2. Materials and Methods

Commercial poly(vinyl chloride) (PVS) and polystyrene (PS) (ChemRaw, Moscow, Russia) were used.

Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), PMMA plasticized with dibutyl phthalate (DBPh), and random copolymers of methyl methacrylate (MMA) with butyl methacrylate (BMA), octyl methacrylate (OMA), lauryl methacrylate (LMA), and methacrylic acid (MAA) were synthesized via bulk (co)polymerization.

Prior to (co)polymerization, the above monomers (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) were distilled in a vacuum under a nitrogen flow. Lauroyl peroxide (Sigma-Aldrich), used as the initiator, was purified by recrystallization from ethanol. The content of initiator in the polymerizing systems was 5 × 10–3 mol/L.

The monomer feed compositions were as follows: for MMA/BMA—80/20, 70/30, and 50/50; for MMA/OMA—95/5, 90/10, and 80/20; for MMA/LMA—95/5, 90/10, and 80/20; and for MMA/MAA—75/25. Before (co)polymerization, monomer mixtures containing the initiator were deoxygenated by repeated freezing–defreezing at a pressure of 10–2 mmHg.

(Co)polymerization was carried out in sealed glass tubes at 60 °C. To provide complete conversion, at the final stage of the reaction, the temperature was increased to a temperature which exceeded glass transition temperature of the corresponding (co)polymers by 10–15 °C.

Polyurethane foams (PUFs) with densities of 30, 45, and 60 kg/m3 were prepared by sputtering using the pilot setup Interskol 5H200 (Interskol, Moscow, Russia) under a pressure of 90 atm and at 22 °C. The density of each test sample was measured at room temperature by hydrostatic weighting.

Two-component composition involved commercial bifunctional aromatic polyester VP-3317 (Vladipur, Vladimir, Russia) and commercial aliphatic polyester VP-3700 (Vladipur, Vladimir, Russia) with a functionality of 2.3 (component A), and commercial polyisocyanate Wannate PM-200 (Wanhua Chemical, Yantai, China) (component B). The isocyanate index of compositions used—that is, the molar ratio between reactive isocyanate and alcohol groups [I] = [NCO]/[OH]—varied from 0.8 to 1.45. To align the viscosities of components A and B, oligomeric polyatomic alcohols were added to component A.

Freon/water and methylal/water systems were used as foaming agents. The density of the final PUFs was controlled by varying the content of foaming agent.

Mechanical testing of the samples was carried out using Insrtron 3400 (Instron, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Bulk PS, PVC, PMMA, and copolymer cylindrical samples with a diameter of 10 mm and a height of 10 mm were uniaxially compressed at 20, 40, 50, and 70 °C with strain rates of 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, and 10−5 s−1. PUF samples with a diameter of 20 mm and a height of 20 mm were uniaxially compressed at 20 °C with a strain rate of 10−3 s−1.

Young’s modulus was estimated as the slope of the linear initial portion of the “stress–strain” diagram with an accuracy of ±7%. The strain and stress corresponding to the proportional limit and yield point were estimated with an accuracy of ±4% and ±5%, respectively.

3. Results and Discussions

In an earlier study [

24], the rheological behavior of virgin and modified Chernozem, turf-podzolic soil, kaolinite, montmorillonite, and quartz sand pastes was studied using dynamic loading in amplitude sweep mode. The experimental results were discussed in terms of the complex modulus

, where

, , γ, τ′, and

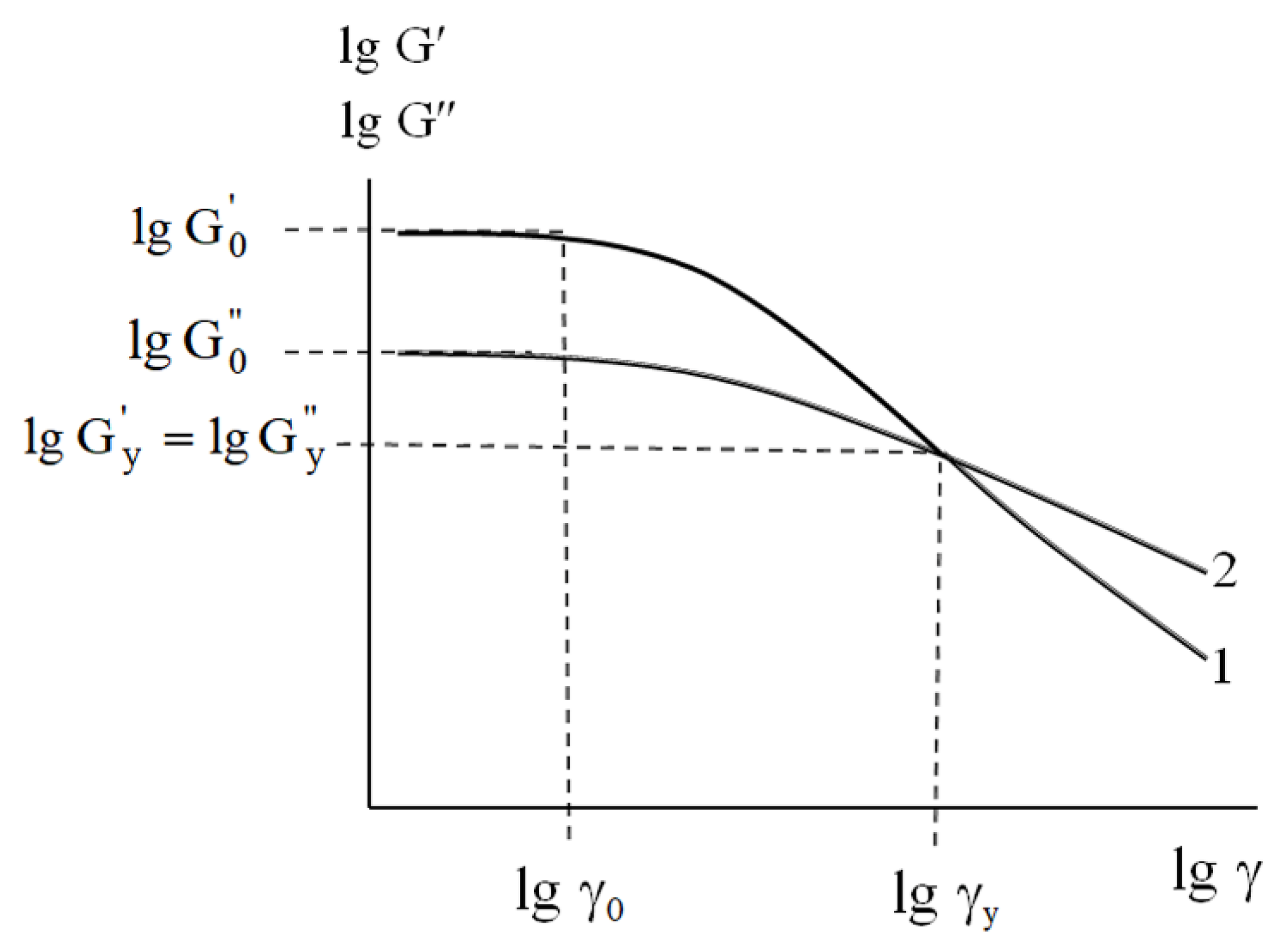

τ″ are the storage modulus, loss modulus, strain, and real and imaginary parts of complex stress, respectively. The typical dependences of

lg and

on strain

lg are shown in

Figure 1.

The typical results of the dynamic testing (

Figure 1) allowed us to recognize the following strain intervals and basic mechanical parameters which describe the rheological behavior of the dispersed soil-based pastes.

