A Multi-Analytical Study of Nanolignin/Methylcellulose-Coated Groundwood and Cotton Linter Model Papers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Lignin Purification

2.3. Preparation of Nanolignin Solutions

2.4. Sample Preparation

2.5. Accelerated Ageing

2.6. pH Measurements

2.7. Colourimetry

2.8. Attenuated Total Reflectance/Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR/FTIR)

2.9. Polarised Light Microscopy (PLM)

2.10. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.11. Controlled Relative Humidity—Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA-RH)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Polarised Light Microscopy (PLM)

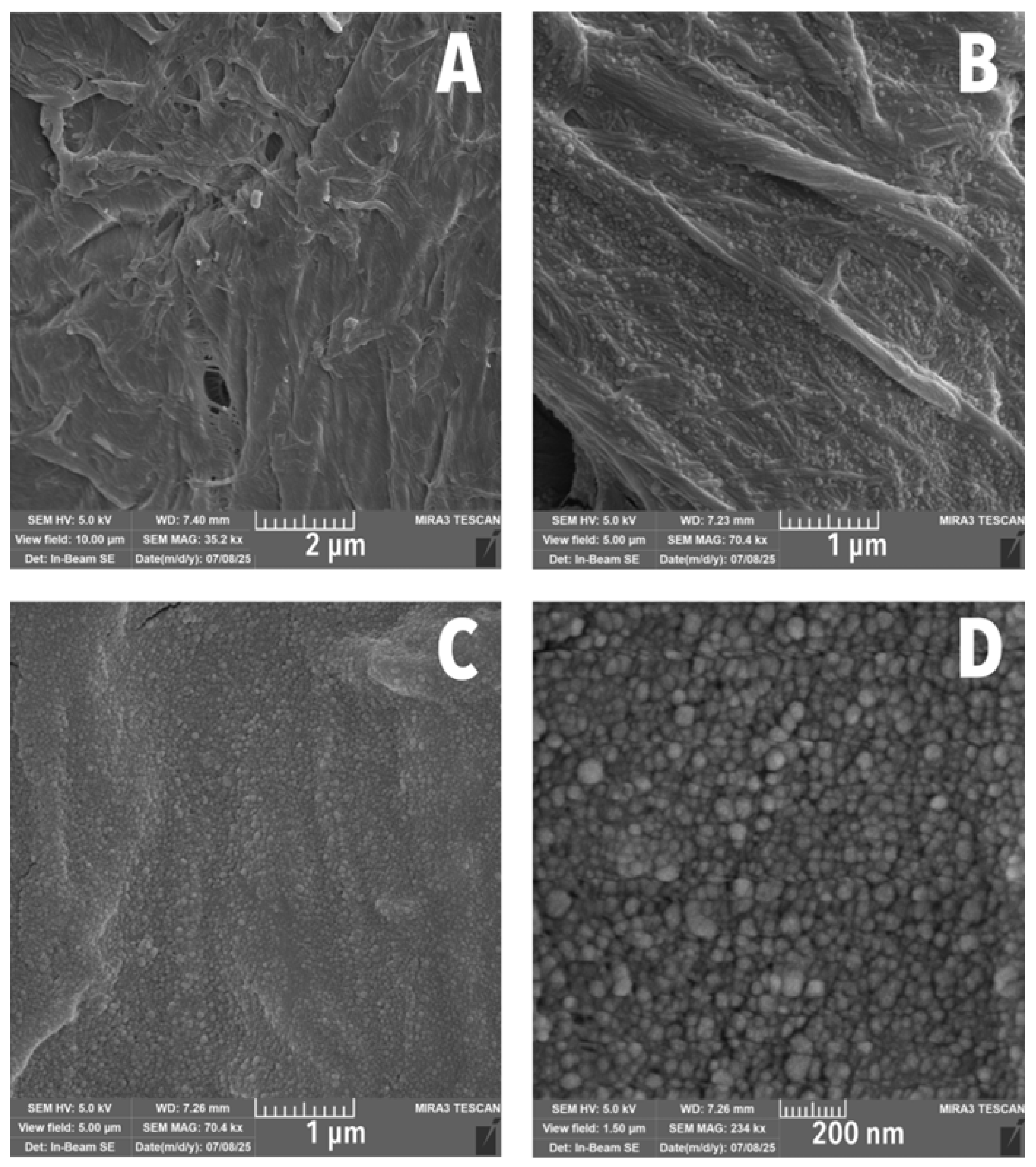

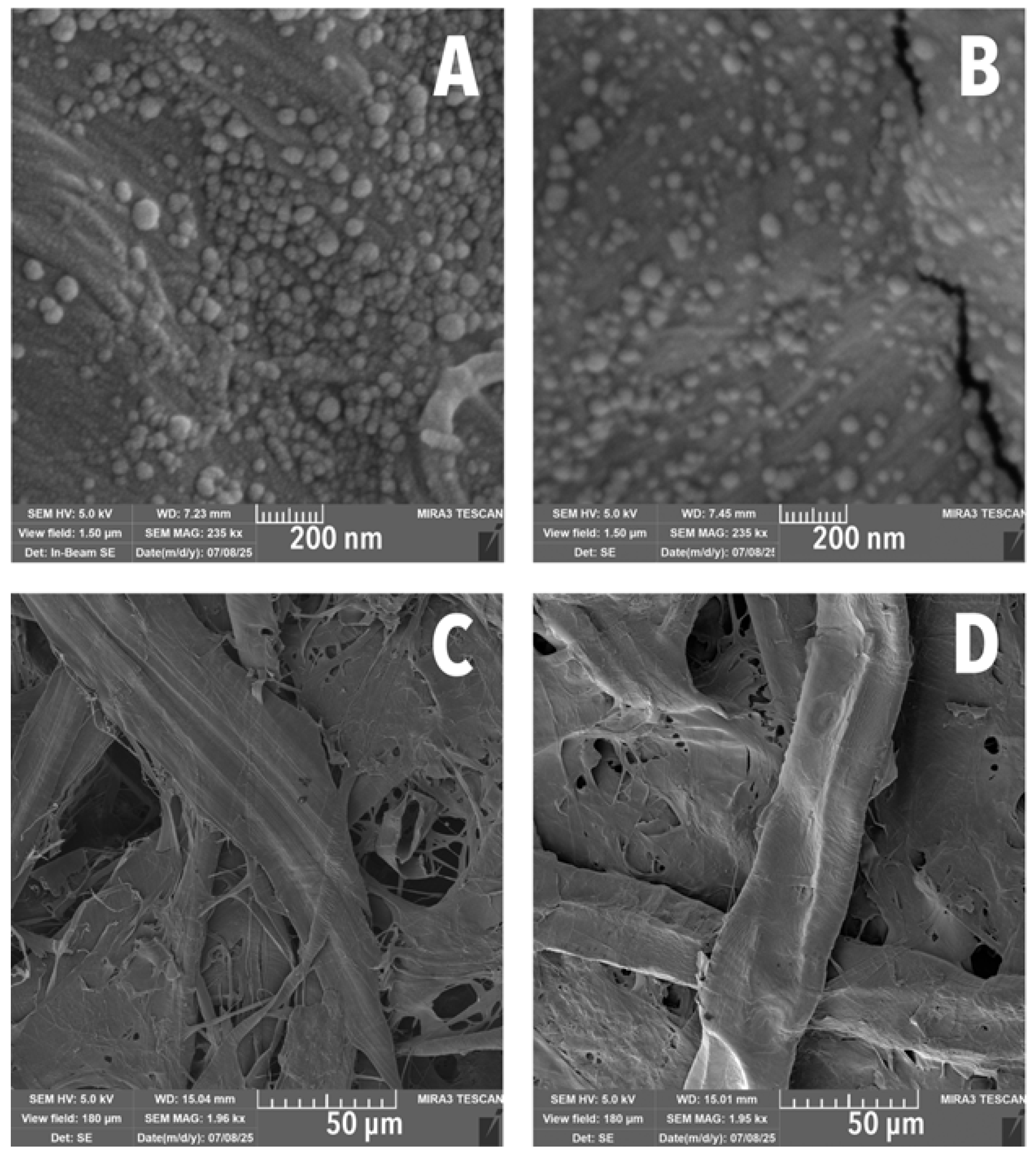

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3.3. Colourimetry

3.4. Acidity—pH

3.5. Fourier Transform InfraRed Spectroscopy

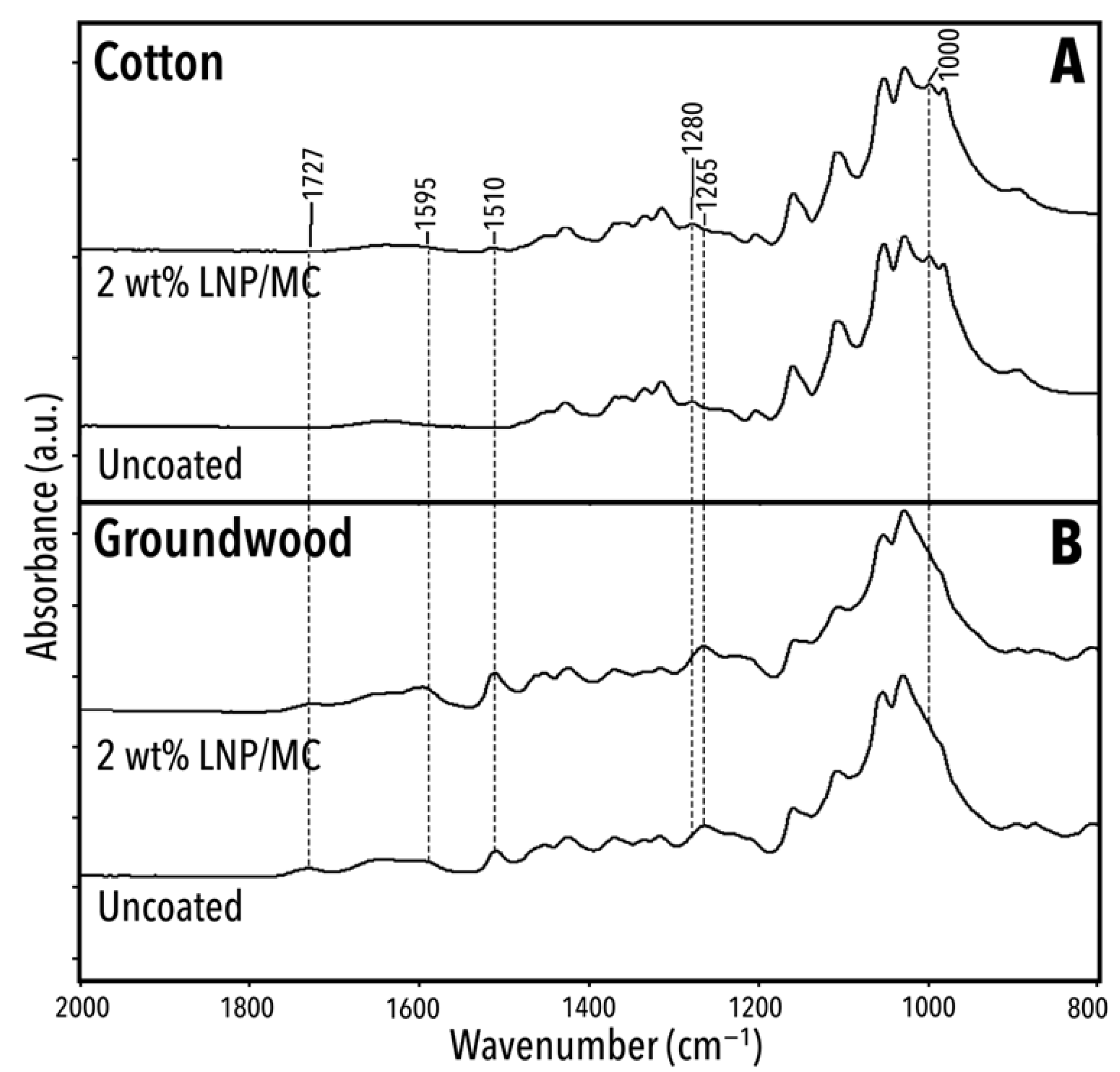

3.5.1. ATR/FTIR Overview

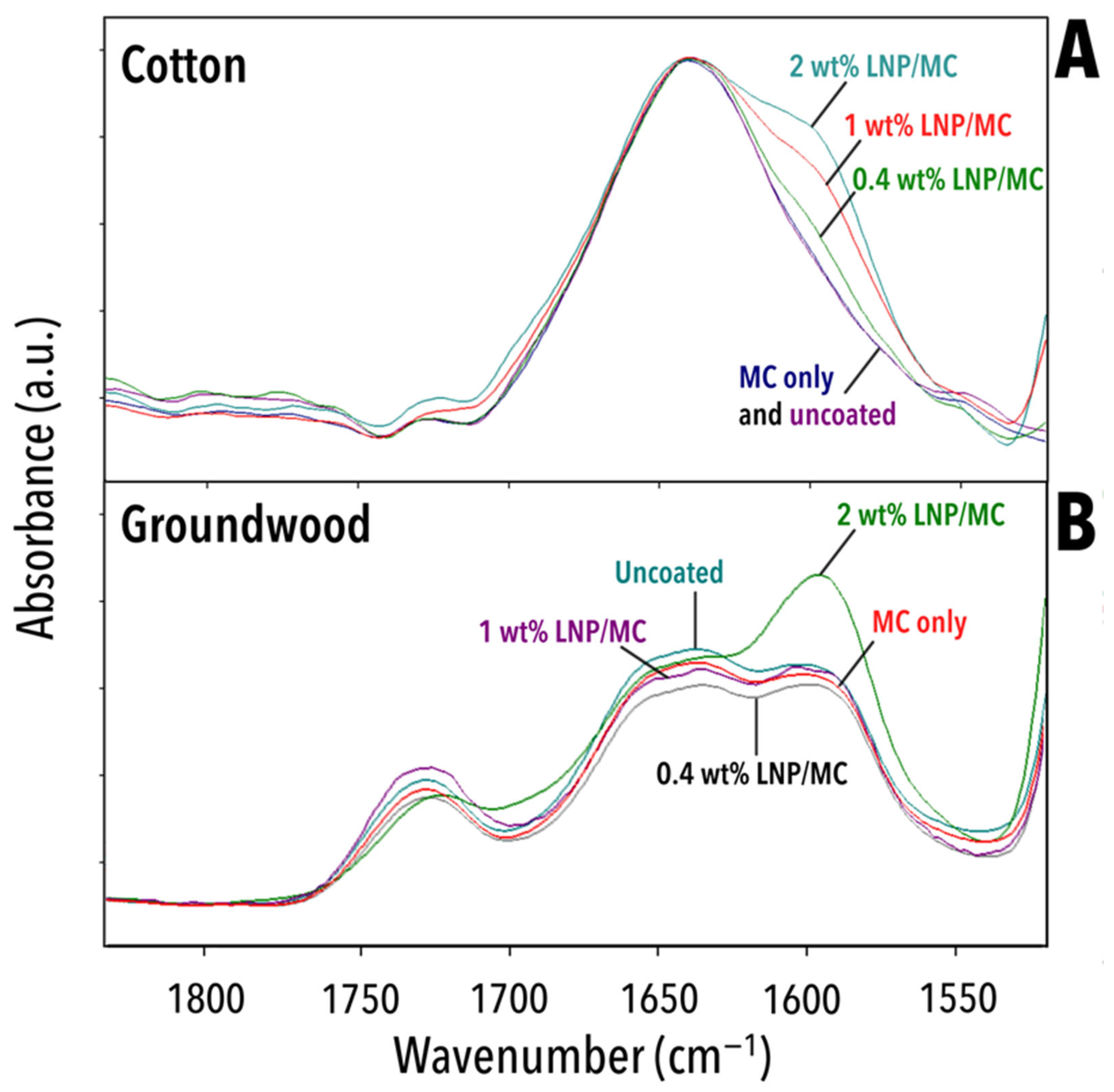

3.5.2. Substrate-Specific FTIR Signatures and the Impact of LNP/MC Coatings

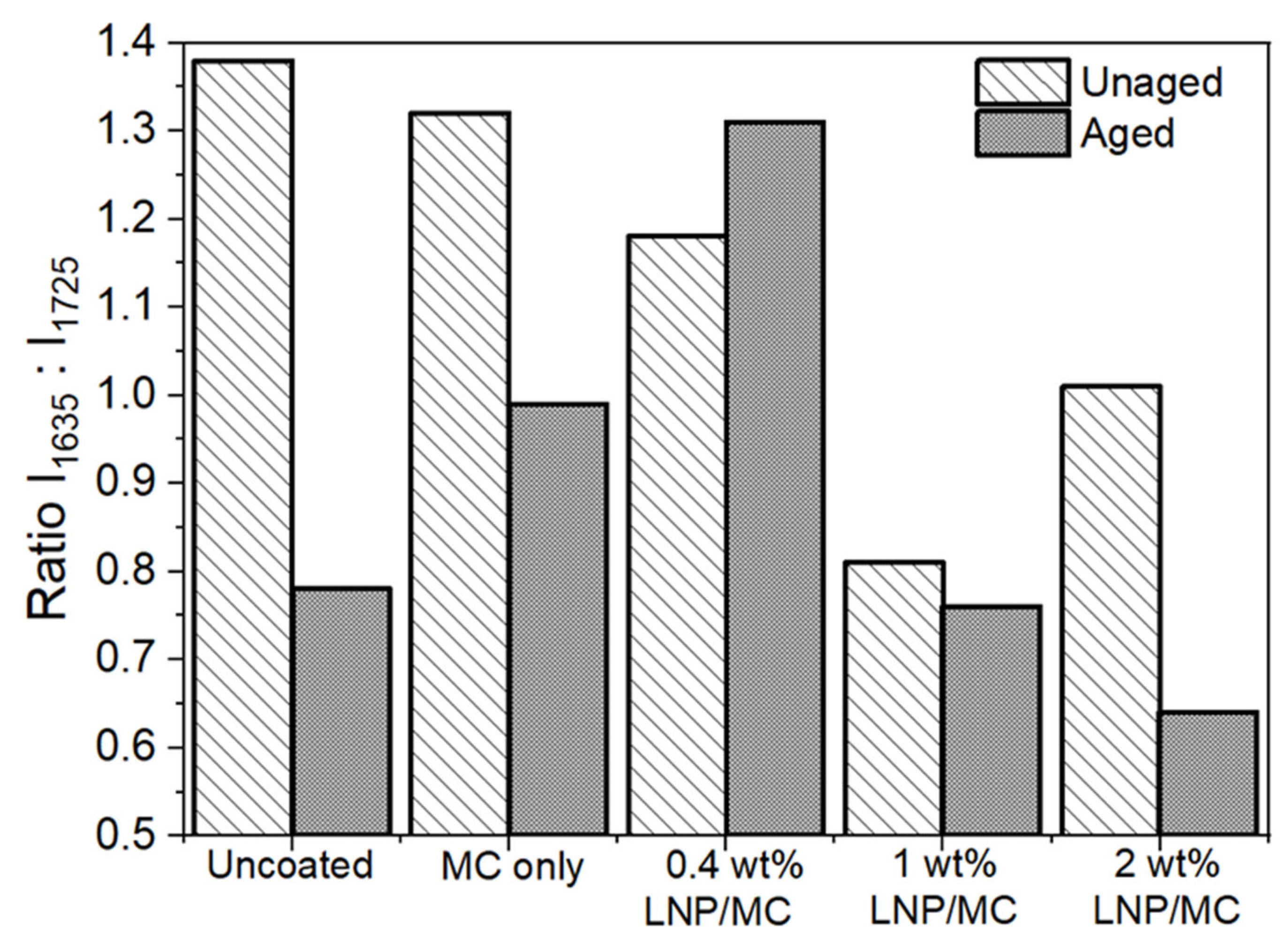

3.5.3. The Effect of the LNP/MC Coatings on Oxidation of the Substrates

3.6. DMA-RH

3.6.1. Unaged Controls

3.6.2. Unaged MC Only-Coated Samples

3.6.3. Unaged LNP/MC-Treated Samples

3.6.4. Aged Controls

3.6.5. Aged MC Only-Coated Samples

3.6.6. Aged LNP/MC-Treated Samples

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Svensson, I.-L.; Alwarsdotter, Y. A papermaker’s view of the standard of permanent paper, ISO 9706. In A Reader in Preservation and Conservation; Manning, R.W., Kremp, V., Eds.; K. G. Saur: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bégin, P.; Deschatelets, S.; Grattan, D.; Gurnagul, N.; Iraci, J.; Kaminska, E.; Woods, D.; Zou, X. The impact of lignin on paper permanence. A comprehensive study of the ageing behaviour of handsheets and commercial paper samples. Restaurator 1998, 19, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małachowska, E.; Pawcenis, D.; Dańczak, J.; Paczkowska, J.; Przybysz, K. Paper ageing: The effect of paper chemical composition on hydrolysis and oxidation. Polymers 2020, 13, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Xue, Y.; Lui, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; Ji, X. Research on the structure and properties of traditional handmade bamboo paper during the aging process. Molecules 2024, 29, 5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scribner, B.W. Report of bureau of standards research on preservation of records. Libr. Q. 1931, 1, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbe, M.A. Acidic and alkaline sizings for printing, writing, and drawing papers. Book Pap. Group Annu. 2004, 23, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonsky, M.; Šima, J.; Lelovsky, M. Considerations on factors influencing the degradation of cellulose in alum-rosin sized paper. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 245, 116534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuncira, J.; Manoel, G.F.; Ribas Batalha, L.A.; Gonçalves, L.M.; Mendoza-Martinez, C.; Cardoso, M.; Vakkilainen, E.K. Comparison of thermal, rheological properties of Finnish Pinus and Brazilian Eucalyptus sp. black liquors and their impact on recovery units. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Chen, L.; Hu, P.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, D.; Lu, X.; Mi, B. Comparison of properties, adsorption performance and mechanisms to Cd(II) on lignin-derived biochars under different pyrolysis temperatures by microwave heating. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 25, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulos, D.D.S.; Crestini, C.; Dahlstand, C.; Furusjö, E.; Gioia, C.; Jedvert, K.; Henriksson, G.; Hulteberg, C.; Lawoko, M.; Pierrou, C.; et al. Kraft lignin: A valuable, sustainable resource, opportunities and challenges. ChemSusChem 2023, 16, e202300492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Owczarek, J.S.; Fortunati, E.; Kozanecki, M.; Mazzaglia, A.; Balestra, G.M.; Kenny, J.M.; Torre, L.; Puglia, D. Antioxidant and antibacterial lignin nanoparticles in polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan films for active packaging. Ind. Crops Prods. 2016, 94, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Fortunati, E.; Dominici, F.; Giovanale, G.; Mazzaglia, A.; Balestra, G.M.; Kenny, J.M.; Puglia, D. Synergic effect of cellulose and lignin nanostructures in PLA based systems for food antibacterial packaging. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 79, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, U.P.; Foo, M.L.; Chew, I.M.L. Synthesis and characterization of lignin nanoparticles isolated from oil palm empty fruit bunch and application in biocomposites. Sust. Chem. Clim. Action 2023, 2, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, N.N.; Osman, L.S.; Garba, Z.N.; Hamidon, T.S.; Brosse, N.; Ziegler-Devin, I.; Chrusiel, L.; Hussin, M.H. Isolation, properties, and recent advancements of lignin nanoparticles as green antioxidants. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 212, 113059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, H.; Rezende, C.A. Pure, stable and highly antioxidant lignin nanoparticles from elephant grass. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 145, 112105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Gu, X.; Shi, Y. A review on lignin antioxidants: Their sources, isolations, antioxidant activities and various applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 210, 716–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelin, M.; Liebentritt, S.; Vicente, A.A.; Teixeira, J.A. Lignin from an integrated process consisting of liquid hot water and ethanol organosolv: Physicochemical and antioxidant properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 120 Pt A, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, Y.; Lee, Y.; Oh, J.; Jung, Y.; Koh, W.-G.; Chung, J.J. Reactive oxygen species suppressive kraft lignin-gelatin antioxidant hydrogels for chronic wound repair. Macromol. Biosci. 2022, 22, 2200234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, F.M.C.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Gonçalves, C.; Azinheiro, S.; Garrido-Maestu, A.; Vicente, A.A.; Pastrana, L.M.; Teixeira, J.A.; Michelin, M. Green synthesis of lignin nano- and micro-particles: Physicochemical characterization, bioactive properties and cytotoxicity assessment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 163, 1798–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajer, N.; Cestari, C.; Argyropoulos, D.S.; Crestini, C. From lignin self assembly to nanoparticles nucleation and growth: A critical perspective. NPJ Mater. Sustain. 2024, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yearla, S.R.; Padmasree, K. Preparation and characterisation of lignin nanoparticles: Evaluation of their potential as antioxidants and UV protectants. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2016, 11, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornari, A.; Rossi, M.; Rocco, D.; Mattiello, L. A review of applications of nanocellulose to preserve and protect cultural heritage wood, paintings, and historical papers. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.; Salmieri, S.; Dussault, D.; Uribe-Calderon, J.; Kamal, M.R.; Safrany, A.; Lacroix, M. Production and properties of nanocellulose-reinforced methylcellulose-based biodegradable films. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 7878–7885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, X.; Liu, C.