Graphene and Iron Reinforced Polymer Composite Electromagnetic Shielding Applications: A Review

Abstract

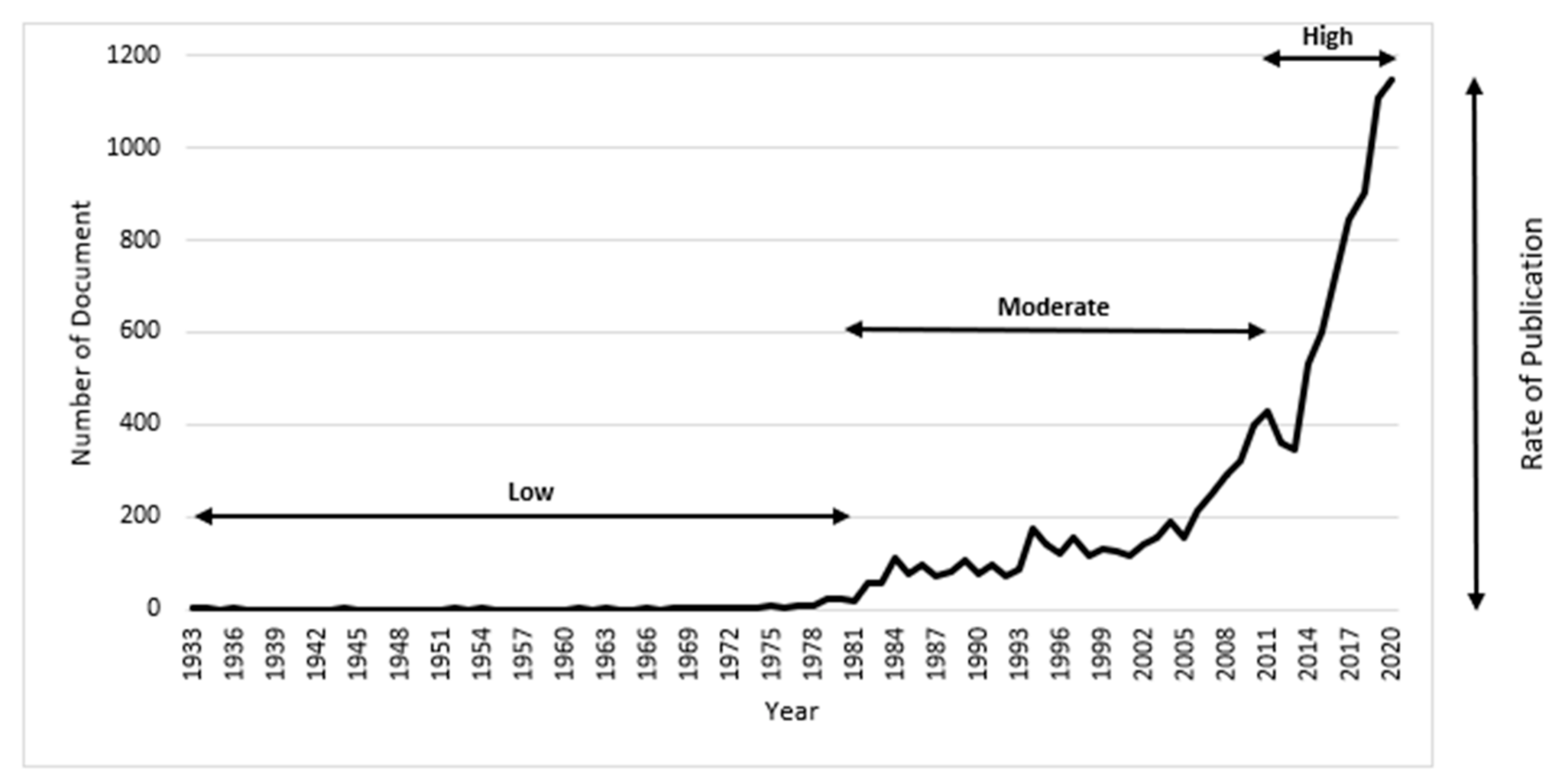

:1. Introduction

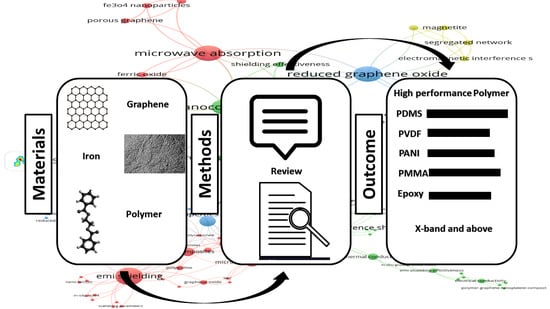

2. Scope of Review

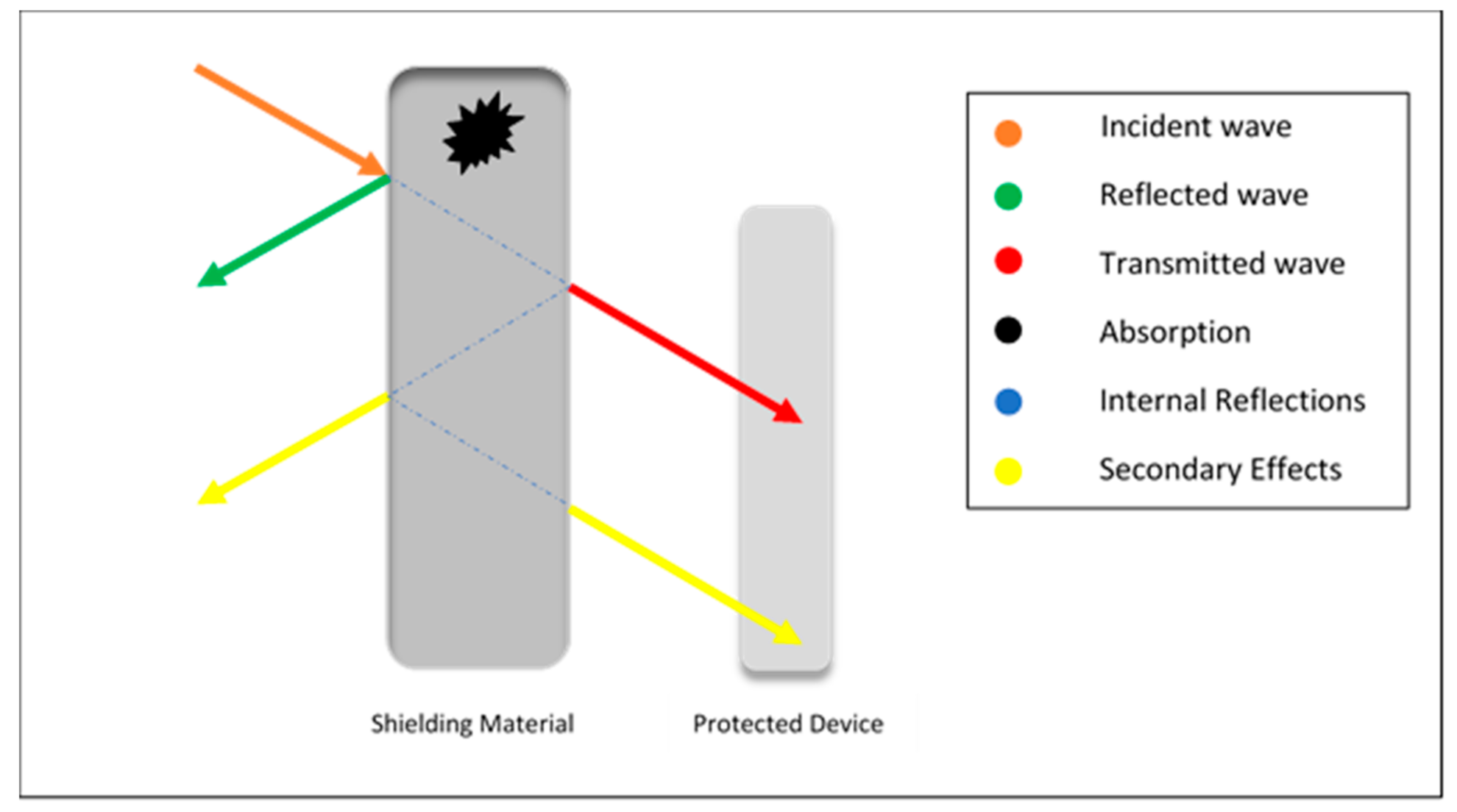

3. Electromagnetic Inferences Theory

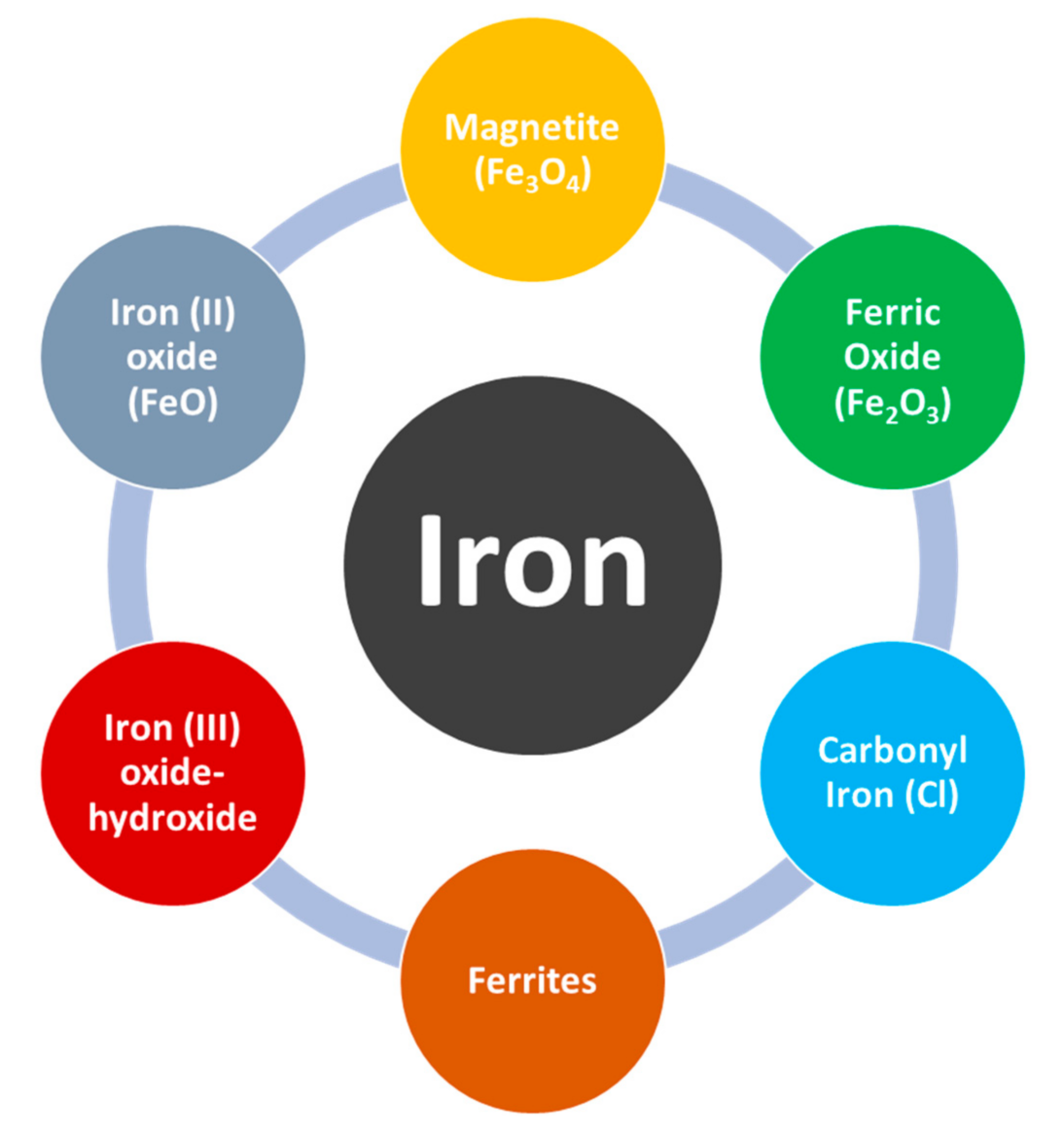

4. Graphene-Based Composites

4.1. Graphene@Iron Composites

4.1.1. Keywords Analysis of Graphene@Iron Composites Articles

4.1.2. Interpretation of Graphene@Iron Composites Articles

5. Polymer-Based Composites

5.1. Graphene@Iron@Polymer Composites

5.1.1. Keywords Analysis of Graphene@Iron@Polymer Composites Articles

5.1.2. Interpretation of Graphene@Iron@Polymer Based Composites Articles

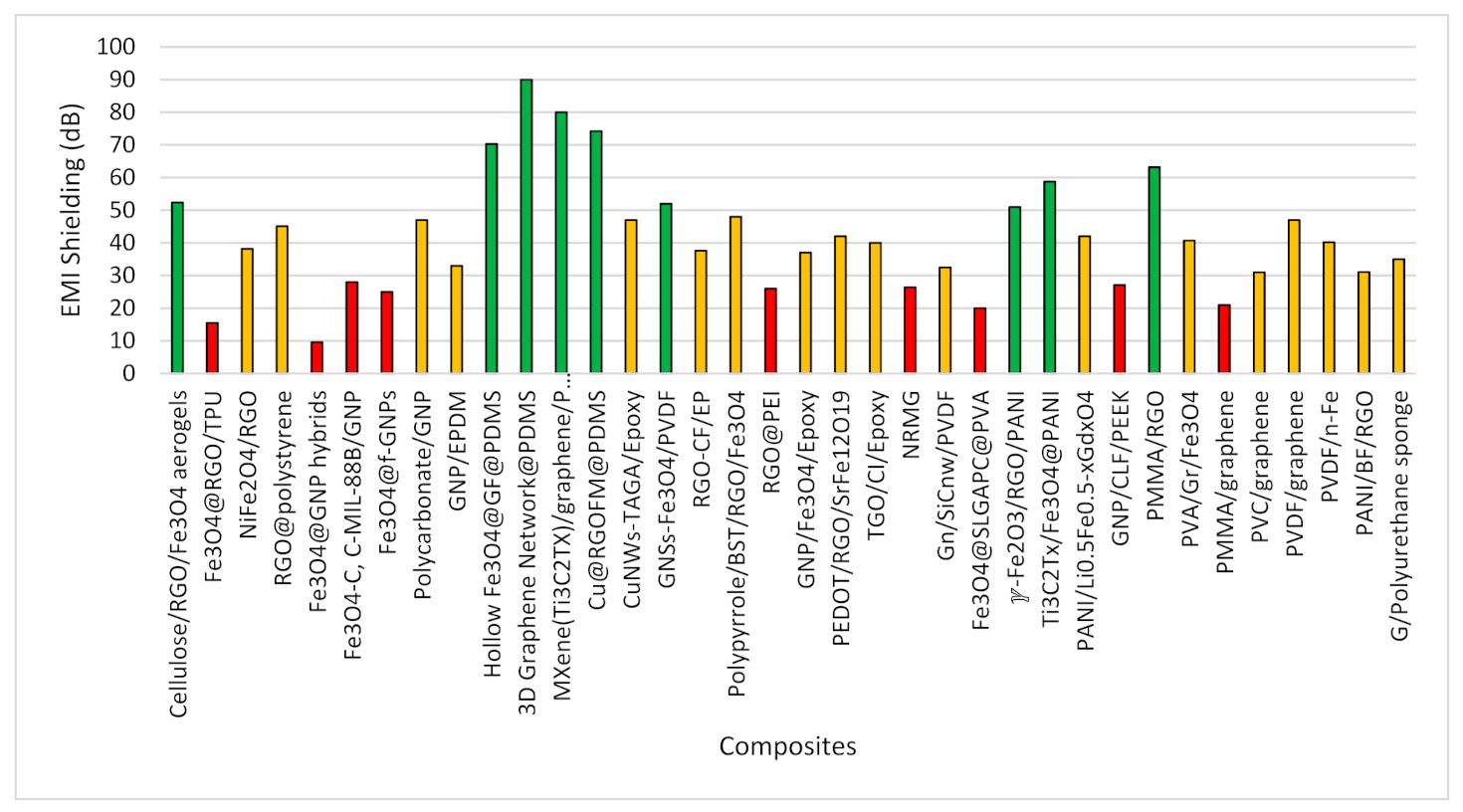

6. Discussion

7. Drawbacks and Future Direction

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bayat, M.; Yang, H.; Ko, F.; Michelson, D.; Mei, A. Electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of hybrid multifunctional Fe3O4/carbon nanofiber composite. Polymer 2014, 55, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qiu, H.; Liang, C.; Song, P.; Han, Y.; Han, Y.; Gu, J.; Kong, J.; Pan, D.; Guo, Z. Electromagnetic interference shielding MWCNT-Fe3O4@Ag/epoxy nanocomposites with satisfactory thermal conductivity and high thermal stability. Carbon 2019, 141, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajavel, K.; Luo, S.; Wan, Y.; Yu, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, P.; Sun, R.; Wong, C. 2D Ti3C2Tx MXene/polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) nanocomposites for attenuation of electromagnetic radiation with excellent heat dissipation. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 129, 105693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoli, A.; Corinaldesi, V.; Donnini, J.; Di Perna, C.; Micheli, D.; Vricella, A.; Pastore, R.; Bastianelli, L.; Moglie, F.; Primiani, V.M. Effect of graphene oxide and metallic fibers on the electromagnetic shielding effect of engineered cementitious composites. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 18, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Electromagnetic Fields; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.-J.; Li, X.-M.; Zhu, P.-L.; Sun, R.; Wong, C.-P.; Liao, W.-H. Lightweight, flexible MXene/polymer film with simultaneously excellent mechanical property and high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 130, 105764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjmand, M.; Apperley, T.; Okoniewski, M.; Sundararaj, U. Comparative study of electromagnetic interference shielding properties of injection molded versus compression molded multi-walled carbon nanotube/polystyrene composites. Carbon 2012, 50, 5126–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Kim, S.; Park, G.