Within the strain interval

, the linear viscoelastic response of the samples is characterized by constant values of both the initial storage modulus

and the initial loss modulus

. The constancy of these parameters implies high stability of the material’s initial structure—that is, a physical network of mineral particles—under loading conditions [

25,

26].

At

, under strain growth, a decrease in both

and

is associated with the partial microscopic rupture of inter-particle contact, followed by the complete macroscopic destruction of the abovementioned physical network. For the dispersed systems, macroscopic physical network destruction is considered to represent “yielding” [

27,

28,

29]. Yielding manifests as a cross-over point at the yield strain

when

(

Figure 1). Obviously, at

, the elastic response prevails (

), while at

, well-pronounced fluidity occurs (

).

From this standpoint, the experimental parameters , , , and completely describe the rheological behavior of the materials. Note that the pair and represents the ultimate operation characteristics of the dispersed bodies when a complete loss of load resistance takes place.

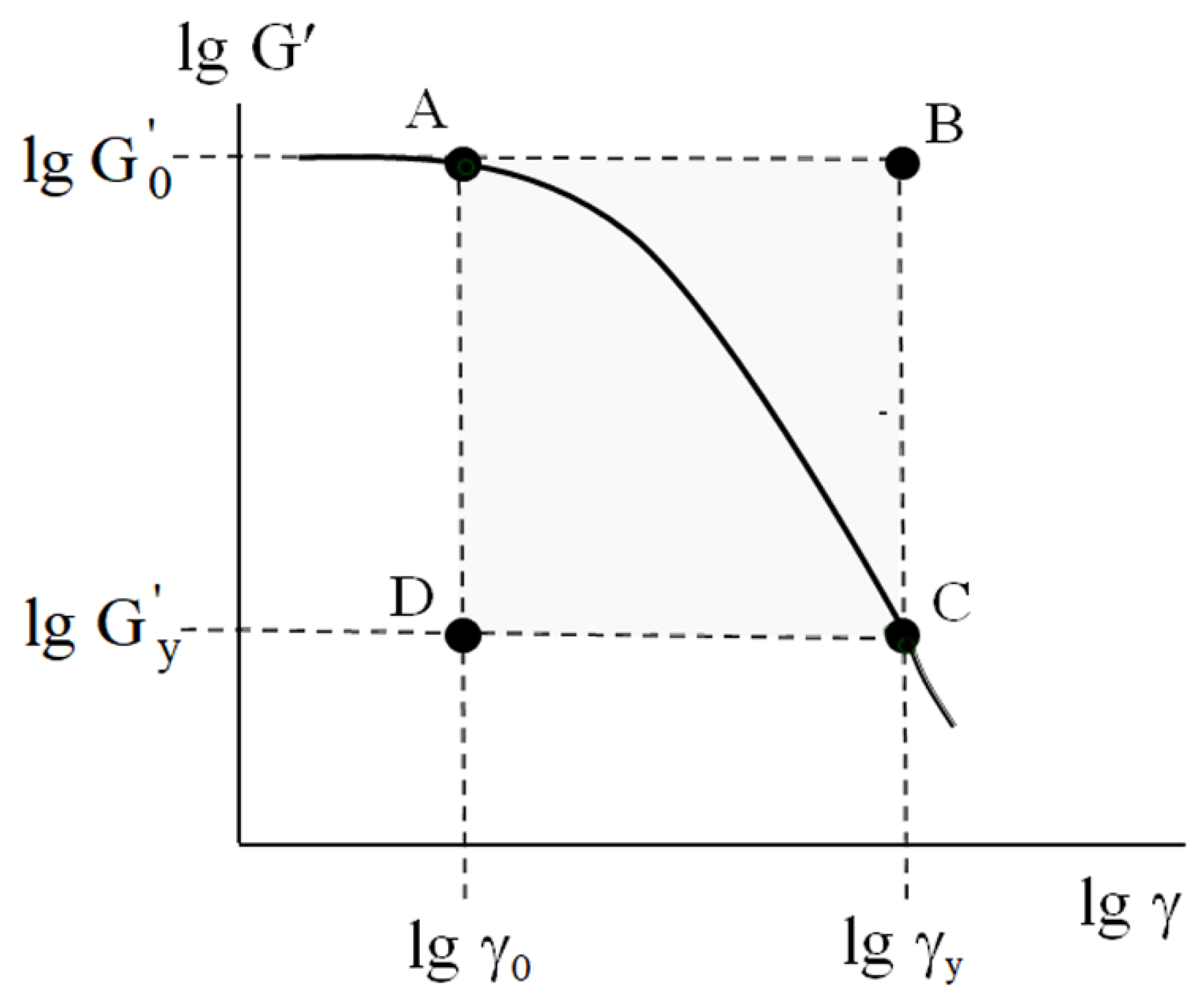

From both fundamental and applied viewpoints, the portion of the rheological curve

(curve 1,

Figure 1) in the strain interval

is of the most interest. This range corresponds to the mechanically activated transition (MAT) from linear viscoelasticity to yielding, accompanied by the complete destruction of the structural network. In

Figure 2, which details the strain dependence of the storage modulus, the MAT region is schematically represented as a highlighted area.

Obviously, the coordinates of corners A, B, C, and D of the rectangular MAT box are set by the couples of parameters ( and ), ( and ), ( and ), and ( and ), respectively. In other words, the size of the MAT box is defined as .

For the soil-based pastes studied (more than 50 virgin and modified samples), linear correlations between (A)

and

, (B)

and

, and (C)

and

were found [

24]. These “property–property” correlations provide evidence that the rheological parameters

,

, and

of the dispersed samples are strictly determined by the value of initial storage modulus

. The higher the

value is, the higher the

value is and the lower the

and

values are.

Hence, experimental measurement of the value provides an estimation of the , , and values without direct experimental testing. Note that the value of is considered to represent the upper strain limit of viscoelasticity. The values of and correspond to yielding—that is, the upper limit of the material’s operation.