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Deng, C.; Wei, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, H. Functionalized lignin nanoparticles prepared by high shear homogenization for all green and barrier-enhanced paper packaging. Resour. Chem. Mater. 2024, 3, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, G.; Giorgi, R.; Toccafondi, N.; Katzur, V.; Baglioni, P. Hydroxide nanoparticles for deacidification and concomitant inhibition of iron-gall ink corrosion of paper. Langmuir 2010, 26, 19084–19090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, R.; Bozzi, C.; Dei, L.G.; Gabbiani, C.; Ninham, B.W.; Baglioni, P. Nanoparticles of Mg(OH)2: Synthesis and application to paper conservation. Langmuir 2005, 21, 8495–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyfuss-Deseigne, R. Nanocellulose films in art conservation: A new and promising mending material for translucent paper objects. J. Pap. Conserv. 2017, 18, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridarolli, A. Multiscale Approach in the Assessment of Nanocellulose-Based Materials and Consolidants for Cotton Painting Canvases. Ph.D. Thesis, University College London, London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bridarolli, A.; Nualart-Torroja, A.; Chevalier, A.; Odlyha, M.; Bozec, L. Systematic mechanical assessment of consolidants for canvas reinforcement under controlled environment. Herit. Sci. 2020, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasmani, J.E. Effects of ozone and nanocellulose treatments on the strength and optical properties of paper made from chemical mechanical pulp. BioResources 2016, 11, 7710–7720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorova, A.; Lahti, J.; Schennach, R.; Stelzer, F. Humidity response of kraft papers determined by dynamic mechanical analysis. Thermochim. Acta 2013, 570, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operamolla, A.; Mazzuca, C.; Capodieci, L.; Di Benedetto, F.; Severini, L.; Titubante, M.; Martinelli, A.; Castelvetro, V.; Micheli, L. Toward a reversible consolidation of paper materials using cellulose nanocrystals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 33972–44982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canham, R.; Murray, A.; Hill, R. Some practical aspects of nanocellulose film: Characterization, expansion and shrinking tests, and techniques to create remoistenable nanocellulose. Restaurator 2023, 44, 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmelch, L.; D’Emilio, E.M.L.; Geiger, T.; Effner, C. Degraded paper: Stabilization and strengthening through nanocellulose application. J. Pap. Conserv. 