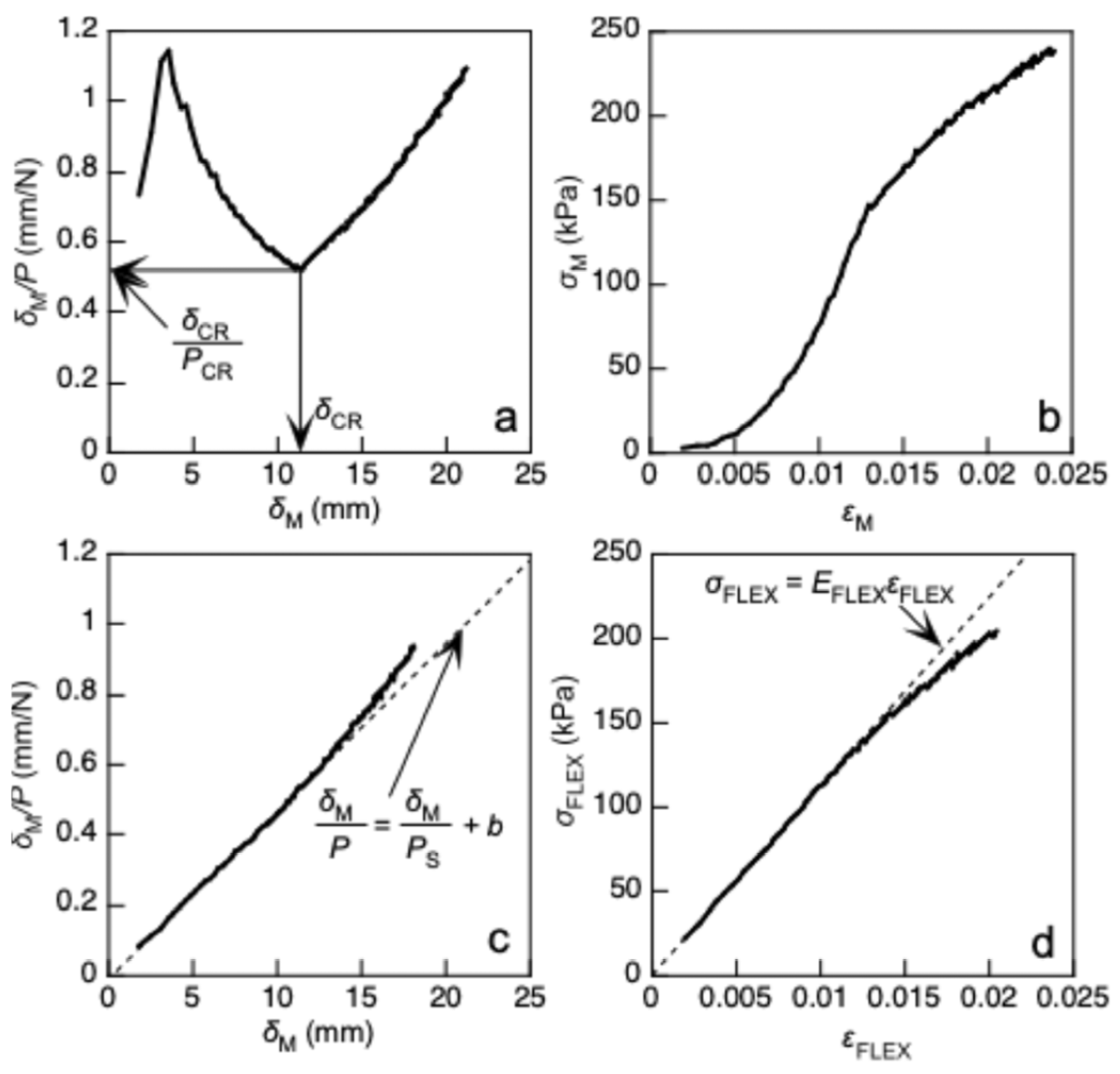

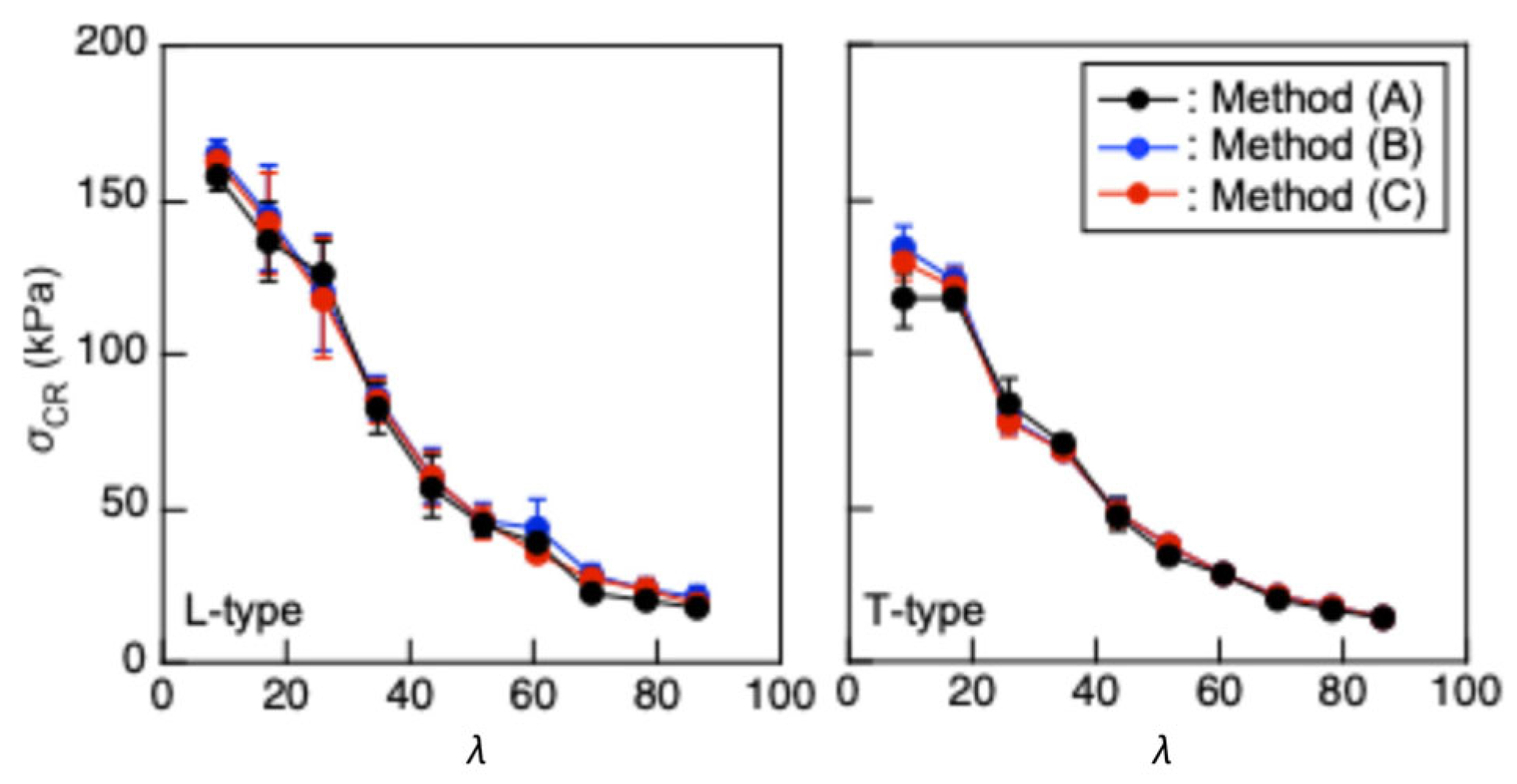

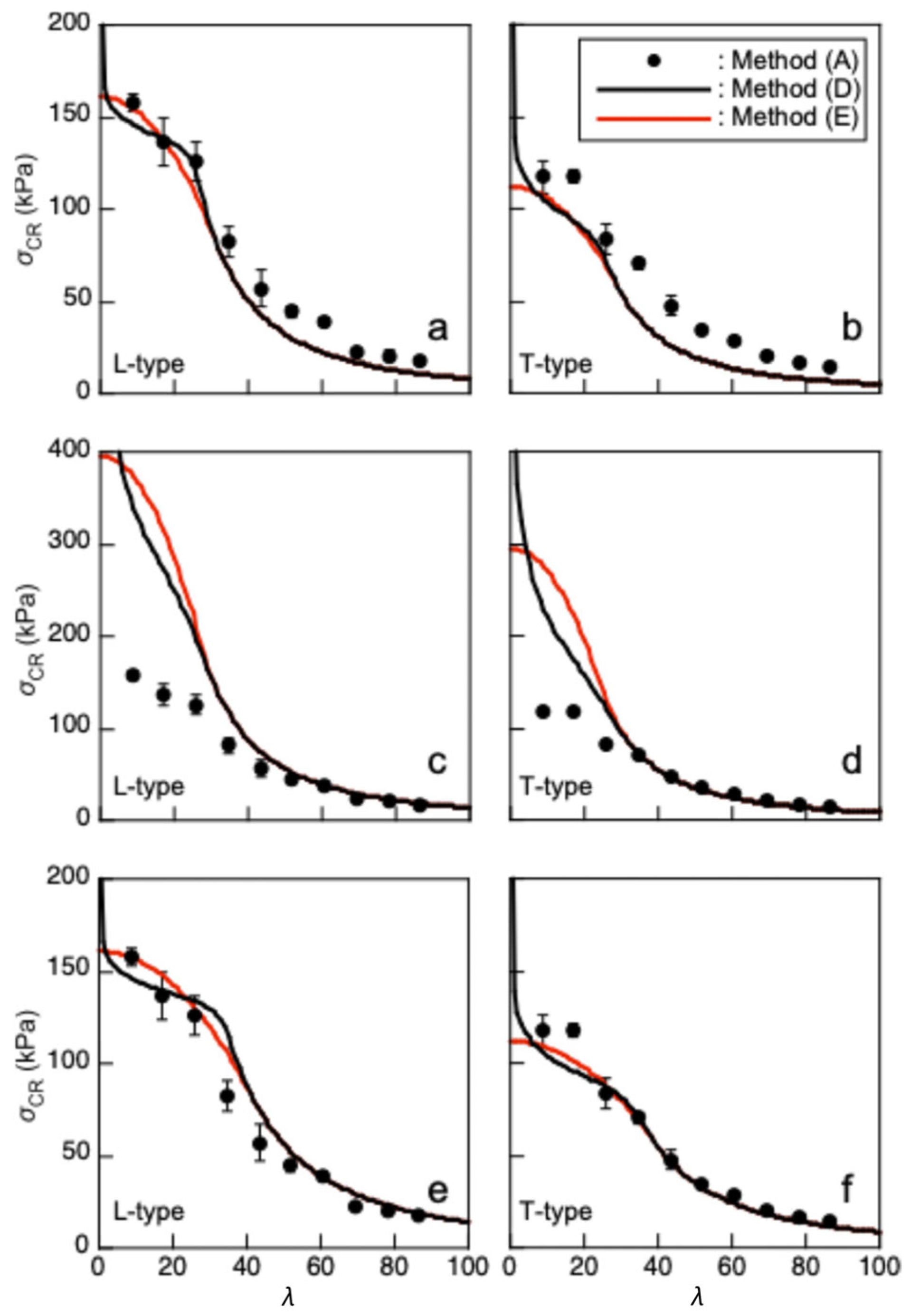

4.1. Buckling Stress Obtained from Actual Buckling Test

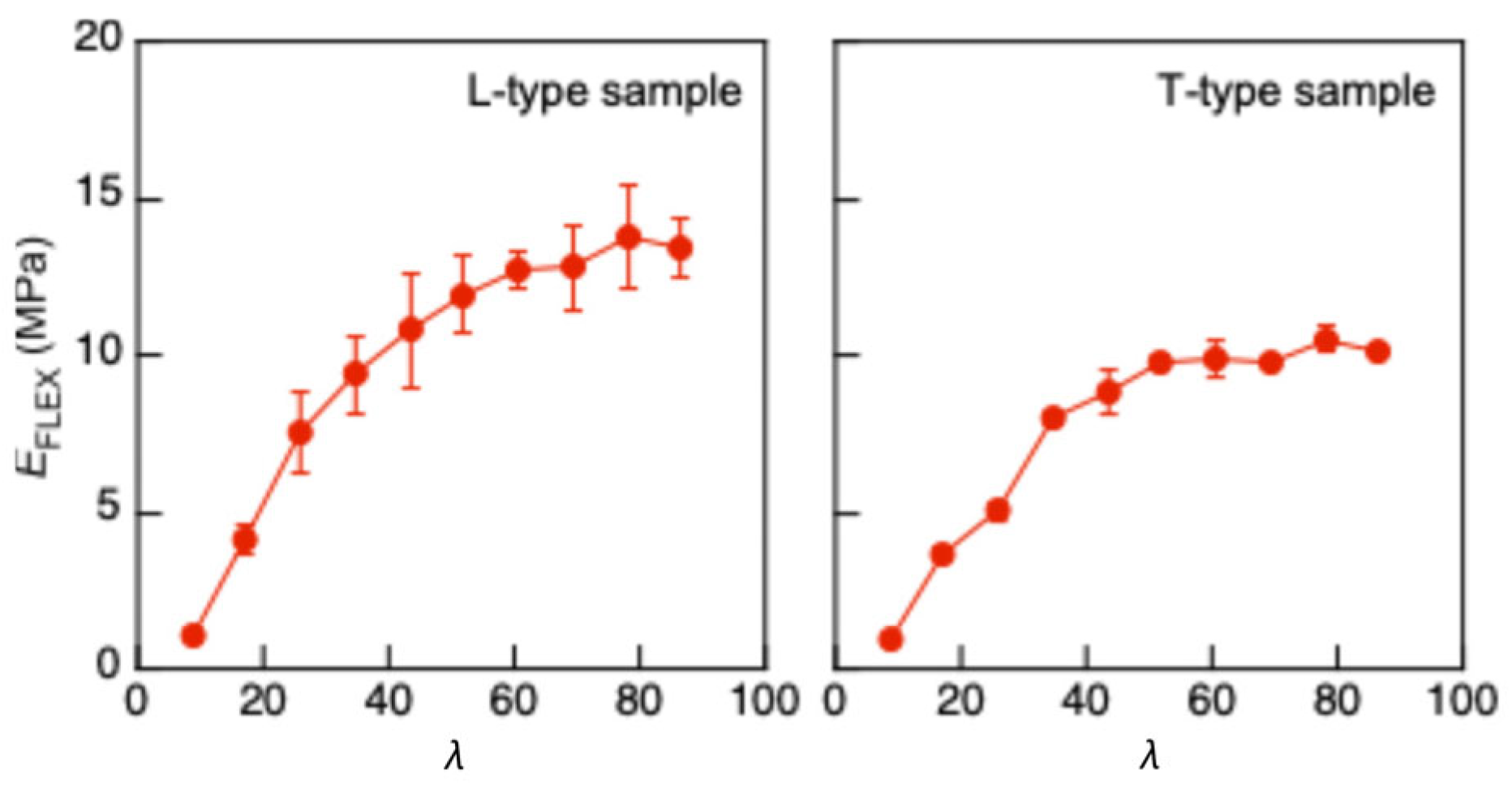

4.2. Buckling Stress Predicted Using the Compression and Three-Point Bending Test Data

- (a)

- The FCOMP value corresponding to each sample was determined using the maximum value of σCOMP.

- (b)