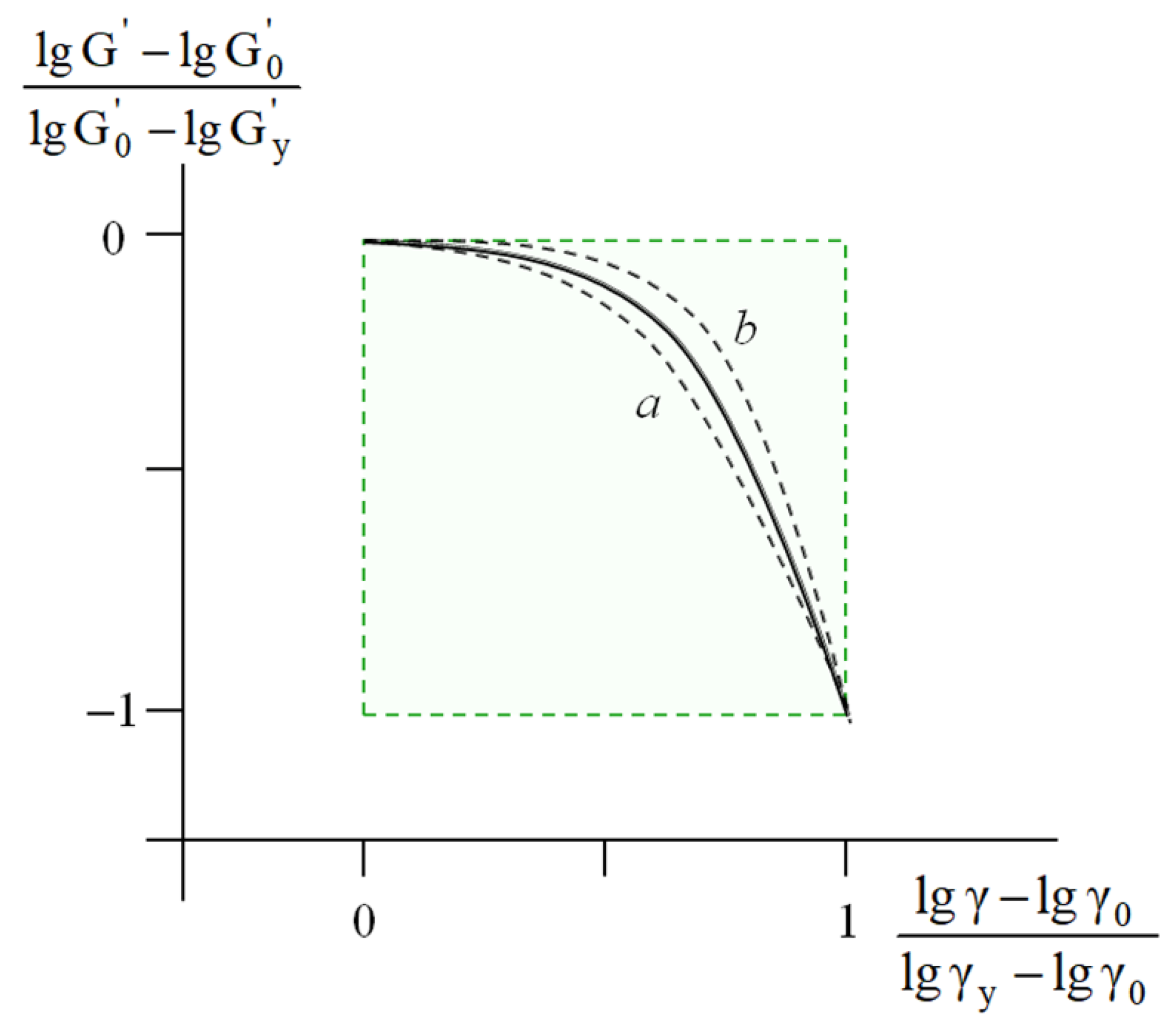

These correlations allowed us to propose a procedure for the unification of the rheological behavior of the soil-based pastes within the MAT box [

24]. This approach involved the treatment of the experimental curves

lg G′ = f (lg γ) in the dimensionless reduced coordinates

, and the construction of unified master curve for all the samples studied (

Figure 3).

Hence, the results obtained allow one to conclude that, in the wide range of applied strain, the rheology of the dispersed soil-based pastes is controlled by the initial values of the storage modulus .

From a practical viewpoint, the construction of the master curve (

Figure 3) enabled prediction and express analysis of the rheological behavior of both the virgin and modified soil-based pastes using only one experimentally measured parameter—

. The algorithm and verification of this procedure are detailed in [

24].

In this case, the following question arises: Are these results unique to the rheology of dispersed pastes, or they can be applied to describe the mechanical behavior of solid plastics? To clarify this problem, the following analysis of the mechanics of the plastic bodies was carried out.

To study mechanical behavior of plastics, the deformation under regimes of shearing, uniaxial drawing, uniaxial compression, torsion, bending, etc., of samples with a fixed strain rate

is widely used [

1,

2,

7]. The results of mechanical testing are usually represented as the dependence of stress

σ on strain

ε (“stress–strain” diagram) (

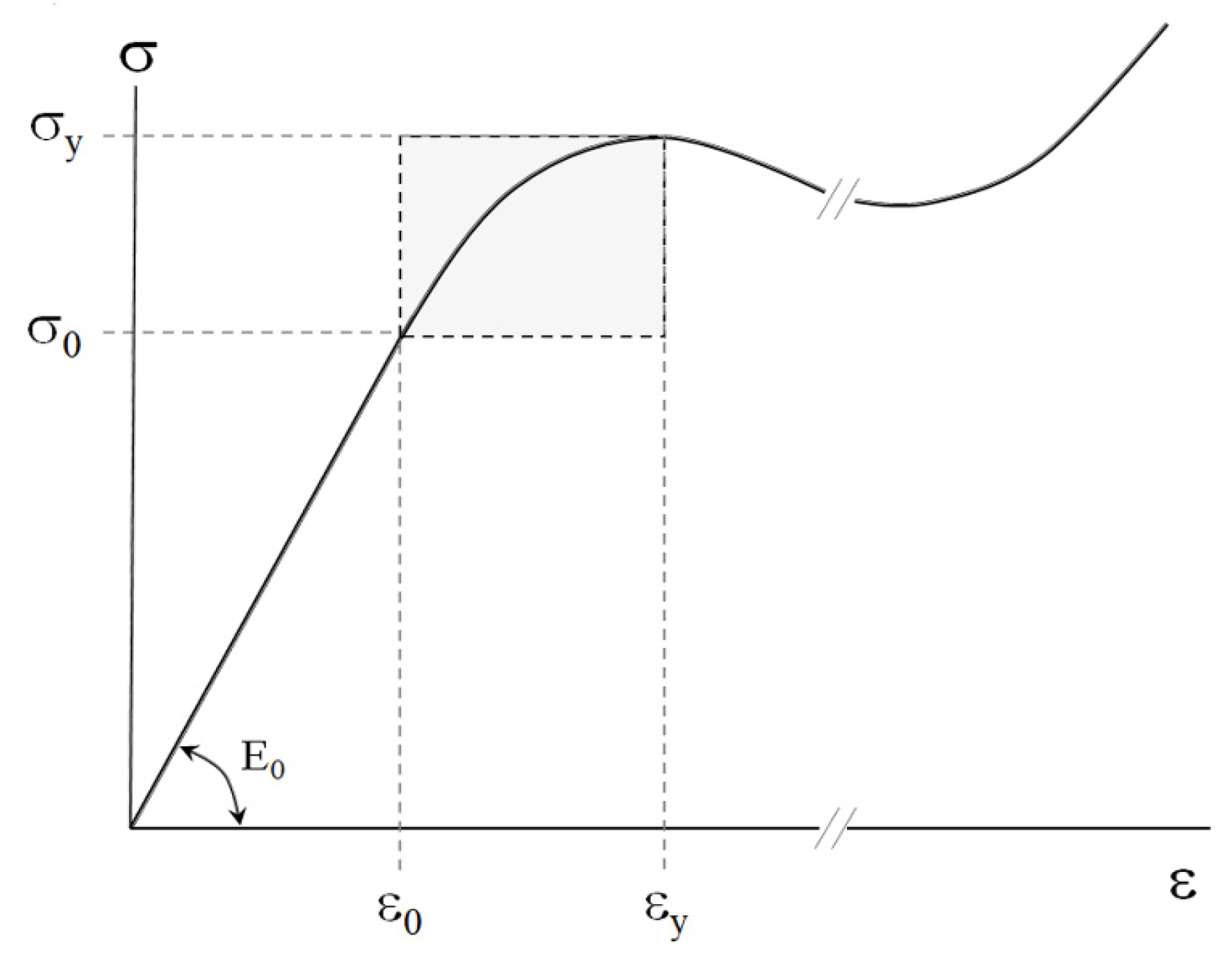

Figure 4).

Note that, for plastics, typical stress–strain behavior (

Figure 4) is characterized by the proportional limit at

σ0 and

ε0 and the yield point at

σy and

εy.

At and , the linear viscoelastic response of the plastics obeys Hooke’s law and is characterized by Young’s modulus .

At

, macroscopic yielding or mechanically activated steady-state fluidity of the material takes place. Similarly to the rheological behavior of the abovementioned dispersed bodies, mechanically activated transition (MAT) from linear viscoelasticity to yielding at

occurs (highlighted area in

Figure 4).