-K.; Lee, N. Influence of carbon fiber on the electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of high-performance fiber-reinforced cementitious composites. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 101982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, L. Electromagnetic Waves; Radio i Svyaz’: Moscow, Russia, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhao, K.; Gui, Y.; Fang, S.; Xu, Y.; Ma, Z. Effects of electromagnetic radiation on health and immune function of operators. (Zhonghua lao dong wei sheng zhi ye bing za zhi-Zhonghua laodong weisheng zhiyebing zazhi). Chin. J. Ind. Hyg. Occup. Dis. 2013, 31, 602–605. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Bai, G.; Huang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Du, F.; Li, F.; Guo, T.; Chen, Y. Reflection and absorption contributions to the electromagnetic interference shielding of single-walled carbon nanotube/polyurethane composites. Carbon 2007, 45, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Tai, N.-H. Carbon materials and their composites for electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness in X-band. Carbon 2019, 152, 159–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlbom, A.; Bridges, J.; De Seze, R.; Hillert, L.; Juutilainen, J.; Mattsson, M.-O.; Neubauer, G.; Schuz, J.; Simkó, M.; Bromen, K. Possible effects of Electromagnetic Fields (EMF) on Human Health—Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR). Toxicology 2008, 246, 248–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifra, M.; Fields, J.Z.; Farhadi, A. Electromagnetic cellular interactions. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2011, 105, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Brosseau, C. A review and analysis of microwave absorption in polymer composites filled with carbonaceous particles. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 061301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopus. Analyze Search Results. 2020. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/term/analyzer.uri?sid=c83fb551961d44de283ec501945564a9&origin=resultslist&src=s&s=TITLE-ABS-KEY%28%22electromagnetic+shielding%22+or+%22EMI+shielding%22+%29&sort=plf-f&sdt=b&sot=b&sl=62&count=10467&analyzeResults=Analyze+results&txGid=2fe27e3ca6c83eeb06e8625e54048d56 (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Ling, J. EMI shielding—conductive coatings—material selection. Trans. IMF 1987, 65, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, J.; Driver, R.; Roberts, R.; Horrigan, E. Electromagnetic shielding properties of yttrium barium cuprate superconductor. Cryogenics 1988, 28, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pienkowski, T.; Johnson, D.; Lanagan, M.; Poeppel, R.; Danyluk, S.; McGuire, M. Measuring the Shielding Effectiveness of Superconductive Composites. In Proceedings of the National Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility, Istanbul, Turkey, 11–16 May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, D.; Zheng, Q. Electronic properties of carbon fiber reinforced gypsum plaster. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1989, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Khastgir, D.; Chaki, T.; Chakraborty, A. Electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of carbon black and carbon fibre filled EVA and NR based composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2000, 31, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.-S.; Chi, Y.-S.; Kang, T.J.; Nam, S.-W. Electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of multifunctional metal composite fabrics. Text. Res. J. 2008, 78, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortlek, H.G.; Saracoglu, O.G.; Saritas, O.; Bilgin, S. Electromagnetic shielding characteristics of woven fabrics made of hybrid yarns containing metal wire. Fibers Polym. 2012, 13, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-J.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.-X. Preparation of electromagnetic shielding wood-metal composite by electroless nickel plating. J. For. Res. 2006, 17, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.B.; Ramakrishna, S.; Lee, M.L.; Ueng, T.H. Electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of stainless steel/polyester woven fabrics. Text. Res. J. 2001, 71, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.-J.; Yu, C.-X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Ge, K.-Y.; Zhou, M.L. Electroless metal plating of cenosphere and its electromagnetic shielding properties. J. Beijing Polytech. Univ. 2003, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ceptech. Understanding EMI/RFI Shielding to Manage Interference. 2020. Available online: https://ceptech.net/understanding-emi-rfi-shielding-to-manage-interference/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Ayub, S.; Guan, B.H.; Ahmad, F. Graphene and Iron Based Composites as EMI Shielding: A Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the 2020 Second International Sustainability and Resilience Conference: Technology and Innovation in Building Designs, Sakheer, Bahrain, 11–12 November 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, M.F.; Evans, A.; Fleck, N.A.; Gibson, L.J.; Hutchinson, J.W.; Wadley, H.N. Metal Foams: A Design Guide; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2000; ISBN 0-7506-7219-6. [Google Scholar]