- The experimentally obtained σCOMP–εCOMP relationship was regressed into Equation (9), and the values of ECOMP, nCOMP, and KCOMP were calculated for each sample.

- (c)

- The average value of FCOMP, defined as , was calculated using five samples. Then the εCOMP value corresponding to σCOMP = (N = 1, 2, …, 100) was calculated by substituting ECOMP, nCOMP, and KCOMP into Equation (9).

- (d)

- The εCOMP values at NFCOMP/100 obtained using five samples were averaged, and the averaged value was defined as .

- (e)

- The relationship was regressed again into Equation (9). The properties obtained from this procedure, defined as , , and , are listed in Table 2, as well as .

- (f)

- The abovementioned process was also performed using the data obtained from the three-point tests. The values of , , and are also listed in Table 2.

| (MPa) | (kPa) | (×10−3) | ||

| L-type | 8.19 | 161 | 34.8 | 9.87 |

| T-type | 4.93 | 112 | 16.4 | 18.1 |

| (MPa) | (kPa) | (×10−3) | ||

| L-type | 14.3 | 396 | 8.58 | 43.2 |

| T-type | 8.84 | 295 | 6.93 | 7.97 |

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Buckling stress could be effectively determined via the actual buckling test using our proposed method, Southwell’s method, and the modified Euler method across a wide range of slenderness ratios, whether buckling occurred in the elastic or inelastic region.

