Antibacterial and Moisture Transferring Properties of Functionally Integrated Knitted Firefighting Fabrics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Characterizations

2.1. Materials

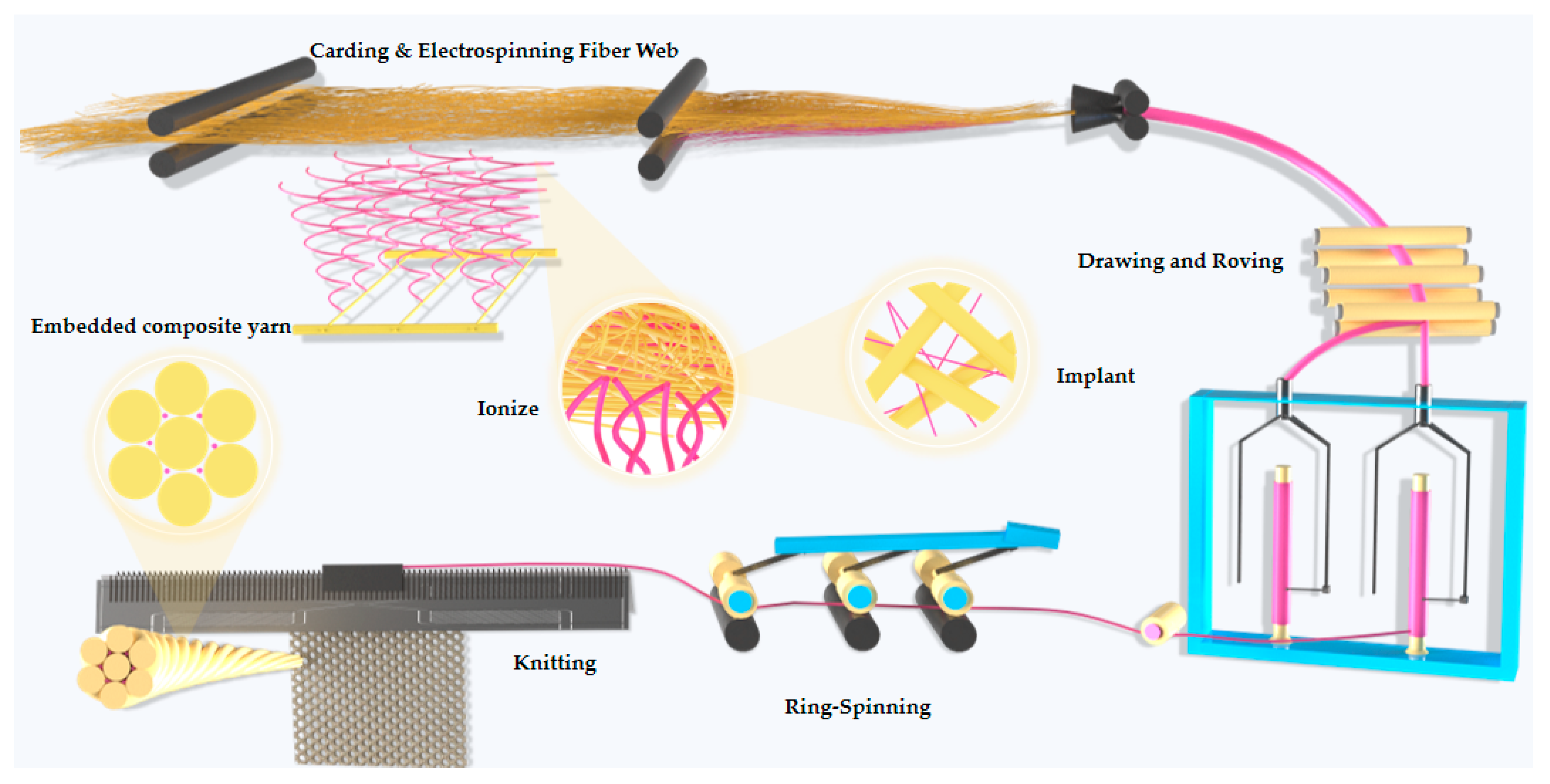

2.2. Preparation of Composite Yarns and Fabrics

2.3. Characterization of Yarn and Fabric Properties

3. Results and Discussion

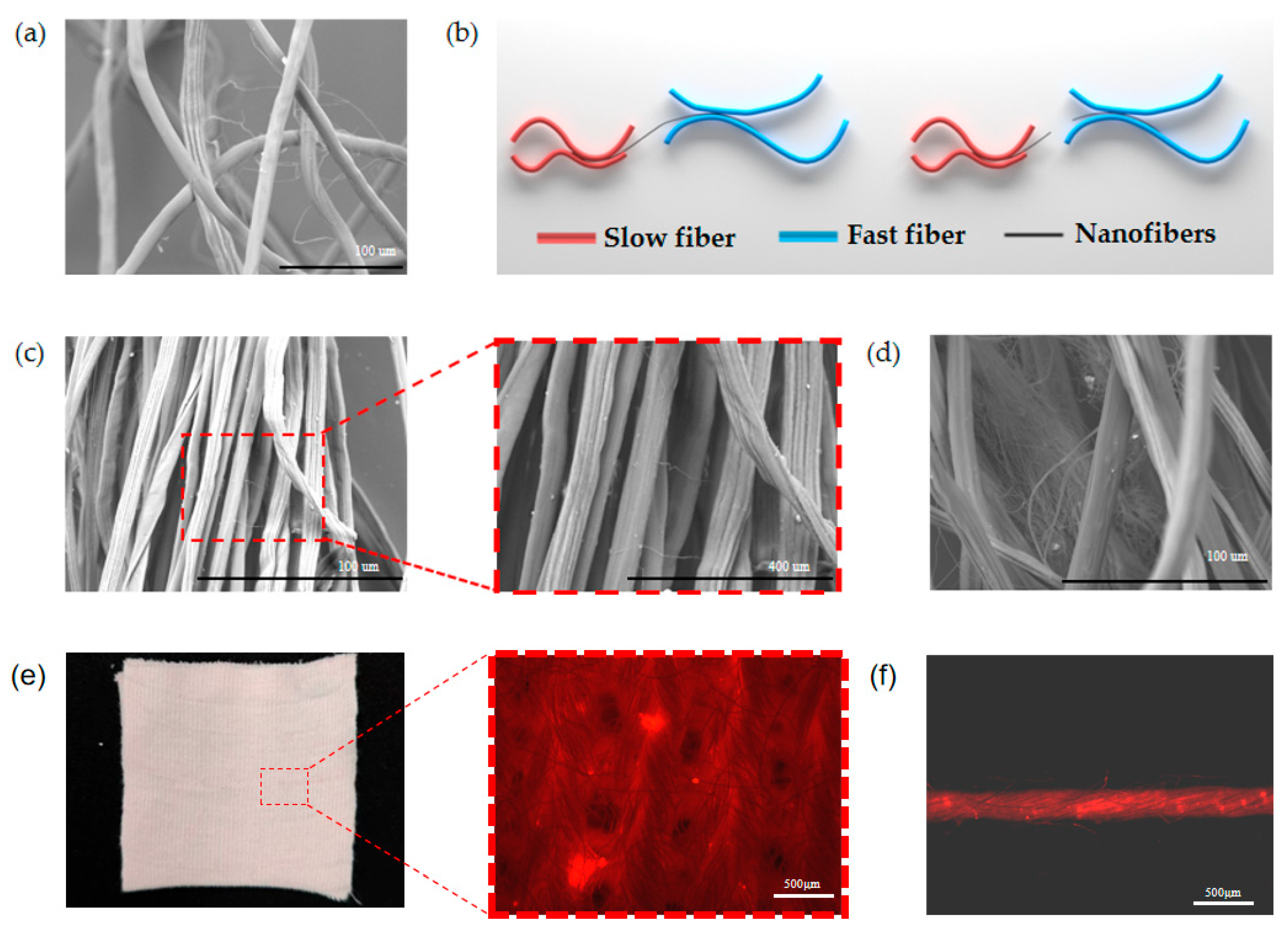

3.1. Basic Yarn and Fabric Performance Tests

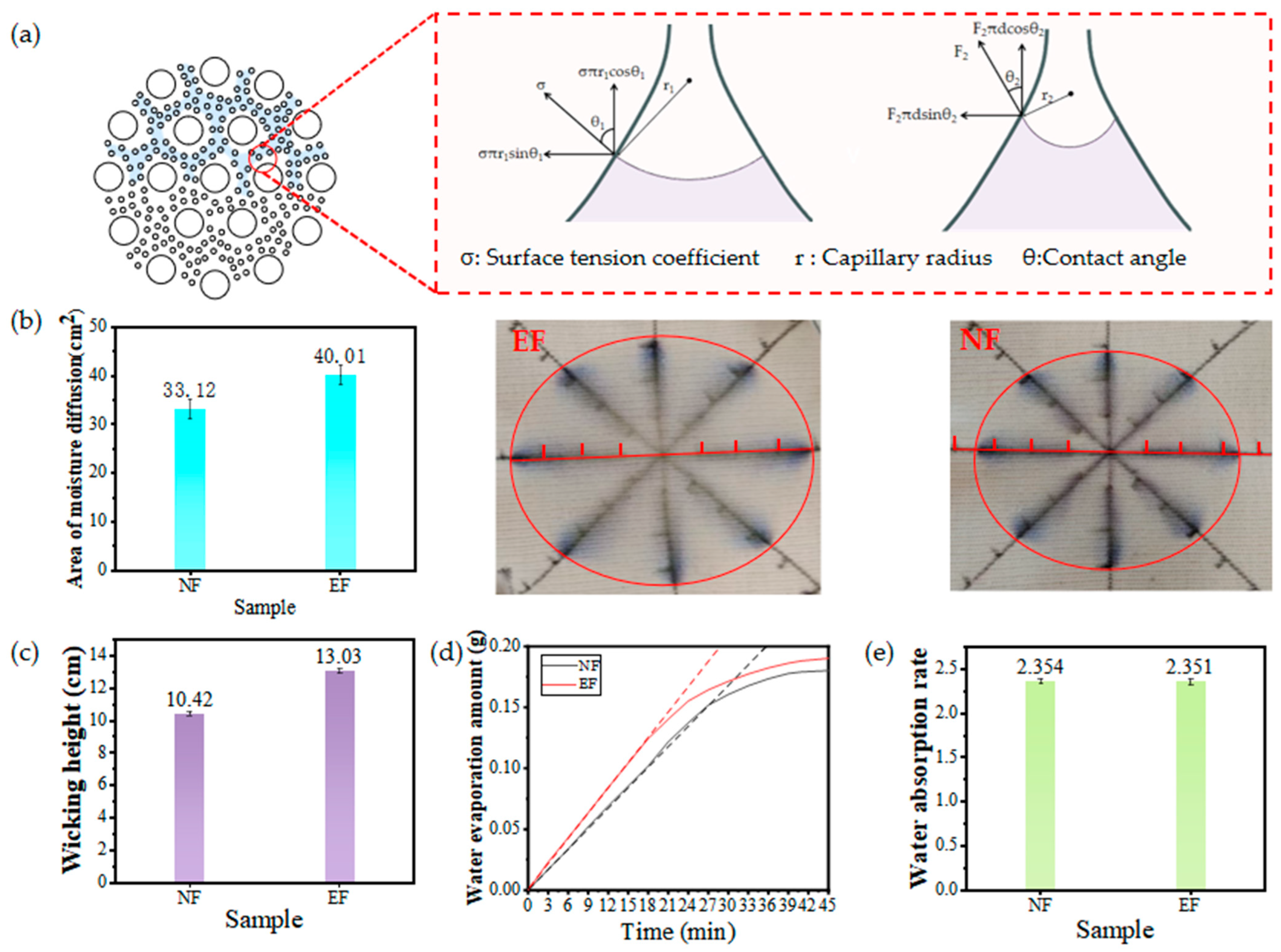

3.2. Fabric Moisture Conductivity

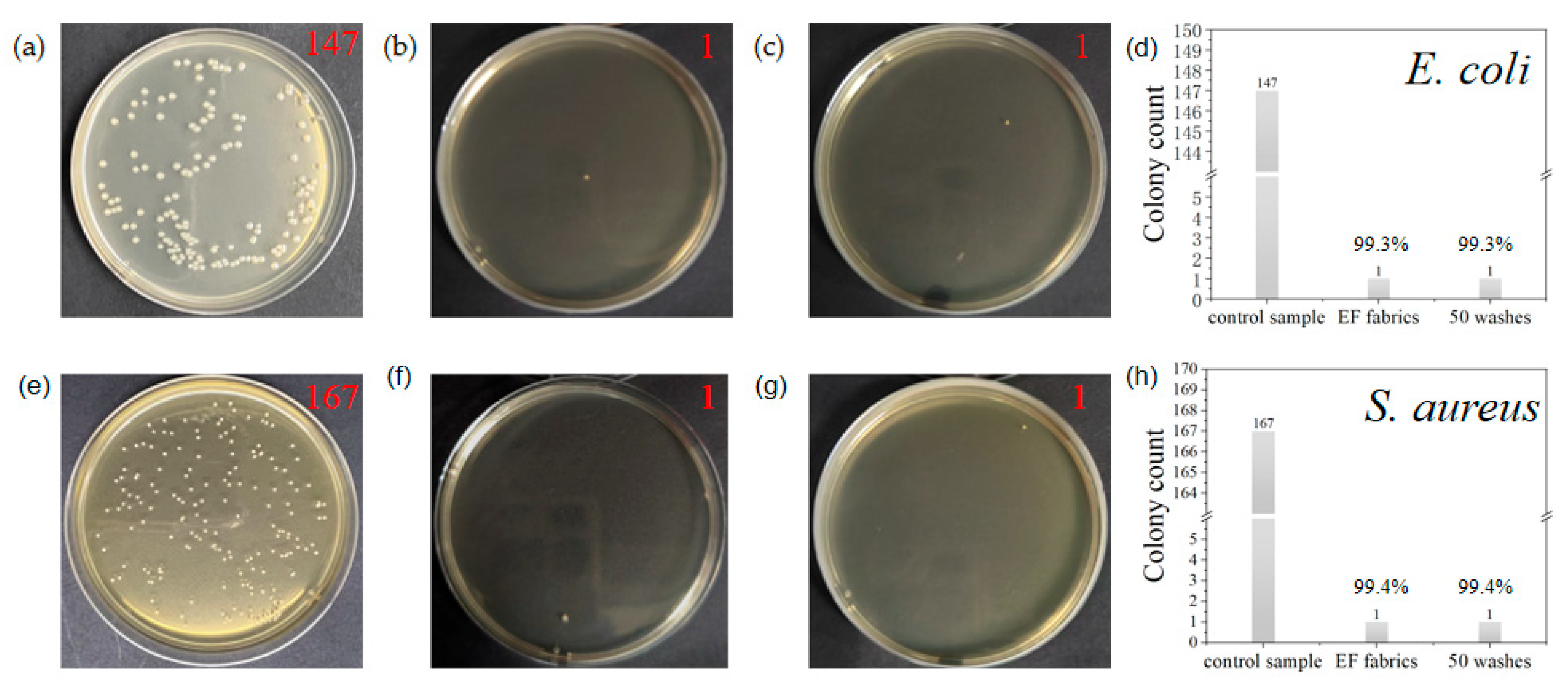

3.3. Fabric Antimicrobial Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liang, X.; Yu, X.; Dong, Z.; Cong, H. Preparation and moisture management performance of double guide bar warp-knitted fabric based on special covering structure. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2021, 16, 1816–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mei, L.; Li, Q. Structure and breathability of silk/cashmere interwoven fabrics based on fractal theory. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2020, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, T.D.; Ribeiro, A.; Bengoechea, C.; Rocha, D.; Alcudia, A.; Begines, B.; Silva, C.; Antunes, J.C.; Felgueiras, H.P. Lyocell/silver knitted fabrics for prospective diabetic foot ulcers treatment: Effect of knitting structure on bacteria and cell viability. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 45, 112389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Tian, Y.; Ning, H.; Hu, N.; Zhang, L.; Liu, F.; Zou, R.; Wang, S.; Wen, J.; Li, L. Cost-efficient breakthrough: Fabricating multifunctional woven hydrogels from water-soluble polyvinyl alcohol yarn. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 157292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi-Kiakhani, M.; Hashemi, E.; Norouzi, M.-M. Production of Antibacterial Wool Fiber Through the Clean Synthesis of Palladium Nanoparticles (PdNPs) by Crocus sativus L. Stamen Extract. Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 3357–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Peng, J. Development and Performance of Negative Ion Functional Blended Yarns and Double-Sided Knitted Fabrics Based on ZnO/TM/PET Fiber. Polymers 2025, 17, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liao, Z.; Huang, M.; Li, K.; Pan, N.; Hou, H.; Ma, W.; Yin, M. N-halamines functionalized PCL nanofibrous yarns with antimicrobial properties for sutures applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 339, 130713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, X.; Lei, Z.; Jia, H.; He, H.; Gong, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, T. Preparation of biodegradable, antibacterial core-spun yarns with braided structures using QAS/PLA micro/nanocomposites. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 20, 015039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, B.; Du, Y.; Bai, M.; Xu, X.; Guan, Y.; Liu, X. Guanidine Derivatives Leverage the Antibacterial Performance of Bio-Based Polyamide PA56 Fibres. Polymers 2024, 16, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgun, M.; Eren, R.; Suvari, F.; Yurdakul, T. Effect of Different Yarn Combinations on Auxetic Properties of Plied Yarns. AUTEX Res. J. 2023, 23, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.T.; Zhang, H.N.; Li, X.X.; Zhao, L.Y.; Guo, L.M.; Qin, X.H. Comprehensive wear-ability evaluation of hollow coffee carbon polyester/cotton blended knitted fabrics. Text. Res. J. 2023, 93, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.T.; Zhao, L.Y.; Gu, X.F. Effect of blending ratio on the hollow coffee carbon polyester/cotton blended yarn. Text. Res. J. 2022, 92, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, C.; He, X.; Teng, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Qin, X. One stone kills two birds: Novel recycled fiber spinning engineering for one-step yarn reinforcement and clean dyeing. Fundam. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.M.; Liu, Y.P.; Qin, X.H. Siro false twist spun yarn structure and the knitted fabric performance. Text. Res. J. 2023, 93, 4096–4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Song, G.H.; Hyeon, J.S.; Wang, Z.; Baughman, R.H.; Kim, S.J. Zinc-air powered carbon nanotube yarn artificial muscle. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 431, 137447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, L.; Xu, W. Sustainable Kapok/cotton/graphene-based textiles for thermal regulation and moisture control with innovative composite. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 228, 120930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.Y.; Shi, X.L.; Wu, X.Y.; Li, C.Z.; Liu, W.D.; Zhang, H.H.; Yu, X.L.; Wang, L.M.; Qin, X.H.; Chen, Z.G. Three-dimensional flexible thermoelectric fabrics for smart wearables. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Li, A.; Zheng, M.; Lou, Z.; Yu, J.; Wang, L.; Qin, X. Shape-Controllable Nanofiber Core-Spun Yarn for Multifunctional Applications. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2024, 6, 1138–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.-Y.; Jiang, Y.-T.; Yuan, Q.; Ma, M.-G. Lightweight, conductive, and hydrophobic wearable textile electronic for personal thermal management and electromagnetic shielding. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 229, 121018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audtarat, S.; Jaruwan, T.; Artit, C.; Dasri, T. Ecofriendly surface improvement of cotton fabric by a plasma-assisted method to enhance silver nanoparticle adhesion for antimicrobial properties. Nanocomposites 2025, 11, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avbelj, M.; Horvat, Z.M.; Hrvoje, P.; Marija, G.; Iskra, J. Development of Antibacterial