The Effect of Nanofillers on the Functional Properties of Biopolymer-Based Films: A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

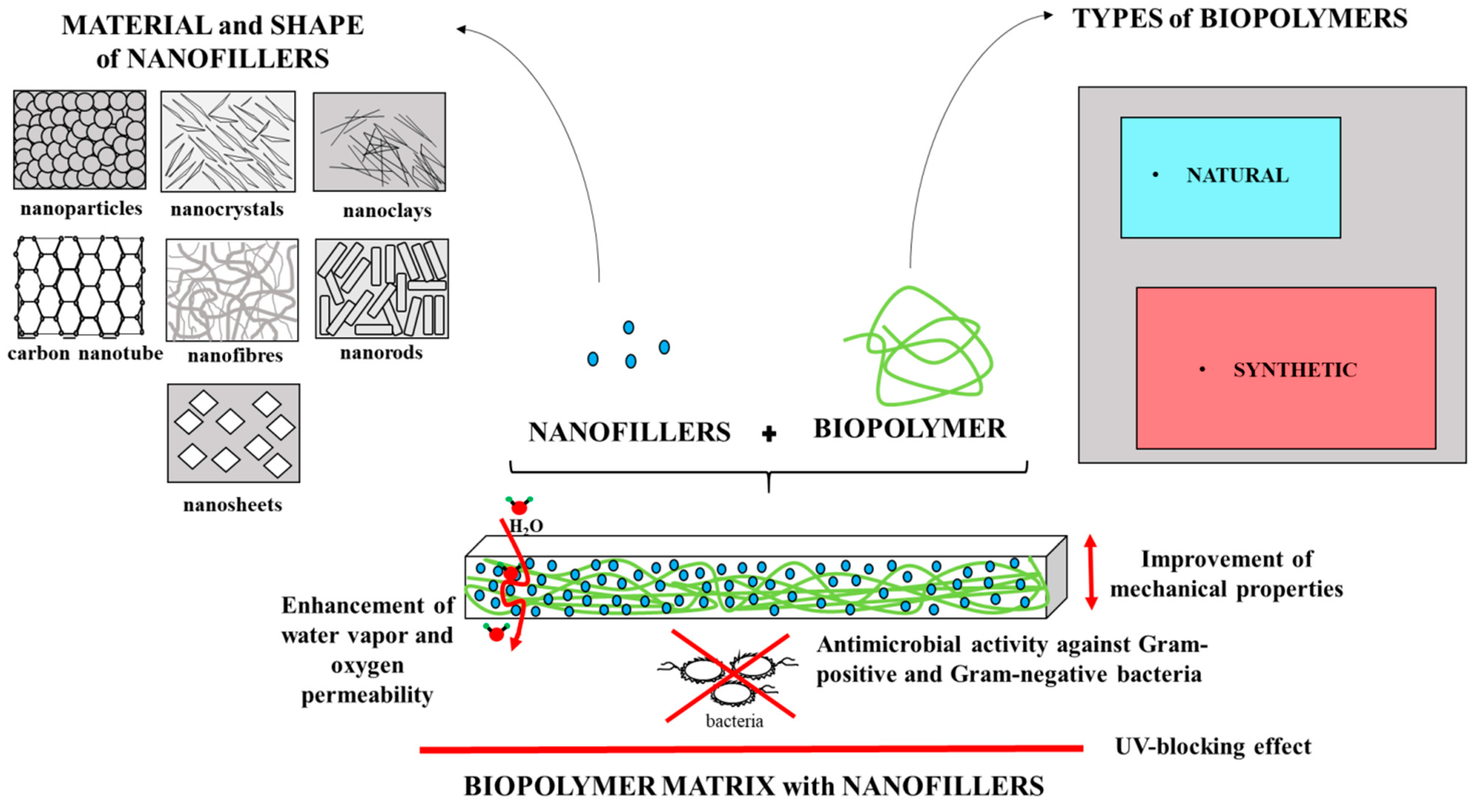

2. Types of Biopolymers and Nanofillers

2.1. Types of Biopolymers Matrix

- Natural bio-based polymers, including:

- -

- polymers extracted from agricultural resources:

- ■

- polysaccharides:

- neutral: e.g., cellulose, hemicellulose, starch

- cationic: e.g., chitin, chitosan

- anionic: alginic acid, hyaluronic acid

- of bacterial origin: e.g., pullulan, carrageenan;

- ■

- proteins: e.g., gelatin and whey protein;

- Other bio-based polymers: e.g., lipid, lignin, natural rubber, urushiol, DNA, etc. polymers produced directly from microorganisms bacterial cellulose; polyhydroxyalkanoates, poly-ɛ-caprolactones.

- Synthetic bio-based polymers, including:

2.2. Types of Nanofillers

2.2.1. Clay and Organic Nanofillers

2.2.2. Inorganic Nanofillers

2.2.3. Carbon Nanofillers

2.2.4. Other Nanofillers

3. Effects of Nanofillers on the Functional Properties of Biopolymer-Based Films

3.1. Effects of Nanofillers on the Physical Properties of Polymer-Based Films

3.2. Effects of Nanofillers on the Mechanical Properties of Polymer-Based Films

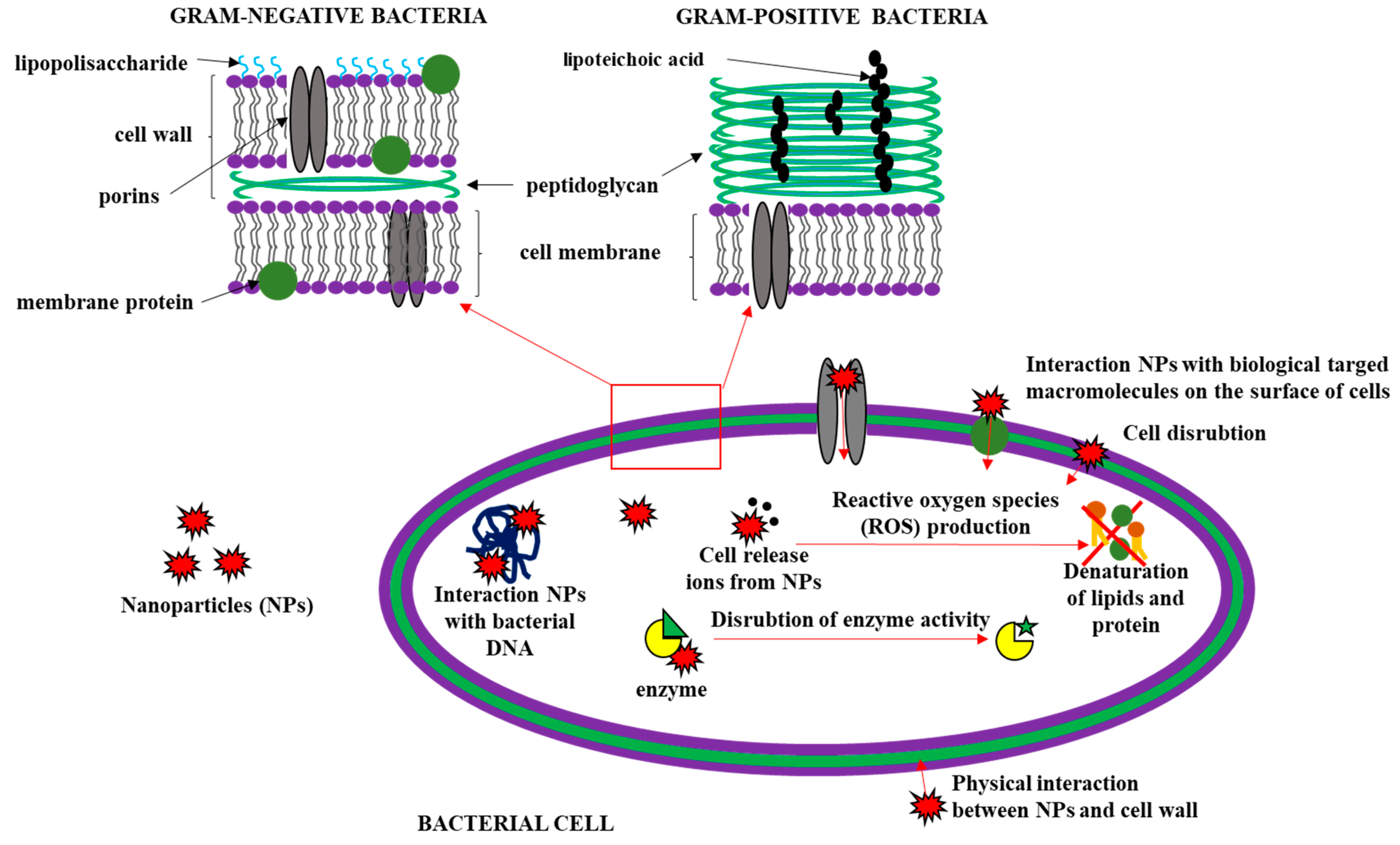

3.3. Effects of Nanofillers on the Antimicrobial Activity of Polymer-Based Films

- (1)

