Al/Graphene Co-Doped ZnO Electrodes: Impact on CTS Thin-Film Solar Cell Efficiency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

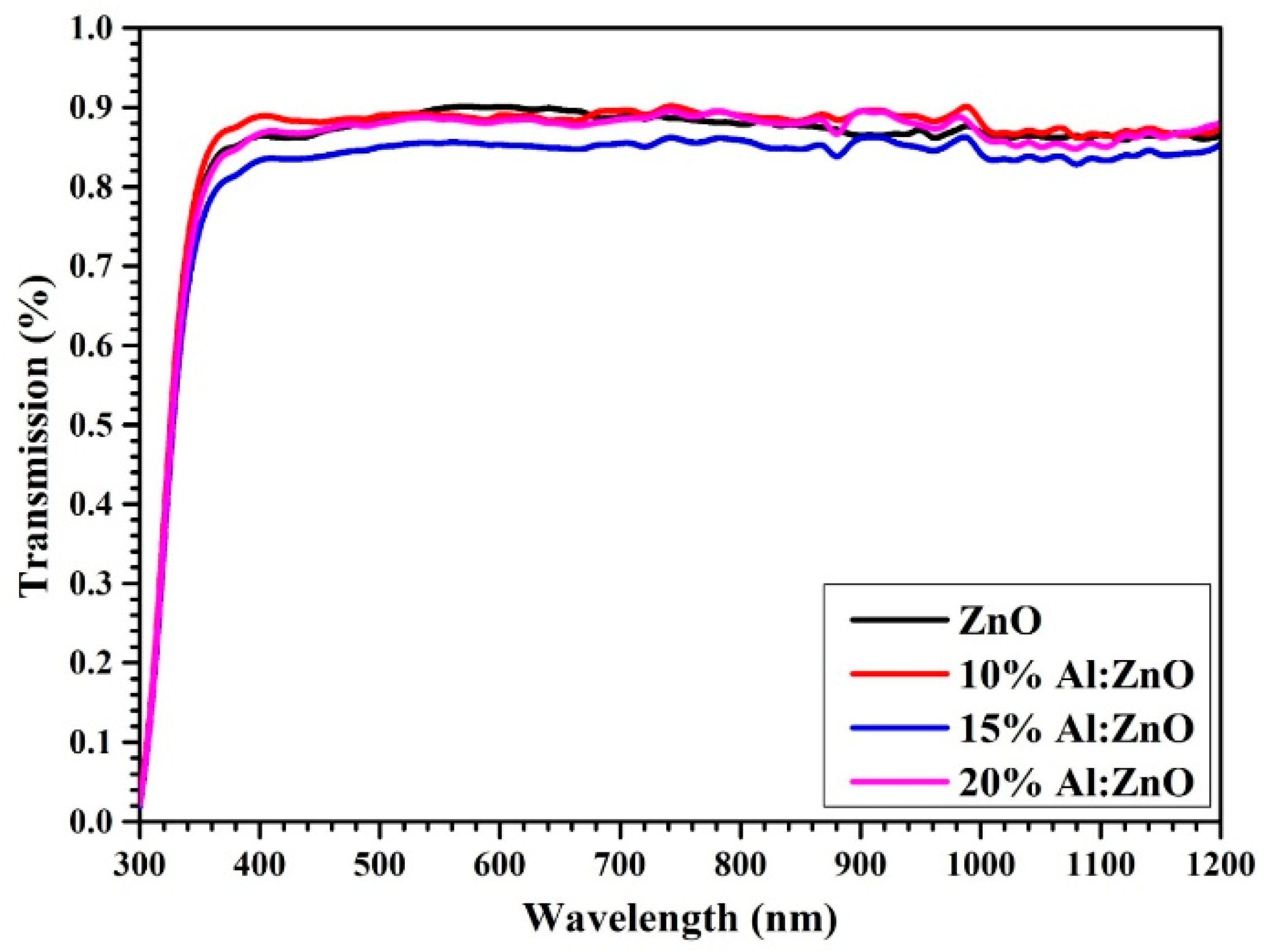

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. XRD

3.2. Electrical Measurements

3.3. Characterization of the CTS Absorber Layer

3.4. Solar Cell

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosa, A.; Da Silva, E.; Amorim, E.; Chaves, M.; Catto, A.; Lisboa-Filho, P.N.; Bortoleto, J. Growth evolution of ZnO thin films deposited by RF magnetron sputtering. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2012, 370, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, R.; Olgar, M.A.; Altuntepe, A.; Seyhan, A.; Turan, R. Integration of graphene with GZO as TCO layer and its impact on solar cell performance. Renew. Energy 2022, 181, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myzaferi, A.; Reading, A.; Cohen, D.; Farrell, R.; Nakamura, S.; Speck, J.; DenBaars, S. Transparent conducting oxide clad limited area epitaxy semipolar III-nitride laser diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 061109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Olmedo, M.; Yang, Z.; Kong, J.; Liu, J. Electrically pumped ultraviolet ZnO diode lasers on Si. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93, 181106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-T.; Chou, Y.-T.; Teng, L.-F. Charge pumping method for photosensor application by using amorphous indium-zinc oxide thin film transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 242101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, K.H.; Bunte, E.; Stiebig, H. Optimization of phase-sensitive transparent detector for length measurements. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 2005, 52, 1656–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H.; Kang, C.K.; Kim, K.K.; Park, I.K.; Hwang, D.K.; Park, S.J. UV electroluminescence emission from ZnO light-emitting diodes grown by high-temperature radiofrequency sputtering. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 2720–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, M.-H.; Xu, J.-W.; Ren, M.-F.; Yang, L. Low temperature synthesis of sol–gel derived Al-doped ZnO thin films with rapid thermal annealing process. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2010, 21, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntepe, A.; Erkan, S.; Hasret, O.; Yagmyrov, A.; Yazici, D.; Tomakin, M.; Olgar, M.A.; Zan, R. Performance of Si-based solar cell utilizing optimized Al-doped ZnO films as TCO layer. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2023, 34, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasim, S.N.F.; Hamid, M.A.A.; Shamsudin, R.; Jalar, A. Synthesis and characterization of ZnO thin films by thermal evaporation. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2009, 70, 1501–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Fuge, G.M.; Ashfold, M.N. Growth of aligned ZnO nanorod arrays by catalyst-free pulsed laser deposition methods. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 396, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, M.-C.; Oh, B.-Y.; Lee, W.; Myoung, J.-M. Fabrication of Zn/ZnO nanocables through thermal oxidation of Zn nanowires grown by RF magnetron sputtering. J. Cryst. Growth 2006, 290, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Ahmed, N.; Raza, Q.; Khan, T.M.; Mehmood, M.; Hassan, M.; Mahmood, N. Effect of thermal annealing on the structural and optical properties of ZnO thin films deposited by the reactive e-beam evaporation technique. Phys. Scr. 2010, 82, 065801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, S.; Parlak, M.; Özcan, Ş.; Altunbaş, M.; McGlynn, E.; Bacaksız, E. Structural, optical and magnetic properties of Cr doped ZnO microrods prepared by spray pyrolysis method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 9293–9298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrag, A.A.-G.; Balboul, M.R. Nano ZnO thin films synthesis by sol–gel spin coating method as a transparent layer for solar cell applications. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2017, 82, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, M.; Fotouhi, L.; Ehsani, A.; Shiri, H.M. Novel electroactive nanocomposite of POAP for highly efficient energy storage and electrocatalyst: Electrosynthesis and electrochemical performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 484, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taunk, P.; Das, R.; Bisen, D.; Tamrakar, R.; Rathor, N. Synthesis and optical properties of chemical bath deposited ZnO thin film. Karbala Int. J. Mod. Sci. 2015, 1, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahsahlan, M.; Aref, S.M.; Naghshara, H. Structural and optical properties of ZnO thin films as a function of pH value and its effect on photoelectrochemical water splitting. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 055533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, A.F.; Ahmed, S.M.; Hamad, S.M.; Almessiere, M.A.; Ahmed, N.M.; Sajadi, S.M. Effect of different pH values on growth solutions for the ZnO nanostructures. Chin. J. Phys. 2021, 71, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meziane, K.; El Hichou, A.; El Hamidi, A.; Mansori, M.; Liba, A.; Almaggoussi, A. On the sol pH and the structural, optical and electrical properties of ZnO thin films. Superlattices Microstruct. 2016, 93, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosidlak, N.; Jaglarz, J.; Dulian, P.; Pietruszka, R.; Witkowski, B.S.; Godlewski, M.; Powroźnik, W.; Stapiński, T. The thermo-optical and optical properties of thin ZnO and AZO films produced using the atomic layer deposition technology. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 900, 163313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandeep, K.; Bhat, S.; Dharmaprakash, S. Structural defects and photoluminescence studies of sol–gel prepared ZnO and Al-doped ZnO films. Appl. Phys. A 2016, 122, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-S.; Lien, S.-Y.; Huang, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Liu, C.-Y.; Nautiyal, A.; Wuu, D.-S.; Lee, S.-J. Effect of oxygen to argon flow ratio on the properties of Al-doped ZnO films for amorphous silicon thin film solar cell applications. Thin Solid Film. 2013, 529, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, S.; Polat, İ.; Atasoy, Y.; Bacaksız, E. Structural, morphological, optical and electrical evolution of spray deposited ZnO rods co-doped with indium and sulphur atoms. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2014, 25, 1810–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.-J.; Yang, C.-C.; Lai, L.-T. growth of Al-, Ga-, and In-doped ZnO nanostructures via a low-temperature process and their application to field emission devices and ultraviolet photosensors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 164, B3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, D.B.; Powell, M.J.; Parkin, I.P.; Carmalt, C.J. Aluminium/gallium, indium/gallium, and aluminium/indium co-doped ZnO thin films deposited via aerosol assisted CVD. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi-qiang, X.; Hong, D.; Yan, L.; Hang, C. Al-doping effects on structure, electrical and optical properties of c-axis-orientated ZnO: Al thin films. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2006, 9, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mridha, S.; Basak, D. Aluminium doped ZnO films: Electrical, optical and photoresponse studies. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2007, 40, 6902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadi, H.; Benzarti, Z.; Mourad, S.; Sanguino, P.; Hadouch, Y.; Mezzane, D.; Abdelmoula, N.; Khemakhem, H. Electrical conductivity improvement of (Fe + Al) co-doped ZnO nanoparticles for optoelectronic applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 8065–8085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, M.; Shin, J.; Kim, K.; Yu, K.J. Electronic and thermal properties of graphene and recent advances in graphene based electronics applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Wu, H. Graphene-based nanomaterials: Synthesis, properties, and optical and optoelectronic applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 1984–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xu, J.; Lu, H.; Fang, G. Sol-gel derived Al-doped zinc oxide–Reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 699, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, I.Y. Highly conductive and transparent reduced graphene oxide/aluminium doped zinc oxide nanocomposite for the next generation solar cell applications. Opt. Mater. 2013, 36, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgar, M. Improvement in the structural and optical properties of Cu2SnS3 (CTS) thin films through soft-annealing treatment. Superlattices Microstruct. 2020, 138, 106366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacaksiz, E.; Aksu, S.; Yılmaz, S.; Parlak, M.; Altunbaş, M. Structural, optical and electrical properties of Al-doped ZnO microrods prepared by spray pyrolysis. Thin Solid Film. 2010, 518, 4076–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimifard, R.; Abdizadeh, H.; Golobostanfard, M.R. Controlling the extremely preferred orientation texturing of sol–gel derived ZnO thin films with sol and heat treatment parameters. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2020, 93, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, M.; Hyde, B.G. Crystal Structures; Courier Dover Publications: Garden City, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bacaksiz, E.; Parlak, M.; Tomakin, M.; Özçelik, A.; Karakız, M.; Altunbaş, M. The effects of zinc nitrate, zinc acetate and zinc chloride precursors on investigation of structural and optical properties of ZnO thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 466, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, R.; Olgar, M.A.; Atasoy, Y.; Erkan, S.; Altuntepe, A. Boron doped graphene and MoS2 based ultra-thin Schottky junction solar cell. Opt. Mater. 2025, 162, 116828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauc, J. Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous Ge and Si. Mater. Res. Bull. 1968, 3, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Jeon, H.; Kang, T.; Seth, R.; Panwar, S.; Shinde, S.K.; Waghmode, D.; Saratale, R.G.; Choubey, R.K. Variation in chemical bath pH and the corresponding precursor concentration for optimizing the optical, structural and morphological properties of ZnO thin films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 17747–17758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, S.; Islam, M.; Akram, A. Sol–gel synthesis of intrinsic and aluminum-doped zinc oxide thin films as transparent conducting oxides for thin film solar cells. Thin Solid Film. 2013, 529, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kars Durukan, I.; Özen, Y.; Kizilkaya, K.; Öztürk, M.; Memmedli, T.; Özçelik, S. Effects of annealing and deposition temperature on the structural and optical properties of AZO thin films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2013, 24, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Al-Hartomy, O.A.; El Okr, M.; Nawar, A.; El-Gazzar, S.; El-Tantawy, F.; Yakuphanoglu, F. Semiconducting properties of Al doped ZnO thin films. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 131, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A.; Zahirifar, J.; Karimi-Sabet, J.; Dastbaz, A. Graphene nanosheets preparation using magnetic nanoparticle assisted liquid phase exfoliation of graphite: The coupled effect of ultrasound and wedging nanoparticles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 44, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Meyer, J.C.; Scardaci, V.; Casiraghi, C.; Lazzeri, M.; Mauri, F.; Piscanec, S.; Jiang, D.; Novoselov, K.S.; Roth, S. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 187401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullity, B.; Stock, S. Elements of X-Ray Diffraction, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 174–177. [Google Scholar]