2024, 25, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baty, J.W.; Maitland, C.L.; Minter, W.; Hubbe, M.A.; Jordan-Mowery, S.K. Deacidification for the conservation and preservation of paper-based works: A review. BioResources 2010, 5, 1955–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, F.; Galotta, G.; Sidoti, G.; Zikeli, F.; Nisi, R.; Petriaggi, B.D.; Romagnoli, M. Cellulose and lignin nano-scale consolidants for waterlogged archaeological wood. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Ke, D.; Wang, C.; Pan, H.; Chen, K.; Zhang, H. Modified lignin nanoparticles as potential conservation materials for waterlogged archaeological wood. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 12351–12363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargos, C.H.M.; Poggi, G.; Chelazzi, D.; Baglioni, P.; Rezende, C.A. Protective coatings based on cellulose nanofibrils, cellulose nanocrystals, and lignin nanoparticles for the conservation of cellulosic artifacts. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 13245–13259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskell, C. The conservation of a scrap screen from Carlyle’s House, London. Pap. Conserv. 2000, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.N.B.; Scopel, E.; Rezende, C.A. From black liquor to tinted sunscreens: Washing out kraft lignin unpleasant odor and improving its properties by lignin nanoparticle preparation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 218, 118910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiz, S.; Schlemmer, W.; Hobisch, M.A.; Hobisch, J.; Keinberger, M. Preparation and characterization of a water-soluble kraft lignin. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2020, 4, 2000052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, J.; Wang, B.; Feng, X.; Mao, Z.; Sui, X. Acetone/Water cosolvent approach to lignin nanoparticles with controllable size and their applications for Pickering emulsions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 5470–5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grappa, R.; Venezia, V.; Silvestri, B.; Costantini, A.; Luciani, G. Synthesis of lignin nanoparticles: Top-down and bottom-up approaches. Med. Sci. Forum 2024, 25, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAPPI T 544 cm-19; Aging of Paper and Board with Moist Heat. Technical Association of the Paper and Pulp Industry: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2019.