- Banhart, J. Manufacture, characterisation and application of cellular metals and metal foams. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2001, 46, 559–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, V.; Fleck, N. Isotropic constitutive models for metallic foams. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2000, 48, 1253–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanssen, A.; Hopperstad, O.; Langseth, M.; Ilstad, H. Validation of constitutive models applicable to aluminium foams. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2002, 44, 359–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.J.; Ong, J.M. Characterization of close-celled cellular aluminum alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 2773–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Li, H.; He, B.; Dang, F.; Lin, J.; Fan, R.; Hou, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Y.; et al. Bio-gel derived nickel/carbon nanocomposites with enhanced microwave absorption. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 8812–8822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Liu, C.; Xu, D.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Shao, Q.; Guo, Z. Enhanced electromagnetic wave absorption of three-dimensional Porous Fe3O4/C Composite Flowers. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 12471–12480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, P.; Ostoja-Starzewski, M.; Jasiuk, I. Experimental and computational study of shielding effectiveness of polycarbonate carbon nanocomposites. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 120, 145103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomassin, J.-M.; Jérôme, C.; Pardoen, T.; Bailly, C.; Huynen, I.; Detrembleur, C. Polymer/carbon based composites as electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2013, 74, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, S.; Kumar, K.K.S.; Rao, C.R.K.; Vijayan, M.; Trivedi, D.C. EMI shielding: Methods and materials-A review. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 112, 2073–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Zhao, Y.; Ge, D. Research progress in electromagnetic shielding materials. Mater. Rev. 2008, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, J.; Lee, C.Y. High frequency electromagnetic interference shielding response of mixtures and multilayer films based on conducting polymers. J. Appl. Phys. 2000, 88, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Chung, D. Electromagnetic interference shielding using continuous carbon-fiber carbon-matrix and polymer-matrix composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 1999, 30, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.; Epstein, A.J. Electromagnetic radiation shielding by intrinsically conducting polymers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1994, 65, 2278–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gupta, M.C.; Dudley, K.L.; Lawrence, R.W. Conductive carbon nanofiber-polymer foam structures. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 1999–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-J.; Choi, H.-S.; Kim, E.-K. A comparative study of the shielding performance of uniforms using electromagnetic wave shielding materials currently on the market for workers at Korea Railroad Corporation. J. Korean Soc. Costume 2010, 60, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gowda, T.M.; Naidu, A.; Chhaya, R. Some mechanical properties of untreated jute fabric-reinforced polyester composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 1999, 30, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.G.; Louis, J.; Cheng, Q.; Bao, J.; Smithyman, J.; Liang, R.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Brooks, J.S.; Kramer, L.; et al. Electromagnetic interference shielding properties of carbon nanotube buckypaper composites. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 415702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.G.; Chung, C.H.; Lee, Y.-S. The effect of crystallization by heat treatment on electromagnetic interference shielding efficiency of carbon fibers. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2011, 22, 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saleh, M.H.; Sundararaj, U. Electromagnetic interference shielding mechanisms of CNT/polymer composites. Carbon 2009, 47, 1738–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanasinghe, D.; Aslani, F.; Ma, G.; Habibi, D. Review of polymer composites with diverse nanofillers for electromagnetic interference shielding. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steffan, P.; Stehlik, J.; Vrba, R. Composite Materials for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. In Natural Computing Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 245, pp. 649–652. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowska, A.; Janas, D.; Herman, A.; Jędrysiak, R.; Giżewski, T.; Boncel, S. From blackness to invisibility—Carbon nanotubes role in the attenuation of and shielding from radio waves for stealth technology. Carbon 2018, 126, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohini, R.; Bose, S. Electromagnetic wave suppressors derived from crosslinked polymer composites containing functional particles: Potential and key challenges. Nano Struct. Nano Objects 2017, 12, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaliovich, A. Cable Shielding for Electromagnetic Compatibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Song, H.; Liu, H.; Luo, C.; Ren, Y.; Ding, T.; Khan, M.A.; Young, D.P.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Polypyrrole-interface-functionalized nano-magnetite epoxy nanocomposites as electromagnetic wave absorbers with enhanced flame retardancy. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 5334–5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saville, P. Review of Radar Absorbing Materials; Defence Research and Development Atlantic Dartmouth: Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhu, H.; Zou, G. Preparation and study on radar absorbing materials of nickel-coated carbon fiber and flake graphite. J. Alloy. Compd. 2008, 461, 490–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, F.; Kargi, A. Electromagnetic waves and human health. Electromagn. Waves 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul, C.R. Introduction to Electromagnetic Compatibility, 2nd ed.; Wiley Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, D. Electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of carbon materials. Carbon 2001, 39, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, K.L. Electromagnetic Shielding; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, D.D.L. Materials for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2000, 9, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.B.; Plantz, V.C.; Brush, D.R. Shielding theory and practice. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 1988, 30, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregman, A. Morphology Control of Polymer Composites for Enhanced Microwave Absorption. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Qian, K.; Yu, K.; Zhou, H.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, Z. Controllable synthesis and microwave absorption properties of Fe3O4@f-GNPs nanocomposites. Compos. Commun. 2020, 20, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V. Review of electromagnetic interference shielding materials fabricated by iron ingredients. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 1640–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhang, X. Sandwich structures of graphene@Fe3O4@PANI decorated with TiO2 nanosheets for enhanced electromagnetic wave absorption properties. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016, 662, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhingardive, V.; Suwas, S.; Bose, S. New physical insights into the electromagnetic shielding efficiency in PVDF nanocomposites containing multiwall carbon nanotubes and magnetic nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 79463–79472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Shishkin, A.; Koppel, T.; Gupta, N. A review of porous lightweight composite materials for electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 149, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, H.; Antunes, M.; Velasco, J.I. Recent advances in carbon-based polymer nanocomposites for electromagnetic interference shielding. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 103, 319–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, S.; Deshmukh, K.; Ahamed, M.B.; Pasha, S.K. Recent advances in electromagnetic interference shielding properties of metal and carbon filler reinforced flexible polymer composites: A review. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 114, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zeng, S.; Liang, L.; Bai, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, R. Quick Heat Dissipation in Absorption-Dominated Microwave Shielding Properties of Flexible Poly(vinylidene fluoride)/Carbon Nanotube/Co Composite Films with Anisotropy-Shaped Co (Flowers or Chains). ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 40789–40799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ding, X.; Wang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zheng, K.; Chen, L.; Tian, X.; Zhang, X. Segregated double network enabled effective electromagnetic shielding composites with extraordinary electrical insulation and thermal conductivity. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 117, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Pan, L.; Yang, X.; Ruan, K.; Han, Y.; Kong, J.; Gu, J. Simultaneous improvement of thermal conductivities and electromagnetic interference shielding performances in polystyrene composites via constructing interconnection oriented networks based on electrospinning technology. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 124, 105484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graphene-Info. Graphene: Structure and Shape. 2018. Available online: https://www.graphene-info.com/graphene-structure-and-shape (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Tjaronge, M.W.; Musarat, M.A.; Law, K.; Alaloul, W.S.; Ayub, S. Effect of Graphene Oxide on Mechanical Properties of Rubberized Concrete: A Review. In Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 484–492. [Google Scholar]