- Aryanto, D.; Jannah, W.; Sudiro, T.; Wismogroho, A.; Sebayang, P.; Marwoto, P. Preparation and structural characterization of ZnO thin films by sol-gel method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 817, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, S.; Ndamitso, M.; Abdulkareem, A.; Tijani, J.; Shuaib, D.; Mohammed, A.; Sumaila, A. Comparative study of crystallite size using Williamson-Hall and Debye-Scherrer plots for ZnO nanoparticles. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2019, 10, 045013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirirak, R.; Phettakua, P.; Rangdee, P.; Boonruang, C.; Klinbumrung, A. Unveiling the impact of excessive dopant content on morphology and optical defects in carbonation synthesis of nanostructured Al-doped ZnO. Powder Technol. 2024, 435, 119444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.R.; Blake, P.; Grigorenko, A.N.; Novoselov, K.S.; Booth, T.J.; Stauber, T.; Peres, N.M.; Geim, A.K. Fine structure constant defines visual transparency of graphene. Science 2008, 320, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.-T.; Wang, F.-H.; Chen, W.-C. Effects of concentration of reduced graphene oxide on properties of sol–gel prepared Al-doped zinc oxide thin films. Thin Solid Film. 2016, 605, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Atomic (%) | Atomic Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Zn | % O | % Al | Zn/O | Al/(Al + Zn) | |

| ZnO | 19.3 | 80.7 | - | 0.24 | - |

| 10%-Al:ZnO | 17.1 | 80.8 | 2.2 | 0.21 | 0.11 |

| 15%-Al:ZnO | 18.8 | 77.9 | 3.3 | 0.24 | 0.15 |

| 20%-Al:ZnO | 17 | 79.1 | 3.9 | 0.22 | 0.19 |

| Sample | Resistivity (ohm.cm) | Carrier Density (cm−3) | Mobility (cm2/V.s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO | (1.5 ± 0.7) × 104 | (2.1 ± 0.4) × 1014 | 2.2 ± 0.6 |