- the addition of antibacterial substances to the biopolymer matrix;

- (2)

- use of inherently antimicrobial polymer (for example polymer resins or chitosan);

- (3)

4. Functional Application of Biopolymer-Based Films with Nanofillers

4.1. Food Preservation Application

4.2. Wound Dressing

4.3. Drug and Enzyme Delivery System

4.4. Tissue Engineering Application

4.5. Other Applications

5. The Future of Nanomaterials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NPs | nanoparticles |

| CMC | carboxymethyl cellulose |

| PVA | poly(vinyl) alcohol |

| PLA | poly(lactic acid) |

| TS | tensile strength |

| EAB | elongation at break |

| YM | Young’s modulus |

| EM | elastic modulus |

| WVP | water vapor permeability |

| OP | oxygen permeability |

| WS | water solubility |

| SR | swelling ratio |

| MC | moisture content |

| WCA | water contact angle |

References

- George, J.; Ishida, H. A review on the very high nanofiller-content nanocomposites: Their preparation methods and properties with high aspect ratio fillers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2018, 86, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Achaby, M.; El Miri, N.; Aboulkas, A.; Zahouily, M.; Bilal, E.; Barakat, A.; Solhy, A. Processing and properties of eco-friendly bio-nanocomposite films filled with cellulose nanocrystals from sugarcane bagasse. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 96, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciotti, I.; Mori, S.; Cherubini, V.; Nanni, F. Eco-sustainable systems based on poly(lactic acid), diatomite and coffee grounds extract for food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sothornvit, R. Nanostructured materials for food packaging systems: New functional properties. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.-C.; Xiao, H.; Wang, X. Novel chitosan films with laponite immobilized Ag nanoparticles for active food packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 199, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.M.B.; Santos, T.M.; Caceres, C.A.; Lima, J.R.; Ito, E.N.; Azeredo, H.M.C. Starch-cashew tree gum nanocomposite films and their application for coating cashew nuts. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.M.; El-Sayed, S.M.; Salama, H.H.; El-Sayed, H.S.; Dufresne, A. Evaluation of bionanocomposites as packaging material on properties of soft white cheese during storage period. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 132, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, M.; Tajik, H.; Moradi, M.; Forough, M.; Divsalar, E.; Kuswandi, B. Nanostructured chitosan/ monolaurin film: Preparation, characterization and antimicrobial activity against Listeria monocytogenes on ultrafiltered white cheese. LWT 2018, 92, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, I.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Mauri, A.N.; Montero, M.P. Active nanocomposite films based on soy proteins-montmorillonite- clove essential oil for the preservation of refrigerated bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) fillets. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 266, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, S.; Snigdha, S.; Mathew, J.; Radhakrishnan, E.K. Biodegradable and active nanocomposite pouches reinforced with silver nanoparticles for improved packaging of chicken sausages. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 19, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Rehmani, N.; Alsubaie, L.; Kim, C.; Sismour, E.; Scales, A. Tapioca starch active nanocomposite films and their antimicrobial effectiveness on ready-to-eat chicken meat. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Alsammarraie, F.K.; Nayigiziki, F.X.; Wang, W.; Vardhanabhuti, B.; Mustapha, A.; Lin, M. Effect and mechanism of cellulose nanofibrils on the active functions of biopolymer-based nanocomposite films. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Xie, W.; Huang, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, N.; Wang, X.; Liu, J. The graphene oxide and chitosan biopolymer loads TiO2 for antibacterial and preservative research. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Qin, Y.; Ye, Q. Effect of nano-TiO2-LDPE packaging on microbiological and physicochemical quality of Pacific white shrimp during chilled storage. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 1567–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Yang, W.; Kimatu, B.M.; Mariga, A.M.; Zhao, L.; An, X.; Hu, Q. Effect of nanocomposite-based packaging on storage stability of mushrooms (Flammulina velutipes). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 33, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, K.; Jawaid, M.; Hassan, A.; Abu Bakar, A.; Abdul Khalil, H.P.S.; Salema, A.A.; Inuwa, I. Potential materials for food packaging from nanoclay/natural fibres filled hybrid composites. Mater. Des. 2013, 46, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, S.H. Bio-nanocomposite Materials for Food Packaging Applications: Types of Biopolymer and Nano-sized Filler. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2014, 2, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Grant, A.M.; Ma, R.; Zhang, S.; Tsukruk, V.V. Naturally-derived biopolymer nanocomposites: Interfacial design, properties and emerging applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2018, 125, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavand, F.; Rouhi, M.; Razavi, S.H.; Cacciotti, I.; Mohammadi, R. Improving the integrity of natural biopolymer films used in food packaging by crosslinking approach: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Malik, P.; Jain, P. Biopolymer reinforced nanocomposites: A comprehensive review. Mater. Today Commun. 2018, 16, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouf, T.B.; Kokini, J.L. Biodegradable biopolymer–graphene nanocomposites. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 9915–9945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, Y.; Shabani, I. Polymer/metal nanocomposites for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 60, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujtaba, M.; Morsi, R.E.; Kerch, G.; Elsabee, M.Z.; Kaya, M.; Labidi, J.; Khawar, K.M. Current advancements in chitosan-based film production for food technology: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsona, E.; Ojogbo, E.; Mekonnen, T. Advanced material applications of starch and its derivatives. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 108, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.S.; Kaur, N.; Rana, V.; Kennedy, J.F. Pullulan: A novel molecule for biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 171, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horinaka, J.-I.; Hashimoto, Y.; Takigawa, T. Optical and mechanical properties of pullulan films studied by uniaxial stretching. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, B.; Chatha, S.A.S.; Hussain, A.I.; Zia, K.M.; Akhtar, N. Recent advances on polysaccharides, lipids and protein based edible films and coatings: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 1095–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami, A.; Rezaei Mokarram, R.; Sowti Khiabani, M.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Salehi, R. Physico-mechanical and antimicrobial properties of tragacanth/hydroxypropyl methylcellulose/beeswax edible films reinforced with silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velickova, E.; Winkelhausen, E.; Kuzmanova, S.; Alves, V.D.; Moldão-Martins, M. Impact of chitosan-beeswax edible coatings on the quality of fresh strawberries (Fragaria ananassa cv Camarosa) under commercial storage conditions. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 52, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofar, M.; Sacligil, D.; Carreau, P.J.; Kamal, M.R.; Heuzey, M.-C. Poly (lactic acid) blends: Processing, properties and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 125, 307–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Wang, L.-F.; Rhim, J.-W. Incorporation of zinc oxide nanoparticles improved the mechanical, water vapor barrier, UV-light barrier, and antibacterial properties of PLA-based nanocomposite films. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 93, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thong, C.C.; Teo, D.C.L.; Ng, C.K. Application of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) in cement-based composite materials: A review of its engineering properties and microstructure behavior. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 107, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.A.; Ahmed, M.R.; Rahman, G.T.; Rahman, M.T.; Islam, M.A.; Khan, M.A.; Hossain, M.K. Fabrication and comparative study of magnetic Fe and α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles dispersed hybrid polymer (PVA + Chitosan) novel nanocomposite film. Results Phys. 2018, 10, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sanz, M.; Villano, M.; Oliveira, C.; Albuquerque, M.G.E.; Majone, M.; Reis, M.; Lopez-Rubio, A.; Lagaron, J.M. Characterization of polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesized from microbial mixed cultures and of their nanobiocomposites with bacterial cellulose nanowhiskers. New Biotechnol. 2014, 31, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.; Di Federico, E.; Cacciotti, I. Electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone)-based composites using synthesized β-tricalcium phosphate. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2011, 22, 1832–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, T.; Long, L.; Zhang, R.; Ding, S. Efficient enzymatic degradation of poly (ɛ-caprolactone) by an engineered bifunctional lipase-cutinase. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 160, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.; Calderone, M.; Cacciotti, I. Electrospun PHBV/PEO co-solution blends: Microstructure, thermal and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciotti, I.; Calderone, M.; Bianco, A. Tailoring the properties of electrospun PHBV mats: Co-solution blending and selective removal of PEO. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 3210–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lu, A.; Zhang, L. Recent advances in regenerated cellulose materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016, 53, 169–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, P.; Zhang, L.; Lu, A. Cationic hydrophobicity promotes dissolution of cellulose in aqueous basic solution by freezing-thawing. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. PCCP 2018, 20, 14223–14233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, S. Cellulose-based peptidopolysaccharides as cationic antimicrobial package films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 128, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.K.; Tripathi, S.; Mehrotra, G.K.; Dutta, J. Perspectives for chitosan based antimicrobial films in food applications. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlieghere, F.; Vermeulen, A.; Debevere, J. Chitosan: Antimicrobial activity, interactions with food components and applicability as a coating on fruit and vegetables. Food Microbiol. 2004, 21, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambabu, K.; Bharath, G.; Banat, F.; Show, P.L.; Cocoletzi, H.H. Mango leaf extract incorporated chitosan antioxidant film for active food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Neetoo, H.; Chen, H. Efficacy of freezing, frozen storage and edible antimicrobial coatings used in combination for control of Listeria monocytogenes on roasted turkey stored at chiller temperatures. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 1394–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.; Pristijono, P.; Scarlett, C.J.; Bowyer, M.; Singh, S.P.; Vuong, Q.V. Starch-based films: Major factors affecting their properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.P.M.; Oliveira, A.V.; Pontes, S.M.A.; Pereira, A.L.S.; Souza Filho, M.d.s.M.; Rosa, M.F.; Azeredo, H.M.C. Mango kernel starch films as affected by starch nanocrystals and cellulose nanocrystals. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 211, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younis, H.G.R.; Zhao, G. Physicochemical properties of the edible films from the blends of high methoxyl apple pectin and chitosan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spatafora Salazar, A.S.; Sáenz Cavazos, P.A.; Mújica Paz, H.; Valdez Fragoso, A. External factors and nanoparticles effect on water vapor permeability of pectin-based films. J. Food Eng. 2019, 245, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Shao, P.; Chen, H.; Sun, P. Structural and physiochemical characterization of novel hydrophobic packaging films based on pullulan derivatives for fruits preservation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 208, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Xu, T.; Gao, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, N.; Feng, X.; Liu, X.; Shen, X.; Tang, X. Evaluations of physicochemical and biological properties of pullulan-based films incorporated with cinnamon essential oil and Tween 80. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Choi, Y.-G.; Byul Kim, S.R.; Lim, S.-T. Humidity stability of tapioca starch–pullulan composite films. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 41, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, H.E.; Abdel Aziz, M.S.; Sabaa, M.W. Novel biodegradable and antibacterial edible films based on alginate and chitosan biguanidine hydrochloride. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 116, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Zhu, J.; Guan, G.; Wu, H. Preparation of chitosan-sodium alginate films through layer-by-layer assembly and ferulic acid crosslinking: Film properties, characterization, and formation mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinaro, S.; Cruz-Romero, M.; Sensidoni, A.; Morris, M.; Lagazio, C.; Kerry, J.P. Combination of high-pressure treatment, mild heating and holding time effects as a means of improving the barrier properties of gelatin-based packaging films using response surface modeling. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 30, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanani, Z.A.N.; Yee, F.C.; Nor-Khaizura, M.A.R. Effect of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel powder on the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of fish gelatin films as active packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 89, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumarelli, M.; Hubinger, M.D. Stability, solubility, mechanical and barrier properties of cassava starch – Carnauba wax edible coatings to preserve fresh-cut apples. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 28, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, F.G.; Arroyo, J.J.; Troncoso, O.P. Bacterial cellulose nanocomposites: An all-nano type of material. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 98, 1277–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.D.; Sierakowski, M.R.; Bassani, H.P.; Zawadzki, S.F.; Pirich, C.L.; Ono, L.; de Freitas, R.A. Hydrophilicity improvement of mercerized bacterial cellulose films by polyethylene glycol graft. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 86, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-M.; Prasannan, A.; Tsai, H.-C.; Jhu, J.-J. Ex vivo evaluation of biodegradable poly(ɛ-caprolactone) films in digestive fluids. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 313, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosnáček, J.; Borská, K.; Danko, M.; Janigová, I. Photochemically promoted degradation of poly(ɛ-caprolactone) film. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2013, 140, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yao, Z.; Zhou, J.; He, M.; Jiang, Q.; Li, A.; Li, S.; Liu, M.; Luo, S.; Zhang, D. Improvement of polylactic acid film properties through the addition of cellulose nanocrystals isolated from waste cotton cloth. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 129, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murariu, M.; Dubois, P. PLA composites: From production to properties. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhiri, S.; Mignard, N.; Abid, M.; Prochazka, F.; Majeste, J.-C.; Taha, M. Thermally reversible and biodegradable polyglycolic-acid-based networks. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 88, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Min, B.-M.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, T.S.; Park, W.H. In vitro degradation behavior of electrospun polyglycolide, polylactide, and poly(lactide-co-glycolide). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 95, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Hu, X.; Yang, Z.; Shen, L.; Zheng, Z. Preparation and properties of waterborne bio-based polyurethane/siloxane cross-linked films by an in situ sol–gel process. Prog. Org. Coat. 2015, 84, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.M.; El-Sayed, S.M. Bionanocomposites materials for food packaging applications: Concepts and future outlook. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 193, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahzadeh, M.; Issaabadi, Z.; Sajjadi, M.; Sajadi, S.M.; Atarod, M. Chapter 2—Types of Nanostructures. In Interface Science and Technology; Nasrollahzadeh, M., Sajadi, S.M., Sajjadi, M., Issaabadi, Z., Atarod, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 28, pp. 29–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fathi Achachlouei, B.; Zahedi, Y. Fabrication and characterization of CMC-based nanocomposites reinforced with sodium montmorillonite and TiO2 nanomaterials. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 199, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.T.; Zhou, C.H.; Kabwe, F.B.; Wu, Q.Q.; Li, C.S.; Zhang, J.R. Exfoliation of montmorillonite and related properties of clay/polymer nanocomposites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 169, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonguzhali, R.; Basha, S.K.; Kumari, V.S. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan-PVP-nanocellulose composites for in-vitro wound dressing application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adel, A.; El-Shafei, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Al-Shemy, M. Extraction of oxidized nanocellulose from date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) sheath fibers: Influence of CI and CII polymorphs on the properties of chitosan/bionanocomposite films. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 124, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curvello, R.; Raghuwanshi, V.S.; Garnier, G. Engineering nanocellulose hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv. Coll. Interface Sci. 2019, 267, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Xu, X.; Feng, J.; Liu, M.; Hu, K. Chitosan and chitosan coating nanoparticles for the treatment of brain disease. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 560, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.O.; Segalla Petrônio, M.; Furuyama Lima, A.M.; Martinez Junior, A.M.; de Oliveira Tiera, V.A.; de Freitas Calmon, M.; Leite Vilamaior, P.S.; Han, S.W.; Tiera, M.J. Amphipathic Chitosans Improve the Physicochemical Properties of siRNA-Chitosan Nanoparticles at Physiological Conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Qian, J.; Fan, J.; Guo, H.; Gou, L.; Yang, H.; Liang, C. Preparation nanoparticle by ionic cross-linked emulsified chitosan and its antibacterial activity. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2019, 568, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, M.; Kiran, G.S.; Hassan, S.; Selvin, J. Biogenic synthesis and effect of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) to combat catheter-related urinary tract infections. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Shankar, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Melanin-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticle and its use for the preparation of carrageenan-based antibacterial films. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 88, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, D.; Momin, B.; Palamthodi, S.; Lele, S.S. Physicochemical and functional properties of chitosan-based nano-composite films incorporated with biogenic silver nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 211, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshchi, E.; Pirsa, S.; Roufegarinejad, L.; Alizadeh, M.; Rezazad, M. Photocatalytic/biodegradable film based on carboxymethyl cellulose, modified by gelatin and TiO2-Ag nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamróz, E.; Kopel, P.; Juszczak, L.; Kawecka, A.; Bytesnikova, Z.; Milosavljević, V.; Kucharek, M.; Makarewicz, M.; Adam, V. Development and characterisation of furcellaran-gelatin films containing SeNPs and AgNPs that have antimicrobial activity. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 83, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalishwaralal, K.; Jeyabharathi, S.; Sundar, K.; Muthukumaran, A. A novel one-pot green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and evaluation of its toxicity in zebrafish embryos. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2016, 44, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, S.; Teng, X.; Rhim, J.-W. Properties and characterization of agar/CuNP bionanocomposite films prepared with different copper salts and reducing agents. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 114, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Rhim, J.-W.; Jaiswal, L. Bioactive agar-based functional composite film incorporated with copper sulfide nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 93, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Preparation of sulfur nanoparticle-incorporated antimicrobial chitosan films. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 82, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, S.; Lakshmi, D.S.; Thiagarajan, V.; Mrudula, P.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Mukherjee, A. Antifouling and anti-algal effects of chitosan nanocomposite (TiO2/Ag) and pristine (TiO2 and Ag) films on marine microalgae Dunaliella salina. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 6870–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Khezerlou, A.; Ehsani, A. Fabrication and characterization of the bionanocomposite film based on whey protein biopolymer loaded with TiO2 nanoparticles, cellulose nanofibers and rosemary essential oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 124, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jbeli, A.; Hamden, Z.; Bouattour, S.; Ferraria, A.M.; Conceição, D.S.; Ferreira, L.F.V.; Chehimi, M.M.; do Rego, A.M.B.; Rei Vilar, M.; Boufi, S. Chitosan-Ag-TiO2 films: An effective photocatalyst under visible light. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 199, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noshirvani, N.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Mokarram, R.R.; Hashemi, M.; Coma, V. Preparation and characterization of active emulsified films based on chitosan-carboxymethyl cellulose containing zinc oxide nano particles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 99, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdeen, Z.I.; El Farargy, A.F.; Negm, N.A. Nanocomposite framework of chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol/ZnO: Preparation, characterization, swelling and antimicrobial evaluation. J. Mol. Liquids 2018, 250, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnamma, D.; Cabibihan, J.-J.; Rajan, M.; Pethaiah, S.S.; Deshmukh, K.; Gogoi, J.P.; Pasha, S.K.K.; Ahamed, M.B.; Krishnegowda, J.; Chandrashekar, B.N.; et al. Synthesis, optimization and applications of ZnO/polymer nanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 98, 1210–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, R.; Narayan, A.; Bramhecha, I.; Sheikh, J. Development of multifunctional linen fabric using chitosan film as a template for immobilization of in-situ generated CeO2 nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 1154–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Murugadoss, V.; Kong, J.; He, Z.; Mai, X.; Shao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, C.; Angaiah, S.; et al. Overview of carbon nanostructures and nanocomposites for electromagnetic wave shielding. Carbon 2018, 140, 696–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Gao, J.; Dong, S.; Luo, G.; Li, H.; Zhao, L. Applications of hybrid organic–inorganic materials in chiral separation. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2017, 95, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Kasapis, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Alginate-based nanocomposite films reinforced with halloysite nanotubes functionalized by alkali treatment and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 1824–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J. Potent antibacterial activity of a novel silver nanoparticle-halloysite nanotube nanocomposite powder. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2013, 118, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, K. Preparation and antibacterial property of polyethersulfone ultrafiltration hybrid membrane containing halloysite nanotubes loaded with copper ions. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 210, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Chen, W.; Fan, Y.; Zheng, K.; Jin, K.; Yu, H.; Buehler, M.J.; Kaplan, D.L. Biopolymer nanofibrils: Structure, modeling, preparation, and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2018, 85, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Khalil, H.P.S.; Bhat, A.H.; Ireana Yusra, A.F. Green composites from sustainable cellulose nanofibrils: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanthong, P.; Reubroycharoen, P.; Hao, X.; Xu, G.; Abudula, A.; Guan, G. Nanocellulose: Extraction and application. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2018, 1, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Kharkar, P.S.; Pethe, A.M. Biomass and waste materials as potential sources of nanocrystalline cellulose: Comparative review of preparation methods (2016–Till date). Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 207, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, A.A.; Rhim, J.-W. Isolation of cellulose nanocrystals from grain straws and their use for the preparation of carboxymethyl cellulose-based nanocomposite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 150, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niamsap, T.; Lam, N.T.; Sukyai, P. Production of hydroxyapatite-bacterial nanocellulose scaffold with assist of cellulose nanocrystals. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 205, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Luan, Q.; Zheng, M.; Tang, H.; Huang, F. Fabrication of cellulose nanowhiskers reinforced chitosan-xylan nanocomposite films with antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 184, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouhi, M.; Razavi, S.H.; Mousavi, S.M. Optimization of crosslinked poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposite films for mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 71, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Silva, D.A.; Rivero, S.; Pinotti, A. Chitosan-based nanocomposite matrices: Development and characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciotti, I.; Fortunati, E.; Puglia, D.; Kenny, J.M.; Nanni, F. Effect of silver nanoparticles and cellulose nanocrystals on electrospun poly(lactic) acid mats: Morphology, thermal properties and mechanical behavior. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 103, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, S.; Muralidhara, H.B.; Venkatesh, K.; Guna, V.K.; Gopalakrishna, K.; Kumar, Y. Potential applications of cellulose and chitosan nanoparticles/composites in wastewater treatment: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 153, 600–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarifar, M.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Sowti Khiabani, M.; Akhondzadeh Basti, A.; Abdulkhani, A.; Noshirvani, N.; Hosseini, M. The optimization of gelatin-CMC based active films containing chitin nanofiber and Trachyspermum ammi essential oil by response surface methodology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 208, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E.A.; Hassan, M.L.; Abou-zeid, R.E.; El-Wakil, N.A. Novel nanofibrillated cellulose/chitosan nanoparticles nanocomposites films and their use for paper coating. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 93, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Liang, T.; Cao, L.; Wang, L. Intelligent poly (vinyl alcohol)-chitosan nanoparticles-mulberry extracts films capable of monitoring pH variations. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedikia, N.; Garavand, F.; Tajeddin, B.; Cacciotti, I.; Jafari, S.M.; Omidi, T.; Zahedi, Z. Biodegradable zein film composites reinforced with chitosan nanoparticles and cinnamon essential oil: Physical, mechanical, structural and antimicrobial attributes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 177, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naskar, S.; Sharma, S.; Kuotsu, K. Chitosan-based nanoparticles: An overview of biomedical applications and its preparation. J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2019, 49, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengan, M.; Subramaniyan, S.B.; Arul Prakash, S.; Kamlekar, R.; Veerappan, A. Effective elimination of biofilm formed with waterborne pathogens using copper nanoparticles. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 127, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.D.; Rajendran, N.K.; Houreld, N.N.; Abrahamse, H. Recent advances on silver nanoparticle and biopolymer-based biomaterials for wound healing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, M.; Donia, D.T.; Sabbatella, G.; Antiochia, R. Silver nanoparticles in polymeric matrices for fresh food packaging. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2016, 28, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-B.; Lih, E.; Park, K.-S.; Joung, Y.K.; Han, D.K. Biopolymer-based functional composites for medical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 68, 77–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, A.; Tekula, S.; Saifi, M.A.; Venkatesh, P.; Godugu, C. Therapeutic applications of selenium nanoparticles. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.V.; Shin, G.H.; Kim, J.T. Metal oxide-based nanocomposites in food packaging: Applications, migration, and regulations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 82, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, A.; Pomastowski, P.; Rafińska, K.; Railean-Plugaru, V.; Buszewski, B. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis, antiseptic activity and toxicity mechanism. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 249, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleyaei, S.A.; Zahedi, Y.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Moayedi, A.A. Modification of physicochemical and thermal properties of starch films by incorporation of TiO2 nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 89, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, B.K.; Kong, K.; Seo, J.; Kim, D.; Park, Y.-B.; Park, H.W. Controlled growth of CuO nanowires on woven carbon fibers and effects on the mechanical properties of woven carbon fiber/polyester composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2015, 69, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebnalwaled, A.A.; Ismaiel, A.M. Developing novel UV shielding films based on PVA/Gelatin/0.01CuO nanocomposite: On the properties optimization using γ-irradiation. Measurement 2019, 134, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Xu, X. SnO2-Based Nanomaterials: Synthesis and Application in Lithium-Ion Batteries and Supercapacitors. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 805147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniasad, A.; Ghorbani, M. Thermal stability enhancement of modified carboxymethyl cellulose films using SnO2 nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 86, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, T.; Armstrong, G.; Laffir, F.; Thornton, R. Titania–silver and alumina–silver composite nanoparticles: Novel, versatile synthesis, reaction mechanism and potential antimicrobial application. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 356, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, Z.; Esmaiili, M.; Almasi, H. Development and characterization of kefiran—Al2O3 nanocomposite films: Morphological, physical and mechanical properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; Song, M. A study of crystallisation of poly (ethylene oxide) and polypropylene on graphene surface. Polymer 2015, 73, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, S.; Zakaria, S.; Syed Jaafar, S.N. Enhanced mechanical properties of hydrothermal carbamated cellulose nanocomposite film reinforced with graphene oxide. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 172, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.W.; Shin, M.; Yun, H.; Lee, K.H. Preparation of Silk Sericin/Lignin Blend Beads for the Removal of Hexavalent Chromium Ions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkhani, A.; Daliri Sousefi, M.; Ashori, A.; Ebrahimi, G. Preparation and characterization of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose/silk fibroin/graphene oxide nanocomposite films. Polym. Test. 2016, 52, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakaei, K.; Marzang, K. One – Step synthesis of nitrogen doped reduced graphene oxide with NiCo nanoparticles for ethanol oxidation in alkaline media. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 462, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, R.; Yan, D.; Tian, R.; Yu, X.; Shi, W.; Li, C.; Wei, M.; Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Quantum Dots-Based Flexible Films and Their Application as the Phosphor in White Light-Emitting Diodes. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 2595–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ge, X.; Guan, J.; Wu, L.; Zhao, F.; Li, H.; Mu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, A. A novel method for fabricating hybrid bio-based nanocomposites film with stable fluorescence containing CdTe quantum dots and montmorillonite-chitosan nanosheets. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 145, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanbakht, S.; Namazi, H. Solid state photoluminescence thermoplastic starch film containing graphene quantum dots. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 176, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, S.F.; Rezaei, M.; Zandi, M.; Farahmandghavi, F. Development of bioactive fish gelatin/chitosan nanoparticles composite films with antimicrobial properties. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Chang, P.R.; Anderson, D.P.; Huneault, M.A. Pea starch-based composite films with pea hull fibers and pea hull fiber-derived nanowhiskers. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2009, 49, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noshirvani, N.; Hong, W.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Fasihi, H.; Montazami, R. Study of cellulose nanocrystal doped starch-polyvinyl alcohol bionanocomposite films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 2065–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasheminya, S.-M.; Mokarram, R.R.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Hamishekar, H.; Kafil, H.S.; Dehghannya, J. Influence of simultaneous application of copper oxide nanoparticles and Satureja Khuzestanica essential oil on properties of kefiran–carboxymethyl cellulose films. Polym. Test. 2019, 73, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipoormazandarani, N.; Ghazihoseini, S.; Mohammadi Nafchi, A. Preparation and characterization of novel bionanocomposite based on soluble soybean polysaccharide and halloysite nanoclay. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 134, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfi, M.; Khodaiyan, F.; Mousavi, M.; Hashemi, M. The improvement of characteristics of biodegradable films made from kefiran–whey protein by nanoparticle incorporation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 109, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassannia-Kolaee, M.; Khodaiyan, F.; Pourahmad, R.; Shahabi-Ghahfarrokhi, I. Development of ecofriendly bionanocomposite: Whey protein isolate/pullulan films with nano-SiO2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 86, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, J.; Yang, J.; Xiong, L.; Sun, Q. Effects of chitin nano-whiskers on the antibacterial and physicochemical properties of maize starch films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 147, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, H.; Pirouzifard, M.; Khaledabad, M.A.; Almasi, H. Effect of chitin nanofiber on the morphological and physical properties of chitosan/silver nanoparticle bionanocomposite films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 92, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, N.; Dutta, J. Development and in vitro characterization of chitosan/starch/halloysite nanotubes ternary nanocomposite films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 127, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejdan, A.; Ojagh, S.M.; Adeli, A.; Abdollahi, M. Effect of TiO2 nanoparticles on the physico-mechanical and ultraviolet light barrier properties of fish gelatin/agar bilayer film. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 71, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamzad, H.; Paighambari, S.Y.; Shabanpour, B.; Ojagh, S.M.; Mousavi, S.M. Improvement of fish protein film with nanoclay and transglutaminase for food packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2016, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davachi, S.M.; Shekarabi, A.S. Preparation and characterization of antibacterial, eco-friendly edible nanocomposite films containing Salvia macrosiphon and nanoclay. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 113, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazón, P.; Velazquez, G.; Ramírez, J.A.; Vázquez, M. Polysaccharide-based films and coatings for food packaging: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 68, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Preparation and characterization of agar/lignin/silver nanoparticles composite films with ultraviolet light barrier and antibacterial properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 71, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomate, G.B.; Dandi, B.; Mishra, S. Development of antimicrobial LDPE/Cu nanocomposite food packaging film for extended shelf life of peda. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yu, M.; Wang, L. Soy protein isolate nanocomposites reinforced with nanocellulose isolated from licorice residue: Water sensitivity and mechanical strength. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 117, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ishak, M.R.; Zainudin, E.S. Development and characterization of sugar palm nanocrystalline cellulose reinforced sugar palm starch bionanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 202, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, Y.; Fathi-Achachlouei, B.; Yousefi, A.R. Physical and mechanical properties of hybrid montmorillonite/zinc oxide reinforced carboxymethyl cellulose nanocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, J.-W. Effect of clay contents on mechanical and water vapor barrier properties of agar-based nanocomposite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klangmuang, P.; Sothornvit, R. Combination of beeswax and nanoclay on barriers, sorption isotherm and mechanical properties of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose-based composite films. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 65, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, N.; Rouf, T.B.; Bonilla, J.C.; Carriazo, J.G.; Dianda, N.; Kokini, J.L. Effect of LAPONITE® addition on the mechanical, barrier and surface properties of novel biodegradable kafirin nanocomposite films. J. Food Eng. 2019, 245, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, G.A.; Luciano, C.G.; Lourenço, R.V.; Bittante, A.M.Q.B.; do Amaral Sobral, P.J. Morphological and physical properties of nano-biocomposite films based on collagen loaded with laponite®. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 19, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, F.J.; Galotto, M.J.; Guarda, A.; Bruna, J.E. Modification of cellulose acetate films using nanofillers based on organoclays. J. Food Eng. 2012, 110, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Teng, X.; Li, G.; Rhim, J.-W. Preparation, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of gelatin/ZnO nanocomposite films. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 45, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.; Barud, H.S.; Meneguin, A.B.; Constantino, V.R.L.; Ribeiro, S.J.L. Inorganic-organic bio-nanocomposite films based on Laponite and Cellulose Nanofibers (CNF). Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 168, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indumathi, M.P.; Saral Sarojini, K.; Rajarajeswari, G.R. Antimicrobial and biodegradable chitosan/cellulose acetate phthalate/ZnO nano composite films with optimal oxygen permeability and hydrophobicity for extending the shelf life of black grape fruits. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Deng, W.; Luo, J.; Deng, D. Multifunctional nano-cellulose composite films with grape seed extracts and immobilized silver nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 205, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadegh-Hassani, F.; Mohammadi Nafchi, A. Preparation and characterization of bionanocomposite films based on potato starch/halloysite nanoclay. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 67, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschini, I.; Selmin, F.; Pagani, S.; Minghetti, P.; Cilurzo, F. Nanofiller for the mechanical reinforcement of maltodextrins orodispersible films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 136, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaezi, K.; Asadpour, G.; Sharifi, H. Effect of ZnO nanoparticles on the mechanical, barrier and optical properties of thermoplastic cationic starch/montmorillonite biodegradable films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 124, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Wang, L.; Tong, C.; Hu, Y.; Pang, J.; Yan, Z. Preparation and characterization of konjac glucomannan-based bionanocomposite film for active food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 89, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memiş, S.; Tornuk, F.; Bozkurt, F.; Durak, M.Z. Production and characterization of a new biodegradable fenugreek seed gum based active nanocomposite film reinforced with nanoclays. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri, A.; Yaraki, M.T.; Ghorbanpour, M.; Agarwal, S.; Gupta, V.K. Enhanced Antibacterial effect of chitosan film using Montmorillonite/CuO nanocomposite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 1219–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Miri, N.; Abdelouahdi, K.; Barakat, A.; Zahouily, M.; Fihri, A.; Solhy, A.; El Achaby, M. Bio-nanocomposite films reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals: Rheology of film-forming solutions, transparency, water vapor barrier and tensile properties of films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 129, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahnaky, A.; Dadfar, S.M.M.; Shahbazi, M. Physical and mechanical properties of gelatin–clay nanocomposite. J. Food Eng. 2014, 122, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, M.-C.; Dogaru, B.-I.; Goanta, M.; Timpu, D. Structural and morphological evaluation of CNC reinforced PVA/Starch biodegradable films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 116, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfat, Y.A.; Ahmed, J.; Hiremath, N.; Auras, R.; Joseph, A. Thermo-mechanical, rheological, structural and antimicrobial properties of bionanocomposite films based on fish skin gelatin and silver-copper nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 62, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvizadeh, M.M.; Oladzadabbasabadi, N.; Mohammadi Nafchi, A.; Jokar, M. Preparation and characterization of bionanocomposite film based on tapioca starch/bovine gelatin/nanorod zinc oxide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 99, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicentini, N.; Gatti, T.; Salerno, M.; Hernandez Gomez, Y.S.; Bellon, M.; Gallio, S.; Marega, C.; Filippini, F.; Menna, E. Effect of different functionalized carbon nanostructures as fillers on the physical properties of biocompatible poly(l-lactic acid) composites. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 214, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Mulla, M.; Arfat, Y.A.; Thai T, L.A. Mechanical, thermal, structural and barrier properties of crab shell chitosan/graphene oxide composite films. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 71, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.-R.; Rhee, K.Y.; Park, S.-J. Influence of reduced graphene oxide on mechanical behaviors of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 83, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Achaby, M.; Kassab, Z.; Barakat, A.; Aboulkas, A. Alfa fibers as viable sustainable source for cellulose nanocrystals extraction: Application for improving the tensile properties of biopolymer nanocomposite films. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassab, Z.; Aziz, F.; Hannache, H.; Ben Youcef, H.; El Achaby, M. Improved mechanical properties of k-carrageenan-based nanocomposite films reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 1248–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanmani, P.; Rhim, J.-W. Properties and characterization of bionanocomposite films prepared with various biopolymers and ZnO nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 106, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlalila, N.; Hilonga, A.; Swai, H.; Devlieghere, F.; Ragaert, P. Antimicrobial packaging based on starch, poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) and poly(lactic-co-glycolide) materials and application challenges. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Garrido-Maestu, A.; Jeong, K.C. Application, mode of action, and in vivo activity of chitosan and its micro- and nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 176, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Brauer, M.J.; Botstein, D. Slow growth induces heat-shock resistance in normal and respiratory-deficient yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 2009, 20, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, M.; Sowti Khiabani, M.; Rezaei Mokarram, R.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Samadi Kafil, H. Development and evaluation of chitosan based active nanocomposite films containing bacterial cellulose nanocrystals and silver nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 84, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Nafchi, A.; Moradpour, M.; Saeidi, M.; Alias, A.K. Effects of nanorod-rich ZnO on rheological, sorption isotherm, and physicochemical properties of bovine gelatin films. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 58, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy Choudhury, S.; Goswami, A. Supramolecular reactive sulphur nanoparticles: A novel and efficient antimicrobial agent. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 114, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besinis, A.; De Peralta, T.; Handy, R.D. The antibacterial effects of silver, titanium dioxide and silica dioxide nanoparticles compared to the dental disinfectant chlorhexidine on Streptococcus mutans using a suite of bioassays. Nanotoxicology 2014, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seil, J.T.; Webster, T.J. Antimicrobial applications of nanotechnology: Methods and literature. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 2767–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sothornvit, R.; Rhim, J.-W.; Hong, S.-I. Effect of nano-clay type on the physical and antimicrobial properties of whey protein isolate/clay composite films. J. Food Eng. 2009, 91, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, J.-W.; Hong, S.-I.; Ha, C.-S. Tensile, water vapor barrier and antimicrobial properties of PLA/nanoclay composite films. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.; Vlacha, M.; Salmas, C.; Leontiou, A.; Katapodis, P.; Stamatis, H.; Barkoula, N.-M.; Ladavos, A. Preparation, characterization, mechanical, barrier and antimicrobial properties of chitosan/PVOH/clay nanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 140, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, S.; Reddy, J.P.; Rhim, J.-W.; Kim, H.-Y. Preparation, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of chitin nanofibrils reinforced carrageenan nanocomposite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 117, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafchi, A.M.; Alias, A.K.; Mahmud, S.; Robal, M. Antimicrobial, rheological, and physicochemical properties of sago starch films filled with nanorod-rich zinc oxide. J. Food Eng. 2012, 113, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Han, H. A new function of graphene oxide emerges: Inactivating phytopathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2013, 15, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M.; Dadashpour, M.; Hejazi, M.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Behnam, B.; de la Guardia, M.; Shadjou, N.; Mokhtarzadeh, A. Anti-bacterial activity of graphene oxide as a new weapon nanomaterial to combat multidrug-resistance bacteria. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 74, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Jia, X.; Zhi, C.; Jin, Z.; Miao, M. Improving the properties of starch-based antimicrobial composite films using ZnO-chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, A.; Hussain, Z.; Riaz, A.; Khan, A.N. Enhanced mechanical, thermal and antimicrobial properties of poly(vinyl alcohol)/graphene oxide/starch/silver nanocomposites films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 153, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.; Dubey, P.; Gopinath, P.; Pal, K. Combined effect of cellulose nanocrystal and reduced graphene oxide into poly-lactic acid matrix nanocomposite as a scaffold and its anti-bacterial activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 95, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanmani, P.; Rhim, J.-W. Physicochemical properties of gelatin/silver nanoparticle antimicrobial composite films. Food Chem. 2014, 148, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Shukla, A.; Baul, P.P.; Mitra, A.; Halder, D. Biodegradable hybrid nanocomposites of chitosan/gelatin and silver nanoparticles for active food packaging applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Hussain, I.; Murtaza, G. Chemical synthesis and characterization of chitosan/silver nanocomposites films and their potential antibacterial activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 116, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Chen, L.; Huang, L.; Cao, S.; Luo, X.; Liu, K. Novel antimicrobial chitosan–cellulose composite films bioconjugated with silver nanoparticles. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 70, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji, S.; Salem, R.B.S.-B.; Hamdi, M.; Jellouli, K.; Ayadi, W.; Nasri, M.; Boufi, S. Nanocomposite films based on chitosan–poly(vinyl alcohol) and silver nanoparticles with high antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 111, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.M.; Abdel-Aziz, M.S.; El-Sayed, S.M. Chitosan nanocomposite films based on Ag-NP and Au-NP biosynthesis by Bacillus Subtilis as packaging materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 69, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dairi, N.; Ferfera-Harrar, H.; Ramos, M.; Garrigós, M.C. Cellulose acetate/AgNPs-organoclay and/or thymol nano-biocomposite films with combined antimicrobial/antioxidant properties for active food packaging use. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, M.S.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Jahan, Z.; Ahmad, T.; Hussain, A. Preparation and characterization of PVA/nanocellulose/Ag nanocomposite films for antimicrobial food packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 184, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín, T.; Montoya, P.; Arnache, O.; Pinal, R.; Calderón, J. Development of magnetite nanoparticles/gelatin composite films for triggering drug release by an external magnetic field. Mater. Des. 2018, 152, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloster, G.A.; Muraca, D.; Moscoso Londoño, O.; Knobel, M.; Marcovich, N.E.; Mosiewicki, M.A. Structural analysis of magnetic nanocomposites based on chitosan. Polym. Test. 2018, 72, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, X.; Wang, S. Fabrication of gelatin–TiO2 nanocomposite film and its structural, antibacterial and physical properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 84, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siripatrawan, U.; Kaewklin, P. Fabrication and characterization of chitosan-titanium dioxide nanocomposite film as ethylene scavenging and antimicrobial active food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 84, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.M.; El-Sayed, S.M.; El-Sayed, H.S.; Salama, H.H.; Dufresne, A. Enhancement of Egyptian soft white cheese shelf life using a novel chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose/zinc oxide bionanocomposite film. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 151, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Xu, X.-F.; Deng, R.-H.; Xia, G.-Q.; Shang, X.-F.; Zhou, P.-H. Construction of chitosan/ZnO nanocomposite film by in situ precipitation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saral Sarojini, K.; Indumathi, M.P.; Rajarajeswari, G.R. Mahua oil-based polyurethane/chitosan/nano ZnO composite films for biodegradable food packaging applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 124, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Krishnakumar, B.; Sobral, A.J.F.N.; Koh, J. Bio-based (chitosan/PVA/ZnO) nanocomposites film: Thermally stable and photoluminescence material for removal of organic dye. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 205, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, A.A.; Rhim, J.-W. Carrageenan-based hydrogels and films: Effect of ZnO and CuO nanoparticles on the physical, mechanical, and antimicrobial properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 67, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M. Study on thermal and mechanical properties of cellulose/iron oxide bionanocomposites film. Compos. Commun. 2018, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaroop, C.; Shukla, M. Mechanical, Optical and Antibacterial Properties of Polylactic Acid/Polyethylene Glycol Films Reinforced with MgO Nanoparticles. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 20711–20718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, S.; Ariffin, F.; Mahmud, S.; Alias, A.K.; Hosseini, S.F.; Ahmad, M. Improving the physical and protective functions of semolina films by embedding a blend nanofillers (ZnO-nr and nano-kaolin). Food Packag. Shelf Life 2017, 12, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, M.; Arfat, Y.A.; Mulla, M.; Ahmed, J. Zinc oxide nanorods/clove essential oil incorporated Type B gelatin composite films and its applicability for shrimp packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 15, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbariazam, M.; Ahmadi, M.; Javadian, N.; Mohammadi Nafchi, A. Fabrication and characterization of soluble soybean polysaccharide and nanorod-rich ZnO bionanocomposite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 89, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutalib, M.M. Effect of zinc oxide nanorods on the structural, thermal, dielectric and electrical properties of polyvinyl alcohol/carboxymethyle cellulose composites. Phys. B Condensed Matter 2019, 557, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, A.B.; Sellamuthu, P.S.; Nambiar, R.B.; Sadiku, E.R. Development of polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan bio-nanocomposite films reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals isolated from rice straw. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 449, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, M.; Salaberria, A.M.; Andres, M.A.; Kaya, M.; Gunyakti, A.; Labidi, J. Utilization of flax (Linum usitatissimum) cellulose nanocrystals as reinforcing material for chitosan films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, S.Y.; Mubarak, N.M.; Tanjung, F.A. Structure-property relationship of cellulose nanowhiskers reinforced chitosan biocomposite films. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 6132–6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.; Guo, D.; Zhang, J. Preparation and properties of chitosan/guar gum/nanocrystalline cellulose nanocomposite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 197, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oun, A.A.; Rhim, J.-W. Preparation and characterization of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose/cotton linter cellulose nanofibril composite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 127, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Achaby, M.; El Miri, N.; Hannache, H.; Gmouh, S.; Ben youcef, H.; Aboulkas, A. Production of cellulose nanocrystals from vine shoots and their use for the development of nanocomposite materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 117, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, A.; Gastelú, G.; Barrera, G.N.; Ribotta, P.D.; Álvarez Igarzabal, C.I. Preparation and characterization of soy protein films reinforced with cellulose nanofibers obtained from soybean by-products. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 89, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Cheng, Y.; Qin, X.; Guo, T.; Deng, J.; Liu, X. Hydrophilic modification of cellulose nanocrystals improves the physicochemical properties of cassava starch-based nanocomposite films. LWT 2017, 86, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.; Catchmark, J.M. Improved eco-friendly barrier materials based on crystalline nanocellulose/chitosan/carboxymethyl cellulose polyelectrolyte complexes. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 80, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koosha, M.; Hamedi, S. Intelligent Chitosan/PVA nanocomposite films containing black carrot anthocyanin and bentonite nanoclays with improved mechanical, thermal and antibacterial properties. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 127, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-F.; Rhim, J.-W. Functionalization of halloysite nanotubes for the preparation of carboxymethyl cellulose-based nanocomposite films. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 150, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddeci, G.; Cavallaro, G.; Di Blasi, F.; Lazzara, G.; Massaro, M.; Milioto, S.; Parisi, F.; Riela, S.; Spinelli, G. Halloysite nanotubes loaded with peppermint essential oil as filler for functional biopolymer film. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 152, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanmani, P.; Rhim, J.-W. Physical, mechanical and antimicrobial properties of gelatin based active nanocomposite films containing AgNPs and nanoclay. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 35, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Ye, S.; Song, X. Construction of Bi2WO6–TiO2/starch nanocomposite films for visible-light catalytic degradation of ethylene. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 88, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, S.M.M.; Zehetmeyer, G.; Scheibel, J.M.; Werner, J.O.; Brandelli, A. Starch-halloysite nanocomposites containing nisin: Characterization and inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes in soft cheese. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 68, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilpiszewska, K.; Antosik, A.K.; Spychaj, T. Novel hydrophilic carboxymethyl starch/montmorillonite nanocomposite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 128, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Alboofetileh, M.; Rezaei, M.; Behrooz, R. Comparing physico-mechanical and thermal properties of alginate nanocomposite films reinforced with organic and/or inorganic nanofillers. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 32, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallakpour, S.; Nezamzadeh Ezhieh, A. Preparation and characterization of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposite films embedded with functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotube. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 166, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Jamil, A.; Yasin, T.; Rafiq, M.A.; Nawaz, M.; Price, G.J. Ultrasound promoted synthesis and properties of chitosan nanocomposites containing carbon nanotubes and silver nanoparticles. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 105, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh, S.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Hamishehkar, H. Physical properties of carboxymethyl cellulose based nano-biocomposites with Graphene nano-platelets. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 84, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, D.; Gong, Q.; Qiu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, T.; Ma, J.; Gao, J. Biodegradable amylose films reinforced by graphene oxide and polyvinyl alcohol. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2013, 142, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Preparation of carrageenan-based functional nanocomposite films incorporated with melanin nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 176, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, Y.-H.; Youn, H.-G.; Shin, J.-Y.; Yoon, S.-D. Preparation of functional chitosan-based nanocomposite films containing ZnS nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, S.; Das, A.; Basu, A.; Abdullah, M.F.; Mukherjee, A. Guar gum benzoate nanoparticle reinforced gelatin films for enhanced thermal insulation, mechanical and antimicrobial properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 170, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, J.; Liu, F.; Majeed, H.; Zhong, F. Characterization of tara gum edible films incorporated with bulk chitosan and chitosan nanoparticles: A comparative study. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 44, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Owczarek, J.S.; Fortunati, E.; Kozanecki, M.; Mazzaglia, A.; Balestra, G.M.; Kenny, J.M.; Torre, L.; Puglia, D. Antioxidant and antibacterial lignin nanoparticles in polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan films for active packaging. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 94, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, A.A.; Rhim, J.-W. Effect of oxidized chitin nanocrystals isolated by ammonium persulfate method on the properties of carboxymethyl cellulose-based films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 175, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, A.A.; Rhim, J.-W. Preparation of multifunctional chitin nanowhiskers/ZnO-Ag NPs and their effect on the properties of carboxymethyl cellulose-based nanocomposite film. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 169, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.H.C.S.; Vilela, C.; Almeida, A.; Marrucho, I.M.; Freire, C.S.R. Pullulan-based nanocomposite films for functional food packaging: Exploiting lysozyme nanofibers as antibacterial and antioxidant reinforcing additives. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 77, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Bagchi, B.; Bhandary, S.; Kool, A.; Hoque, N.A.; Biswas, P.; Pal, K.; Thakur, P.; Das, K.; Karmakar, P.; et al. Antimicrobial and biocompatible fluorescent hydroxyapatite-chitosan nanocomposite films for biomedical applications. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 171, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopi, S.; Amalraj, A.; Jude, S.; Thomas, S.; Guo, Q. Bionanocomposite films based on potato, tapioca starch and chitosan reinforced with cellulose nanofiber isolated from turmeric spent. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauscher, H.; Rasmussen, K.; Sokull-Klüttgen, B. Regulatory Aspects of Nanomaterials in the EU. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2017, 89, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union (Ed.) Regulation (EU) No 528/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2012 Concerning the Making Available on the Market and Use of Biocidal Products; Official Journal of European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; p. L167/161. [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Martínez, J.F.; Hernández-Uresti, D.B.; Reyes-Melo, M.E.; Guerrero-Salazar, C.A.; González-González, V.A.; Sepúlveda-Guzmán, S. Synthesis and optical characterization of ZnS–sodium carboxymethyl cellulose nanocomposite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 84, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wakil, N.A.; Hassan, E.A.; Abou-Zeid, R.E.; Dufresne, A. Development of wheat gluten/nanocellulose/titanium dioxide nanocomposites for active food packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 124, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrasi, G.; Vertuccio, L. Evaluation of zein/halloysite nano-containers as reservoirs of active molecules for packaging applications: Preparation and analysis of physical properties. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 70, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, E.; Nasiri, J.; Malidarreh, T.R.; Kalantari, S.; Naghavi, M.R.; Safari, M. Performance of carnauba wax-nanoclay emulsion coatings on postharvest quality of ‘Valencia’ orange fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 240, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, J.; Störmer, A.; Franz, R. Migration of nanoparticles from plastic packaging materials containing carbon black into foodstuffs. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2014, 31, 1769–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avella, M.; De Vlieger, J.J.; Errico, M.E.; Fischer, S.; Vacca, P.; Volpe, M.G. Biodegradable starch/clay nanocomposite films for food packaging applications. Food Chem. 2005, 93, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, A.S.; Oliveira, M.; de Sá, A.; Rodrigues, R.M.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Vicente, A.A.; Machado, A.V. Antimicrobial nanostructured starch based films for packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 129, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Kai, D.; Ye, H.; Tian, L.; Ding, X.; Ramakrishna, S.; Loh, X.J. Electrospinning of poly(glycerol sebacate)-based nanofibers for nerve tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2017, 70, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri-Nosar, M.; Farzamfar, S.; Sahrapeyma, H.; Ghorbani, S.; Bastami, F.; Vaez, A.; Salehi, M. Cerium oxide nanoparticle-containing poly (ε-caprolactone)/gelatin electrospun film as a potential wound dressing material: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 81, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tra Thanh, N.; Ho Hieu, M.; Tran Minh Phuong, N.; Do Bui Thuan, T.; Nguyen Thi Thu, H.; Thai, V.P.; Do Minh, T.; Nguyen Dai, H.; Vo, V.T.; Nguyen Thi, H. Optimization and characterization of electrospun polycaprolactone coated with gelatin-silver nanoparticles for wound healing application. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 91, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrogi, V.; Pietrella, D.; Nocchetti, M.; Casagrande, S.; Moretti, V.; De Marco, S.; Ricci, M. Montmorillonite–chitosan–chlorhexidine composite films with antibiofilm activity and improved cytotoxicity for wound dressing. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 491, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciotti, I.; Ciocci, M.; Di Giovanni, E.; Nanni, F.; Melino, S. Hydrogen Sulfide-Releasing Fibrous Membranes: Potential Patches for Stimulating Human Stem Cells Proliferation and Viability under Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chang, J.; Wu, C. Bioactive inorganic/organic nanocomposites for wound healing. Appl. Mater. Today 2018, 11, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.; Haponiuk, J.T.; Thomas, S.; Gopi, S. Biopolymer based nanomaterials in drug delivery systems: A review. Mater. Today Chem. 2018, 9, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanbakht, S.; Namazi, H. Doxorubicin loaded carboxymethyl cellulose/graphene quantum dot nanocomposite hydrogel films as a potential anticancer drug delivery system. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 87, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benucci, I.; Liburdi, K.; Cacciotti, I.; Lombardelli, C.; Zappino, M.; Nanni, F.; Esti, M. Chitosan/clay nanocomposite films as supports for enzyme immobilization: An innovative green approach for winemaking applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 74, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, T.R.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Cao, X. In situ and ex situ modifications of bacterial cellulose for applications in tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 82, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Waibhaw, G.; Saxena, V.; Pandey, L.M. Nano-biocomposite scaffolds of chitosan, carboxymethyl cellulose and silver nanoparticle modified cellulose nanowhiskers for bone tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalishwaralal, K.; Jeyabharathi, S.; Sundar, K.; Selvamani, S.; Prasanna, M.; Muthukumaran, A. A novel biocompatible chitosan–Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) film with electrical conductivity for cardiac tissue engineering application. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 92, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, H.; Pal, P.; Dhara, S.; Pathak, A. Fabrication and characterization of polyvinyl alcohol/metal (Ca, Mg, Ti) doped zirconium phosphate nanocomposite films for scaffold-guided tissue engineering application. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 71, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciotti, I. Cationic and Anionic Substitutions in Hydroxyapatite. In Handbook of Bioceramics and Biocomposites; Antoniac, I.V., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 145–211. [Google Scholar]