- Graphene Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. cheaptubes.com. 2020. Available online: https://www.cheaptubes.com/graphene-synthesis-properties-and-applications/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- NanoWerk. Graphene Description. Available online: https://www.nanowerk.com/what_is_graphene.php (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Hsiao, S.-T.; Ma, C.-C.M.; Liao, W.-H.; Wang, Y.-S.; Li, S.-M.; Huang, Y.-C.; Yang, R.-B.; Liang, W.-F. Lightweight and flexible reduced graphene oxide/water-borne polyurethane composites with high electrical conductivity and excellent electromagnetic interference shielding performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 10667–10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnidakouong, J.R.N.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, H.; Park, Y.-B. Electromagnetic interference shielding behavior of hybrid carbon nanotube/exfoliated graphite nanoplatelet coated glass fiber composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2019, 248, 114403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arief, I.; Biswas, S.; Bose, S. FeCo-Anchored Reduced Graphene Oxide Framework-Based Soft Composites Containing Carbon Nanotubes as Highly Efficient Microwave Absorbers with Excellent Heat Dissipation Ability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 19202–19214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, W.; Luo, C.; Li, J. Design of hollow ZnFe2O4 microspheres@graphene decorated with TiO 2 nanosheets as a high-performance low frequency absorber. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 202, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mederos-Henry, F.; Mahin, J.; Pichon, B.P.; Dîrtu, M.M.; Garcia, Y.; Delcorte, A.; Bailly, C.; Huynen, I.; Hermans, S. Highly efficient wideband microwave absorbers based on zero-Valent Fe@γ-Fe2O3 and Fe/Co/Ni carbon-protected alloy nanoparticles supported on reduced graphene oxide. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Pötschke, P.; Pionteck, J.; Voit, B.; Qi, H. Multifunctional Cellulose/rGO/Fe3O4 composite aerogels for electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 22088–22098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, A.K.; Tomar, M.; Gupta, V.; Kumar, P.; Singh, K. Electromagnetic interference shielding performance of lightweight NiFe2O4/rGO nanocomposite in X- band frequency range. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 15473–15481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, J.; Singh, A.K.; Haldar, K.K.; Tomar, M.; Gupta, V.; Singh, K. CoFe2O4 nanoparticles decorated MoS2-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for improved microwave absorption and shielding performance. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 21881–21892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhaskaran, K.; Bheema, R.K.; Etika, K. The influence of Fe3O4@GNP hybrids on enhancing the EMI shielding effectiveness of epoxy composites in the X-band. Synth. Met. 2020, 265, 116374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Liang, M.; Chen, Y.; Zou, H. Sandwich-like magnetic graphene papers prepared with mof-derived fe3o4–c for absorption-dominated electromagnetic interference shielding. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, S.; Zhang, B.; Yu, M.; Zhao, W.; Liu, J. Fabrication of porous graphene-Fe3O4 hybrid composites with outstanding microwave absorption performance. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 95, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, K.H. Microwave absorption properties of graphene oxide capsulated carbonyl iron particles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 475, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, S.; Sun, D.; Liu, J.; Li, F. One-pot synthesis of Ag@Fe3O4/reduced graphene oxide composite with excellent electromagnetic absorption properties. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 4982–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jia, Z.; Feng, A.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Wu, G. In situ deposition of pitaya-like Fe3O4@C magnetic microspheres on reduced graphene oxide nanosheets for electromagnetic wave absorber. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 199, 108261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Shi, J.; Wu, J. Ellipsoidal Fe3O4 @ C nanoparticles decorated fluffy structured graphene nanocomposites and their enhanced microwave absorption properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 6785–6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Bian, X.-M.; Hou, Z.-L.; Wang, C.-Y.; Li, Z.S.; Hu, H.D.; Qi, X.; Zhang, X. Electromagnetic response of magnetic graphene hybrid fillers and their evolutionary behaviors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2015, 27, 2760–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, W.; Wang, J.; Feng, X.; Sun, X.; Li, H.; Tao, Y. One-step hydrothermal synthesis and enhanced microwave absorption properties of Ni0.5Co0.5Fe2O4/graphene composites in low frequency band. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 20896–20905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yue, J.; Tang, X.-Z. A highly flexible and porous graphene-based hybrid film with superior mechanical strength for effective electromagnetic interference shielding. Appl. Phys. A 2020, 126, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Zheng, J.; Yang, W.; Zhao, B.; Guo, X.; Zhang, R. Flexible PVDF/CNTs/Ni@CNTs composite films possessing excellent electromagnetic interference shielding and mechanical properties under heat treatment. Carbon 2019, 155, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Lu, L.; Xie, Y.; Wang, W.; Tang, Y.; Teh, K.S. An ultra-thin carbon-fabric/graphene/poly(vinylidene fluoride) film for enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 13587–13599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, A.; Boesl, B.; Agarwal, A. 3D graphene foam-reinforced polymer composites—A review. Carbon 2018, 135, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.-X.; Pang, H.; Li, B.; Vajtai, R.; Xu, L.; Ren, P.-G.; Wang, J.-H.; Li, Z.-M. Structured reduced graphene oxide/polymer composites for ultra-efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wu, K.; Fu, Q. Metal-level robust, folding endurance, and highly temperature-stable mxene-based film with engineered aramid nanofiber for extreme-condition electromagnetic interference shielding applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 26485–26495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Atif, R.; Vo, T.; Inam, F. Graphene nanoplatelets in epoxy system: Dispersion, reaggregation, and mechanical properties of nanocomposites. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, Y.; Yu, J.; Yu, L.; Alam, F.E.; Dai, W.; Li, C.; Jiang, N. Enhancing the thermal, electrical, and mechanical properties of silicone rubber by addition of graphene nanoplatelets. Mater. Des. 2015, 88, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.B.; Li, Z.W.; Liu, L.; Huang, R.; Abshinova, M.; Yang, Z.; Tang, C.B.; Tan, P.K.; Deng, C.R.; Matitsine, S. Recent progress in some composite materials and structures for specific electromagnetic applications. Int. Mater. Rev. 2013, 58, 203–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, M.; Saadeh, W.; Sundararaj, U. EMI shielding effectiveness of carbon based nanostructured polymeric materials: A comparative study. Carbon 2013, 60, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, N.; Chakrabarti, K.; De, A. Highly efficient electromagnetic interference shielding using graphite nanoplatelet/poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)–poly(styrenesulfonate) composites with enhanced thermal conductivity. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 43765–43771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Zhang, L.; Yin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, L. Dielectric and EMW absorbing properties of PDCs-SiBCN annealed at different temperatures. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 33, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, M.F.; Khan, A.N.; Khan, R.; Javed, S.; Tariq, A.; Azeem, M.; Riaz, A.; Shafqat, A.; Cheema, H.; Akram, M.A.; et al. EMI shielding properties of polymer blends with inclusion of graphene nano platelets. Results Phys. 2019, 14, 102365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasim, S. Polyaniline-Graphene nanoplatelet composite films with improved conductivity for high performance X-band microwave shielding applications. Results Phys. 2019, 12, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhao, J.; Xiao, J.; Lu, L.; Fan, H. Synthesis and characterization of TiO2/polyaniline/graphene oxide bouquet-like composites for enhanced microwave absorption performance. J. Alloy. Compd. 2017, 710, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Huang, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhao, Y. Magnetic graphene@PANI@porous TiO2 ternary composites for high-performance electromagnetic wave absorption. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 6362–6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, W.; Luo, C.; Li, J.; Wang, Q. 3D heterostructure of graphene@Fe3O4@WO3@PANI: Preparation and excellent microwave absorption performance. Synth. Met. 2017, 231, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, F.; Qin, Y.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, P. Fabrication of hierarchical graphene@Fe3O4@SiO2@polyaniline quaternary composite and its improved electrochemical performance. J. Alloy. Compd. 2015, 634, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lin, J.; Xiao, J.; Fan, H. Synthesis and electromagnetic, microwave absorbing properties of polyaniline/graphene oxide/Fe3O4 nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 19345–19352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Yip, M.; Tai, N. Electromagnetic interference shielding efficiency of polyaniline composites filled with graphene decorated with metallic nanoparticles. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2013, 80, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Sun, Y.; Qi, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Facile synthesis of Fe3O4/PANI rod/rGO nanocomposites with giant microwave absorption bandwidth. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 4819–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Luo, C.; Wang, Q. Fabrication and enhanced electromagnetic wave absorption properties of sandwich-like graphene@NiO@PANI decorated with Ag particles. Synth. Met. 2017, 229, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Pan, Z.; Zhao, B. Graphene-doped polyaniline nanocomposites as electromagnetic wave absorbing materials. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 10921–10928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Mishra, M.; Sambyal, P.; Gupta, B.K.; Singh, B.P.; Chandra, A.; Dhawan, S.K. Encapsulation of γ-Fe2O3decorated reduced graphene oxide in polyaniline core–shell tubes as an exceptional tracker for electromagnetic environmental pollution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 3581–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Xie, L.; Hou, X.; Fang, C. Flexible and lightweight Ti3C2Tx MXene/Fe3O4@PANI composite films for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 5747–5757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preeti, S.; Dhawan, S.; Singh, A.P.; Singh, K.; Ohlan, A. Nano-ferrite and reduced graphene oxide embedded in polyaniline matrix for EMI Shielding Applications. J. Basic Appl. Eng. Res. 2016, 3, 385–389. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, M.A.; Majid, K.; Farukh, M.; Dhawan, S.; Kotnala, R.; Shah, J. Electromagnetic attributes a dominant factor for the enhanced EMI shielding of PANI/Li0.5Fe2.5−Gd O4 core shell structured nanomaterial. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 5111–5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Lee, S.H.; Hong, S.M.; Koo, C.M. Segregated reduced graphene oxide polymer composite as a high performance electromagnetic interference shield. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2018, 44, 4707–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimbalkar, P.; Korde, A.; Goyal, R. Electromagnetic interference shielding of polycarbonate/GNP nanocomposites in X-band. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 206, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidinejad, M.; Zhao, B.; Zandieh, A.; Moghimian, N.; Filleter, T.; Park, C.B. Enhanced electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of polymer–graphene nanoplatelet composites fabricated via supercritical-fluid treatment and physical foaming. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 30752–30761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Bai, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, D.; Ma, K.; Meng, Q.; Liu, X. Flexible GnPs/EPDM with excellent thermal conductivity and electromagnetic interference shielding properties. Nano 2019, 14, 1950075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdrojek, M.; Bomba, J.; Łapińska, A.; Dużyńska, A.; Żerańska-Chudek, K.; Suszek, J.; Stobiński, L.; Taube, A.; Sypek, M.; Judek, J. Graphene-based plastic absorber for total sub-terahertz radiation shielding. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 13426–13431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, K.; Zhu, W.; Shen, J.; Rollinson, J.; Hella, M.; Lian, J. Copper-coated reduced graphene oxide fiber mesh-polymer composite films for electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 5565–5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Zhan, R.; Qiu, J.; Fan, J.; Dong, B.; Guo, Z. Multi-interfaced graphene aerogel/polydimethylsiloxane metacomposites with tunable electrical conductivity for enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 11748–11759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Guo, H.; Hu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Hsu, P.-C.; Bai, S.-L. In-situ grown hollow Fe3O4 onto graphene foam nanocomposites with high EMI shielding effectiveness and thermal conductivity. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 188, 107975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-T.; Min, B.K.; Yi, Y.; Kim, S.J.; Choi, C.-G. MXene(Ti3C2TX)/graphene/PDMS composites for multifunctional broadband electromagnetic interference shielding skins. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Alhabeb, M.; Hatter, C.B.; Anasori, B.; Hong, S.M.; Koo, C.M.; Gogotsi, Y. Electromagnetic interference shielding with 2D transition metal carbides (MXenes). Science 2016, 353, 1137–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liang, L.; Xu, P.; Wang, Y.; Shang, Y.; Ma, J.; Su, F.; Feng, Y.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C. Flexible polyvinylidene fluoride film with alternating oriented graphene/Ni nanochains for electromagnetic interference shielding and thermal management. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 395, 125209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Menon, A.V.; Bose, S. Graphene templated growth of copper sulphide ‘flowers’ can suppress electromagnetic interference. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 3292–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Ren, P.; Fu, B.; Ren, F.; Jin, Y.; Sun, Z. Multi-layered graphene-Fe3O4/poly (vinylidene fluoride) hybrid composite films for high-efficient electromagnetic shielding. Polym. Test. 2020, 89, 106652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Quan, H.; Huang, Z.; Luo, S.; Luo, X.; Deng, F.; Jiang, H.; Zeng, G. Electromagnetic and microwave absorbing properties of RGO@hematite core–shell nanostructure/PVDF composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2014, 102, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Hamidinejad, M.; Ma, L.; Wang, Z.; Park, C.B. Lightweight and flexible graphene/SiC-nanowires/ poly(vinylidene fluoride) composites for electromagnetic interference shielding and thermal management. Carbon 2020, 156, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabira, K.; Jayakrishnan, M.; Saheeda, P.; Jayalekshmi, S. On the absorption dominated EMI shielding effects in free standing and flexible films of poly(vinylidene fluoride)/graphene nanocomposite. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 99, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Ma, L.; Zhao, B.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Lei, Y.; Park, C.B. An effective design strategy for the sandwich structure of PVDF/GNP-Ni-CNT composites with remarkable electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 36568–36577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargama, H.; Thakur, A.; Chaturvedi, S.K. Polyvinylidene fluoride/nanocrystalline iron composite materials for EMI shielding and absorption applications. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016, 654, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, R.; Das, A.K.; Maitra, A.; Paria, S.; Karan, S.K.; Khatua, B.B. Salt leached viable porous Fe3O4 decorated polyaniline—SWCNH/PVDF composite spectacles as an admirable electromagnetic shielding efficiency in extended Ku-band region. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 129, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, W. Effect of electrophoretic condition on the electromagnetic interference shielding performance of reduced graphene oxide-carbon fiber/epoxy resin composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 105, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liang, C.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, F.; Wen, F.; Xu, B.; Wang, B. Novel 3D network porous graphene nanoplatelets /Fe3O4/epoxy nanocomposites with enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding efficiency. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 169, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vovchenko, L.L.; Lozitsky, O.V.; Oliynyk, V.V.; Zagorodnii, V.V.; Len, T.A.; Matzui, L.Y.; Milovanov, Y.S. Dielectric and microwave shielding properties of three-phase composites graphite nanoplatelets/carbonyl iron/epoxy resin. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 4781–4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.-B.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zheng, W.-G.; Yu, Z.-Z. Magnetic and electrically conductive epoxy/graphene/carbonyl iron nanocomposites for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2015, 118, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ye, Z.; Ge, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z. Modified carbon fiber/magnetic graphene/epoxy composites with synergistic effect for electromagnetic interference shielding over broad frequency band. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 506, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R.; Agarwal, K.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, R.; Mukhopadhyay, K.; Prasad, N.E. EMI and microwave absorbing efficiency of polyaniline-functionalized reduced graphene oxide/γ-Fe2O3/epoxy nanocomposite. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 6643–6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolvanen, J.; Hannu, J.; Hietala, M.; Kordas, K.; Jantunen, H. Biodegradable multiphase poly(lactic acid)/biochar/graphite composites for electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 181, 107704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambyal, P.; Dhawan, S.; Gairola, P.; Chauhan, S.S.; Gairola, S. Synergistic effect of polypyrrole/BST/RGO/Fe 3 O 4 composite for enhanced microwave absorption and EMI shielding in X-Band. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2018, 18, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawai, P.; Chattopadhaya, P.; Banerjee, S. Synthesized reduce Graphene Oxide (rGO) filled Polyetherimide based nanocomposites for EMI Shielding applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 9989–9999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.Y.; Kim, Y.C.; Wang, M.; Nam, J.-D.; Suhr, J. Anisotropic electromagnetic interference shielding properties of polymer-based composites with magnetically-responsive aligned Fe3O4 decorated reduced graphene oxide. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 127, 109595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Ji, X.; Li, B.; Luo, Y. A self-assembled graphene/polyurethane sponge for excellent electromagnetic interference shielding performance. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 25829–25835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bansala, T.; Joshi, M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Doong, R.-A.; Chaudhary, M. Electrically conducting graphene-based polyurethane nanocomposites for microwave shielding applications in the Ku band. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 1546–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, K.; Shakir, M.F.; Afzal, A.; Rehan, Z.A.; Nawab, Y. Effect of Barium Hexaferrites and Thermally Reduced Graphene Oxide on EMI Shielding Properties in Polymer Composites. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2021, 34, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, J.; Lather, S.; Gupta, A.; Tripathi, R.; Maan, A.S.; Singh, K.; Ohlan, A. Reduced Graphene Oxide Functionalized Strontium Ferrite in Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) Conducting Network: A High-Performance EMI Shielding Material. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1900023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, J.; Lather, S.; Gupta, A.; Dahiya, S.; Maan, A.; Singh, K.; Dhawan, S.; Ohlan, A. EMI shielding properties of laminated graphene and PbTiO3 reinforced poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 165, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shu, J.-C.; He, X.-M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.-X.; Gao, C.; Yuan, J.; Cao, M.-S. Green approach to conductive PEDOT:PSS decorating magnetic-graphene to recover conductivity for highly efficient absorption. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 14017–14025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V. Role of spin disorder in magnetic and EMI shielding properties of Fe3O4/C/PPy core/shell composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 55, 2826–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, W.; Luo, C.; Li, J. Synthesis of ferromagnetic sandwich FeCo@graphene@PPy and enhanced electromagnetic wave absorption properties. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 443, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wei, C. Conducting polymers-NiFe2O4 coated on reduced graphene oxide sheets as electromagnetic (EM) wave absorption materials. Synth. Met. 2016, 221, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Su, X.; Li, X.; Yao, Z.; Yu, T.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Lu, J.; Ding, J. Multimaterial 3D-printing of graphene/Li0.35Zn0.3Fe2.35O4 and graphene/carbonyl iron composites with superior microwave absorption properties and adjustable bandwidth. Carbon 2020, 167, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, F.; Arjmand, M.; Moud, A.A.; Sundararaj, U.; Roberts, E.P.L. Segregated Hybrid poly(methyl methacrylate)/graphene/magnetite nanocomposites for electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 14171–14179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Koroth, A.K.; John, D.A.; Sidpara, A.M.; Paul, J. Highly filled multilayer thermoplastic/graphene conducting composite structures with high strength and thermal stability for electromagnetic interference shielding applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.V.B.; Yadav, P.; Aepuru, R.; Panda, H.S.; Ogale, S.; Kale, S. Single-layer graphene-assembled 3D porous carbon composites with PVA and Fe3O4 nano-fillers: An interface-mediated superior dielectric and EMI shielding performance. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 18353–18363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodiri, A.A.; Al-Ashry, M.Y.; El-Shamy, A.G. Novel hybrid nanocomposites based on polyvinyl alcohol/graphene/magnetite nanoparticles for high electromagnetic shielding performance. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 847, 156430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, W.; Nie, J.; Liu, D.; Sui, G. Synergistic effect of graphene nanoplate and carbonized loofah fiber on the electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of PEEK-based composites. Carbon 2019, 143, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.S.; Kuřitka, I.; Vilčáková, J.; Machovský, M.; Škoda, D.; Urbánek, M.; Masař, M.; Gořalik, M.; Kalina, L.; Havlica, J. Polypropylene nanocomposite filled with spinel ferrite NiFe2O4 nanoparticles and in-situ thermally-reduced graphene oxide for electromagnetic interference shielding application. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| S. No | Material | Thickness | Loading | Methods | Frequency | Shielding Effectiveness | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ZnFe2O4@graphene@TiO2 | 2.5 mm | - | Hydrothermal method | 3.8 GHz | −55 dB | 2017 | [81] |

