Preparation and Application of Responsive Nanocellulose Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Preparation of Magnetization Modified Cellulose Nanofibrils Composite Materials (MMCNF)

2.3. Preparation of MMCNF/Poly (NIPAM) Semi-IPN Composite Materials (MMCNF-PNA)

2.4. Characterization

2.5. Batch Adsorption

2.6. Adsorption Mechanism Study (Isotherm Models and Kinetic Models)

2.7. Desorption and Reusability

3. Results and Discussion

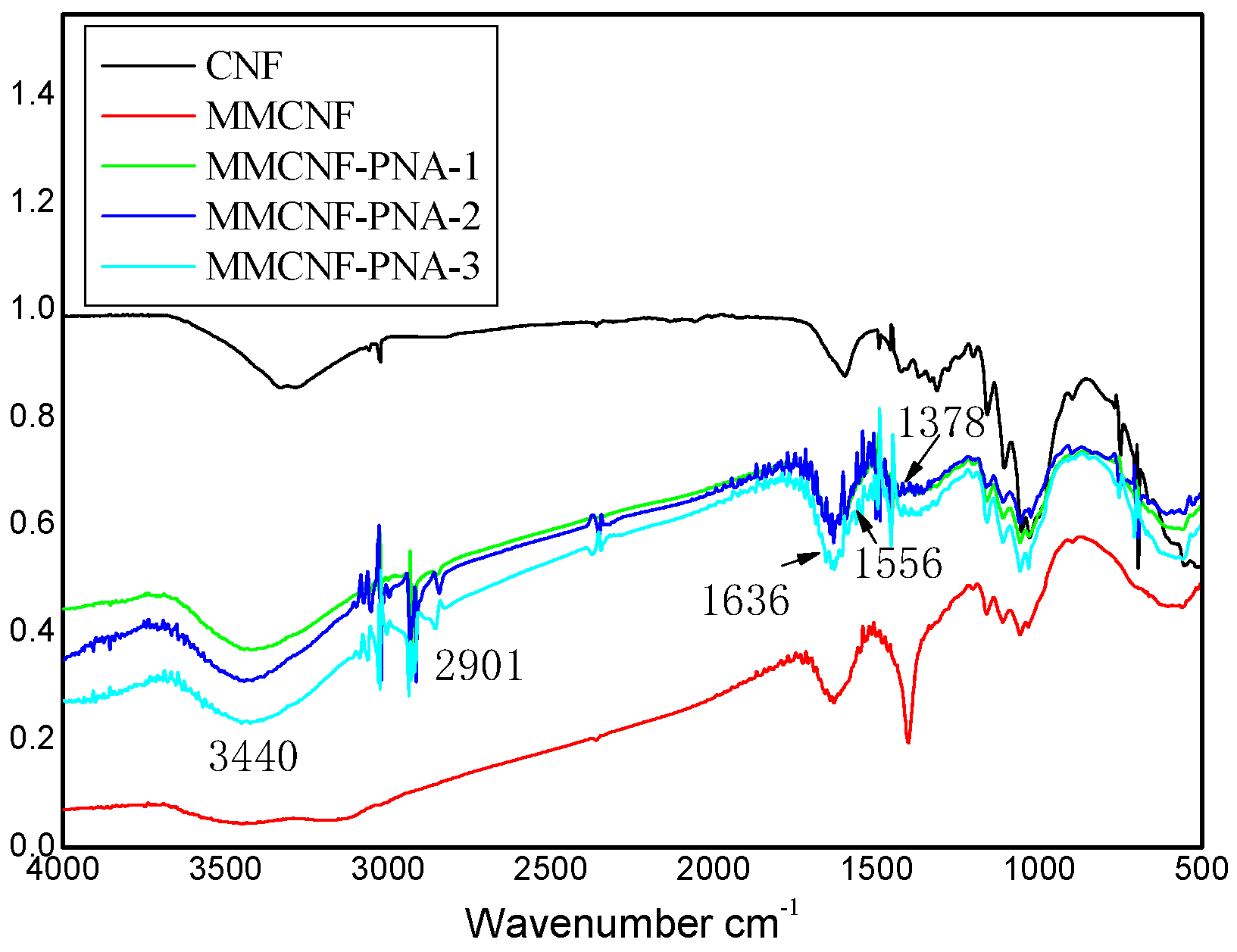

3.1. FTIR

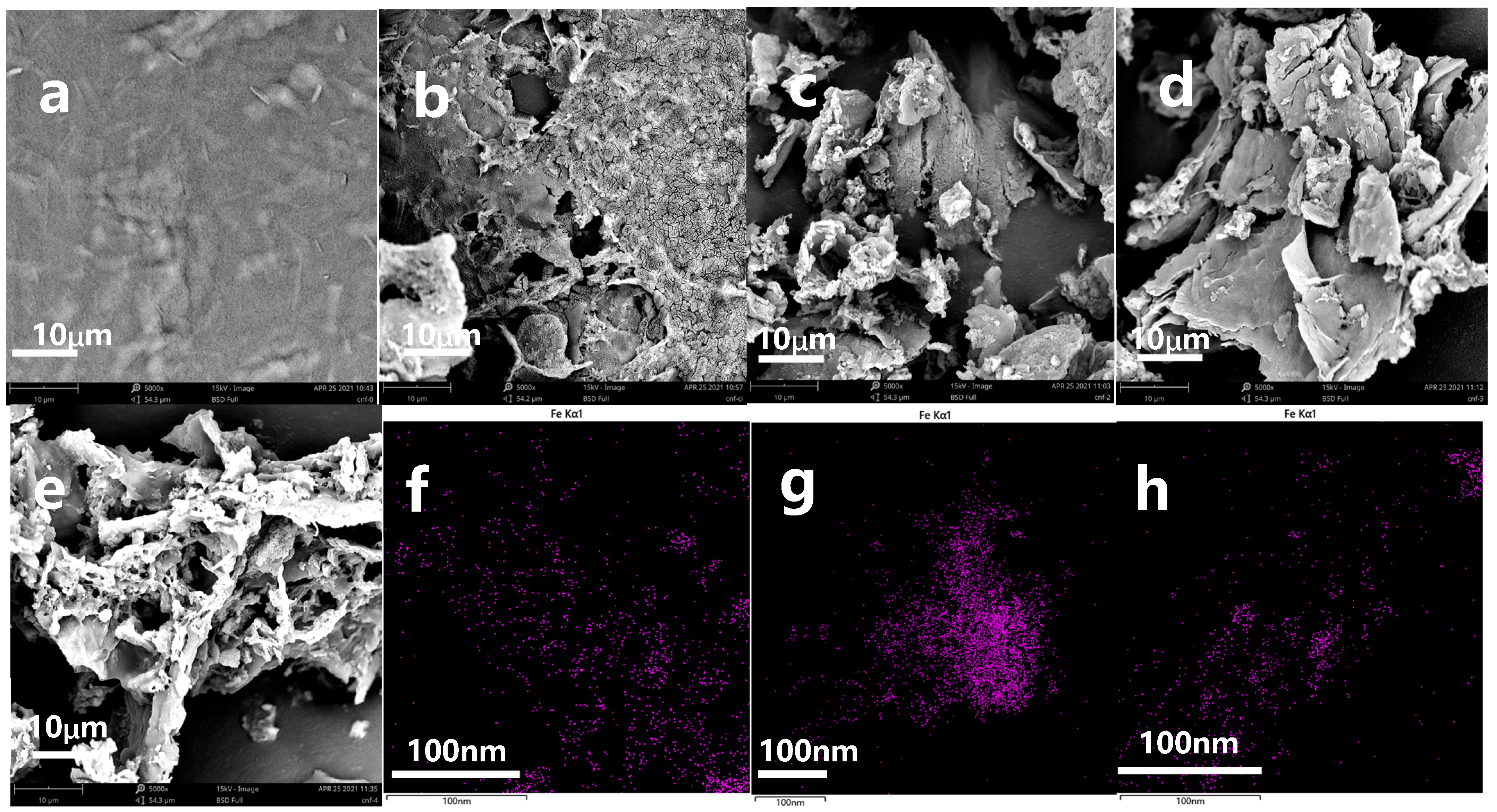

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

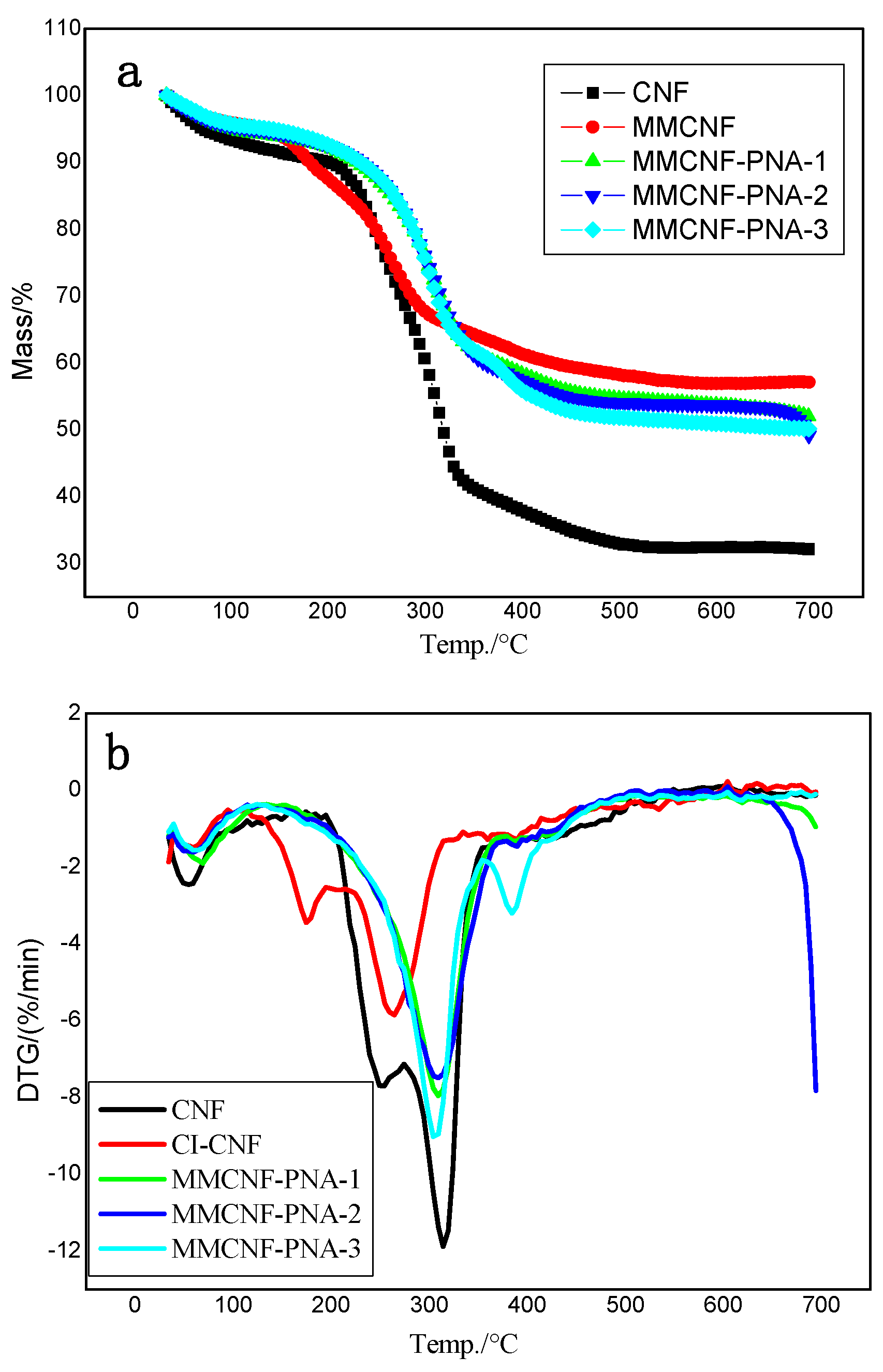