- (2)

- Among the three methods mentioned in (1), our proposed method was superior to the other two, owing to its simplicity.

- (3)

- It was difficult to predict the buckling stress using the properties obtained from the compression tests alone or those obtained from the bending tests alone.

- (4)

- The buckling stress could be appropriately determined when using the properties obtained from both the compression and three-point bending tests together.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| b | width of the sample used for the three-point bending test |

| B | width of the sample used for the buckling test |

| ECOMP | Young’s modulus obtained from the compression test |

| EFLEX | Young’s modulus obtained from the buckling test under post-buckling condition |

| ETAN | tangent modulus |

| ETPB | Young’s modulus obtained from the three-point bending test |

| h | depth of the sample used for the three-point bending test |

| H | depth of the sample used for the buckling test |

| l | length between the span in the three-point bending test |

| L | length of the sample used for the buckling test |

| nCOMP and KCOMP | parameters obtained by regressing the σCOMP–εcCOMP relationship into the Ramberg–Osgood type function |

| nTPB and KTPB | parameters obtained by regressing the σTPB–εTPB relationship into Ramberg–Osgood type function |

| P | load applied to the sample |

| xCR | critical displacement for buckling |

| xEFF | effective displacement for lateral deflection |

| xLLD | loading-line displacement |

| εCOMP | strain in the loading direction obtained from the compression test |

| εTPB | strain at the surface of the midspan obtained from the three-point bending test |

| λ | slenderness ratio |

| σCOMP | compressive stress in the loading direction obtained from the compression test |

| σCR | critical stress for buckling |

| σTPB | bending stress at the surface of the midspan obtained from the three-point bending test |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| COV | coefficient of variation |

| L, T, and Z | length, width, and thickness directions of the XPS panel, respectively |