For the virgin soils and the soils plasticized with dibutyl phthalate (DBPh) poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), polystyrene (PS), and poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC), as well as the copolymers of methyl methacrylate (MMA) with butyl methacrylate (BMA), octyl methacrylate (OMA), lauryl methacrylate (LMA), and methacrylic acid (MAA), studied in this work, detailed examination of their stress–strain behavior under uniaxial compression at the specified deformation temperature

Tdef and strain rate

was carried out (

Table 1).

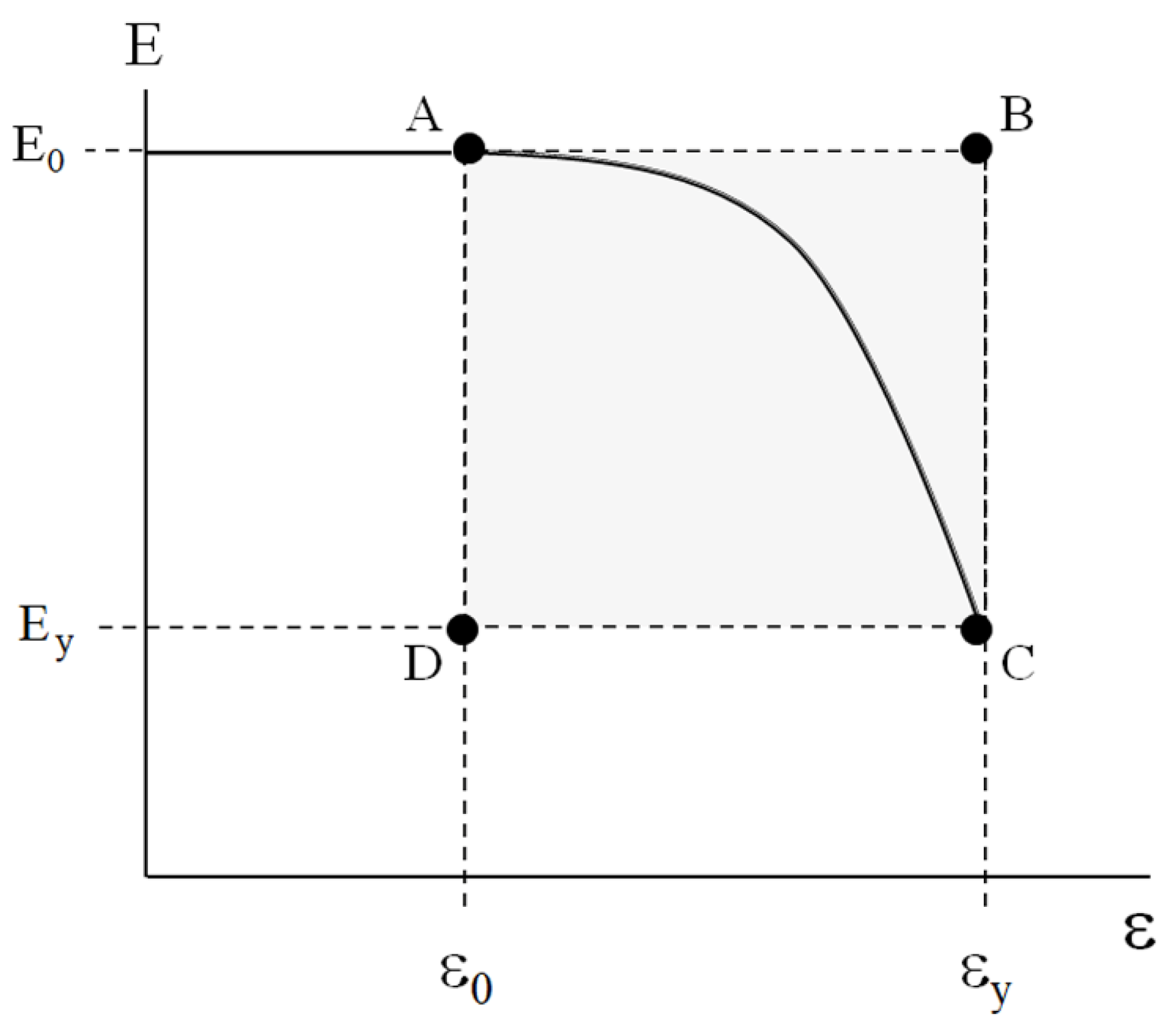

For comparative analysis of the dispersed bodies’ rheology and the plasticity of the bulk polymers, the stress–strain diagrams of the plastic samples were re-calculated in the coordinates

, where

is the current modulus of the material. The typical strain dependence of the current modulus is shown in

Figure 5.

Obviously, at

, the initial modulus

E0 is constant. Within the MAT box (highlighted area in

Figure 5), the current modulus

E falls and reaches the value of

. Corners A, B, C, and D of the rectangular MAT box correspond to the couples of parameters (

E0 and

ε0), (

E0 and

εy), (

Ey and

εy), and (

Ey and

ε0), respectively. The size of the MAT box is defined as

(E0 − Ey) × (εy − ε0).