and Halochromic Textiles by Modification of Emodin from Japanese Knotweed. J. Nat. Fibers 2025, 22, 2445579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Lou, Y.; Meng, L.; Deng, C.; Chu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, H.; Wu, W. Smart Cellulose-Based Janus Fabrics with Switchable Liquid Transportation for Personal Moisture and Thermal Management. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.-H.; Cheng, D.-H.; Li, X.; Wang, H.-Y.; Lu, Y.-H.; Lou, C.-W. A Study on Tencel/LMPET–TPU/Triclosan Laminated Membranes: Excellent Water Resistance and Antimicrobial Ability. Membranes 2023, 13, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, R.; Du, L.; Li, H.; Shao, Z.-B.; Jiang, Z.; Zhu, P. Reasonable multi-functionality of cotton fabric with superior flame retardancy and antibacterial ability using ammonium diphosphate as cross-linker. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wu, Z.; Qu, M.; Chen, R.; Guo, J.; Bin, Y. Hydrophobic surface modified calcium alginate fibers for preparing flame retardant and comfortable Janus fabrics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 369, 124340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ren, Y.-L.; Xu, Y.-J.; Liu, Y. One-step and multi-functional polyester/cotton fabrics with phosphorylation chitosan: Its flame retardancy, anti-bacteria, hydrophobicity, and flame-retardant mechanism. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 203, 109179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Jiang, X.-C.; Song, W.-M.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Xu, Y.-J.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, P. Green organic-inorganic coatings for flexible polyurethane foams: Evaluation of the effects on flame retardancy, antibacterial activity, and ideal mechanical properties. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 411, 137265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, H.; Xu, Y.