3.3. Thermal Gravimetric Analyzer (TGA)

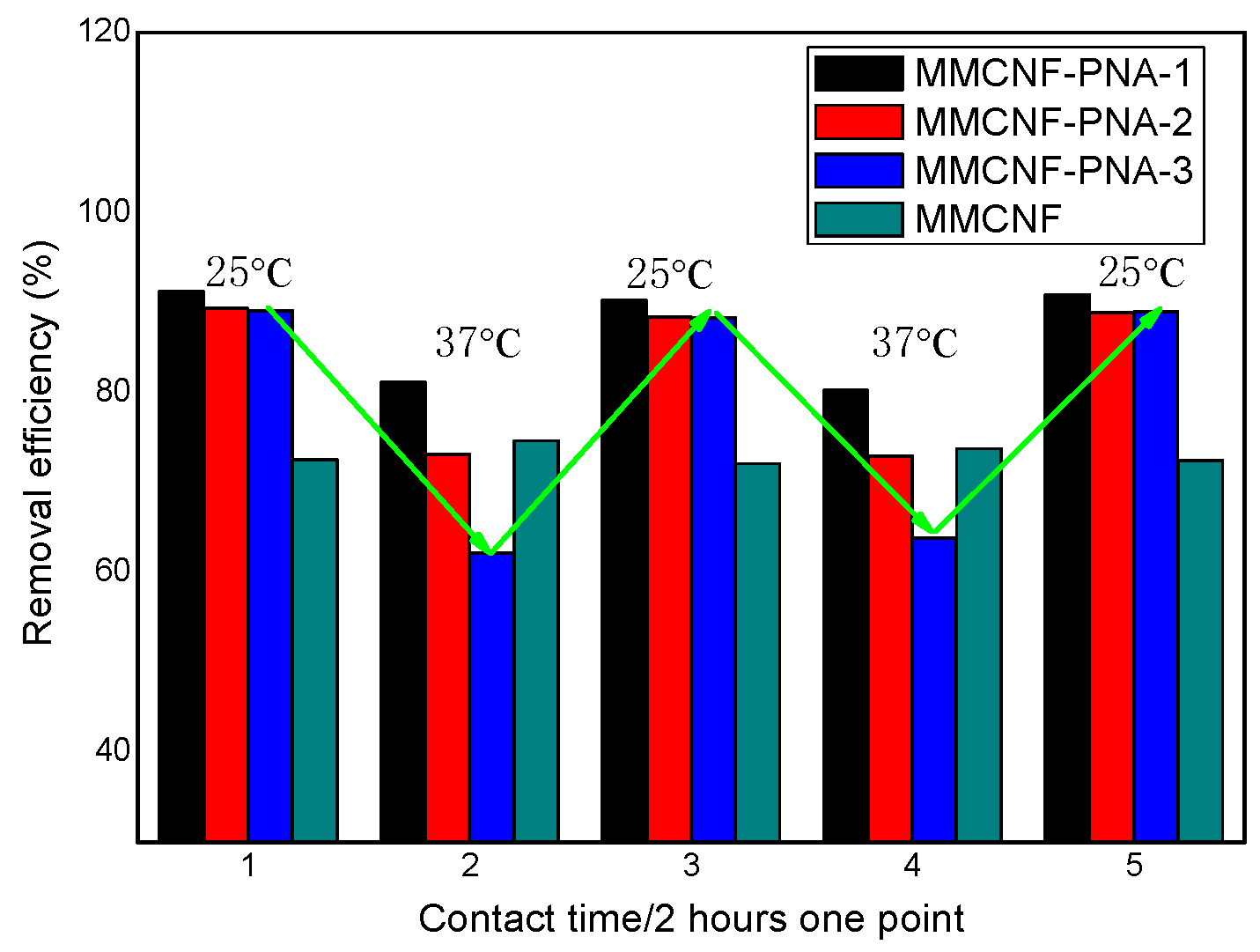

3.4. The Contact Time Effects on Adsorption

3.5. Adsorption Kinetic Models

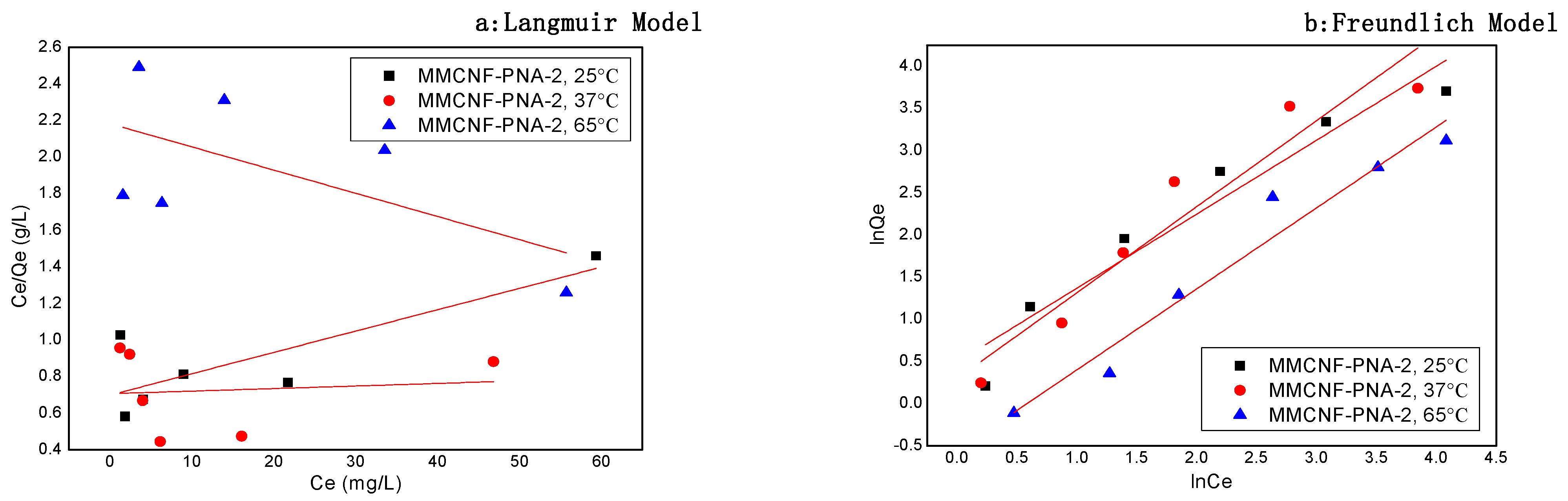