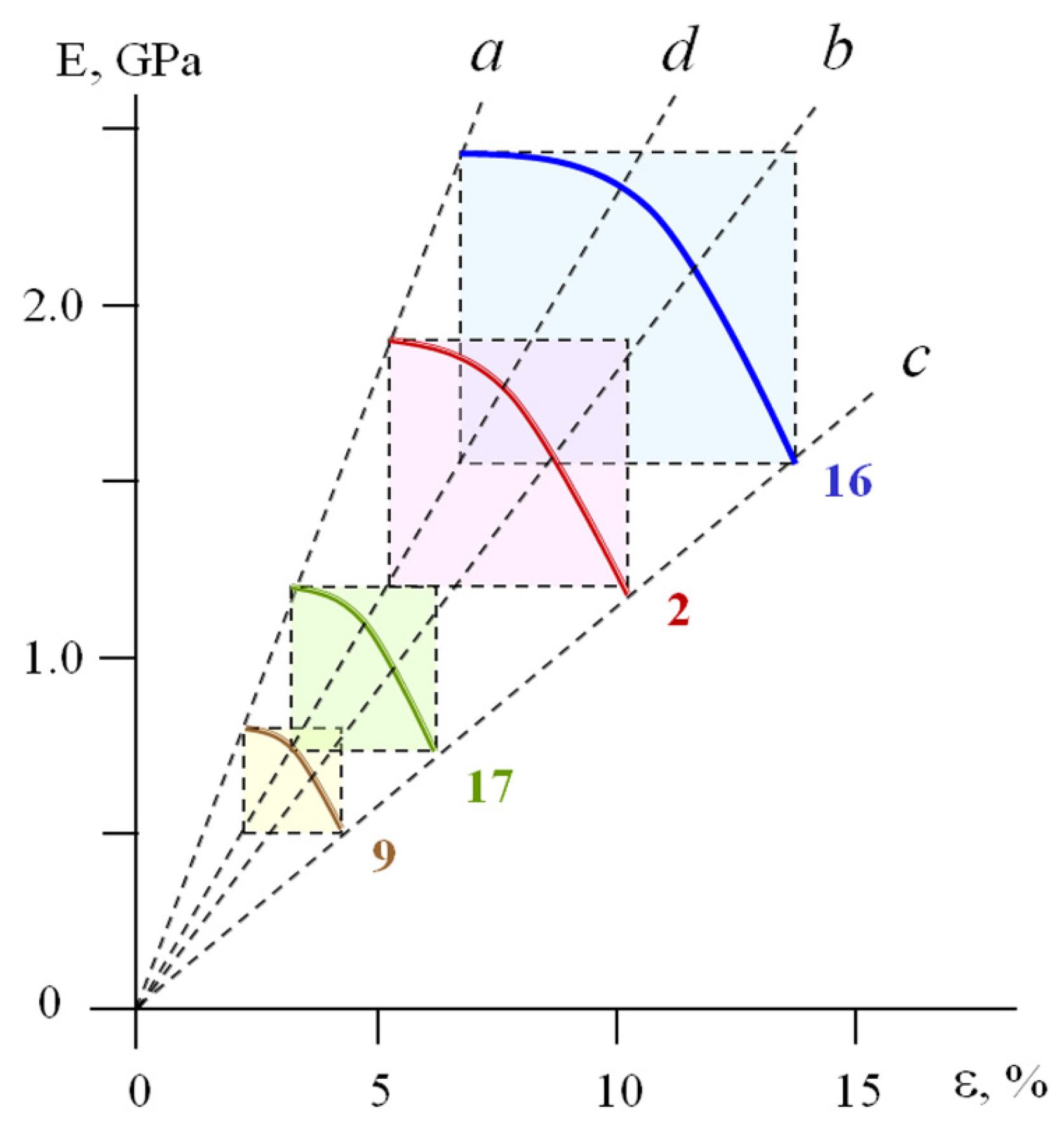

For samples 2, 9, 16, and 17 (

Table 1), their MAT boxes are shown in

Figure 6. Lines a, b, c, and d go through corners A, B, C, and D of these rectangular MAT boxes, respectively, and imply the linear dependences

,

,

, and

.

For an individual polymer, the values of E0, ε0, Ey, and εy decrease as a result of plasticization, a decrease in the strain rate , and an increase in the deformation temperature Tdef.

In our earlier work [

7,

30,

31], for the stress–strain behavior of carbon chains, hetero-chains, and hetero-cyclic polymers, the following ratios of the mechanical parameters were found:

or

and

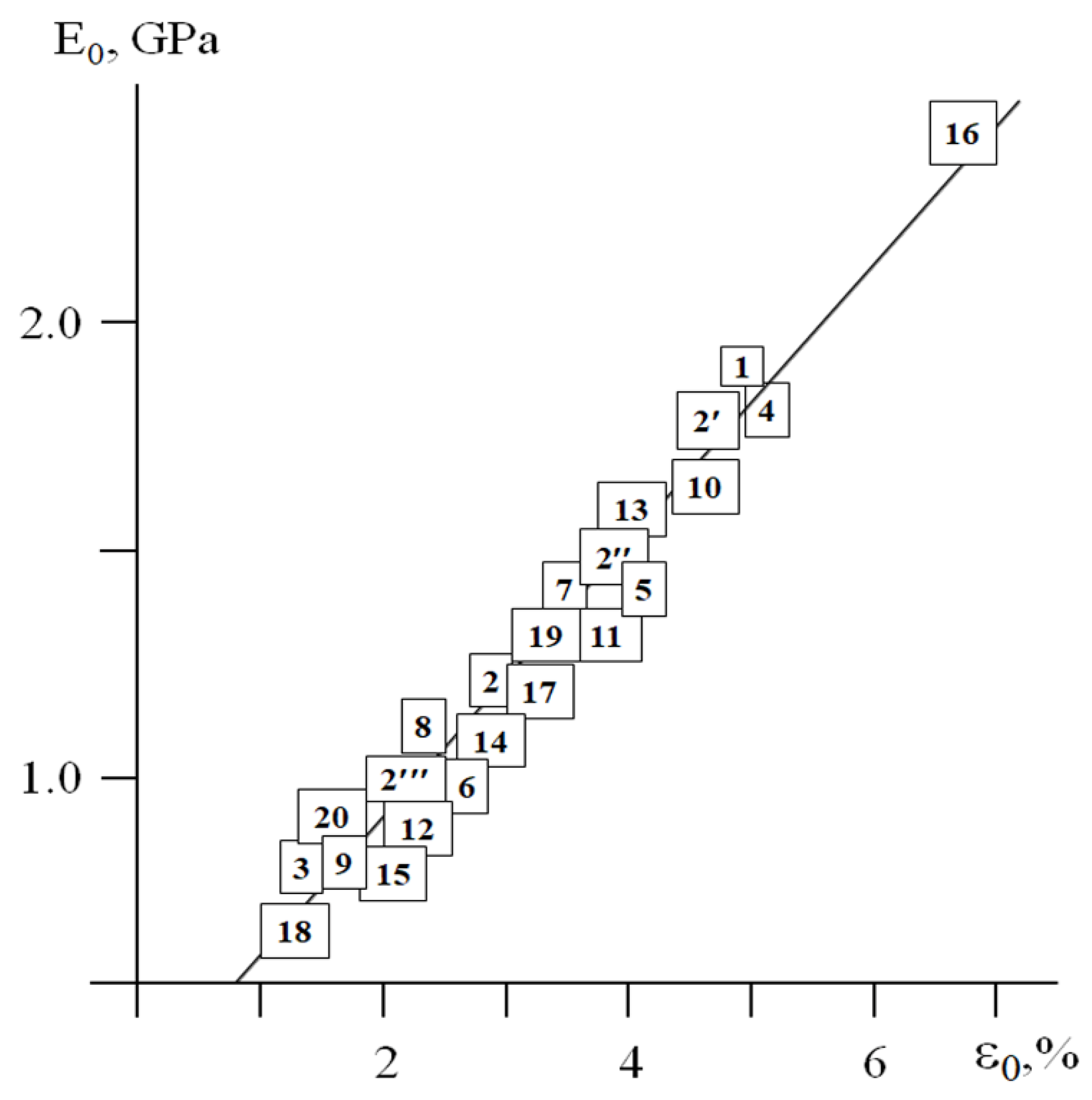

Expressions (1) and (2) demonstrate that the dimensions of the MAT box

(E0 − Ey) × (εy − ε0) are controlled by only two parameters—

E0 and

ε0. For the plastic samples listed in

Table 1,

Figure 7 shows the correlation between these two characteristics.

Note that the plastics (

Table 1) with the different chemical structure tested at a fixed

Tdef and

(samples 1, 7–17, 19), the plasticized polymers (4–6) and individual polymers tested at a fixed

and different

Tdef (1–3, 17–20), and the polymers tested at a fixed

Tdef and different

(2′, 2″, 2, 2′″) satisfy this dependence. In other words, this

correlation takes into account the influence of the chemical and physicochemical modification of the polymers, as well as the influence of the time–temperature regime of deformation on the mechanical behavior of the plastics.

Expressions (1) and (2) and

Figure 7 demonstrate that, for the plastics, the size of their MAT boxes is set by the only one parameter: the initial modulus

E0. Experimental measurement of this parameter allows one to estimate (1) the value of

ε0 using the linear correlation shown in

Figure 7, and (2) the values of

Ey and

εy using Expressions (1) and (2)—that is, the complete set of characteristics that describes the plasticity of a polymer.

Similarly to the bulk plastics, rigid polymeric foams demonstrate well-pronounced plasticity, with the yield point characterized by the yield stress

σy and the yield strain

εy [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

As for bulk plastics, the mechanical parameters (E0, σy, εy, σ0, and ε0) of the foams depend on the chemical structure of the polymer, as well as on the time–temperature regime of the deformation. With a decrease in the deformation temperature Tdef and an increase in the strain rate , linear growth in these charasteristics is observed.

Note that the mechanical behavior of the polymeric foams is mainly controlled by their density. A decrease in the density results in a decrease in the above mechanical parameters of the foams. Additional factors which affect the mechanical properties of foams are associated with (1) the morphology of the cellular structure, (2) the configuration and size of both the cells and intercellular walls, (3) the nature of gas which fills the cells (air, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, freon, etc.), and (4) the foam production technology used.