- Nazeer, M.A.; Yilgör, E.; Yilgör, I. Intercalated chitosan/hydroxyapatite nanocomposites: Promising materials for bone tissue engineering applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 175, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, R.; Subramanyam, V.; Chinnadurai, R.K.; Srinadhu, E.S.; Subramanian, B.; Nallani, S. Development of novel mechanically stable porous nanocomposite (PVDF-PMMA/HAp/TiO2) film scaffold with nanowhiskers surface morphology for bone repair applications. Mater. Lett. 2019, 236, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.; Bozzo, B.M.; Del Gaudio, C.; Cacciotti, I.; Armentano, I.; Dottori, M.; D’Angelo, F.; Martino, S.; Orlacchio, A.; Kenny, J.M. Poly (L-lactic acid)/calcium-deficient nanohydroxyapatite electrospun mats for bone marrow stem cell cultures. J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 2011, 26, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, F.; Armentano, I.; Cacciotti, I.; Tiribuzi, R.; Quattrocelli, M.; Del Gaudio, C.; Fortunati, E.; Saino, E.; Caraffa, A.; Cerulli, G.G.; et al. Tuning Multi/Pluri-Potent Stem Cell Fate by Electrospun Poly(l-lactic acid)-Calcium-Deficient Hydroxyapatite Nanocomposite Mats. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 1350–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Li, H.; Guo, H.; Xie, A.; Wang, S.; Huang, F.; Li, S.; Shen, Y.; He, J. A novel porous aspirin-loaded (GO/CTS-HA)n nanocomposite films: Synthesis and multifunction for bone tissue engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 153, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Lei, B. Transparent sunlight conversion film based on carboxymethyl cellulose and carbon dots. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 151, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitta, S.B.; Reddeppa, M.; Vellampatti, S.; Dugasani, S.R.; Yoo, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.-D.; Ha Park, S. Gold nanoparticle-embedded DNA thin films for ultraviolet photodetectors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 275, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Biopolymer Film | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| cellulose-based films | tasteless, odorless, resistant to oil and fat, hydrophilic nature [27]; thermal and chemical stability [39] | hardly dissolves or melts due to high crystallinity [40]; non antimicrobial activity [41] |