3.6. Adsorption Isotherms

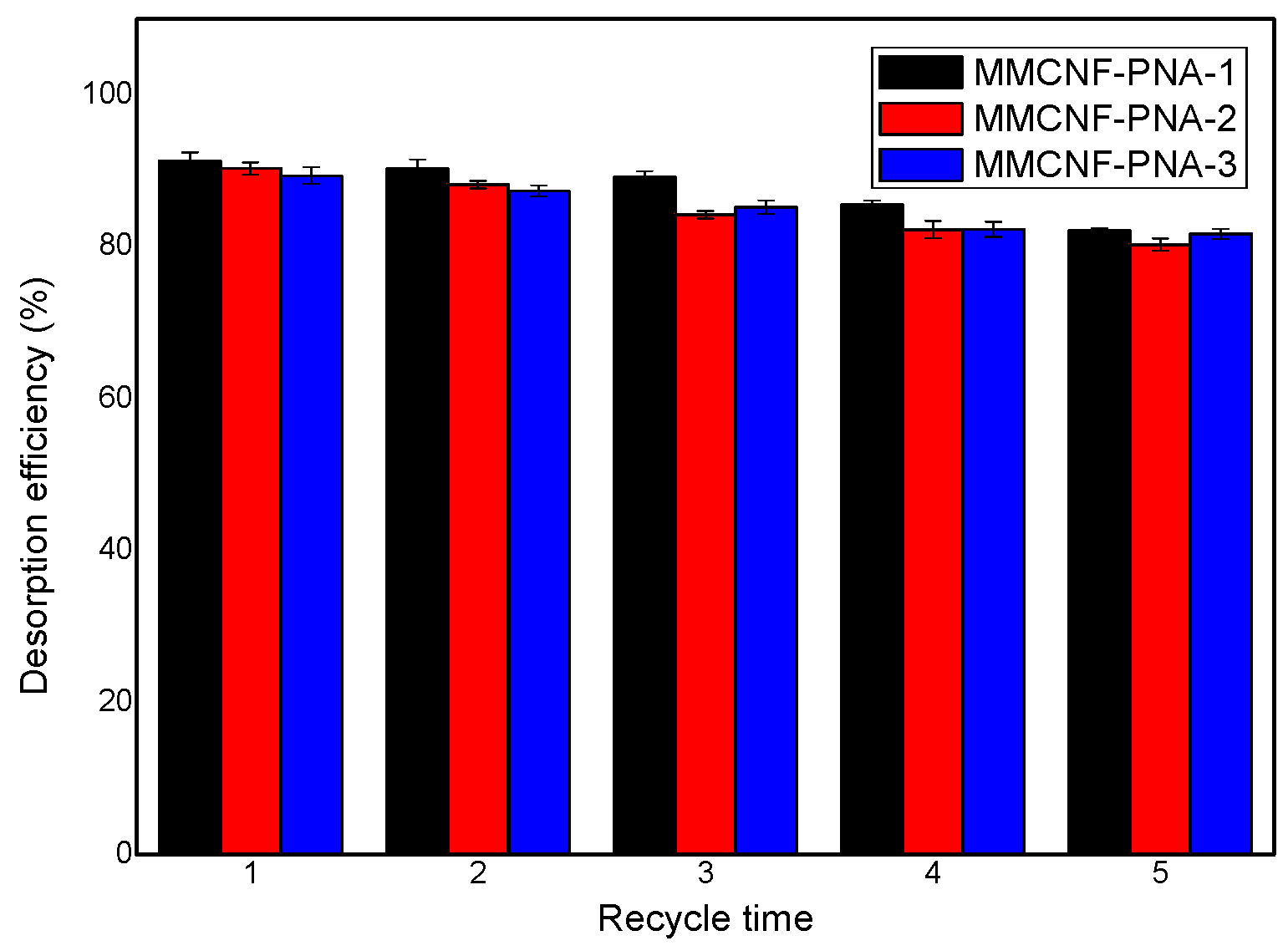

3.7. The Desorption and Recycling of Adsorbents

3.8. The Study of Thermal Responsive Behavior of the Adsorbents

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanna, H.; Bhatnagar, A.; Sillanpaa, M. A review on modification methods to cellulose-based adsorbents to improve adsorption capacity. Water Res. 2016, 91, 156–173. [Google Scholar]