- Greenspan, L. Humidity fixed points of binary saturated aqueous solutions. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand.—A Phys. Chem. 1976, 81A, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAPPI T 509 om-22; Hydrogen Ion Concentration (pH) of Paper Extracts (Cold Extraction Method). Technical Association of the Paper and Pulp Industry: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2022.

- CIE No. 15; Technical Report: Colorimetry. International Commission on Illumination: Vienna, Austria, 2004.

- ISO 7724/1; Paints and Varnishes—Colorimetry—Part 1: Principles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1984.

- ASTM E 1164; Standard Practice for Obtaining Spectrometric Data for Object-Color Evaluation. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- DIN 5033-7; Colorimetry—Part 7: Measuring Conditions for Object Colours. German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 2014.

- JIS Z 8722; Methods of Colour Measurement—Reflecting and Transmitting Objects. Japanese Standards Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2009.

- Sharma, G. The CIEDE2000 Color-Difference Formula. 2005. Available online: https://hajim.rochester.edu/ece/sites/gsharma/ciede2000/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Aryana, N.; Krismatuti, F.S.H.; Arutanti, O.; Restu, W.K. The preparation of lignin nanoparticles: Comparison between homogenization and ultrasonication treatments following anti-solvent precipitation method. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2902, 080004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuello, C.; Foulon, L.; Chabbert, B.; Aguié-Béghin, V.; Molinari, M. Atomic force microscopy reveals how relative humidity impacts the Young’s modulus of lignocellulosic polymers and their adhesion with cellulose nanocrystals at the nanoscale. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 147, 1064–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervos, S.; Moropoulou, A. Methodology and criteria for the evaluation of paper conservation interventions: A literature review. Restaurator 2006, 27, 219–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, K.A.; Babaeipour, S.; Forssell, S.; Nousiainen, P.; Meinander, K.; Oinas, P.; Österberg, M. Transparent lignin nanoparticles for superhydrophilic antifogging coatings and photonic films. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 145965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.S.; Herrmann, J.K.; Chipman, A.; Davis, A.R.; Khan, Y.; Loew, S.; Danzis, K.M.; Ohanyan, T.; Varga, L.; Witty, A.; et al. Heat- and solvent-set repair tissues. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2020, 61, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauptmann, M.; Pleschberger, H.; Mai, C.; Follrich, J.; Hansmann, C. The potential of color measurements with the CIEDE2000 equation in wood science. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2012, 70, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Xiao, K.; Pointer, M.; Melgosa, M.; Bressler, Y. Optimizing parametric factors in CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color-difference formulas for 3D-printed spherical objects. Nanomaterials 2022, 15, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Xia, A.; Liao, Q.; Zhu, X.; Huang, Y.; Fu, Q. Laccase pretreatment of wheat straw: Effects of the physicochemical characteristics and the kinetics of enzymatic hydrolysis. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, E.A.; Mutlu, Ü. TGA-FTIR analysis of biomass samples based on the thermal decomposition behavior of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin. Energies 2023, 16, 3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesionowski, T.; Klapiszewski, L.; Milczarek, G. Kraft lignin and silica as precursors of advanced composite materials and electroactive blends. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, T.; Dharela, R.; Chauhan, G.S. Novel method for extraction of lignin cellulose and hemicellulose from Pinus roxburghii needles. Am. J. Innov. Sci. Eng. 2023, 2, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.-M.; Vasile, C.; Popescu, M.-C.; Popa, V.I.; Munteanu, B.S. Analytical methods for lignin characterization. II. Spectroscopic studies. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2006, 40, 597–622. [Google Scholar]