Hence, as compared with bulk plastics, a description of the mechanical behavior of polymeric foams is considered a more complicated problem when the above factors are taken into account.

In this work, to advance in this scientific direction, mechanical testing of a series of PUF samples prepared by sputtering was carried out. The chemical structure and composition of the samples were varied by the usage of aromatic and aliphatic polyesters, as well as by variation of isocyanate index [I] = [NCO]/[OH] from 0.8 to 1.45. The density of the foams was varied from 30 to 60 kg/m3 by variation of the content of two types of foaming agents (freon/water and methylal/water systems).

To gain a deeper insight into the mechanical behavior of these materials, stress–strain diagrams from the literature for PUFs with different chemical structures—polyvinylchloride, polystyrene, and polyethylene foams produced via casting, extrusion, and spraying—were analyzed. These samples, which had a density ranging from 30 to 980 kg/m

3, were uniaxially compressed at –54, 20, and 74 °C with strain rates of 10

–4, 10

–3, and 10

–2 s

–1 [

32,

35,

36,

39].

The treatment of our own data and data from the literature concerning the mechanical behavior of the above foams (more than one hundred stress–strain diagrams) revealed the following correlations:

and

As for the bulk plastics and foams, a linear correlation between E0 and ε0 was found (Pearson’s r is 0.95674).

The above correlations (Expressions (1)–(4),

Figure 7) were based on the treatment of experimental “stress–strain” diagrams for both bulk and cellular polymeric materials.

To expand this approach to other types of ductile bodies (for example, metal glasses), systematic and profound long-term studies are required. In this paper, to verify the validity of the correlation analysis, the results of the computer simulation of plastic deformation were invoked. Note that the computer-simulated mechanical response reflects regularities of plasticity that are general for materials with different natures, origins, structures, etc.

Computer-simulated “stress–strain” diagrams characterized by a well-pronounced MAT region and a yield point were considered. Analysis involved the following models, theoretical approaches, and deformation regimes: shearing of binary systems of disks [

40]; molecular–dynamic simulation of low-temperature uniaxial compression and extension [

9]; uniaxial extension and shearing in the framework of the atomistic–continuum model [

41]; uniaxial compression using a free-volume-based constitutive model [

11]; and damage plastic modeling of uniaxial tension [

19]. The simulated “stress–strain” diagrams were re-calculated in

coordinates and the values of

E0, Ey, ε0, and

εy were estimated. For these parameters, the following correlations were found:

and

Let us summarize the set of the results based on the treatment of more than 200 experimental stress–strain diagrams for (1) bulk plastics, (2) cellular polymeric foams, and (3) virtual models under shearing, uniaxial drawing, and compression with a fixed strain rate.

For all the samples studied, deformation behavior is characterized by the mechanically activated transition (MAT) from linear viscoelasticity to macroscopic fluidity or yielding. The dimensions of the MAT region are written as . Note that the yield point with coordinates corresponds to the ultimate operation characteristic when a complete loss of load bearing capacity takes place.

For both the bulk plastics and the cellular foams, as well as for the virtual models, the experimental and computer-simulated deformation behavior obeys similar regularities associated with the comparable values of the ratios

and

(

Table 2).

These ratios can be considered the criteria for yielding. Macroscopic yielding takes place when the current strain

ε approaches the yield strain

εy (ε → εy) and the current modulus

E approaches the yield modulus

Ey (E → Ey). Taking into account the average values of the corresponding ratios (

Table 2), yielding occurs when

and

.

The above correlations demonstrate that the dimensions of the MAT regions are controlled by the only one parameter—Young’s modulus

E0. The experimentally measured value of

E0 specifies unambiguously (1) the value of

ε0—that is, the upper strain limit of the linear viscoelasticity region (

Figure 7)

— and (2) the values of

(

Table 2), which define the yield point of the material. In other words, the value of

E0 allows one to estimate the abscissa of point A (

ε0) and (2) the position of point C

(

Figure 5) without direct experimental testing.

However, these results provide no information concerning the path of the system from point A to point C within the MAT box (

Figure 5). To reveal the regularities of this trajectory, let us invoke the procedure proposed in [

24] to unify the rheological behavior of both the virgin and modified soil-based pastes.

For the bulk plastics, the above correlations of the basic mechanical parameters (

Figure 7,

Table 2) imply the geometrical similarity of the MAT boxes (

Figure 6). Their dimensions are controlled by a change in the chemical nature and composition of the materials, as well as the time–temperature regime of their deformation. Obviously, these geometrically similar rectangles within a portion of the deformation curves can be transformed into each other as follows.

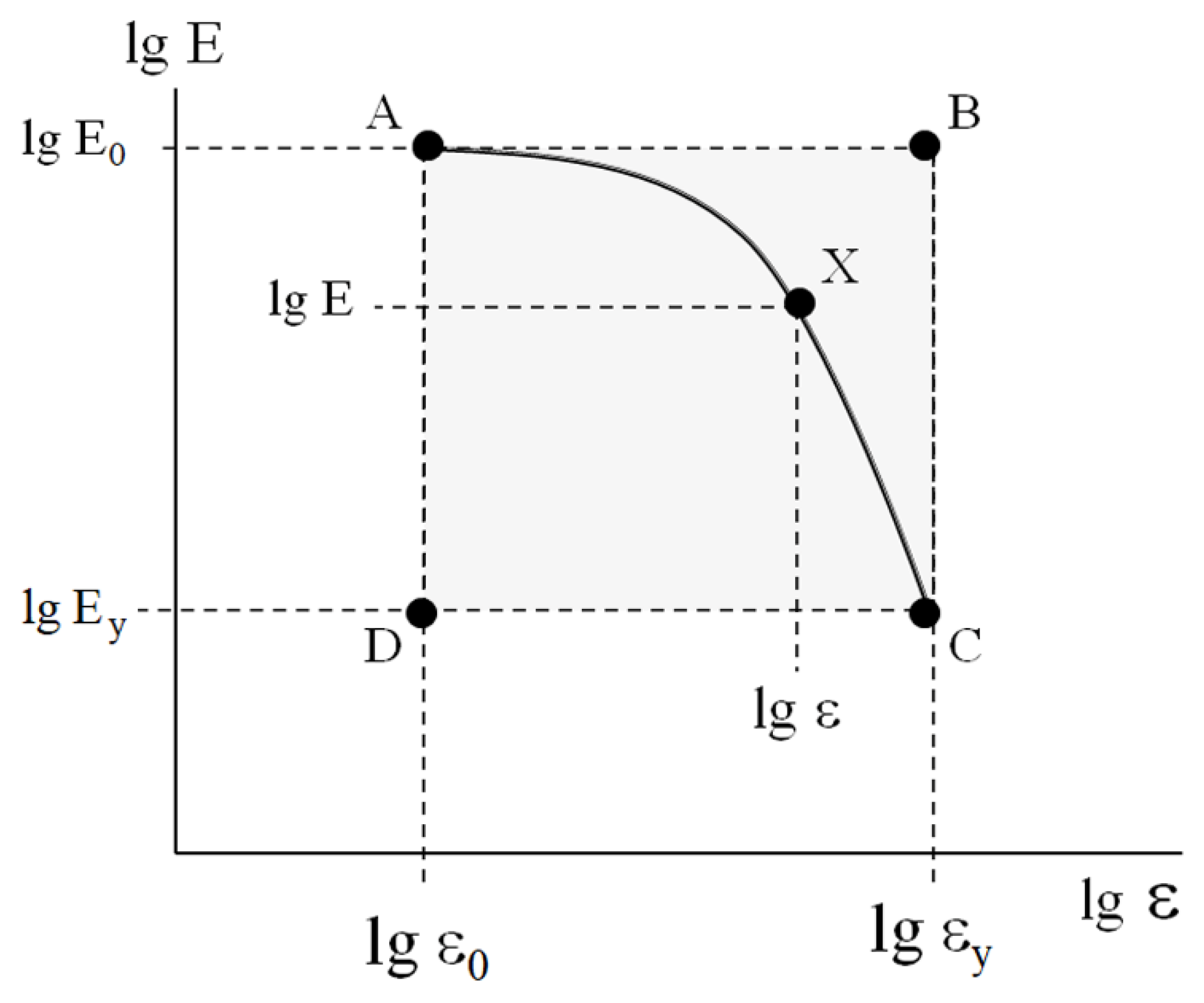

To compare the results concerning the mechanical behavior of the bulk plastics and the rheology of the soil-based pastes [