| 10%-Al:ZnO | (2.6 ± 2.2) × 103 | (4.1 ± 1.2) × 1014 | 4.1 ± 0.5 |

| 15%-Al:ZnO | (1.0 ± 0.3) × 103 | (6.9 ± 0.8) × 1014 | 8.7 ± 0.7 |

| 20%-Al:ZnO | (3.7 ± 1.3) × 103 | (4.4 ± 1.1) × 1014 | 4.3 ± 0.5 |

| Sample | 2θ (°) | FWHM (°) | D (nm) | Lattice Parameters | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a (Å) | c (Å) | ||||

| ZnO | 34.40 | 0.31 | 28.01 | 3.250 | 5.200 |

| 10%-Al:ZnO | 34.60 | 0.36 | 24.13 | 3.247 | 5.181 |

| 15%-Al:ZnO | 34.52 | 0.39 | 22.27 | 3.246 | 5.192 |

| 20%-Al:ZnO | 34.56 | 0.51 | 17.03 | 3.252 | 5.186 |

| 0.5%-Gr:AZO | 34.62 | 0.44 | 19.75 | 3.237 | 5.178 |

| 1%-Gr:AZO | 34.58 | 0.49 | 17.73 | 3.257 | 5.184 |

| 1.5%-Gr:AZO | 34.46 | 0.43 | 20.19 | 3.238 | 5.201 |

| 2%-Gr:AZO | 34.62 | 0.41 | 21.19 | 3.245 | 5.178 |

| Sample | Resistivity (ohm.cm) | Carrier Density (cm−3) | Mobility (cm2/V.s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5%-Gr:AZO | (5.1 ± 0.4) × 103 | (5.1 ± 3.1) × 1014 | 4.1 ± 0.7 |

| 1%-Gr:AZO | (3.5 ± 0.2) × 103 | (5.0 ± 0.5) × 1014 | 5.0 ± 0.5 |

| 1.5%-Gr:AZO | (4.3 ± 1.1) × 103 | (1.2 ± 0.3) × 1015 | 13.1 ± 0.3 |

| 2%-Gr:AZO | (6.5 ± 3.3) × 103 | (2.5 ± 0.6) × 1014 | 5.9 ± 0.4 |

| Sample | Atomic (%) | Atomic Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | Sn | S | Cu/Sn | S/Metal | |

| CTS | 28.9 | 18.8 | 52.3 | 1.54 | 1.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ozbek, D.; Cam, M.; Toplu, G.; Erkan, S.; Erkan, S.; Altuntepe, A.; Ocakoglu, K.; Aydogan, S.; Atasoy, Y.; Olgar, M.A.; et al. Al/Graphene Co-Doped ZnO Electrodes: Impact on CTS Thin-Film Solar Cell Efficiency. Crystals 2026, 16, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010064

Ozbek D, Cam M, Toplu G, Erkan S, Erkan S, Altuntepe A, Ocakoglu K, Aydogan S, Atasoy Y, Olgar MA, et al. Al/Graphene Co-Doped ZnO Electrodes: Impact on CTS Thin-Film Solar Cell Efficiency. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleOzbek, Done, Meryem Cam, Guldone Toplu, Sevde Erkan, Serkan Erkan, Ali Altuntepe, Kasim Ocakoglu, Sakir Aydogan, Yavuz Atasoy, Mehmet Ali Olgar, and et al. 2026. "Al/Graphene Co-Doped ZnO Electrodes: Impact on CTS Thin-Film Solar Cell Efficiency" Crystals 16, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010064

APA StyleOzbek, D., Cam, M., Toplu, G., Erkan, S., Erkan, S., Altuntepe, A., Ocakoglu, K., Aydogan, S., Atasoy, Y., Olgar, M. A., & Zan, R. (2026). Al/Graphene Co-Doped ZnO Electrodes: Impact on CTS Thin-Film Solar Cell Efficiency. Crystals, 16(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010064