| XPS | extruded polystyrene |

References

- Wheatley, S.J.; Mallett, A.J. Foam plastic insulation for high temperature and shock protection. J. Cell. Plast. 1970, 6, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yang, L.; Kucharek, M. Investigation of the effect of thermal insulation materials on packaging performance. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2020, 33, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, H.; Saito, I.; Onuki, A.; Takeuchi, M.; Tsuchiya, T. Presumption of the source of indoor air pollution. Amounts of styrene and butanol generation from construction materials. Ann. Rep. Tokyo Metr. Res. Lab. Public Health 2000, 51, 219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi, R.; Matsunobu, K.; Matsumura, T. Development of continuous vapor generation for calibration styrene with permeation tube method. Indoor Environ. 2009, 52, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Matsumoto, T.; Iwamae, A.; Wakana, S.; Mihara, N. Effect of the temperature-humidity condition in the room and under the floor by heat insulation tatami and flooring. In Proceedings of the Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, Kobe, Japan, 13 September 2014; Architectural Institute of Japan (Environmental Engineering II): Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Ishida, M.; Sasaki, H.; Horie, K. Compressive strength of insulation materials for heatstorage tank. In Proceedings of the Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, Kobe, Japan, 13 September 2014; Architectural Institute of Japan (Environmental Engineering II): Tokyo, Japan, 2011. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Gnip, I.; Keršulis, V.; Vaitkus, S.; Vėjelis, S. Assessment of strength under compression of expanded polystyrene (EPS) slabs. Mater Sci. 2004, 10, 326–329. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hu, Y.; Nakao, T.; Nakai, T.; Gu, J.; Wang, F. Dynamic properties of three types of wood-based composites. J. Wood Sci. 2005, 51, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Nakao, T.; Nakai, T.; Gu, J.; Wang, F. Vibrational properties of wood plastic plywood. J. Wood Sci. 2005, 51, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Kawai, S. Thermal insulation properties of wood-based sandwich panel for use as structural insulated walls and floors. J. Wood Sci. 2005, 52, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, S.; Kochkin, V.; Drumheller, S.C.; Barta, L. Moisture performance of energy-efficient and conventional wood-frame wall assemblies in a mixed-humid climate. Buildings 2015, 5, 759–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; You, Y.-C. Composite behavior of a novel insulated concrete sandwich wall panel reinforced with GFRP shear grids: Effect of insulation types. Materials 2015, 8, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervloet, J.; Kapsalis, P.; Verbruggen, S.; Kadi, M.E.; De Munck, M.; Tysmans, T. Characterization of the bond between textile reinforced cement and extruded polystyrene by shear test. Proceedings 2018, 2, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selver, E.; Kaya, G. Flexural properties of sandwich composite laminates reinforced with glass and carbon Z-pins. J. Compos. Mater. 2019, 53, 1347–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhang, B.; Cremaschi, L. Review of moisture behavior and thermal performance of polystyrene insulation in building applications. Build. Environ. 2017, 123, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; Agarwal, S.; Mukhopadhyay, P. Plastics in buildings and construction. In Applied Plastics Engineering Handbook, 3rd ed.; Kutz, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 683–703. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Dome House. About Dome House. 2025. Available online: www.i-domehouse.com/about_dome_house/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- EPSTEC China EPS Machine. EPS Styrofoam Prefab Dome House. 2025. Available online: www.epstec.com/product/eps-styrofoam-prefab-dome-house/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Doroudiani, S.; Omidian, H. Environmental, health and safety concerns of decorative mouldings made of expanded polystyrene in buildings. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurauchi, T.; Negi, K. Energy absorption of foamed rigid polyurethane under compressive deformation. J. Soc. Mater. Sci. Jpn. 1984, 33, 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T.; Nogami, R.; Teragishi, Y.; Takada, T. Relationship between stress and strain in polyethylene foam. A consideration of compressive properties based on a simulation model. J. Soc. Mater. Sci. Jpn. 1992, 41, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Avalle, M.; Belingardi, G.; Montanini, R. Characterization of polymeric structural foams under compressive impact loading by means of energy-absorption diagram. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2001, 11, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholampour, S.; Hajirayat, K.; Erfanian, A.; Zali, A.R.; Shakouri, E. Investigating the role of helmet layers in reducing the stress applied during head injury using FEM. Int. Clin. Neurosci. J. 2017, 4, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kardomateas, G.A.; Simitses, G.J. Comparative studies on the buckling of isotropic, orthotropic, and sandwich columns. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2004, 11, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Deng, Z.C.; Lu, T.J. Analytical modeling and finite element simulation of the plastic collapse of sandwich beams with pin-reinforced foam cores. Int. J. Solid Struct. 2008, 45, 5127–5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eyvazian, A.; Taghizadeh, S.A.; Hamouda, A.M.; Tarlochan, F.; Moeinifard, M.; Gobbi, M. Buckling and crushing behavior of foam-core hybrid composite sandwich columns under quasi-static edgewise compression. J. Sandwich Struct. Mater. 2021, 23, 2643–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völlmecke, C.; Todt, M.; Stylianos, Y. Buckling and postbuckling of architecture materials: A review of methods for lattice structures and metal foams. Compos. Adv. Mater. 2021, 30, 26349833211003904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, S.; Kraynik, A.M.; Gaitanaros, S. Microscopic and macroscopic instabilities in elastometric foams. Mech. Mater. 2022, 164, 104124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ruan, D.; Zhang, A.; Liang, Y.; Tan, P.J.; Chen, P. Deformation and failure of additively manufactured Voronoi foams under dynamic compressive loadings. Eng. Struct. 2023, 284, 115954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Schmauder, S. Multiscale modeling of shape memory polymers foams nanocomposites. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 232, 112658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakarmi, S.; Patterson, B.M.; Bezek, L.B.; Trinh, C.K.; Lee, K.-S.; Leiding, J.A.; Daphalapurkar, N.P. Mesoscale simulations and validation experiments of polymer foam compaction-volume density effects. Mater. Lett. 2025, 382, 137864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 20504:2006; Fine Ceramics (Advanced Ceramics, Advanced Technical Ceramics)—Test Method for Compressive Behaviour of Continuous Fibre-Reinforced Composites at Room Temperatures. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- JIS R 1673:2007; Test Method for Compressive Behavior of Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Ceramic Matrix Composites at Room Temperatures. Japan Standards Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2007.

- Timoshenko, S.P.; Gere, J.M. Chapter 3: Inelastic Buckling of Bars. In Theory of Elastic Stability, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Singapore, 1963; pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Fairker, J.E. A Study of the Strength of Short and Intermediate Wood Columns by Experimental and Analytical Methods; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, WI, USA, 1964; pp. 330–335.