- Nasatto, P.L.; Pignon, F.; Silveira, J.L.M.; Duarte, M.E.R.; Noseda, M.D.; Rinaudo, M. Methylcellulose, a cellulose derivative with original physical properties and extended applications. Polymers 2015, 7, 777–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroy, Y.; Versino, F.; Garcia, M.A.; Rivero, S. Ecological packaging: Reuse and recycling of rosehip waste to obtain biobased multilayer starch-based material and PLA for food trays. Foods 2025, 14, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamasco, S.; Zikeli, F.; Vinciguerra, V.; Sobolev, A.P.; Scarnati, L.; Tofani, G.; Mugnozza, G.S.; Romagnoli, M. Extraction and characterization of acidolysis lignin from Turkey oak (Quercus cerris L.) and Eucalypt (Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh.) wood from population stands in Italy. Polymers 2023, 15, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiridon, I.; Teacă, C.-A.; Bodîrlău, R. Structural changes evidenced by FTIR spectroscopy in cellulosic materials after pre-treatment with ionic liquid and enzymatic hydrolysis. BioResources 2011, 6, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisperguer, J.; Perez, P.; Urizar, S. Structure and thermal properties of lignins: Characterization by infrared spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2009, 54, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogulet, A.; Blanchet, P.; Landry, V. Wood degradation under UV irradiation: A lignin characterization. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2016, 158, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladini, G.; Venuti, V.; Crupi, V.; Majolino, D.; Fiorati, A.; Punta, C. 2D Correlation Spectroscopy (2DCoS) Analysis of Temperature-Dependent FTIR-ATR Spectra in Branched Polyethyleneimine/TEMPO-Oxidized Cellulose Nano-Fiber Xerogels. Polymers 2021, 13, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulleman, S.H.D.; van Hazendonk, J.M.; van Dam, J.E.G. Determination of crystallinity in native cellulose from higher plants with diffuse reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Res. 1994, 261, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazi, M.E.; Narayanan, G.; Aghabozorgi, F.; Farajidizaji, B.; Aghaei, A.; Kamyabi, M.A.; Navarathna, C.M.; Mlsna, T.E. Structure, chemistry and physicochemistry of lignin for material functionalization. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łojewska, J.; Miśkowiec, P.; Łojewski, T.; Proniewicz, L.M. Cellulose oxidative and hydrolytic degradation: In situ FTIR approach. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2005, 88, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahankari, S.S.; Kar, K.K. Hysteresis measurements and dynamic mechanical characterization of functionally graded natural rubber-carbon black composites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2010, 50, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnaillie, L.M.; Tomasula, P.M. Application of humidity-controlled dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA-RH) to moisture-sensitive edible casein films for use in food packaging. Polymers 2015, 7, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfthan, J. The effect of humidity cycle amplitude on accelerated tensile creep of paper. Mech. Time-Depend. Mater. 2004, 8, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanic, J.S.; Salmén, L. Molecular origin of mechano-sorptive creep in cellulosic fibres. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 230, 115615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navi, P.; Pittet, V.; Plummer, C.J.G. Transient moisture effects on wood creep. Wood Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellman, F.A.; Benselfelt, T.; Larsson, P.T.; Wågberg, L. Hornification of cellulose-rich materials—A kinetically trapped state. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 318, 121132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.; Sjöstrand, B. Hornification of softwood and hardwood pulps correlating with a decrease in accessible surfaces. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 26164–26171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourbaba, R.; Abdulkhani, A.; Rashidi, A.; Ashori, A. Lignin nanoparticles as a highly efficient adsorbent for the removal of methylene blue from aqueous media. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, R.L.; Wilt, M. Evaluation of Cellulose for Conservation; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 63–64. [Google Scholar]

| Mean Diameter (nm) | Total LNPs Measured (%) |

|---|---|

| 3.9–12.9 | 11.5 |

| 12.9–21.8 | 21.9 |

| 21.8–30.8 | 22.1 |

| 30.8–39.8 | 17.3 |

| 39.8–48.8 | 13.2 |

| 48.8–57.8 | 7.37 |

| 57.8–66.8 | 2.80 |

| 66.8–75.7 | 2.04 |

| 75.7–84.7 | 1.27 |

| 84.7–93.7 | 0.51 |

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Interpretation | Origin | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3332–3336 | ν(O-H) | Cellulose, lignin | [60,61] |

| 2899–2900, 2941–2944 | νas(C-H) | Lignin, MC, cellulose, hemicellulose | [62,63,64,65,66] |

| 1722–1727 | ν(C=O) | Lignin, hemicellulose | [66,67] |

| 1636–1640 | ν(C=O/C-O) (conjugated), bonding from absorbed water | Lignin, water | [63,66,68] |

| 1592–1606 | ν(C=C), δ(C-H) | Lignin | [64] |

| 1509–1514 | ν(C-C) and/or ν(C=C) | Lignin | [60,61,62,69,70] |

| 1452–1461 | δ(C-H) | Cellulose | [61] |

| 1424–1428 | ν(C-C), δ(C-H) | Lignin, cellulose | [61,62] |

| 1361–1371 | δs(C-H), ρ(CH2) | Lignin, cellulose | [71] |

| 1335 | δ(C-H) | Cellulose | [61] |

| 1315–1317 | ρ(CH2) | Cellulose | [71] |

| 1280 | δ(C-H) | Cellulose (crystalline) | [72] |

| 1265 | ν(C-O) | Lignin | [61,62,64,69,70] |

| 1205–1207 | ν(C-O), ν(C-OH) or δ(C-CH) | Lignin, cellulose | [62,63,69,71] |

| 1157–1161 | ν(C-O), C-C ring breathing | Cellulose | [61,71] |

| 1107–1109 | ν(C-O), C-C ring breathing, νas(C-O-C) | Lignin, cellulose | [60,70,71] |