- Debashish, R.; Semsarilar, M.; Guthrie, J.T.; Perrier, S. Cellulose modification by polymer grafting: A review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 7, 2046–2064. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, D.W.; Birkinshaw, C.; O’Dwyer, T.F. Heavy metal adsorbents prepared from the modification of cellulose: A review. Bioresource Technol. 2008, 99, 6709–6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colak, S.; Kusefoglu, S.H. Synthesis and Interfacial Properties of Aminosilane Derivative of Acrylated Epoxidized Soybean Oil. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 104, 2244–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Sain, M.; Oksman, K. Study of structural morphology of hemp fiber from the micro to the nanoscale. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2007, 14, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Liu, R.; Huang, Y. Graft modification of cellulose: Methods, properties and applications. Polymer 2015, 70, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, K.; Wang, B.; Kokufuta, E. Enzyme-regulated microgel collapse for controlled membrane permeability. Langmuir 2001, 17, 4704–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, R.; He, Z.; Ni, Y. Preparation and characterization of thermal/pH-sensitive hydrogel from carboxylated nanocrystalline cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Healy, K.E. Synthesis and Characterization of Injectable Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide-co-acrylic acid) Hydrogels with Proteolytically Degradable Cross-Links. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Zhang, H.; Ma, L.; Zhou, H.; Yu, Y.; Guo, T.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H. Green pH/magnetic sensitive hydrogels based on pineapple peel cellulose and polyvinyl alcohol: Synthesis, characterization and naringin prolonged release. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 209, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.L.; Gao, Q.Y. Preparation and properties of a pH/temperature-responsive carboxymethyl chitosan/poly [N-isopropylacrylamide] semi-IPN hydrogel for oral delivery of drugs. Carbohyd. Res. 2007, 342, 2416–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Jin, Y. Thermal and pH dual-responsive cellulose microfilament spheres for dye removal in single and binary systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 377, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Ma, H.; Pu, S.; Yan, C.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Wang, X.; Chu, W.; Anatoly, Z. Hybrid porous magnetic bentonite-chitosan beads for selective removal of radioactive cesium in water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 362, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ni, S.; Hou, X.; Hu, E. Study on cellulose microfilaments based composite spheres: Microwave-assisted synthesis, characterization, and application in pollutant removal. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 228, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.B.; Song, X.F.; Chen, D.S.; Qu, R.; Zhao, Y.Z. Self-Powered Multifunctional Organic Hydrogel Based on Poly(acrylic acid-N-isopropylacrylamide) for Flexible Sensing Devices. Langmuir 2023, 39, 6151–6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Yin, G.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xie, D. Biodegradable Nanofibrillated Cellulose/Poly-(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) Composite Film with Enhanced Barrier Properties for Food Packaging. Molecules 2023, 28, 2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekici, S. Intelligent poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)-carboxymethyl cellulose full interpenetrating polymeric networks for protein adsorption studies. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 2843–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yu, N.; Gao, Y.; Tao, Q.; Liu, X. Polymeric hollow spheres assembled from ALG-g-PNIPAM and β-cyclodextrin for controlled drug release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 82, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Song, Z.; Li, F.; Xie, D. Intelligent temperature-pH dual responsive nanocellulose hydrogels and the application of drug release towards 5-fluorouracil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 223, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Ali, O.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, T.; Liu, C.; Luo, S. Fast adsorption of heavy metal ions by waste cotton fabrics based double network hydrogel and influencing factors insight. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Bing, H.; Feifei, X.; Xiaofeng, C. Equilibrium and kinetic studies of methyl orange adsorption on multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 170, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, A.; Moniri, E.; Hassani, A.H.; Panahi, H.A.; Miralinaghi, M. Polymerization of graphene oxide with polystyrene: Non-linear isotherms and kinetics studies of anionic dyes. Microchem. J. 2019, 145, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, M.; Sakthi, V.; Rengaraj, S. Kinetics and equilibrium adsorption study of lead (II) onto activated carbon prepared from coconut shell. J. Colloid. Interf. Sci. 2004, 279, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.Y.; Wang, P.; Ma, Q.Y.; Wang, L.J. Preparation of a cellulose-based adsorbent with covalently attached hydroxypropyldodecyldimethylammonium groups for the removal of CI Reactive Blue 21 dye from aqueous solution. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 10604–10615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A. Novel cellulose derivative containing aminophenylacetic acid as sustainable adsorbent for removal of cationic and anionic dyes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, J.T.; Dlamini, M.L.; Nuapia, Y.; Etale, A. Synthesis and application of cationized cellulose for adsorption of anionic dyes. Mater. Today-Proc. 2022, 62, S133–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suteu, D.; Biliuta, G.; Rusu, L.; Coseri, S.; Vial, C.; Nica, I. A regenerable microporous adsorbent based on microcrystalline cellulose for organic pollutants adsorption. Desalin. Water Treat. 2019, 146, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Gao, M.; Chang, J.; Ma, H. Adsorption properties of crosslinking carboxymethyl cellulose grafting dimethyldiallylammonium chloride for cationic and anionic dyes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 151, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Gao, B.; Zhou, Y.; Qiao, H.; Gao, W.; Qu, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X. Facile preparation of 3D GO/CNCs composite with adsorption performance towards [BMIM][Cl] from aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 337, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.L.; Liu, W.J.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, H. Magnesium Oxide Embedded Nitrogen Self-Doped Biochar Composites: Fast and High-Efficiency Adsorption of Heavy Metals in an Aqueous Solution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 10081–10089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Repo, E.; Yin, D.; Meng, Y.; Jafari, S.; Sillanpää, M. EDTA-Cross-Linked β-Cyclodextrin: An Environmentally Friendly Bifunctional Adsorbent for Simultaneous Adsorption of Metals and Cationic Dyes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 10570–10580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | MMCNF (g) | NIPAM (g) | KPS (g) | MBA (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMCNF-PNA-1 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.015 |