- Kúdela, J.; Slaninka, R. Stability of wood columns loaded in buckling Part 1. Centric buckling. Wood Res. 2002, 47, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Koczan, G.; Kozakiewicz, P. Comparative analysis of compression and buckling of European beech wood (Fagus sylvatica L.). Ann. Wars. Univ. Life Sci. For. Wood Technol. 2016, 95, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kotšmíd, S.; Beňo, P. Determination of buckling loads for wooden beams using the elastic models. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2019, 89, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambe, W.; Takahashi, S.; Ito, T.; Aoki, K. An experimental study on compression resistant performance of thick plywood as an axial member. J. Struct. Constr. Eng. AIJ 2013, 684, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, M.; Tao, D.; Li, M. Experimental buckling performance of scrimber composite columns under axial compression. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 86, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, H.; Maruta, M. Critical load for buckling of solid wood elements with a high slenderness ratio determined based on elastica theory. Holzforschung 2021, 76, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, H.; Yoshinobu, M.; Maruta, M. Buckling test of flat cardboard and examination of critical load for fuckling. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 2022, 68, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, H.; Yoshinobu, M.; Maruta, M. Effects of testing methods and sample configuration on the flexural properties of extruded polystyrene. Polymers 2024, 16, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, H.; Maruta, M. Measurement of the shear properties of extruded polystyrene foam by in-plane shear and asymmetric four-point bending tests. Polymers 2020, 12, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramberg, W.; Osgood, W.R. Description of Stress-Strain Curves by Three Parameters; NACA TN-902; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1943.

- Timoshenko, S.P.; Gere, J.M. Chapter 4: Experiments and Design Formulas. In Theory of Elastic Stability, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Singapore, 1963; pp. 195–197. [Google Scholar]

- JIS B 7721:2018; Tension/Compression Testing Machines−Calibration and Verification of the Force-Measuring System. Japan Standards Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2007.

- Free Statistical Software: EZR (Easy R) Version 1.68. Available online: https://www.jichi.ac.jp/saitama-sct/SaitamaHP.files/statmedEN.html (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Yoshihara, H.; Ohta, M. Analysis of the buckling stress of an intermediate wooden column by the tangent modulus theory. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 1995, 41, 367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara, H.; Ohta, M.; Kubojima, Y. Prediction of the buckling stress of intermediate wooden columns using the secant modulus. J. Wood Sci. 1998, 44, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Martin, C.D. Evaluation of tensile Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of a bi-modular rock from the displacement measurements in a Brazilian test. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2018, 51, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.J.; Ashby, M.F. Cellular Solids Structure & Properties, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; pp. 175–234. [Google Scholar]

- Šimonová, H.; Kucharczyková, B.; Keršner, Z. Mechanical fracture parameters of extruded polystyrene. Key Eng. Mater. 2018, 776, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, H.; Maruta, M. Mode I J-integral of extruded polystyrene measured by the four-point single-edge notched bending test. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2019, 222, 106716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, Y.; Yoshihara, H. Characterization of Mode I fracture mechanics properties of extruded polystyrene via double cantilever beam test using a side-grooved sample. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 329, 111578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| L (mm) | 50 | 100 | 150 | 200 | 250 | 300 | 350 | 400 | 450 | 500 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mm/min) | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 6.9 |

| Sample Type | Equation (13) | Equation (19) | Equation (22) |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-type | 31.7 | 26.7 | 41.8 |

| T-type | 29.5 | 24.3 | 39.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoshihara, H.; Yoshimura, K.; Yoshinobu, M.; Maruta, M. Buckling Analysis of Extruded Polystyrene Columns with Various Slenderness Ratios. Polymers 2025, 17, 2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222997

Yoshihara H, Yoshimura K, Yoshinobu M, Maruta M. Buckling Analysis of Extruded Polystyrene Columns with Various Slenderness Ratios. Polymers. 2025; 17(22):2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222997

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoshihara, Hiroshi, Koki Yoshimura, Masahiro Yoshinobu, and Makoto Maruta. 2025. "Buckling Analysis of Extruded Polystyrene Columns with Various Slenderness Ratios" Polymers 17, no. 22: 2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222997

APA StyleYoshihara, H., Yoshimura, K., Yoshinobu, M., & Maruta, M. (2025). Buckling Analysis of Extruded Polystyrene Columns with Various Slenderness Ratios. Polymers, 17(22), 2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222997