24], let us represent the MAT box (

Figure 5) on a logarithmic scale (

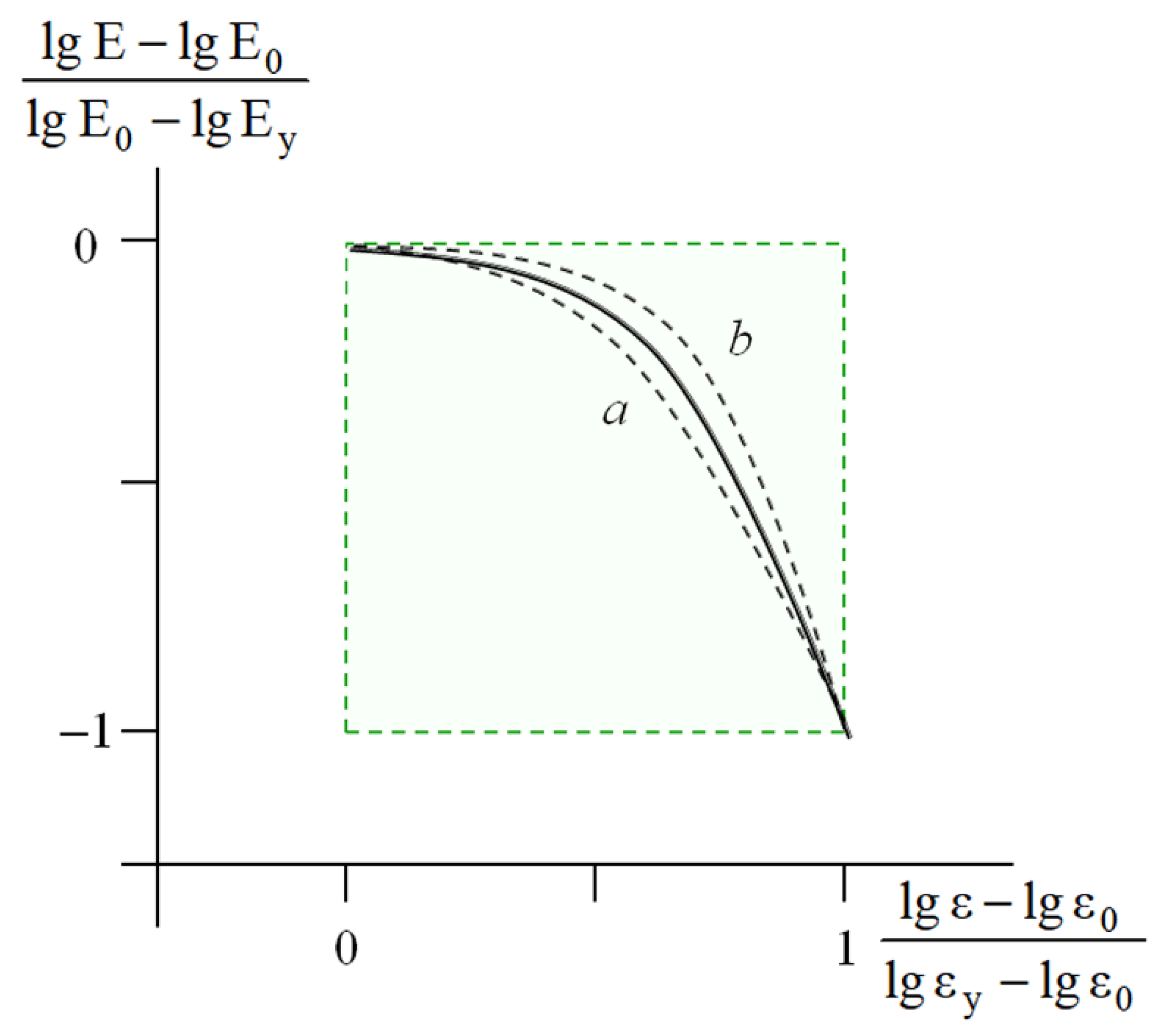

Figure 8). Note that point A restricts the interval of linear viscoelasticity and point C corresponds to the yield point.

In this case, for any point X (

Figure 8) with the coordinates

, the deviation of the value of the current modulus

lg E from the initial value

lg E0, namely,

was normalized by the height of the MAT box—

. The abscissa of the MAT box was re-calculated in a similar way. The resulting master curve in the coordinates

is shown in

Figure 9.