| chitin and chitosan-based films | good CO2 barrier properties, antimicrobial activity [42] | non antioxidant and antifungal activity [43]; limited oxygen and water impediment ability [44] |

| starch-based films | odorless, tasteless, good O2 and CO2 barrier properties [45] | poor water vapor barrier [46] and tensile properties [47] |

| pectin-based films | excellent oxygen barring capacity [48] | high water vapor permeability [49]; poor mechanical performance [48] |

| pullulan-based films | heat-sealable [50]; highly impermeable to both oil and oxygen [51]; excellent mechanical properties and a low permeability to oil and oxygen [52] | low solubility [50]; hydrophilic nature [52] |

| alginate-based films | good water solubility, gel ability, and film-forming properties [53] | insufficient mechanical properties and poor water resistance [54] |

| gelatin-based films | good mechanical and barrier properties [55] | low water vapor permeability [56] |

| whey protein-based films | excellent barrier properties to aroma compounds and oils [27] | hydrophilic nature so it has limitation to moisture [27] |

| lipids-based films | excellent barriers against moisture migration [27] | damage the appearance and gloss of the coated food products [57] |

| bacterial cellulose-based films | flexibility and excellent mechanical properties [58] | insoluble in water [59] |

| PCL- based films | high mechanical strength, biocompatibility, processability, and permeability [60] | highly hydrophobic and crystalline [61] |

| PLA-based films | environmental friendliness, good transparency, and biological compatibility [62] | high hardness, and brittleness, low strength, and poor thermal stability [63] |

| PGA-based films | high mechanical strength [64] | high degree of crystallinity, a high melting point, and it is insoluble in common organic solvents [65] |

| PU-based films | favorable processability, versatile structure–property relationships, and excellent elasticity [66] | low water resistance and hardness [66] |

| Type of Nanofillers | Properties Added to the Film | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Clay Nanofillers | ||

| MMT, Hal etc. | UV shielding properties | [69] |

| Good mechanical stability | ||

| Thermal stability | [70] | |

| Organic Nanofillers | ||

| Nanocellulose | Blood compatibility | |

| Antibacterial effect | [71] | |

| Thermal stability | [72] | |

| Good mechanical stability | ||

| Low cytotoxicity | [73] | |

| Chitosan nanoparticles | Biocompatibility | |

| Biodegradability | [74] | |

| Low toxicity | [75] | |

| Antimicrobial activity | [76] | |

| Inorganic Nanofillers | ||

| AgNPs | Antimicrobial effect | [77] |

| UV shielding properties | [78] | |

| Antioxidant activity | [79] | |

| Photocatalytic effect | [80] | |

| SeNPs | Antimicrobial effect | [81] |

| Antioxidant activity | [82] | |

| CuNPs | Antimicrobial effect | [83] |

| UV shielding properties | [84] | |

| SNPs | Antimicrobial effect | [85] |

| TiO2 NPs | Antifouling effect | [86] |

| Antimicrobial activity | [87] | |

| Photocatalytic activity | [88] | |

| UV shielding properties | [69] | |

| ZnO NPs | Antifungal effect | |

| UV shielding properties | [89] | |

| Antimicrobial effect | [90] | |

| Dielectric properties | ||

| Electromagnetic shielding | ||

| Thermal conductivity | [91] | |

| CeO2 | Antimicrobial effect | |

| UV shielding properties | ||

| Flame retardancy | ||

| Wrinkle resistance | [92] | |

| Carbon Nanofillers | ||

| Graphene, graphene oxide, etc. | Lightweight | |

| Processing benefits, flexibility, resistance to corrosion | ||

| Extraordinary electrical, mechanical, and thermal properties | [93] | |

| Nanofiller | Polymer | The Effect of Nanofiller Addition | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Nanostructures | |||

| AgNPs | gelatin | • Improvement of antibacterial effect from 0 up to 14 mm of inhibition zone against S. typhimurium, B. cereus, L. monocytogenes, E. coli, and S.aureus • Reduction of TS and YM by up to ~25 % and ~36%, respectively, depending on AgNPs concentration • No changes in EAB, WVP, MC, and WCA | [199] |

| AgNPs | chitosan-gelatin | • Reduction of TS (~27%) and improvement of EAB (~34%) • Increased the shelf-life of red grapes on which the film was applied | [200] |

| AgNPs | chitosan | • Improvement of antimicrobial activity against P. aeruginosa (to ~28 mm of inhibition zone), S. aureus (to ~37 mm), and MRSA (to 24.73 mm), depending on AgNPs concentration | [201] |

| AgNPs | chitosan/cellulose | • Improvement of antimicrobial activities against S. aureus (~0.8 mm of inhibition zone) and E. coli (~1.2 mm) | [202] |

| AgNPs | chitosan/PVA | • Improvement of antioxidant activity by up to ~33% (DPPH radical scavenging activity), up to ~37% (ferric reducing ability) and up to ~31% (β-Carotene bleaching), depending on AgNPs concentration • Low toxicity • Improvement of antimicrobial activity against S. areus ( increase by ~1 mm of inhibition zone), B. cereus (~8 mm), M. luteus (~2 mm), S.enterica (~3 mm), E. coli (~3 mm), and P. aeruginosa (~2 mm) | [203] |

| AgNPs AuNPs | chitosan | • Improvement of antimicrobial activity • AuNPs has better activity against A. niger than AgNPs (from 0 to 25 mm of inhibition zone) • AgNPs has better activity against C. albicans than AuNPs ( from 6 to 19 mm of inhibition zone) • No significant difference between antimicrobial activity of AuNPs and AgNPs against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa | [204] |

| AgNPs SeNPs | furcellaran | • Enhancement of MC (with AgNPs ~11.5% and with SeNPs ~14%), WS, EM (with AgNPs and with SeNPs ~10%), but reduction in SR (with AgNPs ~13% and with SeNPs ~20%) • AgNPs improved the UV-blocking effect • No changes in EAB • SeNPs improved antimicrobial activity against E. coli (SeNPs from 0 up to ~38 mm of inhibition zone; AgNPs from 0 to ~10 mm), S. aureus (SeNPs from 0 up to ~22 mm), and MRSA (SeNPs from 0 up to ~26 mm) | [81] |

| SNPs | chitosan | • Increment of TS (by up to ~18%), EM (by up to ~18%) and WCA (by up to ~6%) • Reduction of EAB (by up to ~39%), WVP (by up to 14%) • Enhancement of thermal stability • Antimicrobial activity against L. monocytogenes (complete destroy after 12 h) and E. coli (complete destroy after 6 h) | [85] |

| Lignin capped AgNPs | agar | • Enhancement of UV screening effect • Improvement of TS (by up to ~23%) and YM (by up to ~13 %) • No changes in EAB • Reduction of WVP (by up to ~22%), WCA (by up to ~9%), WS (by up to ~16%), and SR (by up to ~50%) • Improvement of antimicrobial activity against E. coli (complete destroy after 6 h) and L. monocytogenes (complete destroy after 12 h) | [150] |