| 2 | Cellulose/reduced graphene oxide (RGO)/Fe3O4 aerogels | 0.5 mm | 3 wt.% | Scalable method | 8–12 GHz | 49.4 dB | 2020 | [83] |

| 2 mm | 8 wt.% | 52.4 dB | ||||||

| 3 | NiFe2O4/RGO | 2 mm | - | Solvothermal method | 10.8 GHz | 38.2 dB | 2020 | [84] |

| 4 | MoS₂-RGO/CoFe₂O₄ | 1.4 mm | - | Hydrothermal method | 8–12 GHz | 19.26 dB | 2019 | [85] |

| 5 | Fe3O4@GNP hybrids | 1 mm | - | 1. Co-precipitation technique 2. Solvent-less approach | 8–12 GHz | 9.6 dB | 2020 | [86] |

| 6 | Fe3O4-C, C-MIL-88B/GNP | 0.11 mm | - | Filtration-assisted self-assembly method | 8–12 GHz | 28 dB | 2019 | [87] |

| 7 | Fe3O4@f-GNPs | 2 mm | - | Solvothermal method | 12 GHz | 25 dB | 2020 | [64] |

| 8 | PG-Fe3O4 | 6.1 mm | - | In-situ growth | 5.4 GHz | −53 dB | 2017 | [88] |

| 9 | GO@CIP | 1.9 mm | - | Wet stirring process | 0–18 GHz | −56.4 dB | 2019 | [89] |

| 10 | Ag@Fe3O4@RGO | 2 mm | - | Solvothermal method | 2–18 GHz | −40.05 dB | 2015 | [90] |

| 11 | Fe3O4@C/RGO | 3.57 mm | - | Solvothermal method | 2–18 GHz | −59.23 dB | 2020 | [91] |

| 12 | NRMG | 1.6 mm | - | Self-assembly method | 8–12 GHz | 26.4 dB | 2018 | [92] |

| 13 | Fe3O4@C@Graphene | 1.5 mm | - | Hydrothermal method | 2–18 GHz | −55.02 dB | 2018 | [92] |

| 14 | G-F | 1.9 mm | - | Hydrothermal method | 2–18 GHz | 20 dB | 2016 | [93] |

| 15 | Ni0.5Co0.5Fe2O4/graphene | 4 mm | - | Hydrothermal method | 0.58–1.19 GHz | −30.92 dB | 2018 | [94] |

| 16 | RGO/CNF@Ag-Fe3O4 | 0.11 mm | - | Vacuum-assisted filtration method | 8–12 GHz | 21 dB | 2020 | [95] |

| S. No | Material | Thickness | Loading | Methods | Frequency | Shielding Effectiveness | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PVC/PANI/GNP | - | 5 wt.% | Solution processing method | 18–20 GHz | 51 dB | 2019 | [107] |

| 2 | GNP@PANI | 1.5 mm | - | In-situ growth | 12 GHz | −14.5 dB | 2019 | [108] |

| 3 | TiO2/PANI/GO | 3.12 mm | - | In-situ growth | 2–18 GHz | −51.7 dB | 2017 | [109] |

| 4 | Graphene@PANI@TiO2 | 1.5 mm | - | 1. In-situ growth 2. Hydrothermal method | 2–18 GHz | −45.4 dB | 2016 | [110] |

| 5 | Graphene@Fe3O4@PANI@WO3 | 4 mm | - | 1. Hydrothermal method 2. Chemical oxidation polymerization | 9.4 GHz | −46.7 dB | 2017 | [111] |

| 6 | Graphene@Fe3O4@SiO2@polyaniline | 2.5 mm | - | Dilute polymerization | 12.5 GHz | −40.7 dB | 2015 | [112] |

| 7 | PANI/GO/Fe3O4 | 3.91 mm | - | Hummers method | 2–18 GHz | −53.5 dB | 2015 | [113] |

| 8 | Ag@Graphene/PANI | - | 5 wt.% | In-situ growth | 0.4–1.6 GHz | 29.33 dB | 2013 | [114] |

| 9 | Fe3O4/PANI rod/RGO | 3.5 mm | - | Facile method | 2–18 GHz | −33.3 dB | 2019 | [115] |

| 10 | Graphene@NiO@PANI@Ag | 3.5 mm | - | 1. Hydrothermal method 2. In-situ growth | 2–18 GHz | −37.5 dB | 2017 | [116] |

| 11 | G-PANI | 1.5 mm | - | In-situ growth | 2–18 GHz | 32.5 dB | 2017 | [117] |

| 12 | ℽ-Fe2O3/RGO/PANI | 2.5 mm | - | 1. Chemical oxidation polymerization 2. In-situ growth | 8–12 GHz | 51 dB | 2014 | [118] |

| 13 | Ti3C2Tx/Fe3O4@PANI | 12.1 µm | - | Co-precipitation method | 8–12 GHz | 58.8 dB | 2020 | [119] |

| 14 | PANI/BF/RGO | - | - | Citrate precursor method | 8–12 GHz | 31.1 dB | 2016 | [120] |

| 15 | PANI/Li0.5Fe0.5-xGdxO4 | 2 mm | - | In-situ growth | 8–12 GHz | 42 dB | 2019 | [121] |

| 16 | RGO@polystyrene | - | 3.47 vol% | High-pressure solid-phase compression moulding | 8–12 GHz | 45.1 dB | 2015 | [99] |

| 17 | Segregated RGO/PS | 2 mm | 10 wt.% | Hot compressed method | 0–20 GHz | 29.7 dB | 2018 | [122] |

| Conventional RGO/PS | 14.2 dB | |||||||

| 18 | Polycarbonate/GNP | 1 mm | - | Facile solution method | 8–12 GHz | 35 dB | 2018 | [123] |

| 2 mm | - | 47 dB | ||||||

| 19 | Polyethylene@GNP | - | 15.6 vol% | Injection moulding process | 18 and 26.5 GHz | 16 dB | 2018 | [124] |

| 19 vol% | 31.6 dB | |||||||

| 3 wt.% | 12 dB | |||||||

| 10 wt.% | 31 dB | |||||||

| 20 | GNP/EPDM | 0.3 mm | 8 wt.% | Ultrasonication technique | 8–12 GHz | 33 dB | 2019 | [125] |

| 12.4–18 GHz | 35 dB | |||||||

| 21 | Hollow Fe3O4@GF@PDMS | - | 4 wt.% | Solvothermal method | 8–12 GHz | 45 dB | 2020 | [129] |

| 8 wt.% | 65 dB | |||||||

| 12 wt.% | 70.3 dB | |||||||

| 22 | 3D Graphene Network@PDMS | 0.25 mm | 1.2 wt.% | Chemical vapor deposition | 8–12 GHz | 40 dB | 2020 | [129] |

| 0.75 mm | 90 dB | |||||||

| 23 | MXene(Ti3C2TX)/graphene/PDMS | 1 mm | - | Chemical vapor deposition | 8–12 GHz | 80 dB | 2020 | [130] |

| 26.5–40 GHz | 77 dB | |||||||

| 24 | Graphene flakes@PDMS | - | 0.1 wt.% | Mechanical mixing | 0.6 THz | 6.5 dB | 2018 | [126] |