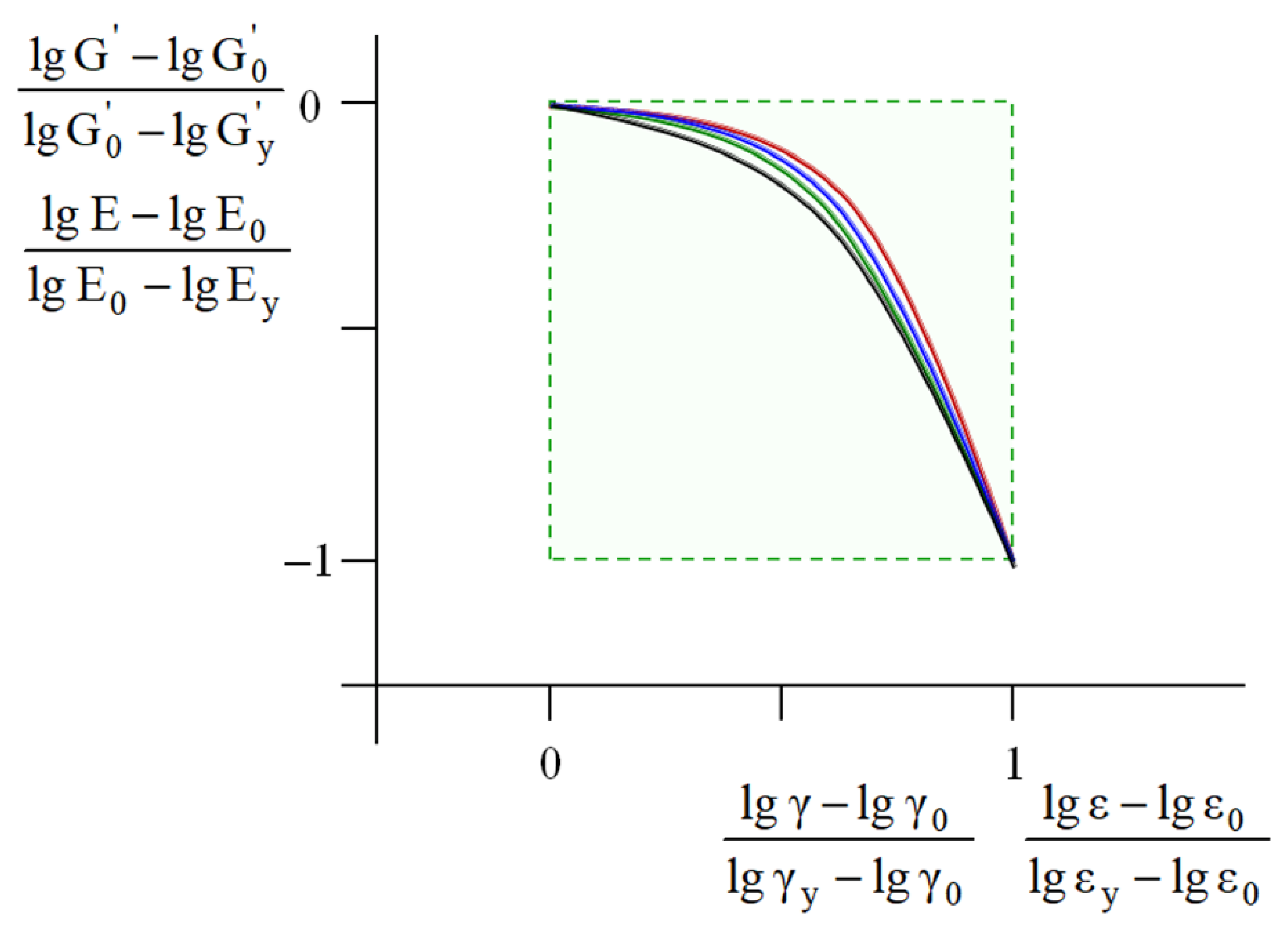

Similar master curves were constructed for the uniaxially compressed polymeric foams and computer-simulated virtual models. For the physical and virtual systems studied in this work, as well as for the soil-based pastes [

24], the master curves are in good agreement (

Figure 10).

The obtained results demonstrate that within the MAT region, the mechanical response of the materials obeys strict regularity, independent of their origin, their chemical structure, their morphology, their physicochemical modification, and the time–temperature regime of the deformation.

4. Conclusions

For (1) bulk ductile (co)polymers, (2) polymeric foams with different cellular morphology, and (3) various virtual models, the mechanically activated transition (MAT) from linear viscoelasticity to yielding was analyzed.

The MAT region is restricted by the proportional limit, with the coordinates

E0 and

ε0, and the yield point, with the coordinates

Ey and

εy (

Figure 5). Note that, in practice, the yield point is considered the ultimate operational characteristic of plastics when a complete loss of load resistance takes place. The size of the MAT box

(E0 − Ey) × (εy − ε0) depends on the chemical structure, composition, and morphology of the materials, as well as on the time–temperature regime of testing.

The significance of studies in the MAT region is associated with the fact that this phenomenon is an essential part of the deformation of ductile bodies. This event precedes yielding, and thus controls the operational behavior of the material.

For the mechanical characteristics (

E0, ε0, Ey and

εy) restricting the MAT region, quantitative correlations were found—

and

(

Table 2).

These correlations imply the following criteria for yielding: yielding occurs when the current modulus

E falls by

as compared with Young’s modulus

E0, and when the current strain

ε reaches a value of (2.1 ± 0.2) × ε

0. Note that the values of

E0 and

ε0 are in linear correlation (

Figure 7).

The obtained results demonstrate the geometrical similarity of the rectangular MAT boxes (shown for bulk plastics,

Figure 6). These geometrically similar rectangles can be transformed into each other via re-calculation of the experimental curves

in the dimensionless reduced coordinates

.

This procedure resulted in the construction of the master curve shown in

Figure 9 for the bulk plastics. Similar master curves were constructed for the deformation of polymeric foams and computer-simulated deformation of various virtual models.

The satisfactory coincidence of the master curves for the dispersed soil-based pastes [

24] and the materials studied in this work indicate that their mechanical response within the MAT region satisfies the strictly defined pathway (

Figure 10).

Obviously, the abovementioned physical bodies and virtual objects are characterized by a different nature, structure, and origin; their only common feature is well-pronounced plasticity or yielding. In connection with this, they can be denoted as “plastic systems”. These systems are associated with sustainable correlations between basic mechanical characteristics (

Table 2,

Figure 7), as well as with a strictly defined trajectory of the mechanical response within the MAT region (

Figure 10). Note that this unification is based only on the analysis of more than 300 experimental and computer simulated results, with no involvement of theoretical models or deformation mechanisms.

The above analysis of the mechanical behavior of the plastic systems allowed us to conclude that, for these systems, the mechanical response up until the yield point is strictly controlled only by the initial storage and Young’s modulus. These key characteristics specify (i) the upper strain limit of the linear viscoelasticity region and γ0, (ii) the parameters of the yield point—the pairs and (, γy), and (iii) the ratios and as the criteria for yielding.

The initial modulus can be considered a macroscopic manifestation of the initial state of the plastic system. Obviously, for the materials studied (dispersed bodies, bulk plastics, porous foams), as well as for the virtual models, their initial state is characterized by their different structural organization. However, the initial structure unambiguously sets (i) the pathway of the plastic system within the MAT region and (ii) the parameters of the yield point, that is, the upper operation limit. Note that, for the plastic systems, the similarity between their mechanical trajectories (

Figure 10) does not imply similarity in the mechanically stimulated structural evolution that is responsible for and/or accompanies their deformation.

As mentioned above, from the applied standpoint, the construction of master curves (

Figure 3) enabled express analysis of the mechanical behavior of the dispersed soil-based pastes using only one experimentally measured parameter—

[

24]. The good agreement of the master curves for the dispersed, bulk, and cellular materials (

Figure 10) indicates that this approach can be applied to the express analysis of plastics and foams. Similarly to the algorithm detailed in [

24], the procedure involves (1) experimental measurement of Young’s modulus

E0; (2) estimation of the values of

ε0, Ey, and

εy using the above correlations (

Figure 7,

Table 2); (3) substitution of these parameters in the coordinates

; (4) re-calculation of the master curve into the current value of

E and

ε; and (5) construction of

E dependence without a direct experiment.

Note that, at the present time, the mechanical behavior of each type of material analyzed in this work (dispersed pastes, bulk plastics, and cellular foams) is described in terms of various structural models, deformation mechanisms, and theoretical approaches [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

18]. Deeper insight into their plasticity mechanisms is provided by computer simulation of deformation with various virtual models [

9,

11,

19,

40,

41]. In this paper, the general regularities of plasticity of these physical bodies and virtual models were attributed to the correlations of their basic mechanical parameters (

Table 2) and unified master curves (

Figure 10). The results obtained are characterized by their predictive nature and provide analysis of the operational behavior of ductile bodies using only one experimental parameter—the initial storage modulus (for dynamic testing) and Young’s modulus (for deformation with the fixed strain rate).

Future advancement in this scientific field requires comprehensive research that includes studies on the mechanical behavior of inorganic and metallic plastic materials, as well as theoretical justification and mathematical modeling of the abovementioned regularities.

The limitations of this methodology based on correlation studies followed by the construction of unified master curve are as follows. This approach is not applicable to labile materials for which mechanically stimulated phase and polymorphic structural transformations take place in the course of deformation. A prime example of these kinds of materials is polyethyleneterephtalate (PET). Deformation of PET samples is accompanied by crystallization caused by the orientation of the polymer chains. This factor is responsible for continuous changes in the structure of the polymer and resulting continuous changes in the mechanical response of the sample.

Obviously, for multi-phase and multi-component blends and composites, the deformation regularities are more complicated as compared with those for the polymeric materials discussed above. The mechanical response of blends and composites is controlled by the superposition of the micro-mechanical behavior of the components and the interphase boundary, synergetic effects, etc. These factors are specific and unique to a given composition and prevent a general description of the plasticity of these materials.