| 1000, 1030–1031, 1054–1055 | ν(C-O), ν(C-O-C), ν(C-OH), in-plane ρ(–CH–) | Cellulose, hemicellulose | [60,61,70,71] |

| 984–986, 895–897 | ν(C-O-C) | Cellulose | [71] |

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Interpretation | Extant in Which Samples | Origin | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1722–1727 | ν(C=O) | Uncoated groundwood 2 wt% LNP/MC groundwood | Lignin, hemicellulose | [66,67] |

| 1592–1606 | ν(C=C), δ(C-H) | Uncoated groundwood 2 wt% LNP/MC cotton 2 wt% LNP/MC groundwood | Lignin | [64] |

| 1509–1514 | ν(C-C) and/or ν(C=C) | Uncoated groundwood 2 wt% LNP/MC cotton 2 wt% LNP/MC groundwood | Lignin | [60,61,62,69,70] |

| 1280 | δ(C-H) | Uncoated cotton 2 wt% LNP/MC cotton | (Crystalline) cellulose | [72] |

| 1265 | ν(C-O) | Uncoated groundwood 2 wt% LNP/MC groundwood | Lignin | [61,62,64,69,70] |

| 1000 | in-plane ρ(–CH–) | Uncoated cotton 2 wt% LNP/MC cotton | Cellulose | [71] |

| Sample | E′20i * (MPa) | E′80 (MPa) | E′20f (MPa) | ΔE′20i-80 (%) | ΔE′20i-20f (%) | d20i (%) | d20f (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cotton, uncoated, unaged | 101 | 82 | 117 | −18.8 | +15.8 | 0.1 | 1.4 |

| Groundwood, uncoated, unaged | 271 | 266 | 334 | −1.9 | +23.3 | 0.2 | 1.2 |

| Cotton, MC only, unaged | 369 | 292 | 383 | −20.9 | +3.8 | 0.1 | 1.6 |

| Groundwood, MC only, unaged | 337 | 332 | 421 | −1.5 | +24.9 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Cotton, 0.4 wt% LNP/MC, unaged | 346 | 259 | 312 | −25.1 | −9.8 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Cotton, 1 wt% LNP/MC, unaged | 401 | 324 | 455 | −19.2 | +13.5 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| Cotton, 2 wt% LNP/MC, unaged | 584 | 450 | 566 | −24.6 | −8.7 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Groundwood, 0.4 wt% LNP/MC, unaged | 445 | 375 | 479 | −15.7 | +7.6 | 0.1 | 1.8 |

| Groundwood, 1 wt% LNP/MC, unaged | 431 | 368 | 447 | −14.6 | +3.7 | 0.1 | 1.4 |

| Groundwood, 2 wt% LNP/MC, unaged | 444 | 391 | 522 | −11.4 | +13.8 | 0.2 | 2.1 |

| Sample | E′20i (MPa) | E′80 (MPa) | E′20f (MPa) | ΔE′20i-80 (%) | ΔE′20i-20f (%) | d20i (%) | d20f (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cotton, uncoated, aged | 106 | 88 | 122 | −17.0 | +15.1 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Groundwood, uncoated, aged | 285 | 318 | 368 | +11.6 | +29.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 |

| Cotton, MC only, aged | 297 | 244 | 317 | −17.9 | +6.7 | 0.1 | 2.6 |

| Groundwood, MC only, aged | 401 | 398 | 436 | −0.8 | +8.7 | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| Cotton, 0.4 wt% LNP, aged | 453 | 350 | 452 | −22.7 | −0.2 | 0.0 | 1.1 |

| Cotton, 1 wt% LNP/MC, aged | 642 | 487 | 634 | −24.1 | −1.3 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Cotton, 2 wt% LNP/MC, aged | 470 | 363 | 456 | −22.8 | −3.0 | 0.1 | 1.1 |

| Groundwood, 0.4 wt% LNP/MC, aged | 242 | 230 | 317 | −5.0 | +31.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Groundwood, 1 wt% LNP/MC, aged | 437 | 424 | 502 | −3.0 | +14.9 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Groundwood, 2 wt% LNP/MC, aged | 200 | 193 | 266 | −3.5 | +33.0 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bloss, M.; Odlyha, M.; Theodorakopoulos, C. A Multi-Analytical Study of Nanolignin/Methylcellulose-Coated Groundwood and Cotton Linter Model Papers. Polymers 2025, 17, 2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212934

Bloss M, Odlyha M, Theodorakopoulos C. A Multi-Analytical Study of Nanolignin/Methylcellulose-Coated Groundwood and Cotton Linter Model Papers. Polymers. 2025; 17(21):2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212934

Chicago/Turabian StyleBloss, Mia, Marianne Odlyha, and Charis Theodorakopoulos. 2025. "A Multi-Analytical Study of Nanolignin/Methylcellulose-Coated Groundwood and Cotton Linter Model Papers" Polymers 17, no. 21: 2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212934

APA StyleBloss, M., Odlyha, M., & Theodorakopoulos, C. (2025). A Multi-Analytical Study of Nanolignin/Methylcellulose-Coated Groundwood and Cotton Linter Model Papers. Polymers, 17(21), 2934. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212934