-J.; Wang, D.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, P. Flame-retardant and antibacterial flexible polyurethane foams with high resilience based on a P/N/Si-containing system. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 182, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Luo, C.-Y.; Zhu, P.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.-J. Facile construction of H3PO3-modified chitosan/montmorillonite coatings for highly efficient flame retardation of polyester–cotton fabrics. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 184, 107864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, A.; Shahidi, S.; Dorranian, D.; Saviz, S. In situ synthesize of ZnO nanoparticles on cotton fabric by laser ablation method; antibacterial activities. J. Text. Inst. 2022, 113, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Peng, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Dai, H.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.; Li, G. A Novel Moisture-Wicking and Fast-Drying Functional Bicomponent Fabric. Fibers Polym. 2025, 26, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, B.K.; Abtew, M.A.; Pawlos, M. Eco-friendly flame retardant and antibacterial finishing solutions for cotton textiles: A comprehensive review. J. Ind. Text. 2025, 55, 1–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Han, L.; Cong, H.; Dong, Z.; Ma, P. Wool/polyester mixed knitted fabrics with three-layer double-side structure for personal heat and humidity management. Text. Res. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 21655.1-2023; Textiles—Evaluation of Absorption and Quick-Drying—Part 1: Method for Combination Tests. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Broeren, M.A.C.; Maas, Y.; Retera, E.; Arents, N.L.A. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing in 90 min by bacterial cell count monitoring. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.C.; Zhao, Y.J.; Quan, Z.Z.; Zhang, H.N.; Qin, X.H.; Wang, R.W.; Yu, J.Y. An efficient hybrid strategy for composite yarns of micro-/nano-fibers. Mater. Des. 2019, 186, 108375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, N.; Qin, X.H.; Wang, L.M.; Yu, J.Y. Electrospun nanofiber/cotton composite yarn with enhanced moisture management ability. Text. Res. J. 2021, 91, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.H.; Chen, S.Y.; Li, Y.P.; Yang, Y.C.; Zhang, H.N.; Quan, Z.Z.; Qin, X.H.; Wang, R.W.; Yu, J.Y. Functional nanofibers embedded into textiles for durable antibacterial properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 384, 123241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teng, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Jin, X.; Wang, R. Antibacterial and Moisture Transferring Properties of Functionally Integrated Knitted Firefighting Fabrics. Polymers 2025, 17, 2915. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212915

Teng Z, Li Z, Zhang Y, Zhang C, Wang L, Li X, Jin X, Wang R. Antibacterial and Moisture Transferring Properties of Functionally Integrated Knitted Firefighting Fabrics. Polymers. 2025; 17(21):2915. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212915

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeng, Zhilin, Zhen Li, Yue Zhang, Chentian Zhang, Liming Wang, Xinxin Li, Xing Jin, and Rongwu Wang. 2025. "Antibacterial and Moisture Transferring Properties of Functionally Integrated Knitted Firefighting Fabrics" Polymers 17, no. 21: 2915. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212915

APA StyleTeng, Z., Li, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhang, C., Wang, L., Li, X., Jin, X., & Wang, R. (2025). Antibacterial and Moisture Transferring Properties of Functionally Integrated Knitted Firefighting Fabrics. Polymers, 17(21), 2915. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212915