| 3 wt.% | 12 dB | |||||||

| 10 wt.% | 31 dB | |||||||

| 25 | Cu@RGOFM@PDMS | 0.5 mm | - | Hummers method | 8–12 GHz | 74.2 dB | 2020 | [127] |

| 26 | GA/PDMS | 2.5 mm | - | 1. Ultrasonication technique 2. Hydrothermal method | 2–18 GHz | 60 dB | 2020 | [128] |

| 27 | Ni@GNS@PVDF | 0.5 mm | - | Ultrasonication technique | 18–26 GHz | 43.3 dB | 2020 | [132] |

| 0.7 mm | 51.4 dB | |||||||

| 28 | RGO@CuS@PVDF | 1 mm | - | Hydrothermal method | 12–18 GHz | −25 dB | 2020 | [133] |

| 29 | GNSs-Fe3O4/PVDF | 0.3 mm | - | Facile layer-by-layer coating | 8–12 GHz | 52 dB | 2020 | [134] |

| 30 | RGO@Hematite/PVDF | - | 5 wt.% | In-situ growth | 2–18 GHz | −43.97 dB | 2014 | [135] |

| 31 | Gn/SiCnw/PVDF | 1.2 mm | - | 1. Electrostatic assembly 2. Solution casting method | 8–12 GHz | 32.5 dB | 2020 | [136] |

| 32 | PVDF/graphene | 20 µm | 15 wt.% | Solution casting method | 8–12 GHz | 47 dB | 2018 | [137] |

| 33 | PVDF/GNP-Ni-CNT | 0.6 mm | - | Solvent casting method | 12–18 GHz | 46.4 dB | 2020 | [138] |

| 34 | PVDF/n-Fe | 1.93 mm | - | Hot-moulding process | 12–18 GHz | 40.21 dB | 2016 | [139] |

| 35 | PVDF/PFC | 2 mm | 1 wt.% | Solution blending process | 12–18 GHz | −29.7 dB | 2017 | [140] |

| 36 | CuNWs-TAGA/Epoxy | - | 7.2 wt.% | Thermal annealing method | 8–12 GHz | 47 dB | 2020 | [132] |

| 37 | RGO-CF/EP | 3–5 mm | - | 1. Electrophoretic deposition 2. Chemical reduction | 8–12 GHz | 37.6 dB | 2016 | [141] |

| 38 | GNP/Fe3O4/Epoxy | - | 7 wt.% | Co-precipitation method | 8–12 GHz | 37.03 dB | 2019 | [142] |

| 39 | GNP/Fe/Epoxy | 5 mm | 5 wt.% | Sonication method | 1–65 GHz | −78 dB | 2020 | [143] |

| 40 | TGO/CI/Epoxy | 4 mm | - | Centrifugal mixing method | 8–12 GHz | 40 dB | 2015 | [144] |

| 41 | GCF/MG3/EP | - | 0.5 wt.%, 9 wt.% | Hummers Method | 18–26 GHz | 51.1 dB | 2017 | [145] |

| 42 | RGO/PF/Epoxy | 3 mm | 60 wt.% | Solution mixing method | 2–18 GHz | −10.26 dB | 2020 | [146] |

| 43 | Polylactic acid/Biochar/Graphite | 0.25 mm | - | Hot-pressing method | 18–26.5 GHz | 30 dB | 2019 | [147] |

| 44 | Polypyrrole/BST/RGO/Fe3O4 | 22.8 × 10.03 × 2.5 mm | - | Chemical oxidative polymerization | 8–12 GHz | 48 dB | 2018 | [148] |

| 45 | RGO@PEI | - | 2.5 wt.% | Hummers Method | 8–12 GHz | 26 dB | 2018 | [149] |

| 46 | Fe3O4@RGO/TPU | 1 mm | - | Solution casting method | 8–12 GHz | ~15.51 ± 1.6 dB | 2020 | [150] |

| 47 | G/Polyurethane sponge | 9 mm | 18.7 wt.% | Hydrothermal method | 8–12 GHz | 35 dB | 2019 | [151] |

| 48 | TPU/TRG | 2 mm | 5.5 vol% | Solution blending method | 12–18 GHz | 32 dB | 2017 | [152] |

| 49 | BaFe@TRGO@TPU | 0.25 mm | - | Solution casting method | 0.1–20 GHz | −61 dB | 2020 | [153] |

| 50 | PEDOT/RGO/SrFe12O19 | 2.5 mm | - | In-situ growth | 8–12 GHz | 42.29 dB | 2019 | [154] |

| 4.66 mm | 62 dB | |||||||

| 51 | PEDOT/RGO/PbTiO3 | 2.5 mm | - | Chemical oxidative polymerization | 12.4–18 GHz | 51.94 dB | 2018 | [155] |

| 52 | PEDOT:PSS-Fe3O4-RGO | 3.86 mm | - | Hydrothermal method | 2–18 GHz | −61.4 dB | 2018 | [156] |

| 53 | Fe3O4/C:PPy | 0.8 mm | 2.8 wt.% | 1. Hydrothermal method 2. Chemical oxidative polymerization | 2–8 GHz | >28 dB | 2019 | [157] |

| 54 | FeCo@RGO@PPy | 2.5 mm | - | 1. Hydrothermal method 2. In-situ growth | 2–18 GHz | −40.7 dB | 2017 | [158] |

| 55 | RGO-PANI-NiFe2O4 | 2.4 mm | - | 1. Hummers method 2. Solvothermal method | 2–18 GHz | −49.7 dB | 2016 | [159] |

| RGO-PPy-NiFe2O4 | 1.7 mm | −44.8 dB | ||||||

| RGO-PEDOT-NiFe2O4 | 2 mm | −45.4 dB | ||||||

| 56 | Graphene/Li0.35Zn0.3Fe0.35O4/PMMA | 4 mm | - | 3D printing method | 2–18 GHz | −46.1 dB | 2020 | [160] |

| 57 | PMMA/RGO | 2.9 mm | 2.6 vol% | Self-assembly technique | 8–12 GHz | 63.2 dB | 2017 | [161] |

| 58 | PMMA/graphene | 2 mm | 20 wt.% | Hot compression method | 8–12 GHz | 21 dB | 2019 | [162] |

| PVC/graphene | 31 dB | |||||||

| 59 | Fe3O4@SLGAPC@PVA | 0.3 mm | - | Solution casting method | 8–12 GHz | 20 dB | 2015 | [163] |

| 60 | PVA/Gr/Fe3O4 | 0.2 mm | 0.08 wt.% | Hummers method | 8–12 GHz | 40.7 dB | 2020 | [164] |

| 61 | GNP/CLF/PEEK | - | 9 wt.% | Compression moulding method | 8–12 GHz | 27.1 dB | 2019 | [165] |

| 62 | NiFe2O4-RGO-Polypropylene | 2 mm | 5 wt.% | 1. Hummers method 2. Hot press method | 6–8 GHz | 29.4 dB | 2019 | [166] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ayub, S.; Guan, B.H.; Ahmad, F.; Oluwatobi, Y.A.; Nisa, Z.U.; Javed, M.F.; Mosavi, A. Graphene and Iron Reinforced Polymer Composite Electromagnetic Shielding Applications: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13152580

Ayub S, Guan BH, Ahmad F, Oluwatobi YA, Nisa ZU, Javed MF, Mosavi A. Graphene and Iron Reinforced Polymer Composite Electromagnetic Shielding Applications: A Review. Polymers. 2021; 13(15):2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13152580

Chicago/Turabian StyleAyub, Saba, Beh Hoe Guan, Faiz Ahmad, Yusuff Afeez Oluwatobi, Zaib Un Nisa, Muhammad Faisal Javed, and Amir Mosavi. 2021. "Graphene and Iron Reinforced Polymer Composite Electromagnetic Shielding Applications: A Review" Polymers 13, no. 15: 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13152580

APA StyleAyub, S., Guan, B. H., Ahmad, F., Oluwatobi, Y. A., Nisa, Z. U., Javed, M. F., & Mosavi, A. (2021). Graphene and Iron Reinforced Polymer Composite Electromagnetic Shielding Applications: A Review. Polymers, 13(15), 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13152580