| MMCNF-PNA-2 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| MMCNF-PNA-3 | 2 | 1.0 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| Sample | qe,exp. (mg g−1) | Pseudo-First Order | Pseudo-Second Order | Elovich Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | R2 | qe2,cal (mg g−1) | k2 (mg g−1 h−1) | R2 | α | β | R2 | ||

| MMCNF-PNA-1 (25) | 17.72 | 15.48 | 0.11 | 0.365 | 17.24 | 0.005 | 0.999 | 167.25 | 0.563 | 0.902 |

| MMCNF-PNA-2 (25) | 17.24 | 17.15 | 0.08 | 0.643 | 18.51 | 0.007 | 0.999 | 288.76 | 0.678 | 0.959 |

| MMCNF-PNA-3 (25) | 16.96 | 15.07 | 0.11 | 0.356 | 16.95 | 0.005 | 0.999 | 496.41 | 0.696 | 0.976 |

| MMCNF-PNA-1 (37) | 15.65 | 14.68 | 0.11 | 0.480 | 15.38 | 0.009 | 0.999 | 1217.9 | 0.809 | 0.924 |

| MMCNF-PNA-2 (37) | 14.32 | 12.91 | 0.20 | 0.727 | 12.99 | 0.116 | 0.999 | 3888.3 | 0.722 | 0.718 |

| MMCNF-PNA-3 (37) | 15.63 | 14.28 | 0.12 | 0.517 | 15.87 | 0.008 | 0.999 | 1819.3 | 0.864 | 0.948 |

| Samples | T (°C) | Freundlich Constants | Langmuir Constants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KF | n | R2 | Qmax | KL | R2 | ||

| MMCNF-PNA-2 | 25 | 1.634 | 1.140 | 0.919 | 8.57 | 0.017 | 0.611 |

| 37 | 1.342 | 0.980 | 0.905 | 714.28 | 0.002 | 0.118 | |

| 65 | 0.571 | 1.042 | 0.947 | 78.8 | 0.006 | 0.222 | |

| Materials Reported | Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) |

|---|---|

| Modified cellulose adsorbents [24] | CI Reactive Blue 21 dye: 200 |

| Cellulose derivative [25] | MB: 135 |

| MMCNF-PNA-2 (this work) | MB: 192 |

| Cationized cellulose [26] | Methyl orange (MO): 76.9 |

| Porous microcrystalline cellulose [27] | MB: 82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Preparation and Application of Responsive Nanocellulose Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111446

Zhou Y, Zhang L, Li Y. Preparation and Application of Responsive Nanocellulose Composites. Polymers. 2024; 16(11):1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111446

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Yanhui, Lu Zhang, and Yuan Li. 2024. "Preparation and Application of Responsive Nanocellulose Composites" Polymers 16, no. 11: 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111446

APA StyleZhou, Y., Zhang, L., & Li, Y. (2024). Preparation and Application of Responsive Nanocellulose Composites. Polymers, 16(11), 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111446